Abstract

As seen in many examples of imperial expansions throughout history, the Inkas applied a whole range of policies strategically adapted for the different local organizations, in every corner of their empire, and local groups, in turn, were reconfigured based on the new conditions. Starting from the investigation of a group of late local landscapes of the Hualfín Valley (Department of Belén, Catamarca) in the Northwestern Argentina, from a critical perspective of the sociopolitical definitions classically given to these societies, the aim of this study consists of describing the spatial, social, and temporal dimensions of these landscapes and advancing the discussion about how local groups socially and politically organized themselves, in immediately pre-Inka times and after the incorporation of their territories into the Inka state. To this end, a brief discussion on the Late and Inka periods in Northwestern Argentina and theoretical guidelines for landscape analysis are presented. Then, we address the analysis of one of the landscapes in particular: the Cerro Colorado de La Ciénaga de Abajo and its surroundings, and we briefly analyze the cases of Asampay, Palo Blanco, and Puerta de Corral Quemado, and the regional landscape network.

1 Introduction

The problem of how, throughout history, local communities have adapted or reacted to the new conditions generated by expansive states or empires is a topic of global relevance (Areshian, 2013; D’Altroy & Hastorf, 2001; DeMarrais, 2013; Düring & Stek, 2018; Scott, 2009; Sinopoli, 1994). In Andean archaeology, the explanations about the different modalities of the links between local peoples and the expansion of great states such as Moche, Wari, Tiwanaku, Chimú, and Inka have varied over time, both as a function of the production of new knowledge about different forms of domination, as well as about the advances in research on the populations incorporated into the state structure (Covey, 2008; Moore, 1985; Moore & Mackey, 2008; Tinoco Cano, 2010; Tung, 2014). Undoubtedly, the expansion of the Inka Empire was the one that received the most attention, not only because of the greater number and diversity of societies with which it interacted, but also because of the large amount of information generated around it, both from archaeology and from ethnohistorical sources. The traditional approaches, based mainly on the latter, were more likely to explain the expansion as a homogeneous and progressive advance, the product of a succession of conquests initiated by Pachacuti in 1438 AD (Rowe, 1945), which, upon the arrival of the Spanish in Cusco in 1532 AD, covered the entire Andean area from the south of present-day Colombia to central Chile and Argentina. More recently, from the critical review of the documents and, mainly, from the contributions of archaeology, both the monolithic and linear perspective of the conquest and the chronology of the events began to be questioned (Covey, 2008; DeMarrais, 2013; García, Moralejo, & Ochoa, 2021; Marsh, Kidd, Ogburn, & Durán, 2017; Ogburn, 2012; Santoro, Williams, Valenzuela, Romero, & Standen, 2010; Schiappacasse, 1999; Uribe, 2004; Uribe & Alfaro, 2004; Williams et al., 2009; Williams & D’Altroy, 1998). The classic sociopolitical characterizations of the societies incorporated into the Tawantinsuyu, based mainly on written documents, were also reviewed and reinterpreted from archaeology, and in many cases it was possible to conclude that the political situations described by the chroniclers were explained more by the reconfiguration of local power by the Inkas than by the original organization of local societies (Arkush, 2009; D’Altroy, 1987; Eeckhout, 2000; Frye & Vega, 1988).

Today, it is accepted that there was a great variety of situations in the process of Inka domination, depending on the scale, organization, and location of the incorporated societies, and the purposes of the state in the regions involved. Inka policies were strategically adapted for the different forms of local organization and these, in turn, were reconfigured based on the new conditions (Acuto, 2011; Bray, 1992; Cremonte, Otero, Ochoa, & Scaro, 2019; Earle, 1994; González & Tarragó, 2005; Malpass & Alconini, 2010; Santoro et al., 2010; Uribe, 2004; Williams & D’Altroy, 1998; Williams, Villegas, Gheggi, & Chaparro, 2005; Williams et al., 2009). These multiple contexts undoubtedly enriched the scene on the relations between the state and local groups, but at the same time they show the difficulties that arise for archaeological interpretation.

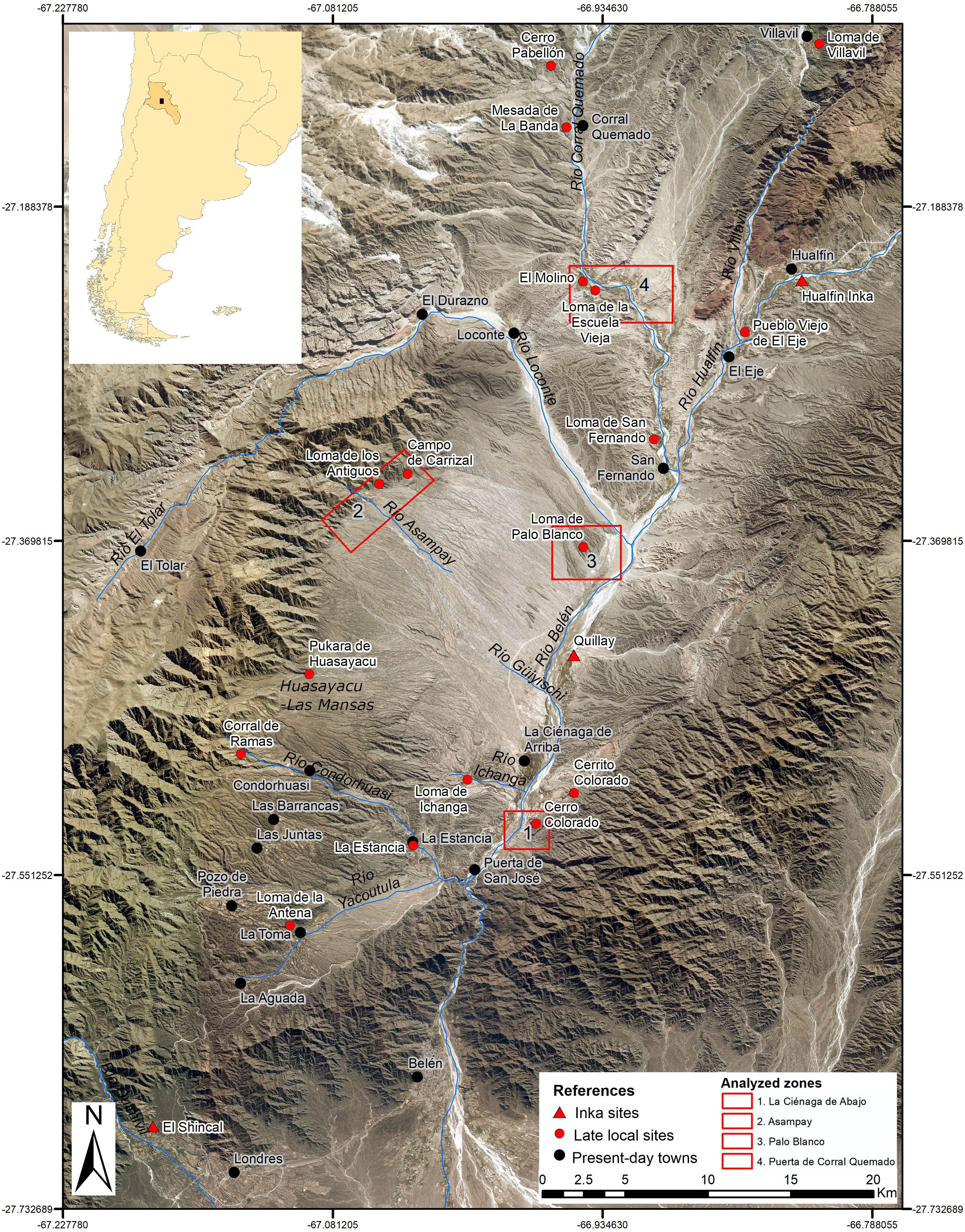

Starting from the investigation of a group of late local landscapes of the Hualfín Valley (Department of Belén, Catamarca) in the Northwestern Argentina (Figure 1), from a critical perspective of the sociopolitical definitions classically given to these societies, the aim of this work consists of describing the spatial, social, and temporal dimensions of these landscapes and advancing the discussion about how local groups organized themselves socially and politically, both in immediately pre-Inka times and after the incorporation of their territories in the Inka state. To this end, a brief discussion on the Late and Inka periods in the Northwestern Argentina and theoretical guidelines for landscape analysis are presented below. Then, we address the analysis of one of the landscapes of the Hualfín Valley in particular: the Cerro Colorado de La Ciénaga de Abajo and its surroundings, and we briefly analyze three other cases – Asampay, Palo Blanco, and Puerta de Corral Quemado – and finally, the regional landscape network.

Hualfín Valley with Late and Inka sites, and the indication of the four analyzed zones.

2 The Late and Inka Periods in the Hualfín Valley

In the archeology of the Northwestern Argentina (NOA), the issue of interactions between local populations and the Inka Empire, as it happened in other areas of the Andes, has been one of the main topics of debate, especially in recent years (Acuto, 2011; Cremonte et al., 2019; González & Tarragó, 2005; Nielsen & Walker, 2009; Tarragó & González, 2005; Williams, 2004; Wynveldt, 2009; Wynveldt, Iucci, & Flores, 2020). The chronology of the expansion from Cusco to the south – that is, to the territory that the Inkas called Kollasuyu – has been profoundly revised in recent years. There is now a consensus that the Inka presence in the NOA can be established in the first half – not in the end – of the fifteenth century (García et al., 2021; Marsh et al., 2017; Williams & D’Altroy, 1998; Wynveldt, Balesta, Iucci, Valencia, & Lorenzo, 2017), so that many of the ideas about local groups in that century, previously considered pre-Inka, had to be revised. In this context, one of the main focuses of discussion is, without a doubt, the sociopolitical characterization of the human groups that inhabited the NOA during the so-called “Late Period” (González & Cowgill, 1975) or “Regional Developments” (Núñez Regueiro, 1974) (1000–1400/1450 AD), that is, the centuries prior to the conquest of this region by the Inkas (1400/1450–1535 AD). Traditionally it was held that these groups would have gone through a process of social complexity that led to the formation of large “señoríos” or chiefdoms with well-defined territories (Núñez Regueiro, 1974; Raffino, 1988; Sempé, 1999). However, new research focused locally on settlement patterns, architecture, and detailed studies of material culture has challenged many of the characteristics typically associated with this period, as well as the classical forms of sociopolitical organization (Acuto, 2007; Alvarez Larrain & Greco, 2018; Balesta, Zagorodny, & Wynveldt, 2011; Coll Moritan & Nastri, 2015; Leibowicz, 2007; Nastri, 2004; Nielsen, 2006a,b; Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018).

The Hualfín Valley, located in the center-west of the province of Catamarca, is an emblematic region for Argentine archaeology, since the first chronological sequence of the NOA was constructed there (González, 1955; González & Cowgill, 1975). The concept of “Late Period” was also defined in this valley, based on the materials associated with the “Belén culture,” mainly characterized by its pottery (Figure 2a–d). According to the model proposed by Sempé (1981, 1999), late local groups would have undergone a process of change from simple villages to increasingly complex settlements, integrating into a chiefdom or “señorío” with expansionist objectives into neighboring regions.

