Abstract

The development of standards and guidelines for undergraduate chemistry programs across the globe can ensure that students and faculty have the facilities, curriculum, skills, and infrastructure to support chemistry education. The American Chemical Society began its exploration of standards in the United State in the 1930s culminating in the ACS Approval Program, which currently includes over 700 programs in the United States. In 2019, ACS embarked on the development of an ACS Recognition Program for programs worldwide. The development of guidelines and standards for these related, but not identical, programs is based on the core principles of the ACS and the needs of the broader chemistry education community. It involved an iterative process that included contributions from chemistry professionals, educators, employers, and other stakeholders, with feedback from the broader academic community. The goal of these guidelines and the approval and recognition programs is to ensure that students have an engaged faculty, a safe and inviting space to learn, access to modern instrumentation for teaching and research, a safe, inclusive, and equitable environment in which to learn, and the content knowledge and skills needed for success as a chemical professional.

1 Introduction

Accreditation in the United States focuses on ensuring that students have the skills and knowledge necessary for post graduate success and simultaneously encourages programs to strive toward continuous improvement. 1 Guidelines and standards for accreditation are developed through a systematic process that includes contributions from stakeholders including academic institutions, professionals in the field, and employers that hire degree recipients. Development of these standards and guidelines is iterative and involves a multistep process that includes identifying needs and priorities, data collection, sharing draft guidelines with the broader community, and then adoption. The guidelines are revisited periodically to ensure that they remain relevant.

The Committee for Professional Training (CPT) at the American Chemical Society (ACS) is tasked with the development of standards and guidelines for undergraduate education in chemistry. Guidelines developed by this committee are derived from the interplay of faculty across the world as well as from chemists outside of academia with the goal to ensure that students in undergraduate programs that are ACS Approved (in the United States) and ACS Recognized (worldwide) have the skills, content knowledge, and experience necessary to be successful in their career paths. There are currently over 700 programs in the United States that are ACS Approved. These range from large research institutions with graduate programs to smaller primarily undergraduate institutions. Over 18,000 students earned bachelor’s degrees from these institutions in 2024 and account for more than 95 % of the bachelor’s degree recipients in chemistry in the U.S. 2 In an effort to reflect the global nature of the ACS, the ACS Global Recognition program was developed in 2019 and currently (as of November 2024) consists of a cohort of 6 programs and is growing steadily. The first three programs recognized were Mahidol University International College (Thailand); Swansea University (Wales), and Universidad del Valle (Colombia). These programs provided feedback on the recognition process and the guidelines established for global recognition, and we are grateful for the role they played in the development of the program, especially because much of the work done by these programs was done during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2 Development of guidelines for undergraduate chemistry programs

The ACS Guidelines for Bachelor’s Degree Programs were originally developed in the 1930s when the lack of consistent and rigorous training resulted in a shortage of trained chemists. The guidelines were developed to ensure that bachelor’s degree recipients had training that was appropriate for the jobs available at the time. Since the 1930s, there have been numerous revisions of the guidelines, 3 , 4 with the most recent version completed in 2023. In each of these revisions, the committee was careful to not only get the input from the broader chemistry community but to also maintain adherence to both the core values of ACS and the basic tenets of accreditation. 1 , 5 , 6 The U.S. Department of Education requires that standards and guidelines for accrediting bodies ensure that institutions of higher education meet acceptable levels of quality. 7 While the ACS is not an accrediting body, the Approval and Recognition programs were designed to reflect the characteristics of accreditation, i.e., the process is voluntary, is a form of self-evaluation, based on peer review, and is based on requirements that are representative, flexible, and appropriate. 8

To ensure that the requirements are representative, the guidelines developed for the approval and recognition programs are based on the core values of the ACS:

A passion for chemistry and the global chemistry enterprise

Professionalism, safety, and ethics

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and respect (DEIR)

A focus on members

These guidelines are used by chemistry programs to guide their educational practices, to create and maintain a balanced workload for faculty, ensure that students receive instruction in skills and content needed for successful careers, and be used by the department as leverage to obtain modern instrumentation as well as safe and modern spaces for instruction and laboratories. They should not prevent innovation by being too prescriptive, be too rigid to be applied globally, nor should they favor highly resourced institutions.

