Abstract

The need for energy efficiency and sustainable building materials is increasing today. In this context, new material integrations that aim to improve the thermal and mechanical performance of building elements are being investigated. This study experimentally investigated the effects of two phase change materials (PCM-1(CACI2.6H2O), PCM-2(NEXTEK24D)) and a thermal insulation material (polyurethane) on the thermal conductivity and compressive strength of hollow bricks. The internal voids of the bricks were filled with polyurethane and two different PCMs to evaluate the contributions of these additives to the mechanical and thermal behavior of the building elements. The findings indicate that adding PCM increases the bricks’ thermal resistance values and reduces internal temperature fluctuations. Bricks filled with polyurethane and FDM showed increased compressive strength, up to 28 % vertically and 74 % horizontally, compared to reference specimens. This emonstrates that filling bricks with such materials improves their compressive strength and thermal insulation. In conclusion, bricks with PCM and polyurethane additives offer significant potential for energy-efficient building solutions, particularly in terms of thermal comfort and insulation. However, given the impact of these additions on mechanical performance, further research is needed to optimize material ratios and enhance applicability without compromising structural safety.

1 Introduction

Buildings have an important place in the life of human beings. As long as life continues, buildings and buildings will be constructed in various shapes and features to meet people’s need for shelter, need to work and other needs. As well as the physical properties of the buildings determined for the intended use of the buildings, the heat control and resistance of the buildings also gain importance. Therefore, the structural elements that make up buildings must have high strength and low thermal conductivity. The energy performance of buildings regulation calls for increasingly stringent criteria for the thermal performance of buildings, including building ecology and sustainability [1]. Just as the strength of building elements affects the overall durability of buildings, the thermal conductivity coefficients of these elements play a critical role in determining the heating and cooling needs of buildings. Since walls have a large surface area in buildings, most heat loss and gain occurs through these elements. Therefore, the thermal and mechanical properties of the materials used to construct walls are important for energy efficiency and building safety [2], 3]. Bricks are widely used in modern buildings because they are lightweight and hollow. However, this structure directly affects the thermal conductivity and mechanical strength of bricks. While air voids inside bricks increase thermal insulation, they can also reduce mechanical strength. Therefore, filling the voids in bricks with suitable insulating or phase-change materials (PCMs) is being investigated as a way to improve thermal performance and mechanical strength [4]. PCMs can effectively reduce indoor temperature fluctuations thanks to their heat storage capacity. However, they should not significantly increase the weight of the brick, nor should they be costly. An increase in the weight of building elements can negatively affect design and costs, so this is important. In conclusion, improving the thermal and mechanical performance of bricks using insulation materials and PCMs is an important area of research in terms of energy efficiency and building safety. However, optimal solutions must consider the additional weight and costs these applications will introduce.

Bricks have played an important role in construction and building for thousands of years. Many researchers are developing sustainable and innovative bricks to reduce the brick industry’s carbon footprint. Due to their outstanding properties, such as durability, strength, and affordability, bricks have been an indispensable construction material for many years [5], [6], [7]. Lightweight materials are widely used in high-rise buildings to reduce their overall weight [8], 9].

Filled bricks have significantly higher compressive strength than commercial hollow bricks. Additionally, these bricks demonstrated superior resistance to thermal expansion and maintained their structural integrity at high temperatures. However, when exposed to high temperatures, the temperature increase on the outer surface of the hollow block wall occurred faster than that of the hollow brick wall. Structures made with blocks filled with rice husks or wood fibers had significantly higher coefficients of thermal transmittance than structures made with hollow blocks [10], 11]. Increased porosity makes the bricks lighter. The bricks with added tea waste had higher water absorption levels and poorer mechanical strength. Tea residues were found to significantly reduce the thermal conductivity and heat dissipation capacity of the bricks [6], 12]. While the thermal performance of bricks containing PCM is improved, a decrease in compressive strength is observed. Although the PCM layer is thermally superior to brick-based PCM capsules, there is no improvement in mechanical properties [13]. Using light bricks for thermal and sound insulation significantly contributes to building structures. Complementary building elements in this structure are cheaper than structural systems and also contribute significantly to cost savings.

PCMs are used in many applications due to their high thermal energy storage capacity. Depending on their phase change temperature ranges, PCMs are used in solar systems, building temperature control, thermal insulation, thermally regulated textile materials, water heaters, and refrigerators, among other applications [14], 15]. PCMs are integrated into concrete, plaster, plaster or prefabricated building elements [16]. PCMs store heat when changing phase from solid to liquid and release the stored heat when changing phase from liquid to solid. This property of PCMs is used as an effective way for temperature control in buildings [17]. By absorbing and releasing heat depending on the changing temperature, PCMs allow indoor conditions to be kept at the desired comfort level. This reduces the cooling and heating load and saves energy [18]. The use of PCMs, especially in buildings, contributes to reducing energy costs and plays an important role in maintaining the energy supply-demand balance [19].

Application of Thermal Insulation Material (TIM) to bricks increases thermal resistance. The use of PCM in bricks contributes to the improvement of thermal inertia. Integrating both TIM and PCM in the internal voids is considered to comprehensively improve the thermal performance of bricks in terms of thermal resistance and thermal inertia [20]. PCMs can be encapsulated by nano, micro and macro encapsulation methods and used in building components. Microencapsulation methods are generally preferred in building components. The performance of PCM-applied building components is analyzed by experimental studies or simulation results [21].

The latent heat and melting temperature of the material are the most important properties to consider when selecting PCM. The higher the latent heat retention capacity of the PCM, the higher the thermal resistance of the structural element. In addition, the phase change temperature within the thermal comfort range will reduce the temperature change. PCM stabilizes the heat flow during the day. During the day, it stores the heat generated by solar radiation and prevents the indoor temperature from rising. At night, it reduces heating costs by dissipating the stored heat energy into the structure [22]. While the amount of PCM added to the brick improves the thermal performance of the wall, this amount should be well optimized for economic and mechanical strength reasons [23].

When selecting the PCM, the average internal temperatures of the buildings and the average temperature of the region where the building is located should be taken into account. When the phase change temperature of the PCM is not within the temperature range of the building element changing during the day, the PCM will not be able to change phase. If there is no storage and return of latent heat during the phase change, only sensible heat and heat transfer will occur. Due to the absence of phase change, heat storage will not occur and this will minimize the beneficial effect of the PCM [24]. Two southern walls with and without PCM were experimentally tested and numerically modeled under natural conditions in the wall of a prefabricated building consisting of two identical rooms. In the walls with PCM, the room temperature decreased by about 4.7 °C, the delay time increased by 2 h, and the temperature fluctuation decreased by 23 [25]. In hot climatic conditions, peak temperature values decreased between 4.7 and 4.4 °C in walls containing PCM bricks [25], 26]. In a study conducted by placing paraffin wax in cylinders made of iron in perforated bricks with PCM, paraffin wax has a latent heat of 147 kJ/kg, 38 °C solid phase and 43 °C liquid phase properties. The study was carried out on four different samples. Compared to the conventional wall C1, the heat flow for C2, C3 and C4 decreased by 35.7 %, 17.4 % and 13.9 % respectively [27]. In a study with micro-encapsulated PCM placed inside the cavity brick and macro-encapsulated PCM placed on the outer wall side, the micro-encapsulated PCM on the inner wall side proved to perform better in the night use mode [28]. In the study on a paraffin-filled building block, the increase in the volume of PCM supported the optimal thermal regime of the building element, moreover, the increase in the block size led to a reduction of the maximum temperature difference at the indoor surface by around 20 % [29]. In another study, the thermal behavior of hollow bricks containing PCM was tested by creating a numerical model of the melting-solidification heat transfer process. The peak heat flux of PCM-filled brick was reduced from 45.26 W/m2 to 19.19 W/m2-21.4 W/m2 [30].

Using PCM in building components or elements gives them the heat retention capability inherent in the PCM. Thus, a building component with increased heat retention capability will not be affected by sudden temperature changes, and its temperature range will decrease temperature changes and the temperature change range of the building component will decrease [31]. Using building components with a reduced temperature change range will reduce the heating and cooling loads due to heat loss and gain. This will reduce the heating load in winter and the cooling load in summer. Therefore, the amount of energy needed to maintain comfortable indoor temperatures will decrease, as will costs due to fuel consumption. Consequently, CO2 emissions will decrease due to reduced fuel consumption.

