Abstract

The International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ) celebrates the centenary of quantum mechanics (QM). In this perspective, I highlight that QM is not only a playground for physical chemists but of tremendous value to organic chemists as exemplified in its ever-increasing role in the career of Nobel prizewinner R.B. Woodward. Over three decades, this ranged from the prediction of UV-visible absorption wavelengths arising from electronic excitations to the importance of molecular orbital symmetry and the derivation of the Woodward-Hoffmann rules for pericyclic reactions.

Introduction

The United Nations declared 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ) to commemorate the centenary of Born and Heisenberg’s landmark publications on quantum mechanics (QM). 1 , 2 As editor of IUPAC’s Pure and Applied Chemistry, I was delighted by Russell Boyd and Manuel Yáñez’s proposal for us to celebrate IYQ through this special issue. Meanwhile, it got me thinking about how QM has influenced organic synthesis, as the connection between the two may not be obvious (our mathematics is usually limited to calculating % yield in a reaction!). I examine this interplay through the career of Robert Burns Woodward (Nobel prize 1965) who lived in exactly the right era to become the greatest organic chemist of all time. 3 , 4 In preceding generations, organic chemistry was still at a nascent stage with new compounds and reactions discovered at a rapid pace. By Woodward’s time, a solid bedrock of experimental facts was available that could be assimilated and extrapolated by someone with his unique talents. Since Woodward, the science has mushroomed at an exponential rate, and it is impossible for any individual to have either his encyclopedic memory or stay abreast of all the latest developments. Woodward’s greatest achievements were in structure elucidation, total synthesis, and reaction mechanisms, and I describe how the quantum became increasingly important in each of these endeavors.

Structure

Color is perhaps the most obvious physical characteristic of a molecule. In organic chemistry, it is manifest in plant natural products (Fig. 1) such as chlorophyll (intensively studied by Richard Willstätter, Nobel prize 1915 and later the subject of total synthesis by Woodward) and pelargonidin (synthesized by Sir Robert Robinson, Nobel prize 1947 and Woodward’s long time competitor), as well as created by transformations such as William Perkin’s serendipitous mauvein synthesis or Emil Fischer’s (Nobel prize 1902) formation of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazones as a diagnostic test for aldehydes and ketones. Where does this color come from? By the 1930s, as Woodward began his undergraduate studies at MIT, 5 it was appreciated that it arises through absorption in the UV-visible region by conjugated π-systems referred to as ‘chromophores’. Absorption of a photon at the right wavelength (λ max) excites an electron from the ground state (Eo) to an excited state (E1) if the quantum matches the energy gap, hν = E1 – Eo.

Examples of vividly coloured organic molecules.

The derivation of molecular orbitals (MOs) for conjugated organic systems was simplified by Erich Hückel’s approximation, as first demonstrated for benzene. 6 By using such molecular orbitals, Robert Mulliken (Nobel prize 1966) and others were able to calculate energy transitions and reproduce the experimentally observed spectra, as mentioned in Theodor Förster’s 1939 review on the origin of color in organic molecules. 7 Nevertheless, the quantum nature of electronic excitations was not widely acknowledged within the organic chemistry community. As Jerome Berson has pointed out ‘These papers, written in the elegant lapidary style familiar to mathematicians, and often published outside the conventional chemical journals, were important, but they were either unknown or largely unintelligible to many organic chemists.’ 8 Indeed, the influential 1938 textbook of organic chemistry by Paul Karrer (Nobel prize 1937) contains no mention of spectroscopy! 9 Nevertheless, without necessarily knowing the theoretical foundation, organic chemists found UV-visible spectroscopy a useful tool and added it to the arsenal of techniques for structure determination. By 1940, the German chemist Heinz Dannenberg had amassed the available spectra for over 200 steroids. 10 He noted certain trends on the magnitude by which λ max shifts upon perturbation of a chromophore. These empirical observations underpin Woodward’s first major scientific contribution. He applied correction values to enable direct comparison of spectra obtained in different solvents. He then placed the shifts in λ max on a secure mathematical footing, using a base value for the parent chromophore followed by adjustment for substitution. In his first 1941 publication, Woodward demonstrated that the λ max in α,β-unsaturated ketones are determined by the number of substituents on the C=C double bond and obtained calculated values consistent with the experimental data. 11 Interestingly, he references the original literature for his tables and Dannenberg is mentioned only once in the citation for one compound!

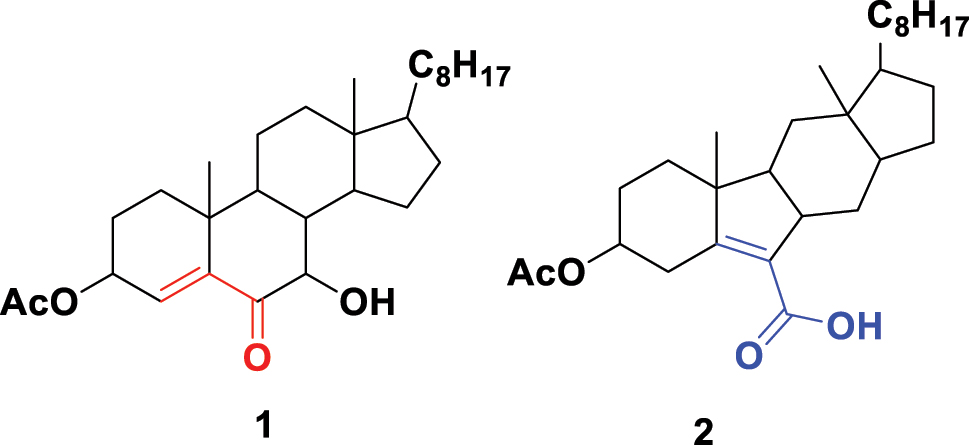

Woodward was sufficiently bold to claim that deviations from his calculated values were likely to be due to incorrect structure assignments. For example, the λ max < 230 nM of enone 1 (Fig. 2) was lower than the 239 ± 5 nM predicted by Woodward, who ‘tentatively suggests’ the true structure to be the B-ring contracted carboxylic acid 2. He would go on to prepare this compound, provide a mechanistic rationale for its formation, and further corroborating evidence for the structure in a follow up paper. 12 Woodward then extended his studies to the absorption spectra of conjugated dienes and compounds with exocyclic alkenes. 13 , 14 This set of publications and the resulting Woodward rules were widely employed by others and particularly helpful in the steroid field to confirm the presence of structural fragments and deciding between isomeric possibilities. There is evidence of Woodward corresponding with Mulliken regarding absorption spectra, 15 so he was at least aware of molecular orbitals and energy transitions although they are not mentioned in these publications. Later, Louis Fieser would refine Woodward’s λ max calculations and they are often known as the Woodward-Fieser rules. 16

Woodward’s structural revision of steroid 1 to 2 based on its UV-visible spectrum.

There are two major limitations of UV-visible spectroscopy for the characterisation of organic molecules. Firstly, it is applicable only to compounds containing a chromophore, and secondly, even for such conjugated systems, it is challenging to predict λ max for a novel chromophore. On the other hand, UV-visible data is valuable when suitable reference compounds are available. It featured prominently in Woodward’s structure elucidation of tetracycline antibiotics where the spectra of degradation products were compared with naphthols. 17 Among his total syntheses, the 1952 publication on steroids meticulously includes λ max and extinction coefficients for intermediates with conjugated systems but without comment as their structures were unambiguous. 18 The experimental section also contains reproduced copies of infrared (IR) spectra which by then had supplanted UV-visible as the organic chemist’s favorite spectroscopic method. The energy transitions in IR involve vibrational modes that are well approximated by classical mechanics treating chemical bonds as elastic springs without recourse to more complex QM considerations. Furthermore, the technique is universal to all molecules and immediately confirms the presence or absence of a specific type of covalent bond.

