Abstract

People with visual impairment need a special form of audio-visual translation (AVT) to have access to multimedia products such as series and movies. Audio description (AD) is an AVT mode that describes what is happening in the images through words. It is a necessary accessibility tool that allows the blind and visually impaired to visualize scenes through spoken material. This study examines the types of information covered in the AD of the Jordanian Netflix drama series ‘Madrast Al-Rawabi LilBanat’ (AlRawabi School for Girls) following a corpus-assisted approach. Subsequent to watching the series and transcribing the verbal AD content, the researchers conducted frequency and concordance (KWIC) analyses using the Wordsmith 6 (WS6) software package to identify the categories of information covered in the AD. The findings showed six categories, namely description of characters, description of actions, interpersonal interactions, description of settings, emotional states, and on-screen texts. This study recommends conducting further research on AD in the Arab world to expand the accessibility services provided by official TV channels and streaming platforms.

Introduction

Globalization has affected translation to a large extent and paved the way for audio-visual translation (AVT). AVT is concerned with the translation in audio and/or visual settings, such as cinema, television, video games, and some live events, including opera performances (Díaz-Cintas and Remael). AVT modes include dubbing (Haider and Alrousan; Hayes; Silwadi and Almahasees), subtitling (Al-Zgoul and Al-Salman; Debbas and Haider; Haider et al.), voiceover (Díaz-Cintas and Orero), and audio description (AD) (Fryer), to mention a few.

AD, which is the focus of this study, is an AVT mode that explains what is happening in an image through words. This mode is sometimes utilized in movies, theatres, exhibitions, museums, and churches, among others. Moreover, some new mobile applications such as “Greta” provide people with ADs (Hättich and Schweizer). The “Greta” app enables the audience to experience fully accessible cinema by playing the existing AD at any time and place by using users’ smart devices. In other words, AD enables receivers to listen to the audio-described material and become familiarized with what happens on the screen as a part of social life engagement.

AD, also called video or visual description, is a relatively new concept worldwide that has attracted significant scholarly attention (Karantzi; UtRay et al.). Some streaming platforms, such as Netflix, provide AD service to their subscribers to support those who are visually impaired and have difficulty following on-screen actions. AD is considered an accessibility practice that provides an optional service primarily intended for the blind and visually impaired people (B/VIP). Accordingly, audio describers should be skilled to let the target audience, mainly B/VIP, enjoy the cinematic experience. In short, AD could be less effective if it does not follow a comprehensible systematic approach.

To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, few researchers have explored AD of Arabic movies and series (see Alnatsheh). This study qualitatively examines Season 1 of one of the most controversial six-episode Jordanian series, “AlRawabi School for Girls,” produced by Netflix using a corpus-assisted approach, i.e., combining the use of relatively large collections of authentic language data (corpora) with other analytical tools to investigate and understand language phenomena and make informed analyses and interpretations. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, only a few studies have been carried out using corpus-assisted methods on Arabic AD. Accordingly, using corpus techniques such as frequency, cluster, concordance, collocation, and keyword to investigate a corpus of AD is the gap that this study fills.

Ultimately, this study aims to examine the differences between the original version of the Jordanian Netflix drama series ‘Madrast Al-Rawabi LilBanat’ (AlRawabi School for Girls) and the version with AD by comparing the included information and expressions. Thus, the current study addresses the following question:

What aspects of visual content are covered in the audio-described version of AlRawabi School for Girls series?

Review of Related Literature

This section reviews the theoretical background of the current study by discussing the different AVT modes with a special focus on AD. It also reviews several empirical studies relevant to AD.

AD as a Mode of AVT

Translation is an essential field of study that deals with different genres and modes. It is an activity that transfers the meaning and style from the source text into the target text. According to Newmark (88), translation is “rendering the meaning of a text into another language in the way that the author intended the text.” The three types of translation are intralingual, interlingual, and inter-semiotic. Intralingual translation renders texts within the same language (Al-Abbas and Haider; Al-Abbas et al.). In interlingual translations, texts are made understandable for audiences unfamiliar with the original language (Al-Zgoul and Al-Salman; Aldualimi and Almahasees). Jakobson states that interlingual translation or “translation proper” converts verbal signs in one language to the verbal cues of another language. The third type is inter-semiotic, in which the verbal signs are interpreted using signs of a nonverbal sign system (Torop).

Due to the widespread use of Arabic in the Middle East and North Africa and the significance of Arabic as the language of the Holy Quran, Arabic–English translation and vice versa is a crucial area of study. Literary translation, scientific and technical translation, legal translation, and commercial translation are a few examples of the numerous kinds of translation between Arabic and English. For the translation to be successful, it requires a deep understanding of both languages and their cultural nuances. It is crucial for translators to be knowledgeable about tools and software used for translation, as well as staying current with the most recent advancements in the industry.

Due to the spread of audio-visual products, such as movies, television shows, series, video games, and advertisements and commercials, there has been an increasing demand to translate and localize them into different languages. This gives rise to a new field in translation studies, namely AVT, which has different modes, including AD (Haider and Hussein; Haider et al.; Samha et al.). Mazur (228) defines AD as “audio commentary that describes the relevant visual elements of work (as well as meaningful sounds that may not be clear to the target audience) so that the work constitutes a coherent whole for the audience.” AVT mode is popular in the United States, Japan, and several European countries, gaining recent popularity in the Middle East. Hyks pointed out that translation and AD are two thoroughly related activities. It could be said that the role of AD is turning visual information into verbal information, which helps people who are blind or have impaired vision understand movies and other audio-visual displays better.

The origins of AD can be traced back to 1981 in the United States, when Margaret and Cody Pfanstiehl, the founders of the Metropolitan Washington Ear, began providing listening services for the blind, visually impaired, and physically disabled people who could not read print properly in an effort to promote inclusivity (Snyder). The Pfanstiehls collaborated with Arena Stage for American Theatre to launch an AD of Major Barbara’s English Play. As AD began to be more widely adopted by various platforms and industries, improving differently abled people’s lives became a normal part of inclusion strategies. Previously, people with visual impairment relied heavily on their able-sighted friends to whisper comments to them about what was being performed on the theatre stage. This makes it clear that AD has impacted lives throughout history. AD could additionally be used for pedagogical purposes and requirements, as it raises awareness about disability and could further develop critical thinking skills in classrooms through a guided description of visual material (Kleege and Wallin; Schmeidler and Kirchner).

The purpose of AD in filmed programs and performances, such as movies, television programs, theatre, opera, dance performances, or football matches, is to convert the main visual aspects of a performance into an informative verbal description that explains the program or event. This is related to one of AD’s most essential goals, which is enabling blind and partially sighted viewers to enjoy audio-visual products.

AD can be controversial when applied to audio-visual products like movies and series because these products can be audio-described in many ways. Overall, audio-visual products have a far-reaching influence, so every aspect is carefully considered in the pre-production, production, and post-production stages. According to Piety, the first academic record of AD is found in a dissertation written in 1975 by Frazier, in which the author discusses AD as a way to enhance blind listeners’ comprehension.

Empirical Studies

This section reviews several studies that discuss AD services and how people with vision impairments reacted to them. Fels et al. compare the reactions of sighted and blind users to first-person-described video information and conventional (third-person) descriptions in relation to the animated Canadian sitcom Odd Job Jack. The research participants watched 10 min of four video clips, and the findings showed that all of the blind participants commended the video description, preferring the first-person style to the conventional one.

In the same vein, Arma adopts a corpus-assisted approach to syntactically and lexically analyze Italian and English audio-described scripts of the movie Chocolat. Using quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze the texts using AntConc software provides reliable results for corpus-driven text analysis. Examples of sentence structure, relevance, and objectivity are retrieved manually. The results show that the Italian script contains a higher number of secondary clauses when compared to English. Arma recommends further research on the hearing habits of the visually impaired community to determine the audience’s satisfaction with different approaches to AD.

Similarly, Vermeulen and Ibáñez Moreno examine AD as a tool for intercultural competence (ICC) by emphasizing AD as a culture-based translating activity and implementing it in foreign language classes. The study participants included 153 Belgian 3-year university students studying languages. The participants explored the benefits of using AD in the foreign language classroom, which promoted ICC. The study found that AD proves to be a helpful pedagogical tool to raise intercultural awareness, creating a link between “what we see” and “how we describe what we see.”

Walczak explores the impact of Polish AD on the immersion of the B/VIP consumers of this service. Two studies are conducted focusing on AD style and AD vocal delivery. The first research studied the standard and creative AD styles used by blind and visually impaired users. The second study, linked to AD vocal delivery, studied the reception of two AD voice types – human and synthetic, by the blind and visually impaired users for documentary and fiction movie genres. A questionnaire targeting a total of 72 participants was used to measure their engagement when exposed to different media. The results show that creative AD prompted significantly higher levels of presence for all participants than standard AD, and AD vocal delivery favored AD narrated by a human about a fictional story. On the other hand, presence rates for documentary clips were similar, with no statistically noteworthy differences in AD voice type: human and synthetic, which validate the hypotheses.

Likewise, Alnatsheh questions whether Arabic movies could have dialectal audio descriptions (DADs). The study includes quantitative and qualitative approaches, investigating the target audience’s preferences and determining if Qatari DAD can create an immersive environment. Two AD versions of the short Qatari movie Sh’hab are provided: one in modern standard Arabic (MSA) and the other in the Qatari dialect. The results show that the participants preferred MSA, which they found to be more eloquent, easy to follow, and described the actions in the scene more accurately.

Zengin Temırbek uulu et al. qualitatively examine the visually impaired and sighted participants’ comprehension of two versions of the same film, one with and one without supporting AD. This recent Turkish research aims to determine the extent to which AD contributes to visually impaired individuals’ comprehension of a film. When the movie is aided with AD, visually challenged participants are able to comprehend and describe the events similarly to sighted participants. These findings highlight the significance of AD assistance and its impact as a vital resource for transforming visual information into verbal information, which considerably enhances movie comprehension for the visually impaired. The study recommends AD producers to provide better support for the visually challenged.

