Abstract

Objectives

Exosomes are highly implicated in lung cancer and are capable of transferring therapeutic miRNAs.

Methods

Database analysis was performed to screen the probable miRNA involved in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The levels of miR-100-5p in NSCLC cells and tissues were evaluated. The mechanism by which MSC-derived exosomes mediate the delivery of miR-100-5p in NSCLC cells was explored in vitro. The therapeutic effect and safety of miR-100-5p-containing MSC-derived exosomes in nude mice were assessed.

Results

MiR-100-5p was significantly downregulated in NSCLC. Transfer of miR-100-5p via MSCs-derived exosomes inhibited NSCLC progression by the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. No obvious toxic effects were observed in mice.

Conclusions

MSCs-derived exosome-transfected miR-100-5p inhibits NSCLC progression via PI3K-AKT-mTOR, providing a promising diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target of NSCLC.

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most frequent subtype of lung cancer and has a high mortality. Various treatment strategies have emerged, but all are limited by unsatisfactory efficacy [1, 2]. Novel therapies are urgently needed.

Non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), regulate the expression of cancer-related genes [3]. miRNAs regulate mRNAs in various biological processes of cancers [4]. Research has been performed to explore the role of miR-100-5p in cancer development. miR-100-5p must be transported by exosomes to act on recipient cells [5].

Exosomes, with a diameter of 30–150 nm, are vesicles released by cells into the extracellular milieu [6]. Exosomes harbor proteins, lipids, DNAs, miRNAs or mRNAs that can regulate intercellular communications or those between the cells and surroundings [6]. The involvement of exosomes in the development of tumors has been confirmed [2, 7]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), a group of exosome-secreting cells, have slipped into the focus of preclinical research about cancers [8]. However, how MSCs-derived exosomes transfer miR-100-5p onto NSCLC cells to exert a therapeutic effect remains unclear.

In the present research, miR-100-5p was transfected into exosomes produced from MSCs, and its impact on NSCLC was assessed both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we estimated the feasibility and safety of transfecting miR-100-5p into exosomes generated from MSCs. This research may provide a new treatment target for NSCLC.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) created the miR-100-5p sequence. The normal human bronchial epithelial (HLF-α) cell line, NSCLC cell lines H1650, A549, H1975, and HCC827, and RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 % Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) were purchased from American type culture collection (ATCC) and kept at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 with 10 % FBS. As instructed, the exosomes were isolated and transfected with miR-100-5p using ExoFectin sRNA-into-Exosome Kit (101Bio, California, USA). In brief, miR-100-5p was mixed with TransExo buffer and TransExo reagent at 25 °C for 5 min, and then exosomes were added and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Finally, untransfected miR-100-5p was removed with RNase. A549 cells were cultured with MSCs, MSCs-derived exosomes (M-exo), and MSCs-derived exosomes transfected with miR-100-5p (M-exo-miR), respectively.

Exosome isolation and identification

Mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cords (hUC-MSCs) were obtained from ATCC and grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) medium with 10 % exosome-free FBS (Gibco, New York, USA). After 2 days of culture, the exosomes were isolated from the MSCs supernatant using the method reported by Song et al. [8]. After the removal of cellular debris, the MSCs supernatant was supplemented with exosome isolation reagent for 12 h at 4 °C, and suspended in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) (pH 7.4, Gibco, New York, USA) again. Then the exosomal surface protein markers were evaluated by Western blotting. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEM-1230, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe exosomes. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) apparatus NanoSight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK), with NTA software version 3.2 (Malvern Instruments), was employed to characterize the size and concentration of the exosomes. The experiments were repeated three times and the results of which are presented as means.

Exosome uptake in the cells

The nuclei of the exosomes were stained with 4′,6-diamidine-2-phenylindole (DAPI) by incubating them with Red Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit (PKH26) (Umibio, Shanghai, China) at room temperature for 5 min. Finally, exosome uptake in the cells was observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from exosomes, cells and tissues by TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China). Qubit 3.0 (ThermoFisher, New York, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis were used to quantify and qualify the RNAs. The primers for miR-100-5p, protein kinase B (AKT/PKB), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) were synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, China). The SYBR qPCR One-step kit was prepared by Vazyme (Q221-01 and MQ101-01, Nanjing, China). After the experiments, the mixture was subjected to the ABI 7900 system (ThermoFisher, New York, USA). Then the PCR conditions were set according to the one-step kit. The relative expression level was calculated utilizing the 2−ΔΔCt approach, with β-actin as the internal gene.

Western blot analysis

The tissue samples were lysed with Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) buffer (Roche, Shanghai, China), and protein concentration was assessed using a Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assay (Roche, Shanghai, China). Utilizing the normal sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) method [9], the gels were transferred, blocked and cultured with primary antibodies against exosome biomarkers of tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101), CD63; cell proliferation biomarkers of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and Ki67; cell apoptosis biomarkers of B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2)-associated X (Bax), Bal-2, cleaved cysteine aspastic acid-3 (cleaved-caspase-3), cleaved-caspase-9, migration and invasion biomarkers of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2), MMP9; epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) biomarkers of N-cadherin, E-cadherin, Vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and β-actin (all from Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

After washing, the membranes were treated with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L secondary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and the bands were then visualized using a Tanon 6600 Luminescence imaging workstation (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

Immunofluorescence analysis

Having been fixed with 4 % formaldehyde, the cells were blocked in 5 % Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), followed by a 48 h incubation with fluorescent secondary antibodies against E-cadherin, α-SMA, N-cadherin, and Vimentin (all from Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Then the cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope after DAPI staining (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For each group, five fields were picked at random and photographed.

Cell proliferation assay

To measure cell proliferation, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) assays were employed. At 37 °C for 2 h, the exosomes were treated with the CCK-8 reagent. Using a microplate reader (Bioteke, Beijing, China), the absorbance (OD450 nm) was recorded after 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. Cells were grown with EdU for 2 h, washed twice in PBS, permeabilized with 0.5 % Triton X-100, and then rinsed again in PBS for the EdU experiment using the EdU Cell Proliferation Kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China). The fluorescence intensity was observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell apoptosis assay

Following a previously reported method [10], the cells were resuspended and stained with propidium iodide (PI). PI reagents (Abace Biotechnology, Beijing, China) were added to the cell suspension and cultured in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Flow cytometry was carried out to calculate the apoptosis rate.

Migration and invasion assays

Wound-healing and Transwell assays were used to examine cell migration and invasion. Overnight, the cells were placed on 6-well plates, and the scratches were produced using a sterile plastic pipette tip. At 48 h later, the wound width was measured. Eight-micrometer pore membranes (Corning, New York, USA) covered with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Beijing, China) and a 24-well Transwell chamber were used to evaluate cell invasion. The wells in 100 mL of serum-free DMEM were roughly placed into the top chamber (1.0 × 105 cells/well) and allowed to grow for 6 h at 37 °C; the bottom chamber was seeded with 500 mL of media containing 10 % FBS. After that, the chamber underwent washing, glutaraldehyde (2.5 %, pH7.4) fixing (in detail, the sample is immersed in the glutaraldehyde for about 30 min, mix the sample in glutaraldehyde, then remove the sample from glutaraldehyde and wash it with phosphate buffer), and crystal violet staining (0.1 % concentration, v/v). Subsequently, a 400× microscope was adopted to count the invaded cells in five randomly selected fields. The same procedures were performed in cell migration analysis, except for the addition of DMEM and culture.