3 The ACS guidelines

The ACS Guidelines for Bachelor’s Degree Programs in the U.S. were revised in 2023. Previous iterations of the guidelines specified the requirements to obtain or maintain approval, but did not include guidance for programs to innovate. In the 2023 revision, guidance for innovation and continuous improvement were explicitly included through the creation of three categories of standards: Critical Requirements, which are the essential components of the guidelines and required for programs to obtain or maintain ACS Approval; Normal Expectations, which are suggested practices and provide more depth to the critical requirements; and Markers of Excellence, which are aspirational goals that encourage innovation. The latter two categories provide guidance for programs interested in developing their programs beyond the basics and encourage a sense of continuous development. There is an expectation that programs will utilize these elements as they strive for continued excellence, but their approval status does not depend on them. When developing the ACS Guidelines for International Programs, this structure was maintained to encourage a climate of continuous improvement and to provide a pathway for innovation. The international guidelines were also based on programmatic core principles that evolved as the recognition program was being developed in 2019. These core principles include expanding engagement with higher education institutions globally; advancing excellence in post-secondary chemistry education; promoting engagement of the global community for exchange of effective practices; and improving the knowledge and career preparedness of students and supporting faculty across the globe.

4 ACS international guidelines

The ACS International Guidelines for recognition of global programs in the chemical sciences were developed from the bachelor’s degree programs in the U.S. The guidelines are based on six pillars (Figure 1), which are essential components of an undergraduate chemistry program. This is similar to the standards set forth by the Royal Society of Chemistry 9 and those of the Chemical Institute of Canada. 10

The ACS Guidelines are based on six pillars: Infrastructure, faculty and staff, curriculum, skills and proficiencies, safety, and DEIR.

Infrastructure: This pillar focuses on instrumentation, access to journals and search engines, safe spaces for instruction and laboratories, and support from the broader institution for the chemistry program. This ensures that faculty have the tools that they need to provide effective instruction, conduct research, and work in laboratories that are modern and safe.

Faculty and Staff: To ensure that faculty have the time to devote to teaching, research, and service activities, the guidelines mandate a maximum number of contact hours for faculty; here contact hours are defined as the time that the faculty member spends actively teaching students in defined courses. Additional duties, like course preparation, grading, supervising research students, and lab prep were included when developing these guidelines.

