Abstract

Dialects of the South American language Mapudungun are claimed to display a dental-alveolar contrast across four manners of consonant articulation: stops, nasals, laterals, and fricatives. Such a full, symmetrical system of distinctions among coronals is typologically unique and, as such, is predicted to be unstable. This paper’s survey of contemporary data, however, shows that, despite lexical contrast being marginal and dentals being morphologically restricted, the distinction is highly salient to native speakers of the more vital dialects. A careful examination of the pattern’s historical roots and diachronic stability, furthermore, allows us to reconstruct it throughout the 400-year textual record. Indeed, the early descriptions and transcriptions shown that, instead of contracting, the contrast expanded, by borrowing the alveolar fricative /s/ from Quechuan and Spanish. The historical and articulatory data shows that while /t̪ n̪ l̪ θ/ are laminal, /t n l/ are apical. Incoming /s/, however, does not follow the pattern, being laminal and prompting a reorganization of featural contrasts among fricatives. As a result of erosion of native fluency under Spanish contact, loss of the dental-alveolar contrast has become commonplace, although there is much variation across speaker, dialect, and manner of articulation. Crucially, dialects which had only voiced fricatives until the borrowing of /s/ seem to have added voicing as a new contrastive feature, helping to preserve the coronal contrast among fricatives, even where vitality is reduced.

1 Introduction

Mapudungun (ISO [arn], unclassified/isolate) is the endangered, ancestral tongue of the Mapuche people of the Southern Cone of the Americas.[1] Before European invasion (ca. 1530), speaker numbers are estimated at around one million (Bengoa 2000: 21). Today, optimistic counts stand at about 250,000 (Eberhard et al. 2020; Zúñiga and Olate 2017). Despite these rough, large figures, proficiency varies widely and transmission has seen a sustained decline (Gundermann et al. 2009), with Spanish-dominant bilingualism the norm, while native education programmes remain incipient and insufficient (Loncon 2017).

Our empirical focus is the typologically unique four-manner (stop, nasal, lateral, fricative) dental-alveolar contrast described in the literature on Mapudungun. In Section 2, I examine the standard account, its typological status, and the lexical and morphological distribution of phonemes. I then survey the 400-year written record (Section 3), in order to assess the stability of the pattern. Particular focus is placed on fricatives, since the contrast between /θ/ and /s/ appears to be an innovation. Section 4 surveys the contemporary dialectal data, showing the different patterns of maintenance and decay. A discussion and formalization of the changes in the contrastive system vis-à-vis contact follows in Section 5, with a particular focus on the features of fricatives. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 Dental-alveolar contrast in Mapudungun

2.1 The standard account

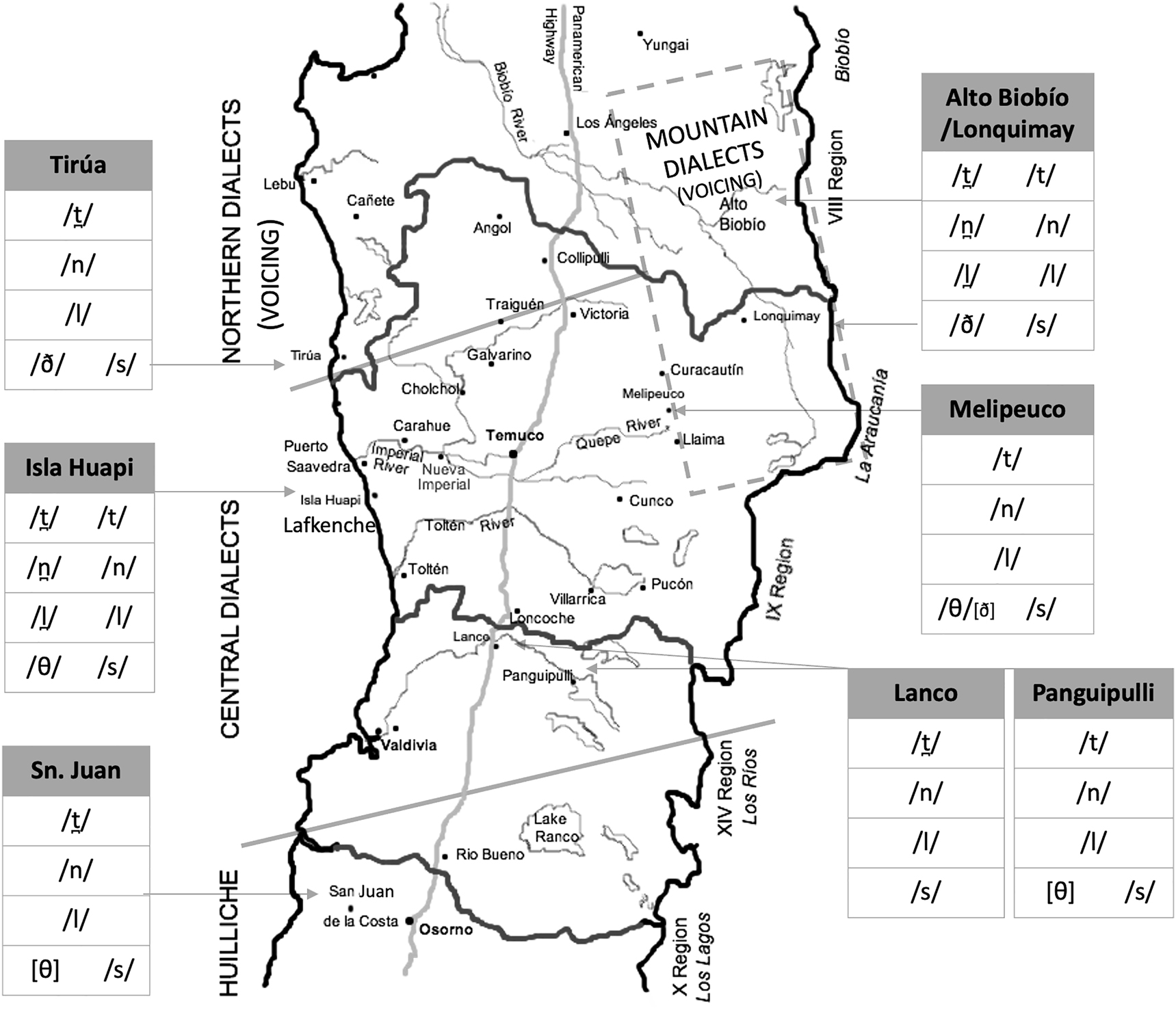

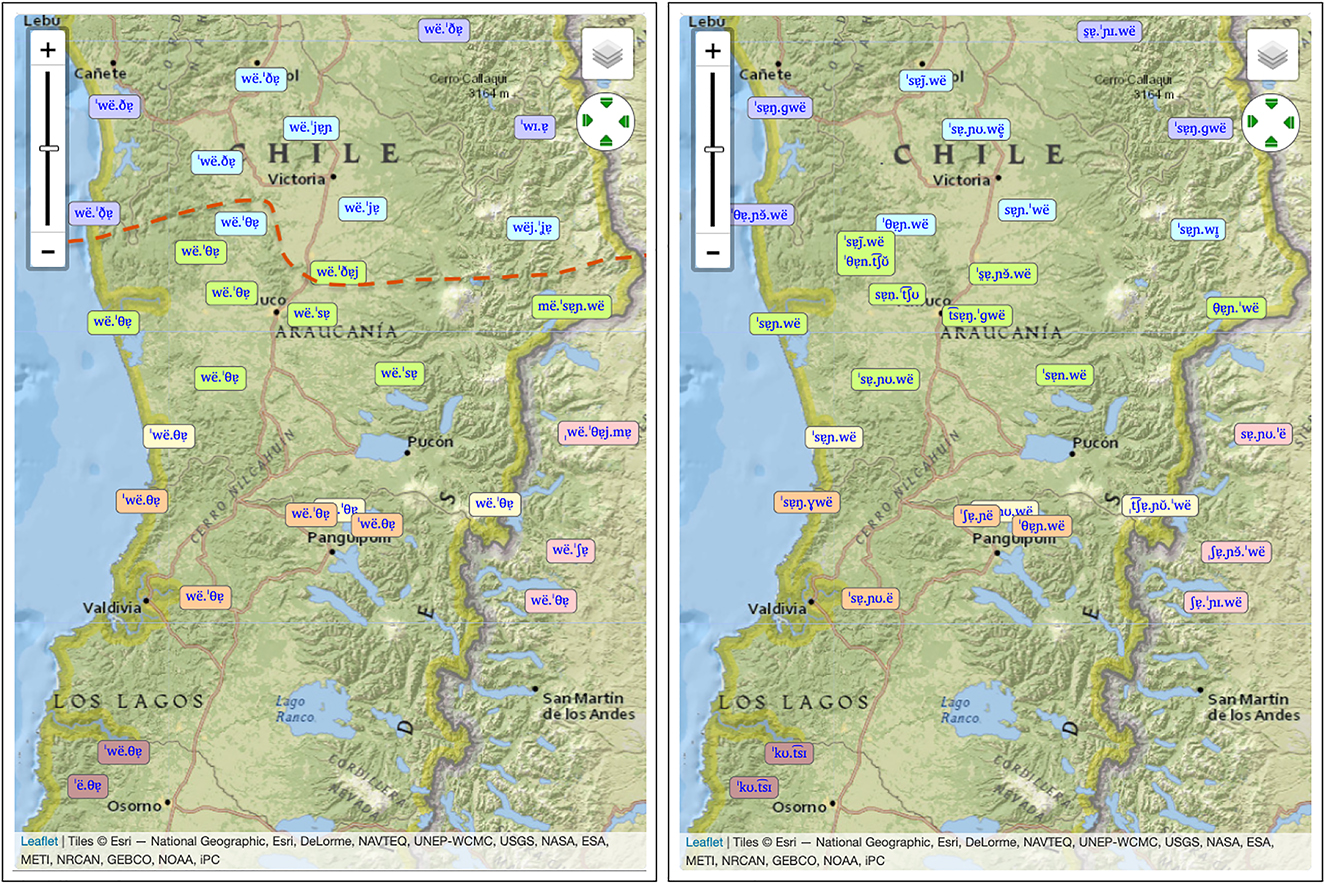

Much of contemporary scholarship on Mapudungun focuses on central varieties, spoken in the western Andean slopes, central valley, and coastal areas of Chile’s Araucanía and Los Ríos regions (see Figure 4). It is on the basis of these dialects that the language is traditionally claimed to display a phonemically contrastive, symmetrical series of (inter)dental and alveolar segments (Echeverría 1964; Echeverría and Contreras 1965; Lagos 1981, 1984; Salas 1976, 1992a; Zúñiga 2006), such as can be observed in Table 1.

Central Mapudungun consonant inventory, based on Sadowsky et al. (2013).

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop/affricate | p | t̪ | t | t͡ʃ | ʈ͡ʂ | k | |

| Fricative | f | θ | s | ʃ | ʐ | ||

| Nasal | m | n̪ | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Lateral | l̪ | l | ʎ | ||||

| Approximant | w | j | ɰ |

While minimal pairs contrasting the two places of articulation do occur for stops, nasals, and laterals (see Table 2), these are somewhat rare, as are dental segments more generally (see Section 2.3). For fricatives, only near-minimal pairs may be found, since the alveolar sibilant (/s/) is mostly restricted to borrowings.

(Near-)minimal dental-alveolar pairs by manner of articulation (from de Augusta 1916; Painequeo et al. 2018).

| Stops | Nasals | Laterals | Fricatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| [t̪ən] ‘head louse’ | [mə.n̪a] ‘cousin’ | [kɨ.l̪a] ‘bamboo’ | [θa.kel] ‘pact/agreement’ |

| [tən] ‘high sound’ | [mə.na] ‘much’ | [kɨ.la] ‘three’ | [sa.ku] ‘sack’(<Spa.‘saco’) |

In their study of the Lafkenche (coastal/central) variety of Isla Huapi (Figure 4), Painequeo et al. (2018) show that most speakers – especially older ones – consistently contrast dental and alveolar stops, nasals and laterals in both production and perception. Particularly, they find speakers tend to reject dental-consonant target words produced with an alveolar segment (e.g. *[tapəl] for [t̪apəl̪] ‘leaf’), claiming they sound “foreign”. Indeed, despite the marginality of lexical contrasts, speakers have strong intuitions about the distinction. This is reflected in community-led orthographic conventions, where native speakers insist on representing the dentals graphemically (see Salas 1992b: 502–503; Zúñiga 2001).

Acoustic evidence for the robustness of the contrast in Lafkenche is given by Fasola et al. (2015) and Figueroa et al. (2019), who observe that, at the onset of adjacent vowels, dentals cause a greater depression in F2 than alveolars.[2] In the same dialect, Sadowsky et al. (2013) use static palatography to capture a more nuanced articulatory picture. The dental series shows apical protrusion throughout, while /t̪, n̪, l̪/ also display broad laminal contact on the upper incisors, consistent with laminal interdental articulations.[3] The alveolars /t, n, l/, show narrow – likely apical – contact on the alveolar ridge. Finally, while /s/ displays some overlap with other fricative categories,[4] it is usually realized as [s̻] with a lamino-alveolar articulation. The resulting pattern, in Table 3, is less symmetrical than what we get from viewing the passive articulator alone.

Active and passive articulators for Mapudungun anterior coronals.

| Apical | Laminal | |

|---|---|---|

| Alveolar | /t, n, l/ | /s/ |

| Interdental | /t̪, n̪, l̪, θ/ |

The general upshot, however, is that – at least for the more vital Lafkenche dialect – Mapudungun does present a discernible phonetic and phonological contrast between the two coronals.

2.2 Typological rarity

Most languages of the world tend to have only one main coronal place of articulation – most frequently alveolar[5] –, the contrast between dentals and alveolars being fairly rare and usually supported by a laminal-apical contrast (see Butcher 2006). Indeed, at the time of consultation, among the 2,100 languages in the PHOIBLE database (Moran and McCloy 2019), only 8.9% of languages contrasted dentals and alveolars among stops, 7.8% among nasals, 4.1% among laterals, and 2.9% among fricatives. The implication is that dental-alveolar contrast is somehow dispreferred, or, in diachronic terms, difficult to develop and/or maintain. With this in mind, Mapudungun – the only language in PHOIBLE with four major manner distinctions for the contrast – is an excellent case study for probing the possibilities of its synchronic and diachronic robustness.

2.3 Lexical and morphological distribution

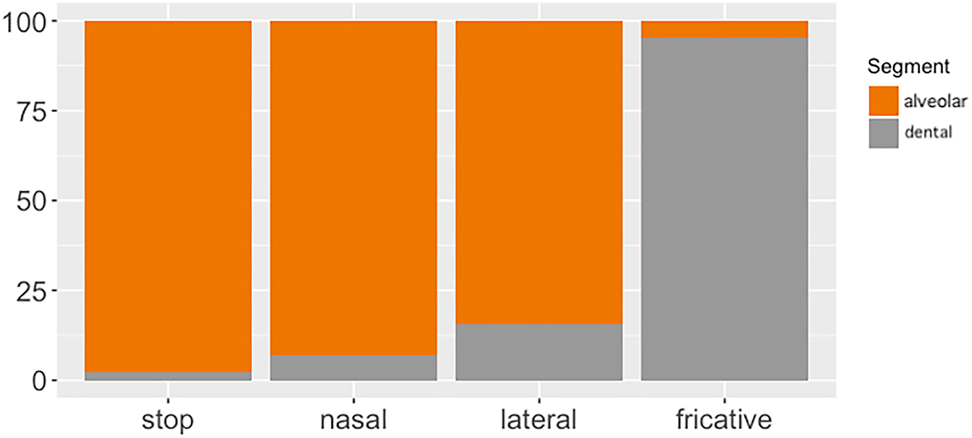

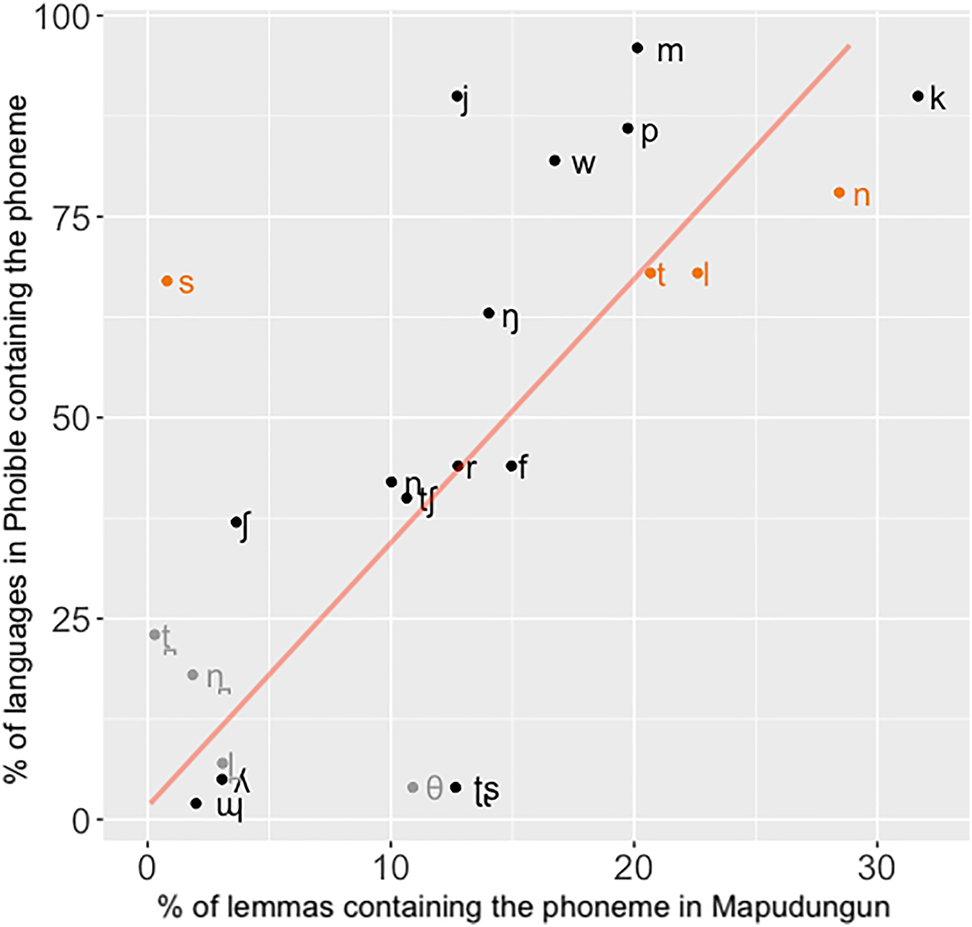

Despite phonological contrasts, there is a definite imbalance between the two coronal series in Mapudungun, such that lexical incidence for the dental stops, nasals, and laterals is far smaller than for the alveolars. In the case of fricatives, however, the opposite pattern obtains, as seen in Figure 1. Just as striking is the fact that, comparing the overall consonant frequencies in Mapudungun to the occurrence of the same consonants across the languages in PHOIBLE, we find that the dental and alveolar fricatives are outliers (see Figure 2). In other words, they violate the strong typological tendency for correspondence between language-internal phoneme frequency and phoneme attestations across the languages of the world (see Gordon 2016: 71–82 for an overview). A further distributional fact about our target segments is that dentals occur only in the root morphemes of the language, while the alveolars – excepting /s/ – are found across the board, in inflectional and derivational elements as well. This pattern suggests that dentals (and /s/) belong to open-class categories only and may have either been recently innovated in roots or lost in suffixes due to their greater markedness (see Bybee 2005).

Proportion of lexical items with alveolar versus dental segments, based on the 5,125 dictionary entries in de Augusta (1916).

Lexical incidence of Mapudungun phonemes (in de Augusta 1916) versus their attestation in languages of the world (the 2,100 languages in PHOIBLE).

3 Historical evidence for dental-alveolar contrast

As one of the “general languages” used by colonists for evangelization and diplomacy across the Americas, Mapudungun has a relatively substantial early textual history. Using data from the Corpus of Historical Mapudungun (Molineaux and Karaiskos 2021), I will show that European missionaries, explorers, and linguists were able to observe the dental-alveolar contrasts throughout the 400-year record and were often at pains to provide suitable descriptions. That being said, early sources vary in their quality, interpretability, and regional coverage. This is further complicated by early writing rarely being conducted by native speakers, so there are different phonologies, as well as spelling systems, at play in each source.

3.1 The sixteenth-century evidence: Luys de Valdivia (1606, 1621

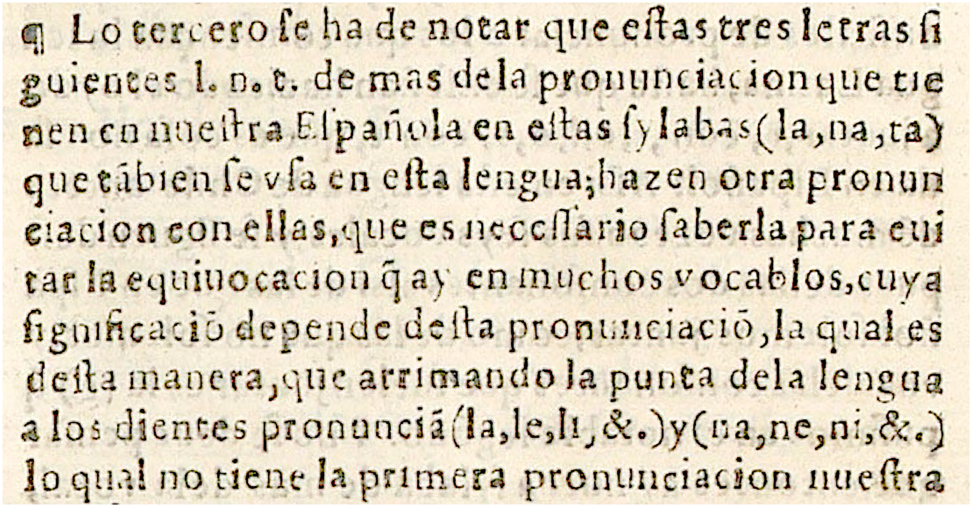

Father Luys de Valdivia was part of the first group of Spanish Jesuits to work with the Mapuche in the Mission of Chile. His Art and grammar of Mapudungun, published in 1606, is the earliest printed, surviving grammar and vocabulary of the language. In describing the language’s pronunciation, we find the following claim (Figure 3):[6]

these three letters l, n, t, aside from the pronunciation they have in our Spanish syllables [la, na, ta] have another pronunciation in this language which should be known in order to avoid mistakes, since the meaning of many words depends on this pronunciation, which is thus: that nearing the tip of the tongue to the teeth, they pronounce [la, le, li, etc.] and [na, ne, ni, etc.], which is different from our first pronunciation.

Valdivia’s description of dentals in seventeenth-century Mapudungun.

Dentals and alveolars across Mapudungun dialects (major areas follow Croese 1980).

Given that Spanish coronal nasals and laterals were alveolar at the time (Penny 2002: Section 2), there is good reason to believe that the given contrast is between “our Spanish” alveolars (<l, n>)[7] and the “different” dentals (<ľ, n̍>). For stops, however, the situation is less straightforward. Indeed, “our” coronal stops in seventeenth-century Spanish were probably dental (Penny 2002: Section 2), while Valdivia tells us that Mapuche speakers have a “different” <t̄> for which “they shift the tip of the tongue towards the high palate” (8r).[8] Since the words spelled with <t̄> in Valdivia’s vocabulary match the present-day retroflex affricate (/ʈ͡ʂ/) set, we suggest that the contrast was between alveolar and retroflex stops (affrication probably developed not long afterwards). The lexical set which today corresponds to the dental stops, however, shows no graphemic contrast with alveolars, both being spelled <t> (Table 4).

Words with <l, n, t> versus <ľ, n̍, t̄> spellings in de Valdivia (1606).

| Grapheme | Entry in Valdivia’s vocabulary | Phoneme | Present-day reflex | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <l> |

|

lamuen | ‘sister’ | /l/ | /lamwen/ |

| <ľ> |

|

ľan | ‘death’ | /l̪/ | /l̪an/ |

| <n> |

|

non | ‘win’ | /n/ | /non/ |

| <n̍> |

|

n̍oyn | ‘eat too much’ | /n̪/ | /n̪ojn/ |

| <t> |

|

tica | ‘adobe’ | /t/ | /tika/ |

| <t̄> |

|

t̄ecan | ‘walk’ | /ʈ/ | /ʈ͡ʂekan/ |

| <t> |

|

tue | ‘earth’ | /t̪/? | /t̪ue/ |

Coronal fricatives are not explicitly treated in de Valdivia (1606), however, the lexical set which today contains a dental fricative is consistently spelled with <d>, as in dihuen ‘companion’ (Table 5). This is roughly in line with the intervocalic, fricative allophone of seventeenth-century Spanish voiced dental stops (with e.g. <d> being produced as [ð] in ca[ð]a ‘each’ and [d̪] in [d̪]ios ‘god’; Harris-Northall 1990). The implication, is that the dental fricative was voiced, as were all fricatives in Valdivia’s dialect, given the spellings in Table 5. As we shall see in Section 5.2, this is an important isogloss in Mapudungun today, where fricatives tend to be voiced in the northern varieties and voiceless in the central and southern ones (see Figures 4 and 5). Stops, on the other hand, are always voiceless, so voiced stops borrowed from Spanish are voiceless in Mapudungun (e.g. toninco < domingo ‘Sunday’; Herckmans 1907[1643]). This supports the idea that Valdivia’s <d> is not a stop, but a voiced dental fricative.

Voiced fricatives in seventeenth-century Mapudungun.

| Grapheme | IPA | Entry in Valdivia’s vocabulary | Gloss | Modern prounciation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <d> | ð | dùgu | ‘word/thing’ | θɨŋu |

| <v> | v/β | voru | ‘bone/tooth’ | foʐo |

| <r> | ʐ | raù | ‘clay’ | ʐaɰ |

Pronunciations of weda ‘bad’ (left, fricative voicing isogloss superimposed) and sañwe ‘pig’ (right, from Spanish saín ‘animal fat’ + the instrumental suffix -we), in the sounds comparisons: Mapudungun database.

The picture for the alveolar fricatives is less clear. Spellings in the lexical sets for /s/ include <ç>, <z>, and <s>, but these are rare and appear almost exclusively in words of Spanish or Quechuan (ISO [qwe]) origin.[9] The Spanish words – mostly related to Christian doctrine (Table 6) – suggest no phonological incorporation, preserving their original spellings. Quechuan words are likely older, originating in the languages of the Incan Empire, which expanded into central Chile in the 1470s. These borrowings display phonological and morphological integration, however they seem to preserve the alveolar fricative, otherwise absent from the Mapudungun inventory. A full list of the <ç/z/s> Quechuan borrowings is given in Table 6, where the reference forms from Cusco Quechua (ISO [quz]) are taken from Middendorf (1890); for further details, see Moulian et al. (2015) and Sánchez (2020).[10]

Words with < ç>, <z>, or <s> spellings in de Valdivia (1606, 1621.

| Grapheme | Spelling | Gloss | Source | Spelling | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <ç> | esperança | ‘hope’ | Spanish | esperança | ‘hope’ |

| <ç> | çuyçuyhue | ‘sieve (n.)’ | Quechuan | suisuy | ‘sieve (v.)’ |

| <ç> | ç acin | ‘fast (v.)’ | Quechuan | sasiy | ‘fast (v.)’ |

| <z> | caliz | ‘cup’ | Spanish | cáliz | ‘cup’ |

| <z> | mizquilcan | ‘sweeten’ | Quechuan | misk’i | ‘sweet’ |

| <z> | ezñacan | ‘curse’ | Quechuan | ñakay | ‘damn’ |

| <z> | pizcoytu | ‘tops (game)’ | Quechuan | P’iskoinu | ‘tops (game)’ |

| <z> | pozco | ‘yeast’ | Quechuan | P’osko | ‘sour/bitter’ |

| <s> | Dios | ‘God’ | Spanish | Dios | ‘God’ |

| <s> | ñampas clelu | ‘hollow thing’ | Quechuan | ñan-pas | ‘road-other’ |

Although from Granada, Valdivia was educated in Salamanca in the late sixteenth century, so would likely have been exposed to Castilian dialects where <ç/z> represented denti-alveolar [s̪] and <s> represented apico-alveolar /s̪/ (Sanz-Sánchez 2019). These are likely the target values for the Spanish non-incorporated words. In the Quechuan borrowings, the tendency is for <ç/z> spellings, which indicates that Valdivia probably perceived them to be distinct from Spanish apico-alveolar [s̪]. In all likelihood, <ç/z> spellings represented a laminal articulation of the sibilant ([s̻]). This, however, was probably still not fully integrated into Mapudungun phonology, and ultimately did not merge with the native dental.[11] Eventually, integrated Spanish borrowings with a sibilant would have joined this category too, since the dominant New World Spanish (seseo) varieties would have also had a lamino-alveolar [s̻].

3.2 The eighteenth-century evidence

From the next century, two Jesuit grammars survive: one by Febrés (1765), a Catalan, and one by Havestadt (1777), a German. In both cases, descriptions of the sound system are cursory. Febrés mentions, however, that “in some words, they pronounce l and n nearing the tip of the tongue to the teeth” (5),[12] but he decides not to transcribe this, as he considers the difference almost imperceptible and lexically rare. Havestadt fails to mention dentals altogether, providing no special marking. This is surprising, given that both missionaries were stationed in areas where northern dialects were spoken (Angol and Nascimiento, respectively), which we would otherwise expect to be similar to those described by Valdivia. Given Febrés’s comments, it is likely that, due to its low functional load, the place distinction of non-fricative dentals and alveolars was ignored in favour of the more Spanish-like phones [l, n, t̪]. The only exception to this pattern is the occasional use of <ld> in words with /l̪/ reflexes (e.g. pelde for [pel̪e] ‘mud’) which probably represents the lateral with the dental articulation of Spanish coronal stops.

Both Febrés and Havestadt use <d> to represent the voiced dental fricative (/ð/), as did their predecessor. This is in line with other fricatives, such as <v>, which Febrés claims to sound as in Spanish or Catalan ([β/b/v]) for northern Mapuche. Further to the south, however, he tells us it is pronounced “a bit stronger, much like F, in the way that Germans pronounce it in the Latin words parvulus or vita” (5),[13] which is to say, voiceless.

The grammars include lexical lists that use the grapheme <s>. The familiar Quechuan words, such as misqui ‘sweet’ crop up,[14] but now there is a wider set of integrated Spanish borrowings, such as <awas> ‘faba/broad bean’ from habas ‘faba/broad beans’ or <mansun> ‘ox’ from manso ‘tame’, probably taken from seseo varieties of Spanish (with one anterior sibilant) and representing [s̻]. Despite this integration,[15] it seems that /s/ does not join the voicing pattern of the other fricatives, which are voiced.

An independent source for the dialectal details of the dental-alveolar contrast can be found in Thomas Falkner’s A description of Patagonia (1774). The Mancunian surgeon-turned-Jesuit gives a brief overview of central Mapudungun. Words that elsewhere have a <d> are spelled with either an <s> or a <z>. He appears to use Spanish, rather than English grapho-phonemic correspondences,[16] so <z> is likely a voiceless sound representing either Castilian /θ/ or New World /s/. All fricatives, crucially, appear to be voiceless in this area, as evidenced in Table 7.

Fricatives in northern (N) and central (C) eighteenth-century Mapudungun sources.

| Febrés (N) | Havestadt (N) | Falkner (C) | Contemporary (C) | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ad | ad | az | /aθ/ | ‘face’ |

| dùgu | dngu | sengu | /θɨŋu | ‘word, idea, thing’ |

| mansun | mansun | (Dios) | /mansun/ | ‘ox’ |

| avùln | avuln | afeln | /afelɨn/ | ‘be averse/destroy’ |

| cura | cura | cusa | /kuʐa/ | ‘stone’ |

3.3 The nineteenth century and beyond

In the late nineteenth century, the German-born linguist Rudolf Lenz compiled the first scientifically oriented collection of Mapuche stories and dialectal samples (Lenz 1897). Prompted by his main consultant, Calvún (Segundo Jara), he was also first to recognize the full set of dental-alveolar contrasts (including [t]-[t̪]). He recalls how Calvún would patiently turn to him when pronouncing the key sounds: “to show me the tip of his tongue as it protruded between his teeth” (1897: 130),[17] which he eventually understood to be systematic. Lenz also identifies the dental fricative (68), using <d> for realizations with voicing, and <z> for voiceless ones (i.e. “the Castilian <z> of some northern dialects of Spain”; p. 7). As for <s>, he uses the symbol only in words of Spanish or Quechuan descent, representing /s/ (69).

The last of the major missionary grammars was published in 1903 by another German, the Franciscan Félix de Augusta. As in de Valdivia (1606), three dental-alveolar contrasts are proposed: nasals, laterals, and fricatives. Only when he composed his Dictionary (1916) did Augusta decide to use the grapheme <t·> to represent dental stops. Again, the decision was prompted by an explicit recommendation by one of his main consultants, Domingo Segundo Huenuñamco of Panguipulli (1916: xiv). The grapheme <d>, Augusta claims, sounds like Spanish d or English th (1910: x), which by now would have contrasted with alveolar <s>, pronounced “as in Spanish” (i.e. /s/).

Ultimately, then, we find that both Lenz and Augusta, albeit later in their studies of the language, observe the distribution of dentals and alveolars as in the standard system of Table 1. This is true for both the northern and central dialects they describe, although the dental fricative is voiced in the north.

4 Dentals versus alveolars in contemporary dialects

In what follows, I give a brief overview of the available data for dialects of Mapudungun today, summarized in Figure 4.

4.1 Voiceless fricative dialects: central and southern

The fully contrastive system in Section 2.1 corresponds to the Isla Huapi dialect, a central, coastal variety (Lafkenche). Here, Sadowsky et al. (2013) and Painequeo et al. (2018) carefully selected community members for their proficiency, being L1 Mapudungun bilinguals who still used the language regularly. This yielded clear phonological and phonetic differences between the voiceless dental and alveolar categories across manners of articulation.[18]

Looking further afield, we find a less clear-cut pattern. Indeed, describing the dialect of Melipeuco, in the Andean foothills, Salamanca et al. (2009) find that laterals and nasals are in free variation across dental and alveolar realizations, the latter dominating even in the dental lexical sets. Stops, however, are exclusively alveolar.[19] Among fricatives, alveolar /s/ and dental /θ/ contrast, with the latter alternating freely between voiceless [θ] and voiced [ð] in line with other fricatives ([f]∼[v]; [ʂ]∼[ʐ]). This shows the area to be near the voicing/voiceless fricative isogloss.

For the south-central dialects of Lanco and Panguipulli, Alvarez-Santullano (2016) reports speakers merging nasals and laterals on the alveolar, while the stops merge on the dental in Lanco and alveolar in Panguipulli, though alternations are rampant. Fricatives are consistently voiceless and, for the single Lanco consultant, /θ/ and /s/ have merged on the alveolar, while for the Panguipulli speaker the same process is nearing completion.

The southernmost dialect, known as Huilliche, is described by Sadowsky et al. (2015) for San Juan de la Costa. As in the Lanco dialect, stops have merged on the dental, while nasals and laterals do so on the alveolar.[20] For fricatives, which are voiceless ([f-ɸ-x], [θ-s-h], [ʂ]), the dental set is often realized as alveolar, but not vice versa. As a result, a merger towards /s/ is nearing completion.

4.2 Voiced fricative dialects: northern and mountain

The coastal variety of Tirúa is shown by Salamanca and Quintrileo (2009) to have mostly lost the target contrast for non-fricatives (though some variation remains). Fricatives are predominantly voiced ([v-β], [ð], [ʐ]), except for /s/, which contrasts with /ð/.[21]

For the Alto Biobío mountain varieties (Pehuenche), the phonemic status of dentals is debated. Sánchez (1989: 293) rejects their contrastiveness while Salamanca (1997) finds contrast among stops, nasals and laterals. Salamanca et al. (2017) revisit the issue, with a larger data set including palatogram, audio, and video evidence, concluding that competent speakers consistently use dentals in the relevant lexical sets. However, among young, mobile speakers, different degrees of free variation between dentals and alveolars are evident. As with the Tirúa dialect, fricatives are consistently voiced, excepting /s/, which contrasts with /ð/. This same pattern is found in the other described Pehuenche area, Lonquimay (Sánchez and Salamanca 2015).

4.3 The sounds comparisons evidence

The wealth of phonetic and phonological studies on our target contrast is surprising for a South American language. However, the methodologies and transparency of data vary widely, making comparisons difficult. Here, the Sounds Comparisons project for Mapudungun (SCM; Sadowsky et al. 2019) gives some perspective, providing more homogeneously gathered, accessible data in the form of audio and IPA-transcribed speaker samples for 224 lexical items across 38 locations in Chile and Argentina.

A quick look at the distribution of dentals versus alveolars in key words for stops (füt’a ‘husband’ vs. pütokon ‘drink water’), nasals (wen’üy ‘friend’ vs. tranan ‘mash’) and laterals (l’an ‘die’ vs. lamngen ‘sister’) shows a striking pattern where only the Lafkenche items display the contrast, while elsewhere only the sounds that match the Spanish phoneme are evidenced. The reasons behind the discrepancies between the localized studies and the SCM are not altogether clear, but are likely to be attributable to the selectiveness of consultant sampling in the former.

For the fricatives (see Figure 5), however, the contrast seems much more robust across the SCM data, even if occasional overlap of categories occurs, particularly in southern and eastern dialects. Reassuringly, the fricative voicing isogloss is clearly observable.

5 Changes in the dental-alveolar contrast

5.1 Contact and the development of new contrast

Throughout our 400-year survey, we have seen that the dental-alveolar contrast consistently rears its head in the more careful descriptions and transcriptions. This is certainly the case for /n̪/–/n/ and /l̪/–/l/, highlighted already by de Valdivia (1606). Contrast in stops is not explicitly observed until almost three centuries later, by Lenz (1897), yet it is unlikely to have emerged in that period, as we find some evidence – at least residual – for equivalent lexical sets across most contemporary dialect areas. The difficulty in perceiving this contrast is probably the result of the lexically rarer variant, /t̪/, being expected for L1 Spanish descriptions. Indeed, the first observations of the contrastive nature of /t/–/t̪/ are only made when native speaker judgements are taken seriously (see Section 3.3).

By analysing the graphemic repertoires of early missionaries we reconstructed the antecedent of present-day /θ/ as /ð/; a phoneme we assume to be native to the language (albeit circumscribed to root morphology, see Section 2.3). /s/, we further ascertained, emerged as a result of contact, first with Quechuan and then with Spanish. While the early recorded borrowings are few, the typological frequency of /s/ across the languages of the world (67% of PHOIBLE inventories) suggests its relative unmarkedness, and hence its ease of adoption. Placing /s/ in the otherwise symmetrical dental-alveolar system, furthermore, would have been a fairly economical change (Clements 2003). The key featural distinction between dentals and alveolars among stops, nasals, and laterals, however, seem to fail to produce the right contrast for the dentals. Indeed, dental-alveolar contrasts have long been argued to be fundamentally characterized by laminal ([+distributed]) versus apical ([–distributed])] features (Chomsky and Halle 1968; Clements 2009; Rice 2011), a pattern that does not obtain among present-day Mapungun fricatives, which are both laminal (Table 3).

The phonetic details of Spanish sibilant adaptations into Mapudungun also underscore this pattern. Indeed, while most of these borrowings show historical <s> spellings and contemporary [s̻] pronunciations (Table 7), some early Spanish <s> loans are spelled with <ch> and are still often pronounced [t͡ʃ] (Febrés 1765: <chiñur> ‘Spaniard’ < señor). This reflects the early heterogeneity of Spanish dialects coming into contact with the Native American languages. The first group of borrowings are likely to originate in southern Peninsular seseo varieties with a single sibilant phoneme (laminal [s̻]=<s>), while the latter probably come from distinción dialects such as Castilian, which distinguish [s̪] and [s̪] (<ç/z> and <s>). Crucially, apico-alveolar [s̪] was likely perceptually and featurally closer to the Mapudungun voiceless postalveolar affricate /t͡ʃ/ = <ch>, than to the voiced dental fricative /ð/ = <d>(Hasler and Soto 2012: 98) or, indeed, to the incoming laminal [s̻]. The population, power, and lexical dynamics that led to borrowings coming from one dialect or another are unclear (see Sanz-Sánchez [2019] for a pan-American view). However, the pattern gives further evidence that <s> was never apical in Mapudungun, but must have eventually contrasted with /θ/ via a different feature than the other dental-alveolar pairs. A well-established candidate for this role is [±strident] (cf. Kim et al. 2015), as given in Table 8.

Proposed features for key Mapudungun coronals.

| Distributed | Strident | Anterior | |

|---|---|---|---|

| /t n l/ | − | − | + |

| /t̪ n̪ l̪ θ/ | + | − | + |

| /s/ | + | + | + |

| /t͡ʃ/ | − | + | − |

While there were other strident phones in pre-contact Mapudungun, the feature [strident] was not key to any phonemic contrasts. If we take features to be specified in a language only if they are contrastive (as in Modified Contrastive Specification; see Dresher 2009; Hall 2011), the feature [+strident] in /t͡ʃ/ is redundant because Mapudungun has no other affricates with the specification [−distributed, −anterior]. However, the adoption of /s/ meant that [strident] must have become specified in the contrastive system of Mapudungun. This innovation is particularly interesting in that it involves a far less economical change to the language’s contrastive system than adapting Spanish /s/ to fit the apical series.

5.2 Fricative voicing: diatopy and diachrony

Compared to the languages of Africa and Eurasia, the Americas—and the Southern Cone in particular—make little use of voicing contrasts (see the WALS data in Maddieson 2013). Historically, Mapudungun lacks obstruent voicing altogether, with the quirky distributional fact that fricatives in northern dialects are, by default, voiced, while in central and south dialects they are voiceless. Here, I have observed that the isogloss separating these varieties must precede the written record. In the northern, voiced-fricative dialects, however, the eventual phonemicization of /s/ would have created a less predictable voicing pattern. This new contrast, I will argue next, is likely to have played a role in the preservation of both members of the dental-alveolar fricative pair, despite ongoing language marginalization and loss of vitality.

5.3 Loss of contrast

Mapudungun is in the process of losing the dental-alveolar contrast. Yet this development is not uniform across dialects, speakers, and manners of articulation. Polar extremes are seen in the Isla Huapi variety, where competent speakers seem to preserve a robust four-manner contrast, and in the Huilliche variety, where the few remaining speakers have almost completely merged the dental-alveolar pairs across all four manners, always in favour of the sound matching the Spanish phoneme. These two poles also mirror the loss of fluency and reduced transmission in said communities. Detailed comparative data for the vitality of Mapudungun dialects is limited, yet we can ascertain that central Lafkenche varieties are at once remote and vital, with cultural and oral literature traditions very much alive (Painequeo et al. 2018). Huilliche, on the other hand, is spoken by a very small number of elders and has long been identified as moribund (Alvarez-Santullano 1992; Sadowsky et al. 2015).[22]

Among central dialects, Melipeuco, Panguipulli, and Lanco varieties show loss of the dental-alveolar contrast in stops, nasals, and laterals. While Melipeuco speakers preserve the fricative contrast, Panguipulli speakers appear to be in the process of merging them (on /s/), a process that is complete in Lanco. The reports in the relevant descriptions highlight changes to the communities’ linguistic makeup as a result of increased contact with major urban settlements (Melipeuco, near Temuco) and greater mobility (the Panamerican highway cross-sects Lanco).

Mountain dialects are recognizably well preserved, due to their remoteness (Gundermann et al. 2011). Here, dental-alveolar contrast is maintained throughout (Salamanca et al. 2017). In northern coastal varieties (Tirúa, Los Álamos), however, vitality is lower and interaction with non-indigenous society, more intense (Gundermann et al. 2011). Unsurprisingly, robust contrast persists only among fricatives (Salamanca and Quintrileo 2009; Saldivia and Salamanca 2020).

Beyond the clear correspondence between vitality and contrast, we see greater degrees of contrast-maintenance among fricatives. This subcategory is not only distinct in being the most recently developed dental-alveolar pair, it is also set apart by articulatory detail (Section 2.1), frequency patterns (Section 2.3), and featural specifications (Section 5.1). A closer look at diatopy, however, suggests that contrast-preservation is also related to the fricative voicing patterns. Where fricatives are voiceless and other dental-alveolar contrasts are lost, the tendency is for loss of contrast among fricatives too (see Lanco, Panguipulli, and San Juan). Where fricatives are historically voiced (northern and mountain dialects), we see that it is possible for these to preserve the dental-alveolar contrast, despite its loss among stops, nasals, and laterals. We see this to be the case in Tirúa and, to the extent that fricatives alternate voicing in Melipeuco, we see it there too.[23]

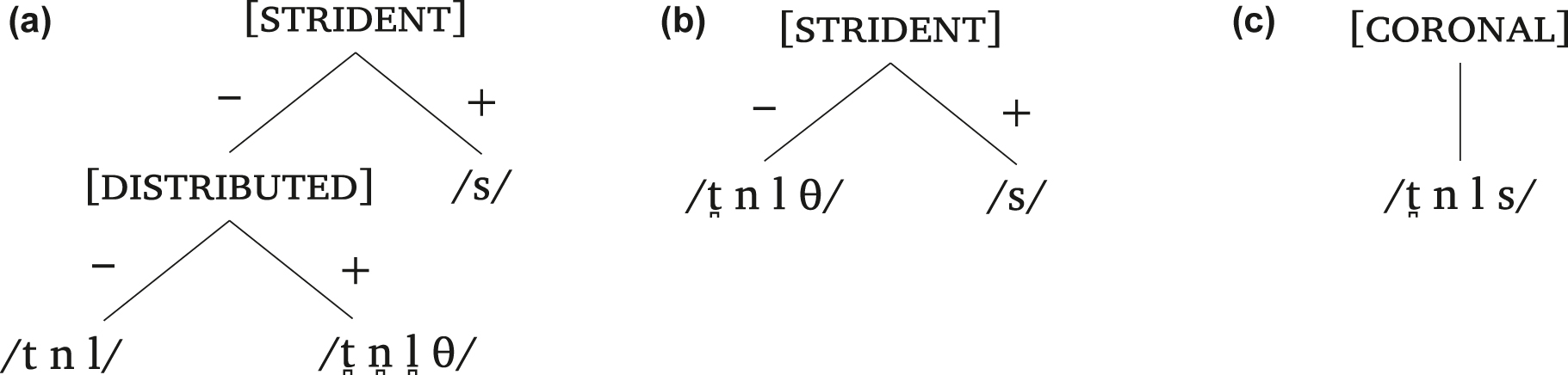

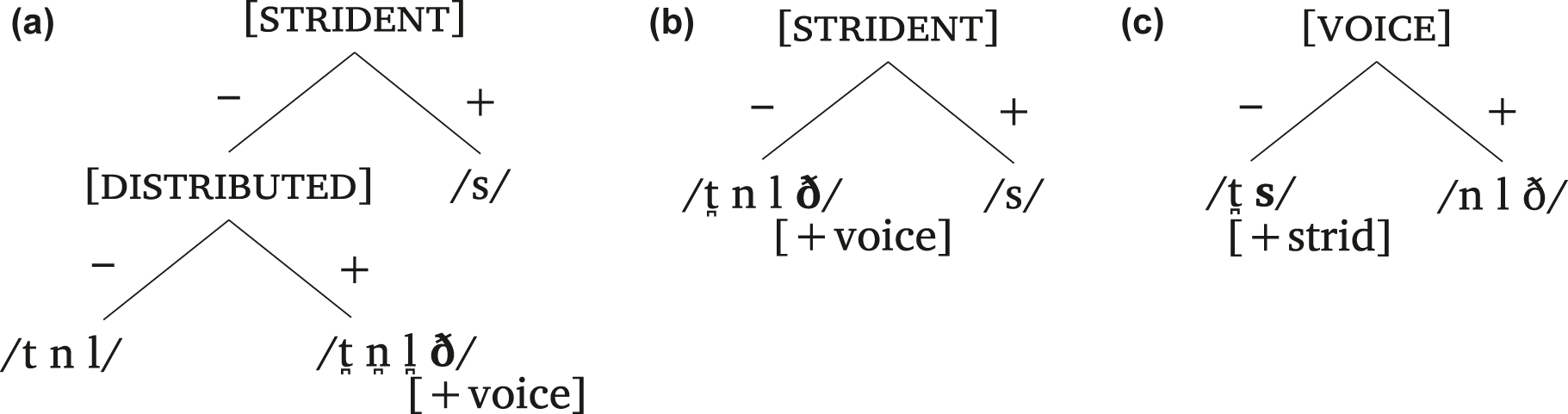

The available data, therefore, suggests that among the northern, voiced-fricative varieties, the dental-alveolar contrast is supported by a voicing contrast. That is, the salience of the voicing contrast amongst increasingly Spanish-dominant speakers is likely to facilitate the maintenance of the dental contrast in fricatives. From a featural perspective (in Modified Contrastive Specification), we may formalize the change as follows. In voiceless dialects, [± distributed] is being removed from the bottom of the feature hierarchy (Figure 6a–b), closely followed by [± strident] (Figure 6b–c). In voicing dialects [± voice] – heretofore a redundant, enhancement feature – has become specified for fricatives, maintaining the key contrast (Figure 7a–c).

Proposed stages of feature-specification loss in voiceless fricative dialects of Mapudungun.

Proposed stages of feature-specification re-ranking in voiced fricative dialects of Mapudungun.

6 Conclusions

The Mapudungun data presented here points to the fact that, while typologically fairly rare, the dental-alveolar contrast can be maintained and even expanded over time in contexts of linguistic vitality, even with no significant areal support and substantial imbalance in frequency. In cases of loss of linguistic vitality, nonetheless, the contrast tends to quickly disappear unless additional features can be relied upon for its maintenance. Under the asymmetric contact conditions of Mapudungun vis-à-vis Spanish, many dialects have followed this path to contrast loss.

Upon closer inspection, however, not all dental-alveolar contrasts are equivalent. Indeed, the fricative pair differs from the stops, nasals, and laterals not only by virtue of being newly developed, but also in lacking a laminal-apical distinction. From a typological perspective, this is interesting, given that other languages that extensively exploit the lamino-dental versus apico-alveolar contrast, either lack fricatives altogether (e.g. Australian languages; see Fletcher and Butcher 2014) or do not exploit the contrast amongst them (e.g. Dravidian languages; see Arsenault 2012).

I have shown that, despite the theoretical possibility of joining a well-established laminal-apical contrastive system, the /s/ phoneme fails to do so. As a result, there is no evidence for the integration of fricatives into such an “economical” system. Whether this is the result of pressures emerging from contact conditions, or from structural constraints alone, remains impossible to determine. The new phoneme, /s/, has brought with it, furthermore, a new voicing contrast in the northernmost dialects, which enhances the dental-alveolar opposition, further dispensing with the laminal-apical contrast. At bottom, the integration of this new, unmarked segment is a contact-induced change, but one with Trojan horse-like consequences for the language’s overarching system of contrasts.

Finally, I hope to have shown that detailed examination of the historical record, as well as close dialectal comparisons (which take native speaker intuitions seriously) are key tools for allowing us to turn back the sands of time and view what Indigenous American languages have gained and lost.

Funding source: The Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship

Award Identifier / Grant number: [ECF 2017-057]

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Gastón Salamanca, Scott Sadowsky, and two anonymous reviewers for their extremely useful comments. I would also like to thank my Mapudungun kimelfe ‘teacher’, Fresia Loncón Antileo, for her generosity helping me develop a broader, practical understanding of her native tongue. Errors of fact and interpretation are, of course, my own. This work was supported by a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship (ECF 2017-057).

References

Alvarez-Santullano, María Pilar. 1992. Variedad interna y deterioro del dialécto huilliche. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 30. 61–74.Suche in Google Scholar

Alvarez-Santullano, María Pilar. 2016. Descripción fonético-fonológica del sistema consonàntico del mapuche hablado en territorio huilliche en los albores del siglo XXI: A propósito de la noción de continuum. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 54(1). 101–127. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48832016000100006.Suche in Google Scholar

Arsenault, Paul. 2012. Retroflex consonant harmony in South Asia. Toronto: Department of Linguistics, University of Toronto Dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

de Augusta, Félix José. 1903. Gramática araucana. Valdivia: Imprenta Central J. Lampert.Suche in Google Scholar

de Augusta, Félix José. 1910. Lecturas araucanas. Padre Las Casas: Editorial San Francisco.Suche in Google Scholar

de Augusta, Félix José. 1916. Diccionario araucano-español y español-araucano. Santiago: Imprenta Universitaria.Suche in Google Scholar

Bengoa, José. 2000. Historia del pueblo mapuche (siglos XIX y XX). Santiago: Lom Ediciones.Suche in Google Scholar

Butcher, Andrew. 2006. Australian aboriginal languages: Consonant-salient phonologies and the “place-of-articulation imperative”. In Jonathan Harrington & Marija Tabain (eds.), Speech production: Models, phonetic processes, and techniques, 187–210. New York, NY: Psychology Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan. 2005. Restrictions on phonemes in affixes. A crosslinguistic test of a popular hypothesis. Linguistic Typology 9. 165–222. https://doi.org/10.1515/lity.2005.9.2.165.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam & Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. New York, NY: Harper and Row.Suche in Google Scholar

Clements, George Nicholas. 2003. Feature economy in sound systems. Phonology 20(3). 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1017/s095267570400003x.Suche in Google Scholar

Clements, George Nicholas. 2009. The role of features in phonological inventories. In Eric Raimy & Charles E. Cairns (eds.), Contemporary views on architecture and representations in phonology, 19–68. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/9780262182706.003.0002Suche in Google Scholar

Croese, Robert. 1980. Estudio dialectológico del mapuche. Estudios Filológicos 15. 7–38.Suche in Google Scholar

Dresher, B. Elan. 2009. The contrastive hierarchy in phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511642005Suche in Google Scholar

Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons & Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2020. Ethnologue: Languages of the world, 23rd edn. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Available at: http://www.ethnologue.com.Suche in Google Scholar

Echeverría, Sergio Max. 1964. Descripción fonológica del mapuche actual. Boletín del Instituto de Filología de la Universidad de Chile 25. 13–59.Suche in Google Scholar

Echeverría, Sergio Max & Heles Contreras. 1965. Araucanian phonemics. International Journal of American Linguistics 31(2). 132–135.10.1086/464825Suche in Google Scholar

Falkner, Thomas. 1774. A description of patagonia. Hereford: C. Pugh.Suche in Google Scholar

Fasola, Carlos, Héctor Painequeo, Senghun Lee & Jeremy Perkins. 2015. Acoustic properties of the dental versus alveolar contrast in Mapudungun. In The Scottish Consortium for ICPhS 2015 (ed.), Proceedings of the 18th international congress on phonetic science, 1–5. Glasgow: The University of Glasgow.Suche in Google Scholar

Febrés, Andrés. 1765. Arte de la lengua general del Reyno de Chile. Lima: Calle de la Encarnación.Suche in Google Scholar

Figueroa, Mauricio, Héctor Painequeo, Camila Márquez, Gastón Salamanca & David Bertín. 2019. Evidencia del contraste interdental/alveolar en el mapudungun hablado en la costa: Un estudio acústico estadístico. Onomazein 44. 191–216. https://doi.org/10.7764/onomazein.44.09.Suche in Google Scholar

Fletcher, Janet & Andrew Butcher. 2014. Sound patterns of Australian languages. In Harold Koch & Rachel Nordlinger (eds.), The languages and linguistics of Australia: A comprehensive guide, 91–138. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110279771.91Suche in Google Scholar

Gordon, Matthew. 2016. Phonological typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199669004.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Gundermann, Hans, Jacqueline Canihuan, Alejandro Clavería & César Faúndez. 2009. Permanencia y desplazamiento, hipótesis acerca de la vitalidad del mapuzu- gun. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 47(1). 37–60. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48832009000100003.Suche in Google Scholar

Gundermann, Hans, Jaqueline Canihuan, Alejandro Clavería & Cesar Faúndez. 2011. El mapuzugun, una lengua en retroceso. Atenea 5(3). 111–131. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-04622011000100006.Suche in Google Scholar

Hall, Daniel Currie. 2011. Phonological contrast and its phonetic enhancement: Dispersedness without dispersion. Phonology 28. 1–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0952675711000029.Suche in Google Scholar

Harris-Northall, Ray. 1990. Weakening processes in the history of Spanish consonants. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Hasler, Felipe & Guillermo Soto. 2012. Determinación de algunas propiedades del subsistema consonàntico del mapudungun y el del español de Chile en los siglos XVI y XVII a partir de los hispanismos léxicos. In Hebe A. González & Beatriz Gualdieri (eds.), Lenguas indígenas de América del Sur, vol. 1, Fonología y léxico (Volúmenes temáticos de la Sociedad Argentina de Lingüística), 92–102. Mendoza, Argentina: Editorial de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.Suche in Google Scholar

Havestadt, Bernhard. 1777. Chilidûğu: Sieve tractatus linguæ chilensis. Leipzig: Teubner.Suche in Google Scholar

Herckmans, Elias. 1907[1643]. Vocabula Chilensia. In Rodolfo R. Schuller (ed.), El vocabulario araucano de 1642–1643. Santiago: Imprenta Cervantes.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, Hyunsoon, George Nicholas Clements & Martine Toda. 2015. The feature [strident]. In Annie Rialland, Rachid Ridouane & Harry van der Hulst (eds.), Features in phonology and phonetics: Posthumous writings by Nick Clements and coauthors, 179–194. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110399981-009Suche in Google Scholar

Ladefoged, Peter & Ian Maddieson. 1996. The sounds of the world’s languages. Oxford: Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Lagos, Daniel. 1981. El estrato fónico del mapudungu. Nueva Revista del Pacífico 19–20. 42–66.Suche in Google Scholar

Lagos, Daniel. 1984. Fonología del mapuche hablado en Victoria. In Actas jornada de lenguas y literatura mapuche, 41–50. Temuco: Universidad de la Frontera e Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenz, Rodolfo. 1897. Estudios araucanos, vol. 97. Santiago: Anales de la Universidad de Chile.Suche in Google Scholar

Loncon, Elisa. 2017. Políticas públicas de lengua y cultura aplicada al mapuzu- gun. In Isabel Aninat, Verónica Figueroa & Ricardo González (eds.), El pueblo mapuche en el siglo XXI: Propuestas para un nuevo entendimiento entre culturas en Chile, 375–404. Santiago: Centro de Estudios Públicos.Suche in Google Scholar

Maddieson, Ian. 2013. Voicing in plosives and fricatives. In Matthew S. Dryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available at: https://wals.info/chapter/4.Suche in Google Scholar

Mena, Daniel & Gastón Salamanca. 2018. Transferencias fonético-fonológicas del español en el mapudungún hablado por la población adulta de Alto Biobío, Octava Región, Chile. Literatura y Lingüística 37. 237–251. https://doi.org/10.29344/0717621x.37.1382.Suche in Google Scholar

Middendorf, Ernst W. 1890. Wörterbuch des Runa Simi oder der Keshua-Sprache, vol. 2. Leipzig: Brockhaus.Suche in Google Scholar

Molineaux, Benjamin & Vasilis Karaiskos. 2021. Corpus of historical Mapudungun. version 1.0 ©. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh. Available at: http://www.amc-resources.lel.ed.ac.uk/CHM/CHM.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Moran, Steven & Daniel McCloy. 2019. PHOIBLE 2.0. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Available at: http://phoible.org.Suche in Google Scholar

Moulian, Rodrigo, María Catrileo & Pablo Landeo. 2015. Afines quechua en el Vocabulario mapuche de Luis de Valdivia. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 55(2). 73–96. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48832015000200004.Suche in Google Scholar

Painequeo, Héctor, Gastón Salamanca & Manuel Jiménez. 2018. Estatus fonológico de los fonos interdentales [n̟], [J̟] y [t̟] en el mapudungun hablado en el sector costa, Budi, Región de la Araucanía, Chile. Alpha 1(46). 111–128. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-22012018000100111.Suche in Google Scholar

Penny, Ralph. 2002. A history of the Spanish language, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511992827Suche in Google Scholar

Rice, Keren. 2011. Consonantal place of articulation. In Mark van Oostendorp, Colin Ewen, Elizabeth Hume & Keren Rice (eds.), Blackwell companion to phonology, vol. 1, chap. 22, 519–549. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781444335262.wbctp0022Suche in Google Scholar

Sadowsky, Scott, Héctor Painequeo, Gastón Salamanca & Heriberto Avelino. 2013. Mapudungun. Journal of the International Phonetic Association: Illustration of the IPA 43(1). 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025100312000369.Suche in Google Scholar

Sadowsky, Scott, María José Aninao & Heggarty Paul. 2019. Sound comparisons: Mapudungun. Available at: https://soundcomparisons.com/Mapudungun.Suche in Google Scholar

Sadowsky, Scott, Maria José Aninao, María Isabel Cayunao & Heggarty Paul. 2015. Huilliche: ¿Geolecto del mapudungun o lengua propia? Una mirada desde la fonética y la fonología de las consonantes. In Ana Fernández Garay & Maria Alejandra Regúnaga (eds.), Lingüística indígena sudamericana, 23–51. Buenos Aires: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires.Suche in Google Scholar

Salamanca, Gastón. 1997. Fonologia del pehuenche hablado en el Alto Bio-Bio. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 35. 113–124.Suche in Google Scholar

Salamanca, Gastón, Elizabeth Aguilar, Katherine Barrientos & Karen Alvear. 2009. Mapuche hablado en Melipeuco: Fonemas segmentales, fonotaxis y comparación con otras variedades. Logos, Revista de Lingüística, Filosofía y Literatura 19(2). 74–95.Suche in Google Scholar

Salamanca, Gastón & Elizabeth Quintrileo. 2009. El mapuche hablado en Tirúa: Fonemas segmentales, fonotaxis y comparación con otras variedades. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada 47(1). 13–35. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-48832009000100002.Suche in Google Scholar

Salamanca, Gastón, Jaime Soto-Barba, Héctor Painequeo & Manuel Jiménez. 2017. Reanálisis de aspectos controversiales de la fonologia del chedungun hablado en Alto Biobio: El status fonético-fonológico de las interdentales [t̪], [n̪] y [l̪]. Alpha 45. 273–289. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-22012017000200273.Suche in Google Scholar

Salas, Adalberto. 1976. Esbozo fonológico del mapuGuqu, lengua de los mapuche o araucanos de Chile central. Estudios Filológicos 11. 143–153.Suche in Google Scholar

Salas, Adalberto. 1992a. El mapuche o araucano. Madrid: MAPFRE.Suche in Google Scholar

Salas, Adalberto. 1992b. Lingüistica mapuche, guia bibliográfica. Revista Andina 10(2). 473–550.Suche in Google Scholar

Saldivia, Ana & Gastón Salamanca. 2020. Rasgos prominentes de la fonologia segmental del lavkenche hablado en la comuna de Los Álamos, variante septentrional del mapudungun hablado en Chile. Logos, Revista de Lingüística, Filosofía y Literatura 30(1). 97–110. https://doi.org/10.15443/rl3008.Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, Gilberto. 1989. Relatos orales en pewence chileno. Anales de la Universidad de Chile 17. 289–360.Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, Gilberto. 2020. Los quechuismos en el mapuche (mapudungu(n)), antiguo y moderno. Boletín de Filología LV(1). 355–377.10.4067/S0718-93032020000100355Suche in Google Scholar

Sánchez, Makarena & Gastón Salamanca. 2015. El mapuche hablado en Lonquimay: Fonemas segmentales, fonotaxis y comparación con otras variedades. Literatura y Lingüística 31. 295–332.10.4067/S0716-58112015000100015Suche in Google Scholar

Sanz-Sánchez, Israel. 2019. Documenting feature pools in language expansion situations: Sibilants in early colonial Latin American Spanish. Transactions of the Philological Society 117(2). 199–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-968X.12154.Suche in Google Scholar

de Valdivia, Luys. 1606. Arte, y gramatica general de la lengua que corre en todo el Reyno de Chile, con un vocabulario y confessionario. Seville: Thomás López de Haro.Suche in Google Scholar

de Valdivia, Luys. 1621. Sermón en la lengua de Chile, de los misterios de nuestra fé catholica, para predicarla a los indios infieles del Reyno de Chile, dividido en nueve partes pequeñas de acuerdo a su capacidad. Valladolid.Suche in Google Scholar

Zúñiga, Fernando. 2001. Escribir en mapudungun: Una nueva propuesta. Onomazein 6. 263–279.10.7764/onomazein.6.15Suche in Google Scholar

Zúñiga, Fernando. 2006. Mapudungun: El habla mapuche. Santiago: Centro de Estudios Públicos.Suche in Google Scholar

Zúñiga, Fernando & Aldo Olate. 2017. El estado de la lengua mapuche, diez años después. In Isabel Aninat, Verónica Figueroa & Ricardo González (eds.), El pueblo mapuche en el siglo XXI: Propuestas para un nuevo entendimiento entre culturas en Chile, 342–374. Santiago: Centro de Estudios Públicos.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction to sound change in endangered or small speech communities

- Where have all the sound changes gone? Phonological stability and mechanisms of sound change

- Where have all the sound changes gone? Examining the scarcity of evidence for regular sound change in Australian languages

- Cross-dialectal synchronic variation of a diachronic conditioned merger in Tlingit

- Vowel harmony in Laz Turkish: a case study in language contact and language change

- The evolution of tonally conditioned allomorphy in Triqui: evidence from spontaneous speech corpora

- Sound change and gender-based differences in isolated regions: acoustic analysis of intervocalic phonemic stops by Bora-Spanish bilinguals

- Place uniformity and drift in the Suzhounese fricative and apical vowels

- Flexibility and evolution of cue weighting after a tonal split: an experimental field study on Tamang

- The emergence of bunched vowels from retroflex approximants in endangered Dardic languages

- The expanding influence of Thai and its effects on cue redistribution in Kuy

- Speech style variation in an endangered language

- Sound change in Aboriginal Australia: word-initial engma deletion in Kunwok

- The dental-alveolar contrast in Mapudungun: loss, preservation, and extension

- Sound change or community change? The speech community in sound change studies: a case study of Scottish Gaelic

- Phonetic transfer in Diné Bizaad (Navajo)

- The evolution of flap-nasalization in Hoocąk

- Sound change and tonogenesis in Sylheti

- Exploring variation and change in a small-scale Indigenous society: the case of (s) in Pirahã

- Rhotics, /uː/, and diphthongization in New Braunfels German

- Generational differences in the low tones of Black Lahu

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Introduction to sound change in endangered or small speech communities

- Where have all the sound changes gone? Phonological stability and mechanisms of sound change

- Where have all the sound changes gone? Examining the scarcity of evidence for regular sound change in Australian languages

- Cross-dialectal synchronic variation of a diachronic conditioned merger in Tlingit

- Vowel harmony in Laz Turkish: a case study in language contact and language change

- The evolution of tonally conditioned allomorphy in Triqui: evidence from spontaneous speech corpora

- Sound change and gender-based differences in isolated regions: acoustic analysis of intervocalic phonemic stops by Bora-Spanish bilinguals

- Place uniformity and drift in the Suzhounese fricative and apical vowels

- Flexibility and evolution of cue weighting after a tonal split: an experimental field study on Tamang

- The emergence of bunched vowels from retroflex approximants in endangered Dardic languages

- The expanding influence of Thai and its effects on cue redistribution in Kuy

- Speech style variation in an endangered language

- Sound change in Aboriginal Australia: word-initial engma deletion in Kunwok

- The dental-alveolar contrast in Mapudungun: loss, preservation, and extension

- Sound change or community change? The speech community in sound change studies: a case study of Scottish Gaelic

- Phonetic transfer in Diné Bizaad (Navajo)

- The evolution of flap-nasalization in Hoocąk

- Sound change and tonogenesis in Sylheti

- Exploring variation and change in a small-scale Indigenous society: the case of (s) in Pirahã

- Rhotics, /uː/, and diphthongization in New Braunfels German

- Generational differences in the low tones of Black Lahu