Artificial Intelligence in the synthesis and application of advanced dental biomaterials: a narrative review of probabilities and challenges

-

Dania Hany Elazzouni

, Wael Awadh

, Abdulrahman Alshehri

and Aftab Ahmed Khan

Abstract

This narrative review explores the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in advancing the synthesis, optimization, and clinical translation of dental biomaterials. It critically evaluates how AI-driven approaches address existing challenges related to material performance, biocompatibility, and durability, while identifying current research gaps and outlining future perspectives. A comprehensive literature synthesis was conducted through electronic searches in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. Selected articles encompassed both experimental and computational studies. Case studies were analyzed to illustrate the application of AI techniques, including machine learning (ML) for predicting mechanical properties, deep learning (DL) for microstructural and imaging analysis, and optimization algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms) for materials discovery and formulation enhancement. The findings indicate that ML models can accurately predict mechanical properties (e.g., flexural modulus), DL enables automated detection of material degradation, and optimization algorithms accelerate the discovery of advanced biomaterials such as high-entropy ceramics. AI also facilitates the development of personalized, adaptive materials, including pH-responsive and self-healing resin composites. Nonetheless, barriers remain, including data scarcity, limited generalizability, high computational demands, and lack of standardization. AI is poised to redefine the landscape of dental biomaterials by enabling smarter material design, improved performance prediction, and accelerated clinical translation. This review advances the field by integrating emerging computational approaches with practical needs and identifying unresolved challenges that hinder real-world adoption. Ultimately, leveraging AI alongside technologies such as 3D printing and digital twin systems can drive the development of next-generation biomaterials tailored to patient-specific clinical outcomes.

1 Introduction

1.1 Biomaterials in dentistry

Biomaterials play a crucial role in tissue engineering [1], 2] and are indispensable across all dental disciplines. It would not be wrong to say that dental biomaterials are as important to the dentist as pharmacology is to the physician. They are used in fillings, crowns, bridges, dentures, implants, orthodontic appliances, root canal treatments, and periodontic treatments [3]. The primary goal of these materials is to replicate or enhance the natural structures of teeth and surrounding tissues while ensuring durability, strength, and biocompatibility under the complex conditions of the oral environment [4].

In restorative and prosthetic dentistry, resin composites and ceramics face issues like polymerization shrinkage, mechanical degradation [5], and brittleness [6], compromising longevity and marginal integrity. Periodontics relies on bioactive materials (e.g., bioactive glasses) for tissue regeneration [7], [8], [9], yet their efficacy in promoting predictable healing remains inconsistent. Orthodontics employs brackets, wires, and adhesives, which risk enamel demineralization [10], 11] and bond failure due to mechanical fatigue or biofilm accumulation [10], 11]. Endodontics depends on root canal sealers and gutta-percha, which may exhibit inadequate sealing or biocompatibility, increasing reinfection risks [12]. Preventive dentistry utilizes pit-and-fissure sealants and fluoride-releasing materials [13], 14], though their durability and sustained therapeutic effects are limited. Across these disciplines, persistent issues such as biofilm adhesion, material fatigue, interfacial debonding, and biocompatibility challenges demand innovative solutions to enhance clinical performance and patient outcomes.

1.2 Traditional approaches for the synthesis and optimization of dental biomaterials

Conventional strategies for developing dental biomaterials rely on empirical methods, systematic testing, and material science principles. These approaches combine trial-and-error with expert knowledge to refine performance [15], [16], [17]. Key aspects include:

Empirical formulation: Resin composites and related materials are systematically improved by testing different resin, filler, and additive combinations using empirical formulas that help quantify their properties. This approach enables researchers to assess and refine key characteristics such as strength, wear resistance, handling, and aesthetics through calculated measurements and standardized testing methods. The data derived from these tests allow for the prediction of clinical behavior, guide iterative formulation improvements, and optimize material performance in real-world dental applications. Multiple rounds of such refinement based on empirical testing and quantitative analysis are typically required to achieve the desired balance of mechanical and biological properties for clinical success [18], [19], [20].

Filler and composition optimization: In glass-ionomers and zirconia ceramics, properties are tuned by modifying filler type, particle size, stabilizers, or processing. Zirconia’s fracture resistance and translucency depend on sintering and alloying, while glass-ionomer performance is governed by the glass–polyacid ratio [21].

Surface treatments: Titanium alloys and bioactive glasses benefit from treatments such as sandblasting, acid etching, or anodizing, which improve surface roughness, osseointegration, and bioactivity. These modifications are optimized through testing to achieve desired biological and mechanical outcomes [22].

In vitro testing: Optimization traditionally involves mechanical and durability assessments (tensile, compressive, flexural, wear, and fatigue) under simulated oral conditions, including thermocycling, mechanical loading, and acidic exposure, to predict clinical performance.

Traditional approaches, while effective, are time-consuming, costly, and limited in predicting long-term behavior or nanoscale interactions [16], 25]. Consequently, emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence and computational modeling are increasingly being adopted to complement and enhance these methods, enabling greater precision and efficiency in the design and optimization of advanced dental biomaterials.

2 Introduction to Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to computer systems designed to simulate human cognition, enabling learning, problem-solving, decision-making, and pattern recognition through data analysis [17]. Recent advancements in AI emphasize autonomous decision-making capabilities known as agentic AI, allowing systems to independently perform complex tasks and adapt dynamically to changing environments. Additionally, the rise of edge AI enables data processing directly on devices, enhancing privacy and real-time responsiveness [26]. This advanced and rapidly expanding field within computer science facilitates remarkable innovations and transformative uses across a wide array of industry sectors [27]. AI comprises a diverse set of technologies aimed at replicating human intelligence and augmenting decision-making processes [16]. Its role is becoming increasingly pivotal in the realms of design, optimization, and performance assessment [28]. AI technologies encompass various methodologies and techniques, such as machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and optimization algorithms, which empower systems to learn from data, make autonomous decisions, and address complex problems without the need for explicit programming [29]. Alongside these innovations, ethical challenges regarding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and workforce transformation require structured governance and proactive strategies to balance AI’s benefits with societal and economic implications. AI has achieved significant progress across numerous fields, including healthcare and, more recently, dental sciences [30].

2.1 Overview of AI technologies

Machine Learning (ML): A subset of AI, ML enables systems to learn from data, identify patterns, and make predictions without explicit instructions [31]. This ability to predict and classify outcomes from large volumes of data makes ML particularly valuable in industries like healthcare, manufacturing, and more [32]. In its application, ML involves supervised learning (where algorithms are trained on labeled data), unsupervised learning (where the system identifies patterns without labeled inputs), and reinforcement learning (where systems learn through trial and error) [33], 34]. In medical imaging, ML is used to classify images as cancerous or non-cancerous [35], a task similarly being applied in fields like dental imaging for diagnosing conditions.

Deep Learning (DL): DL, a more advanced subset of ML, uses artificial neural networks (ANNs) with many layers (hence the term “deep”) to model complex patterns in data [31], 33]. These networks simulate the way the human brain processes information and are particularly powerful when working with unstructured data like images, audio, and text [36]. DL systems can automatically extract relevant features from raw data, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering, which makes them particularly useful in fields with large volumes of data [36]. In healthcare, DL is applied to interpret patient records, clinical notes, and research articles, facilitating the extraction of useful insights from unstructured data [37], 38].

Optimization algorithms: These AI methods systematically identify the optimal solutions from a set of feasible alternatives [39] and are extensively applied in domains such as material synthesis, logistics, and scheduling, where the complexity of decision variables necessitates advanced computational approaches [40]. Their utility is particularly evident in the analysis and management of systems characterized by multiple interacting parameters, enabling efficient, accurate decision-making [41]. Within healthcare, optimization algorithms contribute significantly to resource allocation, treatment planning, and diagnostic procedures [42]. Figure 1 provides an overview of the paradigm shift from empirical, experience-based approaches to AI-driven methodologies in dental biomaterials research, emphasizing the integration of ML, DL, and computational optimization strategies.