Late materials found in sites and tombs of Hualfín Valley: (a) Belén jar (LI); (b) Belén little pot (CC); (c) Belén puco or bowl, PCQ tomb (MLP-Ar 6413 CMB), (d) Belén pot, PB tomb (MLP-Ar 6507 CMB); (e) Ordinary puco, CC tomb; (f) footed pots, PCQ tomb (MLP-Ar 6469 CMB); (g) Ordinary pot, CC tomb; (h) Sanagasta pot (LI); (i) Santa María pot, Room 98 of El Molino (PCQ); (j) Santa María puco, PCQ tomb (MLP-Ar 6409 CMB); (k) Santa María Tricolor urn, El Eje tomb (MLP-Ar 6443 CMB); (l) Famabalasto Negro Grabado puco, PCQ tomb (MLP-Ar 6355 CMB); (m) Famabalasto Negro sobre Rojo pot (MLP-Ar 6426 CMB); (n) Yocavil Tricolor puco, PB tomb (MLP-Ar 6502 CMB); (o) Belén-Inka jar, SF tomb (MLP-Ar 6486 CMB); (p) Inka pot, SF tomb (MLP-Ar 6479 CMB); (q) aribaloide, SF tomb (MLP-Ar 6485 CMB); (r) Ona obsidian nodule (Barranca CC); (s) Ona obsidian projectile point (Asampay); (t) incise lithic ball; (u) bronze knife (CC); (v) fragment of an armadillo-shaped vessel Belén (CC); and (w) ceramic figurine (CC).

Regarding the Inka conquest of the Hualfín Valley, González (1980) pointed out that the absence of large local conglomerates in the region led the Inka to establish their installations in places without previous occupation, and that these facilities were directly related to roads and mining. According to Sempé (1999), the location of the site called “Hualfín Inka” in the north of the valley, and the main center of El Shincal de Quimivil in the south, demarcating the limits of the political core of the Belén chiefdom, was an Inka strategy to incorporate the pre-existing sociopolitical structure into the state. However, this chiefdom would have resisted the conquest, so that, after a period of struggle, the Inka would have dominated the local groups, who were sent as forced laborers or mitimaes to different regions and replaced by groups from other regions (Sempé, 1999). Raffino proposed a model that emphasizes the centralist and militarized character of the Inka state, as well as the monopolist management of natural, productive, and human resources (Raffino, 1981). Particularly for the Hualfín Valley, research at El Shincal de Quimivil revealed one of the most important administrative centers within the present-day Argentine territory (Raffino, Iácona, Moralejo, Gobbo, & Couso, 2015). New studies on the Inka occupation of the region made very relevant advances regarding the knowledge of the Inka infrastructure in the region and some economic, political, and ideological aspects of their relations with local communities, although they are focused on Inka installations (Giovannetti, 2021; Lynch & Giovannetti, 2018; Moralejo & Gobbo, 2015).

The aim of the archaeological research carried out by our team in the last two decades on the late local sites of the Hualfín Valley (Dept. of Belén, Catamarca) (Figure 1) is reconstructing the past of local groups from a landscape perspective, understood as a network of spatial, social, and temporal relationships between multiple agents. Based on these works, the classical positions on the chronology, social, political, and economic organization of these local groups were reviewed, as well as the way in which they were incorporated into the Inka Empire structure. The aim of this study is based on the results of these reviews, and points to analyze the late local landscapes, with emphasis on the social and political practices put into play by the groups that inhabited them, without resorting to the classic schemes of sociopolitical categories.

3 Relational Landscape, Local Landscape, and Political Landscape

Since 1980, landscape archeology has generated a wide production on various topics related to the ways of inhabiting the world by human societies (Anschuetz, Wilshusen, & Scheick, 2001; Aston, 1985; David & Thomas, 2008; Roberts, 1996; Ucko & Layton, 1999). The regional and comprehensive nature of the landscape approaches allowed, in many cases, to address phenomena of great relevance to the history of human groups, including changes in the sociopolitical organization and interactions between non-state and state (and imperial) societies (Cruz, Joffre, & Vacher, 2023; Düring & Stek, 2018; Maeir, Dar, & Safrai, 2003; Moore, 2005; Wiesheu, 2011).

Based on the critiques made by different authors to absolutist and subjectivist conceptions (Cosgrove, 1984; Criado Boado, 1991; Ingold, 2000; McFadyen, 2008; Norton, 1989; Smith, 2003; Zedeño, 2000), an idea of relational landscape have been developed, that is, the landscape defined not as an environment or a container space of regional scale, nor only as a social construction, but as a network of relationships resulting from practices distributed in time and space (McFadyen, 2008). One of the main advantages of this concept is the possibility it offers to work on the construction of a progressive framework made up of a variety of elements generated from empirical observation, without resorting to previous chronological, spatial, cultural, or sociopolitical schemes, which constrain the information into certain abstract categories. In addition, the concept of landscape incorporates the idea of the experience of being in the world and the inhabited landscape (Ingold, 2000), whereby, beyond the analysis of broad scales, the human and subjective scale must be considered (Acuto, 2013). In this sense, the physical space of experience, perceived by the senses and represented by the imagination, must be addressed (Smith, 2003). Moreover, landscapes are a historical production, an enduring record of the generations that have inhabited them (Ingold, 2000; Zedeño, 2000).

Based on these theoretical notions, we will approach the analysis of the materiality associated with the Late and Inka periods in Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo and the spaces at the foot, understood as a local landscape, that is, a network of spatial, social, and temporal relationships between diverse places and agents, which includes one village – or more, close to each other – and its surroundings (Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018). The spatial dimension is constituted by the spatial experience, which includes built and unbuilt reference points or spaces and the whole set of practices distributed among those spaces, including their construction and the flow of people, animals and things; the spatial perception, which refers to the sensorial interaction between actors and physical spaces, for example, the field view from a particular point or site; and finally, the spatial imagination, which deals with the discourses of space and its representations by their inhabitants, including those that can be generated by iconography or by certain objects, characters, animals, plants, architecture, and places that in themselves can evoke other landscapes, places, experiences or even memories, and future projections.

Social dimension aims to interpret social practices distributed in space and time based on the analysis of the archaeological contexts recovered in the different spaces and the associated material culture, as well as all the information on the relationships between different agents that participate in – and transform – the landscapes.

Finally, temporal dimension addresses the historical production of the landscape, as a record of practices distributed in it, considering time not only as a chronological variable to analyze sequences or contemporary events, but also as a concept linked to the ways that people organize it (practice time) and to the construction of memories and ancestry. In archaeological materiality, this can be associated with certain places, constructive forms and objects that evoke past times, giving temporal depth to the landscape.

The reconstruction of these landscapes consists of gradually integrating the three dimensions in a relational, progressive, and interpretative proposal. And this integration must necessarily consider politics, as landscapes are not only expressions of power, they are themselves political order and power relations are materialized, experienced, and represented in them (Smith, 2003). In line with this proposition, we can consider trying to understand how political relations operate through landscapes.

Leaving aside typologies for sociopolitical ascription, the challenge for a political definition of landscapes in archaeology is to establish how materiality represents the political order of human groups. Following different theoretical contributions for the NOA in the same period (Acuto, 2007; Nielsen, 2006a,b), we think that the key is not a list of indicators of a certain type of sociopolitical organization, but the possibility of establishing the degree of centralization at the political, economic, demographic, manufacturing, and symbolic levels, for a defined set of sites and materials, and at the same time, the theoretical counterpoint between individualizing social practices, that point to the definition of hierarchical and unequal societies, as opposed to collectivist practices, typical of more horizontal organizations. In turn, the evidence of centralization/decentralization in our case, must be evaluated in conjunction with the changes generated in local society from its incorporation into an expansive state like the Inka. In this sense, the associations that can be established between local sites and all the elements that represent imperial expansion, presence, or influence are essential. In addition, as a base for interpretation, the multiple contexts in which groups of local societies are related to the Tawantinsuyu must be taken into account, particularly toward the south of Cusco, which would imply not only different imperial strategies but also various decisions and reconfigurations of the local power groups themselves (Acuto, 2011, 2012; Leibowicz, 2012; Nielsen, 2006a; Santoro et al., 2010; Urbina, Uribe, Agüero, & Zori, 2019; Uribe, 2004; Williams & D’Altroy, 1998).

4 The Late Sites of the Hualfín Valley

Before beginning the analysis of the local landscapes, it is necessary to present in general terms the set of late archaeological sites. Although in the last century, numerous expeditions and archaeological research reported practically all the localities in which archaeological remains were found in the Hualfín Valley (González, 1955; González & Cowgill, 1975; Sempé, 1999; Weiser & Wolters, unpublished data), the location of the sites and the analysis of their spatial relationships were not the subject of systematic studies. In this sense, an important advance in recent years was the exact location of most of the known late sites, the identification of many new ones, and the analysis of their distribution at a regional level (Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018). The identification of these sites was first carried out from the observation of the architecture and the detection of the typically late ceramics on the surface (Figure 2), adding excavation information and radiocarbon dating. In previous works, we have analyzed in depth the radiocarbon ages available for the Hualfín Valley (Table 1) (Wynveldt et al., 2017). Many of the sites present occupations with greater probabilities for the period between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries AD. Almost half of the dates obtained are restricted to the first decades of the fifteenth century AD. The characteristics of these contexts allow us to argue that they would correspond to events very close to the abandonment of these structures and, taking into account their chronology, these abandonments would be related to the Inka intervention. Other cases present later ranges (fifteenth–sixteenth centuries AD), which would confirm the continuity of the occupation during the Inka times.

