Abstract

Crystalline rock is considered a potential host rock for a deep geological repository (DGR) for storing nuclear waste. Biotite is a common accessory mineral found in crystalline rocks such as granite and tonalite that plays an important role in the absorption of selenium (Se). In particular, the radioisotope Se-79 is widely present in spent nuclear fuel, and it is crucial for evaluating the suitability of a DGR for storing nuclear waste. In the anticipated reducing conditions of a DGR, the prevalent oxidation state would be Se (-II). However, the low solubility of Se under reducing conditions means that traditional spectrometry methods are not effective at studying the sorption mechanisms of Se (-II). Therefore, this study investigated the sorption mechanisms of Se (-II) on biotite under reducing conditions by using density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the inner-sphere complex and outer-sphere complex reactions. Both complexes were found to contribute to sorption of Se (-II) on biotite with the outer-sphere complexes being the primary sorption mechanism under the naturally neutral groundwater conditions. The results of the DFT calculations were consistent with the sorption experimental data and the results of the surface complexation modeling, which further confirmed the significance of the inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexes to the sorption of Se (-II) on biotite under a wider range of pH conditions.

1 Introduction

Deep Geological Repositories (DGRs) have become a globally accepted method for the long-term management of nuclear waste, and many countries have integrated DGRs into their nuclear waste management programs such as Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, and Canada. DGRs are constructed in suitable rock formations to ensure the safe containment and isolation of spent nuclear fuel. Finland and Sweden have selected their DGR sites in crystalline rock; Japan and Canada are considering crystalline rocks such as granite as potential host rocks for DGRs. 1 , 2 Multiple studies have supported granite as a suitable host rock for DGRs. 3 , 4 , 5

Selenium-79 has been identified as a factor of interest in safety assessments of potential DGR sites because of its long half-life (2.95 × 105–3.27 × 105 years) 6 , 7 and presence in spent nuclear fuel. 8 , 9 , 10 Selenium (Se) has high mobility in groundwater and a complex redox chemistry, so its sorption behavior under the anticipated reducing conditions of DGRs needs to be studied. 11 , 12 , 13 Biotite is a prevalent accessory mineral in granite, tonalite and other types of bedrock 14 , 15 that has demonstrated a sorption capacity for Se(IV) and Se(VI). 12 , 16 , 17 Lanin et al. 17 and Rabung et al. 18 established molecular structures of biotite, indicating the sorption of Se species is primarily through a surface complexation mechanism involving two types of surface hydroxyl groups: in strong sorption sites (≡SSOH) and in weak sorption sites (≡SWOH). 12 , 19 , 20

Under reducing conditions, Se predominantly exists in the oxidation state of Se (-II). 21 , 22 However, previous studies have primarily focused on the sorption of Se(IV) and Se(VI) and their derivatives under oxidizing conditions. 12 , 13 , 23 , 24 , 25 Research on the sorption mechanisms of Se (-II) is limited, with few studies addressing this topic. Iida et al. 22 investigated the sorption of Se (-II) on granodiorite in 0.05 and 0.5 mol/L (M) NaCl solutions. Kim et al. 26 studied the sorption of Se (-II) on magnetite in a 0.02 mol/L NaClO4 solution. Masschelevn et al. 27 investigated the influence of the oxidation-reduction potential of sediments on the transformation of Se. This research team 14 previously conducted batch sorption experiments and surface complexation modeling to investigate the sorption of Se (-II) on granite in Ca–Na–Cl solutions with an ionic strength range of 0.05–1.0 mol/kgw (moles of solute per kilogram of water). The results of this team’s previous study indicated that Se (-II) likely participates in outer-sphere sorption on biotite under reducing conditions. 14

Spectroscopic techniques are commonly used to study the sorption mechanisms of element on mineral surfaces. However, due to the low solubility of Se (-II) under reducing conditions, the concentration of Se (-II) sorbed on biotite is typically too low for ATR-FTIR and XPS analysis, making direct experimental characterization challenging. 14 , 21 , 23 , 28 Although XANES can detect Se (-II) at low concentrations, its ability to analyze complex systems with multiple sorption sites is limited. 24 , 29 Thus, spectroscopic techniques are of limited use when investigating the sorption mechanisms of Se (-II) on biotite under reducing conditions at the molecular level.

Density function theory (DFT) is a calculation method that is extensively used to investigate the electronic structures and energies of molecules on solid surfaces. DFT was previously used to study the sorption mechanism of U(VI) in the form of UO22+ in the interlayer region of calcium silicate hydrate phases 30 and the sorption of U(VI) on graphene oxide under aqueous conditions at varying pH levels. 31 DFT has also been used to investigate the sorption of Eu(III) on α-uranophane. 32 Xing et al. 33 used DFT to study the sorption of Se and SeO2 on the CaO (0 0 1) surface. Heberling et al. 34 used DFT to study the sorption of Se(IV) on calcite CaCO3. Puhakka et al. 25 applied DFT to study the sorption of Se(IV) and Se(VI) on Mg-rich biotite and calcite surfaces. 25 In this study, we used DFT to explore molecular-level mechanisms behind Se (-II) sorption on biotite.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