In vivo experiments

Shanghai Sipul-Bikai Experimental Animal Co. LTD. provided the BALB/c nude mice aged 6–8 weeks and weighing an average of 18 g. The mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment with 12 h light/dark cycles. Nine mice were randomly divided into three groups (3 mice per group). The mice were subcutaneously injected with 0.2 mL of cell suspension that contained 2 × 106 A549 cells every week until subcutaneous tumors formed. Follow-up experiments were conducted when the tumor volume approached 1 cm3. Exosomes or an equal amount of saline were injected (2 mg/kg) through the tail vein of mice every three days. After four weeks, the nude mice were sacrificed via anesthesia overdose (90 mL/kg) after intraperitoneal injection of 3 % pentobarbital sodium. Tumor weight and volume were measured every week as previously described [11]. H&E, Ki67, and TUNEL staining were performed.

In the safety analysis, BALB/c nude mice (six weeks old to eight weeks old) were assigned to three groups (n=3 per group), all treated with the same doses of exomes with or without miR-100-5p, or the same volume of saline. After four weeks of maintenance, the nude mice were processed with an intraperitoneal injection of 3 % pentobarbital sodium and sacrificed by anesthesia overdose (90 mL/kg). Serological markers were measured, and the toxicity in organ tissues was evaluated through H&E staining.

miRNA in situ hybridization (ISH) analysis

ISH was performed in human cancer and non-cancer tissues of 15 NSCLC patients to assess miR-100-5p expression using a method previously reported by Chen et al. [12]. MiR-100-5p was detected by the miRCURY locked nucleic acid (LNA) detection probe. Nuclear fast red and 4-nitroblue-tetrazolium were incubated with the tissue slides (Roche Applied Science, Indiana, USA). The outcomes were observed at a 200× magnification.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and graphics were created by GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, California, USA). ANONA and the Student’s t-test were applied to compare the data. Information is presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). The significant difference was indicated by a p<0.05.

Results

MiR-100-5p expression was negatively associated with NSCLC prognosis

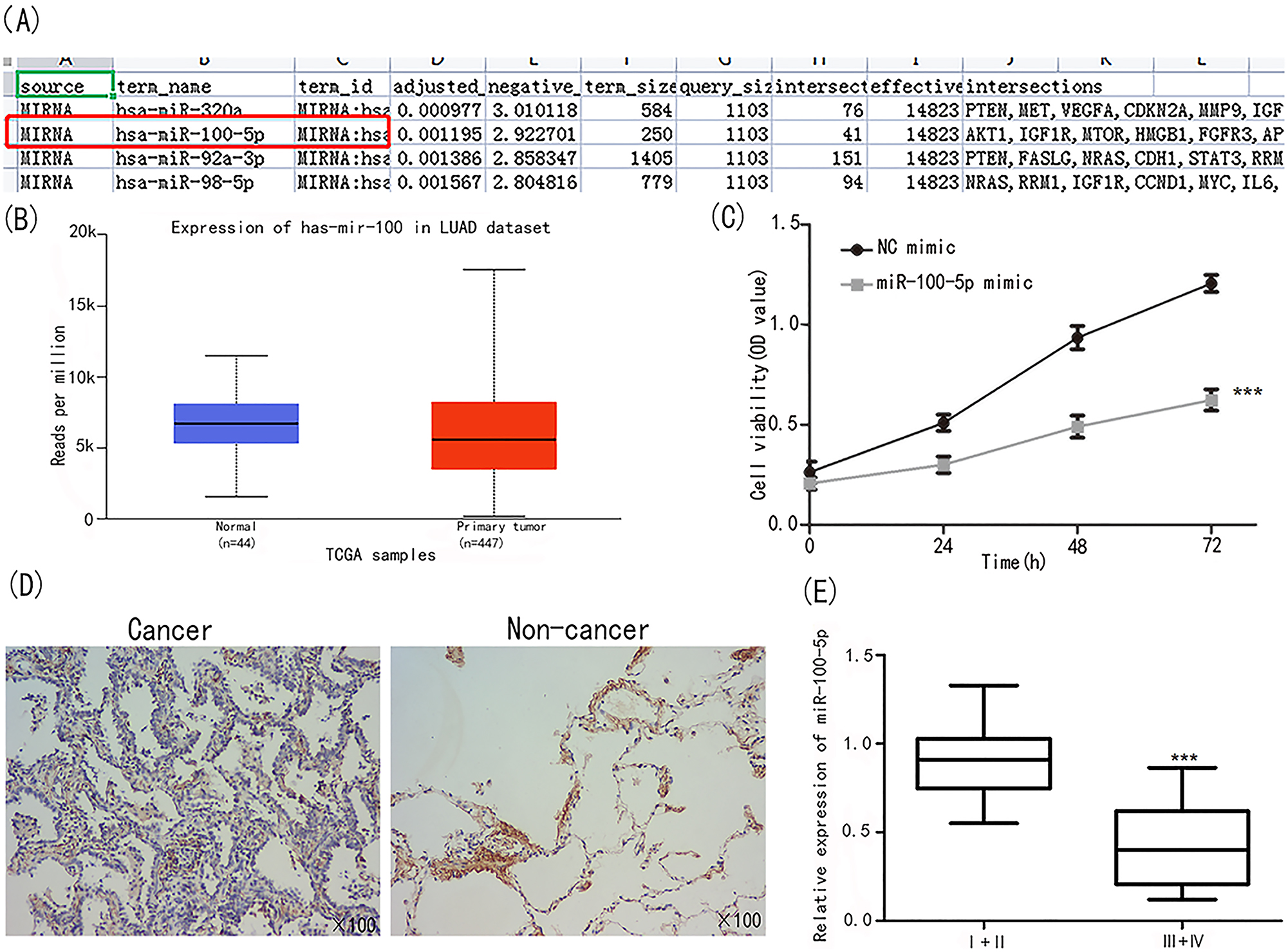

Genecard and G: profiler were used to obtain the miR-100-5p expression profile (Figure 1A). Additionally, investigations by UALCAN revealed that miR-100-5p was downregulated in NSCLC tissues vs. normal tissues (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1C, the proliferation of A549 cells was hindered in the miR-100-5p group (p<0.001). On the other hand, (Figure 1D), the ISH results revealed that individuals with NSCLC had a poorer outcome when miR-100-5p was downregulated. Figure 1E further demonstrates that patients in stages III+IV had substantially lower miR-100-5p expression than those in stages I+II.

Identification of miR-100-5p. (A) Genecard and G: profiler analysis showed miR-100-5p was related to lung cancer progression. (B) miR-100-5p was under expressed in NSCLC tissues. (C) A549 cell viability was significantly down regulated in the group of miR-100-5p. (D) ISH assay on evaluating miR-100-5 expression in cancer and non-cancer tissues. (E) MiR-100-5 expression was examined in patients at I+II and III+IV stages ***p<0.001 vs. I+II.

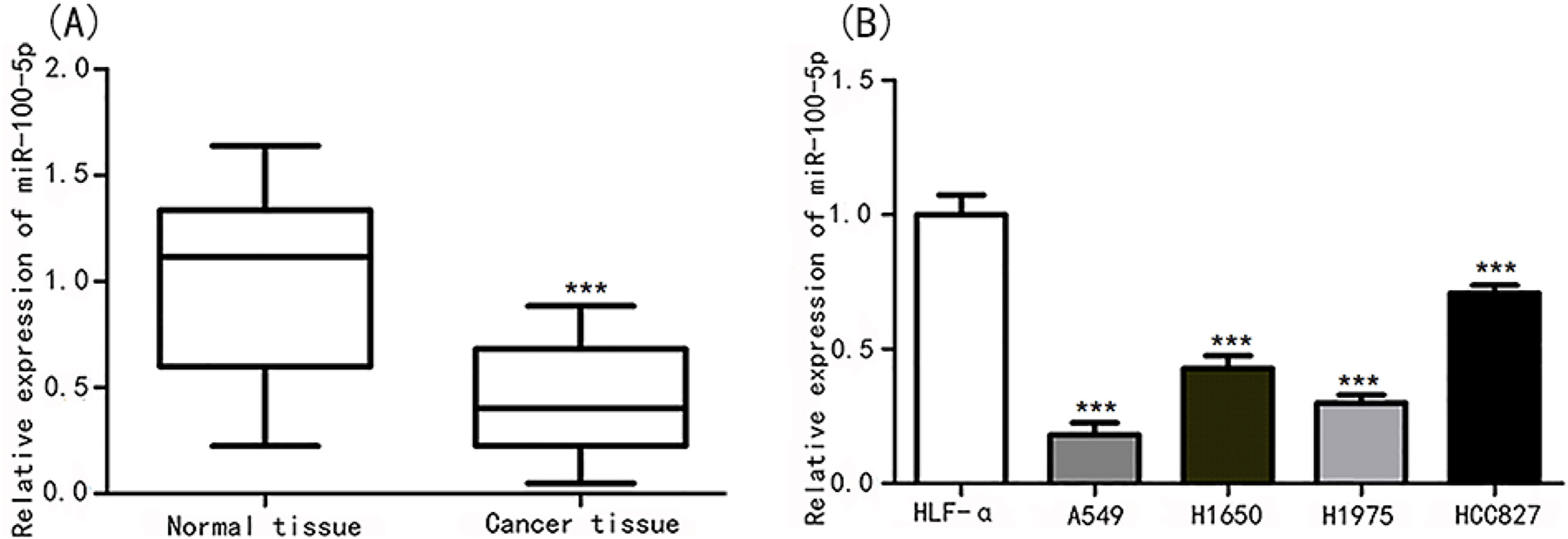

MiR-100-5p expression was considerably decreased in NSCLC tissues compared to normal tissues, as demonstrated in Figure 2A (p<0.01). MiR-100-5p expression was considerably downregulated in the A549 (p<0.01), H1650 (p<0.01), H1975 (p<0.01), and HCC827 (p<0.05) cell lines, as shown in Figure 2B. Then A549 cell line was chosen for in vitro functional research.

MiR-100-5p was descended in lung cancer tissues and cell lines. (A) MiR-100-5p expression was evaluated in lung cancer tissues and normal tissues. ***p<0.001 vs. normal tissues. (B) MiR-100-5p expression was assessed in lung cancer cell lines of HLF-α, A549, H1650, H1975, and HCC827. ***p<0.001 vs. HLF-α.

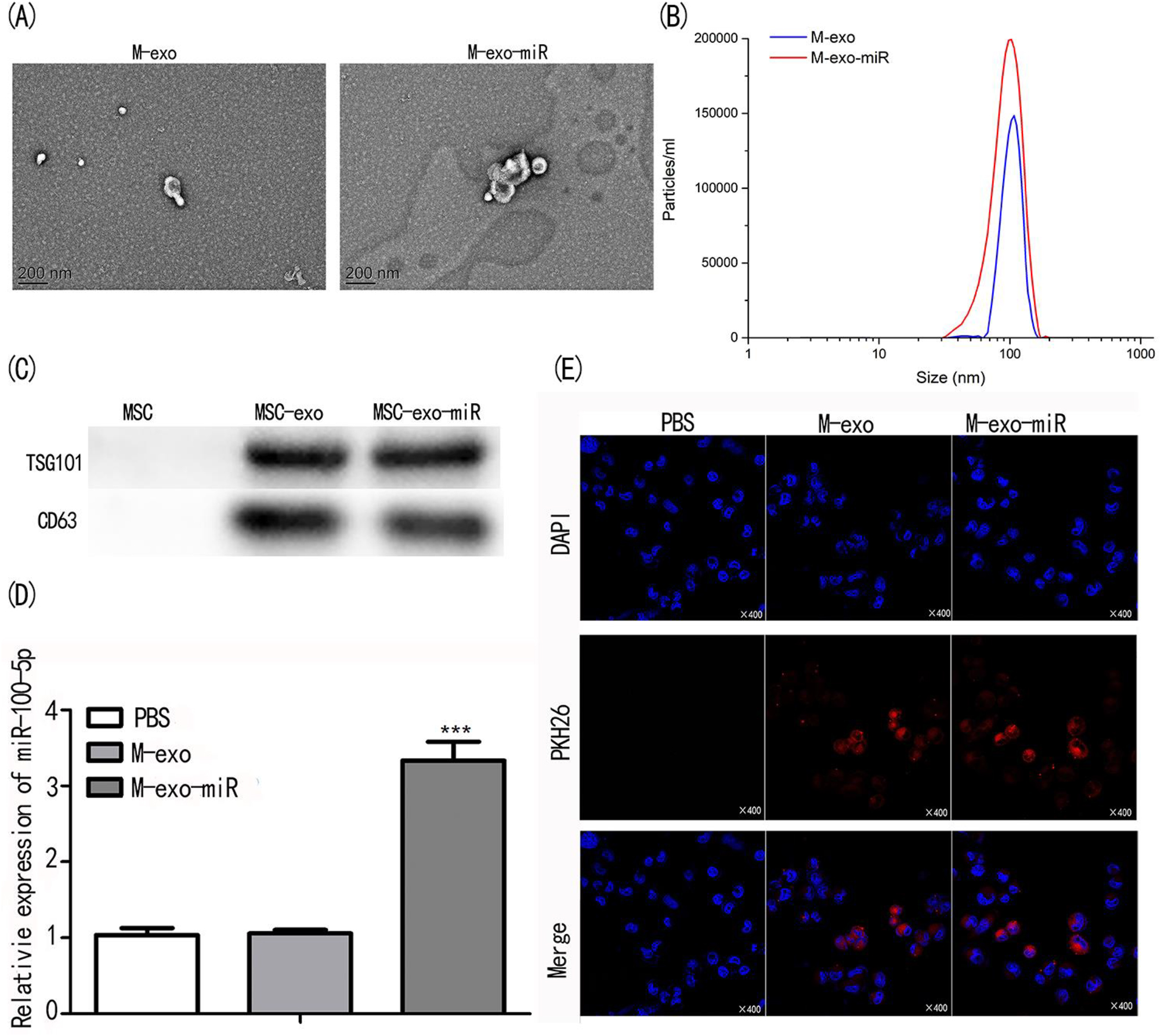

Transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes prevented the growth of A549 cells in vitro

To explore the functions of M-exo and their effects on tumor development, we isolated exosomes from the supernatant of MSCs; miR-100-5p was then transfected into exosomes. We observed the typical morphology of M-exo under TEM (Figure 3A). NTA suggested that the size of M-exo-miR (range 40–140 nm) was slightly bigger than that of M-exo (30–120 nm) (Figure 3B). As exosome-specific proteins, CD63 and TSG101 were detected in MSCs-derived exosomes by Western blot assay. The protein expression levels of TSG101 and CD63 increased significantly in M-exo and M-exo-miR compared with purified MSCs, revealing the successful transfection of miR-100-5p in exosomes (Figure 3C). In addition, the miR-100-5p expression level was significantly upregulated in M-exo-miR compared with that in MSCs and M-exo (p<0.001; Figure 3D). We confirmed the specific uptake capacity of A549 cells on self-derived exosomes by labeling M-exo-miR with the fluorescent dye PKH26 and then cultured them with A549 cells. The strongest red fluorescence was observed in A549 cells (Figure 3E). These results revealed the successful delivery of miR-100-5p by the constructed exosomes.

Identification and cell uptake of exosomes. (A) The morphology of exosomes of M-exo and M-exo-miR were observed under TEM. (B) The size distribution of transfected exosomes. (C) The exosome biomarkers of TSG101 and CD63 were analyzed by western blot assay. (D) MiR-100-5p expression in transfected exosomes were evaluated by qPCR. (E) PKH26 staining on MSCs, M-exo, and M-exo-miR.

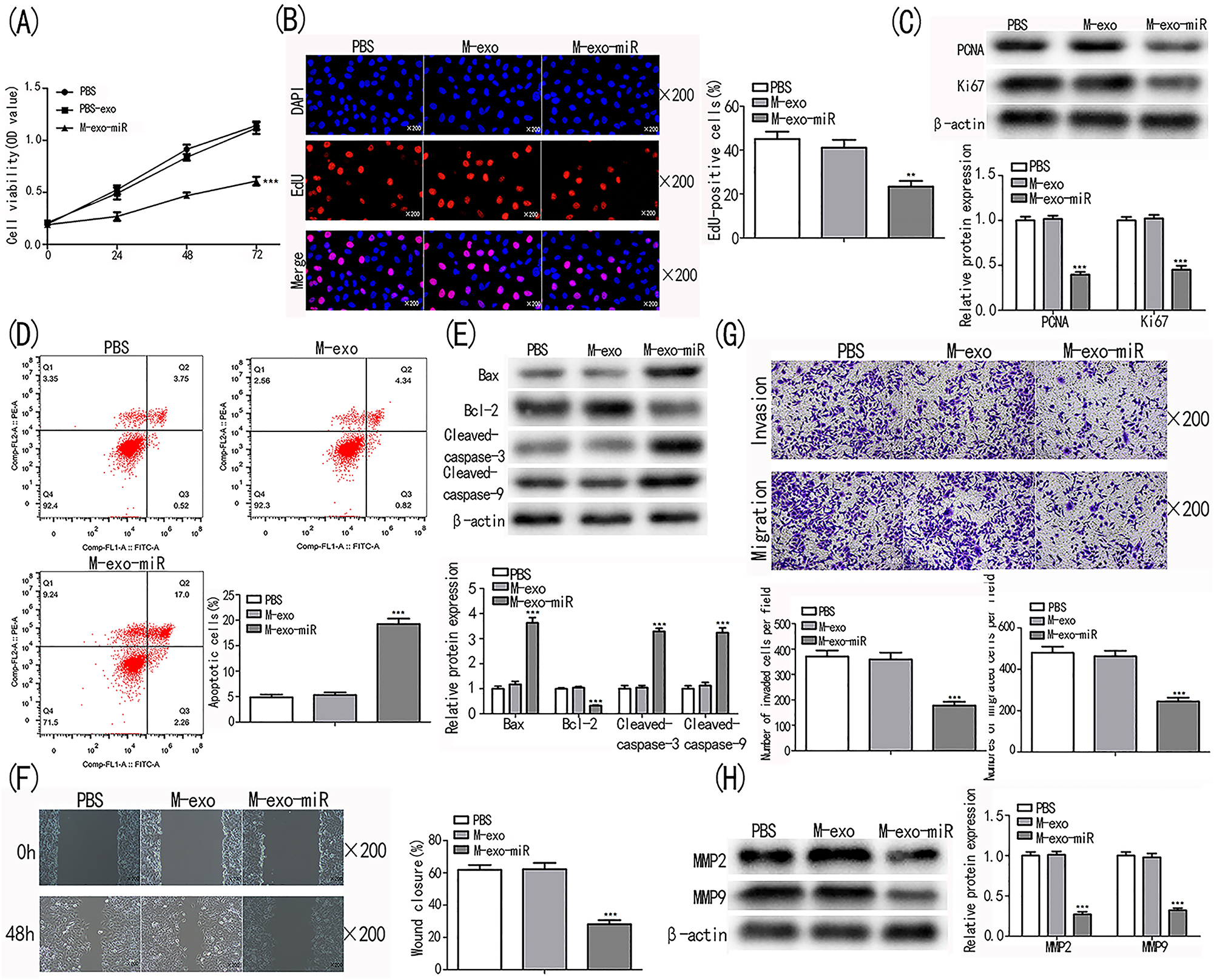

In comparison to the PBS and M-exo groups, the OD450nm value in the M-exo-miR group was considerably lower (p<0.001; Figure 4A). Compared to the PBS and M-exo groups, the EdU-positive cells in the M-exo-miR group were considerably decreased (p<0.001; Figure 4B). When compared to the PBS and M-exo groups, the levels of PCNA and Ki67 were considerably reduced in the M-exo-miR group (p<0.001; Figure 4C).

Transfected exosomes prevent lung cancer cell from proliferating, migrating, invading and promotes cell apoptosis. (A, B) Cell proliferation in PBS, M-exo, and M-exo-miR was measured using the CCK-8 and EdU assays. (C) Cell proliferation biomarkers underwent a Western blot examination. (D) Analysis using flow cytometry was performed to evaluate cell apoptosis. (E) Western blot analysis was used to determine the levels of the cell apoptosis indicators cleaved-caspase-9, cleaved-caspase-3, and Bax in the PBS, M-exo, and M-exo-miR groups. (F) The cell migration of cells in the PBS, M-exo, and M-exo-miR groups was examined using the wound-healing assay. (G) Detecting cell invasion and migration in the PBS, M-exo, and M-exo-miR groups using the Transwell test. (H) Western blot analysis was performed to examine the biomarkers of migration and invasion. ***p<0.001 vs. PBS.

On the other hand, M-exo-miR group cells had a substantially higher rate of apoptosis than PBS and M-exo group cells (p<0.001; Figure 4D). Furthermore, compared to those in the PBS and M-exo groups, the levels of the apoptosis-related proteins cleaved-caspase-9, cleaved-caspase-3, and Bax were markedly up-regulated in the M-exo-miR group, whereas the levels of Bcl-2 were significantly decreased (p<0.001; Figure 4E). These results demonstrated that exosomal miR-100-5p produced from MSCs inhibited the proliferation and promoted the apoptosis of NSCLC cells.

Exosomal miR-100-5p significantly abated the capacity of NSCLC cells to migrate, as seen in Wound Healing and Transwell experiments, in comparison to the cells in the PBS and M-exo groups (p<0.001; Figure 4F). In M-exo-miR group, the quantities of migrated and invaded cells as well as the expression levels of biomarkers were dramatically reduced (p<0.001; Figure 4G and H).

miR-100-5p activated EMT and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways in A549 cells

Activation of the EMT and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways is essential for tumor progression. The roles of exosomal miR-100-5p in EMT and the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway were assessed. Western blot assay demonstrated that E-cadherin was significantly down-regulated in the TGF-β, TGF-β+M-exo, and TGF-β+M-exo-miR groups (p<0.001; Figure 5A). N-cadherin, α-SMA, and Vimentin exhibited opposing expression, revealing that EMT was repressed by miR-100-5p. The results from immunofluorescence were similar to those of Western blot (Figure 5B), indicating that exosomal miR-100-5p inhibited EMT to suppress NSCLC cell progression.

Transfected exosome inhibits cell progression through EMT and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. (A, B) The expression level of EMT biomarkers were evaluated by assays of western blot and immunofluorescence. (C, D) The expression level of genes related to PI3K-AKT-mTOR were assessed by assays of qRT-PCR and Western blot. ***p<0.001 vs. PBS. ###p<0.001 vs. PBS.

The expression levels of PI3K, AKT, mTOR were assessed utilizing qRT-PCR and Western blot assays. They were significantly downregulated in the M-exo-miR group compared with the PBS and M-exo groups (p<0.001; Figure 5C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that exosomal miR-100-5p inhibits the activity of NSCLC cells by repressing the EMT and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways.

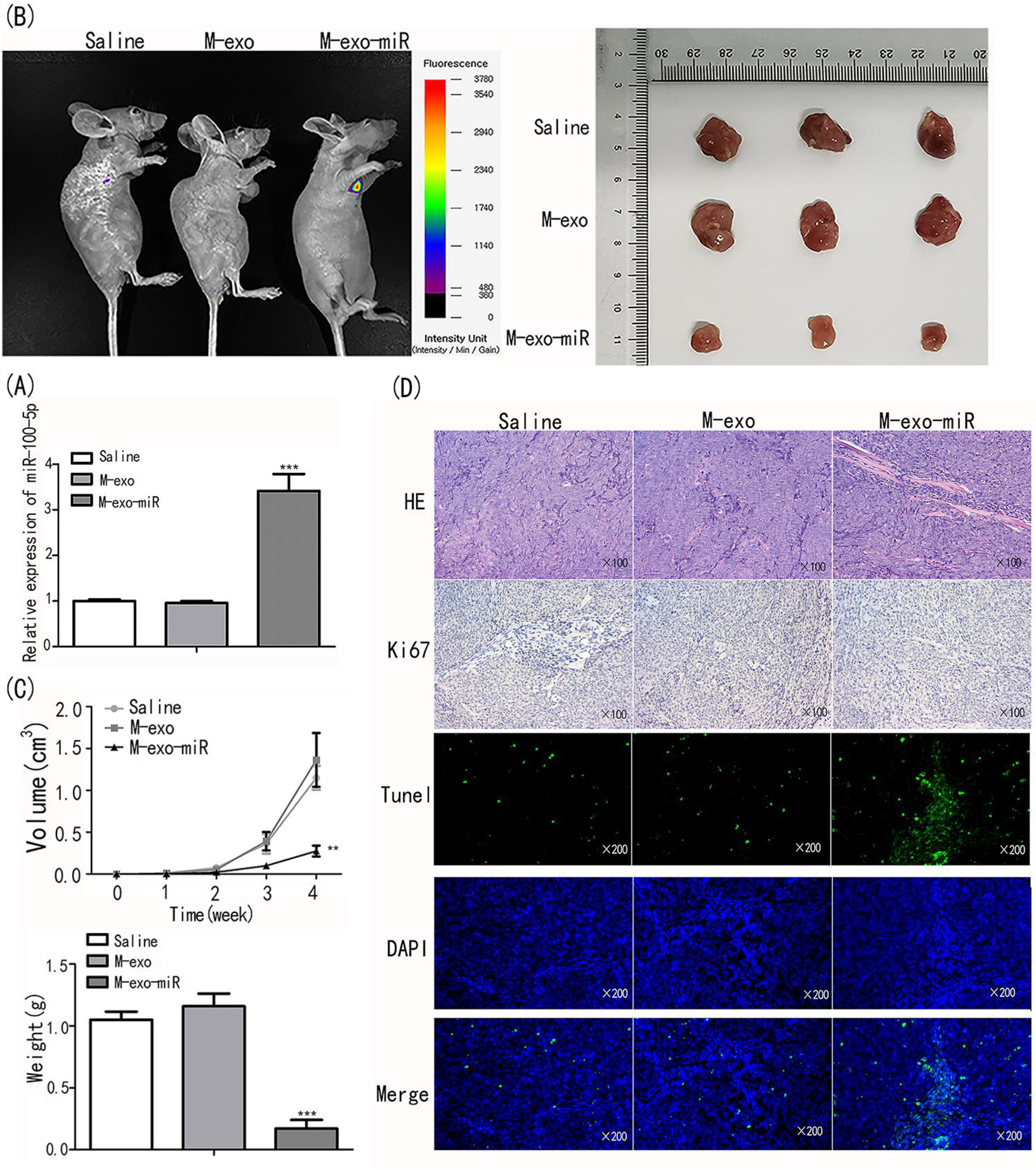

Role of miR-100-5p in NSCLC in vivo and the safety of miR-100-5p in healthy mice

Following injection, tumor tissues treated with saline, M-exo, and M-exo-miR were examined for miR-100-5p levels. As anticipated, the M-exo-miR group showed a considerably greater expression level than the other groups (p<0.001; Figure 6A). Compared to the saline and M-exo groups, the fluorescence intensity was considerably higher in the M-exo-miR group (p<0.001; Figure 6B). In addition, M-exo-miR-injected mice had considerably lower tumor volumes and weights than mice treated with saline plus M-exo (p<0.001; Figure 6C).

Transfected exosomes inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis, thus inhibiting tumor growth. (A) MiR-100-5p expression was evaluated using qRT-PCR. (B) The fluorescence intensity was assessed in animals injected with saline, M-exo, and M-exo-miR. (C) The tumor size, weight and volume were assessed. (D) HE/Ki67/TUNEL staining was performed on tumor tissues.

To explore the mechanism of M-exo-miR in tumor regression, tumor tissues were submitted to H&E, Ki67, and TUNEL staining. In contrast to those treated with saline and M-exo, the tumor tissues injected with M-exo-miR showed more fibers and fewer blood vessels, suggesting that miR-100-5p attenuated malignancy. In addition, Ki67 immunohistochemistry was used to gauge the proliferation of NSCLC cells. The findings revealed that in the M-exo-miR group, compared to those in the other groups, the number of positively stained cells was much lower, indicating that in vivo cell proliferation was prevented. M-exo-miR injection dramatically increased the apoptosis of cancer cells during TUNEL labeling (Figure 6D). According to these findings, exosomal miR-100-5p prevented tumor development in vivo.

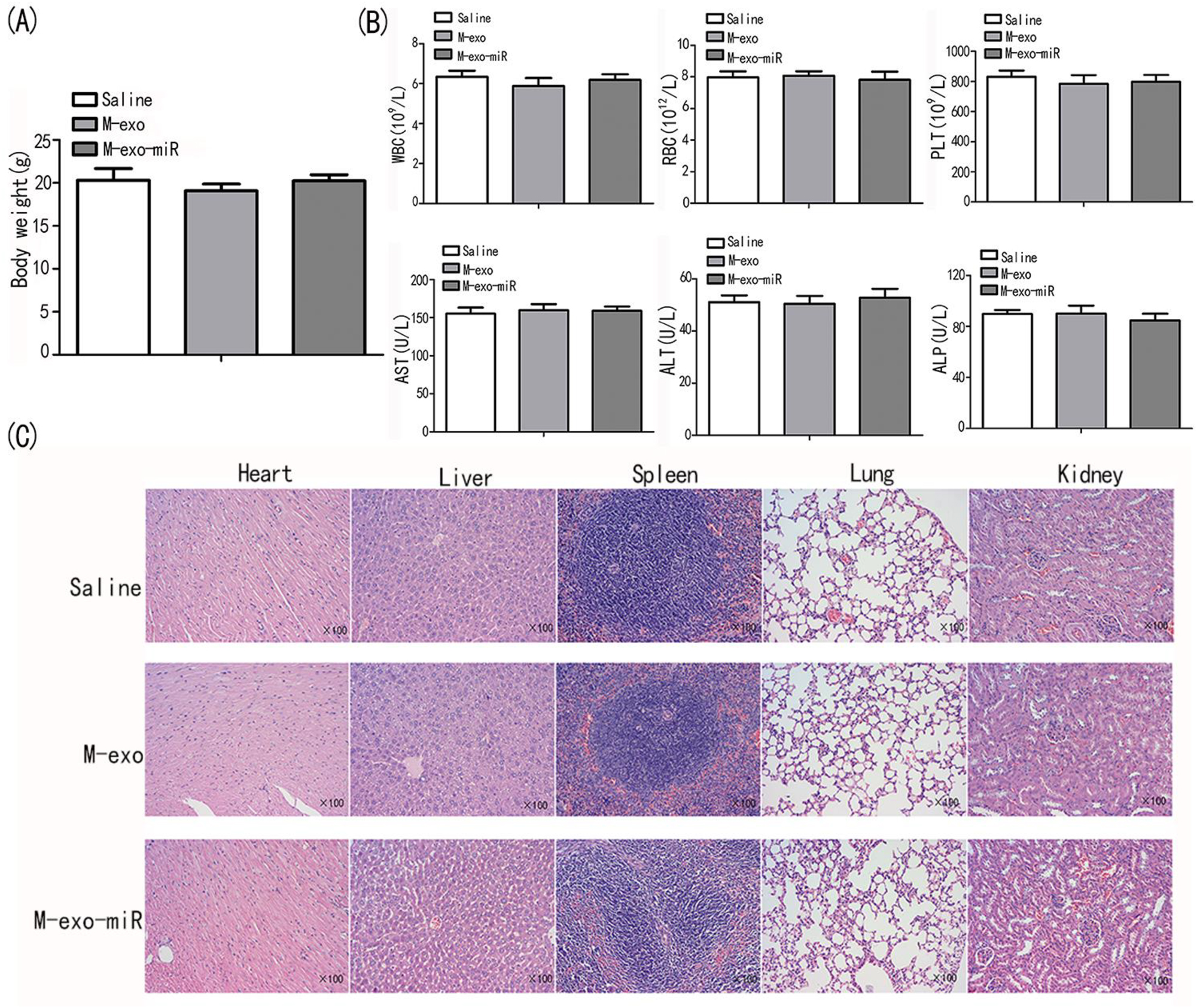

The nine nude mice in the three groups (n=3 per group) received saline, M-exo, and M-exo-miR. The mice were sacrificed at four weeks after injection. Serological indicators did not significantly change across the three groups (Figure 7A–C), indicating that M-exo-miR did not negatively affect the hepatic and hematopoietic systems. Additionally, HE staining did not reveal any overt harm to the vital organs of mice.

Transfected exosomes are safe for nude mice. (A) The body weight of BALB/c nude mice were measured in saline, M-exo, and M-exo-miR groups. (B) The physiological indicators of AST, ALT, ALP, RBC, WBC, and PLT were assessed in saline, M-exo, and M-exo-miR groups. (C) The HE staining of heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney in saline, M-exo, and M-exo-miR groups.

Discussion

Approximately 85 % of all diagnosed lung cancers are diagnosed as NSCLC, accounting for the majority of cancer-related fatalities worldwide [13]. Most cases are diagnosed in the middle or advanced stage, at which point the prognosis is poor. Surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy are the major methods for managing lung cancer. However, the outcomes remain unsatisfactory.

MiRNAs are principal bioactive factor abundant in exosomes. Exosomal noncoding RNAs are stable in body fluids, and the exosomal membrane protects them from degradation by ribonuclease [14]. There are also different studies on miR-100 in NSCLC. First, different studies have revealed that in NSCLC issues or cells, miR-100 is down-regulated [15, 16]. Also, miR-100 can function as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC by regulating EMT and Wnt/β-catenin by targeting HOXA1 [17]. These results are consistent with those of our study. On the other hand, Qin et al. [5] demonstrated the downregulation of miR-100-5p in exosomes from cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells. In another study, miR-100-5p conferred resistance to the ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors Crizotinib and Lorlatinib in EML4-ALK positive NSCLC [18]. The specific mechanism of different results in NSCLC remains to be clarified in the future.

MSCs are pluripotent stem cells that can develop into various cell types and can be obtained from umbilical cord, dental pulp, bone marrow, placenta, and other tissues [19]. MSCs are naturally characterized by low immunogenicity and inherent antitumor activities, making them ideal drug delivery and therapeutic agents. However, ectopic tissue formation, high cost, host cell rejection, and lack of a stable cell supply limit the application of MSCs therapy [14].

Exosomes are nanosized vesicles that are released into the cell microenvironment under pathological or normal conditions by various cells, such as MSCs. They play a significant role in intracellular communications. Exosomes derived by MSCs can be incorporated by recipient cells in vivo, and their lipid membranes can protect their contents, such as DNA, miRNA, lipids, or proteins, from degradation by enzymes in body fluids [14].

Of note, due to the different sources of MSCs-exosomes, their effects on tumor are different (promoting or inhibiting). A meta-analysis reported that only 46 and 26 % of previous studies found a tumor-suppressive impact of adipose tissue-derived MSCs (AT-MSCs) and bone marrow-derived MSCs (BM-MSCs), respectively, but 88 % of studies verified a tumor-suppressive function of hUC-MSCs [19]. That is the reason why we choose hUC-MSCs as the source of exosomes.

In the current investigation, we discovered that exosomes from MSCs triggered EMT and enhanced NSCLC cell motility and invasion. Transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes, on the other hand, markedly reduced the ability of A549 cells to proliferate, migrate, invade and promoted apoptosis. Transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes suppressed cancer cell proliferation and promoted apoptosis in vivo, slowing the spread of the disease. Additionally, we discovered that transfection arrested cell growth by inhibiting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and EMT pathways.

In this study, M-exo-miR had a suppressive effect and M-exo had a promotive effect on NSCLC. Previous studies have shown that MSCs-exosome may have an opposite effect on tumor, which can promote or inhibit the progression of cancers [19, 20]. These findings could be attributed to the sources of MSCs, experimental designs, conditions under which stem cells were cultured, treatments, administration techniques, and the environment and interactions between cancer and stem cells [20]. These results indicated that transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes could be conveyed to tumor cells to inhibit EMT and the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and suppress the development of NSCLC. Moreover, this transfection was not toxic to BALB/c nude mice. To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluates the efficacy of transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes in lung cancer.

Studies have uncovered that the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway is involved in the proliferation of NSCLC cells [21, 22]. In the present study, MSCs-derived exosomes delivered miR-100-5p into lung cancer cells and repressed the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, thus inhibiting progression-related behaviors of cancer cells. Pakravan et al. [23] revealed that exosomal miR-100 derived from MSCs acts on breast cancer cells through mTOR signaling. Ye et al. [24] also found that miR-100-5p blocks mTOR to restrain prostate cancer cell growth. Our present study, for the first time, confirmed that transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes can repress NSCLC progression in vitro and in vivo via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway.

EMT signaling is closely correlated with metastasis, recurrence, or therapeutic resistance [25, 26]. In our study, EMT was inhibited by transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes. According to the study of Zhang et al. [27], transfecting exosome-mediated miRNAs could enhance the invasion of lung cancer via activation of the transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling to induce EMT. However, whether EMT is inhibited by the PI3K-AKT-mTOR singaling pathway should be resolved in future studies.

The present study also has limitations. First, the interaction between PI3K-AKT-mTOR and EMT was not analyzed. Second, transfection of miR-100-5p may have a pluralistic effect on lung cancer, which should be elucidated with more experiments.

Conclusions

Transfecting miR-100-5p into MSCs-derived exosomes prevents NSCLC progressing in vitro and in vivo by repressing the EMT and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways. Our present study might provide a novel biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer.

Funding source: Taizhou People’s Hospital Research Fund project None

Award Identifier / Grant number: ZL202206

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate the supports by all participants.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Nanjing Medical University (NO. IACUC-2109040) and the Affiliated Sir Run Run Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (NO. 2021-SR-025).

-

Author contributions: (I) Conception and design: Ganzhu Feng and Jing Wei; (II) Data collection and analysis: Jing Wei and Tianyu Chen; (III) Manuscript writing: Jing Wei and Tianyu Chen; (IV) Final approval of the manuscript: All authors.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by Taizhou People’s Hospital Research Fund project (NO.ZL202206).

-

Data availability: The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of the present study are available within the article and its supplementary information.

References

1. Singh, T, Fatehi, HM, Fatehi, HA. Non-small cell lung cancer: emerging molecular targeted and immunotherapeutic agents. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2021;1876:188636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188636.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Chen, SW, Zhu, SQ, Pei, X, Qiu, BQ, Xiong, D, Long, X, et al.. Cancer cell-derived exosomal circUSP7 induces CD8+ T cell dysfunction and anti-PD1 resistance by regulating the miR-934/SHP2 axis in NSCLC. Mol Cancer 2021;20:144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01448-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. O’Brien, J, Hayder, H, Zayed, Y, Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front Endocrinol 2018;9:402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00402.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Oveili, E, Vafaei, S, Bazavar, H, Eslami, Y, Mamaghanizadeh, E, Yasamineh, S, et al.. The potential use of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes as microRNAs delivery systems in different diseases. Cell Commun Signal 2023;21:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-022-01017-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Qin, X, Yu, S, Zhou, L, Shi, M, Hu, Y, Xu, X, et al.. Cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cell–derived exosomes increase cisplatin resistance of recipient cells in exosomal miR-100-5p-dependent manner. Int J Nanomed 2017;12:3721–33. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s131516.Search in Google Scholar

6. Khan, FH, Reza, MJ, Shao, YF, Perwez, A, Zahra, H, Dowlati, A, et al.. Role of exosomes in lung cancer: a comprehensive insight from immunomodulation to theragnostic applications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2022;1877:188776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188776.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Aday, S, Hazan-Halevy, I, Chamorro-Jorganes, A, Anwar, M, Goldsmith, M, Beazley-Long, N, et al.. Bioinspired artificial exosomes based on lipid nanoparticles carrying let-7b-5p promote angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Mol Ther 2021;29:2239–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.03.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Song, XJ, Zhang, L, Li, Q, Li, Y, Ding, FH, Li, X. hUCB-MSC derived exosomal miR-124 promotes rat liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy via downregulating Foxg1. Life Sci 2021;265:118821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118821.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Li, XM, Yu, WY, Chen, Q, Zhuang, HR, Gao, SY, Zhao, TL. LncRNA TUG1 exhibits pro-fibrosis activity in hypertrophic scar through TAK1/YAP/TAZ pathway via miR-27b-3p. Mol Cell Biochem 2021;476:3009–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-021-04142-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Wang, X, Li, T. Ropivacaine inhibits the proliferation and migration of colorectal cancer cells through ITGB1. Bioengineered 2021;12:44–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2020.1857120.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Zhang, T, Zhang, P, Li, HX. CAFs-derived exosomal miRNA-130a confers cisplatin resistance of NSCLC cells through PUM2-dependent packaging. Int J Nanomed 2021;16:561–77. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s271976.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Zhang, Z, Chen, Y, Min, L, Ren, C, Xu, X, Yang, J, et al.. miRNA-148a serves as a prognostic factor and suppresses migration and invasion through Wnt1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Plos One 2017;12:e0171751. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171751.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Thai, AA, Solomon, BJ, Sequist, LV, Gainor, JF, Heist, RS. Lung cancer. Lancet 2021;398:535–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00312-3.Search in Google Scholar

14. Liu, H, Deng, S, Han, L, Ren, Y, Gu, J, He, L, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cells, exosomes and exosome-mimics as smart drug carriers for targeted cancer therapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2022;209:112163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112163.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Zhang, XQ, Song, Q, Zeng, LX. Circulating hsa_circ_0072309, acting via the miR‐100/ACKR3 pathway, maybe a potential biomarker for the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of brain metastasis from non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Cancer Med 2023;12:18005–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.6371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Li, L, Zhu, H, Li, X, Ke, Y, Yang, S, Cheng, Q. Long non-coding RNA HAGLROS facilitates the malignant phenotypes of NSCLC cells via repressing miR-100 and up-regulating SMARCA5. Biomed J 2021;44(6 Suppl 2):S305–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2020.12.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Han, W, Ren, X, Yang, Y, Li, H, Zhao, L, Lin, Z. microRNA‐100 functions as a tumor suppressor in non‐small cell lung cancer via regulating epithelial‐mesenchymal transition and Wnt/β‐catenin by targeting HOXA1. Thorac Cancer 2020;11:1679–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13459.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Lai, Y, Kacal, M, Kanony, M, Stukan, I, Jatta, K, Kis, L, et al.. miR-100-5p confers resistance to ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors Crizotinib and Lorlatinib in EML4-ALK positive NSCLC. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019;511:260–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Zhang, F, Guo, J, Zhang, Z, Qian, Y, Wang, G, Duan, M, et al.. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome: a tumor regulator and carrier for targeted tumor therapy. Cancer Lett 2022;526:29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.11.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Yassine, S, Alaaeddine, N. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes and cancer: controversies and prospects. Adv Biol (Weinh) 2022;6:e2101050. https://doi.org/10.1002/adbi.202101050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Liu, F, Gao, S, Yang, Y, Zhao, X, Fan, Y, Ma, W, et al.. Antitumor activity of curcumin by modulation of apoptosis and autophagy in human lung cancer A549 cells through inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Oncol Rep 2018;39:1523–31. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2018.6188.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Tan, AC. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thorac Cancer 2020;11:511–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13328.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Pakravan, K, Babashah, S, Sadeghizadeh, M, Mowla, SJ, Mossahebi-Mohammadi, M, Ataei, F, et al.. MicroRNA-100 shuttled by mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes suppresses in vitro angiogenesis through modulating the mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling axis in breast cancer cells. Cell Oncol 2017;40:457–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-017-0335-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Ye, Y, Li, SL, Wang, JJ. miR-100-5p downregulates mTOR to suppress the proliferation, migration, and invasion of prostate cancer cells. Front Oncol 2020;10:578948. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.578948.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Otsuki, Y, Saya, H, Arima, Y. Prospects for new lung cancer treatments that target EMT signaling. Dev Dynam 2018;247:462–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.24596.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Tulchinsky, E, Demidov, O, Kriajevska, M, Barlev, NA, Imyanitov, E. EMT: a mechanism for escape from EGFR-targeted therapy in lung cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2019;1871:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.10.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Zhang, X, Sai, B, Wang, F, Wang, L, Wang, Y, Zheng, L, et al.. Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs promote metastasis of lung cancer cells via STAT3-induced EMT. Mol Cancer 2019;18:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-019-0959-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Mitochondrial thermogenesis in cancer cells

- Application of indocyanine green in the management of oral cancer: a literature review

- Long non-coding RNA, FOXP4-AS1, acts as a novel biomarker of cancers

- The role of synthetic peptides derived from bovine lactoferricin against breast cancer cell lines: a mini-review

- Single cell RNA sequencing – a valuable tool for cancer immunotherapy: a mini review

- Research Articles

- Global patterns and temporal trends in ovarian cancer morbidity, mortality, and burden from 1990 to 2019

- The association between NRF2 transcriptional gene dysregulation and IDH mutation in Grade 4 astrocytoma

- More than just a KRAS inhibitor: DCAI abrogates the self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells in vitro

- DUSP1 promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion by upregulating nephronectin expression

- IMMT promotes hepatocellular carcinoma formation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

- MiR-100-5p transfected MSCs-derived exosomes can suppress NSCLC progression via PI3K-AKT-mTOR

- Inhibitory function of CDK12i combined with WEE1i on castration-resistant prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic potential of m7G-associated lncRNA signature in predicting bladder cancer response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy

- Case Reports

- A rare FBXO25–SEPT14 fusion in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia treatment to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a case report

- Stage I duodenal adenocarcinoma cured by a short treatment cycle of pembrolizumab: a case report

- Rapid Communication

- ROMO1 – a potential immunohistochemical prognostic marker for cancer development

- Article Commentary

- A commentary: Role of MTA1: a novel modulator reprogramming mitochondrial glucose metabolism

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Mitochondrial thermogenesis in cancer cells

- Application of indocyanine green in the management of oral cancer: a literature review

- Long non-coding RNA, FOXP4-AS1, acts as a novel biomarker of cancers

- The role of synthetic peptides derived from bovine lactoferricin against breast cancer cell lines: a mini-review

- Single cell RNA sequencing – a valuable tool for cancer immunotherapy: a mini review

- Research Articles

- Global patterns and temporal trends in ovarian cancer morbidity, mortality, and burden from 1990 to 2019

- The association between NRF2 transcriptional gene dysregulation and IDH mutation in Grade 4 astrocytoma

- More than just a KRAS inhibitor: DCAI abrogates the self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells in vitro

- DUSP1 promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and invasion by upregulating nephronectin expression

- IMMT promotes hepatocellular carcinoma formation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

- MiR-100-5p transfected MSCs-derived exosomes can suppress NSCLC progression via PI3K-AKT-mTOR

- Inhibitory function of CDK12i combined with WEE1i on castration-resistant prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo

- Prognostic potential of m7G-associated lncRNA signature in predicting bladder cancer response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy

- Case Reports

- A rare FBXO25–SEPT14 fusion in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia treatment to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a case report

- Stage I duodenal adenocarcinoma cured by a short treatment cycle of pembrolizumab: a case report

- Rapid Communication

- ROMO1 – a potential immunohistochemical prognostic marker for cancer development

- Article Commentary

- A commentary: Role of MTA1: a novel modulator reprogramming mitochondrial glucose metabolism