Internal temperatures are determined by the intended use of the buildings. To maintain the specified internal temperature, energy is spent through heating and cooling systems in summer and winter conditions. In this context, more than 60 % of the energy used for temperature control is lost through heat gain or loss [32]. Furthermore, 36 % of a structure’s global energy consumption and 50 % of its direct heating and cooling loads are attributable to the building envelope [33], 34]. These materials are expected to provide high insulation performance and high heat retention capacity, respectively. These properties reduce heat transfer between buildings and the external environment, thereby reducing energy consumption [35].

In eight cities representing the Mediterranean region: Al Hoceima (Morocco), Malaga (Spain), Marseille (France), Taher (Algeria), Naples (Italy), Tripoli (Libya), Ankara (Türkiye) and Port Said (Egypt), PCM was used to reduce building cooling demands. The energy performance of three types of buildings constructed with perforated bricks with and without PCM was evaluated using a numerical model. A wide range of PCM melting temperatures were investigated (22°C-32 °C). The results show that climate affects the heat retention/release capacity of PCMs. In North-Eastern Mediterranean cities, PCM with a melting temperature of 26 °C affected energy savings by 56 %. In South-Eastern Mediterranean cities, PCM did not contribute to energy savings [36]. The effect of using two types of PCM in bricks according to the climate of Medina, Saudi Arabia was numerically investigated. Square hole bricks filled with PCM were used for the interior wall and compared with the case without PCM. The results show that the maximum heat through the wall occurs in the afternoon. In general, the use of PCM reduces the amount of heat passing through the wall [37].

Filling brick cavities with PCM close to the indoor environment provides high energy savings. The optimum fusion temperature of PCM varies from season to season in the range 18–26 °C. By adding PCM to the brick, the annual thermal load is reduced by 17.6 %, of which 13.2 % is due to latent heat utilization [38]. Even at maximum outdoor temperatures, the thermal performance of concrete bricks using PCM improves significantly [39]. It was emphasized that PCM-based bricks outperformed the reference brick. It was concluded that PCM capsules significantly affect the thermal behavior of equivalent bricks with PCM added [40]. It has been shown that 89 % energy savings can be achieved in volumes adjacent to walls with PCM in winter [41].

The thermal conductivity performance as well as the mechanical and compressive strength properties of PCM-filled bricks is an important topic to be investigated. To prepare high-density PCM-bricks, polyethylene and paraffin wax were added to the cement mortar to test the thermal effect on the wall as well as the mechanical strength of the bricks. As a result of the research conducted by Zhao, & Buildings, the average compressive and flexural strengths of PCM-bricks were found to be 5.11 MPa and 3.70 MPa, respectively. Since these ratios are low compared to normal bricks in terms of load carrying capacity, it is suggested that they can only be used in frame buildings [42]. In some studies, the brick was reinforced with various synthetic and organic materials [1], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]. It is seen that the addition of PCM reduces the mechanical strength of the bricks even though it reduces the heat flow transfer to the building interior. From this point of view, the necessity of optimization studies regarding the mechanical strength of bricks containing PCM emerges [48]. An optimization study was carried out on the amount of PCMs in the brick in order to maintain the strength of the brick with the minimum amount of PCMs. In this study, the location of PCMs in the brick gains importance. According to the test results obtained, it was claimed that if the cylindrically encapsulated PCMs are placed in the center of the brick, the brick retains its strength properties [49]. Similar to the brick study, it was determined that the strength values of PCM-added soil-fiber mixtures were around 1 MPa in all samples [50]. Some of the analyses on the strength of bricks, such as fracture and cracking, are in traditional methods that test them by throwing them on the ground [51]. However, in extreme loads such as earthquakes, the behavior of the brick can be very different.

Upon evaluating the literature, it is generally agreed that increasing the amount of PCM in the brick improves the structure’s thermal performance, though it should be optimized in terms of mechanical performance [52]. Although studies have examined the thermal performance of bricks, particularly those with added PCM, which is widely used in masonry wall construction, few of these studies have correlated thermal and mechanical performance. The studies conducted thus far have not addressed mass-produced bricks on the market. Therefore, this study investigated the mechanical properties of PCM-admixed commercially available bricks in detail. This study’s main objective is to evaluate the compressive strength of PCM-admixed bricks and optimize the PCM admixture in terms of strength and thermal performance.

2 Experimental metod

The experimental study examined the mechanical and thermal performance of hollow bricks filled with different types of insulation material. According to the experimental plan shown in Figure 1, the insulation materials were placed in the internal cavities of the bricks. Then, compressive strength and thermal conductivity tests were performed on each sample in both vertical and horizontal directions. The bricks used in the experiments are fired clay bricks with a porous, hollow structure obtained via standard production methods. Each brick measured 19 cm × 19 cm × 8.5 cm, and the pores were divided into three columns, labeled A, B, and C. Polyurethane foam, as well as PCM-1 and PCM-2, were filled into the brick cavities.

Brick polyurethane and PCM layout in the experimental design.

Table 1 expresses them as columns A, B, and C. Each letter represents a hollow pore on the brick from left to right. Two specimens were prepared for each experimental group to test the vertical and horizontal compressive strengths.

| Vertical hollow columns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||

| Brick (1–2) references | 1 | – | – | – |

| 2 | – | – | – | |

| Brick (2) | (2–1) | Poliyuretane | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 |

| (2-2) | Poliyuretane | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 | |

| Brick (3) | (3–1) | Poliyuretane | Poliyuretane | PCM-2 |

| (3–2) | Poliyuretane | Poliyuretane | PCM-2 | |

| Brick (4) | (4–1) | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 | Poliyuretane |

| (4–2) | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 | Poliyuretane | |

| Brick (5) | (5–1) | Poliyuretane | PCM-2 | Poliyuretane |

| (5–2) | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 | Poliyuretane | |

| Brick (6) | (6–1) | PCM-1 | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 |

| (6–2) | PCM-1 | Poliyuretane | PCM-1 | |

| Brick (7) | (7–1) | PCM-2 | Poliyuretane | PCM-2 |

| (7–2) | PCM-2 | Poliyuretane | PCM-2 | |

Tables 2 and 3 present the main physicochemical properties of the PCM-1, PCM-2, and polyurethane materials used in the study in a comparative manner. PCM-1, a product of Aldrich, is based on calcium chloride dihydrate (CaCl2–6H2O). It has a molecular weight of 219.08 g/mol and a recommended storage temperature of 2–8 °C. Its pH range is 5.0–7.0. It has a melting point of 29.7 °C, a relative density of 1.71 g/mL at 25 °C, and a water solubility of approximately 219.1 g/L at 20 °C. PCM-2 is a commercial phase-change material (Nextel 24D), and its exact chemical formula is not specified. Its melting point is 24 ± 2 °C, and its relative density is 0.9 g/mL. The average particle size ranges from 15 to 30 μm, and the enthalpy of fusion is ≥ 170 J/g. This table highlights important PCM parameters such as thermal storage capacity, density, and phase change temperature. It is important to evaluate the different performances of PCM-1 and PCM-2 in heat storage applications because they have different physical and thermal properties.