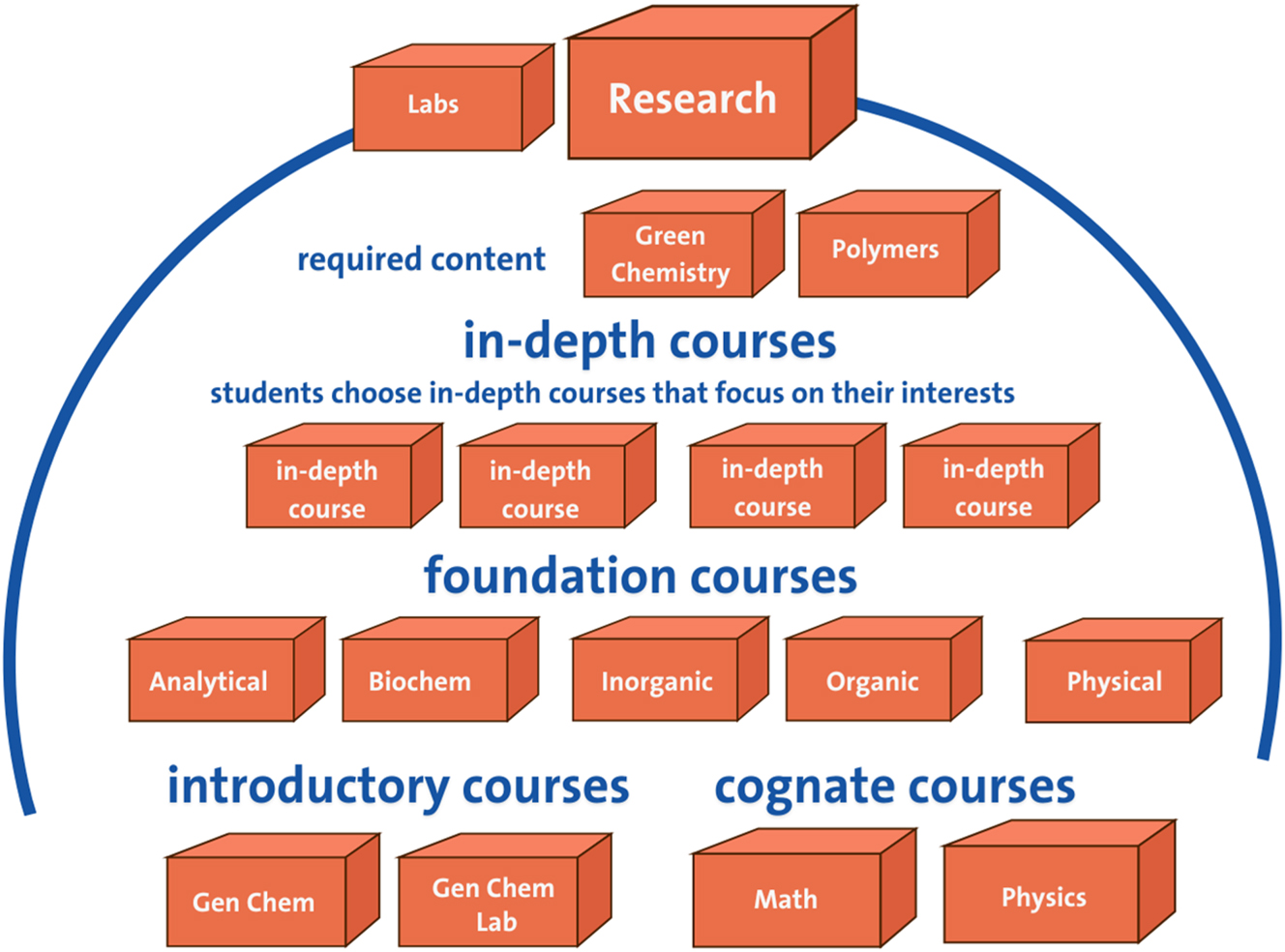

Curriculum: The curriculum (Figure 2) defined by the guidelines allows programs the flexibility to develop courses that are focused on the needs of the students at that institution. It is based on a foundation of courses that provide instruction beyond general chemistry in five subdisciplines of chemistry: analytical, biochemistry, inorganic, organic, and physical (ABIOP). This foundational knowledge is then supported by in-depth courses that provide content knowledge that relies on the foundation courses. The guidelines do not dictate content for the in-depth courses, nor do they require that they focus on specific areas of chemistry. Typically, the second semester of organic acts as one of these courses (the content in the course building on the foundation organic course). The second semester of physical chemistry is also typically described as a foundation course; here the content doesn’t necessarily build on the foundation material, but instead broadens it.

A depiction of the required curricular components as described in the ACS Guidelines. The requirements allow flexibility in the in-depth courses so that students can choose a path consistent with their interests. The in-depth courses should delve deeper into the content covered in the foundation courses. Green chemistry and polymer chemistry must be covered as part of the curriculum. Research and lab courses are essential components to a robust education in the chemistry curriculum.

The guidelines also require that students have 350 h of lab experiences beyond general (or introductory) chemistry. These experiences should cover four of the five ABIOP subdisciplines. Research can account for 130 of these hours. The guidelines also mandate that the majority of these lab activities occur in person to ensure that students get hands-on experience with instrumentation, computer simulations/calculations, and techniques essential to their future career paths.

The final piece of the curriculum described in the guidelines focuses on content. The curriculum must include instruction in Macromolecular, Supramolecular, and Nano/Meso Scale Systems (MSN) that covers two of the following areas: synthetic polymers, biological macromolecules, supramolecular aggregates, and meso- or nanoscale materials. It must include synthesis, characterization, and a description of the physical properties of these materials. In 2023 an additional content area was included. Programs must now teach the 12 principles of green chemistry as part of their curriculum. For both of these content areas, the content can be taught in a dedicated course but is more often distributed amongst courses currently taught in the program.

