Kinetic studies on the cure reaction of hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene based polyurethane with variable catalysts by differential scanning calorimetry

-

Ma Hui

, Liu Yu-Cun

Abstract

This paper employs differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to investigate the reactions of hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene (HTPB) binder and isophorone isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI) with two different cure catalysts, namely, dibutyl tin dilaurate (DBTDL) and stannous octanoate (TECH). This study evaluates the effects of two cure catalysts (i.e. DBTDL and TECH) on rate constants of the polyurethane cure reactions. Throughput the study, the kinetic parameters and the curing reaction rate equations are obtained. The present work concludes that both catalysts had a catalytic effect on the HTPB-IPDI system, but that the catalytic effect of DBTDL was higher than that of TECH. The binder system with the TECH catalyst displayed a longer pot-life and lower toxicity compared with the DBTDL. Additionally, this study investigates the binder system’s viscosity build-up at 35°C and the viscosity build-up results were in agreement with the DSC analysis results.

1 Introduction

Hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene (HTPB) liquid prepolymer is widely used as a binder in preparing castable polymer bonded explosives (PBXs) and solid composite propellants (1), (2), (3). The polyurethane elastomer provides polymer-bonded explosives with better dimensional stability and structural integrity (3), (4), (5).

In previous reports (6), (7), (8), (9), (10), (11), (12), (13), studies on the curing kinetics of HTPB-isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI) binder system were focused mainly on the effects of dibutyl tin dilaurate (DBTDL), ferric tris-acetylacetonate (FeAA), triphenyl bismuth (TPB), etc. DBTDL has powerful catalytic effects on the reaction between isocyanate and alcohol, and is known as a gel catalyst. However, DBTDL is harmful for human beings and ecosystems (14), (15), (16), (17), (18). The pot-life of the binder system is relatively short when FeAA is used as a catalyst. Moreover, solid settling may occur as the curing process is relatively slow when TPB is used as a catalyst. To the best of our knowledge, no investigations thus far have explored the catalytic effect of TECH in the HTPB-IPDI binder system. Compared with DBTDL, TECH is more environmentally friendly, less toxic, and exhibits a longer pot-life when used in a binder system.

Out of a variety of methods for studying curing kinetics (6), (9), (10), (19), (20), (21), thermal analysis is one of the most important. Thermo gravimetric (TG), differential thermal analysis (DTA), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) have been widely used to calculate kinetic parameters in thermal analysis (22). Of these methods, the DSC method has the broadest applicability. The curing reaction of the HTPB-based binder system is a continuous exothermic process. Therefore, the non-isothermal DSC method can be used to study the curing kinetics of the HTPB-based system. And viscometer was utilized to measure the viscosity changes and verify the DSC results.

In this study, the DSC and viscosity build-up methods are utilized to investigate the curing kinetics of HTPB-IPDI binder systems when DBTDL and TECH are used as catalysts. Kinetic parameters, which are crucial for deducing the curing kinetics equation of the binder system, were obtained. Once the curing kinetics equation is solved, it is possible to establish a relationship between curing degree and curing time, which plays a key role in binder system formula design.

2 Experiment

2.1 Materials

HTPB (number-average molecular weight=2700 g/mol, hydroxyl value=45.2 mg KOH/g) was obtained from the Liming Research Institute of the Chemical Industry (China). The curing agent IPDI was supplied by BASF Corp (Germany). The catalyst stannous isooctoate (TECH) was purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry (China). DBTDL was provided by the Tianjin Guang Fu Institute of Fine Chemicals (China). Prior to the test, the HTPB was dehydrated in a vacuum for 2 h at 100°C and 0.05 Mpa, and then put in a dry, sealed bottle.

The SNB-1A digital viscometer was obtained from the Shanghai Fang Rui Instrument Co (China). The DHG303-2 oven thermostat was obtained from the Shanghai Yi Heng Scientific Instrument Co (China). The HCT-1 integrated thermal analyzer was obtained from the Beijing Permanent Scientific Instrument Factory (China).

2.2 Experimental method

The binder system was prepared by mixing HTPB prepolymer and IPDI curing agent with two different cure catalysts viz. DBTDL and stannous octoate (TECH). The mix ratio was 100/9.25/0.109 parts by weight (pbw). About 10 mg of the sample mixture was placed into aluminum crucibles. The DSC operated in a temperature range between room temperature and 350°C under a nitrogen atmosphere with a ventilation of 50 ml/min. Four different heating rates (2.5, 5, 10 and 15°C/min) were employed in the DSC analysis.

