Abstract

The surface electrostatic potential (V S (r)) is an established tool for characterization and prediction of sites susceptible to participate in intermolecular interactions. In particular, maxima in V S (r) (V S,max ) have been shown to reflect σ-holes and π-holes, including the electrophilic sites of hydrogen bond donors and halogen bond donors as well as traditional Lewis acids. The characterization of nucleophilic sites on Lewis bases has proven more difficult, and surface minima (V S,min ) often fail to predict the angular direction of interactions with electrophiles. In this study, it is demonstrated that the predictive capacity of spatial minima in the electrostatic potential (V min ) is much higher than V S,min for interactions with neutral electrophiles, such as HF, BF3, BrF and LiF. V S,min , on the other hand, is better for interactions with ionic electrophiles, such as Li+. This latter observation can be explained by that the position of the V S,min corresponds to the site on the surface that has strongest electrostatic interaction with a point charge. V min performs better for interactions with neutral electrophiles, as the nucleophile interacts electrostatically with the entire charge distribution of the electrophile and not only with that of its electrophilic site; the charge distribution of a neutral electrophile can be approximated by a dipole or a superposition of dipoles, and a dipole interacting with a Lewis base (nucleophile) has its lowest electrostatic energy when it is pointed along the direction of strongest electrostatic field, which generally coincides with the direction of the V min .

Introduction

This year (2025) is the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ) in recognition of the 100-year anniversary of the initial development of quantum mechanics. Already in 1929 Paul Dirac, one of the pioneers in quantum theory development, stated: The underlying physical laws necessary for the mathematical theory of a large part of physics and the whole of chemistry are thus completely known, and the difficulty is only that the application of these laws leads to equations much too complicated to be soluble. 1

In 1998 the Nobel committee of chemistry, when awarding the Nobel Prize of Chemistry to Walter Kohn and John Pople, found that Dirac’s statement had been overly pessimistic and stated: Things began to move at the beginning of the 1960s when computers came into use for solving these equations and quantum chemistry (the application of quantum mechanics to chemical problems) emerged as a new branch of chemistry. As we approach the end of the 1990s we are seeing the result of an enormous theoretical and computational development, and the consequences are revolutionising the whole of chemistry. 2

This development has continued and today we are able to compute highly accurate wavefunctions and energies for most chemical systems. Instead it has become apparent that the main problem no longer lies in solving the complicated equations defined by quantum theory but rather to interpret the increasingly complex wavefunctions that result from the solving in terms relevant for the understanding of chemistry. It is illustrative that the two most commonly used quantum based explanatory models in chemistry still are the periodic table of the elements and the drawing of Lewis structures, 3 , 4 including the latter’s extensions to resonance structures and curly arrow pushing. 5 , 6 These models, which are simple to use but convey important chemical information, have solid foundations in quantum theory although being introduced before the advent of quantum mechanics.

In the field of non-covalent interactions, the surface electrostatic potential (V S (r)) has emerged as a widely used tool for extracting information of complex quantum chemical calculations to understand and characterize interaction sites of molecules. It was first introduced in the 1990s in the research group of Peter Politzer, 7 and some of the first applications were biological recognition interactions and hydrogen bonding. 8 , 9 In 1992 Brinck et al. demonstrated that the capacity of halocarbons to interact with Lewis bases can be explained by a tip of positive V S (r) at the end of the halogen atom opposite to the carbon halogen bond. 10 This finding was ignored until the boom of halogen bonding in the beginning of the 21st century when it was realized that the surface electrostatic potential can be an effective tool for characterizing halogen bond donating sites. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20

The relevance of V S (r) was cemented in 2007 when Clark et al. provided an orbital-based rationale for the electron deficiency at the tip of the halogen atom and the resulting maximum in V S (r) (V S,max ); according to this rationale the positive tip can be called a σ-hole because of the polarization of the σ-orbital density away from this region towards the C–X bond. 21 The σ-hole concept was later expanded to other main-group elements, and has given rise to a wide range of new interactions named after the corresponding group of the periodic table, e.g. chalcogen, tetrel, and pnictogen bonding. 18 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 The term π-hole was introduced to describe surface electrostatic potential maxima at positions that are located perpendicular to a planar molecular framework. 25 , 27 More recently the concepts of σ-hole and π-hole bonding and the relevance of positive V S (r) regions for interactions with Lewis bases has been extended to transition metal-based compounds, as pioneered by Brinck and coworkers. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33

Even though the surface electrostatic potential (V S (r)) originally was developed to characterize sites that interact with electrophiles and Lewis acids as well as sites that interact with nucleophiles and Lewis bases, it is clearly the latter application that has been dominating. This is apparent from the extended use of V S (r) maxima (V S,max ) as indicators of σ-holes and π-holes. The minima in V S (r) (V S,min) should in a similar manner be indicative of sites that interact with Lewis acidic sites, e.g. σ-holes and π-holes, but such examples are less common in the literature. The reason is probably that Lewis basic (nucleophilic) sites are more challenging to characterize and their location depends on the Lewis acid/electrophile. As an example, acetone has two equal minima in the surface electrostatic potential (V S,min ) close to the top of the O, at angle of around 160° with the C–O bond, while hydrogen bond donors and most other σ- and π-hole donors bind at an angle of 120–130°. This angle is in better agreement with the angle of the spatial minima of the electrostatic potential (V min ).