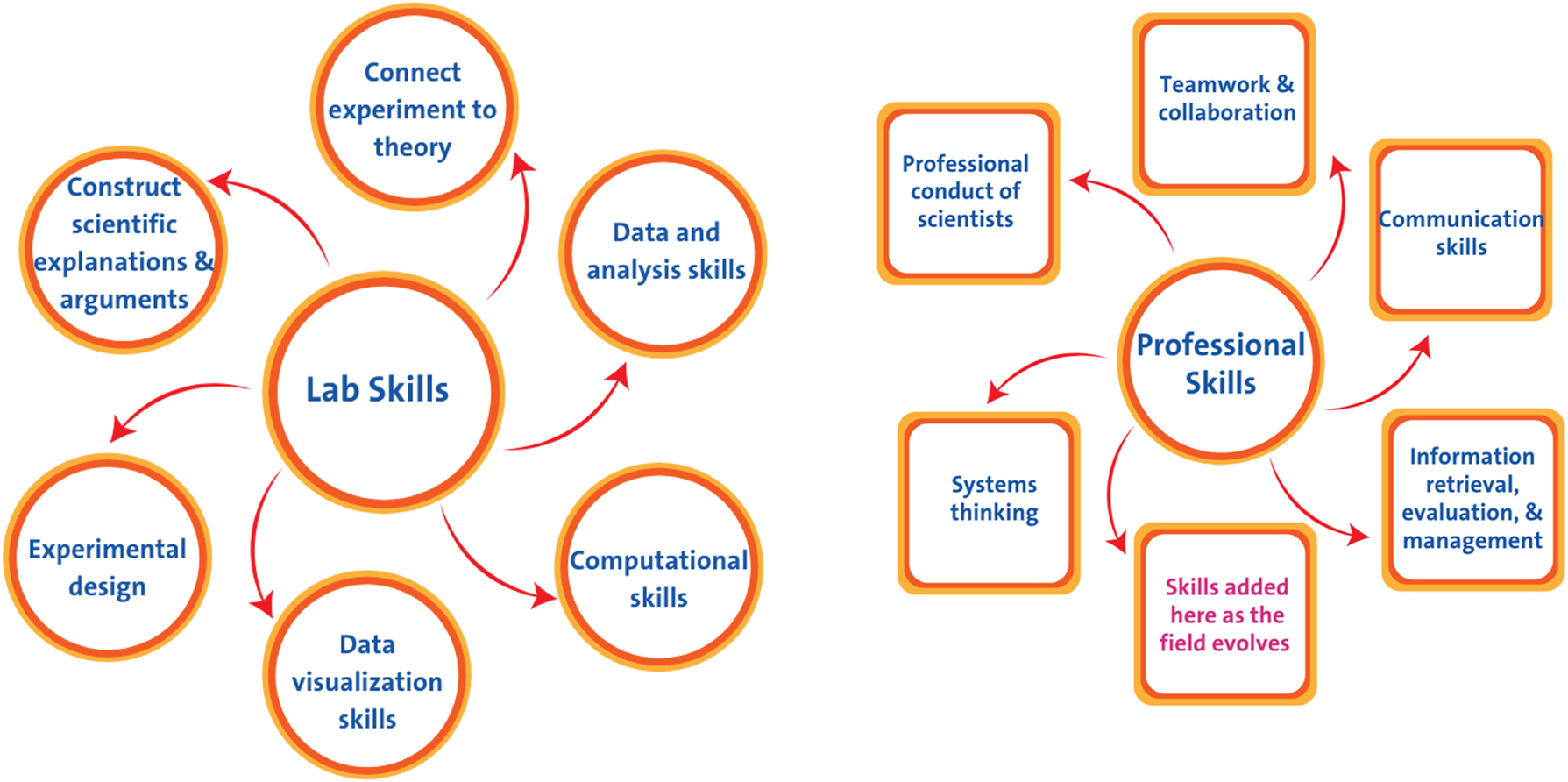

Skills and Proficiencies: While content knowledge contributes to the success of students earning bachelor’s degrees, the development of “soft” skills is also essential for all post graduate career paths. In the 2023 guidelines, these skills were divided into two categories: Laboratory Skills and Professional Skills (Figure 3).

Laboratory skills and professional skills as described in the ACS Guidelines. As the need arises for the development of new skills (e.g., using AI), there is flexibility to further develop this section.