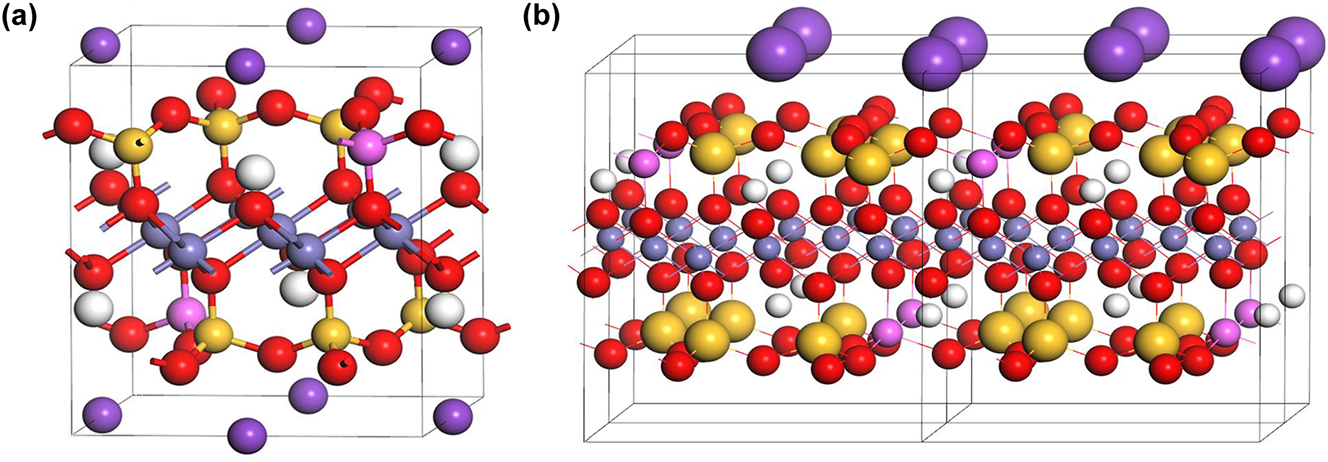

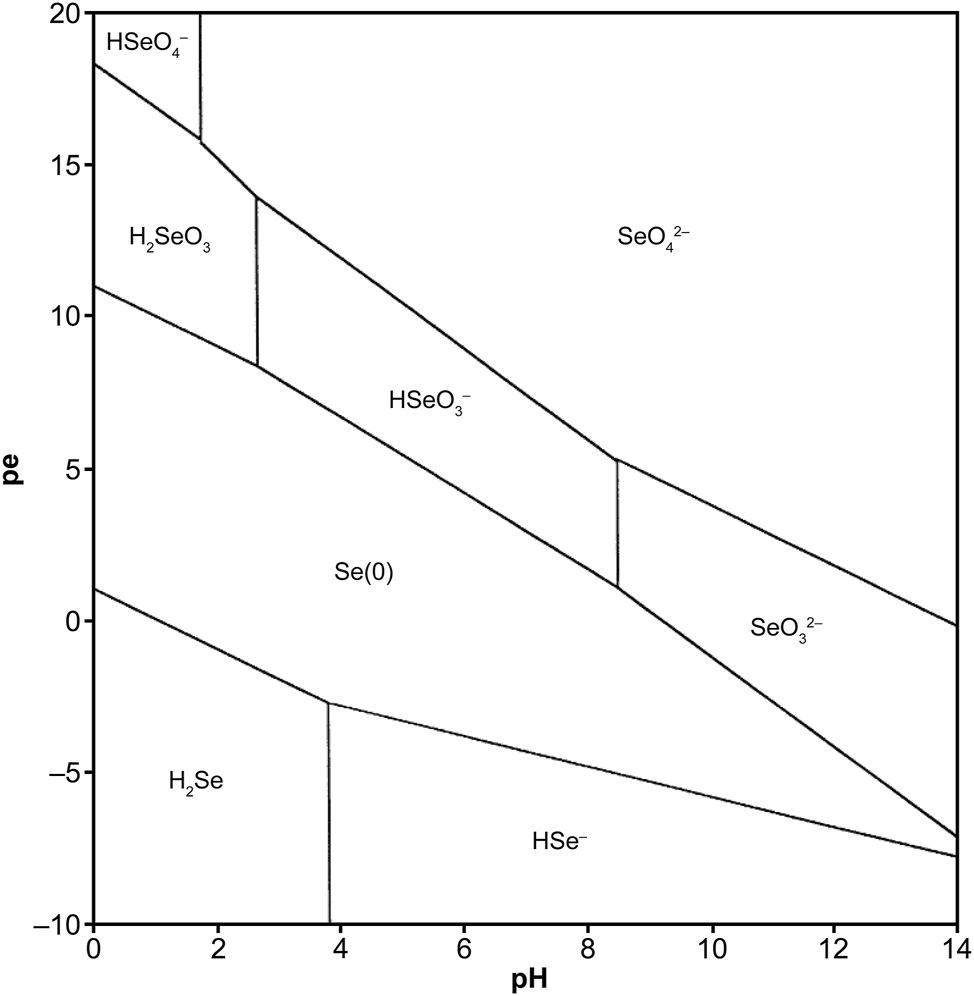

Biotite is a common phyllosilicate mineral in the mica family, with the approximate formula of K(Mg, Fe)3AlSi3O10(OH,F)2. Various of biotite can be found with different Mg and Fe content. Biotite has a prismatic and layered structure, with negatively charged layers mainly connected by potassium ions. 14 , 25 Previous studies have concluded that the sorption of Se (-II) on biotite can be primarily attributed to Fe and Al sites as well as associated –OH sorption sites in biotite. 21 , 22 Annite is the iron-end member of biotite with the general chemical formula of KFe3AlSi3O10(OH, F)2 where Mg is completely replaced by Fe (Figure 1a and b). Previous studies have mainly used annite as a representative biotite variant for easier modeling. 18 Based on the pe–pH predominance diagram of Se aqueous species in pure water (Figure 2) and the research of Iida et al., 21 , 22 , 35 the major species of Se (-II) under reducing conditions is believed to be the hydrogen selenide ion (HSe−).

Biotite structure models: (a) Crystal structure and (b) layered structure (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray).

Pe–pH predominance diagram of Se aqueous species in pure water at a temperature of 25 °C, pressure of 1 bar and dissolved Se concentration of 10−6 mol/L. 35

2.2 Density functional theory

DFT is a computational mechanical simulation method that simplifies multielectron interactions using the Kohn-Sham equations. Electron density is iteratively optimized to determine the system’s ground-state electronic configuration. 18 , 36 In this study, DFT calculations were performed by using the software CASTEP, which was integrated into the 2023 version of Materials Studio. CASTEP is a first-principles quantum mechanics-based simulation software that models material properties using quantum mechanical description of electron and nucleus interactions. 37 To handle electron wave functions, CASTEP uses the plane wave pseudopotential method, which is a highly effective technique for simulating electron behavior in solid materials.

The generalized gradient approximation Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE) functional was employed as the exchange–correlation functional. An on-the-fly generated ultrasoft pseudopotential (optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt) was chosen for its computational efficiency and accuracy. The following potentials were used Al_2017R2.otfg for Al, C_2017R2.otfg for C, Ca_2017R2.otfg for Ca, H_2017R2.otfg for H, K_2017R2.otfg for K, Mg_2017R2.otfg for Mg, O_2017R2.otfg for O, and Se_2017R2.otfg for Se. 37 The kinetic cutoff energy plane wave expansion of the wave function was set to 310 eV for biotite models to guarantee the high quality of all atoms.

To investigate the sorption of Se (-II) on biotite under reducing conditions, relevant three-dimensional atomic models were created, and several potential sorption configurations were constructed. Subsequently, DFT was used to calculate the interaction energies between electrons and between electrons and atomic nuclei, along with other quantum mechanical effects to determine the energetically stable structures of biotite and Se (-II) complexes. Finally, the sorption mechanism was elucidated by analyzing the steady-state energy changes derived from the DFT calculations.

A preliminary three-dimensional atomic model of biotite was developed to consider all elements specified in its chemical formula KFe3AlSi3O10(OH)2. Based on this initial model, representations of the prismatic (1 1 0) edge surfaces and layered (0 0 1) basal surfaces characteristic of biotite’s structure were developed to incorporate Fe–OH and Al–OH sorption sites. These models were geometrically optimized by using DFT to converge upon the atomic structure with the lowest energy state (i.e., stable state). These surface models were then geometrically optimized again by using DFT to establish various adsorbate complex models.

After the structural stable reactants and products were established, DFT was utilized to calculate their respective total enthalpy values. The enthalpy values were then used to calculate the sorption energy:

where Esorption is the sorption energy, Esystem is the enthalpy of the system including biotite and HSe−, Eabsorbent is the enthalpy of the slab supercell structure, and Eadsorbate is the enthalpy of the adsorbate in the vacuum.

2.3 Simulation of reducing condition

Under reducing conditions, Se predominantly exists in the -II oxidation state. Therefore, it is important to ensure that Se consistently maintains the oxidation state of -II throughout the DFT calculations in this study. When constructing the sorption site model for the DFT calculation, this study explicitly considered the influence of reducing conditions on the Fe and Al sorption sites, while the influence of oxidizing conditions on the Fe and Al sorption sites was excluded. During the model development and geometry optimization, free oxygen atoms potentially present on the biotite surface were systematically excluded to ensure the accurate simulation by DFT under reducing conditions.

2.4 Optimization of the biotite structure

The initial stable structure of biotite was determined by optimizing its unit cell structure which laid the groundwork for subsequent computational modeling and provided necessary data for calculating the bond dissociation free energy. This study followed the approach of previous studies and used annite as a representative model. 18 Biotite is characterized by a prismatic and layered structure with negatively charged layers that are primarily connected by potassium ions and a Si–Al ratio of 3:1. 18 The optimized lattice parameters of the biotite unit cell are the lengths a = 530.4 pm, b = 922.88 pm, c = 1,012.86 pm, and angles α = 90°, β = 100.173°, and γ = 90°.

