Abstract

Nursing leaders are increasingly required to create and implement innovative solutions to address challenges in the workplace. However, the present-day education of graduate nurses may not adequately prepare them for entrepreneurial approaches to problem solving required in today’s complex healthcare environments. To fill this gap, we designed, implemented, and evaluated a Healthcare Grand Challenge course for graduate nurses interested in developing their leadership skills. Following the course, students were invited to participate in a qualitative research study to explore their experiences and perceptions of the course and identify how they used the knowledge and skills developed through the course in their leadership practices. This study provides key lessons for future offerings of grand challenge courses while highlighting the influence of grand challenge courses on current and future nursing leadership practice.

Current nursing graduate students need to develop leadership and innovation skills to help generate novel solutions and evidence-based interventions across healthcare settings. However, present-day graduate nursing education may not sufficiently prepare graduate nurses for innovative approaches to problem solving required in today’s complex healthcare environments (Weberg & Davidson, 2021). Higher education institutions are examining their graduate training to reassess how they prepare graduate students to lead the challenge of solving complex multilevel problems. To educate and inspire the next generation of nursing leaders to address pertinent and pressing issues in the healthcare system, innovative teaching and learning opportunities are needed. Implementing certificate programs that incorporate grand challenges and experiential learning opportunities may help prepare future nursing leaders to actively engage in innovative problem solving to address complex healthcare problems.

Background

Graduate certificate programs

Graduate certificates programs are one way to support the learning and development of professionals while providing clear credentials relevant in both academic and non-academic careers (Osborne, Carpenter, Burnette, Rolheiser, & Korpan 2014). Often structured to provide practical, flexible, and adaptable learning experiences, certificate programs are grounded in evidence-based knowledge that is relevant to specific disciplines and contexts. Graduate certificate programs that are meaningful, accessible, and relevant to current nursing practice are gaining in popularity across the U.K. Australia, Canada, and the U.S. as they allow nurses to meet the demands of the healthcare industry while prepositioning them for success with knowledge, skills, and insights that are relevant and pertinent to their area of nursing practice (Abraham & Komattil, 2017; Lindsay, Oelschlegel, & Earl, 2017; O’Neil & Fisher, 2019). Increased enrollment of registered nurses (RNs) in certificate programs provides the much-needed evidence of their inherent value and benefit to professional practice (Moore, 2020).

Grand challenges

Grand challenges are complex science, technology, health, and developmental problems that may have multiple possible solutions (Ferraro, Etzion, & Gehman, 2015) and require engagement from multiple people across disciplines to solve them. Grand challenges are united by their focus on fostering innovation, directing resources to where they will have the most impact, and serving those most in need (Grand Challenges Canada, n.d). Using grand challenges as a pedagogical approach can help students develop solutions to pressing problems while resulting in deeper learning (Vest, 2008). Grand challenge courses are one way to elevate focus, energy, and leadership on key issues while necessitating collaborations between students and key stakeholders. Working on grand challenges also involves a heightened need for communication, conceptualization, and collaboration skills as well as integrative thinking and productive collective work that respects and values differences (Nurius, Coffey, Fong, Korr, & McRoy, 2017).

A recently conducted scoping review revealed a growing interest in using grand challenges as part of the learning process in higher education globally, yet there remains a lack of rigorous research on the impact on student learning (Nowell et al., 2020). Most grand challenge literature to date originates from North America, is focused on engineering challenges, and fails to address challenges common to health care (Nowell et al., 2020). Furthermore, the use of grand challenges in graduate nursing education has yet to be studied empirically. To begin to fill this gap, we explored nursing graduate students’ experiences and perceptions of a healthcare grand challenge course. We anticipate the findings of the present pilot study will enhance understandings of the value of using grand challenge approaches in nursing graduate education and provide higher education institutions with recommendations for the design of other grand challenge courses in nursing curricula.

Experiential learning

Experiential learning emphasises the development of real-world skills through applied learning opportunities which have a positive and powerful impact on the quality and meaning of learning experiences (Bass, 2012). There is sound pedagogical evidence for incorporating experiential approaches into certificate programs. Larson, Downing, and Nolan (2020) demonstrated high impact experiential learning experiences have significant impact on students’ overall academic success. Further, employers often seek job applicants with the leadership, communication, and problem-solving skills that can be developed through well-designed, effective experiential learning opportunities (Roberts, 2018).

The context: graduate certificate program

Our nursing program offers graduate certificates in seven specializations:

Addiction and Mental Health

Aging and Older Adults

Innovations in Teaching and Learning

Nursing Leadership for Health System Transformation

Healthcare Innovation and Design

Oncology Nursing

Palliative and End of Life Care

These certificates, launched in September 2019, were created to offer advanced nursing practice knowledge along with practical experience for RNs wishing to acquire specialized skills. Students enroll in the program to advance their careers in their current practice area, transition into a new area, or to enter more senior leadership, education, or management positions. These certificates were designed through extensive consultation with healthcare stakeholders to ensure the learning opportunities were meaningful and relevant to current nursing practice.

