Abstract

In relation to the major topic of the present volume, this article is intended to provide new methodological and iconographic insights into the cultural adaptation and integration of European iconographic motifs in the medieval western Scandinavian arts and culture, as well as the relations between the iconographic detail and its surrounding texts. At the same time, this article offers a new approach to existing research on the basis of two methodological theories hitherto little investigated in iconographic research: cultural syncretism and interpicturality. In archaeology and media studies, these approaches are used to interpret cultural–historical artefacts that were created for one and then reused in a new context which may alter their meaning. The present article seeks to explain how both meaning and appearance of a single motif change between the vernacular texts it accompanies, and how the working methods of the illuminators differ between manuscripts. As a qualitative example, the investigation will focus on a complex iconographic motif that is found in six Icelandic manuscripts from the fourteenth century, namely the feature of animal heads as extensions on throne seats. Although little studied in the context of manuscripts, this is a motif widely used throughout the Middle Ages and with various secular and religious connotations. In particular, this is linked to the specific narrative roles that iconographic details play in relation to the written text and generally to the physical objects that carry both text and iconography: the manuscripts.

Introduction

The study of iconographic details has a very small place in Scandinavian art-historical research. Yet, these details offer significant insights into the practice of creating new images in medieval iconography and its relation to textual and other iconographic sources of both domestic and international origin. Both domestic and international manuscripts have been scantily investigated in terms of methodological approaches that also respect their cultural–historical backgrounds on the basis of iconographic research. In what ways is the Icelandic illumination practice influenced by the domestic literature that it accompanies? In what way was the iconography influenced by not only imported artefacts but also domestic art-historical sources? As I hope to demonstrate, this article will, on the basis of one iconographic example and with novel use of the cultural–historical and archaeological method commonly known as cultural syncretism combined with a method known from media studies termed interpicturality, shed new light on the Icelandic illumination practice in the Middle Ages. As a case study, this article will investigate the Icelandic use of a complex motif from medieval iconography, namely the feature of animal heads as extensions on throne seats. Such extensions are generally known as a feature of the iconography of the Throne of Solomon, the most prominent figure of justice in the Old Testament. From Iceland, six depictions of such throne seats are known that lack a textual or clearly defined cultural–historical basis. Nevertheless, the motif was widely adapted and incorporated into medieval Icelandic manuscript production.

The reuse of iconographical details in medieval Iceland is generally linked to previous usage, iconographic patterns, as well as to vernacular literature. Yet, first and foremost, the functions of such images appear to be tied to their cultural frames (Baxandall). These frames consist of cultural circumstances that may be categorised into two types that primarily relate to the content and usage of a medieval image (Belting, 9): Either as personal, somewhat text-unrelated imago, or as historia, which are based on a plethora of texts. These can be read either directly, in syntactic ways connected to the manuscript text (Harrison), or indirectly in terms of pictorial exegesis of medieval theology and/or philosophy in which they appear (Carruthers). Even so, looking for close semiotic implications in connection with iconographic images (Bal and Bryson) would be misleading in the cases to be discussed here. This is due to the formal mechanisms of mimesis that such a method often inherits (Schapiro, 274). Similarly, due to their often-unclear textual basis, approaches stemming from the famous iconology method, initially established by art historian Erwin Panofsky, are not sufficient to detect the methods of work used by Icelandic illuminators. In the vein of the iconic turn (Mitchell), interpicturality presents a recent art–historical approach, but it does not constitute one single method (Zuschlag, 90), which is able to identify syncretistic phenomena in relation to the ways in which they were initially produced. In its essence, interpicturality refers to images or forms created for one context and then reused in a new context which may alter the meaning of the images. Such image-to-image relations are the “intertextuality of visual media,” while the type of association can vary (von Rosen, 161–2).

As regards the Icelandic examples, it is appropriate to interpret their iconographic content not only in terms of artistic use but also its cultural embedding. Merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions of the motif appears in the north throughout the Middle Ages, and this process indicates places and times where distinct aspects of different cultures blend together. Accordingly, wider cultural–historical contexts of religious medieval Scandinavian art need to be considered and integrated into the study of its iconographic research. In this regard, a particularly relevant approach appears to be the methods established in religious and cultural syncretism, which investigate the adaptation and combination of forms of belief and practice and their implementation in material culture. Syncretism in the humanities is first and foremost attached to the disciplines of History of Religion and Anthropology, where a number of suitable approaches have been established over the last few decades (Leopold and Sinding Jensen, 48–58), and is now also commonly used in the field of Old Norse Religion (Ahn). Related methodologies have quickly been adapted and expanded to other fields of Old Norse research, such as literature and poetry (Amory, 251–3), with a particular focus on mythological topics (Beck). With regard to medieval Scandinavian art, important case studies have been conducted by the archaeologist and ethnologist Gräsland (“Runic Monuments,” “Stil och motiv”) on the protracted Christianisation of Scandinavia, and with a focus on Swedish runestones from the eleventh and twelfth centuries. From outside of Scandinavia, the iconic British Gosforth cross, dated to the early tenth century, is one of the most striking northern European examples of religious and cultural syncretism. Its visual content and textual background powerfully demonstrate the fluid exchange of northern European iconographic models at the time (Bailey, 18–22). With regard to medieval Scandinavian iconography, a famous example is the Underliggare figure, which forms part of the Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae iconography of the Norwegian king and saint Óláfr Haraldsson (995–1030). This iconography first appears in the thirteenth century and became particularly popular during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (Stang, 43–6; Gullbekk, 129–31; Ekroll, 163). It is also found in two examples from Iceland, the oldest dating to the first half of the fourteenth century and found in the manuscript AM 68 fol. (Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum), which fittingly contains a redaction of the vernacular Óláfs saga helga, among other texts. The iconography is part of a miniature on f. 1r that depicts the enthroned and crowned saint with his attribute, the axe, and the imperial orb. Beneath his feet, a human figure is seen to convey a praying gesture towards the king above. Other versions of the image show the Underliggare as a half-beast whose body resembles that of a lion or a dragon while its head is depicted as a crowned human head. Interpretations of the figure on which the saint steps range from it being the pre-baptised, pagan king whom the later saint has overcome (Fett, 58), to evil forces that the king has besieged with his martyrdom (Norseng), to potentially legendary references in texts on the saint (Lidén). Although the motif itself is inspired by images of St Margaret or St Michael, the Underliggare figure is nowhere explicitly mentioned in the medieval text corpus. Even so, the inclusion of the image in both religious and iconographic traditions displays particularly well the complex and tight bonds between Old Norse religious and literary cultures in the Middle Ages.

The Throne of Solomon and its Cultural Context in the Middle Ages

Based on both religious and more general culture–historical developments, the depictions of throne benches in six Icelandic illuminated manuscripts represent examples of these complex syncretistic developments in medieval Scandinavia. Although little studied in the context of manuscripts, depictions of thrones with low arms and back-rests have a long tradition since this is a motif widely used throughout the Middle Ages and with various secular and religious connotations. In the following, a selection of sources relevant to the purposes of this article is presented and related to the research question laid out above.

Thrones with low arms and back-rests have been widely used since Babylonian times and Antiquity and were integrated into European Christian iconography at an early stage. Continuously changing over the centuries, x-legged wooden curule seats (sellae curules, sg. sella curulis) and stone-made throne benches (solia, sg. solium) were modified to include extensions consisting of animal heads and claws placed on the base of the armrests (Wanscher). The Christian Occident especially adopted throne depictions from the Late Roman emperors, and similar references were added. In Christian iconography, such extensions are known to refer to the Throne of Solomon, the most prominent figure representing iustitia in the Old Testament. His throne is described in I Kings 10, 18–20, where two named lions stand beside his throne together with a further 12 lions arranged on 6 steps leading up to the throne. According to Maurus (780–856) (Patrologia Latina, 197), the first 2 lions are representations of the fathers of the Old and New Testament, while the other 12 represent the apostles or, alternatively, the tribes of Judah (Kärber, 21; Bloch, 117). From a good four centuries earlier, the oldest visual references of the widely dispersed iconography of Christ in Majesty are known, showing the Son of God in a ruling pose and with a blessing gesture, seated on a throne. Directly related to Revelation 5,5, where Christ is manifested as princeps omnium bestiarum, numerous forms of lion heads and claws were added to the throne benches of the iconographic image a few centuries later, around the time of Rabanus Maurus, to further strengthen the divine nature of the enthroned Christ. The relation of Christ to lions was already well established by that time, mainly due to the widely dispersed fifth-century moral text Physiologus and its medieval successor, the Bestiaries compendium.

Christian adaptations of the Throne of Solomon for the Holy Virgin appear equally early. Since the First Council of Ephesus in 431, also Mary appears in Christian art as the enthroned Mother of God. The possibly first textual reference appears much later, in the twelfth-century Sermon of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin by Nicholas of Clairvaux (1090–1153) (Ragusa, 100). In this sermon, Mary is described as sitting on the sedes sapientiae, the seat of wisdom, which is an amalgamation of the divine wisdom of God and the human wisdom of King Solomon. Consequently, the sedes sapientiae was further developed with visual ecclesiastical exegeses such as the four cardinal virtues, frequently in picture-bible manuscripts (Bible moralisée) from the thirteenth century (Laag, 304–5; Wormald, 534–5). Here, the two lions became representations of the Archangel Gabriel and John the Evangelist, which act as visual symbols of the mind and body of the Holy Virgin (Kärber, 21). To my knowledge, from medieval Scandinavia, the oldest example of a sedes sapientiae is the enthroned Virgin from the western Norwegian stave church at Urnes (Bergen, Universitetsmuseet – Kulturhistorisk Museum, MA 46) from 1150 to 1200 (Figure 1). Although it cannot be determined with certainty whether the statue was produced in Scandinavia or imported from another art centre in Europe (Kroesen and Kuhn, 41), it shows Mary in a Nordic fashion, with the four animal heads attached to her curule seat and each head looking upwards.

