Abstract

National cuisine represents an important part of our identity. Being able to cook or eat familiar foods when living abroad becomes nearly as important as being able to use one’s mother tongue. This article discusses the phenomenon of Odessan cuisine both in Odessa and in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, a Russian-speaking enclave where more than 10,000 ex-Soviet citizens, many of whom were Odessans. The aim of the study is to explore the migration of the Odessan culinary tradition, the gastropoetic aspect of Odessan food narration and the embodiment of the myth of Odessa in food discourse. The study analyses the websites, social media, the menus of two restaurants labelling themselves as Odessan, and the clients’ comments related to said restaurants. The gastropoetic aspect of Odessan culinary tradition is presented through examples from the literary works of Odessan authors.

Introduction

Odessa, the third biggest city in Ukraine, and an important port on the Black Sea, came to the world’s attention following the breakout of the war in Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Many international news outlets were reporting from Odessa, and one could see images of the Odessa Opera House, the port, and the streets daily, while to that moment, apart from the post-Soviet cultural realm, Odessa as a place and as a cultural concept was rather absent in the public discourse. Since 2008, writing my master’s thesis and working on my dissertation on Odessa language, I nearly always had to clarify what and where Odessa was. Now, there has been a dramatic change, most people immediately know where to place Odessa. But there is still little knowledge about its unique history, its linguistic landscape, and its multicultural traditions. In this study, I aim to approach the argument of Odessan culture and language through its culinary traditions, which reflect the essence of “being Odessan.” I will also observe and analyse how these traditions are maintained and perceived by Odessan immigrants outside of Odessa and what is the role of food in immigration, a topic particularly relevant considering the many current and potential refugees of war from Ukraine.

One of my earliest childhood memories is related to Odessa and food. I vividly remember the monologue “I saw some crayfish…” (Zhvanetsky) written by one of the most renowned Odessan writers and satirists, Mihail Zhvanetsky, and performed by his compatriot Roman Kartsev. In this monologue, Kartsev’s character vividly describes the crayfish he came by the previous day, telling the audience that the crayfish was very big, but expensive; it costs five roubles. And the next day he came by some crayfish, which only cost three roubles, but was very small. The monologue goes on and on, comparing the crayfish from yesterday and today. I was fascinated by the images this simple, yet witty story managed to create. Of course, I had never eaten crayfish and I imagined this exotic scene at a market in Odessa, where one could find these creatures, “These for just three rubles, but small, but today… And those for five, yesterday…but big… but yesterday […].”[1] Growing up, I finally got the chance to taste these legendary crustaceans, but the fascination with Odessa and its food culture remained.

To approach the argument of the Odessan cuisine, it is necessary to address the cultural context in which it has developed. Since its foundation in 1794, Odessa has been populated by several nationalities: Russians, Jews, Ukrainians, Polish, Greek, and many others. Especially before WWII, the Jews had a particular influence on the culture and the language of the city, as they amounted to more than 30% of the entire population, and Odessa has often been considered a “Jewish city” (Grenoble and Kantarovich). The myth of (Old) Odessa and its multiethnic and multicultural population, its infamous low life, its wit, and humour, have been vastly described, for example, in works by Herlihy; Richardson; Tanny; Zipperstein. Its language, a Russian-based contact variant, with important morphosyntactic influences from Yiddish and Ukrainian, and lexical borrowings from other languages (Grenoble and Kantarovich), has been addressed, among others by Grenoble; Mechkovskaya; Stepanov. In my previous works, I have analysed the myth as it has lived on through films, series, and humorous television programs in a Russian-speaking context (Kabanen, “Odesskiy yazyk – bol'she mifa ili real’nosti?”; Kabanen, “Odessan Courtyard as a Symbol of Humor and Nostalgia on Russian Television”).

In recent years, since Zelinsky’s work, the discourse in the field of gastronomy has evolved, and food has become a fashionable topic for discussion, both in academia (Montanari; Counihan and Van Esterik; Laudan; García et al.) and outside of it. If we look at social media, television, and even personal communication, we notice that food is everywhere. There are countless cooking blogs, shows, channels, magazines, and pictures of food. Many of us cede to the temptation of taking a photo of a particularly appealing, or, vice versa, a particularly displeasing dish, and sharing it on social media.

Odessan cuisine, with its multicultural influences, colourful history, and witty stories and anecdotes (e.g. Zhvanetsky’s sketches) linked to it, has captured the interest of the media and the internet users. Television shows have been dedicated to Odessan food, such as Odessa Gotovit Obed (Odessa Is Cooking Lunch), produced by local Odessan TV channels first in the 1990s and then revived in 2015, and Odessa Delayet Bazar (Odessa Goes Shopping), which is still in production. A popular travel and cooking show Poyedem, Poyedim (Let’s Travel and Savour, NTV) has dedicated an episode to Odessa (2013), citing many popular dishes and locations. The Odessan episode of another cooking show, Gotovim vmeste (Cooking together, Inter) starts with the hosts welcoming the viewers using stereotypical Odessan phrases and thus setting the atmosphere. The presenter of the show Domashnyaya kuhnya (Home Cooking, Domashniy), Katsova, hosts celebrities and often introduces them to traditional recipes inherited from her Odessan grandmother. On YouTube, an entire channel is dedicated to Odessan cuisine.[2]

Food defines us in many ways and helps us find common ground with people around us (Yakovleva 10). While eating is something that everybody does, and which may seem trivial, it is an important part of festivities and something that distinguishes us from another, and within this framework, restaurants have a significant role as “places for chefs to recreate their cultures and for diners to mold their identities” (Park 366). In multiethnic places, cultural “melting pots” such as New York, or Odessa, the opportunities to mold one’s identity by sampling dishes from different culinary traditions are infinite, and the occurrence of fusion cuisines is inevitable. Thus, food and different “culinary” codes play a crucial role in intercultural communication and create their own semiosphere, which extends itself beyond the mere ingestion of various foods (Parasecoli).

Food is an important part of national culture. Being able to cook foods of one’s tradition can even become an empowering experience. For example, during the Soviet times, anti-Semitic tendencies were strong, and many ethnic Jews preferred to hide their origins. Nevertheless, as Hoffman argues, “the Soviet government could not monitor … the cooking of ethnic foods” (110), so the traditional Jewish foods, such as matzah or latkes, and the Jewish versions of some dishes, such as borscht or blintzes, lived on, although limitedly. In Odessa, many typical Jewish dishes are still considered essential to the local culinary tradition, although a vast majority of Odessan Jews left the city during the decades following WWII.

Materials and Methods

In this article, I aim to explore the distinctive features of Odessan cuisine and their survival in immigration, and for this purpose, I analyse different sources, such as personal archives shared with me by their owners, the internet (websites, Facebook, YouTube, and other social media), and cookbooks. I use the gastropoetic approach in analysing the literary manifestations of Odessan culinary traditions, for example, in works by Mihail Zhvanetsky and several other authors, and analyse other sources, such as users’ comments on the web, the menu descriptions, and Facebook posts.

To illustrate which elements of traditional Odessan cuisine have been preserved by and appeal to Odessans and immigrants from Odessa, I analyse the concepts and menus of two restaurants, one situated in Odessa and the other one in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn. One of the restaurants, Dacha (The Vacation House) owned by the Odessan chef Savely Libkin, author of the books My Odessan Cuisine and The Odessan Feast from Privoz to Deribasovskaya; the other one is Volna (The Wave) in Brighton Beach. First, I will present the restaurants and their locations and give an overview of their menus, as well as customers’ reviews and comments. Then, I proceed by individuating the dishes that can be attributed to Odessan cuisine and observe which of the dishes appear on the menus of both restaurants.

