Abstract

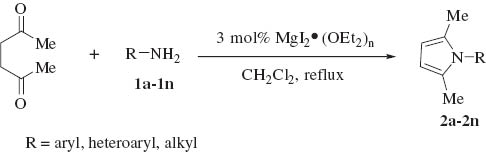

We describe a convenient and useful procedure for the synthesis of various 2,5-dimethyl-N-substituted pyrrole derivatives by the addition of 2,5-hexadione with aromatic amines, heteroaromatic amines and aliphatic amines catalyzed by MgI2 etherate (MgI2·(OEt2)n) in good to excellent yields.

Introduction

Pyrroles are important heterocyclic compounds displaying remarkable pharmacological properties such as antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antitumoral and antioxidant activities (Fürstner et al., 1998; Jacobi et al., 2000; Fürstner, 2003). Furthermore, pyrroles are also considered to be important building blocks in many naturally occurring compounds such as heme, chlorophyll and vitamin B12 (Santo et al., 1998; Ragno et al., 2000; Hoffmann and Lindel, 2003; Bellina and Rossi, 2006). In view of their important significance, preparation of pyrroles has attracted considerable attention of chemists in recent years. Many methodologies have been developed for the construction of the pyrrole moiety regarded as skeleton (Fang et al., 2012; Heugebaert et al., 2012). Among them, the Paal-Knorr synthesis remains the most useful preparative method for generating pyrroles (Aghapoor et al., 2012; Balme, 2012; Rahmatpour, 2012).

Recently, many methods for the synthesis of pyrroles, such as Paal-Knorr cyclization of primary amines and 1,4-diketones, have been developed in the presence of various Lewis acid catalysts, such as Ti(OiPr)4 (Yu and Quesne, 1995), ZrOCl2·8H2O (Rahmatpour, 2011), Sc(OTf)3 (Chen et al., 2006), Bi(NO3)3·5H2O (Banik et al., 2004), UO2(NO3)2·6H2O (Satyanarayana and Sivakumar, 2011), BiCl3/SiO2 (Aghapoor et al., 2012), InCl3 (Shanthi and Perumal, 2009) and FeCl3 (Azizi et al., 2009). Some of the synthetic protocols suffer from disadvantages, such as the use of stoichiometric and even excess amounts of catalyst, harsh reaction conditions, prolonged reaction time, expensive reagents and low yield of the products. From the above viewpoints, the development of less expensive, environmentally benign and easily handled promoters for the synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles by Paal-Knorr condensation under neutral, mild and convenient condition is still highly desirable.

MgI2 etherate is easily preparative, inexpensive and easier to be handled than other metal halides such as Ti(OiPr)4, InCl3 and Sc(OTf)3. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of the use of MgI2 etherate as a mild catalyst for the Paal-Knorr reaction. In the continuation of our research field, herein, we will wish to report a simple and efficient procedure for the Paal-Knorr pyrrole condensation of primary amines with 2,5-hexadione catalyzed by MgI2 etherate under mild reaction conditions in good to excellent yields (Scheme 1).

MgI2 etherate catalyzed Paal-Knorr condensation.