Similar observations have also been made for the interactions of weak halogen bond donors, i.e. dihalogens, in that the angular direction of interactions with Lewis bases is better described by V min than V S,min . 34 , 35 However, metal cations, e.g. Li+, bind acetone at an angle of nearly 180°, in relatively good agreement with the angle of the V S,min . 35 In a similar way as for the prediction of the positions of hydrogen bond accepting sites, the V min has also been shown to more accurate than the V S,min for predicting the strength of hydrogen bonding; it has been shown for families of hydrogen bond acceptors that there are better correlations between V min and the hydrogen bond strength than between V S,min and hydrogen bond strength. 9 , 36

In this work we have analyzed a number of intermolecular interactions between electrophiles (Lewis acids) and nucleophiles (Lewis bases) and attempted to understand how and why the location of the site for the interaction with the electrophile is dependent on the character of the electrophile.

Methodological background

The electrostatic potential (V(r) that surrounds a molecule is rigorously defined by.

where Z A is the charge of nucleus A located at R A. V(r) is a physical observable that can be determined from an experimental or theoretical density distribution function. It is a first order property and thus it is relatively insensitive to the computational method. qV(r) gives the interaction energy between the unperturbed charge distribution of the molecule and a point charge q located at r.

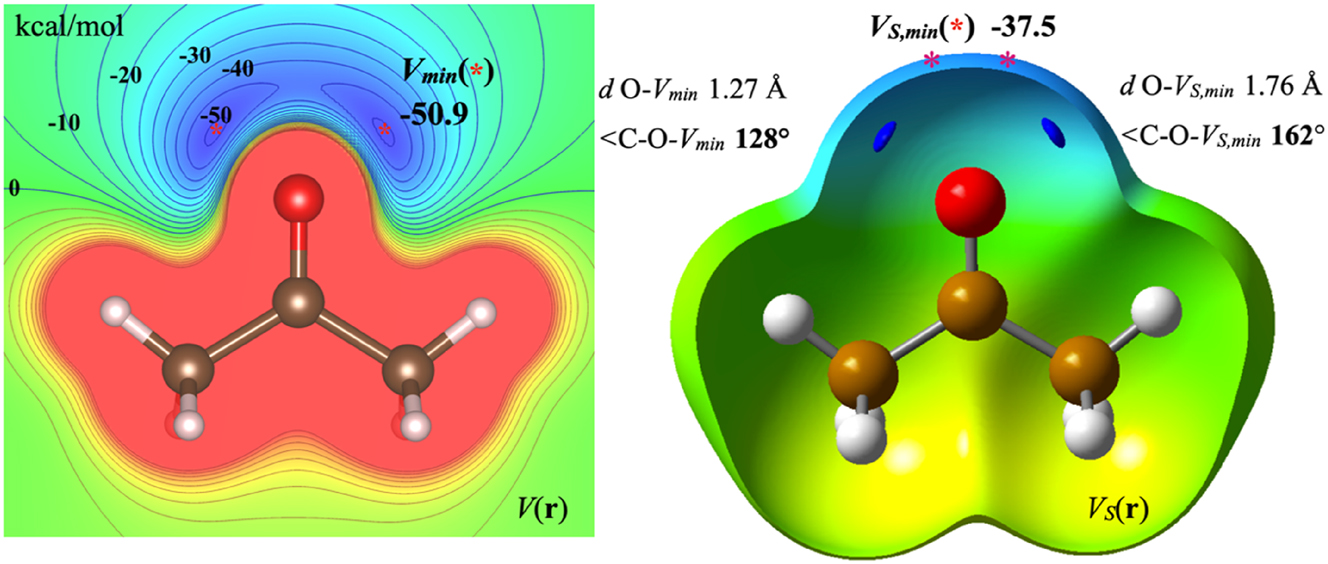

The electrostatic potential of an atom is everywhere positive and decrease asymptotically towards zero with increasing distance from the nucleus. When a molecule is formed from atoms the electron density is redistributed leading to regions of negative V(r) with the minima (V min ) typically located above π-bonds or at lone pair regions. As an example, V(r) of acetone depicted in the plane of the heavy atoms is shown in Fig. 1. There are two equal V min at positions corresponding to the lone pairs. These also reflect sites susceptible toward interaction with electrophiles or Lewis acids. 9 , 37 There are no corresponding maxima in V(r) as the most positive regions are found at the nuclei where V(r) goes toward infinity. The nuclear positions are not sites for interaction with electrophiles, as the electron density of the approaching electrophile will be repelled by the electron density of the nucleophile before reaching the nucleus.

On the left, V(r) in the molecular plane of acetone with V min labeled by *. On the right, V S (r) on the 0.001 au isodensity surface with V S,min labeled by *. The V min positions, which are located inside of the 0.001 au surface, are here indicated blue envelopes that encompasses the V min . Similar coloring schemes are used for both V(r) and V S (r) with the most negative areas being deep blue whereas the most positive are read. Note that 1 kcal/mol is equal to 4.184 kJ/mol.

In 1989, Sjoberg and Politzer recognized that the conundrum of identifying electrophilic sites from the electrostatic potential could be solved by computing and plotting V(r) on a molecular surface defined by constant electron density, resulting in a surface electrostatic potential (V S (r)). 7 Typically the 0.001 or 0.002 a.u. contours are used and the corresponding surfaces are at distances from the nuclei that are close to the van der Waals radii of the corresponding elements. 35 Such a surface is expected to have a nearly constant repulsive potential, and therefore the maxima in V S (r) (V S,max ) can be used to locate the sites most susceptible to interact with nucleophiles in interactions dominated by electrostatics. 32 This approach has proven highly successful as evidenced by the general adoption of V S,max as indicators of σ-hole and π-hole donating sites.

Sjoberg and Politzer intended the surface minima (V S,min ) to serve a similar purpose for identifying sites susceptible to interact with electrophiles, or in today’s vocabular to identify σ-hole accepting sites. The left part of Fig. 1 shows the V S (r) at the 0.001 density contour for acetone. Similarly to the V min , there are two V S,min outside the oxygen in the same plane as the heavy atoms. However, each V S,min is located at an angle of 162° with the C-O bond, and the V S (r) value at the top of O (at 180° angle) is less than 0.1 kcal/mol higher, showing the small variation of V S (r) close to top of the O. However as already mentioned, this location is not representative of the interaction site of many electrophiles, such as hydrogen bond and halogen bond donors, but is close to the interaction site of metal cations. In the figure of V S (r) we also show the locations of the V min , which are found well inside the volume of the 0.001 contour at an angle of 128° with the C–O bond.

Results and discussion

Interactions of acetone

We will begin by analyzing complexes between acetone and few electrophiles, i.e. Lewis acids and/or σ-hole donors, and try to relate their geometries to the spatial distribution of the electrostatic potential as well as the surface electrostatic potential (Fig. 2). Beginning with the HF complex, we note that the hydrogen of HF interacts with the lone pair of O of acetone at a C–O–H angle of 118°, which is slightly smaller than the C–O–V min angle (128°) and much smaller than the C–O–V S,min angle of 162°. Furthermore, the F atom is slightly tilted towards the CH3 group of acetone at an O–H–F angle of 170°. It can also be noted that the H atom is located inside of the van der Waals volume as defined by the 0.001 au contour, but it is further away from the O atom than the V min . Thus, it is not obvious why the C–O–H angle is much closer to the C–O–V min angle than it is to the C–O–V S,min angle.

Turning towards acetone-BF3 complex, we find that the C–O–B angle (128°) is in perfect agreement with the C–O–V min (128°), and thus much smaller than C–O–V S,min angle (162°). The short O–B distance of 1.65 Å is indicative of a dative covalent bond and the B is located inside the 0.001 au contour but the bond is significantly longer than the O–V min distance.

Optimized structures of complexes between acetone and different electrophiles. All neutral complexes interact with similar angular directions as the C–O–V min angle.

The two halogen bonded complexes acetone-BrF and acetone-Br2 are very similar in their angular orientation. The C–O–Br angles are 128° and 126°, respectively, in both cases in close agreement with the C–O–V min (128°). The O–Br–X angle is for both almost 180°, in agreement with earlier observations that the halogen bond is more directional in character than the halogen bond (compare with the corresponding 170° angle in the acetone-HF complex). It is noteworthy that the C–O–Br angle is close to the C–O–V min angle in both complexes, even though the O–Br distance is much longer in the Ace-Br2 complex. This confirms the previous observation that there is no correlation between how close the intramolecular angle, e.g. C–O–Br, is to the angle with V min and how close the σ-hole is to the V min position.

The Li+ forms a complex that is linear with the C–O bond, which means that the C–O–Li angle of 180° is larger than the C–O–V S,min angle of 162°. However, as previously discussed the V S (r) has a flat value distribution close to the top of O, and the top value at 180° deviates less than 0.1 kcal/mol from V S,min value. Kollman and Rothenberg already in 1977 identified that Li+ forms a nearly linear complex with many Lewis bases whereas the corresponding interaction with hydrogen bond donors is at an angle that agrees with the V min . 38 They argued that the reason is that exchange repulsion is important for determining the geometry of the Li+ complex, whereas its importance is smaller for the hydrogen bonded complexes, as the electron of hydrogen is polarized toward the electronegative atom. This could explain the better agreement with V S,min for the Li+ complex since V S (r) indirectly takes exchange repulsion into account by using a surface of constant electron density. However, if this rationale is correct then LiF should also form a complex with acetone with a linear C–O–Li bond/interaction, as there is no reason for the exchange repulsion to be of lower magnitude for complexes of LiF compared to Li+. Instead we find a C–O–Li angle of 126° in close agreement with the V min angle and the angles of the other complexes with neutral nucleophiles. An indication of why monatomic cations behave differently from neutral molecules is given by the position of F in the complex of acetone with LiF; the negative F is strongly tilted towards the region of positive V S (r) above the CH3 group. Thus, LiF is positioned to maximize the total electrostatic interaction with acetone, as represented by V S (r), and not only the interaction with the positive end, i.e. Li. In the case of a monoatomic cation, the V S,min position should be the most favorable position on the surface as V S (r) gives the electrostatic interaction energy with a unitary point charge. Neutral molecules, however, can often be approximated by a dipole or a collection of dipoles, and the interaction energy with a dipole is proportional to the electric field in the direction of the dipole. This can explain why the interaction angle with a σ-hole donor often coincides with the angle of the V min ; the electric field perpendicular to the surface is likely to be strongest outside of the V min .

Interactions of thioacetone

We have also analyzed how the directional binding preferences of thioacetone relates to the spatial and surface distributions of its electrostatic potential (Fig. 3). Looking first at V S (r) in a plane through the heavy atoms, we note that the overall picture is similar to that of acetone. However, the two lone pair V min are located at a smaller angle, 107° instead of 128°, and are less negative, −31.5 kcal/mol instead of −51.9 kcal/mol, in comparison to acetone. These differences are translated into V S (r) with the V S,min of thioacetone appearing at a much smaller angle compared to that of acetone, 114° instead of 162° and with value of −23.6 instead of −37.5 kcal/mol. In addition, the flat V S (r) of acetone at the angles close to 180° has no equivalence for thioacetone and V S (r) at 180° is as high as −6.8 kcal/mol.

In general, the binding directions of the different electrophiles relates to V min and V S,min in a similar manner as for acetone (Fig. 4). The HF molecule binds with a C–S–H angle (100°) that is slightly smaller than the C–S–V min angle and with the F slightly tilted towards the CH3 group in a similar manner as for acetone, i.e. he S–H–F angle is 168°. BF3 binds at an angle that nearly coincides with the C–S–V min angle, and that also holds for Br2. The Br2 is again found to interact with nearly linear conformation with respect to electrophilic site; the S–Br–Br angle is close to 180°, confirming the more localized σ-hole of halogen bond donors compared to the σ-hole of hydrogen bond donors, such as HF.

Optimized structures of complexes between thioacetone and different electrophiles. All neutral complexes interact with similar angular directions as the C–O–V min angle. Li+ interacts at an angle closer to the C–O–V S,min angle.

In the case of Li+, the position is again found to be determined by V S (r) with the C–S–Li angle (112°) in good agreement with the C–S–V S,min angle (114°). The interaction of LiF is again dramatically different from that of Li+ with LiF having a C–S–Li angle of 101°, which is almost equal to that of HF and smaller than the C–S–V min angle. In a similar manner as for the acetone•••LiF complex, the F is strongly tilted towards the positive V(r) above the CH3 and the O–Li–F angle is 129°. The corresponding angle on acetone•••LiF is 127°. These results show that the σ-hole on LiF is even more delocalized than the σ-holes of hydrogen bond donors. Furthermore, the strong tilt of LiF is in agreement with our conclusion that the geometry of the complex is optimized to maximize the electrostatic interaction between the entire charge distributions of the two interacting molecules; thus the negative F of LiF plays an important role in the interaction.

Interactions of hydrogen halides

To investigate if the observations that were made regarding the different angular preferences of cationic and neutral electrophiles are generally valid, we have also investigated some complexes where hydrogen fluoride and hydrogen chloride serve as nucleophiles or Lewis bases (Fig. 5). We will first consider V(r) and V S (r) of HF (Fig. 6). V(r) in a plane through the heavy atoms has two minima of −28.8 at 124° (H–F–V min ), but because of rotationally symmetry there is actually a continuous circle of minimum V(r) at 124° and a distance of 1.31 Å from F. V S (r) also has a continuous circle of minima but at 140° and at a value of −23.8 kcal/mol. Notably there is also a V S,max at the top of F, in other words a σ-hole. However, the V S,max at −22.7 kcal/mol is only 1.1 kcal/mol higher than the V S,min .

V(r) (left) and V S (r) (right) for HF (top) and HCl (bottom). The depiction is similar to Fig. 1 and Fig. 3 but the coloring scheme is shifted as the magnitude of the negative potential range is smaller than for acetone. Note also that the V min and V S,min each form a circle of minimum potential at constant angle with the H–X bond.

Optimized structures of complexes between HF and HCl as Lewis bases and ClF and Li+.

HF forms a weak halogen bonded complex with ClF that has been estimated from microwave spectroscopy to have an H–F–Cl angle of 125° (±5°) angle and an F–Cl distance of 2.76 Å. 39 Our computed structure has an angle of 121° and a distance of 2.62 Å. Considering that the experimental structure includes the lengthening due to anharmonicity of the weak intermolecular Cl–F interaction, the agreement is good. Notably a previous computation at the MP2/6–311++G (2d,p) level resulted in an angle of 125° and a distance of 2.75 Å in almost perfect agreement with experiment. 34 The experimental estimate as well as the M06-2X and MP2 predictions for the angle are in very good agreement with the V min angle, confirming that V min accurately predicts the angle of interactions with neutral electrophiles.

The lithium cation forms a strong complex with HF at a Li–FH angle of 180°. Thus, this can technically be viewed as an interaction between two σ-holes, one on each reactant. However, as already mentioned, the V S,max at the top of F is negative and only 1.1 kcal/mol higher than the V S,min at 140°. The polarizability is expected to be significantly higher along the H–F bond than perpendicular to it, and thus the preference for a linear complex is most likely due to a larger polarization contribution to the intermolecular interaction at the 180° angle; this compensates for the slightly weaker electrostatic interaction. We also investigated the interaction between HF and LiF, but it results in the reorganization of the structure into a complex between Li+ and the symmetric (FHF)-.

We finally turn towards the HCl molecule. When comparing V(r) and V S (r) of HCl with those of HF, we see similar changes in the locations of the minima as when going from acetone to thioacetone. The V min of HCl is at a smaller angle (106°) than that of HF and the V S,min is at an angle (108°) that is much closer to the angle of V min than is the case for HF. There is also a much larger difference between the V S,top and V S,min value for HCl than for HF. HCl, in contrast to HF, has a well-developed σ-hole at the end position with a positive V S,max of 5.1 kcal/mol. ClF forms a weak complex with a similar but slightly shorter angle (101°) than the H–F–V min angle. Li+, however, forms a strong complex with an angle (108°) that similarly to thioacetone coincides with the V S,min angle.

Conclusions

Neutral σ-hole and π-hole donors (electrophiles) generally interact with a Lewis basic (nucleophilic) site at an angle that closely corresponds to the angle of the V min . We have shown that this holds for the full spectrum of polar interactions ranging from weak halogen bond interactions via hydrogen bonds to strong dative covalent interactions. The angle of the V min is always smaller than the corresponding angle of the V S,min and it is close to the angular direction where one intuitively would expect to find a lone pair. The rationale for the better agreement with the angle of V min than V S,min is that the charge distribution of the Lewis base, as represented by its electrostatic potential, interacts electrostatically with the entire charge distribution of the electrophile and not only with its electrophilic site. The charge distribution of most neutral electrophilic molecules can be approximated by a dipole or a superposition of dipoles, and a dipole interacting with the Lewis base has its lowest electrostatic energy when it is pointed along the direction of strongest electrostatic field, which generally coincides with the direction of the V min . Further support for the rationale of strongest total electrostatic interaction can be seen in the intermolecular interactions of molecules such as LiF that has a wide and delocalized σ-hole on the electrophilic site, e.g. Li. They form complexes where the negative end (e.g. F) of the molecule is tilted toward a region of positive potential outside the other molecule, as such a geometry strengthens the favorable electrostatic interaction between the two molecules. On the other hand, monoatomic cations, like Li+, generally interact with Lewis bases in a direction that is aligned with the V S,min . This is not surprising as the V S,min corresponds to the position on the surface that has the strongest electrostatic interaction with a positive point charge. In some cases where two V S,min are close in space, i.e. at angles close to 180°, it can be more favorable for the electrophilic site to interact at angle of 180° as this leads to a stronger polarization contribution to the interaction. Overall this study confirms the importance of electrostatics for determining the geometry of intermolecular interactions, even for interactions where other energy terms provide the main stabilizing effect, such as dative covalent bonds and some charge shift bonds.

Computational methods

The geometrical structures of molecules and molecular complexes have been computed at the M06-2X/6-31+G (d,p) level using the Gaussian 16 suite of programs. 40 The M06-2X functional is highly accurate for main-group chemistry, including noncovalent interactions, and it has been parameterized to include short and medium range London dispersion. Di Labio et al. evaluated non-counterpoise-corrected DFT interaction energies against a revision of the HB23 data set, and found the M06-2X functional to perform well with a mean absolute deviation of only 0.21 kcal mol−1 41 A polarized valence-double zeta basis set augmented with diffuse functions is generally sufficient for computing geometries of intermolecular complexes when used together with a hybrid DFT functional, and we found minimal changes in geometrical parameters going from the 6-31+G (d,p) basis set to the much larger jun-cc-pVTZ basis set.

