Abstract

Idioms represent a significant challenge for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners, including Moroccan high school students. This study explores the effectiveness of an action research intervention aimed at enhancing idiom comprehension through the application of embodiment and Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) strategies. In this regard, a group of high school students (n=216) participated in targeted training designed to facilitate their understanding of idiomatic expressions. The results indicate a marked improvement in students’ ability to comprehend idioms post-intervention. The data reveal that, across all idioms, 55.97% of responses were accurate interpretations, 36.17% were erroneous interpretations, and 6.71% were responses of “I don’t know”. This indicates that, on average, individuals correctly interpreted the idioms more frequently than they misinterpreted them, with a relatively small percentage expressing uncertainty. These findings underscore the importance of integrating embodiment and conceptual strategies in EFL pedagogy, highlighting their role in enriching the conceptual frameworks of learners, even in the context of a foreign language. This study contributes to the current body or research on effective teaching methods to help EFL students acquire figurative language skills. It also highlights the applications of the CMT and embodiment paradigms.

1 An Introduction to Embodiment

Embodiment has emerged as one of the central and widely discussed topics within cognitive science and philosophy. Gibbs (2017: 450) defines embodiment as “the ways persons’ bodies and bodily interactions with the world shape their minds, actions, and personal, cultural identities”. In other words, embodiment refers to the profound impact our bodies and bodily experiences have on our cognitive processes, behaviors, and self-perceptions.

Cognitive science recognized a clear shift toward embracing embodiment after previously adhering to disembodied perspectives that take on a computational approach to cognition. Therefore, a new research program known as “embodied cognition”[1] started to take shape in accordance with second-generation cognitive science (Johnson 2018). As Gibbs (2017) asserts, this evolution of cognitive science has led scholars to acknowledge the vital influence of the body’s physical presence on intelligent behavior. Therefore, the primary objective of this research program is to accentuate the intertwinement of the brain and body in shaping cognition, viewing cognitive processes as extending into the organism’s environment rather than being confined to neural signals alone (Shapiro 2007). This does not only enrich our understanding of cognition but also suggests that enhancing physical experiences could significantly improve cognitive development and performance. Subsequently, an embodied approach to the mind and language holds that human symbols arise from the ongoing cycles of physical experience and the active interplay between our mental processes, physical bodies, and the environment (Gibbs 2017).

According to Foglia and Wilson (2013: 3), the embodiment thesis proposes that the body has two separate yet interrelated functions, each influencing our understanding and study of cognitive processes. The first role or function is described as the “body as a constraint on cognition”. This is where the body seemingly shapes both the nature of cognitive activities and the content of the representations that are being processed. An example of this can be found in the well-renowned book Metaphors We Live By by Lakoff and Johnson (1980), which posits, for instance, that metaphors related to space and time are both shaped by and express bodily experiences, as in the famous metaphor love is a journey. This metaphor draws on our understanding and conceptualization of love in terms of the physical capacity for movement, thereby showcasing how our bodies and embodied experiences are essential to the ways we conceptualize the world around us. The second role highlighted by Foglia and Wilson (2013: 4) is embodiment as a “Distributor for Cognitive Processing”, which suggests that the body allocates cognitive tasks between neural and non-neural structures, serving as a partial realization of mental phenomena. In other words, our bodies help manage cognitive tasks by dividing them between the brain (the neural structures) and other bodily systems (the non-neural anatomical structures), suggesting that our physical experiences play a key role in shaping our thoughts and mental processes.

Embodiment extends to all human experiences and thus does not exclude emotions. In effect, Farina (2021) emphasizes the significance of embodiment in relation to emotions by shedding light on how bodily states influence emotional experiences and cognitive processes. To support this claim, he cites the study by Oberman et al. (2007), which tested the hypothesis that impairing the ability to use facial muscles associated with specific emotional expressions leads to a reduced ability to recognize those emotions (Farina 2021). This shows a direct link between bodily expressions and emotional recognition, underscoring the idea that our emotional experiences are deeply interconnected with our physical embodiment. Certainly, the influence of embodiment on emotion extends beyond mere emotional recognition to include the conceptualization of emotions (see Barrett and Lindquist 2008).

2 Conceptual Metaphor Theory

Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT),[2] originated by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson (1980), contends that metaphors are pervasive and fundamental cognitive tools that shape our understanding of the external world, rather than mere literary devices. In this regard, Kövecses (2017) notes that, since conceptual metaphors are prevalent in everyday language, they are deeply embedded in the mental lexicon of native speakers and reflect a significant level of polysemy and idiomaticity within the same cognitive structure.

According to Lakoff and Johnson (1980), a conceptual metaphor refers to the understanding of an abstract concept (target domain) in terms of a more concrete physical one (source domain). Gibbs (2017) clarifies that the conceptual mapping of metaphors goes beyond merely listing shared features between the source and target domains given that conceptual metaphors create a more organized understanding of the target domain. He further explains that individuals often interpret aspects of their lives through bodily experiences which serve as the embodied foundation for the source domains in metaphorical concepts. Moreover, it is pertinent to acknowledge that part of the embodied experience that motivates such mappings is rooted in and reinforced by the individual’s environment along with its sociocultural factors. This represents the second phase in the development of primary metaphors, following the first phase occurring early in cognitive development, in which foundational perceptual and conceptual neural connections are formed (Gibbs and Silva de Macedo 2010). Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 58, 59) delineate the types of conceptual metaphors and state that emotions are primarily connected to orientational metaphors, which frame feelings in spatial terms (e.g., HAPPY IS UP) based on bodily experiences like posture, whereas structural metaphors map one conceptual domain onto another (e.g., TIME IS MONEY). While structural metaphors convey and conceptualize intricate concepts, orientational metaphors adeptly represent our immediate emotional states.

Metaphors and metonymies are pervasive in everyday language, indicating that we frequently utilize metaphorical expressions in everyday conversation without perceiving them as such (e.g., “The opportunity slipped through my fingers”). Such expressions have become so conventionalized in a language through their frequent use that they have become lexicalized, that is, they are no longer perceived as metaphors but rather as lexical units in their own right. They have thus become what Gibbs and Nayak (1991: 93) have termed “dead metaphors”. However, it is important to note that not all metaphorical expressions are lexicalized or “dead”. Many metaphors remain dynamic and continue to shape our understanding of abstract concepts (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Gibbs 1991). Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) posits that metaphors are not merely linguistic expressions that are fixed, rigid, frozen, and dead but foundational cognitive structures that shape our understanding of the world (see Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Lakoff 1987; Gibbs 1991; Ungerer and Schmid 1996; Kövecses and Szabó 1996). In their 1991 study, Gibbs and Nayak identified a shift in opinion they attributed to the findings that “people’s conceptual understanding of different emotions influenced their interpretations of idioms in varying discourse contexts” (Gibbs and Nayak 1991: 9). Gibbs (1991) explains that these conceptual metaphors illustrate the mapping of knowledge from specific, concrete, source domains (e.g., containers, pressurized heat) onto relatively vague, abstract, multifaceted target domains.

In a study by Agus (2013), conceptual metaphors proved to underlie a great deal of emotional experiences. Interestingly, the findings of this study revealed that emotional expressions frequently utilized conceptual metaphors, with personification being a prominent semantic feature, allowing emotions to be depicted as human-like entities. This goes hand in hand with the third type of conceptual metaphors introduced by Lakoff and Johnson (1980): ontological metaphors, which they define as frameworks that help us conceptualize our experiences as distinct objects or substances and identify specific aspects of our experiences as separate and uniform entities. The pervasiveness of affective conceptual metaphors was further confirmed by a study conducted by Soriano (2015), which investigated the relationship between emotions and conceptual metaphors. Her study reveals that conceptual metaphors are deeply embedded in the way emotions are expressed across different languages. Moreover, she sheds light on how emotions are often conceptualized through more concrete domains, such as fire or illness, thus providing further evidence in support of the embodiment thesis, which posits that our bodily experiences shape our cognition.