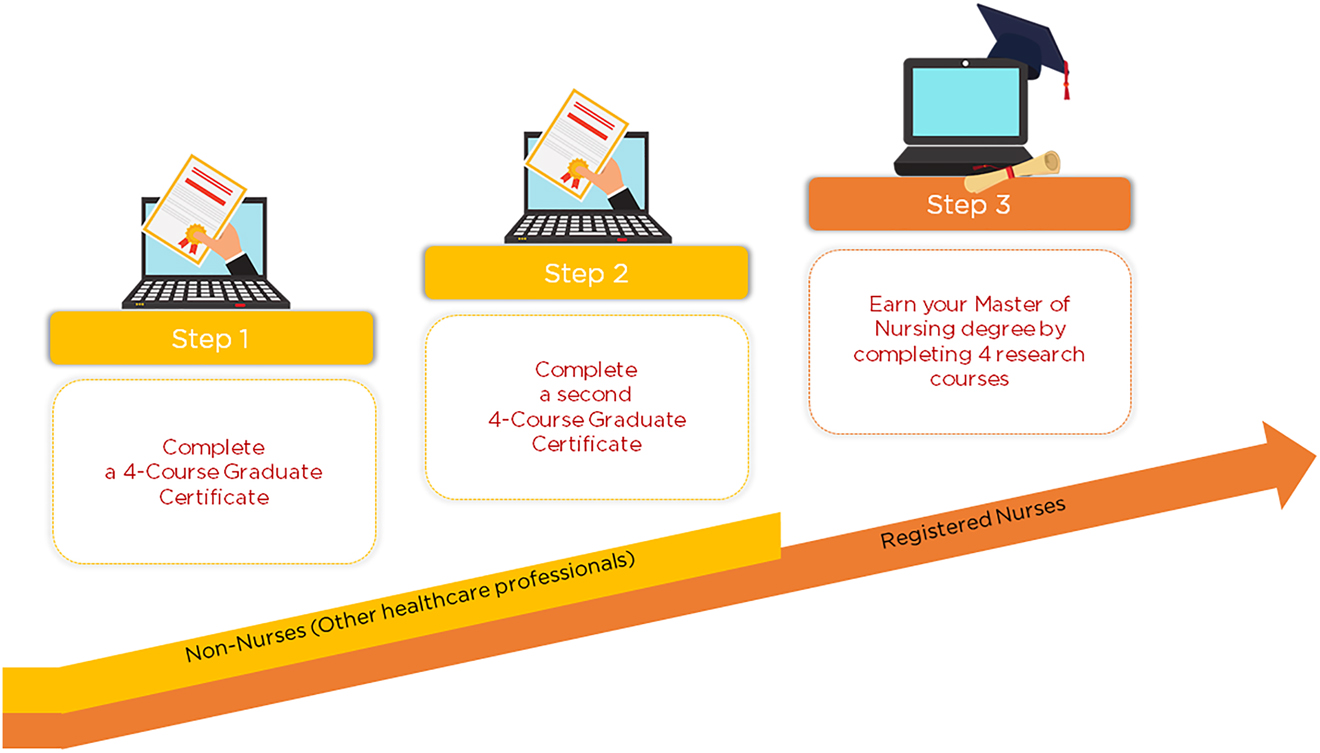

Each certificate is offered as a one-year, part-time, cohort-based program, offered through blended delivery. Each graduate certificate consists of four courses, the equivalent of one year of part-time studies. The curriculum for each certificate has been designed to meet the course requirements to apply for admission into the Master of Nursing (MN) Laddered Certificate Pathway (course-based) degree (see Figure 1).

Master of nursing (MN) laddered certificate pathway.

Leadership for Health Systems Transformation certificate

In the Leadership for Health System Transformation certificate, students apply principles of personal leadership during course one, systems level leadership during course two, and leading innovation in healthcare contexts during course three, largely from the viewpoint of challenges and issues confronting nursing leaders. This certificate program culminates in the fourth grand challenge course where students explore a leadership challenge.

Healthcare Grand Challenge course

The Healthcare Grand Challenge course is the fourth course in the Leadership for Health Systems transformation certificate and was offered for the first time during the summer of 2020. At the beginning of the course students were presented with a relevant and timely grand challenge proposed by leaders in the local healthcare system. The grand challenge identified as being most relevant during the summer of 2020 was Preparing for Epidemics as we were experiencing firsthand the impact COVID-19 around the world. Individually, students identified an ambitious yet manageable piece of the problem that they wanted to solve during the course and created a visual map of the complexities surrounding their challenge topic. Students then shared their visual maps and spoke to experts in the healthcare system to inquire about others’ perspectives about the proposed issue. All students then came together for a three-day online design sprint (an evidence-based process for solving grand challenges through prototyping and testing ideas with peers and stakeholders) where they worked together to solve their identified problems, test their prototypes, and develop a comprehensive innovation pitch that was presented back to the leaders in the local healthcare system. The course learning outcomes are highlighted in Table 1.

Healthcare grand challenge course learning outcomes.

| To meet the intended learning outcomes of the course, students were required to: |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Methods

Pilot study design

A qualitative design for program evaluation, as suggested by Patton (2002) was used to explore students’ experiences and perceptions of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course. This pilot study and teaching within were guided by experiential learning principles and underpinned by pragmatic philosophy (Klockner, Shields, Pillay, & Ames, 2021). Thematic analysis methods were used to examine the perspectives of different students and develop a detailed, rich, and complex account of their experiences while also highlighting similarities differences, and unanticipated insights (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, 2017).

Participants and recruitment

All graduate nursing students who completed the Healthcare Grand Challenge course in summer 2020 (n=14) were invited to participate. Students were eligible to participate if they passed the assessment criteria of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course and were willing to share their experiences and perceptions of the course. A research assistant, who was not involved in the course, emailed all eligible students requesting them to reply if they were interested in participating.

Data collection

A masters-prepared research assistant, who did not know the students, conducted semi-structured online interviews lasting approximately 30 min with participants from August to September 2020, after the completion of the course. Interview data were audio recorded and transcribed by a professional transcriptionist word for word. We utilized semi-structured interview guide that consisted of open-ended questions to ensure consistency across the interviews (Table 2). The interview guide was developed by the team and pilot tested with two graduate students to ensure clarity and ease of use.