Odessan Cuisine

Not unlike Italians, one of the nationalities that contributed to the development of Odessa both as a city and as a cultural centre, Odessans have a particularly passionate and meticulous approach to food. The location by the sea, in a mild, southern climate, with a busy international port undoubtedly contributes to the fact that Odessans are used to a certain variety of fresh and/or exotic foods not easily available elsewhere in their country. According to Polese (78):

Odessa and Batumi were in a unique position. On the one hand their climate allowed people to take advantage of natural resources: both regions produce good vineyards and the soil is adequate to grow vegetables and fruits, at least some months of the year. They were, and are, also relatively close to other countries like Moldova or Armenia, which facilitates exchanges of different products. Finally, they were two important ports and most shipments to Moscow passed through one of those two cities (where, incidentally, a decent amount of goods disappeared on the way).

Thus, many of the traditional dishes require specific ingredients, such as particular varieties of vegetables (e.g. Mikado tomatoes) or fish only found in the Black Sea.

Odessan cooking, like the city itself, is eclectic and multi-ethnic. In Odessan cuisine, we can find elements of Russian, Ukrainian, Jewish, Greek, Georgian, Bulgarian, Romanian, and other culinary traditions, which is due to both its demographics and its geographic position. In his foreword to Saveli Libkin’s cookbook, Mihail Zhvanetsky describes the characteristics of Odessan cuisine as follows:

Odessan food loves to rest, you should not take it from the stove and quickly devour it. You need to leave it on the stove or in the fridge. The Odessan market inebriates you with its scents. So does the Odessan dill. The Odessan garlic glues your fingers together. The Odessan mackerel detaches itself from its spine and melts in your mouth. The eggplant caviar (eggplant spread- IK) spices up and aromatizes any given pork chops. The Odessan red borscht is made with beans. The green one with eggs… From only one chicken you obtain the stuffed neck, the stuffed legs, the broth and the noodles. In Odessa, the wine goes by the name ‘dad made it’ and it needs to be sucked with a straw from a 12-liter glass bottle. (Zhvanetsky in Libkin)

Prigarin writes that different nationalities present in Odessa since its early years specialized in producing and/or selling various kinds of foodstuffs, for example, the Greeks specialized in fish and Mediterranean “colonial products” (olive oil, citrus fruits, etc.), Bulgarians in local fruit and vegetables, and Moldovans in ovine milk derivatives (several types of cheese). Consequently, alongside the raw ingredients, various diasporas introduced their traditional recipes, which, with time, blended into what is now referred to as Odessan cuisine.

The authentic Odessan cuisine starts at the famous Privoz market where you go grocery shopping or “delat’ bazar,” literally to “do bazaar.” Since it was first established (Gubar), Privoz has acquired a special status amongst famous Odessan locations. It has always offered a vast variety of imported goods nearly impossible to come by in other places. In fact, a famous joke states that “the atomic bomb does not exist because if it existed you would be able to buy it at Privoz” (Apostol-Rabinovich). Odessans often argue that it is impossible to prepare real Odessan dishes outside of Odessa as the only possible place to find the right ingredients is Privoz. Going there can be compared to a ritual; as Katsova, an Odessan celebrity chef and TV personality states:

Going to Privoz is like going to a wedding, a festive outing, a birthday party. Any self-respecting Odessan woman has a special bag for it (usually a trolley). She even wears special lingerie for the occasion, believe me.

Polese and Prigarin (113) describe the importance of bazaars of Odessa, such as Privoz, as follows:

In spite of supermarkets mushrooming, the bazaar has been evolving to occupy a niche in the economic and social life of Odessans and this is not necessarily, or not only, depending on the low-price of the products; in contrast, in some cases prices might be higher (or higher is the likelihood to be ripped off), conditions might be worse (no trolleys, cold in winter). Bazaars, in this respect, incarnate a desire to concentrate on values other than monetary ones and that the main reasons why the bazaar has survived in Odessa are twofold. First, the new demand in consumption has prompted a transformation of bazaars from a place where things happen to a cultural and economic space where traditions are preserved, social relationship enhanced and transactions, not necessarily money-oriented, are carried out. Second, originally a place where meat, vegetables and subsistence goods were sold, bazaar, in Odessa have evolved into places where virtually everything can be found, be this food, clothes, furniture, legal or illegal goods.

However, the legendary “kolorit” flavour of Privoz (presumably from Italian “colorito,” colour) is sometimes feared to have faded (Zhukova). The “kolorit” is an essential component of the Odessan identity. The term comprises everything that makes Odessa – the Odessa we know. Its language, its humour and the wittiness of its people, its contrasts (e.g. the shabbiness of the courtyards on Moldavanka and the grandeur of the Opera House or the famous Potiomkin Staircase), and, of course, its flavours. Nowadays, many Odessans lament the disappearance of this “kolorit,” due to the mass emigration of Jews, and immigration of residents from other parts of Ukraine, the generational change, and the overall globalization. According to them, what is left is the myth, alongside the myth of Old Odessa and Odessan language. However, the appearance of new written (e.g. https://odessa-life.od.ua/article/odessa-na-voennom-polozhenii-den-112-j-sho-pochem) and video content online (Shinder) (e.g. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bs7O5aF-wv0) regarding Privoz and its people contradicts this claim. Consequently, one could presume that the Odessan “kolorit” has not disappeared; instead, it has transformed, following the times. Whichever the case, the appeal of Privoz, especially to the visitors of the city, remains strong, and it is still viewed as a place where one can venture for more than just groceries:

The faded sign with the writing ‘Privoz’ reminds the old Odessites of the real, authentic Privoz where they used to love to go, and not only to buy fish or apples, but simply to socialize, to ask ’how much does it cost’ or as they say in Odessa ‘for how much?’, to assess the assortment, to take a stroll, to have breakfast and maybe even lunch! (Unknown author number 6, “Mini Saga o Privoze,” Odesskiy Forum)

What has most impressed travellers visiting Odessa since the early nineteenth century is not so much the quantity of products that can be found at Odessan markets, but the immense variety thereof (Prigarin 34).

Odessan Recipes

The recipes of Odessan culinary tradition are countless, but some of them seem to have obtained a privileged position in cookbooks and people’s consciousnesses. The much-cited eggplant spread is often mentioned. This dish can be considered the most widely known and reproduced Odessan recipe, likely due to the relative ease of obtaining ingredients for its preparation compared to some other recipes, such as dishes that require the use of particular types of fish. These fish dishes include the famous forschmak, an Ashkenazi Jewish dish adopted and adapted by Odessans, as well as gefilte fisch of the same origin.

No, wait, what’s this, can’t you have a tasty meal at home? I have already cooked everything, this morning! The gefilte fisch and the forschmak and the sinen’kije (the blue ones, i.e., eggplant – IK)! (Aunt Pesya in S. Ursulyak’s TV series Likvidatsiya [Liquidation])

Odessan writer Birstein vividly illustrates the importance of forschmak and the ritual of its preparation in an eponymous short story. Using hyperboles, typical of Odessan speech, he humorously describes a scene in which the inhabitants of an Odessan courtyard discover that certain acquaintances of theirs do not put apples in their forschmak, an offence comparable to a declaration of war. Apart from this omission ruining the dish, what really elicits belligerent emotions is the thought of such an abomination being linked to the good name of Odessan cuisine:

But Herzen killed the mood right away.

– What if they get visitors? – he asked.

– What visitors? – auntie Marusya asked, not getting the point.

– From America or from Berdichev… – Herzen dismissed her annoyedly. – What difference does it make?

– So what? – auntie Marusya still couldn’t grasp the point.

– So, they treat their visitors to this forschmak. And the visitors eat it! – Herzen’s voice was trembling painfully. – And then the visitors go back home. And start making forschmak like this. And saying that it is the real thing, the real Odessan forschmak…

Having grasped the closeness of the precipice from which the hateful Rabinoviches were about to throw the beloved city, the people’s mood became aggressive. (Birstein)

Fried gobies and Black Sea sprat patties are also included amongst the top Odessan specialties. Here, an unknown author of a MyOdessa-website entry (myod.info/odessa-kulinarnaya-gid-po-ede-ot-kotoroj-begut-slyuni-i-drozhat-koleni) takes a rather poetic approach to the description of the patties:

If you want to experience the real Odessa, take some young Bessarabian wine and fish patties and consume them at sunset, and you will feel a taste you will not be able to forget for a long time. (Author unknown)

Also, seafood, such as mussels, prepared in various styles, and numerous variations of stuffed, fried, or marinated fish are popular. The mullet (kefal’) is widely associated with Odessa because of the famous song Shalandy polnye kefali (lighters full of mullet) performed by Mark Bernes.