Electron densities for the analysis of V(r) and V S (r) were also computed at the M06-2X/6-31+G (d,p) level of theory. V(r) is a first order property and as such less sensitive to the computational level than geometries or energies. As an example, V(r) for several of the molecules of this study had previously been analyzed using Hartree–Fock and a smaller basis set, but the angular directions of the V min are in almost perfect agreement between the studies. 34 V(r) was computed using Gaussian16 and V S (r) using hs95 (ver.230419) of Brinck. 32 Visualization of V(r) and V S (r) was done using Vesta and Gaussview, respectively. 42 , 43

Funding source: Vetenskapsrådet

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021-05881

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the late Peter Politzer, a pioneer of quantum chemistry and the use of the electrostatic potential to understand chemical interactions. Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (VR) grant number 2021-05881 is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Swedish Research Council (VR) grant number 2021-05881.

-

Data availability: Available from author upon reasonable request.

References

1. Dirac, P. A. M. Quantum Mechanics of Many-Electron Systems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1929, 123, 714–733.10.1098/rspa.1929.0094Search in Google Scholar

2. Press Release for Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1998; The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: Stocholm, Sweden, 1998; https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1998/press-release/ Search in Google Scholar

3. Mendeleyev, D. I. Mendeleyev’s Periodic Table of the Elements; Tip. t-va “Obshchestvenna͡i͡a polʹza: Saint Petersburg, Russia (Federation), 1871; https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/9c67wp122 Search in Google Scholar

4. Lewis, G. N. The Atom and the Molecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1916, 38 (4), 762–785. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja02261a002.Search in Google Scholar

5. Kermack, W. O. R.; Robert, L. I. An Explanation of the Property of Induced Polarity of Atoms and an Interpretation of the Theory of Partial Valencies on an Electronic Basis. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 1922, 121, 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1039/ct9222100427.Search in Google Scholar

6. Pauling, L.; Wilson, E. B. J. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics; McGraw- Hill Book Co: New York, 1935.Search in Google Scholar

7. Sjoberg, P.; Politzer, P. Use of the Electrostatic Potential at the Molecular Surface to Interpret and Predict Nucleophilic Processes. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94 (10), 3959–3961; https://doi.org/10.1021/j100373a017.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sjoberg, P.; Murray, J. S.; Brinck, T.; Evans, P.; Politzer, P. The Use of the Electrostatic Potential at the molecular-surface in Recognition Interactions - dibenzo-p-dioxins and Related Systems. J. Mol. Graph. 1990, 8 (2), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0263-7855(90)80086-U.Search in Google Scholar

9. Murray, J. S.; Brinck, T.; Grice, M.; Politzer, P. Correlations Between Molecular Electrostatic Potentials and Some Experimentally-based Indexes of Reactivity. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1992, 88, 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-1280(92)87156-T.Search in Google Scholar

10. Brinck, T.; Murray, J. S.; Politzer, P. Surface Electrostatic Potentials of Halogenated Methanes as Indicators of Directional Intermolecular Interactions. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1992, 44 (S19), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.560440709.Search in Google Scholar

11. Legon, A. C. Prereactive Complexes of Dihalogens XY with Lewis Bases B in the Gas Phase: a Systematic Case for the Halogen Analogue B-XY of the Hydrogen Bond B-HX. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38 (18), 2687–2714. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990917)38:18<2686::AID-ANIE2686>3.0.CO;2-6.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990917)38:18<2686::AID-ANIE2686>3.0.CO;2-6Search in Google Scholar

12. Corradi, E.; Meille, S. V.; Messina, M. T.; Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. Perfluorocarbon-Hydrocarbon self-assembly, Part IX. Halogen Bonding Versus Hydrogen Bonding in Driving self-assembly Processes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39 (10), 1782. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000515)39:10<1782::AID-ANIE1782>3.0.CO;2-5.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000515)39:10<1782::AID-ANIE1782>3.0.CO;2-5Search in Google Scholar

13. Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. Halogen Bonding: a Paradigm in Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 2001, 7 (12), 2511–2519. https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3765(20010618)7:12<2511::AID-CHEM25110>3.0.CO;2-T.10.1002/1521-3765(20010618)7:12<2511::AID-CHEM25110>3.0.CO;2-TSearch in Google Scholar

14. Auffinger, P.; Hays, F. A.; Westhof, E.; Ho, P. S. Halogen Bonds in Biological Molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101 (48), 16789–16794. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0407607101.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Zou, J. W.; Jiang, Y. J.; Guo, M.; Hu, G. X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, H. C.; Yu, Q. S. Ab Initio Study of the Complexes of halogen-containing Molecules RX (X = Cl, Br, and I) and NH3: towards Understanding the Nature of Halogen Bonding and the electron-accepting Propensities of Covalently Bonded Halogen Atoms. Chem. Eur. J. 2005, 11 (2), 740–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200400504.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Metrangolo, P.; Neukirch, H.; Pilati, T.; Resnati, G. Halogen Bonding Based Recognition Processes: a World Parallel to Hydrogen Bonding. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005, 38 (5), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar0400995.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Awwadi, F. F.; Willett, R. D.; Peterson, K. A.; Twamley, B. The Nature of Halogen. Halogen Synthons: Crystallographic and Theoretical Studies. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12 (35), 8952–8960. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200600523.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Murray, J. S.; Lane, P.; Politzer, P. A Predicted New Type of Directional Noncovalent Interaction. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2007, 107 (12), 2286–2292. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.21352.Search in Google Scholar

19. Politzer, P.; Lane, P.; Concha, M. C.; Ma, Y. G.; Murray, J. S. An Overview of Halogen Bonding. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 3 (2), 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-006-0154-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Aakeröy, C. B.; Fasulo, M.; Schultheiss, N.; Desper, J.; Moore, C. Structural Competition Between Hydrogen Bonds and Halogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (45), 13772. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja073201c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Clark, T.; Hennemann, M.; Murray, J. S.; Politzer, P. Halogen Bonding: the sigma-hole. J. Mol. Mod. 2007, 13 (2), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-006-0130-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Wang, W. Z.; Ji, B. M.; Zhang, Y. Chalcogen Bond: a Sister Noncovalent Bond to Halogen Bond. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113 (28), 8132–8135. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp904128b.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Voth, A. R.; Khuu, P.; Oishi, K.; Ho, P. S. Halogen Bonds as Orthogonal Molecular Interactions to Hydrogen Bonds. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1 (1), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1038/NCHEM.112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Bauzá, A.; Mooibroek, T. J.; Frontera, A. Tetrel-Bonding Interaction: Rediscovered Supramolecular Force? Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (47), 12317–12321. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201306501.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Scheiner, S. The Pnicogen Bond: Its Relation to Hydrogen, Halogen, and Other Noncovalent Bonds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (2), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar3001316.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Kolář, M. H.; Hobza, P. Computer Modeling of Halogen Bonds and Other σ-Hole Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (9), 5155–5187. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00560.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Politzer, P.; Murray, J. S.; Concha, M. C. π-hole Bonding Between like Atoms;: a Fallacy of Atomic Charges. J. Mol. Model. 2008, 14 (8), 659–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-008-0280-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Stenlid, J. H.; Brinck, T. Extending the σ-Hole Concept to Metals: an Electrostatic Interpretation of the Effects of Nanostructure in Gold and Platinum Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (32), 11012–11015. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b05987.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Stenlid, J. H.; Johansson, A. J.; Brinck, T. σ-Holes on Transition Metal Nanoclusters and their Influence on the Local Lewis Acidity. Crystals 2017, 7, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7070222.Search in Google Scholar

30. Frontera, A.; Bauza, A. Regium-π Bonds: an Unexplored Link Between Noble Metal Nanoparticles and Aromatic Surfaces. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24 (28), 7228–7234. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201800820.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Halldin Stenlid, J.; Johansson, A. J.; Brinck, T. σ-Holes and σ-lumps Direct the Lewis Basic and Acidic Interactions of Noble Metal Nanoparticles: Introducing Regium Bonds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 2676–2692. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CP06259A.Search in Google Scholar

32. Brinck, T.; Stenlid, J. H. The Molecular Surface Property Approach: a Guide to Chemical Interactions in Chemistry, Medicine, and Material Science. Adv. Theory Simul. 2019, 2 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.201800149.Search in Google Scholar

33. Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Frontera, A. Not Only Hydrogen Bonds: Other Noncovalent Interactions. Crystals 2020, 10 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10030180.Search in Google Scholar

34. Brinck, N. T. Analysis of Intermolecular Interactions Using Calculated Molecular Properties: An Ab Initio Quantum Chemical Study. Ph. D. Dissertation; University of New Orleans: New Orleans, LA, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

35. Brinck, T. The Use of the Electrostatic Potential for Analysis and Prediction of Intermolecular Interactions. In Theoretical and Computational Chemistry; Párkányi, C., Ed.; Elsevier, Vol. 5, 1998; pp. 51–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1380-7323(98)80005-8.Search in Google Scholar

36. Kenny, P. W. Prediction of Hydrogen Bond Basicity from Computed Molecular Electrostatic Properties: Implications for Comparative Molecular Field Analysis. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1994, 2, 199. https://doi.org/10.1039/P29940000199.Search in Google Scholar

37. Gadre, S. R.; Babu, K.; Rendell, A. P. Electrostatics for Exploring Hydration Patterns of Molecules. 3. Uracil. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104 (39), 8976–8982. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp001146n.Search in Google Scholar

38. Kollman, P.; Rothenberg, S. Theoretical Studies of Basicity. Proton Affinities, Li+ Affinities, and -Bond Affinities of Some Simple Bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99 (5), 1333–1342. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00447a008.Search in Google Scholar

39. Novick, S. E.; Janda, K. C.; Klemperer, W. Hfclf: Structure and Bonding. J. Chem. Phys. 1976, 65 (12), 5115–5121. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.433051.Search in Google Scholar

40. Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A. V. Gaussian 16 Suite of Programs; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016. https://gaussian.com/gaussian16/.Search in Google Scholar

41. DiLabio, G. A.; Johnson, E. R.; Otero-de-la-Roza, A. Performance of Conventional and dispersion-corrected density-functional Theory Methods for Hydrogen Bonding Interaction Energies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 12821–12828. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP51559A.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional Visualization of Crystal, Volumetric and Morphology Data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44 (6), 1272–1276. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889811038970.Search in Google Scholar

43. Dennington, R.; Keith, T. A.; Millam, J. M. Gaussview 6; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Recommendations

- Experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data (IUPAC Recommendations 2025)

- IUPAC Technical Reports

- Kinetic parameters for thermal decomposition of commercially available dialkyldiazenes (IUPAC Technical Report)

- FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collections – advice for researchers, authors, and data managers (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Review Articles

- Are the Lennard-Jones potential parameters endowed with transferability? Lessons learnt from noble gases

- Quantum mechanics and human dynamics

- Quantum chemistry and large systems – a personal perspective

- The organic chemist and the quantum through the prism of R. B. Woodward

- Relativistic quantum theory for atomic and molecular response properties

- A chemical perspective of the 100 years of quantum mechanics

- Methylene: a turning point in the history of quantum chemistry and an enduring paradigm

- Quantum chemistry – from the first steps to linear-scaling electronic structure methods

- Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics on quantum computers: challenges and opportunities

- Research Articles

- Alzheimer’s disease – because β-amyloid cannot distinguish neurons from bacteria: an in silico simulation study

- Molecular electrostatic potential as a guide to intermolecular interactions: challenge of nucleophilic interaction sites

- Photophysical properties of functionalized terphenyls and implications to photoredox catalysis

- Combining molecular fragmentation and machine learning for accurate prediction of adiabatic ionization potentials

- Thermodynamic and kinetic insights into B10H14 and B10H14 2−

- Quantum origin of atoms and molecules – role of electron dynamics and energy degeneracy in atomic reactivity and chemical bonding

- Clifford Gaussians as Atomic Orbitals for periodic systems: one and two electrons in a Clifford Torus

- First-principles modeling of structural and RedOx processes in high-voltage Mn-based cathodes for sodium-ion batteries

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Furanyl-Chalcones as antimalarial agent: synthesis, in vitro study, DFT, and docking analysis of PfDHFR inhibition

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- IUPAC Recommendations

- Experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data (IUPAC Recommendations 2025)

- IUPAC Technical Reports

- Kinetic parameters for thermal decomposition of commercially available dialkyldiazenes (IUPAC Technical Report)

- FAIRSpec-ready spectroscopic data collections – advice for researchers, authors, and data managers (IUPAC Technical Report)

- Review Articles

- Are the Lennard-Jones potential parameters endowed with transferability? Lessons learnt from noble gases

- Quantum mechanics and human dynamics

- Quantum chemistry and large systems – a personal perspective

- The organic chemist and the quantum through the prism of R. B. Woodward

- Relativistic quantum theory for atomic and molecular response properties

- A chemical perspective of the 100 years of quantum mechanics

- Methylene: a turning point in the history of quantum chemistry and an enduring paradigm

- Quantum chemistry – from the first steps to linear-scaling electronic structure methods

- Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics on quantum computers: challenges and opportunities

- Research Articles

- Alzheimer’s disease – because β-amyloid cannot distinguish neurons from bacteria: an in silico simulation study

- Molecular electrostatic potential as a guide to intermolecular interactions: challenge of nucleophilic interaction sites

- Photophysical properties of functionalized terphenyls and implications to photoredox catalysis

- Combining molecular fragmentation and machine learning for accurate prediction of adiabatic ionization potentials

- Thermodynamic and kinetic insights into B10H14 and B10H14 2−

- Quantum origin of atoms and molecules – role of electron dynamics and energy degeneracy in atomic reactivity and chemical bonding

- Clifford Gaussians as Atomic Orbitals for periodic systems: one and two electrons in a Clifford Torus

- First-principles modeling of structural and RedOx processes in high-voltage Mn-based cathodes for sodium-ion batteries

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Furanyl-Chalcones as antimalarial agent: synthesis, in vitro study, DFT, and docking analysis of PfDHFR inhibition