MA 0046 (Madonna from Urnes). 1150–1200. Bergen, Universitetsmuseet – Kulturhistorisk Museum. Image: Adnan Icagic. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

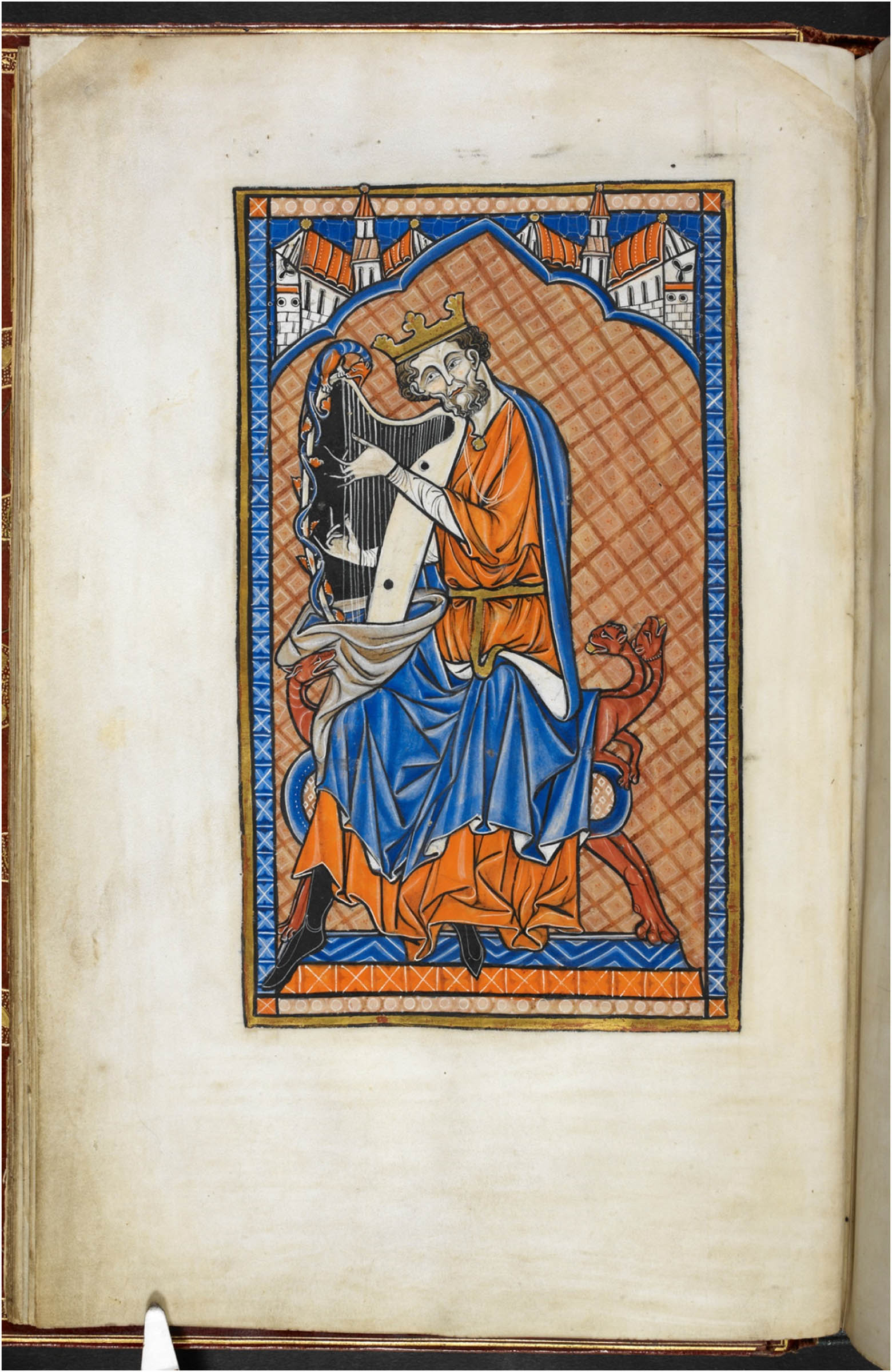

During the Carolingian and Ottonian periods, the Throne of Solomon motif was frequently combined with royal attributes, such as sceptre, crown, sword, parchment, and scroll, as well as more individual attributes (Kärber, 15–24). At the same time, the monumental, Christological lion heads were painted in a more fragile fashion, such as in the famous coronation miniature of the Gospels of Emperor Otto III (980–1002) (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 4453) from c. 1000 (Blum and List, 114). Accordingly, the iconography of throne seats and benches comprises about a 1,000-year-old history including a diverse and complex omnium–gatherum of ecclesiastical and secular symbolism during the Late Antiquity and the Early and High Middle Ages. With the larger greater production of Gothic manuscript painting during the thirteenth century, throne benches with attached lion heads and claws were painted in less standardised ways. Particularly in the widely used iconography of King David playing the harp, additions made to the throne are no longer restricted to lion heads and claws, but now appear also as beast or dog heads, with respective claws. In addition, the creatures are sometimes represented as interacting with King David (Rensch, 53–4). The most striking northern European example is found in the Oxford-produced Oscott Psalter (London, British Library, Add MS 50000 and Add MS 54215) from c. 1265–1270 (Early Gothic Manuscripts, 136). A miniature on f. 15v shows David playing the harp (Figure 2). While the motif of King David playing the harp is well-known from all over medieval Europe, as he is widely used in manuscript illumination as the primary example for rulers (Steger, 259), the lively beast heads on the curule seat, and a beast figure attached to the harp on the left, disturb the image. Although this could be a visual reading of I Samuel 16, 24–23, where King David is described as playing the harp to soothe the mind of the nightmare-ridden Saul – the beasts being a visual reference to the nightmares – no unequivocal textual identification of the beast heads is discernible. The motif of the beast-adorned harp is known from slightly younger paintings, too, such as in a copy of Peter Lombard’s commentary on the Psalms in MS VII.A.A.8 on f. 2r (Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale) from c. 1275–1325, where a French miniaturist added an initial to the manuscript in the early fourteenth century (Improta). A further example is found as a marginal painting on f. 245r in the Maastricht Hours (London, British Library, Stowe MS 17) from c. 1300 to 1325 (Gothic Manuscripts, 200), produced near Liège. In addition, and in relation to both King David and secular rulers, there are also examples of the motif of the seated King David playing his harp with no animal heads attached to the throne bench, but featuring floral ornamentations with trifoliate acanthus leaves instead or with involuted lilies and other flower leaves adorning the sedes sapientiae.

Add MS 50000 (Oscott Psalter), f. 15v: David playing the harp. 1265–1270. London, British Library. Image: British Library. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Icelandic Illuminations

Similar to these examples from the iconography of King David playing the harp, the use of throne benches in medieval Icelandic book paintings varied and was likely based on several iconographic traditions. The corpus of these medieval Icelandic illuminations consists of five historiated initials and one miniature; a selection that can only be considered qualitatively, but which nevertheless covers a fairly wide selection of the vernacular prose literature of medieval Iceland, including laws (Jónsbók), annotated vernacular translations of parts of the Old Testament (Stjórn), translated vitae of saints (Heilagra manna sögur), sagas about Norse kings (konunga sögur) and a pseudo-historical work about the history of Alexander the Great (Alexanders saga). The entire corpus of medieval Icelandic book painting consists of about 50–60 manuscripts from these and other genres of vernacular Scandinavian literature from the Middle Ages (Hermannsson, 16–32). Although the illuminations are found in manuscripts dated to c. 1200–1650 and beyond, many of these are from the fourteenth century, the “Golden Age” of Icelandic book production (Karlsson, 188–205), which also comprises the largest amount of medieval Icelandic manuscripts (Gunnlaugsson, “Manuscripts,” 249). Nevertheless, few of the illuminated manuscripts have been written and/or illuminated by craftsmen known by name. In most cases, what we know of the craftsmen’s regional affiliations and potential relation to manuscript groups affiliated with (mainly) monastic workshops is largely based on palaeographic data (Gunnlaugsson, “Voru scriptoria,” 183–93). It is because of this that an investigation into the sharing and the individual use of iconographic motifs such as the Throne of Salomon can help us gather more information about the production of some of the oldest bearers of medieval Scandinavian literature.