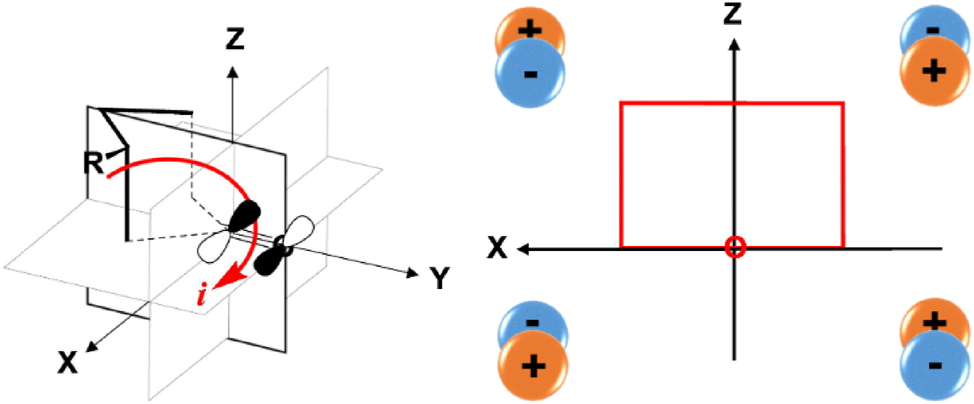

Woodward would make a second ‘rule’ type contribution to organic spectroscopy. The symmetry forbidden n → π* excitation of a carbonyl group results in weak absorption ∼ 300 nm. For a chiral compound, plotting the absorption of plane polarized light against wavelength produces an optical rotatory dispersion (ORD) curve. In the 1950s, William Moffitt and Albert Moscowitz were pioneering the theory behind ORD while Carl Djerassi’s group was experimentally recording the ORD curves of numerous cyclohexanones including steroid derivatives. Following a seminar by Djerassi at Harvard, the three together with Woodward discussed the available data and devised an ‘octant’ rule for predicting the sign of the ORD curve. 19 This involved assigning the space around a cyclohexanone into eight octants (Fig. 3) with substituents making positive or negative contributions depending on their orientation. 20 The octant rule was disclosed in a ground-breaking 1961 publication, sadly after Moffitt’s untimely demise. 21

The space around a cyclohexanone divided into octants in the x, y, z planes that make either positive or negative contributions to the ORD. “Reprinted with permission from Hatanaka, M.; Sayama, D.; Miyasaka, M. Optical activities of steroid ketones–elucidation of the octant rule. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 200, 298–306. Copyright 2018 Elsevier.”

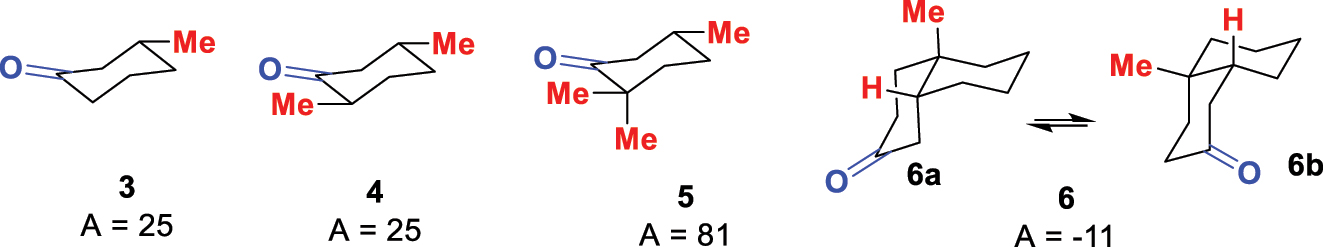

Like the earlier UV-visible Woodward rules, the power of the octant rule lies in its predictive power. For example, in the series of cyclohexanones 3–5 (Fig. 4) with an increasing number of methyl groups, the A value does not increase between 3-methylcyclohexanone (3) and trans-3,6-dimethylcyclohexanone (4). This can be rationalised as the second methyl group at C-6 is virtually in a nodal plane and does not significantly influence the ORD. The third methyl group at C-6 in 5, however, is out of plane and causes a major increase in the A value. The more complex cis-decalone 6 can exist in two conformations 6a or 6b that are respectively predicted to have either a negative or positive ORD. The observed negative ORD indicates a preference for the steroid-like conformation 6a with the angular methyl in an axial orientation – a conclusion beyond other analytical techniques at the time.

Examples of cyclohexanones with their A values measured by ORD.

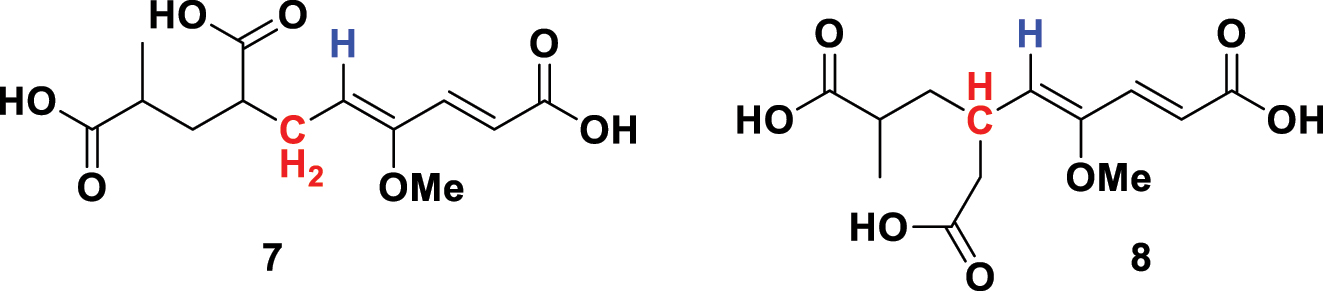

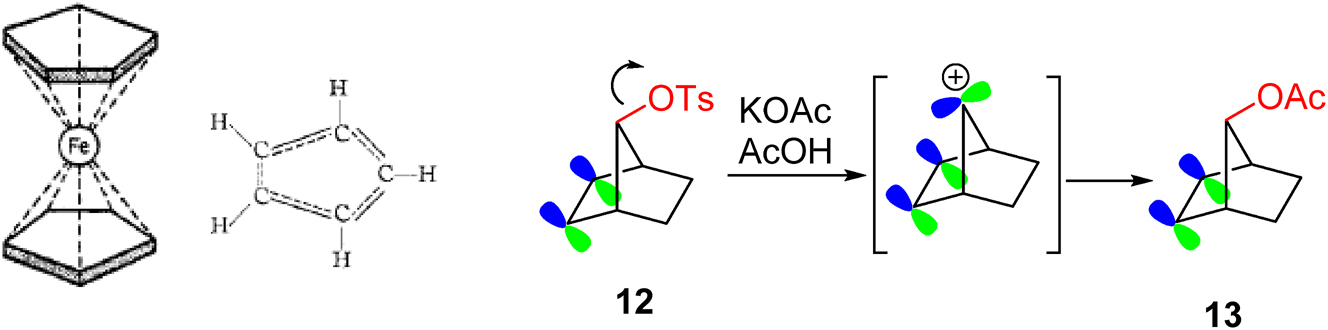

The 1960s heralded a new form of spectroscopy – nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) – that quickly became the workhorse for organic structural elucidation. The QM nuclear spin transitions that produce absorption in the radiofrequency region are straightforward to understand and do not require MO calculations. Both 1H and 13C atoms have a nuclear spin of ½ and give rise to NMR signals, thus making the technique universal to all organic molecules. The position of absorption is exquisitely sensitive to the immediate environment, which while initially annoying to physicists was of tremendous value to chemists. In addition, spin-spin coupling provides invaluable information on the number of neighboring spin-active atoms. Woodward was quick to champion any new technology and became an early adopter of NMR, which we encounter in his 1965 publication on the macrolide antibiotic magnamycin. 22 Part of the structure proof rested on a degradation product that was originally assigned as 7 (Fig. 5) but was potentially the isomer 8. To quote Woodward, ‘Examination of the nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum (60 Mc., CCl4 solution) of the trimethyl ester of the C13 acid revealed at once that structure 8 (my numbering – AG) is correct; sharp bands are present at 420, 405, 359, 344, 312, and 302 c.p.s. downfield from the tetramethylsilane reference band. All these bands are clearly associated with olefinic protons, and the lower field symmetrical quartet must be assigned to the α and β hydrogens of the trans –CH=CH- system. Consequently, the remaining doublet arises from the hydrogen of the –CH=C(OMe)- group, which must be adjacent to a methine grouping, as in 8 , and not to a methylene grouping, as in 7 .’

Coupling between the alkene proton (blue) and the adjacent hydrogens (red) enabled discrimination between the isomers 7 and 8.

