ZnO nanophotocatalytic solution with antimicrobial potential toward drug-resistant microorganisms and effective decomposition of natural organic matter under UV light

-

Mohd Imran

, Nasser Zouli

, Omer Y. Bakather

, Abdullah Mashraqi

, Bhagyashree R. Patil

, Mubarak A. Eldoma

, Faouzi Haouala

and Mohammad Ehtisham Khan

Abstract

This research explores the synthesis of zinc oxide nanomaterials (ZnO NMs) through the utilization of neem leaf extract, presenting an environmentally conscious and sustainable methodology. The biosynthesized ZnO NMs exhibit dual functionality, showing remarkable efficacy in the photocatalytic degradation of natural organic matter (NOM) as well as antimicrobial activity against drug-resistant microorganisms. Under low-energy UV light, ZnO effectively degraded 92 % of NOM within a span of 180 min, concurrently exhibiting substantial antimicrobial effects against Escherichia coli and Candida albicans, characterized by significant inhibition zones. The research further highlights the application of low-energy UV light to improve the photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO NMs, thereby promoting sustainability and reducing the toxicity of by-products. The characterization of ZnO NMs was conducted employing various techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV–vis), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). At a concentration of 3 g/l, ZnO accomplished a 92 % reduction in NOM over a period of 180 min, accompanied by a 59 % reduction in organic carbon deposition (OCD). The low levels presence of OCD on the surface after the reaction further confirmed the effectiveness of the process. The findings highlight the promise of neem-extract ZnO NMs as an eco-friendly and adaptable substance for environmental cleanup and antimicrobial uses, demonstrating significant antibacterial efficacy at concentrations of 0.05 mg/ml and 0.1 mg/ml.

1 Introduction

Water pollution is a major global issue, with natural organic matter (NOM) recognized as a principal contaminant in natural water sources [1], 2]. NOM consists of diverse organic molecules, including humic substances, fulvic acids, lignins, and protein components, originating from the degradation of plant and microbial materials [3], 4]. These compounds adversely affect water quality by imparting colour, odour, and taste, and they also react with disinfectants like chlorine, leading to the generation of hazardous disinfection byproducts (DBPs) [5]. Trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs), as DBPs, pose significant health hazards, including probable carcinogenic consequences [6]. The effective elimination of NOM before water disinfection is crucial for guaranteeing safe drinking water and reducing public health hazards [7].

Traditional water treatment methods, such as coagulation, sedimentation, filtering, and activated carbon adsorption, are widely employed for the elimination of NOM. These procedures sometimes fail to completely eliminate NOM or require costly chemical additions that generate secondary pollutants [8]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), particularly photocatalysis, serve as a feasible alternative due to their ability to completely decompose NOM into harmless byproducts [9]. Photocatalysis employs light energy to activate semiconductor materials like titanium dioxide (TiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO), leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that degrade organic pollutants. ZnO has attracted significant attention as a photocatalyst due to its superior photocatalytic activity, non-toxic properties, and cost-effectiveness [10], 11]. According to Naiel et al. [12], rod-shaped ZnO NPs are a highly biocompatible and promising option for biological and biomedical applications.

Although considerable investigation has been conducted on ZnO NMs, particularly regarding their photocatalytic and antimicrobial characteristics, a notable deficiency persists in the advancement of sustainable and eco-friendly synthesis techniques. Conventional approaches to the synthesis of ZnO NMs frequently utilize hazardous chemicals and energy-intensive procedures, thereby constraining their ecological viability. The utilization of plant extracts in the green synthesis of ZnO NMs has surfaced as a noteworthy alternative. Nevertheless, the majority of research has concentrated on broad plant extracts, neglecting a comprehensive investigation into the capabilities of particular plants in augmenting the dual functionality of ZnO. The current study presents a novel approach by utilizing neem leaf extract (NLE) (Azadirachta indica) for the green synthesis of ZnO NMs. This method not only promotes sustainability and environmental friendliness but also enhances the photocatalytic and antimicrobial properties of ZnO NMs. Furthermore, investigating the effectiveness of neem-extract ZnO under low-energy UV light presents an area that has not been extensively explored within the context of green-synthesized ZnO NMs. This distinctive integration of neem-extract-based synthesis with low-energy UV photocatalysis offers a compelling pathway for sustainable environmental remediation and antimicrobial applications [13], [14], [15], [16].

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a semiconductor photocatalyst that has been thoroughly investigated for its efficacy in reducing organic pollutants. The material has a broad bandgap of about 3.37 eV and demonstrates significant oxidation potential, making it appropriate for photocatalytic water treatment applications [17]. When exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, ZnO absorbs photons, resulting in the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band. This process produces electron-hole pairs [18]. Charge carriers interact with water and dissolved oxygen to generate highly unstable hydroxyl radicals (•OH), which are essential in the breakdown of complex organic pollutants, including NOM [19]. ZnO has numerous benefits compared to conventional photocatalysts such as TiO2, including superior electron mobility, lower cost, and increased photocatalytic performance under UV irradiation. However, its practical implementation has been limited by swift charge recombination and stability issues [20]. The most innovative methods for treating wastewater to recover biopolymers, vitamins, enzymes, dyes, pigments, phenolic compounds, and value-added goods, as well as to value-value waste from various industrial sources [21].

Numerous strategies have been explored to improve the efficiency of ZnO, such as surface modifications, metal and non-metal doping, alongside coupling to various semiconductors. A notably effective method is the green synthesis of ZnO NMs, enhancing photocatalytic efficiency and promoting environmental sustainability [22], [23], [24]. Conventional approaches to synthesizing ZnO NMs utilize aggressive chemicals and high-energy techniques, raising environmental and health issues. Green synthesis, or biosynthesis, provides an environmentally sustainable method by employing plant extracts, microorganisms, or biomolecules to reduce metal precursors and stabilize nanomaterials. Neem leaf (A. indica) extract has been identified as an effective reducing and stabilizing agent in the synthesis of ZnO NMs.

Neem extract, containing bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols, promotes the formation of ZnO NMs and enhances their functional properties. Neem-mediated ZnO synthesis presents multiple benefits, such as biocompatibility, which renders plant-derived ZnO NMs non-toxic and environmentally safe; enhanced stability, due to biomolecules in neem extract that inhibit agglomeration and promote better dispersion and reusability; and improved photocatalytic activity, where organic compounds from neem modify ZnO surface properties, thereby increasing light absorption and reactive oxygen species generation [25]. The use of neem-extract-mediated ZnO NMs in water treatment offers a dual advantage: it eliminates hazardous chemicals during synthesis and improves the efficiency of NOM degradation through sustainable photocatalysis [13], 26].

This research investigates the efficacy of biosynthesized ZnO NMs in water purification and antimicrobial applications. NLE was employed as a sustainable reducing agent to synthesize ZnO nano-photocatalysts, which were subsequently assessed for their effectiveness in degrading NOM under low-energy UV light. Analysis of OCD confirmed effective mineralization, illustrating an energy-efficient and scalable approach to water treatment. The antimicrobial properties of ZnO NMs were evaluated against drug-resistant pathogens. The antibacterial study demonstrated notable inhibition zones against Escherichia coli and Candida albicans at concentrations of 0.05 mg/ml and 0.1 mg/ml. The findings underscore the potential of ZnO NMs as a multifunctional material for sustainable environmental and bio-medical use.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials used

2.1.1 Leaf extract preparation

Extracts from neem plants (A. indica) were sourced from trees and thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to remove dust and top-layer contaminants. The leaves underwent air-drying at ambient temperature for 48 h to remove surplus moisture. Upon completion of the drying process, the leaves were subjected to a mechanical grinding operation to achieve a fine powder consistency. The extraction of powdered neem leaves was conducted using a hot water method. 50 grams of neem powder were boiled in 500 ml of deionized water at 80 °C for 30 min to extract bioactive compounds. Following boiling, the extract was filtered with Whatman filter paper No. 1 to eliminate solid residues, and the resulting clear filtrate was stored at 4 °C for subsequent use in ZnO NMs synthesis.

NLE serves as an effective reducing/stabilizing agent in the development of ZnO NMs. Neem extract contains polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenoids that promote the reduction of zinc ions (Zn2+) to ZnO NMs and inhibit their agglomeration. This biogenic method facilitates the creation of uniformly distributed ZnO NMs exhibiting improved photocatalytic characteristics.

2.1.2 Chemical reagents for ZnO NMs synthesis

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2•6H2O) acted as the primary chemical precursor for the production of ZnO NMs, providing the necessary Zn2+ ions for their creation. Zinc nitrate is preferred due to its considerable solubility in water and its ability to produce high-purity ZnO. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was utilised to adjust the process pH and facilitate the precipitation of ZnO NMs. The synthesis process entailed the combination of 0.1 M zinc nitrate solution with the prepared NLE while maintaining continuous stirring at 70 °C. pH ˜ 10 has been adjusted by addition of 0.1 M NaOH. The process persisted for 2 h, enabling the synthesis of ZnO NMs. The isolated residue underwent centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 10 min, was repeatedly washed with deionised water and ethanol to eliminate any unbroken impurities, and subsequently dried in an oven at 100 °C. The ZnO nanopowder was subjected to calcination at 400 °C for duration of 2 h to improve its crystallinity and photocatalytic performance.

2.2 Synthesis of ZnO NMs

2.2.1 Green procedure utilizing leaf extracts

The fabrication of ZnO NMs utilized NLE as a natural stabilizing and reducing agent. Fresh neem leaves were collected, washed with deionized water to eliminate surface impurities, and air-dried at room temperature for 48 h. The dried leaves were ground into a fine powder and extracted using the hot water method. 50 grams of neem powder were boiled in 500 ml of deionized water at 80 °C for 30 min to facilitate the release of bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols. The extract was filtered with Whatman filter paper No. 1, and the resulting clear filtrate was stored at 4 °C for later nanomaterial synthesis.

A 0.1 M aqueous solution of zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2•6H2O) was prepared for the synthesis of ZnO NMs and heated to 70 °C with continuous stirring. NLE was incrementally introduced to the zinc nitrate solution, thereby commencing the reduction process. A 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution was added dropwise to control pH and promote nanomaterial formation until the reaction mixture achieved a pH of approximately 10. The reaction was conducted at 70 °C for 2 h with continuous stirring, resulting in the gradual formation of ZnO NMs [27]. The synthesis of ZnO NMs was indicated by the gradual colour transition of the solution from pale yellow to opaque white. The bioactive components in neem extract reduced zinc ions (Zn2+) while concurrently stabilising the nanomaterials, thus reducing agglomeration. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to ambient temperature, and the ZnO precipitate was harvested for further purification and characterization (Figure 1).

Preparation method of ZnO NMs.

2.2.2 Purification/storage of ZnO NMs

Post-synthesis, the ZnO NMs were isolated from the reaction mixture via centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 10 min. The precipitate was subjected to several washings with deionised water and ethanol to eliminate unreacted contaminants and residual organic substances from the neem extract. The washing process enabled the removal of excess biomolecules that could interfere with the photocatalytic efficacy of ZnO. After purification, the ZnO NMs were dried at 100 °C in a hot air oven for 6 h to remove residual moisture. The dehydrated ZnO nanopowder was subjected to calcination at 400 °C for 2 h to augment its crystallinity and enhance photocatalytic efficacy. Calcination is crucial for eliminating residual organic compounds and augmenting the surface area of ZnO nanomaterials, hence boosting their effectiveness in photocatalytic applications. The ZnO NMs were stored in an airtight glass container at ambient temperature to prevent moisture absorption and aggregation. The biosynthesized ZnO NMs were characterized using several analytical techniques to verify their distinct features before their application in photocatalytic degradation tests.

2.3 Characterization techniques

A range of characterization techniques was utilized to assess the crystallinity, shape, elemental content, and optical characteristics of the biosynthesized ZnO NMs. The XRD pattern of the synthesized ZnO NMs displayed distinct peaks that align with the hexagonal wurtzite phase, thereby affirming the elevated level of crystallinity present in the nanoparticles. The pronounced sharpness of the peaks signifies the presence of well-defined crystalline structures, which are crucial for facilitating photocatalytic and antimicrobial functions. The size of the crystallites within the ZnO NMs was ascertained through the application of the Scherrer equation:

Where: ‘D’ represents the size of the crystallite. ‘K’ represents the shape factor, which is valued at 0.9. ‘λ’ represents the wavelength of the X-ray, measured at 1.5406 Å. ‘β’ represents the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the most significant peak, and ‘θ’ represents the angle of diffraction.

The study of the XRD peak associated with the (101) plane at a diffraction angle of 36.3° substantiates the distinctly defined crystalline structure of the synthesized ZnO NMs, thereby reinforcing their elevated level of crystallinity. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) elucidated surface shape, particle distribution, and agglomeration traits following gold sputter coating to improve conductivity. Ultraviolet-visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy assessed the optical characteristics, ascertaining the bandgap energy by Tauc’s plot and validating the photocatalytic potential of ZnO. The application of Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy demonstrated the existence of distinct Zn–O stretching vibrations, thereby validating the successful synthesis of ZnO NMs. The examination further revealed the presence of biomolecules derived from neem extract on the nanoparticle surfaces. The quantitative evaluation of the FTIR spectra indicated that although the biomolecules are present in considerable quantities, their influence on the overall characteristics of the ZnO NMs remains balanced. The intensity ratios observed between the biomolecular peaks and the ZnO-specific peaks clearly illustrate this phenomenon. The results indicate that biomolecules are crucial for the stabilization of ZnO NMs, while simultaneously preserving their photocatalytic activity, thereby ensuring their efficacy in environmental and antimicrobial applications.

2.4 Photocatalytic experimental set up

2.4.1 Reactor design and ultraviolet light source

Photocatalytic investigations were performed in a specially built batch reactor to assess the degrading efficacy of NOM utilizing biosynthesized ZnO NMs under low-energy UV radiation. The reactor consisted of a 250 ml quartz beaker, enabling consistent light penetration. A magnetic stirrer enabled the homogeneous distribution of ZnO NMs in the reaction medium. A low-energy UV light lamp (365 nm, 30 W) was placed above the reactor at a constant distance of 10 cm to guarantee uniform illumination during UV irradiation [28]. The light intensity was quantified with a UV radiometer to ensure optimal energy input. The reactor setup was enclosed in a dark chamber to prevent external light interference, ensuring that photocatalytic activity was exclusively driven by the applied UV source. A refrigeration facility was established to maintain the process temperature at ambient conditions (25 °C ± 2 °C) and to prevent thermal degradation of NOM.

2.4.2 Experimental/testing parameters

Photocatalytic experiments were conducted under different operational conditions to identify the optimal parameters for the degradation of NOM. The primary experimental factors comprised: The concentration of ZnO NMs was varied between 0.4 g/L and 3 g/L to assess its impact on photocatalytic efficiency.

The initial concentration of NOM in water was set at 20 mg/L, quantified as OCD.

The solution’s pH was adjusted to neutral (pH 7) using 0.12 M NaOH or HCl to replicate actual water treatment conditions.

The reaction was monitored over a period of 0–180 min, with samples taken at 30-min intervals to assess NOM degradation.

The solution was stirred continuously at 400 rpm to prevent nanomaterial sedimentation and improve mass transfer.

Control experiments involved conducting blank tests under the same conditions without ZnO NMs to evaluate photolysis effects, alongside dark experiments to ascertain the adsorption contribution of ZnO.

At each time interval, aliquots were withdrawn, filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane filter, and analyzed for NOM degradation via UV–vis spectroscopy at 254 nm. The OCD was assessed using an OCD analyzer, and mineralization efficiency was calculated based on the percentages of OCD removal. The degradation kinetics were examined through the pseudo-first-order kinetic model (Langmuir-Hinshelwood equation) to ascertain reaction rate constants. The experimental setup established a controlled and reproducible environment for assessing the photocatalytic efficiency of biosynthesized ZnO NMs within water purification applications.

2.5 Measurement and analysis

2.5.1 Analysis of OCD

The degree of OCD following photocatalytic degradation was evaluated to determine the effectiveness of biosynthesized ZnO NMs in eliminating NOM. OCD analysis was conducted utilizing an analyzer to measure the residual organic carbon content in treated water samples. Aliquots were withdrawn from the reaction mixture at predetermined time intervals (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min), filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane, and analyzed for OCD measurement [29]. OCD was quantified as the percentage of remaining OCD in relation to the initial NOM concentration. The degradation process was deemed effective if the OCD removal surpassed 50 %, signifying substantial mineralization of NOM. Control experiments were also performed in dark conditions to assess the role of ZnO NMs adsorption in the removal of NOM, confirming that photocatalytic degradation was the main mechanism of removal. The relationship between OCD and irradiation time was analyzed through kinetic modeling to elucidate the degradation dynamics [30].

2.5.2 Evaluation of mineralization and efficiency

The efficiency of mineralization was assessed by examining the degree of conversion of NOM into inorganic byproducts, including CO2 and H2O. The percentage of OCD removal served as an indicator of complete mineralization, offering insights into the efficacy of ZnO-based photocatalysis under low-energy UV light [31]. The evaluation of the photocatalytic system’s efficiency was conducted using the following formula: OCD Removal Efficiency (%) = [(Initial OCD – Final OCD)/Initial OCD] × 100.

Degradation Rate Constant (k) – Determined through pseudo-first-order kinetic modeling in accordance with Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics.

UV–vis spectroscopy was employed to assess the degradation of NOM at a specific absorbance wavelength of 254 nm. The decrease in absorbance over time signifies the degradation of complex organic molecules. The spectral shifts and peak disappearance observed in the UV–vis spectra provided additional confirmation of the progressive mineralization of NOM.

A comparative analysis was conducted between biosynthesized ZnO NMs and conventional ZnO to evaluate the enhancement in mineralization efficiency. Reusability tests involved the recovery and reuse of ZnO NMs across multiple photocatalytic cycles to assess their long-term stability and efficacy in the degradation of NOM.

2.6 Antibacterial/antifungal potential of biosynthesized ZnO NMs

The biosynthesized ZnO NMs were assessed for their bactericidal and fungicidal properties through the disk diffusion method against Gram-negative E. coli (ATCC 25922) and C. albicans (ATCC 10231). There were five replicates for each treatment taken in to consideration. A standardized bacterial culture was uniformly distributed on Mueller-Hinton agar plates, prepared by neutralizing the pH with 1 M NaOH and distilled water to create a 1 l solution. Three wells were constructed in each agar plate and filled with ZnO NM solutions at concentrations of 0.05 mg/ml and 0.1 mg/ml, with a control included on each plate. The plates were sealed and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to facilitate interaction between the nanomaterials and microbial cells. Following incubation, inhibitory zones were quantified to assess the antibacterial effectiveness of ZnO NMs. The antibacterial efficacy assessed by the mean inhibition zone diameter. Increased doses resulted in bigger inhibitory zones, demonstrating a dose-dependent relationship. The results illustrate the effectiveness of ZnO NMs against bacterial and fungal infections, suggesting their potential application in antimicrobial treatments.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of ZnO NMs

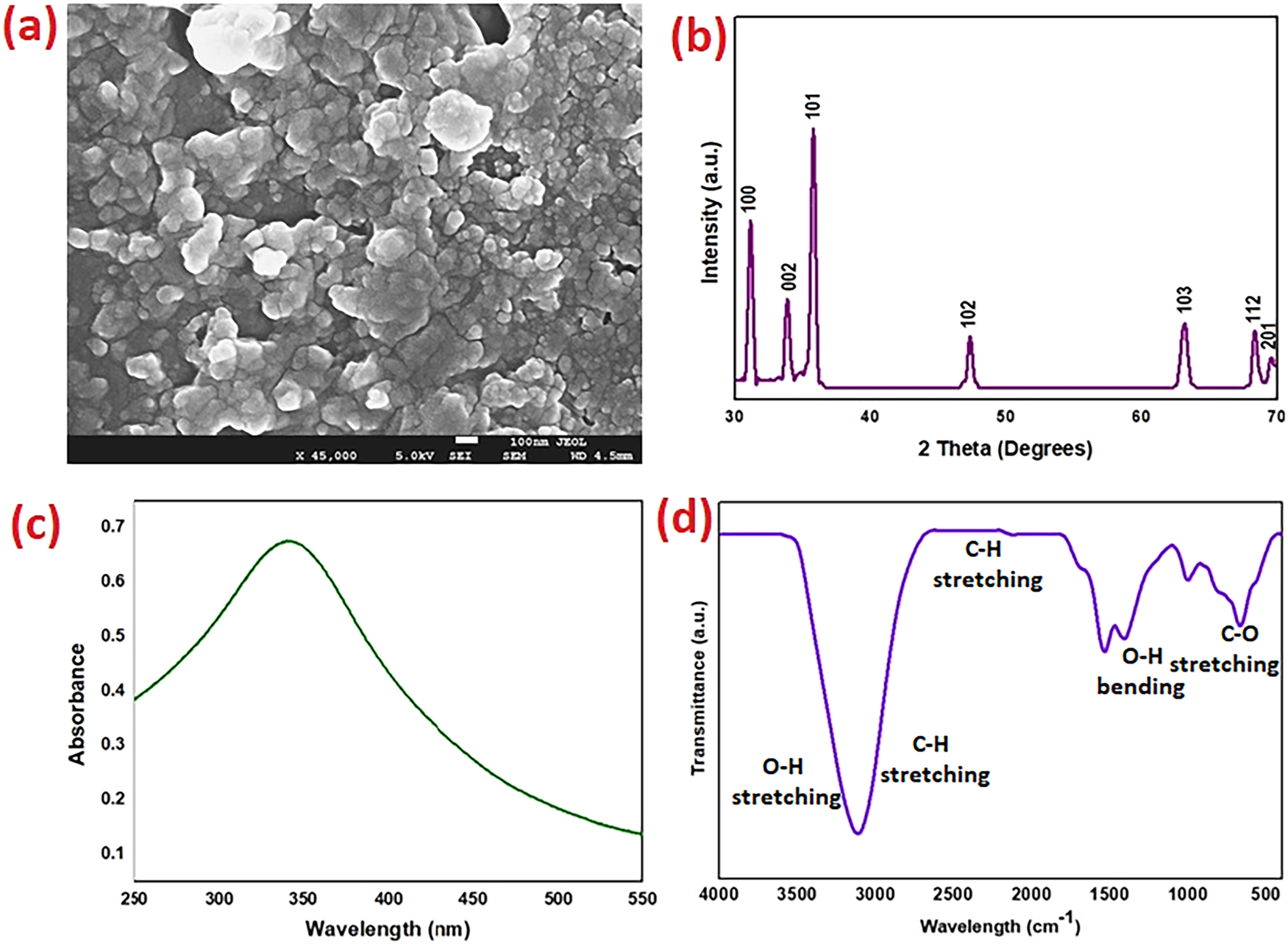

The SEM picture of ZnO NMs is directly correlated with the study’s results about the photocatalytic breakdown of NOM under low-energy UV light. The pronounced aggregation of nanomaterials and the porous surface topology depicted in the image suggest an increased active surface area, which is essential for attaining effective photocatalytic activity [32] (Figure 2a). The study demonstrates a 92 % degradation of NOM within 180 min utilizing 3 g/l of ZnO, suggesting that the synthesized nanomaterials exhibit significant photocatalytic efficiency. The efficiency is affected by the nanoscale structure, crystallinity, and defect sites in ZnO particles, which collectively enhance charge separation and the generation of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. The SEM image demonstrates that the porous and uneven shape of ZnO results in an extensive surface area, hence augmenting the adsorption of NOM molecules before photocatalytic degradation. The irregular morphology and nanomaterial clusters may facilitate light absorption and multiple scattering effects, thereby improving the efficiency of UV-induced electron-hole pair generation. The study reports a 59 % removal of OCD, indicating high mineralisation efficiency that corresponds with the anticipated performance of biosynthesized ZnO NMs. The minimal carbon residue observed on the ZnO surface after the reaction indicates that the nanomaterials possess self-cleaning properties, likely resulting from the effective oxidative degradation of organic pollutants, which results in a reduced presence of surface-adsorbed byproducts. The study underscores the significance of biosynthesised ZnO in sustainable water treatment, highlighting its potential to contribute to global environmental objectives. The morphological characteristics observed in the SEM image, including high particle density, strong interparticle interactions, and aggregated nanomaterials, indicate that biosynthesis techniques may have contributed to defect-rich ZnO surfaces, enhancing photocatalytic efficiency. The structural features likely enhance hydroxyl radical formation, facilitating more rapid and thorough degradation of NOM. The XRD pattern of the synthesized Zno NMs displays clear peaks indicative of the hexagonal wurtzite structure, consistent with JCPDS card No. 36–1451. The diffraction peaks observed at approximately 31.8° (100), 34.4° (002), 36.3° (101), 47.5° (102), 56.6° (110), 62.9° (103), and 68.0° (112) validate the crystalline structure of ZnO. These peaks’ distinct and sharp features indicate a high degree of crystallinity, suggesting that the employed biosynthetic technique produced well-structured nanomaterials with minimal amorphous content [33] (Figure 2b). The prominence of the (101) peak at roughly 36.3° signifies the thermodynamically stable wurtzite phase of ZnO. The absence of supplementary peaks in the diffraction pattern verifies the phase purity of ZnO NMs, indicating the lack of substantial impurities such as Zn(OH)2 or metallic Zn [34]. The average crystallite size can be calculated using Scherrer’s equation, which use the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the most prominent peak and the Cu Kα wavelength (0.154 nm) [35]. This assessment confirms that the synthesized ZnO NMs are within the nanometre scale, hence validating the effectiveness of the green synthesis technique. The broadening of peaks at lower angles indicates a possible occurrence of lattice strain or size-induced broadening, phenomena commonly seen in nanoscale materials. The distinct diffraction pattern signifies a low defect density and few dislocations, enhancing structural stability. The hexagonal wurtzite phase of ZnO demonstrates enhanced optical and photocatalytic characteristics, making it suitable for environmental applications such as water filtration and pollution degradation. The XRD examination reveals that the biosynthesized ZnO nanomaterials exhibit good crystallinity, phase purity, and nanoscale dimensions, making them suitable for the photocatalytic degradation of NOM in water treatment applications. UV–vis spectroscopy offers essential information regarding the optical properties, band gap, and light absorption characteristics of ZnO NMs, which directly affect their photocatalytic efficiency (Figure 2c).

Morphological and structural analysis of ZnO NMs (a) SEM image, (b) XRD analysis, (c) UV-Visible Spectrum and (d) FT-IR spectrum.

The analysis utilizing FTIR was conducted to examine the functional groups linked to the biosynthesized ZnO NMs through NLE, which served as a medium for the environmentally friendly synthesis (Figure 2d). The FTIR spectrum exhibited multiple significant absorption bands that offer important information regarding the structure and functionality of the ZnO NMs. An observable absorption band in the range of 500–600 cm−1 is indicative of the Zn–O stretching vibration, thereby affirming the successful synthesis of ZnO NMs. This peak is indicative of the Zn–O bond and confirms the successful synthesis of the ZnO NM. The extensive band noted in the 3,400 cm−1 region is ascribed to O–H stretching vibrations, which signify the presence of surface hydroxyl groups. The presence of hydroxyl groups is crucial for the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in photocatalytic reactions, which are integral to the process of pollutant degradation. Observations in the 2,800–3,000 cm−1 range correspond to C–H stretching vibrations, signifying the existence of alkyl or methylene groups derived from the NLE. These groups play a crucial role in stabilizing the ZnO NMs by inhibiting agglomeration. Furthermore, a band within the range of 1,000–1,300 cm−1 is indicative of C–O stretching, a characteristic feature of phenolic compounds and flavonoids present in the NLE. This observation implies that these biomolecules are engaging with the ZnO surface, thereby enhancing and stabilizing its photocatalytic and antimicrobial attributes. The spectrum additionally reveals peaks within the 1,400-1,600 cm−1 range, which can be ascribed to C–H bending and O–H bending vibrations, thereby reinforcing the presence of terpenoids and polyphenols on the ZnO surface. The relative intensity of the phenolic group around 3,400 cm−1 was determined in comparison to the Zn–O stretching vibration (500–600 cm−1), suggesting a moderate presence of biomolecules on the surface of the ZnO NMs. This interaction plays a vital role in ensuring the stability of the nanomaterials and improves their photocatalytic efficiency, as the biomolecules probably facilitate effective electron transfer throughout the photocatalytic process. Moreover, the lack or reduction of peaks associated with C=O, C–H, and various organic functional groups after the photocatalytic process implies that the ZnO nanomaterials demonstrate efficacy in the degradation of organic compounds, signifying successful photocatalysis. The FTIR analysis conclusively demonstrates the synthesis of ZnO NMs and offers comprehensive evidence regarding the interaction between biomolecules derived from the NLE. The interactions involved play a significant role in enhancing the stability, photocatalytic activity, and antimicrobial characteristics of ZnO NMs, thereby establishing them as a viable and sustainable choice for environmental remediation and antimicrobial purposes.

The integration of XRD, SEM, UV–vis, and FTIR characterization demonstrated that the biosynthesized ZnO NMs exhibit high crystallinity, structural integrity, and stability, alongside superior optical properties. Their elevated surface area, regulated morphology, and defect-enhanced photocatalytic activity render them highly effective for the degradation of NOM in water purification applications. The findings indicate that green-synthesized ZnO NMs provide a sustainable and efficient method for environmental remediation.

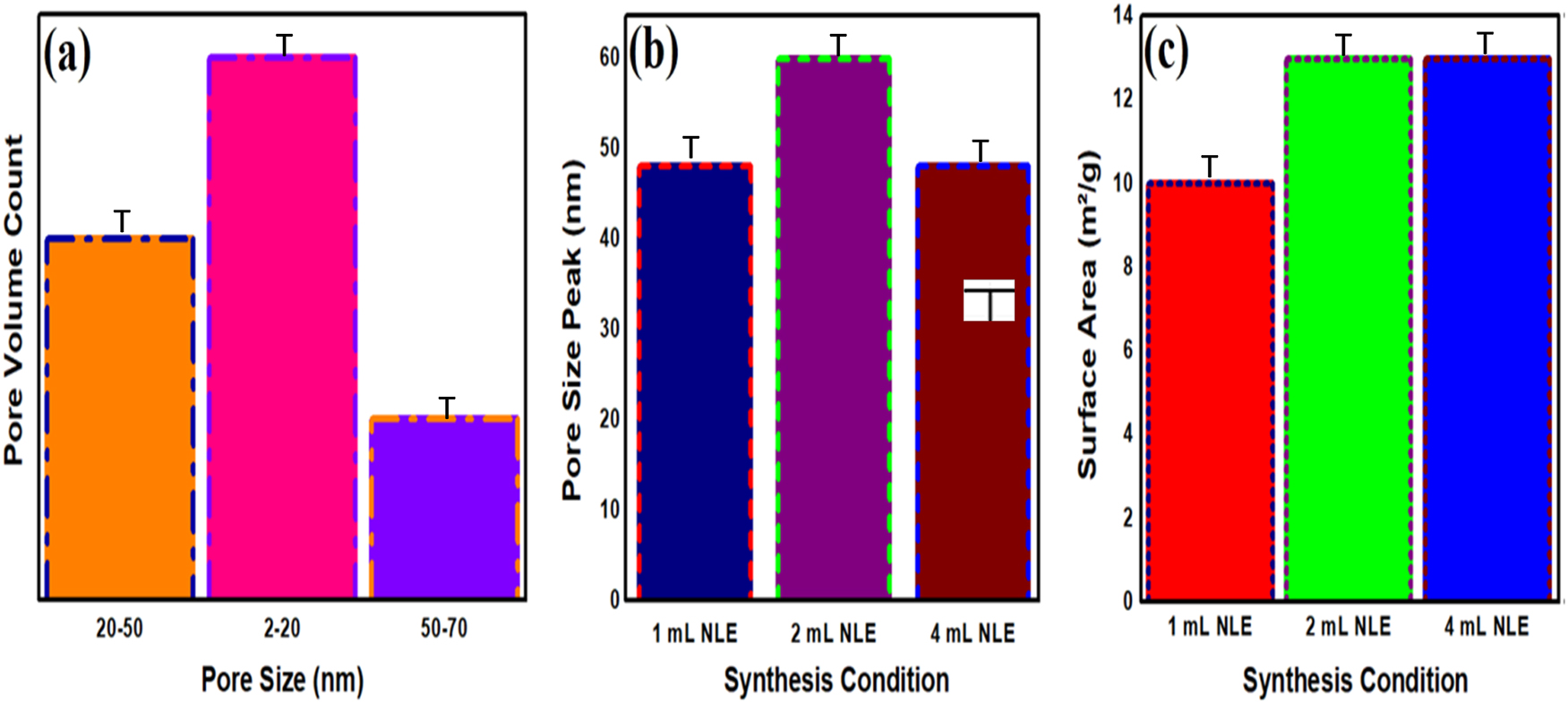

The specific surface area of the ZnO NMs was meticulously assessed through nitrogen adsorption-desorption at cryogenic temperatures (77 K), a recognized method that measures the material’s ability to hold nitrogen gas when subjected to exposure. This approach is vital for precisely evaluating the surface area accessible for chemical reactions, which plays a significant role in ascertaining the efficacy of nanomaterials in photocatalytic and antimicrobial applications. The BET analysis indicated that the ZnO NMs exhibit a mesoporous structure characterized by pores of ideal dimensions – neither overly small nor excessively large. The particular distribution of pore sizes is crucial for the materials’ capacity to effectively engage with and sequester pollutants or microorganisms, thereby improving their efficacy in environmental and biological applications. As depicted in (Figure 3a), the pore volume analysis reveals a significant abundance of pores within the 2–20 nm range, which is essential for the material’s improved engagement with organic pollutants and bacterial organisms. The mesoporosity of ZnO NMs enhances the adsorption of contaminants and promotes microbial inhibition, rendering them suitable for photocatalytic degradation and antibacterial applications. In-depth examination of the pore size distribution, illustrated in (Figure 3b), indicates that ZnO produced with 1 ml and 4 ml of NLE displays a pore size peak near 48 nm, while the sample synthesized with 2 ml NLE presents a more distinct peak at 60 nm. The observed variation in pore size suggests that the quantity of NLE employed has a direct impact on the distribution of pore sizes. This highlights the critical need for meticulous regulation of synthesis parameters to enhance adsorption capacity and facilitate better interactions with pollutants and microbial cells. The surface area of the ZnO NMs was determined to be 13 m2/g for samples synthesized using 2 ml and 4 ml of NLE, as illustrated in (Figure 3c). This value significantly surpasses the 10 m2/g recorded for the sample produced with 1 ml NLE. An expanded surface area is essential for enhancing photocatalytic activity, as it amplifies the quantity of accessible active sites for light absorption. The augmentation of surface area consequently results in a heightened production of ROS, which play a crucial role in the effective degradation of organic pollutants. The increased surface area facilitates more effective interactions between the ZnO NMs and bacterial cells, thereby enhancing their capacity to engage with and inhibit or eliminate the microorganisms. The distinctive interplay of enhanced surface area and mesoporosity renders ZnO NMs exceptionally suitable for various environmental and antimicrobial applications. Moreover, the integration of NLE markedly improves the structural and functional characteristics of the ZnO NMs, rendering them a superior option for sustainable environmental remediation and antimicrobial applications [36], 37].

BET surface area analysis for ZnO NMs (a) pore volume, (b) pore size and (c) surface area.

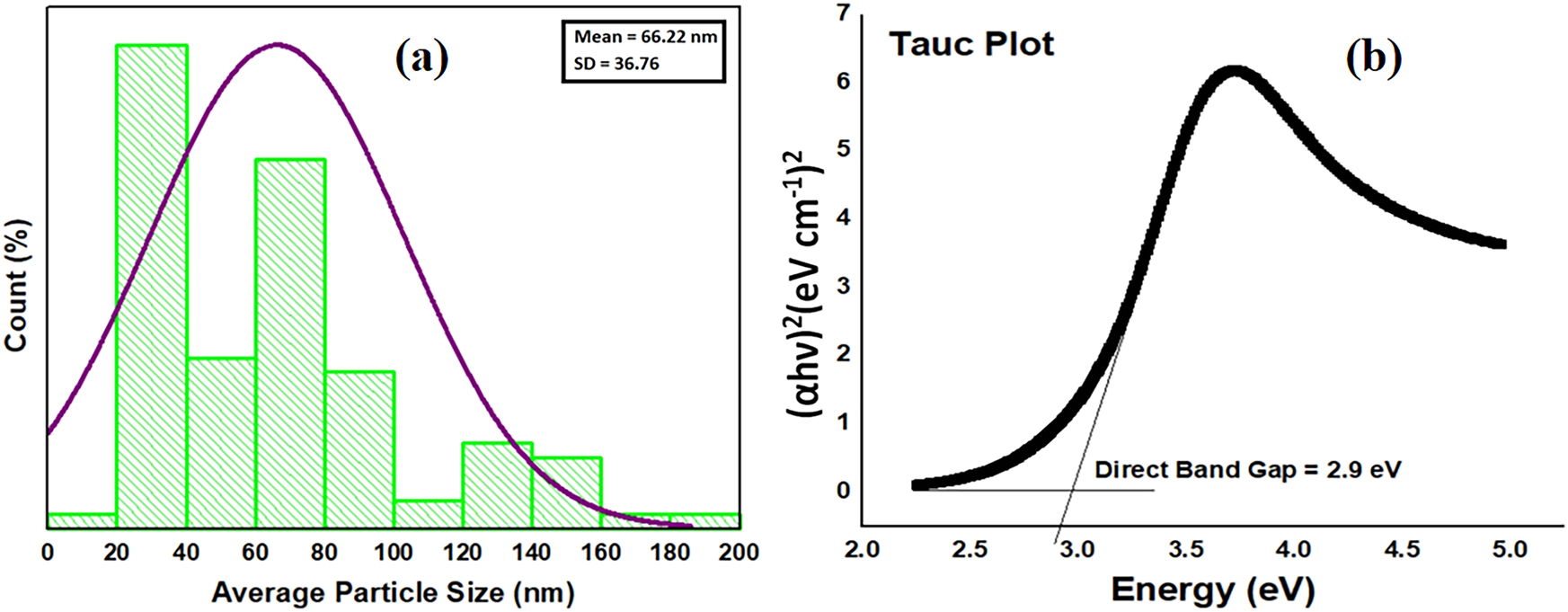

The histogram depicting the particle size distribution of green-synthesized ZnO NMs indicates an av. particle-size of 66.22 nm with a standard deviation of 36.76 nm (Figure 4a). The distribution reveals a polydisperse characteristic, with the majority of particles situated in the 20–100 nm range. The presence of particles exceeding 100 nm indicates a certain level of aggregation. The curve overlay indicates a near-lognormal distribution, which is a prevalent characteristic in nanomaterial synthesis. The small size and extensive distribution of ZnO NMs indicate a high surface area, rendering them suitable for photocatalytic applications, including the degradation of natural organic matter in water treatment. Although a significant decrease in the bandgap of the biosynthesized ZnO NMs was noted through Tauc Plot (2.9 eV in contrast to the standard 3.37 eV for bulk ZnO), the size of the nanoparticles (∼66 nm) is excessive to exhibit considerable quantum confinement effects, which are generally seen in particles that are smaller than 10 nm. Consequently, the observed decrease in the bandgap is presumably attributable to various factors, including the existence of surface defects, oxygen vacancies, or modifications in the crystal structure of ZnO that are instigated by the green synthesis methodology. The aforementioned factors may lead to the emergence of localized states within the bandgap, resulting in a reduction of the bandgap and an improvement in photocatalytic activity. The reduction in bandgap enhances photocatalytic efficiency by enabling the absorption of light across a wider spectrum of the UV-visible range. The observed shift in the absorption edge towards longer wavelengths may suggest the presence of oxygen vacancies or defect states, which are recognized for enhancing visible-light absorption and increasing photocatalytic activity. The observed characteristics indicate that the decrease in the bandgap is primarily influenced by structural and electronic alterations occurring during the green synthesis process (Figure 4b), as opposed to quantum confinement effects. The biosynthesized ZnO NMs exhibit improved optical and electronic properties, making them especially appropriate for environmental applications, including water purification and pollutant degradation. The study illustrates the efficacy of low-energy UV irradiation in facilitating photoexcitation in ZnO, resulting in the generation of electron-hole pairs (e− – h+) that play a crucial role in the degradation of NOM. The capacity of these ZnO NMs to absorb and activate in response to low-energy UV light further substantiates their potential utility in sustainable photocatalytic applications. Green synthesis of ZnO NMs has gained significant attention due to its environmentally friendly nature and its ability to produce nanomaterials with enhanced properties. Recent studies have demonstrated the use of plant extracts, such as neem, to synthesize ZnO NMs with improved photocatalytic and antimicrobial activities, highlighting the sustainability and efficiency of these approaches. Recent research has further demonstrated the benefits of green-synthesized ZnO in a range of applications, including wastewater treatment and antimicrobial treatments [38], [39], [40].

Size distribution and optical properties of ZnO NMs. (a) Particle size distribution and (b) Tauc plot.

3.2 Photocatalytic degradation of natural organic matter

3.2.1 Impact of ZnO dosage on degradation

The influence of ZnO NM dosage on the degradation efficiency of natural NOM was examined by adjusting the ZnO concentration from 0.4 to 2.2 g/l, with all other parameters held constant (Figure 5A). The findings indicated a notable enhancement in degradation efficiency with increasing ZnO dosage up to 1.7 g/l, after which the efficiency stabilized. The maximum OCD removal of 79.2 % was attained at a concentration of 1.7 g/l within 180 min, suggesting the optimal loading of the photocatalyst (Figure 5A). At lower dosages (1.61 g/l), the degradation rate was diminished due to insufficient active sites for the breakdown of NOM (Figure 5B).

Photodegradation study. (A) Degradation efficiency vs ZnO dosages, (B) time equilibrium study and (C) error bar graph of degradation efficiency vs ZnO dosages.

At a concentration of 2.2 g/l, the efficiency experienced a slight decline, presumably attributable to increased nanomaterial aggregation, which reduced the effective surface area and light penetration. The results highlight the importance of optimizing ZnO dosage to enhance photocatalytic performance while reducing material consumption and operational expenses. To ensure the reliability and robustness of the data, all photocatalytic experiments were performed in triplicate. Each measurement was repeated independently three times to account for experimental variability, and the data presented reflect the average of these three trials. Error bars, representing the standard deviation, are included in all figures to visually illustrate the variability and consistency of the results across replicates. These error bars provide insight into the degree of experimental variability and the precision of the data (Figure 5C). Statistical analysis was performed to assess the significance of the observed differences. The comparison of photocatalytic efficiencies at different ZnO concentrations revealed a significant trend, with p-values less than 0.05 for all comparisons. Specifically, the increase in efficiency with ZnO concentration up to 1.7 g/l and the slight decrease observed at 2.2 g/l were statistically significant. This indicates that the optimal ZnO dosage is approximately 1.7 g/l, beyond which no further significant improvement in photocatalytic efficiency is observed.

ZnO NMs are well-known for their photocatalytic capabilities, but comparative analyses have revealed that titanium dioxide (TiO2), silver-doped ZnO (Ag/ZnO), and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) have distinct performance characteristics. TiO2, a widely studied photocatalyst, typically requires high-energy UV light (UV–C) for effective degradation, while ZnO exhibits greater efficiency under lower-energy UV light. The high recombination rates of charge carriers in TiO2 can limit its photocatalytic efficiency, while ZnO shows enhanced electron mobility and reduced recombination rates due to its nanostructure. Silver doping in ZnO (Ag/ZnO) can improve photocatalytic performance by facilitating charge separation, but it introduces additional complexity, cost, and raises environmental concerns due to potential metal leaching in aqueous environments, making the sustainability of Ag/ZnO questionable. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) offers high photocatalytic stability but suffers from low charge-carrier mobility, restricting its overall efficiency. Green synthesis methods using NLE offer a cost-effective and sustainable route to produce ZnO nanoparticles, which demonstrate superior photocatalytic degradation of natural organic matter (NOM) under low-energy UV irradiation while avoiding toxic chemicals. The performance of green-synthesized ZnO compares favorably with TiO2, Ag/ZnO, and g-C3N4 in terms of efficiency and environmental sustainability. Green-synthesized ZnO achieved a 92 % degradation of NOM within 180 min. The use of plant extracts like neem aligns with green chemistry principles, minimizing hazardous chemicals and enhancing eco-friendliness. Furthermore, green synthesis provides a more biocompatible and economically viable approach compared to traditional methods, with various plant extracts showing adaptability in producing ZnO nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activity. The morphology and crystal structure of these nanoparticles can be confirmed using techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Surface modification of ZnO nanoparticles with Ag can further enhance their photocatalytic performance by promoting efficient charge separation. ZnO composites, such as ZnO/TiO2 hetero-structures, also show promise for improving light absorption and charge separation efficiency. Overall, green-synthesized ZnO nanoparticles present a sustainable and efficient alternative for photocatalytic applications, and further research in this area can lead to the design of highly effective and environmentally friendly photocatalytic materials [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53]. The results of the current investigation indicate that ZnO attained a 92 % degradation of NOM within a time frame of 180 min, demonstrating a commendable performance when evaluated against these materials in relation to efficiency and environmental sustainability. Table 1 presents a comprehensive details associated with a range of photocatalysts, such as TiO2, ZnO, Ag/ZnO, g-C3N4, and green-synthesized ZnO NMs, accompanied by pertinent references.

Comparison of photocatalytic properties of different materials.

| Aspect | Details | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Photocatalytic capabilities | ZnO nanoparticles are well-known for their photocatalytic capabilities, with TiO2, Ag/ZnO, and g-C3N4 showing distinct performance characteristics | [41], 42] |

| Efficiency under UV light | TiO2‚ typically requires higher-energy UV-C light, while ZnO works better under lower-energy UV light | [41] |

| Charge recombination rates | TiO2‚ suffers from high recombination rates, reducing its photocatalytic efficiency, while ZnO exhibits enhanced electron mobility and lower recombination rates | [42], 43] |

| Silver doping in ZnO (Ag/ZnO) | Ag doping improves photocatalytic performance but introduces environmental and cost concerns due to metal leaching | [44] |

| Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) | g-C3N4 has high photocatalytic stability but suffers from low charge-carrier mobility | [42] |

| Green synthesis using neem leaf extract | Green synthesis methods using neem leaf extract provide a sustainable way to produce ZnO nanoparticles | [45] |

| Performance comparison with TiO2, Ag/ZnO, g-C3N4 | Green-synthesized ZnO performs better than TiO2, Ag/ZnO, and g-C3N4 in terms of efficiency and environmental sustainability | [44], 45] |

| Degradation efficiency (NOM) | Green-synthesized ZnO achieved 92 % degradation of NOM within 180 min | [46] |

| Use of plant extracts for synthesis | Plant extracts like neem align with green chemistry principles by minimizing the use of toxic chemicals | [48], [49], [50] |

| Biocompatibility and sustainability | Green synthesis is biocompatible and economically viable, reducing environmental contamination | [48], 51] |

| Surface modification of ZnO with Ag | Surface modification with Ag nanoparticles can enhance ZnO’s photocatalytic performance by promoting charge separation | [46], 52] |

| ZnO composites (ZnO/TiO2‚ heterostructures) | ZnO/TiO2 composites improve light absorption and charge separation efficiency for photocatalytic applications | [38], 53] |

3.2.2 Impact of low-energy UV light on decomposition rate

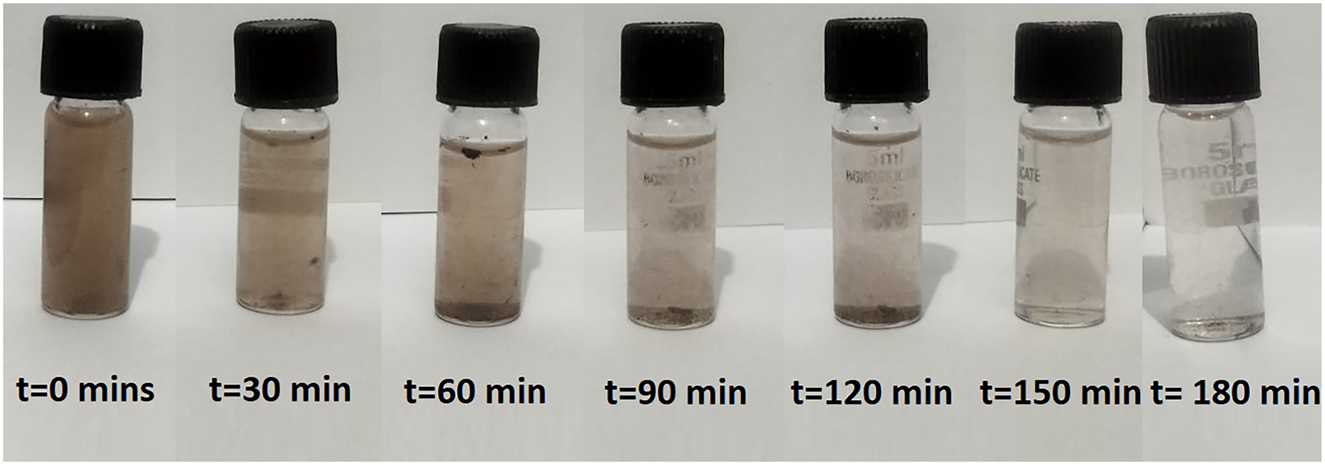

The impact of low-energy UV light on the degradation of NOM was assessed by analysing photocatalytic performance across various irradiation conditions. The experiments were performed under low-energy UV light (365 nm, 30 W) and in dark conditions to distinguish between photolytic and adsorptive removal mechanisms [54] (Figure 6).

Digital image of degradation of NOMs solution with time.

The results indicated that NOM degradation under low-energy UV light was significantly greater than in dark conditions (Table 2). Under irradiation, approximately 92 % degradation of NOM occurred within 180 min, while in the absence of low-energy UV light, only 42 % removal was achieved. This indicates that adsorption contributed to NOM reduction, but was not the primary mechanism.

OCD removal efficiency across varied conditions.

| Condition | OCD removal (%) |

|---|---|

| ZnO + UV | 75 |

| ZnO in dark | 30 |

| Control | 10 |

3.3 Kinetic analysis of photocatalytic degradation

Kinetic analysis was conducted to evaluate the efficiency of biosynthesized ZnO nanomaterials in degrading NOM. The photocatalytic degradation process adheres to a pseudo-first-order kinetic model, commonly expressed by the Langmuir-Hinshelwood equation [55]:

where:

C ο = initial concentration of natural organic matter (mg/L)

C t represents the concentration of natural organic matter at time t, measured in mg/L.

k = reaction rate constant (min−1)

t = irradiation duration (min)

The plot of ln (C0/Ct) against time exhibited a linear relationship, thereby confirming the presence of pseudo-first-order kinetics. The slope of this line represents the rate constant k.

Under low-energy UV light:

Slope = k = 0.012 min−1

This suggests an accelerated degradation process attributed to photoinduced ROS.

In low light conditions (adsorption contribution only):

Slope = k = 0.005 min−1

The markedly reduced rate indicates that adsorption alone is inadequate for efficient NOM removal.

The kinetic study demonstrated that photocatalytic degradation followed a pseudo-first-order kinetic model, with a reaction rate constant (k) of 0.012 min−1 under low-energy UV light, compared to 0.005 min−1 in darkness. This suggests that photogenerated reactive oxygen species, especially •OH, were chiefly accountable for the degradation of natural organic matter, rather than mere surface adsorption. The spectral examination of NOM degradation by UV–vis spectroscopy at 254 nm demonstrated a progressive decline in absorbance over time, consequently validating the breakdown of NOM’s aromatic structures. The results validate the effectiveness of biosynthesized ZnO NMs in photocatalytic water treatment, underscoring its potential for significant environmental remediation.

3.4 OCD and mineralization

3.4.1 Effectiveness of natural organic matter removal

The effectiveness of biosynthesized ZnO NMs in eliminating NOM was evaluated using OCD measurements. The results indicated that the efficacy of OCD elimination reached 59 % after 180 min of photocatalytic treatment with low-energy UV light. This validated the substantial mineralization of NOM, reducing the generation of detrimental DBPs in treated water. The degradation kinetics conformed to a pseudo-first-order model, with the highest rate constant (k = 0.012 min−1) seen at a ZnO concentration of 1.5 g/l. The observed decrease in OCD values over time indicates the degradation of complex NOM molecules into simpler intermediates, ultimately resulting in mineralization to CO2 and H2O. UV–vis spectroscopy corroborated this finding, indicating a notable decrease in absorbance at 254 nm, associated with aromatic NOM structures. The minimal accumulation of residual carbon on the ZnO surface suggests that photocatalytic oxidation was the predominant mechanism for the removal of NOM, rather than adsorption. The increased degradation rate under UV light indicates that reactive oxygen species, particularly hydroxyl radicals (·OH), superoxide anions (O2·-), and holes (h+), are essential in the decomposition of NOM. The main photoinduced reactions are outlined as follows:

Excitation of ZnO under UV Light:

(Here, e CB − = excited electron in the conduction band, h νB + = hole in the valence band).

Generation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH):

(Hydroxyl radicals exhibit high reactivity and directly interact with NOM molecules).

Formation of superoxide anions (O2· -):

(Superoxide anions subsequently oxidize NOM into intermediate products).

Decomposition of NOM into CO2 and H2O:

(Hydroxyl radicals effectively mineralize natural organic matter into benign products).

3.4.2 Comparative analysis of different photocatalytic systems

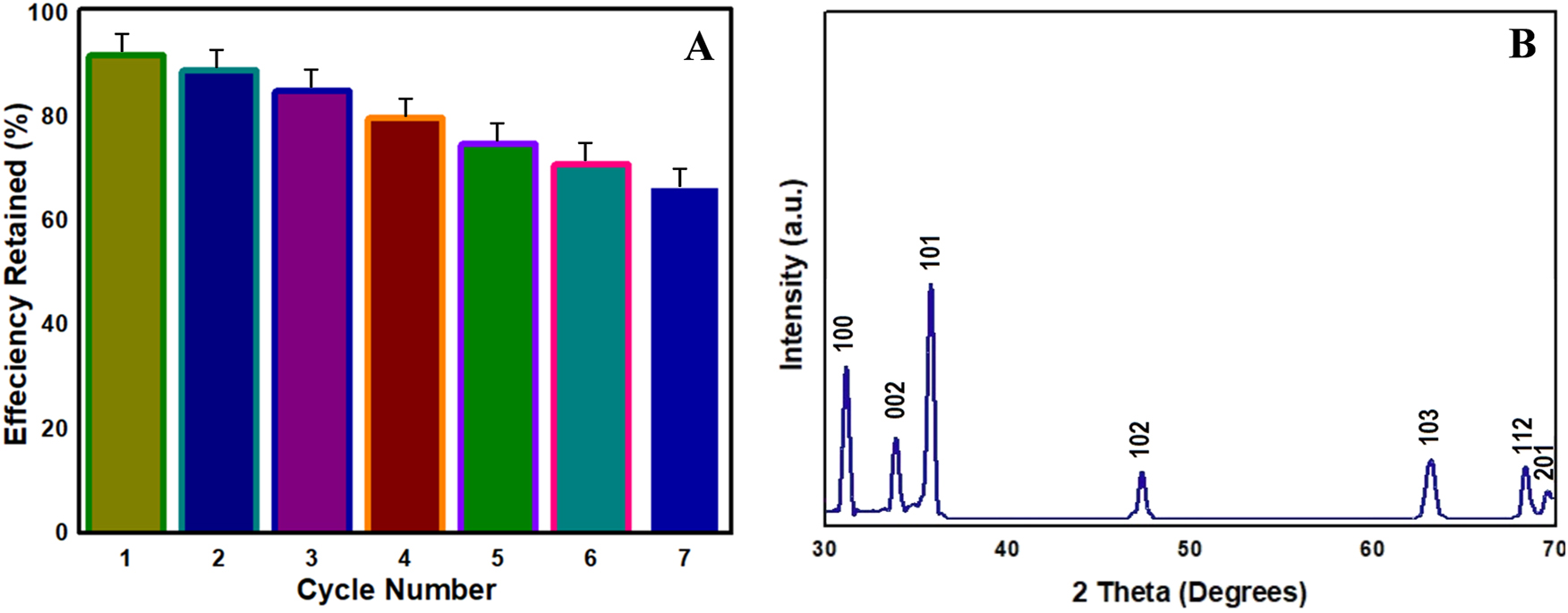

The biosynthesized ZnO NMs achieved 92 % degradation of NOM within 180 min, indicating their superior efficacy relative to traditional photocatalytic systems. Chemically synthesized ZnO frequently experiences particle agglomeration and diminished stability, which adversely affects overall degradation efficiency. The green-synthesized ZnO demonstrated improved dispersion attributed to neem-derived biomolecules, resulting in increased surface area and reactivity. ZnO NMs demonstrated superior efficiency in degrading NOM under low-energy UV illumination compared to TiO2, which necessitates higher-energy UV-C light. This characteristic positions ZnO as a more cost-effective and energy-efficient alternative. TiO2-based photocatalysis is constrained by limited spectral absorption, whereas ZnO demonstrates broader absorption and enhanced quantum yield, thereby increasing overall efficiency in water treatment applications [56], 57]. CuO-based nanomaterials demonstrate efficacy in coagulation-based removal; however, they encounter challenges related to aggregation induced by natural organic matter (NOM), which diminishes their efficiency. The biosynthesized ZnO nanomaterials demonstrated 85 % photocatalytic efficiency after five consecutive cycles, indicating significant reusability and long-term stability [58]. The green synthesis of ZnO reduces the use of toxic chemicals, lessens environmental impact, and enhances overall sustainability. Neem-mediated ZnO demonstrates high efficiency, low cost, and excellent reusability, positioning it as a suitable candidate for large-scale, eco-friendly water treatment technologies, thereby providing a sustainable solution for the degradation of NOM and the purification of wastewater.

3.5 Influence of green synthesis on ZnO NMs’ performance

3.5.1 Reusability of biosynthesized ZnO NMs’

The green synthesis of ZnO NMs using neem extract offers notable environmental and functional advantages over traditional chemical methods. These biosynthesized nanomaterials exhibit improved stability, reduced toxicity, and lower energy consumption, making them a more sustainable choice for photocatalytic applications. By using plant-based reducing agents, hazardous chemicals are eliminated, minimizing the environmental impact of nanomaterial production. Additionally, biomolecules from neem enhance the dispersion of ZnO NMs and prevent aggregation, improving photocatalytic efficiency. Reusability studies showed that ZnO retained over 85 % of its photocatalytic activity after five cycles, confirming its long-term stability. No structural degradation was observed, further demonstrating its durability for water treatment. Biosynthesized ZnO is also cost-effective, making it suitable for large-scale wastewater treatment and sustainable NOM degradation. In addition, to assess its long-term stability, the reusability study was extended to seven cycles, revealing that ZnO ZnO NMs maintained over 67 % of their initial photocatalytic activity (Figure 7A). This high reusability is essential for practical applications in water treatment. XRD analysis confirmed no significant changes in the diffraction peaks after seven cycles, indicating the preservation of the hexagonal wurtzite structure (Figure 7B). These results emphasize the excellent reusability, stability, and potential of biosynthesized ZnO for sustainable environmental applications. According to Abdelfatah et al. [59], rGO/nZVI demonstrated exceptional recycling capabilities even after six consecutive cycles, in addition to superior DC adsorption performance. As a result, rGO/nZVI formed a novel composite that is thought to be useful for the adsorption of other environmental pollutants.

Reusability and stability studies (A) Recycle test and (B) XRD analysis after 7th cycle.

3.5.2 Sustainable and economical ZnO NMs for water treatment and environmental applications

Biosynthesized ZnO NMs provide a sustainable, cost-effective, and efficient approach to water purification and environmental remediation. Their outstanding photocatalytic efficiency under low-energy UV light renders them suitable for large-scale water treatment facilities, where they can improve filtration, disinfection, and natural organic matter (NOM) degradation, thereby minimizing harmful DBPs. Nanomaterials can be incorporated into photocatalytic membranes, batch reactors, and continuous flow systems to ensure the provision of safe drinking water. The green synthesis method for ZnO avoids the use of toxic chemicals and energy-intensive processes by employing neem extract as a natural reducing agent. This leads to stable, well-dispersed ZnO NMs that exhibit improved reusability and reduced environmental impact. Furthermore, the synthesis of ZnO mediated by neem is both cost-effective and scalable, utilizing abundant and renewable plant-based resources, which lowers overall production costs while preserving high catalytic efficiency. Biosynthesized ZnO, characterized by minimal toxicity, high reusability, and a low carbon footprint, presents a sustainable and accessible alternative for addressing water pollution, industrial wastewater treatment, and broader environmental remediation efforts, thereby enhancing its global applicability in green technology solutions.

3.6 Antibacterial/antifungal potential

This study examined the antibacterial and antifungal properties of biosynthesized ZnO NMs against the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli and the fungus C. albicans. The diameters of the inhibition zones for both bacteria and fungi were assessed using the disk diffusion method (Figure 8), with the results detailed in Table 3. ZnO NMs demonstrate antimicrobial properties via three main mechanisms: interaction with bacterial cells, the release of Zn2+ ions, and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ZnO NMs, owing to their positive charge, exhibit a strong attraction to the negatively charged bacterial cell walls. The accumulation disrupts the bacterial membrane, modifies potassium channels, and results in cell death. Furthermore, Zn2+ ions interact with proteins, compromising bacterial structural integrity. The antibacterial efficacy of ZnO NMs was evaluated at concentrations of 0.05 mg/mL and 0.1 mg/mL utilizing the disk diffusion method (Table 3). Higher concentrations demonstrated increased inhibition. Nonetheless, the presence of lipopolysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria may inhibit the activity of nanomaterials, thereby diminishing their effectiveness. A direct correlation exists between ZnO concentration and antibacterial potential. With increasing dosage, there was a corresponding rise in ROS, which heightened oxidative stress and resulted in damage to bacterial membranes. The findings (Figure 8) indicate that ZnO NMs demonstrate a dose-dependent antibacterial effect, positioning them as a viable option for antimicrobial applications. With a high concentration of 2 × 108 CFU mL−1 against Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, Klebsiella pneumonia), graphene oxide nanoparticles demonstrated strong antibacterial activity [60], while zinc oxide nanoparticles demonstrated antifungal activity against C. albicans [61].

Antibacterial/antifungal studies: E. coli (left) and C. albicans (right).

Antibacterial/antifungal efficacy of biosynthesized ZnO NMs and corresponding zones of inhibition in millimeters.

| Sample concentrations (mg/mL) | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Candida albicans | |

| 0.05 mg/mL | 9 | 6 |

| 0.1 mg/mL | 12 | 8 |

ZnO NMs exhibit notable antimicrobial properties, effectively targeting microorganisms such as E. coli and C. albicans. This phenomenon is influenced by various mechanisms, with empirical evidence affirming their efficacy. A fundamental mechanism involves the production of ROS, including hydroxyl radicals, which inflict damage on microbial membranes. Upon exposure to ultraviolet or visible light, ZnO NMs generate electron-hole pairs that engage with water and oxygen, resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species. The presence of these highly reactive molecules leads to oxidative stress within microbial cells, resulting in membrane damage, the leakage of cellular contents, and ultimately culminating in cell death. In addition to the production of ROS, the liberation of Zn2+ ions from ZnO NMs plays a significant role in their antimicrobial efficacy. The interaction of these ions with microbial proteins and enzymes leads to structural alterations, which disrupt vital biological functions, consequently enhancing the bactericidal and fungicidal effects. Furthermore, ZnO NMs possess the capability to engage directly with microbial cell membranes via electrostatic attraction. The nanomaterials, possessing a positive charge, exhibit an attraction towards the negatively charged cell walls of bacteria and fungi. This interaction facilitates their potential penetration of the cell membrane, leading to destabilization and subsequent intracellular damage. The integration of these actions renders ZnO NMs exceptionally proficient in addressing microbial infections [62], [63], [64], [65].

4 Conclusions

This research illustrated the efficacy of biosynthesized ZnO NMs in the degradation of natural organic matter (NOM) when exposed to low-energy UV light. The green synthesis method employing NLE produced stable and well-dispersed ZnO NMs exhibiting improved photocatalytic properties. Characterization studies verified the hexagonal wurtzite phase, nanoscale morphology, and advantageous optical properties of the synthesized ZnO, confirming its appropriateness for water treatment applications. Photocatalytic experiments demonstrated that the degradation efficiency of NOM achieved 92 %, while the OCD removal rate was 59 % following 180 min of UV exposure. ZnO NMs demonstrated significant antibacterial and antifungal activity against drug-resistant E. coli and C. albicans. The observed inhibition zones at concentrations of 0.05 mg/ml and 0.1 mg/ml confirm their potential as antimicrobial agents. The findings underscore the dual function of ZnO nanomaterials in environmental remediation and biomedical applications, positioning them as a viable option for sustainable water treatment and management of antimicrobial resistance.

-

Funding information: This article is derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA) – Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – with grant number (12894-JAZZAN-2023-JZU-R-2-1-SE)

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Riyadh, A, Ammar, M, Peleato, NM. Natural organic matter character in drinking water distribution systems: a review of impacts on water quality and characterization techniques. Water 2024;16:446. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16030446.Search in Google Scholar

2. Anderson, LE, DeMont, I, Dunnington, DD, Bjorndahl, P, Redden, DJ, Brophy, MJ, et al.. A review of long-term change in surface water natural organic matter concentration in the northern hemisphere and the implications for drinking water treatment. Sci Total Environ 2023;858:159699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159699.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Wershaw, RL. Evaluation of conceptual models of natural organic matter (humus) from a consideration of the chemical and biochemical processes of humification. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5121; 2004.10.3133/sir20045121Search in Google Scholar

4. Feng, H, Liang, YN, Hu, X. Natural organic matter (NOM), an underexplored resource for environmental conservation and remediation. Mater Today Sustain 2022;19:100159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtsust.2022.100159.Search in Google Scholar

5. Kumar, JK, Pandit, AB. Drinking water disinfection techniques. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

6. Dubey, S, Gusain, D, Sharma, YC, Bux, F. The occurrence of various types of disinfectant by-products (trihalomethanes, haloacetic acids, haloacetonitrile) in drinking water. In: Disinfection by-products in drinking water. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford: Elsevier; 2020:371–91 pp.10.1016/B978-0-08-102977-0.00016-0Search in Google Scholar

7. Ngwenya, N, Ncube, EJ, Parsons, J. Recent advances in drinking water disinfection: successes and challenges. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2012;222:111–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4717-7_4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Marais, SS, Ncube, EJ, Msagati, TAM, Mamba, BB, Nkambule, TT. Comparison of natural organic matter removal by ultrafiltration, granular activated carbon filtration and full scale conventional water treatment. J Environ Chem Eng 2018;6:6282–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2018.10.002.Search in Google Scholar

9. Liu, H, Wang, C, Wang, G. Photocatalytic advanced oxidation processes for water treatment: recent advances and perspective. Chem Asian J 2020;15:3239–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.202000895.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Thakur, S, Ojha, A, Kansal, SK, Gupta, NK, Swart, HC, Cho, J, et al.. Advances in powder nano-photocatalysts as pollutant removal and as emerging contaminants in water: analysis of pros and cons on health and environment. Adv Powder Mater 2024;3:100233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmate.2024.100233.Search in Google Scholar

11. Baig, A, Siddique, M, Panchal, S. A review of visible-light-active zinc oxide photocatalysts for environmental application. Catalysts 2025;15:100. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15020100.Search in Google Scholar

12. Naiel, B, Fawzy, M, Mahmoud, AED, Halmy, MWA. Sustainable fabrication of dimorphic plant derived ZnO nanoparticles and exploration of their biomedical and environmental potentialities. Sci Rep 2024;14:13459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63459-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. El-Beltagi, HS, Ragab, M, Osman, A, El-Masry, RA, Alwutayd, KM, Althagafi, H, et al.. Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles via neem extract and their anticancer and antibacterial activities. Peer J 2024;12:e17588. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17588.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Kapoor, N, Singh, A, Khilari, K, Sengar, RS, Kumar, R. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles by Azadirachta indica L. and its optimization and characterizations. Int J Agric Invention 2024;9:228–35.10.46492/IJAI/2024.9.1.28Search in Google Scholar

15. Durmaz, F, Hussaini, AA, Mirza, S, Atasagun, B, Ulukuş, D, Yıldırım, M. Supercritical CO2 directional-assisted green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles obtained from Euphorbia stricta L. for functional applications. Inorg Chem Commun 2024;167:112737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112737.Search in Google Scholar

16. Hussaini, AA, Mirza, S, Ulukuş, D, Öztürk, T, Paşayeva, L, Tugay, O, et al.. Green synthesis of ZnO nanorods from Allium bourgeaui subsp. bourgeaui extract: functional applications. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2025;15:16675–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-06305-7.Search in Google Scholar

17. Abou Zeid, S, Leprince-Wang, Y. Advancements in ZnO-based photocatalysts for water treatment: a comprehensive review. Crystals 2024;14:611. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst14070611.Search in Google Scholar

18. Dagareh, MI, Hafeez, HY, Mohammed, J, Kafadi, ADG, Suleiman, AB, Ndikilar, CE. Current trends and future perspectives on ZnO-based materials for robust and stable solar fuel (H2) generation. Chem Phys Impact 2024;9:100774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chphi.2024.100774.Search in Google Scholar

19. Zeng, G, Shi, M, Dai, M, Zhou, Q, Luo, H, Lin, L, et al.. Hydroxyl radicals in natural waters: light/dark mechanisms, changes and scavenging effects. Sci Total Environ 2023;868:161533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161533.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Pan, L, Shen, GQ, Zhang, JW, Wei, XC, Wang, L, Zou, JJ, et al.. TiO2–ZnO composite sphere decorated with ZnO clusters for effective charge isolation in photocatalysis. Ind Eng Chem Res 2015;54:7226–32. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.5b01471.Search in Google Scholar

21. Kathi, S, Singh, S, Yadav, R, Singh, AN, Mahmoud, AED. Wastewater and sludge valorisation: a novel approach for treatment and resource recovery to achieve circular economy concept. Front Chem Eng 2023;5:1129783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fceng.2023.1129783.Search in Google Scholar

22. Raza, A, Sayeed, K, Naaz, A, Muaz, M, Islam, SN, Rahaman, S, et al.. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles and Ag-doped ZnO nanocomposite utilizing Sansevieria trifasciata for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2024;9:32444–54. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c10060.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Hussaini, AA, Tugay, O, Mirza, S, Ulukuş, D, Durmaz, F, Yıldırım, M. Photosensing performances of the green synthesized ZnO micro/nanorods using different parts of the Lupinus pilosus: a comparative study. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 2023;34:1991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-023-11403-9.Search in Google Scholar

24. Mirza, S, Hussaini, AA, Öztürk, G, Turgut, M, Öztürk, T, Tugay, O, et al.. Photocatalytic and antibacterial activities of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized from Lupinus albus and Lupinus pilosus plant extracts via green synthesis approach. Inorg Chem Commun 2023;155:111124.10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111124Search in Google Scholar

25. Sharma, J, Sweta, Thakur, C, Vats, M, Sharma, SK. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using neem extract. AIP Conf Proc 2020;2220:020107. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0002093.Search in Google Scholar

