Investing in a New Financial Instrument: The First Buyers of Urban Debt in Catalonia (Mid. 14th Century)

-

Laura Miquel Milian

Laura Miquel Milian is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Medieval History and Historiographical Sciences and Techniques at the University of Valencia. Previously, she has been a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Barcelona (2020–2021) and the University of the Basque Country / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (2022–2023). She holds a PhD in Medieval History defended in 2020 at the University of Girona. She has been a visiting scholar at the universities of Oxford (2017), Heidelberg (2018), and Ghent (2023). Her research focuses on public finances and local governments in the Late Medieval Crown of Aragon, with recent attention to the emergence of public banks and the connections between them., Albert Reixach Sala

Albert Reixach Sala is a Ramón y Cajal postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Geography, History and History of Art of the University of Lleida. He is member of the research group ARQHISTEC (Food economies…, SGR 2021 SGR 01607). He is co-IP of the collective research projects MortalitasMortality crises in the northwestern Mediterranean, 11th-16th centuries.. . (PID2023-151785NB-I00) and IlerCriSanThe social dimension of health crises in Lleida and its region in the European context: from the Black Death to COVID-19 (2023CRINDESTABC). He holds a PhD in Medieval History defended in 2015 at the University of Girona. He has been a visiting scholar at the universities of Ghent (2013), Laboratoire de Médiévistique Occidentale de Paris (LaMOP) of Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (2019), Utrecht University (2023), and Heidelberg University (2024). His research explores the economy, society, and local institutions of the Late Medieval Crown of Aragon, with a recent focus on epidemics and the institutional responses to them.Pere Verdés Pijuan is a Senior Research Fellow at the Spanish High Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) since 2005. From 2008 to 2024, he has been Principal Investigator of five national research projects funded by Spanish Government, and one international project funded by the CSIC with the French CNRS about the origins of public debt in Mediterranean Europe (12th to 16th centuries). Among others, he is currently member of the Steering Committee of theArca Comunis Research Network on the history of medieval and modern taxation, Associate member of theCentre Toulousain d'Histoire du Droit et des Idées Politiques (CTHDIP) of the Université Toulouse I Capitole, and Editor of the scientific journalAnuario de Estudios Medievales . His research focuses on public finances and local governments in the Late Medieval Crown of Aragon, with recent attention to the economic, social and political repercussions of financial and fiscal policies of urban authorities.

Abstract

This article consists of a systematic analysis of a large sample of the first purchasers of annuities issued by the urban governments of Catalonia between the years 1313 and 1367. Based on preliminary literature on the subject, it gathers, describes, and contextualizes, both from the point of view of the fiscal and financial development of the Crown of Aragon as a whole and from a more local perspective, unpublished references to operations of this type from the beginning of the 14th century. In the second part, it analyses a sample, based on unedited data as well as specific studies, of 1,399 annuities sold by eight urban centres between the years 1330 and 1367 (the settlements are in different parts of Catalonia, ranging from big cities like Barcelona or Girona to small towns). These operations are examined according to their chronology, features of contracts and interest rates. Moreover, their buyers are also studied in light of their gender, socioeconomic status, and place of residence. The first purchasers of public debt in Catalonia appear to have been speculative investors, attracted by a financial product that, while lacking complete security, offered high interest rates and the theoretical promise of recovering the capital upon repayment of the credit.

1 Introduction

In 1348, the fear provoked by the Black Death prompted Blanca de Calders to make a will. She was a noblewoman of modest lineage, but she had had an intense life and accumulated an important fortune. Married twice, in 1313 she was appointed lady-in-waiting to the Infanta Isabella of Aragon, whom she accompanied after her marriage that year to Frederick the Fair, Duke of Austria. She remained in Germanic lands until 1318 and, on her return, she entered into various disputes over feudal rights and carried out economic transactions that brought her large sums of money. [1] With this capital, she began to invest a considerable part of this money in a very unusual type of financial product at that time: annuities issued by local communities. At the beginning, during the decade of 1320, she invested mainly in life annuities (violaris) for a volume of money that we cannot specify and at a probable interest rate of 14.28 percent. Or, during the decade of 1330, she preferred the purchase of perpetual annuities (censals). As we shall see, these types of annuities still aroused the suspicion of theologians, some of whom considered them a usurious practice. However, Blanca de Calders had no qualms about buying (at least) four censals worth 84,000 solidos from Barcelona (henceforth s.b.) which, at an interest rate of 7.14 percent, provided her with a yearly yield of 6,600 s.b. [2] All these annuities were acquired from communities of different sizes (Cervera, Tàrrega, Verdú, and Montornès de Segarra), which were quite distant from her places of residence, Barcelona and Terrassa, and located in a specific area of the western half of Catalonia. Without direct descendants, the noblewoman foresaw in her will that these incomes would end up being bequeathed to the Carthusian monastery of Sant Jaume de Vallparadís, founded by herself in 1344 in Terrassa. Among the executors in charge of ensuring that her will was carried out was the famous Dominican friar Bernat de Puigcercós, known – among many other things – for a treatise that denied the usurious nature of the censals. A close relationship must have united both actors, since she also bequeathed to him 500 s.b. per year throughout his life. This clause, however, would never be executed, since both were recorded as deceased in 1349, probably victims of the plague. [3]

This short biographical sketch serves to introduce the subject studied in this article. It is one of the earliest known episodes on municipal debt issuance in the form of life and perpetual annuities (violaris and censals). [4] These titles were acquired by a noblewoman who, despite her modest lineage, was closely linked to the royal entourage and, in addition, had the opportunity to travel around Europe. Blanca de Calders also had a close relationship with Bernat de Puigcercós, a leading intellectual who had studied in Paris and/or Cologne and was also well connected to the country’s political elites. [5] Finally, it should be noted that many of these annuities were issued in the area near the town of Cervera, precisely where Puigcercós conducted the survey included in the early treatise he wrote to deny the usurious nature of the censals. [6] Are we facing simple anecdotes, mere coincidences, or are they significant clues to explain the birth of an economic phenomenon – public debt – which would mark the history of Catalonia and also of the Crown of Aragon?

In the following article we will provide some information to answer this question. To do so, we will focus on the analysis of the first great wave of annuity issues by the Catalan public institutions, specifically by the municipalities, between the years 1313 and 1367. The choice of this geographical space and period are not arbitrary. As is well known, Catalonia was, from the middle of the 13th century, one of the four peninsular territories that, together with Aragon, Valencia, and Mallorca, formed the Crown of Aragon. These territories, united under the same monarchy, were politically autonomous, and the principality of Catalonia had assumed the main role in the first Mediterranean expansion of the Aragonese crown. The city of Barcelona and the municipalities of the royal domain also played a special role in it. During the first half of the 14th century, the prominence of the Catalan cities continued to be evident and, therefore, it is logical that they were at the forefront of the political and financial innovations that took place at that time. These innovations were accelerated by the spiral of war that began, above all, after the conquest of the island of Sardinia (1323) and influenced by some important critical junctures such as the famine of 1333–1334 or the Black Death. It is in this precise context that the beginning of the municipal public debt in Catalonia is documented, which we place between 1313 and 1367. 1313 is the year in which, as we will see, our research has detected the first sale of a life annuity (violari) by a town in Catalonia; 1367 is the last year before the institution emanating from the general assemblies of the estates, the Diputació del General, began to issue debt titles itself on behalf of the whole political community of the Principality.

The first part of our article is devoted to observing the general context in which this wave of issues took place: when this form of public debt appeared and what its origin might have been; what the first issues were and how they were consolidated within the municipal treasury, and how the doubts and problems posed by this financial instrument were overcome before the appearance of a sovereign debt. The second part of this study analyses a significant sample of annuities sold by Catalan cities or towns, small towns, and villages, [7] located in different areas, between 1313–1367: on the one hand, the sales themselves (chronology, types of titles, and interest rates); on the other hand, the buyers (gender, social status, place of residence, etc.) who ventured to purchase this novel and uncertain financial instrument. Some concluding remarks will examine how the findings fit into the wider European context.