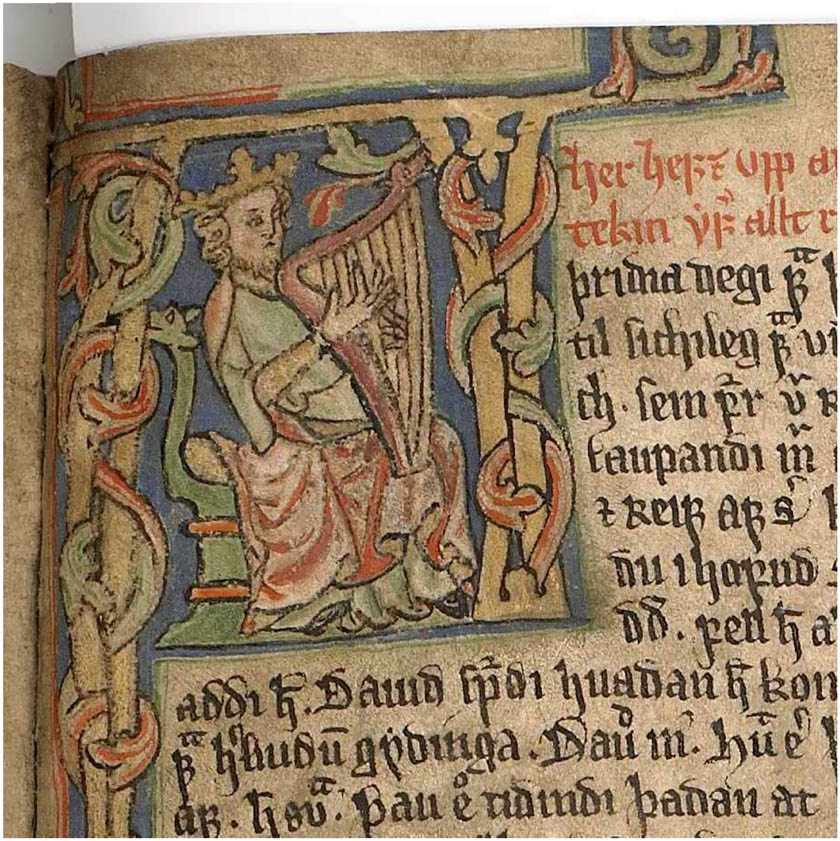

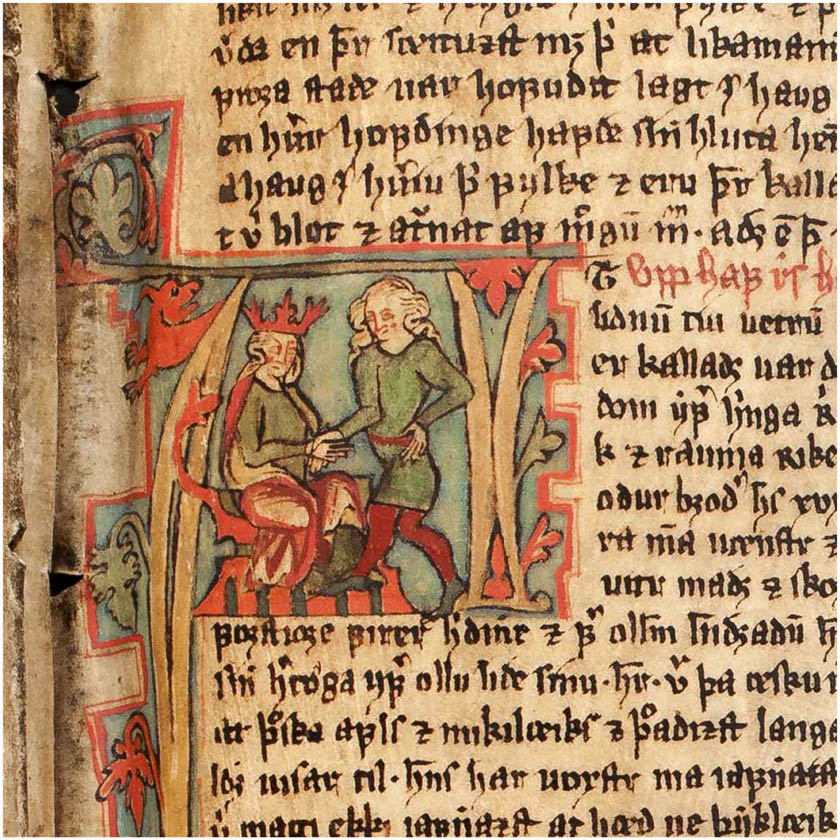

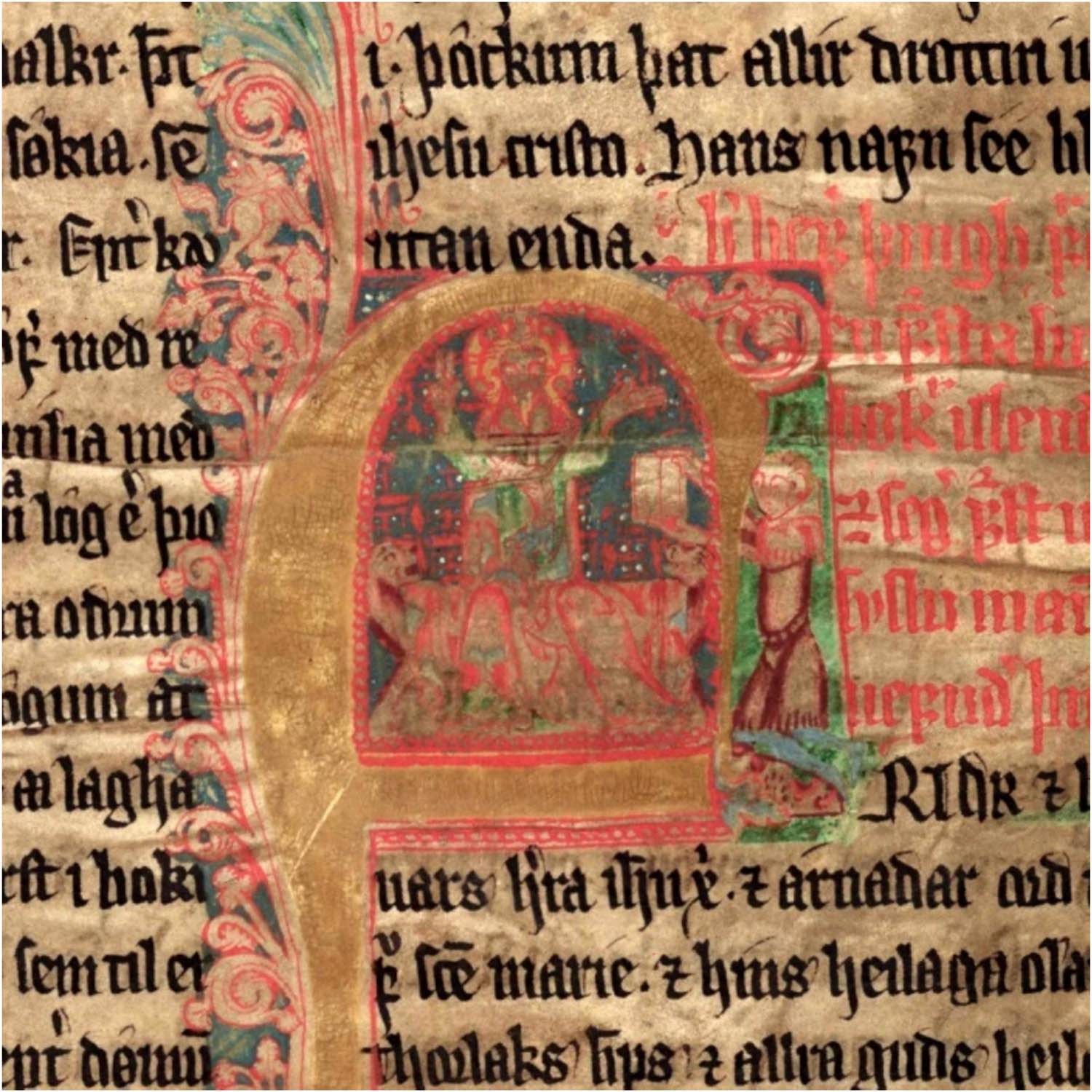

Typical of Icelandic book painting, all depictions of the Throne of Salomon to be discussed below are painted in a hybrid form of early and high Gothic figural styles, combined with Romanesque ornamental models (Björn Th. Björnsson, 30–1). In four cases, the Throne of Salomon is found in two manuscripts illuminated and (partly) written by the cleric Magnús Þórhallsson. Apart from his artistic and scribal works, we have little historical information about him (Drechsler, Illuminated Manuscript Production, 92–7). But we do know that, during the last few decades of the fourteenth century, he was part of the Augustinian house of canons regular at Helgafell in western Iceland, to which a group of contemporaneously produced vernacular manuscripts is ascribed (Karlsson, “Introduction,” 19–21; Halldórsson, Helgafellsbækur). The earliest of the two manuscripts that contain related book paintings by Magnús, AM 226 fol. (Copenhagen, Den Arnamagnæanske Samling) was produced in two stages at Helgafell in c. 1350–1370. It contains a vernacular account of the history of the world from Genesis until the beginning of the New Testament, and it was most likely produced for teaching purposes (Helgadóttir, cc). AM 226 fol. contains an annotated vernacular translation of parts of the Old Testament known as Stjórn (ff. 1v–110r), as well as the pseudo-historical Rómverja sögur (ff. 110r–129r), Alexanders saga (ff. 129r–146v) and Gyðinga saga (ff. 146v–158r). The manuscript features three main initials that depict throne benches with particularly elongated animal heads, two of which are part of Stjórn: On f. 79rb21–29, at the beginning of I Samuel 1, a young, enthroned warrior is depicted as armed (Figure 3). According to the rubric, the figure may be Elkanah, although it is equally likely that he is King Saul prior to his coronation. Alongside the fortified fashion of the seated ruler and the somewhat bulky appearances of the throne extensions, the military leadership of Saul is clearly described in I Samuel 1,9 and I Samuel 1,11, which is found a few leaves later, on f. 83v. Similarly based on the methodological background of the interpicturality, parts of the image belong to a workshop-internal stock image, which comprises the placement, weapon, and overall gesture of the seated ruler (Drechsler, Illuminated Manuscript Production, 230–1). However, the bulky appearance of the long-necked animal heads flanking the seated warrior in this illumination appears unique and may refer to inspiration drawn from elsewhere. On the other hand, it may be read in relation to the two other examples of the same iconographic detail in the same manuscript. The next example in AM 226 fol. is found on f. 88r, at the beginning of II Samuel 1. This depicts the largely standard iconography of King David playing the harp (Figure 4). Apart from the unusually long neck and clearly identifiable ears on the throne extensions, this image is undoubtedly inspired by earlier models, such as the example from the Oscott Psalter. The final example of the motif in AM 226 fol. is found on f. 129r (Figure 5), at the beginning of Alexanders saga, a vernacular redaction of the twelfth-century Alexandreis by Walter of Châtillon on the life and deeds of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) (Würth, 316–24). According to the rubric and the name, it introduces in the main text, the initial depicts the enthroned Persian King Darius III (380–330 BC), who is one of the main enemies of Alexander the Great in the saga text. The image is a combination of several stock images, among others that were also used for the Elkanah/King Saul initial on f. 79r. Yet, the bulky appearance of the animal heads in that initial is not repeated in the King Darius III initial: The more filigree-like animal heads on the King Darius III initial mirror the ones found in the King David initial on f. 88r. Despite the peaceful appearance of King David in that initial, on f. 88ra4, his actions are referred to as those of a víkingr, meaning that he was pirate-like in battle actions. King Darius III, similarly, is described in the saga as being a fairly cruel ruler with strict taxes to be paid to him by his tributary kings. He is depicted as holding an unusual form of a sceptre (a palm leaf fan) in his right hand while the other hand lies open before his stomach. The sceptre may refer to Esther 4:11, a section in the Old Testament where the presence of a golden sceptre indicates being allowed to speak to a king (in that case the son of King Darius III, King Ahasuerus). Yet, apart from constituting a general reference to royal and ecclesiastical insignia (Flemming, 365; Voretzsch, 194), it remains unclear what exactly the sceptre means in this illumination, as well as the open hand in which the medieval reader would otherwise expect to find the imperial orb. Contentwise, it may possibly indicate the weakness of King Darius III towards Alexander the Great, which is described in later sections of the saga. Either way, all three illuminations in AM 226 fol. – taking these to depict King Saul, King David and Darius III – portray military leaders in Stjórn and Alexanders saga, respectively, and serve different moral functions for the reader. Accordingly, the use of the animal heads attached to the throne benches may serve these functions by their mere presence in the images. Furthermore, the clothing of the depicted rulers is similar, consisting of a green or blue tunic, a red toga and black shoes. Accordingly, the animal-head references in all three images may hint at a chronological translation of pre-Christian rulers, which goes well with the educational purposes of the manuscript and strengthens, even more, the cultural-syncretic intention behind the design of these initials.

AM 226 fol., f. 79r: Stjórn. 1350–1370. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum. Image: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

AM 226 fol., f. 88r: Stjórn. 1350–1370. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum. Image: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

AM 226 fol., f. 129r: Alexanders saga. 1350–1370. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum. Image: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

A somewhat more generalised use of the throne extension-motif is found in one medium-sized initial in the other manuscript illuminated (and partially written) by Magnús; this is the impressive kings’ saga compendium Flateyjarbók (Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum, GKS 1005 fol.). Flateyjarbók was written and illuminated in 1387–1394 for its client Jón Hákonarson (1350–1402/16), either completely or partly at his estate of Víðidalstunga in northern Iceland (Halldórsson, Á afmæli). This particularly large manuscript (c. 420 mm × 290 mm) primarily contains sagas about Norwegian kings, but also a large number of other vernacular texts of various sorts (Kålund, 10–16). In addition to the immense and complex textual content, Flateyjarbók contains unique, text-related illuminations (DuBois; Drechsler, Ikonographie). However, unlike the examples from AM 226 fol., the single example in Flateyjarbók hardly contains any special features. The example is found at the beginning of Haralds þáttr hárfagra on f. 76r, which is a short story relating the early life of the first king of all Norway, Haraldr “Fairhair” Hálfdanarson (c. 850–931/932) (Figure 6). The medium-sized initial depicts the young king, clad in a short tunic, as he receives the kingdom from his father, the petty king Hálfdanr “the Black” (810–860) (Kristjánsson, 93), who is clad in a fashion similar to the three rulers in AM 226 fol. described above. The iconographic model for the scene is most likely an English motif used to indicate that the figure who is walking is crossing a moral border (Drechsler, “Ikonographie,” 254–8), while the floral ornamentation attached to the throne mirrors the Mariological floral element mentioned above. Yet, unlike the initials in AM 226 fol., the iconographic motif of the walking figure may serve a new purpose in Flateyjarbók: the young king is the first in Norwegian history to unite the whole kingdom under one rule and thus breaks with previous traditions. Yet, the use of the floral element on the depicted throne bench likely remains purely ornamental.

GKS 1005 fol. (Flateyjarbók), f. 76r: Haralds þáttr hárfagra. 1387–1394. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum. Image: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

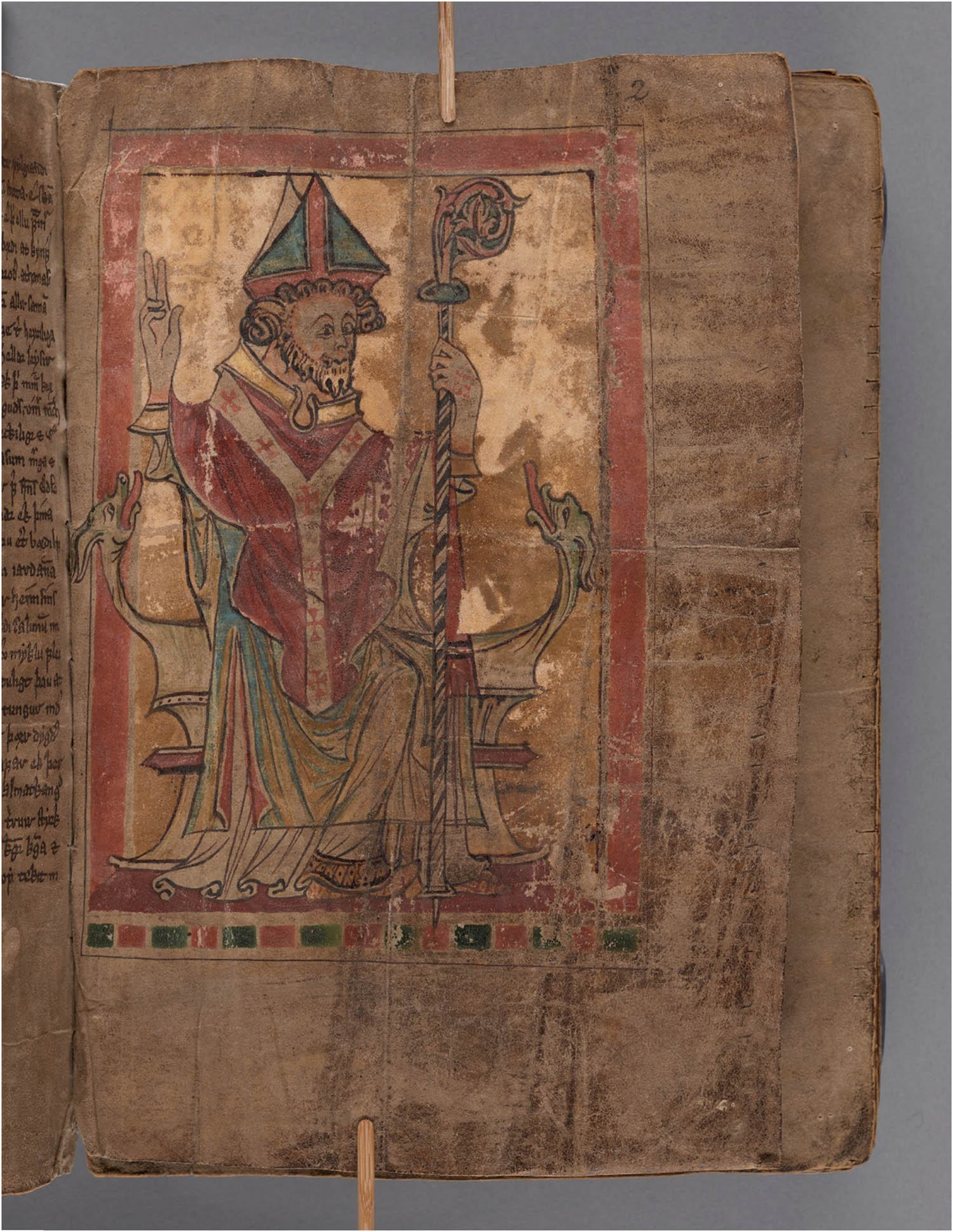

The next example is found in the codex Helgastaðabók (Stockholm, Kungliga Biblioteket, Isl. perg. 4:o 16), which was written by a single scribe in c. 1375–1400 in northern Iceland, perhaps at or near the Benedictine nunnery at Reynistaður (Karlsson, Uppruni, 75). Helgastaðabók contains solely a redaction of Nikuláss saga erkibyskups, which is a vernacular adaptation of the vita of the fourth-century saint Archbishop Nicholas of Myra (270–334) – a martyr who was widely praised in medieval Iceland (Tómasson, 25–7). Similar to Flateyjarbók, Helgastaðabók features initials with largely unique, text-related content, as well as altogether three miniatures. The opening miniature, on f. 2r, depicts the enthroned Archbishop in great detail (Figure 7). In accordance with his profession, Nicholas wears a stola and a dalmatica with a pallium on which crosses are depicted. In addition, he wears a mitre and holds a crosier in his left hand, while his right hand blesses the viewer. He sits on a broad throne bench where the outer parts feature extensions with animal heads and long necks, extended tongues and droopy ears. They face the seated saint asymmetrically (Jónsdóttir, 91–3). Both the size of the animal heads and the long tongues are peculiar, in addition to the long necks. No textual reference is evident, although the lack of a halo above Nicholas may indicate a scene prior to his martyrdom. The intention in this miniature may be similar to the three initials in AM 226 fol., which was apparently to strengthen the educational purposes of the manuscript. At the same time, the iconographical closeness to the example from the previously mentioned English Oscott Psalter indicates that no textual, but a cultural–syncretic intention, has contributed to the unusual depiction. The miniature, then, may display a moral exegesis of the text: the animal heads may mirror the obstacles which the later saint has to overcome during his encounters with the citizens of Myra.

Isl. perg. 4:o 16 (Helgastaðabók), f. 2r: St Nicholas. 1375–1400. Stockholm, Kungliga biblioteket. Image: Kungliga biblioteket. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