26. Lam, SM, Quek, JA, Sin, JC. Mechanistic investigation of visible light responsive Ag/ZnO micro/nanoflowers for enhanced photocatalytic performance and antibacterial activity. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2018;353:171–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2017.11.021.Search in Google Scholar

27. Gupta, K, Joshi, P, Gusain, R, Khatri, OP. Recent advances in adsorptive removal of heavy metal and metalloid ions by metal oxide-based nanomaterials. Coord Chem Rev 2021;445:214100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214100.Search in Google Scholar

28. Holz, K, Lietard, J, Somoza, MM. High-power 365 nm UV LED mercury arc lamp replacement for photochemistry and chemical photolithography. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2017;5:828–34. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02175.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Birben, NC, Paganini, MC, Calza, P, Bekbolet, M. Photocatalytic degradation of humic acid using a novel photocatalyst: Ce-doped ZnO. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2017;16:24–30. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6pp00216a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Awfa, D, Ateia, M, Fujii, M, Yoshimura, C. Photocatalytic degradation of organic micropollutants: inhibition mechanisms by different fractions of natural organic matter. Water Res 2020;174:115643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.115643.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Fiorenza, R, Spitaleri, L, Perricelli, F, Nicotra, G, Fragalà, ME, Scirè, S, et al.. Efficient photocatalytic oxidation of VOCs using ZnO@Au nanoparticles. J Photochem Photobiol Chem 2023;434:114232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2022.114232.Search in Google Scholar

32. Talam, S, Karumuri, SR, Gunnam, N. Synthesis, characterization, and spectroscopic properties of ZnO nanomaterials. Int Sch Res Not 2012;2012:372505.10.5402/2012/372505Search in Google Scholar

33. Ismail, MA, Taha, KK, Modwi, A, Khezami, L. ZnO nanoparticles: surface and X-ray profile analysis. J Ovonic Res 2018;14:381–93.Search in Google Scholar

34. Alshehri, R. Zinc oxides for nanopigmented coatings for electroactive anti-corrosion protection of C-steel structures [dissertation]. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

35. Muniz, FTL, Miranda, MR, Morilla dos Santos, C, Sasaki, JM. The Scherrer equation and the dynamical theory of X-ray diffraction. Found Crystallogr 2016;72:385–90. https://doi.org/10.1107/s205327331600365x.Search in Google Scholar

36. Ounis, DY, Peppel, T, Sebek, M, Strunk, J, Houas, A. Green synthesis of photocatalytically active ZnO nanoparticles using chia seed extract and mechanistic elucidation of the photodegradation of diclofenac and p-nitrophenol. Catalysts 2024;15:4. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15010004.Search in Google Scholar

37. Mutukwa, D, Taziwa, RT, Tichapondwa, SM, Khotseng, L. Optimisation, synthesis, and characterisation of ZnO nanoparticles using Leonotis ocymifolia leaf extracts for antibacterial and photodegradation applications. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:11621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252111621.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Djearamane, S, Xiu, LJ, Wong, LS, Rajamani, R, Bharathi, D, Kayarohanam, S, et al.. Antifungal properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles on Candida albicans. Coatings 2022;12:1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12121864.Search in Google Scholar

39. Aldeen, TS, Mohamed, HEA, Maaza, M. ZnO nanoparticles prepared via a green synthesis approach: physical properties, photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. J Phys Chem Solid2022;160:110313.10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110313Search in Google Scholar

40. Hoseinzadeh, E, Alikhani, MY, Samarghandi, MR, Shirzad-Siboni, M. Antimicrobial potential of synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles against Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Desal Water Treat 2014;52:4969–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2013.810356.Search in Google Scholar

41. Akhter, P, Nawaz, S, Shafiq, I, Nazir, A, Shafique, S, Jamil, F, et al.. Efficient visible light assisted photocatalysis using ZnO/TiO2 nanocomposites. Mol Catal 2023;535:112896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2022.112896.Search in Google Scholar

42. Nguyen, TTA, Dao, TCV, Vu, AT. Controlling the physical properties of Ag/ZnO/g-C3N4 nanocomposite by the calcination procedure for enhancing the photocatalytic efficiency. Ceram Int 2024;50:14292–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.01.336.Search in Google Scholar

43. Akila, K, Thambidurai, S, Suresh, N, Prabu, KM. Photocatalytic and bactericidal activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles biosynthesized with Datura metel leaf extract. Ionics 2024;30:3637–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-024-05457-w.Search in Google Scholar

44. Jandaghian, F, Pirbazari, AE, Tavakoli, O, Asasian-Kolur, N, Sharifian, S. Comparison of the performance of Ag-deposited ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles in levofloxacin degradation under UV/visible radiation. J Hazard Mater Adv 2023;9:100240.10.1016/j.hazadv.2023.100240Search in Google Scholar

45. Gemachu, YL, Birhanu, AL. Green synthesis of ZnO, CuO and NiO nanoparticles using neem leaf extract and comparing their photocatalytic activity under solar irradiation. Green Chem Lett Rev 2023;17:2293841. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518253.2023.2293841.Search in Google Scholar

46. Liu, S, Cheng, S, Zheng, J, Liu, J, Huang, M. Construction of Ag-modified ZnO/g-C3N4 heterostructure for enhanced photocatalysis performance. J Chem Phys 2024;161:154707. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0226195.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Gowri Shankari, C, Kavitha, B, Kalanithi, M. Synthesis and characterization of phytochemical fabricated Ag doped ZnO nanoparticles with Ficus benghalensis and their enhanced antibacterial and photocatalytic applications. Res J Chem Environ 2023;27:3–46. https://doi.org/10.25303/2703rjce034046.Search in Google Scholar

48. Kumar, R, Kumar, S, Kalra, N, Sharma, S, Kumar, M, Siqueiros, JM, et al.. Recent advances in green synthesis of diluted magnetic plasmonic-based semiconductor nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Hybrid Adv 2024;5:100135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hybadv.2023.100135.Search in Google Scholar

49. Velidandi, A, Sarvepalli, M, Gandam, PK, Baadhe, RR. Silver/silver chloride and gold bimetallic nanoparticles: green synthesis using Azadirachta indica aqueous leaf extract, characterization, antibacterial, catalytic, and recyclability studies. Inorg Chem Commun 2023;155:111107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111107.Search in Google Scholar

50. Pavithra, S, Mani, M, Mohana, B, Jayavel, R, Kumaresan, S. Precursor dependent tailoring of morphology and crystallite size of biogenic ZnO nanostructures with enhanced antimicrobial activity–a novel green chemistry approach. BioNanoScience 2021;11:44–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-020-00804-3.Search in Google Scholar

51. Supin, KK, Vasundhara, M. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles from neem and eucalyptus leaves extract for photocatalytic applications. Mater Today Proc 2023;92:787–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.343.Search in Google Scholar

52. Chauhan, A, Kumar, A, Singh, K, Gupta, A, Kumar, A, Sawini, S, et al.. Synthesis of ZnO/Ag hybrid nanostructures using amine functionalized ZnO for study of photocatalytic activity towards organic dyes. Phys Scripta 2025;100:075987. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ade8ae.Search in Google Scholar

53. Adam, MSS, Taha, A, Abualreish, MJA, Negm, A, Makhlouf, MM. Nanocomposite TiO2/ZnO coated by copper (II) complex of di-Schiff bases with biological activity evaluation. Inorg Chem Commun 2024;161:112144.10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112144Search in Google Scholar

54. Bouddouch, A, Akhsassi, B, Amaterz, E, Bakiz, B, Taoufyq, A, Villain, S, et al.. Photodegradation under UV light irradiation of various types and systems of organic pollutants in the presence of a performant BiPO4 photocatalyst. Catalysts 2022;12:691. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12070691.Search in Google Scholar

55. Asenjo, NG, Santamaría, R, Blanco, C, Granda, M, Álvarez, P, Menéndez, R. Correct use of the Langmuir–Hinshelwood equation for proving the absence of a synergy effect in the photocatalytic degradation of phenol on a suspended mixture of titania and activated carbon. Carbon 2013;55:62–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2012.12.010.Search in Google Scholar

56. Nawaz, R, Ullah, H, Ghanim, AAJ, Irfan, M, Anjum, M, Rahman, S, et al.. Green synthesis of ZnO and black TiO2 materials and their application in photodegradation of organic pollutants. ACS Omega 2023;8:36076–87. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c04229.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Kanakaraju, D, Sakai Yahya, M, Wong, SP. Removal of chemical oxygen demand from agro effluent by ZnO photocatalysis and photo-Fenton. SN Appl Sci 2019;1:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0782-z.Search in Google Scholar

58. Khan, R, Inam, MA, Park, DR, Khan, S, Akram, M, Yeom, IT. The removal of CuO nanoparticles from water by conventional treatment C/F/S: the effect of pH and natural organic matter. Molecules 2019;24:914. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24050914.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Abdelfatah, AM, El-Maghrabi, N, Mahmoud, AED, Fawzy, M. Synergetic effect of green synthesized reduced graphene oxide and nano-zero valent iron composite for the removal of doxycycline antibiotic from water. Sci Rep 2022;12:19372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23684-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Mahmoud, AED, El-Maghrabi, N, Hosny, M, Fawzy, M. Biogenic synthesis of reduced graphene oxide from Ziziphus spina-christi (Christ’s thorn jujube) extracts for catalytic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant potentialities. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022;29:89772–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21871-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61. Naiel, B, Fawzy, M, Halmy, MWA, Mahmoud, AED. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using sea Lavender (Limonium pruinosum L. Chaz.) extract: characterization, evaluation of anti-skin cancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant potentials. Sci Rep 2022;12:20370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24805-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Klink, MJ, Laloo, N, Leudjo Taka, A, Pakade, VE, Monapathi, ME, Modise, JS. Synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles against selected waterborne bacterial and yeast pathogens. Molecules 2022;27:3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27113532.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63. Preeti, Radhakrishnan, VS, Mukherjee, S, Mukherjee, S, Singh, SP, Prasad, T. ZnO quantum dots: broad spectrum microbicidal agent against multidrug resistant pathogens E. coli and C. albicans. Front Nanotechnol 2020;2:576342. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnano.2020.576342.Search in Google Scholar

64. Barnes, RJ, Molina, R, Xu, J, Dobson, PJ, Thompson, IP. Comparison of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and the correlated inactivation of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. J Nanoparticle Res 2013;15:1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-013-1432-9.Search in Google Scholar