Lighters full of mullet

Kostya brought to Odessa […] (Bogoslovsky and Agatov)

Among meat dishes, we can find the world-famous beef Stroganoff, usually attributed to the Russian culinary tradition. However, the legend has it that count Stroganoff, who was the governor-general of Novorossiya (which included Odessa), used to keep an “open table” that served anyone educated and decently dressed, and for this purpose, his chefs invented this easy and quick-to-make dish (author unknown, myod.info/odessa-kulinarnaya-gid-po-ede-ot-kotoroj-begut-slyuni-i-drozhat-koleni). Another version of the legend attributes the birth of this dish, consisting of small strips of meat sautéed in sour cream and tomato sauce (although the variations are numerous), to the fact that when the count reached an advanced age, he had bad teeth and so, his chef decided to cut the meat into small pieces to make his master’s meals easier (Ivanov).

Other Odessan meat dishes comprise stuffed goose or chicken necks, sweet peppers stuffed with meat, and “pinky-sized” stuffed cabbage leaves. Here, we can observe influences of Jewish (chicken and goosenecks, a.k.a. “gefilte Helzel”), Hungarian (sweet peppers, a.k.a. “töltött paprika”), and Greek (stuffed cabbage/vine leaves, a.k.a. “dolmades”) cuisines. Besides the eggplant spread and forschmak cited above, appetizers include, for example, the tomato salad with salty brynza cheese (similar to feta), the “Privoz loader” sandwich (rye bread with cheese spread, sprat fillets, and fresh green onion), and bean tzimmes.

Food Away from Home

When immigrating to a new country, newcomers often face problems when attempting to cook familiar dishes, as they cannot find the right foodstuffs to buy or the right tools to cook with. The cultural shock due to different factors, such as not knowing the local language or everyday life habits, can result in severe stress with long-lasting consequences. Moreover, food is something people frequently turn to when they need comfort or stress relief, and in the case of immigrants, it becomes even more important for its emotional and nostalgic implications. On the one hand, cooking or eating familiar dishes in an otherwise “hostile” situation or environment provides a momentary sense of belonging, of home. Citing Kershen (203), “For those in an alien land, diet is one means of preserving identity and links with home.” On the other hand, in a globalized world of food chains, it can help in levelling out differences, both cultural and ethnic, regional and local (Cook and Crang), meaning that today global restaurant chains can be found in many countries of the world. They are familiar to a great number of people and thus can mitigate the sense of alienation. For example, if the same fast-food chain you used to go to in your home country can be found in your host country, you can feel reassured by this familiar presence. Here is a story from my personal experience that I find rather illustrative of what was stated above. When I was a young student, I was traveling in Italy with a group of other students from different countries (Malaysia, Turkey, Germany, and Sweden, to name just a few). At a certain point, after nearly 3 weeks in the country, a girl from Sweden was feeling homesick and complained that she could not stand any more pasta. So, that night, we all went to a well-known American fast-food restaurant, and my Swedish friend’s homesickness dissolved.

Visiting ethnic restaurants can even be compared to traveling and discovering new worlds without leaving one’s hometown (Zelinsky). Numerous scholars have addressed the subject of ethnic cooking and ethnic restaurants and their impact on local food culture, as well as their significance for immigrants themselves (e.g. Gabaccia; Link; Markwick; Diaz and Ore). This connectedness may be seen, among other things, in who owns the property, where the foodstuff comes from, who cooks, who comes to taste and experience something new, and who just comes to eat familiar dishes. However, according to Azar et al., when ethnic foods are concerned, traditional daily foods and traditional festive foods are often confused, and many immigrants tend to consume more frequently those dishes that were reserved only for special occasions in their homelands. These foods may be more affordable in the host country, or modern life sets up new standards of cooking and eating. As a result, these dishes are erroneously perceived as “typical” by the local inhabitants of the host country and reinforce the view of immigrants that their lives here are better than before (Azar et al.). It is possible to presume that this sometimes leads to the erroneous perception of what national or ethnic cuisines are and to how immigrant life appears to those who remain in their home country.

Brighton Beach as “Little Odessa”

The current study addresses the food culture of Odessa and immigrants from Odessa. Emigration from the USSR was generally greatly restricted until 1989, and only selected categories of citizens could attempt to obtain permission to leave the country. The first waves of Jewish mass emigration from the Soviet countries took place between World War I and World War II, but then, from 1946 on, it was made extremely difficult (Fialkova and Yelenevskaya 613). Over the following decades, even when the emigration policy was seemingly loosened, numerous applications for emigration were rejected without any evident reason (615). In the United States, the most significant influx of Soviet immigrants, mainly Russian speaking Jews, began in the 1970s as a consequence of loosened emigration policy (Frankel) and continued following the collapse of the USSR (Isurin). The location that presents a particular interest in this context is Brighton Beach in southern Brooklyn, New York. The settlement was originally founded right after the American Civil War as a seaside resort and a popular location for outdoor activities, leisure and cultural life, such as theatre; however, the area’s popularity and economy were in decline from the 1930s to the 1970s (Conn). Brighton Beach became the chosen destination for many of the third-wave Soviet immigrants, one reason being its pre-existing Russian and Jewish population, with some having family members already living in the area (Conn). Although the newly arrived Russian Jews were welcomed by the American Jewish community, the latter were disappointed to find that their Russian counterparts were mostly secularized and willing to maintain their Russian or Soviet identity in their new home country (Gitelman). This also included their culinary habits. Although the majority of Russian/Ukrainian Jews seem to have positive attitudes towards Judaism and Jewish traditions, “A typical mid-age Russian Jewish immigrant who knows very little about Judaism is, nevertheless, attracted by it because he believes that this is the religion of his ancestors. He may simultaneously attend a reform synagogue because it is close to his home, invite an orthodox rabbi to officiate at a Bar Mitzvah ceremony, put up a Christmas tree, admire the Russian Orthodox architecture, and admire Buddhist meditation” (Kliger 6).

Various businesses were born because of the desire of the Soviet immigrants of Brighton Beach to preserve their cultural background and the need to find a piece of home in a foreign land. Even now, nearly 40 years later, the shops there stick to the heritage of Russian design and offer only “quality” things that can be appreciated by Russian speakers. Gradually, Brighton Beach became “Little Odessa,” due to the significant number of immigrants from that city (Miyares). A 1983 article from the New York Times Sampling Food in Brooklyn’s “Little Odessa” describes the M. & I. International Food shop in Brighton Beach as follows:

Except for the bountifully stocked display counters and some boxes of American breakfast cereal the shop could be a scene in Odessa or Kiev. Virtually all the food signs are in Russian without English subtitles and not a word of English could be heard. (Miller)

One point that repeatedly emerges in discussions regarding the micro-world of Brighton Beach is the juxtaposition of nostalgic (positive) and uncomfortable (negative) flashbacks to the Soviet era. On the one hand, the nostalgia and the desire to maintain a link with the past and the country of origin manifest themselves in everyday life through the ever-lasting popularity of Russian products, the presence of business names recalling those of the Soviet past (e.g. Dom obuvi) and the use of Russian language not only for practical but also for sentimental reasons (Litvinskaya). On the other hand, these factors might appear as something to avoid in order to forget the past life in Russia or the Soviet Union. Anna Strukova, a travel blogger who writes in Russian, summarized her experience as follows:

Brighton Beach is like a showcase of the past, an echo of the first waves of the “sausage emigration”. The people who crossed the ocean had a Soviet mentality, and that is why they recreated a similar environment around themselves. … All in all, Brighton Beach was worth visiting to understand that if one ever moves to America, one should move wherever, except Brighton Beach!