In the context of the Persian language, Khoshsaligheh et al. focus on the quality of the Persian language AD by qualitatively analyzing three audio-described feature films produced in Iran in 2019. Intralingual AD is produced by an Iranian non-governmental organization called Sevina. The researchers’ goal is to determine whether the sampled AD transcripts provide a systematic approach based on Audio Description: Lifelong Access for the Blind project guidelines. The findings show a fairly consistent approach, even though there is room for improvement in future studies.

This study analyzes the AD of the Arabic series AlRawabi School for Girls. This might provide audio describers with further suggestions that help improve the quality of Arabic AD. In summary, the studies reviewed in this section discussed AD in several languages; however, there is limited discussion about this phenomenon in Arabic audio-visual products, a gap that this study attempts to fill.

Methodology

This section discusses the study method. The researchers qualitatively analyze the AD of “AlRawabi School for Girls” series according to six main categories. The chosen series ‘Madrast Al-Rawabi LilBanat’ is the second original Jordanian Netflix after Jinn. Jinn, which is the first Arabic supernatural drama, was premiered on June 2019 and was directed by Mir-Jean Bou Chaaya and Amin Matalqa. The story illustrates Jinn (literally meaning ghost) in the city of Petra (one of the Seven Wonders of the World), located in Jordan. Netflix is a well-known digital streaming service platform that provides optional AD services to its subscribers for many series and movies in different languages. The researchers watched all six episodes and transcribed the AD scripts manually. Then, the ADs were classified into six thematic categories, building upon the model of Salway. These categories are description of characters, description of actions, interpersonal interactions, description of settings, emotional states, and on-screen texts.

Why AlRawabi School for Girls?

AlRawabi School for Girls is an Arabic six-part TV drama mini-series that premiered on August 2021. It sheds light on social and cultural topics infrequently discussed through Arabic-language entertainment, focusing on the topic of bullying young women. It rates 7.4/10 on IMDb, a well-known online information database related to streaming audio-visual content. Also, the maturity rating for the series is +16. The main characters include a cast of six girls named: Mariam, Noaf, Layan, Dina, Rania, and Ruqayya.

The AlRawabi School for Girls series is written by two young female Jordanians, Tima Shomali and Shirin Kamal, and produced by Filmizion Productions (on behalf of Netflix). Tima Shomali is the founder of Filmizion Production and is also a director and comedy actress, while Shirin Kamal serves as the Creative Music Supervisor of the series. AlRawabi School for Girls is a controversial Jordanian series because it openly portrays topics that are not openly discussed. Some described the series as featuring “uncomfortable” content and projecting a “false image” of Jordanian society (see Misra). On the contrary, others have praised the show for portraying young teenage Arab girls.

The female-centric teen series crucially discusses hot topics in Arab societies, such as bullying, women’s rights, psychology, religion, revenge, and toxic relationships, to mention a few. Surprisingly, it is subtitled in 32 languages, including English, Spanish, Italian, French, German, and Turkish, and dubbed in more than nine languages. It is also available in 190 countries.

Data Collection and Corpus Compilation

A corpus of AD of AlRawabi School for Girls series was compiled to be further analyzed by the researchers. After watching the six-episode series on Netflix, each lasting about 45 min, the researchers wrote down the full audio-described version of the series manually on an Excel sheet. The AD is mainly in MSA, although the series is produced in Jordanian vernacular. Since the Netflix material is protected and is not subject to any free or open license, it is important to note that the researchers contacted the streaming platform and were informed that Netflix allows for the use of its subtitles for educational purposes, which include facilitating learning, promoting knowledge acquisition, and supporting educational goals within formal or informal educational settings and contexts.

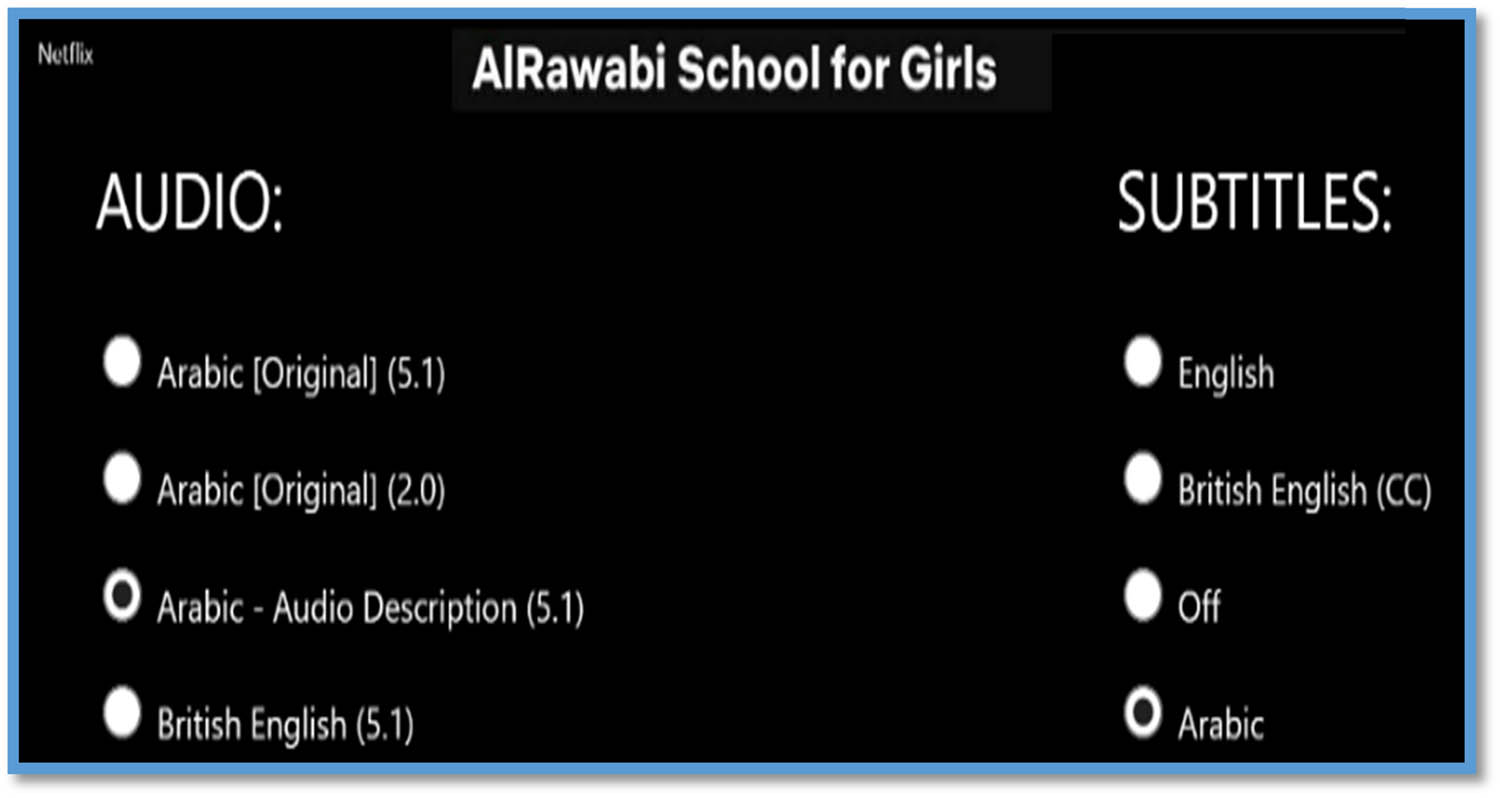

Figure 1 shows the available options for Netflix subscribers when watching AlRawabi School for Girls. These include audio and subtitles options. In the former, subscribers can select Arabic (original), i.e., in Jordanian Vernacular or AD. They can also watch a dubbed version in British English. The subtitled versions are intralingual (Arabic) and interlingual (including English).

Available audio and subtitles on Netflix for AlRawabi School for Girls.

Figure 2 shows an intralingual subtitling of the series, where the actress’s words appear at the bottom of the screen and read as “هلا، المدرسة صارت كابوسي” (Lit. the school is now my nightmare).

A screenshot from “ALRawabi School for Girls” series with Netflix Arabic subtitles.

