Abstract

This qualitative study investigates how teachers perceive and design Small-Scale Chemistry driven STEM Learning Activities (SSC-STEM) in their teaching practice. While small-scale chemistry experiments offer numerous advantages for chemistry education, there is limited research on their integration into STEM education frameworks. This study examined teachers’ understanding, perceptions, and lesson design practices when implementing SSC-STEM activities. Fifty teachers from Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines participated in SSC-STEM training. Data were collected through questionnaires that explored teachers’ perceptions and analyzed their STEM lesson designs. The findings reveal that teachers demonstrate positive perceptions of SSC-STEM, particularly regarding its potential to foster STEM literacy and environmental consciousness. The analysis of lesson designs showed the successful integration of small-scale chemistry experiments with real-world environmental challenges, although teachers faced challenges in certain implementation aspects. High scores in teamwork (4.63) and self-directed learning (4.73) contrasted with lower scores in teaching performance (2.88) and teaching strategies (2.94), indicating areas needing professional development support. This study contributes to the understanding of how small-scale chemistry can be effectively integrated into STEM education while promoting sustainable development practices. These findings provide insights for teacher preparation programs and curriculum development for implementing integrated STEM approaches using small-scale chemistry experiments.

1 Introduction

The integration of small-scale chemistry (SSC) experiments within an STEM framework for sustainable development (SD) is an emerging area of research that holds significant promise in addressing global challenges and promoting scientific literacy. The literature highlights the potential of SSC to enhance student learning, engagement, and environmental responsibility, while overcoming resource limitations and safety concerns. Small-Scale Chemistry (SSC), also referred to as microscale chemistry, involves conducting experiments using reduced quantities of chemicals and often simpler equipment. This approach offers numerous advantages, including cost savings, reduced waste generation, enhanced safety, and increased accessibility to resource-constrained settings (du Toit & du Toit, 2024; Listyarini et al., 2019; Tesfamariam et al., 2014).

Research suggests that SSC can effectively promote student learning and engagement. Studies have shown that SSC can enhance students’ understanding of chemical concepts, improve their practical skills, and foster positive attitudes towards science (Abdullah et al., 2009; Mafumiko et al., 2013; Tesfamariam et al., 2017). SSC aligns well with the principles of green chemistry, which aim to minimize the environmental impact of chemical processes. SSC contributes to a more sustainable approach to chemistry education by reducing chemical usage and waste generation (Duarte et al., 2017).

However, research on integrating small-scale chemistry laboratories in the context of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) education is limited. In this study, we developed a new framework that combines small-scale chemistry with green chemistry principles within STEM education. We examined how teachers incorporated small-scale chemistry laboratories into STEM learning activities. STEM education emphasizes the integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics to address complex real-world problems related to sustainability (Aydin-Gunbatar et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2021; Roehrig et al., 2021). This transdisciplinary approach fosters a holistic understanding of the sustainability challenges and encourages the development of innovative solutions. STEM education for SD focuses on engaging students in solving real-world problems related to sustainability such as climate change, resource depletion, and pollution. This approach enhances the relevance and meaningfulness of STEM learning, motivating students to apply their knowledge and skills to addressing global challenges. It aims to develop 21st-century skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, collaboration, communication, and digital literacy, which are essential for navigating the complexities of a sustainable future.

2 Research questions

What are the teachers’ perceptions of implementing small-scale chemistry-driven STEM Learning Activities?

How do teachers design small-scale chemistry-driven STEM Learning Activities?

3 Conceputal framework

The conceptual framework for this study is rooted in addressing the research gap of limited exploration of the integration of small-scale chemistry laboratories within STEM education. It recognizes the potential of small-scale chemistry to enhance safety, cost-effectiveness, and student engagement, while promoting sustainable practices through green chemistry principles.

3.1 Small-scale chemistry (SSC)

Small-scale chemistry, also known as microscale chemistry, is a laboratory-based approach that utilizes significantly reduced quantities of chemicals and reagents, often in the milligram or microliter range (Mohamed et al., 2012; Tesfamariam et al., 2014, 2017). This reduction in scale not only minimizes waste generation and costs but also enhances safety by limiting exposure to potentially hazardous substances. SSC frequently employs simpler and readily available equipment, making it particularly suitable for classrooms with limited resources.

SSC offers a multitude of advantages that make it a compelling approach to chemistry education. By utilizing significantly smaller quantities of chemicals and reagents, SSC drastically reduces waste generation and the associated disposal costs, aligning with the principles of green chemistry and promoting environmental sustainability (Mohamed et al., 2012). The inherent safety of SSC stems primarily from the reduced quantities of the chemicals used in the experiments. Although both glassware and alternative laboratory equipment can be used effectively in SSC, the key advantage lies in the smaller scale of operations rather than the choice of equipment materials. This reduced scale makes SSC particularly suitable for classrooms with varying levels of laboratory facilities, as it minimizes potential hazards and allows for the closer supervision of experimental work (Mohamed et al., 2012; Tesfamariam et al., 2014). Moreover, the SSC’s reliance on simpler and readily available equipment democratizes access to hands-on chemistry experiments, ensuring that practical learning opportunities are not limited by financial or infrastructural constraints (du Toit & du Toit, 2024; Listyarini et al., 2019; Tesfamariam et al., 2014). The reduced scale of SSC experiments often translates to faster reaction times and quicker completion of procedures, allowing for the efficient utilization of laboratory time and enabling students to conduct multiple experiments or explore variations within a single class period.

Beyond its practical benefits, SSC fosters a shift from rote memorization to a deeper conceptual understanding of chemical phenomena. By enabling students to conduct experiments individually or in small groups, it promotes active learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills (Abdullah et al., 2009; Mafumiko et al., 2013; Tesfamariam et al., 2017).This hands-on approach empowers students to take ownership of their learning, leading to an increased motivation and interest in science.

Research has consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating SSC with inquiry-based learning in enhancing student learning outcomes. Supasorn (2015) found that combining SSC experiments with a model kit, implemented through an 5E inquiry learning approach, significantly improved students’ conceptual understanding and mental models of galvanic cells. This approach emphasizes the importance of visualizing submicroscopic processes and connecting them to macroscopic observations and symbolic representations, thus facilitating the comprehension of complex electrochemical concepts. This study highlighted that traditional teaching methods alone may not be sufficient for students to fully grasp complex ideas at the molecular level, advocating for the incorporation of models, simulations, animations,or other visualization tools to facilitate understanding.