3 Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) in the EFL Context

In recent decades, research on the acquisition of metaphorical expressions by learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) or English as a second language (ESL) has gained significant momentum (see Kövecses and Szabó 1996; Littlemore and Low 2006; Cameron and Deignan 2006; Radić Bojanić 2013; Zibin 2016). This theory has significant implications for English as a Foreign Language (EFL) education, particularly since learners often encounter idiomatic and metaphorical language during the learning process and in outside settings.

A substantial body of research has investigated the influence of CMT on EFL learners in diverse global contexts, demonstrating the cognitive and pedagogical advantages of metaphor instruction. The research conducted by Kövecses (2002) highlights the significance of metaphors in influencing cognitive processes and linguistic expression. Kövecses proposes that the teaching of these metaphors can facilitate learners’ comprehension of idiomatic expressions, thereby enhancing their overall language proficiency. Littlemore and Low (2006) conducted research which demonstrates that explicit metaphor instruction can result in notable enhancements in students’ comprehension and utilization of idiomatic expressions. This is consistent with the findings of Gibbs (1994), who identified that idiomatic expressions are processed through underlying conceptual metaphors. This indicates the necessity of metaphor training in EFL education, as it can assist learners in navigating the complexities of figurative language. In their 2002 study, Charteris-Black examined figurative expressions in English and Malay, investigating the similarities and differences between the two languages. Additionally, the study sought to anticipate the difficulties that Malay learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) (36 intermediate-level students) might encounter regarding figurative expressions. By analyzing metaphorical and metonymical expressions and their conceptual bases in English and Malay, Charteris-Black developed a model comprising six types of figurative units based on the correspondence between the linguistic expression and the conceptual basis in the two languages, as well as on the characteristics of the linguistic expressions and conceptual bases, which were classified as either culture-specific (i.e., opaque) or universal (i.e., transparent). The findings of Charteris-Black’s study indicate that students encountered challenges when confronted with linguistic expressions that diverged from the Malay norm regarding their conceptual and cultural foundations. Cameron (2003: 104) argued that metaphor instruction enhances learners’ communicative competence. She found that participants could make links between source and target domains, stating that “imagining lava as treacle or butter, they may indeed be making links between incongruent domains”.

Additionally, the extensive work of Boers and Lindstromberg (2009) provides valuable insights into the acquisition of figurative language and idiomatic expressions in L2, especially what Boers calls “prefabricated wholes [...] chunks [...] sequences of single words” (Boers and Lindstromberg 2009: 24). Their research highlights the pedagogical benefits of teaching these chunks through their conceptual and semantic bases, which aligns with the findings of this study. Moreover, Boers and Lindstromberg (2009: 24) assert that the factor of age is very important in the processing of such multiword units, arguing that it “appears that young children acquire semantic units consisting of two or more words holistically and realize only at a later stage that these units break down into a certain number of single words”. Furthermore, studies by Fiona McArthur (2017), Ana María Piquer-Píriz and Rafael Alejo-González (2020) offer additional perspectives on the role of metaphor in second language acquisition, emphasizing the importance of semantic, conceptual, and contextual factors in metaphor comprehension. MacArthur (2017) argues that there is little justification for the ongoing neglect of metaphor in EFL (English as a Foreign Language) and FL (Foreign Language) teaching. She warns metaphor analysts against overly focusing on embodied experiences, emphasizing that her research highlights how speakers draw on their cultural knowledge as a motivational basis.

In their 2009 study, Shokouhi and Isazadeh investigated how Iranian learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) can develop and utilize conceptual and image metaphors in their English language proficiency. They concluded that “EFL learners can benefit greatly by having well-organized materials such as production exercises and comprehension activities that will facilitate internalization of conceptual and image metaphors” (Shokouhi and Isazadeh 2009: 26). In a recent study, Zibin (2016) investigated the ability of Jordanian speakers to conceptualize “fear” using conceptual metaphor and embodied cognition. The study concluded that “JA relies heavily on cognitive embodiment in the conceptualization of FEAR” (Zibin 2016: 253). Soriano (2015) used “Metaphorical Profile Analysis”,[3] which is a method initially proposed by Orgarkova and Soriano (2014: 213), concluding that CMT can “inform us of the way communities represent their emotional experiences and can reveal underlying cultural differences”.

It is a challenging task for most foreign language teachers and learners to navigate such expressions in authentic contexts without a feasible methodology that adheres to a systematic and reliable approach (Kondaiah 2004). Educators should provide explicit instruction on metaphors, idiomatic expressions in our case, and their meanings to enhance learners’ understanding. Incorporating conceptual references into metaphor instruction can bridge comprehension gaps, making learning more relevant and relatable. Activities that promote metaphor and idiomatic awareness can improve language proficiency while encouraging students to create their own metaphors, thus fostering engagement and deeper understanding. Conceptual Metaphor Theory offers a rich framework for understanding and teaching English in EFL contexts. By recognizing the conceptual dimensions of metaphor usage, educators can develop effective teaching strategies that enhance learners’ comprehension and proficiency.

4 Idioms and Idiomaticity in the EFL Context

Idiomaticity has been the concern of diverse and multiple research studies, especially in the field of cognitive linguistics. The study of idiomaticity to explain how idiomatic expressions[4] are fabricated and used has shifted from considering them as fixed and unanalyzable sequences to being motivated and conceptually triggered. Idiomaticity’s purest goal is to uncover the layers of idiomatic use, moving from the traditional lexical view to the flexible and decomposable view. Grant and Bauer (2004) define idioms as fixed and recurring patterns of lexical material sanctioned by usage. They are formulaic expressions that cannot be understood by simply interpreting the meaning of their individual elements. Instead, the meaning must be inferred from the expression as a whole. The Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (2003: 741) defines an idiom as “a phrase which means something different from the meanings of the separate words; the way of statement typical of a person or people in their use of language” and The Collins English Dictionary defines it as “an expression such as a simile, in which words do not have their literal meaning, but are categorized as multi-word expressions that act in the text as units”, as cited in Shojaei (2012: 1221). Lattey (1986) points out that “as far as the form of idioms is concerned, we have groups of words, and in terms of meanings, we can say that we are dealing with new, not readily apparent meanings when we confront idioms” (Lattey1986: 219). Baker (1992: 69) identifies idioms as “frozen patterns” of language that allow little or no variation in form. Hoffman (1984, as cited in Cronk 1992: 132) argues that “the degree of frozenness is not fixed, and idioms can range from completely syntactically frozen to quite productive”. This is echoed by Carter (2012: 74), who notes that idioms have “different degrees of possible fixity or frozenness, both syntactic and semantic”. To illustrate the varying degrees of fixedness in idioms, consider the following examples: Highly fixed idioms: kick the bucket (meaning ‘to die’) is a prime example of a highly fixed idiom, as it allows no variation in form or substitution of words. One cannot substitute the bucket with the box or the pail and have the same meaning. Semi-fixed idioms permit a certain degree of variation in wording; however, they exhibit a greater degree of constraint compared to fully flexible idioms such as bite the bullet. We can say “they are biting bullets these days” or we can shift the tense as in “He bit the bullet” and keep the idiomatic meaning of enduring pain. On the other hand, flexible idioms like hit the sack (meaning ‘to go to bed’) allow some variation, such as hit the hay or crash the sack.

This definition focuses on two important characteristics that constrain the use of idioms: flexibility (productivity) at the level of pattern and transparency (as opposed to opacity) at the level of meaning. Idioms are therefore “semantically opaque” (Langlotz 2006: 15) and cannot be readily understood without prior knowledge of the cultural, conventional, and conceptual contexts in which they emerged. Idioms cannot be understood simply by looking up their individual words in a dictionary, as their meanings do not stem from a literal interpretation of those words. This often leads to ineffective communication and potential cultural misunderstandings.

A lot of researchers have tried to study idiomaticity (Chafe 1968; Makkai 1972; Gibbs 1985; Fillmore 1988; Nipold 1991; Cronk 1992; Flavell 1994; Cacciari 1996), and most of them had held an assumption that derives from the traditional treatment of idioms before opting for a revolutionary conceptual approach to the study of idioms (Gibbs and O’Brien 1991; Gibbs and Nayak 1991; Gibbs 1995; Kövecses and Szabó 1996; Makkai 2009, 2011). Because of this alleged arbitrary nature of idioms, it has long been taken for granted in second or foreign-language teaching that learners could only resort to contextual clues to interpret idioms (e.g., Cooper 1999: 258). In contrast to this traditional view of figurative and metaphoric language, Lakoff (1993) argues that metaphor is not merely a linguistic phenomenon but rather a fundamental aspect of our cognitive processes and an integral part of our conceptual system, as it enables the creation and extension of structures in our experience and understanding. El Yamani et al. (2025: 10) assert that “idioms are not merely strings of words or frozen patterns of language; rather, they are creative and motivated, and therefore, they often undergo conceptual processes when conveying ideas”.

It is a common experience among those who attempt to learn a second language at an early stage to encounter difficulties when attempting to comprehend spoken discourse due to the prevalence of idiomatic expressions. Learners frequently encounter difficulties in understanding conversations due to the potential reliance on the interpretation of pivotal idioms,[5] a view supported by the findings of Baker (1992: 64), who indicates that “a person’s competence in actively using the idioms and fixed expressions of a foreign language hardly ever matches that of a native speaker”. When learners utilize an idiomatic expression erroneously, native speakers may exhibit expressions of amusement or, in more severe instances, confusion because of their inability to comprehend the intended meaning. However, “avoiding the use of idioms results in a language that is perceived as bookish, stilted, and unimaginative” (Cooper 1999: 258). It is therefore of the utmost importance to learn how to use idioms to master the authentic language. To help learners master this crucial aspect of their second language (L2), teaching materials and techniques must be based on a comprehensive understanding of the conceptual processes involved in idiom comprehension. This includes recognizing the cultural contexts from which idioms emerge, understanding the figurative meanings behind them, and practicing their use in different communicative situations.

5 Methodology

5.1 Demographic Information on the Participants

The participants in this study were Moroccan high school students (n=216) from rural areas, specifically those in the 10th, 11th, and 12th grades. The sample included both genders, with 57.9% females and 42.1% males, all representing a diverse range of academic abilities, from high achievers to low achievers. A total of n=12 classes participated in the experiment, ensuring a comprehensive representation of the student population within this demographic.

Years of Studying English

Regarding their English language education, Moroccan students typically engage in one year of English instruction during middle school, followed by three years in high school. It is important to note that the participants in this study were not influenced by the recent educational reforms that have introduced English language instruction in the first and second years of middle school. Participants were asked about any additional years of English study, including autonomous learning outside of the school curriculum. The results indicate that while some students reported extensive English study, ranging from 4 to 12 years, the majority indicated 2 to 4 years of formal instruction. For instance, 19.8% had studied English for 2 years, 36.6% for 3 years, and 16.9% for 4 years. This suggests that most students have not actively pursued English language learning beyond the prescribed curriculum. However, idiomatic language is complex and reflects a more advanced level of language proficiency. Consequently, exposure to English in the classroom, which is only limited, does not adequately prepare learners to achieve this level of proficiency.

5.2 Research Instrument

Our study adopts an exploratory approach to investigate the understanding of English idioms among a sample of Moroccan high school students. In this regard, students were invited to fill out a questionnaire that presented a selection of English idioms related to feelings. The idioms were selected based on their relevance to emotional expressions and their varying degrees of transparency and opacity. The selection criteria included frequency of use in everyday English, cultural relevance, and the potential for metaphorical interpretation. The idioms were sourced from The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004) and Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998), which provide comprehensive definitions and examples of idiomatic expressions. Students indicated their understanding by selecting the correct interpretation or indicating they were unsure of the meaning. Subsequently, the responses were classified into three categories: “Correct Interpretation”, “Incorrect Interpretation”, and “I Don’t Know”. This format provides significant quantitative data on the prevalence of correct and incorrect understandings, thereby shedding light on the predominant conceptual frameworks involved in idiom comprehension.

The questionnaire was divided into three parts, all of which consisted of multiple-choice questions (MCQs). The first part included 20 questions, each presenting a sentence with an idiom highlighted in bold. Students were required to deduce the meaning of the idiom based on contextual clues provided in the sentence. Similarly, the second part contained another 20 questions, again focusing on idioms of feelings. In this part, students were asked to match idioms with their correct meanings from a list of options, ensuring a more interactive and engaging task. The final section comprised three reflective questions soliciting student feedback on the effectiveness of the training in Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) and embodiment. This part aimed at gauging the perceived impact of the instructional methods on students’ understanding of idioms.

5.3 Research Design

The research design was structured as an action research project comprising three distinct stages: pre-intervention, during the intervention, and post-intervention. The initial stage of the study introduced the first part of the questionnaire to assess the students’ baseline understanding of idioms. During this phase, the instructor introduced the concept of idioms, providing a few examples that were not included in the study to avoid any potential biasing of the results. The teachers facilitated the students’ selection of the correct answers, refraining from providing extensive explanations about the idioms themselves and the role of embodiment and CMT. This approach was designed to establish a clear baseline for measuring the students’ prior knowledge and understanding.

The intervention stage comprised a comprehensive introduction to the theories of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) and embodiment. Students were presented with examples from English, such as the well-known metaphor time is money (Lakoff and Johnson 1980). The teachers explained how this expression illustrates the abstract concept of time by relating it to something more tangible and readily available in the physical world, like money. In addition, students were provided with examples from their mother tongue, Moroccan Arabic, such as the phrase “ضربني بالعين” (Dˁrbni b-l-ʕiːn), meaning “he cast the evil eye on me”. This expression represents an example of a conceptual metaphor where the physical act of “casting” an eye symbolizes the abstract idea of envy or malice. The teachers explained how in this metaphor, the eye, a tangible entity, represents the intangible emotions of jealousy and harm, illustrating how cultures often use concrete imagery to express complex emotional experiences.

The aim of showcasing this comparative analysis was to enhance student comprehension of idiomatic expressions within their linguistic and cultural context. Similarly, teachers from two different Moroccan public high schools: Tafilalet High School in Errachidia’s directory and Skhour High School in Rehamna’s directory, elucidated the role of physical experiences and bodily references in the comprehension of abstract notions. Examples from both languages demonstrated how various body parts are culturally associated with different emotions, moral values, and character traits. The objective of this explanation was to facilitate student recognition of the embodied nature of language[6] and its implications for idiom interpretation. After the intervention, the students were requested to complete the second section of the questionnaire. The objective of this stage was to assess the extent to which students could apply the concepts learned from CMT and embodiment to decipher the meaning of idioms. As in the preliminary phase of the study, students were required to work independently. The objective of this stage was to assess the extent to which students could apply the concepts learned from CMT and embodiment to decipher the meaning of idioms. As in the pre-intervention phase, students worked independently without further assistance from the teacher, allowing for an evaluation of their understanding of post-intervention. The entire process, including the three stages, was designed to last one hour per class, ensuring that students received sufficient exposure to theories while allowing for interaction and engagement with the material. Conducted in March 2024, the study includes three appendices at the end, which provide supplementary materials such as the full list of idioms used in the study, the questionnaire template, and detailed statistical analyses of the results.

5.4 Research Questions

To systematically investigate the effectiveness of embodiment and Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) in enhancing idiom comprehension among Moroccan EFL learners, this study addresses the following research questions:

To what extent does an action research intervention incorporating embodiment and CMT strategies improve Moroccan high school students’ comprehension of English idioms?

What patterns emerge in students’ responses (correct interpretations, errors, or uncertainty) when engaging with idioms after the intervention?

How do embodiment and CMT-based strategies contribute to the conceptual restructuring of idiomatic meaning in an EFL context?

These questions aim to evaluate the pedagogical intervention’s impact while identifying cognitive and linguistic patterns in learners’ idiom processing. By focusing on accuracy, error types, context and learner’s physical experience, the analysis provides actionable insights for EFL instruction.

5.5 Hypotheses

Guided by prior research on embodied cognition and conceptual metaphor theory, this study tests the following hypotheses to assess the intervention’s theoretical and practical implications: H1: Students exposed to embodiment and CMT strategies will demonstrate significantly higher accuracy in idiom interpretation compared to pre-intervention performance. H2: Misinterpretations will predominantly stem from literal or L1-influenced mappings, but the intervention will reduce such errors by reinforcing conceptual metaphors. H3: The percentage of “I don’t know” responses will decrease post-intervention, suggesting increased learner confidence in idiomatic language processing.

6 Analysis

6.1 Pre-intervention Results

Most students demonstrated a concerted effort to identify the meanings of idioms, with only 6.9% to 14.8% indicating they did not understand the idiomatic expressions presented. However, a substantial number of students selected alternative meanings rather than the correct interpretation. While most participants were able to identify the correct meaning of the idioms, this group constituted just over half of the respondents across all prompts. Specifically, in only 4 out of 20 questions did more than 50% of students accurately identify the meaning. The lowest percentage of consensus among students was 38%, while the highest reached 59.7%. To measure the effectiveness of the pedagogical intervention, learning gains were calculated by comparing pre- and post-intervention scores. The average correct interpretation of the pre-intervention was 46.53%; post-intervention, the average correct interpretation was 55.83% with a learning gain of +9.3%. This approach allowed for a clear assessment of the impact of CMT and embodiment training on students’ comprehension of idioms. The data highlight significant difficulties in idiomatic understanding, suggesting a need for targeted educational strategies to enhance students’ grasp of idiomatic language.

Sample of the Findings from the First Part of the Study

| Idiom | Correct Interpretation (%) | Incorrect Interpretation (%) | I Don‘t Know (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrying the world’s weight on his shoulders. | 59.7% | 29.1% | 11.1% |

| Blood boil. | 45.4% | 44.4% | 10.2% |

| Blow off steam. | 43.1% | 45.4% | 11.6% |

| Lost his cool | 43% | 44% | 13% |

| Bent out of shape | 38% | 47.2% | 14.8% |

| Cold feet | 47.2% | 44.9% | 7.9 % |

| Butterflies in her stomach | 50% | 42.6% | 7.4% |

| Blood ran cold. | 55.6% | 32.9% | 11.6% |

| Hanging his head | 44.9% | 41.2% | 13.9% |

| Bored to tears. | 39.4% | 49.1% | 11.6% |

The data sample represents 50% of the total dataset. Nevertheless, the findings consistently replicate the broader trends indicated in the accompanying table. The idioms presented in Table 1 were selected at random, except for the first and fifth, which were intentionally chosen to illustrate the extremes of the findings. The initial MCQ yielded the most favorable results, with 59.7% of students successfully identifying the correct meaning of the idiom. In contrast, the fifth yielded the least favorable results, with only 38% of students accurately identifying the idiomatic meaning.

The findings suggest a notable degree of ambiguity and uncertainty among students regarding the accurate interpretation of idiomatic expressions. Several factors may be responsible for these unfavorable outcomes. First, English is the students’ third language, which presents inherent challenges in language acquisition. Second, as previously stated, students do not proactively engage in English language learning outside the formal curriculum. This lack of engagement is problematic, as learners often encounter idiomatic expressions in natural contexts outside the formal curriculum, in contrast to the more limited use of idioms in textbook language. In effect, De Wilde et al. (2019) stress the critical role of informal learning, asserting that traditional classroom instruction alone is inadequate for attaining language proficiency. They contend that genuine mastery of a language necessitates participation in “casual learning experiences in everyday life”, which facilitates practical application and deeper understanding of linguistic skills.

Thirdly, students typically receive only 2 to 4 hours of English instruction per week, which is insufficient for the gradual and natural acquisition of idiomatic expressions. Furthermore, it is evident that students lack a comprehensive understanding of idioms since they are not formally introduced to these expressions until the 12th grade. The belated introduction of idioms to the curriculum serves to compound the difficulties encountered by students in recognizing and comprehending idiomatic language. In conclusion, these factors collectively impede students’ capacity to comprehend idiomatic expressions effectively.

The involvement of educators in the clarification of idioms or the proactive integration of such expressions into English language instruction is notably constrained since the comprehension of this intricate linguistic structure encompasses a multitude of cultural nuances, in addition to other factors that warrant consideration. This situation underscores the pressing need for training programs specifically oriented toward idiomatic expressions and the theoretical frameworks underpinning them. Such training would not only assist students in accurately deducing the meanings of specific idioms but also equip them with the conceptual frameworks necessary to actively interpret any idiomatic expressions they encounter. This approach is demonstrably more productive than the passive acquisition of a limited number of idioms with fixed meaning as it fosters a more profound comprehension of idiomatic language and greater adaptability in its use.

In accordance with this approach, conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) and embodied cognition were used to investigate how Moroccan high school students comprehend English idioms related to feelings, utilizing conceptual metaphor theory (CMT) and embodied cognition. These theories suggest that our understanding of abstract concepts, such as emotions, is grounded in physical experiences and that cognitive processes are influenced by bodily interactions (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Glenberg 2010). By examining students’ interpretations of various idioms, this research aims to identify the effectiveness of these theoretical frameworks in enhancing idiom comprehension. The study investigates the comprehension of English idioms related to emotions by Moroccan high school students through the lenses of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) and Embodied Cognition. CMT posits that abstract concepts are understood through more concrete, often sensorimotor, domains, forming conceptual metaphors (Lakoff and Johnson 1980). The theory of Embodied Cognition builds upon this by proposing that cognitive processes are inextricably linked with bodily experiences and sensorimotor interactions (Barsalou 2008; Gibbs 2005; Glenberg 2010). This analysis is centered on the responses of students to a questionnaire designed to assess their comprehension of a range of idioms related to emotions, in an attempt to elucidate the extent to which these responses align with the tenets of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) and the principles of Embodied Cognition.

6.2 Post-intervention Results

Evidence of embodiment and CMT can be found in language, as demonstrated by the use of idioms of emotion in the conceptualization of many target domains discussed in this paper. Many idioms illustrate the pervasive mapping of emotions onto physical sensations, which constitutes a central tenet of CMT and embodiment. The idioms “my heart sank” (60.6% correct) and “heavy heart” (58.3% correct) exemplify the metaphorical mapping of sadness as a downward movement or physical burden, as proposed by Lakoff and Johnson (1980). The relatively high success rates indicate that this metaphorical mapping is readily accessible. However, the 18.1% and 18.5% of incorrect interpretations for “My heart sank” and “Heavy heart,” respectively, may indicate that some informants could not activate the meaning of these idioms based on the body-part as a lexical key,[7] perhaps because of its confusion with other related emotional states.

Percentages of accuracy in students’ responses

| Idiom | Correct Interpretation (%) | Incorrect Interpretation (%) | I Don‘t Know (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| My heart sank | 60.6% | 18.1% | 5.6% |

| Heavy heart | 58.3% | 33.3% | 8.3% |

| Throw in the towel | 48.1% | 43% | 8.8% |

| Walking on air | 73.1% | 23.2% | 3.7% |

| Breathing fire | 63.9% | 30.5% | 5.6% |

| Pulling my hair out | 54.6% | 39.4% | 6.0% |

| Feel the burn | 53.2% | 36.1% | 10.6% |

| Lose face | 61.6% | 32.4% | 6.0% |

| Steam coming out of ears | 49.5% | 41.2% | 9.3% |

| Jumping up and down | 70.4% | 24.5% | 5.1% |

| Burst a blood-vessel | 60.2% | 31.9% | 7.9% |

| Weak at the knees | 37.5% | 57.4% | 5.1% |

| Tickled pink | 38.4% | 56.5% | 5.1% |

| Shakes like a leaf | 54.2% | 38.9% | 6.9% |

The results of the post-intervention test reveal interesting patterns related to the percentages of correct and incorrect interpretations. CMT, which posits that abstract concepts are understood via concrete ones (Lakoff and Johnson 1980), is crucial here, as idioms are prime examples of such metaphorical mappings. Table 2 demonstrates a clear correlation between the concreteness and embodied nature of an idiom and its comprehension rate. Idioms such as “walking on air” (73.1% correct) and “jumping up and down” (70.4% correct), which are strongly grounded in physical experiences of lightness, movement, and joy, exhibit high levels of accuracy, a finding that further supports the embodiment thesis, which posits that our bodily experiences influence our comprehension of abstract concepts (Johnson 1987). These idioms are closely associated with image schemas, basic patterns of bodily interaction such as up-down and motion (Johnson 2007), which further contribute to their ease of understanding. In contrast, idioms with more abstract or culturally specific meanings demonstrate lower success rates. The results of the survey provide compelling evidence for the effectiveness of the training approach that incorporated Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) and Embodied Cognition. The findings (55.97% accuracy, 36.17% errors, and 6.71% uncertainty) provide empirical support for Hypotheses 1 and 3, while Hypothesis 2 invites further qualitative analysis of error sources. Collectively, these hypotheses underscore the potential of embodied and metaphor-based approaches to transform EFL idiom pedagogy.

Factors that helped participants understand the meaning of idioms

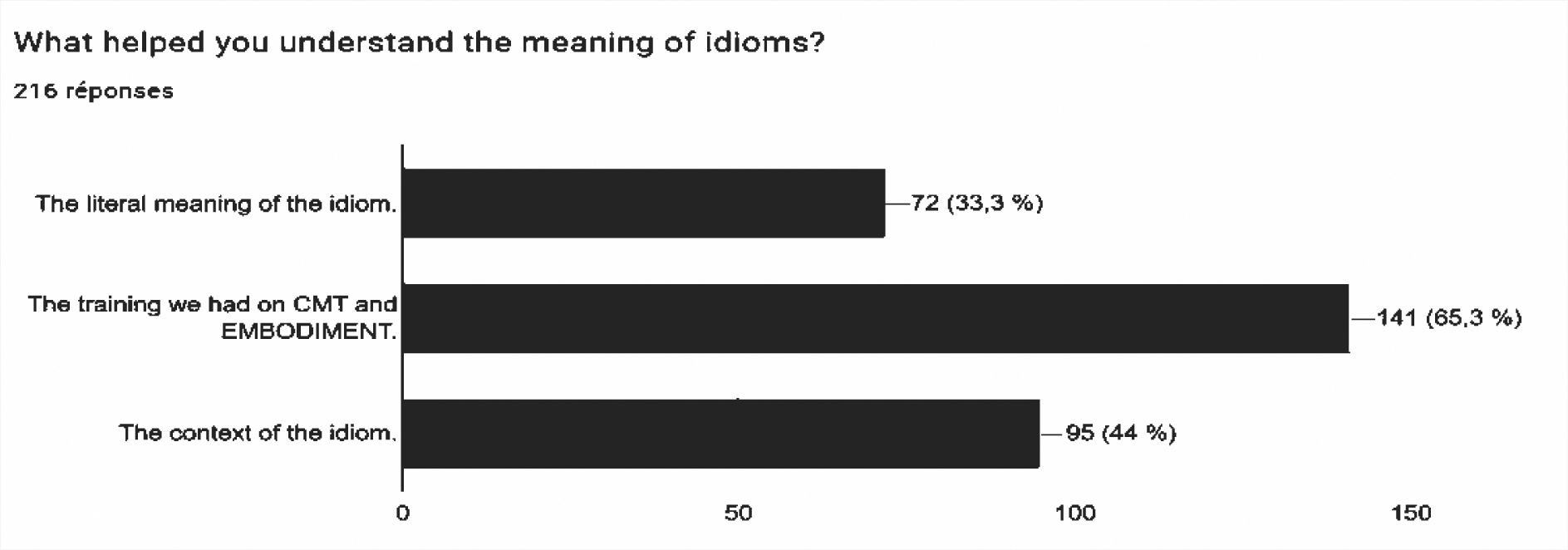

A significant majority of respondents (65.3%) attributed their understanding of idioms to the training they had in the post-intervention test, thereby underscoring its pivotal role in facilitating comprehension. This strongly suggests that by focusing on the metaphorical and embodied aspects of idioms, the training empowered learners to move beyond literal interpretations and grasp the deeper, figurative meanings of idioms. Moreover, 44% of respondents identified “the context of the idiom” as beneficial, thereby underscoring the value of contextualized learning, thereby highlighting the necessity for educators to present idioms within authentic communicative contexts that emphasize the role of embodied cognition to enhance comprehension. The relatively low impact attributed to “The literal meaning of the idiom” (33.3%) serves to reinforce the notion that a significant proportion of idioms cannot be directly interpreted based on their literal meanings, a finding that emphasizes the need for pedagogical approaches that extend beyond literal translations and delve into the metaphorical and embodied dimensions of language.

While some idioms appear to possess a transparent embodied basis, grounded in universal physical experiences, their interpretation can be significantly hindered by a lack of cultural familiarity, as evidenced by the responses to “weak at the knees” (37.5% correct) and “tickled pink” (38.4% correct). Despite evoking tangible physical sensations, such as weakness in the legs and a flushed complexion informants faced challenges in decoding the intended cultural connotations, indicating a failure to bridge the gap between the concrete physical image and the abstract conceptual meaning. As Gibbs (1994) contends, comprehending idioms demands more than mere recognition of the individual words; it necessitates accessing the underlying conceptual metaphors and cultural knowledge associated with them. This echoes Makkai’s (1972: 122) assertion that idioms are “subject to a possible lack of understanding despite familiarity with the meanings of the components, or to erroneous decoding: they can potentially mislead the uninformed listener, or they can disinform him”. The significant proportions of erroneous interpretations for “weak at the knees” (57.4%) and “tickled pink” (56.5%) directly reflect this potential for misinterpretation, as evidenced by the present study. This potential is further illustrated by the idiom “shakes like a leaf” (54.2% correct). While this expression also draws on a physical image (the trembling of a leaf in the wind), it is arguably more abstract and culturally loaded than the previous examples. The image of a leaf can evoke a range of emotional states, including fear, nervousness, or cold, and the specific interpretation depends on the context and cultural understanding. Yu and Maalej (2011) posit that research on embodied cognition should explore the linkages between embodiment and cultural meaning, given that people actually instill different cultural meanings into bodily processes in changing cultural contexts. The significant proportion of erroneous decoding[8] for the idiom “shakes like a leaf” (38.9%) reinforces this assertion, indicating that while image schemas derived from embodied experience contribute to idiom comprehension, cultural context and the level of opacity of the metaphorical mapping are pivotal factors. These findings indicate that the perceived transparency of an idiom’s embodied basis does not guarantee successful comprehension. Sometimes certain idioms also lack the conceptual structure that motivates their use and comprehension; Kövecses and Szabó (1996: 330) mention cases where there is a “complete absence of conceptual motivation” and provide the idiom “kick the bucket” as an example (although this example can be etymologically explained and extract the conceptual root henceforth).[9]

The percentages of accurate and erroneous interpretations, in addition to the responses marked “I don’t know”, are indicative of the interplay between embodiment, conceptual schemas, cultural context, and the degree of abstraction in idiom comprehension. Idioms rooted in direct physical experience and universal conceptual schemas are more readily comprehensible, while those reliant on cultural knowledge or more opaque mappings present greater challenges, underscoring the significance of incorporating these factors in language teaching.

Students’ views on which idioms they found easier

The results clearly demonstrate the efficacy of the training approach that integrated Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) and Embodied Cognition in enhancing idiom comprehension. A significant majority of respondents (78.2%) indicated they found idioms easier to understand after receiving the training, while only 26.4% reported they found them easier to understand without it. This considerable discrepancy illustrates the substantial influence of training in enhancing idiom comprehension. By focusing on the metaphorical and embodied aspects of language, the training likely enabled learners to move beyond literal interpretations and grasp the deeper, figurative meanings of idioms.

Saaty (2016) conducted a study that aimed to explore how teaching methods that raise awareness of conceptual metaphors, particularly through enactment techniques, affect students’ ability to comprehend, retain, and use the metaphor LIFE IS A JOURNEY in writing. By comparing the results with a control group that was taught the same metaphorical expressions as a semantic cluster, Saaty shows that students’ understanding and retention of these expressions improve significantly when they are taught to recognize conceptual metaphors by, for instance, guessing and establishing connections between the source and target domains. The greatest improvement was observed among students who engaged in physically enacting the expressions, highlighting the effectiveness of embodied learning approaches.

Percentage of students who agreed or disagreed with the effectiveness of CMT and embodiment in facilitating their comprehension of idioms

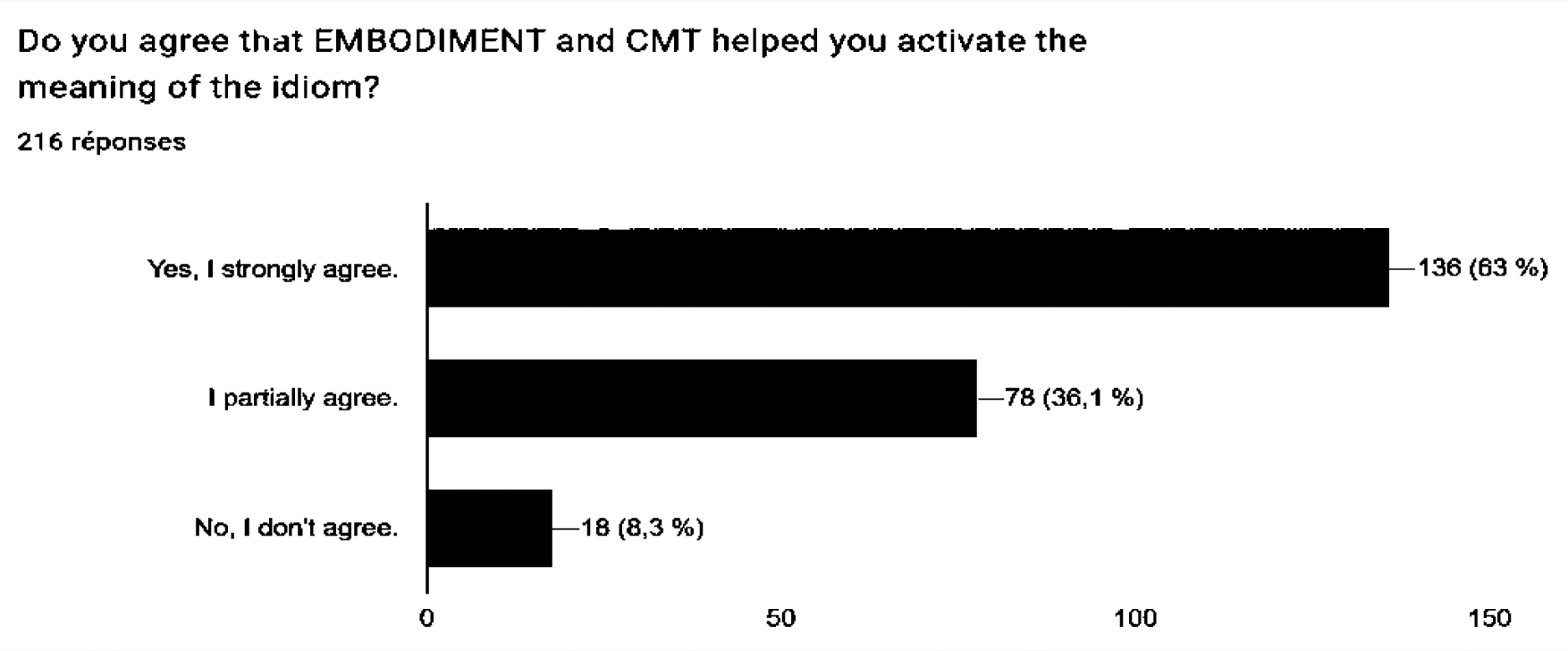

The results clearly demonstrate the positive impact of the training approach that integrated Embodiment and CMT in activating the meaning of idioms. A significant majority of respondents (63%) indicated they strongly agreed that the training was helpful, thereby indicating a high level of student satisfaction and perceived effectiveness. An additional 36.1% of respondents indicated partial agreement, suggesting that while the training provided valuable insights, its impact varied across different idioms. A mere 8.3% of respondents expressed disagreement with the training’s effectiveness. These findings provide compelling evidence that the training approach, which incorporates principles of embodiment and CMT, effectively assisted students in comprehending the meaning of idioms. These findings reinforce the value of integrating theoretical frameworks such as Embodiment and CMT into language instruction since they enhance students’ ability to comprehend idioms.

7 Does Opacity Impede the Process of CMT and Embodiment?

The concept of idiom opacity, which ranges from transparent to fully opaque (Gibbs 1986), has been demonstrated to significantly influence learner comprehension. Idioms that are transparent, where the meaning is readily inferable from the literal components, present minimal difficulty for learners. The idioms “walking on air” and “jumping up and down,” which directly evoke feelings of happiness and excitement, respectively, illustrate this accessibility. Due to the close alignment between the literal and figurative senses, learners can readily grasp the intended meaning, indicating that when the relationship between the individual words and the overall meaning is evident, comprehension is enhanced. In contrast, semi-opaque idioms offer partial clues but necessitate inferential processes and cultural knowledge. Idioms such as “heavy heart”, which suggests an emotional burden but requires inferring sadness, and “pulling my hair out”, which hints at frustration but does not specify its intensity, present a moderate challenge. Similarly, the idiom “shakes like a leaf” evokes the image of trembling but necessitates an inferential leap to associate it with fear. These examples demonstrate that while learners may be able to discern some meaning from the literal components, contextual or cultural information is essential for a comprehensive understanding. Idioms that are fully opaque present the greatest difficulty, including idioms such as “throw in the towel”, where the reference to surrendering is not immediately obvious, “tickled pink”, with its connection to amusement, and “shakes like a leaf”, where the conceptual imagery requires cultural context to be linked to fear and there is no clear semantic link between the literal and figurative meanings. Accordingly, fully opaque idioms require explicit instruction in comprehension and greater exposure to such expressions.

The observed pattern demonstrates that idiom opacity has a direct impact on comprehension, with transparent idioms being the most accessible, followed by semi-opaque, and fully opaque idioms, with the latter being the most challenging. The degree of transparency and opacity of the idioms was determined based on the following criteria: 1) transparency: idioms whose meanings can be inferred directly from their literal components (e.g., “walking on air”); 2) semi-opacity: idioms that offer partial clues but require cultural or contextual knowledge for full comprehension (e.g., “heavy heart”); and 3) full opacity: Idioms whose meanings are not inferable from their literal components and require explicit instruction (e.g., “throw in the towel”).

These findings have significant implications for pedagogical practice, indicating the necessity for differentiated instructional approaches contingent on the degree of opacity to optimize the use of CMT and embodiment for the best possible results.

8 Conclusion and Recommendations

The findings of this study have implications for several different fields. In the field of language education, the findings lend support to the integration of metaphorical frameworks into English as a Foreign Language (EFL) curriculum, as evidenced by the efficacy of idiom teaching through this approach demonstrated by Nation (2001) and Baker (1992). Such integration creates more engaging and effective language learning experiences. From the perspective of cognitive linguistics, the present study offers empirical evidence concerning the influence of embodiment and metaphor on language comprehension, as postulated by Lakoff and Johnson (1980) and Langacker (1987). By examining how students process idioms, the research sheds light on the cognitive mechanisms underlying language learning. Furthermore, an understanding of idioms requires cultural awareness, as they often embody cultural nuances (Kramsch 1993; Byram 1997; Yu and Maalej 2011). The exploration of culturally specific idioms fosters cultural competence, which is essential for effective global communication.

Future research should delve deeper into the complexities of idiom comprehension by adopting a cross-linguistic and cross-cultural perspective. As Cameron and Low (1999) argued, comparative studies are crucial for uncovering the universal and language-specific aspects of idiomatic processing. For instance, an investigation into how different cultures conceptualize emotions through metaphorical idioms (e.g., a comparison of anger metaphors in English and Arabic) could reveal underlying cognitive similarities and culturally specific variations. Such investigations could explore whether explicit instruction on the metaphorical basis of idioms leads to better retention compared to rote memorization, and how idiomatic competence contributes to advanced language skills like fluency and naturalness. Moreover, teachers and pedagogues should know the importance of understanding metaphors as a discourse phenomenon for EFL students, and the unhelpfulness of adopting strict native speaker norms for understanding metaphor use, as emphasized by McArthur (2016).