Evolution of methodologies in dental biomaterials research. The schematic illustrates the transition from traditional, empirical approaches to modern, data-driven Artificial Intelligence (AI) methodologies. AI encompasses key branches such as ML for predictive modeling, DL for complex pattern recognition in images and data, and optimization algorithms for efficiently identifying ideal material compositions and structures.

While the role of AI in dentistry is well-established in diagnostic and therapeutic domains [43], [44], [45], its application specifically to the synthesis and utilization of dental biomaterials remains an emerging field. AI technologies have seen widespread adoption in areas such as oral radiology [46], orthodontics [47], endodontics [48] and implantology [49], 50]. However, the integration of AI in dental biomaterials research is still limited but holds considerable promise. This paradigm shift enables the development of advanced biomaterials with optimized physicochemical properties, enhanced predictive performance, and potential for personalized clinical application. Consequently, AI is marking a transition toward data-driven innovation within dental materials science, opening new avenues for material design and functional optimization.

This review provides a critical evaluation of the role of AI in the synthesis, optimization, and clinical performance of dental biomaterials. An electronic search of Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science was conducted using the terms “Artificial Intelligence in biomaterials”, “machine learning in biomaterials”, “deep learning in biomaterials”, “optimization algorithms in biomaterials”, and “neural networks in biomaterials”. Only peer-reviewed, English-language articles indexed in major databases were included. This review follows a narrative synthesis approach and does not adhere to PRISMA systematic review guidelines. The review synthesizes current research on AI-driven methodologies – including ML, DL, and computational optimization – to address challenges in material performance (e.g., mechanical durability, polymerization shrinkage), biocompatibility, and longevity. It further explores AI’s potential to accelerate the discovery of advanced dental biomaterials, enhance predictive modeling under oral conditions, and enable personalized, patient-specific solutions. Finally, it highlights the latest literature on AI-driven materials discovery, predictive modeling, while pinpointing gaps and proposing new directions for interdisciplinary research. This review does not involve original modeling or numerical simulations; instead, it synthesizes methodologies from published studies. Unlike previous reviews, this article integrates both traditional and emerging AI frameworks to create a comprehensive perspective on their impact and potential in dental biomaterials research.

3 AI techniques in dental biomaterials synthesis and application

AI technologies can be integrated into dental biomaterials research to predict mechanical, chemical, and biological properties, optimize formulations, and develop smart biomaterials with superior performance. Figure 2 outlines a comparative workflow framework contrasting the methodological divergence between AI-driven frameworks and conventional empirical protocols in dental biomaterials design.

Comparative workflow for dental biomaterials design: Traditional versus AI-driven approaches. The traditional workflow illustrates a repetitive, time-consuming process of empirical formulation, laboratory testing, and manual analysis, whereas the AI-driven workflow employs material datasets to train predictive models that identify optimal properties and compositions, expediting design and reducing reliance on physical experimentation.

3.1 ML in dental biomaterials synthesis and application

ML facilitates predictive modeling by identifying patterns within large datasets, enabling the estimation of crucial material properties such as mechanical strength, polymerization shrinkage, and biocompatibility [51]. Algorithms including Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, ANNs, and k-nearest neighbors (KNN) have been employed to optimize formulation processes and reduce experimental costs [16], 52]. SVMs function by classifying data through determination of optimal hyperplanes that separate distinct material property classes, while Random Forests leverage an ensemble of Decision Trees to enhance predictive accuracy [16]. ANNs, inspired by biological neural networks, comprise interconnected layers of nodes or neurons that process complex information, recognize patterns, and generate predictions. This approach is particularly beneficial for elucidating complex relationships between material components and their resultant properties [51]. Collectively, these ML models offer powerful tools for rapid evaluation and optimization of advanced dental biomaterials, thereby accelerating research and development in restorative and prosthetic dental applications.

ML can support resin composite optimization by determining resin–filler ratios for targeted mechanical performance, predicting biological responses, and evaluating durability under stress, aging, or environmental challenges. It can also guide strategies for surface modification to improve bonding or osseointegration and facilitate virtual screening for bioactive or remineralizing materials.

In a study predicting resin composite performance, ML models utilized data from 233 commercial resin composites to identify key factors influencing flexural modulus and volumetric shrinkage. The k-nearest neighbors (KNN) model, a widely utilized supervised ML algorithm for classification and regression tasks [53], demonstrated 90 % predictive accuracy for flexural modulus, highlighting triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), a monomer that enhances rigidity through crosslinking, as the most influential factor (39 % importance). Similarly, a Decision Tree model predicted volumetric shrinkage with 81 % accuracy. This model partitions the data based on material properties such as resin type, filler content, and curing method, thereby elucidating how these features affect shrinkage behavior. It revealed that increased TEGDMA content elevates shrinkage due to its reactive chemistry, while greater filler loading reduces shrinkage by diluting the resin matrix [54].

Designing ceramics with enhanced properties presents significant challenges due to the vast array of elemental combinations. In one study, ML was employed to predict optimal mixtures for high-entropy ceramics (HECs) composed of equal parts of transition metals such as hafnium, niobium, tantalum, titanium, and zirconium. A Random Forest algorithm, an ensemble method that integrates multiple decision trees, was utilized to improve prediction accuracy and robustness [55]. The model analyzed data from existing ceramics, considering factors such as atomic size differences and thermodynamic stability, to identify compositions likely to form stable, single-phase ceramics. The predictive performance facilitated the identification of 70 new HEC formulas, which were later validated experimentally. These ceramics showed uniform microstructures and higher physical and mechanical properties [56]. While the study focused on general biomedical applications, the same ML approach can be adapted for the synthesis of advanced dental ceramics (e.g., zirconia or bioactive glass).

In another study, the investigators proposed an ML-driven approach utilizing a large database of material structures analyzed through finite element analysis (FEA). A self-learning algorithm refined those structures by eliminating weaker designs and selecting high-performing candidates. The results demonstrated that the method can generate tougher and stronger materials, validated through additive manufacturing. Additionally, ML served as an efficient alternative to conventional microstructural analysis, significantly enhancing computational efficiency. This smart additive manufacturing approach paved the way for the accelerated discovery and fabrication of novel high-performance materials [57]. Similarly, ML can optimize ceramic-resin composites for dental crowns to balance strength and aesthetics or fine-tune printing settings for precise dental implants. By automating trial-and-error, ML can rapidly develop materials tailored for dental applications, such as patient-specific bridges with ideal fit and durability, reducing clinical failure rates.

Subsequently, Wang et al. demonstrated the use of ML to predict the µTBS of dental adhesives, reducing reliance on time-intensive laboratory testing. Data from 81 adhesives were analyzed using nine ML algorithms, identifying organophosphate monomer (i.e., MDP), pH, organic solvent, and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate as key factors influencing µTBS. A refined model using these four features achieved an AUC of 0.90 and an accuracy of 0.81. The results highlighted ML’s potential to accelerate the discovery and optimization of dental adhesives, enhancing efficiency in materials research [58].

While these ML methods have significantly improved predictive capabilities, more complex phenomena such as aging, dynamic degradation, and environment-responsive behavior require more sophisticated modeling frameworks such as DL and optimization algorithms.

3.2 DL in dental biomaterials synthesis and application

DL is a subset of ML that utilizes ANNs with multiple layers to model complex patterns and relationships in data [59], 60]. DL can gain significant attention in dental biomaterials research due to its ability to process large datasets, recognize intricate patterns, and optimize material properties without extensive trial-and-error experimentation. DL techniques are especially valuable in predicting the mechanical, physical, chemical, and biological behavior of dental materials, streamlining material development and enhancing clinical applications.