Results and discussion

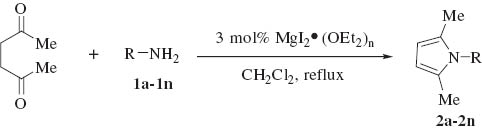

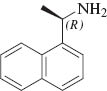

We initiated our studies by carrying out the Paal-Knorr condensation of aniline with 2,5-hexadione in the presence of 3 mol% of MgI2 etherate (1.0 m in Et2O/benzene 1:2) in CH2Cl2 at room temperature. After stirring for 2.0 h, the desired 2,5-dimethyl-N-phenyl pyrrole (2a) was afforded in 93% yield. In order to evaluate the generality of this process, a variety of diversified examples illustrating the present method for the synthesis of 2,5-dimethyl-N-substituted pyrroles (2b–2o) were studied. The results are listed in Table 1. The reaction of 2,5-hexadione with a series of aromatic substituted primary amines bearing either electron-donating (Table 1, entries 2–5) or electron-withdrawing (Table 1, entries 6–9) groups on the aromatic ring was carried out as catalyzed by 3 mol% of MgI2 etherate under mild conditions. As shown in Table 1, the reaction proceeded smoothly in Dichloromethane (DCM) at reflux and provided a single product without any side products in good to excellent yields. Furthermore, the substitution group on the phenyl ring could affect the yield and reaction rate in the Paal-Knorr reaction. We have observed the reactivity of anilines bearing an electron-donating group (i.e., -OMe, -OEt) reacted much faster than aniline-bearing electron-withdrawing group (i.e. -Cl, -F, -NO2) and provided the corresponding products in excellent yields. The Paal-Knorr condensation of 2,6-diisopropylaniline with 2,5-hexadione also gave a good yield although it has a more sterically hindered effect (Table 1, entry 5). Furthermore, we have examined the Paal-Knorr reaction of aliphatic amines with 2,5-hexadione (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). Also, the corresponding products were obtained with excellent yields. Unfortunately, no reaction of tert-butylamine with 2,5-hexadione was observed under the same conditions, due to its higher steric hindrance. Under further observation, it is observed that the reaction of chiral amine such as (R)-(+)-1-(1-naphthyl)ethylamine 1l with 2,5-hexadione provided the optically pyrrole derivative without racemization. Moreover, we examined the reactivity of heterocyclic amines with 2,5-hexadione in the presence of MgI2 etherate. Thus, using 3 mol% of MgI2 etherate the Paal-Knorr reaction of heterocyclic amine such as 2-aminopyridine (1m) affords 2-(2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)pyridine (2m) in 92% yield (Table 1, entry 13). Therefore, heterocyclic amines exhibited analogous behavior to that of aromatic amines and aliphatic amines. Interestingly, the condensation of (R)-2-amino-2-phenylacetamide, which has two amino groups, exclusively gave (R)-2-(2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-phenylacetamide (2n) with the retention of absolute configuration.

Paal-Knorr condensation of 2,5-hexadione catalyzed by MgI2 etheratea.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Amine | t (h) | Productb | Yield (%)c |

| 1 | C6H5NH2 | 2 | 2a | 93 |

| 2 | 3-MeOC6H4NH2 | 4 | 2b | 80 |

| 3 | 3,4-(MeO)2C6H3NH2 | 2 | 2c | 95 |

| 4 | 4-EtOC6H4NH2 | 2 | 2d | 92 |

| 5 | 2,6-(iPr)2C6H3NH2 | 8 | 2e | 76 |

| 6 | 2-FC6H4NH2 | 6 | 2f | 74 |

| 7 | 3,5-F2C6H3NH2 | 4 | 2g | 73 |

| 8 | 3-ClC6H4NH2 | 2 | 2h | 86 |

| 9 | 4-NO2C6H4NH2 | 10 | 2i | 78 |

| 10 | 4-CH3OC6H4CH2NH2 | 2 | 2j | 90 |

| 11 | 4-ClC6H4(CH2)2NH2 | 2 | 2k | 97 |

| 12 |  | 2 | 2l | 78 |

| 13 |  | 2 | 2m | 92 |

| 14 |  | 8 | 2n | 70 |

aThe reaction was carried out by the condensation of 2,5-hexadione (6 mmol) with primary amine (5 mmol) catalyzed by 3 mol% of MgI2 etherate.

bAll products were identified by their 1H NMR spectra.

cYields of products isolated by column chromatography.

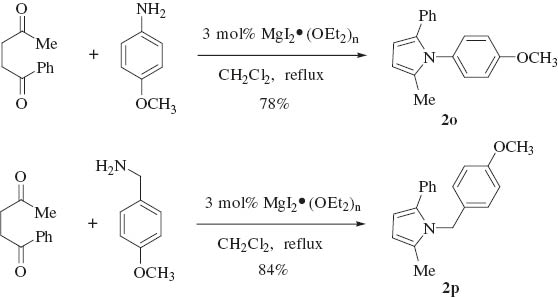

The reaction using MgI2 etherate as a catalyst has shown an important feature, that is, the ability to tolerate various amines including aliphatic, aromatic and heterocyclic amines. To extend the scope of MgI2 etherate-catalyzed Paal-Knorr condensation for the synthesis of N-substituted pyrrole derivatives, other substituted diketones such as 1,4-diphenylbutane-1,4-dione and 1-phenylpentane-1,4-dione were investigated. Unfortunately, no reaction of 1,4-diphenylbutane-1,4-dione with p-methoxyaniline occurred. The condensation of 1-phenylpentane-1,4-dione with p-methoxyaniline or p-methoxybenzyl amine resulted in good yields (Scheme 2).

Paal-Knorr condensation with 1-phenylpentane-1,4-dione catalyzed by MgI2 etherate.

The high coordinating ability of magnesium (II) towards oxygen atoms of the carbonyl moiety is presumably responsible for the effective activation of ketonic carbonyl. To examine the halide anion effect, halogen analogs of MgI2 etherate, MgCl2 etherate and MgBr2 etherate were compared under parallel reaction conditions (3 mol% of catalyst) in the Paal-Knorr condensation of aniline with 2,5-hexadione. MgCl2 etherate and MgBr2 etherate are less effective in terms of substrate conversion yield and provide the moderate yields. Apparently, the unique reactivity of MgI2 etherate is attributed to the dissociative character of iodide counterion and a more Lewis acidic cationic [MgI]+ species.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the unique reactivity of MgI2 etherate in the Paal-Knorr reaction for the synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles. Compared to previously reported methodologies, the present protocol features simple operation, mild condition and good to excellent yield. Exploitation of this protocol for generation of novel multicyclic structures is actively pursued in our lab.

Experimental section

General methods

For product purification by flash column chromatography, silica gel (200–300 mesh) and light petroleum ether (PE, b.p. 60–90°C) were used. 1H NMR spectra were taken on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer (Switzerland) with Tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard and CDCl3 as solvent. The reaction monitoring was accomplished by thin layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel polygram SILG/UV 254 plates. FT-IR spectra were recorded with a Nicolet 6700 spectrophotometer with NaCl optics (Thermo Company, USA). Melting points were measured on BUCHI B-540. High resolution mass spectroscopy (HRMS) were determined on a Waters GCT Premier spectrometer (Waters Company, USA). Elemental analysis was performed on a VarioEL-3 instrument (Elementar, Germany). All compounds were identified by 1H NMR and are in good agreement with those reported. All starting materials and reagents are purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich company.

General procedure for the synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles

To a mixture of amine (5 mmol) and 2,5-hexadione (6 mmol, 1.1 equiv) in 5 mL dichloromethane was added 3 mol% freshly prepared MgI2 etherate (Arkley et al., 1962). The mixture was stirred at reflux for the appropriate time. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After reaction, the mixture was concentrated and the residue was purified on silica gel with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate as eluent.

1-Phenyl-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole(2a)

(Satyanarayana and Sivakumar, 2011): light yellow solid. Rf=0.67 (100% PE). m.p. 49–50°C (lit. 48–50°C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.11 (s, 6H), 5.98 (s, 2H), 7.27–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.44–7.47 (m, 1H), 7.50–7.54 (m, 2H).

1-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2b)

(Lee and Kim, 2013): light yellow liquid. Rf=0.42 (100% PE), 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.18 (s, 6H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 6.01(s, 2H), 6.88 (d, J=2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.89–6.94 (m, 1H), 7.05–7.7.07 (m, 1H), 7.46 (t, J=8.0 Hz, 1H).

1-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2c)

(Noberini et al., 2008): pale yellow liquid. Rf=0.18 (100% PE). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.09 (s, 6H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 5.93 (s, 2H), 6.78 (d, J=2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (dd, J=2.3, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H).

1-(4-Ethoxyphenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2d)

(Hazlewood et al., 1937): white solid. Rf=0.33 (100% PE). m.p. 59–61°C (lit. 63°C), FT-IR (KBr) υ (cm-1): 2983, 1514, 1475, 1404, 1290, 1246, 1169, 1052, 845, 768. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.55 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 3H), 2.12 (s, 6H), 4.16 (dd, J=5.0, 10.0 Hz, 2H), 5.98 (s, 2H), 7.03–7.07 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.23 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ=13.01, 14.90, 63.56, 105.06, 114.45, 128.72, 128.94, 131.31, 157.94. EI-MS-215 ([M]+, 100), 186 (62), 172 (10), 145 (14), 117 (12), 77 (5). Elemental analyses: calculated (%) for C16H21NO (243.16 g/mol): C 78.97; H 8.70; N 5.76, found: C 78.85, H 8.58, N 5.65.

1-(2,6-Diisopropylphenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2e)

(Chen et al., 2009): white solid. Rf=0.73 (PE:EA=10:1). m.p. 56–57°C (lit. 56–58°C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=1.16 (d, J=6.9, 12H), 1.95 (s, 6H), 2.0–2.1 (m, 2H), 5.98 (s, 2H), 7.28 (d, J=7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (t, J=7.7 Hz, 1H).

1-(2-Fluorophenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2f)

(Chen et al., 2009): yellow liquid. Rf=0.62 (PE:EA=10:1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=1.95 (s, 6H), 5.94 (s, 2H), 7.29 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.84–7.86 (m, 1H).

1-(3,5-Difluorophenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2g)

(Thomas et al., 2004): white solid. Rf=0.68 (PE:EA=10:1). m.p. 54.8–55.3°C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.09 (s, 6H), 5.93 (s, 2H), 6.81 (dd, J1=2.2, 7.4 Hz, 2H), 6.88–6.92 (m, 1H).

1-(3-Chlorophenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2h)

(Jafari et al., 2012): white solid. Rf=0.43 (100% PE). m.p. 48–49°C (lit. 47–49°C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.07 (s, 6H), 5.93 (s, 2H), 7.13–7.16 (m, 1H), 7.25–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.44 (m, 2H).

1-(4-Nitrophenyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2i)

(Satyanarayana and Sivakumar, 2011): yellow solid. Rf=0.35 (PE:EA=10:1). m.p. 142–143°C (lit. 143–144°C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.10 (s, 6H), 5.98 (s, 2H), 7.39–7.43 (m, 2H), 8.35–8.38 (m, 2H).

1-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2j)

(Chen et al., 2009): white solid. Rf=0.23 (100% PE). m.p. 75–76°C (lit. 76–77°C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.20 (s, 6H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 5.90 (s, 2H), 6.85–6.90 (m, 4H).

1-(4-Chlorophenethyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2k)

White solid. Rf=0.29 (100% PE). m.p. 64–66°C. FT-IR (KBr) υ (cm-1): 2970, 1518, 1492, 1411, 1298, 1094, 1017, 811, 715. lH NMR (500 MHz, CDC13): δ=2.16 (s, 6H), 2.90 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 2H), 3.97 (t, J=7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.82 (s, 2H), 7.01–7.03 (m, 2H), 7.27–7.30 (m, 2H). l3C NMR (125 MHz, CDC13): δ=12.44, 36.80, 44.92, 105.18, 127.05, 128.42, 130.03, 132.20, 136.68. EI-MS: 233 ([M]+, 20), 235 ([M+2]+, 7), 215 (8), 108 (100), 92 (16), 77 (18). Elemental analyses: calculated (%) for C14H16ClN (233.10 g/mol): C 71.94, H 6.90, N 5.99, found: C 71.85, H 6.78, N 5.87.

(R)-1-(1-(Naphthalen-1-yl)ethyl)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole (2l)

Yellow liquid, Rf=0.31 (PE:EA=10:1). FT-IR (KBr) υ (cm-1): 2978, 1566, 1516, 1448, 1420, 1245, 1212, 1060, 760. lH NMR (500 MHz, CDC13): δ=2.05 (d, J=7.1 Hz, 3H), 2.19 (s, 6H), 5.91 (s, 2H), 6.10 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.53-7.57 (m, 3H), 7.77-7.79 (m, 1H), 7.90-7.95 (m, 1H), 7.95–7.96 (m, 1H). l3C NMR (125 MHz, CDC13): δ=14.2, 20.5, 51.7, 106.5, 123.2, 123.4, 124.4, 126.7, 128.0, 128.4, 128.8, 129.4, 132.3, 135.3, 137.0. EI-MS: 249.1 (10), 155.2 (100), 149.2 (31), 95.2 (43), 81.2 (23). Elemental analyses: calculated (%) for C18H19N (249.15 g/mol): C 86.70, H 7.68, N 5.62, found: C 86.79, H 7.58, N 5.70.

