Abstract

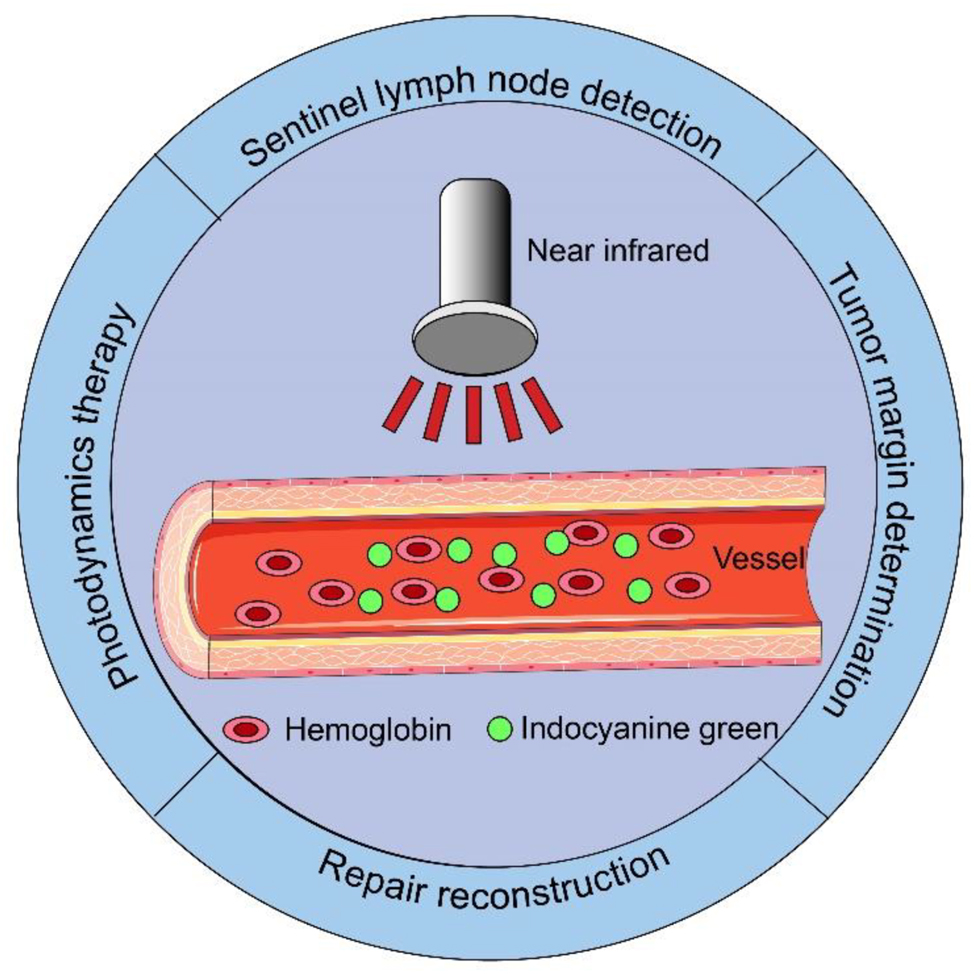

Indocyanine green is a cyanine dye that displays fluorescent properties in the near-infrared region. Indocyanine green has good water solubility and can bind to plasma proteins in the body. After binding, it can display green fluorescence when irradiated by near-infrared fluorescence. Owing to its good imaging ability and low side effects, indocyanine green is widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of various tumors. Indocyanine green-assisted sentinel lymph node biopsy helps determine clean tumor boundaries, helps surgeons remove primary tumors completely, assists in microvascular anastomosis in head and neck repair and reconstruction, reduces operation time, evaluates blood perfusion to monitor flap status. In addition, indocyanine green has great potential in photodynamic therapy to specifically kill tumor cells. However, despite the benefits, studies regarding the application of indocyanine green in oral cancer are limited. Therefore, we conducted a literature review to explore the application of indocyanine green in oral cancer to benefit clinicians involved in the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

Introduction

Oral cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors of the head and neck. Its primary causes are smoking, alcohol consumption, and areca nut chewing. The highest incidence of oral cancer is reported in South and Southeast Asia, parts of Western and Eastern Europe, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific region [1]. According to the global cancer statistics in 2020, 377,713 new cases of oral cancer were diagnosed worldwide, accounting for 2 % of all new cancer cases. Of 377,713, 177,757 resulted in death, accounting for 1.8 % of all new cancer deaths [2]. At present, the main treatment for oral cancer is surgery-based comprehensive sequential therapy [3]; however, the 5-year survival rate in these patients is only 58 % [4, 5]. Therefore, developing new effective methods for the diagnosis and treatment of oral cancer is crucial to prolong patient survival.

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a water-soluble anionic amphiphilic tricarbocyanine dye, with a molecular weight of 774.96 g/mol and a fluorescent diameter of 1.2 nm [6]. It has been 68 years since ICG was first developed by Kodak in 1955 [7]. Owing to its good imaging ability and low side effects, ICG is the only near-infrared (NIR) imaging dye approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for clinical application in 1956 [8]. When intravenously injected, ICG binds to plasma proteins, and the protein-bound ICG produces fluorescent signals but does not destroy the structure of the plasma proteins [9]. The peak spectral absorption of ICG in the blood occurs at 800–810 nm; it displays a fluorescence signal when irradiated by an external invisible NIR light (700–900 nm) [10]. ICG is widely used in the visualization of various organs and tissues, such as the detection of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) [11], identification of solid tumors [12], and judgment of tumor boundaries [13]. In addition, owing to its excellent combination with plasma proteins, ICG is used to monitor blood perfusion in real-time in head and neck reconstruction [14]. Based on this principle, ICG is also helpful in detecting perforator vessels in tissue flaps, designing flaps, and evaluating the blood supply of vascular anastomosed regions [15] (Figure 1).

Application of indocyanine green in oral cancer.

There have been significant technological advancements in surgical robotics in recent years. The fourth generation of the da Vinci robotic system is equipped with a NIR camera, and NIR fluorescence imaging combined with surgical robots can effectively play the role of ICG fluorescence imaging [16]. This combined effect can help surgeons improve the success rate of surgery, thereby prolonging patient survival. As a non-surgical treatment, ICG converts NIR light into heat and toxic chemicals that can be used to activate photosensitizers (PS), combined with nanoparticles, to specifically kill tumor cells. Therefore, ICG can be used for photothermal therapy and photodynamic therapy (PDT) [17]. In this study, we used “Indocyanine green” and “Oral cancer” as keywords to retrieve relevant high-quality literature on the application and development of ICG in oral cancer from the Web of Science database.

SLN detection

Cervical lymph node metastasis is the most significant prognostic factor in patients with oral cancer. Occult lymph node metastasis occurs in approximately 20–30 % of patients with early N0 oral cancer. Hence, some studies recommended prophylactic neck lymph node dissection for patients with early N0 oral cancer [18]. However, prophylactic dissection may cause complications such as facial paralysis and shoulder dysfunction. Therefore, it is worth investigating the applicability of prophylactic neck lymph node dissection to all patients with early oral cancer. SLNs, initial lymph nodes that receive drainage from the primary tumor, appear to solve this problem; SLN biopsy can prevent overtreatment of patients with early-stage oral cancer. A multicenter trial conducted in Japan found that SLN biopsy-guided neck lymph node dissection could replace traditional selective neck lymph node dissection for patients with early oral cancer, and the former could also reduce harm to the physiological function of patients [19].

ICG

ICG is a commonly used fluorescent contrast agent to map the lymphatic system. It plays an important role in the diagnosis of lymphedema, which is currently diagnosed using magnetic resonance lymphography and Doppler ultrasound (DUS). While the former can display lymph nodes and lymph vessels using contrast agents combined with fat-suppressed T2-weighted images, the latter can determine the nature of the lymph nodes through the Doppler effect produced by human blood flow. However, both have certain drawbacks. The former cannot be repeatedly applied and real-time dynamic monitoring of lymph nodes is limited due to its high cost of use, and the exploration range of the latter is limited [20]. With no risk of radiation exposure and the ability to dynamically monitor lymph node drainage, ICG is beneficial in the diagnosis of lymphedema. ICG binds to the lymphatic proteins; as edema progresses, the reflux of ICG in the lymphatic vessels slows down, prolonging the flow time. This enables accurate diagnosing and grading of lymphedema using ICG angiography (ICGA) [21]. In Unno et al.’s [22] study, 12 patients with secondary lymphedema underwent ICG lymphangiography, and four abnormal lymphatic drainage patterns of lymphedema were observed. The findings confirmed that ICG lymphangiography can be used to detect secondary lymphedema lesions. Yamamoto [23] used ICG to diagnose primary lymphedema, with a sensitivity and a specificity of 100 % each. ICG fluorescence angiography is a minimally invasive and safe technique that can be used to assess the severity of lymphedema and determine its prognosis.

