Abstract

The integration of Spatial Reality technologies in educational settings has gained momentum as a powerful instrument for teaching and learning. While research has consistently shown the significant potential of these technologies in enhancing students’ knowledge acquisition and retention, a phenomenon termed “VR teaching anxiety” persists among many educators, leading to hesitancy in adopting Spatial Reality into their teaching practices. In this paper, the authors shed light on the specific concerns related to VR teaching anxiety reported by educators. To mitigate these anxieties, the authors recount their firsthand experiences with employing Spatial Reality technologies in chemistry education at a higher education institution in Singapore. Additionally, they offer a suite of recommended practices gleaned from their journey, aiming to empower educators to confidently integrate these innovative tools into their curricula.

1 What is spatial learning?

Spatial Learning (SL), according to Liu, Ding, and Meng, is the acquisition of spatial knowledge, crucial for individual’s everyday engagement with their surroundings (Liu et al., 2021). SL is the core feature of many Spatial reality technologies available in the market. These technologies empower learners to effortlessly transition between physical and digital spaces without the need for physical movement or device changes (Mulquin, 2024). Spatial learning has become more widely-used since the COVID-19 pandemic where remote learning becomes prevalent in response to lockdown measures initiated by various governments worldwide to stem the spread of the virus (Al-Ansi et al., 2023; World Bank, n.d.).

1.1 Virtual reality, augmented reality, and spatial reality

Schroeder defined Virtual Reality (VR) as “A computer-generated display that allows or compels the user (or users) to have a sense of being present in an environment other than the one they are actually in and to interact with that environment” (Kardong-Edgren et al., 2019; Schroeder, 1996), while Milgram et al. (1995) defined Augmented Reality (VR) as “A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum”. Since then, there have been many advancements being made for both technologies. Thus, there are no universally accepted definitions for both VR and AR (Kardong-Edgren et al., 2019; Laato et al., 2024).

Spatial Reality (SR) is a concept that encompasses VR, AR, and other related technologies. While both VR and AR can be immersive (Czok et al., 2023), SR offers a 3D optical experience that seamlessly blends the physical and digital worlds. It is a novel technology that has gained significant traction in recent years, particularly in the realm of education, because of its ability to create immersive and interactive learning environments.

Even though there are no consensus in the definitions of the various terminologies in SR technologies (Laato et al., 2024), the authors provided a list of technical terms, their associated abbreviations, and their general descriptions relevant to this article in Table 1.

List of technical terms, their abbreviations, and general terms used in this paper.

| Technical term | Abbreviation | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial learning | SL | The ability to perceive and utilize spatial information within a given environment, regardless of whether it is real or virtual. |

| Spatial reality | SR | A fusion of augmented and virtual realities (VR), offers a 3D optical experience that seamlessly blends the physical and digital worlds. |

| Augmented reality | AR | A technology that uses existing real-world environment and overlays it with virtual information such as images, videos, or texts. |

| Virtual reality | VR | A fully immersive technology that create a simulated environment that fully replaces the real-world surroundings. Simulated environments are typically experienced using a VR headset and users can interact and manipulate virtual objects within that environment. |

| eXtended reality | XR | An umbrella term that encompasses all immersive technologies. VR, AR, and MR fall into this category. |

| Metaverse | – | A collective shared virtual space that is accessible through the internet. Users – usually represented by an avatar – can interact with one another and participate in various activities via the online digital environment in real time. |

2 Meaningful chemistry education and context-based learning

According to Westbroek et al. (2005), Meaningful Chemistry Education (MCE) consists of three tenets: (1) context, (2) need to know, and (3) attention to student input. Context entails making sure that the context used is demonstrably relevant to students’ lived experiences and existing knowledge while simultaneously being pertinent to and supportive of the acquisition of target chemical concepts (van Dinther et al., 2023; Westbroek et al., 2005). Westbroek et al. opined that a well-defined, and contextualized learning content would enable students to understand the utility of the contents being taught, as well as motivating the students to learn those contents (Westbroek et al., 2005). Need to know is characterized by a situation in which learners identified a problem, desired to learn to expand their knowledge in the attempt to solve said problem, and are cognizant about this gain in knowledge (van Dinther et al., 2023). This enables students to understand the usefulness of acquiring knowledge, reducing the likelihood of students wondering about the purpose of learning a particular concept (Westbroek et al., 2005). Finally, attention to student input is related to the need to know. Westbroek described that educators should pay attention to students’ input as these inputs contain their insights into and experience the functionality of “what comes next”. Students felt that their opinion matters in class, and that can promote learning. All three of these tenets work closely together to provide a meaningful education (Westbroek et al., 2005).

Broman et al. (2018) further emphasized the importance of context-based learning (CBL) for problem solving by highlighting that contextualization of the learning content targets the affective as well as cognitive aspects of learning. This can influence students’ motivation and interest in learning a particular topic, as well as enhancing their problem-solving ability, with the latter developed using higher order thinking.

3 Use of SR in education

Al-Ansi et al. (2023) conducted a literature review on the trends on the uptake of SR technologies by measuring the number of publications related to the technologies. They found that since 2011, there has been an increase in publications related to SR, with the COVID-19 pandemic period experiencing an exponential growth in the number of publications (Al-Ansi et al., 2023). These statistics indicate the growing adoption of SR technologies by educators to supplement their lessons. Indeed, SR has found itself being used for teaching and learning in many fields such as language learning (Parmaxi, 2023), natural sciences (Brown et al., 2021; Pimpasri & Limpanuparb, 2024; Rodríguez et al., 2023), medicine (Dhar et al., 2023; Ntakakis et al., 2023), and humanities (Pangsapa et al., 2023), among many others.

There are also many studies that showed promising effects on students’ learning. For instance, Wu, Yu, and Gu conducted a meta-analysis on the use of immersive VR on learning performance (Wu et al., 2020). They did a systematic search and analyzed 35 randomized controlled trials that employed VR for teaching and learning and found that immersive VR using HMDs (Head-mounted display) are more effective – albeit with a small effect size – than non-immersive learning methods in knowledge retention and development of skills, especially in the areas of science education compared to traditional lecture formats or real world practices (Wu et al., 2020). In another study, Conrad, Kablitz, and Schumann conducted a systematic review the effect of immersive VR on learning by analyzing 30 research articles (Conrad et al., 2024). The researchers found that immersive learning environment with HMD yields a positive learning outcome compared to other media types such as videos and presentation slides (Conrad et al., 2024). The researchers further suggested that immersive VR may be more appropriate as a teaching and learning tool for “action-oriented environments” that place emphasis on learners’ engagement (Conrad et al., 2024).