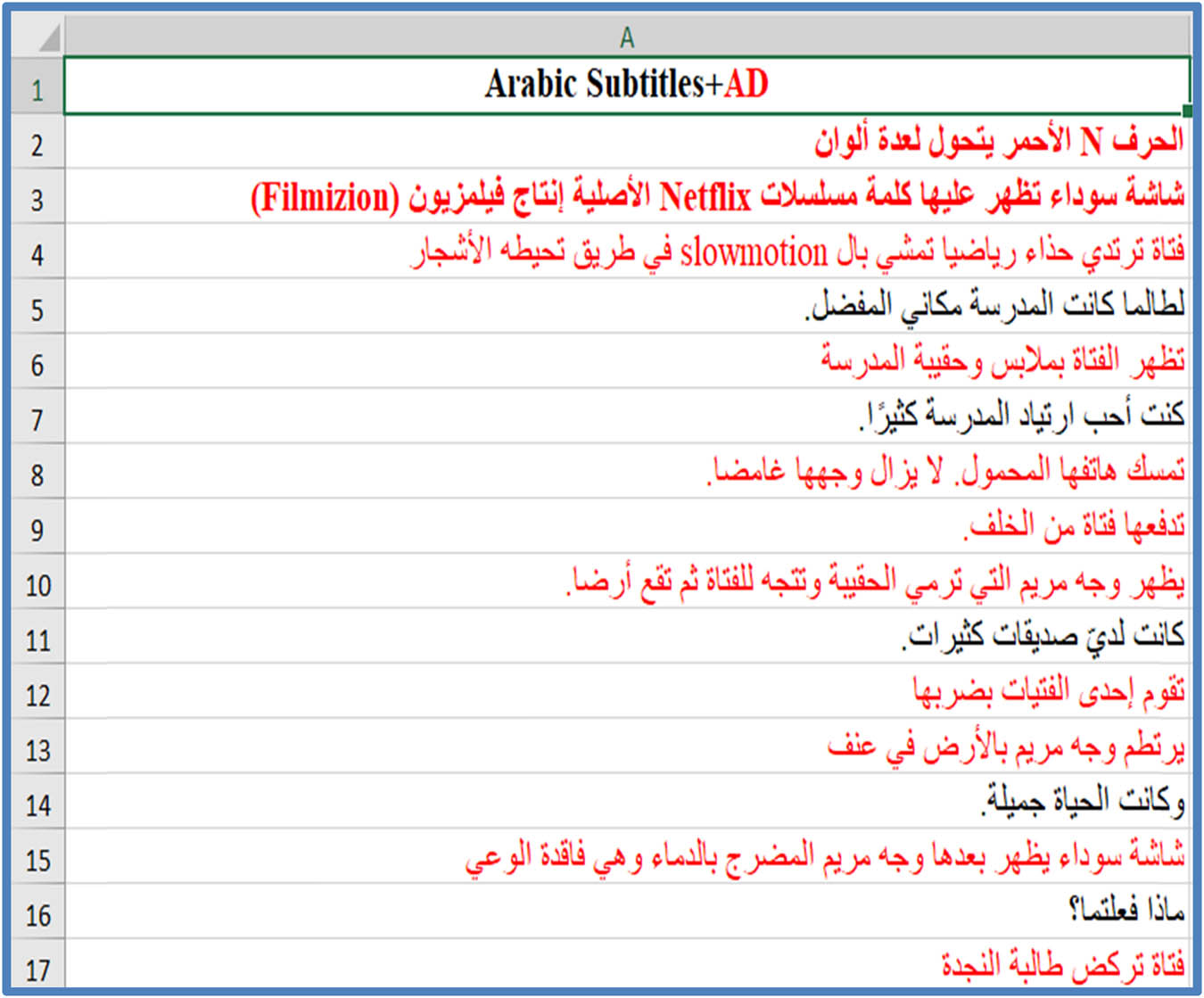

Figure 3 includes the MSA intralingual subtitles of AlRawabi School for Girls extracted from Netflix (the text in black). It also includes the AD (the text in red).

A screenshot of the MSA intralingual subtitles and AD of AlRawabi School for Girls.

Corpus Linguistics (CL)

There are different CL techniques. These include frequency, clusters, concordance, collocation, and keywords (Baker; McEnery and Wilson). In this study, two techniques are used: frequency and concordance. Frequency shows a list of all words in the corpus, and concordance investigates words in context. In this study, Wordsmith 6 (WS6) (Scott), a CL software package, is used to generate word lists and concordance analysis.

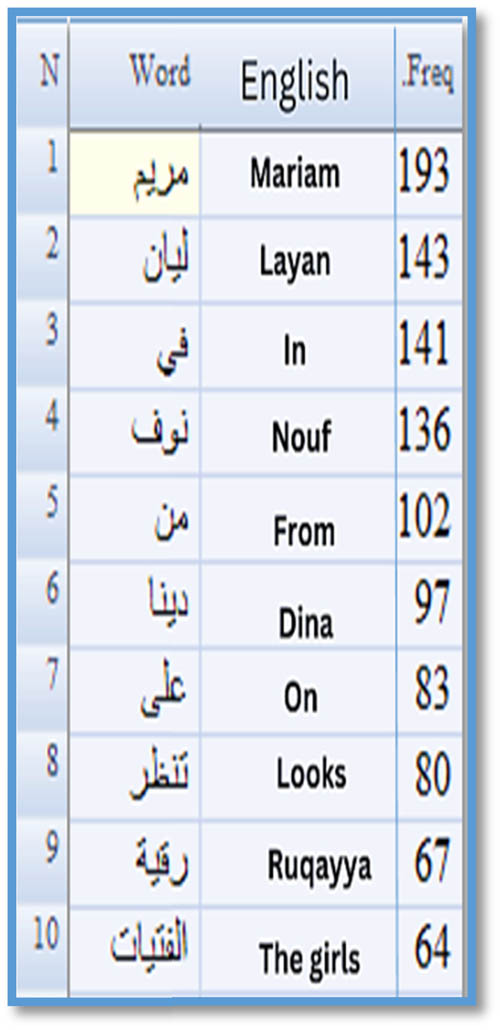

Frequency analysis enables researchers to identify the most frequent words in a corpus and compare the list with other frequent words in several multilingual and monolingual corpora (Haider). In this study, the researchers conduct frequency analysis and investigate the data accordingly. Figure 4 shows a screenshot of frequency analysis using WS6.

Screenshot of frequency analysis on WS6.

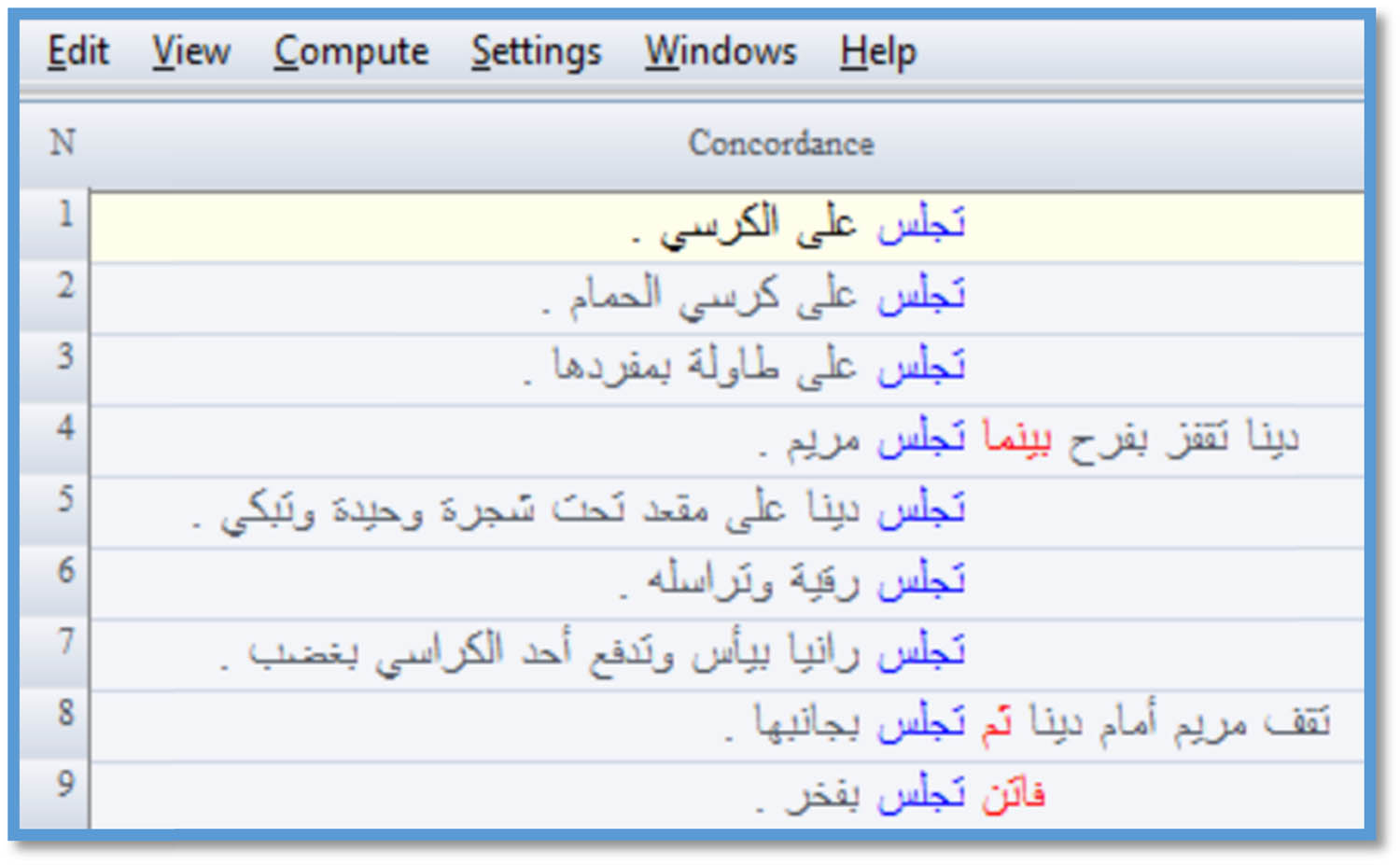

Concordance shows all the hits of a search term in context. In this article, the researchers generate concordance lines for some particular words and divide them into thematic categories. Figure 5 shows a screenshot of concordance analysis.

Screenshot of concordance on WS6.

Research Procedure

After selecting and watching the AlRawabi School for Girls Arabic series, the AD script from Netflix was transcribed by manually writing it down. After that, the original Netflix MSA intralingual subtitles of the series were extracted directly from Netflix. Subsequently, the collected data from all six episodes were converted into plain text files (.txt) to be processed and read by WS6 CL software package. After processing the data using WS6, the AD and MSA intralingual subtitles of the series were compared and contrasted. Later on, the Ads were classified thematically based on the type of information they covered. Finally, the AD parts that involve code-switching between Arabic and English were explored.

Analysis and Findings

This section is divided into three main parts, namely, a comparison between AD and the series’ original dialogue; an analysis of the most frequent words in the corpus; and a thematic categorization for the type of information covered in the AD.