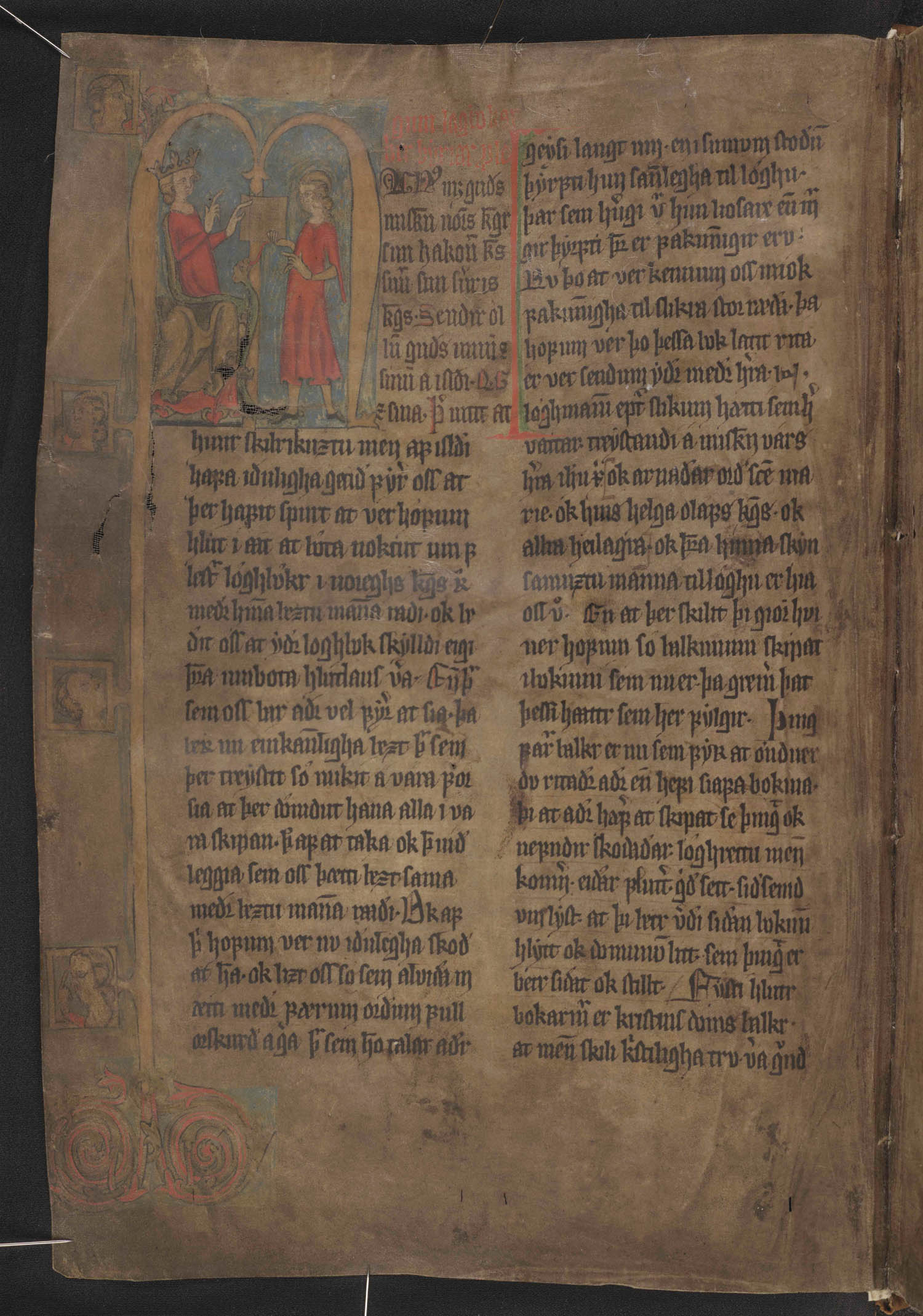

Compared to the previous illuminations, the final example is more complex. It is found in the two law manuscripts Svalbarðsbók (AM 343 fol.), from c. 1330–1340, and Belgsdalsbók (AM 347 fol.), from c. 1350–1370 (both stored at Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum). The two codices contain, among other texts, the Icelandic law code Jónsbók, which was commissioned by the Norwegian King Magnús “the Law-Mender”’ Hákonarson (1238–1280) and introduced in 1281. Some 20 years earlier, in 1262–1264, the North Atlantic island became a tributary land of Norway. Accordingly, both the textual and the iconographic contents of Icelandic and Norwegian manuscripts from the fourteenth century share a number of similarities. The two illuminations in question, in the Icelandic codices of Svalbarðsbók and Belgsdalsbók, are undoubtedly based on the same model, although stylistic variations are found (Liepe, 64). For the present article, the older initial in Svalbarðsbók will be examined. It is found on f. 1v, at the start of Bréf Magnúss konungs, which acts as a prologue to the law (Figure 8). The scene is divided up by the shape of the initial letter (M). On the left, an enthroned and crowned king is depicted wearing a tunic and a toga. He leans towards the right and holds up in his left hand a parchment that contains a wet-ruled, two-columned text; the other hand conveys a demanding gesture. On the right, a figure facing the king holds the central codex in his right hand and shows a pointing gesture with his left. This figure wears less embellished clothing that consists of a long tunic and sandals. According to Bréf Magnúss konungs, which was instructed by King Magnús and addressed to the Icelandic people, the enthroned figure is meant to be the king himself. The second figure is likely the Icelandic judge Jón Einarsson (d. 1306), who, according to Bréf Magnúss konungs, brought the law to Iceland in 1280 and shortly after lent his name to the code: Jónsbók. Clearly identifiable on the throne bench are two extensions: On the right side of the bench, an extension of the armrest consists of an animal head with small ears. This animal head is depicted with a long tongue that stretches up to the centrally placed parchment. In addition, a claw extension at the base of the throne is visible. Like the animal head, this extension reaches out into the left part of the initial letter, but Jón places his left foot on top of it. On the left, the main initial extends into the lower margin. On that extension, small angled framed medallions are visible, showing four framed imago clipeata, half-profiled faces that look to the outside and inside of the folio leaf. In connection with other features of the initial, the use of the motif may indicate a moral reply to the textual content of Bréf Magnúss konungs. Similar to the example from Flateyjarbók, the symbolic trespassing by Jón may be interpreted as a violation of the royal sphere of power, which is further indicated in the gesture of the king and the animal head with its stretched-out tongue looking towards the receiver of the law. The imagines clipeatae, on the other hand, may depict some of the “very prudent men,” who, according to Bréf Magnúss konungs, contributed to the law code (Jónsbók, 77).

AM 343 fol. (Svalbarðsbók), f. 1v: Bréf Magnúss konungs. 1330–1340. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum. Image: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

In summary, the use of the two major iconographic models of throne benches known from illuminated thirteenth-century European manuscripts – floral extensions and several forms of animal heads – were integrated into and – adhering to the methods of interpicturality – further developed by the iconographic programmes of fourteenth-century Icelandic scriptoria. Similar to the example from the Oscott Psalter, the relations of the initials to the (vernacular) texts in the Nordic manuscripts are symbolic (AM 226 fol., Flateyjarbók), or refer to potential moral exegeses (Helgastaðabók, Svalbarðsbók).

Throne Benches in Medieval Scandinavia

Inspiration for the Icelandic initials may not have come from book painting exclusively. It is very likely that also other visual medias were used in medieval Iceland to produce the illuminations described above. Particularly based on the methodological background of forms of cultural–historical syncretism, the use of other Scandinavian visual art, such as seals and stave church ornamentation is likely to have influenced the way in which the Icelandic illuminations were designed and placed in relation to the text and the overall intended use of the manuscript. Generally, throne benches and curule seats in medieval Scandinavia appear at a much earlier date than the manuscript iconography (Trætteberg, 48–9). The earliest example depicting a curule seat with most of the described features is the (now lost) seal of King Knútr Sveinson (1043–1086) of Denmark from c. 1085 (Benktsson, 195–214). On the seal, the crowned king is shown frontally, holding the imperial orb. Similar to the Ottonian example mentioned above, the curule seat on the seal of King Knútr is shown with short-necked lion heads, as well as lion claws as foot extensions. During the following centuries, depictions of curule seats appear in Norway in large numbers, with the so-called B-seal of King Hákon V Magnússon (1270–1319) as the (likely) initial example (Brinchmann, 12–3). This mirrors similar trends known from France and Germany between the late eleventh and fourteenth centuries (Grandjean, 144). Contemporaneous depictions of throne benches with animal heads are known from the Norwegian clergy too, and a number of seals from the Archdiocese of Niðaróss (now Trondheim) were undoubtedly inspired by similar trends. The earliest example was perhaps the seal of Archbishop Sǫrli (1253–1254), which was most likely made in Trondheim (Kielland, 119, 122). The seal shows the archbishop seated on a throne bench with extensions in the form of lion heads and with lion claws as foot extensions. It is notable that the lion heads have tongues in the form of acanthus leaves. Likely made as direct copies of this seal, it seems to be what that the seals of the next three archbishops were based on: Einarr (1255–1263), Hákon (1265–1267) and Jón “the Red” (1268–1282), although four animal heads are found on the seal of Jón (Fjordholm et al., 43–5).

From medieval Iceland, the iconographic form used on the mainland, with lion heads and claws as short extensions of a throne bench, is known from only two examples. The older is found on f. 2r of a law compendium dated to 1363, the so-called Skarðsbók (Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum, AM 350 fol.) (Figure 9). The illumination in question consists of an altered version of the Throne of Grace with particular text–image relations (Drechsler, “Zur Ikonographie,” 76–80), but the lion heads depicted in this initial follow standard forms known from older examples, such as the ecclesiastical seals mentioned above. The second example is found on the seal of the Norwegian Gottskálk Keneksson, who served as bishop of the northern Icelandic diocese of Hólar in 1442–1457 (Lárusson and Kristjánsson, 76–81). The seal shows the bishop’s namesake, the Frisian martyr Godescalcus (d. 1066) who serves, inter alia, as patron of linguistics and languages. On the seal, the martyr is depicted frontally on a chest-type throne bench, dressed in a long tunic and wearing a nimbus. On both sides of the throne, small extensions of animal heads are visible, facing the outside with gaping mouths and pointed ears. Godescalcus is half turned to the left, holding a codex in his left hand while he writes with his right hand. Obviously, the motif is a depiction of the patronage of the holy man.

AM 350 fol. (Skarðsbók), f. 2r: Jónsbók. 1363. Reykjavík, Stofnun Árna Magnússonar í íslenskum fræðum. Image: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Together with these two Icelandic examples, the number of royal and ecclesiastical seals depicting standardised forms of the motif and dated to the thirteenth century undoubtedly indicate the cultural ties Norway established with other parts of Europe. First and foremost, these ties were channelled through the diplomatic and ecclesiastical networks of the Norwegian King Hákon Hákonarson (1204–1263) and his son, the already mentioned King Magnús Hákonarson. These diplomatic relations are likely to have found their way directly into Icelandic book painting. In one initial in Flateyjarbók, depicting f. 5v King Haraldr “Fairhair” Hálfdanarson as “rex iustus,” it is likely that a seal produced for King Hákon Hákonarson in 1247 was used as a model for the pose of the seated ruler (Drechsler, “Ikonographie,” 235–6). But also generally, the strong interest of King Hákon and his son, King Magnús, in French and English courtly literature, as well as in vernacular law writing, was also clearly contributed to the international character of the text-related Norwegian and Icelandic book painting trends that arose in the early fourteenth century. With this in mind, also the lively animal heads featured in the miniature in the English Oscott Psalter may have been transferred to the North shortly after its production in the late 1260s, since stylistic similarities between the group of illuminators responsible for that psalter and other English works were found in the western Norwegian Kinsarvik altar frontal (Bergen, Kulturhistorisk Museum, MA 10), which was produced around 1275 (Morgan, “Dating,” 36). Influences from English manuscript, glass and panel painting on Norwegian altar frontal and book painting are frequently found in the following decades, until c. 1325 (Morgan, “Dating,” 23–34; Morgan, “Western Norwegian,” 12–21), and in Norwegian and Icelandic book painting throughout the fourteenth century. Yet, historical information on art historical material being sent from Norway to Iceland is scarce. The mid-fourteenth century bishop’s saga Lárentíus saga byskups states that archbishops from Niðaróss sent out letters to both Icelandic dioceses (Sigurðsson, 128), and it is likely that parts of the miniature of St Nicholas in Helgastaðabók was inspired by one such ecclesiastical seal. According to Lárentíus saga byskups (267), a document containing the seal of Archbishop Jǫrundr (1288–1309) was given to the later bishop of Hólar and name-giver of the saga, Laurentius Kálfason (d. 1331), around 1300 and was thus known in the area where Helgastaðabók was produced some 75 years later. The seal of Bishop Laurentius is based on a slightly younger Norwegian seal, namely the seal of Bishop Árni Sigurðsson of Bergen from c. 1309 (Morgan, “Dating,” 27–8). Generally, the (likely) Trondheim-produced seal of Archbishop Jǫrundr includes known insignia, such as a stone throne bench whose armrests are ornamented with lion heads facing outwards (Kielland, 118, 122). Nevertheless, the clothing of the cleric is specific and mirrors the Nicholas miniature: Jǫrundr wears a mitre, a patterned vestment and conveys a blessing gesture with his right hand. Unlike the Icelandic example, however, Jǫrundr is depicted as holding a crosier in his left hand. As mentioned above, the production of Helgastaðabók may have taken place in northern Iceland in the vicinity of Hólar and, given the similarities, it appears likely that the seal was known to the illuminator. However, a miniature depicting two saintly bishops, on f. 1r of the Icelandic bishops’ saga codex Isl. Perg. fol. 5 (Stockholm, Kungliga Biblioteket) from c. 1370, displays a number of similar iconographic features. It is equally likely that the two images refer to first-hand knowledge of clerical endowments since they were most likely produced in ecclesiastical scriptoria at the same time (Drechsler, Illuminated Manuscript Production, 125–26; Jónsdóttir, 210). Yet, the long necks of the animal heads in the Nicholas miniature in Helgastaðabók and in AM 226 fol. are not convincingly explained through the texts they initiate in the manuscripts. On the contrary, their symbolic value arises mainly from the cultural historical and religious syncretism of the medieval Scandinavian cultures that produced them.

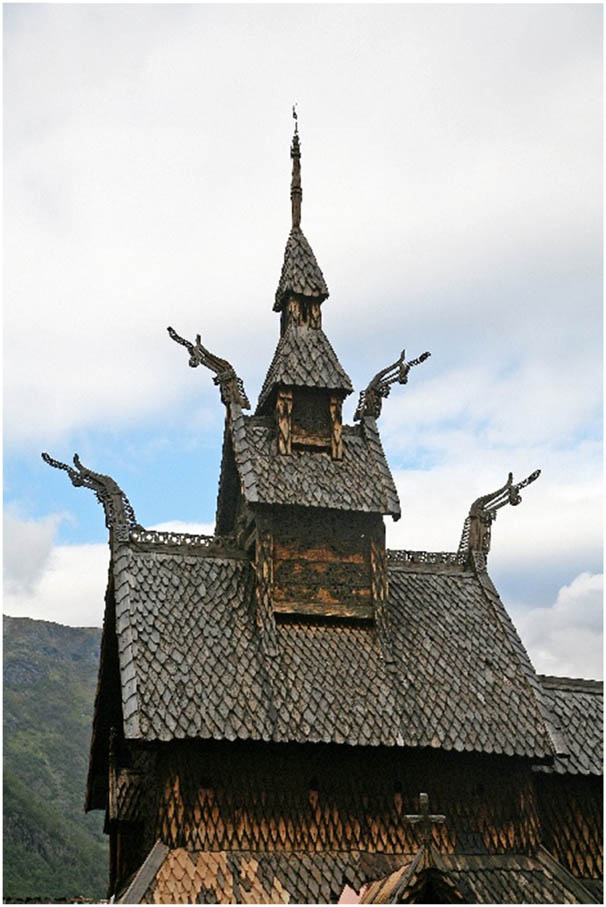

Animal heads with long necks on throne seats have a long tradition and date as far back as the Babylonian Achaemenid Empire. The oldest example is found on coinage depicting Artaxerxes III (who ruled 358–338 BC) as Pharaoh of Egypt, dated c. 343 BC. Although general similarities may be suggested, it is unlikely that the inspiration in Iceland was taken from sources as old as the Artaxerxes III coin. On the contrary, it is more likely that the long necks are remnants of an indigenous Scandinavian tradition. An impulse could have derived from dragon-head sculptures attached to a number of Norwegian stave churches or shrines that show equally long necks and stretched-out tongues in the Germanic Tierstil II, dated c. 570–750, and in its stylistic advancements such as the famous Urnes style, dated c. 1050–1150. Suitable examples may be found on the twelfth-century stave church at Borgund in Lærdal (Figure 10) or on the thirteenth-century shrine from the stave church at Hedalen in Valdres (Figure 11). Similar dragon-head styles were also known in Iceland by that time (Ágústsson, 343–7), and it is likely that the illuminators were familiar with the motif. An Icelandic example is the chapter seal of the Benedictine nunnery of Reynistaður in northern Iceland, which is considered a likely place of production for Helgastaðabók. The seal shows a stave church with dragon heads as extensions on the roof ridge, and it is likely that the seal mirrors the early fourteenth-century church of the nunnery (Drechsler, “Reynistaðakirkja”; Harðardóttir, 214–9). Nevertheless, the miniature in Helgastaðabók shows an iconographic model more likely to originate from earlier book paintings, such as the example from the Oscott Psalter. The bulky appearances of the throne extensions on f. 83v in AM 226 fol. are more likely to have been inspired by Scandinavian dragon-head sculptures, as well as physical chairs. In Viking-Age and medieval Scandinavia, thrones were, unlike many continental examples, made of wood and decorated with domestic ornamental and zoomorphic motifs that reflect various cultural and religious topics (Schramm, 317–8). In Norwegian church inventories from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a number of such chairs are mentioned. Although they do not automatically need to follow the same dating as other church art listed in the inventories (Hohler, 74), the carvings on the chairs seem to have been mainly influenced by the Anglo-Saxon tradition of the Tierstil II, mixed with Romanesque floral ornamentation and figural motifs from (mainly) Scandinavian traditions, such as the widespread Sigurðr “the Dragonslayer” legend. A number of such chairs exist today, such as the chair from Gålås (Oslo, Kulturhistorisk Museum, C26500) dated c. 1200 (Engelstad, 101) (Figure 12), and the chair from Gårå (Oslo, Nasjonalmuseet, OK-10700) roughly dated to the subsequent century (Schramm, 796). Especially, the example from Gålås shows related, large-sized animal heads with long tongues on the backrest, and this specimen mirrors the examples from AM 226 fol. and Helgastaðabók. Norwegian chairs such as the ones from Gålås and Gårå were generally used for officials or bishops, and it is likely that similar chairs were also known and used in Iceland. Church art, such as the mentioned Madonna from Urnes, may have also served as visual examples, where clearly identifiable ears and long noses of the Nordic-styled animal heads attached to the sedes sapientiae support the Scandinavian style of the seated holy figure.

Borgund Stave Church: Dragon head. 1180. Borgund. Image: W. Bulach. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Hedalen Stave Church: Martyrdom of St Becket. c. 1250. Hedalen. Image: Amanda Slater. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

C26500: Gålås Chair back rest. 1200. Oslo, Kulturhistorisk Museum. Image: Eirik Irgens Johnsen. Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Considering the variety of iconographic detail, it is likely that some of the long-necked animal heads in the Icelandic manuscripts represent a form of cultural syncretism which combines older religious and domestic ideas with newer stylistic impulses from European book painting. In this respect, the historical circumstances of the iconographic detail discussed in this article may be seen as a product of the combination of potential models stemming from internationally inspired model books (Flateyjarbók), domestic physical objects (AM 226 fol. and Helgastaðabók) and, not least, knowledge of vernacular texts that were illuminated (Svalbarðsbók). Although the use of iconographic model books is by no means specific to Icelandic scriptoria, since this practice flourished already during the early Gothic period on both sides of the Channel (Aliferis; Stones), the innovative spirit, which is found in many examples of text-related Icelandic book painting, is peculiar and best explained by the fact that few vernacular texts had previously been illuminated (Drechsler, “Zur Ikonographie,” 106–8, “Zur Ikonographie”, 290–1). With this in mind, the two manuscripts illuminated by Magnús Þorhallsson (AM 226 fol., Flateyjarbók) indicate a somewhat conservative use of the motif. This is also the case with the example from Skarðsbók discussed above, which originates from the same workshop. The other two examples from Svalbarðsbók and Helgastaðabók, on the other hand, show that the scriptoria responsible for these manuscripts were using iconographic models more independently: a feature that is well mirrored in further illuminations of the two codices, too (Jónsdóttir, 212–18; Drechsler, “Thieves”; Drechsler, “Chapter 6”). While the examples from AM 226 fol. and Flateyjarbók seem to demand a reading based on the imago-knowledge of the used iconographic models alone, the examples from Helgastaðabók and Svalbarðsbók may indicate a more abstract reading of historia (Belting), which is based on syncretistic ideas conveyed through the accompanying text and underlying moral standards. As for Helgastaðabók, one such standard appears to be found in the depicted ruler’s ability to overcome antagonistic forces, such as the Christological princeps omnium bestiarum.

To conclude, during the fourteenth century, Icelandic scriptoria made great use both of iconographic models known from other vernacular illuminations and sketchbooks and of physical objects such as church architecture and related items. While using such items as inspiration, it appears likely that the origin of text-related iconography in Icelandic book painting was established on the basis of cultural syncretism, where both the method of interpicturality and, at times, a good understanding of the text to be illuminated played particular roles. Due to the fact that few of the texts featured in the illuminated manuscripts had previously been illuminated, a rather innovative approach was taken by the Icelandic book painters to provide the texts with illuminations that contained both text-related and iconographic features known from other genres and with different moral exegeses. Overall, the iconography discussed in this article is perhaps best understood in relation to the syncretistic-cultural frames in which it was created and the variety of visual and textual inspiration on which it is based. By investigating both the cultural–historical frames of the book paintings and the more immediate relations visible in the text-image and image-to-image connections, we acquire a better and deeper understanding of the working techniques of the Icelandic illuminators. By investigating both the cultural framework and the working techniques as integral requirements for both the book paintings and the texts featured in an illuminated manuscript, new and interdisciplinary insights into medieval understandings of the iconographic images and the texts introduced through them can be gathered. This shows in two ways: on the one hand, and in relation to the main topic of this volume, image–image and text–image relations of a motif are generally seen in the attributes described in the accompanying texts. On the other hand, the motif also works as an independent agent of knowledge, which goes beyond direct adaptations of iconographic usage in the illuminations, and which embodies cultural historical frames of both European and specifically western Scandinavian arts of the Early and High Middle Ages.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers, as well as Jens Eike Schnall, John-Wilhelm Flattun, Sjur Haga Bringeland and especially Lena Liepe for their various comments on early drafts of this article. For the dating of all medieval Scandinavian manuscripts mentioned in this article, see the manuscript database of the Dictionary for Old Norse Prose, available at https://onp.ku.dk/onp/onp.php? m (last accessed May 6, 2021).

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

Works Cited

Ahn, Gregor. “Synkretismus. § 1: Religionsgeschichtlicher Ansatz: Forschungsgeschichte.” Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 30, edited by Heinrich Beck. De Gruyter, 2005, pp. 216–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Aliferis, Laurence Terrier. “The Models of the Illuminators in the Early Gothic Period.” The Use of Models in Medieval Book Painting, edited by Monika E. Müller. Cambridge Scholars, 2014, pp. 29–56.Suche in Google Scholar

Amory, Frederic. “Norse-Christian Syncretism and Interpretatio Christiana in Sólarljóð.” Gripla, vol. 7, 1990, pp. 251–66.Suche in Google Scholar

Bailey, Richard N. “Scandinavian Myth on Viking-period Stone Sculpture in England.” Old Norse Myth, Literature and Society. The Eleventh International Saga Conference, Sydney, 2–7 July 2000, edited by Geraldine Barnes, and Margaret Clunies Ross. Centre for Scandinavian Studies, 2000, pp. 15–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Bal, Mieke and Norman Bryson. “Semiotics and Art History.” Art Bulletin vol. 73, no. 2, 1991, pp. 174–208.10.2307/3045790Suche in Google Scholar

Baxandall, Michael. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy. A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. 2nd Revised Edition. Oxford University Press, 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

Beck, Heinrich. Snorri Sturlusons Sicht der paganen Vorzeit (Gylfaginning). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1994.Suche in Google Scholar

Belting, Hans. Bild und Kult. Eine Geschichte des Bildes vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst. Beck, Germany, 1990.Suche in Google Scholar

Benktsson, Herman. “Hövisk kultur i 1100-talets Norden?” Reykholt som Makt- og Lærdomssenter i den islandske og nordiske kontekst, edited by Else Mundal, Snorrastofa, 2006, pp. 195–214.Suche in Google Scholar

Bloch, P. “Löwe.” Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, vol. 4, 1972, pp. 112–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Blum, Wilhelm and Claudia List. “Evangeliar Ottos III.” Sachwörterbuch zur Kunst des Mittelalters: Grundlagen und Erscheinungsformen, edited by Claudia List and Wilhelm Blum. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1996, p. 114.Suche in Google Scholar

Brinchmann, Christian. Norske Konge-Sigiller og andere Fyrste-Sigiller. Det Mallingske Bogtrykkeri, 1924.Suche in Google Scholar

Björnsson, Björn Th. “Pictorial Art in the Icelandic Manuscripts.” Icelandic Sagas, Eddas, and Art. Treasures Illustrating the Greatest Medieval Literary Heritage of Northern Europe. Pierpont Morgan Library, 1982, pp. 26–38.Suche in Google Scholar

Carruthers, Mary J. The Craft of Thought. Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200. University of Cambridge Press, 2000.Suche in Google Scholar

Drechsler, Stefan. “Zur Ikonographie der AM 350 fol. Skarðsbók.” Collegium Medievale, 2014, pp. 63–113.Suche in Google Scholar

Drechsler, Stefan. “Thieves and workshops: On a historical initial in AM 343 fol. Svalbarðsbók.” Saltari stilltur og sleginn Svanhildir Óskarsdóttur fimmtugri 13. mars 2014, edited by Guðvarður Már Gunnlaugsson and Margrét Eggertsdóttir. Menningar- og minningarsjóður Mette Magnússon, 2014, pp. 37–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Drechsler, Stefan. “Ikonographie und Text-Bild-Beziehungen der GKS 1005 fol. Flateyjarbók.” Opuscula vol. 14, 2016, pp. 215–300.Suche in Google Scholar

Drechsler, Stefan. “Reynistaðakirkja hin forna. The Medieval Chapter Seal of the Benedictine Nunnery at Reynistaður.” Beyond Borealism: New Perspectives on the North, edited by Laura Ian Giles, Christian Chapot, and Ryan Foster Cooijmans and Barbara Tesio. Norvik Press, 2016, pp. 24–42.Suche in Google Scholar

Drechsler, Stefan. Illuminated Manuscript Production in Medieval Iceland. Literary and Artistic Activities of the Monastery at Helgafell in the Fourteenth Century. Brepols, 2021.10.1484/M.MSSP-EB.5.123671Suche in Google Scholar

Drechsler, Stefan. “Chapter 6: Jón Halldórsson and Law Manuscripts of Western Iceland c. 1320–40.” Dominican Resonances in Medieval Iceland: The Legacy of Bishop Jón Halldórsson of Skálholt, edited by Gunnar Harðarson and Karl G. Johansson. Brill, 2021, pp. 125–50.10.1163/9789004465510_008Suche in Google Scholar

DuBois, Thomas. “A History Seen: The Use of Illumination in Flateyjarbók.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 103, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1–52.Suche in Google Scholar

Early Gothic Manuscripts. 1190–1250 vol. 2, edited by Nigel J. Morgan and Harvey Miller, 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

Ekroll, Øystein. “St. Olav og olavssymbolikk i mellomalderske segl og heraldikk.” Helgekongen St. Olav i kunsten, edited by Øystein Ekroll, Museumsforlaget, 2016, pp. 143–89.Suche in Google Scholar

Engelstad, Eivind. “Gålås-stolen.” Viking. Tidsskrift for norrøn arkeologi, vol. 2, 1938, pp. 99–109.Suche in Google Scholar

Fett, Harry. Hellige Olav. Norges evige konge. Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1938.Suche in Google Scholar

Fjordholm, O. et al. (eds.). Norske sigiller fra middelalderen. Vol. 3: Geistlige Segl fra Nidaros Bispedømme. Riksarkivet, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

Flemming, J. “Palme.” Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, vol. 3, 1971, pp. 364–6.Suche in Google Scholar

Gothic Manuscripts. 1260–1320, vol. 2, edited by Stones, Alison. Harvey Miller, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

Graepler-Diehl, U. “Eherne Schlange.” Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, vol. 1, 1972, pp. 583–6.Suche in Google Scholar

Grandjean, Poul Bredo. Dansk Sigillografi. Schultz, 1944.Suche in Google Scholar

Gräsland, Anne-Sofie. “Stil och motiv. Några tankar kring vikingatidens ikonografi och ornamentik.” Institutionens historier: En vänbok till Gullög Nordquist, edited by Erika Weiberg, Susanne Carlsson and Gunnel Ekroth. Uppsala universitet, 2013, pp. 195–207.Suche in Google Scholar

Gräsland, Anne-Sofie. “Runic Monuments as Reflections of the Conversion of Scandinavia.” Dying Gods – Religious Beliefs in Northern and Eastern Europe in the Time of Christianisation, edited by Christiane Ruhmann and Vera Brieske. Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover, 2015, pp. 233–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Gullbekk, Svein H. “Olavsikonografi på mynt.” Helgekongen St. Olav i kunsten, edited by Øystein Ekroll. Museumsforlaget, 2016, pp. 109–41.Suche in Google Scholar

Guðrún Ása, Grímsdóttir. “Formáli.” Biskupa sögur III: Árna saga biskups; Lárentíus saga biskups; Söguþáttur Jóns Halldórssonar biskups; Biskupa ættir, edited by Grímsdóttir Guðrún Ása. Hið Íslenzka Fornritafélag, 1998, pp. v–cxxxvi.Suche in Google Scholar

Harðardóttir, Guðrún. “Myndheimir íslenskra klausturinnsigla.” Íslensk klausturmenning á miðöldum, edited by Haraldur Bernharðsson. Miðaldastofa Háskóla Íslands, 2016, pp. 210–25.Suche in Google Scholar

Gunnlaugsson, Guðvarður Már. “Manuscripts and Palaeography.” A Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture, edited by McTurk, Rory. Blackwell, 2005, pp. 245–64.10.1002/9780470996867.ch15Suche in Google Scholar

Gunnlaugsson, Guðvarður Már. “Voru scriptoria í íslenskra klaustrum?” Íslensk klausturmenning á miðöldum, edited by Haraldur Bernharðsson. Miðaldastofa Háskóla Íslands, 2016, pp. 173–200.Suche in Google Scholar

Hermannsson, Halldór. “Introduction.” Illuminated Manuscripts from the Icelandic Middle Ages, edited by Halldór Hermannsson. Ejnar Munksgaard, 1935, pp. 7–32.Suche in Google Scholar

Harrison, Andrew. “A Minimal Syntax for the Pictorial: The Pictorial and the Linguistic – Analogies and Disanalogies.” The Language of Art History, edited by Salim Kemal and Ivan Gaskell. University of Cambridge Press, 1991, pp. 213–39.Suche in Google Scholar

Hohler, Erla Bergendahl. “Helgiskírn.” Kirkja og kirkjuskrúð. Miðaldakirkjan í Noregi og á Íslandi. Samstæður og Andstæður, edited by Lilja Árnadóttir and Ketil Kiran. Norsk Institutt for Kulturminneforskning and Þjóðminjasafn Íslands, 1997, pp. 105–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Ágústsson, Hörður. “Isländischer Kirchenbau bis 1550.” Frühe Holzkirchen im nördlichen Europa, edited by Claus Ahrens. Helms-Museum, 1982, pp. 343–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Improta, Andrea. “Da Bologna a Napoli: il ms. VII.AA.8 della Biblioteca Nazionale ‘Vittorio Emanuele III’.” Confronto. Studi e ricerche di storia dell’arte europea, no. 3, 2020, pp. 75–81.Suche in Google Scholar

Sigurðsson, Jón Viðar. “Island og Nidaros.” Ecclesia Nidrosiensis 1153-1537. Søkelys på Nidaroskirkens og Nidaros-provinsens historie, edited by Imsen, Steinar. Tapir, 2003, pp. 121–40.Suche in Google Scholar

Kristjánsson, Jónas. Handritaspegill. Hið íslenska bókmenntafélag, 1993.Suche in Google Scholar

Jónsbók. Lögbók Íslendinga hver samþykkt var á Alþingi árið 1281 og endunýjuð um miðja 14. öld en fyrst prentuð árið 1578, edited by Már Jónsson. Háskólaútgáfan, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, Gunnar. Iceland’s 1100 Years. History of a Marginal Society. Hurst & Company, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

Kärber, B. “Salomo.” Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, vol. 4, 1972, pp. 15–24.Suche in Google Scholar

Kielland, Thor. Norsk Gullsmedkunst i Middelalderen. Steenske forlag, 1927.Suche in Google Scholar

Kroesen, Justin and Stephan Kuhn. The Medieval Church Art Collection. University Museum of Bergen (Norway). Schnell & Steiner, 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

Kålund, Kristian. Katalog over den Arnamagnæanske håndskriftsamling, vol. 2. Kommissionen for det Arnamagnæanske Legat, 1894.Suche in Google Scholar

Laag, H., “Thron (ohne Hetoimasia).” Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, vol. 4, 1972, pp. 304–5.Suche in Google Scholar

Lárentíus saga biskups. Biskupa sögur III: Árna saga biskups; Lárentíus saga biskups; Söguþáttur Jóns Halldórssonar biskups; Biskupa ættir, edited by Guðrún Ása Grímsdóttir. Hið Íslenzka Fornritafélag, 1998, pp. 215–441.Suche in Google Scholar

Lárusson, Magnús Már and Jónas, Kristjánsson (eds.). AM 217 8vo. Sigilla Islandica vetusta nobilorum ex ordine ecclesiastico virorum. Handritastofnun Íslands, 1965.Suche in Google Scholar

Lidén, Anne. “S. Olofs underliggare.” Den ljusa medeltiden: Studier tillägnade Aron Andersson, edited by Lennart Karlsson. Statens historiska museum, 1984, pp. 145–56.Suche in Google Scholar