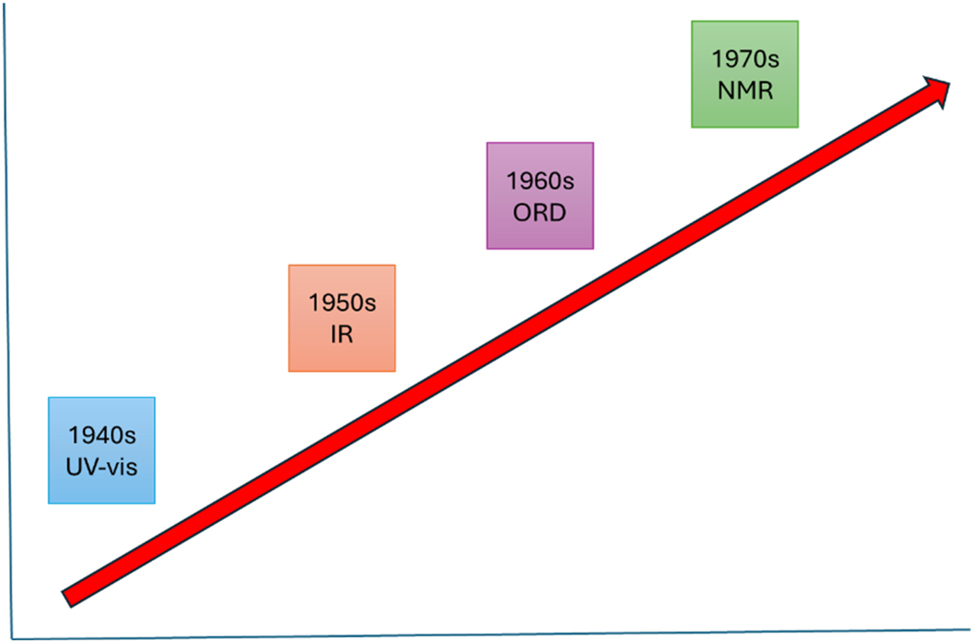

We can chart Woodward’s embracement of spectroscopic methods over time (Fig. 6). In each decade, he was at the forefront of applying emerging techniques to structure elucidation. His ability to derive simple relationships from a mountain of data in the literature produced the Woodward and octant rules that are still of value today. While Woodward did not devise rules for IR or NMR, he rapidly incorporated these methods into his research and was keenly aware of their ability to provide useful information for any molecule. Fluorescence, a possible consequence of UV-visible absorption, was not actively studied by organic chemists in his time. Subsequently, the ability to create and incorporate fluorophores has yielded many practical applications of value in materials science and biology.

The evolution of spectroscopic methods in organic chemistry over Woodward’s lifetime.

Reactivity

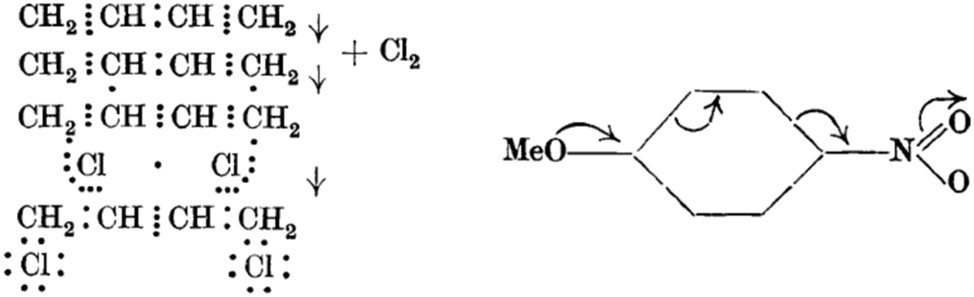

At the dawn of the 20th century, it was typical to state the reactants and products of organic reactions in a descriptive way without much consideration of mechanism. A step change occurred in the 1920s through the independent efforts of Robinson, Arthur Lapworth and Christopher Ingold in the United Kingdom who devised formal representations for the flow of electrons. In Robinson’s 1922 publication, the 1,4-addition of chlorine to butadiene is depicted in terms of Lewis dot structures (Fig. 7). 23 By 1925, we see a ‘curly arrow’ representation to explain why the p-directing effect of anisole is weakened by the presence of a nitro substituent at the 4 position. 24

Early examples of Robinson’s ‘arrow pushing’ for the reaction of butadiene with chlorine and the stabilisation of the nitro group in 4-nitroanisole by resonance. “Reprinted with permission from Kermack, W. O.; Robinson, R. LI. – An explanation of the property of induced polarity of atoms and an interpretation of the theory of partial valencies on an electronic basis. J. Chem. Soc. 1922, 121, 427–440 and Rây, J. N.; Robinson, R. CCXII. – The nitration of m-meconine. J. Chem. Soc. 1925, 127, 1618–1623. Copyright 1922 and 1925 Royal Society of Chemistry.”

Robinson coined the terms ‘kationoid’ and ‘anionoid’ respectively for sites of low and high electron density, a nomenclature which fell out of favor to Ingold’s proposal of ‘electrophile’ and ‘nucleophile’. The two also argued on the correct use of curly arrows and the wider community considered the topic controversial. Once again, I refer to Karrer’s comprehensive 1938 organic chemistry treatise – it does not contain any curly arrow mechanisms and neither does Wheland’s American textbook from a decade later! 9 , 25 Even Robinson rarely used curly arrows in his publications, preferring to explain reactions, when necessary, through written text. Two exceptions are the fission of benzophenones upon treatment with sodamide and the reaction of aldehydes with diazomethane (Fig. 8). 26 , 27 Here, we see curly arrows of the sort familiar to organic chemists today, although the benzophenone fission invokes breaking the N–H bond rather than the lone pair on nitrogen as a source of electrons.

Robinson’s curly arrows for the fission of benzophenones by sodamide and the reaction of aldehydes with diazomethane. “Reprinted with permission from Lea, T. R.; Robinson, R. CCCXIII. – The fission of some methoxylated benzophenones. J. Chem. Soc. 1926, 129, 2351–2355 and Bradley, W.; Robinson, R. CLXXIV. – The interaction of benzoyl chloride and diazomethane together with a discussion of the reactions of the diazenes. J. Chem. Soc. 1928, 1310–1318. Copyright 1926 and 1928 Royal Society of Chemistry.”

The young Woodward had an unsurpassed knowledge of the organic chemistry literature. However, he prized understanding above knowledge and would have avidly followed the attempts to explain reactions through arrow pushing. His first total synthesis, that of quinine, earned him an international reputation for successfully conquering such a complex target despite its terse communication in one page without a single structure. 28 Woodward’s route hinges on the reduction of isoquinoline 9 (Fig. 9) to the saturated bicycle 10 which undergoes cleavage to the desired cis-3,4-substituted piperidine 11 upon treatment with ethyl nitrite under basic conditions. Woodward does not comment on this unusual fragmentation and indeed, his communication has only three references in its entirety. A year later, in 1945, Woodward published a detailed account of the synthesis. 29 Now, a footnote mentions that a similar reaction was published in 1908, and he goes on to say, ‘The cleavage reaction clearly proceeds by the following mechanism (Fig. 9 – AG), to which attention has not hitherto been directed’. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time Woodward employed curly arrows. Henceforth, curly arrow mechanisms would feature prominently in his lectures and publications. The reason for their universal success, to this day, lies in an intuitive understanding that the full derivation of reactant and product MOs in an organic reaction is uneccesary. Most of these MOs are part of the skeletal framework and can be ignored as they are unperturbed. The curly arrow formalism focuses solely on the frontier orbitals that are involved in the reaction and would be further developed by Fukui and others in a rigorous manner (vide infra).

A key step in the Woodward total synthesis of quinine and his first curly arrow explanation of a reaction mechanism. “Reprinted with permission from Woodward, R. B.; Doering, W. E. The total synthesis of quinine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1945, 67 (5), 860–874. Copyright 1945 American Chemical Society.”

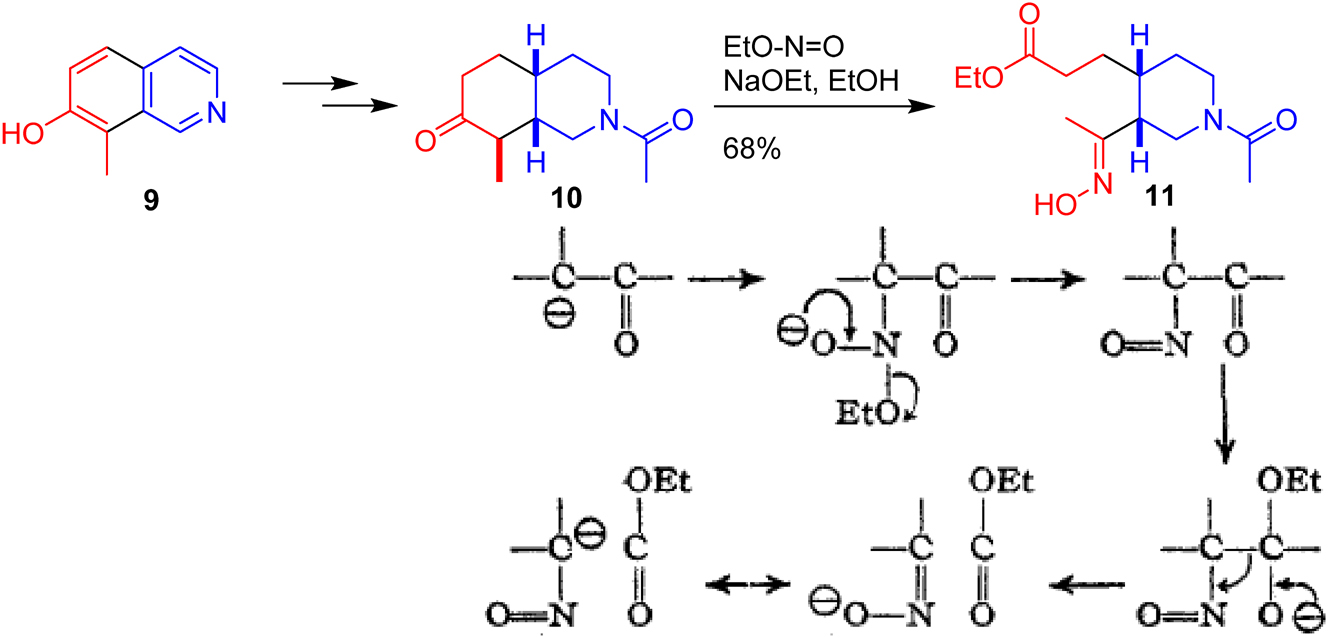

In 1951, Thomas Kealy and Peter Pauson reported ‘a new type of organo-iron compound’, iron biscyclopentadienyl, as a σ-bonded organometallic. 30 Woodward and Geoffrey Wilkinson at Harvard, and Ernst Fischer in Munich realized this was inconsistent with the compound’s high stability and physical properties and rapidly published papers that revised the structure to a π-complex. 31 , 32 Woodward was also quick to note that the C–C bonds would have partial double bond character in a delocalized manner like benzene (Fig. 10). 33 He named the iron complex ‘ferrocene’, predicted its aromatic character and proved that it undergoes acylation under Friedel-Crafts conditions. Wilkinson and Fischer would subsequently expand the inorganic chemistry of metallocene sandwich complexes and share the Nobel Prize in 1973 – undoubtedly aggrieving Woodward for not receiving a share for the structure determination and the recognition of ferrocene’s aromaticity.

Orbital delocalisation: Woodward’s representation of ferrocene as a π-complex with C–C bonds of partial double bond character, and the unusually rapid acetolysis of 12 due to assistance by the π-bond. The ferrocene structure and delocalisation are “Reprinted with permission from Woodward, R. B.; Rosenblum, M.; Whiting, M. C. A new aromatic system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74 (13), 3458–3459. Copyright 1952 American Chemical Society.”

Another example of Woodward and orbital delocalisation is evident in the 1955 publication with Saul Winstein on the 7-norbornenyl cation. 34 The facile acetolysis of 7-norbornenyl tosylate 12 with retention to produce 13 is justified as follows: ‘It will be noted that a homoallylic system is present, which is geometrically unique in that a vacant orbital on C.7 can overlap the p orbital systems of the double bond symmetrically.’

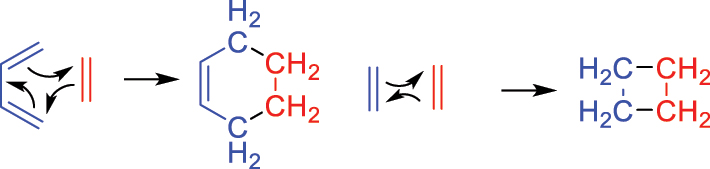

Most organic reactions, including those discussed above, are polar in nature and lend themselves well to the curly arrow formalism. Once nucleophilic and electrophilic sites are identified, a logical (or not so logical, according to students who find this challenging) sequence of arrows can be drawn for the flow of electrons from one to the other that accounts for the products. An exception is the Diels-Alder reaction (originally known as the diene synthesis) that fascinated Woodward for much of his life, beginning with undergraduate ideas for its use in the construction of the steroid nucleus. In its simplest case, the cyclisation of butadiene with ethylene, three curly arrows are sufficient to obtain the product (Fig. 11) but do not explain the driving force as neither reactant is electron-rich nor electron-poor. Furthermore, whilst there were myriad successful examples of the [4π + 2π] Diels-Alder reaction, the conceptually similar [2π + 2π] dimerization of ethylene to cyclobutane was virtually unknown.

Curly arrow mechanisms for the facile Diels-Alder reaction and the rare dimerization of ethylene.

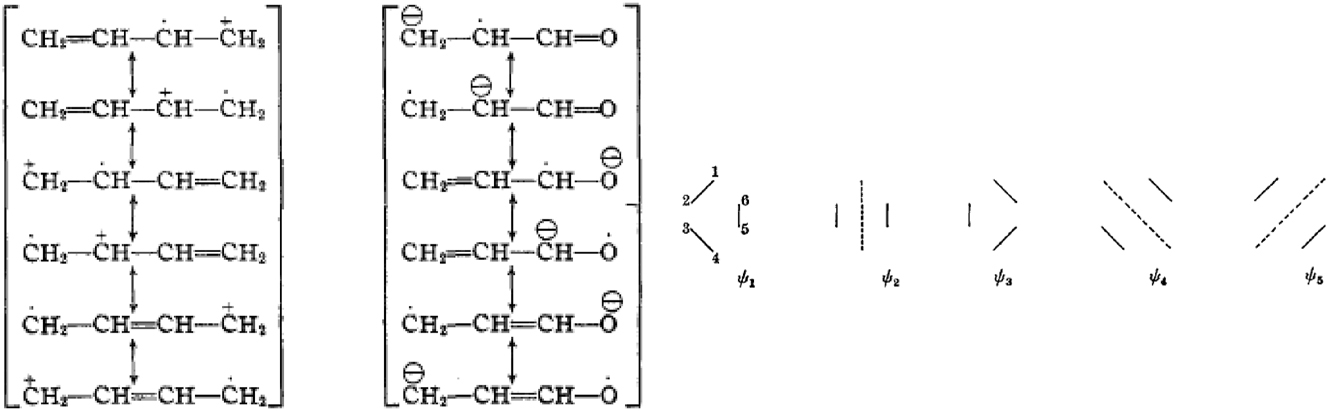

In Woodward’s first 1942 publication on the mechanism of the Diels-Alder, he proposed that it involves an initial electron transfer, as illustrated (Fig. 12) for the reaction between butadiene and acrolein. 35 With such charged intermediates, curly arrows can be easily drawn and two years later, he again employed polar transition states to account for the exo/endo preference of the Diels-Alder reaction between fulvene and maleic anhydride. 36 He appears unaware of contemporaneous efforts by physical chemists to explain the Diels-Alder reaction by MO theory. In a seminal 1939 paper, Meredith Evans states ‘In terms of the bond eigenfunction method the initial state can be defined in terms of the representations ψ1 and ψ2 whereas the final state will be given by ψ3. The transition state will be defined in terms of all five representations ψ1, ψ2, ψ3, ψ4 and ψ5. These same forms can be expressed in terms of the conception of “mobile electrons.” In the initial state the four p-electrons of the butadiene structure can be considered as moving in the periodic field of the carbon centres 1, 2, 3 and 4 and two p-electrons in the field of centres 5 and 6.’ 37

Woodward’s explanation of the Diels-Alder reaction through electron transfer (left) compared to Evans’s MO representation (right) of the transition state as a combination of ψ1, ψ2, ψ3, ψ4 and ψ5. “Reprinted with permission from Woodward, R. B. The mechanism of the Diels-Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1942, 64 (12), 3058–3059. Copyright 1942 American cChemical society, and Evans, M. G. The activation energies of reactions involving conjugated systems. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1939, 35, 824–834. Copyright 1939 Royal Society of Chemistry.”