Radiocarbon dating of Late Hualfín Valley sites

| Locality | Site | Sample year | Measurement year | Lab code | Type of sample | C-14 Age BP | Calibration AD (Curve SHcal13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1σ (68.2% prob.) | 2σ (95.4% prob.) | |||||||

| Asampay | Campo de Carrizal, R1, B1 | 1999 | 2000 | LP-1250 | Charcoal | 310 ± 60 | 1502–1593 (40.9%); 1613–1667 (25.9%); 1789–1791 (0.7%) | 1459–1681 (81.4%); 1730–1802 (14%) |

| Asampay | Loma de los Antiguos, R31 | 1952 | 2005 | LP-1644 | Human bone | 320 ± 50 | 1506–1587 (45.7%); 1618–1654 (22.5%) | 1463–1672 (90.8%); 1744–1759 (2%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Lajas Rojas 2 | 2006/7 | 2007 | LP-1793 | Charcoal | 320 ± 60 | 1502–1594 (42.6%); 1613–1661 (25.6%) | 1459–1675 (85.6%); 1737–1798 (9.8%) |

| Asampay | Loma de los Antiguos, R9 | 1995 | 1997 | LP-937 | Charcoal | 330 ± 50 | 1505–1588 (48.8%); 1617–1649 (19.4%) | 1460–1670 (94.1%); 1749–1752 (0.2%) |

| Asampay | Loma de los Antiguos, R3 | 1998 | 1999 | LP-1039 | Charcoal | 350 ± 50 | 1502–1593 (54.2%); 1613–1638 (14%) | 1460–1654 (95.4%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Loma de Ichanga, R9 | 2011 | 2012 | LP-2667 | Camelidae | 360 ± 50 | 1500–1597 (56.3%); 1611–1632 (11.9%) | 1460–1648 (95.4%) |

| La Ciénaga de Arriba | Cerrito Colorado, R8 | 1952 | 1958/60 | L-476C | Carbón vegetal | 400 ± 100 | 1454–1529 (30%); 1531–1627 (38.2%) | 1395–1688 (89.3%); 1728–1804 (6.1%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Loma de Ichanga, R6 | 2007 | 2007 | LP-1832 | Corn cob | 420 ± 50 | 1449–1510 (42.6%); 1578–1621 (25.6%) | 1443–1629 (95.4%) |

| La Ciénaga de Arriba | Cerrito Colorado, R8 | 1952 | 2010 | LP-2309 | Charcoal | 420 ± 70 | 1448–1512 (35.4%); 1548–1563 (5.5%); 1570–1623 (27.3%) | 1427–1645 (95.4%) |

| La Ciénaga de Arriba | Cerrito Colorado, R3 | 1952 | 2007 | LP-1810 | Charcoal | 420 ± 70 | 1448–1512 (35.4%); 1548–1563 (5.5%); 1570–1623 (27.3%) | 1427–1645 (95.4%) |

| Asampay | Carrizal, E3 NH2, R1, B2 | 2004 | 2010 | LP-2330 | Charcoal | 430 ± 60 | 1443–1510 (43.3%); 1554–1556 (0.7%) 1576–1622 (24.2%) | 1430–1633 (95.4%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Cerro Colorado, R2 | 2010 | 2015 | AA105209 | Charcoal | 446 ± 25 | 1447–1486 (68.2%) | 1440–1504 (84.9%); 1591–1615 (10.5%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Lajas Rojas 4 | 2008 | 2010 | LP-2651 | Corn cob | 460 ± 50 | 1432–1500 (60%); 1597–1611 (8.2%) | 1412–1515 (70.6%); 1540–1625 (24.8%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Cerro Colorado, R35 | 2011 | 2012 | AA100176 | Corn cob | 478 ± 38 | 1429–1465 (60%); 1467–1477 (8.2%) | 1411–1502 (89.7%); 1593–1614 (5.7%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Cerro Colorado, R2 | 2010 | 2011 | AA94600 | Corn cob | 493 ± 34 | 1428–1456 (68.2%) | 1408–1488 (95.4%) |

| La Estancia | La Estancia, R1 | 2015 | 2017 | AA109360 | Charcoal | 511 ± 19 | 1430–1447 (68.2%) | 1419–1453 (95.4%) |

| La Estancia | La Estancia, R13 | 2014 | 2015 | AA105210 | Corn cob | 512 ± 35 | 1422–1451 (68.2%) | 1400–1464 (95.4%) |

| El Eje | Pueblo Viejo de El Eje, R72 | 1969 | 1969/70 | Lu-371 | Charcoal | 520 ± 50 | 1410–1452 (68.2%) | 1326–1340 (1.5%); 1390–1499 (92.7%) |

| Palo Blanco | Loma de Palo Blanco, Pukara R34 | 2011 | 2015 | AA105211 | “Jarilla” | 523 ± 26 | 1421–1445 (68.2%) | 1410–1452 (95.4%) |

| Palo Blanco | Loma de Palo Blanco, Mesada Baja R20 | 2016 | 2018 | AA111411 | Corn cob | 523 ± 31 | 1420–1446 (68.2%) | 1405–1455 (95.4%) |

| Puerta de Corral Quemado | Loma de la Escuela Vieja, R6 | 2010 | 2011 | AA88362 | Corn cob | 521 ± 36 | 1419–1447 (68.2%) | 1401–1458 (95.4%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Cerro Colorado, R36 | 2010 | 2011 | AA85880 | Human bone | 539 ± 43 | 1409–1443 (68.2%) | 1327–1340 (1.9%); 1390–1460 (93.5%) |

| Puerta de Corral Quemado | El Molino, R34 | 2017 | 2018 | AA111410 | Camelid | 519 ± 27 | 1423–1446 (68.2%) | 1410–1453 (93.5%) |

| Puerta de Corral Quemado | El Molino, R34 | 2017 | 2018 | AA111409 | Human bone | 558 ± 26 | 1407–1430 (68.2%) | 1398–1442 (95.4%) |

| Puerta de Corral Quemado | El Molino, R110 | 2010 | 2011 | AA88363 | Human bone | 585 ± 44 | 1328–1336 (6.8%); 1391–1433 (61.4%) | 1315–1357 (23.5%); 1381–1448 (71.9%) |

| El Eje | Pueblo Viejo de El Eje, R53 | 2010 | 2011 | AA94601 | Lama sp. | 602 ± 42 | 1323–1345 (22.8%); 1388–1421 (45.4%) | 1308–1361 (36.3%); 1378–1441 (59.1%) |

| La Ciénaga de Abajo | Cerro Colorado, R48 | 1981 | 1981/82 | AC-364 | Charcoal | 760 ± 90 | 1223–1320 (50.5%); 1350–1386 (17.7%) | 1151–1416 (95.4%) |

Note: Dates prior to 1990 compatible with the new dates are included in bold.

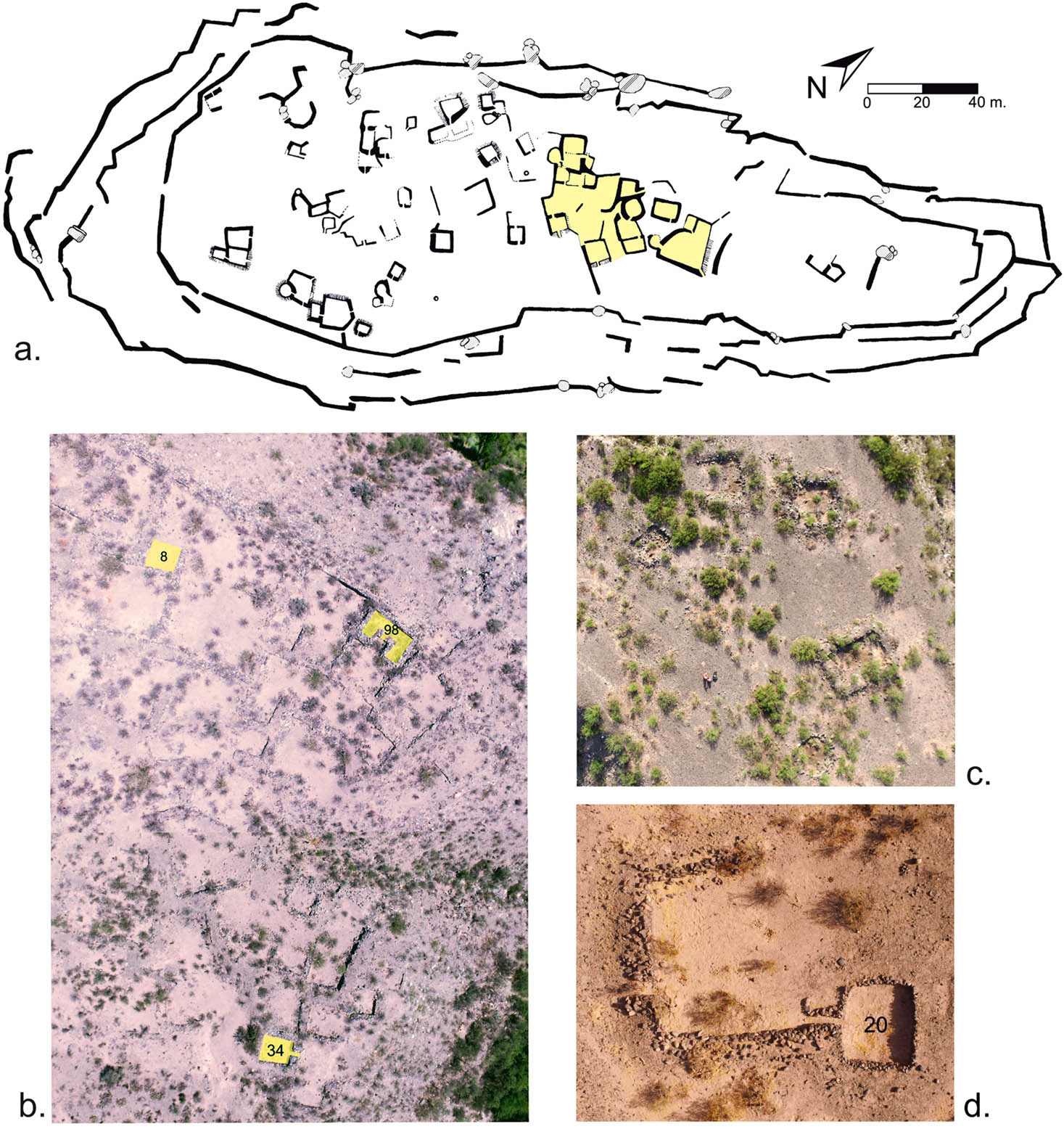

Regarding the characteristics of the sites identified as villages (Table 2), there are differences in terms of their size, although all can be defined as relatively small, located on hills and some of them with defensive architecture (Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018). Based on their spatial pattern, settlements can be classified into two general types: an isolated pattern, which implies that the architectural structures are not directly linked to each other (Figure 3c), with the exception of the communication between a room and a larger external structure or space, like a patio (Figure 3d); and an agglutinated pattern (Figure 3a and b), which supposes a greater concentration of the sets of rooms, with different forms of communication – corridors, openings, shared walls, internal sub-divisions, etc.