Liepe, Lena. Studies in Icelandic Fourteenth Century Book Painting. Snorrastofa, 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

Leopold, Anita Maria, and Jeppe Sinding Jensen. Syncretism in Religion. A Reader. Routledge, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

Leopold, Anita Maria, and Jeppe Sinding Jensen. “The Knight and the Dragon Slayer: Illuminations in a Fourteenth-Century Saga Manuscript.” Ornament and Order: Essays on Viking and Northern Medieval Art for Signe Horn Fuglesang, edited by Margrethe C. Stang and Kristin A. Aavidsland. Tapis Akademisk Forlag, 2008, pp. 179–99.Suche in Google Scholar

Maurus, Rabanus. Patrologiae Cursus Completus. Series Latina, CIX, B. Rabani Mauri Fuldensis abbatis et Moguntini archiepiscopi opera omnia, vol. 3, edited by Jacques Paul Migne. Lutetiae Parisiorum, 1864.Suche in Google Scholar

Mitchell, William J. T. “The Pictorial Turn.” Artforum, vol. 30, no. 7, 1992, pp. 89–94.10.4324/9781315856506-35Suche in Google Scholar

Morgan, Nigel J. “Western Norwegian Panel Painting, 1250–1350: Problems of Dating, Styles and Workshops.” Norwegian Altar Frontals and Related Material vol. 1, edited by Magne Malmanger, Laszlo Berczelly and Signe Horn Fuglesang. Giorgio Bretschneider, 1995, pp. 9–23.Suche in Google Scholar

Morgan, Nigel J. “Dating, styles and groupings.” Painted Altar Frontals of Norway 1250–1350, vol. 3, edited by Unn Plahter. Archetype Publications, 2004, pp. 20–38.Suche in Google Scholar

Norseng, Per. “Olav den hellige.” Store norske leksikon. Available at https://snl.no/Olav_den_hellige [last accessed May 25 2021].Suche in Google Scholar

Halldórsson, Ólafur. Helgafellsbækur fornar. Bókaútgafa Menningasjóðs, 1966.Suche in Google Scholar

Halldórsson, Ólafur. “Á afmæli Flateyjarbókar.” Tímarit Háskóla Íslands, no. 2, 1987, pp. 54–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Panofsky, Erwin. “Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art.” Meaning in the Visual Arts, edited by Erwin Panofsky. Garden City, 1955, pp. 26–54.Suche in Google Scholar

Ragusa, Isa. “Terror Demonum and Terror Inimicorum: The Two Lions of the Throne of Salomon and the Open Door of Paradise.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 40/2 (1977), pp. 93–114.10.2307/1482022Suche in Google Scholar

Randell, Lilian M. C. “Exempla as a Source of Gothic Marginal Illumination.” The Art Bulletin vol. 39 (1957), pp. 97–107.10.1080/00043079.1957.11408369Suche in Google Scholar

Rensch, Roslyn. Harps and Harpists. Revised Edition. Indiana University Press, 2017.10.2307/j.ctt2005x7hSuche in Google Scholar

von Rosen, Valeska. “Interpikturalität.” Metzler Lexikon Kunstwissenschaft: Ideen, Methoden, Begriffe, edited by Pfister, Ulrich. Metzler, 2003, pp. 161–64.10.1007/978-3-476-00331-7_84Suche in Google Scholar

Schapiro, Meyer. “Über einige Probleme in der Semiotik der visuellen Kunst: Feld und Medium beim Bild-Zeichen.” Wege zur Bildwissenschaft. Interviews, edited by Klaus Sachs-Hombach. Halem Verlag, 2004, pp. 253–74.Suche in Google Scholar

Schramm, Percy Ernst. Herrschaftszeichen und Staatssymbolik: Beiträge zu ihrer Geschichte vom dritten bis zum sechzehnten Jahrhundert vol. 1, Stuttgart, 1954.Suche in Google Scholar

Selma Jónsdóttir. “The Illuminations in Helgastaðabók.” Helgastaðabók. Nikulás saga Perg. 4to Nr. 16 Konungsbókhlöðu í Stokkhólmi, edited by Selma Jónsdóttir, Stefán Karlsson and Sverrir Tómasson. Lögberg, 1982, pp. 202–28.Suche in Google Scholar

Stang, Margrethe C. “Helgekongen og alterbildet.” Helgekongen St. Olav i kunsten, edited by Øystein Ekroll. Museumsforlaget, 2016, pp. 27–53.Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, Stefán. “Introduction.” Sagas of Icelandic Bishops: Fragments of Eight Manuscripts, edited by Stefán Karlsson. Rosenkilde & Bagger, 1967, pp. 9–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, Stefán. “Uppruni og ferill Helgastaðabókar.” Helgastaðabók. Nikulás saga Perg. 4to Nr. 16 Konungsbókhlöðu í Stokkhólmi, edited by Selma Jónsdóttir, Stefán Karlsson and Sverrir Tómasson. Lögberg, 1982, pp. 42–89.Suche in Google Scholar

Steger, Hugo. David: Rex et propheta. König David als vorbildliche Verkörperung des Herrschers und Dichters im Mittelalter, nach Bilddarstellungen des 8. bis 12. Jahrhunderts. Carl, 1961.Suche in Google Scholar

Stones, Alison. “Sacred and Profane Art: Secular and Liturgical Book-Illumination in the Thirteenth Century.” The Epic in Medieval Society: Aesthetic and Moral Values, edited by Harald Scholler. Max Niemeyer Verlag, pp. 100–12.Suche in Google Scholar

Tómasson, Sverrir. “Íslenskar Nikulás sögur.” Helgastaðabók. Nikulás saga Perg. 4to Nr. 16 Konungsbókhlöðu í Stokkhólmi, edited by Selma Jónsdóttir, Stefán Karlsson and Sverrir Tómasson. Lögberg, 1982, pp. 11–41.Suche in Google Scholar

Trætteberg, Hallvard. “Kongesegl.” Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder, vol. 9, edited by Finn Hødnebø. Gyldendal, 1964, pp. 46–61.Suche in Google Scholar

Voretzsch, A. “Stab.” Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie, vol. 4, 1972, pp. 198–98.Suche in Google Scholar

Wanscher, Ole. Sella Curulis. The Folding Stool. An Ancient Symbol of Dignity. Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1980.Suche in Google Scholar

Wormald, Francis. “The Throne of Salomon and St. Edward’s Chair.” De Artibus Opuscula XL: Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky, edited by Millard Meiss. New York University Press, 1961, pp. 532–35.Suche in Google Scholar

Würth, Stefanie. “Nachwort.” Isländische Antikensagas, Vol. 1, edited and translated by Stefanie Würth. Diedrichs, 1996, pp. 301–24.Suche in Google Scholar

Zuschlag, Christoph. “Auf dem Weg zu einer Theorie der Interikonizität.” Lesen ist wie Sehen: Intermediale Zitate in Bild und Text, edited by Silke Horstkotte and Karin Leonhard. Böhlau Verlag, 2006, pp. 89–99.10.1353/mon.2007.0055Suche in Google Scholar

Helgadóttir, Þorbjörg. “Formáli.” Rómverjasaga vol. 1, edited by Þorbjörg Helgadóttir. Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi, 2010, pp. cxxx–cxxxii.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Writing the Image, Showing the Word: Agency and Knowledge in Texts and Images, edited by Jørgen Bakke, Jens Eike Schnall, Rasmus T. Slaattelid, Synne Ytre Arne - Part II

- Cultural Syncretism and Interpicturality: The Iconography of Throne Benches in Medieval Icelandic Book Painting

- Rousseau’s Herbarium, or The Art of Living Together

- Special Issue: Russian Speakers After Migration, edited by Ekaterina Protassova and Maria Yelenevskaya

- Introduction: Everyday Verbal and Cultural Practices of the Russian Speakers Abroad

- Failing or Prevailing? Russian Educational Discourse in the Israeli Academic Classroom

- Cultural and Linguistic Capital of Second-Generation Migrants in Cyprus and Sweden

- Russian-Speaking Families and Public Preschools in Luxembourg: Cultural Encounters, Challenges, and Possibilities

- “I’m Home”: “Russian” Houses in Germany and Their Objects

- Conceptualizing Russian Food in Emigration: Foodways in Culture Maintenance and Adaptation

- From Odessa to “Little Odessa”: Migration of Food and Myth

- Domestication of Russian Cuisine in the United States: Wanda L Frolov’s Katish: Our Russian Cook (1947)

- A Russian Aristocrat in the Principality of Liechtenstein: Life Trajectories, Material Culture, and Language

- A Russian Story in the USA: On the Identity of Post-Socialist Immigration

- Special Issue: Plague as Metaphor, edited by Nahum Welang

- Introduction: How Metaphors Remember and Culturalise Pandemics

- The Humanities of Contagion: How Literary and Visual Representations of the “Spanish” Flu Pandemic Complement, Complicate and Calibrate COVID-19 Narratives

- “We’ve Forgotten Our Roots”: Bioweapons and Forms of Life in Mass Effect’s Speculative Future

- The Holobiontic Figure: Narrative Complexities of Holobiont Characters in Joan Slonczewski’s Brain Plague

- “And the House Burned Down”: HIV, Intimacy, and Memory in Danez Smith’s Poetry

- Regular Articles

- Social Connection when Physically Isolated: Family Experiences in Using Video Calls

- “I’ll see you again in twenty five years”: Life Course Fandom, Nostalgia and Cult Television Revivals

- How I Met Your Fans: A Comparative Textual Analysis of How I Met Your Mother and Its Reboots

- Transnational Business Services, Cultural Transformation/Identity, and Employee Performance: With Special Focus on Migration Experience and Emigration Plan

- Rethinking Agency in the European Debate about Virginity Certificates: Gender, Biopolitics, and the Construction of the Other

- The Mirror Image of Sino-Western in America’s First Work on Travel to China

- Strategies of Localizing Video Games into Arabic: A Case Study of PUBG and Free Fire

- Aspects of Visual Content Covered in the Audio Description of Arabic Series: A Corpus-assisted Study

- Translator Trainees’ Performance on Arabic–English Promotional Materials

- Youth and Intergenerational Transmission of Cultural Intelligence in Latvia, Spain and Turkey

- On the Happening of “Frank’s Place”: A Neo-Heideggerian Psychogeographic Appreciation of an Enchanted Locale

- Rebuilding Authority in “Lumpen” Communities: The Need for Basic Income to Foster Entitlement

- The Case of John and Juliet: TV Reboots, Gender Swaps, and the Denial of Queer Identity