The reluctance of Woodward to follow a QM path is typical of organic chemists in that period – curly arrows were readily drawn and understandable, unlike a statement that the transition state is ‘defined in terms of all five representations ψ1, ψ2, ψ3, ψ4 and ψ5.’ In his inaugural Arthur Cope award address in 1973, 3 Woodward is politely dismissive about QM: ‘Now, let me make a few remarks about the state of quantum chemistry in the early 1960s. First, I should mention that in the early 1930s, at least some of the protagonists of the new quantum mechanics took the view -rather superciliously-that, with the advent of the new discipline, chemistry had had it!: all of its problems were now solved in principle, and soon would be in practice’. Soon, gone forever would be the tentative, empirical, experimental, qualitative, heuristic, characteristics of chemistry as we had known it -to be replaced by sure-footed, essentially routine solution of chemical problems, solidly based on unassailable and universally applicable principles, readily translatable into precise, mathematically formulated operational protocols.

Thirty years later, that flamboyant promise had been far from realized. In fact, the yield for the organic chemist had been rather low. Hückel’s 4n + 2 rule had generated considerable fascinating and significant work. Pauling’s theory of “resonance” had had a good and useful run albeit the ground it covered paralleled closely that encompassed within the non-quantum-derived “mesomerism” of the English school. Many calculations of static properties of molecules had been made, but no one took them very seriously, least of all those who made them, when referring to calculations of others. And that was about it.’

From a practical point of view, Woodward placed the Diels-Alder reaction on a pedestal. Here was a process that constructed six-membered rings, his favorite size due to their predictable conformation, distinct axial and equatorial environments and frequent occurrence in his chosen natural product targets. It had the potential to create up to four new stereocenters in a rationally predictable manner and the Diels-Alder features prominently in his classic syntheses of steroids, reserpine and marasmic acid. In 1959, his final mechanistic publication on the reaction would provide stereochemical evidence consistent with a two-stage process. 38 His conclusions were immediately attacked by Michael Dewar who advocated a concerted one-step reaction through a quasi-aromatic transition state. 39 According to current opinion, Woodward was neither right nor wrong, as polarisation of the diene or dienophile results in an asynchronous transition state in which the two bonds are not formed to the same extent. 40 , 41

The 1962 publication by Walter von Eggers Doering (the former Woodward research fellow who singlehandedly completed the quinine synthesis and by now a professor) begins: ‘ “NO-MECHANISM” is the designation given, half in jest, half in desperation, to “thermoreorganization” reactions like the Diels-Alder and the Claisen and Cope rearrangements in which modern, mechanistic scrutiny discloses insensitivity to catalysis, little response to changes in medium and no involvement of common intermediates, such as carbanions, free radicals, carbonium ions and carbenes. Theoretical study of such thermally induced, usually cyclic reorganization reactions is concerned with transition states and their energies. The meaningful questions relate to the existence and structure of unstable intermediates, to the description of transition states (the favored one as well as real or reasonable alternatives), and to factors affecting the free energies of the relevant transition states. Although estimation and calculation of the free energies of activation is the most important aim of every mechanistic study, nowhere does this ultimate problem confront one more sharply than in the “thermoreorganization” reactions.’ 42 Interestingly, a footnote says the work was first submitted to Angewandte Chemie but they were informed of the editorial policy that ““wir rein theoretische Deutungen von Mechanismen nicht bringen. Wir tun es grundsätzlich nicht.” (We fundamentally don’t accept purely theoretical interpretations of mechanisms. – translation by AG).

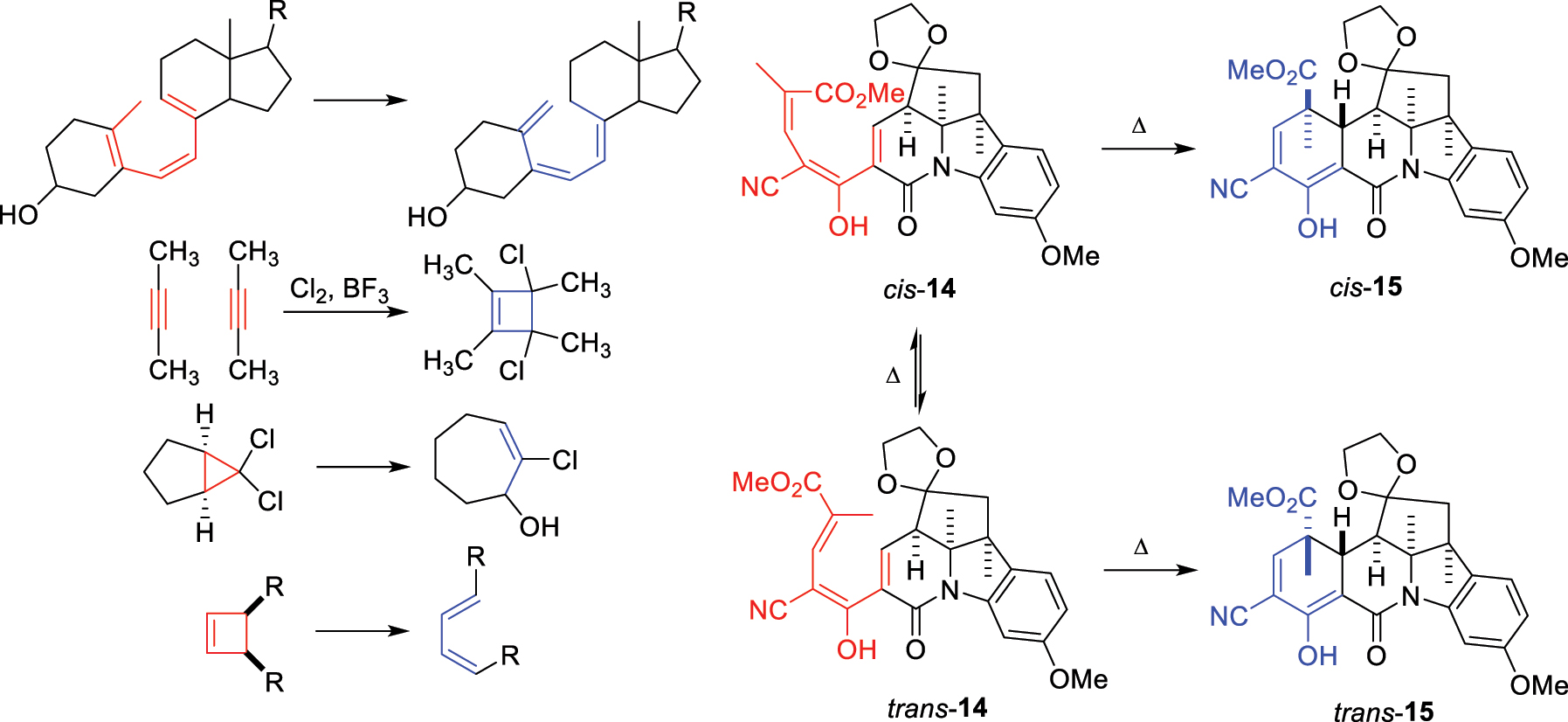

Woodward had his own collection of four ‘mysterious reactions’ (Fig. 13) that he expounds upon in his Cope lecture. 3 The first is the thermal isomerization of precalciferol to vitamin D without requiring any catalyst. The second, a variant of the elusive ethylene dimerization, ‘simply left me open-mouthed, with nothing to say.’ The third and fourth feature stereospecific ring openings – the solvolysis of a dichlorocyclopropane and the thermal rearrangement of a dimethylcyclobutene. Perhaps seeking inspiration, Woodward even asked Harvard postgraduates for the cyclobutene ring opening mechanism in a cumulative examination question without knowing the answer himself! Within his own group, another conundrum arose from the reactions uncovered by postdoctoral fellow Subramania Ranganathan during synthetic studies directed towards vitamin B12. The enolized ketonitrile 14 existed as an equilibrating mixture of cis/trans isomers. However, pure cis-14 thermally isomerized to the cyclohexadiene cis-15, while trans-14 isomerized to the cyclohexadiene trans-15. On the other hand, under photochemical irradiation, cis-15 was transformed into trans-14 and trans-15 into cis-14!

Woodward’s four ‘mysterious reactions’ and the series of thermal interconversions observed between trienes 14 and cyclohexadienes 15.

Isolated examples of MO explanations for ‘no-mechanism’ reactions were fragmented and lacked clarity. In his 1961 monograph, 43 then the bible on MO applications to organic chemistry, Andrew Streitwieser depicts the transition state for the Diels-Alder via orbital overlap between ψ1 of butadiene and ψ1 of ethylene. However, since ψ1 is the lowest occupied filled molecular orbital without any nodes, such ψ1-ψ1 interactions are always in phase and positive. He goes on to show a similar ψ1-ψ1 overlap for the dimerization of two ethylene molecules, suggesting that both the [4π + 2π] and [2π + 2π] reactions are equally permissible. Nevertheless, Woodward sensed that QM would be needed for a solution, and acknowledged his own inadequacy in the Cope address: 3 ‘From the very beginning, my new orbital ideas had, for my mind, that aura of inevitability which leads one to the conviction that one has discovered the correct solution to a problem, and I was confident that I had found that powerful and overriding, hitherto unrecognized factor which our vitamin B12 work had forced me to believe must exist. After a brief false start in extending these ideas, attributable clearly to my gaucherie in the details of quantum chemistry, I very soon realized that I needed more help than was available in my immediate circle, and I sought out Roald Hoffmann, who was well-known to me, though by reputation only, as a brilliant young theoretician, at that time, as I have already mentioned, a member of the Society of Fellows. I told him my story, and then, essentially, put to him the question: “Can you make this respectable in more sophisticated theoretical terms?” He could, and did; And thus began our immensely pleasurable, rewarding, and fruitful collaboration.’

It is fair to say this was one of the most productive chemistry collaborations of all time. Woodward had a set of chemical puzzles, while Hoffmann had the expertise to perform extended Hückel MO calculations, compute the geometry of transition states and derive general principles. 44 Their first communication in 1965 revealed the theoretical basis of the ‘mysterious’ cyclobutene to butadiene conversion. Hoffmann succeeded beyond Woodward’s expectations and rationalised the stereochemical outcome of all such ring openings regardless of the number of electrons. 45 Right away, the editor of Angewandte Chemie invited Woodward to write a review – a quite different reception to the earlier treatment of von Doering! Four additional communications would cover ‘no-mechanism’ reactions such as the Diels-Alder and the Cope and Claisen rearrangements. 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 Hoffmann had discovered a grand unified theory whereby the conservation of orbital symmetry was the key that unlocked all these disparate reactions. For example, correlation diagrams (Fig. 14) for the [4π + 2π] Diels-Alder indicate that all three bonding MOs in the two components correlate with bonding MOs in the product. Contrariwise, for the recalcitrant ethylene [2π + 2π] dimerization, an undesirable crossing occurs between a bonding MO in ethylene and an antibonding MO in the product cyclobutene. To explain these MO treatments, Woodward and Hoffmann had to invent their own terminology and introduce words such as electrocyclic, cycloaddition, sigmatropic, cheletropic, disrotatory, conrotatory, suprafacial, antarafacial, pericylic–now entrenched in the organic chemist’s vocabulary.

![Fig. 14:

The Woodward-Hoffmann correlation diagrams for [4π + 2π] and [2π + 2π] cycloadditions. “Reprinted with permission from Hoffmann, R.; Woodward, R. B. Selection rules for concerted cycloaddition reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (9), 2046–2048. Copyright 1965 American cChemical society.” The frontier MO approach is shown side by side for comparison.](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2025-0534/asset/graphic/j_pac-2025-0534_fig_014.jpg)

The Woodward-Hoffmann correlation diagrams for [4π + 2π] and [2π + 2π] cycloadditions. “Reprinted with permission from Hoffmann, R.; Woodward, R. B. Selection rules for concerted cycloaddition reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (9), 2046–2048. Copyright 1965 American cChemical society.” The frontier MO approach is shown side by side for comparison.

In a series of publications starting in 1952, Kenichi Fukui in Kyoto showed that frontier orbitals i.e. the highest occupied (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied (LUMO) are the most important to consider in transition states. 50 , 51 Finally, here was a QM interpretation of organic reactions in which orbitals of the correct three-dimensional shape could replace planar curly arrows! This simplified Hoffmann’s full correlation diagrams, as consideration of the frontier orbital symmetry was sufficient (Fig. 14) and immediately informs us that the HOMO-LUMO interaction for the [4π + 2π] cycloaddition is in phase and attractive while nonbonding for the [2π + 2π] reaction.

By the end of 1965, Woodward had finally received the coveted Nobel prize “for his outstanding achievements in the art of organic synthesis” while the Woodward-Hoffmann rules had reduced all ‘no-mechanism’ reactions to a mathematical proof: ‘A ground-state pericyclic reaction is symmetry-allowed when the total number of (4q + 2)s and (4r)a components is odd.’ The global response to the rules was immediate and enthusiastic. While Woodward was often lethargic in his writing, Hoffmann, now an untenured assistant professor, needed publications and put together an extended review in reply to the Angewandte Chemie invitation. The editors waived their normal restrictions on size, with the ensuing printed version consuming over 70 pages. 52 The popularity was such that it was immediately published separately in book form in English and German. Towards the end, Woodward and Hoffmann famously state, ‘Violations. There are none! Nor can violations be expected of so fundamental a principle of maximum bonding.’ Generations of chemists have admired Hoffmann’s lucid introduction to molecular orbitals followed by his detailed derivation of the Woodward-Hoffmann rules, supplemented by supporting literature examples and theoretical predictions. I began this account with color, and the Woodward and Hoffmann review brings us full circle with its spectacular use of vivid blue and green for MO diagrams.

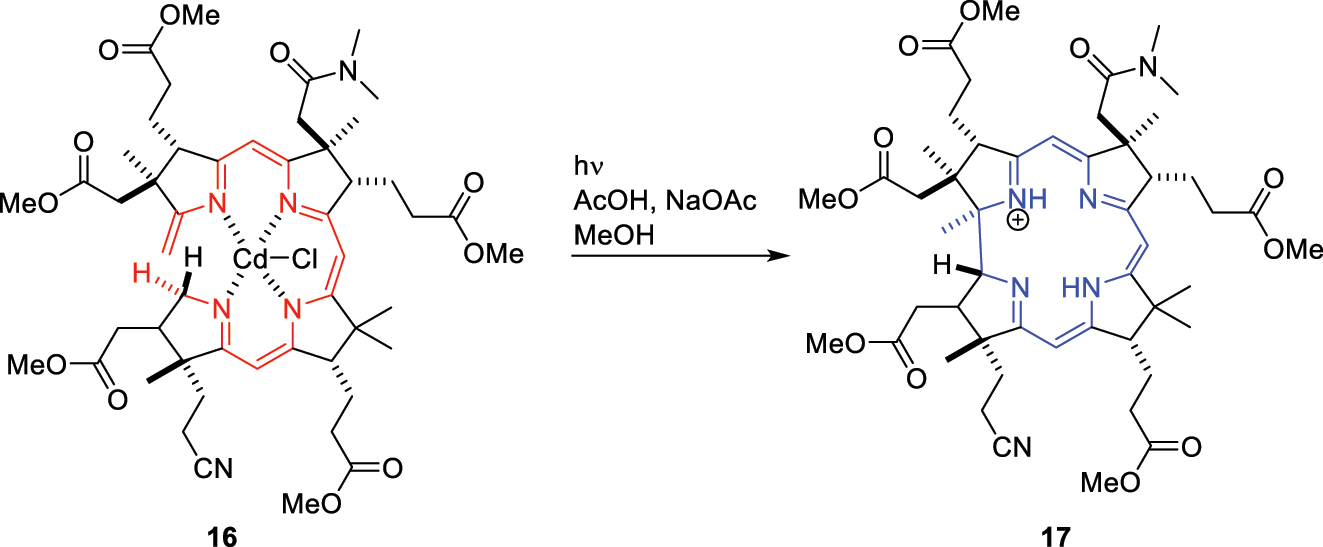

Fittingly, the vitamin B12 total synthesis that occupied Woodward and his Swiss collaborator Albert Eschenmoser for over a decade involved a demonstration of the Woodward-Hoffmann rules in one of its key steps. The corrin macrocyle was produced by the metal templated photochemical isomerization of 16 (Fig. 15) to 17 – a 1,16 antarafacial hydrogen shift that is symmetry forbidden thermally and allowed photochemically! 48 Given the impact of the Woodward-Hoffmann rules upon organic chemistry, Woodward must have been optimistic about his chances for a second Nobel prize. His unfortunate passing in 1979 meant that only Hoffmann and Fukui would share the honors in 1981.

The antarafacial 1,16 hydrogen shift en route to vitamin B12 total synthesis.

Summary

It is easy to categorise Woodward as the grandmaster of complex molecule synthesis, and indeed that was the citation for his Nobel Prize, but he was much more in the breadth of his activity and his influence on the community. Always, there was the quest to comprehend experimental facts and glean general principles of broad scope and predictive power. QM may not have come to Woodward, but Woodward unquestionably came to QM (Table 1). Energy transitions and molecular orbitals were central to the Woodward rules for UV-visible absorption, the octant rule for chiral ketones and the Woodward-Hoffmann rules for pericyclic reactions.

The timeline of Woodward’s involvement with molecular orbitals. The year 1965 was undoubtedly a felicitous one.

| Year | Publication |

|---|---|

| 1941 | The Woodward rules for the UV-absorption of conjugated ketones |

| 1942 | Charge transfer mechanism for the Diels-Alder reaction |

| 1945 | Woodward’s first curly arrow mechanism |

| 1952 | The structure of ferrocene and its aromaticity |

| 1955 | Delocalisation in the homoallylic 7-norbornenyl carbocation |

| 1961 | The octant rule for optical rotatory dispersion curves |

| 1965 | Woodward’s first NMR spectrum |

| 1965 | The Woodward-Hoffmann rules for pericyclic reactions |

| 1965 | The Nobel prize |

| 1969 | Woodward and Hoffmann’s review in Angewandte Chemie |

In the field of structure elucidation, Woodward would be delighted by the current combination of 2D-NMR experiments and high-resolution mass spectrometry to assign the complete structure of complex natural products from μg quantities and equally impressed by the accuracy of theoretical simulation of NMR spectra. As a fan of games and puzzles, Woodward would enjoy Google DeepMind’s creation of a program that teaches itself chess to a level where it outplays any human, and how the same team’s AlphaFold performs de novo prediction of protein structures (Denis Hassabis and John Jumper, Nobel Prize 2024). There is a clear ‘night and day’ difference between organic chemistry before and after the Woodward-Hoffmann rules. Their success and broad scope vindicated the application of QM and MO theory to organic chemistry. Undergraduate students today will be fully aware of orbital geometry and the use of frontier orbitals to explain reaction mechanisms. In the research laboratory, the computational methods are ever more sophisticated with techniques such as density functional theory (DFT) and the modelling of noncovalent forces in protein-ligand binding for drug discovery. Woodward would undoubtedly agree that QM will continue to be at the forefront of chemical science as it enters its second century and produce further groundbreaking discoveries of both a theoretical and practical nature.

Acknowledgments

I thank the School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences at Liverpool John Moores University for their friendship and support.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Born, M. Über Quantenmechanik. Z. Phys. 1924, 26 (1), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01327341.Search in Google Scholar

2. Heisenberg, W. Über Quantentheoretische Umdeutung Kinematischer Und Mechanischer Beziehungen. Z. Phys. 1925, 33 (1), 879–893. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01328377.Search in Google Scholar

3. Benfey, O. T.; Morris, P. J. T. Robert Burns Woodward: Architect and Artist in the World of Molecules; Chemical Heritage Foundation: Philadelphia, 2001.Search in Google Scholar

4. Seeman, J. I. R. B. Woodward: A Larger-than-Life Chemistry Rock Star. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (34), 10228–10245. https://doi.org/10.1002/ANIE.201702635.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Seeman, J. I. Bumps in the Road: R. B. Woodward and his Years before Tenure. Tetrahedron 2023, 145, 133599. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TET.2023.133599.Search in Google Scholar

6. Hückel, E. Quantentheoretische Beiträge Zum Benzolproblem – I. Die Elektronenkonfiguration Des Benzols Und Verwandter Verbindungen. Z. Phys. 1931, 70 (3–4), 204–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01339530.Search in Google Scholar

7. Förster, T. Farbe und Konstitution Organischer Verbindungen vom Standpunkt der Modernen Physikalischen Theorie. Z. Elektrochem. Angew. Phys. Chem. 1939, 45 (7), 548–573. https://doi.org/10.1002.10.1002/bbpc.193900065Search in Google Scholar

8. Berson, J. A. Erich Hückel, Pioneer of Organic Quantum Chemistry: Reflections on Theory and Experiment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996, 35 (23–24), 2750–2764. https://doi.org/10.1002/ANIE.199627501.Search in Google Scholar

9. Karrer, P. Organic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: New York, 1947.Search in Google Scholar

10. Dannenberg, H. Über die Ultraviolettabsorption der Steroide; Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften: Berlin, 1940.Search in Google Scholar

11. Woodward, R. B. Structure and the Absorption Spectra of α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63 (4), 1123–1126. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01849A066.Search in Google Scholar

12. Woodward, R. B.; Clifford, A. F. Structure and Absorption Spectra. II. 3-Acetoxy-Δ5-(6)-nor-Cholestene-7-Carboxylic Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63 (10), 2727–2729. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01855A063.Search in Google Scholar

13. Woodward, R. B. Structure and Absorption Spectra. III. Normal Conjugated Dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1942, 64 (1), 72–75. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01253A018.Search in Google Scholar

14. Woodward, R. B. Structure and Absorption Spectra. IV. Further Observations on α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1942, 64 (1), 76–77. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01253A019.Search in Google Scholar

15. Seeman, J. I. R. B. Woodward, a Great Physical Organic Chemist. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2014, 27 (9), 708–721. https://doi.org/10.1002/POC.3328.Search in Google Scholar

16. Fieser, L. F.; Fieser, M.; Rajagopalan, S. Absorption Spectroscopy and the Structures of the Diosterols. J. Org. Chem. 1948, 13 (6), 800–806. https://doi.org/10.1021/JO01164A003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Hochstein, F. A.; Stephens, C. R.; Conover, L. H.; Regna, P. P.; Pasternack, R.; Gordon, P. N.; Pilgrim, F. J.; Brunings, K. J.; Woodward, R. B. The Structure of Terramycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75 (22), 5455–5475. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01118A001.Search in Google Scholar

18. Woodward, R. B.; Sondheimer, F.; Taub, D.; Heusler, K.; McLamore, W. M. The Total Synthesis of Steroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74 (17), 4223–4251. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01137A001.Search in Google Scholar

19. Djerassi, C. Steroids Made it Possible; American Chemical Society: Washington, 1990.Search in Google Scholar

20. Hatanaka, M.; Sayama, D.; Miyasaka, M. Optical Activities of Steroid Ketones – Elucidation of the Octant Rule. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2018, 200, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SAA.2018.04.030.Search in Google Scholar

21. Moffitt, W.; Woodward, R. B.; Moscowitz, A.; Klyne, W.; Djerassi, C. Structure and the Optical Rotatory Dispersion of Saturated Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83 (19), 4013–4018. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01480A015.Search in Google Scholar

22. Woodward, R. B.; Weiler, L. S.; Dutta, P. C. The Structure of Magnamycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (20), 4662–4663. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA00948A058.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Kermack, W. O.; Robinson, R. LI.– An Explanation of the Property of Induced Polarity of Atoms and an Interpretation of the Theory of Partial Valencies on an Electronic Basis. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 1922, 121 (0), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1039/CT9222100427.Search in Google Scholar

24. Rây, J. N.; Robinson, R. CCXII – The Nitration of m-Meconine. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 1925, 127 (0), 1618–1623. https://doi.org/10.1039/CT9252701618.Search in Google Scholar

25. Wheland, G. W. Advanced Organic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, 1949.Search in Google Scholar

26. Lea, T. R.; Robinson, R. CCCXIII – The Fission of Some Methoxylated Benzophenones. J. Chem. Soc. 1926, 129, 2351–2355. https://doi.org/10.1039/JR9262902351.Search in Google Scholar

27. Bradley, W.; Robinson, R. CLXXIV – The Interaction of Benzoyl Chloride and Diazomethane Together with a Discussion of the Reactions of the Diazenes. J. Chem. Soc. 1928, 1310–1318. https://doi.org/10.1039/JR9280001310.Search in Google Scholar

28. Woodward, R. B.; Doering, W. E. The Total Synthesis of Quinine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66 (5), 849. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01233A516.Search in Google Scholar

29. Woodward, R. B.; Doering, W. E. The Total Synthesis of Quinine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1945, 67 (5), 860–874. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01221A051.Search in Google Scholar

30. Kealy, T. J.; Pauson, P. L. A New Type of Organo-Iron Compound. Nature 1951, 168 (4285), 1039–1040. https://doi.org/10.1038/1681039B0.Search in Google Scholar

31. Wilkinson, G.; Rosenblum, M.; Whiting, M. C.; Woodward, R. B. The Structure of Iron Bis-Cyclopentadienyl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74 (8), 2125–2126. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01128A527.Search in Google Scholar

32. Fischer, E. O.; Pfab, W. Cyclopentadien-Metallkomplexe Ein Neuer Typ Metallorganischer Verbindungen. Z. Naturforsch., B: J. Chem. Sci. 1952, 7 (7), 377–379. https://doi.org/10.1515/ZNB-1952-0701.Search in Google Scholar

33. Woodward, R. B.; Rosenblum, M.; Whiting, M. C. A New Aromatic System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74 (13), 3458–3459. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01133A543.Search in Google Scholar

34. Winstein, S.; Shatavsky, M.; Norton, C.; Woodward, R. B. 7-Norbornenyl and 7-Norbornyl Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77 (15), 4183–4184. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01620A078.Search in Google Scholar

35. Woodward, R. B. The Mechanism of the Diels-Alder Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1942, 64 (12), 3058–3059. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01264A521.Search in Google Scholar

36. Woodward, R. B.; Baer, H. Studies on Diene-Addition Reactions. II. the Reaction of 6,6-Pentamethylenefulvene with Maleic Anhydride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66 (4), 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01232A042.Search in Google Scholar

37. Evans, M. G. The Activation Energies of Reactions Involving Conjugated Systems. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1939, 35, 824–834. https://doi.org/10.1039/TF9393500824.Search in Google Scholar

38. Woodward, R. B.; Katz, T. J. The Mechanism of the Diels-Alder Reaction. Tetrahedron 1959, 5 (1), 70–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(59)80072-7.Search in Google Scholar

39. Dewar, M. J. S. Mechanism of the Diels-Alder Reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1959, 1 (4), 16–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(01)82720-9.Search in Google Scholar

40. Houk, K. N.; Liu, F.; Yang, Z.; Seeman, J. I. Evolution of the Diels–Alder Reaction Mechanism Since the 1930s: Woodward, Houk with Woodward, and the Influence of Computational Chemistry on Understanding Cycloadditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (23), 12660–12681. https://doi.org/10.1002/ANIE.202001654.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Vermeeren, P.; Hamlin, T. A.; Bickelhaupt, F. M. Origin of Asynchronicity in Diels – Alder Reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23 (36), 20095–20106. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1CP02456F.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. E Doering, W. V.; Roth, W. R.; Roth, W. R. The Overlap of Two Allyl Radicals or a Four-Centered Transition State in the Cope Rearrangement. Tetrahedron 1962, 18 (1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(62)80025-8.Search in Google Scholar

43. Streitwieser, A.Jr. Molecular Orbital Theory for Organic Chemists; Wiley: New York, 1961.10.1149/1.2425396Search in Google Scholar

44. Seeman, J. I. Why Woodward and Hoffmann? and Why 1965?**. Chem. Record 2023, 23 (1), e202200239. https://doi.org/10.1002/TCR.202200239.Search in Google Scholar

45. Woodward, R. B.; Hoffmann, R. Stereochemistry of Electrocyclic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (2), 395–397. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01080A054.Search in Google Scholar

46. Hoffmann, R.; Woodward, R. B. Selection Rules for Concerted Cycloaddition Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (9), 2046–2048. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01087A034.Search in Google Scholar

47. Woodward, R. B.; Hoffmann, R. Selection Rules for Sigmatropic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (11), 2511–2513. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA01089A050.Search in Google Scholar

48. Hoffmann, R.; Woodward, R. B. Orbital Symmetries and Endo-Exo Relationships in Concerted Cycloaddition Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (19), 4388–4389. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA00947A033.Search in Google Scholar

49. Hoffmann, R.; Woodward, R. B. Orbital Symmetries and Orientational Effects in a Sigmatropic Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87 (19), 4389–4390. https://doi.org/10.1021/JA00947A034.Search in Google Scholar

50. Fukui, K.; Yonezawa, T.; Shingu, H. A Molecular Orbital Theory of Reactivity in Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 1952, 20 (4), 722–725. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1700523.Search in Google Scholar

51. Seeman, J. I. Kenichi Fukui, Frontier Molecular Orbital Theory, and the Woodward-Hoffmann Rules. Part II. A Sleeping Beauty in Chemistry†**. Chem. Record 2022, 22 (4), e202100300. https://doi.org/10.1002/TCR.202100300.Search in Google Scholar

52. Woodward, R. B.; Hoffmann, R. The Conservation of Orbital Symmetry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1969, 8 (11), 781–853. https://doi.org/10.1002/ANIE.196907811.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 IUPAC & De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Recommendations

- Experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data (IUPAC Recommendations 2025)

- IUPAC Technical Reports

- Kinetic parameters for thermal decomposition of commercially available dialkyldiazenes (IUPAC Technical Report)

- FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collections – advice for researchers, authors, and data managers (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Review Articles

- Are the Lennard-Jones potential parameters endowed with transferability? Lessons learnt from noble gases

- Quantum mechanics and human dynamics

- Quantum chemistry and large systems – a personal perspective

- The organic chemist and the quantum through the prism of R. B. Woodward

- Relativistic quantum theory for atomic and molecular response properties

- A chemical perspective of the 100 years of quantum mechanics

- Methylene: a turning point in the history of quantum chemistry and an enduring paradigm

- Quantum chemistry – from the first steps to linear-scaling electronic structure methods

- Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics on quantum computers: challenges and opportunities

- Research Articles

- Alzheimer’s disease – because β-amyloid cannot distinguish neurons from bacteria: an in silico simulation study

- Molecular electrostatic potential as a guide to intermolecular interactions: challenge of nucleophilic interaction sites

- Photophysical properties of functionalized terphenyls and implications to photoredox catalysis

- Combining molecular fragmentation and machine learning for accurate prediction of adiabatic ionization potentials

- Thermodynamic and kinetic insights into B10H14 and B10H14 2−

- Quantum origin of atoms and molecules – role of electron dynamics and energy degeneracy in atomic reactivity and chemical bonding

- Clifford Gaussians as Atomic Orbitals for periodic systems: one and two electrons in a Clifford Torus

- First-principles modeling of structural and RedOx processes in high-voltage Mn-based cathodes for sodium-ion batteries

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Furanyl-Chalcones as antimalarial agent: synthesis, in vitro study, DFT, and docking analysis of PfDHFR inhibition

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Recommendations

- Experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data (IUPAC Recommendations 2025)

- IUPAC Technical Reports

- Kinetic parameters for thermal decomposition of commercially available dialkyldiazenes (IUPAC Technical Report)

- FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collections – advice for researchers, authors, and data managers (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Review Articles

- Are the Lennard-Jones potential parameters endowed with transferability? Lessons learnt from noble gases

- Quantum mechanics and human dynamics

- Quantum chemistry and large systems – a personal perspective

- The organic chemist and the quantum through the prism of R. B. Woodward

- Relativistic quantum theory for atomic and molecular response properties

- A chemical perspective of the 100 years of quantum mechanics

- Methylene: a turning point in the history of quantum chemistry and an enduring paradigm

- Quantum chemistry – from the first steps to linear-scaling electronic structure methods

- Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics on quantum computers: challenges and opportunities

- Research Articles

- Alzheimer’s disease – because β-amyloid cannot distinguish neurons from bacteria: an in silico simulation study

- Molecular electrostatic potential as a guide to intermolecular interactions: challenge of nucleophilic interaction sites

- Photophysical properties of functionalized terphenyls and implications to photoredox catalysis

- Combining molecular fragmentation and machine learning for accurate prediction of adiabatic ionization potentials

- Thermodynamic and kinetic insights into B10H14 and B10H14 2−

- Quantum origin of atoms and molecules – role of electron dynamics and energy degeneracy in atomic reactivity and chemical bonding

- Clifford Gaussians as Atomic Orbitals for periodic systems: one and two electrons in a Clifford Torus

- First-principles modeling of structural and RedOx processes in high-voltage Mn-based cathodes for sodium-ion batteries

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Furanyl-Chalcones as antimalarial agent: synthesis, in vitro study, DFT, and docking analysis of PfDHFR inhibition