The present study proposes several pedagogical strategies for facilitating students’ comprehension of idioms, building upon the insights gained from cognitive linguistics and embodiment theory. Acknowledging the challenges posed by idiomatic expressions due to their cultural specificity and contextual dependence (Gibbs 1994; Barsalou 2008), these strategies aim to enhance the learning process by making it more engaging and meaningful. A pivotal approach is that of contextual learning, which involves the presentation of idioms within rich narrative contexts through storytelling and role-playing. This pedagogical approach enables students to infer the intended meaning from the surrounding discourse and comprehend the function of idioms in authentic communication. For instance, in lieu of a mere definition, a teacher might employ a short skit in which a character utilizes the idiom prior to a performance, thereby rendering its meaning clear through lining the intended meaning with its embodied nature and conceptual properties. Another important strategy is the utilization of culturally relevant examples: idioms are often deeply embedded in cultural practices and beliefs, and explaining their cultural origins can significantly enhance comprehension. For instance, elucidating the etymological context of the idiom “carry coal to Newcastle” can enhance its memorability. The incorporation of interactive activities, such as idiom-based games, discussions, and creative writing exercises, can promote active learning and facilitate more profound processing. The active deployment of idioms in varied contexts and the continuous exposure to such expressions foster the internalization of their meanings, thereby facilitating a more nuanced comprehension of their usage. These pedagogical approaches are consistent with research emphasizing the importance of contextualization and active learning in vocabulary acquisition (Nation 2001), specifically as regards idiom learning (Boers and Lindstromberg 2009).

In a nutshell, this study highlights the pedagogical value of explicit idiom instruction in fostering both cognitive flexibility and communicative competence. To put these findings into practice, we suggest concrete strategies such as contextualized role-playing activities (e.g., simulating real-life scenarios in which idioms are organically encountered and physically interpreted) and multimodal reinforcement (e.g., combining idioms with visual aids or short film clips to enhance retention). In addition, we emphasize the broader implications of idiom mastery for language development: (1) improving fluency by treating idioms as lexical strings that accelerate speech production, (2) refining pragmatic competence through exercises in inferring tone/intent (e.g., distinguishing between literal and ironic idiomatic usage), and (3) cultivating cognitive and intercultural awareness by tracing the conceptual connotations of idiomatic lexical elements and comparing cross-linguistic idiomatic variation.

Appendix A. Questionnaire 1. Idioms of feelings with no training on CMT and Embodiment

Embodied feelings: Exploring Idioms of Feelings Among Moroccan High School Students.

Two lists of 40 idioms of feeling will be provided to Moroccan high school students. The students will be provided with a list of 20 idioms and required to ascertain the accurate meaning of each without any prior training on conceptual metaphor theory and embodiment. Subsequently, the students will be presented with another list of 20 idioms of feelings following a period of training on conceptual metaphor analysis. The study will examine the conceptual processes by which students comprehend and interpret the meaning of idioms, as well as the role of embodiment in facilitating their understanding. In addition, the study will investigate the efficacy of integrating conceptual approaches in the context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) instruction.

Idioms of feelings list 1: (NO TRAINING ON CMT AND EMBODIMENT IS PROVIDED)

Choose the correct meaning of the following idioms.

She got cold feet before her wedding and almost canceled.

To get physically cold due to low temperatures.

To feel nervous or hesitant about a big decision.

To feel excited.

I don’t know the meaning of the idiom.

The unfair treatment at work really made her blood boil.

To cause intense anger or irritation.

To boil your blood as a medical condition.

To feel relaxed and comfortable.

I don’t know the meaning of the idiom.

After a tough week, he went for a run to blow off steam.

To physically blow steam from a kettle.

To blow off steam because you are angry.

To release pent-up and held back energy or emotion in order to feel relieved.

I don’t know the meaning of the idiom.

He lost his cool when the car broke down again.

To become agitated or lose your temper.

To physically cool down from heat.

To feel satisfied.

I don’t know the meaning of the idiom

She has butterflies in her stomach before the important job interview.

She is sick because she ate butterflies.

She’s nervous and stressed.

She feels confident.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

When she heard the loud crash, her blood ran cold.

To feel sad and disappointed.

To feel fear or shock.

To experience a decrease in blood temperature.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

After losing the game, he was hanging his head in disappointment.

To show shame or disappointment.

To hang your head down due to a heavy object.

To express approval and agreement.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

The lecture was so dull, I was bored to tears.

To feel anxious.

To cry tears as a reaction to a boring situation.

To be extremely bored.

I don’t know the meaning of the idiom.

She looked down in the mouth after hearing the bad news.

To have something physically wrong with your mouth.

To be very happy and ecstatic.

To be sad or gloomy.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He felt sick at heart after saying goodbye to his dearest friend.

His dearest friend has heart problems.

To feel deep sadness or regret.

To be tired of someone.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He tried to save face by apologizing for his mistake.

To preserve one’s dignity or reputation.

To cover your face to protect it from damage.

To pretend to be someone else.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

The horror movie was scary enough to curl my hair.

To actually curl someone’s hair using a curling iron.

To feel very pleased and content.

To shock or scare someone.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He feels like he’s carrying the world’s weight on his shoulders.

To physically carry the entire world on your back.

To feel burdened by responsibilities.

To give up.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

She was seeing red when she found out about the betrayal.

To be very angry.

To have a vision problem that makes everything appear red.

To feel careless and reckless.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

I had to bite the bullet and get my wisdom teeth removed.

To literally bite a bullet.

To feel afraid and terrified.

To face a difficult situation with courage.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

After the holidays, he was feeling blue and a bit lonely.

To feel sleepy and exhausted.

To physically turn blue in color.

To feel sad or depressed.

I don’t know the meaning of the idiom.

His constant complaining really got under my skin.

To have something physically under your skin.

To feel bored and depressed.

To be annoyed or irritated by someone or something.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He got bent out of shape when they changed the plans last minute.

To bend an object out of shape.

To be upset or annoyed.

To feel rejected and unwanted.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

Sarah was foaming at the mouth because her father told her that he will take her to the zoo.

To be extremely excited.

To be thirsty.

To have foam actually forming at the corners of your mouth.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

I was pulling my hair out trying to solve that math problem.

To literally remove your hair.

To feel hopeful and optimistic.

To be extremely frustrated or stressed.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

Appendix B. Questionnaire 2. Idioms of feelings with training on CMT and Embodiment

Idioms of feelings list 2:

Choose the correct meaning of the following idioms.

After the good news, I felt like I was walking on air.

To walk above the ground.

To feel extremely happy.

To be doubtful.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

The kids were jumping up and down when their mother told them about going on a picnic.

To jump due to a physical issue.

To feel dizzy and dazzled.

To be very excited or enthusiastic.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

She was so frustrated; I thought she might burst a blood-vessel.

To experience a medical condition causing blood to leak.

To become extremely angry or stressed.

To be very excited.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

After that workout, I could really feel the burn.

To feel stressful and worried.

To experience a strong sensation from exercise.

To feel something burning on your skin.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

She was worried she might lose face if she didn’t perform well.

To have a facial injury or disfigurement.

To suffer a loss of respect or reputation.

To feel confident.

I don’t know the meaning of this idioms.

The coach was breathing fire after the team’s poor performance.

To exhale flames like a dragon.

To be very energetic.

To express intense anger.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He still carries a torch for his ex-girlfriend.

To have unrequited love for someone.

To physically carry a lit torch.

To be unsecure and unsafe.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

Your dog is getting on my nerves.

Your dog is making me feel annoyed.

Your dog is very adorable.

Your dog is sitting on my legs.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

I went weak at the knees.

I feel tired because of the hard efforts I have done.

I have a health issue with my knees.

I feel powerfully affected by something.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

My heart sank when I saw the bad grade on my paper.

To feel loved be someone.

To have a physical sensation of sinking.

To feel disappointed or sad.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

She left with a heavy heart after the farewell party.

To have a heavy heart due to weight.

To feel very shocked.

To feel deep sorrow or grief.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

After months of trying, he decided to throw in the towel.

To have a feeling of defeat and surrender.

To throw away a towel.

To be courageous and audacious.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

The track’s horn made me jump out of my skin.

To literally jump out of your own skin.

To be extremely happy.

To feel a sudden jolt of fear.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He was tickled pink when he received the surprise gift.

To be literally tickled until you turn pink.

To have a pink-colored skin due to blushing.

To be very pleased or delighted.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

Tom was up in arms after finding that his little brother spoiled his book.

To be very angry or agitated about something.

To raise your arms in celebration.

To prepare for a physical fight or battle.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

She shakes like a leaf when she watches a horror movie.

To physically shake due to cold weather.

To tremble from excitement or joy.

To be extremely scared.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

He was hopping mad because his sister ate his cookies.

To feel very bored.

To be jealous.

To feel very angry.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

Finishing the project was a weight off my shoulders/my mind.

I felt relieved after finishing the project.

I felt anxious after finishing the project.

The project was easy and was not a big deal.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

Jane was pulling her hair out trying to solve that complicated math problem.

To literally remove strands of your hair from your scalp.

To solve the complicated math problem easily.

To be extremely frustrated or stressed.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

After the long meeting with so many interruptions, I felt like I had steam coming out of my ears.

To literally emit steam from your ears, like a cartoon character.

To be extremely angry.

To feel tired and sleepy.

I don’t know the meaning of this idiom.

The motivations behind the meaning of idioms.

What helped you understand the meaning of idioms?

The literal meaning of the idiom.

The training we had on CMT and EMBODIMENT.

The context of the idiom.

Which idioms were easier to understand?

Idioms with training on CMT and EMBODIMENT.

Idioms without training on CMT and EMBODIMENT.

Do you agree that EMBODIMENT and CMT helped you activate the meaning of the idiom?

Yes, I strongly agree.

I partially agree.

No, I don’t agree.

Thank you for your contribution.

Appendix C. Idioms Corpus

Idiom |

Citation |

|---|---|

| cold feet | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 58) |

| blood boil | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 29) |

| blow off steam | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 30) |

| lost his cool | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 80) |

| butterflies in the stomach | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 55) |

| blood ran cold | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 40) |

| hanging his head | The Free Dictionary. (n.d.). Hang head. In The Free Dictionary. Retrieved from https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/hang+head |

| bored to tears | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 46) |

| down in the mouth | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 84) |

| sick at heart | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 350) |

| save face | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 100) |

| curl my hair | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 169) |

| carrying the world’s weight on his shoulders | The Free Dictionary. (n.d.). Carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. In The Free Dictionary. Retrieved from https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/carrying+the+weight+of+the+world+on+his+shoulders |

| seeing red | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 240) |

| bite the bullet | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 26) |

| feeling blue | The Free Dictionary. (n.d.). Feeling blue. In The Free Dictionary. Retrieved from https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/feeling+blue |

| under my skin | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 355) |

| got bent out of shape | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 22) |

| foaming at the mouth | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 143) |

| I was pulling my hair out | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 288) |

| After the good news, I felt like I was walking on air. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 4) |

| The kids were jumping up and down when their mother told them about going on a picnic. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 158) |

| She was so frustrated; I thought she might burst a blood-vessel. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 39) |

| After that workout, I could really feel the burn. | The Free Dictionary. (n.d.). Feel the burn. In The Free Dictionary. Retrieved from https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/feel+the+burn |

| She was worried she might lose face if she didn’t perform well. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 124) |

| The coach was breathing fire after the team’s poor performance. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 137) |

| He still carries a torch for his ex-girlfriend. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 399) |

| Your dog is getting on my nerves. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 198) |

| I went weak at the knees. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 418) |

| My heart sank when I saw the bad grade on my paper. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 184) |

| She left with a heavy heart after the farewell party. | Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). A heavy heart. In Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/a-heavy-heart |

| After months of trying, he decided to throw in the towel. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 291) |

| The track’s horn made me jump out of my skin. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 355) |

| He was tickled pink when he received the surprise gift. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 292) |

| Tom was up in arms after finding that his little brother spoiled his book. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 9) |

| She shakes like a leaf when she watches a horror movie. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 222) |

| He was hopping mad because his sister ate his cookies. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. 198) |

| Finishing the project was a weight off my shoulders/my mind. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 309) |

| Jane was pulling her hair out trying to solve that complicated math problem. | Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms (1998, p. x) |

| After the long meeting with so many interruptions, I felt like had steam coming out of my ears. | The Oxford Dictionary of Idioms (2004, p. 276) |

References

Agus, Cahyono. 2013. Conceptual metaphor related to emotion. Jurnal Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra 13(2). 204–211. https://doi.org/10.17509/bs_jpbsp.v13i2.292 (accessed 1 March 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, Mona. 1992. A coursebook on translation. London & New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Barrett, Lisa Feldman & Kristen A. Lindquist. 2008. The embodiment of emotion. In Gün R. Semin & Eliot R. Smith (eds.), Embodied grounding, 237–262. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805837.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Barsalou, Lawrence W. 2008. Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology 59. 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639.10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639Suche in Google Scholar

Boers, Frank & Seth Lindstromberg. Optimizing a lexical approach to instructed second language acquisition. Dordrecht: Springer.Suche in Google Scholar

Byram, Michael. 1997. Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800410251.Suche in Google Scholar

Cameron, Lynne & Graham Low. 1999. Researching and applying metaphor: From discourse to cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524704.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Cameron, Lynne. 2003. Metaphor in educational discourse. The Journal of Educational Research 97(3). 132–142. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474212076.Suche in Google Scholar

Cheng, Yuh-show. 2016. The relationship between metaphor awareness and vocabulary acquisition among EFL students. Taiwan Journal of Linguistics 14(1). 1–25.Suche in Google Scholar

Cooper, Thomas C. 1999. Processing of idioms by L2 learners of English. TESOL Quarterly 33(2). 233–262. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587719.Suche in Google Scholar

Cronk, Brian C. & William A. Schweigert. 1992. The comprehension of idioms: The effects of familiarity, literalness, and usage. Applied Psycholinguistics 13(2). 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400005531.Suche in Google Scholar

De Wilde, Vanessa, Marc Brysbaert & June Eyckmans. 2019. Learning English through out-of-school exposure: Which levels of language proficiency are attained and which types of input are important? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22(1). 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918001062.Suche in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2007. Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

El Yamani, Abdelaaziz, Hassane Darir & Azeddine Rhazi. 2025. Navigating body-part idioms: Conceptual translation strategies in English and Arabic. FORUM. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.24008.ely.Suche in Google Scholar

Farina, Mirko. 2021. Embodied cognition: Dimensions, domains, and applications. Adaptive Behavior 29(1). 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059712320912963.Suche in Google Scholar

Foglia, Lucia & Robert A. Wilson. 2013. Embodied cognition. WIREs Cognitive Science 4(3). 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1226.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W. 1994. The poetics of mind: Figurative thought, language, and understanding. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-44501997000200009.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W. 2005. Embodiment and cognitive science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805844.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W. 2017. Embodiment. In Barbara Dancygier (ed.), The Cambridge handbook of cognitive linguistics, 449–462. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316339732.028.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W. & Nandini P. Nayak. 1991. Why idioms mean what they do. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 120(1). 93–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.120.1.93.Suche in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W. & Ana Cristina Silva de Macedo. 2010. Metaphor and embodied cognition. DELTA: Documentation of Studies in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics 26(3). 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-44502010000300014.Suche in Google Scholar

Glenberg, Arthur M. 2010. How the body shapes the mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Grant, Lynn & Laurie Bauer. 2004. Criteria for re-defining idioms: Are we barking up the wrong tree? Applied Linguistics 25(1). 38–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/25.1.38.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, Mark. 2018. The embodiment of language. In Albert Newen, Leon De Bruin & Shaun Gallagher (eds.), The Oxford handbook of 4E cognition, 623–639. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198735410.013.33.Suche in Google Scholar

Kondaiah, K. 2004. Metaphorical systems and their implications to teaching English as a foreign language. Asian EFL Journal 6(1). 42–57.Suche in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2002. Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404503254051.Suche in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire. 1993. Context and culture in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George. 1993. The contemporary theory of metaphor. In Andrew Ortony (ed.), Metaphor and thought, 202–251. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173865.013.Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of cognitive grammar: Vol. I. Theoretical perspectives. Stanford: Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008413100021265.Suche in Google Scholar

Langlotz, Andreas. 2006. Idiomatic creativity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/hcp.17.Suche in Google Scholar