While it is true that some post-Soviet citizens may feel nostalgic about the Soviet era and idealize the past, it is important to note that not all immigrants from the former Soviet Union who reside in Brighton Beach share this sentiment. Furthermore, it would be inaccurate to say that immigrants in Brighton Beach encounter the “best possible version” of that non-existing country. The Soviet Union was a complex and diverse country, and different people had different experiences based on their background, social class, and other factors. It is true that the Brighton Beach neighbourhood has a strong cultural connection to Russia and Ukraine and that many residents celebrate their heritage through traditions, language, and cuisine. However, it is important to avoid oversimplifying the experiences of the people who live there or assuming that they all share the same attitudes towards the Soviet past.

Over the years, Brighton Beach has become part of the popular culture; it has been featured in jokes and films such as Weather Is Good on Deribasovskaya, [3] or It Rains Again in Brighton Beach (Na Deribasovskoy khoroshaya pogoda, ili na Brighton Beach opyat’ idut dozhdi, 1992[4]) (Gaidai) or Little Odessa (1995) (Gray).[5] The general idea of Brighton Beach as a Russian (speaking) enclave is well described in this joke:[6]

One of the Russian emigrants comes to Moscow to visit his relatives. Among other things, they have a request for him: they have a video tape with an interesting film, but they cannot understand who the killer is, as the actors speak English too fast.

- Uncle, help us translate it.

- Sorry, guys, I cannot, I do not understand English.

- How can that be? You have been living in America for 15 years!

- I live in Brighton Beach and we never go to America.

(Strukova)

I argue that Odessa is not just a place, but a myth, and one of the main manifestations of this myth, alongside language, is food. Although food history and immigrant food culture have been addressed in various works, Odessan food and especially Odessan cuisine abroad have not been sufficiently studied from the point of view of their significance to the survival of the Odessan myth. There are numerous books, blogs, and nostalgic websites dedicated to Odessan cooking, but they rarely go beyond providing recipes for the most widely known dishes. Thus, I investigate the subject of Odessan cuisine, both in Odessa and abroad, in a more thorough manner, including the sociolinguistic aspect of food by analysing the ways Odessan cuisine is talked about and written about.

Food in Standard and Poetic Language

Odessan language and food play a significant role in the formation of the Odessan identity. According to Montanari (133), spoken language and food are linked as they can both be considered factors that “convey the culture of its practitioner” and are “the repository of traditions and of collective identity.” He also states that food is a way of establishing contact with a culture different from one’s own, as it is easier to taste the food of the “others” than to learn their language (ibid.). Food narrative holds a relevant position in literature; the description of different foods, their preparation processes, and the rituals of food consumption creates an image that allows us to reconstruct the cultural context of the text in question.

For example, P. Neruda dedicated 19 of his odes to food, to the simplest of ingredients, such as tomatoes, onions, and potatoes (Salgado), with his words transforming them into something precious and sought after. Roy applies the term “gastropoetics” to the reading and interpretation of texts describing food in all its aspects, similarly to Mannur and Highrmore, whereas Cutter takes a broader approach and claims that gastropoetics is a “complex of relationships involving food, cultural practice and cultural memory, poetic inheritance and poetic production, social bonds and social identity.” I find the term gastropoetics quite appropriate in the framework of the present study, as in literary works featuring Odessa, both fiction and non-fiction, a simple act of cooking or eating often becomes a poetic experience involving all senses.

Oh, the smell of the blue ones (eggplants), cooked on an iron cast pan, and the onion fried in the real goose grease preserved for the winter. My God, when you spread the pickled pork rinds on a slice of rye bread, you can forget about the existence of industrial sausages. (Litevsky)

The dark gray, spongy, soft, soft bread … Porous, brown, with crunchy crust and soft, delicious crumb… And if you have the home-made butter? … If you spread it on the bread, no, not the white one, but the brown one … I can’t imagine how you could fail to devour it, it is pure ecstasy! If you have the small, salty sprats, so tiny. And the hot, small potatoes. Moving further… No, not further, but closer, there is a soup plate, full of eggplant caviar with onions finely chopped and integrated within… All this is to be consumed with the velvety, black tea, for a better conductivity. … But these are mere courtiers. The real Empress is mullet cut into pieces. Fried and slightly tart. You will desire to take her while she is hot and burns your fingers! To take the pieces from the serving plate, with bare hands, and put them onto your plate, and to open them up, and sprawl them […] (Zhvanetsky)

All the foodstuffs cited in the quotes above are rather basic (bread, butter, eggplants, onions, and fish) but from the gastropoetic point of view, these simple ingredients solicit a nearly ecstatic response from the authors, which manifests itself in a verbal feast of metaphors and allusions, vividly depicting the scenes of everyday bliss. The reader can almost sense the aromas, the flavours, and the texture of the foods described, and perceive the particular southern atmosphere of the place where they are served and consumed, that is, Odessa. Although one can argue that the described foodstuffs were and still are widely available in the Soviet and post-Soviet countries, they were often regarded as something rather boring. But the way Zhvanetsky describes them makes them seem like exotic delicacies possible to find only in Odessa.

The way people speak about food can reveal meaningful details about their culture. Especially in the past, a great majority of Odessa’s inhabitants were Jewish, and, according to Diner (225), Jews were “a group of people who venerated food and described their hopes, dreams, and deepest memories in terms of food.” The same statement can equally be applied to other nationalities inhabiting Odessa (Ukrainians, Russians, Georgians, etc.) and thus Odessans in general. They seem to profess a great attachment to food not only in terms of nutrition, but also in terms of culture and their Odessan identity. In Odessa, a favourable climate and the historical status of porto franco (free-trade zone) have always resulted in an abundance of different types of merchandise, and foodstuffs, difficult to obtain in other parts of the country: exotic spices, autochthonous varieties of fruit and vegetables, fresh fish, and seafood. Moreover, in a culturally and ethnically eclectic context, it becomes more important than ever to find a common meeting point, and food offers favourable grounds for that. In Odessa, food is so important that one of the first authors ever to use the term “Odessan language,” Doroshevich, compares it to food when he states that “Odessan language is like a sausage, stuffed with languages of the entire world, prepared in Greek style, but with a Polish sauce” (68). The multiethnicity, its eclectic character, the variety of ingredients, and the mobility, in terms of migration, make the case of Odessan cuisine particularly interesting to study.

In the next section, I will analyse the traits of Odessan cuisine on the menus of restaurant Dacha in Odessa, and restaurant Volna in “Little Odessa,” on Brighton Beach, New York, and address the online discourse regarding them.

Restaurant Dacha

Savely Libkin, a well-known Odessan chef and entrepreneur, describes his work as a mission:

I love and know how to cook – this is the path I chose to unveil my hometown to the world. Reviving and glorifying Odessa cuisine, creating restaurants that become city sights, I strive to ensure that the name “Odessa” evokes not only a dreamy smile but also awakens appetite.

Situated on the French Boulevard, in Odessa, the restaurant itself is described as a cozy place where one can feel at home and experience quintessential Odessa:

There is no place for chic, gloss or pathos. Here, instead of high heels and suffocating ties one wears comfortable sandals and widely unbuttoned collars. And, of course, here you can find traditional Odessa cuisine, cooked without fads but with knowledge. Here you can feel yourself a summer resident for at least a day – this is true Odessa happiness!

The name of the restaurant, Dacha, induces us to think about a comfortable and relaxed place where, as in the presentation above, no formalities are required. Although the location hardly reminds one of a simple summer cottage but is a mansion-like building with a spacious garden, Dacha is intended more as a romanticized upper-class summer residence than the dachas of the proletariat with their standard 600 m2 of land. The interiors are cozy but refined, and although the cuisine is apparently simple, a lot of care is put into food presentation and serving. Libkin owns several restaurants in Odessa, but Dacha is branded as the one serving traditional Odessan cuisine. In fact, the menu states, “Classic Odessa Cuisine since 2004” and serves many of the most popular dishes of Odessan culinary culture. On the menu, there is a subcategory for “Odessa Local Specialties and Appetizers,” and among these, we can find, for example, the entries cited earlier, such as herring forshmak, gefilte fisch, eggplant Auntie Betya’s style (eggplant spread), and stuffed chicken neck with carrot tzimmes (Restaurant Dacha). On the restaurant’s Facebook newsfeed, the stuffed chicken neck is described in a very poetic way:

She, like a real Odessan lady, has absorbed the aroma of the chicken broth, the nuances of the butter and the sweet and spicy flavour of the carrot tzimmes (Restaurant Dacha).