2-(2,5-Dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)pyridine (2m)

(Chen et al., 2006): yellow liquid. Rf=0.54 (PE:EA=5:1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ=2.15(s, 6H), 5.93(s, 2H), 7.23–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.30–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.82–7.86 (m, 1H), 8.62–8.64 (m, 1H).

(S)-2-(2,5-Dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-2-phenylacetamide (2n)

Yellow solid. Rf=0.4 (PE:EA=3:1). m.p. 102.7–105.2°C. FT-IR (KBr) υ (cm-1): 2983, 1693, 1564, 1513, 1444, 1230, 1074, 840, 765. lH NMR (500 MHz, CDC13): δ=2.07 (s, 6H), 5.70 (s, 1H), 5.89 (s, 2H), 5.98 (s, 1H), 6.85 (s, 1H), 7.25–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.30 (s, 1H), 7.31–7.36 (m, 2H). l3C NMR (125 MHz, CDC13): δ=13.6, 61.1, 107.7, 127.8, 128.1, 128.4, 128.8, 135.4, 171.6. EI-MS: 228.1 (7), 185.4 (11), 184.3 (43), 94.7 (100), 106.4 (10). Elemental analyses: calculated (%) for C14H16N2O (228.13 g/mol): C 73.66, H 7.06, N 12.27, found: C 73.78, H 6.96, N 12.36.

1-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-methyl-5-phenyl-1H-pyrrole (2o)

(Lee and Kim, 2013): yellow solid. Rf=0.49 (PE:EA=10:1). m.p. 104–106°C. lH NMR (500 MHz, CDC13): δ=2.19 (s, 3H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 6.15 (d, J=3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (d, J=3.4 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J=8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.12–7.16 (m, 5H), 7.20 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 2H).

1-(4-Methoxybenzyl)-2-methyl-5-phenyl-1H-pyrrole (2p)

Yellow solid. Rf=0.68 (PE:EA=10:1). m.p. 91–92°C. FT-IR (KBr) υ (cm-1): 2930, 1550, 1510, 1444, 1403, 1240, 1170, 1033, 820. lH NMR (500 MHz, CDC13): δ=2.28 (s, 3H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 5.20 (s, 2H), 6.18 (d, J=3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (d, J=3.3 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J=5.2, 8.9 Hz, 4H), 7.27–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.40–7.46 (m, 4H). l3C NMR (125 MHz, CDC13): δ=12.5, 47.0, 55.1, 107.2, 107.9, 114.0, 126.5, 126.7, 128.3, 128.5, 130.3, 130.9, 133.8, 134.5, 158.1. EI-MS: 277.1 (8), 156.2 (2), 121.2 (100), 91.4 (11), 77.3 (13); elemental analyses: calculated (%) for C19H19NO (277.15 g/mol): C 82.28, H 6.90, N 5.05, found: C 82.41, H 6.79, N 5.15.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21372203 and 21272076) and the National University Student Innovation Test Plan (201310337007) for financial support.

References

Aghapoor, K.; Ebadi-Nia, L.; Mohsenzadeh, F.; Morad, M. M.; Balavar, Y.; Darabi, H. R. Silica-supported bismuth(III) chloride as a new recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for the Paal-Knorr pyrrole synthesis. J. Organomet Chem.2012, 708, 25–30.Search in Google Scholar

Arkley, V.; Attenburrow, J.; Gregory, G. I.; Walker, T. Griseofulvin analogues: Part I. Modification of the aromatic ring. J. Chem. Soc.1962, 1260–1268.10.1039/jr9620001260Search in Google Scholar

Azizi, N.; Khajeh-Amiri, A.; Ghafuri, H. Iron-catalyzed inexpensive and practical synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles in water. Synlett2009, 20, 2245–2248.Search in Google Scholar

Balme, G. Pyrrole syntheses by multicomponent coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2012, 43, 6238–6241.Search in Google Scholar

Banik, B. K.; Banik, I.; Renteria, M.; Dasgupta, S. K. Pyrrole synthesis in ionic liquids by Paal-Knorr condensation under mild conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 3417–3419.Search in Google Scholar

Bellina, F.; Rossi, R. Synthesis and biological activity of pyrrole, pyrroline and pyrrolidine derivatives with two aryl groups on adjacent positions. Tetrahedron2006, 62, 7213–7256.10.1016/j.tet.2006.05.024Search in Google Scholar

Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; Su, W. An approach to the Paal-Knorr pyrroles synthesis catalyzed by Sc(OTf)3 under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 5383–5387.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, J. X.; Yang, X. L.; Liu, M.C.; Wu, H. Y.; Ding, J. C.; Su, W. K. Approach to synthesis of β-enamino ketones and pyrroles catalyzed by gallium(III) triflate under solvent-free conditions. Synth. Commun.2009, 39, 4180–4198.Search in Google Scholar

Fang, Z. X.; Yuan, H. Y.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Z. X.; Li, H. Q.; Yang, J.; Barry, B. D.; Liu, J. Q.; Liao, P. Q.; Zhang, J. P.; Liu, Q.; Bi, X. H. Dialkylthio vinylallenes: alkylthio-regulated reactivity and application in the divergent synthesis of pyrroles and thiophenes. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8802–8804.Search in Google Scholar

Fürstner, A. Chemistry and biology of roseophilin and the prodigiosin alkaloids: a survey of the last 2500 years. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2003, 42, 3582–3603.Search in Google Scholar

Fürstner, A.; Szillat, H.; Gabor, B.; Mynott, R. Platinum- and acid-catalyzed enyne metathesis reactions: mechanistic studies and applications to the syntheses of streptorubin B and metacycloprodigiosin. J. Am. Chem. Soc.1998, 120, 8305–8314.Search in Google Scholar

Hazlewood, S. J.; Hughes, G. K.; Lions, F.; Baldick, K. J.; Cornforth, J. W.; Graves, J. N.; Maunsell, J. J.; Wilkinson, T.; Birch, A. J.; Harradence, R. H.; Gilchrist, S. S.; Monaghan, F. H.; Wright, L. E. A. Pyrroles derived from acetonylacetone. J. Proc. R. Soc. New South Wales.1937, 71, 92–102.Search in Google Scholar

Heugebaert, T. S. A.; Roman, B. I.; Stevens, C. V. Synthesis of isoindoles and related iso-condensed heteroaromatic pyrroles. Chem. Soc. Rev.2012, 41, 5626–5640.Search in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, H.; Lindel, T. Synthesis of the pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids. Synthesis2003, 12, 1753–1783.10.1055/s-2003-41005Search in Google Scholar

Jacobi, P. A.; Coutts, L. D.; Guo, J.; Hauck, S. I.; Leung, S. H. New strategies for the synthesis of biologically important tetrapyrroles. The “B, C + D + A” approach to linear tetrapyrroles. J. Org. Chem.2000, 65, 205–213.Search in Google Scholar

Jafari, A. A.; Amini, S.; Tamaddon, F. A green, chemoselective, and efficient protocol for Paal-Knorr pyrrole and bispyrrole synthesis using biodegradable polymeric catalyst PEG-SO3H in water. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2012, 125, 1339–1345.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, H.; Kim, B. H. Indium-mediated one-pot pyrrole synthesis from nitrobenzenes and 1,4-diketones. Tetrahedron2013, 69, 6698–6708.10.1016/j.tet.2013.05.113Search in Google Scholar

Noberini, R.; Koolpe, M.; Peddibhotla, S. Small molecules can selectively inhibit ephrin binding to the ephA4 and ephA2 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 29461–29472.Search in Google Scholar

Ragno, R.; Marshall, G. R.; Santo, R.; Costi, R.; Massa, S.; Rompei, R.; Artico, M. Antimycobacterial pyrroles: synthesis, anti-mycobacterium tuberculosis activity and QSAR studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2000, 8, 1423–1432.Search in Google Scholar

Rahmatpour, A. ZrOCl2·8H2O as a highly efficient, eco-friendly and recyclable Lewis acid catalyst for one-pot synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles under solvent-free conditions at room temperature. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 25, 585–590.Search in Google Scholar