3.1 SR in chemistry education

In the field of chemistry education, chemistry educators have described in various literatures how they designed or incorporated SL educational tools (Koscielniak, 2021). For instance, van Dinther et al. (2023) described how they designed three animated immersive virtual reality (IVR) experience using the three characteristics of MCE (Westbroek et al., 2005) as a guiding principle. Two animated IVR – acid-base concepts for high school students, and the same concepts for undergraduate students – were designed by VR professionals with van Dinther guiding these professionals in designing the lesson. The third IVR is a 360° IVR experience targeting high school students learning about salt and their impact on aquatic animals in high salinity ponds, were created by van Dinther and another educator. The authors found that all three IVR were positively received by students, and the researchers concluded that through IVR with MCE, students felt more motivated in learning chemistry, and understood the chemical concepts better (van Dinther et al., 2023). In another study, Gao et al. (2023) described designing an AR mobile app for teaching the process of continuous distillation. The features in the app include the ability for the app user to simulate the process of operating the apparatus for continuous distillation, observe how liquids and vapors flow in the distillation column, as well as allowing users to zoom in and rotate the apparatus to see the process in various perspectives. The mobile app also makes use of advanced algorithms and calculations to provide real time and accurate simulations of the continuous distillation process (Gao et al., 2023). The results of the study indicated that the app helped students to understand the process of continuous distillation. Students’ perception of the app was also positive as it was easy to navigate, stimulated their interests in the subject, as well as provided them with enhanced understanding of the basic concepts of the continuous distillation process (Gao et al., 2023). Finally, Frevert and Di Fuccia (2020) shared their experience on how they created two VR projects for teaching various chemistry concepts: (1) Dead Herring, and (2) Virus Experiences for Chemistry Education. Frevert and Di Fuccia concluded that the learning environments provided by VR and other related technologies would help to motivate students to learn better, and that students benefitted from these technologies by enhancing their understanding of the content taught (Frevert & Di Fuccia, 2020).

3.2 Anxiety in using technology can be mitigated

Despite the increased adoption of SR in teaching as well as studies that showed the potential of SR in helping students to learn better, many teachers were still feeling nervous about the technology and are thus reluctant to adopt SR to supplement their curriculum. In 2024, Zhong et al. characterized this apprehension as VR teaching anxiety, a variant of teaching anxiety described by Thomas as the feelings that hinder educators from initiating, sustaining, or completing instructional activities (Gorospe, 2022; Thomas, 2006; Zhong et al., 2024). Zhong and team proposed that there are two types of factors that could affect teaching VR anxiety – individual teaching factors, and external environmental factors. Individual teaching factors include technical proficiency, and self-efficacy, while external environmental factors include school support (Zhong et al., 2024). Although not articulated specifically, school support, in the views of the authors, covers professional development, resources and facilities, recognition and the existence of a collaborative environment (Zhong et al., 2024). According to Zhong, both school support and self-efficacy can influence teachers’ technical proficiency. Teachers with low self-efficacy would be less likely to adopt VR technology in their lesson as they may not be confident with their technical proficiency and expected themselves to fail should they incorporate them during class (Hsieh & Schallert, 2008). In addition, given that VR in education is a relatively new phenomenon, teachers have to learn new technical skills and this process may require time (Myers et al., 2017), depending on the complexity of VR tools used. All these factors could cause teachers to experience “technostress” – stress caused by incorporating Information and communication technology (ICT) into teaching and learning (Li & Wang, 2021; Wang & Zhao, 2023), further reducing the acceptance of VR.

The authors believe that SL can facilitate in providing Meaningful Chemistry Education by incorporating some of the tenets of MCE. Herein, they describe some of their experiences in using SL tools for teaching chemistry, how they applied aspects of MCE into SL, as well as offering their recommended approaches for SL for readers who wish to incorporate SP tools into their curriculum. It is hoped that by doing so, this can allay the potential worries that educators may have regarding the technology, as well as showing that using such technologies is not intimidating, and could benefit both the educators as well as their students.

4 Use cases of spatial learning platform for training and education

Spatial learning platforms, such as Uptale.io (hereon referred to as “Uptale” in this article), a web based VR creation tool which provide user friendly interfaces for educators to enable easy creation and deployment of VR (Uptale, n.d.). Uptale allows teachers and students to create immersive 360-degree virtual reality experiences for training and education. Such platforms are designed to make learning more engaging, efficient, and effective by providing a more interactive and realistic environment. One key feature of such SL platform is that users can explore virtual environments and interact with objects and characters. The second key feature, perhaps the most crucial one, is that there is no coding requirement by the users – anyone can create immersive content without programming knowledge. Given that SL could deliver MCE, and the benefits of using Uptale’s SL platform, the authors have created three VR projects (two of which have been published in a Journal) using Uptale for immersive learning – VR sampling, VR crime scene, and VR excursion.

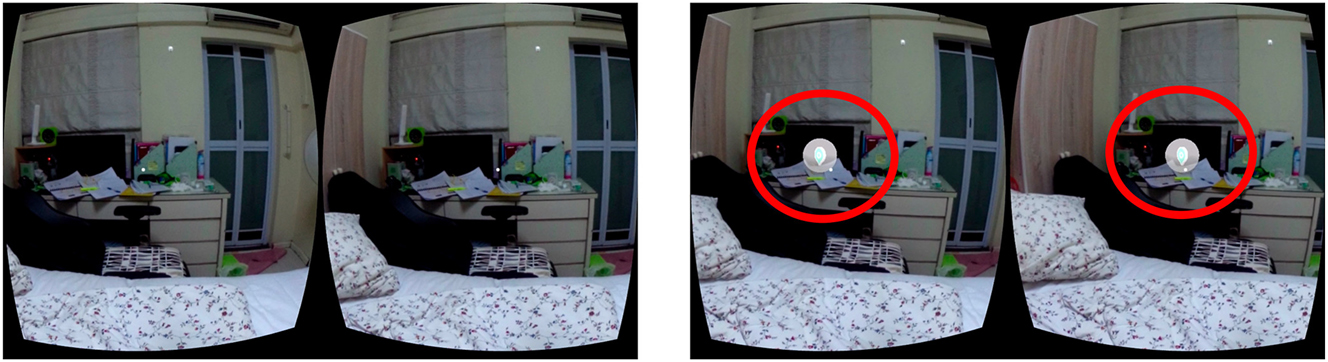

VR sampling (Uptale – Water Sampling, n.d.) was created in 2017 and aimed towards undergraduates taking the laboratory course on analytical chemistry. In this interactive VR experience, students were introduced to how air quality sampling and water quality sampling were done in Singapore. Instructors of the course gave a guided tour on the various instruments used to sample and measure air and water quality while viewers watch from the perspective of the cameraman. In addition to the cameraman’s perspective, at certain points of the virtual tour, viewers were also provided an option by clicking on the pop-up menu to switch the camera’s perspective – such as from the instructor’s perspective to the inside of the sampling instruments in question. Quizzes in the form of multiple-choice questions were also added to help refresh some of the concepts taught during the virtual tour. Figure 1 shows some screenshot taken from the VR sampling.

Images showing screenshots of VR sampling. On the left, a pop-up window shows a live screencast from an instructor’s smartphone. The image on the right shows a pop-up window showing the camera from the instructor’s perspective.

VR crime scene (VR Crime Scene (TRIAL), n.d.) is a crime scene simulator aimed towards undergraduate students taking a minor in Forensic Science (Han & Fung, 2023; Kader et al., 2020). The VR crime scene was created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic where measures such as social distancing were enforced to stem the spread of the virus (Lee, 2020). Due to the logistical issue such as finding a bigger room to enforce social distancing rule, as well as the time needed to prepare and execute a physical crime scene activity, the teaching team – consisting of course instructors as well as a former student – decided to employ the use of VR to circumvent these limitations (Kader et al., 2020). In this VR crime scene, students wear a VR headset and explore a simulated crime scene where they collect evidence by interacting with the VR elements to solve crime as seen in Figure 2.