2.3 DSC cure kinetics

The non-isothermal DSC kinetics analysis methods have two main components (22): an exothermic curve analysis must be used exclusively; exothermic peak temperature along with heating rate change must be used to analyze the kinetic parameters. This paper adopted the second method for its analysis. Four different peak temperatures were utilized to calculate the kinetic parameters activation energy E, pre-exponential factor A, and relation order n through the Kissinger (23), Ozawa (24), and Crane methods (25).

Kissinger method:

where β is the heating rate; E is activation energy; A is the pre-exponential factor; R is the gas constant 8.314 J·mol−1·K−1; and T is the absolute temperature.

A plot of

Ozawa method:

where β is the heating rate; E is activation energy; A is the pre-exponential factor; R is the gas constant 8.314 J·mol−1·K−1; G(a) is the mechanism function and T is the absolute temperature.

A plot of lg β vs. T−1 from several DSC curves gave a straight line with a slope equal to

Crane method:

If

where β is the heating rate; E is the activation energy; A is the pre-exponential factor; R is the gas constant 8.314 J·mol−1·K−1; n is the reaction order and T is the absolute temperature.

A plot of lg β vs. T−1 from several DSC curves gave a straight line with slope equal to

The Kissinger method assumes that the mechanism function agrees with the n-order reaction model, whereas the Ozawa method does not need to assume the mechanism function. If the calculated activation energies from both methods are very close, it demonstrates that they agree with the n-order reaction mechanism function model.

There are two basic types of thermosetting resins mechanism functions (22):

n-level reaction model:

Differential expression

Integral expression

Autocatalytic reaction model:

Differential expression

From the previous report (26), the curing reaction mechanism function of a hydroxyl terminated polybutadiene (HTPB) and the isocyanate complies with the n-level reaction model.

Curing reaction kinetic equation:

Differential expression

Integral expression

where f(a) is the differential expression function mechanism; g(a) is the of the integral expression function mechanism; t is the reaction time and k is the reaction rate constants that obey the Arrhenius equation.

where A is the pre-exponential factor; E is the activation energy; R is the universal gas constant 8.314 J·mol−1·K−1 and T is the absolute temperature.

2.4 Viscosity build-up

In the curing process of HTPB-isocyanate binder system, viscosity increased as the reaction progressed. As curing degree increased, the binder system viscosity growth rate also increased. Moreover, viscosity increased rapidly near the gel point, and approached infinity when fully cured.

Because of these characteristics, an SNB-1A digital viscometer is employed to measure the viscosity build-up during the curing process of the HTPB-IPDI binder system in the absence of any catalyst, and in the presence of BDTDL and TECH as catalysts. Then, the results were compared with the DSC results.

3 Results and discussion

Table 1 shows the HTPB-IPDI system with DBTDL or TECH as a catalyst under cure reaction temperatures at different heating rates. The DSC reactions showed smooth exothermic curves. From Table 1, it can be seen that as the heating rate increased, the exothermic peak temperature shifted to a higher temperature, the exothermic peak steepened, the curing time shortened, and the heat release of the system increased. The reason for this phenomenon is that as temperature increases, heat release increases per unit time, total released heat is reduced, the exothermic peak becomes steeper, and the curing time is shortened. Additionally, the peak temperature shifts to a higher temperature (27).

DSC data of DBTDL catalyzed and TECH catalyzed HTPB-IPDI curing reaction.

| β/°C min−1 | T1i/°C | T1p/°C | T1f/°C | T2i/°C | T2p/°C | T2f/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 139.6 | 148.4 | 155.23 | 150.2 | 158.6 | 169.8 |

| 5 | 158.6 | 167.2 | 177.3 | 159.2 | 177.4 | 183.6 |

| 10 | 175.7 | 186.1 | 197.1 | 176.2 | 195.24 | 201.74 |

| 15 | 183.5 | 194.8 | 206.9 | 188.3 | 206.31 | 216.32 |

β: heating rate; Ti: the initial temperature; TP: the peak temperature; Tf: the final temperature; T1 and T2:the curing reaction temperature of DBTDL and TECH system.