Comparing AD to MSA Subtitle Corpora

Tokens, types, and type/token ratio (TTR) (Chotlos; Templin) are important, especially when comparing corpora. For example, AD and MSA intralingual subtitle corpora are illustrated in this study. These statistics reveal information about the features of the texts examined, whether the corpora are monolingual or multilingual.

The researchers used the wordlist tool in WS6 to generate corpus statistics for the six episodes as one unit and each episode separately. Table 1 shows the tokens, types, and TTR in the investigated AD corpus.

Size and statistics of AD corpus using WS6

| N | Text file | Tokens (running words) | Types (distinct words) | TTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Overall | 5,534 | 1,867 | 33.74 |

| 2 | Episode 1 .txt | 1,005 | 547 | 54.43 |

| 3 | Episode 2 .txt | 768 | 380 | 49.48 |

| 4 | Episode 3 .txt | 1,142 | 597 | 52.28 |

| 5 | Episode 4 .txt | 677 | 335 | 49.48 |

| 6 | Episode 5 .txt | 886 | 442 | 49.89 |

| 7 | Episode 6 .txt | 1,056 | 576 | 54.55 |

Token refers to the actual number of words in the corpus (running words), while type refers to the unique words in the corpus. Figure 1 shows that the second (768 words), fourth (677 words), and fifth (886 words) episodes include fewer words than the first, third, and sixth episodes with 1,005, 1,142, and 1,056 words, respectively. This might be because the important events contributing to the series’ plot occurred in these episodes, and this is why they are described more thoroughly to the target audience. This could also be attributed to the availability of portions, often referred to as “gaps” or “pauses,” between dialogues or scenes.

The Arabic language has several varieties, including Classical Arabic (CA), MSA, and Dialectal Arabic (DA) (Ferguson). MSA is the simplified form of CA and is considered the lingua franca of the Arab World (McCarus). Netflix provides MSA subtitles for most Arabic vernacular movies or series. The main reason behind using the corpus of the MSA subtitles of the series is to compare the frequencies of some words in the two versions, i.e., the AD and source script. Table 2 shows the size of the MSA subtitles for AlRawabi School for Girls. As the researchers stated before, the series is produced in Jordanian vernacular, but the researchers could not transcribe it due to time constraints, and this is why the intralingual MSA corpus is used.

Size and statistics of the MSA intralingual subtitles corpus using WS6

| N | Text file | Tokens (running words) | Types (distinct words) | TTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Overall | 15,431 | 4,947 | 32.06 |

| 2 | Episode 1 MSA .txt | 2,655 | 1,327 | 49.98 |

| 3 | Episode 2 MSA .txt | 2,757 | 1,390 | 50.42 |

| 4 | Episode 3 MSA .txt | 2,350 | 1,158 | 49.28 |

| 5 | Episode 4 MSA .txt | 2,645 | 1,293 | 48.88 |

| 6 | Episode 5 MSA .txt | 2,672 | 1,216 | 45.51 |

| 7 | Episode 6 MSA .txt | 2,352 | 1,184 | 50.34 |

Figure 5 shows that the actual size of the MSA intralingual subtitle corpus is 15,448 words, with 4,947 distinct words (types). The ratio of types to tokens is 32.06.

Table 3 summarizes the results of Tables 1 and 2.

Comparing the size of MSA intralingual subtitles with AD

| Statistics | MSA subtitles | AD |

|---|---|---|

| Tokens | 15,431 | 5,534 |

| Types | 4,947 | 1,867 |

| TTR | 32.06 | 33.74 |

Table 3 shows that the number of words in the subtitle corpus is larger than that of AD. This is expected because ADs are mainly added between dialogues or scenes. Such a variation is likely due to spatial and temporal constraints. AD phrases are inserted between the characters’ conversations, which is the silent part of the audio-visual scenes. This is why audio describers use phrases that deliver the message in the shortest possible way. The audio describers need to infer what the essential parts of a scene are and convey these to the blind or visually impaired audience.

Table 3 also shows that types are more common in the MSA intralingual subtitle corpus than they are in the AD corpus. The variety of the text’s vocabulary is more visible in the AD corpus (33.74) when compared to the MSA subtitles (32.06). This means that more content words are used in the AD version instead of the MSA corpus. The grammatical (function) words are used more in the MSA intralingual subtitles because there is enough space for the subtitlers to write complete sentences compared to the audio-describers. According to Al-Khalafat and Haider (136), “Type/token ratio indicates the variety of the text’s vocabulary; i.e., the highest the TTR, the more varied the text’s vocabulary.”

Frequency Analysis

The two main CL techniques used in this study are frequency and concordance. The researchers first used WS6 to generate a list of all words in the corpus with their frequencies. Table 4 shows the most frequent 20 words in the corpus.

The 20 most frequent words in the corpus

| No. | Arabic word | English transliteration | English translation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | مريم | mar̊yam | Mariam | 193 |

| 2 | ليان | līān | Layan | 143 |

| 3 | في | fī | In | 141 |

| 4 | نوف | nūf | Nouf | 136 |

| 5 | من | min̊ | From | 102 |

| 6 | دينا | dīna | Dina | 97 |

| 7 | على | ʿala | On | 83 |

| 8 | تنظر | tan̊ẓur | Looks | 80 |

| 9 | رقية | ruqīã | Ruqayya | 67 |

| 10 | الفتيات | ạl̊fatīãạt | The girls | 64 |

| 11 | المدرسة | ạl̊mad̊rasa | The school | 60 |

| 12 | رانيا | rānīā | Rania | 55 |

| 13 | عبير | ʿabīr | Abeer | 46 |

| 14 | بينما | baẙnamā | While | 45 |

| 15 | مس | mi ̊s | Miss | 44 |

| 16 | إلى | ại̹la | To | 42 |

| 17 | الحمام | ạl̊ḥamām | The bathroom | 38 |

| 18 | تقترب | taq̊tarib | Approaches | 37 |

| 19 | هاتفها | hātifahā | Her phone | 37 |

| 20 | تبتسم | tab̊tasim | Smiles | 29 |

As Table 4 shows, the most frequent words in the corpus include content words (personal names) such as مريم Mariam (mar̊yam) and ليان (līān) Layan and function words such as من (min̊) from and الى( ại̹la )to. This study focuses on content words, so an Arabic stop list that includes some words such as من from, الى to, and الذي/التي/الذين/اللواتي who is used to filter out function words. However, these words are sometimes distracting, especially when focusing on content words.

Similarly, to get accurate results and statistics, the researchers created a lemma list, which is a list of the headword with the derivatives, and used it to create a frequency list of the AD corpus under investigation, as shown in Table 5. Using the lemma list is important because Arabic is morphologically rich, as the same word may have different derivatives based on number (singular, dual, or plural), gender (feminine or masculine), and definiteness (indefinite or definite) (Haider). Additionally, prepositions and articles in Arabic are sometimes attached to words.

The most frequent lemmatized 30 words in the corpus

| N | Word | English translation | Freq. | Lemmas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | مريم | Mariam | 207 | [مريم[193] بمريم[2] لمريم[6] ومريم [6 |

| 2 | نوف | Nouf | 170 | [نوف[136] بنوف[2] لنوف[9] ونوف[23 |

| 3 | ليان | Layan | 167 | [ليان[143] لليان[4] وليان[20 |

| 4 | دينا | Dina | 116 | [دينا[97] لدينا[3] ودينا[16 |

| 5 | تنظر | Looks | 101 | [تنظر[80] تنظران[2] فتنظر[1] وتنظر[4] ينظر[7] ينظران[1] ينظرن[6 |

| 6 | الفتيات | The girls | 96 | [الفتيات[64] الفتاة[2] الفتاتان[1] فتاة[11] فتيات[10] والفتيات[7] وفتيات[1 |

| 7 | رانيا | Rania | 80 | [رانيا[55] برانيا[1] لرانيا[8] ورانيا[16 |

| 8 | رقية | Ruqayya | 79 | [رقية[67] برقية[1] لرقية[6] ورقية[5 |

| 9 | المدرسة | The school | 67 | [المدرسة[60] بالمدرسة[2] مدرسة[5 |

| 10 | مس | Teacher | 54 | [مس[44] لمس[1] ومس[9 |

| 11 | تقترب | Approaches | 50 | [تقترب[37] تقتربان[3] وتقترب[2] يقترب[8 |

| 12 | الحمام | The bathroom | 46 | [الحمام[38] حمام[8 |

| 13 | عبير | Abeer | 46 | |

| 14 | تبتسم | Smiles | 40 | [تبتسم[29] وتبتسم[8] ويبتسم[1] يبتسم[2 |

| 15 | تراقب | Observes | 37 | [تراقب[21] تراقبان[1] تراقبنها[1] تراقبه[1] تراقبهما[2] وتراقب[2] يراقب[1] تراقبها[8 |

| 16 | هاتفها | Her phone | 37 | |

| 17 | تخرج | Leaves | 34 | [تخرج[23] تخرجان[1] وتخرج[8] ويخرجان[1] يخرجان[1 |

| 18 | تدخل | Enters | 34 | [تدخل[27] تدخلان[1] وتدخل[3] يدخلان[2] يدخلون[1 |

| 19 | الباب | The door | 32 | [الباب[25] باب[7 |

| 20 | ليث | Laith | 31 | [ليث[21] بليث[4] لليث[1] وليث[5 |

| 21 | تتفقد | Checks | 27 | [تتفقد[22] تتفقدان[1] وتتفقد[2] يتفقد[2 |

| 22 | صورة | Picture | 27 | [صورة[19] الصور[3] الصورة[1] صور[4 |

| 23 | تتحرك | Moves | 26 | [تتحرك[16] تتحركان[1] وتتحرك[7] وتتحركان[1] يتحرك[1 |

| 24 | تجلس | Sits | 26 | [تجلس[21] تجلسان[2] وتجلس[3 |

| 25 | تضع | Puts | 26 | [تضع[22] وتضع[1] يضع[2] يضعان[1 |

| 26 | تمسك | Holds | 26 | [تمسك[19] وتمسك[2] يمسك[5 |

| 27 | رسالة | Message | 25 | |

| 28 | تشير | Points | 24 | [تشير[17] فتشير[2] وتشير[4] يشير[1 |

| 29 | تغادر | Leaves | 23 | [تغادر[10] تغادران[2] وتغادر[8] يغادر[2] يغادرون[1 |

| 30 | وسط | In between | 21 |

The researchers examined the frequency list and classified the most frequent words into thematic categories. As shown in Table 5, characters’ names were the most frequent in the corpus, with مريم (mar̊yam) Mariam being at the top of the list with 207 times. Table 5 also shows that some verbs were frequently used, such as تقترب (taq̊tarib) approaches (50 times), تبتسم (tab̊tasim) smiles (40 times), and تدخل (tadkhul) enters (34 times), to mention a few. The next section discusses the categorization of the main types of information covered in the AD of AlRawabi School for Girls series.