PCM’s general properties.

| Description | PCM-1 | PCM-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Brand | Aldrich | Nextek-24D |

| Formula | CACI2.6H2O | Commercial product |

| Molecular weight | 219,08 g/mol | – |

| Storage stability | Recommended storage temperature (2–8) °C | – |

| pH | 219.1 g/l at 5.0–7.0, 25 °C | – |

| Melting point | 29.7 °C | 24 ± 2 °C |

| Relative density | 1.71 g/ml, 25 °C | 0.9 g/ml |

| Solubility in water approx. | 219.1 g/l at 20 °C | – |

| Particle size (mean) | – | 15–30 μm |

| Heat of fusion | – | ≥170 J/g |

Polyureteane properties.

| Technical specifications eurofix polyurethane foam | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chemical structure | Polyurethane | |

| Curing mechanism | Moisture curing | |

| Density | 22 ± 3 kg/m3 | (ASTM D1622) |

| Shell Bonding time (1 cm) | 7 ± 3 dk. | (ASTM C1620) |

| Cutting time (lcm) | 30-45 dk. | (ASTM C1620) |

| Curing time | 24 saat | |

| Foum color | Light yellow | |

| Yield | 30–45 L | (ASTM C1536) |

| Expansion amount | % 200–250 | |

| Shrinkage amount | % 0 | |

| Combustion class | B3 | (DİN 4102) |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.036 W/m.k (at 20 °C) | (DİN 52,612) |

| Compressive strength | 0.03 MPa | (DİN 53,421) |

| Water absorption | Max. 1 % by volume | (DİN 53,428) |

| Temperature resistance | −40 °C to +80 °C | |

| Application temperature | −2 °C to +30 °C | |

| Can temperature | +5 °C to +30 °C | |

| The indicated values were obtained at 23 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 5 % humidity | ||

The polyurethane has physical and mechanical properties. Its density is 22 ± 3 kg/m3, and it has a light, porous structure. The shell binding time is 7 ± 3 min, the cuttable time is 30–45 min, and the full curing time is 24 h. These times are important for evaluating the hardening process and ease of application. The foam expanded 200–250 %, indicating a significant increase in volume compared to its initial application. Shrinkage is 0 %, meaning the foam does not shrink during curing. In terms of thermal and mechanical performance, the foam has a combustion class of B3 (according to DIN 4102), indicating low resistance to combustion. Thermal conductivity is 0.036 W/(m·K) at 20 °C, indicating good thermal insulation performance (see Table 3). Since the compressive strength is 0.03 MPa, the foam’s mechanical load-carrying capacity is low. With a maximum water absorption capacity of 1 %, the foam is moisture-resistant. Application and working conditions: The temperature resistance is between −40 °C and +80 °C, and the foam can maintain stability within a wide temperature range. The application temperature should be between −2 °C and +30 °C, and the tin temperature should be between +5 °C and +30 °C. The specified values were obtained in a standard test environment with a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C and humidity of 50 ± 5 %. These technical specifications demonstrate that Eurofix polyurethane foam is ideal for thermal insulation and gap filling applications. However, due to its B3 non-flammability classification, it may be inconvenient to use in places with a high risk of fire.

According to the experimental plan determined in the first stage, the brick pores were filled with polyurethane, as shown in Figure 2. Then, PCM-1 and PCM-2 were filled.

Polyurethane-filled bricks.

Polyurethane and PCMs can exhibit different performance characteristics in terms of energy absorption and load-carrying capacity. First, brick compression tests were performed on empty reference specimens in vertical and horizontal positions. Then, the polyurethane- and PCM-filled bricks were broken in the same order. Figure 3 shows fracture images from an experimental study in which a total of 14 bricks, along with reference specimens, were fractured. These experiments were conducted in accordance with EN 772–1.

Brick crushing tests.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Thermal behaviour

Air normally occupies the cavities in perforated bricks. Air is a good insulator and is also used as a filler in double-glazed windows. This study considered various filling materials to improve the thermal behavior of bricks. The materials were placed in the brick’s cavities in different combinations. Since the goal is to enhance the brick’s thermal properties, the study investigated how the brick would behave when placed in a wall between indoor and outdoor environments under summer and winter conditions. At this stage, the study was carried out numerically. Three materials (PCM-1, PCM-2, and polyurethane) and seven layouts (Figure 1) were considered as filling materials. Because heat transfer from the brick wall occurs over the depth of the brick, the layout’s orientation (horizontal or vertical) does not make a difference. The summer and winter performance of the bricks was compared with the unfilled reference brick using the results obtained from the numerical study.

3.2 Numerical simulation

3.2.1 Numerical model and description of the simulation method

The hollow brick was modeled in three dimensions with its actual dimensions in the SolidWorks program. Then, it was transferred to the FloEFD program [55]. Numerical analyses were performed using the commercial computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software FloEFD. This software uses a finite volume method with second-order accurate discretization schemes in its solver to ensure precise resolution of transient heat transfer phenomena. The energy equation for transient heat conduction without heat sources is as follows [56];

where ρ is density, c is specific heat capacity, T is temperature, t is time, λi is thermal conductivity. The phase change phenomenon was indirectly modeled. Phase change materials were integrated code by using temperature-dependent specific heat capacity (c) values to emulate phase change behavior [56].

where c l and c s are the specific heat capacities of the liquid and solid PCM, respectively, L f is the enthalpy of fusion/melting of the PCM, T m is the temperature of phase transition, T PCM is the temperature of the PCM and ΔT is a temperature difference of the phase transition. The data and properties entering Eqs. (1) and (2) for the PCMs are summarized in Table 4.

Thermo-physical properties of materials for numerical simulation.

| PCM-1 (CACI2.6H2O) | PCM-2 (Nextek24D) | BRICK | POLY-URETANE foam | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property | Symbol | Unit | Value | Source | Value | Source | Value | Source | Value |

| Specific heat capacity (liquid) | cl | J/kg·K | Value | [57] | 2,200 | [58] | – | – | |

| Specific heat capacity (solid) | cf | J/kg·K | 2,000 | [57] | 1,990 | [59] | 840 | [8], 55] | 1,450 |

| Simulated phase change temperature range | ΔT | K | 1,700 | [56] | 1 | [56] | – | – | |

| Latent heat of fusion | Lf | kJ/kg | 213 | [57] | 177 | [59] | – | – | |

| Phase change temperature (peak) | Tm | °C | 29.7 | [57] | 23 | [59] | – | – | |

| Density (liquid phase) | ρl | kg/m3 | 1,560 | [57] | 880 | [59] | – | – | |

| Density (solid phase) | ρs | kg/m3 | 1,710 | [57] | 950 | [59] | 1,600 | [8], 55] | 22 |

| Thermal conductivity (liquid) | λl | W/m·K | 0.56 | [57] | 0.267 | [59] | – | – | |

| Thermal conductivity (solid) | λs | W/m·K | 108 | [57] | 0.25 | [58] | 0,7 | [8], 55] | 0.036 |

The surface heat flux was computed using Fourier’s law:

Where λ is thermal conuctivity, ∇T is the temperature gradient across the solid domain. FloEFD automatically integrates this quantity over selected surfaces to obtain the total heat transfer rate [60], 61].