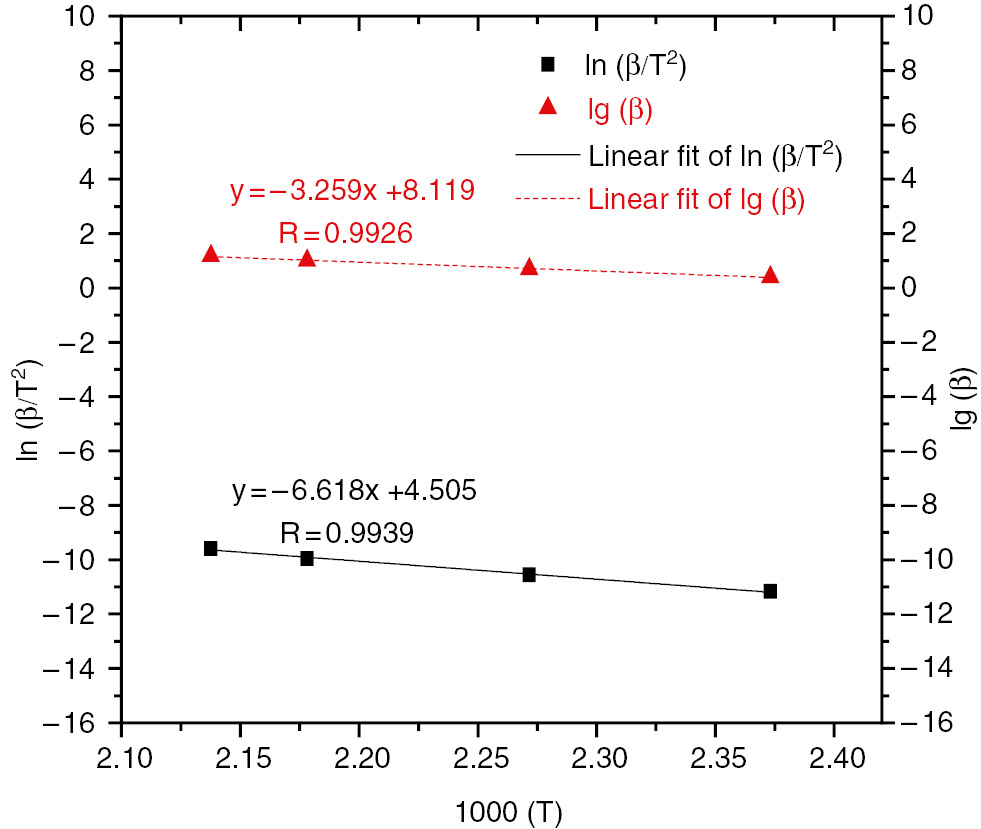

As for the HTPB-IPDI-DBTDL system, the Kissinger and Ozawa plots were utilized to compute the activation energies from DSC data, as Figure 1 shows. The value of activation energy (E) was 55.02 kJ·mol−1 from the Kissinger method and 59.33 kJ·mol−1 from the Ozawa method, and the value of the pre-exponential factor (A) was about 5.99×105 s−1. The correlation coefficients of the Kissinger and Ozawa plots were about 0.9939 and 0.9926, respectively. The reaction rate constant at 35°C equaled 2.79×10−4 s−1. The two activation energies were comparatively close, so it can be concluded that the function mechanism was accurate, and that the reaction conformed to the n-level reaction model.

Linear fitting of calculated lg(β) and ln (β/T2) with 1000/T for HTPB-IPDI-DBTDL system.