Thematic Categorization

In this section, the researchers analyze the thematic categories derived from the most frequent content words in the AD corpus. In this part, the researchers use the CL technique of concordance (KWIC), which shows the node word or the search term in context. Concordance investigates a particular linguistic item in its context by considering the surrounding words that might range from one word to the left or right of that item to the whole text if needed. Table 6 shows how the first scene of the series is AD.

First scene of AlRawabi School for Girls series

| No. | AD and the original script subtitles | English translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AD | الحرف ال N أحمر يتحول لعدة ألوان. | The red letter N transforms into different colors |

| 2 | AD | شاشة سوداء تظهر عليها كلمة مسلسلات الأصلية إنتاج فيلمزيون Netflix . | A black screen shows “Original Netflix Series” produced by Filmizion |

| 3 | AD | فتاة ترتدي حذاء رياضيا تمشي بال في طريق تحيطه الأشجار slow motion. | A girl wearing sports shoes walks in slow motion on a path surrounded by trees |

| 4 | Script | لطالما كانت المدرسة مكاني المفضل. | The school has always been my favorite place |

| 5 | AD | تظهر الفتاة بملابس وحقيبة المدرسة. | The girl shows up in the school’s uniform and bag |

| 6 | Script | كنت أحب ارتياد المدرسة كثيرًا. | I used to love attending school so much |

| 7 | AD | تمسك هاتفها المحمول. لا يزال وجهها غامضا. | She holds her phone. Her face remains mysterious |

| 8 | AD | تدفعها فتاة من الخلف. | A girl pushes her from behind |

| 9 | AD | يظهر وجه مريم التي ترمي الحقيبة وتتجه للفتاة ثم تقع أرضا. | Mariam’s face appears, throwing the bag and moving toward the girl before falling down |

| 10 | Script | كانت لديّ صديقات كثيرات. | I had many friends |

| 11 | AD | تقوم إحدى الفتيات بضربها. | One of the girls hit her |

| 12 | AD | يرتطم وجه مريم بالأرض في عنف. | Mariam’s face hit the floor violently |

| 13 | Script | وكانت الحياة جميلة. | And life was beautiful |

| 14 | AD | شاشة سوداء يظهر بعدها وجه مريم المضرج بالدماء وهي فاقدة الوعي. | A black screen is followed by Mariam’s bloodied face while being unconscious |

| 15 | Script | ماذا فعلتما؟ | What have you done? |

| 16 | AD | فتاة تركض طالبة النجدة. | A girl runs, asking for help |

| 17 | Script | لنذهب من هنا قبل أن يلمحنا أحد! | Let us leave before someone sees us! |

| 18 | Script | لكن ليس بعد اليوم. | But not anymore |

Table 6 shows the first scene of AlRawabi School for Girls, which is taken from the first episode entitled “School was my Happy Place.” There are 18 utterances in total, 11 delivered by the audio describer and the remaining 7 by the characters. In utterances 1 and 2, the audio describer concisely gives a detailed account of what is presented on the screen, even before the actual beginning of the series, where the Netflix logo is described. Such an outset can appear promising, as minor details are described from the very beginning. The number of utterances in the AD is higher than that of the script. This could be because the first scene, in specific, can create a good first impression for the visually impaired audience, who are the main target audience of AD. In the series, such detailed descriptions might also be challenging due to spatial and temporal constraints. Therefore, audio describers are always advised not to pay that much attention to the events that do not contribute much to the series plot. As for the dialogue, according to Netflix AD guidelines, sound effects, music, and intentional silence are necessary items and should be described.

Examining the frequency list of the AD corpus, six main thematic categories are found. These include description of characters, description of actions, interpersonal interactions, description of settings, emotional states, and on-screen texts. This categorization would be helpful for audio describers, AVT students, and trainers as it shows the type of information to be included in the AD. Table 7 shows the six main thematic categories, their sub-categories, and a short description of each theme.

Thematic categories of the most frequent words

| No. | Main thematic category | Sub-categories | Theme description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Description of characters | Names | Personal names such as Nouf, Mariam, Faten, and Laith |

| Titles | Titles and address forms such as principal, teacher, driver, Mrs., and Mr. | ||

| Appearances | Physical features such as skin color, clothing, and hair | ||

| 2 | Description of actions | Dynamic–stative | Characters’ movements and mental actions |

| 3 | Interpersonal interactions | — | Interaction between characters, such as hug, kick, dance, touch, and beat |

| 4 | Description of settings | Place–time | Describing location (adverbs of time and place) |

| 5 | Emotional states | — | Non-verbal gestures and feelings such as, gaze, look, watch, stare, and feel |

| 6 | On-screen texts | — | Reading the on-screen texts and messages |

The key information included in the ADs are names, locations, context, details, and descriptors. These aspects often answer the who, what, when, where, and how questions (Braun). The following subsections discuss in detail the categories outlined in Table 7.

Description of Characters

In AD, when characters appear on the screen, they are introduced with a moderately simple description of their names, titles, and appearance. The sub-category of characters’ names or proper nouns includes the most frequent words in the corpus. Regarding titles, some title words were frequent in the AD, such as المعلمة teacher, المديرة principal, and الطالبة student. Furthermore, the category of appearance includes several words related to hair and clothing.

The names of the main characters of AlRawabi School for Girls are the most frequent words in the AD corpus. However, the frequency of each character’s name differs according to their role in the series. In the section “Comparing AD to MSA Subtitle Corpora,” the researchers compared and contrasted the size of the AD corpus with that of the MSA intralingual subtitles. Since names are frequent in the AD corpus, the researchers examined whether they were also frequent in the MSA subtitle corpus, as shown in Table 8.

Frequency of characters’ names in the two corpora

| Character’s name | English translation | AD | MSA intralingual |

|---|---|---|---|

| مريم | Mariam | 207 | 121 |

| نوف | Nouf | 170 | 83 |

| ليان | Layan | 167 | 141 |

| دينا | Dina | 116 | 71 |

| رانيا | Rania | 80 | 49 |

| رقية | Ruqayya | 79 | 43 |

| عبير | Abeer | 46 | 34 |

| ليث | Laith | 31 | 19 |

| فاتن | Faten | 19 | 27 |

Table 8 shows that characters’ names were more frequent in the AD corpus than they are in the MSA subtitle corpus. For example, مريم Mariam was mentioned 207 times in the AD corpus and only 121 times in the MSA subtitle corpus. This means that referring to the characters’ names and what they are doing in the scenes is essential in AD. To ensure clarity, accessibility, and comprehension for people who rely on ADs, the names are repeated. Understanding the plot, context, and character interactions within a visual narrative depends heavily on proper nouns, such as names of people, locations, or significant objects. Repeating names or proper nouns helps the describer strengthen the link between the name and the matching visual aspect or character throughout the AD. Using the characters’ names, especially the main and relevant supporting characters, is fundamental when describing the plots in audio-visual products, such as movies and series. Table 9 includes a concordance analysis for the character مريم Mariam.

Concordance of ‘مريم’ Mariam

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | مريم تبكي بصمت. | Mariam is crying silently |

| 2 | مريم في غرفتها تعمل على الحاسوب الخاص بها. | Mariam is in her room working on her personal computer |

| 3 | مريم ودينا تقتربان. | Mariam and Dina are approaching each other |

| 4 | مريم تبكي في الحمام. | Mariam is crying in the bathroom |

| 5 | مريم ودينا تفتحان الباب. | Mariam and Dina are opening the door |

| 6 | مريم في سريرها تتفقد هاتفها. | Mariam is in her bed checking her phone |

| 7 | مريم تخفي وجهها. | Mariam is hiding her face |

| 8 | مريم تدخل إلى غرفتها مع نوف. | Mariam is entering her room with Nouf |

| 9 | مريم تنظر بدهشة واستغراب. | Mariam is looking with surprise and astonishment |

The main character, مريم Mariam, was mentioned 207 times in the AD version, which indicates the compelling need to mention the names of characters to let the target audience, i.e., blind and visually impaired, understand and link the series’ scenes with the events.

Addressing people with their titles is common and prevalent in the Arab World. In AD, when naming the characters for the first time, audio describers are advised to mention their titles to make the task of processing the information easier for the target audience. Table 10 shows some examples of the title ‘مس’ teacher.

Concordance of ‘مس’ teacher

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | مس جمانة تعطي طالبة ورقة. | Teacher Jumana is giving a student a paper |

| 2 | مس جمانة تصور. | Teacher Jumana is taking a photo |

| 3 | مس عبير تمسك بقلم بعصبية. | Teacher Abeer is holding a pen nervously |

| 4 | مس عبير في الصف تشرح. | Teacher Abeer is explaining in the classroom |

| 5 | مس عبير تركض. | Teacher Abeer is running |

| 6 | مس جمانة تجمع الفتيات. | Teacher Jumana is gathering the girls |

| 7 | مس جمانة تربت على كتف مريم. | Teacher Jumana is patting on Mariam’s shoulder |

| 8 | مس فاتن المديرة تنهض وتخرج. | Teacher Faten, the principal, stands up and gets out |

Since the main setting of the series is a school, it is expected to find several titles, especially when addressing teachers. The most frequent titles or address forms in the series are مس and استاذة teacher. Table 10 shows that the title مس teacher is used with different schoolteachers in the series (e.g., عبير Abeer and جمانة Jumana) and the headmistress (فاتن Faten).

Phrases related to appearance in the series are mainly about clothing and hair. According to Netflix’s newest guidelines, AD should prioritize an individual’s appearance to address the most significant physical features relevant to the plot. Table 11 includes some examples under this category and their English translation.

Concordance of ملابس clothes and شعر Hair

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | نوف تغير ملابسها. | Nouf is changing her clothes |

| 2 | تطالع ملابسها واكسسواراتها. | She is looking at her clothes and accessories |

| 3 | الثلاثي يرتدين ملابس عمال نظافة. | The trio are wearing janitors’ clothes |

| 4 | نوف تضع كحلا أسود وترتدي ملابس سوداء. | Nouf is wearing black eyeliner and wears black clothes |

| 5 | يعثر على ملابس أخته. | He found his sister’s clothes |

| 6 | مس عبير بملابس السباحة. | Teacher Abeer is wearing swimming clothes |

| 7 | تعطيهن ملابس النظافة وسط دهشة الفتيات. | She gives them the janitors’ clothes amid the girls’ awe |

| 8 | تشير رانيا ذات الشعر الأحمر لإحدى زميلاتها. | Rania, with the red hair, points to one of her colleagues |

| 9 | رانيا تسدل شعرها. | Rania lets down her hair |

| 10 | تخلع الحجاب وتفرد شعرها. | She takes off the hijab and lets down her hair |

Table 11 shows some examples related to clothes, where the characters are described to be wearing and changing clothes. The type of clothes is also referred to as in example 3 (janitors’ clothes) and example 6 (swimming clothes). Concerning hair, the color is sometimes mentioned, as in example 8 (red hair) or how it is styled (tied or down).

Description of Actions

When describing actions, not all elements need to be included every time due to temporal and spatial constraints. Audio describers need to be able to specify the most relevant parts of the story without negatively affecting the viewers’ experience or depriving them of fully understanding the plot. They should also avoid information overload, especially when details can be recognized from the dialogue or music. Different verbs are found in the frequency list. In this section, the researchers discuss the 56 most frequent action verbs used in the AD along with their derivatives, as shown in Table 12.

Most frequent action verbs in the AD corpus

| No. | Verb | English | Frequency | No. | Verb | English | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | تنظر | Looks | 95 | 29 | تمشي | Walks | 7 |

| 2 | تقترب | Approaches | 50 | 30 | تنزل | Gets down | 7 |

| 3 | تبتسم | Smiles | 40 | 31 | يظهر | Shows up | 7 |

| 4 | تراقب | Observes | 37 | 32 | تتابع | Pursues | 6 |

| 5 | تدخل | Enters | 34 | 33 | تتناول | Eats | 6 |

| 6 | تخرج | Leaves | 32 | 34 | تسير | Walks | 6 |

| 7 | تتفقد | Checks | 27 | 35 | تشاهد | Watches | 6 |

| 8 | تمسك | Holds | 26 | 36 | تصعد | Goes up | 6 |

| 9 | تجلس | Sits | 26 | 37 | تفكر | Thinks | 6 |

| 10 | تتحرك | Moves | 25 | 38 | تبتعد | Gets away | 5 |

| 11 | تضع | Puts | 25 | 39 | تبدأ | Starts | 5 |

| 12 | تشير | Points | 24 | 40 | تحاول | Tries | 5 |

| 13 | تغادر | Leaves | 23 | 41 | تدفعها | Pushes her | 5 |

| 14 | تبكي | Cries | 20 | 42 | ترحل | Leaves | 5 |

| 15 | تقف | Stands | 14 | 43 | تسترق | Eavesdrop | 5 |

| 16 | تقوم | Gets up | 13 | 44 | تعاود | Returns | 5 |

| 17 | تتنهد | Sighs | 15 | 45 | تقرأ | Reads | 5 |

| 18 | تغلق | Closes | 11 | 46 | تملأ | Fills | 5 |

| 19 | تفتح | Opens | 10 | 47 | تتفاجأ | Is surprised | 4 |

| 20 | تأخذ | Takes | 9 | 48 | تجمع | Collects | 4 |

| 21 | تتجه | Heads to | 9 | 49 | تراسل | Texts | 4 |

| 22 | تنهض | Gets up | 9 | 50 | تركض | Runs | 4 |

| 23 | تظهر | Shows up | 8 | 51 | تشعر | Feels | 4 |

| 24 | تعلو | Rises | 8 | 52 | تقرع | Rings | 4 |

| 25 | تتذكر | Remembers | 7 | 53 | تكتب | Writes | 4 |

| 26 | ترد | Responds | 7 | 54 | تلتفت | Turns around | 4 |

| 27 | تصل | Reaches | 7 | 55 | تلوح | Waves | 4 |

| 28 | تلتقط | Picks up | 7 | 56 | تنتبه | Pays attention | 4 |

As Table 12 shows, verbs like تنظر look, تقترب approach, and تبتسم smile are mentioned frequently in the AD. This category is a keystone in AD as it makes the viewers imagine what is happening on the screen. It can be observed that the describers used a relatively limited number of verbs and avoided using long words and phrases due to spatial and temporal constraints. In addition, it could be argued that including action verbs in the AD significantly enhances the series plot.

The verbs in this category are divided into dynamic or stative verbs. Dynamic verbs are those that show physical actions and indicate continued or progressive action. Stative verbs express a state and are related to senses, emotions, and thoughts. Table 13 shows two dynamic verbs, namely تجلس sit and تبكي cry, and one stative verb, namely تفكر think.

Concordance of the verbs تجلس sit, تبكي cry, and تفكر think

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | تجلس رانيا بيأس. | Rania is sitting desperately |

| 2 | فاتن تجلس بفخر. | Faten is sitting proudly |

| 3 | تجلس رقية وتراسله. | Ruqayya is sitting and texting him |

| 4 | نوف تجلس صامتة. | Nouf is sitting silently |

| 5 | دينا تبكي والفتيات يحطن بها. | Dina is crying while the girls surround her |

| 6 | تبكي مريم بأسى. | Mariam is crying with sorrow |

| 7 | مريم تبكي في الحمام. | Mariam is crying in the bathroom |

| 8 | مريم تبكي والجروح تملأ وجهها. | Mariam is crying, with wounds filling her face |

| 9 | نوف ممسكة هاتفها وهي تفكر. | Nouf is holding her phone while thinking |

| 10 | نوف تفكر. | Nouf is thinking |

| 11 | تأخذ نوف نفسا عميقا وهي تفكر. | Nouf is taking a deep breath while thinking |

| 12 | تنظر إلى الشاشة وهي تفكر | She is looking on screen while thinking |

The verbs تجلس sit, تبكيcry, and تفكرthink are among the most frequently used words in the investigated series. Four examples of each verb are shown in Table 13. These verbs are also described in such a way to show place, time, manner, and degree. For example, the adverbs بيأس desperately, بفخرproudly, and صامتة silently are used to describe different ways of sitting. Similarly, crying is described in an accurate way to deliver the feelings of the one crying and make the visually impaired audience feel the emotions and have a more immersive experience of what is shown in the scenes.

Interpersonal Interactions

This category includes words that describe the characters’ interpersonal interactions. In other words, any interaction between two or more characters is included under this category, as shown in Table 14.

Concordance of رقص dancing

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | الفتيات يرقصن في الحافلة. | The girls are dancing in the bus |

| 2 | فتيات وشبان يرقصون. | Girls and boys are dancing |

| 3 | رانيا وأحمد وليان وليث يرقصون. | Rania, Ahmad, Layan, and Laith are dancing |

| 4 | ليث يرقص مع ليان. | Laith is dancing with Layan |

| 5 | أحمد يرقص مع رانيا ويبتسم لنوف. | Ahmad is dancing with Rania and smiles at Nouf |

| 6 | الشبان والفتيات يرقصن بجانب بركة السباحة. | The boys and girls are dancing near the swimming pool |

The verb رقصdance shows the interaction between people. For example, الفتيات girls are the involved parties in example 1, شبانboys in example 2, رانيا Rania, أحمد Ahmad, ليان Layan, and ليث Laith in example 3, ليث Laith and ليان Layan in example 4, أحمد Ahmad and رانيا Rania in example 5, and several boys and girls without specifying names in example 6. In the context of AD, competent describers should learn how to re-see the world around them and truly notice what should be perceived in the eyes of the audience with vision impairment. They should also express the relevant aspects of images with precise and imaginative language and vocal techniques that render the visual–verbal (Snyder).

Description of Setting

Setting is a key aspect of any plot. As per Netflix’s AD policy, descriptions should include location, time, as well as weather conditions when relevant to the scene or plot. Table 15 includes some examples of place and time extracted from the AD corpus.

Concordance of place ( عمان Amman) and time (صباحاmorning, عصراafternoon, ليلاnight)

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | الحافلة تسير في شوارع عمان صباحا . | The bus is moving in Amman’s streets in the morning |

| 2 | عمان صباحا. | Amman in the morning |

| 3 | سماء مدينة عمان ليلا. | Amman’s sky at night |

| 4 | عمان فجرا. | Amman at dawn |

| 5 | عمان عصرا. | Amman in the afternoon |

| 6 | عمان ليلا. | Amman at night |

| 7 | صورة من الأعلى لجسر في عمان صباحا. | A photo from above of a bridge in Amman in the morning |

| 8 | شوارع عمان ليلا. | Amman’s streets at night |

| 9 | صورة من الأعلى لجسر في عمان صباحا. | A picture from above of a bridge in Amman in the morning |

| 10 | حافلة المدرسة وبها الطالبات صباحا. | The school’s bus with the students inside in the morning |

Table 15 shows that the city where the series is shot, namely عمانAmman, and the time (صباحا morning, عصرا afternoon, and ليلا night) were frequently referred to in the AD. Example 1 shows a concise description of settings. It allows the blind and visually impaired audience to generate imaginative views of the scenes displayed on the screen. Additionally, Netflix’s latest AD guideline assures that the visual elements, such as the naming of locations, should remain consistent within the description across all episodes.