Screenshot of VR crime scene from the user’s perspective. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Kader, S. N., Ng, W. B., Tan, S. W. L., & Fung, F. M. (2020). Building an interactive immersive virtual reality crime scene for future chemists to learn forensic science chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 2651–2656. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

VR excursion is a virtual excursion that brings students to a virtual excursion to Ungaran, Indonesia (Fung et al., 2019; Han & Fung, 2023). Aimed towards chemistry undergraduate taking an elective course in Environmental Chemistry, students don on their VR headset, or a pair of VR glasses affixed to their smartphone and explore the virtual surroundings of Ungaran and apply the concepts that they have learnt during class as shown in Figure 3. VR excursion was created in response to the scheduling conflicts as students have packed timetables, making it difficult to find a suitable time for everyone to go for either a local or overseas excursions. Furthermore, there are also logistical challenges such as transport and cost in bringing a substantial number of students to an excursion location at the same time. As the teaching team (comprising of course instructors as well as former students) understood the importance of having an excursion to enable students to consolidate their learning, the teaching team leveraged on VR (Fung et al., 2019).

Image on the left shows the virtual environment as seen from the perspective of the user. Image on the right shows the VR headsets compatible with VR excursion. (A) Is a typical VR headset while (B) is a pair of VR goggles that can be affixed onto the smartphone’s screen for added immersivity. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Fung, F. M., Choo, W. Y., Ardisara, A., Zimmermann, C. D., Watts, S., Koscielniak, T., …, Dumke, R. (2019). Applying a virtual reality platform in environmental chemistry education to conduct a field trip to an overseas site. Journal of Chemical Education, 96(2), 382–386. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

5 Creation of VR sampling, VR crime scene, and VR excursion

The VR sampling, VR crime scene, and excursion, leverage on Uptale, the following table lists the equipment required for VR creators, and end-users to create, and experience the three VR projects respectively (Table 2).

Equipment list for VR creators and end-users when using Uptale.

| VR creators | End-users |

|---|---|

| Computer (desktop or laptop) | Smartphone/computer |

| 360° camera | VR headset/VR goggles/google cardbox (optional) |

For the creation of all three VR projects, the teaching team used the Roch Theta S as the 360° camera to take 360° photos and videos of the surrounding. For instance, the teaching team took 360° videos of the surroundings where various sampling instruments were located when making VR sampling. In the case of VR crime scene, the surrounding was a simulated crime scene taken at a house belonging to one of the teaching team while for VR excursion, the teaching team flew to Ungaran to take the pictures there. During the creation of all three projects, former students for the respective courses provided their perspective on the difficulties that they and their peers frequently encounter while learning the course, enabling educators to design VR experiences that would address those problems. In addition, the students also assisted in the VR creation process by operating the 360° camera.

The 360° photos and videos were then uploaded to Uptale platform via a computer for further processing such as adding of interactive elements (Fung et al., 2019; Kader et al., 2020).

5.1 VR crime scene trial and students’ receptivity

37 undergraduate students minoring in Forensic Science took part in the VR crime scene trial as part of their online assignment (Kader et al., 2020). After going through the VR crime scene and submitting their online report, they were asked to complete an online questionnaire to gather their receptivity towards VR crime scene. The results of the online questionnaire indicated that more than half of the students (79 %) had a positive experience with VR overall. From the qualitative comments provided by the students, many indicated that the crime scene was well-planned. However, some of the students felt that they had difficulty navigating the surrounding, while others brought up the issue of poor image quality in the VR crime scene (Kader et al., 2020).

5.2 VR excursion students’ trial and receptivity

VR excursion was trialed with a group of junior and senior years undergraduate students reading the elective Environmental Chemistry course (Fung et al., 2019). The excursion was conducted during lecture session over the span of two lessons. During the excursion, students either wore a VR headset, or a pair of VR goggles affixed to their smartphone’s screen (see Figure 4), and they were guided by the lecturer to various points of interests.

Students immerse themselves in the VR excursion.

Afterwards, the students were free to roam and explore the surroundings. Each lesson lasted about 1.5 h. After the VR excursion, students completed an online survey questionnaire to ascertain their perception towards the VR excursion. Based on the survey results, 64 % of the students had positive experience with the VR excursion. For the open-ended question, students mentioned that some aspects of the VR elements could not be discerned clearly and that having a zoom feature would be good. Other students also mentioned a feeling of disorientation and motion sickness, a phenomenon that is well documented in various literatures (Broyer et al., 2021; Park & Lee, 2020; Roettl & Terlutter, 2018).

All three VR projects mentioned previously possess the tenets (1) and (3) of MCE. For (1), all three VR experiences contextualize the concepts that were taught in class. For instance, in the VR water sampling, students were given a glimpse of how air and water quality around the university’s campus were sampled using the techniques that they had learnt in class. For VR crime scene, students get to apply the skills of analyzing and collecting of evidence based on the situations given in the virtual crime scene. Finally, for VR excursion, students get to explore and experience the intricate relationship that human activities have on the environment and vice versa of a real location virtually.

For (3), the teaching team partnered with former students of each of the three courses in which the respective VR projects were implemented and listened to the challenges which they faced while learning the course. The formation of this partnership is called Students as Partners (Cook-Sather, 2016; Cook-Sather et al., 2014). Their perspective helped to shape the way the VR experience was designed.

6 Creation of metaverse – MyVirtualLab

Besides using Uptale platform to design and create VR experience, the authors also explored creating their own metaverse for chemistry education.