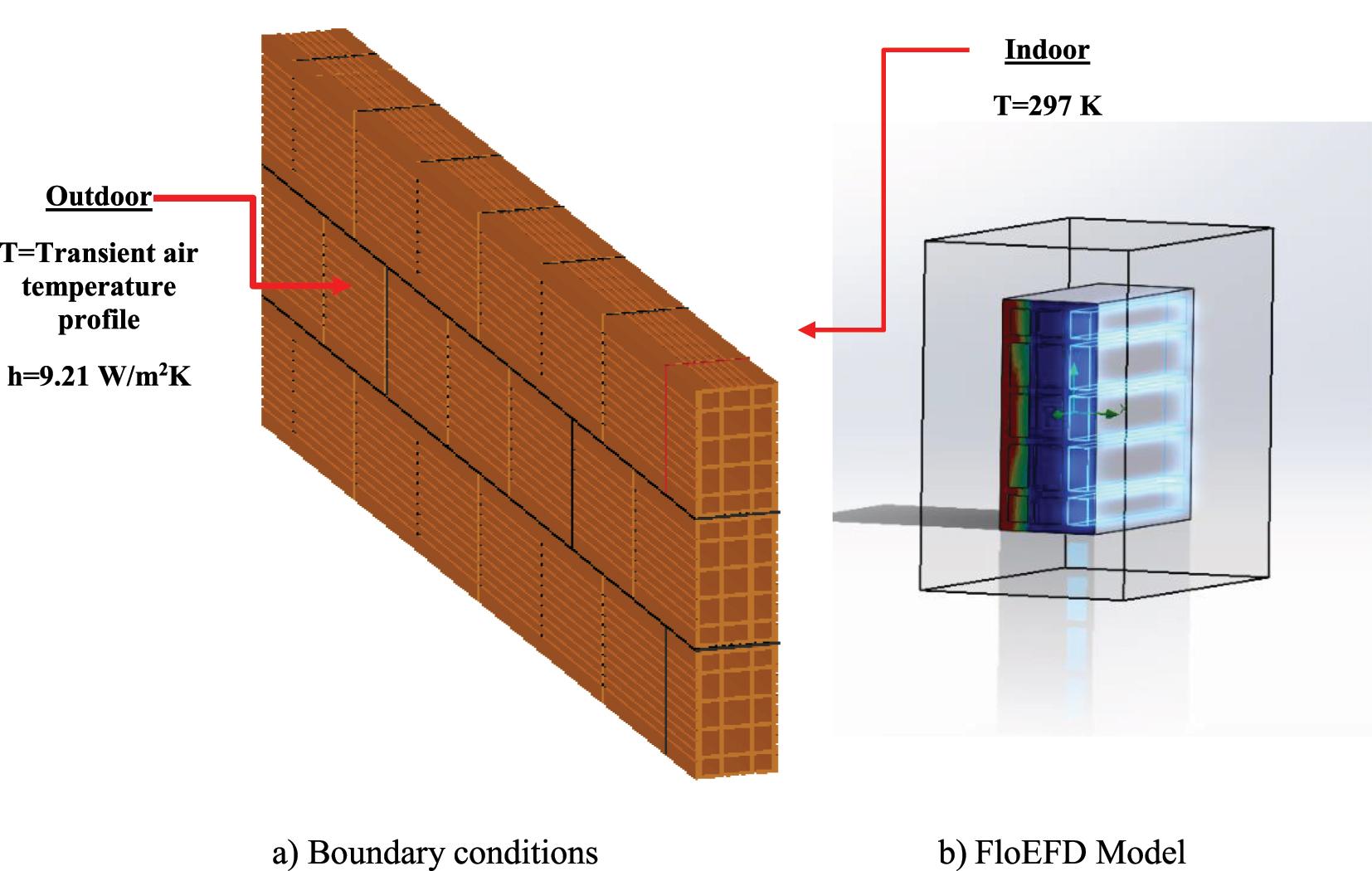

The numerical model is shown in Figure 4. One brick forming the wall was modeled. According to a study by Kon and Sandal, heat flow through the wall directly affects cooling and heating energy consumption, particularly by impacting indoor air temperature [54]. The simulations were performed under transient conditions for a total duration of 40 h (144,000 s). Real-time outdoor temperature data for Kayseri Province was incorporated as a time-dependent boundary condition, while the indoor temperature was held constant at 24 °C. The outdoor temperature profile used in the analysis is presented in Figure 6. The bricks were modeled such that the top and bottom surfaces were assumed to be adiabatic, which restricts heat transfer to conduction through the lateral surfaces (left and right) under the imposed temperature gradient. All of the bricks were geometrically symmetrical, except for bricks two and 3. Therefore, simulations were conducted for both possible orientations of indoor and outdoor surface assignments for those two asymmetric cases to ensure an accurate evaluation of thermal performance. Furthermore, perfect thermal contact was assumed between the PCM and the surrounding brick matrix. The convergence criterion for all residuals was set at 10−3.

Numerical model.

Figure 5 shows the change in outdoor temperatures over time for the summer (red) and winter (blue) seasons in Kayseri Province. In the summer, the initial temperature is around 290 K (17 °C), rising to 310 K (37 °C) during the day. Although it decreases later in the day, the general trend shows that the temperature remains high. In winter, the initial temperature is around 260 K (−13 °C). During the day, the temperature increases, reaching 270 K (−3 °C). It then declines again, rising at the end of the day. In summer, temperature variation is more widespread, rising significantly during the day. In winter, temperatures stay low and variation is limited. Temperature changes are shaped by daily solar radiation. In Kayseri, there are significant differences between low winter temperatures and high summer temperatures. This graph provides important data for understanding how building materials and insulation solutions respond to seasonal temperature fluctuations. PCM solutions, in particular, can provide energy efficiency to stabilize indoor temperatures.

Winter (measured) and summer (modeled) outdoor temperature for kayseri province.

![Figure 6:

Validation of the numerical code with qudama et al. [39].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0164/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0164_fig_006.jpg)

Validation of the numerical code with qudama et al. [39].

The convection heat transfer coefficient (h_w = 2.8 + 3 × 2.1378 = 9.21 W/(m2·K)) was calculated by substituting the average wind speed (u_w = 2.1378 m/s) for Kayseri into equation (4) [62]. This value was entered into the FloEFD program. The indoor convection boundary condition was entered with a value of 6 W/m2 K.

3.2.2 Validation of the code and mesh independency

The numerical method employed in this study is validated by the work of Qudama et al. [39], who examined the impact of PCM capsule geometry on thermal performance using four brick types (Brick-A to D) of size 23 × 12 × 7 cm. RT42 was used as the PCM. Boundary conditions included a constant indoor temperature of 28 °C, with heat transfer coefficients of 8.7 W/m2·°C (indoor) and 20 W/m2·°C (outdoor), while ambient temperature and solar radiation were time-dependent [39], 63]. Brick-C, as defined in Qudama et al. was numerically simulated in FloEFD under equivalent boundary conditions with same materials. The resulting inner temperature profiles exhibited acceptable correlation with experimental measurements, with deviation below 15 % (Figure 6) The observed consistency in both temperature amplitude and temporal trend supports the validity and predictive capability of the implemented numerical model.

To ensure mesh independence, the analysis was performed with different cell numbers and three sensitivity values found in the program. The number of meshes, the values obtained, and the percentage change in the results are summarized below. As can be seen, the change is very small. Mesh two was chosen as the most appropriate option in terms of time and accuracy, as shown in Table 5.

Mesh independency results.

| Mesh number | Number ofcells | External walltemperature value | % Variation | External wallheat flux value | % Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh-1 | 1,016 | 309,105,238,947,086 | – | −18,491,479,297,334 | – |

| Mesh-2 | 1,768 | 309,154,233,158,705 | 0.0159 | −18,0,402,426,083,247 | −2.44 |

| Mesh-3 | 1,992 | 309,158,035,751,841 | 0.0012 | −18,0,052,207,255,461 | 0.194 |

3.3 Numerical results

3.3.1 Temperature contours for summer and winter conditions

The images in Figure 8 show the results of a heat transfer analysis simulation using the finite element method (FEM). The color scales show the temperature distribution in Kelvin and provide information about heat flow through the analyzed structure. The color scale ranges from red to blue. Red regions represent higher temperatures, and blue regions represent lower temperatures. The images are labeled with names such as “B1, B2, B3…” and “B2-reverse, B3-reverse.” The analyses labeled “reversed” indicate a change in the inner and outer sides of the brick cases. Heat dissipation is influenced by material properties and geometric factors. Concentrating heat flow at certain points can help identify critical zones in terms of potential thermal stresses or efficiency. The temperature contours formed within the brick during heat transfer from outside to inside at noon, when the outdoor temperature is at its highest (51,600th second, 14:33rd hour, Figure 5), are shown for each brick in Figure 7 for both summer and winter. The temperature changes of the filled bricks are close to each other, ranging from 302 to 304 K. The temperature of the empty reference brick ranges from 296 to 298 K in the summer. In winter, temperature changes of the filled bricks vary close to each other in the range of (280–295) K; the temperature of the empty reference brick is in the range of (280–294) K.

Temperature contours for summer and under winter conditions for all brick combinations.