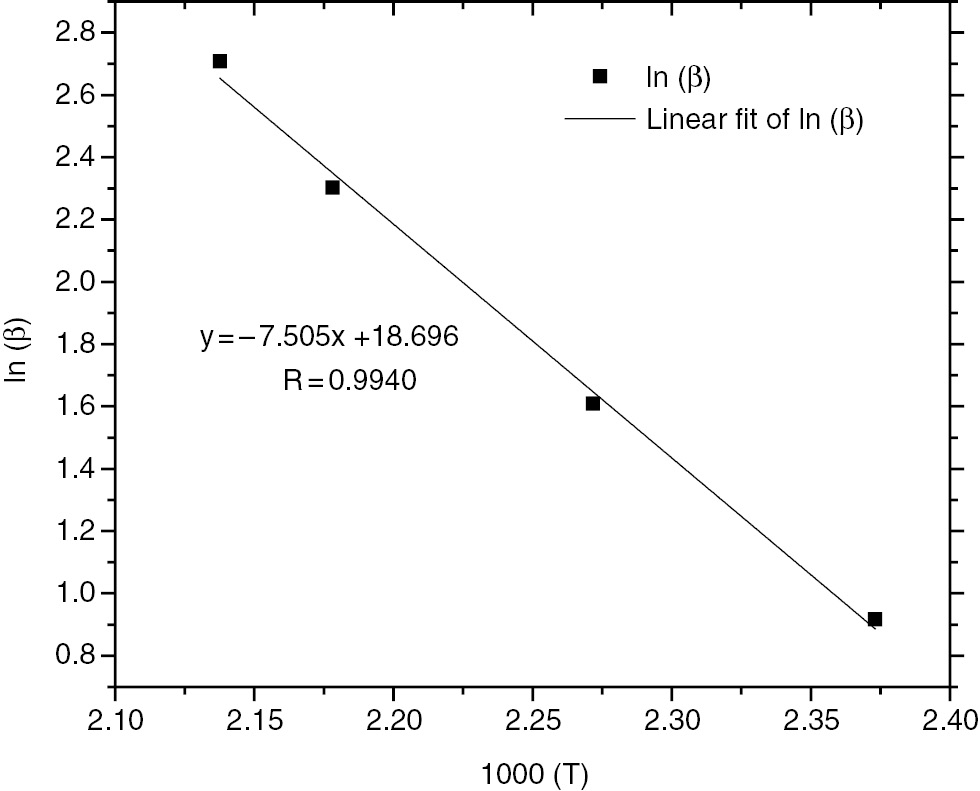

The Crane plot was obtained from the liner fit of ln(β) vs. 1/T, as Figure 2 shows. The correlation coefficient was approximately 0.9940. From Figure 2 and the Crane method, the kinetic order of reaction was found to be about 0.95 .

Linear fitting of calculated ln (β) with 1000/T for HTPB-IPDI-DBTDL system.

The curing kinetic equation of the HTPB-IPDI-DBTDL system can be written as:

where a1 is the cure degree; T1 is the absolute temperature; t1 is the curing time and k1 is the reaction rate constant at temperature T1.

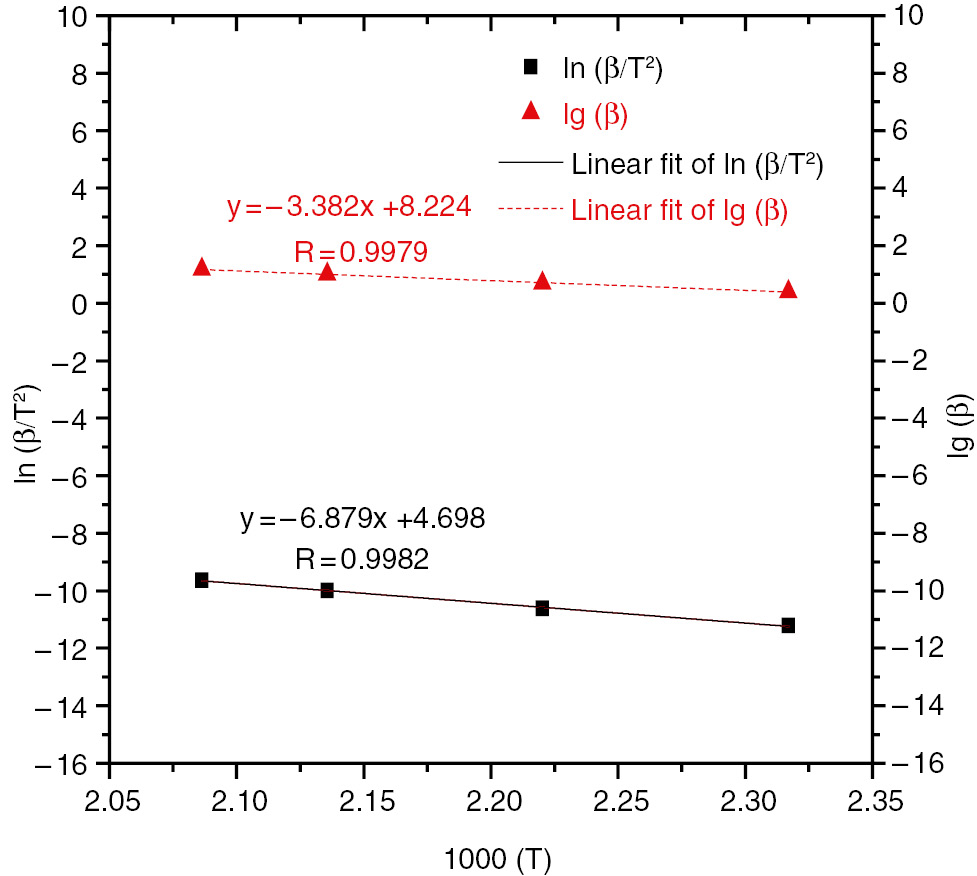

As for the HTPB-IPDI-TECH system, Kissinger and Ozawa plots were also used to calculate the activation energy and pre-exponential factor (A), as Figure 3 shows. The activation energy value was approximately 57.19 kJ·mol−1 (Kissinger method) and 61.57 kJ·mol−1 (Ozawa method), and the value of pre-exponential factor (A) was 7.55×105 s−1. The correlation coefficients of the Kissinger and Ozawa plots were about 0.9982 and 0.9979, respectively. The reaction rate constant at 35°C equaled 1.51×10−4 s−1. The two activation energies were comparative close, so it is possible to conclude that the function mechanism was accurate, and this reaction conformed to the n-level reaction model.