No less colourful is the portrayal of fried gobies:

The main principle of the Odessan cuisine is its delicacy and finesse. But every rule has its exception. And in this case, we are talking about the real Black Sea gobies that are distinctive for their “not so delicate” size (Restaurant Dacha).

These examples, emphasizing the restaurant’s Odessan heritage, are only some of the many that can be found on social media and various marketing channels.

Besides fried Black Sea Gobies and fried Black Sea red mullet, the pinkie-sized minced meat cabbage rolls can be found in the menu of the main courses. Among meat dishes Georgian-style skewered charcoal-grilled meats (shashlyks and kabobs) are well represented, and when it comes to soups, we find red borscht and chicken broth with noodles served with giblets. Vareniki and pelmeni, dishes of Ukrainian and Russian tradition, respectively, are also present. Compared to the Volna menu discussed below, this one is less varied, but when it comes to purely Odessan specialties, they are better represented and distinguished at Dacha, which places them as a subcategory on the menu, whereas at Volna they appear more scattered throughout the menu. The multinational culture of Odessa is also reflected in Dacha’s concept, as various “ethnic” culinary events, such as Georgian or Bessarabian (from Moldova) theme days, are occasionally organized by the restaurant.

Notwithstanding the fact that Dacha is situated in Odessa, the media communication regarding the restaurant is strongly based on nostalgia linked to the authentic Odessan spirit, and judging by the location and the design of the place, the longing for the past when upper-class families resided in their dachas and enjoyed the exotic atmosphere and culinary masterpieces of Odessa still attracts customers. The myth of “Old Odessa” is the myth of Odessa familiar from descriptions by A. Pushkin, V. Katayev, I. Babel’, and other classics, and the one recreated in various films, starting from The Battleship Potiomkin by S. Eisenstein, and lately revived in such TV films and series as Likvidatsiya. The nostalgia evoked by restaurants like Dacha is prevalently the nostalgia for a place and a time that none of the potential customers have had the opportunity to experience first-hand, due to their age (not many of those who still remember the “Old Odessa” are still living), but also due to “Old Odessa” being a collective myth, an image of a city reconstructed by different generations of Odessans and visitors of the city. Therefore, it could even be stated that the nostalgia for “Old Odessa” is second-hand nostalgia, but nonetheless, it is a crucial factor that maintains its appeal year after year.

Restaurant Volna

Volna (Wave) was a popular name of restaurants in the Soviet times. In Russia, there are restaurants called like this in numerous towns, e.g., in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Barnaul, Kemerovo, Svetlogorsk, and Taganrog. It is also one of the best-known restaurants in Brighton Beach, partly because of its 30-year-long history and partly because its location was featured in a scene of the above-mentioned film Weather is good on Deribasovskaya, It Rains Again in Brighton Beach. Located on the legendary Riegelmann Boardwalk and founded by immigrants from Odessa, the restaurant profiles itself as one offering Russian, Ukrainian, and European cuisines. Besides its convenient location, Volna is popular because of its abundant, high-quality dishes. On its Facebook page, the concept of the restaurant is described as follows (Cafe Volna):

It is no secret that Brighton Beach is practically beaming with Russian speaking immigrants, and most of them came from Odessa, Ukraine. When we started up way back 30 years ago, we understood perfectly well how much these immigrants miss their own country, and this is what has inspired us to come up with the perfect place where they can enjoy sipping coffee and eating sumptuous Russian dishes that will remind them of their home while they chat with their friends and loved ones and relish the wonderful scenery that Brighton Beach has to offer (the original form and language of the post has been maintained – IK).

From this description, we can conclude that 30 years after the restaurant opened, the target clientele of Volna is still the immigrants. Nostalgia is strongly present in phrases such as “immigrants miss their own country” and “dishes that will remind them of their home”; thus, the intended message is that Volna is a place of comfort where you go to soothe your homesickness. If we consider some of the reviews left by Russian-speaking users online, we notice that nostalgia, alongside the cooking, is among the reasons to visit Volna:

A piece of homeland!

Volna simply oozes with the atmosphere of the oh-so-dear and oh-so-far Russia, the cooking is excellent, even if it had the highest prices in NY, I would still go there! I recommend it to all.

(https://restaurant.rusrek.com/restaurants/get/volna/comments/65) (Russkaya Reklama)

An excellent restaurant with Russian cuisine. The staff is excellent, they bring everything on time. I’m feeling nostalgia for my homeland. I recommend it to all. Go try it, you won’t regret it.

(https://restaurant.rusrek.com/restaurants/get/volna/comments/95) (Russkaya Reklama)

Russian food

Ladies and gentlemen, this restaurant serves real Russian food! The taste of the Homeland! I recommend it!

(https://restaurant.rusrek.com/restaurants/get/volna/comments/120) (Russkaya Reklama)

Nostalgia

A good restaurant, but expensive. Nevertheless, even if 15$ for a cutlet (Kiev style) is steep, I ate it with great pleasure. The taste reminded me right away of my hometown Kiev and my careless childhood!

(https://restaurant.rusrek.com/restaurants/get/volna/comments/215) (Russkaya Reklama)

In the comments above the word nostalgia itself is frequently used, along with words like homeland or hometown. Some of the customers are even willing to pay more than usual (“even if it had the highest prices in NY” and “15$ for a cutlet”) to experience the feeling of going back in time.