Cells and tissues often do not have autofluorescent properties. NIR fluorescent contrast agents, therefore, play a significant role in SLN visualization, as they not only maximize the signal-to-noise ratio but also enhance tissue contrast. ICG is a widely used fluorescent contrast agent to detect SLN in different cancers. When ICG is injected into normal tissues surrounding the tumor, it binds to plasma proteins in the interstitial space to form macromolecular compounds, which do not diffuse freely into the surrounding tissues. Once it enters the lymphatic tissue for enrichment, and under the irradiation of NIR light with a specific wavelength, ICG-enriched sites are stimulated to produce fluorescence signals. These signals are then transmitted to a computer system for processing and imaged through the fluorescence imaging system of the NIR camera for SLN localization.

In SLN biopsy of patients with early oral cancer, using ICG alone for SLN localization is reportedly not sufficient. For instance, Al-Dam et al. [24] used ICG to perform SLN biopsy on 20 patients with early oral squamous cell carcinoma and found that although sentinel nodes were detected in all patients (100 % specificity), the sensitivity was only 50 %. This was because 50 % of the patients had false negative results, suggesting that the reliability of SLN biopsy after ICG imaging could not be verified. On the contrary, a meta-analysis conducted by Chen et al. [25] found that the sensitivity and specificity of ICG alone in detecting SLNs in patients with oral cancer were 86 and 92 %, respectively, suggesting the effectiveness of ICG alone in SLN detection. However, relevant studies on the use of ICG alone for SLN biopsy are limited. Therefore, further studies should be conducted to validate the above findings. At present, ICG is mainly used in combination with other tracers or auxiliary equipment for SLN detection (Table 1).

SLN detection.

| Detection method | Number of patients | Concentration | Dose | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICG | 20 | 0.5 mg/kg | 2 mL | Sensitivity 50 %, specificity 100 %, positive predictive value 100 %, negative predictive value 75 % [24] |

| 18 | 5 mg/mL | 2 mL | Out of the 18 patients, preoperative CTL was able to map SLNS in 16 patients (89 %). Intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence successfully identified and removed at least one SLN in all of these 16 patients [26] | |

| 20 | 5 mg/mL | 2 mL | SLNs were detected by CTL in 19 of the 20 patients (95.0 %). All SLNs could be detected 2 min and 3.5–5 min after contrast medium injection, and CTL-enhanced SLNs could be identified intraoperatively as fluorescent lymph nodes [27] | |

| 10 | 2.5 mg/mL | 1 mL | SLN was detected in all patients at 1.2 SLN per person. Mean time was 171.0 (68.0–312.0) s. Mean SBR (signal-to-background ratio) was 5.62 (3.51–7.91) [28] | |

| 9 | 2.5 mg/mL | 2 mL | Upstaging rates 22.2 %, sensitivity 100 %, specificity 91.5 %, and negative predictive 100 % [29] | |

| ICG+MB | 26 | (ICG) 5 mg/mL | 1 mL | Sentinel nodes were successfully harvested in all 26 cases (100 %) [30] |

| (MB) 1 mg/mL | 1.5 mL | |||

| ICG+99mTc | 20 | 5 mg/mL | 86.5 MBq | SLNs could be detected in all 20 patients (100 %) [31] |

| 16 | 5 mg/mL | 0.4 mL | In the 16 patients, NIR fluorescence imaging was able to detect 35 lymph nodes, while gamma-ray probes could identify 28 of them. All nodes emitting detectable gamma rays were observed with NIR fluorescence signals [32] | |

| 19 | 1.25 mg/mL | 80 MBq | The fluorescent nature of ICG‐99 | m Tc‐nanocolloid supported in vivo and ex vivo identification of the tracer deposits surrounding the tumor. Pathological examination indicated that in 66.7 % (8/12) all fluorescence was observed within the tumor resection‐margins [33] | |

| 14 | 5 mg/mL | 77 MBq | 43 SLNs could be localized and excised with combined radio- and fluorescence guidance [34] | |

| 30 | 0.25 mg/mL | 0.2 mL | SLNs could be detected by dual tracer in 29 of 30 patients, and a total of 94 isolated SLNs were detected (mean 3, range 1–5). Eleven of 94 SNs (12 %) could only be identified in vivo using NIRF imaging, and the majority of those were located in level 1 close to the primary tumor [35] | |

| 9 | 2.5 mg/mL | 85 MBq | Thirty SLNs were detected in 9 patients (mean 3.3) [36] |

-

ICG, indocyanine green; CTL, computed tomography lymphography; SLN, sentinel lymph node; NIR, near infrared; MB, methylene blue; Tc, technetium.

The penetration range of ICG is <5 mm. Therefore, radioactive signals can penetrate through the skin but not directly through the sternocleidomastoid and platysma muscles. This makes it difficult to locate SLNs directly through the neck skin. When SLNs are detected in patients with early oral cancer, a neck flap surgery is often performed. After the flap is opened, ICG (<2 mg/kg) is injected around the tumor at five different sites, and the SLNs are then located using an infrared camera. However, this method causes great trauma to patients, especially to those with negative SLNs. In computed tomography lymphography (CTL), the iodine contrast agent is directly injected into the patient’s lymphatic vessels. Once the agent accumulates in the vessels, the image of the lymphatic drainage is obtained by CT, which can be used for preoperative SLN localization. In recent years, using CTL with ICG for SLN detection has gained increased attention from researchers [26, 27, 37]. ICG fluorescence imaging-guided SLN biopsy has developed into a new non-radioimmunoassay technique. Honda et al. [26] investigated the feasibility of using CTL with ICG for SLN detection in patients with oral cancer. The study included 18 oral cancer patients who underwent CTL a day before surgery. During surgery, ICG fluorescent dye was injected around the primary tumor according to the imaging results. The NIR fluorescence camera was used to search for fluorescence signals. Based on the signals observed, the SLNs were labeled and resected. Of 18, the SLNs of 16 patients (89 %) were located during preoperative CTL examination and by ICG fluorescence signals. Five of the 16 patients were found to have metastasis in the postoperative pathological examination, suggesting that this technique has a high application potential in neck dissection of early oral squamous cell carcinoma. As the SLNs were located preoperatively, the SLN biopsy was performed using a small incision according to the preoperative localization and fluorescence signal. Most importantly, this technique reduces trauma to patients. Sugiyama et al. [27] compared the effects of using CTL at different time points after injection of iodine contrast agent to detect SLNs and found that CTL had the best detection effect on early SLNs after 2 and 5 min of injection of the agent. In addition, three-dimensional (3D) imaging was performed on the patient’s imaging results before surgery, and it was found that the difficult-to-detect tongue lymph nodes could be well identified by analyzing the 3D reconstruction images. Timely intervention of metastatic lymph nodes can avoid poor prognosis. These findings indicated that CTL combined with ICG can effectively assist SLN detection in patients with early oral cancer. However, CTL has some limitations, such as its lack of applicability in patients with iodine allergy. Cone-beam CT (CBCT) can avoid the effects caused by iodine allergy. Muhanna et al. [38] successfully used CBCT preoperative 3D imaging and intraoperative near-external red light-guided ICG fluorescence imaging in rabbit SLN biopsy. CBCT and micro-CT showed comparable performance in lymph node detection, with a sensitivity and specificity of 87.5 and 100 %, respectively. This indicated that 3D reconstruction technology combined with fluorescence imaging is a potential new research direction in the future.

Owing to their high accuracy, minimal invasiveness, and less postoperative complications, surgical robots are increasingly used in the treatment of oral cancer. The fourth generation of the da Vinci robotic surgical system is equipped with NIR fluorescence imaging. During surgery, the surgeon no longer needs a hand-held NIR camera to find fluorescence signals but instead can switch between the normal mode and fluorescence mode through the robot console operation. In the fluorescence mode, surgeons can evaluate the range of lymph node metastasis in real-time through the fluorescence signal image. The da Vinci surgical robot can help surgeons accurately and rapidly perform SLN biopsies [39]. Chow et al. [28] combined ICG and robotic NIR fluorescence imaging (Firefy®) for SLN biopsy in 10 patients with cN0 oral cancer. SLNs were detected in all patients, with an average detection rate of 1.2 SLNs per person. The average detection time was 171.0 (68.0–312.0) s, and the average ratio of fluorescence signal to background signal was 5.62 (3.51–7.91). None of the patients had adverse reactions postoperatively. Similarly, Kim et al. [29] also evaluated the feasibility of ICG-guided SLN biopsy in nine patients with oral cancer. ICG was injected around the tumor during the surgery, and the robot firefly system was used to detect the fluorescence signal. The results showed that the positive rate, sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV) of ICG-guided SLN biopsy were 22.2, 100, 91.5, and 100 %, respectively. The findings confirmed that ICG and robotic surgery could accurately identify and locate SLNs.