2 The Origins of Public Debt in Catalonia

As it is well known, the sale of life and perpetual annuities by urban authorities was not unique to Catalonia and the Crown of Aragon. From the beginning of the 13th century, the towns of northern France regularly resorted to the sale of annuities to finance their needs, although recourse to this form of credit diminished in this territory during the 14th to 15th centuries. The creation of annuities is also documented in the cities of the counties of Flanders, Holland, Burgundy, and the lands of the Holy Roman Empire during the 13th century, where the issuance of life annuities and perpetual annuities by local authorities, in contrast, increased during the 14th to 15th centuries. [8] In the Low Countries, there is even evidence of the sale of annuities, jointly, by leagues of cities or by the assemblies of states during the 15th and 16th centuries. [9] For all we know, life or perpetual annuities were not used by the urban authorities of other European territories until the end of the 15th century. [10] Regarding the Italian cities, they resorted to other forms of long-term public debt to obtain liquidity. [11]

In light of the available studies, it is not yet possible to establish a genealogy between the various forms of annuity documented between the 13th and 15th centuries in western Europe. The syntheses or collective works on the subject of the origins of public debt have limited themselves to pooling the data available for some territories, but a comparative study of the nature and legal characteristics of the various debt instruments is lacking. [12] In the specific case of Catalonia, we have no evidence of a possible filiation with respect to other territories. The trip to the Germanic lands by Blanca de Calders, the presence of Bernat de Puigcercós in Cologne, and the suggestive hypothesis of a possible transmission of models to the south is, for the moment, mere speculation. The only thing that seems clear, both in Catalonia and in other territories, is the existence of various forms of consignment or sale of life or perpetual annuities mortgaged on certain properties or incomes. In the Catalan case, for example, we document from the 13th century onwards individuals selling annuities on real estate in exchange for a certain amount of capital, or lords doing the same on their domains or feudal rights. Among the latter was the monarchy, which often also assigned annuities on its ordinary income to people in its entourage for different reasons. However, there are no studies on these first consignments or sales of annuities that show the phenomenon in any detail or that would allow us to establish a direct and evident link between this practice and the first annuities created collectively by local communities from the 14th century onwards. [13]

2.1 The First Documented Annuities

Here, it is worth remembering that in Catalonia local communities had hardly any territory or private property. Initially, moreover, their fiscal autonomy was very limited, being reduced only to the collection of levies (talles) among their citizens or of some rights ceded or authorized by the jurisdictional lord, including the monarchy. Consequently, the financial capacity of the first municipalities was usually limited to recourse to short-term loans or advances. This debt, floating or short-term, was provided by members or institutions of the community itself, by money changers, and, above all, by Jews, at high interest rates. [14] Until the middle of the 14th century, only in exceptional cases is the creation of life or perpetual annuities by or with the participation of municipal authorities documented, without many specifications. As a result of a first qualitative approach, here are some illustrative examples.

The oldest documented case so far is that of the small town of Fraga, located in the kingdom of Aragon, but very close and closely linked to the Catalan city of Lleida. In 1309, the lord of the place, Guillem II de Montcada, sold to the local council of Fraga a part of the levies paid each year by the town and its surrounding settlements to finance their participation in the crusade led by King James II against Almeria. Specifically, Guillem sold them 1,500 solidos from Jaca (henceforth s.j.), corresponding to the tribute of the questia (direct tax), in exchange for 15,000 s.j. According to the available documentation, at least part of the money was obtained through the sale of censals by the council to inhabitants of Fraga itself (100 s.j. per year) and the city of Lleida (400 s.j. per year) at an interest rate of 10 percent. [15]

According to consulted sources, a few years later, in 1313, the universitas of Tortosa sold two life annuities (violaris) with an expected duration of two lives each. The buyers were Pere Calvet, a royal official and citizen of Barcelona, and Bernat Gras, a cloth merchant from Lleida. The former acquired a rent of 1,500 s.b. per year and we know of its existence thanks to the royal order that authorized the veguer (jurisdictional officer) of Tortosa to act against the said universitas and its members in case of non-payment. The document does not mention the sale price, but indicates that the capital would be charged on the rights of the city’s bridge, as well as on all the goods and revenues of the community and each of its members. [16] For his part, Bernat Gras bought 500 s.j. and we know about the transaction thanks to the document of amortization of the credit, dated at the end of 1326. This document indicates, among other things, that the sale price in 1313 was 3,000 s.j. (16.66 percent) and that the contract was divided into two parts, to be paid as long as four inhabitants of Lleida lived. [17]

The following significant example corresponds to the aforementioned town of Cervera. At an undetermined date, prior to 1332, the authorities of this small town sold five violaris to citizens of Lleida, which totalled 2,600 s.j. of annual rent, at an interest rate of 14.28 percent and a total value of 18,200 s.j. While the precise date of the creation of these initial annuities remains uncertain, it is pertinent to wonder whether they were established a decade earlier in response to royal demands for the Sardinian conquest. The next issue by this urban community took place during the biennium of 1332–1333 and consisted of the sale of another five violaris, also at 14.28 percent, for a value of 63,000 s.b. On this occasion, the capital obtained was used to repay the usurious loans contracted with Jews, as well as to amortize the old violaris sold in Lleida, and to pay other community expenses. Four of these instruments were sold to creditors in Barcelona and the fifth to a resident of Cervera itself. Thanks to this issue, recorded in the municipality’s proceedings and ledgers, we can reconstruct in detail the whole process of sale of these first municipal annuities, which included: municipal agreement, creation of solicitors, recourse to brokers, royal authorization, notarial registration, jurisdictional obligations, etc. [18] Finally, it is worth noting that during the years 1334–1335 the issue of seven other annuities is documented: three new violaris and four censals morts, which are the first perpetual annuities known for Cervera. Although it is not explicitly stated, the date of the new issue allows us to deduce that it was motivated by the important donation granted to the king in 1333 for the war against Genoa and Granada. As for the characteristics of the instruments, the three violaris were sold at l4.28 percent interest and the four censals at 7.14 percent. Two of the violaris were bought by citizens of Lleida, who paid 2,800 s.j. for the contracts, and another by a money changer from Barcelona, who paid 3,500 s.b. As for the four censals, three of them were also purchased by citizens of Lleida, who paid 56,000 s.j., while the fourth was bought by the aforementioned Blanca de Calders for 42,000 s.b. Thus, the number of annuities sold by this Catalan small town up to 1335 amounted to 13 violaris and 4 censals, which provided 87,000 s.b. and 98,000 s.b. respectively. This significant accumulation of obligations ended up provoking the first financial crisis of Cervera, as can be seen in a royal disposetion, dated 21. June 1336, in which Peter the Ceremonious recognized that the local community was oppressed (opressa) by the payment of rents and the repayment of loans to Jews and Christian financers. [19]

The last example we would like to mention is that of Montornès de Segarra. This village (less than 100 hearths) was located very close to the aforementioned Cervera and belonged to the military order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem. Thanks to the important collection of parchments that have been preserved, we can observe in detail its precocious recourse to the sale of annuities. During the 1320s, the community authorities repeatedly took out Jewish loans to obtain amounts that never exceeded 1,000 s.b. and paid interest – recognized in the documentation – that ranged between 10 to 20 percent. In 1330, however, they sold a violari of 1,000 s.b. of pension and 7,000 s.b. of capital (14.28 percent) to Ramon Pallarès, a citizen of Barcelona. This annuity was to last for two lifetimes and was guaranteed with “all the goods of the universitas and its members”. [20] In 1331 they sold another violari, also for two lives and with the same guarantee, to Ramon de Tarroja, neighbour of Guimerà, who paid 1,500 s.b. for an annual rent of 250 s.b. (16.66 percent). Between 1333 and 1334 another violari is documented for two lives of 1,055 s.b. per year bought by Bernardó Pere, a neighbour of Cervera. On this occasion, we do not know the capital loaned, but we do know that it must have been used to pay the donation made by the order of the Hospital for the war of Granada. Finally, in 1336, the authorities of Montornès sold to the noble Blanca de Calders the perpetual annuity (censal) already mentioned in the introduction for 8,400 s.b. and at 7.14 percent interest. This sum was used to amortize the first violari sold in 1330 and the remaining money served to buy wheat. After 1336, more Jewish loans are documented, as well as the payment of rents, which in some cases coincide with those listed above and in others do not. [21]

Besides the aforementioned examples, the approach to the first annuities issued by local communities (autonomously or along with their lords) has allowed us to identify instruments or simply the payment of interests for annuities in Vallespinosa (censal, 1324), [22] Els Alamús (censal, 1327), [23] Reus (violari, 1332), [24] Santa Coloma de Queralt (violari, 1332), [25] Pontils i Selmellà (violari, 1332), [26] Palau d’Anglesola (violari, 1334), [27] les Borges Blanques and some nearby places (violari, 1335), [28] Os de Balaguer (violari, 1336), [29] Valls (violari, 1337), [30] Savallà and some nearby settlements (violari, 1338), Granyena de Segarra (violari, 1338), the town of Igualada (violari, 1338), [31] l’Ametlla de Segarra (violari, 1338), [32] the towns of Cervera (violari, 1339), [33] and Puigcerdà (violaris, 1340), [34] the village of Santa Pau (1340), [35] the town of Balaguer (a violari and a censal, 1341), [36] and the cities of Lleida (1341), [37] and Tarragona (censal, 1342). [38]. During the 1330s, we have also been able to document at least four violaris paid by the Jewish community of Barcelona. [39] Furthermore, it should be noted that, before 1340, various annuities are also documented in the Kingdom of Aragon, many of them bought by Catalan creditors. Specifically, in addition to the aforementioned censal from Fraga (1309), references to censals have been found in Almudévar in 1324 and by the Jewish aljama of Zaragoza in 1326. [40] Additionally, there are records of annuities sold by the universitas of Peralta de Alcofea in 1333 (to a citizen of Lleida, at 16.66 percent interest) and by the universitas of Teruel in 1334. [41] Finally, it is also worth mentioning the early example provided by Monroyo and its villages, where a significant financial operation was documented during the 1340s to reduce communal debt. This debt had likely been incurred during the 1330s with creditors from the city of Lleida through the sale of annuities at 16.66 percent interest. The annuities were redeemed with the proceeds from 18 annuities sold to citizens of Barcelona at an interest rate of 14.28 percent. [42]

We have not yet been able to analyse in detail all of the aforementioned rents, but the information provided by the simple search carried out allows us to already observe some striking features. As for the type of instruments, it seems that initially the violaris were the most common type of rent, at an interest rate that ranged between 14.28 and 16.66 percent. Except for the early case of Fraga, the censals proliferated later and their usual interest was 7.14 or 8.33 percent. A comprehensive study highlighting the level of integration of financial markets at the stage we are analysing is still pending. However, in the absence of more data, this coincidence of interest rates in different areas seems a clear indicator of this integration, at least within Catalonia and, in part, in relation to other territories in Aragon or even in the northwest Mediterranean.

Regarding the places that sold these titles, it is striking that many of them are small communities of limited or scarce size. Only Tortosa, Cervera, Puigcerdà, Balaguer, Lleida, and Tarragona can be considered important urban centres. As we shall see, the case of Barcelona must also be highlighted since the first initiative of the local authorities to sell violaris there is documented in 1333. Specifically, that year, royal permission was obtained to issue debt and a commission was created to contract loans and sell violaris to finance an army against the Genoese. However, for the time being, there is no record that the financial operation was finally carried out. [43] What we do have evidence of is the indisputable importance of Lleida and Barcelona as capital markets, since we only occasionally find creditors from other places (for example, Cervera).

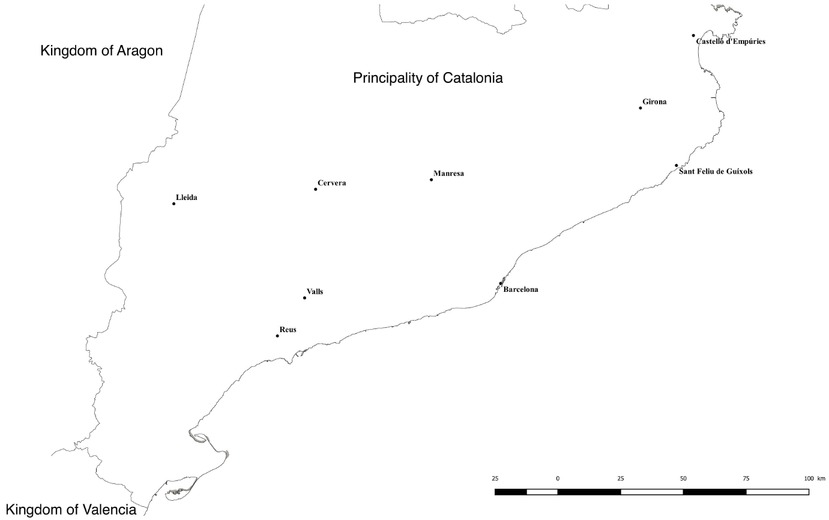

Annuities sold before 1343 in Catalonia. The numbers on the map correspond to the following places: (1) L’Ametlla de Segarra, (2) El Palau d’Anglesola, (3) Granyena de Segarra, (4) Montornès de la Segarra, (5) Savallà del Comtat, and (6) Barberà de la Conca.

With regard to the reason for the issues, the documentation analysed does not allow us to determine in many cases what the specific cause was, although everything seems to indicate that they were largely caused by the growing royal or seigniorial demands during the first third of the 14th century. Nor can we specify in all cases the characteristics of the contracts. From the available data, it can only be inferred that, in general, they were personal loans (that is, they were not guaranteed by specific goods), that they were authorized by the jurisdictional lord of the place and guaranteed before different civil and ecclesiastical instances, and that they could be amortized at will by the municipality or local community. [44]

2.2 The Royal Demands of the Mid-14th Century

As various studies have shown, during the central decades of the 14th century, there was a definitive increase in public debt in Catalonia and also in the rest of the Crown of Aragon. In the Catalan case, this rise was mainly led by the municipalities and can be divided into three phases. The first phase corresponds to the 1340s, when royal domains, at the behest of the monarchy, carried out three major annuity issuances for the conquest of the Kingdom of Mallorca and the initial expedition sent to quell the Sardinian revolt. The second phase occurred during the 1350s and 1360s, when royal demands for the Sardinian conflict seamlessly connected with the war against Castile, forcing both royal and seigneurial domains to incur debt. Finally, during the 1360s, the intense conflict with Castile led to additional annuity issuances by the entire country, gathered in the parliamentary assemblies. This first general issuance, however, still had to be undertaken by the principal municipalities of the Principality on behalf of the Diputació emanating from the Parliament (Corts), as creditors did not have sufficient confidence in the newly created institution.

Although after 1340 we continue to document the occasional sale of annuities in various places, between 1343 and 1347 a pivotal event occurred in the evolution of public debt in Catalonia. As we have noted, at that time, King Peter the Ceremonious implemented a mechanism to quickly obtain the money he needed for his military campaigns through the widespread issuance of annuities by the royal domains. This mechanism involved three-way financial operations which, broadly speaking, consisted of the following: 1) the sale of censals and/or violaris by municipal authorities at the king’s behest; 2) the transfer of the annuties’ price (capital) to the royal treasury; 3) the exemption from taxes periodically collected by the king or the granting of indirect taxes (imposicions) to the municipalities until the annuities sold were redeemed.

The system was not entirely new, as there are records of various attempts to sell rents charged to the imposicions before 1343. As we have seen, Cervera had issued numerous life annuities and perpetual rents during the 1320s and 1330s, some of which were assigned to the proceeds from these indirect taxes. [45] The city of Barcelona also planned a similar operation in 1333 to finance the fleet against Genoa, although we cannot confirm that it was ultimately carried out. [46] The perpetual rent sold by Lleida in 1341, however, was indeed assigned to the imposicions granted to cope with the donation for the so-called War of the Strait against the Marinids. [47] The same fate befell the rents sold by the city of Tarragona and the settlements in the so-called Camp de Tarragona in 1342, following the royal concession of imposicions. [48] However, none of these financial operations were comparable to the one carried out from 1343 onwards.

As shown by Manuel Sánchez, in 1342 the royal domains granted an initial donation to the monarch for the conquest of the island of Mallorca, and part of this donation was paid by the principal cities and towns of Catalonia that were not yet exempt from the questia. Among this group were Manresa, Cervera, Santpedor, Vilafranca, Igualada, Cubelles, Piera, Granollers, Montblanc, Besalú, Tàrrega, Vilagrassa, Terrassa, and Granollers. Specifically, these places sold annuities equivalent to the amount each paid annually for the questia, and in return they obtained a tax exemption as long as those annuities remained unredeemed. It is worth noting that the system was not new: in 1309, the noble Guillem II de Montcada had already exempted Fraga from the questia in exchange for money obtained by its council through the issuance of censals. However, never before had an operation of such magnitude been documented. We cannot delve into the details of each operation nor their particular developments. We only want to high-light that in 1343, a total of 42 annuities were sold against the questia, providing the monarchy with 362,500 s.b. Most of these annuities, in fact thirty of them, were two-life violaris at an interest rate of 14.28 percent. The rest were censals, ten of which were sold at 6.6 percent and two at 8.33 percent. Most of these censals and violaris were sold to citizens of Barcelona under the strict supervision of the royal treasurer. In this way, the king was able to obtain the money he needed more quickly. [49]

As for the places that were exempt from the questia, we do not have as much information. It is worth noting that among these places were Barcelona and other major Catalan cities such as Girona or Lleida. [50] Based on the available studies, it does not seem that, until then, their authorities had resorted to the sale of annuities, at least not habitually. However, in 1343, significant debt issuances by those major cities begin to be documented, funded by the proceeds of extraordinary indirect taxes. Among these issuances, the best-documented so far is the one carried out by the city of Girona between April and May, when records exist of the sale of thirteen violaris to local creditors for a value of 23,590 s.b. at an interest rate of 14.28 percent. [51]

Subsequently, in the year 1344, further massive issuances occurred to finance the new donation granted to the king for the conquest of the County of Roussillon. Following the mechanism just described, all places within the royal domain, from the capital of the Principality to the smallest settlements (like Tagamanent, Òdena, and Mura), sold violaris. Initially, these annuities were supposed to be redeemed within two years with the proceeds from the imposicions, although it was also anticipated that if this did not occur, the taxes could continue to be collected. As part of this operation, Sánchez documented the issuance of 75 violaris, with two lives each, by the city of Manresa and the rest of the royal towns and places of Catalonia. Once again, these annuities were purchased by citizens of Barcelona at 14.28 percent interest, and the money (217,413 s.b.) was delivered directly to the royal treasurer. In the case of smaller places, the capitals of the respective royal districts (vegueries) were responsible for making the sales on their behalf, subject to the presentation of guarantees. Barcelona, Girona, and Lleida, on the other hand, acted autonomously again, and we cannot precisely determine how many violaris they sold. Manuel Sánchez indirectly documents the sale of annuities worth at least 296,580 s.b. in these cities, and it can be assumed that, in all three cases, the buyers were predominantly from the local communities themselves. [52]

Finally, the cycle initiated in 1343 culminated with the issuances made in 1347 to finance the expedition sent by the monarchy to suppress the Doria uprising in Sardinia. In this case, a portion of the operation was once again carried out in exchange for the payment of the questia, and, according to Sánchez, the measure affected the city of Manresa and the settlements of Igualada, Cubelles, Santpedor, Caldes de Montbui, Cambrils, Sarral, and Els Prats. However, the majority of the annuities sold by these places were not violaris but censals at 7.14 percent interest. [53] It is unknown how the rest of the assistance granted to the king was financed exactly, but in places like Barcelona or Girona the issuance of more annuities, both violaris and censals, is documented for that purpose. [54]

Another operation was carried out also in 1347 by the monarchy in the above-mentioned Camp de Tarragona, where an old tribute, called bovatge, which was still paid by the Church, was redeemed. Without delving into the details of this operation, what we are interested in highlighting here is that the places of the Camp, belonging to the Archbishop of Tarragona, also resorted to the issuance of numerous annuities to advance part of that redemption, which ultimately had to be paid also through imposicions. Among the places that issued annuities was, for example, the small town of Valls, which sold 14 censals at 7.14 percent and 10 percent interest, for a total value of 57,600 s.b. The buyers of the main annuities were, also in this case, citizens of Barcelona, although creditors from the settlement itself and other towns are also documented. [55]

We cannot determine exactly what the general impact on the annuity market was from this major series of issuances made by places within the royal domain between 1343 and 1347. If we consider some of the scattered references located so far, we can assume that it was significant, as it is during the 1340s when we also document the sale of annuities in numerous places belonging to major Catalan domains such as the County of Urgell, the County of Empúries, the County of Pallars, or the viscounties of Cardona and Cabrera, among other lordships. In all cases, the lords, like the king, appear to have had a fundamental responsibility in the issuance of annuities by local communities. [56] However, we must wait until the 1350s for the long-term debt of Catalan municipalities to take a qualitative leap and definitively consolidate throughout the Principality and also in the rest of the Crown of Aragon. [57]

Despite the existence of some documented issuances in previous years, 1353 marked the definitive breakthrough of municipal debt in Catalonia. Between 1353 and 1356, the cities and towns within the royal domain were once again the main protagonists in the sale of annuities to pay for the successive donations requested, either generally or particularly, by the monarchy to address the Sardinian conflict and the war against Genoa. It is impossible to list here all the issuances made, so we refer to the details provided by studies dedicated to the debt incurred for this purpose by the cities of Barcelona and Girona, as well as by the towns of Cervera, Manresa, and Sant Feliu de Guíxols. Once again, the annuities were sold against the imposicions granted by the monarchy to municipal authorities, and these authorities delivered the proceeds of the issuances to the money changers (or bankers) responsible for advancing the money to the king. Among the annuities issued, we find violaris, censals, and also mixed annuities, that is, half censal and half violari. The documented interest rates range from 7.14 percent to 16.66 percent, and the buyers of the annuities continue to be in many cases from Barcelona, although there is also an increase in the presence of local creditors or creditors from other towns. [58]

As we have mentioned, from 1356 onwards, the subsidy granted to the monarchy for the Mediterranean wars seamlessly merged with the requests for the conflict against Castile. In this case as well, we cannot dwell on the succession of contributions made, generally or specifically, by Catalan communities to the royal demands or on the conditions of each one. However, between 1356 and 1367 the practice of selling annuities became widespread throughout the Principality, both in the royal domain and in the lordships. In this way, in addition to the details provided by the aforementioned studies on the royal domain, we can add those for cities and towns of lordship such as, for example, the towns of Castelló d’Empúries, Reus, or Valls. In none of these cases was it the first issuance by local authorities, but it did mark the beginning of an irreversible path towards longterm indebtedness. [59]

The case of the capital of the County of Empúries is particularly illustrative. Their authorities sold a total of 94 annuities between 1356 and 1367. Many of these annuities were violaris at 14.28 percent interest, although censals were also created at 10 percent, 7.14 percent, and even 5 percent. Located in the northeast of the Principality, many of the buyers of the annuities issued by the small town of Castelló were citizens of Girona, as it constituted the main financial market in the area. The remainder of annuities were acquired by local creditors or residents of nearby places. The main reason for these issuances was the war against Castile, but the sale of annuities is also documented for fortifying the urban center, redeeming other more burdensome annuities, or meeting particular needs of the Count of Empúries. [60]

In the northeast of Catalonia, another significant example of the extent reached by long-term debt during this period is provided by the issuances made by small rural communities in the Diocese of Girona between 1364 and 1367 due to the War against Castile. An initial study based on notarial documentation from the area has allowed Albert Reixach to obtain a sample of 203 credit operations carried out by 100 rural parishes. Of these 203 operations, 131 were short-term loans, granted in most cases (77 percent) by Jews at an interest rate of approximately 20 percent. The remaining 72 operations were violaris, purchased mostly (70 percent) by residents of the city of Girona at an interest rate of 14.28 percent. It is also worth noting that these life annuities were the preferred recourse of these communities from 1365 onwards because, in addition to their lower interest, they allowed for larger sums of capital: an average of 323 s.b. for the violaris compared to 184 s.b. for the short-term loans. [61]

To conclude this review of the documented annuity issuances between 1343 and 1367, we must discuss the annuities created by various places on behalf of the Diputació del General de Catalunya. As we have mentioned, the issuance of annuities carried out by the entire Catalan political community in 1368 constitutes a definitive turning point in the evolution of the analysed financial instruments. However, we cannot overlook the initial problems that the Diputació faced before gaining the trust of the financial market. Specifically, during the spring of 1365, the Catalan Parliament granted King Peter the Ceremonious the largest donation ever given by Catalonia to the monarchy throughout the 14th century: 13,000,000 s.b. This enormous sum was intended to reverse the course of the war against Castile and had to be obtained through various fiscal and financial procedures. One of these procedures was the sale of perpetual annuities (censals) worth 2,000,000 s.b. charged to the new taxes on imports and exports and on textile production and consumption of the Diputació (generalitats). To obtain these, the debt market in Catalonia was regulated: among other things, the creation of annuities not intended for the Diputació was prohibited, maximum interest rates were established (between 7.14 percent and 12.14 percent), and various guarantees and advantages were offered to buyers. Fearing that the representatives of the Parliament might not be able to find buyers for censals, it was also stipulated that the mission could be entrusted to fifty cities and towns of the Principality, both royal and under seigneurial jurisdiction. [62] This is what ultimately happened: at the end of 1365, the Parliament met again to modify the conditions of the donation granted months earlier, and in the case of the annuity issuance, this had to be assumed by the aforementioned local communities. Likewise, the intervention in the debt market was reduced, with the prohibition of selling censals by institutions and individuals eliminated, as long as their interest rate was at 10 percent. Apart from specific exceptions, only the limitation on selling violaris to take advantage of their high interest rate (14.28 percent) to attract buyers of the Diputació annuities was maintained. It was also confirmed that the generalitats would be allocated to debt repayment, although it was established that if they were not sufficient to pay the interests, these would be guaranteed by the municipalities. Finally, an additional subsidy was granted to prepare for the invasion of Castile, and once again part of the contribution was obtained during the year 1366 through the sale of annuities proportional to the number of households in each locality. [63]

2.3 The Gradual Consolidation of the Debt Market

By 1368 the public debt market in Catalonia had fully consolidated, as the entire political community of the Principality, organized as a legal entity, had committed to the new financial instrument. However, the path there had not been easy, and there are several indications of the initial doubts or problems posed by the sale of perpetual and life annuities.

In principle, the reports on the first annuity issuances we have gathered suggest that, in the 1330s, the censals and violaris sold by local communities began to represent an important financial resource, at least in the western part of Catalonia. Evidence of this is also found in a reference contained in the minutes book of the council of Cervera for the year 1332–1333. It alludes to the doubts held by both municipal authorities and taxpayers when assessing the value of violaris in the wealth registers (manifests) used to collect the proportional direct tax levied annually in the town. [64]

At the beginning of the 1340s, we find more reports confirming the importance of annuities, especially in the financial markets of Lleida and Barcelona, where local authorities were striving to ensure the collection of the annuities acquired by their respective inhabitants. [65] In a municipal meeting held on 17. November 1340, in Lleida, the councillors expressed their concern over a royal decree that pardoned the penalties owed to the owners of censals and violaris in the city. [66] Later, in 1342, the same thing happened in Barcelona, where the authorities secured a promise from King Peter the Ceremonious not to grant remissions of penalties and extensions to violaris acquired by city inhabitants from some knights or noblemen, arguing that the survival of many of those people depended on the collection of the annuities. [67]

In this context we situate the treatise cited in the introduction by the Dominican friar Bernat de Puigcercós, which specialists have dated around 1342. In this treatise, titled Quaestio disputata de licitudine contractus emptionis et venditionis censualis cum conditione revenditioni, Puigcercós defended the legality of the contracts for the sale and purchase of annuities as they were conducted in Catalonia at that time. He was responding to criticisms made by various opponents who considered the annuities a disguised form of usury. Among those opponents was a jurist from the city of Manresa, named Ramon Saera, who, at an unspecified date before his death in 1357, wrote a small treatise against the sale of violaris, titled Allegationes iure facte super contractibus violariorum cum instrumento gratie. Also resulting from this mid-14th century controversy are two other anonymous treatises whose arguments were favourable to Puigcercós’ positions: the first titled Allegationes multum pulchre super contractibus censualium and the second Pulchriores allegationes super contractibus censualium. Complex theoretical discussions contained in all these treatises cannot be the subject of this article. However, their mere existence shows us the moral doubts that arose from the expansion of annuities during the 1340s, especially concerning personal liability and the repurchase agreements. [68]

As we mentioned, it is likely that the large-scale annuity issues instigated by the monarchy in its domains between 1343 and 1347 would have put these doubts to rest. However, in the early 1350s, we still find an interesting reference that attests to the lingering unease, at least regarding censals. That year, the municipal authorities of the city of Girona met with the bishop and other clerics. The objective of the meeting was to confirm that the sale of two censals, created to redeem violaris, was being done at a fair price and that no sin was being committed. Previously, they had also written to a notary in Barcelona for advice on drafting the annuity contracts, a sign of the ongoing insecurity in a regional capital like Girona. [69]

The moral or economic controversies surrounding the sale of censals and violaris never completely vanished. However, the definitive emergence of the public debt market, which, as we have seen, occurred during the 1350s and 1360s, dispelled the judgement of usury or limited it to certain details. [70] From this point on, the main problems arising from this financial resource were in the economic, political, and legal spheres. Indeed, the extraordinary supply of annuities and the consequent indebtedness of local communities soon generated contradictions. We do not know if the general provision at the Parliament held in the town of Perpignan in 1351 ordering the double registration of notarial documents and their full-length drafting without abbreviations was already related to the increase in the sale of annuities and the potential rise in conflicts that might follow. What some studies have detected is the improvement of the clauses in annuity contracts, especially those concerning the seizure of hostages in case of non-payment, as well as other obligations following that provision. [71]

Similarly, a clear example of the contradictions caused by the expansion of the rent market is provided by Cervera, whose authorities already had many problems finding buyers for rents during the years 1355–1356. As they claimed, one of the reasons for this difficulty was the great competition that existed at that time among the different communities when it came to obtaining credit to pay the royal demands. However, there are also indications that another reason could have been the distrust of potential rent buyers, who, from 1353 onwards, requested various guarantees and, above all, the endorsement of the king or his representatives to make the transactions effective. Otherwise, they refused to deliver the price of the acquired rent. [72]

Probably, the contradictory policy of the monarchy itself did not initially help to increase the confidence of the creditors, as it changed provisions aimed at protecting the interests of the latter with grace measures aimed at avoiding the economic collapse of the municipalities. Thus, in the year 1355, a general constitution was promulgated in the Parliament (that is, effective for all Catalonia) in order to put an end to the growing defaulting and resistance on the part of the debtors of rents. In it, the king ordered his officials to guarantee, without exception, compliance with the commitments and penalties contained in the contracts of censals and violaris. However, simultaneously, the monarch also repeatedly granted extensions and remissions of penalties, whether particular or general, so that local communities could continue to meet their demands. This contradicttion explains why places like Cervera continued to have problems selling their rents, even in the inexhaustible financial market of Barcelona, and why its authorities were increasingly unable to meet the expenses of the town, especially the interest on the debt. [73] The situation must have been critical in many places when in the year 1363, at the general Parliament of Monzón, King Peter the Ceremonious passed several laws with the purpose of avoiding the “irreparable destruction” of the communities of his domain. To this end, the monarch prohibited the authorities from selling more rents, unless they were censals to redeem violaris at a higher interest rate. He also committed, in a general and perpetual manner, not to grant further extensions or remissions of penalties to communities or individuals who were obliged to pay rents. Another important royal commitment established that, under no circumstances, could buyers of rents be forced to accept any agreement detrimental to them, nor would pressure from the monarchy in this regard be made. Finally, it is worth noting that, contemporaneously, the king also ensured the continuity of imposicions in the places of his domain, which were questioned by the noble and ecclesiastical estates. This last provision did not imply, de iure, the complete transfer of the indirect tax to the royal municipalities, but de facto ensured the collection of the main fiscal resource upon which the payment of municipal debt was based until it was amortized. [74]

During the following years, the progress of the war forced the monarchy to temporarily suspend some of these provisions and, as we have seen, the king even intervened in the debt market when the first issuance of the Diputació del General de Catalunya was attempted. This strategy would be repeated on several occasions throughout the rest of the late Middle Ages and also during the early modern period. [75] However, despite the repeated conflicts, public debt was fully consolidated, and except for specific moments, legal security for buyers of rents was guaranteed at all times. As a result of this legal security and investor confidence, there was a significant increase in annuity issuances during the last third of the 14th century and the first third of the 15th century, and the system continued to thrive until the 18th century. [76]

3 First Annuities Sold by Catalan Governments and Their Creditors: Data Sample

To examine all the aspects of annuities practice, this article deals with a data sample including eight urban centres from different parts of Catalonia, [77] as well as sparser examples from other 35 places, mainly connected with the aforementioned issues by the Crown in the years 1343–1344 and by the Diputació of Catalonia in 1365–1366. [78] The core of the sample is representative of the whole urban network of the Principality. First of all, there is Barcelona, the main city of Catalonia and a major centre in the Western Mediterranean. There is also another top-five Catalan city, Girona, as well as three of the top-ten, Cervera, Manresa, and Valls. Finally, there are three important towns: Castelló d’Empúries, Sant Feliu de Guíxols, and Reus. Roughly speaking, Barcelona had around 30,000 inhabitants; Girona and Cervera had between 10,000 and 5,000 dwellers, whereas the rest of places were smaller (see Table 1). [79] All of these places can be considered urban centres insofar as they concentrated commercial and financial activity, together with various manufacturing with a greater or lesser weight of certain sectors each. This implied relative socio-professional diversity and complexity, as well as a stratification of wealth and, therefore, the availability of capital for investment. As we shall see, however, the differences were important between the larger cities and the smaller urban centres, with the former taking on a greater role in the financial markets.

Number of inhabitants of each Catalan city and town studied (in 1360).

| Inhabitants | |

|---|---|

| Barcelona | 29,556 |

| Girona | 8,370 |

| Cervera | 5,454 |

| Manresa | 4,639 |

| Castelló d’Empúries | 2,500* |

| Valls | 2,560 |

| Reus | 1,507 |

| Sant Feliu de Guíxols | 1,125 |

Note: The number of inhabitants has been calculated applying a multiplier of 4.5 to the number of focs (hearths). The asterix* marks an approximation only. Sources: Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, Reial Patrimoni, Mestre Racional, Volums, Sèrie General, 2590, f. 1r, f. 18r-v, 1376 (cases of Barcelona, Cervera, Reus, and Valls, though the two latter probably correspond to their inhabitants in 1365); Orti, Una primera aproximació, pp. 755, 757, n. 27 (case of Manresa); Orti, Noves dades seriades, p. 475 (case of Sant Feliu); A. Reixach Sala, Trends in Urban Cereal Markets in North-eastern Catalonia Between c. 1350 and 1500: Fiscal Indicators and Information on Prices, in: A. Furió Diego/P. Benito Monclús (Eds.), Grain Markets in Medieval Europe: Formation, Regulation and Integration, Valencia 2025 (in press) (cases of Girona and Castelló d’Empúries).

Main places in the Principality of Catalonia included in the data sample (1313–1367).

The sample is illustrative from a regional viewpoint and especially with respect to jurisdictional structures. It includes four long-standing settlements under the royal domains (Barcelona, Girona, Cervera, and Manresa) along with Sant Feliu de Guíxols (that entered to them in 1354), a seigneurial small town (Castelló d’Empúries, ruled by the counts of Empúries), and two small towns, Valls and Reus, placed under a shared-jurisdiction by the monarchy and the archbishop of Tarragona, or prelates linked to this cathedral see. [80]

In all the eight places in Table 1, it is possible to trace series of annuity issues from the beginning of the analysed period to the years 1366 or 1367 (see Table 2). Certainly, apart from the earliest operations already commented for the 1320s and 1330s, most of the series start at the beginning of the 1340s, coinciding with the conquest of the old kingdom of Mallorca by King Peter the Ceremonious. Only in the case of Sant Feliu de Guíxols, which had a specific jurisdictional status at that time, the first issue of a perpetual annuity dates to the year 1347. Throughout this approximately 25-year period between the early 1340s and the mid-1360s, the towns and small towns under scrutiny sold hundreds and dozens of life-long and perpetual annuities. In the biggest urban centre, Barcelona, around 700 such operations can be documented between 1343 and 1365, in Girona and Cervera from 300 to 100 (with figures in Castelló d’Empúries and Manresa also approaching one hundred), and, finally, in smaller settlements, from 50 to 10.

Number of annuities sold in Catalonia between 1330 and 1367.

| 1330–1339 | 1340–1349 | 1350–1359 | 1360–1367 | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 0 | 70 | 467 | 160 | 697 | 49.82 |

| Castelló d’E. | 0 | 2 | 20 | 74 | 96 | 6.86 |

| Cervera | 19 | 14 | 58 | 71 | 162 | 11.58 |

| Girona | 0 | 31 | 97 | 133 | 261 | 18.66 |

| Manresa | 0 | 20 | 23 | 42 | 85 | 6.01 |

| Reus | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 0.79 |

| Sant Feliu de G. | 0 | 1 | 23 | 16 | 40 | 2.86 |

| Valls | 1 | 15 | 0 | 31 | 47 | 3.36 |

| TOTAL | 21 | 154 | 692 | 532 | 1,399 | |

| % | 1.5 | 11.01 | 49.46 | 38.03 |

The present sample thus includes 1,399 annuities sold between 1330 and 1367 (or 1,503 if other places apart from the eight aforementioned are considered). As a caveat, this set of data is, along with sparse unpublished data, based on different studies dedicated to the urban centres. These have analysed the evolution of local treasuries thanks to the documentation kept in the respective municipal archives. This means that there is no serialized source in which all the operations that we are investigating are centralized and that some gaps may remain in some cases.

Particularly relevant is the case of Barcelona where, despite a remarkable degree of preservation of records from the central decades of the 14th century, there is no way of restoring all the annuity issues that can be assumed to have taken place, since many of them can only be documented from interest payments years after their original issue. Regarding the city of Girona and other smaller towns, we cannot guarantee that every single operation has been identified. However, any unidentified cases are likely statistically insignificant. Therefore, given the scope and nature of the documentation examined, we believe this constitutes a highly representative sample of life and perpetual annuities issued by municipal governments in Catalonia between approximately 1330 and 1367.

3.1 The Annuities: Chronology, Types and Interest Rate Evolution

In section 2 of this paper, dedicated to the origins of public debt in Catalonia, the emergence and consolidation of annuity practices throughout the central decades of the 14th century has already been explained in detail. The qualitative information gathered is perfectly reflected in the data sample analysed in this section. As can be seen in Table 2, during the 1330s, the sale of rents was very rare, documented in only three of the eight urban centres studied. During the following decade, the phenomenon became widespread, as evidenced by the fact that all eight municipalities issued debt during those years. However, only 11 percent of the analysed contracts were sold between 1340 and 1349, confirming that the use of censals and violaris was still relatively sporadic. Clearly, the great boom in municipal debt occurred during the 1350s coinciding with the fiscal demands connected with the wars in the Western Mediterranean, when almost half of the titles studied were sold. [81] This increasing trend continued until 1367 throughout the demanding fiscal cycle that represented the War against Castile (1356–1366). Barcelona was a notable exception, whose issuance rate seems to have decreased considerably. However, this may be more due to the lack of preserved sources rather than to the actual state of the credit market in the Catalan capital during those years. [82]

Regarding the types of annuities, the clear favourite between 1330 and 1367 was, by far, the violari. As can be seen in Tables 3 and 4, more than two-thirds of the debt titles sold by the eight urban centres were violaris. However, not all places opted for life annuities with the same intensity. Interestingly, Valls only sold censals, a preference shared by its jurisdictional counterpart, Reus, from which we only document one sale of violari, while the remaining ten were censals.

Types of annuities sold by each universitas.

| Life annuities (violaris) | Perpetual annuities (censals) | Mixed rents | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 494 | 171 | 32 | 697 | 49.82 |

| Castelló d’Empúries | 80 | 16 | 0 | 96 | 6.86 |

| Cervera | 92 | 70 | 0 | 162 | 11.58 |

| Girona | 218 | 1 | 42 | 261 | 18.66 |

| Manresa | 66 | 19 | 0 | 85 | 6.01 |

| Reus | 1 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 0.79 |

| Sant Feliu de Guíxols | 23 | 3 | 14 | 40 | 2.86 |

| Valls | 0 | 47 | 0 | 47 | 3.36 |

| TOTAL | 974 | 337 | 88 | 1,399 | |

| % | 69.62 | 24.09 | 6.29 |

Types of annuities sold between 1330 and 1367.

| Life-annuities (violaris) | Perpetual annuities (censals) | Mixed rents | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1330–1339 | 16 | 5 | 0 | 21 | 1.5 |

| 1340–1349 | 117 | 37 | 0 | 154 | 11.01 |

| 1350–1359 | 457 | 186 | 49 | 699 | 49.46 |

| 1360–1367 | 384 | 109 | 39 | 532 | 38.03 |

| TOTAL | 974 | 337 | 88 | 1,399 | |

| % | 69.62 | 24.09 | 6.29 |

On the other hand, Girona sold 83.52 percent of its titles as life annuities between 1330 and 1367. Barcelona also leaned much more towards violaris than censals (70.87 percent and 24.53 percent respectively), indicating a clear preference for life annuities among the major urban centres. This same reasoning would explain why only in Barcelona, Girona, and Sant Feliu de Guíxols (closely linked to Girona) do we find mixed rents, an hybrid between violari and censal, which is completely absent from the other towns.

Regarding the preference for one type of rent over another throughout the studied decades, it is worth highlighting once again the undisputed popularity of the violari (Table 4). However, it is noteworthy that there was a significant drop during the 1350s, when violaris represented only 65.38 percent of the sales studied, a percentage that for the rest of the decades was always above 70 percent. Even so, it is important to consider that it is precisely between 1350 and 1359 when the first mixed rents are documented, which, after all, were partly a life annuity. Considering that these hybrid titles represented 7 percent of the sales studied during the 1350s, the percentage drop of violaris would actually be smaller if these were added. In fact, between 1360 and 1367, the sales of perpetual rents were, percentage-wise, the lowest of the entire studied period (20.49 percent). This makes it undeniable that, by the end of the studied period, the transition from violari to censal, which would lead to the near disappearance of life annuities by the 15th century, had not yet taken place. [83]

The substitution of violaris with censals was not a minor change: it meant consolidating rents with an interest rate between 8 and 5 percent instead of the usual life annuities with an interest rate of 14.28 percent. During the examined period, however, the high presence of life annuities explains why the average interest rates remained between 10.42 and 12.91 percent from 1330 to 1367 (Table 5). In fact, 12.91 percent corresponds precisely to the years 1360–1367, which once again confirms that we are looking at the early stages of the public debt market, that had not yet managed to impose less onerous rates on creditors.

Average annual interest rate of the annuities sold between 1330 and 1367.

| 1330–1339 | 1340–1349 | 1350–1359 | 1360–1367 | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | - | 9.53 | 12.16 | 12.68 | 12.01 |

| Castelló d’E. | - | 9.77 | 12.75 | 13.9 | 13.57 |

| Cervera | 12.02 | 13.43 | 11.82 | 12.13 | 12.12 |

| Girona | - | 14.29 | 12.37 | 13.96 | 13.41 |

| Manresa* | - | 13.21 | 10.71 | 13.83 | 12.83 |

| Reus** | - | 8.33 | 8.33 | 9.33 | 8.83 |

| Sant Feliu de G. | - | 14.29 | 11.7 | 12.82 | 12.21 |

| Valls | 7.01 | 9.24 | - | 9.01 | 9.04 |

| TOTAL | 11.77 | 10.42 | 12.11 | 12.91 | 12.31 |

Note: *Unfortunately, there are many annuities from Manresa of which we do not know the interest rate. **Despite the documented sale of a violari of 1,000 s.j./s.b. of rent to Bernat d’Olzinelles by the council of Reus prior to 1332, we do not know its interest rate. However, it was most likely 14.28 percent.

If we look at the rates by community, it is interesting to note that, in almost all cases, they were higher at the end of the studied period than at the beginning, with the only exceptions to this rule being Girona and Sant Feliu de Guíxols. Especially revealing is the case of Castelló d’Empúries, whose average interest rate increased by more than four points between 1340–1349 and 1360–1367. As for the generally low rates in Reus and Valls, they are easily explained, considering that, as mentioned earlier, almost all the rents sold by both small towns were perpetual. In fact, considering that the standard interest rate for censals was 7.14 percent, the fact that the 47 perpetual rents sold by Valls between 1330 and 1367 had an average rate of 9.04 percent is a possible indicator of the small town’s need to entice potential creditors, probably somewhat wary, with attracttive interest rates.

3.2 The Investors: Dominant Profiles Within a Heterogeneous Group

Let us move on to analyse the purchasers or investors of the annuities, focusing on their gender, social condition, and place of origin or residence. Traditional literature on the subject has tended to overemphasize the merchants or members of the oligarchy who, either by buying debt or by direct appropriation of public resources thanks to their privileged position, abandoned commercial investments, thus fitting in with Fernand Braudel’s commonplace of the “betrayal” of the bourgeoisie. [84] Our purpose is therefore to see to what extent the purchasers of the first debt issues by municipal governments in Catalonia corresponded to this pattern or whether the range of possibilities should be opened up, taking into account the relative weight of other socio-economic groups.

A first important observation deals with the legal status of buyers of annuities (see Table 6). Most of them were individuals, and only less than 5 percent of them were juridical persons or legal entities. Specifically, 2.1 percent corresponded to guardianships and executorships, whereas just 1.7 percent were institutions, mainly monasteries and nunneries.

Buyers of annuities.

| Men | Women | Institutions | Guardianships / Executorships | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patricians | 312.5 | 118 | 0 | 18 | 448.5 | 29.84 |

| Merchants | 289 | 44 | 0 | 1 | 334 | 22.22 |

| Jurists / Doctors | 52 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 61 | 4.06 |

| Notaries | 41 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 2.93 |

| Artisans | 167 | 25 | 0 | 4 | 197.5 | 13.14 |

| Nobles | 24 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 2.93 |

| Religious / Welfare | 40 | 24 | 25 | 0 | 89 | 5.92 |

| Royal Officers | 60 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 4.32 |

| Unidentified | 157.5 | 56.5 | 0 | 6 | 220 | 14.64 |

| TOTAL | 1143 | 303 | 25 | 32 | 1,503 | |

| % | 76.05 | 20.16 | 1.66 | 2.13 |

This trend changed during the last decades of the 14th century, but this is a phenomenon that had not yet manifested itself within the time period studied here. [85] Nonetheless, paying attention to the value of their pensions, guardianships and executorships bought, on average, higher annuities than natural persons (see Table 7). Probably the high values of these rents were a result of a will to provide underage children (and their guardians) with as much resources as possible. [86]

Buyers of annuities according to their value (in s.j./s.b.).

| Men | Women | Institutions | Guardianships / Executorships | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patricians | 223,117 | 58,388 | 0 | 11,435.67 | 292,941 | 34.76 |

| Merchants | 171,476 | 21,131 | 0 | 1,000 | 193,607 | 22.97 |

| Jurists / Doctors | 28,160 | 3,783 | 0 | 1,650 | 33,593 | 3.99 |

| Notaries | 17,051 | 1,400 | 0 | 0 | 18,451 | 2.19 |

| Artisans | 70,882 | 11,667 | 0 | 2,660 | 85,209 | 10.11 |

| Nobles | 16,081 | 17,515 | 0 | 0 | 33,596 | 3.99 |

| Religious / Welfare | 19,623 | 13,071 | 15,236 | 0 | 47,930 | 5.69 |

| Royal Officers | 42,449 | 2,900 | 0 | 0 | 45,359 | 5.38 |

| Unidentified | 66,330 | 21,404 | 0 | 4,400 | 92,134 | 10.93 |

| TOTAL | 655,169 | 151,259 | 15,236 | 21,145 | 842,809 | |

| % | 77.74 | 17.95 | 1.81 | 2,51 |

Focusing on these individuals, there is little doubt that if we were looking for an annuity buyer in Catalonia during the middle decades of the 14th century, we would most likely find a man, and perhaps, according to the aforementioned and widespread assumption, a member of the urban elite. Yet, what about women? Our dataset confirms that men possessed more than three quarters of the annuities sold, whereas women owned one fifth of them. The differences between male and female buyers are even larger if we consider the average pension: women bought, on average, lower value annuities (see Table 8). Many of these women were widows, maybe looking for some stable income to compensate for their lowered economic possibilities after the death of their husbands. [87]

Average value of pensions (in s.j./s.b.).

| Group | Average pension |

|---|---|

| Men | 573 |

| Women | 499 |

| Institutions | 609 |

| Guardianships / Executorships | 661 |

| TOTAL | 561 |

From another viewpoint, the participation of women in public debt markets was not the same in all the cities and towns studied. Broadly speaking, it seems that women from bigger cities were more eager or able to buy annuities rather than women from smaller cities and towns (see Tables 9 and 10).

Sellers and buyers of annuities.

| Men | Women | Institutions | Guardianships / Executorships | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 497.5 | 160.5 | 13 | 25 | 696 | 49.75 |

| Girona | 194 | 65 | 0 | 2 | 261 | 18.66 |

| Cervera | 130 | 25 | 7 | 1 | 163 | 11.65 |

| Manresa | 68.5 | 15.5 | 1 | 0 | 85 | 6.08 |

| Valls | 41 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 47 | 3.36 |

| Castelló d’E. | 83 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 96 | 6.86 |

| Sant Feliu de G. | 39 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 2.86 |

| Reus | 8.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0.79 |

| TOTAL | 1,061.5 | 285.5 | 22 | 30 | 1,399 | |

| % | 75.88 | 20.41 | 1.57 | 2.14 |

Sellers and buyers of annuities according to their value (in s.j./s.b.).

| Men | Women | Institutions | Guardianships / Executorships | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 366,605 | 105,020 | 11,800 | 17,496 | 500,921 | 63.43 |

| Girona | 82,193 | 16,002 | 0 | 1,350 | 99,546 | 12.6 |

| Cervera | 71,284 | 12,786 | 1,386 | 600 | 86,056 | 10.9 |

| Manresa | 36,278 | 4,850 | 0 | 0 | 41,128 | 5.21 |

| Valls | 15,673 | 3,017 | 0 | 333 | 19,023 | 2.41 |

| Castelló d’E. | 27,426 | 2,496 | 1,000 | 200 | 31,121 | 3.94 |

| Sant Feliu de G. | 7,252 | 150 | 0 | 0 | 7,401 | 0.94 |

| Reus | 3,861 | 675 | 0 | 0 | 4,536 | 0.57 |

| TOTAL | 610,572 | 144,996 | 14,186 | 19,979 | 789,733 | |

| % | 77.31 | 18.36 | 1.8 | 2.53 |

For instance, one fourth of the rents sold by Girona were bought by women, whereas only 2.5 percent of those sold by Sant Feliu de Guíxols (one annuity only) was acquired by a woman. [88] This is an extremely low figure, given that the percentages regarding female buyers in all other small cities and towns range between 8 percent and 16 percent. Reus seems to be an exception of this rule, but it is probably due to the low number of annuities registered and the low representativeness of this sample.

If we now take a closer look at the social status of the investors in the first series of annuity issues by the Catalan municipal governments (see Tables 6 and 7), we detect the expected pre-eminence of the upper segments of urban society. This observation, however, must be put into context. As we have insisted, the very division of buyers into different categories is conditional to the somewhat unequal characteristics of the urban centres analysed. In short, the upper strata in cities such as Barcelona or Girona were not the same as those of small towns like Sant Feliu de Guíxols or Reus. To begin with, the socio-professional label of patrician that we use to refer to what the sources call citizens (honourable citizens in the case of Barcelona), that is, wealthy urban dwellers with diversified sources of income and without any specific professional dedication, is only present in cities such as the Catalan capital itself, Lleida, Girona, and some other big towns. In smaller centres, the dominant groups of the respective communities were the members of the mercantile class or other groups that we have also isolated, such as jurists and doctors (both with university degrees that gave them a higher social rank) and notaries (trained through practical apprenticeship).

In any case, members of the patrician class, including merchants, jurists, and notaries, together accounted for more than half of the rents issued (59 percent). But we should not omit the craftsmen, especially in the most important manufacturing sectors like textiles and silver-smithing, who acquired 12 percent of the annuities. In secondary position are nobles (3 percent), as well as members of the royal household or those holding positions in the royal administration: these, with a total of 4.4 percent of the annuities, must be considered a separate socioprofessional group, since their networks were probably more important than their own wealth in becoming purchasers of debt. Religious investors, i.e., clergymen, nuns, and charitable organizations made up close to 6 percent of buyers. However, as with certain legal entities, the available studies show that their prominence increased just after the period we are now discussing. [89] The final group, which is not negligible, representing 14 percent of investors, is made up of men, women, and guardianships and executorships for which we have no further information besides their name, and therefore they cannot be labelled in social terms.

If we pay attention to the value of the interests of the rents purchased, and not simply to their number, the percentages relative to the various socioprofessional groups are not very different. The only significant change occurs with the craftsmen and the unidentified group, who, in fact, bought annuities of lesser value than other groups. From this point of view, their weight drops from 12 to 9.5 percent for craftsmen and 14.2 percent to 9.7 percent for those unidentified. By contrast, noblemen and the members of the royal entourage show a relatively higher financial potential, as the percentage of the total interest yielded by the annuities they held is between one and two points higher than the percentage corresponding to the number of annuities they owned. Again, this is due to the differences between the average value of the annuities bought by each of these groups (see Table 11). The value of the rents possessed by nobles was, by far, the highest. [90] Unsurprisingly, they were followed by royal officers, patricians, and, albeit at a certain distance, merchants. The interests they received were, on average, above the average interest that we document during the central decades of the fourteenth century. On the other hand, the average interest paid to jurists and doctors, religious and welfare persons and institutions, artisans, and notaries (as well as the group of “unidentified” people) were all below the total average.

Average value of pensions (in s.j./s.b.) according to social status.

| Group | Average pension |

|---|---|

| Patricians | 653 |

| Merchants | 580 |

| Jurists / Doctors | 551 |

| Notaries | 419 |

| Artisans | 431 |

| Nobles | 763 |

| Religious / Welfare | 538 |

| Royal Officers | 698 |

| Unidentified | 419 |

| TOTAL | 561 |

With respect to the geography of the investors we are dealing with, it is important to point out once more that, even though the sample can be considered representative, it does not include all the cities and towns of Catalonia. Despite this, a trend is clear enough: there is an indisputable importance of the inhabitants of the capital, Barcelona, in these operations (see Tables 12 and 13). They represent roughly half of the purchasers of the annuities under study, or even 60 percent if the value of the annual payments they received is considered. However, this high number of Barcelonese buyers could be considered misleading, since half of the annuities analysed were sold by the Catalan capital. Therefore, it could be argued that these high percentages match Barcelona’s issues of debt and that its inhabitants probably had no interest in annuities sold beyond the city borders. But a more detailed look shows us that, in fact, that was not the case. Only 86 percent of the rents issued by Barcelona were bought by its own inhabitants and institutions, whereas these first creditors extended their influence towns or small towns such as Manresa, Cervera, and Valls. The case of Manresa is particularly illustrative of the preeminence of Barcelona buyers, since they possessed more than two thirds of its annuities, and an even higher percentage of value.

Origin of the buyers of annuities.

| Men | Women | Institutions | Guardianships / Executorships | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 609 | 161 | 16 | 22 | 810 | 61.95 |

| Girona | 229 | 67 | 0 | 3 | 297 | 22.71 |

| Cervera | 53 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 66 | 5.05 |

| Manresa | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 1.22 |

| Valls | 24 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 1.99 |

| Castelló d’E. | 37 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 47 | 3.59 |

| Sant Feliu de G. | 25 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 1.99 |

| Reus | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.31 |

| Lleida | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 15.5 | 1.18 |

| TOTAL | 1,005 | 251 | 25 | 26.5 | 1,307.5 | |

| % | 76.86 | 19.2 | 1,91 | 2.03 |

Origin of the buyers of annuities, according to their value (in s.j./s.b.).

| Men | Women | Institutions | Guardianships / Executorships | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 429,305 | 95,900 | 12,850 | 13,746 | 551,801 | 75.29 |

| Girona | 87,629 | 15,632 | 0 | 1,550 | 104,811 | 14.3 |

| Cervera | 17,773 | 1,900 | 1,386 | 600 | 21,659 | 2.95 |

| Manresa | 3,950 | 2,700 | 0 | 0 | 6,650 | 0.91 |

| Valls | 5,823 | 350 | 0 | 0 | 6,173 | 0.84 |

| Castelló d’E. | 10,997 | 2,246 | 1,000 | 0 | 14,243 | 1.94 |

| Sant Feliu de G. | 5,088 | 150 | 0 | 0 | 5,238 | 0.71 |

| Reus | 719 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 919 | 0.12 |

| Lleida | 20,428 | 0 | 0 | 1,000 | 21,428 | 2.92 |

| TOTAL | 581,713 | 119,078 | 15,236 | 16,896 | 732,923 | |

| % | 79.37 | 16.25 | 2.08 | 2.3 |

Barcelona as the debt capital of Catalonia is a phenomenon that has been studied for later decades. [91] The data studied here suggests that it already became so in the early days of the public debt market.