These skills should be developed across the curriculum, introduced in early courses and then reinforced in more advanced courses. There should be a built-in assessment of the skill, and the information collected from the assessment should be used as part of a feedback loop to strengthen and further develop the assignment. While the lab skills are self-explanatory, the professional skills may need some clarification. Professional conduct of scientists, previously described as “ethics,” include both micro- and macro-ethics, the former addressing scientific integrity and ethics at the personal level while the latter addresses the global implications of the science being done. 11 Teamwork and collaboration go beyond working as lab partners in class and relies on the interplay of unique skills that each team member brings to the table. 12 Communication skills include both oral and written communication presented to a wide variety of audiences, including lay people as well as colleagues. Systems thinking 13 provides a framework for understanding the interconnectedness of chemistry to the broader, and more complex, environment in which it is performed. It includes consideration of both global and societal impacts. Frameworks for shifting chemistry education to this approach have been developed and can be implemented into the curriculum. 14 , 15 The last aspect of professional skills is left empty to designate the evolving nature of the skills needed to be a successful chemist. This area could reflect the development of artificial intelligence and how to utilize it effectively and ethically. It represents the dynamic nature of the guidelines and the educational world.

Safety and DEIR: The final two pillars of the guidelines represent the core values of the American Chemical Society and were highlighted with separate sections in the 2023 guidelines. The safety section was developed in conjunction with the ACS Committee on Chemical Safety (CCS) and the Division of Chemical Health and Safety (CHAS) and includes developing a safety-first mindset, respect for chemical processes, and safe laboratory experimentation. It trains students how to plan for potential safety incidents and how to resolve them. The DEIR section includes a focus on training, recruitment and retention of both faculty and students, the development of policies and procedures to address issues of discrimination, bias (micro/macro) aggressions, prejudice, and harassment, and the development of plans to review, revise, and communicate these policies to the students, faculty, staff, and administration.

5 The global recognition program

The process for applying for ACS Recognition utilizes these guidelines, but differs in two significant ways from the process in the U.S. First, the application process does not include the site visit that is required for ACS Approval. The logistics of travel for a site visit precluded its inclusion in this iteration of the program. Programs interested in recognition complete a pre-application that provides the CPT reviewers with a broad overview of the program, including a description of their instrumentation suite, curriculum, and contact hours for faculty. These are the primary areas where programs may deviate from the requirements in the guidelines. If the pre-application meets the guidelines, then the program completes a more comprehensive application that addresses the different sections of the guidelines. The application is reviewed by members of CPT, a conference is convened between representatives of the department and the reviewers where the program’s goals, outcomes, and any ambiguities in the application are addressed. In the ACS Approval process, a site visit follows the conference; for the recognition program, the committee then decides on whether the program meets the guidelines and votes on recognition. The second major difference with the ACS Approval Program is that individual students do not receive certified degrees for completing the required curriculum. Because the path to a degree varies widely across the globe, committee members felt that this would not be amenable given that variety.

6 Challenges

Creating a global recognition program did come with its share of challenges, most of which are rooted in the wide variation of educational systems across the world. This was first observed in the foundation course requirements, specifically biochemistry. In many programs internationally, biochemistry is often taught outside of the chemistry department and not included in the curriculum as a requirement the core concepts of biochemistry are often included elsewhere in course work. This was addressed by focusing more on content than on course descriptions; this flexibility and content focus allows programs to meet the goal of that guideline, i.e., that students receive instruction in biological chemistry. The curricular challenges are addressed as part of the conference that CPT has with representatives from the institutions that apply for recognition. At that time, any inconsistencies are cleared up via the submission of supporting materials or a more in-depth conversation.

The bigger challenge, and one that is a concern in the U.S.-based approval program, focuses on diversity, equity, and inclusion. As a core value of ACS, this section of the guidelines is essential. The question of how it could be applied globally is a challenge, one that is shared with other professional organizations that accredit programs internationally. 16 , 17 There is a current initiative to revise these guidelines to focus on equitable access to education for students in the classroom and lab and for processes in place to ensure that students, faculty, and staff have a voice. This is a moving target and we expect multiple changes as the landscape in the U.S. and across the globe changes.

7 Benefits of the ACS approval/recognition program

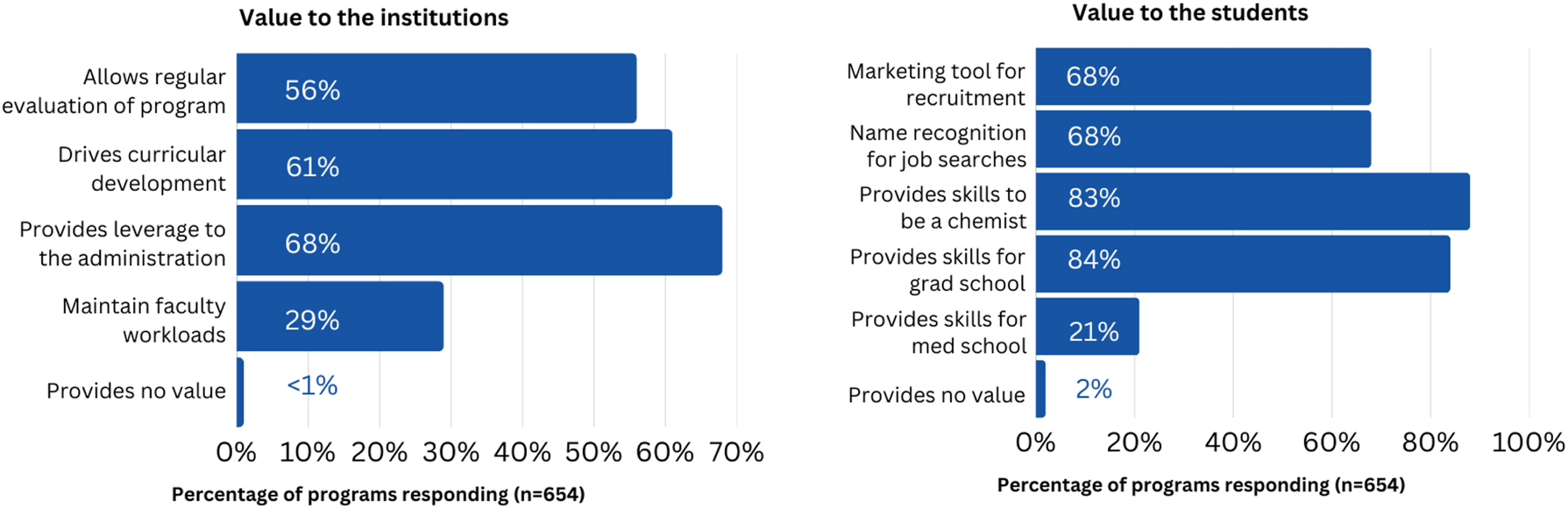

To investigate the value that ACS Approval provides to programs, in 2022 a short survey was included with the annual reporting documents required of all approved programs. The results are shown in Figure 4. Of the 654 (93 %) programs that responded to the survey, it was clear that the primary benefits of approval are that it provides leverage to the administration, drives curricular development, and allows for regular evaluation of the program. The guidelines are used to help programs acquire institutional support for instrumentation purchases, additional faculty and staff lines, and maintenance of laboratories and facilities.

Results from a survey deployed in 2022 to 654 ACS approved institutions in the U.S. querying the value of ACS approval to the institutions (L) and to the students (R). Programs could choose more than one response, the data reflect the percentage of all programs that chose that response.

ACS Approval also benefits the students in the program (see Figure 4R). Programs that are approved ensure that students receive a comprehensive education in chemistry, have opportunities to do research, develop data analysis and laboratory skills, receive training in laboratory safety, and learn in an inclusive and equitable environment, all of which can contribute to their post graduate success. Programs also use the approval as a way to market themselves to students. Students from approved programs associated with the ACS gain a considerable advantage due to the widespread recognition and respect that the ACS name holds within academic and industrial circles. This affiliation can open doors to numerous opportunities, including internships, research collaborations, and employment prospects.

Based on the responses from approved programs, it is expected that recognized programs will reap similar benefits. Through conversations with faculty and administrators applying for recognition, programs seek ACS Recognition to enhance their students’ job and graduate school prospects in wider geographic areas. This is also supported by the literature. Adiatama and coworkers 18 suggest that higher education institutions pursue international accreditation for several reasons. These include achieving international recognition for effective operations, enhancing internal motivation to promote a quality culture, ensuring the sustainability of institutions or programs, serving as a strategic investment, enhancing the institution’s global reputation, increasing competitiveness, and demonstrating accountability to stakeholders. Other motivations include enhancing student and faculty mobility, increasing international collaborations, and to foster continuous improvement through the adoption of best practices. 19 , 20 , 21

Similar to the approved institutions, ACS recognized institutions also use the requirements to help obtain instrumentation, develop curricula, and provide an education that is comprehensive. Recognized programs receive microcredentials to use on their websites and social media that advertise their programs as meeting the ACS Guidelines.

8 Concluding remarks

Overall, the development of guidelines and standards for a global chemistry education program must be a dynamic process, done with the inclusion of the larger chemistry community, be flexible enough to encourage innovation, and provide a framework for maintaining the infrastructure needed to support the needs of chemists. The guidelines should provide support for students, faculty, and staff involved in chemistry education through standards that limit workload for faculty, include broader skill development for students, and ensure that staff are trained to support education in a diverse, supportive, and safe environment. These guidelines and standards can then form the foundation of a broader accreditation, approval, or recognition program, which can provide value to an undergraduate chemistry program by encouraging self reflection, curricular review, and provide leverage for the departments with their administrators thus resulting in programs that support students, faculty, and staff in their professional goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Dr. Jodi Wesemann, Dr. William Carroll, and the members of the ACS Committee on Professional Training’s Global Activities team in developing the ACS Recognition Program.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Council for Higher Education Accreditation. An Overview of U.S. Accreditation, Council for Higher Education Accreditation: Washington D.C, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Institute of Education Sciences U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), 2024. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/SummaryTables/report/360?templateId=3600&year=2023&expand_by=0&tt=aggregate&instType=1&sid=dfb6f161-7f95-48f4-951b-02b339432442.Suche in Google Scholar

3. McCoy, A. B.; Darbeau, R. W. Revision of the ACS Guidelines for Bachelor’s Degree Programs. J. Chem. Ed. 2013 90, 398–400; https://doi.org/10.1021/ed400084v.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Polik, W. F.; Larive, C. K. New ACS Guidelines Approved by CPT. J. Chem. Ed. 2008 85(4), 484–487; https://doi.org/10.1021/ed085p484.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Tractenberg, R. E.; Lindvall, J. M.; Atwood, T. K.; Via, A. Guidelines for Curriculum and Course Development in Higher Education and Training. Open Arch. Soc. Sci. (SocArXiv) 2020, 1–18; https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/7qeht.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Yang, H. Y. Leading Program Curriculum Reform: Reflections on Challenges and Successes. Edu. Action Res. 2024, 1–19; https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2024.2385410.Suche in Google Scholar

7. U.S. Department of Education. College Accreditation, 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/higher-education-laws-and-policy/college-accreditation.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. The Principles of Accreditation: Foundation for Quality Enhancement, 2024. (2024 Edition ed.). SACSCOC: https://sacscoc.org/app/uploads/2024/01/2024PrinciplesOfAccreditation.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Royal Society of Chemistry. Accreditation of Degree Programmes. Accreditation of Degree Programmes, 2024. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from: https://www.rsc.org/globalassets/03-membership-community/degree-accreditation/accreditation-of-degree-programmes.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Canadian Society of Chemistry CSC Accreditation Guidelines. CSC Accreditation Guidelines, n.d. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from: https://www.cheminst.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/CSC-Accreditation-Canadian-Guidelines-EN-06082022.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Chen, K.-C.; Hester, L. L. A Dramatized Method for Teaching Undergraduate Students Responsible Research Conduct. Account. Res. 2023, 30 (3), 176–198; https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2021.1981871.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Cole, R.; Reynders, S.; Stanford, C.; Lantz, J. Constructive Alignment beyond Content: Assessing Professional Skills in Student Group Interactions and Written Work. In Research into Practice in Chemistry Education - Advances from the 25th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education; Schultz, M.; Schmid, S.; Lawrie, G.; Springer: Sydney, Australia, 2019.10.1007/978-981-13-6998-8_13Suche in Google Scholar

13. Orgill, M.; York, S.; MacKellar, J. Introduction to Systems Thinking for the Chemistry Education Community. J.Chem.Ed. 2019, 96 2720–2729; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00169.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Talanquer, V.; Szoda, A. R. An Educational Framework for Teaching Chemistry Using a Systems Thinking Approach. J.Chem.Ed. 2024, 101 1785–1792.10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00216Suche in Google Scholar

15. Tumay, H. Systems Thinking in Chemistry and Chemical Education: A Framework for Meaningful Conceptual Learning and Competence in Chemistry. J.Chem.Ed. 2023, 3925–3933; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c00474.Suche in Google Scholar

16. AACB International. Managing the Complexities of Accreditation. Managing Complexities Accred. 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2025, from: https://www.aacsb.edu/insights/articles/2023/10/managing-the-complexities-of-accreditation.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Velton, J. C.; Zertuche, A. Tackling Upcoming Accreditation Challenges Around DEI. DEI in Higher Education. n.d. Retrieved January 8, 2025, from: https://enflux.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/DEI-in-Higher-Ed_Enflux-and-Go-Culture.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Adiatma, T.; Mahriadi, N.; Suteki, M. Importance of International Accreditation for Global Recognition for Higher Education. J. Digit. Learn. Dist. Educ. 2022, 1(5), 195–199, https://rjupublisher.com/ojs/index.php/JDLDE/article/view/53.10.56778/jdlde.v1i5.53Suche in Google Scholar

19. Lynch, M. (2025). Internationalization of Higher Education and the Importance of Accreditation. The Edvocate. https://www.theedadvocate.org/internationalization-of-higher-education-and-the-importance-of-accreditation/.Suche in Google Scholar

20. International Association for Quality Assurance in Pre-Tertiary and Higher Education (QAHE). The Benefits of International Accreditation: Why It’s Preferred over Local Accreditation. 2023. Retrieved 1 3, 2025, from: https://www.qahe.org.uk/article/the-benefits-of-international-accreditation-why-its-preferred-over-local-accreditation/.Suche in Google Scholar

21. USAID & Arizona State University. The Accreditation Playbook Quick Start Guide and Compilation of Best Practices. BUILD-IT Playbook Series 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from: https://www.edu-links.org/sites/default/files/media/file/the_accreditation_playbook.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 27th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education (ICCE 2024)

- Special Issue Papers

- Recent advances in laboratory education research

- Examining the effect of categorized versus uncategorized homework on test performance of general chemistry students

- Enhancing chemical security and safety in the education sector: a pilot study at the university of Zakho and Koya University as an initiative for Kurdistan’s Universities-Iraq

- Leveraging virtual reality to enhance laboratory safety and security inspection training

- Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in college chemistry

- High school students’ perceived performance and relevance of chemistry learning competencies to sustainable development, action competence, and critical thinking disposition

- Spatial reality in education – approaches from innovation experiences in Singapore

- Teachers’ perceptions and design of small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

- Electricity from saccharide-based galvanic cell

- pH scale. An experimental approach to the math behind the pH chemistry

- Engaging chemistry teachers with inquiry/investigatory based experimental modules for undergraduate chemistry laboratory education

- Reasoning in chemistry teacher education

- Development of the concept-process model and metacognition via FAR analogy-based learning approach in the topic of metabolism among second-year undergraduates

- Synthesis of magnetic ionic liquids and teaching materials: practice in a science fair

- The development of standards & guidelines for undergraduate chemistry education

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 27th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education (ICCE 2024)

- Special Issue Papers

- Recent advances in laboratory education research

- Examining the effect of categorized versus uncategorized homework on test performance of general chemistry students

- Enhancing chemical security and safety in the education sector: a pilot study at the university of Zakho and Koya University as an initiative for Kurdistan’s Universities-Iraq

- Leveraging virtual reality to enhance laboratory safety and security inspection training

- Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in college chemistry

- High school students’ perceived performance and relevance of chemistry learning competencies to sustainable development, action competence, and critical thinking disposition

- Spatial reality in education – approaches from innovation experiences in Singapore

- Teachers’ perceptions and design of small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

- Electricity from saccharide-based galvanic cell

- pH scale. An experimental approach to the math behind the pH chemistry

- Engaging chemistry teachers with inquiry/investigatory based experimental modules for undergraduate chemistry laboratory education

- Reasoning in chemistry teacher education

- Development of the concept-process model and metacognition via FAR analogy-based learning approach in the topic of metabolism among second-year undergraduates

- Synthesis of magnetic ionic liquids and teaching materials: practice in a science fair

- The development of standards & guidelines for undergraduate chemistry education