Linear fitting of calculated lnβ and ln (β/T2) with 1000/T for HTPB-IPDI-TECH system.

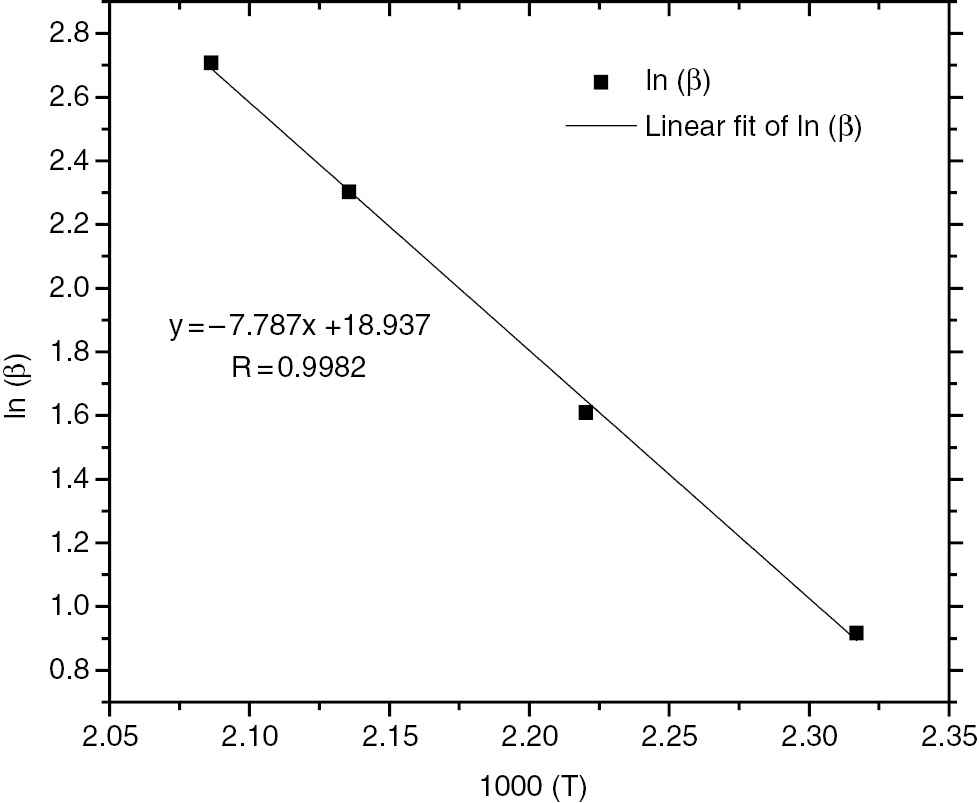

Similarly, the reaction order of the HTPB-IPDI-TECH system was about 0.95, as Figure 4 shows. The results confirm that the reaction mechanism function of the HTPB-IPDI binder system obeyed an n-level reaction model. The reaction order was 0.95. The addition of a catalyst did not change the reaction mechanism function (28), (29).

Linear fitting of calculated ln (β) with 1000/T for HTPB-IPDI-TECH system.

Therefore, the curing kinetics equation of the HTPB-IPDI-TECH system can be written as:

where a2 is the cure degree, T2 is the absolute temperature, t2 is the curing time, and k2 is the reaction rate constant at temperature T2.

Generally, activation energy E represents the required minimum reacted energy. As the activation energy declined, the reaction rate increased. However, this observation is not constant. In some conditions, as the activation energy declined, the reaction rate declined. This variation occurs due to a kinetic compensation effect that exists between activation energy E and pre-exponential factor A (7). Therefore, it is not feasible to make a comparison using the kinetic compensation amended E values to determine the reaction rate size (6). Measuring the value of curing reaction rate constant is a reasonable way to compare the catalytic effect of different catalysts for an HTPB-IPDI system.

As can be seen in Table 2, the reaction rate for KDBTDL=2.79×10−4 s−1 (when the catalyst is DBTDL) and for KTECH=1.51×10−4 s−1(when the catalyst is TECH). Therefore, the catalytic effect of DBTDL was higher than that of TECH in the curing reaction of the HTPB-IPDI system.