ICG and methylene blue (MB)

The effectiveness of ICG combined with MB in identifying SLNs in various types of tumors has been validated previously [40], [41], [42]. Although MB was first synthesized by Caro, a German scientist, in 1876 [43], it was not until 1994 that it was first used for SLN detection in Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer [44]. The basement membrane of tissues is often incomplete or discontinuous, and the capillary lymphatic vessels are highly permeable. When MB is injected into the interstitial space, it binds to plasma proteins to form macromolecular compounds, which enter the lymphatic vessels and are then drained into the lymph nodes. These are then ingested by antigen-presenting cells in the lymph nodes and are shown in blue. The blue dye helps surgeons map the path of the lymphatic drainage and ultimately locate the SLNs. Because the visible light emission spectrum of MB is 400–700 nm, in clinical application, surgeons can identify blue-stained lymph nodes with the naked eye [43]. Some scholars have also used MB to detect SLNs in patients with oral cancer, such as Vishnoi et al. [45]. The researchers conducted a prospective experimental study including 94 patients with early oral cancer and found that the sensitivity, specificity, positive PV (PPV), NPV, and accuracy of MB in SLN tracing were 84.6, 100, 100, 93.9, and 95.5 %, respectively. The findings indicated MB’s reliability in SLN detection in early oral cancer. However, compared to using ICG or MB alone, ICG and MB combined has better clinical application as they visually complement each other (fluorescence imaging and blue). The combination of the fluorescence method and the dye method has higher sensitivity and specificity in SLN detection. In Peng et al.’s [30] study, 26 patients with oral/oropharyngeal cancer were injected with 1 mL ICG (5 mg/mL) and 1.5 mL MB (1 mg/mL) around the primary tumor in a four-quadrant mode, sentinel lymph nodes were detected in all 26 patients, the number of sentinel nodes (SNs) per case varied from 1 to 9, with an average of 3.4, consistent with pathological results. The above findings suggested that ICG combined with MB could be a new potential method for SLN detection in patients with oral cancer. In addition, compared with radioisotope detection, ICG combined with MB has better operability with no risk of radiation exposure. However, given the limited studies in this regard, further studies should be conducted to validate these findings.

ICG and 99m Tc nanocolloids

Despite the advantage that MB has no risk of radiation exposure, its effectiveness in SLN detection is not as good as ICG combined with radiocolloid (Tc99m nanocolloid or Tc sulfur99m colloid) [46]. Frontado et al. [31] used ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid and blue dye to detect SLN in 20 patients and found that while 100 % of SLNs were radioactive and fluorescent, however, of the 14 patients injected with blue dye, only 39.2 % of sentinel lymph nodes were detected In head and neck surgery, MB can also contaminate the surgical field, hindering the surgery [47]. Therefore, compared with ICG alone or ICG combined with MB, an alternative most studies use for SLN localization in oral cancer is ICG-99mtc nanocolloid. Murase et al. [32] used ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid double tracer to locate SLNs in 16 patients with oral cancer. They found that ICG detected 35 lymph nodes, of which 28 were identified by the gamma-ray probe, indicating the efficacy of the combined application of fluorescence signal and radiation signal in detecting SLNs. ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid is a new conjugate obtained by combining ICG and 99mTc-nanocolloid with two compounds of different molecular structures. It is composed of radioactive and NIR fluorescent components, which have the advantages of accurate localization of the radionuclide method and real-time fluorescence-guided SLN visualization [48]. When 99mTc-nanocolloid is injected into the body, lymphatic scintigraphy and single photon emission CT (SPECT)/CT can be used to observe the anatomical distribution of the lymphatic system and draining lymph nodes preoperatively [49]. A gamma detector can then be used to detect the radioactive count of lymph nodes during operation, and the location of SLNs can be accurately located according to the radioactive count value. In Meershoek et al.’s [33] study, which included 19 patients with early tongue squamous cell carcinoma, ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid was used as a tracer to determine the edge of the tumor and mark the SLNs. Lymph scintigraphy and SPECT/CT were used for SLN mapping, and the pathological results were verified. The results showed that ICG-99mTc nanocolloids can be used in combination with tumor boundary delineation and SLN detection, which has potential clinical application. Similarly, Berg et al. [34] enrolled 14 patients with oral cancer and injected ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid mixed with tracer for SLN localization. Forty-three SLNs were located and resected under combined guidance. The high radiation signal background around the primary tumor may hinder the localization of SLNs [50]; however, the addition of an ICG fluorescence signal can sufficiently compensate for this defect. Overall, ICG-99mTc-nanocolloid is effective for SLN detection in patients with oral cancer.

Tumor margin determination

The main cause of death in patients with oral cancer is local recurrence. Although various methods have been implemented to reduce it, the local recurrence rate of oral cancer remains at 6–40 %. Local recurrence is closely related to the inadequate determination of resection margins [51], which often relies on preoperative physical examination and imaging findings. However, physical examination is often subjective, and imaging cannot locate the tumor resection margin in real-time. Therefore, some studies have implemented ICG fluorescence imaging technology to determine the extent of tumor resection margins in cancer patients (Table 2) [52, 53].

Determination of tumor margin.

| Injectant | Detection mode | Type of cancer | Concentration | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLZ-100 | Xenogen-IVIS spectrum imaging system | NSG mice | 2 mg/mL | In HNSCC xenografts, BLZ-100 demonstrated an overall signal-to-background ratio (SBR) of 2.51±0.47 SD. The ROC curve demonstrated an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.889; an SBR of 2.5–92 % sensitivity and 74 % specificity. When this analysis was focused on the tumor and non-tumor interface, the AUC increased to 0.971; an SBR of 2.5 ‰–95 % sensitivity and 91 % specificity [54] |

| ICG-LPA | IVS, PDE | Mice | 100 μL/mL | This system can clearly visualize oral squamous cell carcinoma in mice in real-time [55] |

| ICG | HEMS | 2 OSCC patients | 0.5 mg/kg | The fluorescence images exhibit the highest contrast between tumor and normal tissue within 30 min to 1 h of administering ICG. It was determined that the ideal surgical timing is between 30 min and 2 h post-ICG injection [56] |

| NIF imaging instrument | 20 OSCC patients | 0.75 mg/kg | The fluorescence intensities of the tumor, peritumoral, and normal tissues were measured to be 398.863±151.47, 278.52±84.89, and 274.5±100.93 arbitrary units (AUs), respectively (p<0.05). The calculated signal-to-background ratios (SBR) for the tumor compared to the surrounding tissue and normal tissues were found to be approximately 1.45±0.36 and 1.56±0.41 [57] | |

| NIF imaging instrument | 29 OSCC patients | 0.75 mg/kg | All tumors in the ICG group exhibited fluorescence signals, resulting in a significantly lower marginal abnormality rate of only 0.78 % compared to 6.25 % in the non-ICG group (p<0.05) [58] |

-

ICG, indocyanine green; HEMS, hyper eye medical system; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinoma; NIF, near infrared light; BLZ-100, chlorotoxin-indocyanine; IVS, in vivo imaging system; PDE, photodynamic eye; LPA, labeled podoplanin antibody.

ICG determines the tumor extent of oral cancer based on two principles. First is to combine fluorescent substances with tumor antigen-targeting drugs. Because antigen-targeting drugs can specifically act on tumor tissues, the coupled complex can actively enrich tumor tissues to display fluorescent signals. Baik et al. [54] investigated the application of chlorotoxin-ICG conjugate (BLZ-100) in tumor edge recognition in mice. The mouse oral squamous cell carcinoma model was constructed experimentally, and the fluorescence signal of xenografts was observed by subcutaneous injection of chlorotoxin-ICG conjugate. The study found that in oral squamous cell carcinoma xenografts, the total signal background ratio (SBR) of BLZ-100 was 2.51±0.47 SD. When the analysis was focused on tumor and non-tumor sites, the receiver operating characteristic curve showed that the area under the curve was 0.971. The SBR of 2.5 corresponded to 95 % sensitivity and 91 % specificity, suggesting that BLZ-100 can help determine the edge of oral squamous cell carcinoma tumors. Similarly, Ito et al. [55] used the conjugate of anti-flatfoot protein antibody and ICG to identify the tumor boundary range in nude mice loaded with oral squamous cell carcinoma. With the assistance of a photodynamic eye, the experiment was successful, as it not only identified the tumor boundary but also showed it in real-time.