3.2 Integrated STEM

STEM education has emerged as a pivotal force in driving national progress, equipping individuals with the essential skills for success in the 21st-century workforce (National Research Council, 2011; NGSS Lead States, 2013). Beyond technical proficiency, contemporary education emphasizes higher-order thinking skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving, and creativity, alongside effective communication and technological literacy. The integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), both within the classroom and in real-world contexts, has become a central tenet of modern pedagogy. This approach strives to foster meaningful learning experiences, empowering students to apply their knowledge and actively contribute to society (Honey et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2021).

The STEM education movement champions a shift towards transdisciplinary integration, where STEM is perceived not as a mere aggregation of its constituent parts, but as a synergistic whole that empowers learners to tackle complex, real-world challenges (Roehrig et al., 2021). This approach necessitates a reevaluation of traditional disciplinary boundaries, fostering an environment in which students can seamlessly apply their knowledge and skills across domains.

Learning experiences are anchored in genuine challenges that students can relate to, making the content more relevant and meaningful (Capobianco et al., 2013). The Engineering Design Process (EDP) serves as a primary driver for learning activities, providing a structured framework through which students can approach complex problems systematically. This process naturally integrates multiple disciplines as students design, test, and refine solutions to real-world challenges (Moore et al., 2021).

Student-centered learning stands as a fundamental principle of integrated STEM education. This approach emphasizes active engagement, where students take ownership of their learning through collaborative problem-solving activities (Grubbs & Strimel, 2015). The learning environment must support various key characteristics including: focusing on student-centered learning, providing real-world contexts, incorporating conditions and constraints for designing solutions, using EDP as a driver of STEM activities, and fostering teamwork and communication throughout the engineering design process (Capobianco et al., 2013; Grubbs & Strimel, 2015).

According to the literature (Honey et al., 2014; Roehrig et al., 2021), the key features of integrated STEM education are:

A critical concept of interdisciplinary connections, where traditional subject-matter boundaries are deliberately broken down to create authentic learning experiences. This integration goes beyond simply combining subjects; it requires creating meaningful connections that help students understand how different disciplines naturally work together to solve complex problems. When students engage in engineering challenges, for instance, they naturally draw upon scientific principles, apply mathematical calculations, and utilize technological tools, reflecting the real-world practice of scientists and engineers where disciplinary boundaries often blur in pursuit of solutions.

A focus on real-world problem-solving, where learning is anchored in authentic challenges that matter to students and their communities. These problems must be relevant to students’ lives, connected to community or global issues, and sufficiently complex to require multiple disciplinary approaches. This real-world context not only provides natural motivation for learning but also helps students understand the practical applications of abstract concepts. Through addressing authentic challenges, students develop practical problem-solving skills that transfer beyond the classroom while seeing the immediate relevance of their learning.

Inquiry-based learning serves as a fundamental pedagogical approach in integrated STEM education. Students are encouraged to ask meaningful questions about natural phenomena, design and conduct investigations, analyze and interpret data, construct explanations based on evidence, and communicate their findings. This approach represents a significant shift from passive reception of information to active construction of understanding, aligning with authentic scientific and engineering practices. Through guided inquiry experiences, students simultaneously develop both content knowledge and scientific practices, learning to think and work like real STEM professionals.

The Engineering Design Process (EDP) provides a structured framework that naturally integrates multiple STEM disciplines while promoting systematic problem-solving approaches. This process guides students through problem identification, research, ideation, prototype development, testing, and iteration. Design thinking complements this process by emphasizing human-centered problem solving, iterative improvement, and creative solution generation. Together, these approaches help students develop both systematic problem-solving skills and creative thinking abilities essential for addressing complex challenges.

Integrated STEM education naturally develops critical 21st-century skills needed for success in the modern workforce. These include critical thinking and problem-solving abilities, creativity and innovation, collaboration and communication skills, and digital literacy. Students learn to analyze complex problems, generate novel solutions, work effectively in teams, and utilize technology tools productively. Rather than being taught in isolation, these skills are developed through integrated experiences that require their application in meaningful contexts.

3.3 Small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

The conceptual framework for Small-Scale Chemistry (SSC)-driven STEM Learning Activities (SSC-STEM) is built on two fundamental theoretical foundations: Small-Scale Chemistry and integrated STEM. This integrated framework provides a comprehensive approach for understanding and implementing chemistry education that goes beyond traditional classroom boundaries to create meaningful societal impacts. SSC provides a foundational element of the framework, offering a structured approach to addressing global challenges and creating a comprehensive roadmap for addressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Within the context of SSC-STEM, the SDGs serve as both guiding principles and assessment metrics, helping align educational objectives with broader sustainable development targets.

The framework is operationalized through four core principles that shape its implementation. First, real-world problem solving is a central component, emphasizing the importance of applying STEM knowledge and skills to address tangible challenges. In small-scale chemistry, this manifests through the identification and solving of problems, leading to the creation of innovative experiments and products that address societal and environmental issues.

Interdisciplinary thinking forms the second core principle, recognizing that complex problems require integrated solutions. This approach combines knowledge from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics while also incorporating business and marketing perspectives when relevant. By encouraging students to think across disciplinary boundaries, this framework promotes the development of holistic solutions to real-world challenges.

Innovation and creativity constitute the third principle that fosters the development of novel solutions to complex problems. In the context of Small-Scale Chemistry, this involves generating new ideas for chemistry products and processes, while finding creative ways to address social and environmental issues. This principle emphasizes the importance of thinking outside conventional boundaries and developing original approaches to problem solving.

The fourth principle, collaboration and teamwork, emphasizes the collective nature of effective problem solving. This principle recognizes that meaningful change often requires coordinated efforts and diverse perspectives. Through collaborative activities, students learn to work effectively with others, share knowledge, and create positive changes in their community.

The implementation of this framework is guided by transformative learning questions that help educators and students to navigate the learning process. How does the activity empower students as agents of change? What knowledge and skills are being developed to address the sustainability challenges? How are critical thinking and problem solving fostered? These questions ensure that activities are aligned with both educational objectives and broader societal goals.