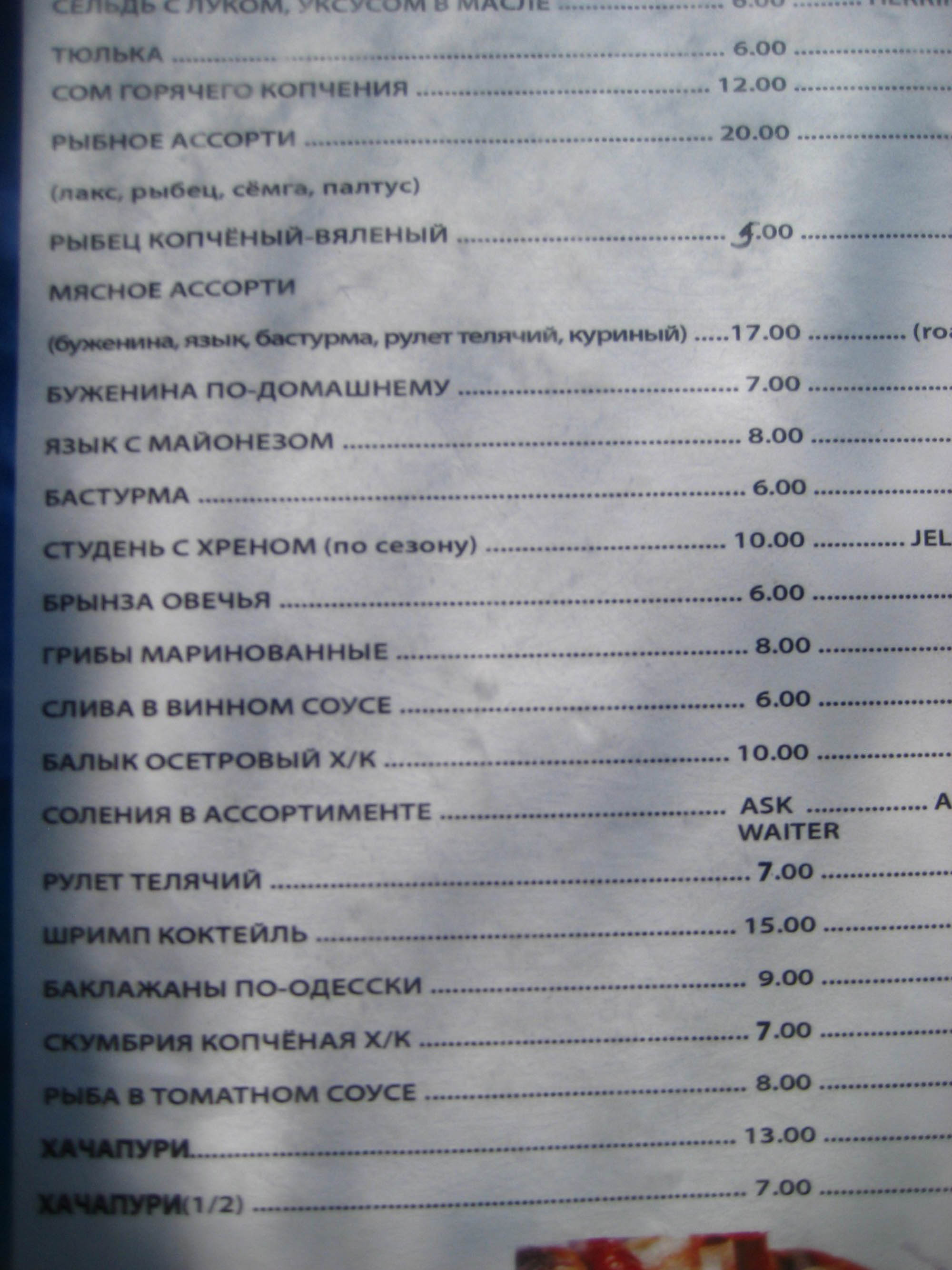

Analysing the menu of the restaurant and aiming to trace features of Odessan cuisine, what becomes evident is the significant variety of dishes of Russian (different types of pelmeni, solyanka soup), Ukrainian (vareniki dumplings, cutlet Kiev style), Georgian (khachapuri, skewered meet dishes, and kharcho soup) and European tradition (Lamb French style, foie gras), with some traits of American food culture (Caesar salad and shrimp cocktail) as well. As stated previously, Odessan cuisine is rather eclectic; thus, the variety of foods from different traditions, as well as the generous amount of seafood and fish dishes on the menu, is typical of an Odessan restaurant. The latter characteristic can, obviously, be attributed to Volna’s location by the ocean, but the presence of some typically Odessan types of fish on the menu, such as fried flounder (zhareny glos’) or the Black Sea turbot (chernomorskaya kambala), distinguishes it from other New York seafood restaurants. Fried gobies (zharenye bychki), which used to be a popular street food, and Black Sea sprat cutlets (bitochki iz tiylki) seem to be absent from the menu (although sprat as an appetizer is present), despite being some of the most quoted and traditional Odessan dishes.

Relatively few dishes from Jewish cuisine can be found on the present menu, with one of the most obvious that is currently served being chicken broth with knish. When it comes to dishes associated with Odessa, and especially with Odessan Jews, the version of the menu under analysis notably does not include the famous forschmack, an appetizer made with fish (herring) chopped tartar style, seasoned and served with rye bread or matzah; or the gefilte fisch, stuffed fish, a recipe of paramount importance in the Odessan Jewish tradition, especially from the point of view of a Soviet citizen.

The most obvious reference to strictly Odessan cuisine is the dish called “eggplant Odessa style” (baklazhany po-odesski), which presumably equates to eggplant spread/caviar or ikra iz sinen’kih, the previously mentioned appetizer made from baked eggplant, sweet peppers, and tomatoes. All in all, at the time of writing, restaurant Volna can be said to be Odessan, considering its origins and presence of several Odessan traditional dishes on the menu, but on its marketing channels, such as its Facebook page, it does not advertise itself as predominantly Odessan but rather Russian or European, which is not particularly surprising, considering that the concept of “Odessan cuisine” is not as well-known as, for example, the Russian cuisine and that Odessa is situated in Ukraine. At the same time, the concept of Russian cuisine has agglomerated many of the culinary traditions of all the other ex-Soviet countries, which means that colonization happened also on the food level.

From the linguistic point of view, the restaurant’s menu includes translations of certain dishes from English into Russian that have some peculiar traits, such as using transliterated English words with Russian suffixes. This is particularly evident in the translations of fish dishes, where we can observe the Russified transcriptions of shrimp (шpимп, шpимпы, Russian: кpeвeтки, krevetki), seafood (cифyд, Russian: мopeпpoдyкты, moreprodukty), tuna (тyнa, Russian: тyнeц, tunets), salmon (caлмoн, Russian: лococь, losos’), scallops (cкaллoпc, Russian: гpeбeшки, grebeshki), clams (клэмc, Russian: вeнepки, venerdì), and seabass (cибac, Russian: лaвpaк, larvae). This tendency is curious, as all of these words have equivalents in Russian, and leads me to conclude that either the authors of the menu simply did not know the words in Russian (e.g. they could be second-generation immigrants who still speak the language but lack some vocabulary) or that this is the general trend in Brighton Beach. When it comes to clams and seabass, using the Russified English (or, in the case of clams, Italian ‘vongole’) words also seems to be the standard in Russian-speaking culinary context outside Brighton Beach, but the same cannot be said about the rest of the examples above, which reinforces the hypothesis that their use is a local/individual linguistic peculiarity, especially because a similar tendency can be found in the menus of other restaurants in Brighton Beach. For example, Alena Litvinskaya cites the following:

[…] l ess fancy cafés offer a variety of dishes in émigré Russian, like―Caлмoн в Бeлoм Coyce (sal m on v b’elom souse)―Salmon in White Sauce and―Tyнa в Ceceми Coyce c Aвaкaдo Cивид Caлaтoм (tuna v sesemi souse s avakado sivid salatom; these should all be written in small letters in Russian, an En g lish language influence, and avocado, the influence of the spoken variant of Russian - IK )―Sesame Seared Tuna in Oceanview Café, or ― Caлaт из шpимпoв (salat iz shrimpov)―Shrimp salad and―Cифyд accopти (sifud assorti)―Seefood salad in Café “Arbat.” (148)

Conclusions

National or ethnic cuisine is an important part of an individual’s identity and particularly in immigrant populations, where preparing or consuming familiar foods becomes a refuge in intimidating and confusing new surroundings. Going to a restaurant that serves dishes typical to one’s own culture or country of origin becomes a safe and comforting, as well as nostalgic, experience. However, explicitly Odessan restaurants, both in Odessa and abroad, can be said to be more than simply ethnic; Odessa becomes a special brand, something particularly exotic.

In accordance with Montanari, and especially when it comes to Odessa, language and food are strongly interconnected. In some cases, the description of foods or meals can be transformed into poetic narration and evoke strong emotions. Nostalgia is frequently present in food narration; writing, reading, or speaking about certain dishes helps us to recreate a certain time or place. In fiction, but also in (auto)biographic and documentary literature, scenes describing food can define the atmosphere of the entire story by allowing us to locate the characters and the events in one or another cultural context.

Odessan cuisine might not be as widely known or as recognizable as, for example, Russian or Ukrainian cuisines, but in Odessa and for Odessans, food is of paramount importance, and today, Odessan chefs work specifically to make Odessan culinary traditions better known worldwide. This passion for cooking and eating translates itself into a willingness to discuss food whenever possible and to introduce the world to the excellence of Odessan food, especially through the literary efforts of both established authors (Zhvanetsky) and simple food lovers. The gastropoetic side of Odessan food narration is significant, as frequently mere descriptions of breakfasts, lunches, and dinners are transformed into flavourful poetic feasts. Simple foods and dishes (bread, fried fish, and eggplant spread) are depicted as heavenly pleasures. Consequently, this creates specific expectations in clients of Odessan restaurants, and the restaurants themselves take on a mythical aura of places where the magic happens.

Brighton Beach is a neighbourhood located in the southern part of Brooklyn, New York City. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a significant influx of immigrants from the city of Odessa, Ukraine, particularly Jewish immigrants who were fleeing anti-Semitic persecution in the Soviet Union. As more and more immigrants from Odessa settled in the area, the neighbourhood began to take on a distinctly Russian and Ukrainian character. Today, Brighton Beach is often referred to as “Little Odessa” due to its large population of Russian and Ukrainian immigrants and its many shops, restaurants, and cultural institutions that reflect the traditions of those communities.

Among other cuisines, Odessan cuisine stands apart as it encapsulates contemporarily several ethnic food traditions. Notwithstanding the fact that Odessan restaurants are frequently referred to as Russian, especially abroad, they offer a vast assortment of Ukrainian, Jewish, Georgian, Greek, and other culinary specialties alongside Russian dishes. Some of the most renowned typical Odessan dishes, such as the eggplant spread or several types of fish cooked in Odessan style, survive in immigrant communities, as a reminder of the restaurant or the restaurateur’s origins, although it seems that, at least in the case of restaurant Volna in Brighton Beach, other dishes, such as Russian pelmeni or Georgian shashlyk (shish kebab), prevail, likely due to the fact that they are more familiar to the local clientele. Conversely, in Odessa itself, the cult of local culinary traditions seems to be alive and cherished, as we can deduct from the popularity of chefs like Savely Libkin and Lara Katsova, and restaurants like Dacha, where apparently simple Odessan cuisine is reinvented and upgraded to a casual chic dining experience without losing its authenticity.

-

Funding information: Open Access funded by Helsinki University Library.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Works Cited

Apostol-Rabinovich, Rivka. Odessa shutit. Ot Deribasovskoy do Privoza imeem skazat’ paru slov! [Joking Odessa. From Deribasovskaya to Privoz we have a couple of words to say!]. Alistorus, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Author number 6. “Mini saga o Privoze” [A Mini Saga about Privoz]. Odesskiy Forum [Odessan Forum], 25 August 2010. forumodua.com/showthread.php?t=565860.Suche in Google Scholar

Author unkown. “Odessa kulinarnaya. Gid po yede ot kotoroy begut slyuni i drozhat koleni” [Culinary Odessa. A Guide to the food that makes your mouth water and your knees tremble]. Moya Odessa [My Odessa], 11 August 2019. myod.info/odessa-kulinarnaya-gid- po-ede-ot-kotoroj-begut-slyuni-i-drozhat-koleni.Suche in Google Scholar

Author unknown. “Odessa na voyennom polozhenii, den’ 112-i: sho pochyom”. [Odessa during wartime, 112th day: how much is everything]. Odesskaya zhizn’. [Odessan life], 15 June 2022. odessa-na-voennom-polozhenii-den-112-j-sho-pochem.Suche in Google Scholar

Azar, Kristen M. J., et al. “Festival Foods in the Immigrant Diet.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, vol. 15, no. 5, 2013, pp. 953–960.10.1007/s10903-012-9705-4Suche in Google Scholar

Birstein, Alexander. “Forshcmak.” Proza.ru. 2015. proza.ru/2015/11/29/1164.Suche in Google Scholar

Bogoslovsky, Nikita and Vladimir Agatov. Shalandy, polnyye kefali… [Chaland boats full of mullet…], 1943. [Song].Suche in Google Scholar

Cafe Volna. www.facebook.com/CafeVolnaBrooklyn/about.Suche in Google Scholar

Conn, Phyllis. “The Dual Roles of Brighton Beach. A Local and Global Community.” The World in Brooklyn: Gentrification, Immigration, and EthnicPolitics in a Global City, edited by Judith N. DeSena and Timothy Shortell, Lexington Books, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Cook, Ian and Philip Crang. “The World on a Plate: Culinary Culture, Displacement and Geographical Knowledges.” Journal of Material Culture, vol. 1, no. 2, 1996, pp. 131–153. doi: 10.1177/135918359600100201.Suche in Google Scholar

Counihan, Carole and Penny Van Esterik. (Eds.). Food and Culture: A Reader. Routledge, 2012.10.4324/9780203079751Suche in Google Scholar

Cutter, Robert J. “Gastropoetics in the Jian’an Period: Food and Memory in Early Medieval China.” Early Medieval China, vol. 24, 2018, pp. 1–23. doi: 10.1080/15299104.2018.1493815.Suche in Google Scholar

Diaz, Christina J. and Peter D. Ore. “Landscapes of Appropriation and Assimilation: The Impact of Immigrant-Origin Populations on U.S. Cuisine.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 48, no. 5, 2020, pp. 1152–1176. doi: 10.1080/1369183x.2020.1811653.Suche in Google Scholar

Diner, Hasia R. Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration. Harvard University Press, 2001.Suche in Google Scholar

Doroshevich, Vlas. Odessa, odessity i odessitki. Felietony. Vospominaniya o V.M. Dorosheviche [Odessa, Odessan men and Odessan women. Feuilletons. Remembering V.M. Doroshevich], edited by Galina Zakipnaya and Evgeny Golubovsky. Plaske, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

Gabaccia, Donna R. We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans. Harvard University Press, 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

García, Matt, et al. Food Across Borders. Rutgers University Press, 2017.10.2307/j.ctt1trkkjkSuche in Google Scholar

Gaidai, Leonid. Na Deribasovskoy Horoshaya Pogoda ili na Brayton-Bich opyat’ Idut Dozhdi [The Weather is Good on Deribasovskaya or It is Raining Again on Brighton Beach][Film]. Mosfilm, 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

Gitelman, Zvi. The New Jewish Diaspora: Russian-Speaking Immigrants in the United States, Israel, and Germany. Rutgers University Press, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Gray, James. Little Odessa [Film]. Fine Line Features, 1994.Suche in Google Scholar

Grenoble, Lenore A. “The Sociolinguistics of Variation in Odessan Russian.” A Convenient Territory”: Russian Literature at the Edge of Modernity. Essays in Honor of Barry Sherr, Bloomington, Slavica Publishers, 2015, pp. 337–354.Suche in Google Scholar

Grenoble, Lenore A. and Jessica Kantarovich. Reconstructing Non-Standard Languages a Socially-Anchhored Approach. John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2022.10.1075/impact.52Suche in Google Scholar

Gubar, Oleg. “Privoz.” Vikna-Odessa.viknaodessa.od.ua/?Gubar06.Suche in Google Scholar

Fialkova, Larisa, and Yelenevskaya, Maria. “Yevrei byvshego SSSR za rubezhom.” [Jews from the Former Soviet Union Abroad]. Yevrei. Seriya ‘Narody i kul’tury’. [Jews. Series ‘Peoples and cultures’.], edited by T. Emelianenko and E. Nosenko, Series editor V. Tishkov, Nauka Publishers, 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

Frankel, Edith R. Old Lives and New: Soviet Immigrants in Israel and America. Hamilton Books, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Herlihy, Patricia. Odessa: a history 1794 – 1914. Harvard University Press, 1986.Suche in Google Scholar

Highrmore, Ben. “Migrant Cuisine, Critical Regionalism and Gastropoetics.” Cultural Studies Review, vol. 19, no. 1, 2013, pp. 99–116. doi: 10.5130/csr.v19i1.3077.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffman, Betty. Jewish Hearts. A Study of Dynamic Ethnicity in the United States and the Soviet Union. State University of New York Press, 2001.10.1353/book10759Suche in Google Scholar

Isurin, Ludmila. Russian Diaspora: Culture, Identity, and Language Change. De Gruyter Mouton, 2011.10.1515/9781934078457Suche in Google Scholar

Ivanov, Vladimir. “Kak rodilsya befstroganof” [How Beef Stroganoff Was Born. Istoriya, 15 January 2018. histrf.ru/biblioteka/b/kak-rodilsia-biefstroghanov.Suche in Google Scholar

Kabanen, Inna. “Odesskiy yazyk – bol’she mifa ili real’nosti?” [Odessan language – More myth or reality?]. Slavica Helsingiensia, vol. 40, 2010. https://blogs.helsinki.fi/slavica-helsingiensia/files/2019/11/19-sh40.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Kabanen, Inna. “Odessan Courtyard as a Symbol of Humor and Nostalgia on Russian Television”. Russian Journal of Communication, The Emotional Side of Russian Communication, vol. 13, no. 1, 2021, pp. 62–76. doi: 10.1080/19409419.2021.1887992.Suche in Google Scholar

Kartsev, Roman. Raki po pyat’ rubley [Crayfish for five roubles] [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDM0GNgxPcM.Suche in Google Scholar

Katsova, Lara. “Nastoyashyaya Odesskaya Kuhnya” [The Real Odessan Cuisine]. Gastronom, 20 March 2019. www.gastronom.ru/text/odesskie-rasskazy-1008955.Suche in Google Scholar

Kershen, Anne J. “Food in the British Immigrant Experience.” Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture, vol. 5.2, no. 3, 2014, pp. 201–211.10.1386/cjmc.5.2-3.201_1Suche in Google Scholar

Kliger, Sam. “Russian Jews in America: Status, Identity and Integration.” Russian-speaking Jewry in Global Perspective: Assimilation, Integration and Community-building (Conference proceedings), Bar Ilan University, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

Laudan, Rachel. Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History. University of California Press, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

Libkin, Savva. Moya Odesskaya Kuhnya [My Odessan Cuisine]. Eksmo, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

Libkin, Savva. Odesskoye zastolye ot Privoza do Deribasovskoy [Odessan Feast from Privoz to Deribasovskaya]. Eksmo, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Libkin, Savva. savva-libkin.com/en/about.Suche in Google Scholar

Link, Catherine A. Challenges to Flavour: Influences on the Cultural Identity of Cuisines in the Australian Foodscape. PhD thesis. University of Western Sydney, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Litevsky, Alexander. “Odessa bez pokushat’ ne Odessa” [Odessa without food is not Odessa]. Izbrannoe, 11 June 2016. izbrannoe.com/news/yumor/odessa-bez-pokushat-ne-odessa/.Suche in Google Scholar

Litvinskaya, Alena. Linguistic Landscape of “Little Russia by the Sea,” a Multilingual Community in a Brooklyn Area of New York City (Master’s Thesis), Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2010. http://knowledge.library.iup.edu/etd/1017.Suche in Google Scholar

Mannur, Anita. “Culinary Nostalgia: Authenticity, Nationalism, and Diaspora.” Melus. Food in Multi-Ethnic Literatures, vol. 32, no.4, 2007, pp. 11–31.10.1093/melus/32.4.11Suche in Google Scholar

Markwick, Moira. Eating as a Cultural Performance in Early 21st Century New Zealand: An Exploration of the Relationships between Food and Place. MA thesis. Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

Mechkovskaya, Nina. “Russkij Jazyk v Odesse: Včera, Segodnja, Zavtra” [Russian language in Odessa: yesterday, today, tomorrow]. Russian Linguistics, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 263–281.10.1007/s11185-006-0704-8Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, Bryan. “Sampling The Food In Brooklyn’s ‘Little Odessa’.” The New York Times, 20 July 1983.Suche in Google Scholar

Miyares, Ines M. “Little Odessa”- Brighton Beach, Brooklyn: An Examination of the Former Soviet Refugee Economy in New York City.” Urban Geography, vol. 19, no. 6, 1998, pp. 518–530. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.19.6.518.Suche in Google Scholar

Montanari, Massimo. Food Is Culture. Columbia University Press, 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

Parasecoli, Fabio. “Savoring semiotics. Food in intercultural communication.” Social Semiotics, vol. 21, no. 5, 2011, pp. 645–663. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2011.578803.Suche in Google Scholar

Park, Kendall. “Ethnic Foodscapes: Foreign Cuisines in the United States.” Food, Culture & Society, vol. 20, no. 3, 2017, pp. 365–393.10.1080/15528014.2017.1337390Suche in Google Scholar

Prigarin, Alexander. “Balkanskiye aktsenty” odesskogo privoza: K voprosu ob etnicheskih komponentah v gorodskoy kuchne [‘Balkan accents’ of Odessan privoz: The question of ethnic components in the urban cuisine]. Traditsionnaya kul’tura [Traditional culture], vol. 4, no. 60, 2015, pp. 32–40.Suche in Google Scholar

Polese, Abel. “The Guest at the Dining Table: Economic Transitions and the Reshaping of Hospitality – Reflections from Batumi and Odessa.” Anthropology of East Europe Review, vol. 27, no. 1, 2009, pp. 76–87.Suche in Google Scholar

Polese, Abel and Alexander Prigarin. “On the Persistence of Bazaars in the Newly Capitalist World: Reflections from Odessa.” Anthropology of East Europe Review, vol. 31, no. 1, 2013, pp. 110–136.Suche in Google Scholar

Restaurant Dacha. Menu. savva-libkin.com/files/shares/200822_Dacha_total_ENG.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Restaurant Dacha. www.facebook.com/Dacha.Restaurant.Suche in Google Scholar

Richardson, Tanya. Kaleidoscopic Odessa. History and Place in Contemporary Ukraine. University of Toronto Press, 2008.10.3138/9781442688438Suche in Google Scholar

Roy, Parama. “Reading Communities and Culinary Communities: The Gastropoetics of the South Asian Diaspora.” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique, vol. 10, no. 2, 2002, pp. 471–502.10.1215/10679847-10-2-471Suche in Google Scholar

Russkaya Reklama. Restorany [Russian Advertisements. Restaurants]. restaurant.rusrek.com/restaurants/get/volna.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Salgado, Maria A. “The Magical Reality of Food in Pablo Neruda’s Odas.” UTSA. colfa.utsa.edu/modern-languages/1art2.Suche in Google Scholar

Shinder, Felix. Dialog na Odesskom Privoze. [A Dialogue at the Odessan Privoz][Video]. #3 ДИAЛOГ HA OДECCКOM ПPИBOЗE. Ypoк oдeccкoй peчи. Фeликc Шиндep Odesa Privoz Felix Shinder.Suche in Google Scholar

Stepanov, Evgeny. Rosijs’ke movlennja Odesy: Monohrafija [Russian speech of Odessa: A Monography], Odesa, Astroprint, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

Strukova, Anna. “Taki da, Brayton-Bich. Shob my tak zhili. Ili luchshe ne nado?” [Take jo, Brighton Beach! May we live like that. Or maybe better not?]. 21 January 2015, Turister. www.tourister.ru/responses/id_11143.Suche in Google Scholar

Tanny, Jarrod. City of Rogues and Schnorrers: Russia's Jews and the Myth of Old Odesa. Indiana University Press, 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

Ursulyak, Sergey. Likvidatsiya [Liquidation] [TV series]. Central Partnership, ‘Ded Moroz’ Studios, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

Yakovleva, Elena. “Frontirnost’ Gastronomicheskih Povsednevnih Praktik” [Frontiers of Everyday Gastronomic Practices], Zhurnal frontirnyh issledovaniy [Journal of Frontier Research], vol. 1, 2018, pp. 7–16.Suche in Google Scholar

Zelinsky, Wilbur. “The Roving Palate: North America’s Ethnic Restaurant Cuisines.” Geoforum, vol. 16, no. 1, 1985, pp. 51–72. doi: 10.1016/0016-7185(85)90006-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhukova, Antonina. “Korol’ rynkov – Odesskiy Privoz” [The King of the Markets – Privoz of Odessa]. Odesskiy. odesskiy.com/ulitsi-v-istorii-odessi/privoz.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhvanetsky, Mikhail. “Ya videl rakov (dlya R. Kartseva).” [I saw some crayfish (for R. Kartsev)]. Sobraniye proizvedeniy v pyati tomah. Tom 3. Vos’midesyatyye [Complete works in five volumes. Volume 3. The Eighties]. odesskiy.com/zhvanetskiy-tom-3/.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhvanetsky, Mikhail. “Odessa. Eda…” [Odessa. Food…]. Novaya Yunost, vol. 155, no. 2, 2020, pp. 4–6.Suche in Google Scholar

Zipperstein, Steven J. The Jews of Odessa. A Cultural History, 1794 – 1881. Stanford University Press, 1985.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity