Set for Life: Old-Age Pensions Provided by Hospitals in Late-Medieval Amsterdam

-

Jaco Zuijderduijn

Jaco Zuijderduijn is an associate professor at the Department of Economic History, Lund University, Sweden. He publishedMedieval Capital markets. Markets for ‘renten’, state formation and private investment in Holland (1300–1550) in 2009 and has since published on old age and retirement in late-medieval and early-modern Europe.

Abstract

Hospitals were among the wealthiest organizations in medieval cities. Their directors managed portfolios consisting of real estate and financial instruments; as a result, they also handled large quantities of money. It has been suggested that they used these to provide a variety of financial services and performed early banking functions. In this study I focus on the role hospitals played in allowing the general population to invest in financial instruments that could serve as old age pensions. Two hospitals in Amsterdam issued corrodies: pensions in kind that gave investors the right to lifelong board and lodging in the hospitals. They also issued life annuities: lifelong monetary pensions. Since both contract types were automatically terminated at death, they required relatively low investments and were ideal for securing an income in money or in kind during one’s final years. In this article, I will demonstrate that via the practice of issuing life annuities and corrodies, these hospitals played a central role in providing the late-medieval urban middle class with access to pensions. I will also show that thresholds for investing were sufficiently low to allow Amsterdam’s middle class to invest in both life annuities and corrodies.

21st-century adults in welfare states save for old age. They do so by paying mandatory taxes which entitle them to state pensions, and in addition, many contribute to voluntary pension funds. Thus, they secure a steady income and prevent impoverishment during old age. Before the welfare state and pension funds created this universal safety net, ageing individuals had to make private arrangements for old age. Historians have conceptualized these arrangements by applying a mixed economy of welfare model that suggests that eldercare was arranged “within a broad, complex and varied spectrum of different kinds of caregiving, that were not mutually exclusive”. [1] The caregiving included the support of “individuals and families, neighbours and communities, mutual-aid organisations, charities and commercial organisations”. [2] Especially the commercial organisations are relatively understudied: two hospitals in late-medieval Amsterdam can help to improve our understanding of the role institutions played in helping to make arrangements for old age.

Pensions are important because people usually do not know how old they will get and, hence, how much money they should put aside for later. The chance of outliving one’s savings is called the longevity risk. This risk can be covered by pooling savings – as is being done by welfare states and pension funds – allowing long-living pensioners to continue to receive benefits because of the contributions made by short-living pensioners. Before the welfare state, hospitals pooled the longevity risk by allowing investments in pensions. Thus, they performed a crucial financial service. This role of hospitals has been identified by Oscar Gelderblom and Joost Jonker, who suggested that various charities in early-modern Amsterdam operated as institutional investors. They pointed out that these were important because they helped by ”providing access to the securities market for savers otherwise unable to enter it”. [3] In other words: charities such as hospitals provided broader segments of the population with investment opportunities that could help them to “manage life-cycle and other income risks”. [4] Gelderblom and Jonker’s description of financial services performed by charities resembles Holger Stunz’ claim that hospitals in the late-medieval Holy Roman Empire became key financial institutions. Stunz wrote that “especially hospitals in the area of the Hanseatic League became important participants in financial markets and were ever since dependent on returns on capital investments”. [5] According to Stunz, much of the wealth hospitals attracted and subsequently reinvested came from small investors who purchased corrodies and life annuities that could serve to provide them with old-age pensions. [6] Winfried Trusen also acknowledged this role of hospitals when he wrote that in the later Middle Ages “many monasteries and hospitals fulfilled the role of public banks”. [7] Much like modern financial institutions, German hospitals thus created pools of pensioners and reinvested their contributions, especially by lending money to city governments. [8] In the South of Europe hospitals also took on banking functions: for instance, Naples’ Santissima Annunziata Hospital allowed workers to deposit small amounts of money and receive interest. [9] And Rome’s Monte di Pièta functioned as a deposit bank for middle class savers whose accounts were usually worth several months’ wages. [10] To what extent medieval hospitals in the territory of present-day Netherlands also provided banking functions for the urban middle class, is less well known.

My purpose in this article is to investigate two hospitals in Amsterdam, in the county of Holland, before the city developed into one of the most important financial centres in Europe. I will especially focus on one financial service: the issuing of financial instruments that could serve as pensions to live off during old age – either entirely or partially. St. Elizabeth’s Hospital and St. Pieter’s Hospital allowed investors to spend their old age extra muros while receiving a life annuity, and intra muros receiving board and lodging. I will focus on the threshold for investment and the socioeconomic background of investors: did the two hospitals allow the middle class to create pensions for old age?

I will first discuss the various instruments that were used to create pensions (1), proceed with a description of Amsterdam and its population (2), and will then introduce the two hospitals: St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s (3). In a previous article (in Dutch) I have analysed corrodies – contracts providing lifelong board and lodging – recorded in a register of St. Pieter’s Hospital. [11] Here, I will add data coming from a register of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital as well and focus on the investments that were required to retire in either hospital. I will also discuss the socioeconomic background of the people who did so (4). I will then proceed with a discussion of life annuities issued by St. Pieter’s Hospital, again focusing on the investments that were required and the socioeconomic background of the investors (5). By focusing on the monetary pensions and pensions in kind that St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s issued, I will uncover their role as the commercial organizations that allowed provisions to be made for old age and that have been conceptualized in the mixed economy of welfare model. I will also discuss the hospitals’ role in moving money from areas where supply was high, to areas where demand was high, to see whether they can already be regarded as institutional investors that resembled modern-day pension funds (6). Finally, I will offer some brief conclusions (7).

1 Pensions in the Later Middle Ages

Before turning to Amsterdam and its population, I should discuss where latemedieval men and women could turn to, if they wanted to create a pension. First, they could try to create a rent by leasing out real estate. Because this strategy involved “market risk” [12] – meaning the possibility that the real value of the rent would decline over time, e.g. because of inflation – this may not have been the preferred option for older adults looking to create a pension. In addition, rents could be cancelled, forcing landlords to find new tenants. An alternative that was particularly well-suited for older adults was the retirement contract. This was an agreement between an older party that handed over capital to a younger party on condition that the latter would provide lifelong board and lodging to the former. Because this was a conditional transfer, the older party had a certain degree of legal security: if they did not receive the agreed-upon board and lodging, they could file a complaint with a court of law and seek annulment of the contract and the restitution of the capital. An example from Amsterdam may help illustrate this sort of transaction. In 1510 the man Luijt Lourenszoon entered a retirement contract: [13] the contract states that he bought his lifelong board and lodging (ewige cost en lijftocht) for 60 guilders (equivalent to c. 240 day wages of a master craftsman). [14] He entered the contract with the married couple Vranck Allertszoon and Griet Goudsdochter, who promised to provide “substantial and honest food and drink, lodging, lighting and fire with which one would likely be satisfied”. As an additional security, they put up all their possessions, present and future. [15] It seems that the 60 guilders were deposited with a hospital [16] and that the younger party would only receive the entire sum after Luijt Lourenszoon passed away – which happened quickly: he seems to have died in late 1511. [17]

Such retirement contracts were agreed in other cities in the late-medieval Low Countries and existed throughout Europe [18] and they strongly resemble corrodies. Corrodies were contracted between ageing individuals or couples on the one hand, and institutions, such as monasteries and hospitals on the other hand. Hospital directors allowed paying customers to invest in corrodies (proven or kostkopercontracten in Dutch; Pfründe in German). These corrodies gave the investors a right to lifelong board and lodging regardless of how many years they would continue to live. Some hospitals housed more than fifty corrodians [19] who would often spend about a decade living in hospitals as retirees. [20] Holger Stunz considers the admittance of corrodians as a marker of a general commercialization of hospitals, which was spurred by the increased involvement of city governors in the management of hospitals, who had realized that these wealthy institutions could support the urban treasury with occasional loans. [21] However, it has also been suggested that commercial eldercare developed from the practice of allowing lay brothers and sisters to pay an entry sum to work as living-in caretakers in hospitals and eventually continue to live there during old age as retirees. [22] Corrodies existed elsewhere in the Low Countries and throughout medieval Europe. [23]

Whereas corrodies provided board and lodging, hospitals also issued financial instruments that gave investors a right to lifelong food and drink without lodging. [24] These instruments resemble annuities in kind – such as the grain annuity – which were common in late-medieval Europe. [25] Investors could also purchase a monetary annuity. Life annuities were especially attractive because of their high returns. Single-life annuities usually had returns of 12.5 percent. Joint-and-survivor annuities, which were contracted for two individuals, yielded about ten percent. [26] As a result, relatively low investments sufficed to secure an income at a certain level. Returns were high because life annuities were terminated at the death of the annuitant or at the death of the surviving annuitant in the case of a joint-and-survivor annuity. Hospitals were not the only institutions that allowed investors to put their money in life annuities – the city of Amsterdam, churches, and water management boards did so as well; [27] private persons are also known to have done so. [28] Yet it makes sense to take a closer look at the monetary pensions that hospitals issued in the later Middle Ages: were they already prominent suppliers of life annuities before Amsterdam became a financial centre?

2 Ageing in Medieval Amsterdam

Around 1500 Amsterdam counted around 10,000 souls. It was on its way to becoming the most prominent city of the county of Holland (the West and Northwest of the present-day Netherlands): Amsterdam’s population has been estimated to have increased to 54,000 in 1600, and 204,000 in 1700. [29] Located at the Zuiderzee, an inland sea that has been partly reclaimed in the twentieth century, medieval Amsterdam was a seafaring city. Its increasing trade in the Baltic Sea area brought the city into conflict with the Hanseatic League, resulting in naval warfare between 1438–1441. [30] Over time, Amsterdam merchants would establish themselves in the Baltics and in the decades before 1500 they also made headway into trade with the French-Atlantic towns.

It is likely that many ageing inhabitants of Amsterdam lacked a family safety net. Cities were characterized by high mortality rates and required a constant stream of immigrants to replace those who died, [31] and these newcomers often lacked a strong support network. Older men and women could also not necessarily rely on their children because high mortality rates in canal cities such as Amsterdam caused high infant and child mortality rates. [32] Especially women were at risk of ending their lives fending for themselves because many of Amsterdam’s male inhabitants never returned from sea. Men and women who reached old age often struggled to make ends meet because the wear and tear on the body and mind that comes with ageing caused them to lose functionality. “Functional age” expresses the process of ageing in terms of the ability to perform tasks at work or at home: it is a “task-specific definition of old age”. [33] The moment when late-medieval people lost the ability to function is likely to have varied widely: those impaired early in life may never have been able to perform tasks, others may have lost this ability in their teens or early adulthood due to accident or disease. But even people who escaped this misfortune would eventually develop elderly impairments: at some age the average person loses the ability to function as well as before. In the past decades we have witnessed how the average person’s healthy life years have increased, and as a result, loss of functionality has also moved to slightly higher ages. When the average historical person might have lost their functionality is very difficult to estimate. But given the hostile disease environment, absence of modern medicine, and lack of power tools in the workplace, it must have been earlier than today. [34]

Nevertheless, historians are divided over the question as to when old age began: some argue for fifty years of age, others for sixty. [35] How many people in late-medieval Amsterdam celebrated their fiftieth or sixtieth birthday? In the absence of population registers it is difficult to give precise figures, but Marco van Leeuwen and Jim Oeppen’s reconstruction of Amsterdam’s early-modern population suggests that more than 20 percent were over the age of fifty and almost 10 percent were over sixty. [36] It seems possible to assume that in the later Middle Ages at least one in ten inhabitants may have been old. [37] This also means that people who had survived early childhood could expect to grow old: newly-weds who had established their own households around the age of thirty could reasonably anticipate living another thirty years and were thus likely to reach the threshold of pre-modern old age – even if we set this as high as sixty. [38]

Could people prepare for old age? There are reasons to believe that households in the relatively affluent Northwest of Europe earned enough money to set money aside for later. Opportunities for life-cycle saving may have been particularly large in the one-and-a-half century after the first outbreak of Yersinia pestis: in the wake of the Black Death, living standards increased and a relatively affluent population may have been able to set money aside. [39] Archaeological findings of moneyboxes in cities close to Amsterdam suggest that saving may have been common among various social layers already in the later Middle Ages. [40] In addition, the medieval plague brought a redistribution of wealth [41] that may have allowed many to use real estate or money to acquire an old-age pension.

3 Two Hospitals Providing Old Age Provisions

St. Elizabeth’s Hospital (also known as Oude gasthuis van de Heilige Geest or Grote gasthuis van de Heilige Geest) was established between 1350–1371 at the Dam square where the Royal Palace of Amsterdam stands today. A second hospital was established around 1390, St. Pieter’s Hospital (also: Sint Pieter in de Nes) in today’s Red Light district. The two institutions merged in the late fifteenth century when the extension of the city hall required the destruction of St. Elisabeth’s Hospital. [42]

The sources left behind by the administration of the two hospitals allow for an analysis of their sale of corrodies and life annuities. These financial instruments were also issued by other institutions: I have not studied the Holy Sacrament Hospital (Heilig Sacramentsgasthuis) which only seems to have been of minor importance. [43] I have also not studied Our Lady’s Hospital (Onze Lieve Vrouwegasthuis) even though it is clear that it also provided opportunities to create old age provisions. [44] The same is true of Amsterdam’s St. George’s Hospital (St. Joris Hospital), initially located outside the city, which had already turned into a commercial retirement home in the later Middle Ages: in 1514 it was called corrodians’ home (proevenhuys). [45] St. George’s Hospital would continue to be a prominent retirement home in the early-modern period; however, for the latemedieval period the source base of this institution is too small for an in-depth analysis. Outside Amsterdam, St. Anthony’s Hospital (St. Anthonisgasthuis, also known as St. Nicolaasgasthuis or leprosarium) also served as a corrodians’ home. [46]

Medieval hospitals are usually associated with charity. They were founded to provide care to the vulnerable members of society. St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospitals provided this type of care. This was paid for by returns to a large portfolio consisting of land in the countryside outside Amsterdam, houses in the city, money in the treasure chest, and financial investments. The hospitals’ directors acted as asset managers who were responsible for making sure that yields coming from the capital sufficed to carry out charitable activities. They oversaw agricultural production on the hospital lands, rented out real estate and (re-) invested money. St. Pieter’s Hospital grew increasingly wealthy over time: in 1650 its directors were responsible for a portfolio, consisting of securities, private loans, and real estate, which can be estimated to have been worth fl. 539,640 – comparable to €5.5 million today. [47] Part of this wealth was already being built up in the later Middle Ages when the hospital directors managed to acquire real estate and sell annuities. [48]

Hospitals were not only indispensable for providing poor relief, but they also provided financial services which were aimed at maintaining and, if possible, extending the investment portfolio that was the foundation of their operations. When it came to asset management, the directors were no benefactors; to secure the future sustainability of their organisation, they applied a quid pro quo approach. Both life annuities and corrodies were contracts that gave investors rights to returns on their investments; these rights could be exercised by filing a complaint with a court of law. Considering that directors entered binding agreements that could run for several decades, it is not surprising that they demanded investors should pay up to the last penny – no matter how much trouble this caused. Thus, the woman Gherberich, a former baker, was allowed to pay only 5.3 guilders when she entered St. Elizabeth’s Hospital as a corrodian, but she also had to agree to hand over an additional 25.5 guilders in 1474, and the remaining 25.5 guilders in 1475. It seems that even paying in instalments was difficult for her: the hospital administration registered various small sums paid on her behalf. Some of these seem to have been debts that her former customers finally repaid: “11.5 stoter for bread and other good commodities”, “23 stuivers and one oude lev for bread” and “about 2 Rhenish guilders for commodities”. [49] Gherberich was clearly struggling to raise the money that she owed to the hospital. To give another example of the strictness of St. Elizabeth’s directors: the woman Griet agreed to pay 85 guilders for her corrody, namely 25 guilders up front, and the remaining 60 guilders later, after her sister’s house had been sold (as Griet was entitled to one-quarter of the yield). If the sale should have raised more than 60 guilders for Griet, the difference would have gone to the hospital; in case the sale would have raised less, one Pieter Roepig acted as guarantor. Eventually the latter had to step in and pay the 60 guilders. [50]

That the directors worked on a quid pro quo basis can also be seen in the contract between St. Elizabeth’s and Jan Damezoon. The corrodian was to pay 135 guilders: 69 guilders up front when he entered, followed by two instalments of 33 guilders each, “on condition that if the said Jan Damez would die before [the two terms were paid] the hospital would receive these sums as if he was still alive”. Fortunately for Jan Damezoon, he lived long enough to pay the final instalment and the administrators noted: “item Jan Damez has paid all sums”. [51] The directors took the corrody contracts seriously, and understandably so: just like they committed to providing food and lodging to long-living corrodians, their counterparties should commit to paying the full entry sum regardless of how many years, months, or days they would continue to live. The same was true for the woman Alijt Mouris, whose corrody was paid by her brother-in-law. He had to promise that “he would nevertheless pay the sum within a year” regardless of whether Alijt Mouris should die earlier. [52]

Investors could put their money in two distinct types of corrodies. The more luxurious one is not always clearly indicated although it seems that it was usually called proveniers contract; the less-luxurious one appears in our sources as a corrody under the lamp (onder die lamp) [53] and is also known as a commensaal contract. [54] The Amsterdam sources do not provide many details about the distinction between the two contracts but usually corrodies differed in terms of both board – quality and quantity of food and drink – and lodging – either providing a private room for the bigger investors or a bed or bed box in a nursing hall for retirees with small purses. It seems that ageing individuals carefully sought to maintain their social position even when they moved into a retirement home; hospitals were therefore spatially segregated, with dining and living areas designated for various classes of corrodians. [55]

Even commensalen could feel elevated above the ranks of the poor who were admitted free of charge and who were on the lowest rung of the ladder. Distinguishing oneself by paying for retirement was probably important: Ludwig Pelzl and I have suggested that by handing over capital, corrodians had managed to prepare for old age. Thus they demonstrated to have embraced civic virtues, such as thrift, prudence and industriousness, which made for good citizenship. [56] Thus, paying for retirement was not only beneficial for hospital directors but also for ageing citizens looking to distinguish themselves from hospital inmates who could invest less – or nothing at all.

The hospitals thus mirrorred the socioeconomic position extra muros by allowing wealthier investors to purchase more luxurious corrodies. The most expensive corrody sold by St. Elizabeth’s Hospital went to the woman Obrich Dircsdochter, who paid dearly for a relatively luxurious old age. Her contract stated:

“[…] Obrich will individually inhabit a small room above the passantenhuis [xenodocium] and below [her room] she will have a small space to spin or do other handicrafts [...]. [57]

Considering that Obrich was St. Elizabeth’s highest-paying customer – having paid 243 guilders, equivalent to almost 972 day wages of a master craftsman – it is likely that her spinning should be considered as a pastime rather than paid labour (see section 4). That women could consider spinning as just a hobby is also indicated by the case of Katrijn Hilbrantdochter, who agreed on a corrody with St. Pieter’s Hospital in 1482, but who found out to her astonishment that she had to work. To be relieved of this she had to pay an additional sum “so she did not have to work in textiles except for her pleasure”. [58] As we will see in the next section, corrodians could pay for a variety of privileges that would make their stay more enjoyable and allowed them to distinguish themselves from other residents.

Before proceeding I must say a few things about the sources. Amsterdam’s medieval records are relatively scarce, especially when it comes to public administration. But the hospital archives are quite extensive and these have been digitalized thanks to an initiative by Stichting Middeleeuwse Archieven Amsterdam. [59] The records are notoriously difficult to navigate: historic administrators appear to have used a logic largely unknown to us. For instance, it is not uncommon to see references to additional documentation that was to be found in this or that drawer or chest in the medieval hospital; needless to say, this is of little help to the 21st-century scholar. In addition, what has been preserved consists mostly of registers that often lack a systematic approach: they give brief summaries of contracts and agreements that the hospitals had entered and provide notes about payments, repayments, and cancellations of contracts. Whether all relevant information has been preserved is impossible to tell: there are some known unknowns, for instance when a brief reference is made to an official contract that is no longer in the fonds. But there are probably also many unknown unknowns. The following analysis is based on archival sources that appear systematic but that do not capture the entirety of investments made with St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospitals in the decades around 1500. [60] Nevertheless, these records can help us to understand the role medieval hospitals played in preparing for old age.

4 Investors in Corrodies

Two registers note a total of 85 corrody contracts from between 1472 and 1538. The first is from St. Pieter’s Hospital and contains 67 corrody contracts between 1474 and 1538. The second was recorded in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital and includes eighteen corrody contracts between 1472 and 1497. [61] My goal is twofold: to reconstruct entry sums paid for corrodies and the socioeconomic background of investors.

Reconstructing entry sums is often difficult because prices for corrodies were never stated in the register. I can only observe the payments investors made in money and in kind. Fourteen investors paid a sum in ready money: their payments reveal the entry sum. But most corrodies include one or more payments in kind. The least problematic of these are financial instruments. For instance, Lobberich Harmans paid a lump sum of 30 guilders to the directors of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital and also handed over “a contract of one Postulaatgulden [about ½ guilder, J.Z.] per annum [mortgaged] on a piece of land in Diemen” – a village to the southeast of Amsterdam. [62] How much the original investor had paid for this financial instrument is unknown, and the same goes for what it would have fetched if Harmans had decided to sell it in the secondary market instead of handing it over to the hospital. However, it is possible to estimate the value of this financial instrument; I have done so by using the prevailing interest rate (6.25 percent) meaning that the value was probably 16 Postulaatgulden (at 1 guilder/0.0625), or roughly 30 day wages of a master craftsman. [63] I have applied the same method to reconstruct entry sums of other corrodies that were (partly) paid by handing over a financial instrument.

Much more problematic are payments made by handing over real estate. For example, Claes Woesgen obtained a commensalen contract with St. Elizabeth’s Hospital “for a house”; Geerte Louwen also obtained a commensalen contract “for a house”, and, even more obscurely, also for “other things”. [64] These unknown objects cannot be valued and the same is usually true for real estate. Exceptionally, St. Pieter’s Hospital corrodian Ux Gerijt Yef handed over three plots of land of which the value can be estimated at 74 guilders. [65] This is equivalent to 296 day wages of a master craftsman, which agrees nicely with the corrody prices reported further on. But in other cases, I am in the dark when it comes to the value of the real estate that was used to pay for corrodies.

By reconstructing the value of payments, I can provide an impression of 57 entry sums (see Table 1). The entry sums show a large variation, which is likely caused by several things. First, I do not know at what age of corrodians entered St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospitals. It makes sense to assume that hospital directors considered the age of the corrodian when they negotiated the entry sum: the younger corrodians were, the longer they would probably be a financial burden to the hospital. Of course, medieval hospital directors must have been aware of this, as an example from the German city Heilbronn shows. Here, the hospital directors were satisfied with a corrody price they had just negotiated, noting that “the man is at a good age, hopefully he will not live long”. [66] Institutions in eighteenth-century Amsterdam used price lists to determine entry sums: the directors asked twice as much from a fifty-year old than from a 69-year old. [67] Although their late-medieval predecessors also likely adjusted prices based on the age of corrodians, it is impossible to be certain about this because the sources are almost completely silent when it comes to the negotiations between hospital directors and corrodians; ages of retirees are never mentioned. Nevertheless, differences in age and, hence, life expectancy, seem to offer the best explanation for the large variation in entry sums.

Entry sums to St. Pieter’s Hospital and St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Amsterdam, 1476–1538 (in guilders with values in day wages of a master craftsman in brackets).

| No. of contracts | Average entry sum | Median entry sum | Minimum entry sum | Maximum entry sum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Pieter’s Hospital | |||||

| Commensalen (all) | 14 | 67 (268) | 55 (220) | 12 (48) | 190 (760) |

| Commensalen (only entry sum) | 2 | 36 (144) | 36 (144) | 22 (88) | 50 (200) |

| Proveniers (all) | 29 | 114 (456) | 100 (400) | 9 (36) | 340 (1,360) |

| Proveniers (only entry sum) | 7 | 58 (232) | 50 (200) | 9 (36) | 150 (600) |

| St. Elizabeth’s Hospital | |||||

| Commensalen (all) | 2 | 25 (100) | 25 (100) | 4 (16) | 46 (184) |

| Commensalen (only entry sum) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Proveniers (all) | 12 | 117 (468) | 104 (416) | 40 (160) | 243 (972) |

| Proveniers (only entry sum) | 5 | 75 (300) | 70 (280) | 40 (160) | 108 (432) |

Notes: Commensalen refers to the less-luxurious corrody contracts, while proveniers refers to the more luxurious corrody contracts. Those followed by “all”, include contracts which, apart from a monetary entry sum, also included unvalued goods, obligations or tasks; those followed by “only entry sum”, include contracts financed by a monetary entry sum only. One guilder consisted of 20 stuivers. Day wages for Amsterdam are only available after 1540, see: L. Noordegraaf, Hollands welvaren? Levensstandaard in Holland, 1450–1650, Alkmaar, 1985, p. 67. Day wages of master craftsmen in Haarlem (20 km to the west of Amsterdam) were around five stuivers on average in the final decades of the fifteenth century: I use these day wages as a proxy for Amsterdam, see: Ibid, p. 69. For the first decades of the sixteenth century average day wages for the Western Netherlands also indicate 5 stuivers, see: J. de Vries/A. van der Woude, The first modern economy. Success, failure and perseverance of the Dutch economy, 1500–1815, Cambridge 1997, pp. 610611. All values are deflated expressing them in day wages of a master craftsman of 5 stuivers. Other professions like journeymen earned around 4 stuivers, while unskilled labourers might earn 3.5 stuivers, see: Idem. Source: SAAG, inv. nrs. 7, 82.

But variation was probably also caused by corrodians making the hospital their universal heir, which means that the directors could expect to receive everything corrodians would eventually come to possess, especially through inheritances. The odds of them receiving large inheritances would usually have been small, first because few retirees would have had parents alive, from whom to inherit, and second because customary law made it not very likely that they would inherit from siblings. [68] Yet, it seems that investors who struggled to finance their corrodies could compensate by making the hospital their universal heir. About half of the corrodians did so, while the others could bequeath their possessions. It is possible that this practice contributed to the variation in corrody prices – although I must point out that it seems that the inheritances left to the hospitals were usually quite modest. [69]

Another factor that may explain the variation in entry sums is related to the practise of allowing corrodians to agree to help with chores – as long as their physical and mental condition would allow for this. It makes sense to assume that they agreed to this to negotiate lower entry sums but whether this would have led to large or small discounts is impossible to say. Some corrodians were merely assigned odd jobs that were carried out by the community of inmates, such as Joest Everts, who would help in St. Elizabeth’s to “sound the bell as is usual and prepare the altar [for holy mass].” He would also “go around begging with a plate in the hospital” and also in the marketplace. And he would do all other chores that the present and future directors would consider reasonable “except for heavy work such as diking, damming and transferring the sick etc.” In contrast, his wife Agniese Everts would mend the blankets, pillows, and sheets, and furthermore she would “keep the keys and all other things” in the hospital “until the directors would hire another woman to do so”. [70] Agniese Evert’s tasks were apparently considered a position, whereas her husband’s tasks rather seem to have consisted of odd jobs. To give another example: Claes Willemszoon was assigned the following tasks:

“To take care of the hospital’s inventory in the same manner as he would take care of his own inventory namely purchasing rye, meat, salt, fuel, and other relevant commodities and doing maintenance to the hospital.” [71]

In addition, Willemszoon would handle juridical procedures outside Amsterdam, would take care of the sick, and would be allowed to travel to carry out his “business” (neringe). He was given a few important tasks, but how these influenced the price he paid is anyone’s guess.

With some corrodians working and others not, this brings us to another factor that may have influenced entry sums: although the hospitals’ administration divides retirees in commensalen and proveniers, differences existed within these categories. Commensalen could pay extra for more and/or better food, drink, clothing and even peat used for heating, than the men and women they shared the nursing hall with. Proveniers could do the same and they could also invest in more spacious accommodation – think of Obrich Dircsdochter and her private room and space to do handicrafts. Although few contracts mention such privileges, we cannot exclude the possibility that the variation in entry sums was in part caused by differences in the quality of board and lodging. [72]

With these caveats in mind, it is possible to now turn to Table 1. The table shows entry sums of those contracts where the sums paid were either given or could be estimated. I have decided to focus on corrodies that provided board and lodging for one person; two-person corrodies were also issued, but were relatively rare, so it is difficult to generalize about these. Table 1 thus shows data for 57 contracts: fourteen were paid with ready money, and 43 included non-cash payments: real estate, financial instruments, the corrodian’s inheritance, and the promise to work for the hospital – sometimes combined with cash payments (see the tables in the Appendix). As I indicated before, the spread is considerable: the lowest amount paid for a commensalen contract was four guilders (sixteen day wages). The investor was Janne van die Warmoesman, who would also hand over his household effects to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Under normal circumstances this would not have sufficed: Van die Warmoesman’s admittance was considered an act of charity because he was impaired (“om goids will also hi onmachtich is”). [73] On the other end of the spectrum there are high entry sums, such as the one paid by Obrich Dirsdochter, which came with a privileged dwelling and the right to come and go as she pleased. Although caution is required when interpreting the data in Table 1, it seems that most commensalen contracts required entry sums worth less than one year’s wages (the median is below 250 day wages). Such investments sufficed to acquire the right to lifelong board and lodging – regardless of how long corrodians would be able to do chores, or the size of the bequest they would leave to the institution. Most proveniers contracts required entry sums worth less than two years’ wages (the median here is below 500 day wages). [74] These prices are similar to those observed in Leiden – 40 km southwest of Amsterdam – where it was usually possible to purchase a corrody for the equivalent of between 250 and 500 day wages. [75]

Were corrodies within reach of the middle class? This question is, again, difficult to answer because the sources do not reveal many details. Occupations of corrodians before they entered the hospitals offer the best clues. In addition, professions of deceased spouses and other relatives may help to identify the socioeconomic background of corrodians. This approach is not unproblematic because it is not always possible to distinguish between professions and occupational surnames. Only in a few instances can close reading provide certainty, so I will provide the occupations of corrodians and the entry sums they paid when this is possible.

The St. Elizabeth’s Hospital corrodian Janne van die Warmoesman is likely to have been identified in the register by a parental occupation rather than a last name (van de indicates “child of”, a warmoesman is a grocer in Dutch). He paid the equivalent of 16 day wages to become a corrodian. [76] The same is probably true of Nyesgen die naeyster (naeyster is a seamstress in Dutch). She paid 160 day wages to become a corrodian. [77]

This hospital also became home to Gherberich Claesdochter de baxter (baxter is a baker in Dutch). She paid 227 day wages and was indeed a retired baker: hospital directors collected outstanding debts owed to her for deliveries of bread. [78] Another man, IJsbrant, may have been educated as a clergyman: he agreed to perform religious services in the absence of a priest (and paid the equivalent of 800 day wages for his corrody). His additional task of representing the hospital when it laid claims for outstanding debts suggests he may have worked in the administration of a religious institution. [79] A similar background can be suspected in the case of Claes Willemszoon, who agreed to represent the hospital in legal procedures (zeventuigen) outside Amsterdam (and who paid the equivalent of 432 day wages for his corrody). [80] The contract of Wybrich Andriesdochter (at the equivalent of 280 day wages) mentions her sister, Baert Dirck Wiggertszoon timmermanswijf (timmermanswijf meaning wife of a carpenter in Dutch): this corrodian also probably came from a middle-class family. [81] A male corrodian, Augustijn was a sailor (and paid the equivalent of 400 day wages for his corrody): he was admitted on condition that he would spend the first three summers as a corrodian working at sea, handing over his earnings to the hospital. [82]

A sailor can also be found among the corrodians of St. Pieter’s Hospital: Gerijt Janszoon stuerman (stuerman means skipper in Dutch). He negotiated a commensalen contract on the condition that “if he wanted to set sail, he would be allowed to come and go”. [83] The man Dirc Pieterszoon Pelser (pelser meaning tanner in Dutch) invested in the same type of contract and “when he worked outside [the city] he would eat and sleep outside [the hospital]”. [84] Another commensaal, Willem die Cruijster, was a mason. [85] Among the investors in the more luxurious proveniers contracts were another skipper, a carpenter, clog maker, barber-surgeon, chaplain, a priest (at the equivalent of 600 day wages), a sexton and a lower civil servant (stedeknecht; at the equivalent of 400 day wages). [86]

So, it seems that at least some of the corrodians had a middle-class background and they were able to pay entry sums in the range of one to two years’ wages. This is in line with what has been observed in other institutions. For Leiden’s St. Hiëronymusdal hospital I was able to cross-reference corrodians with real estate tax records: before they retired into the hospital they were usually assessed as average wealth holders or lower than that. [87] Similarly, Ludwig Pelzl’s analysis of 1,425 occupational titles in corrody contracts in the early-modern Holy Roman Empire confirms that these investments were especially popular among middle classes: only 12 percent of the corrodies were purchased by high-skilled individuals, 64 percent by those semi-skilled – i.e. the “urban artisanry” in Pelzl’s words, and the remainder by the low or unskilled workers. [88] It seems that corrodies in late-medieval Amsterdam were purchased by members of similar social groups.

5 Investors in Life Annuities

Apart from corrodies, the other major provision for old-age were life annuities. Much like today, these were convenient for late-medieval people looking to secure a pension. In 1538 the baker Pieter Pieterszoon van Enkhuizen invested in a jointand-survivor annuity to create an annual income both for himself and for his maidservant Ymme Pietersdochter. [89] He invested 540 guilders with St. Pieter’s Hospital and in return acquired an annuity of 30 guilders per annum for as long as either of them lived. [90] The baker negotiated an interesting clause: in case he would outlive his maidservant, he would be allowed to nominate another individual – perhaps her successor – as a fellow recipient of the 30 guilders. [91] Such a pension for a maidservant who outlived her master must have been an attractive labour condition and could tie trusted servants to the household of an ageing individual. [92] St. Pieter’s Hospital records show that Ymme Pietersdochter indeed outlived Pieter Pieterszoon; he only received the annuity for two years until his death in 1540. This left Ymme Pietersdochter without a job but with an annual income which was paid out for another fourteen years until she passed away in 1554. [93] The 30 guilders she received were equivalent to c. 85 day wages of a master craftsman, [94] which was likely more than enough to live off. The construction whereby a master used a joint-and-survivor annuity to provide a servant with a pension was quite unusual. But for a baker, such as Pieter Pieterszoon, investing in a life annuity would not have been unusual.

St. Pieter’s and St. Elizabeth’s Hospitals began to sell life annuities in the fifteenth century. According to the historian Bas de Melker, the directors of the latter institution moved from issuing perpetual annuities (erfrenten) to life annuities. [95] They did so after the hospital burnt down in 1421: to rebuild, the hospital sold thirteen life annuities. [96] A register lists the names of the annuitants and how much money they received. But the source is difficult to interpret, in part because the ink has partly dissolved, and because the life annuities are expressed in a variety of currencies of which the value is hard to reconstruct. [97] Moreover, the register does not indicate how much the investors had paid for their annuities. Usually, single life annuities could be purchased for about eight times the value of the annuity and joint-and-survivor annuities for about ten times the value of the annuity; [98] in what follows I will use this measure to estimate how much annuitants had invested.

The life annuities that the directors of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital issued after 1421 were ten single life annuities and three joint-and-survivor annuities. The jointand-survivor annuities were purchased by three pairs of investors: Dirc Allertzoon and his sister, together with Lobrich Jacop Vlaminc and her mother, as well as Jacop Allert and his wife – to illustrate just how complex such constellations could be. The annuity of Jacop Allert was paid for 37 years (!) because he only passed away in 1458. [99] For his annuity with a nominal value of 5 nobel, he received 300 stuivers in 1457 – equivalent to 60 day wages of a master craftsman. [100] Lobrich Jacob Vlaminc is still mentioned in 1459; her annuity of two pieterman was not worth much though, only about seven day wages. [101] Another annuitant, Margriet Taems, also lived to reach at least 1459. [102] These examples of life annuities paid for 28 years or longer suggest that hospitals may have had to deal with so-called adverse selection: life annuities were particularly popular among investors who were confident they would live long enough to earn back their investment.

Registers from St. Elizabeth’s Hospital covering 1455–1457 and 1459–1460 are somewhat easier to interpret. They express most annuities in stuivers, which can give us an idea of their value. In 1455 to 1457 the range of eight out of ten contracts is known: annuitants received between 29 to 300 stuivers, or 6 to 60 day wages of a master craftsman. For 1459 to 1460 I have the range of three out of six life annuities: annuitants received 30 to 60 stuivers, or 6 to12 day wages. Most life annuities were thus quite small. Assuming that these were purchased for eight to ten times the value of the annuity, [103] prices for these financial instruments probably started at around 48 to 60 day wages, which would have made these investments affordable for Amsterdam’s middle class. Occupational titles suggest the socioeconomic background of some of the annuitants: Elijsabeth Harman is called a shoemaker’s daughter, [104] Margriet Taems is called a textile worker’s daughter, [105] Gheert is indicated as widow of Peter the glassmaker, [106] and Clara Jan Peterszoon is called the clogmaker’s daughter. [107]

More information on the life annuities issued by hospitals becomes available around 1500. The directors of St. Pieter’s Hospital kept a register of annuities they paid out in the period between 1497 to 1539. These included life annuities, redeemable annuities, and perpetual annuities. [108] The register is difficult to interpret: it was kept for decades and notes about annuities that were paid out were recorded in a variety of different hands. Corrections were made when recipients of life annuities passed away by crossing out names. Fortunately, the register has an index, which was probably recorded later, and which gives the page numbers, names of the annuitants, and the annuities the hospital had to pay. Using this index, I have created an overview of the life annuities the hospital owed when the register was recorded, which was most likely in or shortly after 1497.

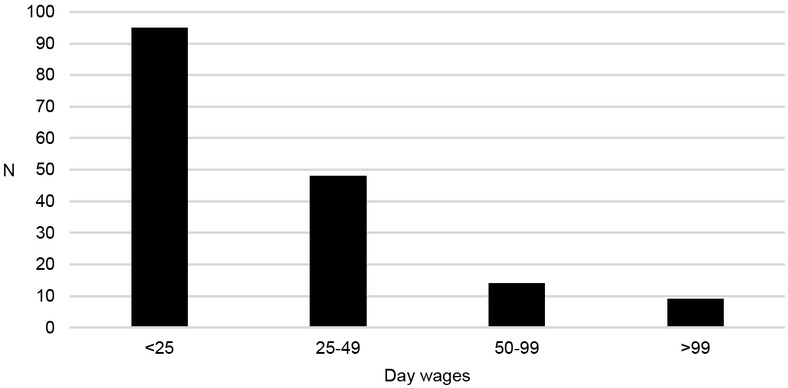

The register allows for a look at the distribution of the annuities. In the historiography, investments in life annuities are often associated with high finance. For instance, it has been suggested that annuities issued by cities were typically purchased by members of the political and economic elite. [109] However, a closer look at the Amsterdam data reveals that many of these public annuities often yielded returns that were so small that it is difficult to imagine that they were the investments of the high and mighty. In fact, many annuities did not amount to more than several weeks’ or even days’ wages of a master craftsman, which would have been small change for the wealthy, but potentially indispensable for ageing members of the middle class. Such small annuities required relatively small initial investments, which may have made them affordable for the population at large. Elsewhere I have used the notion of a “threshold approach”: the principal sums of annuities can be used to determine whether these were sufficiently low to have allowed the middle class to invest. [110] Analyses of annuities issued by three cities demonstrate a marked left-hand distribution, suggesting that public debt consisted of many small annuities. [111] Data from St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospital suggests the same. The 1497 to 1539 register lists 166 life annuities, with 57 percent of these paying out less than 25 day wages of a master craftsman, with another 29 percent in the range of 25 to 49 day wages (see Fig. 1). When we assume that these financial instruments required investments of eight to ten times the value of the annuity, investments in the range of 200 to 250 day wages sufficed for 57 percent of the annuities, and between 250 and 400 to 500 day wages sufficed for the more expensive 29 percent. Life annuities issued by St. Pieter’s Hospital were in the range of one to two years’ wages of a master craftsman; this agrees nicely with the corrody prices I discussed earlier.

Life annuities due at St. Pieter’s Hospital, Amsterdam 1497–1539 (in day wages of a master craftsman). Note: N=166; the deflator, wages of a master craftsman, is explained in Table 1. Source: SAAG inv. nr. 78.

Ideally, the register would also provide details about the socioeconomic background of the annuitants. However, it does not provide many occupations. Fij Heijnen, a wet nurse who had breastfed the daughter of Willem Andrieszoon, received a life annuity of six guilders (worth 24 day wages): the context suggests that she may have been rewarded with this life annuity to thank her for nursing the baby. A mason’s widow received an annuity corresponding to 40 day wages. [112] Another woman who is recorded as a flax merchant (vlasvrouw), received an annuity worth twenty day wages. [113] A carpenter and his wife received an annuity equivalent of 120 day wages. [114] A joint-and-survivor annuity was paid to two brothers, one a Hamburgerman (likely a skipper sailing to Hamburg) and one a painter (verver); [115] the two had to share the equivalent of twelve day wages.

Occupations can mostly be traced by looking at life annuities that were paid out to people living in (semi-) religious institutions, such as monasteries, nunneries, and beguinages: altogether 15 annuities went to at least one annuitant living in such an institution (see Tab. 2). One monk, Reijer Fredericks in St. Paul’s convent, held two annuities: one was equivalent to 13.2 day wages, and another ten times as much (132 day wages). [116] This is an outlier: nuns and beguines usually did not receive such large sums, their average and median annuities are below the values observed for the other annuitants who did not live in (semi-) religious institutions. These women often received life annuities that were financed by their relatives to cover their living expenses in nunneries and beguinages. [117] In addition, seven life annuities were paid out to priests – again these were relatively small.

Annuities of annuitants living in (semi-) religious institutions and hospitals (in guilders with values in day wages of a master craftsman in brackets).

| Monks | Total 2 | Average annuity 18.2 (72.6) | Median annuity 18.2 (72.6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuns | 7 | 5.3 (21.3) | 5.0 (20.0) |

| Beguines | 6 | 3.7 (14.7) | 4.0 (16.0) |

| Priests | 7 | 6.3 (25.1) | 5.0 (20.0) |

| Mothers | 13 | 6.6 (26.4) | 3.0 (12.0) |

| Corrodians | 3 | 6.0 (24.0) | 6.0 (24.0) |

| Other | 128 | 8.3 (33.1) | 6.0 (24.0) |

Note: The values are the annual sums received. Joint-and-survivor annuities, where at least one annuitant lived in a (semi-) religious institution or hospital, are categorized under (semi-) religious institutions and hospitals; the deflator, wages of a master craftsman, is explained in Table 1. Source: SAAG, inv. nr. 78.

Sixteen annuitants lived in hospitals. They included hospital staff. The register mentions Lucij Jans “our kitchen mother” (koekenmoer in Dutch; “mothers” were women who worked in hospitals in the capacity of lay sisters). She apparently was in charge of the kitchen at either St. Elizabeth’s or St. Pieter’s Hospital. [118] But she also received four life annuities that altogether yielded the equivalent of 42 day wages. Trui Jans, “mother” in St. Anthonis Hospital outside Amsterdam, received a life annuity worth 28 day wages. [119] Obrich the buitenmoer (headmistress) of this hospital received two annuities amounting to 64 day wages; [120] given her function, she was most likely a member of Amsterdam’s political elite. She would not have lived in the hospital, in contrast to the other “mothers” mentioned in the register; why these resident women, who served the hospital, also received life annuities, is not immediately clear. Perhaps their investments came from capital they had inherited while serving as “mothers”; by investing in life annuities they assured themselves substantial spending money.

Three life annuities went to corrodians. Zivert Claeszoon “our corrodian (onse provenaer) has six guilders per annum life annuity for the duration of his life and no longer”. [121] Indeed, his corrody contract mentioned that in addition to board and lodging in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital he would receive six guilders per year. [122] The corrodian Augustijn received a life annuity of two guilders: [123] he may have been the sailor Augustijn who was admitted on instruction of the mayors of Amsterdam in 1475, and who would continue to work for another three years after his admittance, while keeping his earnings (see Section 4). [124] Did he invest his earnings in a life annuity with St. Elizabeth’s Hospital? The widow Katrijn Gherit Henriczoon received a life annuity of ten guilders. [125] She had entered St. Pieter’s Hospital at an unknown date together with her husband. [126]

Life annuities paid out to corrodians can help to underline a point I made above: corrody prices were negotiable. This can be illustrated by Zivert Claeszoon who received both a corrody and a life annuity. His corrody was paid for by Zivert’s brother, Heijnric Claeszoon:

“Heijnric Claeszoon has granted the hospital a ratified contract yielding [9.5 guilders] per annum, mortgaged on Jan Dirczoon the brewer’s house. And demanded that his brother [Zivert] will have a corrody for as long as he will live and a life annuity of [six guilders].” [127]

A financial instrument yielding 3.5 guilders per annum would have been enough to purchase the corrody. The difference (9.5 guilders less 3.5 guilders) was transferred into a life annuity for Zivert. Corrody prices were subject to negotiation: if the capital that investors offered exceeded this price, the hospital directors offered compensation; if the capital that investors offered fell short, they may have tried to compensate by promising to work or by making the hospital the universal heir.

In addition to the 166 life annuities in the register, St. Pieter’s Hospital also paid 53 perpetual annuities and redeemable annuities. [128] As explained above, these financial instruments were not ideal for making provisions for old age because returns to investments were much lower than on life annuities. Records also make it difficult to find out much about investors: perpetual annuities were not paid out to individuals, but to institutions, such as monasteries and beguinages. Redeemable annuities were paid out to individuals but could be passed on from one generation to the next. As a result, the annuitants listed around 1497 may have been the investors, or they may have inherited the annuity. Consequently, the occupations of these annuitants cannot tell us much about the socioeconomic background of the original investors.

6 Medieval Hospitals as Early Banks?

It is important to realize that St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospital were only responsible for part of the investment opportunities in late-medieval Amsterdam. Life annuities were also issued by other hospitals, [129] the New Nunnery (Nieuwe Nonnenklooster), [130] and, as explained before, the city of Amsterdam. Corrodies were also sold by St. Joris Hospital and St. Anthonis Hospital, which both specialized in providing board and lodging, while Our Lady’s Hospital is also known to have admitted such paying customers. [131] Even Amsterdam’s monasteries took in the occasional paying customer. [132]

I will now return to Oscar Gelderblom and Joost Jonker’s point about charities as institutional investors: did the hospitals bridge the gap between the middle class and what they call the “securities market”? [133] The hospitals may have lent money to the city of Amsterdam – as was suggested by Holger Stunz for hospitals in the Holy Roman Empire. They may have done this by investing in annuities issued by the City. [134] However, there is not much evidence in the hospitals’ archives to suggest this happened: St. Pieter’s Hospital’s portfolio did contain a few life annuities issued by Amsterdam and Haarlem, but these were most likely brought in by corrodians who used these financial instruments to pay their entry sums. [135] The institutions themselves could not invest in life annuities issued by Amsterdam because only persons could be named as annuitants. The hospitals could invest in redeemable annuities issued by Amsterdam, and they did so, but not before well into the sixteenth century. [136]

As an alternative, hospital directors may have invested in provincial annuities (gemenelandsrenten) issued by the county of Holland after 1515. These financial instruments probably came closest to the late-medieval world of high finance and offered investors relatively high returns. Gemenelandsrenten were studied by James Tracy, who compiled a list of large investors living outside and inside Holland, and who had invested in provincial annuities either issued between 1515 and 1532 or from 1542 to 1565. [137] In the first phase, most large investors came from outside Holland, mostly from Flanders and Brabant in the Southern Low Countries. Only five came from the county of Holland, including the Benedictine monastery Egmond and an unidentified hospital called Godshuys van der Lee. [138] Hospitals from Amsterdam do not feature among the large investors in provincial annuities before 1532. This changed in the period starting in 1542, when four institutions were among the large investors. Among them were St. Pieter’s Hospital (investing 3,848 guilders or 10,000 day wages of a master craftsman) and St. Elizabeth’s Hospital (investing 2,025 guilders or 5,000 day wages). Altogether these were sums that middle class individuals could never amass. [139] Also featured on the list of large investors were the directors of Amsterdam’s outdoor poor relief (these huiszittenmeesteren invested 2,904 guilders or 7,000 day wages). The directors of the outdoor poor relief of Haarlem had also invested in provincial annuities amounting to 2,400 guilders or 6,000 day wages). These charities were only responsible for less than 4 percent of the money raised by large investors (see Table 3). Yet, their inclusion in Tracy’s list goes to show that these institutions eventually did participate in the world of high finance by investing alongside the fine fleur of the nobility and wealthy merchants of the Low Countries.

Investors in provincial annuities whose investments exceeded 2,000 guilders, 1515–1565 (in guilders).

| 1515–1532 | 1542–1565 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Value | In percent | Total | Value | In percent | ||

| Total | 22 | 139,035 | 100 | 167 | 771,687 | 100 | |

| From outside Holland | 17 | 126,898 | 91.3 | 96 | 482,828 | 62.6 | |

| From inside Holland | 5 | 12,137 | 8.7 | 71 | 288,859 | 37.4 | |

| Private investors | 4 | 9,737 | 80.2 | 42 | 277,682 | 96.1 | |

| Private investors from Amsterdam | 0 | – | – | 25 | 87,362 | 30.2 | |

| Charities | 1 | 2,400 | 198 | 4 | 11,177 | 3.9 | |

| Charities from Amsterdam | 0 | – | – | 3 | 8,777 | 3.0 | |

Note: Amounts were originally expressed in lb. Hollands of 20 stuivers. Source: Tracy, A financial revolution, pp. 226-251.

When we shift our focus from the large investors to the entire group of annuity-buyers, institutions from Amsterdam do feature, as do those from Delft, only less so. Tracy notices that directors of institutions – who were often connected to the world of high finance themselves – increasingly invested in the course of the sixteenth century. He writes that “burghers charged with responsibility for the town’s widows and orphans were more than willing to entrust endowed funds to these annuities”. [140] Between 1553 and 1565 fifteen Amsterdam institutions invested in provincial annuities (at 1,157 guilders on average or 3,000 day wages). Ten institutions from Delft also bought annuities (at 577 guilders on average or 1,500 day wages). [141] Altogether, in Holland 32 institutions invested in provincial annuities at this time, contributing 28,923 guilders (or 3.7 percent of the annuities sampled by Tracy). [142]

Amsterdam’s St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospitals thus feature among the large investors in provincial annuities that were issued after 1515. They were joined by dozens of other institutions from cities in Holland that invested lower sums. The average sums institutions invested, roughly 900 guilders, equalled well over 2,000 day wages of a master craftsman. [143] Although the exact threshold for investing in provincial annuities is not known, middle-class people were unlikely to get their hands on these financial instruments, because of the sums this would have required and also because they lacked the connections. Investors typically were officials: members of the urban political elite such as town council members, as well as members of the economic elite. Thus, merchants, shippers, drapers and brewers were among the investors from Amsterdam. According to Tracy “drapers occupy the lowest end of the scale among renten-buyers grouped by economic interest”; [144] even though these were usually among the wealthiest entrepreneurs in late-medieval cities. [145] Middle classes were only indirectly represented in the world of high finance through institutional investors such as the hospitals that allowed them to invest in corrodies and life annuities; however, it seems that this was only done towards the midsixteenth century.

7 Conclusion

Even though St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospitals provided financial services, they were probably not yet “institutional investors” in the way Oscar Gelderblom and Joost Jonker have suggested for charities in the early-modern period: late-medieval hospitals attracted real estate, which they either sold for cash or leased out, and they also attracted money. How the latter was precisely reinvested is difficult to say at the present state of research, but with respect to financial instruments it seems that until the mid-sixteenth century hospitals mostly did so by issuing private loans. Hospitals only held a few annuities issued by the city of Amsterdam, which suggests that they did not yet perform the function of bankers for public bodies, as was suggested by Holger Stunz. And it wasn’t until after 1550 when they began to invest in Holland’s state-of-the-art provincial annuities: only by then did the hospitals pool the investments of modest property owners and small savers, bundling these, and placing their money in the world of high finance. This is in line with Gelderblom and Jonker’s claim that “over time these institutions phased out private loans in favour of other, especially securitized, investments”. [146]

Did this matter a great deal? Even before they began to invest in high finance, the hospitals already provided plenty of investment opportunities to the middle class. The directors governed a sizeable portfolio consisting of real estate and financial instruments on the credit side, and, held on the debit side dozens of life annuities and corrodies. I have mainly focused on life annuities and corrodies issued by the hospitals because these provided the investing public with options for life-cycle saving. St. Elizabeth’s and St. Pieter’s Hospitals seem to have upheld low thresholds for investing in pensions that could help support men and women during old age. Corrodies and life annuities required investments in the range of 200 to 500 day wages of a master craftsman. And indeed, among the corrodians and life annuitants, we encounter people who apparently were part of the middle class of Amsterdam’s late-medieval society: they acquired lifelong pensions in money or in kind that may have served them well in trying to prevent impoverishment during old age. To provide this important financial function hospitals did not require access to high finance but drew upon their traditional portfolio based on assets that were to be found in and around Amsterdam.

About the author

Jaco Zuijderduijn is an associate professor at the Department of Economic History, Lund University, Sweden. He published Medieval Capital markets. Markets for ‘renten’, state formation and private investment in Holland (1300–1550) in 2009 and has since published on old age and retirement in late-medieval and early-modern Europe.

Acknowledgement:

The author acknowledges financial support from the Swedish Research Council (project nr. 2017-01857).

8 Appendix

Payment methods for one-person corrodies of St. Pieter’s Hospital (in guilders).

| Total number of contracts | Mean | Median | Spread | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commensalen | ||||

| All contracts | 14 | 67 | 55 | 12-190 |

| Entry sum | 2 | 36 | 36 | 22-50 |

| Entry sum + labour/inheritance | 6 | 45 | 48 | 12-65 |

| Financial instrument | 1 | 80 | 80 | – |

| Financial instrument + labour/inheritance | 2 | 57 | 57 | 24-90 |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument | 2 | 127 | 127 | 65-190 |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument + labour/inheritance | 1 | 151 | 151 | – |

| Incl. real estate | – | – | – | – |

| Proveniers | ||||

| All contracts | 29 | 114 | 100 | 9-340 |

| Entry sum | 7 | 58 | 50 | 9-150 |

| Entry sum + labour/inheritance | 12 | 106 | 100 | 38-200 |

| Financial instrument | 1 | 340 | 340 | - |

| Financial instrument + labour/inheritance | 6 | 130 | 125 | 70-180 |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument | – | – | – | – |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument + labour/inheritance | 2 | 79 | 79 | 58-99 |

| Incl. real estate | 3 | 173 | 60 | 20-340 |

Notes: Commensalen refers to the less-luxurious corrody contracts, while proveniers refers to the more luxurious corrody contracts. One guilder consisted of 20 stuivers. Source: Zuijderduijn, Pap en brood, p. 42.

Payment methods for one-person corrodies of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital (in guilders).

| Total number of contracts | Mean | Median | Spread | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commensalen | ||||

| All contracts | 2 | 25 | 25 | 4-46 |

| Entry sum | – | – | – | – |

| Entry sum + labour/inheritance | 1 | 4 | 4 | – |

| Financial instrument | – | – | – | – |

| Financial instrument + labour/inheritance | – | – | – | – |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument | 1 | 46 | 46 | – |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument + labour/inheritance | – | – | – | – |

| Incl. real estate | – | – | – | – |

| Proveniers | ||||

| All contracts | 12 | 117 | 104 | 40-243 |

| Entry sum | 5 | 75 | 70 | 40-108 |

| Entry sum + labour/inheritance | 5 | 127 | 135 | 67-200 |

| Financial instrument | 1 | 152 | 152 | – |

| Financial instrument + labour/inheritance | 1 | 243 | 243 | – |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument | – | – | – | – |

| Combined entry sum + financial instrument + labour/inheritance | – | – | – | – |

| Incl. real estate | 1 | 85 | 85 | – |

Notes: Commensalen refers to the less-luxurious corrody contracts, while proveniers refers to the more luxurious corrody contracts. One guilder was made up of 20 stuivers. Source: SAAG inv. nr. 7.

© 2025 Jaco Zuijderduijn, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Nachruf auf Wolfram Fischer

- Special Issue Articles

- Investment and Saving Opportunities for Different Socio-Economic Groups in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

- Politics, Investments and Public Spending in Bologna (End of 13th – First Half of 14th Century)

- Financing Poor Relief in the Small Lower Rhine Town of Kalkar in the Late Middle Ages

- Credit for the Poor, Investments for the Rich? Different Strategies for Investing and Saving Money in Medieval Tirol

- Financing the Commune

- Investing in a New Financial Instrument: The First Buyers of Urban Debt in Catalonia (Mid. 14th Century)

- Set for Life: Old-Age Pensions Provided by Hospitals in Late-Medieval Amsterdam

- Credit Investments in Northern Italian States (17th–18th Centuries)

- Research Forum

- Food Crises in Germany, 1500–1871

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Nachruf auf Wolfram Fischer

- Special Issue Articles

- Investment and Saving Opportunities for Different Socio-Economic Groups in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

- Politics, Investments and Public Spending in Bologna (End of 13th – First Half of 14th Century)

- Financing Poor Relief in the Small Lower Rhine Town of Kalkar in the Late Middle Ages

- Credit for the Poor, Investments for the Rich? Different Strategies for Investing and Saving Money in Medieval Tirol

- Financing the Commune

- Investing in a New Financial Instrument: The First Buyers of Urban Debt in Catalonia (Mid. 14th Century)

- Set for Life: Old-Age Pensions Provided by Hospitals in Late-Medieval Amsterdam

- Credit Investments in Northern Italian States (17th–18th Centuries)

- Research Forum

- Food Crises in Germany, 1500–1871