Abstract

Sodium-ion batteries are increasingly regarded as a sustainable alternative to lithium-ion technology for large-scale energy storage, but their development remains limited by the lack of durable high-energy cathodes. Among the most promising candidates, P2–Mn-based layered oxides combine high theoretical capacity with structural versatility, yet their performance is constrained by two degradation pathways: (i) the irreversible participation of lattice oxygen in the redox process and (ii) voltage-driven solid-state phase transitions. This research article synthesizes our recent ab initio investigations aimed at disentangling the atomistic origins of these processes occurring in the high-voltage regime. We show that Mn deficiency activates oxygen redox but also promotes O2 release, whereas Fe and Ru doping strengthen TM–O covalency, enabling reversible anionic redox. In parallel, we identify cooperative Jahn–Teller distortions and Na+/vacancy reorganization as the driving forces of high-voltage phase transitions and propose simple geometric descriptors as predictive tools for structural stability. Together, these insights help to establish quantum-based design guidelines for layered sodium cathodes: reinforce TM–O covalency, suppress oxygen evolution, and mitigate phase instabilities. By combining first-principles modeling with targeted compositional design, we pave the way toward the accelerated discovery of sustainable, cobalt-free, and high-energy cathodes for next-generation sodium-ion batteries.

Introduction

Since the advent of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), enormous efforts have been devoted to the development of alternative electrochemical energy storage technologies capable of supporting the global energy transition. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Among the available options, sodium-ion batteries (NIBs) are increasingly recognized as a promising candidate, owing to the abundance and low cost of sodium, coupled with electrochemical principles analogous to those of LIBs. 6 , 7 , 8 NIB potential spans from stationary grid-scale applications integrated with renewable energy plants to next-generation heavy-duty electric transportation. 9 , 10 Furthermore, the development of all-solid-state NIBs has the potential to meet stringent requirements of safety, scalability, and cost-effectiveness. 11 , 12

From a materials design standpoint, achieving high energy density requires coupling low-potential anodes with high-voltage cathodes. 13 , 14 However, sodium analogues of LIB electrodes often suffer from lower intercalation potentials, sluggish kinetics, and structural instabilities associated with the larger Na+ ionic radius. 8 , 15 While substantial progress has been achieved on the anode side, from hard carbons to alloys, titanates, and low-dimensional heterostructures, 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 the cathode remains the most critical bottleneck for enabling high-energy NIBs.

Among cathode candidates, layered transition-metal oxides (NaxTMO2) are the most intensively investigated. 21 , 22 , 23 Their structural analogy with LiTMO2, already commercialized in LIBs, has accelerated their development. The Delmas notation is commonly used to classify NaxTMO2, which distinguishes between prismatic (“P”) and octahedral (“O”) coordination of Na+ ions and specifies the number of transition-metal layers per unit cell. 24 , 25 Among the different polymorphs, the P2 and O3 phases are the most relevant for sodium storage. 23 In particular, P2-type manganese-based layered oxides have emerged as highly attractive cathodes, as they combine large prismatic diffusion channels that enable rapid Na+ transport, high theoretical capacities exceeding 200 mAh g−1, and relatively good cycling stability. 15 Moreover, manganese is abundant, inexpensive, and environmentally benign, making these compounds especially appealing for sustainable, large-scale applications. 23 , 26 , 27

Despite these advantages, the practical deployment of P2–Mn-based layered oxides remains limited by structural instabilities and degradation at high voltages. Two phenomena are especially detrimental: (i) the irreversible participation of lattice oxygen in the redox process and (ii) solid-state phase transitions. 23 , 28 , 29 , 30 Unlike Li-based analogues, Na-layered oxides exhibit pronounced structural rearrangements such as the P2 to O2, the P2 to OP4, or the P2 to P2′ transitions, which involve TM–O layer gliding and lattice volume variations exceeding 20 %. 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 In particular, in P2-NaxMnO2 (NMO), desodiation induces a P2 → OP4 transition, where sodium occupies prismatic sites in one layer and octahedral sites in the next (Fig. 1a). 34 In P2-NaxNi0.25Mn0.75O2 (NNMO), Ni incorporation extends the electrochemical window and activates anionic redox processes at high potentials. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 However, the system still undergoes a P2 → O2 transition at ∼4.1 V (Fig. 1b). 40 , 41 Such processes result in capacity fading, voltage hysteresis, and mechanical degradation. Although these instabilities can be partially mitigated through compositional design, for example via alkali or selected TM doping, 33 , 42 the underlying mechanisms remain under debate, and simple, predictive descriptors are still lacking. 23

Schematic diagrams of (a) NMO and (b) NNMO phase evolution during battery operation. View along the y axis. Atoms are represented as spheres, and TMO6 octahedra as polyhedra. Color code: Na, yellow; Mn, violet; O, red; Ni, gray. Reproduced from Langella et al. 43 Copyright 2025 American Chemical Society.

In this context, our recent investigations have provided new insights into the electronic and structural mechanisms governing oxygen redox and phase stability in P2–Mn-based layered oxides. We first examined the prototypical NMO, systematically exploring its charge-compensation mechanisms at different states of charge. Our calculations revealed that its intrinsic instabilities originate from the cooperative Jahn–Teller distortions of Mn3+ centers, coupled with sodium reorganization at high degrees of desodiation, which together drive detrimental structural transformations. 43 Building on this understanding, we investigated the effect of Ni substitution, focusing on Mn-deficient NNMO as a representative composition. 35

The introduction of Ni improves electrochemical performance, but does not suppress oxygen release at high voltages, thereby highlighting the delicate balance between capacity enhancement and structural degradation. 35 We further demonstrated that Fe and Ru doping enhances TM–O covalency and suppresses oxygen loss, enabling reversible oxygen redox and improved capacity retention. 44 , 45 Finally, we revealed that phase transitions in NMO and NNMO can be rationalized using simple geometric descriptors, opening the way to predictive rules for phase stability. 46

Although our analysis focuses on P2–Mn-based layered oxides for NIBs, several insights extend across chemistries. In Li-rich layered oxides, the coupling between TM–O covalency and anionic redox, as well as the management of O–O dimerization, has been extensively discussed and experimentally probed. 30 , 47 , 48 , 49 Polyanionic cathodes such as NASICON and phosphate frameworks offer a complementary design space, where strong inductive effects stabilize high voltages while mitigating oxygen activity. 50 , 51 , 52 These broader perspectives motivate the methodology adopted here and highlight the potential of our descriptors as transferable design handles beyond P2 oxides.

This research article synthesizes our recent findings into a unified framework, providing a perspective on digital design guidelines for P2–Mn-based layered oxide cathodes in the high-voltage regime, where first-principles modeling, informed by structural and electronic descriptors, provides actionable insights to stabilize high-energy phases, enable reversible oxygen redox, and accelerate the discovery of sustainable and efficient cathode materials for next-generation sodium-ion batteries.

Methods and computational details

First-principles calculations for P2-NMO, NNMO, NFNMO, NRNMO, and their Mn-deficient analogues were performed using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP). 53 , 54 , 55 Structure optimizations were carried out within spin-polarized generalized gradient approximation (GGA), employing the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional. 56

The choice of PBE is motivated by its widespread use and well-documented reliability in modeling transition-metal oxides for battery applications. 47 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 However, for mid-to-late 3d metals, localized d electrons are poorly described at the GGA level due to self-interaction error. To correct this limitation, we adopted the DFT+U approach with an effective on-site correction parameter (U−J)eff = 4.0 eV applied to the Mn, Ni, Fe and Ru d shells. 21 , 45 , 46 , 51 This scheme is the current standard for layered systems, 45 , 60 , 61 and has been benchmarked against hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06), consistently showing good agreement while offering a much more favorable accuracy-to-cost ratio. 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 Layered cathodes are also strongly influenced by dispersive interactions between adjacent TM–O layers. Semi-local functionals alone fail to capture this physics, leading to unrealistic interlayer spacing. We therefore employed the DFT-D3 correction with Becke–Johnson (BJ) damping, which has been demonstrated to accurately reproduce van der Waals interactions in layered materials, including graphite, MoS2, and layered oxides. 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 The adoption of DFT-D3(BJ) is thus both motivated by previous benchmarking studies and required for a faithful description of structural energetics.

A plane-wave energy cutoff of 750 eV and a 4 × 4 × 4 k-points grid based on the Monkhorst–Pack scheme were adopted, as determined from convergence tests. 76 Electronic self-consistency convergence criteria for electronic minimization and ionic forces were set at 10−5 eV and 10−3 eV Å−1, respectively.

Structural models of all P2-type Mn-based materials were constructed in the P63/mmc space group using 4 × 4 × 1 supercells, containing 100–120 atoms depending on the sodium content (xNa). Configurational disorder of Na/vacancy distributions and TM mixing in the transition-metal layers were modeled using the special quasi-random structure (SQS) approach implemented in the SQSgen code. 77 , 78 Mn-deficient systems were generated by introducing two Mn vacancies per supercell, arranged in the most homogeneous configuration to avoid artificial clustering. Electrochemical cycling was emulated by gradually removing Na atoms at each stoichiometry step, allowing us to track the structural and electronic evolution during charge.

All the electronic structure calculations and geometry optimizations for O-defective and O2-intermediate structures followed the same computational protocol. Atomic magnetic moments were extracted from collinear spin calculations in VASP, obtained as the integrated difference between spin-up and spin-down channels within default Wigner–Seitz spheres. Geometrical parameters, including bond lengths and angular distortions, were analyzed using the Van Vleck calculator. 79 Phase transition pathways (P2-to-P2′ and P2-to-OP4/O2) in NMO and NNMO were obtained using the pmpath tool in the modified version developed by Samtsevich. 80 √3 × 2 × 1 supercells for NMO and 2√3 × 4 × 1 were employed to capture sodium ordering at lower contents; for direct comparisons, the larger 2√3 × 4 × 1 supercell was consistently used. 46 Transition barriers were evaluated using the variable-cell nudged elastic band (VC-NEB) method, 81 interfaced with USPEX, 82 adopting the same convergence parameters as in the structural relaxations.

Discussion

This Perspective focuses specifically on the high-voltage regime, where degradation phenomena are most pronounced and yet most critical for achieving durable high-energy cathodes for NIBs. The discussion follows a logical progression centered on high-voltage processes: starting from the prototypical NMO and its structural and electronic evolution during the charge process, moving to the Ni-doped system designed to enhance capacity, then addressing Fe- and Ru-substituted systems to enable reversible anionic redox, and finally exploring the kinetics of phase transitions. By combining structural, electronic, and thermodynamic analyses, we track how these properties evolve upon desodiation and highlight how targeted compositional tuning can mitigate degradation mechanisms under high-voltage operation.

NaxMnO2: structural and electronic evolution

To gain fundamental insights into the behavior of Mn-based layered oxides, we first examined the prototypical P2-NMO system across representative states of charge (0.72 ≥ xNa ≥ 0.34). The calculated lattice constants reproduced experimental values with excellent accuracy, validating the reliability of our description of phase stability. 34 Consistent with experimental observations, the P2 structure was found to be the most stable configuration in the intermediate regime (0.47 ≤ xNa ≤ 0.59), while the OP4 and P2′ polymorphs became thermodynamically favored at high (xNa = 0.34) and low (xNa = 0.72) sodium contents, respectively. 43

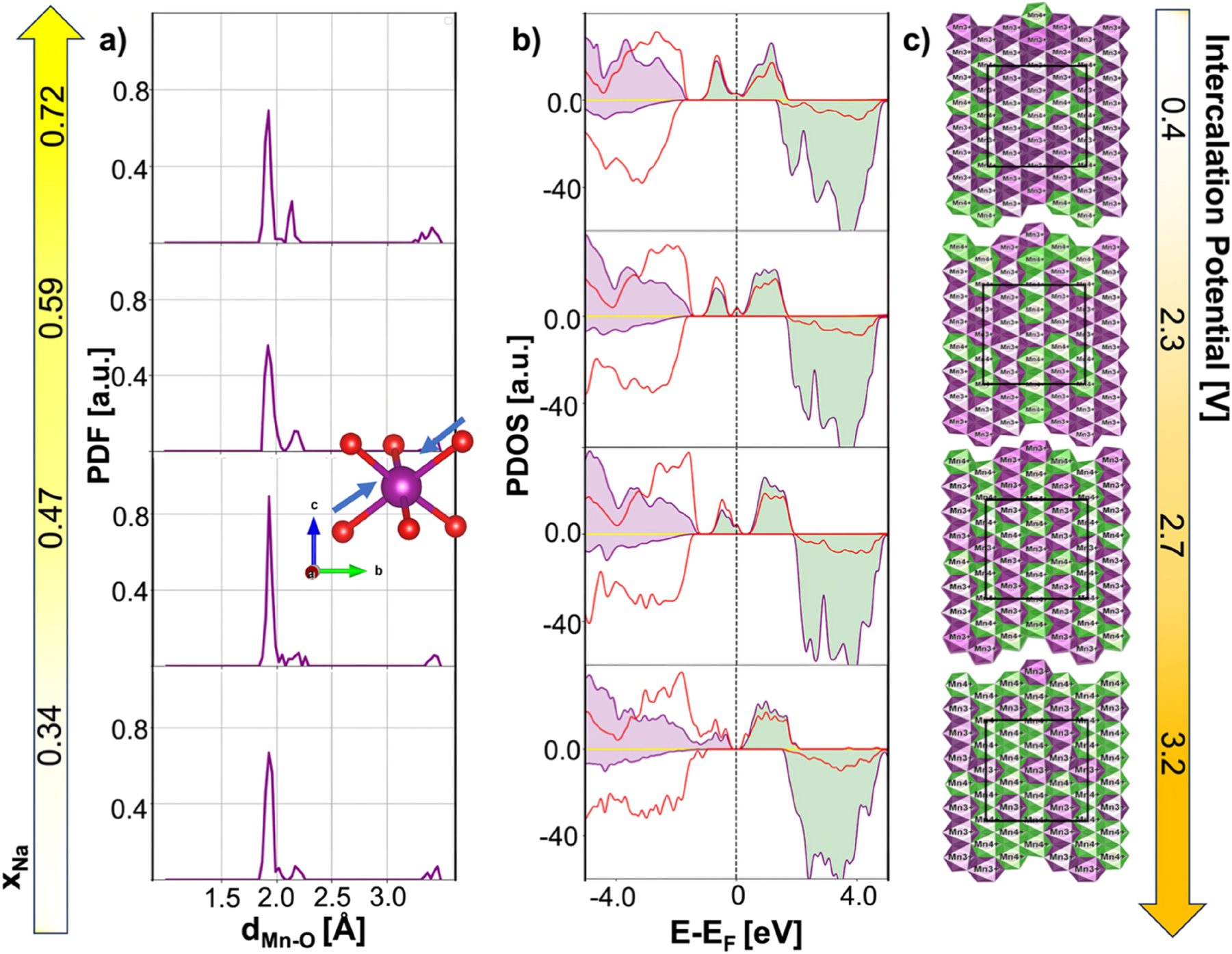

Analysis of the Mn–O pair distribution functions (Fig. 2a) revealed pronounced distortions of MnO6 octahedra upon desodiation. At high Na content (xNa = 0.72), two distinct Mn–O bond lengths were observed (∼1.9 Å and ∼2.2 Å), indicative of Jahn–Teller (JT) distortions associated with Mn3+ centers. 43 Progressive extraction of Na+ reduced the long Mn–O distances, signaling the oxidation of Mn3+ to Mn4+. The projected density of states (PDOS) (Fig. 2b) further confirmed this behavior: the characteristic splitting of Mn e g orbitals (green bands) gradually disappeared as the Mn3+ fraction decreased, thus reducing the Jahn–Teller activity. 83 , 84 Crucially, JT-related distortions were not confined to local octahedra, but propagated cooperatively across the lattice, evidencing the presence of a cooperative Jahn–Teller effect (CJTE). 83 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 As reported in Fig. 2c, at intermediate sodiation (xNa = 0.47), Mn3+/Mn4+ ordering adopted a zig-zag arrangement in the ab plane, which minimized the overall distortion and stabilized the P2 phase. In contrast, at higher and lower Na contents (xNa = 0.72 and xNa = 0.34), this cooperative arrangement was lost, giving rise to local distortions and facilitating gliding-driven transitions toward P2′ or OP4 phases. This “exotic” cation ordering in the ab-plane thus represents a direct fingerprint of the cooperative Jahn–Teller effect, as widely discussed in the literature. 86 , 87 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92

Structural and electronic evolution. (a) Pair distribution functions (PDFs) of Mn–O distances in NMO at different Na contents. The inset highlights the axial Mn–O compression. (b) Atom-, angular momentum-, and spin-projected density of states (PDOS) as a function of xNa for NMO computed at the PBE+U-D3(BJ) level of theory. Colour code: Na s states, yellow; Mn t2g and eg bands, violet and green, respectively; O p states, red. (c) Geometrical distributions of Mn3+ and Mn4+ in the a–b plane of NMO lattice. The periodic replica images are displayed for a more comprehensive visualization, while O and Na atoms are removed for clarity. Colour code: Mn3+-centered octahedra, violet; Mn4+-centered octahedra, green. Voltage values are reported for each composition, derived from the calculated intercalation potentials plotted in the capacity-voltage curve. 44 Reproduced from Langella et al. 44 Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society.

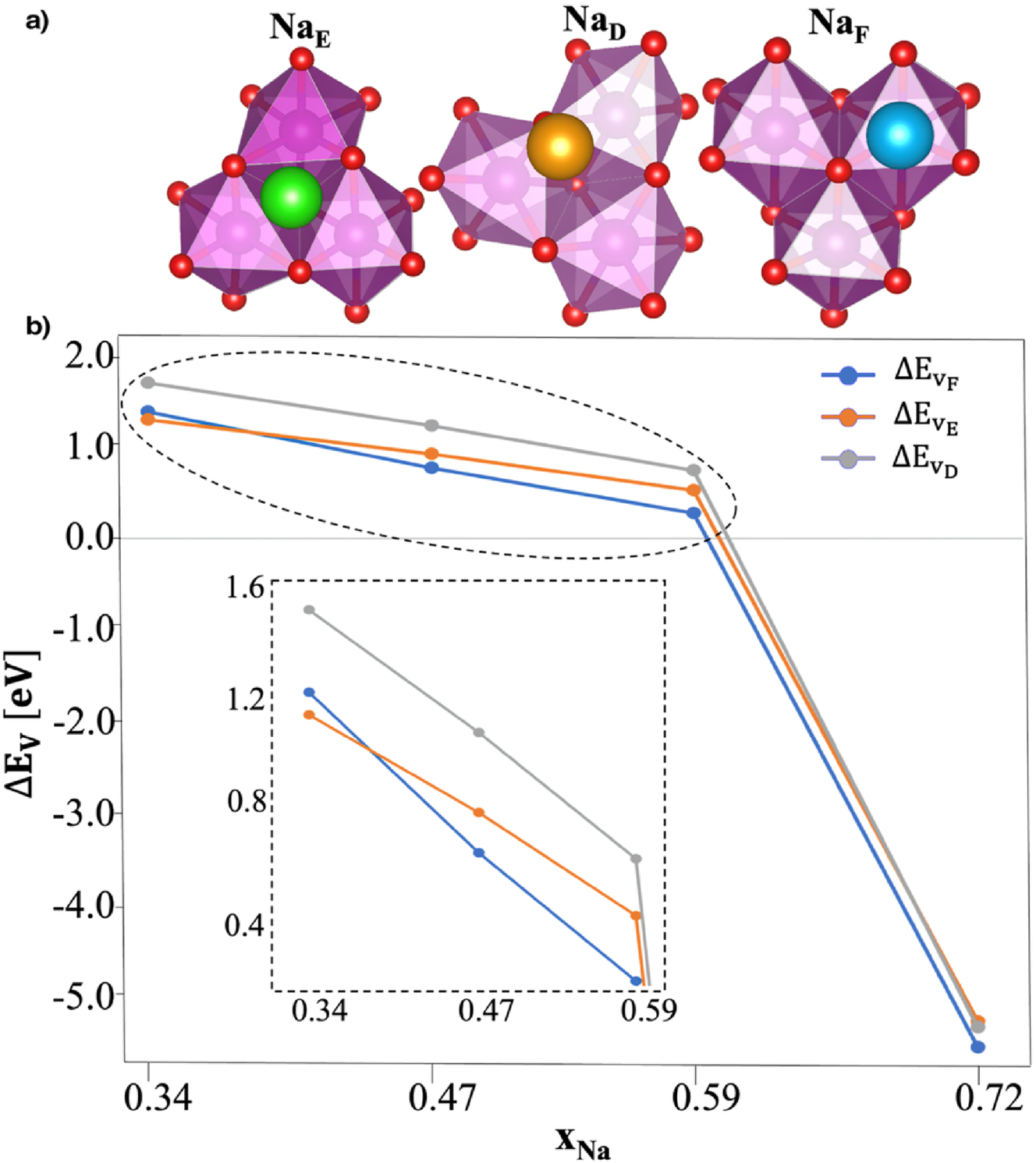

In parallel, Na+ rearrangement was found to play a pivotal role in driving structural transitions. The P2 → OP4 transition requires prismatic Na sites to evolve into octahedral ones. Upon desodiation, Na+ ions located at face-sharing sites (NaF) were found in pseudo-octahedral displaced positions (NaD) (Fig. 3a). To assess the relative stability of all the Na sites (Fig. 3a), we computed the sodium vacancy formation energy at each xNa as:

where

Analysis of sodium displacements within NMO structures: (a) top views of different Na crystallographic sites in the PBE+U-D3(BJ) minimum-energy structures. Na atoms in green, orange, and blue show edge, displaced and face sites, respectively. (b) Sodium vacancy formation energies, ΔEv, calculated according to eq. 1 for all the possible sites occupied in NMO and reported as a function of xNa. Reproduced from Langella et al. 35 Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society.

Taken together, these results highlight that the structural evolution of NMO is dictated by the delicate interplay of three factors: (i) Jahn–Teller distortions of Mn3+, (ii) long-range cooperative effects, and (iii) Na+ ordering. These insights provide an atomistic rationale for the poor cycling stability of pristine NMO and point to compositional tuning (via aliovalent doping or Na-site substitution) as essential strategy to suppress gliding-driven transitions and unlock its potential as a viable high-energy cathode material. 28 , 85

NaxNi0.25Mn0.68O2: reversible AR vs. O2 release

One of the main strategies to enhance the capacity of P2-NMO is partial substitution of Mn with Ni, since the multiple Ni2+/Ni3+/Ni4+ redox couples provide access to higher capacities. 95 Among these systems, P2-type Mn-deficient cathodes have attracted considerable attention due to their high reversible capacity and promising rate capability. However, spectroscopic investigations (i.e., EXAFS) consistently indicate oxygen loss at high voltage, evidenced by radial gradients in transition-metal oxidation states after cycling. 38 To clarify the atomistic origin of this behavior, we investigated NaxNi0.25Mn0.68O2 (Mn-deficient NNMO) across representative states of charge (0.125 ≤ xNa ≤ 0.75). For clarity and consistency, only the Mn-deficient system is here reported.

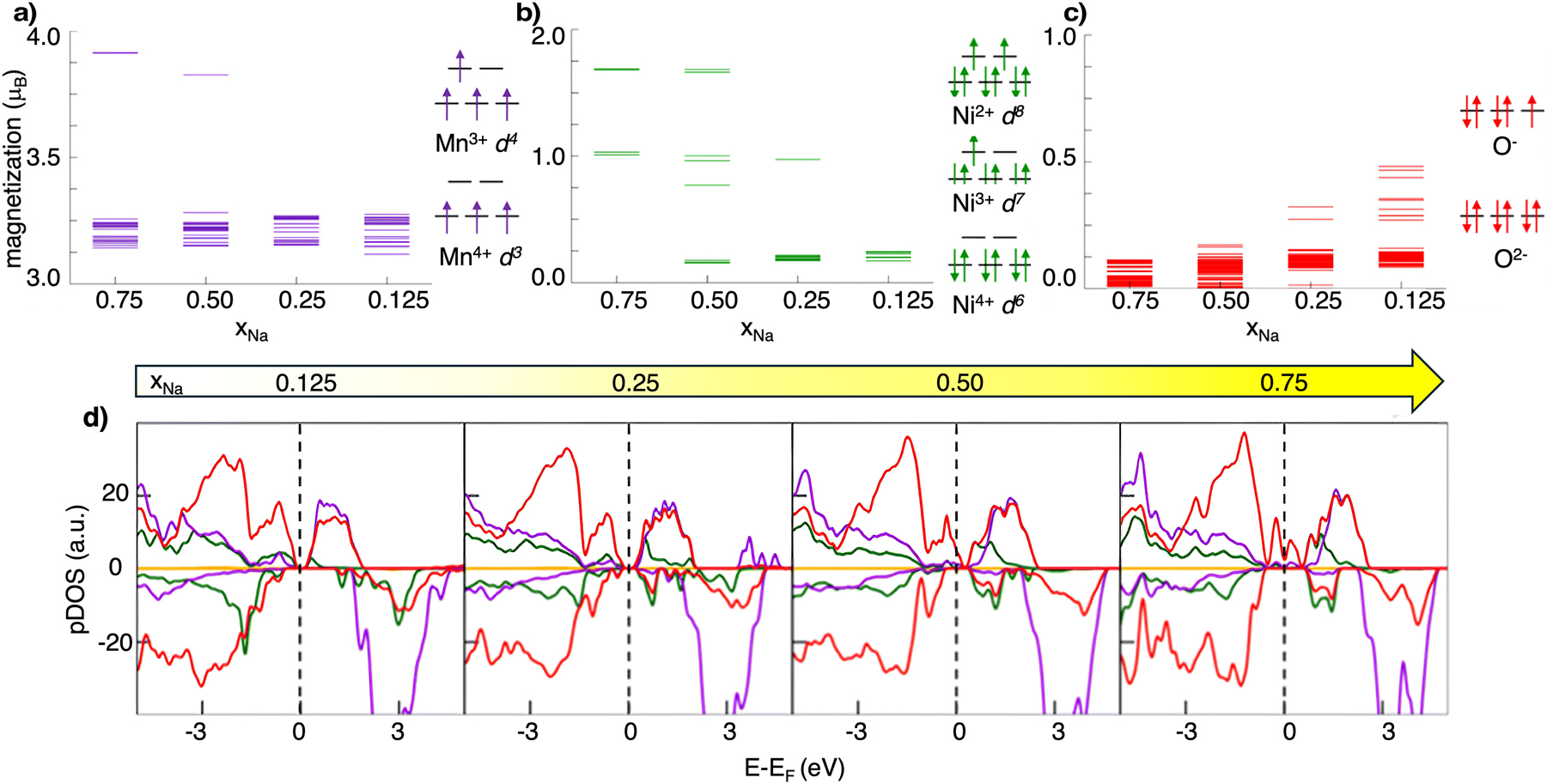

Electronic-structure analysis reveals that, upon desodiation, Mn remains essentially in the Mn4+ state (Fig. 4a), while charge compensation is primarily carried by Ni, which undergoes progressive Ni2+ → Ni3+ → Ni4+ oxidation (Fig. 4b). It thus becomes evident that Ni substitution reduces the presence of Mn3+, and, as we will discuss in the final section, the Ni/Mn ratio can be optimized to mitigate structural instabilities. At deep desodiation, the increase in magnetization on oxygen sites (Fig. 4c), together with the partial crossing of O 2p states at the Fermi level observed in the PDOS (Fig. 4d), clearly signal the onset of lattice oxygen redox. While oxygen participation in charge compensation is thus well established, its reversibility remains the critical challenge.

Electronic structure analysis of NaxNi0.25Mn0.68O2 as a function of xNa: net magnetic moments on Mn (a), Ni (b), and O (c) with the corresponding electronic configuration on the side; (d) atom-, angular momentum-, and spin-pDOS computed at the PBE+U(-D3BJ) level of theory; colour code: Na s states, yellow; Mn d states, purple; Ni d states, green; O p states, red. Reproduced from Massaro et al. 35 Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

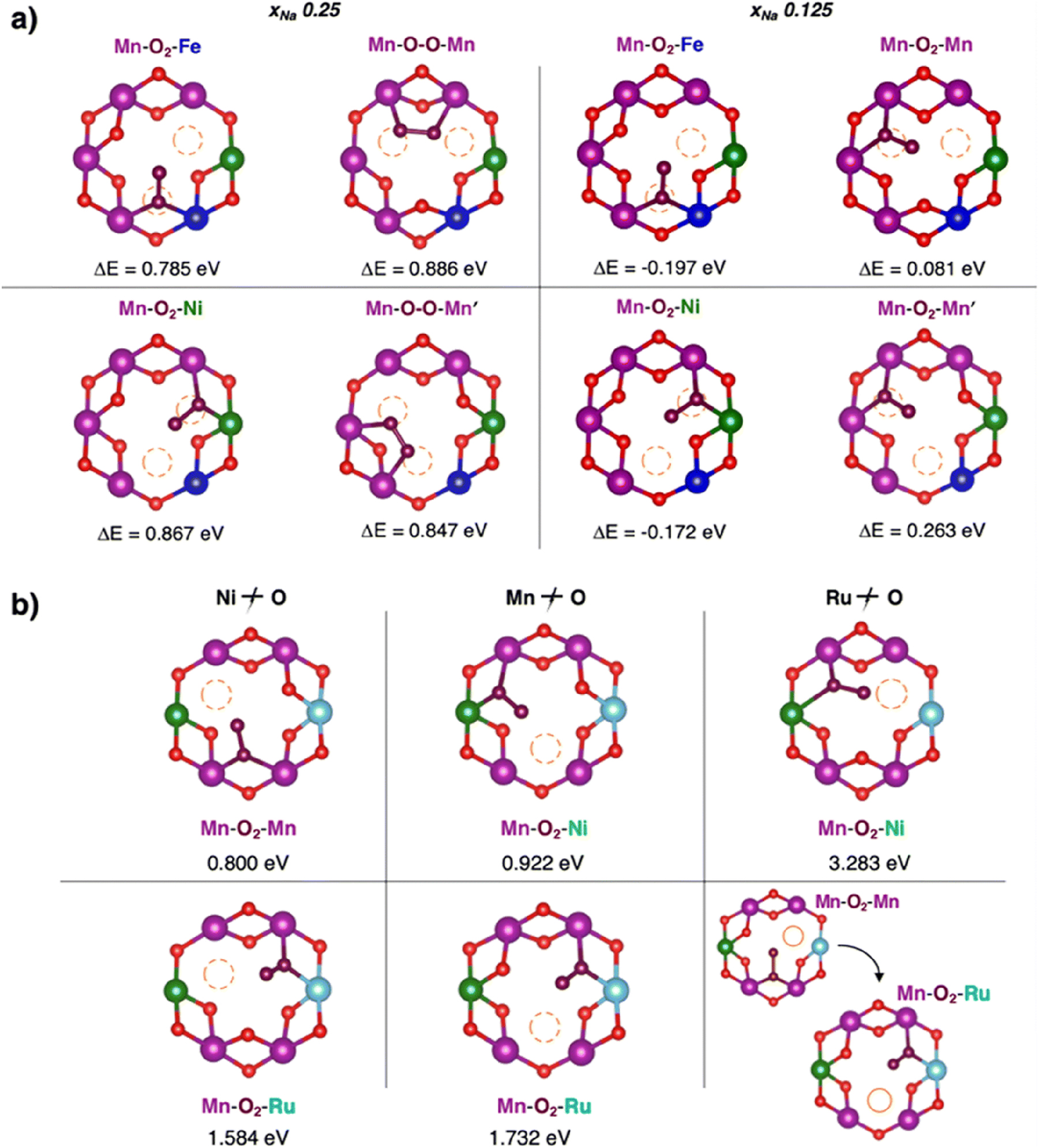

Oxygen redox in layered oxides is often coupled to dimerization reactions, which have been widely reported both experimentally and computationally. 21 , 29 , 35 , 93 , 96 Stabilizing such oxygen dimers is crucial for ensuring reversibility, and this can be achieved through increased TM–O covalency via targeted substitutions. 35 , 48 , 95 To investigate this process in Mn-deficient NNMO, we computed the formation energy of dioxygen intermediates bound to neighboring transition-metal cations:

where

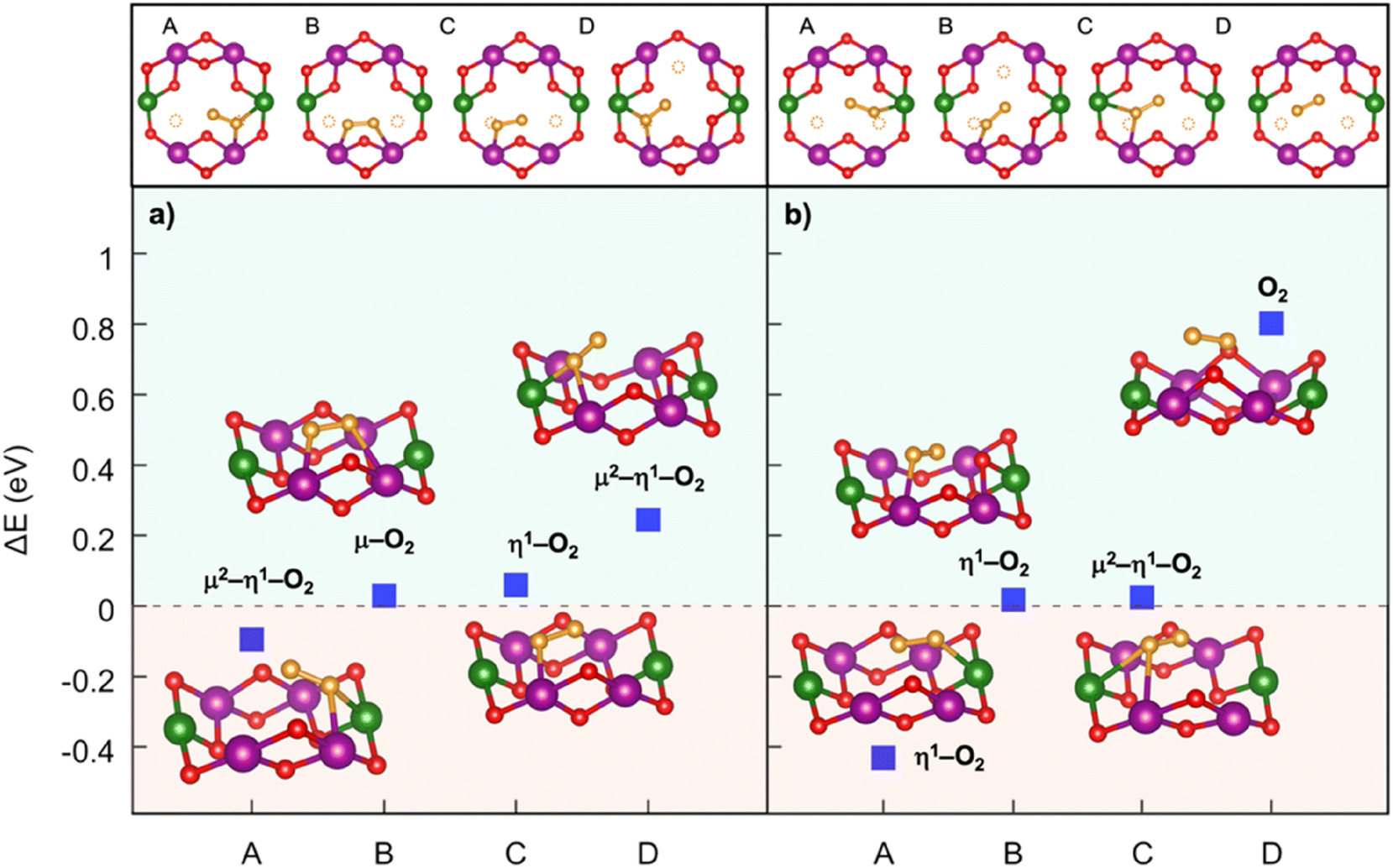

Dioxygen formation in Mn-deficient NNMO: (top) top-view of A–D structures and (bottom) dioxygen formation energetics identified at (a) xNa = 0.25 and (b) xNa = 0.125. Colour code: Ni, green; Mn, violet; O (lattice position), red; O (dioxygen position), orange; the yellow circles highlight the initial positions before dioxygen formation. Only atoms around the dioxygen complex are shown for clarity. Reproduced from Massaro et al. 35 Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

NaxFe0.125Ni0.125Mn0.68O2 and NaxRu0.125Ni0.125Mn0.68O2: highly covalent TM–O networks

Drawing inspiration from Li-rich analogues where high TM–O covalency correlates with reversible anionic redox and suppressed dimerization, we investigated Fe and Ru doping as a strategy to enhance TM–O bond covalency and stabilize oxygen redox in Mn-deficient NNMO. 99 , 100 , 101 Specifically, we explored NaxFe0.125Ni0.125Mn0.68O2 (NFNMO) NaxRu0.125Ni0.125Mn0.68O2 (NRNMO) across various states of charge xNa. While the electronic-structure fingerprints of anionic redox are well established, here we focus on how doping alters the fate of oxygen dimers and suppresses irreversible O2 release. 44 , 45 Mapping dioxygen intermediates according to eq. 2 near Mn vacancies reveals that all stabilized species are superoxides (dO–O ≈ 1.26–1.37 Å) in either bridging or binuclear geometries, with formation energies that decrease as xNa decreases.

In Fe-doped systems (Fig. 6a), Mn–O2–Fe environments are energetically favored at xNa = 0.125, yielding a particularly stable superoxide (ΔE ≈ −0.20 eV) formed by breaking a Ni–O bond. Crucially, free O2 is not stabilized, indicating that Fe doping effectively pins the O–O dimer in a reversible superoxide form and raises the barrier to molecular oxygen evolution. This mechanism explains experimental reports of enhanced and reversible capacities in Fe-doped NNMO without detectable O2 release, while simultaneously meeting low-cost and sustainability requirements.

Formation of dioxygen species in the Mn-deficient site of (a) NFNMO and (b) NRNMO. Corresponding formation energy, ΔE, computed according to eq. 2 at PBE+U(-D3BJ) are also reported. Colour code: O atoms at dioxygen positions are depicted in brown, Fe in blue and Ru in cyan. Reproduced from Massaro et al. 45 Copyright ©2000–2022 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 134 and from Massaro et al. 44 Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

Ru doping exerts a complementary effect (Fig. 6b). In NRNMO, all stabilized intermediates are again superoxides (dO–O ≈ 1.28–1.32 Å), but their formation energies are substantially higher than in NNMO or NFNMO, particularly when Ru–O bonds would be broken or when the dioxygen binds directly to Ru. No free O2 is stabilized. This behavior is consistent with the stronger covalency of Ru–O bonds, which disfavors O–O dimerization and suppresses oxygen release. Notably, in Li-rich systems, Ru has been shown to enable reversible oxygen redox through robust O–O coupling mechanisms; here, Ru similarly prevents O2 evolution in the Na framework by strengthening the TM–O network. 102 , 103 , 104

The covalency-based rationale we establish for stabilizing oxygen redox in Mn-rich P2 oxides echoes the trends reported in Li-rich layered systems, where increasing TM–O overlap correlates with reversibility of O-redox and suppressed O2 evolution. 101 , 102 In contrast, polyanionic frameworks such as phosphates and NASICONs rely on strong inductive effects from the polyanion groups, which elevate redox potentials while inherently suppressing lattice-oxygen participation by stabilizing the anion sublattice. 105 These cross-chemistry parallels help to position our “digital design toolbox” within a broader context and highlight where each descriptor is most predictive.

Taken together, Fe and Ru dopings illustrate two complementary stabilization routes: Fe lowers the energy cost of forming superoxides while preventing O2 release, enabling reversible oxygen redox; Ru strengthens TM–O bonds and suppresses dimerization altogether. Both approaches demonstrate that introducing mild modifications to TM–O covalency can decouple capacity enhancement from structural degradation. In this way, anionic redox not only delivers additional capacity but can also be recovered over cycling, since O2 evolution is effectively mitigated. Finally, Massaro et al. have further shown that oxygen-vacancy formation energy (EVO) provides a simple yet powerful energetic descriptor of TM–O bond lability and, by extension, of a composition’s propensity for O2− oxidation and O2 evolution. 93 This parameter, easily accessible from first-principles, offers a predictive framework to rationalize and guide compositional design strategies.

Solid-state phase transitions: mechanisms, barriers, and descriptors

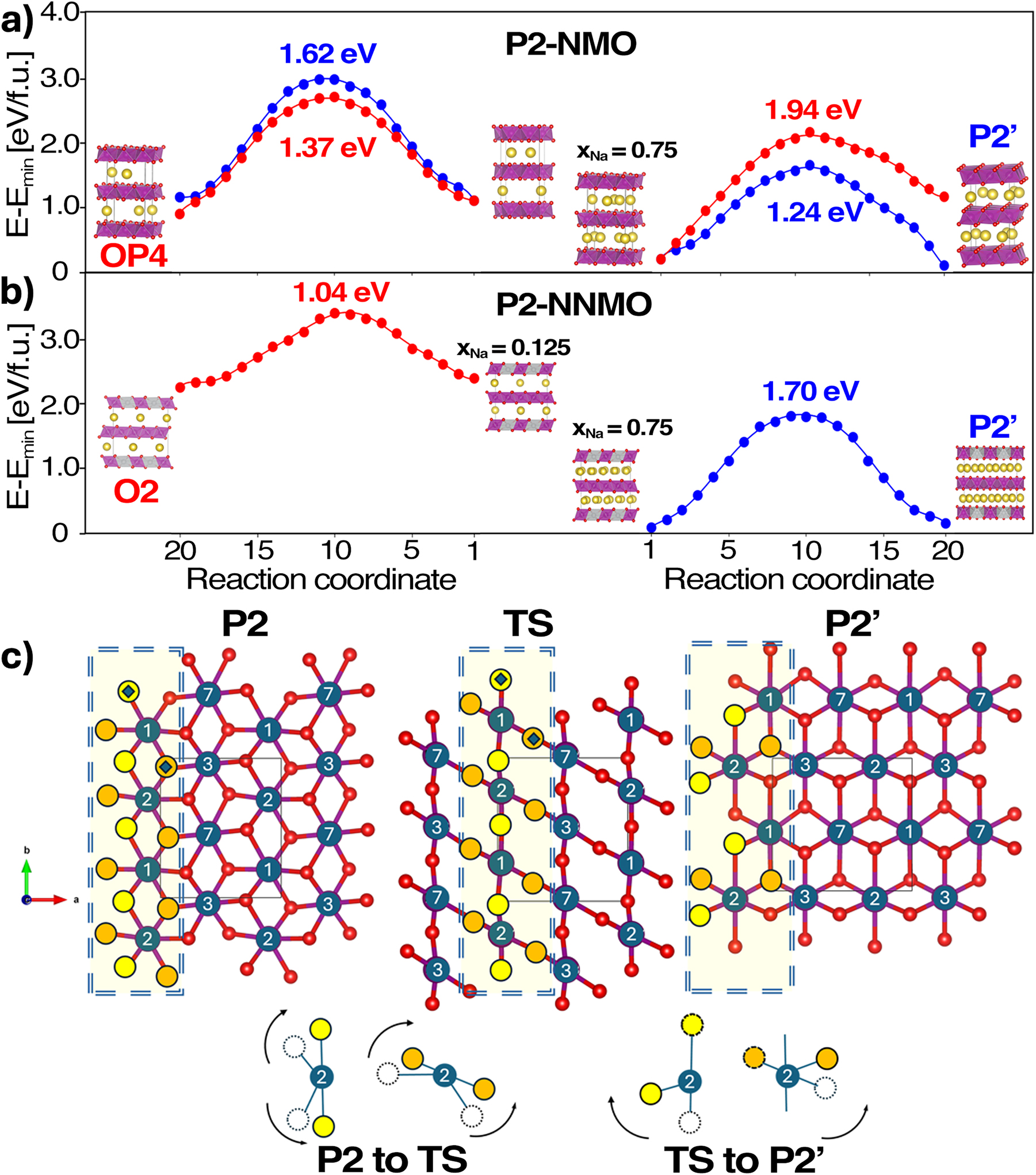

Another critical aspect in modeling P2–Mn-based cathodes at high voltage is the detrimental P–O glide. To unravel the structural degradation induced by phase transitions, we mapped the minimum-energy paths for the key P2 → P2′ and P2 → OP4/O2 (hereafter P2 → O) transformations in NMO and NNMO using the variable-cell nudged elastic band (VC-NEB) method. 81

As shown in Fig. 6, VC-NEB quantifies how state of charge (SoC) and doping bias the competition between pathways. For NMO (Fig. 7a), the P2 → P2′ transition is kinetically favored at high Na content (xNa ≈ 0.75), whereas the P2 → O transition dominates at low Na (xNa ≈ 0.375). In NNMO (Fig. 7b), the P2 → P2′ barrier increases markedly (≈ 1.70 eV vs. 1.24 eV in NMO), indicating enhanced stability at low voltage. At high voltage, however P2 → O becomes easier (≈ 1.04 eV at xNa ≈ 0.125), rationalizing the phase conversion observed near the O-redox region (∼≥ 4.1 V). Notably, at an intermediate SoC (xNa ≈ 0.375), the P → O barrier in NNMO is large (∼2.9 eV), suggesting that glides are only triggered at deep desodiation. 46 Two elementary motions underpin these transitions: (i) an in-plane shift/rotation of TMO6 units within the ab plane that preserves oxygen-layer superimposability, driving P2 → P2′, and (ii) an alternating glide of TMO2 sheets with a π/3 rotation that disrupts O-stacking, driving P2 → O (Fig. 7c). Along both pathways, the transition state (TS) features a tetrahedral coordination around TM, consistent with EXAFS evidence of coordination changes during cycling. 39

Energy profiles for phase transitions at the critical xNa: (a) NMO and (b) NNMO. Barriers for P2 → P2′ and P2 → O transitions are plotted in blue and red, respectively. (c) Schematic representation of the P2 → P2′ mechanism, highlighting the in-plane shifts of TMO6. Yellow and orange circles mark the oxygen ligands involved and their displacements; dotted and filled circles indicate initial and final positions, respectively. Reproduced from Langella et al. 46 Copyright 2025 American Chemical Society.

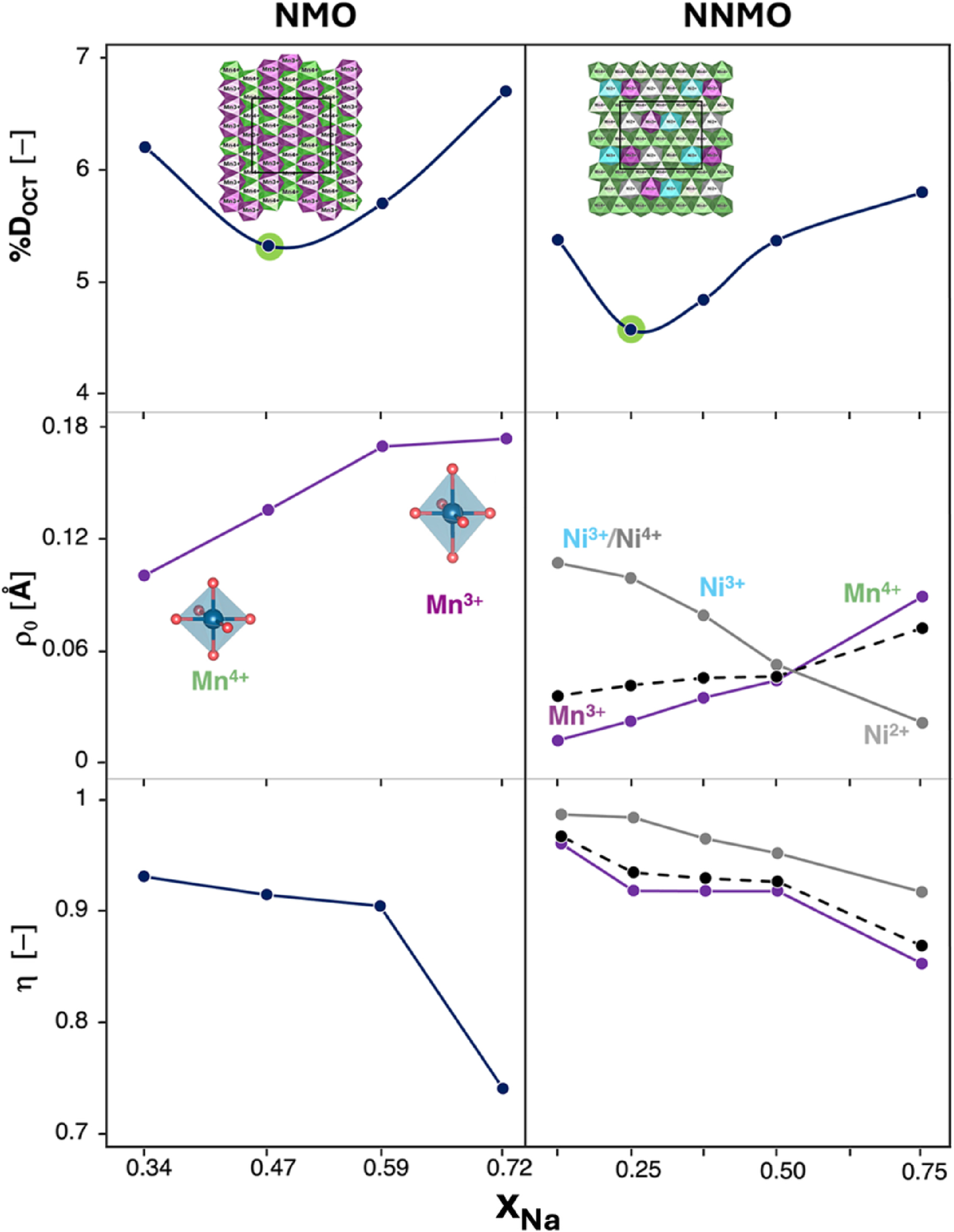

To derive a practical metric for predicting phase-transition propensity, and to complement the previously proposed EVO descriptor, we employed Van Vleck crystal-field theory, 79 , 106 as implemented in the Van Vleck calculator. 79 Decomposition of octahedral distortions (DOct) into distinct modes reveals two key drivers: (i) bond-length (Jahn–Teller-like) distortions, quantified by the magnitude ρ0, and (ii) bond-angle (tilt/shear) distortions, summarized by the fractional parameter η 46 (Fig. 8). For NMO, as shown in top right panel of Fig. 8, DOct follows a U-shaped trend versus xNa, with a minimum near xNa ≈ 0.47. 43 , 46 At low Na content, tilt/shear distortions (bottom right panel) increase (η↑), eventually approaching unity, at which point the P → O barrier becomes favorable.

Structural distortion parameters plotted as a function of xNa in (left) NMO and (right) P2-NNMO. The first row shows the octahedral distortion, %Doct, as a function of xNa. The second and the third rows present the magnitude of the distortion, ρ0, and fraction parameter, η, respectively. Insets are as follows. (first row) Cation distributions in the ab-plane with O and Na atoms removed for clarity. Color code: Mn3+-centered octahedra, violet; Mn4+-centered octahedra, green; Ni2+-centered octahedra, gray; Ni3+-centered, turquoise. (second row) Schematic of an ideal Mn4+O6 octahedron and axially elongated Mn3+O6 one. Reproduced from Langella et al. 46 Copyright 2025 American Chemical Society.

In NNMO, ρ0 (Mn) (left middle panel, Fig. 8), decreases upon Mn3+ to Mn4+ oxidation, while ρ0 (Ni) (left bottom panel, Fig. 8), increases due to the Jahn–Teller activity of Ni3+. Nevertheless, the net ρ0 remains smaller than in NMO, consistent with the higher P2 → P2′ barrier. This highlights ρ0 as a fundamental parameter to assess the effect of doping, whether it alleviates or amplifies octahedral distortions. In this case, Ni substitution enhances capacity, but excessive Ni content could reverse the trend at low xNa, increasing distortions and thus favoring structural instabilities. At deep desodiation, η (bottom left panel, Fig. 8) again approaches unity, at which point even in NNMO the P → O barrier becomes accessible, confirming shear as the primary kinetic lever for phase transitions at high voltage.

Conclusions and perspectives

This work has outlined a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding P2–Mn-based layered oxides, emphasizing how oxygen redox activity and solid-state phase transitions jointly govern their electrochemical stability at high voltages. By integrating electronic-structure analysis, defect energetics, and transition-state modeling, we establish descriptor-based guidelines that can inform the rational design of advanced sodium-ion cathodes.

Key insights can be summarized as follows:

Charge-compensation mechanisms. In all doped systems, the Mn sublattice remains largely electrochemically inert at high voltage, retaining Mn4+ or mixed Mn3+/Mn4+ states. Instead, selected TM dopants (Ni, Fe, Ru) act as the primary redox-active species, enhancing capacity. However, their amount must be carefully tuned, as excessive substitution can induce structural instabilities, a balance that can be assessed through the ρ0 parameter.

TM–O covalency and oxygen activity. In undoped NNMO, low-energy superoxide intermediates act as precursors to O2 release, especially near Mn-deficient sites. By contrast, Fe and Ru substitution strengthen TM–O covalency, confining anionic oxidation to reversible superoxide formation while suppressing molecular O2 evolution.

Oxygen vacancy energetics. The formation energy of oxygen vacancies (EVO) emerges as a simple, first-principles descriptor of TM–O bond lability and, by extension, of a composition’s propensity for O2− oxidation and O2 evolution.

Phase-transition mechanisms. Beyond redox chemistry, instability also arises from P2 → P2′ and P2 → O glides. Geometric descriptors (ρ0, η) derived from octahedral distortion analysis, provide a direct and intuitive link between transition-metal composition and phase-transition propensity.

Table 1 summarizes the main cathode compositions investigated in this work, the dominant high-voltage instabilities, and the associated structural and electronic descriptors (ρ0, η, EVO). Together with their physical meaning and computational accessibility, these descriptors serve as a digital design toolbox to rationalize degradation mechanisms and guide targeted mitigation strategies.

Summary of the main P2–Mn-based layered oxides investigated, their dominant high-voltage instabilities, and the associated electronic/structural descriptors.

| Composition | Main high-voltage instability | Descriptor | Predictive role | Mitigation strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMO | P2 → O transition | η, ρ0 | η → 1 indicates shear-driven instability ρ0 → evaluates dopant content |

Aliovalent doping, Na-substitution |

| NNMO | O2 release | EVO | Low EVO signals high O2-evolution tendency | NRNMO/NFNMO |

Together, these findings serve as foundation for a new design strategy for high-voltage sodium cathodes: reinforce TM–O covalency to enable reversible oxygen redox while suppressing O2 release; optimize ρ0 to minimize Jahn–Teller distortions; and maintain η below unity to prevent shear-driven P → O glides. Such descriptors are readily accessible from first-principles calculations and can thus accelerate the discovery of new effective sodium-ion cathodes. Beyond their immediate use in rational design, these physics-based descriptors can also act as transferable features for automated high-throughput screening and as input parameters for machine-learning models, offering a powerful route to efficiently explore the vast compositional space of candidate cathode materials.

Although developed here for P2–Mn layered oxides, the descriptors advanced in this work, ρ0 (bond-length distortion), η (shear/tilt), and EVO (oxygen-vacancy formation energy), map naturally onto other cathode families: they connect to covalency-controlled O-redox in Li-rich layered materials, to inductive-effect stabilization in polyanion frameworks, and to vacancy-governed stability in Prussian blue analogues. 107

Looking ahead, future research should address the interplay between bulk mechanisms and surface/interface phenomena, where oxygen activity may be strongly influenced by electrolyte reactivity. Bridging first-principles modeling with operando characterization will be essential to validate these descriptors. Moreover, integrating parameters such as EVO, ρ0, and η into machine-learning (ML) frameworks for crystal design offers a promising route to rapidly screen compositional space and identify cathode materials that combine reversible anionic redox with structural robustness. Preliminary studies have already demonstrated the potential of ML for Na-based cathodes, for example in predicting redox potentials, phase stability, and Na-ion mobility in layered oxides. 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 While these approaches remain at an early stage compared to the more established Li-ion field, they underscore the feasibility of using descriptors such as ρ0, η, and EVO as effective features in future ML-guided discovery of sodium-ion cathodes. This synergy between physics-based modeling, data-driven approaches, and experimental validation will be key to accelerating the digital discovery of sustainable, high-energy sodium cathodes tailored for next-generation solid-state batteries.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the NEST–Network for Energy Sustainable Transition and received funding from the European Union Next-Generation EU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR)–MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.3). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them. Authors also acknowledge funding from the ORANGEES project (Italian Ministry of Environment and Energy Security, Research of the National Electric System PTR 2019–2021). The computing resources and the related technical support used for this work have been provided by the CRESCO/ENEA-GRID High Performance Computing infrastructure and its staff. 113 The CRESCO/ENEAGRID High Performance Computing infrastructure is funded by ENEA, Italy, the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development and by Italian and European research programs; see https://www.cresco.enea.it for information.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Abraham, K. M. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5 (11), 3544–3547. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02181.Search in Google Scholar

2. Delmas, C. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8 (17), 1703137. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201703137.Search in Google Scholar

3. Yoo, H. D.; Shterenberg, I.; Gofer, Y.; Gershinsky, G.; Pour, N.; Aurbach, D. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6 (8), 2265. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ee40871j.Search in Google Scholar

4. Tarascon, J.-M. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2 (6), 510. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.680.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Kurzweil, P. J. Power Sources 2010, 195 (14), 4424–4434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.12.126.Search in Google Scholar

6. Ponrouch, A.; Palacín, M. R. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2019, 377 (2152), 20180297. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2018.0297.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Hwang, J.-Y.; Myung, S.-T.; Sun, Y.-K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46 (12), 3529–3614. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cs00776g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Palomares, V.; Serras, P.; Villaluenga, I.; Hueso, K. B.; Carretero-González, J.; Rojo, T. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5 (3), 5884. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2ee02781j.Search in Google Scholar

9. Doughty, D. H.; Butler, P. C.; Akhil, A. A.; Clark, N. H.; Boyes, J. D. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2010, 19 (3), 49. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.f05103if.Search in Google Scholar

10. Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Ji, J.; Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Sun, M.; Lin, Z.; Ling, M.; Zheng, J.; Liang, C. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12 (5), 1512–1533.10.1039/C8EE03727BSearch in Google Scholar

11. Kim, J. G.; Son, B.; Mukherjee, S.; Schuppert, N.; Bates, A.; Kwon, O.; Choi, M. J.; Chung, H. Y.; Park, S. J. Power Sources 2015, 282, 299–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.02.054.Search in Google Scholar

12. Lim, H.-D.; Park, J.-H.; Shin, H.-J.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J. T.; Nam, K.-W.; Jung, H.-G.; Chung, K. Y. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 25, 224–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2019.10.011.Search in Google Scholar

13. Chayambuka, K.; Mulder, G.; Danilov, D. L.; Notten, P. H. L. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8 (16), 1800079. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201800079.Search in Google Scholar

14. Huang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Adams, F.; Luo, W.; Huang, Y.; Hu, L. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3 (7), 1604–1612. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00609.Search in Google Scholar

15. Li, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Shao, Z.; Guo, Z. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11 (9), 2310–2340. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ee01023d.Search in Google Scholar

16. Massaro, A.; Pecoraro, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125 (4), 2276–2286.10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c10107Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Barik, G.; Pal, S. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123 (36), 21852–21865. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b04128.Search in Google Scholar

18. Chu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Jia, Y.; Dong, X.; Xiao, J.; Tao, Y.; Yang, Q.-H. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35 (31), 2212186. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202212186.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Beaulieu, L. Y.; Hatchard, T. D.; Bonakdarpour, A.; Fleischauer, M. D.; Dahn, J. R. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150 (11), A1457. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1613668.Search in Google Scholar

20. Fasulo, F.; Massaro, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37 (19), 3216–3226.10.1557/s43578-022-00579-1Search in Google Scholar

21. Brugnetti, G.; Triolo, C.; Massaro, A.; Ostroman, I.; Pianta, N.; Ferrara, C.; Sheptyakov, D.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M.; Santangelo, S.; Ruffo, R. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35 (20), 8440–8454. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.3c01196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Ke, M.; Wan, M.; Dong, W.; Wei, T.; Dou, H.; Zhang, X. Next Mater. 2025, 6, 100480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxmate.2024.100480.Search in Google Scholar

23. Wang, P.-F.; You, Y.; Yin, Y.-X.; Guo, Y.-G. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8 (8), 1701912. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201701912.Search in Google Scholar

24. Delmas, C.; Fouassier, C.; Hagenmuller, P. Physica B+C 1980, 99 (1), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4363(80)90214-4.Search in Google Scholar

25. Delmas, C.; Braconnier, J.-J.; Fouassier, C.; Hagenmuller, P. Solid State Ionics 1981, 3–4, 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2738(81)90076-x.Search in Google Scholar

26. Massaro, A.; Fasulo, F.; Pecoraro, A.; Langella, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25 (28), 18623–18641. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cp01201h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Hou, P.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J.; Xu, X. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7 (9), 4705–4713. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ta10980j.Search in Google Scholar

28. Fang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, J.; Deng, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yang, H. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6 (5), 1501727. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201501727.Search in Google Scholar

29. Bai, X.; Sathiya, M.; Mendoza-Sánchez, B.; Iadecola, A.; Vergnet, J.; Dedryvère, R.; Saubanère, M.; Abakumov, A. M.; Rozier, P.; Tarascon, J.-M. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8 (32), 1802379.10.1002/aenm.201802379Search in Google Scholar

30. Grimaud, A.; Hong, W. T.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Tarascon, J.-M. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15 (2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4551.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Edelman, D. A.; Eum, D.; Chueh, W. C. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7 (3), 234–235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01297-8.Search in Google Scholar

32. Larcher, D.; Tarascon, J.-M. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7 (1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.2085.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Huang, J.; Xu, L.; Ye, D.; Wu, W.; Qiu, S.; Tang, Z.; Wu, X. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.173397.Search in Google Scholar

34. Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, G.-H.; Kang, Y.-M.; Liu, R.; Li, F.; Chen, J. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12 (1), 2256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22523-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Massaro, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Prosini, P. P.; Gerbaldi, C.; Pavone, M. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6 (7), 2470–2480.10.1021/acsenergylett.1c01020Search in Google Scholar

36. Lu, Z.; Dahn, J. R. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148 (11), A1225. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1407247.Search in Google Scholar

37. Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Liao, X.-Z.; Xu, J.; Yang, D.; He, Y.-S.; Ma, Z.-F. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 113, 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2013.09.098.Search in Google Scholar

38. Ma, C.; Alvarado, J.; Xu, J.; Clément, R. J.; Kodur, M.; Tong, W.; Grey, C. P.; Meng, Y. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (13), 4835–4845. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b00164.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Li, Y.; Mazzio, K. A.; Yaqoob, N.; Sun, Y.; Freytag, A. I.; Wong, D.; Schulz, C.; Baran, V.; Mendez, A. S. J.; Schuck, G.; Zając, M.; Kaghazchi, P.; Adelhelm, P. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36 (18), 2309842. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202309842.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. de la Llave, E.; Talaie, E.; Levi, E.; Nayak, P. K.; Dixit, M.; Rao, P. T.; Hartmann, P.; Chesneau, F.; Major, D. T.; Greenstein, M.; Aurbach, D.; Nazar, L. F. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28 (24), 9064–9076. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b04078.Search in Google Scholar

41. Jiang, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; He, P.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (16), 14848–14853. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b03326.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Li, L.; Su, G.; Lu, C.; Ma, X.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, Z. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.136923.Search in Google Scholar

43. Langella, A.; Massaro, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36 (5), 2370–2379.10.1021/acs.chemmater.3c02981Search in Google Scholar

44. Massaro, A.; Langella, A.; Gerbaldi, C.; Elia, G. A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5 (9), 10721–10730. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.2c01455.Search in Google Scholar

45. Massaro, A.; Langella, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 106 (1), 109–119.10.1111/jace.18494Search in Google Scholar

46. Langella, A.; Massaro, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. ACS Energy Lett. 2025, 10 (3), 1089–1098.10.1021/acsenergylett.4c03335Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Yao, Z.; Chan, M. K. Y.; Wolverton, C. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34 (10), 4536–4547. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c00322.Search in Google Scholar

48. Sathiya, M.; Rousse, G.; Ramesha, K.; Laisa, C. P.; Vezin, H.; Sougrati, M. T.; Doublet, M.-L.; Foix, D.; Gonbeau, D.; Walker, W.; Prakash, A. S.; Ben Hassine, M.; Dupont, L.; Tarascon, J.-M. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12 (9), 827–835. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3699.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Assat, G.; Tarascon, J.-M. Nat. Energy 2018, 3 (5), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-018-0097-0.Search in Google Scholar

50. Soundharrajan, V.; Alfaruqi, M. H.; Alfaza, G.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Park, S.; Nithiananth, S.; Pham, D. T.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Kim, J. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11 (28), 15518–15531. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ta02291a.Search in Google Scholar

51. Kim, Y.; Oh, G.; Lee, J.; Baek, J.; Alfaza, G.; Lee, S.; Mathew, V.; Kansara, S.; Hwang, J.-Y.; Kim, J. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16 (5), 5896–5904. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c17166.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Minnetti, L.; Paparoni, F.; Zitolo, A.; Silly, M. G.; Torretti, E.; Rezvani, J.; Nobili, F. Acta Mater. 2025, 301, 121518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2025.121518.Search in Google Scholar

53. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54 (16), 11169–11186. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.54.11169.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59 (3), 1758–1775. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.59.1758.Search in Google Scholar

55. Blöchl, P. E. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50 (24), 17953–17979. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.50.17953.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77 (18), 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865.Search in Google Scholar

57. Kohn, W.; Sham, L. J. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140 (4A), A1133–A1138. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.140.a1133.Search in Google Scholar

58. Kim, H.; Koo, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Park, S.; Cho, M.; Kim, D. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 45, 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2021.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

59. Shi, X.-H.; Wang, Y.-P.; Cao, X.; Wu, S.; Hou, Z.; Zhu, Z. ACS Omega 2022, 7 (17), 14875–14886. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.2c00375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Vergnet, J.; Saubanère, M.; Doublet, M.-L.; Tarascon, J.-M. Joule 2020, 4 (2), 420–434.10.1016/j.joule.2019.12.003Search in Google Scholar

61. Ben Yahia, M.; Vergnet, J.; Saubanère, M.; Doublet, M.-L. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18 (5), 496–502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0318-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Fabris, S.; De Gironcoli, S.; Baroni, S.; Vicario, G.; Balducci, G. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71 (4), 041102. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.71.041102.Search in Google Scholar

63. Pacchioni, G. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128 (18), 182505. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2819245.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Wang, L.; Maxisch, T.; Ceder, G. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73 (19), 195107. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.73.195107.Search in Google Scholar

65. Mosey, N. J.; Liao, P.; Carter, E. A. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129 (1), 014103. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2943142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Verma, P.; Truhlar, D. G. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2016, 135 (8), 182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-016-1927-4.Search in Google Scholar

67. Franchini, C.; Bayer, V.; Podloucky, R.; Paier, J.; Kresse, G. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72 (4), 045132. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.72.045132.Search in Google Scholar

68. Goodenough, J. B.; Kim, Y. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22 (3), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm901452z.Search in Google Scholar

69. Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132 (15), 154104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3382344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Pecoraro, A.; Schiavo, E.; Maddalena, P.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M. J. Comput. Chem. 2020, 41 (22), 1946–1955. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.26364.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

71. Barone, V.; Casarin, M.; Forrer, D.; Pavone, M.; Sambi, M.; Vittadini, A. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30 (6), 934–939. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

72. Sannino, G. V.; Pecoraro, A.; Maddalena, P.; Bruno, A.; Veneri, P. D.; Pavone, M.; Muñoz-García, A. B. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7 (19), 4855–4863. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3se00362k.Search in Google Scholar

73. Pecoraro, A.; Fasulo, F.; Pavone, M.; Muñoz-García, A. B. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59 (34), 5055–5058. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3cc00960b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Coppola, C.; Pecoraro, A.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Infantino, R.; Dessì, A.; Reginato, G.; Basosi, R.; Sinicropi, A.; Pavone, M. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24 (24), 14993–15002.10.1039/D2CP01270GSearch in Google Scholar

75. Pecoraro, A.; Maddalena, P.; Pavone, M.; Muñoz García, A. B. Materials 2022, 15 (16), 5703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15165703.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76. Monkhorst, H. J.; Pack, J. D. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13 (12), 5188–5192. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.13.5188.Search in Google Scholar

77. Zunger, A.; Wei, S.-H.; Ferreira, L. G.; Bernard, J. E. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 65 (3), 353–356. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.65.353.Search in Google Scholar

78. Gehringer, D.; Friák, M.; Holec, D. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2023, 286, 108664.10.1016/j.cpc.2023.108664Search in Google Scholar

79. Nagle-Cocco, L. A. V.; Dutton, S. E. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2024, 57 (1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600576723009925.Search in Google Scholar

80. Therrien, F.; Graf, P.; Stevanović, V. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152 (7), 074106. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5131527.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Qian, G.-R.; Dong, X.; Zhou, X.-F.; Tian, Y.; Oganov, A. R.; Wang, H.-T. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013, 184 (9), 2111–2118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2013.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

82. Glass, C. W.; Oganov, A. R.; Hansen, N. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2006, 175 (11), 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2006.07.020.Search in Google Scholar

83. Goodenough, J. B. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998, 28 (1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.matsci.28.1.1.Search in Google Scholar

84. Sturge, M. D. Solid State Physics, Vol. 20; Academic Press: New York and London, 1968; pp 91–211.10.1016/S0081-1947(08)60218-0Search in Google Scholar

85. Jung, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, S. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132 (5), 055101. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0086903.Search in Google Scholar

86. Gehring, G. A.; Gehring, K. A. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1975, 38 (1), 1–89. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/38/1/001.Search in Google Scholar

87. Wang, P.-F.; Jin, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.-C.; Ji, X.; Cui, C.; Piao, N.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.-Q.; Wang, C. Nano Energy 2020, 77, 105167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105167.Search in Google Scholar

88. Manzi, J.; Paolone, A.; Palumbo, O.; Corona, D.; Massaro, A.; Cavaliere, R.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Trequattrini, F.; Pavone, M.; Brutti, S. Energies 2021, 14 (5), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14051230.Search in Google Scholar

89. Li, X.; Ma, X.; Su, D.; Liu, L.; Chisnell, R.; Ong, S. P.; Chen, H.; Toumar, A.; Idrobo, J.-C.; Lei, Y.; Bai, J.; Wang, F.; Lynn, J. W.; Lee, Y. S.; Ceder, G. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13 (6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3964.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

90. Mori, S.; Chen, C. H.; Cheong, S.-W. Nature 1998, 392 (6675), 473–476. https://doi.org/10.1038/33105.Search in Google Scholar

91. Margadonna, S.; Karotsis, G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (51), 16436–16437. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0669272.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

92. Raveau, B.; Hervieu, M.; Maignan, A.; Martin, C. J. Mater. Chem. 2001, 11 (1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1039/b003243n.Search in Google Scholar

93. Massaro, A.; Fasulo, F.; Langella, A.; Muñoz-Garcia, A. B.; Pavone, M. Computational Design of Battery Materials; Hanaor, D. A. H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2024; pp. 367–401.10.1007/978-3-031-47303-6_13Search in Google Scholar

94. Wang, P.-F.; You, Y.; Yin, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.-S.; Wan, L.-J.; Gu, L.; Guo, Y.-G. Angew. Chem. 2016, 128 (26), 7571–7575. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201602202.Search in Google Scholar

95. Massaro, A.; Lingua, G.; Bozza, F.; Piovano, A.; Prosini, P. P.; Muñoz-García, A. B.; Pavone, M.; Gerbaldi, C. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36 (14), 7046–7055. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.4c01311.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

96. Saubanère, M.; McCalla, E.; Tarascon, J.-M.; Doublet, M.-L. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9 (3), 984–991. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ee03048j.Search in Google Scholar

97. Dietrich, H. Angew. Chem. 1961, 73 (14), 511–512. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.19610731425.Search in Google Scholar

98. Cramer, C. J.; Tolman, W. B.; Theopold, K. H.; Rheingold, A. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100 (7), 3635–3640. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0535926100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

99. Zhang, Y.; Wu, M.; Ma, J.; Wei, G.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, R.; Huang, Y. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6 (2), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscentsci.9b01166.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

100. Shen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jin, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, P.; Qu, X.; Jiao, L. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31 (51), 2106923. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202106923.Search in Google Scholar

101. Wang, Q.; Jiang, K.; Feng, Y.; Chu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12 (35), 39056–39062. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c09082.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

102. Yu, Y.; Karayaylali, P.; Nowak, S. H.; Giordano, L.; Gauthier, M.; Hong, W.; Kou, R.; Li, Q.; Vinson, J.; Kroll, T.; Sokaras, D.; Sun, C.-J.; Charles, N.; Maglia, F.; Jung, R.; Shao-Horn, Y. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31 (19), 7864–7876. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01821.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

103. Kiziltas-Yavuz, N.; Bhaskar, A.; Dixon, D.; Yavuz, M.; Nikolowski, K.; Lu, L.; Eichel, R.-A.; Ehrenberg, H. J. Power Sources 2014, 267, 533–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.05.110.Search in Google Scholar

104. Charles, N.; Yu, Y.; Giordano, L.; Jung, R.; Maglia, F.; Shao-Horn, Y. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32 (13), 5502–5514. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c00245.Search in Google Scholar

105. Pramanik, A.; Manche, A. G.; Lindgren, F.; Ericsson, T.; Häggström, L.; Cordes, D. B.; Armstrong, A. R. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 73, 103821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2024.103821.Search in Google Scholar

106. Van Vleck, J. H. J. Chem. Phys. 1939, 7 (1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1750327.Search in Google Scholar

107. Fayaz, M.; Lai, W.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Abbas, S. M.; Chen, Y. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 170, 112593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2023.112593.Search in Google Scholar

108. Li, L.; Shen, J.; Xiao, Q.; He, C.; Zheng, J.; Chu, C.; Chen, C. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36 (11), 110421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2024.110421.Search in Google Scholar

109. Li, C.-N.; Liang, H.-P.; Zhao, B.-Q.; Wei, S.-H.; Zhang, X. J. Mater. Inform. 2024, 4 (3).Search in Google Scholar

110. Wengert, S.; Csányi, G.; Reuter, K.; Margraf, J. T. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (12), 4536–4546. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0sc05765g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

111. An, R.; Xie, C.; Chu, D.; Li, F.; Pan, S.; Yang, Z. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16 (28), 36658–36666. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c10477.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

112. Guo, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.-H.; Gong, X.-G. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12 (17), 10124–10136. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ta00721b.Search in Google Scholar

113. Ponti, G.; Palombi, F.; Abate, D.; Ambrosino, F.; Aprea, G.; Bastianelli, T.; Beone, F.; Bertini, R.; Bracco, G.; Caporicci, M.; Calosso, B.; Chinnici, M.; Colavincenzo, A.; Cucurullo, A.; Dangelo, P.; De Rosa, M.; De Michele, P.; Funel, A.; Furini, G.; Giammattei, D.; Giusepponi, S.; Guadagni, R.; Guarnieri, G.; Italiano, A.; Magagnino, S.; Mariano, A.; Mencuccini, G.; Mercuri, C.; Migliori, S.; Ornelli, P.; Pecoraro, S.; Perozziello, A.; Pierattini, S.; Podda, S.; Poggi, F.; Quintiliani, A.; Rocchi, A.; Sciò, C.; Simoni, F.; Vita, A. 2014 International Conference on High Performance Computing & Simulation (HPCS), 2014; pp. 1030–1033.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 IUPAC & De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Recommendations

- Experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data (IUPAC Recommendations 2025)

- IUPAC Technical Reports

- Kinetic parameters for thermal decomposition of commercially available dialkyldiazenes (IUPAC Technical Report)

- FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collections – advice for researchers, authors, and data managers (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Review Articles

- Are the Lennard-Jones potential parameters endowed with transferability? Lessons learnt from noble gases

- Quantum mechanics and human dynamics

- Quantum chemistry and large systems – a personal perspective

- The organic chemist and the quantum through the prism of R. B. Woodward

- Relativistic quantum theory for atomic and molecular response properties

- A chemical perspective of the 100 years of quantum mechanics

- Methylene: a turning point in the history of quantum chemistry and an enduring paradigm

- Quantum chemistry – from the first steps to linear-scaling electronic structure methods

- Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics on quantum computers: challenges and opportunities

- Research Articles

- Alzheimer’s disease – because β-amyloid cannot distinguish neurons from bacteria: an in silico simulation study

- Molecular electrostatic potential as a guide to intermolecular interactions: challenge of nucleophilic interaction sites

- Photophysical properties of functionalized terphenyls and implications to photoredox catalysis

- Combining molecular fragmentation and machine learning for accurate prediction of adiabatic ionization potentials

- Thermodynamic and kinetic insights into B10H14 and B10H14 2−

- Quantum origin of atoms and molecules – role of electron dynamics and energy degeneracy in atomic reactivity and chemical bonding

- Clifford Gaussians as Atomic Orbitals for periodic systems: one and two electrons in a Clifford Torus

- First-principles modeling of structural and RedOx processes in high-voltage Mn-based cathodes for sodium-ion batteries

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Furanyl-Chalcones as antimalarial agent: synthesis, in vitro study, DFT, and docking analysis of PfDHFR inhibition

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Recommendations

- Experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data (IUPAC Recommendations 2025)

- IUPAC Technical Reports

- Kinetic parameters for thermal decomposition of commercially available dialkyldiazenes (IUPAC Technical Report)

- FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collections – advice for researchers, authors, and data managers (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Review Articles

- Are the Lennard-Jones potential parameters endowed with transferability? Lessons learnt from noble gases

- Quantum mechanics and human dynamics

- Quantum chemistry and large systems – a personal perspective

- The organic chemist and the quantum through the prism of R. B. Woodward

- Relativistic quantum theory for atomic and molecular response properties

- A chemical perspective of the 100 years of quantum mechanics

- Methylene: a turning point in the history of quantum chemistry and an enduring paradigm

- Quantum chemistry – from the first steps to linear-scaling electronic structure methods

- Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics on quantum computers: challenges and opportunities

- Research Articles

- Alzheimer’s disease – because β-amyloid cannot distinguish neurons from bacteria: an in silico simulation study

- Molecular electrostatic potential as a guide to intermolecular interactions: challenge of nucleophilic interaction sites

- Photophysical properties of functionalized terphenyls and implications to photoredox catalysis

- Combining molecular fragmentation and machine learning for accurate prediction of adiabatic ionization potentials

- Thermodynamic and kinetic insights into B10H14 and B10H14 2−

- Quantum origin of atoms and molecules – role of electron dynamics and energy degeneracy in atomic reactivity and chemical bonding

- Clifford Gaussians as Atomic Orbitals for periodic systems: one and two electrons in a Clifford Torus

- First-principles modeling of structural and RedOx processes in high-voltage Mn-based cathodes for sodium-ion batteries

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Furanyl-Chalcones as antimalarial agent: synthesis, in vitro study, DFT, and docking analysis of PfDHFR inhibition