Park et al. used DL models, specifically YOLO (You Only Look Once), a popular real-time object detection algorithm, and SSD (Single Shot Detector), which detects objects in a single pass – to automate cephalometric landmark detection on lateral cephalograms. YOLO achieved 5 % higher accuracy than SSD in their study. This advancement can enhance the design of orthodontic appliances (e.g., aligners, brackets) by ensuring precise force distribution and geometric customization based on biomaterial properties, such as the flexibility of thermoplastic polymers or the durability of ceramic brackets. The study highlighted YOLO’s efficiency in processing high-resolution images (608 × 608 pixels), which reduces manual errors in appliance fabrication workflows [61]. However, limitations included reliance on a single examiner for validation and the need for larger datasets to generalize results across diverse patient anatomies.

Lee et al. applied Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) – designed for image analysis through spatial feature-learning convolutional layers – to detect caries in periapical radiographs with 89 % accuracy. This approach can also be adapted to monitor degradation in resin composites or adhesives. By analyzing marginal leakage or secondary caries around restorations, DL models can predict material failure caused by moisture exposure or mechanical stress [62]. Similarly, Casalegno et al. utilized CNNs to evaluate near-infrared transillumination (NILT) images, achieving an AUC of 85.6 % for proximal lesions, a technique extendable to identifying subsurface cracks in resin composites [63]. Challenges include low-resolution training data (e.g., 256 × 320 pixels in Casalegno et al.) and the lack of longitudinal studies to correlate radiographic patterns with long-term biomaterial performance.

3.2.1 Neural networks in dental biomaterials synthesis and application

Traditional ML methods, such as SVM and Random Forests, are adept at predicting linear or moderately complex relationships [64]; however, they are inadequate for tackling more intricate material behaviors, such as degradation patterns resulting from aging, the influence of saliva, or thermocycling. These situations require the utilization of more sophisticated modeling techniques. DL, particularly through CNNs and Deep Neural Networks, has demonstrated effectiveness in addressing these complexities [65]. DL models are capable of identifying non-linear relationships between material properties and external factors. For example, models based on ANNs can forecast the reduction in bond strength of resin composites due to aging or simulate alterations in surface roughness after simulated brushing cycles. Furthermore, DL models can analyze image-based data from Scanning Electron Microscopy or micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans to identify microstructural defects linked to long-term failures.

3.3 Optimization algorithms in dental biomaterials synthesis and application

Optimization algorithms are computational tools that can refine material composition by adjusting polymer-filler ratios, processing conditions, and chemical formulations. In dental biomaterials, these algorithms can be critical for tailoring materials like polymers, ceramics, resin composites, and alloys to a clinical need. The most commonly used optimization algorithms include.

3.3.1 Genetic algorithms (GAs)

GAs are evolutionary algorithms inspired by natural selection that are particularly effective in solving complex, nonlinear optimization problems [29], 66]. In dental biomaterials, GAs can be applied to optimize formulations of resin composites and adhesive systems by evolving candidate solutions based on desired mechanical properties such as flexural strength, polymerization shrinkage, and wear resistance. These algorithms operate through selection, crossover, and mutation, gradually improving material formulations over successive generations.

3.3.2 Bayesian optimization

Bayesian Optimization is a probabilistic, model-based approach suited for functions that are costly to evaluate [67], making it valuable in material development. In dental biomaterials, it can predict and improve adhesive properties like microtensile bond strength (µTBS) using limited datasets of chemical compositions. By efficiently identifying promising formulations, it reduces experimental effort, and recent studies show its effective integration with ML to forecast high-performing adhesives from minimal chemical descriptors [68], 69].

A Bayesian network was recently used to predict fatigue crack propagation in metallic biomaterials from 650 phase-contrast tomography scans. By analyzing micromechanical variables and microstructural features, the model identified stress axis orientation and maximum shear stress as key predictors, enabling accurate simulations of small-crack behavior in alloys like Ti–6Al–4V. This approach reduced costly experimental trials and offered valuable insights into implant failure mechanisms [15].

3.3.3 Topology optimization

Topology Optimization is widely used in designing dental prosthetics and biomaterials to maximize mechanical efficiency and conserve material [70]. By identifying optimal configurations within a design space, it improves strength-to-weight ratios [71]. In dentistry, it can aid in customizing denture frameworks, implants, and crowns through FEA, enhancing load-bearing performance and patient comfort by minimizing bulk.

A recent study used molecular docking and dynamics simulations to optimize resin composites by assessing interactions among monomers, fillers, and coupling agents. The method predicted binding energies and mechanical properties, with EBPADMA-SiO2-TRIS showing balanced performance and clinical promise. This highlights the value of in silico tools for designing and optimizing dental biomaterials before experimental validation [72].

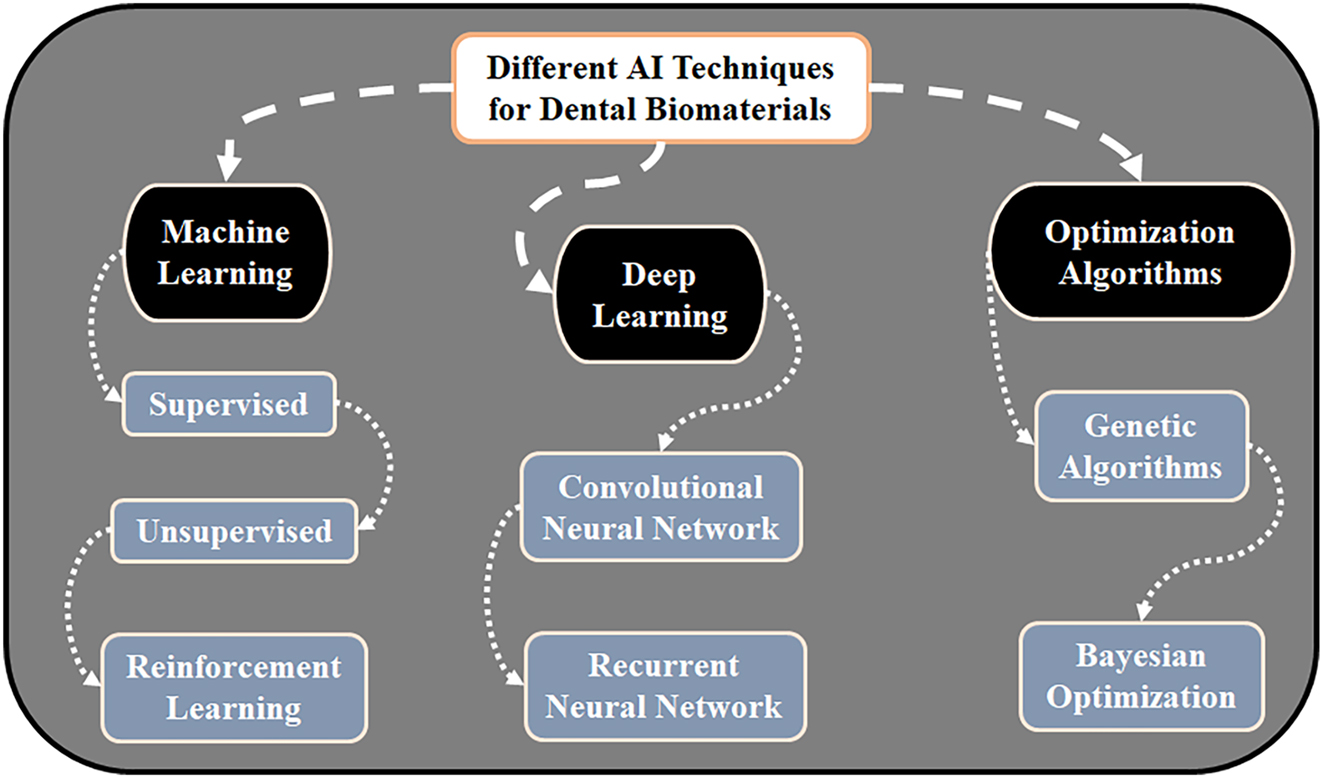

Beyond property prediction, AI is increasingly applied to optimize material compositions using algorithms like GA and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [73], which mimic natural processes to refine ingredient ratios and processing parameters. GA can optimize filler-to-resin ratios in composites, while PSO can adjust ceramic sintering for desired translucency and strength. These methods speed up material discovery by narrowing experimental trials, with key techniques summarized in Figure 3.

Key AI techniques for the design of dental biomaterials. The diagram categorizes core AI methodologies and their primary applications: ML for predicting material properties and optimizing formulations; DL for analyzing complex imaging and microstructural data; and optimization algorithms for navigating multi-variable parameter spaces to discover ideal material compositions and processing conditions.

3.3.4 AI-guided synthesis of smart and bioactive dental materials

The potential of AI in the field of dental biomaterials is significantly highlighted by its role in the innovation of bioactive and intelligent materials [15]. This encompasses ion-releasing resin composites, remineralizing cements, and self-healing resin or resin composites. AI algorithms are capable of forecasting not only the static characteristics but also the dynamic behaviors, such as the quantity of calcium or phosphate released by a glass ionomer over time, or the material’s reaction to variations in pH or temperature. For instance, Reinforcement Learning models can replicate how various environmental factors (such as salivary enzymes or thermal stress) affect the efficacy of ‘smart’ resins that are engineered to expand during curing or to autonomously mend microcracks. These predictive models facilitate the design of materials that proactively enhance oral health, transcending traditional passive restorative roles. A comparative summary of traditional and AI-driven approaches in dental biomaterials is presented in Table 1.

Comparison of traditional and AI-driven approaches in the synthesis and application of dental biomaterials.

| Parameter | Traditional approaches | AI-driven approaches | Dental-specific advantages of AI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material synthesis | Trial-and-error testing of resin/filler ratios (e.g., resin composites, glass ionomers) | ML predicts optimal resin-filler combinations to balance strength, shrinkage, and flowability (e.g., KNN for resin composites) | Can reduce polymerization shrinkage in resin composites by 30–40 % |

| Mechanical durability | Static testing (e.g., flexural strength) under lab conditions | DL models simulate dynamic fatigue (e.g., occlusal forces, thermocycling) | Can predict 5-year wear resistance of ceramics (e.g., zirconia crowns) with 90 % accuracy |

| Interfacial bonding | Empirical adhesive testing (e.g., µTBS of dentin adhesives) | ML identifies key factors (e.g., MDP, pH) for bond strength | Can optimize adhesives for saliva-contaminated environments, reducing debonding risks by 50 % |

| Aging in oral environment | Accelerated aging tests (limited to lab conditions like pH 4–7) | PINNs model degradation under pH fluctuations, enzymatic activity, and biofilm stress | Can predict marginal leakage in resin restorations under acidic oral conditions (pH 3.5–6.5) |

| Aesthetic customization | Manual shade matching for ceramics/resins | DL analyses patient-specific enamel translucency and color gradients from intraoral scans | Can generate aesthetic crowns with natural enamel-like light transmission (e.g., gradient-index AI designs) |

| Biofilm resistance | Static antibacterial testing (e.g., agar diffusion assays) | AI optimizes nanoparticle size/charge for targeted antibiofilm activity (e.g., Ag/ZnO) | Can predict biofilm inhibition on orthodontic brackets with 85 % accuracy (Section 5.4) |

| Biocompatibility and bioactivity | In vitro cytotoxicity tests (e.g., fibroblast viability) | ML predicts immune response to ions (e.g., fluoride, Ca2+) released from bioactive materials | Can synthesize bioactive cements with controlled ion release to promote dentin remineralization |

| Patient-specific design | Standardized implants/crowns adjusted manually | Topology optimization + generative AI creates patient-specific geometries (e.g., CBCT-guided implants) | Can reduce implant failure rates by 25 % through stress distribution matching jawbone anatomy |

| Sustainability | High waste from discarded trial formulations | AI identifies recyclable polymers (e.g., algae-based resins) and depolymerization pathways | Can reduce clinical plastic waste by 40 % |

-

Key: ML, machine learning; DL, deep learning; AI, Artificial Intelligence; KNN, k-nearest neighbors; µTBS, micro-tensile bond strength; MDP, 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate; PINNs, physics-informed neural networks; Ag/ZnO, silver/zinc oxide; CBCT, cone-beam computed tomography; pH, acidity/alkalinity level; Ca2+, calcium ions; %, percentage.

4 Challenges and limitations in dental biomaterials synthesis and application

The use of AI in dentistry is still emerging, and its application to dental biomaterials synthesis and development is entirely novel [74]. While offering transformative potential, this integration faces key challenges, including data quality, model generalizability, high computational demands, and the absence of standardized methodologies.

4.1 Data quality and availability

A major barrier to AI in dental biomaterials is the scarcity of high-quality, standardized datasets [75]. Data are fragmented across institutions, clinics, and industry, often in inconsistent formats, hindering aggregation and analysis. Experimental data for novel biomaterials, like bioactive glasses or high-entropy ceramics, are limited due to costly and time-consuming synthesis. Small datasets, such as the 81 adhesives analyzed by Wang et al. [58], risk overfitting and reduce model reliability. Labeling data for AI training, e.g., correlating micro-CT scans with fracture resistance, is labor-intensive and subjective. Proprietary industry data further limit diversity for academic research, while the complex structures of biomaterials demand ML models capable of capturing detailed, accurate insights [18].

4.2 Generalizability of AI models

AI models trained on narrow datasets often fail to generalize across materials or clinical scenarios [76]. Models optimized for one material class (e.g., resin composites) may not translate to others (e.g., zirconia ceramics). Therefore, variations in chemical composition, fabrication techniques, and degradation pathways necessitate material-specific retraining. Models validated in controlled laboratory settings may underperform in real-world environments due to factors like salivary pH fluctuations, occlusal forces, or patient-specific biofilm communities. Additionally, the predictive models based on accelerated aging tests (e.g., thermocycling) may not fully capture long-term clinical outcomes, such as the interfacial debonding of implants under dynamic loading.

4.3 Computational complexity and cost

The resource-intensive nature of AI workflows poses practical barriers. Training DL models (e.g., CNNs for microstructural analysis) demands high-performance GPUs, which are cost-prohibitive for many dental research labs. For example, topology optimization of scaffold designs requires extensive finite element simulations, increasing computational overhead. Since dental clinicians/researchers often lack computational skills to implement advanced AI techniques like Bayesian optimization or GA, necessitating interdisciplinary collaboration. Additionally, large-scale AI training consumes significant energy, raising sustainability concerns [74].

4.4 Lack of standardization

The lack of standardized frameworks hinders reproducibility and benchmarking in AI research. Variability in protocols, data formats, and methodologies complicates model training and generalization [17]. Algorithms are often chosen arbitrarily – e.g., SVMs or ANNs – without proper justification or benchmarking, limiting comparability across studies [77], 78]. Diverse reported metrics (accuracy, AUC, F1-score) and incomplete details on training data or hyperparameters further restrict replication [79], 80]. FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) are rarely applied in dental biomaterials AI research, exacerbating these issues [25], 81]. Addressing these challenges requires collaborative efforts to establish open-data repositories, validate models in diverse clinical settings, and adopt standardized reporting guidelines. Interdisciplinary collaboration between materials science, dentistry, and computer science is essential to translate AI-driven innovations from conceptual potential to tangible clinical impact.

5 Future directions

By synergizing AI with emerging technologies and prioritizing sustainability, the dental biomaterials field can achieve breakthroughs in material performance, clinical efficacy, and environmental stewardship.

5.1 Integration with emerging technologies

AI integration with advanced manufacturing and digital workflows will transform dental biomaterial innovation. It can optimize printing parameters for zirconia, resins, and bioactive ceramics, reducing defects and enhancing strength. Reinforcement learning can adjust laser power in selective laser sintering for lattice implants, while generative design and topology optimization can enable patient-specific crowns and bridges. AI-powered 3D printing can produce gradient-index composites mimicking enamel, and virtual simulations using sensor data can allow preemptive formulation adjustments. Augmented Reality overlays of predicted material performance can guide clinicians in selecting optimal biomaterials.

5.2 Enhancing predictive models for clinical applications

To maximize AI’s potential in dental biomaterials, predictive models must move beyond controlled labs and reflect the complexity of the oral cavity. Future systems should be context-aware, integrating multimodal data across three domains: clinical parameters (e.g., salivary pH, occlusal loading, bruxism), imaging data (CBCT, micro-CT, OCT), and biological profiles (microbiome, immune responses, genetics). This integration allows patient-specific predictions of material behavior. For instance, combining microbiome data with bite force can help estimate resin composite degradation and restoration wear in patients with acidic environments and heavy masticatory loads.

5.2.1 Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs)

Traditional Neural Networks typically require large datasets and may fail to incorporate core scientific principles. PINNs address this limitation by embedding fundamental physical laws, such as stress-strain relationships, heat transfer equations, and diffusion kinetics directly into the training process, thereby improving model accuracy and generalizability in material behavior prediction [82], 83]. This hybrid approach allows models to make more accurate and physically plausible predictions, even with limited experimental data [84]. In dental biomaterials, PINNs can be used to model fatigue crack propagation in ceramic restorations under cyclic loads, predict wear-induced surface topography changes in resin composites, or simulate ion release from bioactive glass-based materials in response to fluctuating oral pH levels.

5.2.2 Longitudinal predictive analytics

Time-based modeling is essential for predicting the long-term performance of dental biomaterials. Recurrent neural networks and their more advanced variant, long short-term memory networks, can analyze sequential clinical data collected over months or years. These models can forecast material degradation trends, identify early warning signs of failure, and support the development of maintenance schedules tailored to individual patients. For instance, a recurrent neural network trained on longitudinal data from electronic health records can predict the risk of marginal discoloration in resin-based restorations or forecast the likelihood of peri-implantitis in patients with specific implant designs and peri-implant tissue profiles. Such insights enable clinicians to make proactive, evidence-based decisions about material replacement or preventive interventions.

5.3 AI for personalized dental biomaterials

Artificial Intelligence is paving the way for a new era in dentistry in which biomaterials are no longer standardized but are instead tailored to the unique biological and behavioral profiles of individual patients. This personalized approach has the potential to significantly enhance material longevity, biocompatibility, and therapeutic outcomes.

5.3.1 Genomics-guided material selection and design

Advancements in dental genomics have revealed polymorphisms in genes such as MMP1, MMP9, and DSPP that influence collagen degradation, inflammatory responses, and mineralization capacity. AI algorithms can analyze these genetic markers to predict a patient’s susceptibility to adhesive failure, pulpitis, or secondary caries. For instance, ML models can guide the selection of adhesive systems with enhanced enzymatic resistance or recommend primers containing MMP inhibitors for individuals with high collagenolytic activity. Such precision-guided decisions can improve the durability of dentin bonding in patients genetically predisposed to matrix degradation.

5.3.2 Intelligent, environment-responsive materials

AI can facilitate the synthesis and formulation of adaptive dental materials capable of dynamically responding to changes in the oral environment, thereby enhancing clinical performance in real time. AI-optimized hydrogels can be engineered to release antimicrobial or remineralizing agents when exposed to acidic pH conditions, triggered by cariogenic biofilms. Additionally, integrating AI feedback from wearable occlusal sensors, restorative materials can be developed to alter their mechanical properties, such as elastic modulus or energy dissipation capacity, in response to high-stress events like bruxism. This adaptive behavior can reduce the risk of bulk fracture or marginal breakdown.

5.4 AI in the development of smart and sustainable dental biomaterials

Beyond clinical functionality, the future of dental biomaterials lies in sustainability and multifunctionality. AI can synthesize and formulate next-generation dental biomaterials that are not only smart but also sustainable, eco-conscious, and resource-efficient. AI-powered generative design tools can engineer polymer networks with dynamic covalent chemistry, such as Diels-Alder or disulfide bonds that facilitate autonomous healing of microcracks caused by masticatory fatigue or thermal cycling. Furthermore, AI can optimize polymer recycling processes for recovering monomers from used dental restorations, facilitating circular recycling of temporary crowns, dentures, and aligners, thereby contributing to the reduction of clinical plastic waste and promoting sustainability in dental practice.

Inspired by nature, AI can simulate molecular interactions to identify renewable, plant-based alternatives to petroleum-derived dental polymers. For instance, lignin-derived epoxy systems or alginate-based scaffolds can be computationally optimized for adhesion, mechanical strength, and biocompatibility. Additionally, algae-derived hydroxyapatite and cellulose nanofibers offer promising avenues for green restorative and bone-regenerative materials, with AI helping refine their structural and surface properties for enhanced integration with oral tissues.

5.4.1 Lifecycle assessment and carbon footprint optimization

AI models, such as autoencoders and neural networks, can conduct real-time lifecycle assessment analyses of dental materials. These evaluations span the entire material lifecycle, from raw material sourcing to clinical disposal. This may allow researchers to identify high-impact stages in the supply chain and develop alternative formulations with reduced environmental burdens. For example, AI-assisted screening can identify biocompatible, BPA-free monomers for dental sealants or resin composites that maintain performance while lowering toxicity and ecological impact.

5.4.2 AI-designed antimicrobial nanomaterials

Reinforcement learning algorithms can iteratively optimize nanomaterial properties such as size, charge density, and surface chemistry to selectively target cariogenic or periopathogenic biofilms. Nanoparticles like silver, zinc oxide, or graphene derivatives can be fine-tuned for maximal antimicrobial efficacy while ensuring low cytotoxicity to oral fibroblasts or pulp cells. These smart nanoparticles can be embedded in adhesives, liners, or temporary restorations to provide sustained, localized antimicrobial action.

The future of dental biomaterials lies at the intersection of AI, personalization, and sustainability. By harnessing AI’s predictive power alongside additive manufacturing and smart material technologies, researchers can develop biomaterials that not only restore function but also actively promote oral health and ecological balance. Collaborative frameworks – uniting dentists, data scientists, and environmental engineers – will be critical to translating these innovations into clinical practice, ensuring equitable access and global scalability. The broad applicability of AI across various divisions of dental biomaterials is depicted in Figure 4.

Potential applications of AI-driven design across various domains of dental biomaterials.

6 Conclusions

The integration of AI into dental biomaterials research can represent a paradigm shift in material design, optimization, and validation. By leveraging ML, DL, and advanced optimization algorithms, AI can address persistent challenges such as polymerization shrinkage, brittleness, and interfacial debonding through data-driven insights. ML models, including KNN and Decision Trees, can demonstrate exceptional accuracy in predicting mechanical properties (e.g., flexural modulus, volumetric shrinkage) and optimizing formulations by identifying key compositional factors like monomer ratios and filler content. DL techniques, such as CNNs, can enable automated analysis of microstructural defects and clinical imaging data, and can facilitate early detection of material degradation and failure risks. Optimization algorithms, including GAs and Bayesian frameworks, can accelerate the discovery of novel materials, such as high-entropy ceramics and smart polymers, by intelligently navigating vast design spaces. Collectively, AI-driven approaches can reduce reliance on costly trial-and-error approaches, enhance predictive modeling of material behavior under oral conditions, and pave the way for bioactive, self-healing, and patient-specific solutions.