6.1 MyVirtualLab

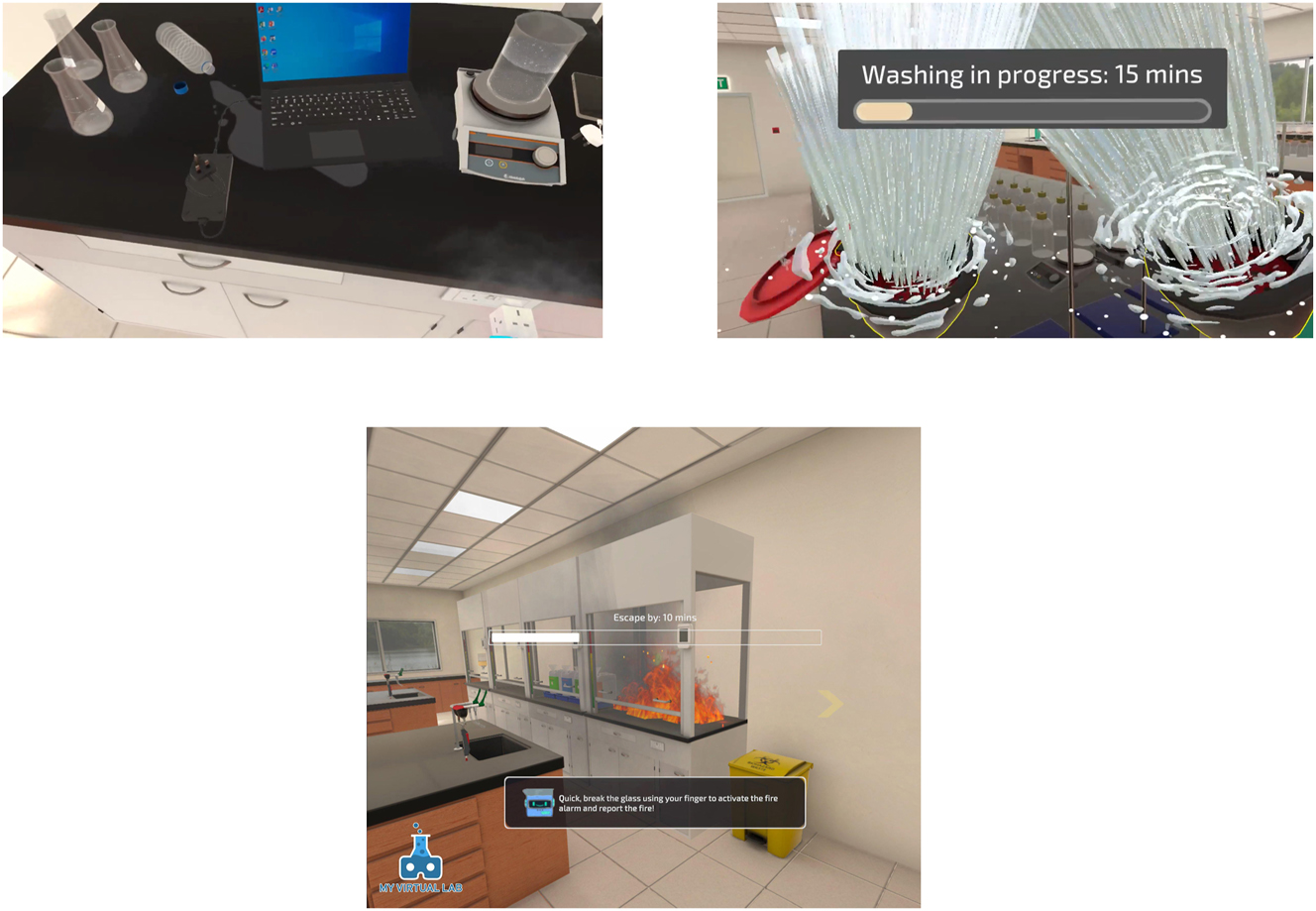

MyVirtualLab (MVL) is a virtual laboratory aimed towards chemistry undergraduate and postgraduate students, with the plan to expand to other students studying in other STEM fields. Created with metaverse in mind (Ritterbusch & Teichmann, 2023), MVL provides a virtualized environment for students to learn about laboratory safety protocols as well as train themselves in various experimental techniques such as column chromatography. By simulating various scenarios that can occur while working in the laboratory, MVL enables students to be familiarized with safety protocols and experimental techniques without putting the users in danger. Figure 5 shows the interface of MVL as seen by the users.

Sample interface of MVL. Prompts are included in MVL to provide hints to users on what to do when dealing with laboratory emergencies.

By wearing an Oculus Quest 3 VR headset, users can interact with MVL’s virtual environment and elements using their hands. Furthermore, as MVL is hosted on the Photon Unity PUN server (Photon, n.d.), multiple users can login to MVL simultaneously and interact with one another using their custom avatars.

6.2 Conceptualizing of MVL – interdisciplinary approach

The interdisciplinary MVL team, with members comprised of chemistry faculty, biochemistry faculty, and software engineers, storyboard artists, and product experience designers. While the faculty provided domain expertise and ensured the accuracy of experimental techniques and safety protocols, the non-academic staff focused on drafting the storyboard, user interface, and implementing educational content within MVL, based on the input and expertise from the faculty.

Given the team’s diverse backgrounds, open communication was crucial. To overcome potential language barriers and ensure clarity on scientific terminology and experimental techniques, regular online meetings were held to address questions and provide project updates. Additionally, the MVL team utilized Miro, a digital collaborative whiteboard, to facilitate brainstorming, idea visualization, and task tracking, ensuring all team members were aligned on project goals and deadlines (Miro, n.d.; Ng et al., 2022).

6.3 Understanding the laboratory environment

The nature of teaching laboratories is those of an active learning environment (Seery et al., 2024), and the laboratory sessions at the National University of Singapore is no exception. Discussions among the students and their peers on the experimental procedures are encouraged, and laboratory instructors also took part in promoting the active learning environment by providing feedback to students on their experimental procedures as well as clarifying questions students have. Thus, it is essential for MVL to provide the functionality for students to collaborate and interact with one another to promote an active learning environment. To gain a deeper understanding of the laboratory environment and student experiences, the technical team conducted in-person observations of laboratory sessions facilitated by the scientific team. By witnessing first-hand the daily interactions and challenges students encounter, the team was able to gather valuable insights for accurately simulating these experiences within the MVL platform. Additionally, interviews with students provided further perspectives on their laboratory workflows, challenges, and expectations for MVL.

6.4 User interface design considerations

To inform the design of interactive mechanics within MVL, the team has members to develop a comprehensive plan encompassing object manipulation, such as grabbing and pouring liquids between vessels, and movement mechanics upon consultation with the faculty who are the domain expert. This planning was informed by a thorough research process involving the selection of popular VR games from the Oculus Store that featured similar mechanics and the recruitment of students to test these games. The faculty played a key role in recruiting various students, from undergraduates to post-graduates.

During the testing of the popular VR games from Oculus Store, the team members carefully observed participant interactions with the VR environment, noting any difficulties they encountered and gathering their perceptions on the effectiveness of the game mechanics, interfaces, and tutorials.

Some of the difficulties that the participants encountered when playing the games were:

Hitting the surrounding real-life objects surrounding them when playing and moving in the virtual world.

Unintuitive interface and unhelpful tutorials.

Participants failed to notice certain visual cues in the game.

Taking the students’ account into consideration, the team created a UI/UX for MVL that combined both visual and audio elements to enhance the immersivity of the VR experience. These elements include both onscreen and verbal cues to guide the users on how to interact with the VR elements, as well as instructions on how to complete an activity in MVL. Furthermore, to minimize users from hitting their surroundings, the product experience designers chose the use of finger gesture instead of moving around the VR surroundings.

6.5 Laboratory skills covered in MVL

Currently, MVL covers laboratory safety protocols as the laboratory teaching felt that this is the most important skill to acquire before students can work in the laboratory (Gallion et al., 2015). Some of the topics covered regarding laboratory safety include but not limited to:

Dealing with fires in the laboratory

Chemical decontamination (safety showers and eye shower operation)

Global Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals

Importance of Personal Protective Equipment

6.6 Contextualizing laboratory safety

To help contextualize laboratory safety in MVL, the team collaborated to design the storyboard of various laboratory emergencies commonly encountered while working in the laboratory. Some of the scenarios include laboratory evacuation in case of fire, as well as preventing electrical hazards. Furthermore, MVL also added some realism into the scenario to simulate the time sensitivity when dealing with such emergencies. For instance, the team created an experience where MVL users must identify the electrical hazards present while working in the laboratory. In another scenario, users were taught how to use the eye shower to flush chemicals from their eyes, and what to do when there is a fire occurring in the laboratory. The screenshot of each of these scenarios are illustrated in Figure 6 below.

Examples of various emergencies encountered in the laboratory. Clockwise from top left: identifying and removal of electrical hazards, using eye showers to flush out chemicals in the eyes, and dealing with fire in the laboratory.

6.7 MVL trial on postgraduate students

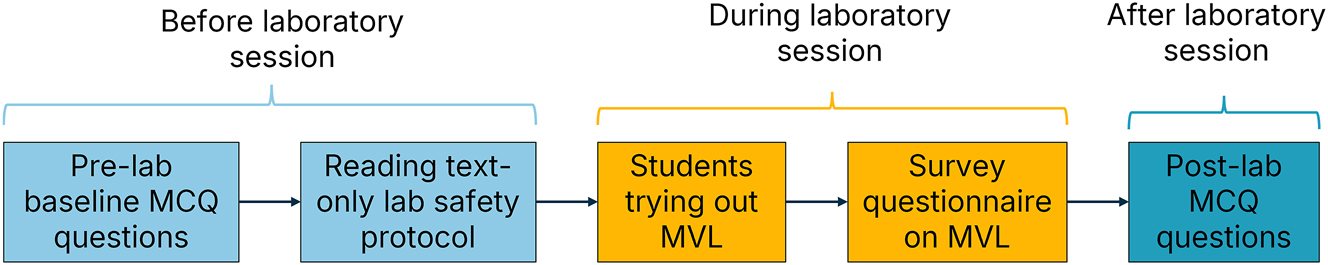

MVL was studied with 16 postgraduate students taking a laboratory course as part of the core curriculum for their Master of Science in Industrial Chemistry program. The study received ethics board approval (Departmental Ethics Review Committee (DERC), reference ID “Psych-DERC reference code: 2024-March-03”) prior to the start of the research., Before the start of the first laboratory session, students were tasked to complete a pre-lab baseline quiz consisting of 20 multiple-choice questions (MCQ) to assess their knowledge of laboratory safety protocol. After completing the pre-lab baseline quiz, the laboratory instructor uploaded the text-only laboratory safety protocol used by the university onto the Learning Management System for the students’ references.

During the first laboratory session, the laboratory instructor highlighted the importance of understanding laboratory safety, and that they will be learning about this using MVL. They were also informed that participation in the MVL activity is voluntary and contributes 5 % of their overall grade for the course. Should they choose to decline participation in MVL, the student will be offered an alternative method to earn the participation score by writing an essay on laboratory safety. All 16 students agreed to partake in the MVL activity. During the activity, the technical team was also present to guide the students on how to wear the headset and to render assistance should the students encounter any difficulty. Upon completion of the MVL activity which lasted about half an hour, the students filled up an anonymized survey to understand their perception and receptivity of MVL.

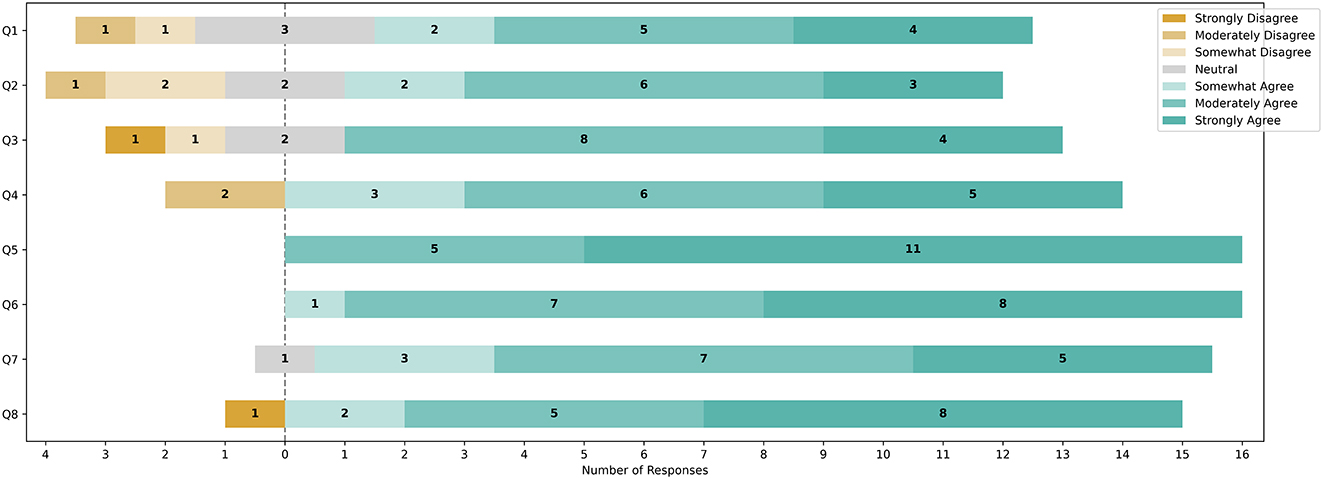

The survey questionnaire – based on Holden and Rada (2011) – consists of 12 questions, 8 of the questions are Likert based questions where students were tasked to rank their level of agreement for each of the eight statements using a seven-point scale where 1 being the most negative, and 7 being the most positive. The remaining four questions are open-ended questions to enable students to elaborate on the reasoning behind ranking some of the Likert statements. Table 3 shows the survey questions that were asked to the students, as well as their question type.

Survey questions and their question types.

| S/N | Survey questions | Question type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I find MyVirtualLab (MVL) to be easy to use. | Likert scale |

| 2 | Interacting with MVL does not require a lot of my mental effort. | |

| 3 | Learning how to perform the tasks in MVL is easy. | |

| 4 | I find MVL to be intuitive to use. | |

| 5 | The use of MVL enhances my understanding of laboratory safety. | |

| 6 | I find MVL to be useful in helping me to understand laboratory safety. | |

| 7 | I find it easy to get MVL to do what I want it to do. | |

| 8 | I have no problem with the learning materials presented in MVL. | |

| 9 | Please tell us why you chose the rating for statement 5. | Open-ended question |

| 10 | Please tell us why you chose the rating for statement 6. | |

| 11 | Please tell us why you chose the rating for statement 8. | |

| 12 | What areas of improvement would you like to suggest for virtual laboratory? |

After the laboratory session, the students completed the post-lab quiz – consisting of the same sets of 20 MCQ found in the pre-lab quiz – to assess if MVL helped the students to have a better understanding of laboratory safety protocol. Figure 7 summarizes the overall study procedure for the trial.

Summary of the procedure of the study for the research participants.

6.8 Students’ performance on both pre- and post-lab quizzes

Table 4 summarizes the mean scores students obtained for their pre- and post-lab quizzes.

Students’ mean scores for pre-lab and post-lab quizzes.

| Type of quiz | Mean score (%) |

|---|---|

| Pre-lab quiz | 60.5 |

| Post-lab quiz | 69.1 |

A Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to ascertain the normality of the students’ data. It was found that the students’ scores do not fit the normal distribution (p-value = 0.069 (>0.05)). Following which, a one-tailed Mann-Whitney U Test was conducted at 5 % level of significance to measure if there was a significant improvement in the post-lab quiz compared with the pre-lab quiz score. The result indicated that there was a statistically significant improvement in students’ knowledge in laboratory safety protocol after using MVL (p-value = 0.048 (<0.05)).

6.9 Students’ receptivity of MVL

ptIn general, MVL was positively received by students (N = 16) as shown in Figure 8. More than 50 % of the students felt that MVL was easy to use (Q1), and that it did not require a lot of mental effort to interact with the VR elements (Q2). Furthermore, the majority of the students surveyed also agree that performing the tasks in MVL was easy (Q3), and that MVL was intuitive to use (Q4). All the students surveyed agreed that MVL helped to enhance their understanding of laboratory safety (Q5). 15 students also felt that MVL was useful in learning laboratory safety (Q6).

Students’ reception towards MVL. The number on each segment of the bars indicates the number of students who have given a particular response to a given statement.

Almost all students also agreed that they find it easy to get MVL to perform what they want to do (Q7), and that the majority of the students had no problem with the learning materials in MVL (Q8).

For qualitative comments, some areas of improvement provided by students were that while in general MVL was accurate in detecting students’ hand gestures, the accuracy can still be finetuned for gestures that required finer motor controls such as pinching and hand rotations. Other common issues students faced include the weight of the VR headset, as well as the students not being able to see clearly if they are also wearing glasses underneath the VR headset.

6.10 Results discussion

As shown in Table 4, there is a statistically significant improvement in students’ understanding of laboratory safety protocol after using MVL. Students’ perception on their understanding also supported this as all students agreed that MVL helped in enhancing their understanding of laboratory safety (Q5 as shown in Figure 8). The authors hypothesized that the use of conceptualization of laboratory safety protocol as well as the problem solving with contextualization could help in scaffolding of concepts (Broman et al., 2018). This hypothesis is supported by some of the qualitative comments provided by students. For instance, one student commented that MVL provided various simulations on laboratory emergencies, this helped them to understand the concept better than merely reading the text-based safety protocol. In addition, the introduction of the laboratory safety protocol as a need-to-know approach also helped students in understanding the utility in learning them. This is supported by the qualitative comments from students where they mentioned that without the training from MVL, they will not be able to respond to real laboratory emergencies calmly.

Although most of the students have positive perception of MVL, three students surveyed felt that MVL requires a lot of mental effort as seen in Q2 of Figure 8. The authors believed that these students could have experienced both visual fatigue and cognitive overload while using MVL. Visual fatigue could occur due to the vergence-accommodation conflict (VAC) where there is a mismatch in the perception of perceived depth and virtual depth while perceiving the 3D environment through the HMDs (Hua, 2017). The symptoms of visual fatigue includes eye strain, and double vision (Iskander et al., 2018). High cognitive load can occur when the students have to do complex hand gestures in MVL that may be difficult for the HMD to detect such as pouring and grabbing of virtual items, as well as having to interact with many of the virtual items in MVL (Frederiksen et al., 2020). Some of the qualitative feedback provided by students did reflect that they found some of the hand gestures used in MVL to be complicated, while others felt that the hand detection system in MVL required some refinement. In addition, as all of the students were new to MVL, higher cognitive load was needed for visuomotor adaptation to occur (Juliano et al., 2022). Thus, the authors hypothesized that the combination of visual fatigue, and cognitive overload, could induce some students to feel that more mental effort was required to operate MVL.

7 SR recommended practices

What are some of the recommended practices of VR that the authors have learnt throughout their journey in using SL in education?

Providing proper context in the learning material is important as it can help students to scaffold their learning and link concepts to real life situations (Broman et al., 2018). As demonstrated by MVL through the various context-based laboratory emergencies simulations, students reported learning better as well as showed statistically significant improvements when tested on their knowledge after using MVL. Thus, this is in line with the first tenet of MCE.

It is essential to have Students as Partners when creating VR experience for education. Students as partners is defined as the collaborative and mutually beneficial process where all parties in the group can contribute equally, albeit in different forms, to the development, implementation, and evaluation of curriculum and teaching methods (Cook-Sather et al., 2014). Students, being the “acquirer of knowledge” from teachers, possess unique insights of teaching and learning that educators may otherwise pick up (Cook-Sather, 2016). Thus, students can provide their perspective to educators on some of the learning struggles that they faced and suggest solutions to mitigate the problems. In the case of VR water supply, VR crime scene and VR excursions, the students involved in the team were former students who had prior experience with the course materials as well as sentiments from their peers. They were hired to the team as part time research assistants and were heavily involved in the planning and filming of the VR experience while the educators incorporated the insights gained from working with the students in designing the overall VR experience. Thus, students’ opinions were being heard, which helped to improve the learning experience of future cohorts of students taking the same course.

To create an advanced VR experience akin to the metaverse, such as MVL, collaboration with a team of collegial VR professionals is essential. This team should comprise expert storyboard artists, product experience designers, and software engineers, who possess the skills necessary to design a coherent, cohesive and user-friendly VR environment. As van Dinther et al. (2023) noted, a well-defined storyboard and learning goals are important as they can affect the students’ experience in SL, the educator’s role is also pivotal in this process, as they contribute to design of learning goals, provide domain-specific knowledge and ensure the accuracy of the educational content integrated by the VR team. Effective communication between educators and VR specialists is paramount for successful implementation. Regular meetings should be scheduled to facilitate dialogue, and the use of visual aids and online collaboration tools can enhance understanding and project tracking for all team members.

For both basic and advanced VR experiences, it is crucial to comprehend the challenges that end-users encounter when engaging with VR elements. Educators can delve into literature that explores students’ perceptions of VR to acquire valuable insights. This research can help them predict potential difficulties that students may face during VR usage and lower teaching anxiety using technology. Moreover, educators can leverage these insights to design VR experiences that mitigate the reported obstacles, thereby enhancing the overall learning experience for students.

From our seven years of experiences (2017–2024), the recommended practices for VR are distilled and summarized as follows:

Contextualization of learning content.

Engage Students as Partners.

Understand the learning challenges faced by students from their perspective.

Hire professionals to conduct storyboarding and UI/UX design if resources permit.

Involve educators as key subject matter experts for VR educational contents.

Promote effective communications between educators and VR professionals.

Understand the end-users pain points when using VR.

8 Conclusions

In conclusion, the authors have shared their multifaceted experiences spanning seven years in utilizing SR technologies as an instructional tool across various chemistry disciplines, how they incorporated aspects of MCE when designing and utilizing SR technologies, as well as insights into students’ perceptions of these technologies within their educational journey. Moreover, the paper aims to address the concerns that many educators may have regarding the adoption of VR in teaching. Finally, the authors also provided their recommendations on how to create and apply SR technologies based on their seven years of using those SR technologies as instructional tools for chemistry. By disseminating the recommended practices in VR that they have mastered through their endeavors to integrate SR technologies into the curriculum, the authors not only offer a roadmap for successful implementation but also instill confidence in educators to embrace this transformative technology. By doing so, the authors hoped that readers can understand that designing and implementing SR technologies into their curriculum do not require advanced technical skillsets, thus reducing the teaching anxiety that were reported by various educators in using such technologies thereby enriching the educational landscape with innovative and engaging learning experiences.

Funding source: Ministry of Education – Singapore

Award Identifier / Grant number: GAP502024-04-01

Acknowledgments

The authors expressed their gratitude to the NUS InterReality Technologies Team for their support in co-conceptualizing and co-creating MyVirtualLab (MVL), supported by the NUS IT Steering Committee via the PPM Exercise (WBS E-051-00-8153-01), with author F.M.F. as the Chemistry PI. We are grateful to Dr. S.C. Pan for his assistance in conducting the study with the postgraduate students, A/P Lam YL for supporting the MVL project (Chemistry part) and A/P Yeong FM (Biochemistry PI). Further, the authors acknowledge the support by NUS GAP Funding (RIE2025): GAP502024-04-01 (WBS A-8002383-00-00). Finally, we would like to congratulate the host and various committees for hosting the successful ICCE2024 conference in Pattaya, Thailand.

-

Research ethics: The study received ethics board approval (Departmental Ethics Review Committee (DERC), reference ID “Psych-DERC reference code: 2024-March-03”) prior to the start of the research.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: MyVirtualLab was funded by the NUS IT Steering Committee via the PPM Exercise (WBS E-051-00-8153-01). This research was partially supported by NUS GAP Funding (RIE2025): GAP502024-04-01 (WBS A-8002383-00-00).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Al-Ansi, A. M., Jaboob, M., Garad, A., & Al-Ansi, A. (2023). Analyzing augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) recent development in education. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100532.Search in Google Scholar

Broman, K., Bernholt, S., & Parchmann, I. (2018). Using model-based scaffolds to support students solving context-based chemistry problems. International Journal of Science Education, 40(10), 1176–1197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1470350.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, C. E., Alrmuny, D., Williams, M. K., Whaley, B., & Hyslop, R. M. (2021). Visualizing molecular structures and shapes: A comparison of virtual reality, computer simulation, and traditional modeling. Chemistry Teacher International, 3(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2019-0009.Search in Google Scholar

Broyer, R. M., Miller, K., Ramachandran, S., Fu, S., Howell, K., & Cutchin, S. (2021). Using virtual reality to demonstrate glove hygiene in introductory chemistry laboratories. Journal of Chemical Education, 98(1), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00137.Search in Google Scholar

Conrad, M., Kablitz, D., & Schumann, S. (2024). Learning effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in education and training: A systematic review of findings. Computers & Education: X Reality, 4, 100053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cexr.2024.100053.Search in Google Scholar

Cook-Sather, A. (2016). Learning from the student’s perspective: A sourcebook for effective teaching. Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.Search in Google Scholar

Czok, V., Krug, M., Müller, S., Huwer, J., Kruse, S., Müller, W., & Weitzel, H. (2023). A framework for analysis and development of augmented reality applications in science and engineering teaching. Education Sciences, 13(9), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090926.Search in Google Scholar

Dhar, E., Upadhyay, U., Huang, Y., Uddin, M., Manias, G., Kyriazis, D., Wajid, U., AlShawaf, H., & Syed Abdul, S. (2023). A scoping review to assess the effects of virtual reality in medical education and clinical care. Digital Health, 9, 20552076231158022. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076231158022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

van Dinther, R., de Putter, L., & Pepin, B. (2023). Features of immersive virtual reality to support meaningful chemistry education. Journal of Chemical Education, 100(4), 1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c01069.Search in Google Scholar

Frederiksen, J. G., Sørensen, S. M. D., Konge, L., Svendsen, M. B. S., Nobel-Jørgensen, M., Bjerrum, F., & Andersen, S. A. W. (2020). Cognitive load and performance in immersive virtual reality versus conventional virtual reality simulation training of laparoscopic surgery: A randomized trial. Surgical Endoscopy, 34(3), 1244–1252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06887-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Frevert, M., & Di Fuccia, D.-S. (2020). Possibilities of learning contemporary chemistry via virtual reality. World Journal of Chemical Education, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.12691/wjce-9-1-1.Search in Google Scholar

Fung, F. M., Choo, W. Y., Ardisara, A., Zimmermann, C. D., Watts, S., Koscielniak, T., Blanc, E., Coumoul, X., & Dumke, R. (2019). Applying a virtual reality platform in environmental chemistry education to conduct a field trip to an overseas site. Journal of Chemical Education, 96(2), 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00728.Search in Google Scholar

Gallion, L. A., Samide, M. J., & Wilson, A. M. (2015). Demonstrating the importance of cleanliness and safety in an undergraduate teaching laboratory. Journal of Chemical Health & Safety, 22(5), 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchas.2015.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

Gao, S., Lu, Y., Ooi, C. H., Cai, Y., & Gunawan, P. (2023). Designing interactive augmented reality application for student’s directed learning of continuous distillation process. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 169, 108086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2022.108086.Search in Google Scholar

Gorospe, J. D. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ teaching anxiety, teaching self-efficacy, and problems encountered during the practice teaching course. Journal of Education and Learning, 11(4), 84. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v11n4p84.Search in Google Scholar

Han, J. Y., & Fung, F. M. (2023). Applications of digital technology in chemical education. https://books.rsc.org/books/edited-volume/2075/chapter/7621041/Applications-of-Digital-Technology-in-Chemical [Accessed 3 March 2024].10.1039/9781839167942-00205Search in Google Scholar

Holden, H., & Rada, R. (2011). Understanding the influence of perceived usability and technology self-efficacy on teachers’ technology acceptance. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(4), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2011.10782576.Search in Google Scholar

Hsieh, P.-H. P., & Schallert, D. L. (2008). Implications from self-efficacy and attribution theories for an understanding of undergraduates’ motivation in a foreign language course. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(4), 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

Hua, H. (2017). Enabling focus cues in head-mounted displays. Proceedings of the IEEE, 105(5), 805–824. https://doi.org/10.1109/jproc.2017.2648796.Search in Google Scholar

Iskander, J., Hossny, M., & Nahavandi, S. (2018). A review on ocular biomechanic models for assessing visual fatigue in virtual reality. IEEE Access, 6, 19345–19361. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2018.2815663.Search in Google Scholar

Juliano, J. M., Schweighofer, N., & Liew, S.-L. (2022). Increased cognitive load in immersive virtual reality during visuomotor adaptation is associated with decreased long-term retention and context transfer. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 19(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-022-01084-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kader, S. N., Ng, W. B., Tan, S. W. L., & Fung, F. M. (2020). Building an interactive immersive virtual reality crime scene for future chemists to learn forensic science chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 2651–2656. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00817.Search in Google Scholar

Kardong-Edgren, S., Farra, S. L., Alinier, G., & Young, H. M. (2019). A call to unify definitions of virtual reality. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 31, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2019.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

Koscielniak, T. (2021). A review of immersive learning technologies featured at EDUCAUSE annual conferences: Evolution since 2016. In Technology-enabled blended learning experiences for chemistry education and outreach (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 163–184). Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-12-822879-1.00011-1Search in Google Scholar

Laato, S., Xi, N., Spors, V., Thibault, M., & Hamari, J. (2024). Making sense of reality: A mapping of terminology related to virtual reality, augmented reality, mixed reality, XR and the metaverse. Presented at the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/107179 [Accessed 16 October 2024].10.24251/HICSS.2024.793Search in Google Scholar

Lee, H. L. (2020). PMO | PM Lee Hsien Loong on the COVID-19 situation in Singapore on 14 December 2020. Prime Minister’s Office Singapore. Text, katherine_chen. https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/PM-Lee-Hsien-Loong-on-the-COVID-19-situation-in-Singapore-on-14-December-2020 [Accessed 23 August 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Li, L., & Wang, X. (2021). Technostress inhibitors and creators and their impacts on university teachers’ work performance in higher education. Cognition, Technology & Work, 23(2), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-020-00625-0.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, B., Ding, L., & Meng, L. (2021). Spatial learning with extended reality – a review of user studies. In 2021 7th international conference of the immersive learning research network (iLRN) (pp. 1–5). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9459374/?arnumber=9459374 [Accessed 14 October 2024].10.23919/iLRN52045.2021.9459374Search in Google Scholar

Milgram, P., Takemura, H., Utsumi, A., & Kishino, F. (1995). Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. In H. Das (Ed.), Presented at the Photonics for Industrial Applications (pp. 282–292). http://proceedings.spiedigitallibrary.org/proceeding.aspx?articleid=981543 [Accessed 4 October 2024].10.1117/12.197321Search in Google Scholar

Miro. (n.d.). Miro | the innovation workspace. https://miro.com/ [Accessed 23 August 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Mulquin, C. (2024). What is spatial learning? – XR definitions. Uptale. https://www.uptale.io/en/definition-of-spatial-learning/ [Accessed 24 August 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Myers, D., Sugai, G., Simonsen, B., & Freeman, J. (2017). Assessing teachers’ behavior support skills. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417700964.Search in Google Scholar

Ng, B. J. M., Han, J. Y., Kim, Y., Togo, K. A., Chew, J. Y., Lam, Y., & Fung, F. M. (2022). Supporting social and learning presence in the revised community of inquiry framework for hybrid learning. Journal of Chemical Education, 99(2), 708–714. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00842.Search in Google Scholar

Ntakakis, G., Plomariti, C., Frantzidis, C., Antoniou, P. E., Bamidis, P. D., & Tsoulfas, G. (2023). Exploring the use of virtual reality in surgical education. World Journal of Transplantation, 13(2), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v13.i2.36.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pangsapa, P., Yun Wong, P. P., Wai Chung Wong, G., Techanamurthy, U., Wan Mohamad, W. S., & Shen Jiandong, D. (2023). Enhancing humanities learning with metaverse technology: A study on student engagement and performance. In 2023 11th international conference on information and education technology (ICIET) (pp. 251–255). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10111125/?arnumber=10111125 [Accessed 20 August 2024].10.1109/ICIET56899.2023.10111125Search in Google Scholar

Park, S., & Lee, G. (2020). Full-immersion virtual reality: Adverse effects related to static balance. Neuroscience Letters, 733, 134974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2020.134974.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Parmaxi, A. (2023). Virtual reality in language learning: A systematic review and implications for research and practice. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(1), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1765392.Search in Google Scholar

Photon. (n.d.). Photon unity networking for unity multiplayer games | PUN2. Photon. https://www.photonengine.com/pun [Accessed 29 August 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Pimpasri, C., & Limpanuparb, T. (2024). From plastic models to virtual reality headsets: Enhancing molecular structure education for undergraduate students. Chimia, 78(6), 439–442. https://doi.org/10.2533/chimia.2024.439.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ritterbusch, G. D., & Teichmann, M. R. (2023). Defining the metaverse: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access, 11, 12368–12377. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3241809.Search in Google Scholar

Rodríguez, F. J. C., Frattini, G., Meireles, F. T. P., Terrien, D. A., Cruz-León, S., Peraro, M. D., Schier, E., Lindorff-Larsen, K., Limpanuparb, T., Moreno, & Abriata, L. A. (2023). MolecularWebXR: Multiuser discussions about chemistry and biology in immersive and inclusive VR. biorxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.01.564623.Search in Google Scholar

Roettl, J., & Terlutter, R. (2018). The same video game in 2D, 3D or virtual reality – how does technology impact game evaluation and brand placements? PLoS One, 13(7), e0200724. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200724.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Schroeder, R. (1996). Possible worlds: The social dynamic of virtual reality technology. Westview Press, Inc.Search in Google Scholar

Seery, M. K., Agustian, H. Y., Christiansen, F. V., Gammelgaard, B., & Malm, R. H. (2024). 10 guiding principles for learning in the laboratory. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 25(2), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3rp00245d.Search in Google Scholar

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246). https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748.Search in Google Scholar

Uptale. (n.d.). VR for education—design immersive learning experiences for students. Uptale. https://www.uptale.io/en/education/ [Accessed 23 August 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Uptale-Water Sampling. (n.d.). https://my.uptale.io/Experience/Launch?id=GkhqTJG4kalOMbGPZhQg [Accessed 3 October 2024].Search in Google Scholar

VR Crime Scene (TRIAL). (n.d.). https://my.uptale.io/experience/LaunchPage?id=DKFWl6q2Ua1RTUJGuQg [Accessed 3 October 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Q., & Zhao, G. (2023). Exploring the influence of technostress creators on in-service teachers’ attitudes toward ICT and ICT adoption intentions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(6), 1771–1789. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13315.Search in Google Scholar

Westbroek, H., Klassen, K., Bulte, A., & Pilot, A. (2005). Characteristics of meaningful chemistry education. In European Science Education Research Association (Ed.), Research and the quality of science education. Springer.10.1007/1-4020-3673-6_6Search in Google Scholar

World Bank. (n.d.). Remote learning during COVID-19: Lessons from today, principles for tomorrow. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic [Accessed 25 August 2024].Search in Google Scholar

Wu, B., Yu, X., & Gu, X. (2020). Effectiveness of immersive virtual reality using head-mounted displays on learning performance: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 1991–2005. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13023.Search in Google Scholar

Zhong, Z., Feng, S., & Jin, S. (2024). Investigating the influencing factors of teaching anxiety in virtual reality environments. Education and Information Technologies, 29(7), 8369–8391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-12152-2.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 27th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education (ICCE 2024)

- Special Issue Papers

- Recent advances in laboratory education research

- Examining the effect of categorized versus uncategorized homework on test performance of general chemistry students

- Enhancing chemical security and safety in the education sector: a pilot study at the university of Zakho and Koya University as an initiative for Kurdistan’s Universities-Iraq

- Leveraging virtual reality to enhance laboratory safety and security inspection training

- Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in college chemistry

- High school students’ perceived performance and relevance of chemistry learning competencies to sustainable development, action competence, and critical thinking disposition

- Spatial reality in education – approaches from innovation experiences in Singapore

- Teachers’ perceptions and design of small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

- Electricity from saccharide-based galvanic cell

- pH scale. An experimental approach to the math behind the pH chemistry

- Engaging chemistry teachers with inquiry/investigatory based experimental modules for undergraduate chemistry laboratory education

- Reasoning in chemistry teacher education

- Development of the concept-process model and metacognition via FAR analogy-based learning approach in the topic of metabolism among second-year undergraduates

- Synthesis of magnetic ionic liquids and teaching materials: practice in a science fair

- The development of standards & guidelines for undergraduate chemistry education

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 27th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education (ICCE 2024)

- Special Issue Papers

- Recent advances in laboratory education research

- Examining the effect of categorized versus uncategorized homework on test performance of general chemistry students

- Enhancing chemical security and safety in the education sector: a pilot study at the university of Zakho and Koya University as an initiative for Kurdistan’s Universities-Iraq

- Leveraging virtual reality to enhance laboratory safety and security inspection training

- Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in college chemistry

- High school students’ perceived performance and relevance of chemistry learning competencies to sustainable development, action competence, and critical thinking disposition

- Spatial reality in education – approaches from innovation experiences in Singapore

- Teachers’ perceptions and design of small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

- Electricity from saccharide-based galvanic cell

- pH scale. An experimental approach to the math behind the pH chemistry

- Engaging chemistry teachers with inquiry/investigatory based experimental modules for undergraduate chemistry laboratory education

- Reasoning in chemistry teacher education

- Development of the concept-process model and metacognition via FAR analogy-based learning approach in the topic of metabolism among second-year undergraduates

- Synthesis of magnetic ionic liquids and teaching materials: practice in a science fair

- The development of standards & guidelines for undergraduate chemistry education