Main characteristics of late local sites in the Hualfín Valley

| Site | Locality | Site type | Elevation (m) | Intrasite area (ha) | Spatial pattern | Rooms | Sectors or levels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Estancia | La Estancia | On flat hill | 20 | 1 | Isolated | 13 | No |

| Cerro Colorado | La Ciénaga de Abajo | Defensive on hill | 150 | 21 | Agglutinated | 114 | Yes |

| Cerrito Colorado | La Ciénaga de Arriba | Defensive on hill | 150 | 7 | Isolated | 20 | Yes |

| Loma de Ichanga | La Ciénaga Río Ichanga | On flat hill | 50 | 8.2 | Isolated | 15 | No |

| Pukara de Huasayacu | Huasayacu | Defensive on hill | 50 | 0.7 | Agglutinated | 20 | No |

| Loma de los Antiguos | Asampay | Defensive on hill | 200 | 2.2 | Agglutinated | 45 | Yes |

| Campo de Carrizal | Asampay | On piedmont | 30 | ca. 30 | Isolated | 12 | Yes |

| Loma de Palo Blanco | Palo Blanco | On flat hill and defensive on hill | 60 | 10.3 | Isolated | 80 | Yes |

| Loma de San Fernando | San Fernando | On hill | 50 | 0.55 | Isolated | 20 | Yes |

| Pueblo Viejo de El Eje | Eje de Hualfín | Defensive on hill | 40 | 1.6 | Agglutinated | 70 | Yes |

| Loma de la Escuela Vieja | Puerta de Corral Quemado | On flat hill | 50 | 4.6 | Isolated | 59 | Yes |

| El Molino | Puerta de Corral Quemado | Defensive on hill | 70 | 3.2 | Agglutinated | 116 | Yes |

| Mesada de la Banda | Corral Quemado | On flat hill | 25 | 5.5 | Isolated | 38 | No |

| Cerro Pabellón | Corral Quemado Norte | Defensive on hill | 95 | No data | Agglutinated | 20 | No |

| Loma de Villavil | Villavil | On flat hill | 50 | No data | Isolated | No data | No |

Spatial organization of late settlements: (a) Loma de los Antiguos (Asampay); the highlight shows the agglutinated pattern of the central sector; (b) aerial photography of El Molino (Puerta de Corral Quemado), with agglutinated pattern; highlighted: Rooms 8 and 34 (recently excavated), and 98 (excavated by González in 1969); (c) aerial photography of Loma de la Escuela Vieja (Puerta de Corral Quemado), an example of isolated pattern; (d) aerial photography of Room 20 and their yard, Mesada Baja of Palo Blanco.

5 Landscape of the Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo

La Ciénaga is a rural town located in the southeastern sector of the Hualfín Valley (Figure 1). This entire area shows innumerable evidence of occupation from the early agro-pottery groups to the present day. Research focused on the Late Period (1000–1450 AD) has identified three zones where the most important archaeological record is concentrated: La Ciénaga de Arriba, with the pukara of Cerrito Colorado; Ichanga River, with a small settlement called Loma de Ichanga; and Cerro Colorado, on the eastern bank of the Belén River, opposite to the current village known as La Ciénaga de Abajo. The studies carried out in these three areas made it possible to establish close links between their late occupations: on the one hand, chronology of the three sites indicates that they were occupied simultaneously at least in the fifteenth century; furthermore, there is intervisibility between them, and both their architectural characteristics and material culture recovered coincide in many aspects. However, they also show important differences. Loma de Ichanga and Cerrito Colorado are made up of a few scattered dwellings, while Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo is a pukara with more than 100 structures on its summit. In this study, we will focus on the latter site.

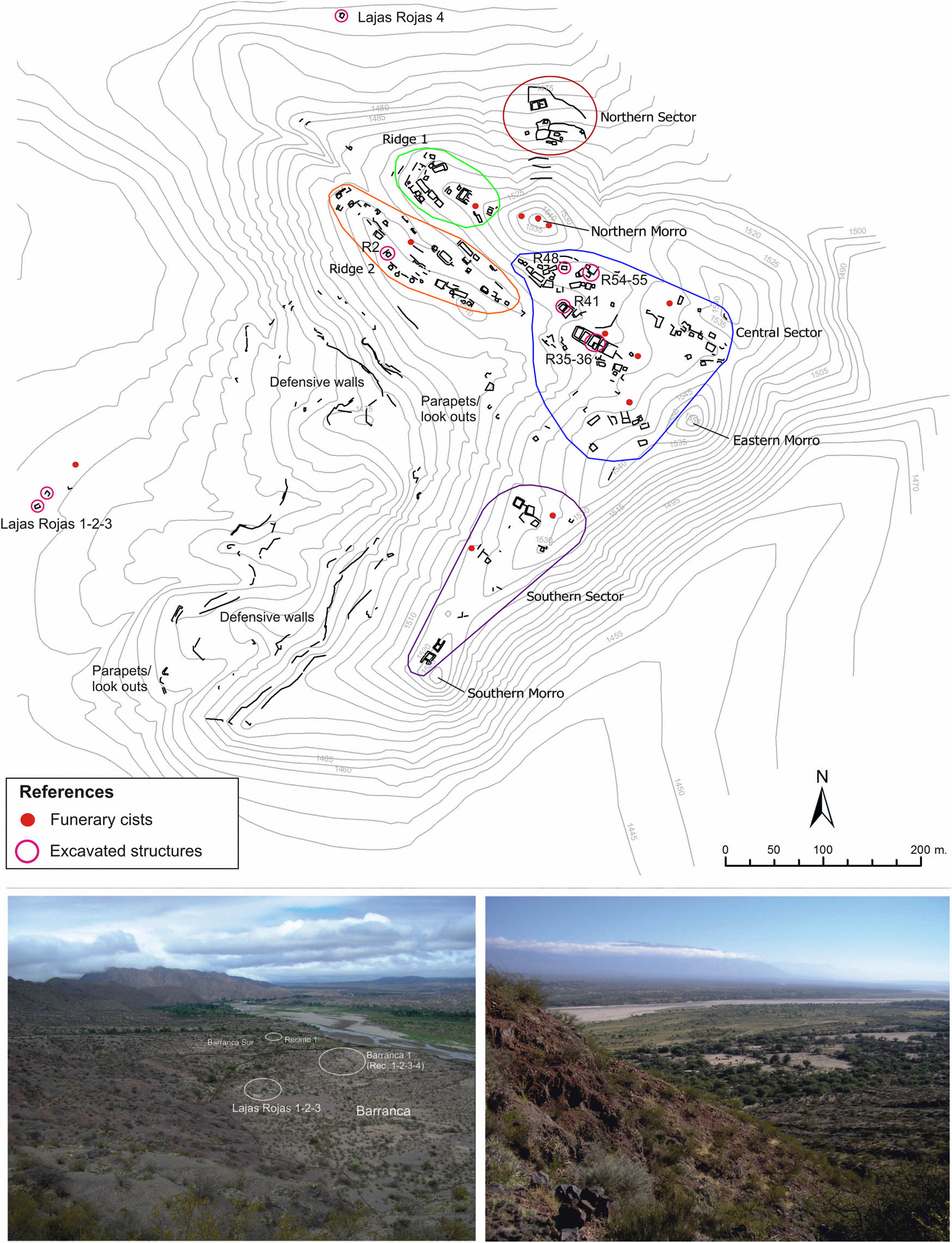

Considering the terms presented above, we can define Cerro Colorado and its surroundings as a local landscape. This site is an irregularly shaped hill over 100 m high, rising on a high terrace on the eastern bank of the Belén River (Figure 4). It was reported by Bruch (1913) in an exploration in 1908, and rediscovered by Sempé in 1980, who excavated a structure on the summit (Sempé, 1981). In 2005, we restarted research in the area, and since then we have carried out prospections, surveys, and excavations, both on the summit of the site and in the surrounding area. Based on the information obtained, spatial and architectural studies were carried out, in addition to the analysis of the excavated archaeological contexts and the different types of recovered materials (Balesta & Zagorodny, 2010; Flores, 2013; Iucci, 2016; Lorenzo, 2017).

Top: Plan of Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo. Bottom left: View from Ridge 1 to the southwest, with the Barranca at the foot and the Barranca Sur to the south, with the indication of the excavated sites. Bottom right: View from the Central sector to the north.

5.1 Spatial Dimension

The analysis of the spatial dimension of Cerro Colorado included the study of its spatial configuration and the constructive characteristics of its structures, as well as the accessibility and visibility to and from the site. With respect to the spatial configuration, the structures on the summit are distributed in five distinct sectors: Ridge 1 (14 rooms), Ridge 2 (20 rooms), North sector (5 rooms), Central sector (61 rooms), and South sector (14 rooms). At the southern edge of the site, and along the entire western flank of the hill, there are several walls and structures as parapets and look-outs; these structures, together with the almost inaccessible slopes on the eastern and southern sides, allow us to define the site as a defensive settlement. Other types of structures are funerary circular cists, 14 of them were identified on the summit – some in sectors free of domestic structures and others next to, or within, the residential complexes.

Of a total of 114 rooms, 57 are isolated, while the rest are configured in 20 groups, divided into 41 sub-groups.[1] Most of the rooms are square in shape, followed in order of importance by rectangular and trapezoidal ones; in addition, only one circular room is observed on the summit, a shape typically associated with a grinding function. In terms of construction materials, there are different raw materials and construction technologies at Cerro Colorado, like the use of sedimentary slabs, obtained and edged in situ, and boulders of different types, many of them granitic. The construction of the walls shows a predominance of the “double filled pirca” technique – two lines of stones with a filling of sand and rubble – although there are also rooms that combine double pirca with embankment pirca – a single line of stones placed on an embankment dug into the ground, taking advantage of the terrain unevenness. A particular characteristic of Cerro Colorado is the high proportion of rooms larger than 36 m2 (30%), in relation to other sites, such as Loma de Ichanga and Cerrito Colorado, which have only one and two rooms larger than that surface, respectively. This is interesting considering that the rooms that have been interpreted as single-family dwellings are generally smaller.

Another remarkable fact is that the highest proportion of large rooms is found in the Central (32%) and South (35%) sectors, and decreases in Ridge 1 (26%) and Ridge 2 (10.5%). Cerro Colorado also presents particularities in terms of communication between its spaces: approximately half of the rooms communicate directly with the exterior, while the other half have communication with other rooms, courtyards, or terraced spaces. In Loma de Ichanga, only two rooms are intercommunicated, and in Cerrito Colorado, the rooms communicate directly with the exterior or with terraced spaces.

The analysis of the orientation of the accesses to the rooms also shows some remarkable data (Table 3). The averages obtained for the whole set of late sites in the valley show a clear predominance of orientations toward the northeast, east, southeast, and north, in that order; these results were related to dispositions that avoid the action of south wind, an agent which is strong and permanent, while taking advantage of the light and heat of another important agent: the Sun. However, Cerro Colorado shows significant variation with respect to these averages, especially evident in the direction of many accesses toward the northwest, southwest, and west. This can be explained considering the location of the site on the eastern side of the river and in the southeastern sector of the valley; in addition, the western slope is the most accessible flank, therefore, the fact of having more accesses oriented toward the northwest, west, and southwest, allowed to obtain a wide field view toward the spaces of more circulation and less naturally protected. In this sense, the disposition of some rooms with their entrances facing the valley, in sectors from which an excellent field view is obtained, suggests that they were not only houses or shelters, but also look-outs.

Averages in the orientation of accesses to the rooms in the Late settlements of the Hualfín Valley

| Late sites | N | NE | E | SE | S | SW | W | NW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesada de La Banda (CQ) | 12.5 | 3.125 | 56.25 | 12.5 | 6.25 | 0 | 6.25 | 3.125 |

| El Molino (PCQ) | 23.404 | 21.277 | 31.915 | 6.383 | 8.5106 | 2.1277 | 4.2553 | 2.1277 |

| Loma de la Escuela Vieja (PCQ) | 7.7 | 28.2 | 43.6 | 5.13 | 2.56 | 7.7 | 0 | 5.13 |

| LPB y Loma Este (PB) | 12.25 | 12.25 | 22.9 | 27 | 8.3 | 6.25 | 0 | 10.41 |

| Loma de los Antiguos (AS) | 7.14 | 17.9 | 21.4 | 39.3 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 7.14 | 0 |

| Campo de Carrizal (AS) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cerrito Colorado | 12.5 | 12.5 | 18.75 | 31.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 0 | 12.5 |

| Loma de Ichanga | 33.3 | 0 | 22.2 | 22.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22.2 |

| Pukara Huasayacu | 17.647 | 58.824 | 5.8824 | 11.765 | 0 | 5.8824 | 0 | 0 |

| La Estancia | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Averages (without Cerro Colorado) | 16.644 | 27.408 | 24.29 | 17.553 | 3.5471 | 3.181 | 1.7645 | 5.5493 |

| Cerro Colorado | 5.2 | 26.8 | 10.3 | 17.5 | 1 | 9.3 | 7.2 | 22.7 |

Note: The orientation was obtained by calculating a range of ±22.5° with respect to each cardinal point.

Among the different sectors of the site, the prominent is the Central sector, which is distinguished not only for being the one with the highest number of structures, but also for the fact that it presents several groups with an agglutinated pattern, as Complex VIII (Figure 5). This group of constructions measures 50 m long by 11 m wide and is divided into five large rectangular aligned structures, some with internal subdivisions and walls of greater height than the common late sites. Both the configuration and the dimensions of this entire complex lead to consider it exceptional among the valley sites. Ridges 1 and 2 show structures of various shapes and sizes, although they have a less number and are generally smaller and isolated. From these two ridges, there is a full view of the valley. The Northern sector is almost isolated from the rest of the site; it is characterized by large walls and a few dwelling structures. The Southern sector corresponds to the ridge of the hilltop, where a few isolated groups of rooms are clustered.

Top: Plan of the Central sector with Complex VIII indicated, on a satellite image. Bottom: Complex VIII photographed by a drone, with Rooms 35 and 36 highlighted.

Accessibility was analyzed based on the study of different cost paths for access to the site and circulation between the different sectors, calculated with GIS. The analysis of visibility included the fields of view (viewsheds in GIS) obtained from each sector of the site toward the immediate surroundings, the intervisibility between the different sectors and with other sites in the valley, and the visualization from the base toward the site (Wynveldt, Sallés, & López, 2018). In this way, it could be determined that the Central sector was the most protected, both due to its accessibility and the low visualization from the base of the Cerro.

5.2 Social Dimension

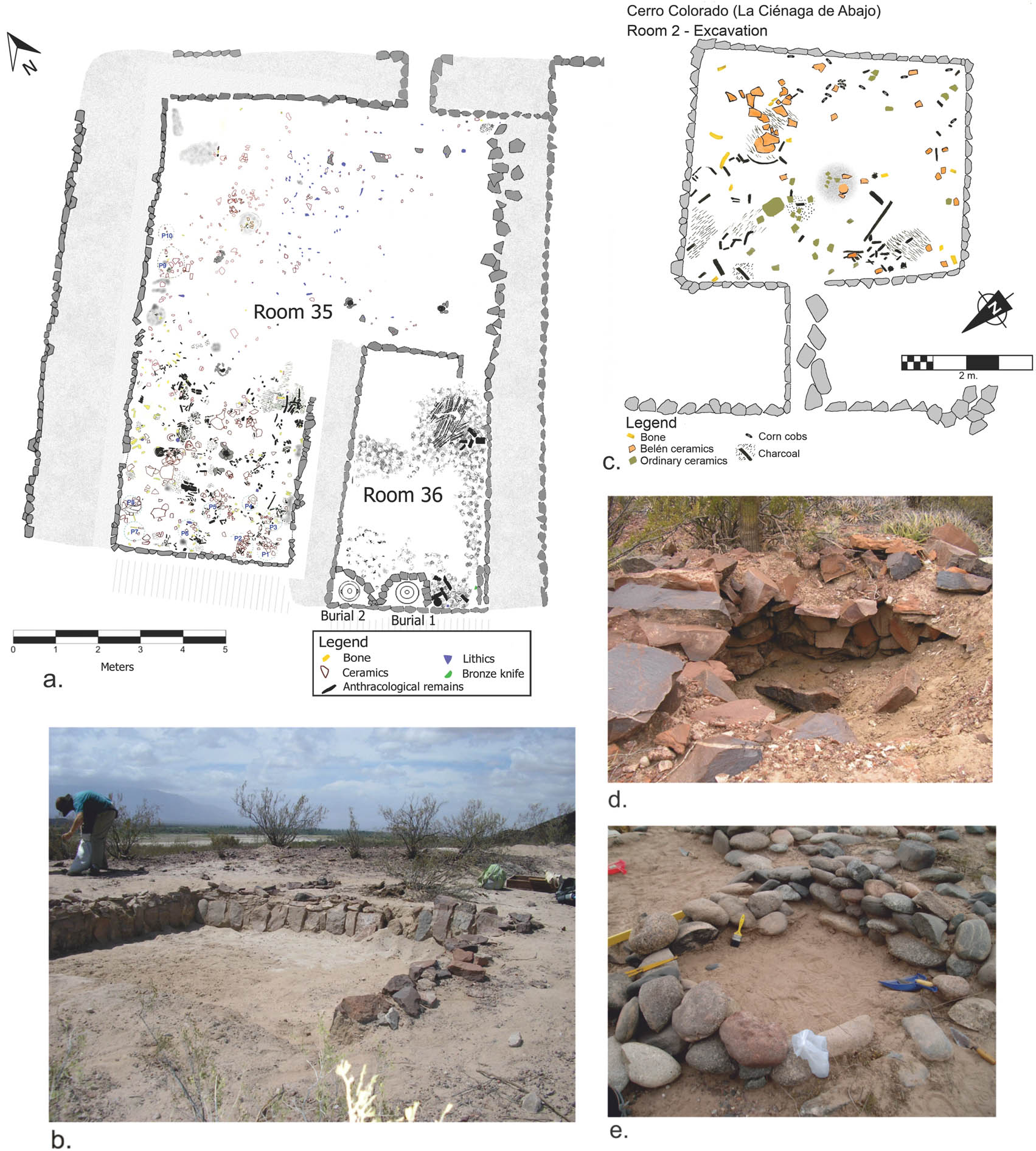

Regarding the analysis of the social dimension of the landscape (Table S1), the archaeological contexts excavated in Rooms 35 and 36 (Figure 6a) of Complex VIII on the Central sector show evidence that could be linked to a supra-familial use of these structures. On the one hand, in Room 35, ten different varieties of corn were found associated with the remains of large ordinary vessels and a small jar, which would indicate the production of chicha (maize beer) in that space (Balesta, Valencia, & Wynveldt, 2014). In addition, there are remains of camelid meat processing (Lorenzo, 2017). Two stone structures with infant burials in urns, a bronze knife, and an incised lithic ball (Figure 2t and u) were found in Room 36. These objects are not commonly found in domestic contexts at other late sites, and would therefore be linked to the infant burial ritual. In both rooms there is an absolute predominance of Belén and late ordinary ceramics, typical of local late sites, and lithic artifacts made of obsidian from the Ona and Cueros de Purulla sources, located more than 200 km away, in the puna (Flores, 2013). In Room 2 (Figure 6c), located in Ridge 2, the remains of Belén and ordinary vessels, unformed lithic objects made of Ona obsidian, carbonized corncobs, and abundant archaeofaunal remains with evidence of having been consumed were recovered (Lorenzo, 2017).

Different architectural structures of Cerro Colorado and sites at the foot: (a) excavation plan of Rooms 35 and 36; (b) Lajas Rojas 2; (c) Plan of the excavation of Room 2; (d) Looted funerary cist at the top of the site; and (e) Barranca 1, Room 1.

Thirty-three structures were recorded in the Barranca site at the foot of Cerro Colorado, some isolated and others forming groups of 2, 3, and 4 small constructions. Concentrations of lithic and ceramic material of different types were also observed; in addition, a complete Ona obsidian nodule was found (Figure 2r). Most of the constructions were made of boulders (Figure 6e). Excavations at one of these assemblages, called Barranca 1, revealed that they were very shallow constructions, perhaps the foundations of small adobe or quincha structures. Another series of constructions located at the base of the pukara are Lajas Rojas, rectangular rooms built with reddish sedimentary rocks (Figure 6b). Three of these rooms, added to a looted burial cist, are located just at the foot of the western slope, and one of them at the northern base of Cerro Colorado. Another room located at the foot is circular in shape and has an access corridor. Although it is not possible to define a particular function for each of these constructions, the diversity of shapes and dimensions shows that different practices were undoubtedly carried out in them: some had a funerary function, others, such as the Lajas Rojas and the circular room with corridor, may be linked to productive practices, associated with works done at the foot of the pukara and in the surrounding fields, while the smaller and superficial ones may have corresponded to deposit or storage structures. Although no radiocarbon dates are available for these structures, it can be assumed that the presence of stores at the foot of the site would imply a stable situation, perhaps linked to the Late Inka period, and not to the troubled late times.

Crossing a small riverbed to the south of the Cerro Colorado is Barranca Sur, an ancient lower and more fertile terrace, which may have been irrigated and used for cultivation and harvesting practices. Fixed mortars on large boulders were found there, as well as the site of Barranca Sur Room 1, a U-shaped space with an attached courtyard and a storage structure. The finds were scarce, although they made it possible to associate the site with a late occupation.

5.3 Temporal Dimension

With respect to the temporal dimension of the Cerro Colorado and surrounding area, the finds correspond to late times, and the dates place the occupancy around the fifteenth century AD (Table 1), so it can be assumed that most of the sites analyzed in the landscape were contemporary with each other in that century. However, the characteristics of the contexts allow us to argue that the radiocarbon dates represent events corresponding to the last moments of occupation of these structures, which must have been built and used gradually, being a lasting record of a process of occupancy of an inhabited and productive space. The presence of many large funerary cists – probably family tombs for prolonged use over time – and the use, in some cases, of domestic spaces for the burial of the dead, show a strong and daily link with the dead and with these places. In this sense, with respect to the temporality of the landscape, it is clear that ancestry was a key element in the definition of this local landscape.

5.4 Discussion

On the basis of this analysis, the discussion around the social and political practices of the local landscape of Cerro Colorado can be approached. We illustrate our reconstruction of this landscape in Figure 7. First, the absolute dominance of the field view from Cerro Colorado, mainly from Ridges 1 and 2 and the North and South sectors, stands out. This visibility made it possible to control movements in the immediate surroundings and also communication with other nearby sites, such as Loma de Ichanga and Cerrito Colorado of La Ciénaga de Arriba. The Central sector concentrated the highest number of people and had extra protection, both in terms of visibility and accessibility (Wynveldt et al., 2018). Considering the different sectors and their particular characteristics, the site guaranteed refuge not only to the particular group that inhabited that sector, but also to other families that used the rooms located in other sectors of the top, such as Room 2, where they had to rest, protect themselves from the cold nights and south winds, cook and consume some food, and also watch for movements and signals from the immediate surroundings or from other places in the valley.

Representation of the local landscape of Cerro Colorado La Ciénaga de Abajo and sites at the foot. See Figure 1 for its location.

The visual control from the Cerro Colorado made it possible to observe the flow of people, animals, and things, as part of those spatially distributed practices that made up the everyday local landscape. On the low terraces to the north and south of the Cerro and to the west of the river, which were easily irrigated by diverting water from Belén River, it would be possible to see many people carrying out agricultural tasks such as planting, caring for and harvesting various vegetables, mainly maize, and processing and storing them. Some people would also collect wild fruits, such as carob beans and chañar (Geoffroea decorticans), among others, which grow naturally in these fields, and wood for firewood and construction; others would maintain the water intakes and irrigation ditches; some people would also make use of the rural constructions, such as those at Lajas Rojas or Barranca Sur, to grind, make tools, eat, rest, and store the production. Camelids rearing may have been part of the daily tasks, so that on the riverbanks and hillsides one could observe herders, perhaps boys and girls, with their llamas; eventually, a hunter with his or her bow and arrow stalking a taruca (an Andean deer) or boys and girls chasing an armadillo. The flow of people between the Cerro Colorado and the river must have been constant, mainly for carrying water and partially processed food to the hilltop dwellings, probably in Belén jars. Less frequently, caravans of llamas would be seen arriving from nearby localities or from the puna, bringing obsidian nodules and vicuña’s wool and meat; or groups of caravaneers preparing the loads for a journey of days or months to other regions. These practices would evoke distant landscapes in those who had travelled or heard stories about that strange places.

The location of the tombs, both on the pukara itself and at the foot, and even inside the structures, indicates that all these daily practices involved the permanent presence of the ancestors. It is worth noting that both the construction techniques and the lithic raw materials are repeated in rooms and tombs. Although it is not possible to define these structures as monumental, the burial cists are visible to the naked eye; in some cases, they form large circles of double walls, and in others, only accumulations of stones. On the other hand, in burials located inside rooms, visibility is restricted. This would give more visibility to some tombs and, in other cases, more protection and privacy. Beyond these differences, the funerary space appears strongly linked to the domestic space; life and death intersected in everyday life and the space helped to evoke and perhaps invoke those who were no longer present. The dead could then act as protectors, as companions, and eventually as generators of rights for those who continued and succeeded them. In this way, ancestors gave a sense of temporal depth to those who experienced this landscape.

In conflict situations, the entire population had to take refuge at the top and, surely, communication with other sites was frequent, including visual (smoke, fire, and reflections) and auditory signals. The use of bows and arrows with obsidian projectile points must have been common in the defense of the site, although throwing and collapsing stones from above must have been equally effective. Walls, look outs, and parapets must have been very useful in defending the northern and eastern flanks of the site, while the western and southern sides were naturally protected. In addition, the protective agency of the ancestors would also play a very important role.

Finally, the analysis of the political aspect of the landscape of Cerro Colorado requires, above all, a differentiation, at least theoretically, between the pre- and post-Inka periods. If we place as a break point between one and the other the construction of Complex VIII – which, according to its special architectural characteristics, we hypothetically associate with an Inka influence – and we assume that the radiocarbon dates only indicate the last use of the site, we could argue that this pukara would have functioned as a pre-Inka local settlement in which a group with certain privileges – in terms of self-protection and, perhaps, the use of larger dwellings – would have inhabited the Central sector. In this sense, the local evidence is not consistent with a politically centralized organization; on the contrary, beyond the use of this more concentrated central space, the site itself does not constitute a large population nucleus; there are neither public spaces such as plazas and platforms nor concentrated and protected structures for the storage and redistribution of production.

The objects manufactured and used in and around the site, such as Belén and ordinary pottery, bronze objects, obsidian artifacts, and local lithic raw materials, would have implied some degree of craft specialization, and, in the case of metal and obsidian, their procurement from sources located at considerable distances. However, there is no evidence of a centralized organization of the production of these objects, but rather of manufacture on a domestic scale or, at most, by workshops of local artisans (Iucci, 2016). The use of plants – either as food or as construction materials – and animals – wild and domestic – by the people of Cerro Colorado and the surrounding area is similar to that of the rest of the late sites in the valley (Fuertes, Wynveldt, & López, 2023; Lorenzo & del Papa, 2018; Lorenzo, Iucci, & Lorenzo, 2019; Valencia, 2018), and they would have been obtained locally without any inconvenience.

If we take into account that Cerro Colorado occupied a central role in the southeast of the valley, including the areas of Ichanga, La Ciénaga de Arriba, Puerta de San José, and La Estancia, it is possible that, from the time of the arrival of the Inka Empire to the region, local leaders were linked with state officials. The continued occupation of the site throughout the fifteenth century and the construction of Complex VIII in the Central sector, with its large aligned rooms, may be evidence of a negotiation between local groups and the Inka state. In particular, the occupants of this sector of the site were able to exert great political power in this area. The Inka road or qhapaq ñan would have passed near the site and must have been the main means of connection with other localities in the valley, as Quillay, only 2 h of walking to the north, and with a new regional political center: El Shincal de Quimivil, less than a day’s journey to the southwest.

6 Other Local Landscapes

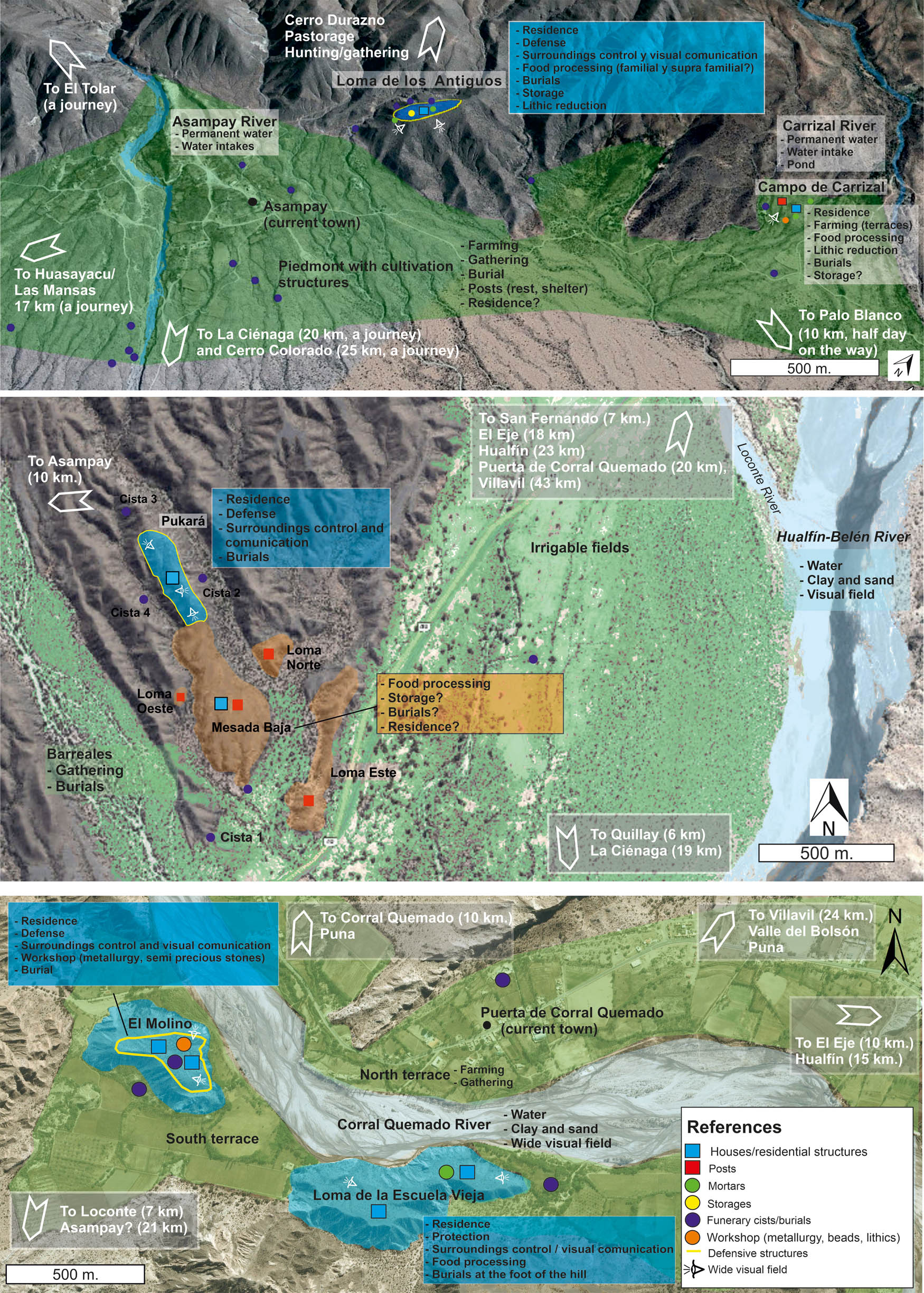

The research carried out in other localities of the Hualfín Valley provides sufficient information to define some important aspects of other local landscapes (Figure 8).

Representation of late local landscapes. Top: Asampay. Center: Palo Blanco. Bottom: Puerta de Corral Quemado. See Figure 1 for the location of each.

6.1 Asampay

Asampay is one of the most studied archaeological zones in the region. It is located on the foothills of the western mountain range of the valley, at the outlet of a ravine from which water is obtained throughout the year. There are two late sites that stand out: Loma de los Antiguos, a pukara located on a high hill; and Campo de Carrizal, 2 km to the north, a large area of cultivated terraces and scattered rooms. The chronology obtained for these two sites presents calibrated ranges with greater probabilities for the end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth century AD.

Loma de los Antiguos is the only concentrated late settlement in the Asampay area (Figure 3a). Access is very difficult, as it has steep slopes and three walls surrounding the summit. From there, there is a full view of the valley. There are 45 structures, some of them forming groups of two, three, or four rooms, especially in the central sector. Belén pottery, together with associated ordinary pottery, is found in all the excavated rooms, while there are few vessels of “foreign” styles, such as Santa María, Famabalasto Negro Grabado, and Sanagasta. The lithic objects were manufactured from local raw materials, with the exception of projectile points and other artifacts of obsidian, preferably from the Ona source (Flores, Morosi, & Wynveldt, 2010). The archaeofaunal materials correspond mostly to artiodactyls – camelids and/or deer – and among the plant remains, maize, peanut, and carob beans were found stored in large ordinary pots (González & Pérez Gollán, 1968; Wynveldt, 2009). In addition, it was possible to identify numerous fire contexts, which, together with the seven skeletons without skulls found in several tombs in the area and at the site itself, led González to argue that they were the result of a violent attack that included the decapitation of some of the inhabitants (González, 1979).

Campo de Carrizal consists of several stone rooms of various morphologies and sizes, scattered among numerous cultivation terraces on the foothills descending from Cerro El Durazno. In association with this site, ditches taking water from the Carrizal river and a pond have been recognized (Sempé, 1999). In addition to this, remains of metallurgical practices were found in a large structure (Zagorodny, Angiorama, Becerra, & Pieroni, 2015). This evidence leads us to interpret this site as a productive space. In addition to Campo de Carrizal, the whole piedmont from there to the south, passing through Asampay and the following ravines, to Huasayacu-Las Mansas, shows large areas of cultivation terraces. Scattered randomly across these fields, and even on the slopes of the Loma de los Antiguos, numerous late tombs were found, most of which use the large granite blocks scattered across the fields in the area as part of their structure. With the exception of two tombs with Sanagasta-type pieces (Figure 2h), a ceramic style typical of the southern valleys, the rest had Belén vessels as funerary accompaniment in single or multiple burials. Some of these tombs included copper, bronze, and even a gold object, and, in some cases, remains of textiles, baskets, and arrows.

The archaeological landscape of Asampay can be described on the basis of the following set of fundamental elements (Figure 8, top): the defensive settlement as the main population nucleus, the agricultural fields, the proximity to permanent water sources, and the presence of the ancestors also inhabiting the spaces of daily activity. On the other hand, practically the same series of elements of the material culture observed at Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo are repeated. Among the particularities of this area are the burials without skulls – which according to González (1979) would be linked to inter-group conflicts – and the absence of direct Inka evidence, despite the chronological contemporary with Inka presence in the region. The agricultural infrastructure, although it surely has its origin in pre-Inka times, was also used in Inka times, and perhaps improved and expanded.

6.2 Palo Blanco

This area is located in the central-eastern sector of the valley, close to the west bank of the Hualfín-Belén river, at its confluence with the Loconte river. From the systematic surveys carried out since 2009 throughout the area, it was possible to identify several sets of architectural structures: Mesada Baja, Pukará, Loma Norte, Loma Este, and Loma Oeste, as well as burial cists at the bottom of the ravines, on the mesadas and lomadas, and even inside a room (Figure 8, center). The Mesada Baja is a large flat hill about 10 m high with several clusters of isolated rooms combining rectangular and circular shapes of varying sizes. The Pukará sector is a narrow hill that rises 40 m above the Mesada Baja. It has remains of walls on its slopes and is the sector with the highest concentration of structures. However, unlike Cerro Colorado and Loma de los Antiguos, it does not present agglutinated rooms, but an isolated pattern, with separated structures or some connected to a courtyard.

Excavations at the Pukará and Mesada Baja revealed some interesting differences between the two spaces. While in the rooms excavated in the Pukará (Rooms 2 and 8) there was a significant amount of domestic consumption materials – maize and camelid remains, Belén, Santa María and ordinary vessels, and obsidian flakes – in the excavation of Room 20 of the Mesada Baja (Figure 3d), no evidence of consumption practices has been found so far; besides, there is a significant proportion of circular rooms in this Mesada, absent in the Pukará, which we have associated with grain processing activities, particularly maize milling. The two radiocarbon dates obtained – one for the Mesada Baja and the other for the Pukará – coincide with an occupation around the beginning of the fifteenth century. Based on this information, it was proposed that the two sectors could correspond to places where different practices were developed, more linked to productive tasks in the Mesada Baja, and to households and defense in the Pukará. Regarding the funerary contexts known for the area, in the 1920s, the explorer Wladimir Weiser excavated seven circular burial cists, whose human remains were accompanied by Belén pottery, Famabalasto Negro Grabado (Figure 2l) and some pieces associated with the Inka expansion in the NOA, such as the Yocavil Tricolor type (Figure 2n); and in San Fernando, a few kilometers to the north, pieces of Inka style were also found (Figure 2p and q), with “Belén Inka” (Figure 2o) and Famabalasto Negro sobre Rojo (Figure 2m), also linked to Inka times.

The visibility achieved from the Pukará made possible not only an effective control of the immediate surroundings, but also the visual interception of practically all north to south circulation routes in the valley. With respect to the ravines at the foot of the hills and the terraces of the Hualfín and Loconte rivers, they were places associated with water and the practices linked to its administration, and therefore related to agricultural practices, in addition to the collection of wild fruits in the bush and carob forests. These places were also chosen for the burial of the dead and the rituals associated with them. In relation to the Inka presence at Palo Blanco, the tombs with objects of its influence confirm the use of the area during that period; this interpretation makes sense considering that the Inka road would have crossed this area, on its route between the Inka centers of Hualfín and Quillay (Raffino et al., 2001).

6.3 Puerta de Corral Quemado

This is a very relevant locality for the regional landscape network. First, it is the main node in terms of the number of localities it connects and the control of traffic to and from the puna (Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018). In addition to this particularity, there are other important aspects, such as the presence of Santa María type vessels, both in the settlements and in the tombs, associated with Belén materials (Iucci, 2016). Two late settlements were recorded at this locality (Figure 8, bottom). Loma de la Escuela Vieja is located on a flat hill with two levels – 25 and 50 m high – and has 59 scattered rooms (Wynveldt & Iucci, 2015). El Molino, located just 500 m west of the previous site, on a 70 m high hill, has very different and exceptional characteristics. It has more than 110 structures, mostly agglutinated, some of them between 10 and 20 m on a side, built with high walls – unlike typical late constructions, usually semi-subterranean – and with morphologies not observed in any other site in the valley (Figure 3b). From the radiocarbon dates obtained in both settlements, it has been possible to prove that their occupancies were contemporary. At the foot of these two sites, there are currently large farms irrigated by the Corral Quemado River, one of the most important tributaries of the Hualfín-Belén. The present-day village is located on the northern bank of the river. All this space on the lower terraces on both sides of the river must have been an area used for crops, dwellings, corrals, and burials in pre-Hispanic times, although due to its current use, no archaeological structures have been recorded.

Excavations in Room 6 at Loma de la Escuela Vieja determined that this sub-circular structure was used for grinding maize. In Room 34, at El Molino, remains of Belén, ordinary, Santa María, and possibly Inka ceramics were found. They were also found quinoa and carob seeds, vicuña remains, aragonite beads with different degrees of manufacture, Ona obsidian projectile points, a stone mortar, and a small gold object, possibly a reservoir or ingot. In the southwest corner, delimited by a stone wall, the burial of a woman with a Belén bowl as an offering was discovered (Iucci, Cobos, Moscardi, & Perez, 2020). In Room 8, the burial of a child was recovered inside an ordinary urn, remains of metallurgical production, a folded and cut gold object inside a ceramic pot, several Spondylus beads – an absolutely exceptional find in the NOA, beyond the high mountain sacrifices or capacocha – as well as aragonite and turquoise beads and evidence of their manufacture, which indicate that this area probably was a workshop dedicated to the production of objects of high symbolic value, possibly linked to an elite group related to the Inka state. In addition to this, González excavated Room 98, a structure with a very particular morphology, which, according to this author, would have had a ceremonial function (González, 1974) (Figure 3b). In this structure, there were a large amount of late ceramics – including an atypical Santa María vessel (Figure 2i), found below the room’s floor – and refractory materials, which, like findings from Room 8, would have been linked to metallurgical practices. However, the configuration of this space, whose access is mediated by a long and narrow corridor leading to a courtyard, does not lead us to think of public ceremonial practices, but quite the contrary. González also carried out excavations in Room 110, where he found the burial of another child in an ordinary urn.

As mentioned for Cerro Colorado and Palo Blanco and some cases at Asampay, the typical structure of the late tombs at Puerta de Corral Quemado is the circular cist. Several urn burials were also found. There were sectors away from the main settlements that were used as burial spaces, and also isolated burials, some at the foot of the settlements and several inside the structures. The great quantity of Santa María type vessels observed in the domestic contexts is also notable in the tombs, where they are associated with Belén, ordinary, and Famabalasto Negro Grabado ceramics.

In summary, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the late landscape of Puerta de Corral Quemado had two main centers: El Molino, a settlement probably inhabited by a group that dedicated part of its time to the manufacture of objects of high symbolic value, possibly an elite group linked to the Inka state; and Loma de la Escuela Vieja, occupied by groups of families that used isolated rectangular rooms as dwellings and other structures for the processing of foodstuff. From both settlements and from the hills around them, it was easy to control the movements of the immediate surroundings and the routes from the north – Corral Quemado, Villavil, and the roads to the puna and the Bolsón Valley – the east – Hualfín and El Eje de Hualfín – and the south – San Fernando, Palo Blanco, and the entire southern sector of the valley. At the foot of the settlements, the terraces of the Corral Quemado river on both banks were probably used for cultivation, and the flow of people and things between these areas and both settlements must have been permanent. Places for the dead were located between (and within) the dwellings, at the foot of the settlements and in certain places in the countryside. The agglutinated pattern of El Molino and the morphology of its constructions make this site very different from Loma de la Escuela Vieja and the rest of the local late settlements. These differences necessarily reflect also dissimilar social relations, perhaps due to power inequalities between the groups that occupied both sites. Taking into account the evidence that can be related to an Inka influence at El Molino, we can assume, still as a hypothesis, that this site may have functioned as a center of power in the area, with which the Inka would have negotiated the conditions for the annexation of this part in the North of the valley to their State, at least in the first decades of the conquest.

7 Discussion: Autonomous Local Landscapes and Political Changes in Imperial Times

As a result of the analysis of the relationships in the whole set of late local landscapes in the Hualfín Valley, we have observed that, beyond the particularities that define each area, there is a series of recurrences in terms of the elements of each network and their relation. If we extend our gaze to the rest of the valley, we see that these recurrences are also observed in other localities. First, the sites are preferably located in the proximity of the most important rivers, such as the Hualfín-Belén, Villavil, Corral Quemado-San Fernando, Loconte, Ichanga, Condorhuasi, and Yacoutula, or the watercourses that flow from the ravines at the foot of the Cordón de la Falda-El Durazno, on the western side of the valley, such as Carrizal, Asampay, and Huasayacu-Las Mansas. In all these zones, there are areas of great agricultural potential at the foot of the main villages.

As evidenced by the shared architectural, funerary, and material culture patterns, late local populations had regular and even daily relationships. In this sense, the distance relations between localities, calculated through least-cost routes (Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018), allowed us to estimate that certain settlements such as Cerro Colorado, Cerrito Colorado, Loma de Ichanga, and La Estancia may have been linked by very frequent, even daily relationships. On the other hand, the links between these and La Toma, Corral de Ramas, or Huasayacu probably involved certain logistics for the movement. But, to link Palo Blanco or Asampay with the sites of La Ciénaga, a half-day’s walk was necessary. The relations between Asampay and Palo Blanco, although involved some logistics for movement, were probably frequent, while the link between La Ciénaga and Puerta de Corral Quemado or the links between Villavil, Puerta de Corral Quemado, El Eje, and San Fernando meant travelling distances of more than 10 km, which required several hours of walking. In these cases, the relationships must have involved aspects more closely linked to exchange activities, with caravans transporting different raw materials and vessels containing foodstuffs or manufactured products. More than a day’s journey could mean a certain autonomy between localities and the segregation of villages into different daily circuits.

If we address the problem of the sociopolitical landscape, it is essential to consider the context of conflict in which the late settlements would be framed. In this sense, not only the defensibility of the sites must be taken into account but also the visibility to ensure effective visual control of the surroundings and to enable intervisibility relations between the different settlements, in order to exchange information (Wynveldt & Sallés, 2018). The control of circulation through the valley is another political aspect that reveals the importance of each locality in the network. On this point, the prominence of Puerta de Corral Quemado is observed, which links all the localities and routes that pass to and from Corral Quemado, Villavil, and the Southern Puna. The relevance of Palo Blanco, a node in the relationship between the localities to the north and south of the valley, and La Ciénaga, where all the routes in the southern sector of the valley are linked to the routes that cross Palo Blanco from (or to) the north, can also be observed. Regarding the analysis of the possible routes that could have linked the valley with neighboring regions – Southern puna, the Cajón and Yocavil valleys, the Andalgalá area, Tinogasta, and La Rioja – localities as Corral Quemado, Villavil, Hualfín, La Toma, and Puerta de San José were particularly important, as they are located close to the “natural” entrances to the valley.

This whole network of regional relations can be defined, in terms of time, in a period between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries AD, including the moments immediately before, or related to, the incorporation of the valley into the Inka Empire and a purely Inka period. Based on the material evidence analyzed here, we can affirm that the political landscape for the Late pre-Inka period would have been characterized by decentralized power. The local landscapes would have been politically autonomous landscapes. This is evident from the lack of centralization in terms of the manufacture and circulation of goods – ceramics, obsidian, bronze, and wood – that appear in all the Late pre-Inka sites in the valley; in the tombs, that show few differences in terms of their size, constructive structure, and grave goods; and in the absence of sufficiently prominent population centers and differentiated architectural spaces (beyond those that we can link to Inka times). Late local pre-Inka groups were farmers, with lineages with more or less prestige and power, who interacted with other groups and landscapes in multiple ways, peacefully or violently, and could have depended on exchange to obtain certain resources – vicuña, obsidian, and aragonite – but did not depend on others politically.

Possibly, in the first half of the fifteenth century, the process of incorporating the region into the Tawantinsuyu started, that significantly modified the landscape as a result of the construction of the qhapaq ñan, between Hualfín Inka (Lynch, 2012), passing through Quillay, where a metallurgical production center comprising 32 smelting furnaces and an Inka way-station or tambo operated (Spina, 2017), and El Shincal de Quimivil (Raffino et al., 2001). The state related to different factions of power of the local groups – as was proposed for the Cerro Colorado de La Ciénaga de Abajo and El Molino de Puerta de Corral Quemado – and maybe promoted certain leaderships from their incorporation into the state structure. This strategy can be observed with different degrees and scales, in the case of the collas and lupaqas of Titicaca. These groups, unlike what is traditionally maintained from ethnohistoric chronicles, would not have formed large hierarchical sociopolitical organizations (Arkush, 2009; Frye & Vega, 1988). In this scenario, the state did not have a hierarchical reference from which it would negotiate its incorporation; therefore, the Inka had to make alliances with determined leaders and establish new hierarchies and political centers. Besides, it is interesting to observe the contrast between the different expansive ways of the Inkas in the Kollasuyu. In some cases, where there were large local centers, such as Tarapacá Viejo in Northern Chile (Zori and Urbina 2014), or the Pucará de Tilcara in the Quebrada de Humahuaca in Northwestern Argentina (Cremonte et al., 2019), the state intervened directly, transforming the sites into political and administrative centers, taking advantage of their strategic location to link them with other important political or administrative centers or with strategic resources. At the other end of the spectrum of imperial strategies is the alliance of the Inkas with local chiefs of the chaco-santiagueño plains, 300 km to the east of the classically defined border for the Inka Empire. Based on numerous Inka findings at the Sequía Vieja site (Santiago del Estero), it is argued that the local chiefs had received all kinds of sumptuary objects, normally associated with the Inka elites, as part of a state negotiation strategy (Taboada, 2014), perhaps a change in groups of workers or warriors who were moved to the Andean region, as evidenced by the ceramics of Santiago del Estero types found in different parts of the NOA (Figure 2m and n).

Returning to our case of the Hualfín Valley, we propose that in the second half of the fifteenth century, the Inka presence in the region was definitively consolidated. El Shincal de Quimivil was already the most important Inka center in the region, and would have functioned as a provincial capital of the state (Raffino et al., 2015). Although the links between the main late localities probably continued, the centrality acquired by the Inka road and the new facilities substantially modified the relationships in the local network. Especially, El Shincal, due to its important political, economic, and ceremonial role, would have led to the intensification of relations on an interregional scale (Moralejo & Gobbo, 2015; Raffino et al., 1997; Wynveldt et al., 2020). The local pukaras that continued to be occupied in Inka times – for example, Cerro Colorado of La Ciénaga de Abajo and Loma de los Antiguos – would now be part of the control of the Inka landscape, delegated to allied local leaders or mitimaes that replaced rebellious groups. One of the most important local political centers at this time may have functioned at El Molino, at least during the first half of the fifteenth century AD. In this site, no specific storage spaces were found that could lead to the interpretation of the collection and redistribution of a significant food production; this must have been carried out by the state in its administrative centers at Hualfín Inka or El Shincal de Quimivil. On the other hand, although Puerta de Corral Quemado is not a particularly productive place, like Asampay, Carrizal or the Huasayacu-Las Mansas area, its location at the access to the puna makes it a fundamental node in the regional landscape. Therefore, the place occupied by El Molino at the time of the region’s incorporation into the state administration must have been related to its strategic importance in the circulation between the valleys and the puna. The local leaders of Puerta de Corral Quemado may have played an important role in the link with the state, both in the organization of the labor force and in maintaining political stability. In exchange, the state made them participants in the consumption of certain items exclusive to the Inka elites, as well as giving them control of resources of great symbolic value, for example, the exploitation of gold from nearby mines (Iucci, Becerra, Wynveldt, Fuertes, & Sallés, unpublished data).

Finally, Cerro Colorado de La Ciénaga de Abajo, the site we have focused on in this study, may have played a similar role in controlling the local people in the southeast of the valley and the traffic along the Belén River. However, in this case, those who would have mediated with the state made use of a particular space of the site – the Central sector – especially protected for the construction of a complex of rooms that allowed them to develop certain practices on a supra-familial scale – such as the production of chicha – important for exerting this function of power, although very modest as a demonstration of political hierarchy.

The absence of centralized political institutions and the tendency toward corporatism that would have characterized the local groups, expressed in the widespread decentralization and relative homogeneity of all the material elements analyzed, must have made it difficult for both the Inka state and local leaders to establish a hierarchical local political representation. Therefore, it is possible that the evidence of internal inequality and the subtle elements of Inka influence observed in the local sites reflect those moments of transition toward full political control by the state, later crystallized in the centrality of El Shincal de Quimivil and the qhapaq ñan.

Abbreviations

- NOA

-

Northwestern Argentina

- CC

-

Cerro Colorado

- LI

-

Loma de Ichanga

- PB

-

Palo Blanco

- PCQ

-

Puerta de Corral Quemado

- SF

-

San Fernando

- MLP-Ar CMB

-

Muñiz Barreto Collection, La Plata Museum

Acknowledgements

To Bárbara Balesta and Nora Zagorodny, who carried out, directed and encouraged much of the research presented here. To the editors and anonymous reviewers, whose comments and corrections allowed us to greatly improve the manuscript.

-

Funding information: This research was financed by Universidad Nacional de La Plata Project 11/N851), CONICET (Project PIP 2015-2017), and Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación (Project PICT-2015-3716).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Acuto, F. (2012). Landscapes of inequality, spectacle and control: Inka social order in provincial contexts. Revista de Antropología, 25, 9–64.10.5354/0719-1472.2012.20256Suche in Google Scholar

Acuto, F. A. (2007). Fragmentación vs. Integración comunal: Repensando el período tardío del Noroeste Argentino. Estudios Atacameños, Arqueología y Antropología Surandinas, 34, 71–95. doi: 10.4067/S0718-10432007000200005.Suche in Google Scholar

Acuto, F. A. (2011). Encuentros coloniales, heterodoxia y ortodoxia en el valle Calchaquí Norte bajo el dominio inka. Estudios Atacameños, 42, 5–32. doi: 10.4067/S0718-10432011000200002.Suche in Google Scholar

Acuto, F. A. (2013). ¿Demasiados Paisajes?: Múltiples teorías o múltiples subjetividades en la arqueología del paisaje. Anuario de Arqueología, 5, 31–50.Suche in Google Scholar

Alvarez Larrain, A., & Greco, C. (Eds.). (2018). Political landscapes of the late intermediate period in the South-Central Andes. The pukaras and their hinterlands. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-76729-1Suche in Google Scholar

Anschuetz, K. F., Wilshusen, R. H., & Scheick, C. L. (2001). An archaeology of landscapes: Perspectives and directions. Journal of Archaeological Research, 9(2), 157–211.10.1023/A:1016621326415Suche in Google Scholar

Areshian, G. E. (2013). Empires and diversity: On the crossroads of archaeology, anthropology, and history. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press at UCLA.10.2307/j.ctvdjrqgqSuche in Google Scholar

Arkush, E. (2009). Pukaras de los Collas: Guerra y poder regional en la cuenca norte del Titicaca durante el Periodo Intermedio Tardío. Andes, 7, 463–479.Suche in Google Scholar

Aston, M. (1985). Interpreting the landscape. Landscape archaeology and local history. London: Routlege.Suche in Google Scholar

Balesta, B., Valencia, M. C., & Wynveldt, F. (2014). Procesamiento de maíz en el Tardío del valle de Hualfín ¿Un contexto doméstico de producción de chicha? Arqueología, 20 (Dossier), 83–106. doi: 10.34096/arqueologia.t20.n0.1581.Suche in Google Scholar

Balesta, B., & Zagorodny, N. (Eds.). (2010). Aldeas protegidas, conflicto y abandono: Investigaciones arqueológicas en La Ciénaga, Catamarca, Argentina (1st ed.). La Plata: Ediciones Al Margen.Suche in Google Scholar