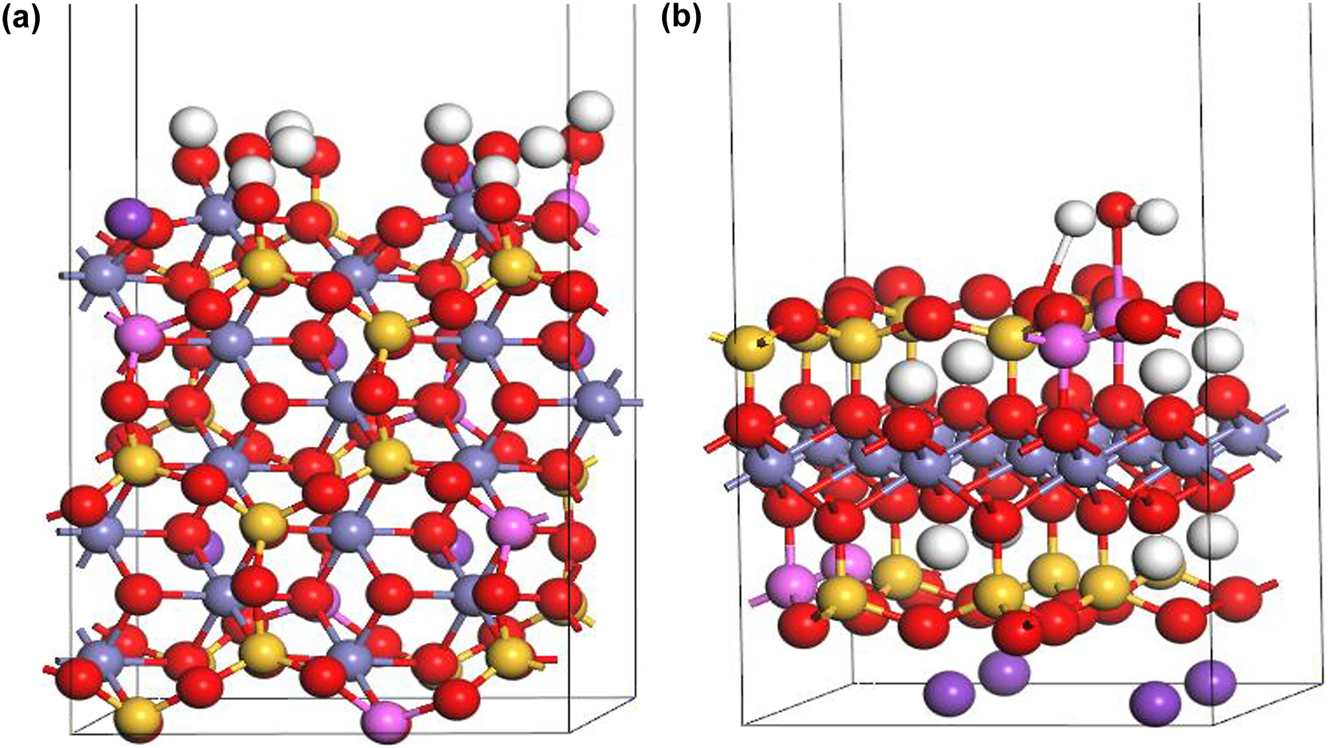

The optimized crystal structure of biotite was used to generate typical optimized surface structures. This research focused on the basal and peripheral surfaces to capture the characteristics of biotite. DFT was used to obtain the sorption of Se (-II) on the biotite surfaces, including the (1 1 0) edge surface terminated by the crystal structure and the (0 0 1) basal surface terminated by potassium ions.

The biotite (1 1 0) surface model (Figure 3a) had an area of 1.16 nm2 (1,088.87 × 1,066.45 pm2). The total thickness of the surface model was 2.33 nm, and each layer had a thickness of about 0.9 nm. The layers were in a hexahedral configuration, allowed to relax during the optimization of the surface structure. The surface was hydrated, and the Fe–O− and Al–O− groups were terminated with H+ to stabilize the surface structures. The void layer that isolated the surface from the bottom face of another periodic unit cell had a thickness of 1 nm. To accommodate more acidic conditions in the computational models, Fe–OH2 and Al–OH2 were employed as variants for Fe–OH and Al–OH sorption sites. This adjustment involved adding an additional hydrogen atom to the existing model and reoptimizing it to reflect the potential chemical behavior in an acidic environment.

Surface models of biotite: (a) (1 1 0) and (b) (0 0 1) (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink).

The biotite (0 0 1) surface model (Figure 3b) had an area of 1.16 nm2 (1,063.8712 × 922.5836 pm2), The total thickness was 2.10 nm. Each layer had a thickness of about 0.67 nm, and the layers were allowed to relax during the optimization of the surface structure. The surface was hydrated. The void layer that isolated the surface from the face of another periodic unit cell had a thickness of 1.25 nm. To accommodate more acidic conditions in the computational models, Al–OH2 was employed as a variant for Al–OH sorption sites.

3 Results

DFT was used to geometrically optimize the three-dimensional atomic models of the reactants and products and obtain their most stable structures. The enthalpy values of the optimized models were calculated. Finally, the enthalpy values were used to calculate the sorption energy.

3.1 Sorption of Se (-II) on the (1 1 0) surface

Various possible scenarios were studied to analyze the likelihood of inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexes binding to two different sorption sites and to consider the impact of the pH on the biotite surface groups and sorption reactions. Three unique sorption sites were identified on the (1 1 0) edge surface: Fe–OH sites connected to Al via O atoms (site I), Fe–OH sites that were not adjacent to Al (site II), and Al–OH sorption sites. This research used these sites to develop models for inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexations under various pH conditions, and proposed two distinct reaction mechanisms for the same complexes that were formed at the same sorption sites under different alkaline and acidic conditions.

Under acidic conditions, Fe–OH2+ and Al–OH2+ sorption sites were most likely to be involved in the sorption reaction. Under neutral and alkaline conditions, Fe–OH and Al–OH sorption sites were more likely to be involved. In acidic environments, the neutral inner-sphere complexes FeSeH, AlSeH and neutral outer-sphere complexes FeOH2SeH and AlOH2SeH formed. In alkaline environments, the deprotonation of HSe− to Se2− results in the formation of inner-sphere anionic complexes Fe–Se− and Al–Se− and outer-sphere anionic complexes FeOH2Se− and AlOH2Se−.

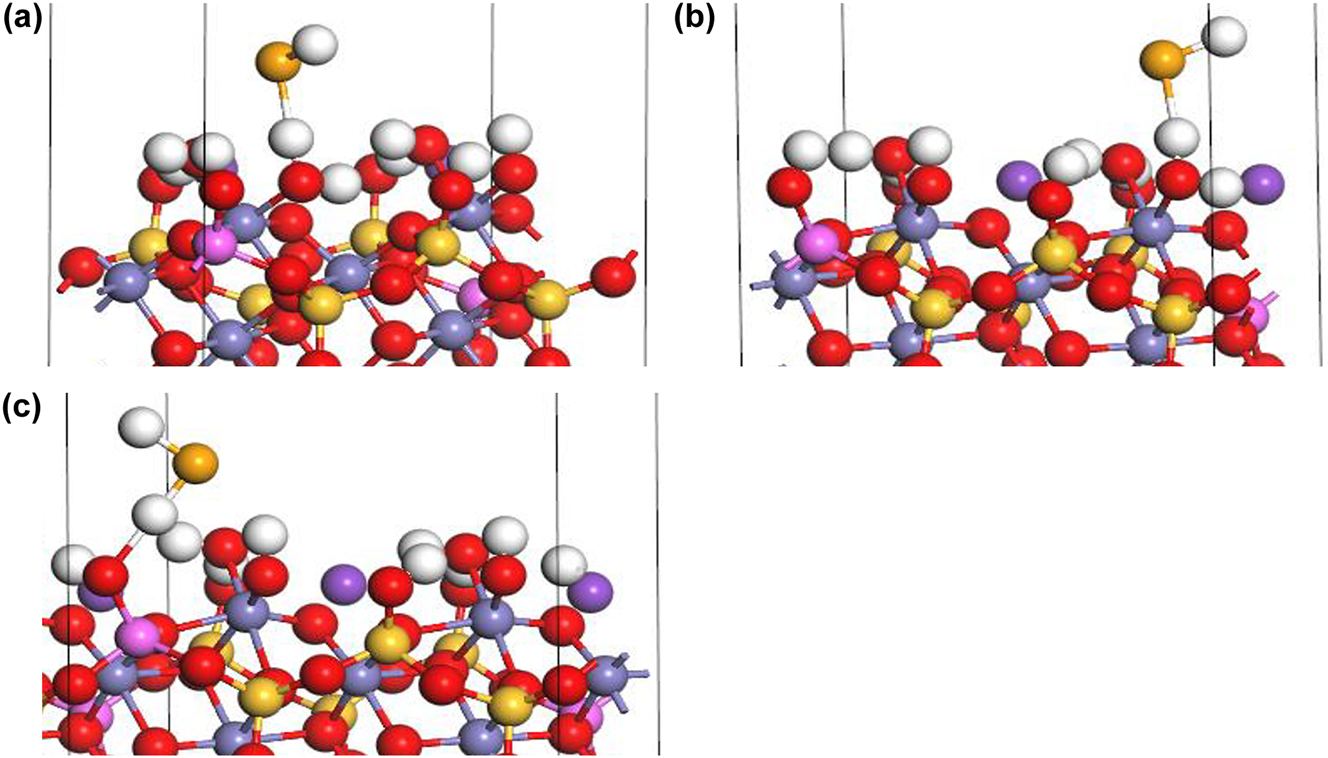

Under acidic conditions, HSe− binds with Fe–OH2+ sorption sites I (Figure 4a) and II (Figure 4b) to form an FeSeH inner-sphere complex while simultaneously releasing one H2O molecule:

Inner-sphere complexation of HSe− on biotite (1 1 0) edge surface under acidic conditions: (a) FeSeH at Fe–OH sorption site I (b) Fe–Se–H at Fe–OH sorption site II, and (c) AlSeH at Al–OH sorption sites (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink, Se: orange).

HSe− binds with Al–OH2+ sites (Figure 4c) to form an Al–Se–H inner-sphere complex while simultaneously releasing a H2O molecule:

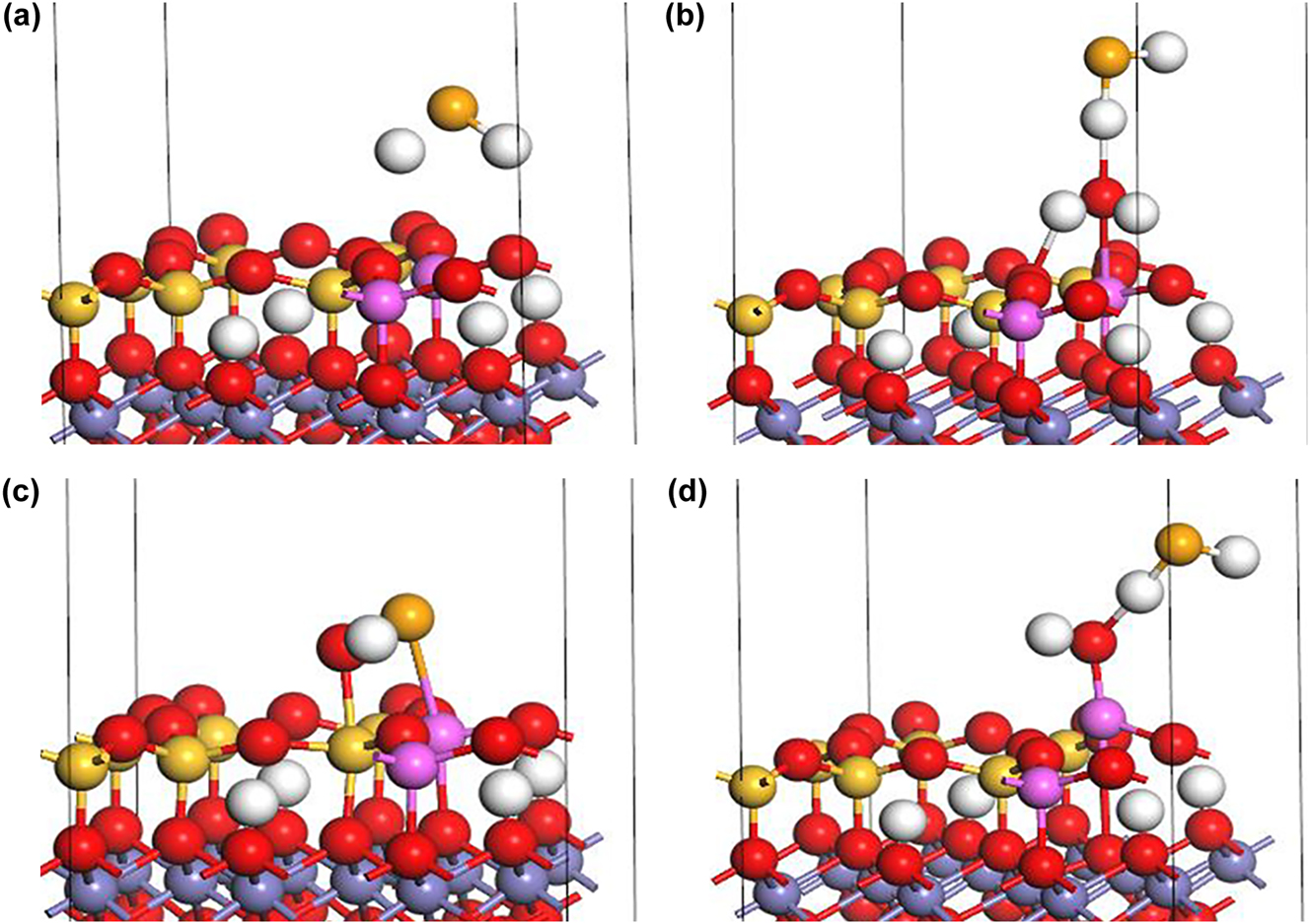

Under acidic conditions, the outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at Fe–OH2+ sorption site I (Figure 5a) and II (Figure 5b) involves a change in the coordination environment of the Fe atom, which form the new complex FeOH2SeH:

Outer-sphere complexation of HSe− on biotite (1 1 0) edge surface under acidic conditions: (a) FeOH2SeH at Fe–OH sorption site I, (b) FeOH2SeH at Fe–OH sorption site II, and (c) AlOH2SeH at Al–OH sorption site (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink, Se: orange).

The outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at Al–OH2+ sites (Figure 5c) involve a change in the coordination environment of the Fe atom due to the introduction of a Se atom, which form AlOH2SeH:

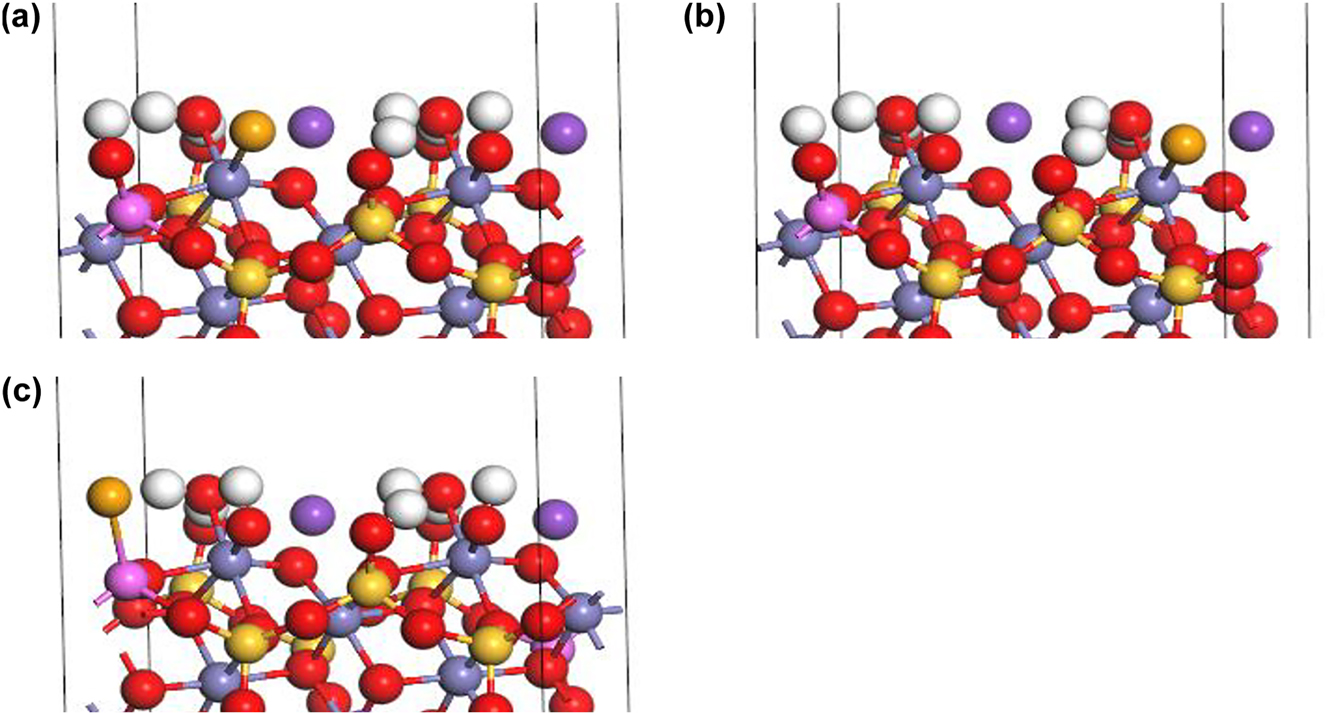

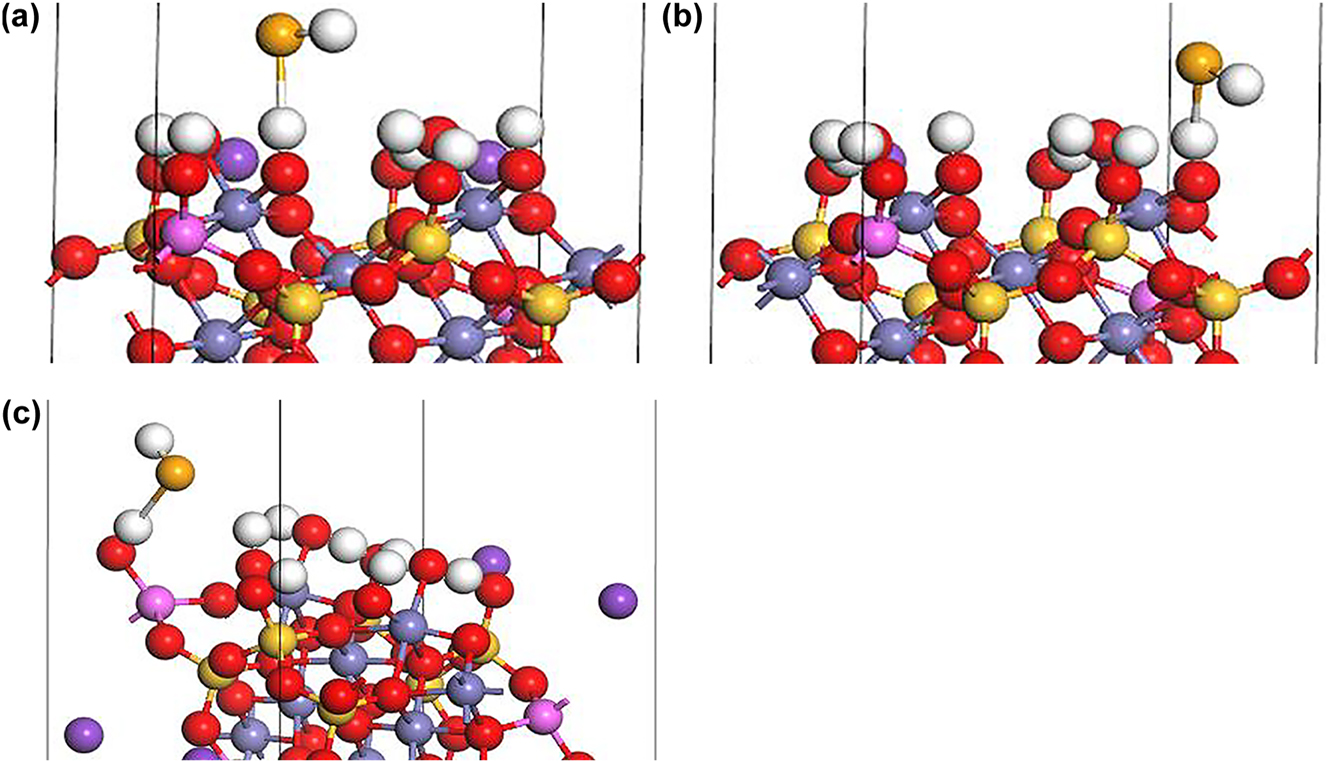

Under alkaline conditions, the inner-sphere complexation of HSe− at Fe–OH site I (Figure 6a) and II (Figure 6b) form a FeSe− complex through direct bonding between HSe− and Fe atoms accompanied by the generation of a H2O molecule:

Inner-sphere complexation of HSe− on biotite (1 1 0) surface under alkaline conditions: (a) Fe–Se− at Fe–OH sorption site I, (b) Fe–Se− at Fe–OH sorption site II, and (c) Al–Se− at Al–OH sorption site (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink, Se: orange).

Similarly, the inner-sphere complexation of HSe− at Al–OH sorption sites (Figure 6c) form an AlSe− complex accompanied by the generation of a H2O molecule:

Under neutral conditions, the outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at Fe–OH sites I (Figure 7a) and II (Figure 7b) changes the coordination environment of the Fe atom due to the introduction of the Se atom, which results in an additional proton and the formation of FeOH2SeH:

Outer-sphere complexation of HSe− on biotite (1 1 0) surface under neutral conditions: (a) FeOH2SeH at Fe–OH sorption site I. (b) FeOH2SeH at Fe–OH sorption site II, and (c) AlOH2SeH at Al–OH sorption site (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink, Se: orange).

The outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at Al–OH sites (Figure 7c) form AlOH2SeH due to the presence of the additional proton:

Under alkaline conditions, the outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at the Fe–OH sites I (Figure 8a) and II (Figure 8b) form FeOH2Se−:

Outer-sphere complexation of HSe− on biotite (1 1 0) surface under alkaline conditions: (a) FeOH2Se− at Fe–OH sorption site I, (b) FeOH2Se− at Fe–OH sorption site II, and (c) AlOH2Se− at Al–OH sorption site (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink, Se: orange).

The outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at Al–OH sites form AlOH2Se−:

3.2 Sorption of Se (-II) species on (0 0 1) surface

The (0 0 1) basal surface was selected because of the relatively weak chemical interactions between potassium ions and other layers resulting from the layered structure of biotite. Al is connected to O atoms on the (0 0 1) surface, and Al–OH has been identified as main sorption site for Se (-II) on biotite. 14 , 22 Therefore, we established a partially hydrolyzed atomic structure on the (0 0 1) surface, which includes Al–OH sorption sites. The formation and involvement of Fe–OH in sorption were not considered because the selected (0 0 1) surface lacks an Fe atom. We investigated the potential formation of inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexes at Al–OH sorption sites and the influence of the pH on the sorption reaction and surface groups.