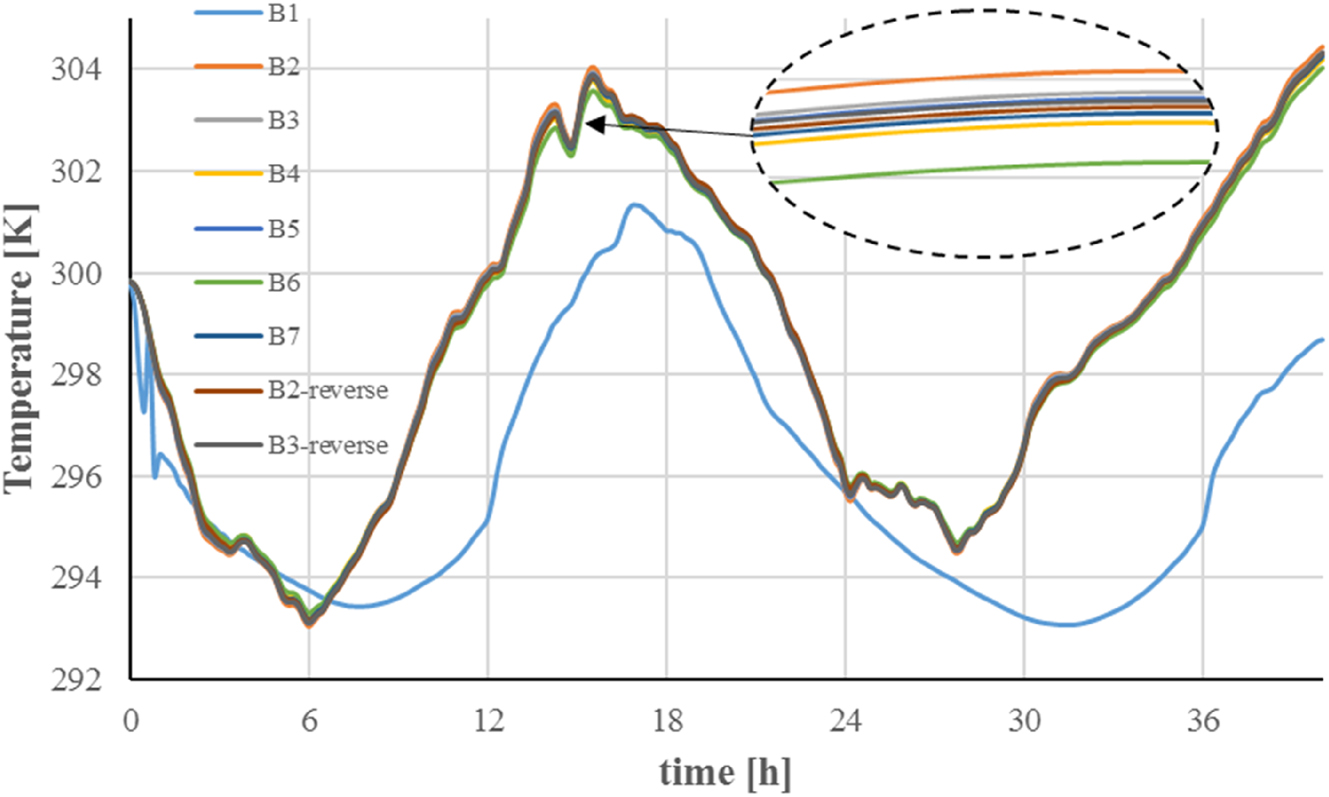

Time dependent variation of external wall surface temperatures.

3.3.2 Transient temperature and heat flux comparison for summer conditions

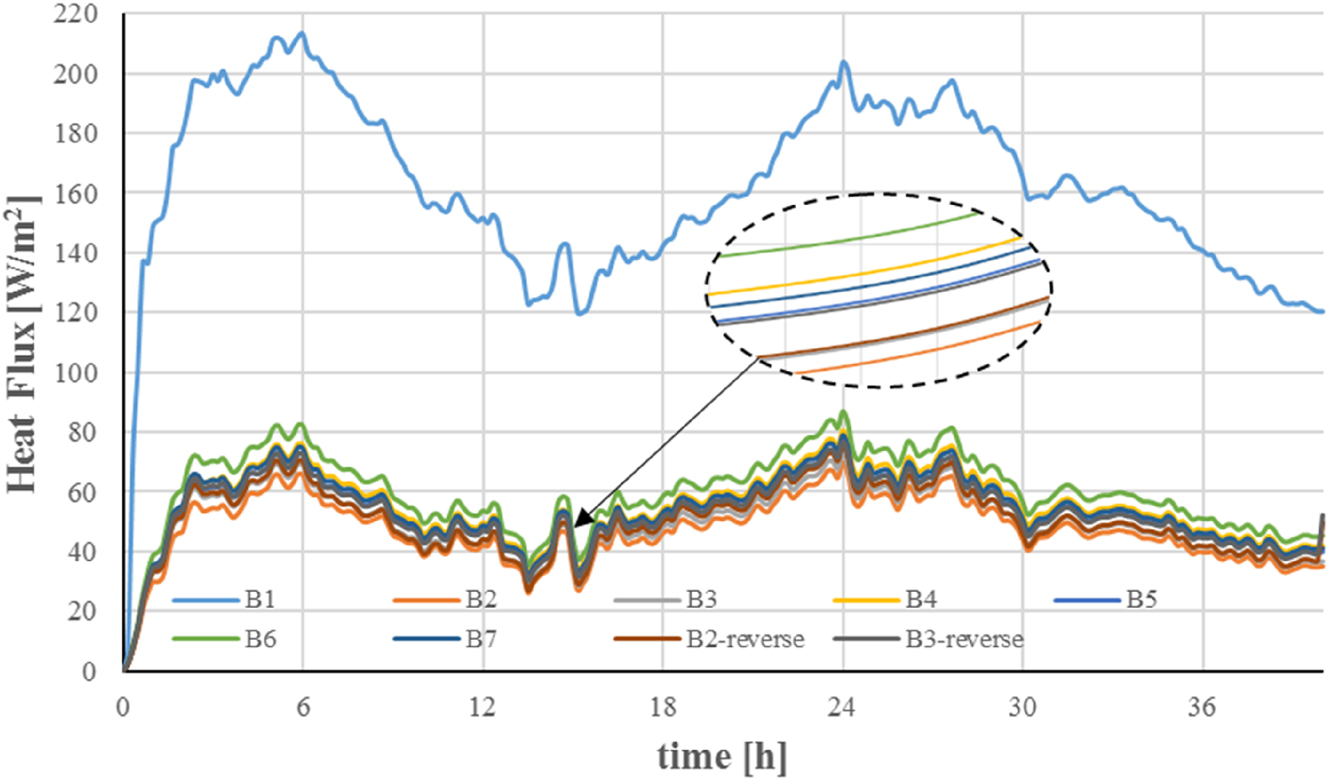

Figures 8 and 9 show the surface temperature and heat flux values on surfaces in contact with the external environment, respectively. Compared to the reference brick, the external surface temperatures of the filled bricks are higher. Between 12 and 20 h at nighttime, the amount of heat escaping from the outer wall is considerably lower in the filled bricks than in the blank reference brick. Note that a negative sign indicates heat transfer in the opposite direction. Similarly, at 26 and 35 h into the analysis, heat loss from the empty brick is higher. The hollow brick does not prevent the interior from heating up during the summer. However, there is less heat transfer from the filled bricks, and the day-night temperature fluctuation is smoother. This can be explained by the fact that filled bricks do not immediately react to the temperature difference between day and night like hollow bricks do and can retain their heat for a while. In other words, the energy storage feature of the filler material could be activated in the summer.

Time dependent variation of external wall surface heat flux.

3.3.3 Transient temperature and heat flux comparison for winter conditions

Figuress 10 and 11 show the surface temperature and heat flux values on surfaces in contact with the external environment, respectively. The external surface temperature of the reference brick is higher than that of the filled bricks. Similarly, more heat escaped from the filled bricks than from the empty brick. All filled bricks formed a barrier to heat loss. Additionally, the heat flux fluctuation is much smoother. There was no change in peak times. Figure 10 shows how external wall surface temperatures vary over time. The B1 curve has significantly higher temperature values than the others. This may indicate a different surface material, ambient conditions, or insulation. The other temperature curves (B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, and B7) are close together, suggesting similar thermal properties. In general, temperatures fluctuate during the day, decreasing at night and increasing during the day.

Time dependent variation of external wall surface temperatures.

Time dependent variation of external wall surface heat flux.

Figure 11 shows the time-varying heat flux (W/m2) at the exterior wall surface. The heat flux at point B1 is significantly higher than at the other measurement points. This suggests that this point is either exposed to more solar radiation or has lower thermal resistance. The other measurement points (B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, and B7) show lower, similar heat flux values, indicating balanced heat transfer. Heat flux varies throughout the day, particularly increasing during the day and decreasing at night.

3.3.4 Comparison of filled bricks

The graphs in Figure 12 illustrate how the heat flux of the external wall surface changes over time during the summer and winter seasons. In summer, the heat flux is positive, indicating heat transfer from outside to inside. According to Figure 12, the heat loss values of the filled bricks are very similar. Brick B2 provided the best results for both the summer and winter seasons. B6 provided the worst results for both seasons. Initially, the heat flux is minimal (∼25–30 W/m2), then it increases as time progresses (∼16 h), reaching around 50–55 W/m2. Although B2 produced the best results, there were small differences between B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, and B7, and the general trend was similar. The curve with the lowest heat flux (B6) is significantly higher than the others, suggesting that this material has lower thermal resistance or is exposed to more solar radiation. In winter, the heat flux is negative, indicating heat transfer from inside to outside. Initially at −30 W/m2, it increases over time, reaching −10 W/m2 around 16 h. Similar to the summer season, small differences are observed between the materials. The curve with the lowest heat flux (probably B6) is lower than the others, suggesting that this material may cause more heat loss in the winter. The B2 brick provided the best thermal performance results. Filling the holes closest to the external wall with a phase change material (PCM) with a melting temperature close to the maximum surface temperature reached, and filling the other cavities with an insulation material, produced very good results. On average, this brick saved 36 % more heat than the reference brick in winter and 43 % in summer. The B6 brick achieved the lowest energy savings at 32 % and 42 % for winter and summer, respectively. The obtained heat flux reduction was compared with values reported in the literature. Seasonal energy savings achieved through PCM integration range from 18.7 % to 97 % in summer and from 22.5 % to 44 % in winter. This highlights the PCM’s greater cooling potential while offering substantial thermal benefits during colder periods [33].

Time dependent variation of external wall surface heat flux filled bricks.

3.3.5 Effect of PCM type and placement on heat transfer

Figure 13 shows the heat flux values of the bricks filled with phase-change materials (PCMs). The brick has three columns of holes. These columns are named interior, exterior, and middle according to the boundary conditions. The red and blue lines in the graphs represent the bricks with PCM-1 and PCM-2, respectively. According to Figure 13, the lowest heat flux value is provided by B2, where PCM-1 is placed in the exterior holes of the brick, realizing heat transfer from outside to inside in the summer and from inside to outside in the winter. During the winter, the lowest heat flux (from inside to outside) is achieved with B2. The best result was obtained with B2 in all cases. This result shows that PCM-1 is more effective than PCM-2 and that applying PCM to the outer surface, which is most affected by outdoor conditions, is more effective [29]. The melting temperature of PCM-1 is 27.9 °C (301 K), which is very close to the wall surface temperature of 300–304 K reached during the daytime in the summer (Figure 8), and it gave the best result, confirming the literature [26]. Additionally, it was observed that placing the PCM layer on the inner wall did not provide an advantage over other placements in terms of total heat transfer [64]. Replacing the PCM in the middle of the brick is not as effective as placing it near the outer surface. However, PCM-1 produces better results than PCM-2 in this position.

Effect of PCM type and placement on the time-dependent change of external wall surface heat flux.

3.3.6 Compressive strength test results

Figure 14 shows the maximum fracture load distributions of the bricks broken for the strength test. The results are comparative for vertically and horizontally fractured specimens. The reference specimens are shown in red. In general, an increase in compressive strength was observed in both types of fractured bricks. The blue specimens are filled with polyurethane and FDM, as shown in the experimental setup. In the vertical position, compressive strength increased by up to 28 %, whereas in the horizontal position, it increased by up to 74 %, compared to reference specimens (B1). These results demonstrate that filling bricks with similar materials during production improves their fracture strength and prepares them for thermal insulation. The x-axis in Figure 14 is based on the plan in Table 1. Here, Ref is taken from the table as written: P = polyurethane and PCM is also taken from the table.

Compressive strength of brick in horizontal and vertical position.

4 Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of replacing the air-filled cavities in commercially available hollow bricks with PCMs and polyurethane on both mechanical and thermal performance. In terms of mechanical behavior, the addition of PCM caused an increase in the compressive strength of the bricks, while it decreased in some samples. However, configurations incorporating polyurethane showed potential for optimizing both thermal insulation and mechanical strength. The filled bricks mitigated the temperature fluctuations caused by the difference in day and night temperatures. This demonstrates that using this building material will provide more economical building temperature control.

B1 (the reference brick) exhibits different behavior than the others in terms of temperature and heat flux. The other bricks exhibit similar, albeit lower, temperature and heat flux values. Solar radiation, material properties, and outdoor weather conditions directly affect surface temperature and heat flux.

The B2 brick provided the best result in terms of thermal performance. Filling the holes closest to the exterior wall with a phase-change material (PCM) with a melting temperature close to the maximum surface temperature and filling the other cavities with insulation material produced excellent results. On average, this brick saved 36 % and 43 % more heat than the reference brick in the winter and summer seasons, respectively.

This is considerably higher than the vertical compressive strength of each specimen. There is an overall increasing trend with increasing specimen number. For example, it was 68 % in B1 and decreased to 58 % in B5, showing an increasing difference.

In the summer, heat flows from outside to inside, and in the winter, it flows from inside to outside. The heat flux varies over time and increases later in the day in both seasons. The type of material plays an important role in heat transfer. Some materials (e.g., B6) facilitate more heat transfer, while others provide more stable heat flow. During the winter months, materials with lower thermal conductivity are preferred to minimize heat loss.

This study presents an integrated experimental and numerical evaluation of the thermal conductivity and compressive strength of commercially available hollow bricks filled with pPCMs and polyurethane unlike previous research, which typically addresses thermal and mechanical performance separately. The novelty of the work lies in optimizing PCM placement within standard brick cavities to enhance thermal insulation while minimizing adverse effects on mechanical strength. To improve transparency and reproducibility, the methodology section has been expanded to include detailed descriptions of the materials used, their properties, the experimental setup (including both vertical and horizontal tests), and the FloEFD-based simulation model. Results indicate that PCM- and polyurethane-filled bricks significantly reduced indoor temperature fluctuations, enhancing thermal insulation by up to 43 % in summer and 36 % in winter compared to unfilled reference bricks. The B2–B3 configuration, where PCM-1 was placed near the external surface, exhibited the most effective thermal performance. Bricks filled with polyurethane and FDM showed increased compressive strength, up to 28 % vertically and 74 % horizontally, compared to reference specimens. This emonstrates that filling bricks with such materials improves their fracture strength and thermal insulation.

When evaluated from both aspects, it is evident that the subject studied affects compressive strength, thermal conductivity, and thus, heat transfer. Research using PCM with different phase change temperatures and lightweight materials with different thermal conductivities should be carried out to achieve optimum design conditions. This research could inspire new approaches and provide solutions to reduce CO2 emissions and combat global warming. Future research topics include investigating use in different buildings and climates, creating design guidelines, and conducting life cycle assessments and economic feasibility studies.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Zak, P, Ashour, T, Korjenic, A, Korjenic, S, Wu, W. The influence of natural reinforcement fibers, gypsum and cement on compressive strength of Earth bricks materials. Constr Build Mater 2016;106:179–88.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.031Suche in Google Scholar

2. Arslan, MA, Aktaş, M. İnşaat sektöründe kullanılan yalıtım malzemelerinin ısı ve ses yalıtımı açısından değerlendirilmesi. Politeknik Dergisi 2018;21:299–320.10.2339/politeknik.407257Suche in Google Scholar

3. Tanrıverdi, B. Comparison of heating and cooling degree days of states in 2nd degree day in TS 825. Master’s thesis, İstanbul Technical University 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Özel, M, Çakmak, FA. Farklı yönlendirmeli Bina Dış Duvarlarında faz Değiştiren Malzeme Kullanımının Isı Kazancına Etkisinin araştırılması. Fırat Üniversitesi Mühendislik Bilimleri Dergisi 2023;35:413–24.10.35234/fumbd.1210192Suche in Google Scholar

5. Zhang, Z, Wong, YC, Arulrajah, A, Horpibulsuk, S. A review of studies on bricks using alternative materials and approaches. Constr Build Mater 2018;188:1101–18.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.08.152Suche in Google Scholar

6. Zhang, L. Production of bricks from waste materials – a review. Constr Build Mater 2013;47:643–55.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.043Suche in Google Scholar

7. Monteiro, SN, Vieira, CMF. On the production of fired clay bricks from waste materials: a critical update. Constr Build Mater 2014;68:599–610.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.006Suche in Google Scholar

8. Kant, K, Shukla, A, Sharma, A. Heat transfer studies of building brick containing phase change materials. Sol Energy 2017;155:1233–42.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Wang, J, Yu, C, Pan, W. Life cycle energy of high-rise office buildings in Hong Kong. Energy Build 2018;167:152–64.10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.02.038Suche in Google Scholar

10. Ma, W, Kolb, T, Rüther, N, Meinlschmidt, P, Chen, H, Yan, L. Physical, mechanical, thermal and fire behaviour of recycled aggregate concrete block wall system with rice husk insulation. Energy Build 2024;320:114560.10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114560Suche in Google Scholar

11. Muthuraj, R, Lacoste, C, Lacroix, P, Bergeret, A. Sustainable thermal insulation biocomposites from rice husk, wheat husk, wood fibers and textile waste fibers: elaboration and performances evaluation. Ind Crop Prod 2019;135:238–45.10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.04.053Suche in Google Scholar

12. Crespo-López, L, Coletti, C, Arizzi, A, Cultrone, G. Effects of using tea waste as an additive in the production of solid bricks in terms of their porosity, thermal conductivity, strength and durability. Sustain Mater Technol 2024;39:e00859.10.1016/j.susmat.2024.e00859Suche in Google Scholar

13. Al-Yasiri, Q, Szabó, M. Thermal analysis of concrete bricks-embedded phase change material: a case study under hot weather conditions. Case Stud Constr Mater 2023;18:e02193.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02193Suche in Google Scholar

14. Kee, SY, Munusamy, Y, Ong, KS. Review of solar water heaters incorporating solid-liquid organic phase change materials as thermal storage. Appl Therm Eng 2018;131:455–71.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.12.032Suche in Google Scholar

15. Khan, MMA, Saidur, R, Al-Sulaiman, FA. A review for phase change materials (PCMs) in solar absorption refrigeration systems. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2017;76:105–37.10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.070Suche in Google Scholar

16. Diaconu, BM, Cruceru, M. Novel concept of composite phase change material wall system for year-round thermal energy savings. Energy Build 2010;42:1759–72.10.1016/j.enbuild.2010.05.012Suche in Google Scholar

17. Kim, T, Ahn, S, Leigh, S-B. Energy consumption analysis of a residential building with phase change materials under various cooling and heating conditions. Indoor Built Environ 2013;23:730–41.10.1177/1420326X13481990Suche in Google Scholar

18. Jeon, J, Lee, J-H, Seo, J, Jeong, S-G, Kim, S. Application of PCM thermal energy storage system to reduce building energy consumption. J Therm Anal Calorim 2012;111:279–88.10.1007/s10973-012-2291-9Suche in Google Scholar

19. Khadiran, T, Hussein, MZ, Zainal, Z, Rusli, R. Shape-stabilised n-octadecane/activated carbon nanocomposite phase change material for thermal energy storage. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2015;55:189–97.10.1016/j.jtice.2015.03.028Suche in Google Scholar

20. Jia, C, Geng, X, Liu, F, Gao, Y. Thermal behavior improvement of hollow sintered bricks integrated with both thermal insulation material (TIM) and phase-change material (PCM). Case Stud Therm Eng 2021;25.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Saylam Canim, D, Macka Kalfa, S. Faz değiştiren malzemelerin bina kabuğunda kullanımı. DÜMF Mühendislik Dergisi 2020;12:355–71.10.24012/dumf.779147Suche in Google Scholar

22. Duraković, B. Passive solar heating/cooling strategies. In PCM-Based Building Envelope Systems: Innovative Energy Solutions for Passive Design (pp. 39-62). Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020:39–62 pp.10.1007/978-3-030-38335-0_3Suche in Google Scholar

23. Mahdaoui, M, Hamdaoui, S, Ait Msaad, A, Kousksou, T, El Rhafiki, T, Jamil, A, et al.. Building bricks with phase change material (PCM): thermal performances. Constr Build Mater 2021;269.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Lingfan, S, Lin, G, Hongbo, C. Numerical simulation of composite PCM integration in prefabricated houses: sustainable and improved energy design. J Energy Storage 2024;91:111987.10.1016/j.est.2024.111987Suche in Google Scholar

25. Abbas, HM, Jalil, JM, Ahmed, ST. Experimental and numerical investigation of PCM capsules as insulation materials inserted into a hollow brick wall. Energy Build 2021;246:111127.10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111127Suche in Google Scholar

26. Abbas, HM, Jalil, JM, Ahmed, ST. Numerical investigation of using PCM with and without nano addition as insulation material in a hollow brick wall. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing LLC, 2022. p. 080018. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0066822.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Abdulhussein, MA, Hashem, AL. Experimental study of the thermal behavior of perforated bricks wall integrated with PCM. International Journal of Heat & Technology 2021;39.10.30772/qjes.v14i3.775Suche in Google Scholar

28. Thattoth, T, Anfas, M, Daniel, J. Heat transfer analysis of building brick filled with microencapsulated phase change material. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. AIP Publishing LLC, 2020. p. 030002. 9–10 August 2019 Mangaluru, India, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0066822.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Bondareva, NS, Sheikholeslami, M, Sheremet, MA. The influence of external temperature and convective heat exchange with an environment on heat transfer inside phase change material embedded brick. J Energy Storage 2021;33:102087.10.1016/j.est.2020.102087Suche in Google Scholar

30. Gao, Y, He, F, Meng, X, Wang, Z, Zhang, M, Yu, H, et al.. Thermal behavior analysis of hollow bricks filled with phase-change material (PCM). J Build Eng 2020;31:101447.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101447Suche in Google Scholar

31. Tıkız, İ, Pehlivan, H, Mermer, M. Bi̇na ısı yalıtım sistemlerinin incelenmesi ve optimizasyonu. Ejovoc (Electronic Journal of Vocational Colleges) 2018;8:106–35.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Khoukhi, M, Hassan, A, Al, SS, Abdelbaqi, S. A dynamic thermal response on thermal conductivity at different temperature and moisture levels of EPS insulation. Case Stud Therm Eng 2019;14.10.1016/j.csite.2019.100481Suche in Google Scholar

33. Ruiz-Marín, N. Selection and integration strategies of PCMs in traditional bricks for thermal comfort and energy efficiency: a comprehensive review. Energy Build 2025;337:115663.10.1016/j.enbuild.2025.115663Suche in Google Scholar

34. Rashid, FL, Dhaidan, NS, Al-Obaidi, M, Mohammed, HI, Mahdi, AJ, Ameen, A, et al.. Latest progress in utilizing phase change materials in bricks for energy storage and discharge in residential structures. Energy Build 2025;330:115327.10.1016/j.enbuild.2025.115327Suche in Google Scholar

35. Sudhakar, K, Winderl, M, Priya, SS. Net-zero building designs in hot and humid climates: a state-of-art. Case Stud Therm Eng 2019;13.10.1016/j.csite.2019.100400Suche in Google Scholar

36. Hamidi, Y, Aketouane, Z, Malha, M, Bruneau, D, Bah, A, Goiffon, R. Integrating PCM into hollow brick walls: toward energy conservation in Mediterranean regions. Energy Build 2021;248:111214.10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111214Suche in Google Scholar

37. Saeed, T. Influence of the number of holes and two types of PCM in brick on the heat flux passing through the wall of a building on a sunny day in Medina, Saudi Arabia. J Build Eng 2022;50:104215.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104215Suche in Google Scholar

38. Tunçbilek, E, Arıcı, M, Bouadila, S, Wonorahardjo, S. Seasonal and annual performance analysis of PCM-integrated building brick under the climatic conditions of marmara region. J Therm Anal Calorim 2020;141:613–24.10.1007/s10973-020-09320-8Suche in Google Scholar

39. Al-Yasiri, Q, Szabó, M. Effect of encapsulation area on the thermal performance of PCM incorporated concrete bricks: a case study under Iraq summer conditions. Case Stud Constr Mater 2021;15:e00686.10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00686Suche in Google Scholar

40. Al-Yasiri, Q, Szabó, M. Thermal performance of concrete bricks based phase change material encapsulated by various aluminium containers: an experimental study under Iraqi hot climate conditions. J Energy Storage 2021;40:102710.10.1016/j.est.2021.102710Suche in Google Scholar