Rahmatpour, A. J. Polystyrene-supported GaCl3 as a highly efficient and recyclable heterogeneous Lewis acid catalyst for one-pot synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles. J. Organomet. Chem.2012, 712, 15–19.Search in Google Scholar

Santo, R.; Costi, R.; Artico, M.; Massa, S.; Lampis, G.; Deidda, D.; Pompei, R. Pyrrolnitrin and related pyrroles endowed with antibacterial activities against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.1998, 8, 2931–2936.Search in Google Scholar

Satyanarayana, V. S. V.; Sivakumar, A. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of 2,5-dimethyl-N-substituted pyrroles catalyzed by uranyl nitrate hexahydrate. Ultrason Sonochem. 2011, 18, 917–922.Search in Google Scholar

Shanthi, G.; Perumal, P. T. InCl3-catalyzed efficient one-pot synthesis of 2-pyrrolo-3′-yloxindoles. Tetrahedron Lett.2009, 50, 3959–3962.Search in Google Scholar

Thomas, R. C.; Poel, T.; Barbachyn, M. R.; Gordeev, M. F.; Luehr, G. W.; Renslo, A.; Singh, U.; Josyula, V. Preparation of 3-aryl-2-oxo-5-oxazolidinecarboxamides and analogs as antibacterial agents. US 20040147760 (141:140424).Search in Google Scholar

Yu, S. X.; Quesne, P. W. L. Quararibea metabolites: total synthesis of (+)-funebral, a rotationally restricted pyrrole alkaloid, using a novel Paal-Knorr reaction. Tetrahedron Lett.1995, 36, 6205–6208.Search in Google Scholar

©2014 by De Gruyter

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Synthesis and structure of an acyclic dialkylstannylene

- Two in one: the bismuth bromido clusters in [Bi6Cp*6Br9][Bi7Br24]

- 2D Hydrogen-bonded polymer assembled by zinc(II) tetraaza macrocyclic complex and 1,2-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid

- An efficient synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles catalyzed by MgI2 etherate

- Synthesis and characterization of N2S2-tin macrocyclic complexes of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II)

- Synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytotoxic activity of bis(triorganotin) 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylates

- Short Communications

- Reactivity of a spirobis(pentagerma[1.1.1]propellane)

- A monoclinic polymorph of 2,6-Mes2 C6 H3 SiF3

- Synthesis and structure of bis(m-terphenyl)zinc (2,6-Mes2 C6 H3)2 Zn

- Synthesis and structure of diarylhalotelluronium hexahalotellurates [(8-Me2 NC10 H6)2 TeX]2 TeX6 (X=Cl, Br)

- Synthesis and structure of three molecular arylindium phosphinates

- Molecular structure of Te2 Mg2(μ3-Cl2)(μ2-Cl4)Cl6(THF)4·CH2 Cl2

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Synthesis and structure of an acyclic dialkylstannylene

- Two in one: the bismuth bromido clusters in [Bi6Cp*6Br9][Bi7Br24]

- 2D Hydrogen-bonded polymer assembled by zinc(II) tetraaza macrocyclic complex and 1,2-cyclopentanedicarboxylic acid

- An efficient synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles catalyzed by MgI2 etherate

- Synthesis and characterization of N2S2-tin macrocyclic complexes of Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II)

- Synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytotoxic activity of bis(triorganotin) 2,6-pyridinedicarboxylates

- Short Communications

- Reactivity of a spirobis(pentagerma[1.1.1]propellane)

- A monoclinic polymorph of 2,6-Mes2 C6 H3 SiF3

- Synthesis and structure of bis(m-terphenyl)zinc (2,6-Mes2 C6 H3)2 Zn

- Synthesis and structure of diarylhalotelluronium hexahalotellurates [(8-Me2 NC10 H6)2 TeX]2 TeX6 (X=Cl, Br)

- Synthesis and structure of three molecular arylindium phosphinates

- Molecular structure of Te2 Mg2(μ3-Cl2)(μ2-Cl4)Cl6(THF)4·CH2 Cl2