Kinetic parameters of catalyzed cure reactions of HTPB-IPDI system.

| System | Catalyst | E/kJmol−1 | A/s−1 | K(at 35°C)/S−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTPB-IPDI | DBTDL | 55.02 | 5.99×105 | 2.79×10−4 |

| TECH | 57.19 | 7.55×105 | 1.51×10−4 |

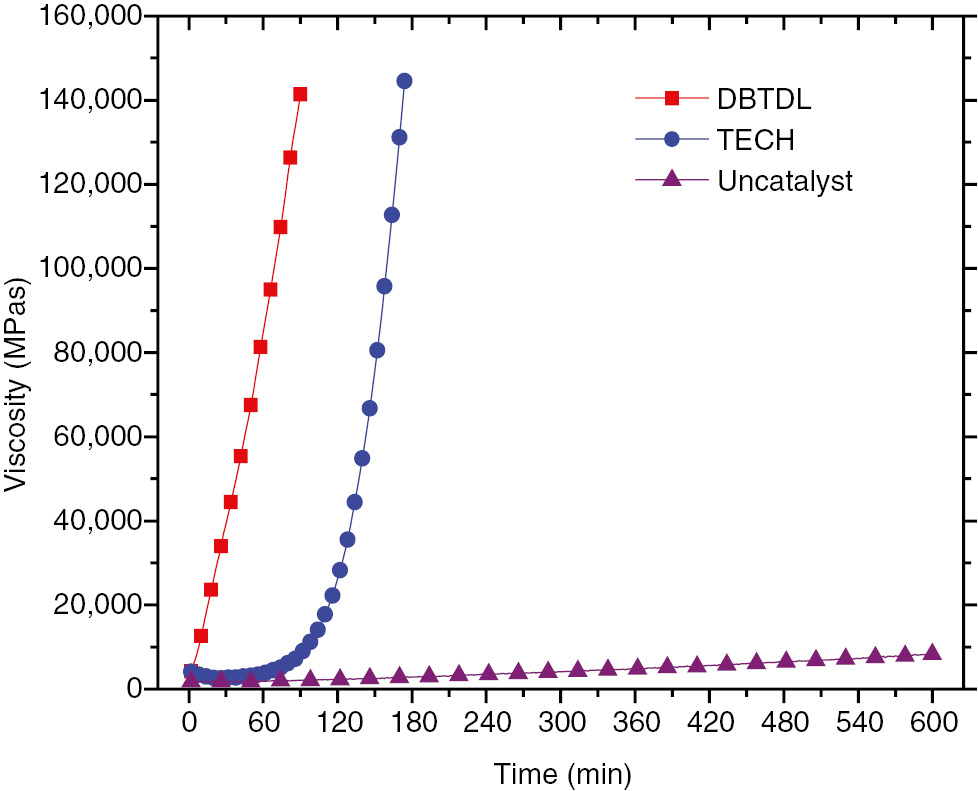

Figure 5 shows the viscosity build-up of the HTPB-IPDI binder system with DBTDL and TECH as catalysts at a curing temperature of 35°C. It can be found that the curing system’s viscosity build-up grew faster when DBTDL, rather than TECH, was added. For the HTPB-IPDI system, the catalytic activity of DBTDL was greater than that of TECH. The result is consistent with the DSC test results. In prior literature (11), the pot-life of the binder system is defined as the time it takes for the curing system to reach a viscosity level of 20,000 mPa·s. Using this definition, and under a curing temperature of 35°C, the pot-life of the HTPB-IPDI-DBTDL system is approximately 16 min, while the pot-life of HTPB-IPDI-TECH is approximately 114 min. When compared with DBTDL, it is evident that the pot-life of the HTPB-IPDI binder system is longer when TECH is added as a catalyst. Moreover, these results confirm the DSC analysis results.

Viscosity build-up of HTPB-IPDI binder system under the curing temperature of 35°C.

4 Conclusions

In this study, DSC and viscosity build-up methods are utilized to study the cure reactions of HTPB-IPDI-based polyurethane binder systems with different catalysts. The results of DSC analysis illustrate that the curing reactions of HTPB and IPDI, in the presence of catalysts DBTDL and TECH, follow n-level reaction kinetics. The addition of each catalyst did not alter the reaction mechanism function. Once the curing kinetics equations are solved, a functional relationship between curing degree and curing time is established. The results from DSC and viscosity methods confirm that the catalytic activity of DBTDL was greater than that of TECH in the cure reaction of the HTPB-IPDI binder system. From the results of viscosity build-up measurement under the same curing temperature, it is possible to conclude that the pot-life of HTPB-IPDI-TECH system was much longer than that of HTPB-IPDI-DBTDL system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSAF(Grant No U1330131).