While AI holds immense promise, critical gaps must be addressed to translate theoretical advancements into clinical practice. Developing AI frameworks trained on larger, standardized datasets that account for demographic diversity, dynamic oral environments, and long-term clinical outcomes. PINNs can enhance generalizability by integrating multi-modal data (e.g., genomic, microbiomic, biomechanical) and embedding material science principles. Similarly, by establishing open-access repositories for dental biomaterial data, adhering to FAIR principles, to overcome data silos and proprietary restrictions and interdisciplinary partnerships between clinicians, material scientists, and AI experts can harmonize experimental protocols and validation metrics. Additionally, by prioritizing longitudinal studies to correlate AI predictions with real-world dental material performance, including aging, biofilm interactions, and occlusal forces and simultaneously assessing the environmental impact of AI workflows can promote sustainable practices, such as recyclable polymer design and green manufacturing.

AI is poised to revolutionize dental biomaterials science, offering unprecedented precision in material synthesis, personalized therapeutic solutions, and eco-conscious innovation. By bridging computational intelligence with traditional experimental methods, AI can unlock bioactive ceramics that promote osseointegration, smart resin composites that self-repair microcracks, and biomaterials tailored to individual genetic or biomechanical profiles. However, realizing this potential demands a collaborative, patient-centric approach that prioritizes clinical relevance, sustainability, and equitable access. As AI continues to evolve, its synergy with emerging technologies such as 3D printing, digital twins, and augmented reality will redefine the boundaries of restorative, prosthetic and regenerative dentistry, ultimately enhancing the longevity, functionality, and biocompatibility of dental interventions. The future of dental biomaterials lies not in replacing human expertise but in augmenting it, empowering clinicians to deliver superior, evidence-based care in an increasingly complex oral healthcare landscape.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Funding information: None declared.

-

Data availability statement: The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

1. Hamdy, TM. Dental biomaterial scaffolds in tooth tissue engineering: a review. Curr Oral Health Rep 2023;10:14–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40496-023-00329-0.Search in Google Scholar

2. Agrawal, R, Singh, S, Saxena, KK, Buddhi, D. A role of biomaterials in tissue engineering and drug encapsulation. Proc Inst Mech Eng E. 2025;239:1626–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089221150740.Search in Google Scholar

3. Tabatabaei, FS, Torres, R, Tayebi, L. Biomedical materials in dentistry. In: Tayebi, L, editor. Applications of Biomedical Engineering in Dentistry. Cham (Switzerland): Springer International Publishing; 2019:3–20 pp.10.1007/978-3-030-21583-5_2Search in Google Scholar

4. Pandey, A. Advancements in dental materials for restorative dentistry: a focus on bioactive glass ionomer cement. Clin Res Clin Rep 2024;5:1–3.Search in Google Scholar

5. Khan, AA, AlKhureif, AA, Mohamed, BA, Bautista, LS. Enhanced mechanical properties are possible with urethane dimethacrylate-based experimental restorative dental composite. Mater Res Exp 2020;7:105307. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/abbf7f.Search in Google Scholar

6. Khan, AA, Al Kheraif, A, Jamaluddin, S, Elsharawy, M, Divakar, DD. Recent trends in surface treatment methods for bonding composite cement to zirconia: a review. J Adhes Dent 2017;19:7–19. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.jad.a37720.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Cannillo, V, Salvatori, R, Bergamini, S, Bellucci, D, Bertoldi, C. Bioactive glasses in periodontal regeneration: existing strategies and future prospects – a literature review. Materials 2022;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15062194.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Zhou, S, Sun, C, Huang, S, Wu, X, Zhao, Y, Pan, C, et al.. Efficacy of adjunctive bioactive materials in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defects: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BioMed Res Int 2018;2018–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8670832.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Motta, C, Cavagnetto, D, Amoroso, F, Baldi, I, Mussano, F. Bioactive glass for periodontal regeneration: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2023;23:264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-02898-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Sifakakis, I, Eliades, T. Adverse reactions to orthodontic materials. Aus Dent J 2017;62:20–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12473.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Hamdi, K, Elsebaai, A, Abdelshafi, MA, Hamama, HH. Remineralization and anti-demineralization effect of orthodontic adhesives on enamel surrounding orthodontic brackets: a systematic review of in vitro studies. BMC Oral Health 2024;24:1446. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-05237-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Gulabivala, K, Ng, YL. Factors that affect the outcomes of root canal treatment and retreatment – a reframing of the principles. Int Endod J 2023;56:82–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13897.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Al‐Mutairi, M, Al‐Majed, I, Khan, AA, Bari, A, Javed, R, Al‐Sadon, O, et al.. Exploring the chemical and mechanical properties of functionalized bioactive glass powder‐based experimental pit and fissure sealants. Polym Compos 2025;46:7516–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.29446.Search in Google Scholar

14. Khan, AA, Al-Khureif, AA, Al-Mutairi, M, Al-Majed, I, Aftab, S. Physical and mechanical characterizations of experimental pit and fissure sealants based on bioactive glasses. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2024;48:69–77. https://doi.org/10.22514/jocpd.2024.127.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Suwardi, A, Wang, F, Xue, K, Han, MY, Teo, P, Wang, P, et al.. Machine learning‐driven biomaterials evolution. Adv Mater 2022;34. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202102703.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Gokcekuyu, Y, Ekinci, F, Guzel, MS, Acici, K, Aydin, S, Asuroglu, T, et al.. Artificial intelligence in biomaterials: a comprehensive review. Appl Sci 2024;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156590.Search in Google Scholar

17. Kerner, J, Dogan, A, von Recum, H. Machine learning and big data provide crucial insight for future biomaterials discovery and research. Acta Biomater 2021;130:54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2021.05.053.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Xue, K, Wang, F, Suwardi, A, Han, M-Y, Teo, P, Wang, P, et al.. Biomaterials by design: harnessing data for future development. Mater Today Bio 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2021.100165.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Genin, GM, Shenoy, VB, Peng, GC, Buehler, MJ. Integrated multiscale biomaterials experiment and modeling. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2017;3:2628–32. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00821.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Alshammari, RR, Alshihah, N, Aldweesh, A. Mechanical properties of different types of composite resin used as clear aligner attachments: an in vitro study. Saudi Dent J 2025;37:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44445-025-00016-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Nicholson, JW, Sidhu, SK, Czarnecka, B. Enhancing the mechanical properties of glass-ionomer dental cements: a review. Materials 2020;13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13112510.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Priyadarshini, B, Rama, M, Chetan, VU. Bioactive coating as a surface modification technique for biocompatible metallic implants: a review. J Asian Ceram Soc 2019;7:397–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/21870764.2019.1669861.Search in Google Scholar

23. Asadi, N, Del Bakhshayesh, AR, Davaran, S, Akbarzadeh, A. Common biocompatible polymeric materials for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Mater Chem Phys 2020;242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122528.Search in Google Scholar

24. Das, P, Manna, S, Roy, S, Nandi, SK, Basak, P. Polymeric biomaterials-based tissue engineering for wound healing: a systemic review. Burns Traum 2023;11. https://doi.org/10.1093/burnst/tkac058.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Basu, B, Gowtham, N, Xiao, Y, Kalidindi, SR, Leong, KW. Biomaterialomics: data science-driven pathways to develop fourth-generation biomaterials. Acta Biomater 2022;143:1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2022.02.027.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Ren, Y, Liu, Y, Ji, T, Xu, X. AI agents and agentic AI-Navigating a plethora of concepts for future manufacturing [internet]. arXiv [Preprint] 2025. [cited 2025 Dec 24]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.01376.Search in Google Scholar