This framework anticipates both individual and broader societal outcomes. At the individual level, students developed enhanced STEM knowledge and skills, improved problem-solving capabilities, and a stronger sense of social responsibility and global citizenship. At the community level, the framework aims to contribute to environmental protection, economic development, and social progress, directly supporting the achievement of the specific SDGs.

Through this comprehensive approach, the framework provides a structure for implementing SSC-STEM that not only enhances students’ understanding of chemistry and STEM concepts, but also contributes to broader sustainable development goals. This creates a bridge between classroom learning and real-world impact, empowering students to become active participants in creating a more sustainable future.

The following five-step implementation guide provides a structured approach for designing and executing SSC-STEM that maximizes both educational value and environmental impact. Each step builds upon the previous one, creating a comprehensive learning experience that connects laboratory work with community needs and development goals.

Step 1: Selecting the Right Small-Scale Lab

The initial step focused on selecting experiments that aligned with both green chemistry principles and educational goals. Priority should be given to experiments using safe, readily available materials while demonstrating core concepts, such as waste reduction and renewable resource use. The selected experiment must be connected to real-world environmental issues relevant to the student community. For instance, an experiment on natural water filtration methods can directly address local water quality concerns, making the learning experience relevant and applicable.

Step 2: Identifying Core Concepts and Green Chemistry Connections

Once the experiment is selected, the key scientific principles that students will explore, such as chemical reactions or the properties of matter. These principles should be explicitly connected to the broader concepts of green chemistry. For example, in a bioplastic synthesis experiment, the process used renewable resources to produce biodegradable materials. Guide the students to consider the potential environmental impact of the experiment and its connection to larger systems.

Step 3: Surveying Community Needs and Connecting to the Lab

Ground the laboratory experience in real-world relevance by surveying local community environmental challenges through student-led surveys, interviews, or field trips. The analysis of these data should reveal patterns and potential solutions that connect to the chosen experiment. For example, if surveys indicate soil contamination concerns, a laboratory investigating composting methods could provide practical solutions while demonstrating scientific principles in action.

Step 4: Designing a Real-World Challenge with Clear Criteria

Present students with realistic environmental challenges related to their lab work and community needs. We define specific success criteria that consider multiple factors such as cost-effectiveness, ease of use, and technical effectiveness. Encourage collaborative problem-solving, allowing students to work together to develop test solutions. This challenge should demonstrate how laboratory learning can address practical environmental issues while considering real-world constraints.

Step 5: Defining Learning Outcomes and Assessing Understanding

Establish SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) learning objectives that align with the experiment and real-world challenges. Various assessment methods have been used, including lab reports, presentations, and design challenges. Provide opportunities for students to reflect on their learning process and the potential impact of their solutions, helping them recognize their capacity to contribute to environmental sustainability through scientific investigation.

3.4 Teacher planned pedagogical content knoweldge (pPCK) for teaching chemistry

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) serves as a crucial analytical lens in our study, particularly in understanding how teachers design and implement small-scale chemistry-driven STEM Learning Activities. The integration of small-scale chemistry with STEM education presents a complex pesdagogical challenge that requires teachers to possess and apply specific knowledge domains (Saxton et al., 2014). PCK provides a structured framework for examining how teachers navigate this complexity, make instructional decisions, and translate theoretical understanding into practical classroom activities (Aydin-Gunbatar et al., 2020; Goes & Fernandez, 2023; Van Driel et al., 2002).

The ability to effectively design and implement instructional strategies to promote student learning is a hallmark of proficient teaching. In chemistry education, this ability is closely tied to a teacher’s pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), a specialized form of knowledge that intertwines subject matter expertise with pedagogical understanding (Shulman, 1986, 1987; Van Driel et al., 2002). The concept of PCK has since been widely explored and refined, leading to the development of various models and frameworks to elucidate its complex nature. For instance, the Refined Consensus Model (RCM) of PCK offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of PCK and its role in teacher practice (Carlson & Daehler, 2019; Carpendale & Hume, 2019). The RCM emphasizes the dynamic interplay between various knowledge domains, including knowledge of content and students, curriculum and assessment, and instructional strategies, highlighting the interconnectedness of these domains in shaping effective teaching practices.

One crucial aspect of PCK is its topic-specific nature, recognizing that effective teaching requires a deep understanding of not only the subject matter itself, but also the specific challenges and opportunities associated with teaching particular topics within the discipline (Mavhunga, 2020). In the context of chemistry education, this translates to teachers possessing a profound understanding of specific concepts, misconceptions, and instructional strategies pertinent to teaching various chemistry topics (Goes & Fernandez, 2023). The importance of topic-specific PCK has been further underscored by studies that have highlighted the challenges associated with transferring PCK across different topics, even within the same discipline (Lertdechapat & Faikhamta, 2021; Mavhunga et al., 2016). These studies suggest that effective chemistry instruction requires teachers to possess a deep and nuanced understanding of the specific pedagogical challenges and opportunities associated with each topic.

The planned pedagogical content knowledge (pPCK) construct focuses on the knowledge and reasoning that teachers employ during the planning phase of instruction (Aydeniz & Kirbulut, 2014; Carpendale & Hume, 2019; Park & Oliver, 2008). It encompasses the decisions teachers make regarding the selection and sequencing of content, anticipation of student difficulties, and design of instructional strategies to facilitate student learning. The pPCK construct is particularly relevant for understanding how teachers design chemistry lessons, as it sheds light on the cognitive processes and knowledge resources that inform their instructional choices. Research on pPCK in chemistry education has revealed that effective lesson planning involves a complex interplay of various knowledge components, including knowledge of learners, curriculum, instructional strategies, and assessment (Akın & Uzuntiryaki-Kondakci, 2018; Park & Chen, 2012).

The literature on pPCK in chemistry education highlights the critical role of teaching experience in its development and refinement (Carpendale & Hume, 2019). As teachers gain experience, they accumulate a wealth of knowledge regarding student learning, curricular demands,and effective instructional strategies that can be leveraged during lesson planning. For instance, experienced teachers are more likely to anticipate student difficulties and misconceptions and design lessons that proactively address these challenges. This suggests that the development of pPCK is an ongoing process shaped by teachers’ classroom experiences.

Recent research on PCK in STEM education emphasizes the importance of integrated understanding across disciplines, with studies by Aydin-Gunbatar et al., (2020) and Lertdechapat and Faikhamta (2021) highlighting how teachers’ PCK influences their ability to connect science concepts with broader STEM applications. This integration becomes particularly crucial in the context of small-scale chemistry experiments and STEM education, where teachers must effectively combine content knowledge with pedagogical strategies. Aydin-Gunbatar et al. (2020) investigated how a research-based training program contributed to pre-service teachers’ PCK development for integrated STEM education. Their study revealed that the training program significantly improved participants’ PCK through emphasis on subject matter knowledge (SMK), active participation in learning activities, mentoring, and reflection. Their study demonstrate that teachers’ PCK significantly impacts their effectiveness in implementing innovative teaching approaches in STEM contexts, particularly when connecting laboratory experiences to real-world applications.

The development of pPCK specific to SSC-STEM involves understanding how to scaffold small-scale chemistry experiments, connect chemistry concepts with other STEM disciplines, address student misconceptions, and promote environmental consciousness through chemistry. This conceptual framework helps explain the gaps we observed between teachers’ theoretical understanding and practical implementation of SSC-STEM activities, suggesting specific areas where professional development support might be most beneficial.

4 Methodology

This study employed a qualitative research approach to examine teachers’ perceptions and lesson design practices in the implementation of SSC-STEM. A qualitative methodology was chosen for its ability to provide rich and detailed insights into teachers’ understanding and implementation practices (Creswell & Poth, 2016). The study involved 50 teachers from Thailand, Sri Lanka, and the Philippines who participated in training sessions focused on integrating small-scale chemistry laboratories into STEM learning activities. The framework was developed and implemented through teacher training sessions that cover various aspects, including green chemistry principles, STEM education, design-based learning, project-based learning, context-based learning, perceptions of integrated learning, and future learner capacity. Teachers are guided in designing STEM learning activities that incorporate Small-Scale Chemistry experiments and align with green chemistry principles, as mentioned in the section on small-scale chemistry-driven STEM Learning Activities (Table 1).

Examples of SSC-STEM activities.

| Activity name | Hazard capturer | Sensorial aroma experience |

|---|---|---|

| Core concept | Detection and capture of acidic and CO2 pollutants | Diffusion of molecules in different media (air and solvent) |

| Real-world problem | Air pollution from factories impacting local communities | Need for innovative and engaging aroma diffuser products |

| Challenge/task | Develop prototypes of solutions to capture/absorb pollutants (acidity absorbents, carbon capture, protective roofs) | Investigate diffuser materials, design new products with enhanced sensory features, develop color-changing diffuser sticks |

| Small-scale experiment | Detecting CO2 with limewater, detecting acidity with pH indicators, experimenting with CO2 absorption and acid neutralization | Comparing diffuser materials, creating color-changing diffuser sticks, investigating temperature’s effect on diffusion |

| STEM integration – science | Chemistry of acids and bases, properties of CO2, environmental pollution | Diffusion, factors affecting diffusion rate (temperature, medium) |

| STEM integration – technology | Research and utilize pollution capture/absorption technologies, air quality monitoring sensors | Research aroma diffusion technologies (ultrasonic, nebulizers), sensors for aroma concentration |

| STEM integration – engineering | Design, build, and test prototypes of pollution capture/absorption solutions | Design and create prototypes of aroma diffusers or diffuser sticks with specific features |

| STEM integration – mathematics | Measurements, calculations, and data analysis related to pollutant levels and solution effectiveness | Measurements, calculations, and data analysis related to diffusion rates and aroma concentration |

| Learning outcomes | Understand acid-base chemistry and its environmental impact, apply engineering design to an environmental challenge | Understand diffusion and its applications, design innovative aroma diffuser products |

The data collection involved two primary instruments: qualitative questionnaires and lesson design documents. The qualitative questionnaire was developed following Patton’s guidelines for open-ended questioning and designed to explore teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and challenges in implementing SSC-STEM activities. The questionnaire items were structured to probe teachers’ understanding of learners, teaching orientations, and implementation strategies, allowing participants to provide detailed responses regarding their experiences and perspectives. This approach aligns with Maxwell’s (2013) emphasis on gathering rich descriptive data that capture participants’ authentic voices and experiences.

The document analysis of teacher-created lesson designs served as the second data source. This method was particularly suitable for examining how teachers translated their understanding of SS-STEM into practical classroom activity. Lesson designs were collected and analyzed as authentic artifacts of teacher practice, providing insights into their pedagogical decision-making and implementation strategies.

4.1 Questionnaires

The questionnaires assessed teachers’ perceptions of teaching small-scale STEM, specifically focusing on learners, teaching strategies, and their own teaching performance. It consisted of items that explored various aspects of small-scale STEM education, such as student collaboration, problem solving, self-directed learning, use of technology, and teachers’ confidence in their abilities. The Likert-type scale responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics to understand teachers’ overall perceptions and identify areas of strength and concern. Open-ended responses were coded and categorized based on themes such as teamwork, problem-solving, self-directed learning, difficulties, improving STEM activities, evidence-based practice, embedded technology, designing SSC-STEM, step-strategies, and teaching performance. The questionnaires were validated to ensure data quality and trustworthiness. The questionnaire was validated through five expert reviews. Construct validity was established through alignment with established theoretical frameworks. Pilot testing with teachers helped to refine the instruments and confirm their cultural appropriateness and clarity.

4.2 Lesson designs

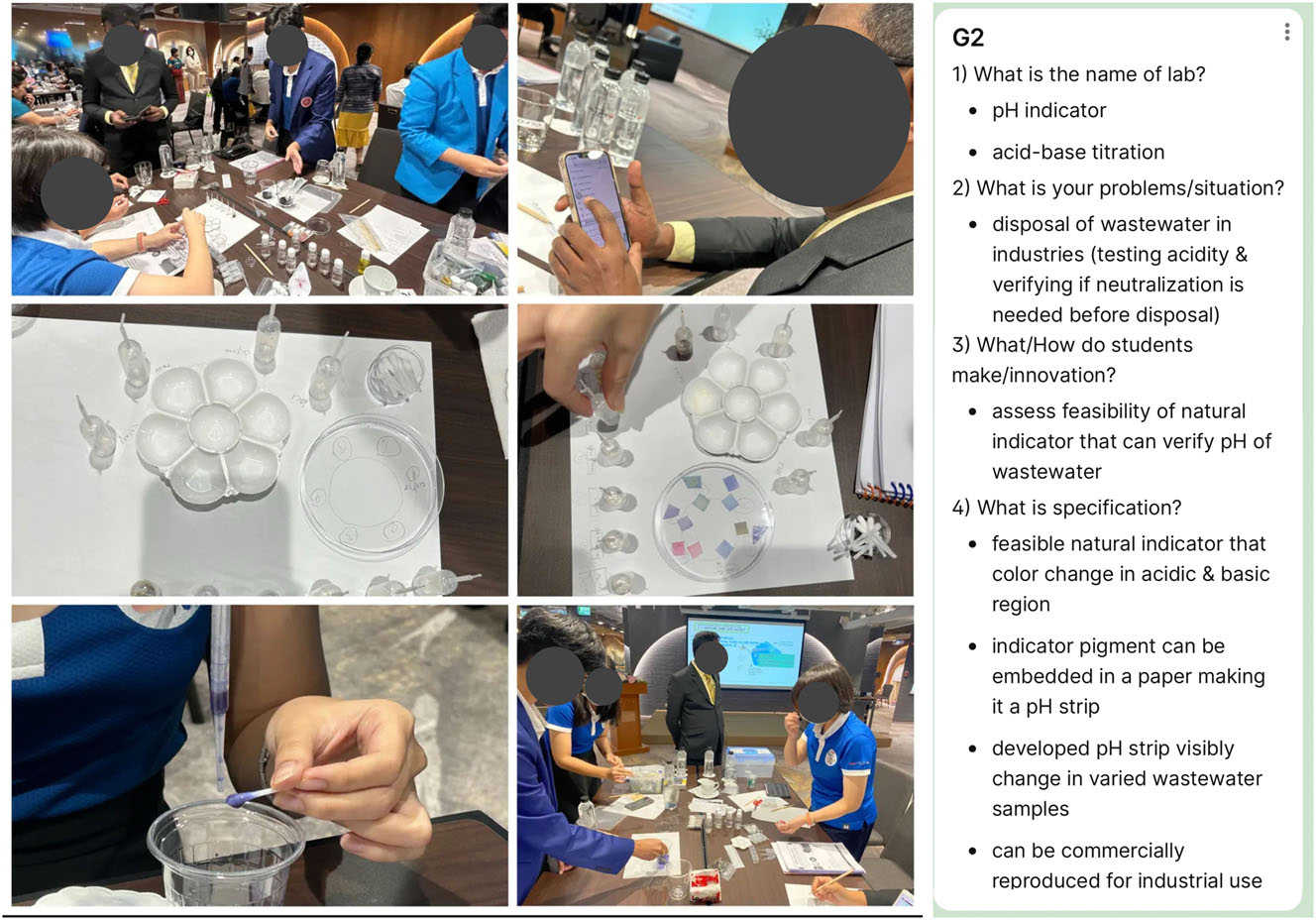

The analysis of STEM lesson designs aimed to understand how teachers applied their knowledge and skills to create practical learning experiences that integrated small-scale chemistry experiments (see Figure 1) with STEM concepts to address real-world problems. The lesson designs were evaluated based on their alignment with the principles of small-scale chemistry, green chemistry, and development goals. The analysis focused on identifying the level of disciplinary integration, use of specific disciplines,and expected outcomes of the lessons. STEM lesson designs were analyzed using inductive coding to identify emerging themes and patterns.

Examples of small-scale chemistry experiments.

5 Results

This section presents the findings organized according to our two research questions, exploring teachers’ perceptions and the design of SSC-STEM activities. The analysis integrated data from both questionnaire responses and lesson design documents to provide a comprehensive understanding of teachers’ engagement with SSC-STEM design.

5.1 Teachers perceptions

Analysis of the questionnaire responses revealed significant insights into how teachers perceive and understand SSC-STEM activities. Teachers demonstrated a strong conceptual understanding of SSC-STEM principles (see Table 2), as evidenced by the high mean scores exceeding 4.60 for core competencies. Particularly notable were the high scores in teamwork (4.63) and self-directed learning (4.73), indicating teachers’ confidence in facilitating collaborative and independent learning environments. Teachers also showed strong recognition of the importance of integrating sustainability principles and environmental consciousness into chemistry teaching.

Examples of reflective thoughts about SS-STEM.

| PCK component | Example of reflective thoughts | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of Learner in small-scale STEM |

|

Team working |

|

||

|

As solve problem | |

|

||

|

Self-directed | |

|

Learner’s difficulties | |

|

||

| Orientation in teaching small-scale STEM |

|

Improve STEM activity |

|

||

|

Evidence-based | |

|

||

|

Embedded technology | |

|

||

| Knowledge of Teaching of small-scale STEM |

|

Design SS-STEM |

|

||

|

Step-strategies | |

|

||

|

Teaching performance | |

|

||

|

The data revealed a notable gap between teachers’ theoretical understanding and practical implementation capabilities in SSC-STEM activities (see Table 3). While teachers demonstrated strength in several areas, including technology integration (4.68), evidence-based practice (4.62), teamwork (4.63), and self-directed learning (4.73), they also faced significant challenges in terms of implementation. The most pronounced concerns appeared in teaching performance (2.88) and strategies (2.94). Similarly, understanding learner difficulties (2.98) and improving STEM activities (2.99) emerged as areas that needed enhancement. This stark contrast between high scores in theoretical understanding and technology integration (all above 4.60) and lower scores in practical implementation (all below 3.00) suggests that, while teachers possess strong theoretical and technological foundations, they require additional support to translate this knowledge into effective classroom practice and student support.

Knowledge of learner in small-scale STEM [L]

This component focuses on teachers’ understanding of how students learn in the context of SSC-STEM activities. The codes within this component include “Team Working,” “As Solve Problem,” “Self-Directed,” and “Learner’s Difficulties.” The mean scores for these codes range from 2.98 to 4.73, indicating that teachers generally feel confident in their understanding of learners in ss-STEM, particularly in terms of their ability to work in teams and direct their own learning. However, the lower mean score for learners’ difficulties suggests that teachers may find it challenging to identify and address students’ difficulties in this context.

Orientation in teaching SSC-STEM [O]

This component focused on teachers’ beliefs and orientations towards teaching SSC-STEM. The codes within this component include “Embedded Technology,” “Evidence-Based,” and “Improve STEM Activity.” The mean scores for these codes range from 2.99 to 4.68, suggesting that teachers generally have a positive orientation towards teaching SSC-STEM, particularly in terms of embedding technology and using evidence-based practices. However, the lower mean score for “Improve STEM Activity” indicates that teachers may feel less confident in their ability to improve their ss-STEM teaching practices.

Knowledge of teaching of SSC-STEM [T]

This component focuses on teachers’ knowledge of specific teaching strategies and approaches to s-STEM. The codes within this component include “Design SSC-STEM,” “Step-Strategies,” and “Teaching Performance.” The mean scores for these codes were relatively low, ranging from 2.88 3.81. This suggests that teachers may feel less confident about their knowledge of specific teaching strategies for SSC-STEM and their ability to implement them effectively.

Example of reflective thoughts.

| PCK component | Code | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of Learner in small-scale STEM [L] | Team working | L-Team | 4.63 | 0.02 |

| As solve problem | L-Solve problem | 4.71 | 0.02 | |

| Self-directed | L-Self directed | 4.73 | 0.00 | |

| Learner’s difficulties | L-Difficulties | 2.98 | 0.02 | |

| Orientation in teaching small-scale STEM [O] | Embedded technology | O-Embedded tech | 4.68 | 0.05 |

| Evidence-based | O-Evidence based | 4.62 | 0.01 | |

| Improve STEM activity | O-Improve activity | 2.99 | 0.07 | |

| Knowledge of Teaching of small-scale STEM [T] | Design SS-STEM | T-Design activity | 3.81 | 0.95 |

| Step-strategies | T-Step sand strategie | 2.94 | 0.00 | |

| Teaching performance | T-Teaching performance | 2.88 | 0.10 |

While teachers demonstrated generally positive perceptions of SSC-STEM, our analysis revealed specific areas requiring targeted professional development support. The data highlighted particular challenges in translating theoretical understanding into practical implementation. Teachers struggled with three key aspects: developing effective teaching strategies; identifying and addressing student difficulties; and designing instructional approaches that bridge laboratory experiences with real-world applications. Specifically, teachers face challenges in teaching procedural knowledge that connects laboratory work to real-world problem solving and in developing strategies for translating small-scale laboratory data into broader STEM applications.

5.2 Lesson designs

The data analysis highlights the teacher’s intentional use of the SSC-STEM framework to create student-centered, inquiry-based learning experiences that connect to real-world challenges. The alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adds a layer of purpose and global awareness to the projects, showcasing the potential of STEM to address societal issues. The emphasis on applying chemical concepts, conducting small-scale experiments, and connecting findings to problem solving further reinforces the practical and inquiry-driven nature of the lessons (Table 4).

Examples of teachers’ lesson designs.

| Observation | Description | Example from G.1 (pet fish) | Example from G.2 (wastewater) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ss-STEM Framework | The teacher intentionally uses a framework that emphasizes small-scale, student-centered, inquiry-based STEM learning | The project focuses on a small-scale, student-initiated problem (pet fish dying) and encourages inquiry to find a solution | The project addresses a real-world issue (wastewater disposal) at a manageable scale, promoting student-led investigation and solution design |

| SDGs connection | The teacher aligns activities with the Sustainable Development Goals, highlighting real-world relevance | The project indirectly connects to the SDG of clean water and sanitation by promoting responsible pet ownership and understanding water quality | The project directly addresses the SDG of clean water and sanitation by seeking a solution for wastewater monitoring |

| Three Basic concepts | The instructional approach emphasizes applying chemical concepts, conducting small-scale experiments, and connecting findings to problem-solving | Students apply the concept of pH to understand its impact on fish and potentially conduct experiments to test water pH | Students apply knowledge of pH and chemical indicators to develop and test a natural pH indicator for wastewater |

| Student-centered | Both projects stem from real-world problems, suggesting a student-centered approach where learning is connected to relevant contexts | The project originates from a student’s personal experience with their pet fish dying | The project addresses a real-world industrial issue of wastewater disposal |

| Inquiry-based | Students are encouraged to investigate and innovate, implying an inquiry-based approach where students actively seek solutions | Students investigate the cause of the fish’s death and explore ways to maintain suitable pH levels | Students investigate the feasibility of creating a natural pH indicator and explore its potential applications |

| Design thinking elements | Both groups identify a problem, brainstorm solutions, consider constraints, and potentially prototype and test their ideas, demonstrating elements of design thinking | Students identify the problem of unsuitable pH, brainstorm solutions (e.g., water testing, pH adjustment), and potentially test these solutions | Students identify the problem of wastewater monitoring, brainstorm the solution of a natural indicator, consider constraints (feasibility, commercial reproduction), and potentially prototype and test the indicator |

Group-specific observations reveal that both G1 and G2 (out of 10) effectively leverage the SSC-STEM framework, albeit with different levels of complexity and focus. G1, centered around the personal experience of dying pet fish, provides a relatable entry point for students to explore the concept of pH and its impact on aquatic life. The hands-on nature of the project, potentially involving water testing and pH adjustment, allows for the direct application of scientific knowledge and problem-solving.

On the other hand, G2 (see Figure 2) tackled a broader societal challenge of wastewater disposal, requiring students to delve deeper into inquiry and design thinking. The project challenges students to innovate and create solutions within constraints, fostering their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The focus on developing a natural pH indicator demonstrates the potential of STEM to address real-world problems in a sustainable and cost-effective manner.

Group 2 small-scale chemistry-driven STEM learning design.

The observations also highlight the strengths of lesson designs, such as their authentic contexts, inquiry-based learning approaches, and integration of design thinking. However, areas for potential improvement were also identified, including the need for more explicit learning objectives, differentiation, collaboration and communication opportunities, and clear assessment strategies.

The analysis suggests that the teacher thoughtfully designed lesson plans to incorporate SSC-STEM activities that are engaging, relevant, and impactful. By addressing these areas for improvement, the teacher can further enhance the learning experience and empower students to become active contributors to solving real-world challenges through STEM.

6 Conclusion and discussions

This study successfully developed and examined the implementation of Small-Scale Chemistry-STEM (SSC-STEM) Learning Activities through an analysis of teacher perceptions and lesson designs. The findings revealed both successes and challenges in integrating small-scale chemistry with STEM education approaches, providing valuable insights for future implementation and professional development.

Our findings demonstrate the effective implementation of key SSC-STEM characteristics, particularly in terms of theoretical understanding and design principles. Teachers have successfully incorporated the unique advantages of small-scale chemistry – reduced chemical usage, enhanced safety, and increased accessibility – into their lesson designs while integrating sustainability principles and green chemistry practices. This integration aligns with the current trends in science education (Duarte et al., 2017) and shows significant progress in teachers’ ability to connect chemistry concepts with broader environmental concerns.

The analysis of teacher implementation revealed clear patterns in strengths and areas needing development. Teachers demonstrated high competency in developing STEM literacy and facilitating 21st-century skills, as evidenced by their high scores in teamwork (4.63) and self-directed learning (4.73). They successfully integrated local context and cultural relevance into their lessons, effectively connecting laboratory experiences to real-world environmental challenges. Their strong application of technology integration (4.68) and evidence-based practices (4.62) further demonstrated their grasp of the fundamental principles of SSC–STEM.

However, challenges emerged in practical teaching, with notably lower scores in teaching performance (2.88) and teaching strategies (2.94). Teachers faced difficulties in addressing student learning challenges (2.98) and in improving STEM activities (2.99). These results indicate a significant gap between theoretical understanding and practical implementation, suggesting a need for targeted professional development in specific areas of instruction and student support.

The contrast between theoretical understanding and practical implementation points to several key areas that require professional development support. Teachers need assistance in developing teaching strategies specific to SSC-STEM implementation, methods for addressing student learning difficulties, techniques for translating small-scale laboratory experiences into broader STEM applications, and approaches for improving and adapting STEM activities. This finding aligns with previous research that highlights the importance of sustained professional development in implementing integrated STEM approaches (Roehrig et al., 2021).

This study provides compelling evidence for integrating small-scale chemistry as a core component of STEM curricula. This study demonstrates how SSC-STEM can effectively bridge classroom learning with practical applications (Mohamed et al., 2012; Supasorn, 2015), promote sustainable practices and environmental consciousness, foster authentic STEM learning experiences, and support the development of 21st-century skills. The successful integration of local contexts and environmental challenges in teacher lesson design highlights the potential of this approach for making STEM education more relevant and engaging (Moore et al., 2021).

Based on these findings, we recommend several key actions to support an effective SSC-STEM implementation. First, targeted professional development programs should address the identified implementation challenges, particularly in practical teaching strategies and student support. Second, institutions should create robust support structures for teachers implementing SSC-STEM activities. Third, further research should investigate effective strategies for bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical implementation. Finally, teacher preparation programs should integrate SSC-STEM approaches into their curricula to better prepare future educators.

This study contributes significantly to understanding how small-scale chemistry can be effectively integrated into STEM education, while promoting sustainable practices and enhancing student engagement. The findings provide a clear direction for supporting teachers in implementing SSC-STEM activities and offer valuable insights for curriculum developers and policymakers (du Toit & du Toit, 2024). By addressing the identified challenges through targeted support and professional development, educational institutions can better prepare teachers to leverage the full potential of SSC-STEM in developing students’ scientific literacy and environmental consciousness.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to the Chemical Society of Thailand, Dow Thailand, and Bangkok Bank for their invaluable support in initiating and sponsoring Small-Scale Chemistry projects in Thailand and across several South Asian countries, which provided essential data for our study. Additionally, we are grateful for the opportunities to present preliminary findings and engage in scholarly discussions at the Pure and Applied Chemistry International Conference 2024 (PACCON 2024) and the 28th IUPAC International Conference on Chemical Education 2024 (ICCE 2024). These platforms have been instrumental in advancing and refining our work on STEM learning activities driven by Small-Scale Chemistry.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Abdullah, M., Mohamed, N., & Ismail, Z. H. (2009). The effect of an individualized laboratory approach through microscale chemistry experimentation on students’ understanding of chemistry concepts, motivation and attitudes. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 10(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1039/b901461f.Suche in Google Scholar

Akın, F. N., & Uzuntiryaki-Kondakci, E. (2018). The nature of the interplay among components of pedagogical content knowledge in reaction rate and chemical equilibrium topics. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 19(4), 1089–1105.10.1039/C7RP00165GSuche in Google Scholar

Aydeniz, M., & Kirbulut, Z. D. (2014). Exploring challenges of assessing pre-service science teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge (PCK). Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2014.890696.Suche in Google Scholar

Aydin-Gunbatar, S., Ekiz-Kiran, B., & Oztay, E. S. (2020). Pre-service chemistry teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge for integrated STEM development with LESMeR model. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 21(4), 1063–1082. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0rp00074d.Suche in Google Scholar

Capobianco, B. M., Nyquist, C., & Tyrie, N. (2013). Shedding light on engineering design. Science and Children, 50(5), 58.Suche in Google Scholar

Carlson, J., & Daehler, K. R. (2019). The refined consensus model of pedagogical content knowledge in science education. In Repositioning pedagogical content knowledge in teachers’ knowledge for teaching science (pp. 77–94). Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-13-5898-2_2Suche in Google Scholar

Carpendale, J., & Hume, A. (2019). Investigating practising science teachers’ pPCK and ePCK development as a result of collaborative CoRe design. In Repositioning pedagogical content knowledge in teachers’ knowledge for teaching science (pp. 225–252). Singapore: Springer Nature.10.1007/978-981-13-5898-2_10Suche in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

du Toit, A., & du Toit, L. (2024). Small-scale chemistry: A sustainable approach to hands-on science education. Journal of Chemical Education, 101(1), 123–130.Suche in Google Scholar

Duarte, R. C., Ribeiro, M. G. T., & Machado, A. A. S. (2017). Reaction scale and green chemistry: Microscale or macroscale, which is greener? Journal of Chemical Education, 94(9), 1255–1264. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.7b00056.Suche in Google Scholar

Goes, L. F., & Fernandez, C. (2023). Evidence of the development of pedagogical content knowledge of chemistry teachers about redox reactions in the context of a professional development program. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111159.Suche in Google Scholar

Grubbs, M., & Strimel, G. (2015). Engineering design: The great integrator. Journal of STEM Teacher Education, 50(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.30707/jste50.1grubbs.Suche in Google Scholar