References

1. Amrollahi M, Sadeghi GMM, Kashcooli Y. Investigation of novel polyurethane elastomeric networks based on polybutadiene-ol/polypropyleneoxide mixture and their structure-properties relationship. Mater Design. 2011;32(7):3933–394.10.1016/j.matdes.2011.02.039Search in Google Scholar

2. Gupta T, Adhikari B. Thermal degradation and stability of HTPB-based polyurethane and polyurethaneureas. Thermochim Acta. 2003;402(1–2):169–81.10.1016/S0040-6031(02)00571-3Search in Google Scholar

3. Sheikhy H, Shahidzadeh M, Ramezanzadeh B, Noroozi F. Studying the effects of chain extenders chemical structures on the adhesion and mechanical properties of a polyurethane adhesive. J Ind Eng Chem. 2013;19(6):1949–55.10.1016/j.jiec.2013.03.008Search in Google Scholar

4. Fuente JL. An analysis of the thermal aging behaviour in high-performance energetic composites through the glass transition temperature. Polym Degrad Stabil. 2009;94(4):664–9.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2008.12.021Search in Google Scholar

5. Lee S, Choi JH, Hong IK, Lee JK. Curing behavior of polyurethane as a binder for polymer-bonded explosives. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;21:980–5.10.1016/j.jiec.2014.05.004Search in Google Scholar

6. Catherine K, Krishnan K, Ninan K. A DSC study on cure kinetics of HTPB-IPDI urethane reaction. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2000;59(1–2):93–100.10.1023/A:1010127727162Search in Google Scholar

7. Bina CK, Kannan KG, Ninan KN. DSC study on the effect of isocyanates and catalysts on the HTPB cure reaction. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2004;78(3):753–60.10.1007/s10973-005-0442-0Search in Google Scholar

8. Hailu K, Guthausen G, Becker W, Konig A, Bendfeld A, Geissler E. In-situ characterization of the cure reaction of HTPB and IPDI by simultaneous NMR and IR measurements. Polym Test. 2010;29(4):513–9.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2010.03.001Search in Google Scholar

9. Yang PF, Yu YH, Wang SP, Li TD. Kinetic studies of isophorone diisocyanate-polyether polymerization with in situ FT-IR. Int J Polym Anal Charact. 2011;16(8):584–90.10.1080/1023666X.2011.622107Search in Google Scholar

10. Lucio B, Fuente JL. Rheokinetic analysis on the formation of metallo-polyurethanes based on hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene. Eur Polym J. 2014;50:117–26.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.10.013Search in Google Scholar

11. Haska SB, Bayramli E, Pekel F, Ozkar S. Mechanical properties of HTPB-IPDI-based elastomers. J Appl Polym Sci. 1997;64(12):2347–54.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970620)64:12<2347::AID-APP9>3.0.CO;2-LSearch in Google Scholar

12. Toosi FS, Shahidzadeh M, Ramezanzadeh B. An investigation of the effects of pre-polymer functionality on the curing behavior and mechanical properties of HTPB-based polyurethane. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;24:166–73.10.1016/j.jiec.2014.09.025Search in Google Scholar

13. Kincal D, Ozkar S. Kinetic study of the reaction between hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene and isophorone diisocyanate in bulk by quantitative FTIR spectroscopy. J Appl Polym Sci. 1997;66(10):1979–84.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19971205)66:10<1979::AID-APP14>3.0.CO;2-QSearch in Google Scholar

14. Grote K, Stahlschmidt B, Talsness CE, Gericke C, Appel KE, Chahoud I. Effects of organotin compounds on pubertal male rats. Toxicology 2004;202(3):145–58.10.1016/j.tox.2004.05.003Search in Google Scholar

15. Franklin SL, Geffner ME. Precocious puberty secondary to topical testosterone exposure. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2003;16(1):107–10.10.1515/JPEM.2003.16.1.107Search in Google Scholar

16. Reddy PS, Pushpalatha T, Reddy PS. Reduction of spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in mice after fentin and fenbutatin administration. Toxicol Lett. 2006;166(1):53–9.10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.05.012Search in Google Scholar

17. Parsons JK, Carter HB, Platz EA, Wright EJ, Landis P, Metter EJ. Serum testosterone and the risk of prostate cancer: potential implications for testosterone therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker Prev. 2005;14(9):2257–60.10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0715Search in Google Scholar

18. Iguchi T, Sato T. Endocrine disruption and developmental abnormalities of female reproduction. Am Zool. 2000;40(3):402–411.10.1093/icb/40.3.402Search in Google Scholar

19. Sultan W, Busnel J. Kinetic study of polyurethanes formation by using differential scanning calorimetry. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2006;83(2):355–9.10.1007/s10973-005-7026-8Search in Google Scholar

20. Singh M, Kanungo BK, Bansal TK. Kinetic studies on curing of hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene prepolymer-based polyurethane networks. J Appl Polym Sci. 2002;85(4):842–6.10.1002/app.10719Search in Google Scholar

21. Sekkar V, Krishnamurthy VN, Jain SR. Kinetics of copolyurethane network formation. J Appl Polym Sci. 1997;66(9):1795–801.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19971128)66:9<1795::AID-APP19>3.0.CO;2-USearch in Google Scholar

22. Liu ZH, Lu LL, Tang YW, editors. An introduction to thermal analysis, Beijing: Science press; 2012.Search in Google Scholar

23. Kissinger HE. Reaction kinetics in differential thermal analysis. Anal Chem. 1957;29(11):1702–6.10.1021/ac60131a045Search in Google Scholar

24. Ozawa T. A new method of analyzing thermogravimetric data. B Chem Soc Jpn. 1965;38(11):1881–6.10.1246/bcsj.38.1881Search in Google Scholar

25. Crane LW, Dynes PJ, Kaelble DH. Analysis of curing kinetics in polymer composites. J Polym Sci Polym Lett. 1973;11(8):533–40.10.1002/pol.1973.130110808Search in Google Scholar

26. Hu RZ, Gao SL, Zhao FQ, Shi QZ, Zhang TL, Zhang JJ, editors. Thermal analysis kinetics. 2nd ed. Beijing: Science press; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

27. Li CX, Dai YT, Hu XP, Zhang H, Zhou LP, Liu ZH. Curing kinetics of TiB2/epoxy resin E-44 system studied by non-isothermal DSC. Thermosetting Resin. 2011;26(3):6–10.Search in Google Scholar

28. Varghese A, Scariah KJ, Bera SC, Rao MR, Sastri KS. Processability characteristics of hydroxy terminated polybutadienes. Eur Polym J. 1996;32(1):79–83.10.1016/0014-3057(95)00116-6Search in Google Scholar

29. Chen CY, Wang XF, Gao LL, Zheng YF. Effect of HTPB with different molecular weights on curing kinetics of HTPB/TDI system. Chin J Energ Mater. 2013;21(6):771–6.Search in Google Scholar

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Editorial

- Innovations in polymers and composite materials

- Full length articles

- Preparation and properties of chemically reduced graphene oxide/copolymer-polyamide nanocomposites

- Synthesis and properties of well-defined carbazole-containing fluorescent star polymers of different arms

- The effect of high-current pulsed electron beam modification on the surface wetting property of polyamide 6

- Synthesis and application of waterborne polyurethane fluorescent composite

- Medicated structural PVP/PEG composites fabricated using coaxial electrospinning

- Research of the thermal aging mechanism of polycarbonate and polyester film

- Damage indication of 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein for epoxy polymer and the effect of water on its damage indicating ability

- Synthesis and characterization of thermosensitive and polarity-sensitive fluorescent PNIPAM-coated gold nanoparticles

- Comparative study of crystallization and lamellae orientation of isotactic polypropylene by rapid heat cycle molding and conventional injection molding

- Determination of deformation of a highly oriented polymer under three-point bending using finite element analysis

- Kinetic studies on the cure reaction of hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene based polyurethane with variable catalysts by differential scanning calorimetry

- Preparation and swelling properties of poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) composite hydrogels

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Editorial

- Innovations in polymers and composite materials

- Full length articles

- Preparation and properties of chemically reduced graphene oxide/copolymer-polyamide nanocomposites

- Synthesis and properties of well-defined carbazole-containing fluorescent star polymers of different arms

- The effect of high-current pulsed electron beam modification on the surface wetting property of polyamide 6

- Synthesis and application of waterborne polyurethane fluorescent composite

- Medicated structural PVP/PEG composites fabricated using coaxial electrospinning

- Research of the thermal aging mechanism of polycarbonate and polyester film

- Damage indication of 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein for epoxy polymer and the effect of water on its damage indicating ability

- Synthesis and characterization of thermosensitive and polarity-sensitive fluorescent PNIPAM-coated gold nanoparticles

- Comparative study of crystallization and lamellae orientation of isotactic polypropylene by rapid heat cycle molding and conventional injection molding

- Determination of deformation of a highly oriented polymer under three-point bending using finite element analysis

- Kinetic studies on the cure reaction of hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene based polyurethane with variable catalysts by differential scanning calorimetry

- Preparation and swelling properties of poly(acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) composite hydrogels