27. Pethani, F. Promises and perils of artificial intelligence in dentistry. Aus Dent J 2021;66:124–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj.12812.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Khanagar, SB, Al-Ehaideb, A, Maganur, PC, Vishwanathaiah, S, Patil, S, Baeshen, HA, et al.. Developments, application, and performance of artificial intelligence in dentistry–A systematic review. J Dent Sci 2021;16:508–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Vinoth, A, Datta, S. Computational intelligence based design of biomaterials. Comput Method Mater Sci 2022;22:229–62. https://doi.org/10.7494/cmms.2022.4.0799.Search in Google Scholar

30. Ding, H, Wu, J, Zhao, W, Matinlinna, JP, Burrow, MF, Tsoi, JK, et al.. Artificial intelligence in dentistry – a review. Front Dent Med 2023;4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdmed.2023.1085251.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Agrawal, P, Nikhade, P, Nikhade, PP. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: past, present, and future. Cureus 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27405.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Nayyar, A, Gadhavi, L, Zaman, N. Machine learning in healthcare: review, opportunities and challenges. In: Machine learning and the Internet of Medical Things in healthcare. Cambridge: Academic Press;2021:23–45 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-821229-5.00011-2Search in Google Scholar

33. Shan, T, Tay, F, Gu, L. Application of artificial intelligence in dentistry. J Dent Res 2021;100:232–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520969115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Rajasekhar, N, Radhakrishnan, T, Samsudeen, N. Exploring reinforcement learning in process control: a comprehensive survey. Int J Syst Sci 2025;56:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207721.2025.2469821.Search in Google Scholar

35. Jibon, FA, Khandaker, MU, Miraz, MH, Thakur, H, Rabby, F, Tamam, N, et al.. Cancerous and non-cancerous brain MRI classification method based on convolutional neural network and log-polar transformation. Healthcare 2022;10:1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091801.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Archana, R, Jeevaraj, PE. Deep learning models for digital image processing: a review. Artif Intell Rev 2024;57:11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-023-10631-z.Search in Google Scholar

37. Golder, S, Xu, D, O’Connor, K, Wang, Y, Batra, M, Hernandez, GG, et al.. Leveraging natural language processing and machine learning methods for adverse drug event detection in electronic health/medical records: a scoping review. Drug Saf 2025;48:321–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-024-01505-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Hossain, MR, Mahabub, S, Al Masum, A, Jahan, I. Natural language processing (NLP) in analyzing electronic health records for better decision making. J Comput Sci Technol Stud 2024;6:216–28.10.32996/jcsts.2024.6.5.18Search in Google Scholar

39. Abdalkareem, ZA, Amir, A, Al-Betar, MA, Ekhan, P, Hammouri, AI. Healthcare scheduling in optimization context: a review. Health Technol 2021;11:445–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-021-00547-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Pistikopoulos, EN, Tian, Y. Advanced modeling and optimization strategies for process synthesis. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng 2024;15:81–103. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-100522-112139.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Sosnowski, M, Krzywanski, J, Ščurek, R. Artificial intelligence and computational methods in the modeling of complex systems. Entropy 2021;23:586. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23050586.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Bagherpour, R, Bagherpour, G, Mohammadi, P. Application of artificial intelligence in tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2025;31:31–43. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.teb.2024.0022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Mallineni, SK, Sethi, M, Punugoti, D, Kotha, SB, Alkhayal, Z, Mubaraki, S, et al.. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: a descriptive review. Bioengineering 2024;11:1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11121267.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Pitchika, V, Büttner, M, Schwendicke, F. Artificial intelligence and personalized diagnostics in periodontology: a narrative review. Periodontol 2000. 2024;95:220–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12586.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Chen, W, Dhawan, M, Liu, J, Ing, D, Mehta, K, Tran, D, et al.. Mapping the use of artificial intelligence–based image analysis for clinical decision‐making in dentistry: a scoping review. Clin Exp Dent Res 2024;10. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.70035.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Heo, M-S, Kim, J-E, Hwang, J-J, Han, S-S, Kim, J-S, Yi, W-J, et al.. Artificial intelligence in oral and maxillofacial radiology: what is currently possible?. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2021;50. https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20200375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Liu, J, Zhang, C, Shan, Z. Application of artificial intelligence in orthodontics: current state and future perspectives. Healthcare 2023;11:2760. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11202760.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Lai, G, Dunlap, C, Gluskin, A, Nehme, WB, Azim, AA. Artificial intelligence in endodontics. J Calif Dent Assoc 2023;51. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424396.2023.2199933.Search in Google Scholar

49. Panahi, O. Artificial intelligence in oral implantology, its applications, impact and challenges. Adv Dent & Oral Health 2024;17:555966.Search in Google Scholar

50. Macrì, M, D’Albis, V, D’Albis, G, Forte, M, Capodiferro, S, Favia, G, et al.. The role and applications of artificial intelligence in dental implant planning: a systematic review. Bioengineering 2024;11:778. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering11080778.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Rokaya, D, Al Jaghsi, A, Jagtap, R, Srimaneepong, V. Artificial intelligence in dentistry and dental biomaterials. Front Dent Med 2024;5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdmed.2024.1525505.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Ahmed, E, Mulay, P, Ramirez, C, Tirado-Mansilla, G, Cheong, E, Gormley, AJ. Mapping biomaterial complexity by machine learning. Tissue Eng 2024;30:662–80. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.tea.2024.0067.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Suyal, M, Goyal, P. A review on analysis of k-nearest neighbor classification machine learning algorithms based on supervised learning. Int J Eng Trends Technol 2022;70:43–8. https://doi.org/10.14445/22315381/ijett-v70i7p205.Search in Google Scholar

54. Paniagua, K, Whang, K, Joshi, K, Son, H, Kim, Y, Flores, M, et al.. Dental composite performance prediction using artificial intelligence. J Dent Res 2025;104:513–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345241311888.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Zhou, X, Lu, P, Zheng, Z, Tolliver, D, Keramati, A. Accident prediction accuracy assessment for highway-rail grade crossings using random forest algorithm compared with decision tree. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2020;200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2020.106931.Search in Google Scholar

56. Kaufmann, K, Maryanovsky, D, Mellor, WM, Zhu, C, Rosengarten, AS, Harrington, TJ, et al.. Discovery of high-entropy ceramics via machine learning. npj Comput Mater 2020;6:42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0317-6.Search in Google Scholar

57. Gu, GX, Chen, C-T, Richmond, DJ, Buehler, MJ. Bioinspired hierarchical composite design using machine learning: simulation, additive manufacturing, and experiment. Mater Horiz 2018;5:939–45. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8mh00653a.Search in Google Scholar

58. Wang, R, Hass, V, Wang, Y. Machine learning analysis of microtensile bond strength of dental adhesives. J Dent Res 2023;102:1022–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345231175868.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Sarker, IH. Deep learning: a comprehensive overview on techniques, taxonomy, applications and research directions. SN Comput Sci 2021;2:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-021-00815-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Saikia, P, Baruah, RD, Singh, SK, Chaudhuri, PK. Artificial neural networks in the domain of reservoir characterization: a review from shallow to deep models. Comput Geosci 2020;135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2019.104357.Search in Google Scholar

61. Park, JH, Hwang, HW, Moon, JH, Yu, Y, Kim, H, Her, SB, et al.. Automated identification of cephalometric landmarks: part 1 – comparisons between the latest deep-learning methods YOLOV3 and SSD. Angle Orthod 2019;89:903–9. https://doi.org/10.2319/022019-127.1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Lee, J-H, Kim, D-H, Jeong, S-N, Choi, S-H. Detection and diagnosis of dental caries using a deep learning-based convolutional neural network algorithm. J Dent 2018;77:106–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2018.07.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Casalegno, F, Newton, T, Daher, R, Abdelaziz, M, Lodi-Rizzini, A, Schürmann, F, et al.. Caries detection with near-infrared transillumination using deep learning. J Dent Res 2019;98:1227–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519871884.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Ben Ishak, A. Variable selection using support vector regression and random forests: a comparative study. Intell Data Anal 2016;20:83–104. https://doi.org/10.3233/ida-150795.Search in Google Scholar