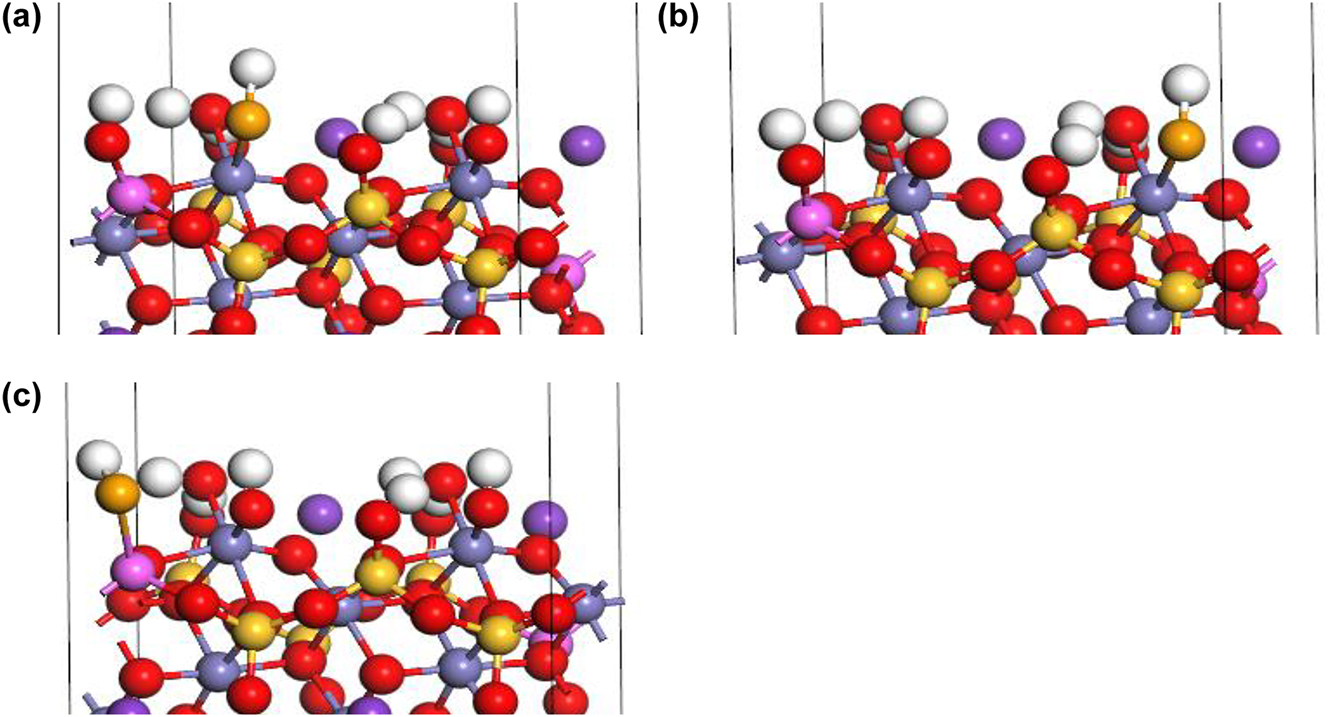

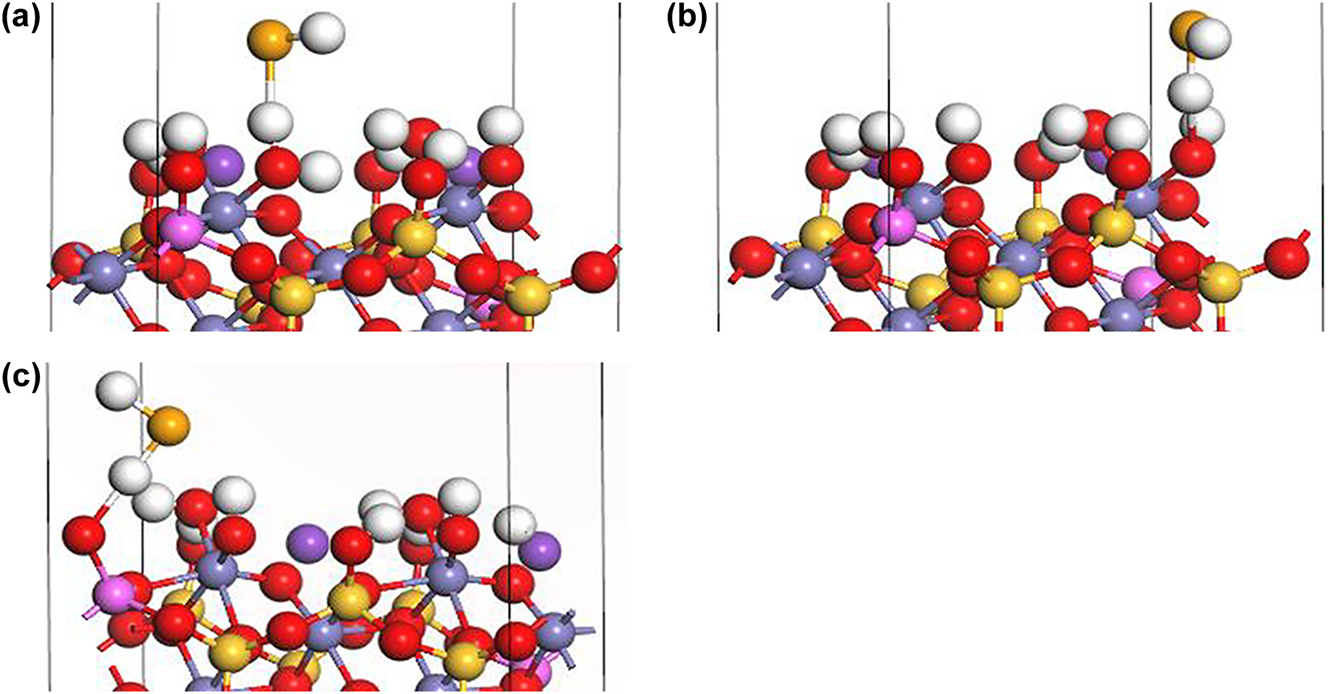

The inner-sphere complexation of HSe− at the Al–OH2+ sites in an acidic environment (Figure 9a) while releasing a H2O molecule, is given in Equation (3). The outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at the Al–OH2+ sites (Figure 9b) form AlOH2SeH in an acidic environment, as given by Equation (5), as well as in a neutral environment, as given by Equation (9). The inner-sphere complexation of HSe− at Al–OH sites in an alkaline environment (Figure 9c) form AlSe− and releases a H2O molecule, as given by Equation (7). The outer-sphere complexation of HSe− at Al–OH sites (Figure 9d) in an alkaline environment form AlOHSeH−, as given by Equation (11).

Complexation of HSe− at Al–OH sites on the (0 0 1) biotite surface: (a) Inner-sphere complexation under acidic conditions, (b) outer-sphere complexation under acidic and neutral conditions, (c) inner-sphere complexation under alkaline conditions, and (d) outer-sphere complexation under alkaline conditions (H: white, K: purple, O: red, Si: yellow, Fe: gray, Al: pink, Se: orange).

3.3 Sorption energies

Tables 1 and 2 present the sorption energies of HSe− on the (1 1 0) and (0 0 1) biotite surfaces, where a negative sorption energy indicates an exothermic process that stabilizes the absorbate molecule and promotes the formation of a stable sorption complex.

Sorption energies (eV) of HSe− on (1 1 0) biotite surface at different sorption sites.

| Sorption energy (eV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Complexation | Fe–OH site I | Fe–OH site II | Al–OH site |

| Acidic | Inner-sphere | −1.78 (Fe–OH2+) | −1.80 (Fe–OH2+) | 12.80 (Al–OH2+) |

| Outer-sphere | −0.71 (Fe–OH2+) | −0.60 (Fe–OH2+) | 12.47 (Al–OH2+) | |

| Neutral | Outer-sphere | −2.82 | −2.96 | 1.02 |

| Alkaline | Inner-sphere | −1.58 | −1.65 | 12.80 |

| Outer-sphere | −0.42 | −0.93 | 12.91 | |

Sorption energies (eV) of HSe− on (0 0 1) surface at Al–OH sorption sites.

| pH | Complexation | Sorption energy (eV) on Al–OH site |

|---|---|---|

| Acidic | Inner-sphere | −2.10 (Al–OH2+) |

| Outer-sphere | −1.74 (Al–OH2+) | |

| Neutral | Outer-sphere | −1.94 |

| Alkaline | Inner-sphere | 2.71 |

| Outer-sphere | −1.25 |

On the (1 1 0) surface, sorption was more likely to occur at the Fe–OH/Fe–OH2+ sorption sites than at the Al–OH/Al–OH2+ sorption sites under various pH conditions. Inner-sphere complexation tended to occur in acidic and alkaline environments while outer-sphere complexation was the dominant sorption mechanism in neutral environments.

On the (0 0 1) surface, Fe–OH/Fe–OH2+ sorption sites were absent while Al–OH/Al–OH2+ were the primary sorption sites. Inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexation occurred in acidic environments whereas outer-sphere complexation was dominant mechanism in neutral and alkaline environments.

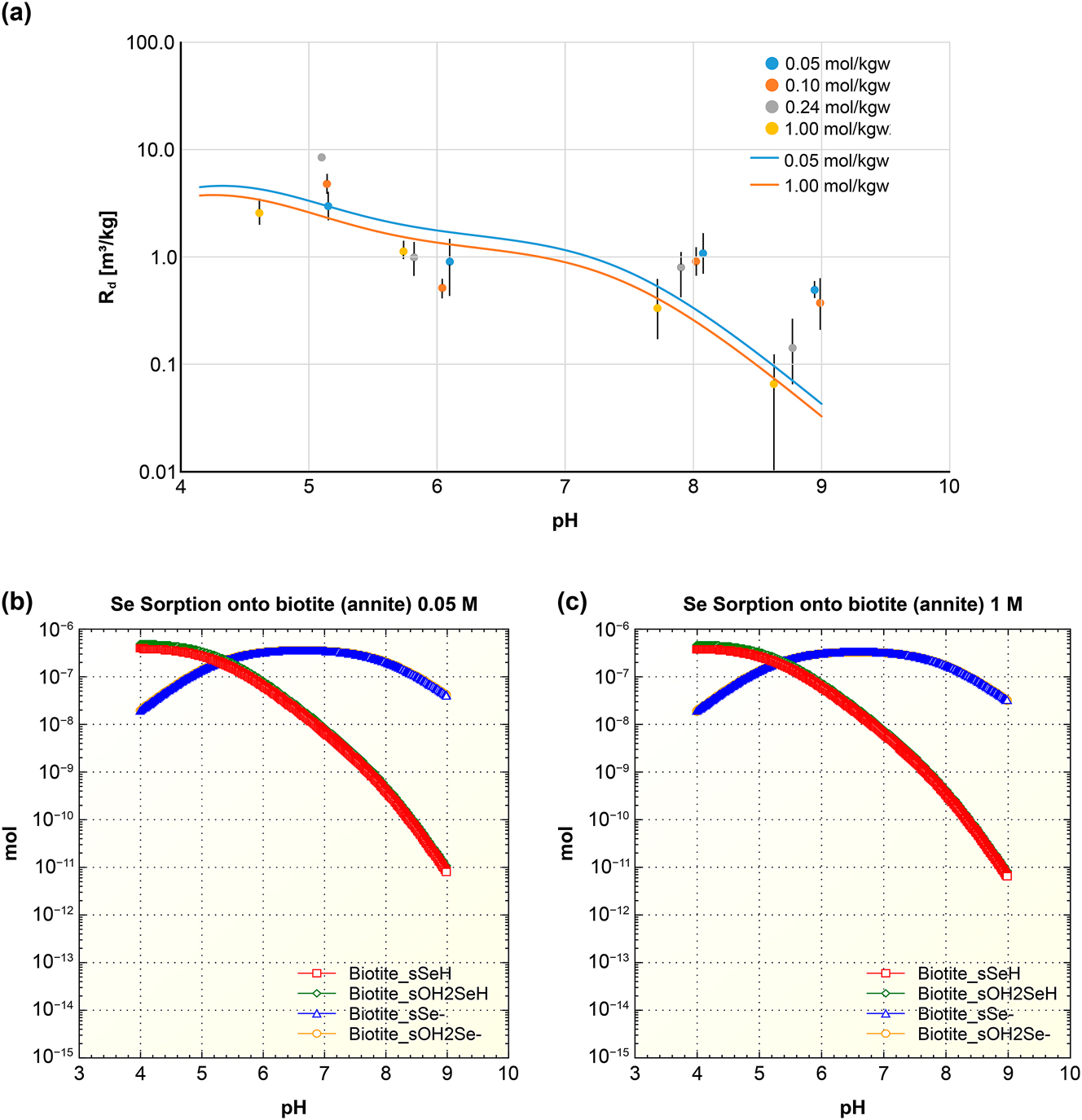

4 Comparison with experimental data

The results of the present study were validated by comparison to the experimental results obtained in the previous study, 14 where we measured the sorption of Se (-II) onto granite in Ca–Na–Cl solutions at different ionic strengths (0.05, 0.10, 0.24 and 1.0 mol/kgw) and pH 4–10 conditions (symbols in Figure 10a). The hydrogeochemical code PHREEQC 38 was used to construct a surface complexation model of Se (-II) sorption on biotite fitted to the experimental data (lines in Figure 10a). The inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexation reactions were integrated into the sorption model. The sorption sites on the (1 1 0) edge surface and (0 0 1) basal surface was considered strong sorption site, and they were set to a specific surface area of 1.0323 m2/g. 12 The number of sites per square nanometer was set to 1.72 based on the results of Li et al., 12 Puhakka et al., 25 and the (1 1 0) edge surface model and (0 0 1) basal surface model. In this study, the five surface complexation reactions identified through DFT calculations were incorporated into the sorption model, and their reaction constants were determined by fitting to the experimental data using the surface complexation modeling with PHREEQC (version 3.8.2). Table 3 presents the optimized surface complexation reaction constants.

PHREEQC model of Se (-II) sorption on bionite: (a) Isotherm in Ca–Na–Cl solutions (symbols), and the resultant surface complexation model (lines). (b) Speciation in ionic strength 0.05 M Ca–Na–Cl solution. (c) Speciation in ionic strength 1 M Ca–Na–Cl solution.

Surface complexation reactions and optimized surface complexation constants for sorption of Se (-II) on granite/biotite.

| Complexation | Surface complexation reaction | Log K | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic | Inner-sphere |

|

6.2 |

| Outer-sphere |

|

6.2 | |

| Neutral | Outer-sphere |

|

10.9 |

| Alkaline | Inner-sphere |

|

5.5 |

| Outer-sphere |

|

5.5 |

Overall, the sorption of Se (-II) on biotite exhibited a typical anionic sorption trend, where the sorption decreases as the solution pH increased. The sorption surface complexation modeling by PHREEQC showed a good agreement with the experimental data (Figure 10a). The speciation of Se (-II) on biotite in Ca–Na–Cl solutions at ionic strengths of 0.05 M (Figure 10b) and 1 M (Figure 10c) demonstrates that the inner-sphere complex biotite_sSeH and outer-sphere complex biotite_sOH2SeH matched the experimental data under acidic conditions. Similarly, the inner-sphere complex biotite_sSe− and outer-sphere complex biotite_sOH2Se− matched the experimental data under alkaline conditions. It demonstrates that the DFT calculations can be used to determine the primary sorption products of Se (-II) on biotite.

5 Discussion and conclusions

Understanding the long-term sorption behavior of Se (-II) under complex geochemical conditions is important for the safety assessment of the DGR for nuclear waste. Spectroscopic techniques would be useful to explore the sorption mechanisms of radionuclides on the surface of minerals and rocks. However, the low concentrations of Se (-II) in Ca–Na–Cl solutions, due to its low solubility, limit the effectiveness of conventional spectroscopic techniques. In this study, the DFT simulation and the surface complexation sorption modeling with PHREEQC were used to investigate the sorption mechanisms of Se (-II) on biotite under various pH conditions.

The results indicated that the sorption of Se (-II) on biotite is characterized by a typical anionic sorption trend dominated by inner-sphere and outer-sphere complexation reactions. Fe–OH/Fe–OH2+ sorption sites on the (1 1 0) edge surface and Al–OH/Al–OH2+ sorption sites on the (0 0 1) basal surface serves as effective sorption sites that form stable complexes. For Fe–OH sites on the (1 1 0) edge surface, the inner-sphere complex is dominant while the outer-sphere complex is significant under acidic conditions. The outer-sphere complexes are significant under neutral conditions. The inner-sphere complex is dominant while the outer-sphere complex is significant under alkaline conditions. For Al–OH sites on the (0 0 1) basal surface, the inner-sphere complex is dominant while the outer-sphere complex is also significant under acidic conditions. The outer-sphere complex is dominant under neutral and alkaline conditions.

In this study, considering the time frame involved in the migration of radioactive Se from nuclear waste in the geosphere (e.g., 1 million years), weak sorption sites were not considered in the sorption model. However, the impact of weak sorption sites on the short-term sorption kinetics of Se remained significant. Future research may involve investigating the impact of coexisting ions in solution on the sorption behavior of Se (-II). Furthermore, the potential impact of other rock components in granite may be assessed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the sorption behavior of Se (-II) in complex geological systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Joshua Racette with his guidance on the use of PHREEQC and Material Studio.

-

Research ethics: This study was conducted in accordance with all applicable ethical guidelines.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

-

Research funding: This research is funded by the Nuclear Waste Management Organization.

-

Data availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

1. Hall, D. S.; Behazin, M.; Jeffrey Binns, W.; Keech, P. G. An Evaluation of Corrosion Processes Affecting Copper-Coated Nuclear Waste Containers in a Deep Geological Repository. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 118, 100766; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100766.Search in Google Scholar

2. Ewing, R. C. Long-term Storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 252–257; https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4226.Search in Google Scholar

3. Rashwan, T. L.; Asad, Md A.; Molnar, I. L.; Behazin, M.; Keech, P. G.; Krol, M. Exploring the Governing Transport Mechanisms of Corrosive Agents in a Canadian Deep Geological Repository. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 153944; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153944.Search in Google Scholar

4. Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Weng, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q. Tensile Strength Degradations of Mineral Grain Interfaces (MGIs) of Granite after Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical (THM) Treatment. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 171, 105592; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105592.Search in Google Scholar

5. Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Progress on Rock Mechanics Research of Beishan Granite for Geological Disposal of High-Level Radioactive Waste in China. Rock Mech. Bull 2023, 2, 100046; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rockmb.2023.100046.Search in Google Scholar

6. Song-Sheng, J.; Ming, H.; Li-Jun, D.; Jing-Ru, G.; Shao-Yong, W. Remeasurement of the Half-Life of 79Se with the Projectile X-Ray Detection Method. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2001, 18, 746–749; https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/18/6/311.Search in Google Scholar

7. Jörg, G.; Bühnemann, R.; Hollas, S.; Kivel, N.; Kossert, K.; Van, W. S.; Gostomski, C. L. V. Preparation of Radiochemically Pure (79)Se and Highly Precise Determination of its Half-Life. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2010, 68, 2339–2351; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2010.05.006.Search in Google Scholar

8. Atwood, D. A. Radionuclides in the Environment; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

9. Lehto, J.; Hou, X. Chemistry and Analysis of Radionuclides: Laboratory Techniques and Methodology, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2011.10.1002/9783527632770Search in Google Scholar

10. Shin, K. Possible Effect of Pressure Solution on the Movement of a Canister in the Buffer of Geological Disposal System. Int. J. Geosci. 2017, 8, 167–18000; https://doi.org/10.4236/ijg.2017.82006.Search in Google Scholar

11. Ikonen, J.; Voutilainen, M.; Söderlund, M.; Jokelainen, L.; Siitari-Kauppi, M.; Martin, A. Sorption and Diffusion of Selenium Oxyanions in Granitic Rock. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2016, 192, 203–211; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2016.08.003.Search in Google Scholar

12. Li, X.; Puhakka, E.; Ikonen, J.; Söderlund, M.; Lindberg, A.; Holgersson, S.; Martin, A.; Siitari-Kauppi, M. Sorption of Se Species on Mineral Surfaces, Part I: Batch Sorption and Multi-Site Modelling. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 95, 147–157; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2018.05.024.Search in Google Scholar

13. Yang, X.; Ge, X.; He, J.; Wang, C.; Qi, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Effects of Mineral Compositions on Matrix Diffusion and Sorption of 75Se(IV) in Granite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1320–1329; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b05795.Search in Google Scholar

14. Racette, J.; Walker, A.; Nagasaki, S.; Yang, T. T.; Saito, T.; Vilks, P. Influence of Ca-Na-Cl Physicochemical Solution Properties on the Adsorption of Se(-II) onto Granite and MX-80 Bentonite. T. T. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 55, 3831–3843; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2023.06.049.Search in Google Scholar

15. Aaltonen, I.; Engström, J.; Gehör, S.; Kosunen, P.; Kärki, A.; Paananen, M.; Paulamäki, S.; Mattila, J. A. Geology of Olkiluoto, 2016. POSIVA Report.Search in Google Scholar

16. Li, X.; Puhakka, E.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Ikonen, J.; Lindberg, A.; Siitari-Kauppi, M. Multi-site Surface Complexation Modelling of Se(IV) Sorption on Biotite. Chem. Geol. 2020, 533, 119433; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2019.119433.Search in Google Scholar

17. Lanin, E. S.; Sone, H.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, B. Comparison of Biotite Elastic Properties Recovered by Spherical Nanoindentations and Atomistic Simulations – Influence of nano Scale Defects in Phyllosilicates. JGR Solid Earth: Solid Earth 2021, 126,e2010JB021902; https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB021902.Search in Google Scholar

18. Rabung, T.; García Cobos, D.; Montoya, V.; Molinero, J. Final Workshop Proceedings of the Collaborative Project ‘Crystalline Rock Retention Processes’ (7th EC FP CP CROCK). KIT Scientific Report 2013; https://doi.org/10.5445/KSP/1000037468.Search in Google Scholar

19. Ervanne, H.; Hakanen, M.; Lehto, J. Selenium Sorption on Clays in Synthetic Groundwaters Representing Crystalline Bedrock Conditions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, 307, 1365–1373; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-015-4254-7.Search in Google Scholar

20. Missana, T.; Alonso, U.; García-Gutiérrez, M. Experimental Study and Modelling of Selenite Sorption onto Illite and Smectite Clays. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 334, 132–138; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2009.02.059.Search in Google Scholar

21. Iida, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tanaka, T.; Nakayama, S. Solubility of Selenium at High Ionic Strength under Anoxic Conditions. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2010, 47, 431–438; https://doi.org/10.3327/jnst.47.431.Search in Google Scholar

22. Iida, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nakayama, S. Sorption Behavior of Selenium(-II) on Rocks under Reducing Conditions. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 279–291; https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.2011.9711702.Search in Google Scholar

23. Geng, R.; Wang, W.; Din, Z.; Luo, D.; He, B.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J.; Li, P.; Fan, Q. Exploring Sorption Behaviors of Se(IV) and Se(VI) on Beishan Granite: Batch, ATR-FTIR, and XPS Investigations. J. of Mol. Liq. 2020, 309, 113029; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113029.Search in Google Scholar

24. Marouane, B.; Chen, N.; Obst, M.; Peiffer, S. Competing Sorption of Se(IV) and Se(VI) on Schwertmannite. Minerals 2021, 11, 764; https://doi.org/10.3390/min11070764.Search in Google Scholar

25. Puhakka, E.; Li, X.; Ikonen, J.; Siitari-Kauppi, M. Sorption of Selenium Species onto Phlogopite and Calcite Surfaces: DFT Studies. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2019, 227, 103553; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2019.103553.Search in Google Scholar

26. Kim, S.-S.; Min, J.-H.; Baik, M.-H.; Kim, G.-N.; Choi, J.-W. Estimation of the Behaviors of Selenium in the Near Field of Repository. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2012, 44, 945–952; https://doi.org/10.5516/net.06.2012.010.Search in Google Scholar

27. Masscheleyn, P. H.; Delaune, R. D.; Patrick, W. H. Transformations of Selenium as Affected by Sediment Oxidation-Reduction Potential and pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1990, 24, 91–96; https://doi.org/10.1021/es00071a010.Search in Google Scholar

28. Naveau, A.; Monteil-Rivera, F.; Guillon, E.; Dumonceau, J. Interactions of Aqueous Selenium (−II) and (IV) with Metallic Sulfide Surfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 5376–5382; https://doi.org/10.1021/es0704481.Search in Google Scholar

29. Sugiura, Y.; Tomura, T.; Ishidera, T.; Doi, R.; Francisco, P. C. M.; Shiwaku, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Matsumura, D.; Takahashi, Y.; Tachi, Y. Sorption Behavior of Selenide on Montmorillonite. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2020, 324, 615–622; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-020-07092-x.Search in Google Scholar

30. Kremleva, A.; Krüger, S.; Uranyl, R. N. VI) Sorption in Calcium Silicate Hydrate Phases: A Quantum Chemical Study of Tobermorite Models. Appl. Geochem. 2020, 113, 104463; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2019.104463.Search in Google Scholar

31. Ai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lan, W.; Jin, J.; Xing, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, X. The Effect of pH on the U(VI) Sorption on Graphene Oxide (GO): A Theoretical Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 343, 460–466; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.03.027.Search in Google Scholar

32. Kuta, J.; Wang, Z.; Wisuri, K.; Wander, M. C. F.; Wall, N. A.; Clark, A. E. The Surface Structure of α-uranophane and its Interaction with Eu(III) – an Integrated Computational and Fluorescence Spectroscopy Study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 103, 184–196; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.10.056.Search in Google Scholar

33. Xing, J.; Wang, C.; Zou, C.; Zhang, Y. DFT Study of Se and SeO2 Adsorbed on CaO (0 0 1) Surface: Role of Oxygen. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 510, 145488; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145488.Search in Google Scholar

34. Heberling, F.; Vinograd, V. L.; Polly, R.; Gale, J. D.; Heck, S.; Rothe, J.; Bosbach, D.; Geckeis, H.; Winkler, B. A Thermodynamic Adsorption/entrapment Model for Selenium(IV) Coprecipitation with Calcite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 134, 16–38; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.02.044.Search in Google Scholar

35. Séby, F.; Potin-Gautier, M.; Giffaut, E.; Borge, G.; Donard, O. F. X. A Critical Review of Thermodynamic Data for Selenium Species at 25°C. Chem. Geol. 2001, 171, 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2541(00)00246-1.Search in Google Scholar

36. Jensen, F. Introduction to Computational Chemistry, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

37. Clark, S. J.; Segall, M. D.; Pickard, C. J.; Hasnip, P. J.; Probert, M. I. J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M. C. First Principles Methods Using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 2005, 220, 567–570; https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.220.5.567.Search in Google Scholar

38. Parkhurst, D. L.; Appelo, C. A. J. Description of Input and Examples for PHREEQC Version 3 – A Computer Program for Speciation, Batch-Reaction, One-Dimensional Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations. U.S. Geol. Surv. Tech. Methods 2013, 6, 497.10.3133/tm6A43Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Papers

- Utilization of traceable standards to validate plutonium isotopic purification and separation of plutonium progeny using AG MP-1M resin for nuclear forensic investigations

- DFT study of Se(-II) sorption on biotite in reducing conditions

- 140Ba → 140La radionuclide generator: reverse-tandem scheme

- Estimation of valuable metals content in tin ore mining waste of the Russian Far East region by instrumental neutron activation analysis

- Optimizing vulcanized natural rubber: the role of phenolic natural antioxidants and ionizing radiation

- The gamma radiation shielding properties of tin-doped composites: experimental and theoretical comparison

- Effect of replacing ZnO with La2O3 on the physical, optical, and radiation shielding properties of lanthanum zinc tellurite

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Papers

- Utilization of traceable standards to validate plutonium isotopic purification and separation of plutonium progeny using AG MP-1M resin for nuclear forensic investigations

- DFT study of Se(-II) sorption on biotite in reducing conditions

- 140Ba → 140La radionuclide generator: reverse-tandem scheme

- Estimation of valuable metals content in tin ore mining waste of the Russian Far East region by instrumental neutron activation analysis

- Optimizing vulcanized natural rubber: the role of phenolic natural antioxidants and ionizing radiation

- The gamma radiation shielding properties of tin-doped composites: experimental and theoretical comparison

- Effect of replacing ZnO with La2O3 on the physical, optical, and radiation shielding properties of lanthanum zinc tellurite