Honey, M., Pearson, G. & Schweingruber, H. (Eds.) (2014). STEM integration in K-12 education: Status, prospects, and an agenda for research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lertdechapat, K., & Faikhamta, C. (2021). Enhancing pedagogical content knowledge for STEM teaching of teacher candidates through lesson study. International Journal for Lesson & Learning Studies, 10(4), 331–347. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijlls-03-2021-0020.Suche in Google Scholar

Listyarini, R. V., Pamenang, F. D. N., Harta, J., Wijayanti, L. W., Asy’ari, M., Lee, W., & Lee, W. (2019). The integration of green chemistry principles into small scale chemistry practicum for senior high school students. Jurnal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia, 8(3), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.15294/usej.v8i3.31857.Suche in Google Scholar

Mafumiko, F., Voogt, J., & Van den Akker, J. (2013). Design and evaluation of micro-scale chemistry experimentation in Tanzanian schools. In T. Plomp, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research–Part B: Illustrative cases (pp. 581–600). Enschede: SLO.Suche in Google Scholar

Mavhunga, E. (2020). Revealing the structural complexity of component interactions of topic-specific PCK when planning to teach. Research in Science Education, 50(3), 965–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9719-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Mavhunga, E., Ibrahim, B., Qhobela, M., & Rollnick, M. (2016). Student teachers’ competence to transfer strategies for developing PCK for electric circuits to another physical sciences topic. African Journal of Research in Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 20(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2016.1237000.Suche in Google Scholar

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Mohamed, N., Abdullah, M., & Ismail, Z. H. (2012). Enhancing students’ understanding of physical chemistry through the use of small-scale experiments. Journal of Chemical Education, 89(9), 1207–1211.Suche in Google Scholar

Moore, T. J., Bryan, L. A., Johnson, C. C., & Roehrig, G. H. (2021). Integrated STEM education. In STEM Road Map 2.0 (pp. 25–42). New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003034902-4Suche in Google Scholar

National Research Council (2011). Successful K-12 STEM education: Identifying effective approaches in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.Suche in Google Scholar

NGSS Lead States (2013). Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Park, S., & Chen, Y. C. (2012). Mapping out the integration of the components of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK): Examples from high school biology classrooms. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(7), 922–941. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21022.Suche in Google Scholar

Park, S., & Oliver, J. S. (2008). Revisiting the conceptualisation of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK): PCK as a conceptual tool to understand teachers as professionals. Research in Science Education, 38(3), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-007-9049-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Roehrig, G. H., Dare, E. A., Ellis, J. A., & Ring-Whalen, E. (2021). Beyond the basics: A detailed conceptual framework of integrated STEM. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 3, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-021-00041-y.Suche in Google Scholar

Saxton, E., Burns, R., Holveck, S., Kelley, S., Prince, D., Rigelman, N., & Skinner, E.A. (2014). A common measurement system for K-12 STEM education: Adopting an educational evaluation methodology that elevates theoretical foundations and systems thinking. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 40, 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.11.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1175860.Suche in Google Scholar

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411.Suche in Google Scholar

Supasorn, S. (2015). Grade 12 students’ conceptual understanding and mental models of galvanic cells before and after learning by using small-scale experiments in conjunction with a model kit. Chemistry Education: Research and Practice, 16(2), 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4rp00247d.Suche in Google Scholar

Tesfamariam, G., Lykknes, A., & Kvittingen, L. (2014). Small-scale chemistry for a hands-on approach to chemistry practical work in secondary schools: Experiences from Ethiopia. African Journal of Chemical Education, 4(3), 48–94.Suche in Google Scholar

Tesfamariam, G. M., Lykknes, A., & Kvittingen, L. (2017). ‘Named small but doing great’: An investigation of small-scale chemistry experimentation for effective undergraduate practical work. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(3), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9700-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Van Driel, J. H., Jong, O. D., & Verloop, N. (2002). The development of preservice chemistry teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. Science Education, 86(4), 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10010.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 27th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education (ICCE 2024)

- Special Issue Papers

- Recent advances in laboratory education research

- Examining the effect of categorized versus uncategorized homework on test performance of general chemistry students

- Enhancing chemical security and safety in the education sector: a pilot study at the university of Zakho and Koya University as an initiative for Kurdistan’s Universities-Iraq

- Leveraging virtual reality to enhance laboratory safety and security inspection training

- Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in college chemistry

- High school students’ perceived performance and relevance of chemistry learning competencies to sustainable development, action competence, and critical thinking disposition

- Spatial reality in education – approaches from innovation experiences in Singapore

- Teachers’ perceptions and design of small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

- Electricity from saccharide-based galvanic cell

- pH scale. An experimental approach to the math behind the pH chemistry

- Engaging chemistry teachers with inquiry/investigatory based experimental modules for undergraduate chemistry laboratory education

- Reasoning in chemistry teacher education

- Development of the concept-process model and metacognition via FAR analogy-based learning approach in the topic of metabolism among second-year undergraduates

- Synthesis of magnetic ionic liquids and teaching materials: practice in a science fair

- The development of standards & guidelines for undergraduate chemistry education

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The 27th IUPAC International Conference on Chemistry Education (ICCE 2024)

- Special Issue Papers

- Recent advances in laboratory education research

- Examining the effect of categorized versus uncategorized homework on test performance of general chemistry students

- Enhancing chemical security and safety in the education sector: a pilot study at the university of Zakho and Koya University as an initiative for Kurdistan’s Universities-Iraq

- Leveraging virtual reality to enhance laboratory safety and security inspection training

- Advancing culturally relevant pedagogy in college chemistry

- High school students’ perceived performance and relevance of chemistry learning competencies to sustainable development, action competence, and critical thinking disposition

- Spatial reality in education – approaches from innovation experiences in Singapore

- Teachers’ perceptions and design of small-scale chemistry driven STEM learning activities

- Electricity from saccharide-based galvanic cell

- pH scale. An experimental approach to the math behind the pH chemistry

- Engaging chemistry teachers with inquiry/investigatory based experimental modules for undergraduate chemistry laboratory education

- Reasoning in chemistry teacher education

- Development of the concept-process model and metacognition via FAR analogy-based learning approach in the topic of metabolism among second-year undergraduates

- Synthesis of magnetic ionic liquids and teaching materials: practice in a science fair

- The development of standards & guidelines for undergraduate chemistry education