65. Cichy, RM, Kaiser, D. Deep neural networks as scientific models. Trends Cogn Sci 2019;23:305–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.01.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Vasilevich, A, Carlier, A, Winkler, DA, Singh, S, de Boer, J. Evolutionary design of optimal surface topographies for biomaterials. Sci Rep 2020;10:22160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78777-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67. Wang, X, Hoo, V, Liu, M, Li, J, Wu, YC. Advancing legal recommendation system with enhanced Bayesian network machine learning. Artif Intell Law 2024:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10506-024-09424-8.Search in Google Scholar

68. Pruksawan, S, Lambard, G, Samitsu, S, Sodeyama, K, Naito, M. Prediction and optimization of epoxy adhesive strength from a small dataset through active learning. Sci Technol Adv Mater 2019;20:1010–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14686996.2019.1673670.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Issa, R, Sorenson, R, Sparks, TD. Accelerating dental adhesive innovations through active learning and bayesian optimization [preprint]. ChemRxiv 2024. https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/662dc85a91aefa6ce19f9cfc.10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-qvpz7Search in Google Scholar

70. Zia, A, Khamis, A, Nichols, J, Tayab, UB, Hayder, Z, Rolland, V, et al.. Topological deep learning: a review of an emerging paradigm. Artif Intell Rev 2024;57:77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-024-10710-9.Search in Google Scholar

71. Koppunur, R, Ramakrishna, K, Manmadhachary, A, Kumar, DK, Sridhar, V. Topology optimization and manufacturing of maxillofacial patient specific implant using FEA and AM. Bioprinting 2025;48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bprint.2025.e00412.Search in Google Scholar

72. Saini, RS, Binduhayyim, RIH, Gurumurthy, V, Alshadidi, AAF, Aldosari, LIN, Okshah, A, et al.. Dental biomaterials redefined: molecular docking and dynamics-driven dental resin composite optimization. BMC Oral Health 2024;24:557. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04343-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Badini, S, Regondi, S, Pugliese, R. Unleashing the power of artificial intelligence in materials design. Materials 2023;16:5927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16175927.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

74. Rahim, A, Khatoon, R, Khan, TA, Syed, K, Khan, I, Khalid, T, et al.. Artificial intelligence-powered dentistry: probing the potential, challenges, and ethicality of artificial intelligence in dentistry. Digit Health 2024;10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076241291345.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75. Lwakatare, LE, Raj, A, Crnkovic, I, Bosch, J, Olsson, HH. Large-scale machine learning systems in real-world industrial settings: a review of challenges and solutions. Inf Software Technol 2020;127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2020.106368.Search in Google Scholar

76. Ong, LC, Unnikrishnan, B, Tadic, T, Patel, T, Duhamel, J, Kandel, S, et al.. Shortcut learning in medical AI hinders generalization: method for estimating AI model generalization without external data. npj Digit Med 2024;7:124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01118-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77. Haibe-Kains, B, Adam, GA, Hosny, A, Khodakarami, F, Waldron, L, Kusko, R, et al.. Transparency and reproducibility in artificial intelligence. Nature 2020;586:E14–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2766-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78. Butler, KT, Davies, DW, Cartwright, H, Isayev, O, Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018;559:547–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0337-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Powers, DMW. Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. Int J Mach Learn Technol 2011;2:37–63. https://doi.org/10.9735/2229-3981.10.9735/2229-3981Search in Google Scholar

80. Hong, Y, Hou, B, Jiang, H, Zhang, J. Machine learning and artificial neural network accelerated computational discoveries in materials science. WIREs Comput Mol Sci 2020;10. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.1450.Search in Google Scholar

81. Wise, J, de Barron, AG, Splendiani, A, Balali-Mood, B, Vasant, D, Little, E, et al.. Implementation and relevance of FAIR data principles in biopharmaceutical R&D. Drug Discov Today 2019;24:933–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2019.01.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Khalid, S, Yazdani, MH, Azad, MM, Elahi, MU, Raouf, I, Kim, HS, et al.. Advancements in physics-informed neural networks for laminated composites: a comprehensive review. Mathematics2024;13:17. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13010017.Search in Google Scholar

83. Hu, H, Qi, L, Chao, X. Physics-informed neural networks (PINN) for computational solid mechanics: numerical frameworks and applications. Thin-Walled Struct 2024;205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.112495.Search in Google Scholar

84. de la Mata, FF, Gijón, A, Molina-Solana, M, Gómez-Romero, J. Physics-informed neural networks for data-driven simulation: advantages, limitations, and opportunities. Physica A 2023;610:128415.10.1016/j.physa.2022.128415Search in Google Scholar

© 2026 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A green and sustainable biocomposite materials: environmentally robust, high performance, low-cost materials for helicopter lighter structures

- Microstructural and UCS behavior of clay soils stabilized with hybrid nano-enhanced additives

- Optimization of microstructure and mechanical properties of microwave-sintered V/Ta/Re-doped tungsten heavy alloys

- Experimental and numerical study on the axial compression behavior of circular concrete columns confined by BFRP spirals and ties

- Effect of A-site calcium substitution on the energy storage and dielectric properties of ferroelectric barium titanate system

- Comparative analysis of aggregate gradation variation in porous asphalt mixtures under different compaction methods1

- Thermal and mechanical properties of bricks with integrated phase change and thermal insulation materials

- Nonlinear molecular weight dependency in polystyrene and its nanocomposites: deciphering anomalous gas permeation selectivity in water vapor-oxygen-hydrogen barrier systems

- ZnO nanophotocatalytic solution with antimicrobial potential toward drug-resistant microorganisms and effective decomposition of natural organic matter under UV light

- Review Articles

- Granite powder in concrete: a review on durability and microstructural properties

- Properties and applications of warm mix asphalt in the road construction industry: a comprehensive review and insights toward facilitating large-scale adoption

- Artificial Intelligence in the synthesis and application of advanced dental biomaterials: a narrative review of probabilities and challenges

- Recycled tire rubber as a fine aggregate replacement in sustainable concrete: a comprehensive review

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- A green and sustainable biocomposite materials: environmentally robust, high performance, low-cost materials for helicopter lighter structures

- Microstructural and UCS behavior of clay soils stabilized with hybrid nano-enhanced additives

- Optimization of microstructure and mechanical properties of microwave-sintered V/Ta/Re-doped tungsten heavy alloys

- Experimental and numerical study on the axial compression behavior of circular concrete columns confined by BFRP spirals and ties

- Effect of A-site calcium substitution on the energy storage and dielectric properties of ferroelectric barium titanate system

- Comparative analysis of aggregate gradation variation in porous asphalt mixtures under different compaction methods1

- Thermal and mechanical properties of bricks with integrated phase change and thermal insulation materials

- Nonlinear molecular weight dependency in polystyrene and its nanocomposites: deciphering anomalous gas permeation selectivity in water vapor-oxygen-hydrogen barrier systems

- ZnO nanophotocatalytic solution with antimicrobial potential toward drug-resistant microorganisms and effective decomposition of natural organic matter under UV light

- Review Articles

- Granite powder in concrete: a review on durability and microstructural properties

- Properties and applications of warm mix asphalt in the road construction industry: a comprehensive review and insights toward facilitating large-scale adoption

- Artificial Intelligence in the synthesis and application of advanced dental biomaterials: a narrative review of probabilities and challenges

- Recycled tire rubber as a fine aggregate replacement in sustainable concrete: a comprehensive review