41. Zhang, G, Xiao, N, Wang, B, Razaqpur, AG. Thermal performance of a novel building wall incorporating a dynamic phase change material layer for efficient utilization of passive solar energy. Constr Build Mater 2022;317:126017.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.126017Suche in Google Scholar

42. Wang, X, Yu, H, Li, L, Zhao, MJE, Buildings. Experimental assessment on a kind of composite wall incorporated with shape-stabilized phase change materials. (SSPCMs) 2016;128:567–74.10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.07.031Suche in Google Scholar

43. Bui, Q-B, Morel, J-C, Hans, S, Meunier, N. Compression behaviour of non-industrial materials in civil engineering by three scale experiments: the case of rammed Earth. Mater struct 2009;42:1101–16.10.1617/s11527-008-9446-ySuche in Google Scholar

44. Atzeni, C, Pia, G, Sanna, U, Spanu, N. Surface wear resistance of chemically or thermally stabilized earth-based materials. Mater Struct 2008;41:751–8.10.1617/s11527-007-9278-1Suche in Google Scholar

45. Hossain, KMA, Lachemi, M, Easa, S. Stabilized soils for construction applications incorporating natural resources of Papua New Guinea. Resour Conserv Recycl 2007;51:711–31.10.1016/j.resconrec.2006.12.003Suche in Google Scholar

46. Bahar, R, Benazzoug, M, Kenai, S. Performance of compacted cement-stabilised soil. Cement Concr Compos 2004;26:811–20.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

47. Ngowi, AB. Improving the traditional Earth construction: a case study of Botswana. Constr Build Mater 1997;11:1–7.10.1016/S0950-0618(97)00006-8Suche in Google Scholar

48. Kant, K, Shukla, A, Sharma, AJSE. Heat transfer studies of building brick containing phase change materials. Solar Energy 2017;155:1233–42.10.1016/j.solener.2017.07.072Suche in Google Scholar

49. Alawadhi, EM. Thermal analysis of a building brick containing phase change material. Ener Build 2008;40:351–7.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Alassaad, F, Touati, K, Levacher, D, Njjobe, S. Impact of phase change materials on lightened earth hygroscopic, thermal and mechanical properties. J Build Eng 2021;41:102417.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102417Suche in Google Scholar

51. Li, J, Cao, W, Chen, G. The heat transfer coefficient of new construction–Brick masonry with fly ash blocks. Energy 2015;86:240–6.10.1016/j.energy.2015.04.028Suche in Google Scholar

52. Mahdaoui, M, Hamdaoui, S, Msaad, AA, Kousksou, T, El Rhafiki, T, Jamil, A, et al.. Building bricks with phase change material (PCM): thermal performances. Constr Build Mater 2021;269:121315.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121315Suche in Google Scholar

53. Alawadhi, EM. Thermal analysis of a building brick containing phase change material. Energy Build 2008;40:351–7.10.1016/j.enbuild.2007.03.001Suche in Google Scholar

54. Kon, O, Sandal, K. Binaların dış duvarlarının yüzey özelliklerine bağlı enerji tüketim analizleri ve sıcaklık sönüm faktörü. J Innov Civil Eng Technol 2023;5:49–69.10.60093/jiciviltech.1381812Suche in Google Scholar

55. Siemens. https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/simcenter/products/2025.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Jurkowski, A, Klimanek, A, Sładek, S. Numerical and experimental study of thermal stabilization system for satellite electronics with integrated phase-change capacitor. Appl Therm Eng 2025;258:124645.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.124645Suche in Google Scholar

57. Hasan, A, McCormack, SJ, Huang, MJ, Norton, B. Characterization of phase change materials for thermal control of photovoltaics using differential scanning calorimetry and temperature history method. Energy Convers Manag 2014;81:322–9.10.1016/j.enconman.2014.02.042Suche in Google Scholar

58. Alassaad, F. Stockage d’énergie thermique dans des enveloppes hygroscopiques à base de matériaux biosourcés. PhD Thesis. Normandie Université 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

59. Erkizia, E, Strunz, C, Dauvergne, JL, Goracci, G, Peralta, I, Serrano, A, et al.. Study of paraffinic and biobased microencapsulated PCMs with reduced graphene oxide as thermal energy storage elements in cement-based materials for building applications. J Energy Storage 2024;84:110675.10.1016/j.est.2024.110675Suche in Google Scholar

60. Incropera, FP, DeWitt, DP, Bergman, TL, Lavine, AS. Fundamentals of heat and mass transfer. New York: Wiley; 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Busines, Siemens. FloEFD technical reference guide, https://www.smart-fem.de/media/floefd/TechnicalReferenceV17.pdf. Mentor Graphics Corporation 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

62. Watmuff, JH, Charters, WWS, Proctor, D. Solar and wind induced external coefficients-solar collectors. Cooperation Mediterraneenne pour l’Energie Solaire 1977:56.Suche in Google Scholar

63. Salman, R, Aljabair, S, Jalil, JM. Enhancing thermal performance and energy efficiency in concrete bricks with phase change materials: a numerical study. J Energy Storage 2025;125:116937.10.1016/j.est.2025.116937Suche in Google Scholar

64. Jia, C, Geng, X, Liu, F, Gao, Y. Thermal behavior improvement of hollow sintered bricks integrated with both thermal insulation material (TIM) and phase-change material (PCM). Case Stud Therm Eng 2021;25:100938.10.1016/j.csite.2021.100938Suche in Google Scholar

© 2026 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- A green and sustainable biocomposite materials: environmentally robust, high performance, low-cost materials for helicopter lighter structures

- Microstructural and UCS behavior of clay soils stabilized with hybrid nano-enhanced additives

- Optimization of microstructure and mechanical properties of microwave-sintered V/Ta/Re-doped tungsten heavy alloys

- Experimental and numerical study on the axial compression behavior of circular concrete columns confined by BFRP spirals and ties

- Effect of A-site calcium substitution on the energy storage and dielectric properties of ferroelectric barium titanate system

- Comparative analysis of aggregate gradation variation in porous asphalt mixtures under different compaction methods1

- Thermal and mechanical properties of bricks with integrated phase change and thermal insulation materials

- Nonlinear molecular weight dependency in polystyrene and its nanocomposites: deciphering anomalous gas permeation selectivity in water vapor-oxygen-hydrogen barrier systems

- ZnO nanophotocatalytic solution with antimicrobial potential toward drug-resistant microorganisms and effective decomposition of natural organic matter under UV light

- Review Articles

- Granite powder in concrete: a review on durability and microstructural properties

- Properties and applications of warm mix asphalt in the road construction industry: a comprehensive review and insights toward facilitating large-scale adoption

- Artificial Intelligence in the synthesis and application of advanced dental biomaterials: a narrative review of probabilities and challenges

- Recycled tire rubber as a fine aggregate replacement in sustainable concrete: a comprehensive review

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- A green and sustainable biocomposite materials: environmentally robust, high performance, low-cost materials for helicopter lighter structures

- Microstructural and UCS behavior of clay soils stabilized with hybrid nano-enhanced additives

- Optimization of microstructure and mechanical properties of microwave-sintered V/Ta/Re-doped tungsten heavy alloys

- Experimental and numerical study on the axial compression behavior of circular concrete columns confined by BFRP spirals and ties

- Effect of A-site calcium substitution on the energy storage and dielectric properties of ferroelectric barium titanate system

- Comparative analysis of aggregate gradation variation in porous asphalt mixtures under different compaction methods1

- Thermal and mechanical properties of bricks with integrated phase change and thermal insulation materials

- Nonlinear molecular weight dependency in polystyrene and its nanocomposites: deciphering anomalous gas permeation selectivity in water vapor-oxygen-hydrogen barrier systems

- ZnO nanophotocatalytic solution with antimicrobial potential toward drug-resistant microorganisms and effective decomposition of natural organic matter under UV light

- Review Articles

- Granite powder in concrete: a review on durability and microstructural properties

- Properties and applications of warm mix asphalt in the road construction industry: a comprehensive review and insights toward facilitating large-scale adoption

- Artificial Intelligence in the synthesis and application of advanced dental biomaterials: a narrative review of probabilities and challenges

- Recycled tire rubber as a fine aggregate replacement in sustainable concrete: a comprehensive review