Second is based on enhanced permeability and retention effect. Compared with blood vessels in normal tissues, those in tumor tissues are significantly different in structure and function. Because the rapid growth of tumors relies on the nutrients and oxygen transported through the blood vessels, the vascular gap of tumor tissue is wide, and the structural integrity is poor. In addition, the lack of lymphatic vessels in tumor tissue also leads to the obstruction of lymphatic return. These principles allow the enrichment of macromolecules formed by ICG and plasma proteins in tumor tissue through the vascular gap. Simultaneously, macromolecular substances will not be removed by lymph reflux due to blocked lymphatic reflux [59]. There is a difference in fluorescence signal intensity between normal and tumor tissues when observed with NIR fluorescence imaging equipment; we can determine the size of the tumor tissue and evaluate the surgical margins. Yokoyama et al. [56] used ICG to visualize head and neck tumors in nine patients. Among them, two had oral cancer. The tumor range was successfully identified in all patients with a sensitivity of 100 %, and the maximum contrast between the fluorescence image of tumor tissue and normal tissue could be observed 30 min to 1 h after ICG injection. Pan et al. [57] used ICG-based NIR fluorescence imaging to evaluate surgical margins in 20 patients with oral cancer. At 6–8 h after ICG injection, all patients were able to identify the boundaries of tumor tissue. The mean fluorescence intensity of tumor, peritumoral, and normal tissues were 380.15±141.24, 268.52±79.12, and 262.12±90.16 AU, respectively. The SBR of the tumor to peritumoral and normal tissues were 1.38±0.22 and 1.43±0.27, respectively. This study confirmed that ICG fluorescence imaging could identify the tumor boundary and evaluate the status of surgical margins in patients with oral cancer. Similarly, Wu et al. [58] analyzed the application value of ICG in evaluating surgical safe margin and divided 29 patients with advanced oral cavity into the ICG group (n=13) and the non-ICG group (n=16). The results showed that the abnormal margin rate of ICG group was only 0.78 %, while that of non-ICG group was 6.25 %. ICG-mediated NIR imaging technology can provide a reference for complete resection of tumors.

Repair reconstruction

Perforator positioning

Accurate perforator localization is critical in preoperative flap design. Preoperative detection of the number, diameter, length, and course of perforator vessels can improve the success rate of flap repair, shorten the operation time, and reduce the occurrence of surgical complications. Some of the perforator localization techniques include hand-held DUS, color DUS, laser Doppler flowmetry, CT angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, and infrared imaging, with each having their own strengths and limitations. Owing to its real-time dynamic monitoring ability of perforator vessels and less adverse reactions, ICGA has been increasingly used in perforator vessel localization and flap design in recent years [14]. When ICG is injected into the body, it binds to plasma proteins to form macromolecular compounds, which do not freely diffuse into the surrounding tissues, thus enabling ICG to flow according to the blood vessel. When an NIR light source is irradiated to the observation site, it emits green fluorescence, and the fluorescence signal is imaged using the NIR camera. ICGA helps determine the number of blood vessels, the course of the blood vessels, and blood perfusion, among others. Using this principle, tissue blood perfusion after vascular anastomosis can be monitored and flap necrosis can be detected at an early stage [60]. Azuma et al. [61] located 2–6 perforator vessels in 14 patients using ICGA. Onoda et al. [62] used multidetector-row CT (MDCT), Doppler flowmetry, and ICGA to locate perforating vessels in 50 patients preoperatively. The results showed that MDCT had a 100 % (35/35) PPV and a 70 % (35/50) sensitivity in detecting perforators. Doppler flowmeter had an 80 % (40/50) PPV and a 100 % (50/50) sensitivity. The PPV and sensitivity of ICGA for detecting perforators were 84 % (42/50) and 76 % (38/50), respectively. For patients with a flap thickness of <8 mm and perforating vessels located in the superficial layer, it is difficult to identify the vessels using MDCT. For patients with a flap thickness of >20 mm and perforating vessels located in the deep layer, ICGA is not effective in identifying the vessels. Therefore, in clinical application, the detection method should be selected according to the characteristics of the flaps. At present, using ICGA alone to label perforating vessels is not the best method, but ICGA can achieve good results in assisting in identifying the optimal perforating vessels of pedicled skin flaps. Padula et al. [63] determined the best perforators for anterolateral thigh flap in 10 of 13 patients (77 %) using ICGA. In addition, it shortened the operation time and reduced the incidence of flap necrosis.

Vascular anastomosis

Vascular anastomosis is a key step in free flap repair of oral and maxillofacial defects, and high-quality vascular anastomosis can greatly improve the success rate of repair [64]. End-to-end anastomosis using suture remains the mainstream method of vascular anastomosis; however, it has some limitations, including high technical requirements, time-consuming, and foreign body response [65]. With the development of laser technology, laser-assisted vascular anastomosis (LAVA) gained increased attention due to its advantages, including simple operation, short anastomosis time, less inflammatory reaction, and reduced tissue trauma. In LAVA, when the laser is irradiated on the biological tissue, the heat generated causes the collagen in the tissue to form a triple helix structure reconstruction. The reconstructed triple helix collagen is polymerized together through covalent bonds, thus making the broken ends of blood vessels coagulated together. Although some scholars believed that it is the non-covalent binding of collagen fibers that causes vascular anastomosis, the principle of laser anastomosis remains controversial, and further research is warranted. The use of laser alone for vascular anastomosis can cause great damage to the tissue. Therefore, auxiliary materials have been developed to minimize this effect. When the laser is irradiated on the auxiliary materials, the materials dissolve, polymerize, and coagulate and finally realize the anastomosis of the broken ends of the blood vessels. Initially, auxiliary materials were liquid, and the thickness of the liquid film was difficult to master, making the surgical technique challenging. In recent years, semi-solid materials and new degradable materials have been introduced to assist vascular anastomosis [66]. However, repair and reinforcement materials often need to be combined with dyes. Dyes not only enhance energy absorption at the anastomosis more completely but also reduce the trauma caused by direct laser irradiation to vascular tissue. ICG fluorescent dye has also been used for laser-assisted vascular anastomosis. Schonfeld et al. [67] used a mixture of polycaprolactone (PCL) and ICG for vascular anastomosis. In the experiment, the mixture of PCL and ICG was electrospuned to make a patch, and then the patch was immersed in a 40 % weight bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution. The immersed patch was wrapped at the end of the blood vessel, and the balloon catheter was aligned at the end. The 810-nm diode laser was used to transfer welding energy from the intravascular cavity through the diffuser fiber to conduct vascular anastomosis. First, the in vitro test of the rabbit aorta was performed, followed by the in vivo test of the porcine aorta. The results showed that there was no blood leakage in the anastomosed vessels. The tensile strength of the vessels in vivo and in vitro was 138±52 mN/mm2 and 117±30 mN/mm2, respectively. Mbaidjol et al. [68] also used ICG and PCL-prepared patch to anastomosed blood vessels in the pig model and found that when the diode laser (emission wave 808 nm, power 2–2.2 W) irradiation time was 80–90 s, the immediate patency rate of blood vessels was the highest, and the patency rate was 83 % after 1 week of anastomosis. These results suggested the potential application value of ICG and PCL-composite patch for assisting vascular anastomosis using a laser. Schonfeld et al. [69] also prepared BSA blend microfibers using polyvinyl oxide, PCL, polyethylene, and gelatin as auxiliary proteins. ICG and PCL synthesized the light-absorbing layer and rotated the BSA/polymer layer to prepare layered patches. It was found that with the increase of BSA, the bonding strength of tissue fusion also increased. To validate the effectiveness and safety of ICG-assisted laser vascular anastomosis, future studies in animals and humans should be conducted.

Flap monitoring

Free flap transplantation plays a very important role in the repair of oral and maxillofacial defects. Free flap repair of defects solves postoperative aesthetic problems and reduces stigma in patients with oral cancer to a certain extent. In addition, it helps in the recovery of physiological functions such as swallowing [70]. In recent years, with the rapid development of microsurgery, the application of operating microscopes has increased the success rate of flap transplantation to as high as 95 %. However, postoperative vascular crisis and flap necrosis still occur in 10–30 % of patients [71]. Flap necrosis not only causes secondary injury to patients but also prolongs the length of hospital stay [72]. Therefore, early monitoring of flap blood perfusion is particularly crucial [73]. At present, the clinical methods for flap observation include visual observation, acupuncture experiments, and DUS [74], which are subjective. Owing to its advantageous characteristics, the application of ICG in flap crisis monitoring has proved helpful (Table 3) [75].

Blood perfusion monitoring of flaps.

| Flap | Detection mode | Number of flaps | Concentration | Dose | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT | PDE | 14 | 5 mg/mL | 5 mL | Blood perfusion was detected by ICG fluorescence method during operation. Flap perfusion was confirmed in all patients, and all flaps survived after operation. No adverse reactions occurred [76] |

| SPY | 15 | 12.5 mg | All 15 free flaps were raised with the assistance of laser-assisted angiography and no adverse reactions occurred [77] | ||

| SCIP | PDE | 12 | 5 mg/mL | 1 mL | All flaps were effectively monitored and all survived [78] |

| RF | PDE | 11 | 5 mg/mL | 5 mL | Blood perfusion was detected by ICG fluorescence method during operation. Flap perfusion was confirmed in all patients, and all flaps survived after operation. No adverse reactions occurred [76] |

| SPY | 12 | 7.5 mg | All subjects exhibited satisfactory perfusion of the transplanted limb as demonstrated by fluorescent angiography [79] | ||

| Osteocutaneous flap | PDE | 5 | 5 mg/mL | 5 mL | Blood perfusion was detected by ICG fluorescence method during operation. Flap perfusion was confirmed in all patients, and all flaps survived after operation. No adverse reactions occurred [76] |

| SPY | 2 | 7.5 mg | All subjects exhibited satisfactory perfusion of the transplanted limb as demonstrated by fluorescent angiography [79] | ||

| SPY | 16 | 2.5 mg/mL | 7.5 mg | ICGA can reliably assess tissue perfusion. All flap reconstructions were successful, and the only perfusion-related complication was delayed partial flap loss [80] |

-

HEMS, hyper eye medical system; ICGA, indocyanine green angiography; ALT, anterolateral thigh flap: PDE, photo dynamic eye; SCIP, superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator; RF, radial forearm flap.

Holm et al. [81] used ICGA to evaluate the vascular anastomosis of 50 patients and found that compared with the traditional method of detecting vascular blood flow patency, ICGA was more sensitive and could accurately identify the vessels with anastomotic problems to avoid flap necrosis and secondary surgical exploration. Nagata et al. [76] conducted a study on ICG NIR angiography and acupuncture tests to monitor the blood flow irrigation of intraoral free flaps in 30 patients with oral cancer. The blood perfusion of all the patients was confirmed, and the results showed that ICG could effectively monitor the blood flow in flaps. Sacks et al. [77] used ICGA to intraoperatively identify the best perforator vessels of the anterolateral thigh flap in 15 patients and to monitor blood perfusion. All the patients underwent maxillofacial defect reconstruction, and only one flap failed to be reconstructed due to postoperative venous congestion. Taylor et al. [79] also used ICGA technology to evaluate the intraoperative perfusion of radial forearm free flaps and fibula free flaps, which was successful. No adverse reactions were observed. This proves that ICGA can monitor blood perfusion in real-time, which can help surgeons detect skin flap necrosis early, thereby avoiding harm caused by the second surgery.

PDT

PDT has the advantages of strong specificity, low side effects, and negligible drug resistance [82]. The most important component of PDT is PS. After photoactivation, PS transfers the external light energy to the surrounding oxygen to generate highly active singlet oxygen, which oxidizes with nearby biological macromolecules to produce cytotoxic molecules. This induces apoptosis, necrosis, or autophagy [83]. ICG is an ideal PS because of its low toxicity and ability to accumulate in tumor tissues, as well as be quickly removed. Therefore, ICG can also be used in the PDT of cancer (Table 4). Lim et al. [84] investigated the effectiveness of ICG-based PDT with LED in oral cancer. The LED array with a 0.5 A current and a 50 mW/cm2 radiation intensity irradiated the ICG-injected oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. It was found that compared to 630 and 895 nm, the half inhibitory concentration at 785 nm wavelength was the lowest, at 10 μM, and the semi-inhibitory concentration did not change greatly with time. These findings validated the feasibility of ICG in PDT of patients with oral cancer.

Photodynamics therapy.

| Injectant | Device/System | Type of cancer | Concentration/Dose | Irradiation wavelength | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICG | LED | Cell | From 125 to 0.2 μg/mL | 640, 785, 895 nm | The 700–800 nm range exhibits a prominent peak in ICG [84] |

| HSA-ICG-DDP NPs | IVIS system | Cell mouse | ICG: 2 mg kg | Excitation wavelength: 780 nm | This novel NIR-triggered drug release system displays potential for the improvement of OSCC treatment through its synergistic effects of PTT/PDT and chemotherapy [85] |

| DDP: 0.5 mg kg | Emission wavelength: 820 nm | ||||

| ICG-EVO | NIR laser | Cell, mouse | ICG: 1 mg | 808 nm | The theragnostic liposomes have a significant inhibiting effect on in situ tongue [86] |

| EVO: 1 mg | |||||

| PEG⁃PCL⁃C3⁃ICG | Maestro system | Cell, mouse | 50 mg/kg | 808 nm | With 808 nm laser irradiation at tumor sites, the PEG-PCL-C3-ICG NPs were able to simultaneously produce hyperthermia through C3 and produce reactive oxygen species as well as a fluorescence-guided effect through ICG to kill oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells [87] |

| ICG⁃ART⁃RGD⁃BSA | Maestro system | Cell, mouse | 10 mg/kg | 808 nm | The outcomes of both in vitro and in vivo experiments indicated that the RGD-IBA nanoparticles possess excellent biocompatibility and exhibit remarkable efficacy as combined chemo-phototherapy agents against tumors [88] |

-

ICG, indocyanine green; LED, light emitting diode; EVO, evodiamine; NIR, near infrared light; PEG, polyethylene glycol; Pcl, poly-caprolactone; ART, artemisinin; RGD, arginine-glycine-aspartic acid; BSA, bovine serum albumin; NPs, nanoparticles.

Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery systems (DDS) have emerged as a promising technology in the field of PDT. It addresses many of the limitations associated with traditional PS. Nanomaterials are commonly designed to carry PS and a variety of other therapeutic molecules [89]. To date, a considerable number of PS and nanomaterials have been used in PDT of oral cancer. Wang et al. [85] developed human serum albumin-indocyanine green-cisplatin nanoparticles (HSA-ICG-DDP NPs) DDS. Through in vitro and in vivo experiments, we found that treatment with HSA-ICG-DDP NP induced the generation of reactive oxygen species and cytotoxicity in highly expressed secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine tumors and cancer-associated fibroblasts. In in vivo treatment, HSA-ICG-DDP NP accumulated within the tumor tissue and exhibited a stronger anti-tumor effect compared with ICG, HSA-ICG, and DDP treatment. In addition, Wei et al. [86] integrated evodiamine, a traditional Chinese medicine component, and ICG into the liposome nano platform for the diagnosis and treatment of oral cancer patients. The results showed that the combination had a significant inhibitory effect on tongue tumors through in vivo and in vitro experiments. Petrovic et al. [90] combined ICG with benzoporphyrin derivative for optical imaging-mediated PDT and found the technique feasible. However, compared with the first-generation PS Photofrin and the second-generation PS mTHPC, ICG is not the mainstream PS in PDT. Therefore, further studies exploring the potential application of ICG in the field of PDT are warranted.

Conclusions

With good imaging ability and low toxicity, ICG has great potential clinical applications in SLN biopsy, tumor resection margin determination, head and neck reconstruction, and PDT. ICG combined with MB or Tc nan99mocolloid has higher sensitivity and specificity in SLN detection as compared to using ICG alone. However, owing to ICG’s poor percutaneous fluorescence signal, the addition of CTL may assist in preoperative SLN localization. SLN biopsy in patients with oral cancer can be performed under the guidance of preoperative localization and intraoperative fluorescence signal, using a small incision. With the advent of the fourth generation of the da Vinci robotic system, which is integrated with the NIR imaging system, surgeons can identify the fluorescence signals of the SLNs during surgery. This enables them to perform the biopsy more quickly and accurately, thereby avoiding postoperative complications. In terms of tumor margin determination, ICG is enriched in tumor tissues by active or passive aggregation. The fluorescence emitted by NIR light gives tumor tissues excellent contrast from the surrounding tissues, thus enabling surgeons to identify the tumor margin, remove the tumor tissue completely, and reduce the probability of postoperative tumor recurrence. In head and neck reconstruction, ICG is mainly used in perforator localization, vascular anastomosis, and blood perfusion assessment. ICG can identify the best perforator vessels for the flap and assist in the design of the flap. Furthermore, ICG-mediated laser-assisted vascular anastomosis can reduce the technical difficulty of the surgery and reduce the operation time. ICG can also monitor blood perfusion in real-time, detect anastomotic problems early, and avoid flap necrosis. In PDT, ICG, as a PS, is beneficial in the treatment of oral cancer as well as non-tumor oral diseases such as periodontitis [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97]. Nanoparticles combined with ICG are currently used in the treatment of oral cancer, in addition to their ability to specifically act on tumor cells and accurately kill them, they can carry other therapeutic molecules to improve the effect of PDT. However, ICG is not widely used in the treatment of oral cancer; therefore, studies in this regard are scarce. Therefore, future studies are warranted to support the above findings.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 was modified from Servier Medical Art (http://smart.servier.com/), licensed under a Creative Common Attribution 3.0 Generic License. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the conception and the main idea of the work. ZCH wrote the manuscript. NXR edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Not applicable

References

1. Warnakulasuriya, S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol 2009;45:309–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Laversanne, M, Soerjomataram, I, Jemal, A, et al.. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Oosting, SF, Haddad, RI. Best practice in systemic therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol 2019;9:815. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00815.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Specenier, P, Vermorken, JB. Optimizing treatments for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2018;18:901–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2018.1493925.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Du, E, Mazul, AL, Farquhar, D, Brennan, P, Anantharaman, D, Abedi-Ardekani, B, et al.. Long-term survival in head and neck cancer: impact of site, stage, smoking, and human papillomavirus status. Laryngoscope 2019;129:2506–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27807.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Kuo, WS, Chang, YT, Cho, KC, Chiu, KC, Lien, CH, Yeh, CS, et al.. Gold nanomaterials conjugated with indocyanine green for dual-modality photodynamic and photothermal therapy. Biomaterials 2012;33:3270–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.035.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Dip, FD, Roy, M, Perrins, S, Ganga, RR, Lo Menzo, E, Szomstein, S, et al.. Technical description and feasibility of laparoscopic adrenal contouring using fluorescence imaging. Surg Endosc 2015;29:569–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3699-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Suh, YJ, Choi, JY, Chai, YJ, Kwon, H, Woo, JW, Kim, SJ, et al.. Indocyanine green as a near-infrared fluorescent agent for identifying parathyroid glands during thyroid surgery in dogs. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2811–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3971-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Porcu, EP, Salis, A, Gavini, E, Rassu, G, Maestri, M, Giunchedi, P. Indocyanine green delivery systems for tumour detection and treatments. Biotechnol Adv 2016;34:768–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.04.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Chiu, CH, Chao, YK, Liu, YH, Wen, CT, Chen, WH, Wu, CY, et al.. Clinical use of near-infrared fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green in thoracic surgery: a literature review. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S744–S8. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2016.09.70.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Nomori, H, Cong, Y, Sugimura, H. Utility and pitfalls of sentinel node identification using indocyanine green during segmentectomy for cT1N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer. Surg Today 2016;46:908–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-015-1248-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Kawakita, N, Takizawa, H, Kondo, K, Sakiyama, S, Tangoku, A. Indocyanine green fluorescence navigation thoracoscopic metastasectomy for pulmonary metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;22:367–9. https://doi.org/10.5761/atcs.cr.15-00367.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Whitlock, RS, Patel, KR, Yang, TY, Nguyen, HN, Masand, P, Vasudevan, SA. Pathologic correlation with near infrared-indocyanine green guided surgery for pediatric liver cancer. J Pediatr Surg 2022;57:700–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.04.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Degett, TH, Andersen, HS, Gogenur, I. Indocyanine green fluorescence angiography for intraoperative assessment of gastrointestinal anastomotic perfusion: a systematic review of clinical trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2016;401:767–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-016-1400-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Ludolph, I, Horch, RE, Arkudas, A, Schmitz, M. Enhancing safety in reconstructive microsurgery using intraoperative indocyanine green angiography. Front Surg 2019;6:39. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2019.00039.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Faria, EF. Editorial comment: best practices in near-infrared fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green (NIRF/ICG)-guided robotic urologic surgery: a systematic review-based expert consensus. Int Braz J Urol 2020;46:281–2. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.02.09.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Yuan, Z, Lin, CC, He, Y, Tao, BL, Chen, MW, Zhang, JX, et al.. Near-infrared light-triggered nitric-oxide-enhanced photodynamic therapy and low-temperature photothermal therapy for biofilm elimination. Acs Nano 2020;14:3546–62. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b09871.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Hanai, N, Asakage, T, Kiyota, N, Homma, A, Hayashi, R. Controversies in relation to neck management in N0 early oral tongue cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2019;49:297–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyy196.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Hasegawa, Y, Tsukahara, K, Yoshimoto, S, Miura, K, Yokoyama, J, Hirano, S, et al.. Neck dissections based on sentinel lymph node navigation versus elective neck dissections in early oral cancers: a randomized, multicenter, and noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2025+. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.20.03637.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Hayashi, A, Hayashi, N, Yoshimatsu, H, Yamamoto, T. Effective and efficient lymphaticovenular anastomosis using preoperative ultrasound detection technique of lymphatic vessels in lower extremity lymphedema. J Surg Oncol 2018;117:290–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.24812.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Chen, WF, Zhao, HD, Yamamoto, T, Hara, H, Ding, J. Indocyanine green lymphographic evidence of surgical efficacy following microsurgical and supermicrosurgical lymphedema reconstructions. J Reconstr Microsurg 2016;32:688–98. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1586254.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Unno, N, Inuzuka, K, Suzuki, M, Yamamoto, N, Sagara, D, Nishiyama, M, et al.. Preliminary experience with a novel fluorescence lymphography using indocyanine green in patients with secondary lymphedema. J Vasc Surg 2007;45:1016–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Yamamoto, T, Iida, T, Matsuda, N, Kikuchi, K, Yoshimatsu, H, Mihara, M, et al.. Indocyanine green (ICG)-enhanced lymphography for evaluation of facial lymphoedema. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 2011;64:1541–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2011.05.025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Al-Dam, A, Precht, C, Barbe, A, Kohlmeier, C, Hanken, H, Wikner, J, et al.. Sensitivity and specificity of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with oral squamous cell carcinomas using indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. J Cranio-Maxillo-Fac Surg 2018;46:1379–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2018.05.039.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Chen, YF, Xiao, Q, Zou, WN, Xia, CW, Yin, HL, Pu, YM, et al.. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in oral cavity cancer using indocyanine green: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics 2021;76:e2573.10.6061/clinics/2021/e2573Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Honda, K, Ishiyama, K, Suzuki, S, Kawasaki, Y, Saito, H, Horii, A. Sentinel lymph node biopsy using preoperative computed tomographic lymphography and intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in patients with localized tongue cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;145:735–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1243.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Sugiyama, S, Iwai, T, Izumi, T, Ishiguro, K, Baba, J, Oguri, S, et al.. CT lymphography for sentinel lymph node mapping of clinically N0 early oral cancer. Cancer Imag 2019;19:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-019-0258-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Chow, VLY, Ng, JCW, Chan, JYW, Gao, W, Wong, TS. Robot-assisted real-time sentinel lymph node mapping in oral cavity cancer: preliminary experience. J Robot Surg 2021;15:349–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-020-01112-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Kim, JH, Byeon, HK, Kim, D, Kim, SH, Choi, EC, Koh, YW. ICG-guided sentinel lymph node sampling during robotic retroauricular neck dissection in cN0 oral cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;162:410–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599819900264.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Peng, H, Wang, SJ, Niu, X, Yang, X, Chi, C, Zhang, G. Sentinel node biopsy using indocyanine green in oral/oropharyngeal cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:278. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0691-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Frontado, LM, Brouwer, OR, van den Berg, NS, Mathéron, HM, Vidal-Sicart, S, van Leeuwen, FWB, et al.. Added value of the hybrid tracer indocyanine green-99mTc-nanocolloid for sentinel node biopsy in a series of patients with different lymphatic drainage patterns. Rev Española Med Nucl Imagen Mol 2013;32:227–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remnie.2013.05.015.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Murase, R, Tanaka, H, Hamakawa, T, Goda, H, Tano, T, Ishikawa, A, et al.. Double sentinel lymph node mapping with indocyanine green and 99m-technetium–tin colloid in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;44:1212–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2015.05.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Meershoek, P, van den Berg, NS, Brouwer, OR, Teertstra, HJ, Lange, CAH, Valdés-Olmos, RA, et al.. Three-dimensional tumor margin demarcation using the hybrid tracer indocyanine green-99mTc-nanocolloid: a proof-of-concept study in tongue cancer patients scheduled for sentinel node biopsy. J Nucl Med 2019;60:764–9. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.118.220202.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. van den Berg, NS, Brouwer, OR, Klop, WMC, Karakullukcu, B, Zuur, CL, Tan, IB, et al.. Concomitant radio- and fluorescence-guided sentinel lymph node biopsy in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity using ICG-(99m)Tc-nanocolloid. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag 2012;39:1128–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-012-2129-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Christensen, A, Juhl, K, Charabi, B, Mortensen, J, Kiss, K, Kjaer, A, et al.. Feasibility of real-time near-infrared fluorescence tracer imaging in sentinel node biopsy for oral cavity cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:565–72. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4883-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Borbon-Arce, M, Brouwer, OR, van den Berg, NS, Matheron, H, Klop, WMC, Balm, AJM, et al.. An innovative multimodality approach for sentinel node mapping and biopsy in head and neck malignancies. Rev Española Med Nucl Imagen Mol 2014;33:274–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remnie.2014.06.015.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Wan, J, Oblak, ML, Ram, A, Singh, A, Nykamp, S. Determining agreement between preoperative computed tomography lymphography and indocyanine green near infrared fluorescence intraoperative imaging for sentinel lymph node mapping in dogs with oral tumours. Vet Comp Oncol 2021;19:295–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/vco.12675.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Muhanna, N, Chan, HHL, Douglas, CM, Daly, MJ, Jaidka, A, Eu, D, et al.. Sentinel lymph node mapping using ICG fluorescence and cone beam CT – a feasibility study in a rabbit model of oral cancer. BMC Med Imag 2020;20:106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-020-00507-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Spinoglio, G, Bellora, P, Monni, M. Robotic technology for colorectal surgery: procedures, current applications, and future innovative challenges. Chirurg 2017;88(Suppl 1):29–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-016-0208-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Stummer, W, Pichlmeier, U, Meinel, T, Wiestler, OD, Zanella, F, Reulen, H-J, et al.. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:392–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(06)70665-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Baeten, IGT, Hoogendam, JP, Jeremiasse, B, Braat, AJAT, Veldhuis, WB, Jonges, GN, et al.. Indocyanine green versus technetium-99m with blue dye for sentinel lymph node detection in early-stage cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2022;5:e1401. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnr2.1401.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Guo, JJ, Yang, HP, Wang, S, Cao, YM, Liu, M, Xie, F, et al.. Comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy guided by indocyanine green, blue dye, and their combination in breast cancer patients: a prospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol 2017;15:196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1264-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Cwalinski, T, Polom, W, Marano, L, Roviello, G, D’Angelo, A, Cwalina, N, et al.. Methylene blue-current knowledge, fluorescent properties, and its future use. J Clin Med 2020;9:3538. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113538.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Giuliano, AE, Kirgan, DM, Guenther, JM, Morton, DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg 1994;220:391–8; discussion 8-401. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199409000-00015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Vishnoi, JR, Kumar, V, Gupta, S, Chaturvedi, A, Misra, S, Akhtar, N, et al.. Outcome of sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity with methylene blue dye alone: a prospective validation study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2019;57:755–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.06.025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Dell’Oglio, P, de Vries, HM, Mazzone, E, KleinJan, GH, Donswijk, ML, van der Poel, HG, et al.. Hybrid indocyanine green-99mTc-nanocolloid for single-photon emission computed tomography and combined radio- and fluorescence-guided sentinel node biopsy in penile cancer: results of 740 inguinal basins assessed at a single institution. Eur Urol 2020;78:865–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Broglie, MA, Stoeckli, SJ. Relevance of sentinel node procedures in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;55:509–20.Suche in Google Scholar

48. KleinJan, GH, Hellingman, D, van den Berg, NS, van Oosterom, MN, Hendricksen, K, Horenblas, S, et al.. Hybrid surgical guidance: does hardware integration of γ- and fluorescence imaging modalities make sense? J Nucl Med 2017;58:646–50. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.116.177154.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Tokin, CA, Cope, FO, Metz, WL, Blue, MS, Potter, BM, Abbruzzese, BC, et al.. The efficacy of Tilmanocept in sentinel lymph mode mapping and identification in breast cancer patients: a comparative review and meta-analysis of the ⁹⁹mTc-labeled nanocolloid human serum albumin standard of care. Clin Exp Metastasis 2012;29:681–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-012-9497-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50. de Bree, R, Leemans, CR. Recent advances in surgery for head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2010;22:186–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/cco.0b013e3283380009.Suche in Google Scholar

51. Tasche, KK, Buchakjian, MR, Pagedar, NA, Sperry, SM. Definition of “close margin” in oral cancer surgery and association of margin distance with local recurrence rate. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;143:1166–72. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0548.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

52. Newton, AD, Predina, JD, Shin, MH, Frenzel-Sulyok, LG, Vollmer, CM, Drebin, JA, et al.. Intraoperative near-infrared imaging can identify neoplasms and aid in real-time margin assessment during pancreatic resection. Ann Surg 2019;270:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000003201.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Wang, Y, Jiao, W, Yin, Z, Zhao, W, Zhao, K, Zhou, Y, et al.. Application of near-infrared fluorescence imaging in the accurate assessment of surgical margins during breast-conserving surgery. World J Surg Oncol 2022;20:357. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-022-02827-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Baik, F, Hansen, S, Knoblaugh, S, Sahetya, D, Mitchell, R, Xu, C, et al.. Fluorescence identification of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and high-risk oral dysplasia with BLZ-100, a chlorotoxin-indocyanine green conjugate. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016:142.10.1001/jamaoto.2015.3617Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Ito, A, Ohta, M, Kato, Y, Inada, S, Kato, T, Nakata, S, et al.. A real-time near-infrared fluorescence imaging method for the detection of oral cancers in mice using an indocyanine green-labeled Podoplanin antibody. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018;17:1533033818767936. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533033818767936.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Yokoyama, J, Fujimaki, M, Ohba, S, Anzai, T, Yoshii, R, Ito, S, et al.. A feasibility study of NIR fluorescent image-guided surgery in head and neck cancer based on the assessment of optimum surgical time as revealed through dynamic imaging. Onco Targets Ther 2013;6:325–30. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s42006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Pan, JR, Deng, H, Hu, SQ, Xia, CW, Chen, YF, Wang, JQ, et al.. Real-time surveillance of surgical margins via ICG-based near-infrared fluorescence imaging in patients with OSCC. World J Surg Oncol 2020;18:96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-01874-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58. Wu, ZH, Dong, YC, Wang, YX, Hu, QA, Cai, HM, Sun, GW. Clinical application of indocyanine green fluorescence navigation technology to determine the safe margin of advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. Gland Surg 2022;11:352–7. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs-22-33.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

59. Maeda, H. Toward a full understanding of the EPR effect in primary and metastatic tumors as well as issues related to its heterogeneity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015;91:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2015.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Pruimboom, T, Schols, RM, Van Kuijk, SMJ, Van der Hulst, R, Qiu, SS. Indocyanine green angiography for preventing postoperative mastectomy skin flap necrosis in immediate breast reconstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;4:CD013280. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd013280.pub2.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Azuma, R, Morimoto, Y, Masumoto, K, Nambu, M, Takikawa, M, Yanagibayashi, S, et al.. Detection of skin perforators by indocyanine green fluorescence nearly infrared angiography. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122:1062–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0b013e3181858bd2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Onoda, S, Azumi, S, Hasegawa, K, Kimata, Y. Preoperative identification of perforator vessels by combining MDCT, Doppler flowmetry, and ICG fluorescent angiography. Microsurgery 2013;33:265–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.22079.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

63. La Padula, S, Hersant, B, Meningaud, JP. Intraoperative use of indocyanine green angiography for selecting the more reliable perforator of the anterolateral thigh flap: a comparison study. Microsurgery 2018;38:738–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.30326.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

64. Mudigonda, SK, Murugan, S, Velavan, K, Thulasiraman, S, Raja, V. Non-suturing microvascular anastomosis in maxillofacial reconstruction – a comparative study. J Cranio-Maxillo-Fac Surg 2020;48:599–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2020.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Bass, LS, Treat, MR. Laser tissue welding: a comprehensive review of current and future clinical applications. Lasers Surg Med 1995;17:315–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.1900170402.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Pabittei, DR, Heger, M, van Tuijl, S, Simonet, M, de Boon, W, van der Wal, AC, et al.. Ex vivo proof-of-concept of end-to-end scaffold-enhanced laser-assisted vascular anastomosis of porcine arteries. J Vasc Surg 2015;62:200–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2014.01.064.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Schönfeld, A, Constantinescu, M, Peters, K, Frenz, M. Electrospinning of highly concentrated albumin patches by using auxiliary polymers for laser-assisted vascular anastomosis. Biomed Mater 2018;13:055001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-605x/aac332.Suche in Google Scholar

68. Mbaidjol, Z, Kiermeir, D, Schonfeld, A, Arnoldi, J, Frenz, M, Constantinescu, MA. Endoluminal laser-assisted vascular anastomosis-an in vivo study in a pig model. Lasers Med Sci 2017;32:1343–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-017-2250-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

69. Schönfeld, A, Kabra, ZM, Constantinescu, M, Bosshardt, D, Stoffel, MH, Peters, K, et al.. Binding of indocyanine green in polycaprolactone fibers using blend electrospinning for in vivo laser-assisted vascular anastomosis. Lasers Surg Med 2017;49:928–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.22701.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Kim, JT, Kim, SW. Perforator flap versus conventional flap. J Kor Med Sci 2015;30:514–22. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.5.514.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Kääriäinen, M, Halme, E, Laranne, J. Modern postoperative monitoring of free flaps. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;26:248–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/moo.0000000000000467.Suche in Google Scholar

72. Mucke, T, Schmidt, LH, Fichter, AM, Wolff, KD, Ritschl, LM. Influence of venous stasis on survival of epigastric flaps in rats. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018;56:310–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2018.01.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Shen, AY, Lonie, S, Lim, K, Farthing, H, Hunter-Smith, DJ, Rozen, WM. Free flap monitoring, salvage, and failure timing: a systematic review. J Reconstr Microsurg 2021;37:300–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1722182.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Disa, JJ, Cordeiro, PG, Hidalgo, DA. Efficacy of conventional monitoring techniques in free tissue transfer: an 11-year experience in 750 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;104:97–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199907000-00014.Suche in Google Scholar

75. Mucke, T, Fichter, AM, Schmidt, LH, Mitchell, DA, Wolff, KD, Ritschl, LM. Indocyanine green videoangiography-assisted prediction of flap necrosis in the rat epigastric flap using the flow® 800 tool. Microsurgery 2017;37:235–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.30072.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Nagata, T, Masumoto, K, Uchiyama, Y, Watanabe, Y, Azuma, R, Morimoto, Y, et al.. Improved technique for evaluating oral free flaps by pinprick testing assisted by indocyanine green near-infrared fluorescence angiography. J Cranio-Maxillo-Fac Surg 2014;42:1112–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2014.01.040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

77. Sacks, JM, Nguyen, AT, Broyles, JM, Yu, P, Valerio, IL, Baumann, DP. Near-infrared laser-assisted indocyanine green imaging for optimizing the design of the anterolateral thigh flap. Eplasty 2012;12:e30.Suche in Google Scholar

78. Iida, T, Mihara, M, Yoshimatsu, H, Narushima, M, Koshima, I. Versatility of the superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap in head and neck reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 2014;72:332–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/sap.0b013e318260a3ad.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

79. Taylor, SR, Jorgensen, JB. Use of fluorescent angiography to assess donor site perfusion prior to free tissue transfer. Laryngoscope 2015;125:E192–E7. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25190.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

80. Valerio, I, Green, JM, Sacks, JM, Thomas, S, Sabino, J, Acarturk, TO. Vascularized osseous flaps and assessing their bipartate perfusion pattern via intraoperative fluorescence angiography. J Reconstr Microsurgery 2015;31:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1383821.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Holm, C, Mayr, M, Hofter, E, Dornseifer, U, Ninkovic, M. Assessment of the patency of microvascular anastomoses using microscope-integrated near-infrared angiography: a preliminary study. Microsurgery 2009;29:509–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.20645.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Fan, HY, Zhu, ZL, Zhang, WL, Yin, YJ, Tang, YL, Liang, XH, et al.. Light stimulus responsive nanomedicine in the treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Med Chem 2020;199:112394.10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112394Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Chilakamarthi, U, Giribabu, L. Photodynamic therapy: past, present and future. Chem Rec 2017;17:775–802. https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.201600121.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

84. Lim, H-J, Oh, C-H. Indocyanine green-based photodynamic therapy with 785 nm light emitting diode for oral squamous cancer cells. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2011;8:337–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2011.06.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

85. Wang, YX, Xie, DY, Pan, JR, Xia, CW, Fan, L, Pu, YM, et al.. A near infrared light-triggered human serum albumin drug delivery system with coordination bonding of indocyanine green and cisplatin for targeting photochemistry therapy against oral squamous cell cancer. Biomater Sci 2019;7:5270–82. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9bm01192g.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

86. Wei, Z, Zou, H, Liu, G, Song, C, Tang, C, Chen, S, et al.. Peroxidase-mimicking evodiamine/indocyanine green nanoliposomes for multimodal imaging-guided theranostics for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Bioact Mater 2021;6:2144–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.12.016.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

87. Ren, S, Cheng, X, Chen, M, Liu, C, Zhao, P, Huang, W, et al.. Hypotoxic and rapidly metabolic PEG-PCL-C3-ICG nanoparticles for fluorescence-guided photothermal/photodynamic therapy against OSCC. ACS Appl Mater Inter 2017;9:31509–18. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b09522.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

88. Ma, Y, Liu, X, Ma, Q, Liu, Y. Near-infrared nanoparticles based on indocyanine green-conjugated albumin: a versatile platform for imaging-guided synergistic tumor chemo-phototherapy with temperature-responsive drug release. Onco Targets Ther 2018;11:8517–28. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.s183887.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

89. Fan, HY, Yu, XH, Wang, K, Yin, YJ, Tang, YJ, Tang, YL, et al.. Graphene quantum dots (GQDs)-based nanomaterials for improving photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Eur J Med Chem 2019:182.10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111620Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

90. Petrovic, LZ, Xavierselvan, M, Kuriakose, M, Kennedy, MD, Nguyen, CD, Batt, JJ, et al.. Mutual impact of clinically translatable near-infrared dyes on photoacoustic image contrast and in vitro photodynamic therapy efficacy. J Biomed Opt 2020;25:1. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.25.6.063808.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

91. Dalvi, SA, Hanna, R, Gattani, DR. Utilisation of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as an adjunctive tool for open flap debridement in the management of chronic periodontitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2019;25:440–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.01.023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

92. Niazi, FH, Noushad, M, Tanvir, SB, Ali, S, Al-Khalifa, KS, Qamar, Z, et al.. Antimicrobial efficacy of indocyanine green-mediated photodynamic therapy compared with Salvadora persica gel application in the treatment of moderate and deep pockets in periodontitis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2020;29:101665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101665.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

93. Nikinmaa, S, Alapulli, H, Auvinen, P, Vaara, M, Rantala, J, Kankuri, E, et al.. Dual-light photodynamic therapy administered daily provides a sustained antibacterial effect on biofilm and prevents Streptococcus mutans adaptation. Plos One 2020;15:e0232775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232775.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

94. Peeridogaheh, H, Pourhajibagher, M, Barikani, HR, Bahador, A. The impact of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans biofilm-derived effectors following antimicrobial photodynamic therapy on cytokine production in human gingival fibroblasts. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2019;27:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.05.025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

95. Pourhajibagher, M, Beytollahi, L, Ghorbanzadeh, R, Bahador, A. Analysis of glucosyltransferase gene expression of clinical isolates of Streptococcus mutans obtained from dental plaques in response to sub-lethal doses of photoactivated disinfection. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2018;24:75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.09.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

96. Afroozi, B, Zomorodian, K, Lavaee, F, Shahrabadi, ZZ, Mardani, M. Comparison of the efficacy of indocyanine green-mediated photodynamic therapy and nystatin therapy in treatment of denture stomatitis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2019;27:193–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.06.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

97. Alinca, SB, Saglam, E, Kandas, NO, Okcu, O, Yilmaz, N, Goncu, B, et al.. Comparison of the efficacy of low-level laser therapy and photodynamic therapy on oral mucositis in rats. Lasers Med Sci 2019;34:1483–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-019-02757-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Mitochondrial thermogenesis in cancer cells

- Application of indocyanine green in the management of oral cancer: a literature review

- Long non-coding RNA, FOXP4-AS1, acts as a novel biomarker of cancers

- The role of synthetic peptides derived from bovine lactoferricin against breast cancer cell lines: a mini-review

- Single cell RNA sequencing – a valuable tool for cancer immunotherapy: a mini review

- Research Articles

- Global patterns and temporal trends in ovarian cancer morbidity, mortality, and burden from 1990 to 2019

- The association between NRF2 transcriptional gene dysregulation and IDH mutation in Grade 4 astrocytoma

- More than just a KRAS inhibitor: DCAI abrogates the self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells in vitro

- DUSP1 promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion by upregulating nephronectin expression

- IMMT promotes hepatocellular carcinoma formation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

- MiR-100-5p transfected MSCs-derived exosomes can suppress NSCLC progression via PI3K-AKT-mTOR

- Inhibitory function of CDK12i combined with WEE1i on castration-resistant prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic potential of m7G-associated lncRNA signature in predicting bladder cancer response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy

- Case Reports

- A rare FBXO25–SEPT14 fusion in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia treatment to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a case report

- Stage I duodenal adenocarcinoma cured by a short treatment cycle of pembrolizumab: a case report

- Rapid Communication

- ROMO1 – a potential immunohistochemical prognostic marker for cancer development

- Article Commentary

- A commentary: Role of MTA1: a novel modulator reprogramming mitochondrial glucose metabolism

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Mitochondrial thermogenesis in cancer cells

- Application of indocyanine green in the management of oral cancer: a literature review

- Long non-coding RNA, FOXP4-AS1, acts as a novel biomarker of cancers

- The role of synthetic peptides derived from bovine lactoferricin against breast cancer cell lines: a mini-review

- Single cell RNA sequencing – a valuable tool for cancer immunotherapy: a mini review

- Research Articles

- Global patterns and temporal trends in ovarian cancer morbidity, mortality, and burden from 1990 to 2019

- The association between NRF2 transcriptional gene dysregulation and IDH mutation in Grade 4 astrocytoma

- More than just a KRAS inhibitor: DCAI abrogates the self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells in vitro

- DUSP1 promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion by upregulating nephronectin expression

- IMMT promotes hepatocellular carcinoma formation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

- MiR-100-5p transfected MSCs-derived exosomes can suppress NSCLC progression via PI3K-AKT-mTOR

- Inhibitory function of CDK12i combined with WEE1i on castration-resistant prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic potential of m7G-associated lncRNA signature in predicting bladder cancer response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy

- Case Reports