Emotional States

Emotional reactions or states, which are essential parts of non-verbal communication, are discussed in this section. Multiple examples of the word علامات signs were spotted, followed by emotional states such as الانزعاج discomfort, الغضب anger, الخجل shyness, and الضيق distress. Table 16 shows the characters’ names accompanied by their emotional states/reactions.

Concordance of علامات signs

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | علامات الانزعاج تعلو وجه مريم. | Mariam’s face shows signs of discomfort |

| 2 | فاتن وعلى وجهها علامات الغضب. | Faten’s face shows signs of anger |

| 3 | تعلو علامات الخجل وجه يزن. | Yazan’s face shows signs of shyness |

| 4 | علامات الضيق تعلو وجهها. | Her face shows signs of distress |

Facial expressions may tell a lot about the person’s mood, such as happiness, surprise, contempt, sadness, fear, disgust, and anger. As discussed earlier, emotional states should be reflected in the AD. They are amongst the most sensitive yet compulsory parts that need to be added and clarified so that the target audiences, the B/VIP, can feel and interact with what is happening in the scenes.

On-Screen Texts

This category covers reading the different types of texts that appear on the screen, including messages, letters, and book titles, to mention a few. The AD in this group is delivered in Jordanian vernacular rather than MSA, mainly because the series is produced in the Jordanian dialect. The researchers found references to 13 texts that were read verbatim (Table 17).

On-screen texts for رسالة message occurrences

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD | English translation |

| 1 | رسالة تصل للفتيات جميعهن بنفس الوقت. | All the girls receive a message at the same time |

| 2 | مريم تتفقد هاتفها وتقرأ رسالة. | Mariam checks her phone and reads a message |

| 3 | رسالة على الشاشة. | A message is on the screen |

| 4 | رسالة من مريم. | A message from Mariam |

| 5 | رسالة على هاتف ليان من ليث. | A message from Laith to Layan |

| 6 | تصلها رسالة نصية هاتفية بالانجليزية. | She receives a message on her phone in English |

Table 17 includes six examples of the word message. The text messages that characters send via different social media websites or mobile phones, for instance, are revealed verbally to the target audience to deliver the message and understand the full scene without missing any essential parts. The inclusion of on-screen texts is a part of the accessibility service that Netflix and some other streaming platforms insert for the visually impaired.

Code-Switching

Code-switching is defined as the practice of altering between two or more languages or varieties of language (Nilep). Similarly, code-mixing refers to “all cases where lexical items and grammatical features from two languages appear in one sentence” (Muysken 1). In this study, the researchers spotted seven examples of code-switching in the AD version and many others in the original dialogue, as shown in Table 18.

Code-switching occurrences in AlRawabi School for Girls

| Concordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | AD with code-switching | English translation |

| 1 | slow motion فتاة تمشي بال | A girl is walking in slow motion |

| 2 | brave تمزق صورة الفتاة المكتوب عليها | She tears the photograph of the girl, upon which the word brave is written |

| 3 | mixer للصوت فتاة على مسرح صغير أمام. | A girl is in a small theater in front of an audio mixer |

| 4 | الخاص بها باهتمام iPad مريم تتف قد ال. | Mariam checks her iPad attentively |

| 5 | .tablet مريم ونوف تراقبان ال | Mariam and Nouf are watching the tablet |

| 6 | .على عينيها mask تظهر ليان ب | Layan shows up with a mask on her eyes |

| 7 | لها selfie تلتقط صورة. | She takes a selfie |

Table 18 shows seven examples of code-switching. Jordan is among the countries that use English frequently because it is taught in schools and universities. Some English loans are frequently used in Arabic conversation instead of their Arabic equivalents, such as iPad, tablet, and mask. This phenomenon is more common among formally educated people, such as academics, as they have the linguistic proficiency and sociolinguistic awareness necessary to move smoothly between these two languages. Most of the English words used in the AD are familiar to the receivers, and some of them, such as mobile, iPad, tablet, mask, and selfie, are sometimes used even more frequently than their Arabic counterparts.

It is crucial to remember that code-mixing, code-switching, and code-shifting are all common in bilingual and multilingual cultures, so when speakers employ two or more languages in their communication, these linguistic phenomena take place. Such phenomena should not be interpreted as a lack of linguistic ability or aptitude, though. They may occur when speakers include phrases or words from one language into their speech in another language, as in examples 1, 2, and 3. Another strategy is using loanwords, where speakers may utilize loanwords from English, as in examples 4, 5, 6, and 7. Code-switching may occur in the middle of a sentence, where speakers start with Arabic, then switch to English, and then use Arabic again, as examples 4, 6, and 7 show.

These phenomena may also occur when speakers use different Arabic varieties in their communication. Arabic has many dialects spoken across different regions and countries. For instance, some of the major Arabic varieties, including MSA, are Gulf Arabic, Levantine Arabic, Egyptian Arabic, Maghrebi Arabic, and Sudanese Arabic. In the investigated corpus, the audio describer mainly chose to use MSA and sometimes Jordanian vernacular. Again, they are used by speakers to accommodate different linguistic situations and to express themselves more effectively.

The use of code-switching in the AD of this series would also be helpful in creating a similar context to that of the original script, as the characters in the series are students in an international private school and belong to high social classes, so they maintain the use of English all the time.

Conclusion

AVT attempts to make video and media accessibility easier. As technology advances, video accessibility will become more important in terms of society’s entertainment needs. AD is crucial for people with visual impairment to understand the visual content of audio-visual products. The benefits of AD are not limited to this group, though. Other users also find AD helpful for learning new languages and remembering content.

This study identified the types of information covered in the AD of a Netflix series produced in Arabic following a corpus-assisted approach. It classified the main information presented in the AD of AlRawabi School for Girls series into six main thematic categories by applying the CL techniques of frequency and concordance (KWIC). Globally, AD is increasingly researched and implemented nowadays, and it has started having a noticeable space in the field of AVT. However, research focusing on AD in the Arabic context is scarce, so it is advisable to investigate other audio-visual products as a means of support for Arab blind and visually impaired audiences.

This study is limited in scope since it analyzes and examines only one series. Although this can be viewed as a good step, research on larger corpora in others could be compiled. This piece of research is corpus-assisted and addresses an issue that helps a group of people with special needs, i.e., blind and visually impaired, by introducing a new corpus that will be available upon request. However, the compiled corpus is limited to only the dialect used in the audio material, i.e., Jordanian vernacular. Other researchers might consider examining other materials that are produced in MSA or other vernaculars.

As this study focused on the covered information in the AD corpus, other researchers may investigate the quality of AD from a technical point of view. It has focused on AD in an Arabic series that aims offering entertainment for the visually impaired community, including the blind and people with low vision. Other researchers could conduct studies on other audio-visual materials, such as documentaries and football matches.

This study investigated the AD of an Arab series in Arabic. Other researchers may examine how Arabic AD is used in dubbed movies and series that are originally produced in languages other than Arabic. By doing so, researchers could further expand their analysis of the cultural dimensions in AD in terms of adaptation to the Arabic public, mitigation of sensible scenes, etc. It examined the differences between the original version of the Jordanian Netflix drama series and the version with AD in terms of the included information. Future researchers may transcribe the dialogues, not just the AD, as this will make it possible to observe the communicative effectiveness of the AD more consistently. From a sociolinguistic point of view, comparing the AD with the original Jordanian dialogues, i.e., not with the subtitles, which are adapted to MSA, would be useful.

This study used one CL software package, namely WS6, and two techniques, namely frequency and concordance, in processing the AD corpus. Future researchers can use different tools such as SketchEngine or techniques such as clusters, collocation, and keywords as this may reveal new findings and help in achieving a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. They could also compile a word list for English–Arabic AD glossaries or audio-visual projects that would help audio describers identify the most frequent terms in the AVT mode.

This article identified the basic information covered in AD and thus could provide a practical guide for prospective audio describers. It could also be helpful for translators, AVT students, and trainers, as well as lexicographers.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Works Cited

Al-Abbas, Linda S. and Ahmad S Haider. “Using Modern Standard Arabic in Subtitling Egyptian Comedy Movies for the Deaf/Hard of Hearing.” Cogent Arts and Humanities, vol. 8, no. 1, 2021, p. 1993597. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2021.1993597.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Abbas, Linda S, et al. “A Quantitative Analysis of the Reactions of Viewers with Hearing Impairment to the Intralingual Subtitling of Egyptian Movies.” Heliyon, 2022, p. e08728. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08728.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Khalafat, Leen and Ahmad S Haider. “A Corpus-Assisted Translation Study of Strategies Used in Rendering Culture-Bound Expressions in the Speeches of King Abdullah Ii.” Theory and Practice in Language Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2022, pp. 130–142.10.17507/tpls.1201.16Search in Google Scholar

Al-Zgoul, Omair and Saleh Al-Salman. “Fansubbers’ Subtitling Strategies of Swear Words from English into Arabic in the Bad Boys Movies.” Open Cultural Studies, vol. 6, no. 1, 2022, pp. 199–217. doi: 10.1515/culture-2022-0156.Search in Google Scholar

Aldualimi, Mohammad and Zakaryia Almahasees. “A Quantitative Analysis of the Reactions of Viewers to the Subtitling the Arabic Version of Ar-Risalah’s Movie” the Message” in English.” Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, vol. 57, no. 6, 2022, pp. 1053–1063. doi: 10.35741/issn.0258-2724.57.6.91.Search in Google Scholar

Alnatsheh, Areej Tariq. “A Contrastive Study of Two Linguistic Varieties of Audio Description: Msa Vs. Qatari Dialect.” Masters Thesis, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

Arma, Saveria. “The Language of Filmic Audio Description: A Corpus-Based Analysis of Adjectives.” Doctoral Dissertation, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Paul. Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis. Continuum, 2006.10.5040/9781350933996Search in Google Scholar

Braun, Sabine. “Audio Description from a Discourse Perspective: A Socially Relevant Framework for Research and Training.” Linguistica Antverpiensia, vol. 6, 2007, pp. 357–369.10.52034/lanstts.v6i.197Search in Google Scholar

Chotlos, John W. “Studies in Language Behavior: Iv. A Statistical and Comparative Analysis of Individual Written Language Samples [Monograph].” Psychological Monographs, vol. 56, no. 2, 1944, pp. 75–111.10.1037/h0093511Search in Google Scholar

Debbas, Manar and Ahmad S Haider. “Overcoming Cultural Constraints in Translating English Series: A Case Study of Subtitling Family Guy into Arabic.” 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature®, vol. 26, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–17.10.17576/3L-2020-2601-01Search in Google Scholar

Díaz-Cintas, Jorge and Pilar Orero. “Voiceover and Dubbing.” Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Yves Gambier, vol. 1, 2010, pp. 441–445.10.1075/hts.1.voi1Search in Google Scholar

Díaz-Cintas, Jorge and Aline Remael. Audio-visual Translation: Subtitling. Routledge, 2014.10.4324/9781315759678Search in Google Scholar

Fels, Deborah I, et al. “A Comparison of Alternative Narrative Approaches to Video Description for Animated Comedy.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, vol. 100, no. 5, 2006, pp. 295–305.10.1177/0145482X0610000507Search in Google Scholar

Ferguson, Charles A. “Diglossia.” word, vol. 15, no. 2, 1959, pp. 325–340.10.1080/00437956.1959.11659702Search in Google Scholar

Fryer, Louise. An Introduction to Audio Description: A Practical Guide. Routledge, 2016.10.4324/9781315707228Search in Google Scholar

Haider, Ahmad S. “A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Analysis of the Arab Uprisings: Evidence from the Libyan Case.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Canterbury, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

Haider, Ahmad S. “Using Corpus Linguistic Techniques in (Critical) Discourse Studies Reduces but Does Not Remove Bias: Evidence from an Arabic Corpus About Refugees.” Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, vol. 55, no. 1, 2019, pp. 89–133. doi: 10.1515/psicl-2019-0004.Search in Google Scholar

Haider, Ahmad S and Faurah Alrousan. “Dubbing Television Advertisements across Cultures and Languages: A Case Study of English and Arabic.” Language Value, vol. 15, no. 2, 2022, pp. 54–80.10.6035/languagev.6922Search in Google Scholar

Haider, Ahmad S and Riyad F Hussein. “Modern Standard Arabic as a Means of Euphemism: A Case Study of the Msa Intralingual Subtitling of Jinn Series.” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, Online First, 2022, pp. 1–16, doi: 10.1080/17475759.2022.2106289.Search in Google Scholar

Haider, Ahmad S, et al. “Subtitling Taboo Expressions from a Conservative to a More Liberal Culture: The Case of the Arab Tv Series Jinn.” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, vol. 1, no. aop, 2023, pp. 1–23.10.1163/18739865-tat00006Search in Google Scholar

Hättich, Achim and Martina Schweizer. “I Hear What You See: Effects of Audio Description Used in a Cinema on Immersion and Enjoyment in Blind and Visually Impaired People.” British Journal of Visual Impairment, vol. 38, no. 3, 2020, pp. 284–298.10.1177/0264619620911429Search in Google Scholar

Hayes, Lydia. “Netflix Disrupting Dubbing: English Dubs and British Accents.” Journal of Audio-visual Translation, vol. 4, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1–26. doi: 10.47476/jat.v4i1.2021.148.Search in Google Scholar

Hyks, Veronika. “Audio Description and Translation. Two Related but Different Skills.” Translating Today, vol. 4, no. July, 2005, pp. 6–8.Search in Google Scholar

Jakobson, Roman. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” On Linguistic Aspects of Translation, edited by Achilles Fang and Reuben Arthur Brower, Harvard University Press, 2013, pp. 232–239.Search in Google Scholar

Karantzi, Ismini. “‘Feeling’ the Audio Description: A Reception Perspective.” Bridge: Trends and Traditions in Translation and Interpreting Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2020, pp. 39–56.Search in Google Scholar

Khoshsaligheh, Masood, et al. “Persian Audio Description Quality of Feature Films in Iran: The Case of Sevina.” International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, vol. 10, no. 3, 2022, pp. 58–72. doi: 10.22034/ijscl.2022.552176.2618.Search in Google Scholar

Kleege, Georgina and Scott Wallin. “Audio Description as a Pedagogical Tool.” Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 2, 2015, pp. 1–11.10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4622Search in Google Scholar

Mazur, Iwona. “Audio Description: Concepts, Theories and Research Approaches.” The Palgrave Handbook of Audio-visual Translation and Media Accessibility, edited by Łukasz Bogucki and Mikołaj Deckert, Springer, 2020, p. 228.10.1007/978-3-030-42105-2_12Search in Google Scholar

McCarus, Ernest N. “The Study of Arabic in the United States: A History of Its Development.” Al-’Arabiyya, 1987, pp. 13–27.Search in Google Scholar

McEnery, Tony and Andrew Wilson. Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh University Press, 2001. vol. Book, Whole.Search in Google Scholar

Misra, Shubhangi. “Netflix’s ‘Alrawabi: School for Girls’ Sparks Row in Jordan for ‘Uncomfortable & Bold’ Content.” The Print, 2021. https://theprint.in/world/netflixs-alrawabi-school-for-girls-sparks-row-in-jordan-for-uncomfortable-bold-content/726790/https://theprint.in/world/netflixs-alrawabi-school-for-girls-sparks-row-in-jordan-for-uncomfortable-bold-content/726790/.Search in Google Scholar

Muysken, Pieter. Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing. Cambridge University Press, 2000.Search in Google Scholar

Newmark, Peter. A Textbook of Translation. Prentice-Hall International, 1987.Search in Google Scholar

Nilep, Chad. “‘Code Switching’ in Sociocultural Linguistics.” Colorado Research in Linguistics, vol. 19, 2006, pp. 1–22, doi: 10.25810/hnq4-jv62.Search in Google Scholar

Piety, Philip J. “The Language System of Audio Description: An Investigation as a Discursive Process.” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, vol. 98, no. 8, 2004, pp. 453–469.10.1177/0145482X0409800802Search in Google Scholar

Salway, Andrew. “A Corpus-Based Analysis of Audio Description.” Media for All: Subtitling for the Deaf, Audio Description, and Sign Language, edited by Jorge Díaz-Cintas et al., Brill, 2007, pp. 151–174.10.1163/9789401209564_012Search in Google Scholar

Samha, Fatima, et al. “Address Forms in Egyptian Vernacular and Their English Equivalence: A Translation-Oriented Study.” Ampersand, 2023, p. 100117, doi: 10.1016/j.amper.2023.100117.Search in Google Scholar

Schmeidler, Emilie and Corinne Kirchner. “Adding Audio Description: Does It Make a Difference?” Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, vol. 95, no. 4, 2001, pp. 197–212. doi: 10.1177/0145482x0109500402.Search in Google Scholar

Scott, Mike. “Wordsmith Tools Version 6.” Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software, vol. 122, Lexical Analysis Software, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Silwadi, Joumana and Zakaryia Almahasees. “A Quantitative Analysis of the Viewers’reactions to the Subtitling and Dubbing of the Animated Movies, Cars, into Arabic.” Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, vol. 57, no. 6, 2022, pp. 965–973.10.35741/issn.0258-2724.57.6.82Search in Google Scholar

Snyder, Joel. “Audio Description: The Visual Made Verbal.” The Didactics of Audio-visual Translation, edited by Jorge Díaz-Cintas, vol. 4, John Benjamins Publishing, 2005, pp. 15–17.Search in Google Scholar

Templin, Mildred C. Certain Language Skills in Children; Their Development and Interrelationships. University of Minnesota Press, 1957.10.5749/j.ctttv2stSearch in Google Scholar

Torop, Peeter. “Intersemiosis and Intersemiotic Translation.” Translation Translation, edited by Susan Petrilli, Brill, 2003, pp. 271–282.10.1163/9789004490093_016Search in Google Scholar

UtRay, Francisco, et al. “The Present and Future of Audio Description and Subtitling for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Spain.” Meta: journal des traducteurs/Meta: Translators’ Journal, vol. 54, no. 2, 2009, pp. 248–263.10.7202/037679arSearch in Google Scholar

Vermeulen, Anna and Ana Ibáñez Moreno. “Audio Description as a Tool to Enhance Intercultural Competence.” Transcultural Competence in Translation Pedagogy, vol. 12, Lit Verlag, 2017, pp. 133–156.Search in Google Scholar

Walczak, Agnieszka. “Measuring Immersion in Audio Description with Polish Blind and Visually Impaired Audiences.” Rivista Internazionale di Tecnica della Traduzione/International Journal of Translation, vol. 19, 2017, pp. 33–48.Search in Google Scholar

Zengin Temırbek uulu, Zeynep, et al. “The Effect of Audio Description on Film Comprehension of Individuals with Visual Impairment: A Case Study in Turkey.” British Journal of Visual Impairment, vol. 41, no. 1, 2021, pp. 130–142. doi: 10.1177/02646196211020058.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement