Financing the Commune

-

Carlo Ludovico Severgnini

Carlo Ludovico Severgnini holds a PhD in Medieval History from the universities of Bologna and Paris 1 (Panthéon-Sorbonne) and works as an archivist for the Italian Ministry of Culture (MIC). His dissertation focuses on the connection between financial administration, private capital, and sociopolitical change in Burgundy and Savoy during the 15th century. He has also worked on public finance and archives in late Medieval Italian cities.

Abstract

The connection between public spending and the ambitions of urban elites is a common topic in the historiography of the late Middle Ages. However, it is still unclear how city finances and private capital interacted before the use of sophisticated financial systems of the late 13th to early 14th centuries. The case study of Siena provides an analysis of many different archival sources that date back to the first half of the 13th century. Data show a cycle starting with deficit spending by the city to support the war effort. The deficit was financed by the municipality with large-scale borrowing from wealthy citizens, later repaid with revenues from direct taxes. For the lenders, this was a very low-risk investment that yielded medium-low returns. However, loans to the city were more a political tool to secure a position of power, rather than just an economic opportunity.

1 Introduction

Studies on city finance during the Middle Ages have mainly focused on Venice and Genoa, which had already created a complex system of deficit management in the first half of the 13th century. The system relied on permanent public debt, tax-farming, and consumption taxes and has been regarded as a forerunner of modern public finance. Both cities provided a model for studies on medieval Italian city-states, but similar systems could only be found a century later in large city-states such as Florence (around 1340). As pointed out by Bernadino Barbadoro, Charles-Marie de la Roncière, Maria Ginatempo and Lorenzo Tanzini, the Florentine commune had a very different system in the 13th century, something much less sophisticated than Genoa and Venice. Other city-states in northern Italy (Milan, Asti, Bergamo, Lucca) financed their endeavours with direct taxation and loans throughout the 14th century, just as Florence had been doing in the same period before relying more on tax-farming and indirect taxation. [1]

This second model based on loans and direct taxes proved to be more common during the 13th century, but due to the scarcity of documentary series, scientific literature is quite limited, and we have few details on how this most common system worked. [2] Siena, a Tuscan city of considerable importance during the Middle Ages, offers a privileged point of view because of its rich archives. This article will try to outline the structure of the loans-taxes model and the ratio behind it. I will try to find links between methods for financing the budget and economic-political interests of the urban elite. Also, I will inquire into the relationship between private capital and public institutions: methods of financing municipal budgets can be understood as a means to keep existing power relations, as demonstrated by Ann Katherine Chiancone Isaacs for 14th-century Siena, or they can empower a certain social group, as shown by Christine Meek for 14th-century Lucca. [3] Since public spending was tightly bound to the elite’s ambitions and the problems the city faced, it is necessary to start by framing the topic in the historical context of medieval Italy.

2 Siena: Portrait of a City and Its Countryside

In the 13th century, Siena was a large and rich city with a diversified economy. While the estimated populace counted 15,000 to 20,000 inhabitants in 1250, at the start of the 14th century, the city was home to 50,000 people; Italian metropolises such as Venice, Milan, and Florence had more than 200,000 inhabitants each at this time. [4] There were several towns in the countryside near Siena, such as Poggibonsi, San Gimignano, Montepulciano, Montalcino, San Miniato, Colle Valdelsa, Massa Marittima, Volterra, and Grosseto. Most of them were still independent and had their own district. [5] As for the countryside under Sienese control around 1250, the Chianti area north of Siena was densely populated (with 50 to 60 people/km2), while the Maremma, still covered in swamps, was less densely inhabited (with only 20 people/km2). There was a specialisation in terms of production: grazing lands and fishponds were common in the Maremma, whereas highly productive agricultural activities were typical of more densely populated areas. Northern regions were therefore richer and more populated than the southern ones, where, however, there were several mineral deposits (silver, copper, and iron) and stone quarries. We must also remember that each village organised the surrounding area according to its needs, the quality of the soil, and the crops. [6]

While the countryside was dominated by agriculture, forestry, and animal husbandry, there were many different economic activities in the city. Even if the textile industry (a key sector in many Italian towns) was not highly developed in Siena during the 13th century, it did employ a significant number of both skilled and unskilled workers. One of the most important sectors involved the transformation of animal products (leather production, tailoring, butchery, shoemaking). Toll records and tax assessments also confirm that there were many specialised artisans. The tertiary sector was the most relevant: [7] Siena was an important regional market which had led to the development of banking activities (mainly money exchange and moneylending) thanks also to the availability of silver for minting coins. The institutional apparatus of the municipality, the imperial administration, the bishopric and other ecclesiastical institutions provided the legal structure. In addition to that, a large part of the city’s economy revolved around supplies for the municipality.

According to data available for 1285, there were small landowners, tenants, millers, bakers, barbers, and other essential workers all working for the livelihood of the townsfolk. [8] The elite in Siena was composed of landowners, rich traders, and bankers, and the clear distinction between them and the rest of the population was horse ownership: buying and supporting a horse required great economic means. The elite was so numerous and rich that there were at least 600 fully armoured cavalrymen in the city who could serve in imperial campaigns during the 1230s. [9]

Sienese merchants were already famous for their services. They attended the main fairs in France and Germany as bankers and traders already at the end of the 12th century. [10] The importance of trade for the economy of the city led Ernesto Sestan to depict Siena as “the daughter of the road”. In his opinion, the position of the city on a chokepoint in the road network connecting northern Italy to Rome favoured Siena, since the Roman Aurelia road along the Tyrrhenian coast had lost some of its importance after the devastations during the Greek-Gothic wars. [11] Thus Siena played a pivotal role in ensuring the importance of those segments of the via Francigena. [12]

During the High Middle Ages, central and northern Italy was officially under imperial rule, but it was fragmented into hundreds of small districts governed by seigneurial lords, bishops, and city-states. In the first half of the 13th century, all these cities had two institutional features in common: a foreign judge and military commander called podestà (elected once or twice a year, modelled on an imperial institution established in Italian cities in the 12th century by Emperor Frederick I Hohenstaufen [13]) and two legislative-executive assemblies (a general one composed of all male citizens and a smaller one with only members of the elite). [14] Based on these features, the political system of the Italian cities for this period has been defined by historians as podestarile-consiliare, since the power was shared between the podestà and the councils. [15]

At the beginning of the 13th century, Siena had a foreign podestà, elected once a year, and two assemblies. The general assembly was known as the Consiglio della Campana (Council of the Bell), and every male citizen had a seat; the other acted as a council of state or cabinet and took its name from the number of its members, elected among the citizens. Other core institutions were a group of thirteen so-called wise men whose job was to update the statutes, one camerlengo (treasurer) and four superintendents of finances. [16] Some registers from the 13th century provide annual lists of other regularly elected magistrates, mainly judges, notaries, and overseers. The institutional structure of the commune followed the division of the city nucleus into three terzieri (districts), namely Città, San Martino, and Camollia, which meant the number of these officials was a multiple of three to equally represent the citizenry. There were also tithe collectors and around 50 assistants (balitores) who mainly acted as messengers and law enforcers. Other civil servants of minor importance, as well as military commanders, were not elected but chosen by the magistrate from among eligible citizens. This was the essential administrative structure, but in many cases, citizens elected commissions (balie) to take care of a specific matter, e.g., the recruitment of mercenaries or peace negotiations.

Siena also had several institutions or associations that were expressions of some groups within urban society, for example the societas militum (made up of the richest citizens), the societas populi (made up of those who were not noble), groups belonging to the same church, and guilds. Societates were self-governing communities within cities, and both the podestà system and the associations were solutions to the growing problem of violence and social strife. On the one hand, societates regrouped people who shared the same interests and allowed them to defend themselves against other power groups; on the other hand, the presence of a foreign head of government was seen as a balancing factor to ensure stability and justice, since the podestà was theoretically neutral. [17]

3 Tension Between Political and Economic Interests

Between the 12th and 15th centuries, political factions in Italy were regrouped in two opposing fronts: the Ghibellines and the Guelfs. Being in one of the two parties meant not only taking a stance on problems of high politics (e.g., papal superiority or imperial primacy), but also being part of a complex system of alliances. Dynasties and cities tried to pursue their own interests by relying on imperial armies and administration (the Ghibellines) or papal favours and allies (the Guelfs). [18] As for Siena, the rivalry with Florence (the leading city of the Guelf group in Tuscany) had its roots in the centuries-old conflict for the control of Chianti and in the competition for the management of papal finances. This rivalry pushed Siena to an anti-Florentine policy and, therefore, to closer ties with Ghibelline parties in Italy and with the German emperors.

At the beginning of the 13th century, conflicts among cities in Tuscany revolved around two main alliances: Lucca-Florence (Guelfs) and Pisa-Siena (Ghibellines). The first bloc formed to counter Pisa, which was a centre of trade of great importance and a maritime superpower. In search of an ally, Pisa had to turn to Siena; they were both eager to clash with Florence, which was also constantly fighting against the emperor. Other Tuscan cities (such as Pistoia), big towns, and great seigneurial lords were directly involved in the strife, as were other urban centres in central Italy (e.g., Orvieto and Perugia). [19]

After a defeat inflicted by Florence in 1208, Siena slowly managed to recover its territory and obtained the support of three great dynasties in southern Tuscany (the Ardengheschi, Berardenghi, and Scialenghi). Now, Siena started securing and fortifying its northern border while it clashed with the Aldobrandeschi, a powerful noble family in the south. Siena defeated the clan, but was not strong enough to dominate completely and resorted to diplomacy to control the rest of the Maremma. [20] The Aldobrandeschi dynasty had been an enemy of Orvieto, a city that used to cooperate with Siena until their areas of influence collided: the control of two fortified towns (Chiusi and Montepulciano) on the border became a burning issue with the defeat and submission of the clan by Siena between 1221 and 1226. [21]

In 1229, a part of the elite in Montepulciano was exiled and sought help from Siena, which attacked Montepulciano in retaliation. This caused Florence and Orvieto to intervene against Siena. War raged on for years, and many other cities were dragged into it on both sides (Montalcino, Pistoia, Poggibonsi, San Miniato, Pisa, Lucca). [22] In 1232, Pope Gregory IX (former Cardinal Bishop Ugolino dei Conti di Segni, who had been elected in 1227 and died in 1241) excommunicated Florence and Orvieto because they did not accept a proposal for papal arbitration. Siena called for an imperial intervention against Florence, which had never paid tributes to the emperor. This resulted in a fine of 110,000 silver marks (equivalent to 550,000 silver pounds) plus war reparations to Siena (equal to 600,000 silver pounds). [23] However, the imperial administration never managed to collect such sums, since Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen’s forces were engaged in Germany and Northern Italy to fight the rebellious Bavarian nobility and the Lombard League, a confederation of northern Italian cities that challenged imperial power. [24] Eventually, between 1234 and 1235, peace was negotiated with the intervention of a papal legate, whose decision it was to restore the status quo ante, and Siena was sentenced to pay war reparations to Montepulciano. The commune accepted, mainly because the traders and artisans insisted, under the threat of an insurrection, on obtaining several institutional reforms; the bankers were also warned by the Pope that if they did not comply, all their assets would be frozen. [25]

The fiasco left Siena open to Florentine aggressions due to the incomplete control of Chianti. At the same time, the city had learned that the Aldobran-deschi were a valuable ally against the new enemy, Orvieto. The strategy of allying with smaller cities pursued by Siena proved very successful in exerting influence and preventing raids, which was the most typical feature of medieval warfare and led to the depletion of the countryside. [26] Between 1235 and 1250, Siena became the main imperial stronghold in Tuscany and took part in the ambitious project of subjugating Guelf cities. This implicated Siena in several military campaigns in northern Italy, coordinated by Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen and his vicar for Tuscany, Pandolfo di Fasanella. [27] The presence of imperial administration in the city and Frederick II’s strategy of weakening Florence, were two key factors that led the Sienese elite to support the emperor. The alliance between the city and other imperial supporters opened a cycle of Ghibelline hegemony in Tuscany. The rivalry brought the contenders to war again in 1251, and the conflict ended inconclusively in 1255, paving the way for other military confrontations, culminating in the clash at Montaperti in 1260. [28] Only the intervention of Charles I of Anjou (King of Sicily from 1266 to 1285) brought the Ghibelline dominance in Tuscany to an end in 1266. [29]

4 Public Expenditure: The Road to War

Siena undertook many costly military actions between 1200 and 1255. These exacted a heavy toll on city finances, whose organisation and structure underwent great stress. Paolo Cammarosano argued that Italian comuni inherited and reworked pre-existing Carolingian and diocesan fiscal structures between the late 11th and early 13th centuries, adapting them to new needs, as pointed out by Patrizia Mainoni. In both their opinion, institutional changes were caused by the growth in expenditure (even with periodic and wide fluctuations) for military activity. [30]

This seems to be true for Siena. At the start of the 13th century, the commune had an office (the Biccherna) that operated as a central treasury. It also acted as the board of tax auditors, and was one of the executive branches of city government. [31] The office was already active in 1168 when it worked as a court for tax offences, having partially seized jurisdiction that had belonged to the bishop. [32] Accountants checked the city balance sheets at the end of each month and the five Biccherna magistrates (the treasurer and four superintendents) had to present an audit report to the general council twice a year: once in June/July and once in November/December. Even though many decisions concerning financing methods were made by the cabinet and were only voted in the general council, it can be said that the municipality wanted to demonstrate that everybody was accountable for their choices and that public finances were not a secret to be kept from citizens. It was ideologically important that citizens were informed about the finances of their own commune, but at the same time, the governing elite wanted to ensure that no other group could have a say in these matters and influence the outcome. Therefore, the financial state of the municipality was periodically made public, while some aspects stayed firmly in the hands of a few high-ranking officials. [33]

We can divide the long period between 1200 and 1250 into two segments, the watershed being the apparition of the archival series called Libri di Biccherna. This series is composed of semiannual ledgers. Each ledger consists of three different parts (acquisitiones or revenues; reassignationes or the chief treasurer’s accounting book; and expensae or public expenditure) assembled later in one manuscript. For the early 25 years, we must resort to the so-called Diplomatico, an archival fund that contains various ancient documents and parchments. The selection of these materials made by contemporary administrators and early modern archivists led to the destruction of a large quantity of documents, so what is left gives us a very incomplete picture. [34] The parchments from the Diplomatico and those registered in the Caleffo Vecchio (the liber iurium, a collection of the most important documents of the city) confirm the hypothesis made by Cammarosano and Mainoni: during this time, large amounts of money were spent by Siena on armies and fortifications, both requiring quite expensive logistics. [35] Even smaller conflicts put the traditional financing system under pressure, leading to a constant state of indebtedness of high-ranking officials who borrowed money on behalf of the commune. [36]

If we go over the ledgers, we see that only three items can be listed as management costs, namely the payment of the salaries of foreign magistrates and city officials, the imperial tribute, and the salaries paid to city guards. In the following table, we can see the number of Sienese silver pounds spent on each item every year. [37]

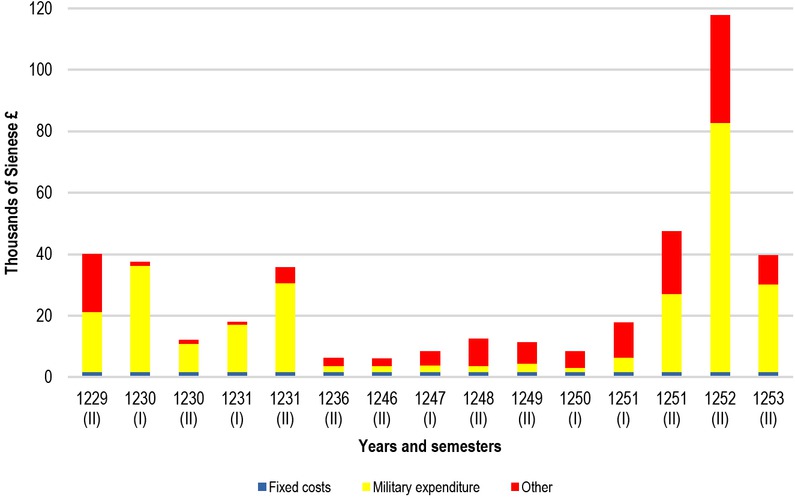

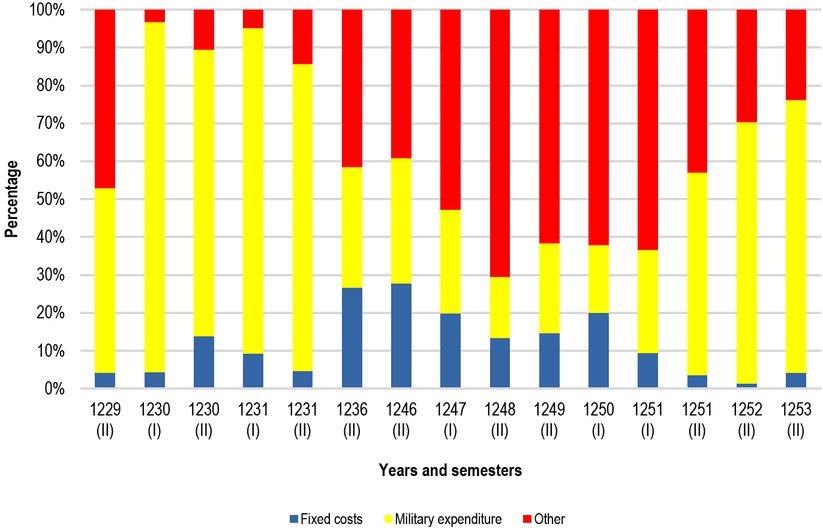

We must split the total fixed management costs into two tranches to appreciate their impact on public expenditure. This is due to the nature of our sources, since each ledger usually covers six months, and we cannot know the overall expenditure for individual years between 1229 and 1253. [38] (see Fig. 1) Generally, the fixed costs were not decisive in the overall expenditure unless the city had allocated very small budgets (it is a matter of mere inverse proportionality). (see Fig. 2).

Municipal expenditure in Siena (1229–1253) (in Sienese £). Note: (I) denotes the first fiscal semester (January to June); (II) denotes the second semester (July to December). Source: LB III-XIV.

Municipal expenditure in Siena (1226–1253) in percent. Note: (I) denotes the first fiscal semester (January to June); (II) denotes the second semester (July to December). Source: LB III-XIV.

Fixed management costs of the City of Siena (c. 1200–1250).

| Item | Annual cost |

|---|---|

| Salaries for magistrates | £2,485 to £2,750 |

| Imperial tribute | £350 |

| Public order | £375 to £400 |

| Total | £3,210to £3,500 |

Note and sources: Salaries for magistrates were at their lowest point in September 1248 and at their highest level in September 1249. The fluctuation is due to the variation of the number of balitores or low-ranking municipal officials. The salary for the podestà usually amounted to £2000 (sometimes less) with which he had to pay for his familia (bodyguards and administrators) as well. See: Direzione dell’Archivio di Stato di Siena (Ed.), Libro dell’entrata e dell’uscita della Repubblica di Siena detto della Biccherna, IX, 1249, Siena 1933, p. 156 (henceforth LB). The Imperial tribute is calculated at the exchange rate of 1 silver mark = 5 pounds. This is confirmed by several documents, among which we can cite ASSi, Diplomatico, Riformagioni, 6. July 1249: Gualtiero da Capua, imperial collector for Tuscany, by order of count Frederick of Antioch, issued a receipt of payment to Incontrato di Tolomeo, camerlengo, and the four provveditori for £350, equivalent to 70 silver marks as the annual tribute owed by Siena. Compiled by Giacomo di Ranieri from Quinciano, notary in Siena; the fluctuation on the public order item is due to small variations in the composition of patrols. There was one patrol for each terziere, formed by 10 guards and a captain.

We can observe a dramatic increase in expenses in the period between 1229 and 1235 (when the first war with Florence and the Guelf coalition were underway) and after 1251 (during the second war with Florence). Those were years of exceptional military effort by the city. The obvious link between conflict and intensification of activity resulted in an increase in the number of people involved and therefore in costs. Moreover, some of the logistics expenses for war probably remain hidden in the expenses (named “Other” in Figure 2), since it is unclear if the share of the expenditure allocated to buy grains (which amounted to some 70 percent of the whole semester) was used to supply troops and garrisons stationed in the countryside or to keep grain prices stable for the citizens. [39]

5 Loans and Regulation

Borrowing money was a constant and considerable means of financing the city and its wars. Overall, loans amounted to 38.8 percent of the total city revenues in Siena between 1230 and 1253. They were also a primary cause of expenditure and stimulated the search for other revenues to cover the costs and reimburse sums when needed.

The preference for loans over direct taxation is not as obvious as it might seem. There were political reasons; indeed, many taxes needed specific conditions to be imposed, and budget law proposals had to be voted by a qualified majority in the General Council. Moreover, collecting taxes required a lot of people, work, and time, which were even more valuable than money during wartime. This leads to the conclusion that through loans, the city could immediately obtain hefty sums that were paid back later using tax money and other resources. [40] The timing of the loans confirms this hypothesis. We often find loans in the ledgers when municipal armies or external military companies were to be paid or hired: this was the case in 1208 and again in 1230/1231, as well as between 1251 to 1253. [41] Thus Siena financed projects through private capital, guaranteeing its access to the much-needed private credit with tax revenues.

Loans were also an emergency measure to cover a budget deficit when necessary. This was a solution for the treasurer to bypass regulations on debt management because statutes included balanced budget amendments. The treasurer and the four superintendents were jointly and independently liable toward the commune. [42]

We must analyse the loans issued to the city in greater depth. Three types of loans can be found in the ledgers: simple and voluntary loans, forced loans, and deductibles. The financial administration used an ambiguous lexicon: we find the word mutuum for every type of borrowing on behalf of the city, whereas prestantia meant both forced and deductible loans. These two categories often overlapped when the interest or total amount of a forced loan could be deducted from taxes owed by that citizen. We can distinguish the different types when we consider factors such as the sums granted, interest rates, and short notes in the ledgers regarding reimbursements or deductions.

Voluntary loans could be taken out without the prior approval of the General Council, but under the supervision of at least two superintendents and the treasurer and later approved by the assembly during the monthly auditing of accounts. [43] The approval of forced and deductible loans had to be voted for up front by two-thirds of the members of the General Council.

Deductible loans were not as important as they later became during the 14th century, and we can see a clear pattern in Table 2: in times of war, the amount of money raised through voluntary loans did not decrease, but forced loans became an important source of revenue. During times without major wars (1236– 1250), the city avoided raising forced loans: they were rarely paid back, and like direct taxation, they were a major factor of dissatisfaction among citizens. While we have no ledgers for the entire period, and only five semesters out of ten are covered for 1246 to 1250, the ledgers show different times of different years, so this proves that ordinary military expeditions did not necessarily lead to forced loans.

Loans taken out by Siena (1230–1250) (in £ and in percent).

| Year | Voluntary loans in £ / in percent | Deductible loans in £ / in percent | Forced loans in £ /in percent | Grand Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1230 (I) | 8,312 | 29.9 | 250 | 0.9 | 19,233 | 69.2 | 27,795 |

| 1230 (II) | 4,146 | 63.1 | 150 | 0.2 | 2,278 | 34.7 | 6,574 |

| 1231 (I) | 107 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 15,600 | 99.3 | 15,707 |

| 1231 (II) | 95 | 0.3 | 411 | 1.2 | 34,334 | 98.5 | 34,840 |

| 1236 (II) | 2,825 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,825 |

| 1246 (II) | 50 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| 1247 (I) | 920 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 920 |

| 1248 (II) | 4,640 | 93.8 | 307 | 6.2 | 0 | 0 | 4,947 |

| 1249 (II) | 3,689 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,689 |

| 1250 (I) | 1,082 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,082 |

Note: The sums do not include interests. (I) denotes the first fiscal semester (January to June); (II) denotes the second semester (July to December). Source: LB III-X.

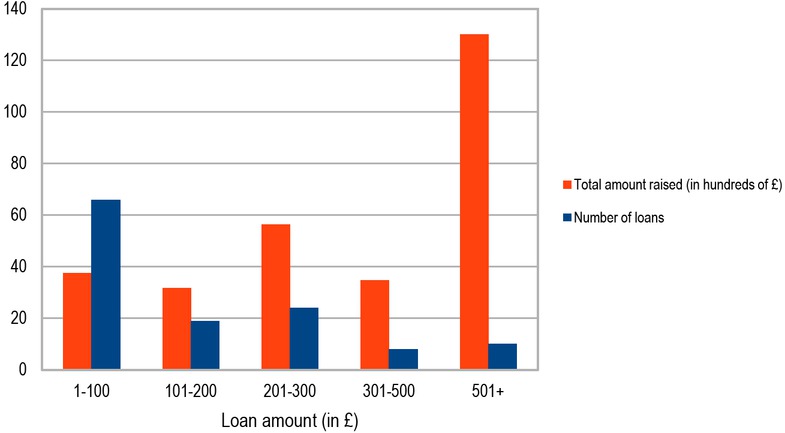

Over this period, voluntary loans amounted to 26.2 percent of total loans, while forced loans comprised 72.6 percent. Interest rates varied, but we can find some patterns. Most forced loans did not bring any interest, as stated in the 1231 ledgers; only a few came with 0.75 percent interest. Voluntary loans had either a monthly interest rate of 1.25 percent or a yearly rate of 12 percent. The lender agreed on the preferred rate with the city officials; the amount of money lent was not a key factor in deciding which type of interest rate was to be applied. Since many registers have been lost, it is impossible to calculate the total interest actually paid by the city.

Number of loans and total amount raised by Siena in 1230–1250 (in £). Source: LB III-X.

The interest rates were strictly regulated in the statutes. In 1226, the treasurer had to swear on the Gospels that he would borrow money only with the help and explicit approval of the superintendents of finances and that he would try to set the interest rate as low as possible. The maximum monthly accepted rate was three denarii per libra, which is to say 1.25 percent. [44] From what we can see, this rule was almost always followed, but no municipal law regulated deadlines: it was very common to defer payments, and that brought additional interests or fines.

The average duration of a loan contract was between three months and one year. Even if it is difficult to inquire about the repayment timeline, it seems that postponement was common both during more peaceful years and wartime. The commune usually paid back half of the loan and deferred the other half to the following year to earn enough time to collect taxes to pay back the rest. As a result, fines had to be paid, and that basically doubled the interest. However, growing interest rates and reliance on loans did not create an irredeemable public debt because the city was able to pay back all the loans during the first half of the century. As a matter of fact, when public coffers allowed it (mainly because of more efficient tax collection and sales of monopoly goods and public land), the commune paid back its debts well before the deadlines, which implied that interests were paid for a reduced amount of time.

We have two good examples of repayment practice. In April 1247, Accarigio di mastro Ranuccio, an artisan, together with Albizo Dietaiuti (a retail trader), lent £720 to the commune, which agreed to pay back the sum plus £24 by the end of June of the same year. However, the lenders received the whole sum and only £22 because they were repaid five days before the deadline. This was also one of the very rare cases where the monthly interest rate was slightly above the accepted maximum (1.67 percent instead of 1.25 percent, so four denarii per libra instead of three). But there were no consequences. In 1249, Bonavoglia di Pietro di Boccia lent £400 to the commune and expected to receive £5 as interest (at 1.25 percent) for one month, but soon after, he received the whole sum plus £3, because the loan was paid back 12 days before the deadline. [45]

6 Middlemen and Credit to the City

Other differences between voluntary and forced loans can be discerned from their management and the creditors. Forced loans were collected by officials appointed specifically to complete the task, and every two weeks, they submitted what they had collected to the central treasury. Moreover, forced loans were usually paid by guilds and other societates that managed the collection as they pleased, as in October 1231 when shoemakers, leatherworkers, and butchers lent £300 (£100 per guild). The two merchant guilds of the city raised £1,000 in forced loans in January 1231, then £18,432 at the beginning of August, and £4,548 between October and November. [46]

Voluntary loans were negotiated and handed over directly to the central treasury by the lender, be it a private citizen or a bank. A good example is provided by the Compagnia degli Ugolini (a banking company set up by Risalito di Giovanni, Bartolomeo Bruni, and Uberto Ugolini), which the central treasury treated in the same way as any other private lender. [47] Between 1200 and 1250, we find only one mention of a private bank involved as an intermediary between the commune and creditors. This happened in 1248, when the Marchesello bank run by Giacomo di Marchesello and Bonavoglia di Pietro di Boccia received a payment due by the commune, which had asked the bank to find and pay for a company of mercenaries. The loan amounted to £500, and the bank charged £15 for all the services, which makes it impossible for us to understand the interest rate. [48]

After 1251, the city changed its approach to private credit and started to rely more on private banks as treasurers and intermediaries. This is due to the same reason why the commune had employed the Marchesello bank: enlisting groups of mercenaries around Italy and paying for them was done both through ambassadors appointed by the General Council and through merchant-bankers, who had extensive networks of valuable acquaintances and sometimes branches or company partners in other cities. From 1251 onwards (when war with Florence broke out), there was a sharp increase in the number of times and the amount of money managed by bankers. Another change was the relaxation of council control over the choice of the bank, which was passed over to military commanders. [49]

All loans were provided by Sienese citizens: it is worth stressing this point because it highlights the great financial power of the municipal elite, who was able to raise large quantities of money. Big lenders were few, and between 1226 and 1250, they all held political roles. Their services were so important that the coinage reform of 1250 was carried out by a special commission composed of all major lenders. [50] Giacomo di Marchesello was maybe the most active banker-politician. He started as a grain supplier in 1230, then was elected to oversee roads in 1236 and public works in 1246. The year after, he appointed every special commission in Siena and in 1250, organised tax collections, while lending almost £1,000 to the city over three years. [51] Very similar careers were those of Bonavoglia di Pietro di Boccia, Turchio Chiarmontesi, Giacomo Lupi, and Ranerio Folcalcherio. Each of them lent over £400 to the city over a very short period and held important offices such as the siniscalco (the administrator of public domain land) and the consul mercatorum, the head of the most important merchant guild. Members of even more important and richer families, such as the Bonsignori and the Tolomei, were always either tax assessors or treasurers. As pointed out by Cosimo Cecinato, for the second half of the 13th century, the number of big lenders that later became highranking city officials was strikingly high. The symbiosis between the financial elite and municipal institutions granted the commune easy access to credit; the actual costs (i.e., interests and repayments) fell onto others through taxes and fees. [52]

However, this did not alienate small business owners and artisans, who provided almost all the loans worth £100 or less (60 loans out of a total of 66, used by the municipality to cover small expenses, mainly military equipment and other supplies such as paper, leather, wood, wheat, and candles) during the period under study. The reasons behind this economic behaviour might be connected not only to a good and immediate investment opportunity for the artisans (as happened in the case of Albizo Dietaiuti and Accarigio di mastro Ranuccio in 1247), but also to career opportunities as suppliers for the city and as city officials. A good example might be Fine Martini, a barber: he lent £45 in 1231 and in 1236 he was appointed city manager of the revenues of oil and salt together with Parabuoi, another artisan who had lent £50 to the city. In 1248, both were elected tax assessors together with other major lenders. [53] However, the number of artisans who held a public office or supplied goods to the municipality because of personal involvement in the credit market is low: only ten people can be identified over 25 years, and the most successful politicians among them were Fine Martini and Parabuoi. The other eight artisans supplied small amounts of wheat and iron tools for a few pounds (at between £5 and £20), but none of them received a permanent position with the municipality.

Big financers’ patronage remained more important than petty moneylending to obtain good economic opportunities provided by the commune. For example, Mariano di Genovese operated a small bookbinding business and became the only supplier of paper and parchment for the commune after he prepared some books for Giacomo di Marchesello and Giacomo Lupi in 1246, an act that turned him into a rich paper trader. His turnover and profit margins increased sharply over five years, reaching several hundreds of silver pounds in 1250. [54]

7 Re-Financing the Deficit: Old Problems, New Solutions?

As we have seen, loans covered deficit spending and were funded through several sources of income, state-owned resources, and taxes. Table 3 provides more details about the city of Siena’s revenue characteristics.

Types of municipal revenues of the City of Siena, c.1250.

| Type | Revenue |

|---|---|

| Tributes | Fodrum (formerly a tribute for the imperial army, then a seigneurial tribute usurped by Siena) |

| Censum (fixed tribute from subject communities and religious institutions) Adiutorium (tribute levied for war or public works) | |

| Judicial fees | Fines |

| Fees | |

| Salt | |

| Oil | |

| Monopoly | Divieto (grains) |

| Seignorage | |

| De treccolis (business licence needed to set up a shop in public spaces) | |

| Permits | Infulatio (licence needed to become a balitor) |

| New citizenships | |

| Other licences Datium (distribution tax on citizens) | |

| Datium villanorum (poll tax in the district) | |

| Cavallata (war tax) | |

| Direct taxes | Imposita (distribution tax on subject communities) |

| Assenza (previously a fine, then a war tax for people who refused or were not able to join the army) | |

| State properties | Sales |

| and rights | Contracts and rentals |

Note: On the Fodrum tribute, see: Redon, L’espace, p. 113 and map number 3. Source: LB III-XIV; C. Cecinato, L’amministrazione finanziaria, pp. 164-235.

This revenue structure was the result of a long process that involved the appropriation of public rights by the commune, the imposition of new types of taxes, and the legitimation of these operations. The process took almost a century: on the eve of the 12th century, the commune was not the only public authority; it managed to dominate in the city after conflicts with the bishop, who had almost all the public rights in the area. As a result, by the end of the same century, most rights, responsibilities, and revenues passed into the jurisdiction of the commune. [55]

After the establishment of the commune as the main public authority, the first turning point was the war with Florence (1207–1208): Siena was defeated and forced to pay punishingly high war reparations. In addition, many castles on the border with Florence had been destroyed and required costly repairs. The large quantity of money needed highlighted the inadequacy of municipal revenues, which relied on loans, tributes, and state rights. Extraordinary war taxes (cavallata and assenza) could grant thousands of silver pounds (normally some £8,000 could be raised with one cavallata), but they were highly unpopular, and their collection required months. [56]

According to the sources, a new tax system, the lira, emerged at the end of 1208; it had been set up as an extraordinary measure between 1168 and 1175 (and from 1202 on, if we believe the anonymous author of the Cronaca Senese written in the late 14th century). The lira was an assessment instrument of the wealth owned by a citizen. [57] To simplify such a complicated calculation method that was also frequently subject to changes, it can be said that all householders declared to a city clerk the estimated value of their possessions and the declared sum was used to calculate the amount of money owed to the city. It was done by multiplying the tax rate by the value of the lira, which was expressed in Sienese pounds. For example, if a person had a lira of £100 and the tax rate amounted to 6 denarii per pound (equivalent to 2.5 percent), the citizen would have had to pay 2 pounds and 10 solidi (shillings).

The financial law of 1208 mentioned the expected revenues from various subjects and the basic rules on how to collect them. Although it was created to repay war debts, the lira was found again in a statutory document in 1226 with detailed instructions on how to evaluate both liquid assets and real estate to determine the total fiscal capacity of a subject or institution. [58] The lira quickly became the most common way to levy direct and proportional taxes based on wealth. Proportionality played a significant role in the construction of city identity and the consolidation of municipal governments throughout northern Italy: sharing fiscal burdens more equally (which meant according to one’s wealth) made it easier for the commune to ask for more funding, and tying citizenship to the privilege of proportionality created a separation between citizens and peasants. [59]

Several direct taxes were calculated with the lira system in Siena. Among these, the distribution tax (datium) was the most common, and it was imposed when necessary (even several times in one year). It can therefore be considered an extraordinary direct tax. Examples can be found in 1251, when the city decided to impose the datium three times with three different rates for a total interest rate of 1.5 percent; by the end of the year, almost £25,000 were raised this way. [60]

Another extraordinary direct tax was the imposita. This tax was imposed on the domains directly controlled by Siena and was not calculated using the lira system. The city tasked this collection drive to the communities, but kept the right to set the tax rate, which amounted to either 10 or 20 solidi (shillings) per tax unit (called massaritia). As an example, we have data from a 10 solidi massaritia in 1253 that amounted to £3,500. Since the imposita was extraordinary, it was often justified with the necessity of renovating public works in the vicinity of the paying communities. [61]

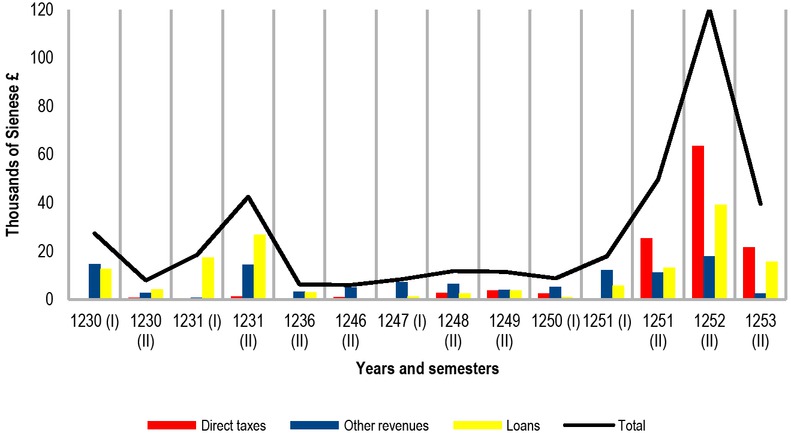

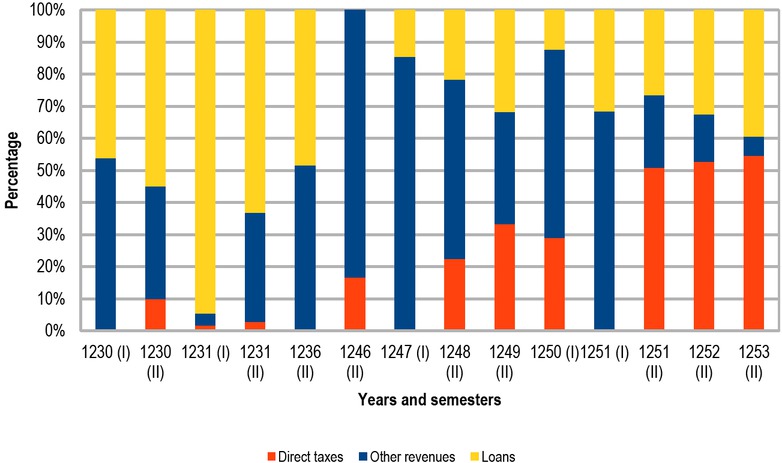

Over the period under study, outsourcing and tax-farming were not as widespread as they would become during the 14th century. We find evidence of the outsourcing of mills in the countryside, fishing rights, and woodcutting, but the semiannual income from these sources was below £2,000. Selling rights and land (mainly swamps and woods) was another common way to pay unexpected expenses, even though it did not garner the large quantity of money needed. [62] While these measures could provide certain amounts of money, direct taxation was the most important revenue source, and the city relied on it to cover loans and pay other expenses (as shown in the following figures 4 and 5).

Municipal revenues in Siena 1230–1253 (in Sienese £). Note: (I) denotes the first fiscal semester (January to June); (II) denotes the second semester (July to December). Source: LB III-XIV.

Municipal revenues in Siena 1230–1253 (in percent). Note: (I) denotes the first fiscal semester (January to June); (II) denotes the second semester (July to December). Source: LB III-XIV.

8 Conclusions

As far as we can tell, the commune made extensive use of private credit throughout the first half of the 13th century as a preferential method to pay large expenses, all related to the increased cost of war. Loans were a very efficient way to raise hefty sums in times of need (such as wartime). Clear patterns can be recognised from the data analysis: loans and extraordinary direct taxation were not mutually exclusive, and the latter was used to cover the costs of the loans. Credit seemed to stimulate the search for other revenues through direct taxation.

The role played by guilds and especially the merchant community in Siena was of paramount importance: not only did the merchant community provide personal connections to important banks and other investors, but it also acted as a primary source of loans and it proved to be an organisation capable of managing and collecting substantial sums of money in short periods of time.

As for the investors’ motivations, we can say that the return on investment of voluntary loans was as high as possible, while complying with laws on usury, but the elite in Siena could find better economic opportunities. However, lending money to the city was a safe investment and the main method to get into the administration, secure a political career, and shape municipal policies. Another category of investors involved in lending money to the municipality, i.e., artisans and small business owners, took advantage of the opportunities of providing smaller loans created by minor deficits to increase their wealth in a safe way and possibly to secure lesser positions of power.

It is no surprise that the elite in Siena tried to keep a position of power through the management of both public finances and the credit market for public institutions. James Tracy claimed that “cities that created long-term debt by consolidating forced loans were cities that claimed to have governments that ruled in the interests of all members of the commune. Though such claims may not stand up very well after an examination of the struggles for wealth and power within each city, they amount nonetheless to a kind of legitimacy. […]. But at this point, the discussion of urban finance merges into a larger discussion of the history of the cities themselves”. [63] As for Siena, the consolidation of forced loans happened later in the 14th century, with two major reforms in 1363 and 1382: during the 13th century there was no need for financial instruments such as annuities. However, the predominance of short-term borrowing did not exclude artisans and small owners from that market, which reinforced the widespread idea that the republican form of government with a foreign head of State could ensure everyone’s safety and wellbeing. [64] Nonetheless, public institutions were always and almost completely in the hands of the same families that could afford to finance the city, and their – albeit more substantial – loans in turn were reimbursed with taxpayers’ money.

About the author

Carlo Ludovico Severgnini holds a PhD in Medieval History from the universities of Bologna and Paris 1 (Panthéon-Sorbonne) and works as an archivist for the Italian Ministry of Culture (MIC). His dissertation focuses on the connection between financial administration, private capital, and sociopolitical change in Burgundy and Savoy during the 15th century. He has also worked on public finance and archives in late Medieval Italian cities.

© 2025 Carlo Ludovico Severgnini, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Nachruf auf Wolfram Fischer

- Special Issue Articles

- Investment and Saving Opportunities for Different Socio-Economic Groups in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

- Politics, Investments and Public Spending in Bologna (End of 13th – First Half of 14th Century)

- Financing Poor Relief in the Small Lower Rhine Town of Kalkar in the Late Middle Ages

- Credit for the Poor, Investments for the Rich? Different Strategies for Investing and Saving Money in Medieval Tirol

- Financing the Commune

- Investing in a New Financial Instrument: The First Buyers of Urban Debt in Catalonia (Mid. 14th Century)

- Set for Life: Old-Age Pensions Provided by Hospitals in Late-Medieval Amsterdam

- Credit Investments in Northern Italian States (17th–18th Centuries)

- Research Forum

- Food Crises in Germany, 1500–1871

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Nachruf auf Wolfram Fischer

- Special Issue Articles

- Investment and Saving Opportunities for Different Socio-Economic Groups in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

- Politics, Investments and Public Spending in Bologna (End of 13th – First Half of 14th Century)

- Financing Poor Relief in the Small Lower Rhine Town of Kalkar in the Late Middle Ages

- Credit for the Poor, Investments for the Rich? Different Strategies for Investing and Saving Money in Medieval Tirol

- Financing the Commune

- Investing in a New Financial Instrument: The First Buyers of Urban Debt in Catalonia (Mid. 14th Century)

- Set for Life: Old-Age Pensions Provided by Hospitals in Late-Medieval Amsterdam

- Credit Investments in Northern Italian States (17th–18th Centuries)

- Research Forum

- Food Crises in Germany, 1500–1871