Semi-structured interview guide.

| Interview questions |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data analysis

All interview data were imported into NVivo 12 for data management and analysis. Qualitative data were thematically analysed (Nowell et al. 2017) by a process of induction to move interview data from individual sources to common, interactive themes (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Two researchers independently read the transcripts to get a sense of the entire data set, held weekly coding meetings to develop a mutual understanding of the provisional codes, and then examined and assigned sections of text to codes, themes, and subthemes. Larger team meetings were held to further refine and examine the patterns in the data and finalize the themes and subthemes and written memos were used to record our analytic process. A brief summary of the findings were shared with the study participant to ensure the findings accurately represented their experiences. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) were followed in our research and reporting processes (O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014).

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct this research was granted through the local Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB19-2131). Students were invited to participate only after course completion and grades were submitted prior to interviews to ensure voluntary participations without any impact on student grades. All participants provided informed verbal and written consent prior to being interviewed. Participant anonymity was maintained by allocating unique identifiers to each participant and aggregating the data.

Trustworthiness

Several techniques were used to maximize the trustworthiness of study findings. Team meetings allowed for debriefing amongst the team and provided a place for reflexivity to explore discrepant data, ask questions, and develop a unified understanding of interpretations (Morse, 2015). A detailed audit trail preserved team decisions by recording meeting minutes and maintaining a codebook. A team of two researchers coded all transcripts while decisions about themes and subthemes were examined with the whole team (Morse, 2015), returning to the raw data to ensure themes and subthemes accurately reflected participant voices (Morse, 2015).

Findings

All students who enrolled in the certificate (n=14) were nurses from Canada and they all successfully passed the course. Seven students (two male; five female) consented to participate in this pilot study and completed semi-structure interviews. These students were part of a cohort throughout the Leadership for Health Systems Transformation Certificate and were required to use the skills developed throughout the certificate to address the grand challenge in the final course. Therefore, the findings reflect perceptions of the overall certificate as well as of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course. Patterns that emerged from the interviews were grouped into four interrelated and broad themes that were delineated into further subthemes. Table 3 provides an overview of the themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes.

Overview of themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes.

| Themes | Subthemes | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for taking the Leadership for Health Systems Transformation certificate | Searching for innovative approaches to graduate studies | “I don’t think we have anything like that in Canada yet, in nursing. So, I think this … is something really advanced in this era.” (P1) |

| “I have done a couple of leadership certificates that did not lead to a university certificate. So, I wanted to do a university certificate that was a postgraduate certificate.” (P3) | ||

| Opening the doors to new opportunities | “be aligned with other professions who have master’s levels so that our voices will be stronger” (P1). | |

| “Unless you have some more formal leadership training, people don’t take your suggestions and ideas as seriously. And even in the last year, people knowing that I’ve been enrolled in the certificate has made a difference… that was the main driver, was to have some more credibility behind my ideas and develop my leadership skills.” (P2) | ||

| Increasing leadership knowledge and capacity | “Although I have a lot of experience, what I lacked was the theoretical background…how do I find the evidence that I need to inform quality improvement and how do I discern what is a good quality improvement project for me to pursue and how do I prioritize them?”(P7) | |

| “I knew that …. I’d be in charge of leading teams and I wanted to know what I could do better personally, which was a draw to this program. And then the systems thinking was a big driver and understanding the impact of how one change can cause a ripple” (P2) | ||

| Positive aspects of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course | Real word applicability | “useful applicable information to apply in the real workplace.” (P6) |

| “We were given a real-life problem with real life consequences and we met with real life people… often times in school you learn a lot of theory…and you never really doing in the moment sometimes and this felt like a real in the moment learning.” (P5) | ||

| Opportunities to engage with stakeholders | “To talk to the right stakeholders and include the right people. That was a definite win… and it put some things on people’s radars that I don’t think they had even thought about.” (P2) | |

| “The most important skill that I’ve developed is how to involve people in managing change, how to get other people involved in change, how to get ideas from different stakeholders and how to be the last person in the room to speak. So, to say, in terms of gathering other people’s ideas first and synthesizing those ideas, and sometimes not even bringing your own idea to the table.” (P3) | ||

| Relational approach to group work and interactivity | “Collaboration with everybody and having other people’s ideas from outside of my work life was extremely valuable to me. To think about things differently.” (P2) | |

| “we support each other, and we talk with each other and it has been good for me to see how other people learn and what I can learn from them. And without those discussions, the other members of the group, I don’t think I would be doing as well, or I would have learned as much. So that was the best thing for me.” (P3) | ||

| “to develop relationships that supported one another, encouraged one another and if we had questions, we would talk about our ideas with one another. I really like that.” (P4) | ||

| Skills development | “I learned in this course…how we make sure that everybody’s voice is heard.” (P3) | |

| “I feel like I’m here for a reason, I’m learning, I’m getting challenged, I am practicing…some of those authentic trusting leadership skills that I want to evolve and grow, in my practice… I am able to think more broadly and apply different principles to resolve solutions that I’d never thought of before.” (P4) | ||

| “I suppose the skill that I learned in the Grand Challenge was how to bring all of the other skills to bear in a very time sensitive and tightly controlled environment.” (P5) | ||

| Lessons Learned | Learning through vagueness | “A lot of us we’re kind of miffed at the vagueness of the instructions…and then we thought “Maybe this was purposeful by design. Maybe it was intentionally vague because we were supposed to pull our tools from the toolbox that we had been amassing all year.” (P5) |

| “So I think it helped that we help build trust with each other over the entire certificate because it made it easier to not know all of the pieces that were going to be the end result. I loved it, even though I was a little scared.” (P2) | ||

| Set the stage for innovative education | “A professor who is able to create that safe space and that who’s approachable, and you’re not afraid to ask for feedback, but who also provides that feedback in a very kind way. So, I think…teaching style also contributed to how positive this experience was for me.” (P7) | |

| “I also really appreciated the fact that the instructors that were leading the course were also very innovative and open-minded and not your traditional leaders or instructors. So that fostered our innovation and thinking and really encouraging us to think outside the box.” (P4) | ||

| “This type of course, because of the intimacy and the speed at which it moves, requires a dedicated and attentive instructor.” (P5) | ||

| Increase connection points with peers and stakeholders | “Collaboration with everybody and having other people’s ideas from outside of my work life was extremely valuable to me. To think about things differently. They brought something up totally different than what I was thinking.” (P2) | |

| “I had so many learnings from the book and I wanted to discuss the contents with other students and the teacher.” (P1) | ||

| Impact of the pandemic | “We had to cancel the in-class and we have to meet over Zoom. While there is a benefit of using Zoom where we don’t have to juggle so much of the life commitments because we can do it from home. But at the same time, we are losing that connection with other peers” (P1) | |

| “I think there would be so much value in that being in-person on some level or at least one day that we can present. There’s something to be said about putting on your shoes, putting on your nice clothes, combing your hair, brushing your teeth and going and doing a live presentation. I mean, for leaders, for people being trained in leadership who might be occupying Dean’s offices or CEO’s offices or starting businesses, there is no virtual substitutes that can train you to work a room. I am sorry. And that is just a fundamental skill that leaders need to have” (P5) | ||

| Impact on current and future nursing practice | Discovering new horizons | “It…changed the way I look at health care system and it changed the way I look at leadership. I’m now going towards different direction in my career.” (P1) |

| “I think that being able to understand the systems that were involved and contribute to …how changes within a program … affect those other systems, being able to add that whole system perspective was very beneficial.” (P7) | ||

| Embracing lifelong learning | “I’m actually translating that into my current role with our orientation process.” (P6) | |

| “So always learning and expanding my knowledge and practices. Giving me the tools I needed for every practical and professional…role and everyday life, being able to use that and hopefully being able to expand on my nursing. I am practicing what I know in saying that, calling out the behaviors and then moving forward with some of those authentic trusting leadership skills that I want to evolve and grow, in my practice” (P4) | ||

| Increasing awareness of self as leader | “changed the way I look at leadership.” (P1) | |

| “I developed more awareness of my own leadership skills, as well as being able to pinpoint the behaviors I was seeing…I’m able to grow in my own learning and really, I guess, figure out who I want to be as a leader. I felt like throughout this whole year, it was a buildup starting with self-awareness of your own leadership skills and then taking that and building upon it” (P4) | ||

| Seeking diverse voices and perspectives | “The most important skill that I’ve developed is how to involve people in managing change, how to get other people involved in change, how to get ideas from different stakeholders. Gathering other people’s ideas first and synthesizing those ideas…gathering people’s ideas on how we involve our staff who normally will not be involved in bringing up ideas. How we make sure that everybody’s voice is heard…that has been very important to me. And that is one skill that I learned from this course” (P3) | |

| “I understand now complex systems and I can apply it into my own world rather than looking at, starting over. I’m looking at those fine-tuning opportunities and gaining feedback from staff, making decisions based on a collective approach.” (P6) | ||

| Solution focused mind-set | “how a small change can have a big impact” (P6). | |

| “We so often get stuck in these giant projects that are not changing the right thing. And so, I think I’ve started questioning how things are done and it’s encouraged other people to do the same.” (P3) | ||

| “Now I am able to think more broadly and apply different principles to resolve solutions that I’d never thought of before. So, trying to be a little bit more creative in what I do. We were able to work as a team to come up with a solution and innovative solution to a healthcare problem…fostered our innovation and thinking and really encouraging us to think outside the box” (P4) |

Reasons for taking the Leadership for Health Systems Transformation certificate searching for innovative approaches to graduate studies

Participants noted the innovative, blended, and stackable (where standalone certificates can stack together to offer a masters degree) approach to graduate studies as being a key reason for enrolling in the program. Many participants mentioned the stackable certificate program was different from any other advanced nursing program they had seen offered elsewhere. They expressed value in having a leadership certificate offered through a university.

Opening the doors to new opportunities

Graduate education was viewed as a way to gain personal and professional credibility. Some participants enrolled in graduate education to be aligned with other professions. Others noted the need to have graduate education to be taken more seriously. For some students, graduate education was always on the horizon while others viewed the program as a way to open the door to more formalized leadership roles.

Increasing leadership knowledge and capacity

Participants indicated a desire to increase their leadership knowledge and capacity. Some students were already in formal and informal leadership roles which sparked their interest in learning more about leadership while others saw leadership opportunities in their future.

All students indicated they wanted to build their leadership toolkits to help make real and relevant changes in their workplaces.

Positive aspects of the healthcare grand challenge course

Real-world applicability

Students appreciated the real-world applicability of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course. They were able to apply course learnings to their immediate roles in the healthcare systems where they work. Students appreciated the experiential and authentic learning opportunities and course assignments that aligned with relevant issues that were occurring in their practice areas.

Opportunities to engage with stakeholders

The students appreciated the opportunity to engage with stakeholders to help clarify ideas, identify solutions, and find a common way forward. The time spent with stakeholders was invaluable and became a valued skill that was developed throughout the course. Integrating purposeful opportunities to connect with healthcare stakeholders is not commonly part of clinical nursing practice or graduate education.

Relational approach to group work and interactivity

The Healthcare Grand Challenge course was purposefully designed to foster collaborative learning. Students identified that working together with a diverse group of people enriched their learning experiences. The collaborative learning strategies fostered a supportive learning culture. The supportive peer relationships created space to seek feedback and ask questions to upon which to build on each others’ perspectives. This course role-modeled the collaboration and professionalism that is required of nurse leaders in today’s complex healthcare environments.

Skills development

As part of the course, students identified a number of leadership skills they developed and nurtured. The most noted leadership skill developed was listening and making sure everyone’s voice was heard. The Healthcare Grand Challenges course allowed students to use the skills that had been developed throughout the year and provided real-world opportunities for students to put their leadership skills into practice within a supportive and experiential learning environment.

Lessons learned

Learning through vagueness

Instead of the instructor directing the learning and the learner being a passive recipient, a collaborative approach was used to foster new and innovative ways of thinking and learning. This was purposeful by design, however, students initially struggled with the ambiguity. As this was the first offering of the course and a significant departure from more traditional ways of teaching and learning, it was important to establish trust between the teachers and the learners and between the learners themselves. The course provided the skills development necessary to navigate their way through uncertainty and learn by doing.

Setting the stage for innovative education

Innovative education requires some vulnerability for both the teachers and the learners. Students noted it is important to create a safe space for learning to occur. Grand challenge courses that incorporate design sprints move quickly and require instructors to model an innovative mindset for a course of this nature and be more available to the students than a traditional learning environment. While creating a safe learning environment that fostered innovative thinking was considered important, students also noted a need to understand the endpoint of the design thinking process and to see firsthand how nurse leaders were using design thinking in practice.

Increase connection points with peers and stakeholders

Learners valued the real-world learning that resulted from the connecting with representatives from within the healthcare industry. Students desired more opportunities to connect with both their peers and healthcare leaders. Many learners expressed the camaraderie that resulted among peers and instructors as a direct result of the Grand Challenge learning opportunity, yet some wanted more opportunities to talk through some of their learnings.

Impact of the pandemic

The impact of the evolving COVID-19 pandemic presented new and unforeseen challenges that prompted unconventional alternatives for the teaching and learning experience. Instructors needed to be flexible in modifying course delivery, assignments, and due dates. It was important to acknowledge the students were all RNs working full time during a pandemic that was placing extraordinary strain on the nursing workforce. For the students, these forced changes resulted in some challenges to their learning experiences. Because the Healthcare Grand Challenge course was the final course in a one year, cohort-based program, the students had face-to-face immersion days prior to the pandemic, and noted the challenges and differences in moving to a completely remote learning environment. Given one of the course learning objectives was to demonstrate effective relational leadership competencies, the lack of occasions to give face-to-face presentations was a notable missed learning opportunity.

Impact on current and future nursing practice

Discovering new horizons

Learners expressed how the certificate helped them to see the health care system, and nurses’ roles within the healthcare system differently. Others described a new systems-level view, where small changes can have system level impacts. This helped clarify the role of nurse as innovative leader within the healthcare system. The students shared how seeing the healthcare system from new horizons would help them make better informed decisions as nursing leaders.

Embracing lifelong learning

Students were interested in learning skills they could apply in their day-to-day nursing roles. Engaging in the certificate fostered a love for lifelong learning and an understanding of the benefits associated with continual learning and growth. The students were clear that the learning obtained through this program would continue to be used in their nursing practice while opening opportunities for continued growth and development.

Increasing awareness of self as leader

Learners became more aware of their beliefs about leadership and how to harness their leadership strengths and put them into practice. This increased self-awareness helped them to identify common leadership behaviours and recognize the type of leader they strived to become.

The Healthcare Grand Challenge course was the final of four courses where the students were able to build on the leadership skills developed throughout the certificate and put these new skills to practice in a real-world challenge. Through the final design sprint, students became more self-aware of themselves as a leader with a deeper understanding of the applicability and relevancy of these skills settings and challenges.

Seeking diverse voices and perspectives

The level of collaboration and sharing among peers, colleagues, and stakeholders was highly valued among the learners. There was a new appreciation for the value of seeking varied perspectives to understand problems more completely. Some students highlighted how they incorporated this strategy into their current work setting. The skills of collaboration and seeking out a variety of perspectives was a key learning for all participants. They expressed that this skills set will enable them to make small and large changes withing their areas of practice.

Solution focused mind-set

Learners experienced a transformation from problem-based thinking to that of a solution-focused and problem-solving approach. Students noted they were able to look at challenges from a different perspective and ask important questions to address small pieces of the big problem to keep moving change in the right direction. Students also spoke about their new-found ability to be creative problem solvers and think more innovatively about how challenges are addressed. The solution focused mindset shifted the way students looked at problems and viewed their potential to make positive changes in their workplaces.

Discussion

The purpose of this pilot study was to explore nursing graduate students’ experiences and perceptions of a healthcare grand challenge course. Students had a variety of reasons for taking the Leadership in Healthcare Transformation certificate and identified both positive and challenging aspects inherent within the Healthcare Grand Challenge course. Participants identified some key lessons learned for future offerings and shared how the Healthcare Grand Challenge course influenced their current and future nursing practice.

In this pilot study, students enrolled in the program because they were seeking an innovative, blended, and stackable approach to their graduate studies. Nurses are experiencing advancements in knowledge and technology within nursing practice that have motivated them to seek alternate forms of credentialing in nursing education. Students also appreciated the real-world applicability of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course. In the course, students used a design-thinking process that was creative and analytic to engage in opportunities to prototype ideas, gather feedback from stakeholders and peers, and redesign their ideas to address the identified grand challenge. The use of authentic grand challenges, in combination with a design thinking assignment helped students develop advanced problem-solving skills. Glen, Suciu, Baughn, and Anson (2015), suggested that design-thinking projects can accelerate learning, build confidence in solving complex problems, and enhance the ability to engage with diverse perspectives. Design-thinking projects can also advance the development of innovation, communication, and collaboration skills that are transferable to professional settings (Benson & Dresdow, 2015). These are transferable skills to the complex environments in which they work. However, more clarity around instructions and end goals may have provided students with more structure, which they desired.

The students in the study also identified the benefits of engaging with healthcare stakeholders to understand the challenge and pressure points more thoroughly. By purposefully incorporating diverse perspectives into course, students were able explore the various viewpoints from multiple stakeholders and assess their thinking against the perspectives of others. Others have identified the importance of opportunities to engage with high-level industry-related challenges that require thoughtful, viable and fiscally responsible solutions (Bleich & Jones-Schenk, 2018a) and explore through discovery, the real-world, time-sensitive challenges that impact nursing practice and care environments (Bleich & Jones-Schenk, 2018b). Within the context of certificate courses and more specifically grand challenge courses, learners can strengthen their leadership skills by exploring with stakeholders, ways to successfully address challenges (Craven & DuHamel, 2021) and develop synthesized solutions while building professional and personal skills (Jones, 2009). Designing courses that require collaborative problem solving in conjunction with key stakeholders is also a great way to promote interdisciplinary learning (Francis, Henderson, Martin, Saul, & Joshi, 2018). These are important considerations for those seeking to create or adapt future grand challenge courses. In future offerings, more purposeful opportunities to connect students and stakeholders over a longer period of time should be explored to meet the desired needs of students who required more connection.

Participants also identified a number of leadership skills developed through the course. Professional and personal skills development is a common course objective in grand challenge courses (Nowell et al., 2020). Incorporating collaborative pedagogical activities and techniques such as grand challenge projects and group presentations may help increase skill development more broadly. Course assignments such as presentations and dynamic discussions can help build key communication skills that are important for future nurse leaders. Although the pandemic was an unforeseen challenge, in future course offerings when face-to-face teaching and learning is safe, it will be important to incorporate live presentations to help build these important leadership skills.

Implications for development of certificate programs and grand challenge courses

The development of certificate-based courses requires participation and contribution from key stakeholders within the healthcare industry, academic institutions, nursing organizations and government agencies (Moore, 2020). Educators seeking to develop and teach grand challenge courses need to approach the teaching experience with an innovative and creative mindset to set these courses apart from the traditional teacher-directed learning styles of pedagogy and andragogy (Agonács & Matos, 2019). The foundational aspect of certificate courses requires both the educator and the student to be innovative, flexible, open to new ideas, and solution-focused, which describes the nature of heutagogy (Canning, 2010). The nature of certificate courses fosters learning wherein students embark on a self-directed, curiosity-led journey while educators act as signposts to guide the context and relevancy of learning as it relates to the current socio-political situations facing the healthcare industry (Craven & DuHamel, 2021).

Nursing education, and more importantly, nursing curricula must keep abreast of changes in the healthcare system to foster the development of effective and industry-ready nurse leaders (Caputi, 2017). The demands of the ever-changing healthcare industry require RNs to be adequately prepared and equipped to be the leaders of innovation and innovative nursing practice (Melnyk & Davidson, 2009). Practicing nurses are on the frontline of the increasing complexities in the healthcare system and are aware of the need for innovation and new ways of thinking. The new blended and stackable approach to graduate education allows for learning opportunities that align with the needs of practicing nurses. Providing innovative learning modalities for practicing nurses is important for maintaining excellence in nursing practice (Lindsay et al., 2017). Stackable certificates represent a win-win opportunity that has a positive multilayered impact on the healthcare system and the nurses who serve and lead within these systems (O’Neil & Fisher, 2019).

Strengths and limitations

The results of this pilot study need to be understood within the context of study limitations. We were limited to sampling graduate nursing students who completed the Healthcare Grand Challenge course and participants self-selected, potentially limiting the representation of graduate nursing students’ perspectives. Another limitation is the very small sample size from a single institution. A larger sample from a variety of grand challenge courses at various institutions would strengthen the trustworthiness of the study. Furthermore, some members of our research team were also directly involved in the delivery of the Healthcare Grand Challenge course and acknowledge the potential influence of these dual roles as a study limitation.

Future research

Research regarding the implementation of graduate stackable certificates and grand challenges in higher education is in its infancy and continues to be an underexplored area of inquiry. Currently there is no experimental, quasi-experimental, or longitudinal research on this topic. Comparative studies could help identify effective approaches to designing and implementing graduate certificates and grand challenges in graduate education. Future research should explore the longitudinal aspects of completing these types of programs, comparing results from various certificates, as well as those who complete one vs. two certificates, and/or the entire Master of Nursing laddered certificate pathway and how the order of completion influences the overall learning experience.

Conclusions

To date, research about integrating stackable graduate certificates and healthcare grand challenges into Canadian graduate nursing curricula has not been explored. Understanding graduate nursing students’ perceptions of a certificate program and more specifically a grand challenge course helped identify strengths and areas for future growth within graduate nursing curricula. The findings from this pilot study help advance theoretical understanding of graduate certificate programs and healthcare grand challenges related to graduate nursing student learning and provide evidence for the healthcare grand challenge model to be used by other nursing graduate programs. This evidence is valuable not only to students and nursing education institutions, but to institutional decision-makers and the healthcare systems where the nursing leaders play pivotal roles.

Funding source: Western North-Western Region Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing Education Innovation Grant

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in this study.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by a Western North-Western Region Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing Education Innovation Grant.

-

Author contributions: LN, SD, and EC were responsible for the conceptualisation of the research question, approach, and rationale. SD conducted the data collection. LN, SC, and SD analyzed the data. LN prepared the first draft of the manuscript, which was reviewed and revised by SD, SC, SD, and EC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Informed consent: Students were invited to participate only after course completion and grades were submitted prior to interviews to ensure voluntary participations without any impact on student grades. All participants provided informed verbal and written consent prior to being interviewed.

-

Ethical approval: Permission to conduct this research was granted through the local Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB19-2131).

References

Abraham, R. R., & Komattil, R. (2017). Heutagogic approach to developing capable learners. Medical Teacher, 39(3), 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270433.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Agonács, N., & Matos, J. F. (2019). Heutagogy and self-determined learning: A review of the published literature on the application and implementation of the theory. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and eLearning, 34(3), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2018.1562329.Search in Google Scholar

Bass, R. (2012). Disrupting ourselves: The problem of learning in higher education. Educational Review, 47(2), 1–14.Search in Google Scholar

Benson, J., & Dresdow, S. (2015). Design for thinking: Engagement in innovation project. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 13(3), 377–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12069.Search in Google Scholar

Bleich, M. R., & Jones-Schenk, J. (2018a). Alternative credentials for workforce development. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 49(10), 449–450. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20180918-03.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bleich, M. R., & Jones-Schenk, J. (2018b). Value-based academic partnerships. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 49(6), 248–250. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20180517-03.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Canning, N. (2010). Playing with heutagogy: Exploring strategies to empower mature learners in higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 34(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770903477102.Search in Google Scholar

Caputi, L. J. (2017). Innovation in nursing education revisited. Nursing Education Perspectives, 38(3), 112. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000157.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Craven, R. F., & DuHamel, M. B. (2021). Certificate programs in continuing professional education. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 34(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.3928/0022-0124-20030101-04.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36, 363–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614563742.Search in Google Scholar

Francis, K., Henderson, M., Martin, E., Saul, K., & Joshi, S. (2018). Collaborative teaching and interdisciplinary learning in graduate environmental studies. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8(3), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-017-0467-0.Search in Google Scholar

Glen, R., Suciu, C., Baughn, C. C., & Anson, R. (2015). Teaching design thinking in business schools. International Journal of Management in Education, 13(2), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2015.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

Grand Challenges Canada. Retrieved from https://www.grandchallenges.ca/.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, C. (2009). Interdisciplinary approach – advantages, disadvantages, and the future benefits of interdisciplinary studies. ESSAI, 7(26), 76–81.Search in Google Scholar

Klockner, K., Shields, P., Pillay, M., & Ames, K. (2021). Pragmatism as a teaching philosophy in the safety sciences: A higher education pedagogy perspective. Safety Science, 138, 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105095.Search in Google Scholar

Larson, K., Downing, M., & Nolan, J. (2020). High impact practices through experiential student philanthropy: A case study of the Mayerson student philanthropy project and academic success at Northern Kentucky University. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120952083.Search in Google Scholar

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8Search in Google Scholar

Lindsay, J. M., Oelschlegel, S., & Earl, M. (2017). Surveying hospital nurses to discover educational needs and preferences. Surveys and Studies, 105(3), 226–232. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.85.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Melnyk, B. M., & Davidson, S. (2009). Creating a culture of innovation in nursing education through shared vision, leadership, interdisciplinary partnerships, and positive deviance. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 33(4), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3181b9dcf8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Moore, R. L. (2020). Developing lifelong learning with heutagogy: Contexts, critiques, and challenges. Distance Education, 41(3), 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1766949.Search in Google Scholar

Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nowell, L., Norris, J., White, D., & Moules, N. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847.Search in Google Scholar

Nowell, L., Dhingra, S., Andrews, K., Gospodinov, J., Liu, J., & Hayden, K. A. (2020). Grand challenges as educational innovations in higher education: A scoping review of the literature. Educational Research International, 2020, 1–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6653575.Search in Google Scholar

Nurius, P. S., Coffey, D. S., Fong, R., Korr, W. S., & McRoy, R. (2017). Preparing professional degree students to tackle grand challenges: A framework for aligning social work curricula. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1086/690562.Search in Google Scholar

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

O’Neil, C., & Fisher, C. (2019). The impact of new directions on teaching and learning. In C. A. O’Neil, C. A. Fisher, & M. J. Rietschel (Eds.), Developing online courses in nursing education (pp. 11–20). New York: Springer.Search in Google Scholar

Osborne, B., Carpenter, S., Burnette, M., Rolheiser, C., & Korpan, C. (2014). Preparing graduate students for a changing world of work. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 44(3), i–ix. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v44i3.186033.Search in Google Scholar

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Roberts, J. (2018). The possibilities and limitations of experiential learning research in higher education. Journal of Experiential Education, 41(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825917751457.Search in Google Scholar

Vest, C. M. (2008). Context and challenge for twenty-first century engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education, 97(3), 235–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2008.tb00973.x.Search in Google Scholar

Weberg, D., & Davidson, S. (2021). Leadership for evidence-based innovation in nursing and health professions (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jone & Bartlett Learning.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Lorelli Nowell et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Global inequity in nursing education: a call to action

- Research Articles

- Nursing students’ experiences and perceptions of an innovative graduate level healthcare grand challenge course: a qualitative study

- Quality of life and academic resilience of Filipino nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study

- Nursing students’ adverse childhood experience scores: a national survey

- Depression, anxiety and stress among Australian nursing and midwifery undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study

- Development and psychometric evaluation of the motivation for nursing student scale (MNSS): a cross sectional validation study

- The assessment and exploration of forensic nursing concepts in undergraduate nursing curricula: a mixed-methods study

- New nurse graduates and rapidly changing clinical situations: the role of expert critical care nurse mentors

- Nursing students’ experiences of virtual simulation when using a video conferencing system – a mixed methods study

- A mixed-methods assessment of the transition to a dedicated educational unit: nursing students’ perceptions and achievements

- Nursing student and faculty attitudes about a potential genomics-informed undergraduate curriculum

- Factors that influence the preceptor role: a comparative study of Saudi and expatriate nurses

- Testing and e-learning activity designed to enhance student nurses understanding of continence and mobility

- Incivility among Arabic-speaking nursing faculty: testing the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of incivility in nursing education-revised

- Understanding clinical leadership behaviors in practice to inform baccalaureate nursing curriculum: a comparative study between the United States and Australia novice nurses

- A deep learning approach to student registered nurse anesthetist (SRNA) education

- Developing teamwork skills in baccalaureate nursing students: impact of TeamSTEPPS® training and simulation

- Preparing ABSN students for early entry and success in the clinical setting: flipping both class and skills lab with the Socratic Method

- Virtual clinical simulation in nursing education: a concept analysis

- COVID-19 pandemic and remote teaching: transition and transformation in nursing education

- Development and validation of the nursing clinical assessment tool (NCAT): a psychometric research study

- Becoming scholars in an online cohort of a PhD in nursing program

- Senior BSN students’ confidence, comfort, and perception of readiness for clinical practice: the impacts of COVID-19

- Relational and caring partnerships: (re)creating equity, genuineness, and growth in mentoring faculty relationships

- Comparison of simulation observer tools on engagement and maximising learning: a pilot study

- Gamification in nursing literature: an integrative review

- A conceptual framework of student professionalization for health professional education and research

- Writing a compelling integrated discussion: a guide for integrated discussions in article-based theses and dissertations

- Teaching evidence-based practice piece by PEACE

- Educational Process, Issue, Trend

- Increasing student involvement in research: a collaborative approach between faculty and students

- Capacity building in nurse educators in a Global Leadership Mentoring Community

- Psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner student perceptions of integrated collaborative care

- Igniting the leadership spark in nursing students: leading the way

- Quilting emergent advanced practice nursing educator identity: an arts-informed approach

- The expanding role of telehealth in nursing: considerations for nursing education

- Literature Reviews

- What do novice faculty need to transition successfully to the nurse faculty role? An integrative review

- Reflective writing pedagogies in action: a qualitative systematic review

- Appraisal of disability attitudes and curriculum of nursing students: a literature review

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial

- Global inequity in nursing education: a call to action

- Research Articles

- Nursing students’ experiences and perceptions of an innovative graduate level healthcare grand challenge course: a qualitative study

- Quality of life and academic resilience of Filipino nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study

- Nursing students’ adverse childhood experience scores: a national survey

- Depression, anxiety and stress among Australian nursing and midwifery undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study

- Development and psychometric evaluation of the motivation for nursing student scale (MNSS): a cross sectional validation study

- The assessment and exploration of forensic nursing concepts in undergraduate nursing curricula: a mixed-methods study

- New nurse graduates and rapidly changing clinical situations: the role of expert critical care nurse mentors

- Nursing students’ experiences of virtual simulation when using a video conferencing system – a mixed methods study

- A mixed-methods assessment of the transition to a dedicated educational unit: nursing students’ perceptions and achievements

- Nursing student and faculty attitudes about a potential genomics-informed undergraduate curriculum

- Factors that influence the preceptor role: a comparative study of Saudi and expatriate nurses

- Testing and e-learning activity designed to enhance student nurses understanding of continence and mobility

- Incivility among Arabic-speaking nursing faculty: testing the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of incivility in nursing education-revised

- Understanding clinical leadership behaviors in practice to inform baccalaureate nursing curriculum: a comparative study between the United States and Australia novice nurses

- A deep learning approach to student registered nurse anesthetist (SRNA) education

- Developing teamwork skills in baccalaureate nursing students: impact of TeamSTEPPS® training and simulation

- Preparing ABSN students for early entry and success in the clinical setting: flipping both class and skills lab with the Socratic Method

- Virtual clinical simulation in nursing education: a concept analysis

- COVID-19 pandemic and remote teaching: transition and transformation in nursing education

- Development and validation of the nursing clinical assessment tool (NCAT): a psychometric research study

- Becoming scholars in an online cohort of a PhD in nursing program

- Senior BSN students’ confidence, comfort, and perception of readiness for clinical practice: the impacts of COVID-19

- Relational and caring partnerships: (re)creating equity, genuineness, and growth in mentoring faculty relationships

- Comparison of simulation observer tools on engagement and maximising learning: a pilot study

- Gamification in nursing literature: an integrative review

- A conceptual framework of student professionalization for health professional education and research

- Writing a compelling integrated discussion: a guide for integrated discussions in article-based theses and dissertations

- Teaching evidence-based practice piece by PEACE

- Educational Process, Issue, Trend

- Increasing student involvement in research: a collaborative approach between faculty and students

- Capacity building in nurse educators in a Global Leadership Mentoring Community

- Psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner student perceptions of integrated collaborative care

- Igniting the leadership spark in nursing students: leading the way

- Quilting emergent advanced practice nursing educator identity: an arts-informed approach

- The expanding role of telehealth in nursing: considerations for nursing education

- Literature Reviews

- What do novice faculty need to transition successfully to the nurse faculty role? An integrative review

- Reflective writing pedagogies in action: a qualitative systematic review

- Appraisal of disability attitudes and curriculum of nursing students: a literature review