Abstract

Microbially influenced corrosion and biofouling emerge as formidable challenges to the sustainable management and exploitation of marine resources. The primary instigator for these challenges lies in the insidious development of biofilm. Hence, the most direct and pivotal approach to counteracting microbial corrosion and biofouling resides in the advancement of anti-biofilm technologies. Conventional methodologies for combatting biofilm are efficient but have certain drawbacks, particularly environmental contamination and inefficacy. Research into innovative anti-biofilm technologies is imperative for more efficient use of marine resources and protection of the ecological equilibrium of the oceans. This paper offers a detailed examination of biofilm constituents, the complex processes involved in biofilm development, the various factors that affect biofilm formation, and the mechanisms underlying microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC). Furthermore, the article summarizes emerging, eco-friendly anti-biofilm technologies, while providing the evolving landscape of anti-biofilm strategies and promising prospects.

1 Introduction

Covering approximately 71 % of the Earth’s surface (Ferrer et al. 2019), the ocean represents a vast reservoir of potential for human advancement and global economic development and it is also responsible for facilitating over 90 % of global trade (Li and Ning 2019). The ocean’s significance in the economic and social progress of China’s eastern coast is monumental. Although the land area of the 12 coastal provinces, districts, and cities accounts for a mere 14 % of the nation’s territory, it contributes 60 % of the national GDP. The output value of the national marine economy has surged to an impressive 3.8 trillion yuan, with a growth rate surpassing 20 %. However, this rapid expansion of the marine economy has ushered a series of intricate challenges. Within this dynamic landscape, marine anti-corrosion technology emerges as a pivotal domain for high-quality development of marine-related industries and effective translation of scientific and technological breakthroughs. Consequently, research into marine anti-corrosion technology has garnered considerable attention both at home and abroad.

China’s advancement in marine anti-corrosion technology has been relatively gradual in comparison to developed countries, and its significance has recently garnered limited recognition. Through a comprehensive survey, corrosion-related expenditures in China accounted for approximately 3.34 % of the nation’s GDP in 2014, which corresponds to 2,127.82 billion yuan. This equated to a corrosion cost exceeding 1,555 yuan for every citizen (Hou et al. 2017). Due to this, emphasis has arisen on modernization of anti-corrosion technology, enhancing its performance, and curbing the extensive losses attributable to corrosion.

Presently, the key foci of marine corrosion research are steel corrosion, microbial corrosion, concrete corrosion, and marine environmental corrosion. Among these, microbial corrosion stands out as a prominent hotspot with substantial research significance. Globally, the annual economic toll of marine corrosion reaches approximately 2.5 trillion U.S. dollars (Lahme et al. 2021). Notably, the consequences of varying degrees of microbial-driven corrosion account for a significant 20 % of this total loss (Lekbach et al. 2021).

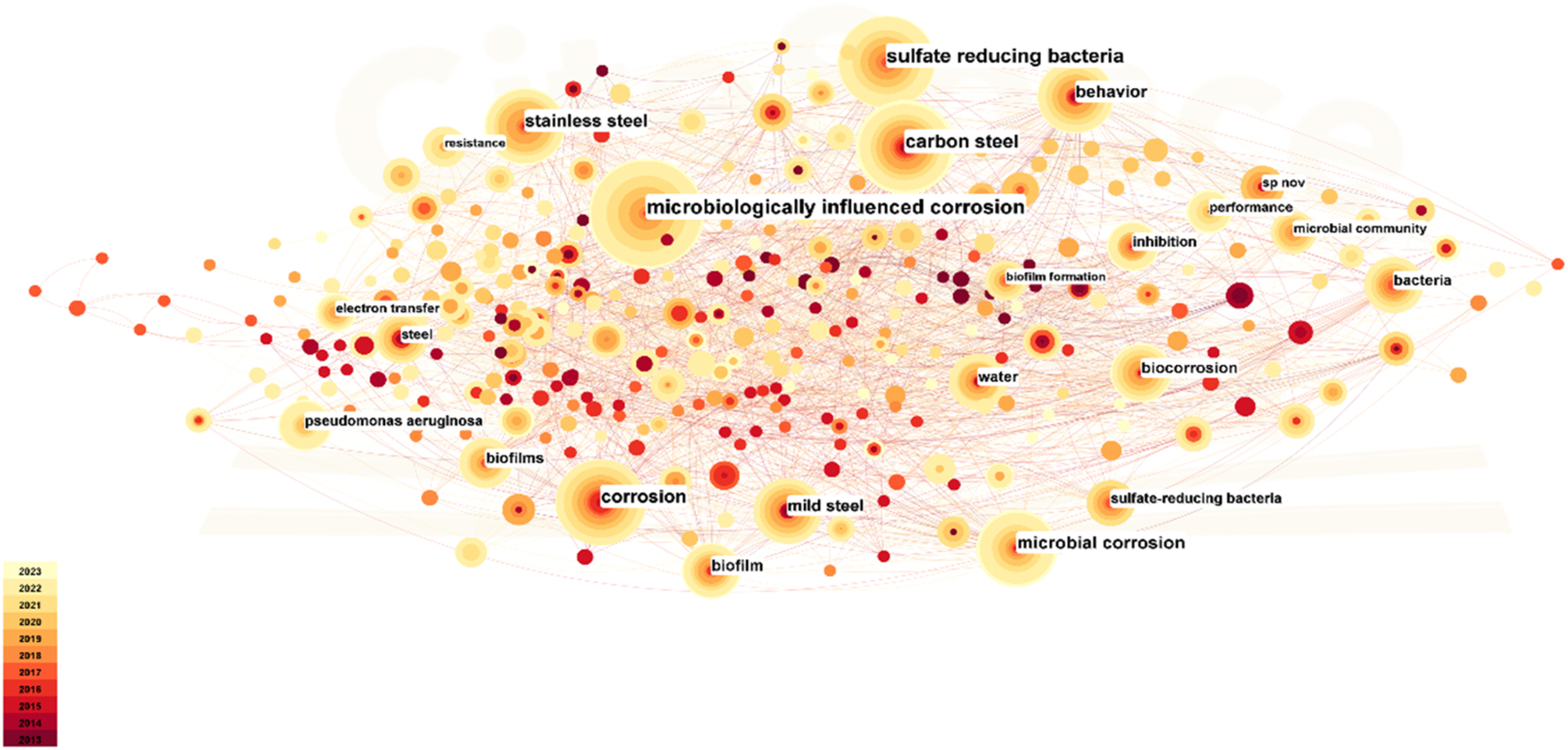

To provide a comprehensive overview of the research landscape, we examined research outcomes on marine microbial corrosion using data from Web of Science. The results illustrated in Figure 1 were generated through CiteSpace to visualize keyword co-occurrence trends.

Co-occurrence analysis of marine microbial corrosion keywords in Web of Science.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, it is evident that the primary research focal points in the domain of marine microbial corrosion, both domestically and internationally, predominantly revolve around the marine environment, electrochemical corrosion mechanisms, and microorganisms. In recent years, owing to the escalating development and exploitation of marine resources, marine microbial corrosion, as a pivotal facet within the broader field of marine corrosion, has garnered increasing attention. Research in this domain encompasses investigations into the mechanisms of marine microbial corrosion, methods for corrosion prevention, and a myriad of converging topics, yielding a steady stream of research findings. Microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) constitutes a phenomenon wherein the corrosion of metals is directly or indirectly promoted by the activities of microorganisms and their metabolic byproducts (Lou et al. 2021). MIC represents a multifaceted bioelectrochemical process that draws upon multiple disciplines, including physics, chemistry, electrochemistry, materials science, and microbiology (Lv and Du 2018; Lv et al. 2022). Notably, biofilms have emerged as the prevailing and highly successful microbial lifestyle. Bacteria produce a complex biofilm matrix known as extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). EPS serves multi-role including facilitating the colonization of both biotic and abiotic surfaces, bolstering the stability of the growth environment, enhancing resistance to antibiotics and adverse conditions, and serving as important component of biofilms (Zabiegaj et al. 2021). Because biofilms serve as the primary locus for microbial aggregation, reproduction, and metabolism, they play an important role in the MIC process. Consequently, the advancement of theories and technologies relating to biofilms contributes significantly to a deeper comprehension of MIC (Rao et al. 2000; Yuan et al. 2013). In light of these considerations, this paper begins with a comprehensive review covering the composition, evolution, participation in the MIC process, and environmentally conscious anti-biofilm technologies.

2 Composition of biofilm

In their natural milieu, microorganisms predominantly exist in a planktonic state. However, when they need to live on the surfaces of materials such as steel and concrete, they undergo a transformative process by forming a biofilm. This biofilm is comprised of various components including bacterial communities, water, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and corrosion products (AlAbbas et al. 2013; Belkaid et al. 2011). Notably, all of these components exhibit adhesive properties that enable microorganisms to connect to gel-like matrices formed by the extracellular polymers.

2.1 Extracellular polymerization substrate

Biofilm represents a highly intricate entity, comprising an array of components, with the biofilm matrix assuming a predominant role. Typically, the matrix constitutes approximately 90 % of the biofilm’s structure, while microorganisms constitute less than 10 %. This biofilm matrix primarily comprises a diverse amalgamation of biopolymers collectively referred to as extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). These biopolymers encompass lipids, DNA, proteins, metabolites, and various other macromolecules (Hall-Stoodley et al. 2004). Among these constituents, carbohydrates emerge as the most abundant, often ranging from 40 % to 95 %, while other macromolecules, such as proteins, typically account for 1 %–60 %, nucleic acids for 1 %–10 %, and lipids for 1 %–40 %. Notably, the composition of this matrix is dynamic, subject to fluctuations influenced by factors including microbial species, cellular physiological states, and environmental conditions (Wingender et al. 1999).

A clear correlation has been revealed between EPS and the binding capacity of metal surfaces in MIC (Rohwerder et al. 2003; Sand 2003; Zanna et al. 2022). This interaction depends on many factors, including the specific microbial and metal species, as well as the intricate interplay between metal ions and anions (Carboxylate, glycerate, phosphate, pyruvate, sulfate, etc.). Notably, polydentate anions exhibit a greater affinity for metal cations(Ca2+、Cu2+、Fe2+、Mg2+), resulting in the redistribution of metal cations into the interstitial space in the biofilm matrix. Moreover, investigations have uncovered the presence of electron-conducting fibers interspersed throughout the biofilm matrix. These fibers play a pivotal role in coordinating the metal ions ensnared within the biofilm matrix through the engagement of diffuse ligands. Consequently, this process engenders the formation of complexes characterized by diverse redox potentials (Beech and Sunner 2004). These complexes may play a vital role in facilitating electron transfer during the corrosion process, although this is contingent on the specific chemical properties of the metal surface in association with the microorganisms (Busalmen et al. 2002).

On the other hand, in a study by Dong et al. (Dong et al. 2011), it was discovered that certain types of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) also act as corrosion inhibitors. This inhibition occurs through the mitigation of oxygen ion mass transfer, a phenomenon observed in their examination of the impact of extracted EPS on steel corrosion. However, it’s crucial to note that this effect is contingent on the concentration of EPS, with corrosion inhibition performance diminishing at higher EPS concentrations. Furthermore, EPS plays a pivotal multifaceted role in various stages of biofilm formation and maturation. It lends structural support that facilitates the development of the biofilm’s three-dimensional architecture. Simultaneously, it upholds the biofilm’s surface integrity, providing a conducive habitat for diverse microbial colonization. Consequently, this fosters an enhancement in biodiversity within the biofilm (Flemming and Wingender 2010).

2.2 Main corrosive microorganisms

2.2.1 Sulfate reducing bacteria

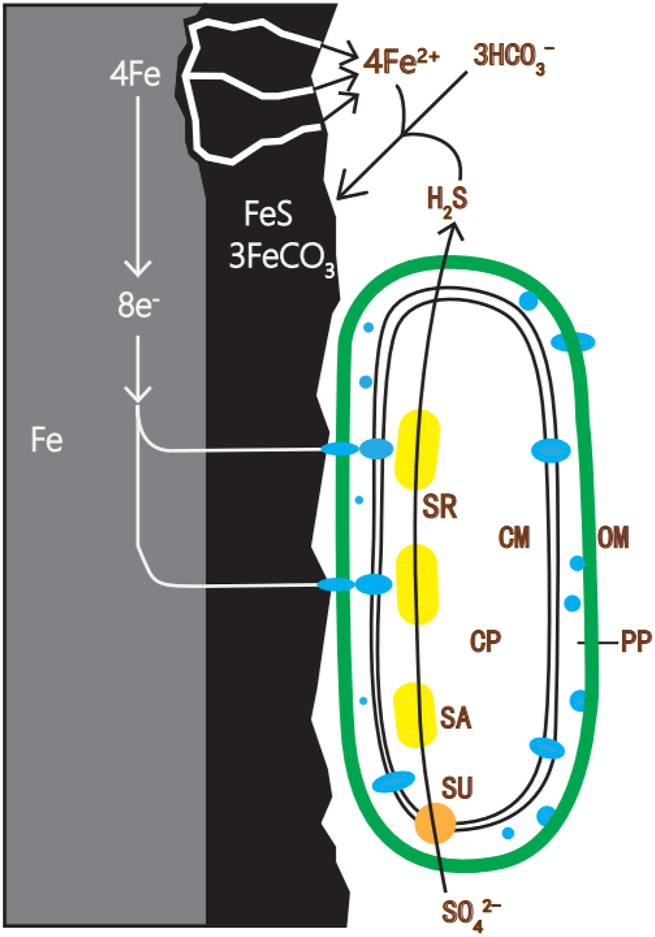

Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), serving as pivotal microorganisms in MIC studies, occupy a central role in most microbial corrosion processes (Gu et al. 2019; Enning and Garrelfs 2014; Xu et al. 2023). Figure 2 illustrates the process of SRB participating in corrosion on iron surfaces. These resilient microorganisms thrive in environments characterized by elevated sulfate concentrations, encompassing sulfur valence states spanning from −2 to + 6. Significantly, SRB display the remarkable capacity to utilize sulfur compounds with valence states of −2 or higher as terminal electron acceptors. This versatile repertoire includes sulfite bisulfate (HSO3 −), thiosulfate (S2O3 2−), and monomeric sulfur (Jia et al. 2019). Furthermore, SRBs are classified as anaerobic organisms, ideally adapted for survival in oxygen-depleted environments. Within biofilms, SRB typically establish their habitat in the lower strata. This strategic positioning arises as a response to the aerobic bacteria inhabiting the upper layers, which consume the available oxygen, thereby creating anaerobic conditions that favor SRB survival. Continued research endeavors have led to the discovery of several SRB species exhibiting varying degrees of oxygen tolerance. For instance, Desulfovibrio desulfuricans has developed the capability for aerobic respiration. However, in the presence of oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor, its function is limited to energy maintenance, with no support for sustained growth (Dannenberg et al. 1992). Previous studies have indicated distinct iron corrosion mechanisms between Desulfovibrio vulgaris and Desulfovibrio ferrophilus, with D. ferrophilus typically exhibiting accelerated corrosion rates. However, recent findings have revealed that the corrosion rate of D. vulgaris increases significantly with rising chloride levels, surpassing that of D. ferrophilus in identical marine environments. This underscores the critical importance of considering medium composition in microbiological corrosion investigations (Wang et al. 2024a).

The process of SRB participating in corrosion on iron surfaces.

In traditional theories of MIC, such as the oxygen concentration difference theory, the presumption was that neither microorganisms nor biofilms played a direct role in the MIC process. However, as MIC research has progressed, the understanding of its mechanism has shifted towards the perspectives of bioenergetics and bioelectrochemistry. A more precise explanation of the MIC mechanism has emerged with the proposition of the biocatalytic cathodic sulfate reaction (BCSR) theory (Li et al. 2018; Li and Ning 2019; Sherar et al. 2011; Xu and Gu 2014; Zhang et al. 2015). For SRB, their growth necessitates an electron donor to serve as an energy source and an electron acceptor to fuel their metabolic processes. Typically, organic carbon sources such as lactate or fatty acids act as electron donors, while sulfate serves as the electron acceptor in redox processes (Wang et al. 2023). In the context of the BCSR theory, when SRB form a biofilm on the surface of metallic iron, the biofilm functions as a barrier to mass transfer, preventing the diffusion of the carbon source. As the upper layer of the biofilm depletes the carbon source, SRB residing in the lower stratum near the metal surface find themselves in a carbon source-deficient environment. Lacking access to external carbon sources and electrons, SRB resort to utilizing elemental iron as an electron donor, thereby inducing metal corrosion to sustain their energy needs. The electrons released by the corroding metal traverse the SRB cell wall and are ultimately employed in the sulfate reduction reactions occurring within the SRB cytoplasm. This theory not only furnishes a more detailed elucidation of SRB-induced corrosion but also underscores that in scenarios of carbon source scarcity within the biofilm, microorganisms corrode metals primarily to extract energy essential for their own survival. Recent studies investigating the corrosion mechanism of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) using hydrogenase-deficient mutants have questioned the hypothesis that D. vulgaris directly uptakes electrons from electrodes in the presence of ferrous sulfides. These findings underscore the necessity for rigorous validation of mechanistic approaches and resolution of controversies in corrosion literature using mutant strains (Wang et al. 2024b).

2.2.2 Nitrate reducing bacteria

Nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB) are important players in the marine nitrogen cycling process (Hou et al. 2024), and are also found extensive applications in the realm of oil and gas engineering, primarily to curb the proliferation of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and mitigate reservoir acidification (Fida et al. 2016; Gieg et al. 2011). However, in the course of deeper investigations, it has been unveiled that NRB, at times, exhibit even greater corrosive potential than SRB when it comes to stainless and carbon steels. Under anaerobic conditions, Bacillus licheniformis, for instance, has demonstrated its corrosive impact on C1018 carbon steel. Intriguingly, pitting experiments have revealed that under strictly anaerobic conditions, Bacillus licheniformis engages in more aggressive pitting as compared to SRB (Xu et al. 2013). Moreover, NRB’s corrosive tendencies extend beyond carbon and stainless steel to include Cu. It’s noteworthy that copper boasts broad bactericidal properties (Jia et al. 2012; Li et al. 2017; Ma et al. 2019), typically acting as an inhibitor of bacterial growth. Nevertheless, exceptions exist, as NRB can induce MIC on copper. Studies have pinpointed nitrate-reduced Pseudomonas aeruginosa-retaining bacteria as the primary culprits behind Extracellular Electron Transfer MIC (EET-MIC) on copper. Furthermore, the secretion of NH3 by P. aeruginosa has been identified as an accelerant in the corrosion process (Pu et al. 2020).

Traditionally, pristine seawater has not been associated with nitrate presence. However, recent investigations in soil microbial corrosion studies have unveiled a concerning development: agricultural runoff can transport nitrate into both soil and the ocean (Wan et al. 2018). This influx of nitrate brings with it the corrosion risk posed by NRB to operational facilities situated in marine environments.

2.2.3 Iron oxidizing bacteria

As an aerobic bacterium, iron oxidizing bacteria (IOB) often collaborates synergistically with SRB, leading to MIC. IOB play a critical role in this process by consuming oxygen within the cell membrane, thereby establishing an environment conducive for the growth of SRB (Lv et al. 2019). In this process, the two microorganisms exert a synergistic effect that intensifies localized metal corrosion. Notably, the presence of iron-oxidizing bacteria (IOB) enhances the growth activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), thereby amplifying their corrosive impact on steel compared to when each species acts alone (Lv et al. 2022). Not to be overlooked, it’s important to note that IOB themselves can induce corrosion in steel facilities. According to the theory of oxygen concentration cells, corroborated by research experiments, IOB can generate such oxygen concentration cells on the surface of stainless steel when immersed in oxygen-enriched seawater, consequently expediting corrosion processes (Ray et al. 2010). IOB produce dense deposits that adhere to material surfaces, effectively impeding oxygen diffusion to the material’s surface. This, in turn, fosters the creation of anodic sites, where the corrosion rate is primarily contingent upon the metallurgical properties of the material and the physical and chemical properties of the electrolyte. These properties encompass oxygen solubility and chloride ion (Cl−) solubility (Lv et al. 2021). Furthermore, the presence of other metal deposits within these deposits also influences the formation of oxygen concentration cells. For example, the existence of copper (Cu) deposits results in the establishment of galvanic couples with the iron _substrate. The magnitude of the galvanic current is directly correlated with the concentration of iron in the electrolyte, independently of the bacterial population within the deposit. Additionally, oxygen concentration cells can form when metal ions interact with anionic functional groups, such as carboxylic acids, sulfates, pyruvates, and phosphoric acids, present within the EPS secreted by microorganisms (Ray et al. 2009).

2.2.4 Acid producing bacteria

The pH levels beneath a biofilm exhibit a pronounced reduction compared to the pH levels in the surrounding fluid, and this pH differential can be notably significant, even between adjacent biofilms (Vroom et al. 1999). This divergence in pH dynamics arises from the collaborative action of acid-producing bacteria (APB), which release organic acids within the biofilm to lower its pH, and proton attack, which becomes thermodynamically favorable when oxidative binding with iron transpires at sufficiently low pH levels. Unlike sulfate reduction, proton reduction doesn’t necessitate biocatalysis and can take place directly on the extracellular metal surface (Gu 2014). Concurrently, free cells contribute to maintaining an acidic milieu by generating protons, thereby further augmenting the corrosion process. It’s worth noting that the organic acids produced by acid-producing bacteria are categorized as weak acids but possess the buffering capacity to yield additional protons. This feature renders organic acids significantly more corrosive than strong acids like sulfuric acid (Kryachko and Hemmingsen 2017). Within the confines of an APB biofilm, the pH differential can easily amount to two units lower than the pH outside the biofilm. This disparity is attributable to the higher density of sequestered microorganisms within the biofilm compared to the density of free-floating, planktonic microorganisms. Under anaerobic conditions, APBs typically function as fermentative microorganisms, with acid constituting a common outgrowth of anaerobic fermentation. Nevertheless, APBs can also adapt to aerobic environments. For example, Acidithiobacillus spp efficiently oxidize various reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) and elemental sulfur. This oxidation process generates electrons to sustain autotrophic growth. However, this autotrophic growth has a dual consequence: a reduction in pH within the biofilm (Gu et al. 2018) and the potential for severe corrosion, particularly of high-grade stainless steel (Dong et al. 2018).

3 The process of biofilm formation

In the marine environment, where macroorganisms coexist with microorganisms, biofilm formation must be ensured before microorganisms attach to higher macroscopic biological surfaces. Consequently, a substantial aggregation of microorganisms occurs on the surfaces of macroorganisms, especially in the aftermath of their demise and decay. This scenario provides an ideal setting for biofilm development, leading to the proliferation of microorganisms. Figure 3 elucidates the intricate process of biofilm formation and progression, which typically encompasses six distinct stages:

Formation of adsorption film on the metal surface: initially, an adsorption film materializes on the surface of the metal.

Attraction of plankton from the ocean: plankton present in the surrounding ocean are drawn towards the adsorption film on the metal surface.

Transformation of free plankton: the free-floating plankton adheres to the material’s surface and undergo a transformation into firmly entrenched microorganisms.

Growth and metabolism of entrenched microorganisms: these entrenched microorganisms commence growth and metabolic activities, ultimately culminating in the formation of a biofilm.

Maturation of the biofilm: as metabolic byproducts accumulate, the biofilm matures into a stable state, concurrently initiating the onset of corrosion. This phase is characterized by the generation of corrosion products, which in turn accelerates the corrosion rate.

Evolving dynamics: over time, the stability of the biofilm diminishes, resulting in the detachment of certain portions, leading to the formation of heterogeneous biofilms. Simultaneously, some of the entrenched microorganisms are released, reverting to a free state and participating in the subsequent cycle of biofilm formation.

Process of biofilm formation and development.

4 Factors affecting biofilms

The morphology and architecture of biofilms exhibit a remarkable degree of variation contingent upon factors such as microbial growth rate and the availability of nutrients. Notably, both high and low nutrient levels exert limiting influences on biofilm activity. Biofilms, it’s crucial to note, do not constitute homogenous entities. Instead, they comprise an intricate arrangement where colonies are segregated by diffusely distributed metabolic byproducts and an intricate network of interstitial channels (Beech et al. 2014; Eckert 2015). This structural heterogeneity significantly impacts biofilm activity by modulating the rate of nutrient transport and consumption (Lewandowski 2000). Studies have indicated that microorganisms positioned in the upper regions of the biofilm benefit from enhanced nutrient accessibility, rendering them more active in comparison to their counterparts dwelling in the lower strata of the biofilm (Anwar et al. 1992). Biofilms tend to exhibit heightened activity, greater thickness, and enhanced robustness when nutrient levels are abundant. This scenario furnishes a more conducive and dependable environment for microbial proliferation and reproduction (Salgar-Chaparro et al. 2020). However, it’s worth noting that reduced nutrient availability curtails biofilm activity and retards microbial growth within it. Paradoxically, this limitation also endows microorganisms with heightened resistance to antimicrobial agents (Allison and Gilbert 1995; Anutrakunchai et al. 2018). Some researchers have postulated that actively proliferating microorganisms exhibit greater susceptibility to antibiotics compared to their slower-growing or relatively quiescent counterparts. This is because slow-growing microorganisms have poorer permeability of their biofilms, making them more resistant (Anwar et al. 1992). Essentially, lower nutrient levels, while constraining biofilm activity, confer a heightened level of resistance.

Biofilms thrive within a multifaceted environment where a multitude of factors – including temperature, pH, material surface roughness, and fluid dynamics of the surrounding medium – profoundly influence their growth, in addition to nutrient availability. Remarkably, temperature fluctuations can induce shifts in the bacterial community within biofilms, coupled with alterations in the composition of the EPS (Pinel et al. 2021). In the context of pipeline transportation, the fluidity of the liquid environment emerges as a pivotal determinant of biofilm development. In freshwater settings characterized by flowing water, stable biofilm structures tend to form more readily. Conversely, stagnant water environments necessitate a comparatively extended timeframe for the establishment of stable biofilms (Li et al. 2020). This discrepancy can be attributed to the greater abundance of nutrients and oxygen concentrations in flowing water, rendering it a favorable milieu for biofilm proliferation. Furthermore, the roughness of the material surface wields a substantial influence over the biomass, physiological state, and structural capacity of the biofilm (Vivier et al. 2021). Simultaneously, the interplay between temperature and pH assumes paramount significance in shaping biofilm growth, with due consideration to fluid dynamics and material surface characteristics. Ultimately, it’s the synergistic interplay of the microenvironment encompassing the biofilm that engenders variations in biofilm structure and behavior across diverse microenvironmental contexts.

5 Involvement of biofilms in the process of MIC

In the marine milieu, both living organisms and inanimate surfaces undergo swift and extensive colonization by a diverse array of microbial communities. This rapid and extensive colonization hinges primarily on the formation of biofilms, which confer several ecological advantages to microorganisms. This colonization mechanism precipitates metal corrosion as microorganisms adhere to metal surfaces. However, biofilms serve a more intricate role in the process of MIC. They play a pivotal role in the creation of oxygen concentration cell (Jia et al. 2019). The formation of a biofilm impedes the diffusion of oxygen, and the respiratory activities of microorganisms within the biofilm deplete oxygen levels. Consequently, a region with diminished oxygen concentration forms within the biofilm, serving as the anode, while other areas maintain relatively higher oxygen concentrations, constituting the cathode. This configuration results in the establishment of an oxygen concentration cell, which accelerates metal corrosion. Simultaneously, the reduced oxygen levels within the biofilm create favorable conditions for the survival of anaerobic bacteria, such as SRB.

In general, organic matter can permeate cells through diffusion from the external environment. However, in the case of SRB corrosion, insoluble metal ions like Fe0 cannot diffuse into the cell. Therefore, extracellular electrons must be transported to the cell’s cytoplasm to facilitate reduction reactions. This electron transfer process, occurring through the cell wall, is termed extracellular electron transfer (EET) (Jin et al. 2023; Xu et al. 2023; Zhou et al. 2022). It has been firmly established that biofilms play a pivotal role in mediating electron transfer during microbial corrosion (Zhang et al. 2015). Given that biofilms directly adhere to the metal surface, the cilia within the biofilm interconnecting each entrenched cell enable these entrenched cells to establish a direct connection with the metal surface. Consequently, the multilayered entrenched cells become actively engaged in the electron transfer process. The presence of biofilm expedites the electron transfer from the metal surface to the cytoplasm through the cell wall, simultaneously involving more entrenched cells in the corrosion process. This, in turn, accelerates the corrosion rate.

Beyond microbial colonization, biofilms also act as a magnet for larger fouling organisms. While the majority of MIC cases are attributed to microorganisms, the damage stemming from biofouling should not be underestimated. Algae and bacteria can establish synergistic relationships within biofilms, with algae reaping the benefits of compounds like vitamin B12 (cobalamin) produced by bacteria, while the bacteria rely on oxygen and carbonaceous metabolites generated by algae for their survival (Armstrong et al. 2000; Croft et al. 2005). Furthermore, the bacterial communities thriving in the assemblages formed by invertebrates in polluted environments also wield a substantial influence over the ongoing corrosion of metals (McNamara et al. 2009). Multiple studies have underscored how biofilm formation can either encourage or impede the colonization of metal surfaces by invertebrate larvae.

While biofilms typically act as catalysts for metal corrosion through various mechanisms, there are certain exceptional cases where they can inhibit the onset of MIC due to their physical shielding effect (Iverson 1987). This intriguing phenomenon underscores the dual nature of biofilms, with corrosion inhibition by biofilms generally occurring during the initial stages of biofilm formation. A notable example is the early-stage biofilm generated by Bacillus species (Abdoli et al. 2016). Building upon this insight, it has been revealed that not all bacteria within the biofilm exert a corrosive impact on metals. Some microorganisms can, to a certain extent, play a role in inhibiting corrosion (Dong et al. 2011). This phenomenon, where biofilms and the microorganisms they contain mitigate corrosion, is referred to as microbiologically influenced corrosion inhibition (MICI).

6 Progress on the inhibition of biofilm development

Biofilm formation presents a significant challenge in the marine industry, with both microbial corrosion and biofouling intricately linked to this process (Fitridge et al. 2012). Consequently, curbing biofilm formation, colonization, and growth has emerged as the pivotal strategy for addressing microbial corrosion and biofouling issues (Antunes et al. 2019). Traditional approaches to biofilm inhibition encompass the use of chemical biocides, anti-corrosive coatings, and artificial membrane structures, among others. Unfortunately, these methods often entail secondary pollution, exhibit limited timeliness, and incur substantial costs (Hawkins et al. 2017; Peres et al. 2015; Qin et al. 2019; Rijavec et al. 2019). Thus, there exists an urgent imperative to pioneer novel, environmentally friendly, and non-polluting biofilm inhibition technologies. In recent years, both domestic and international efforts have yielded advancements in biofilm inhibition technology. To fulfill the requisites of non-pollution, durability, and cost-effectiveness, the primary research avenues include material modification, the utilization of naturally derived compounds, and the development of novel corrosion inhibitors.

6.1 Photocatalytic materials

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on photocatalytic materials, which hold immense promise in various research domains. These materials remain inert under visible light but possess the remarkable ability to harness light energy and convert it into the energy required for catalytic chemical reactions. Notably, photocatalytic materials have found extensive applications in biofilm inhibition. Through meticulous research and screening, it has become evident that many natural photocatalytic materials exhibit not only eco-friendliness but also exhibit high antimicrobial efficacy. For instance, treated rapeseed pollen (TRP) (Li et al. 2022) has demonstrated catalytic disinfection properties. Experimental investigations have revealed its robust photosensitivity and oxidizing capabilities. It exhibits a commendable capacity for countering microbial colonization when exposed to visible light and can effectively disperse pre-established biofilms on stainless steel surfaces in natural seawater. Crucially, immobilizing photocatalytic particles onto mechanically robust metal surfaces is imperative for environmentally friendly sterilization. Zhai and colleagues (Zhai et al. 2021), for instance, successfully embedded BIVO4 into zinc substrates, harnessing the photocatalytic antimicrobial prowess of BIVO4. This innovative approach resulted in the stable and significantly enhanced biofilm inhibition performance of the zinc substrates implanted with BIVO4. Both biomaterial-based photocatalysts and modified light-driven materials have demonstrated exceptional efficacy in biofilm inhibition, presenting a novel and efficient approach to the advancement of biofilm inhibition technology, while upholding eco-conscious principles.

6.2 Superhydrophobic materials

Superhydrophobic materials, a class of materials celebrated for their exceptional attributes including antifouling, self-cleaning, and high hydrophobicity, have already found significant utility in the contemporary medical field. Drawing inspiration from their remarkable hydrophobicity and antifouling characteristics, these materials hold considerable promise in the domains of biofilm resistance and corrosion prevention. Given that biofilm formation commences with the irreversible attachment of microorganisms, such as bacteria, conferring anti-adhesive properties onto material surfaces represents a direct strategy for impeding biofilm formation (Kumar et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2022). Building upon this foundation, antifouling surface materials have been developed, leveraging hydrophilic polymers (Maan et al. 2020), amphiphilic ionic polymers (He et al. 2016), and low surface energy materials (Li and Guo 2019). However, these materials do come with inherent limitations. Firstly, their antifouling effects tend to be of limited duration. Extensive research has shown that the anti-adhesive properties of conventional superhydrophobic surfaces are transitory. After extended immersion in bacterial suspensions (beyond 24 h), these properties tend to degrade or even vanish (Hwang et al. 2018). Secondly, traditional superhydrophobic materials lack bactericidal capabilities. Once their anti-adhesive properties wane, microorganisms, particularly bacteria, rapidly adhere, colonize, and foster biofilm formation.

To address these challenges and enhance the durability and effectiveness of superhydrophobic materials for biofilm resistance, Lin and colleagues (Lin et al. 2023) have engineered an innovative superhydrophobic photothermal coating rooted in candle soot (CS). The primary constituent of this remarkable coating, CS, comprises carbon nanoparticles derived from the incomplete combustion of candles. This pioneering coating seamlessly integrates the exceptional attributes of superhydrophobicity and photothermal functionality. It not only exhibits potent anti-adhesion properties capable of thwarting biofilm formation but also boasts the unique ability to eradicate residual bacteria residing on surfaces via brief exposure to near-infrared radiation. Similarly, the superhydrophobic coating which is expertly crafted through the fusion of acrylic polyurethane and a hydrophobic zinc oxide bactericidal suspension excels in several domains, possessing outstanding hydrophobicity that effectively inhibits biofilm formation. Additionally, it showcases remarkable resilience when subjected to corrosive environments, including exposure to acidic and alkaline conditions as well as NaCl aqueous solutions. Remarkably, it also harbors inherent antimicrobial capabilities. Rigorous experimental testing further substantiates its exceptional abrasion resistance. Impressively adaptable, this superhydrophobic coating thrives in diverse environments, including marine settings, all while consistently upholding its hydrophobic, bactericidal, and biofilm-resistant attributes (Xie et al. 2021). The development of these groundbreaking superhydrophobic materials aims to curtail biofilm progression at the colonization stage, ultimately realizing the overarching goal of mitigating MIC. The stellar performance of these novel superhydrophobic materials underscores the promising feasibility of applying them in the realm of anti-biofilm strategies.

6.3 Marine biomass

As an environmentally friendly and pollution-free natural resource, marine biomass has emerged as a highly promising reservoir of non-toxic antifouling products. The utilization of marine biomass resources has rapidly gained traction as a cutting-edge research frontier. This invaluable resource encompasses a rich tapestry of marine life, including seaweeds, seagrasses, marine microorganisms, and a diverse array of marine animals. Currently, the treasure trove of extractable marine biomass yields a bounty that includes endolipids, alkaloids, polysaccharides, and fatty acids (Bhadury and Wright 2004; Qian et al. 2009). Furthermore, marine organisms produce natural antimicrobial peptides, a highly potent resource brimming with potential (Choi et al. 2009). These peptides, predominantly composed of D-amino acids, wield the remarkable capacity to stymie the formation of biofilms (Kolodkin-Gal et al. 2010). The vast spectrum of marine life serves as a wellspring for these natural antimicrobial peptides. For instance, investigations have unearthed five distinct antimicrobial peptides within the partial hydrolysates of snow crabs and it has been demonstrated that microorganisms interact with natural organic matter (NOM) in regulating the formation of membranes, limiting biofilm development in terms of activity and bacterial structure (Doiron et al. 2018). Moreover, marine biomass resources offer up compounds such as polyaspartic acid and γ-polyglutamic acid, secreted by microorganisms, renowned for their remarkable dual capacity to retard corrosion and inhibit the insidious advance of biofilms. These multifaceted resources underscore the immense potential of marine biomass in advancing sustainable and environmentally benign solutions.

6.4 Quorum sensing inhibitors

Bacteria, long perceived as solitary unicellular entities engaged in simple self-sustaining activities (Davey et al. 2000), have, in recent years, astounded researchers by showcasing their capacity for collective behavior. This phenomenon involves multiple bacteria, often operating in concert to execute synergistic activities critical for their survival in challenging environments. Such activities encompass a gamut of intricate processes, from the dazzling display of bioluminescence (Bassler et al. 1994; Miyashiro and Ruby 2012) and the uptake of foreign DNA (Okada et al. 2005) to the production of antibiotics (Barnard et al. 2007). The execution of these cooperative endeavors hinges upon the seamless coordination of all participating bacteria within a given microbial community. To attain this remarkable level of synchronization, bacteria have evolved a sophisticated intercellular communication system known as “Quorum sensing” (QS). QS functions as an environmental sensing mechanism through which bacteria meticulously gauge their population density. Subsequently, they orchestrate collective behaviors by deploying a repertoire of chemical signals (Rutherford and Bassler 2012; Ng and Bassler 2009). This remarkable system allows bacteria to act in unison, pooling their collective intelligence to navigate their surroundings and overcome challenges.

Quorum sensing (QS) is contingent upon a delicate interplay involving the production, release, and detection of signaling molecules. In scenarios of low cell density, bacteria generate these signaling molecules, which are subsequently diffused into the surrounding environment. Owing to the effect of diffusion, the concentration of these signaling molecules diminishes, rendering them undetectable. During this phase, individual bacteria maintain their autonomous functionality. However, as bacterial reproduction gains momentum and cell density escalates, a local surge in signaling molecule concentration occurs. Upon reaching a critical threshold, individual bacteria detect these signaling molecules, prompting a shift in their gene expression patterns. This pivotal moment initiates collective behaviors within the bacterial population (Rutherford and Bassler 2012; Ng and Bassler 2009; Bassler 1999). Notably, QS has emerged as a pivotal player in extracellular electron transfer among microorganisms (Chen et al. 2017). It has also been elucidated that QS plays a pivotal role in the formation of biofilms (Alayande et al. 2018; Li and Zhao 2020; Li and Tian 2012; Parsek and Greenberg 2005). Studies focusing on SRB have uncovered that QS inhibitors (QSIs) precipitate a down-regulation in the expression of genes responsible for electron transfer and biofilm formation in microorganisms (Scarascia et al. 2019). QS serves as a multifaceted mechanism that underpins bacterial signaling and electron transfer within biofilms (Li and Tian 2012; Yang et al. 2018). The presence of biofilms and their associated extracellular electron transfer processes accentuates microbial corrosion. Therefore, the inhibition of QS presents an innovative avenue for curtailing biofilm formation and impeding the occurrence of extracellular electron transfer, offering a promising frontier in anti-biofilm technology.

6.5 Corrosion inhibitors

The primary strategy to prevent microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) involves inhibiting the formation and growth of biofilms on metal surfaces. Various methods have been explored to achieve this, among which the application of corrosion inhibitors stands out as the most widely used and effective approach (Olajire 2017). The relative complexity of the marine environment necessitates a more diverse selection of inhibitors, with the choice varying according to specific environmental conditions. For instance: Thioaldehydes, nitrogen-based materials and their derivatives, aldehydes, sulfurcontaining substances, acetylenic compounds, and different alkaloids such as strychnine, quinine, nicotine, and papaverine are all utilized as inhibitors in acidic environment. Potent inhibitors in neutral environment include phosphate, nitrite, benzoate, and chromate. However, the underlying anti-corrosion mechanisms of these inhibitors are largely similar, primarily functioning by reducing or preventing reactions between the metal and various environmental media, thereby achieving corrosion inhibition (Ghosal and Lavanya 2023). While traditional chemical corrosion inhibitors are widely utilized and highly effective, they inevitably pose environmental pollution risks. In recent years, there has been a gradual shift towards replacing harmful inhibitors with environmentally safer alternatives, driven by an increasing awareness of environmental safety.

New green corrosion inhibitors are not only environmentally friendly but also capable of adapting to the dynamic marine environment, providing comprehensive corrosion protection. Lei et al. designed a system capable of limiting bacterial growth and mitigating corrosion effects, proposing a novel method for MIC inhibition. This method utilizes the newly synthesized compound cetrimonium 4-hydroxycinnamate (Cet-4OHCin) in combination with lanthanum 4-hydroxycinnamate. Together, they form an innovative corrosion inhibitor that not only suppresses abiotic corrosion in artificial seawater but also significantly reduces bacterial density during prolonged exposure. Due to the same anion, this corrosion inhibitor remains stable in solution under test conditions, while being virtually harmless to humans and the environment (Catubig et al. 2022). Similarly, the bifunctional antibacterial and anticorrosive broad-spectrum rosin thiourea iminazole quaternary ammonium salt (RTIQAS) inhibited the corrosion of X80 carbon steel induced by anaerobic gramnegative sulfate reducing bacterium D. vulgaris, as well as the corrosion of 316L stainless steel induced by aerobic gram-positive Bacillus licheniformis. A related corrosion inhibitor is the hafnium-based metallosurfactant. Mehta and colleagues (Mehta et al. 2021) synthesized hafnium based surfactant bishexadecylpyridinium hafnium hexachlorate (HfCPC) using a cost-effective ligand insertion method and a straightforward procedure. As a novel environmentally friendly corrosion inhibitor, HfCPC effectively mitigates iron corrosion and is suitable for marine and microbiological environments. Overall, new corrosion inhibitors must not only exhibit enhanced efficiency in corrosion inhibition but also be developed with a focus on environmental sustainability, multifunctional applications, and economic viability, aiming to effectively prevent biofilm formation and growth at its core.

6.6 Anti-bacterial metal material

In recent years, microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) affecting marine structural steel has emerged as a prominent research focus (Xu et al. 2017). Carbon steel (CS) is extensively employed as marine structural steel in maritime settings owing to its commendable mechanical properties and economic viability. Nonetheless, its susceptibility to pitting corrosion is markedly heightened in the presence of microorganisms (Abdolahi et al. 2014). Generally, incorporating a diverse array of alloying elements stands as a dependable approach to augmenting steel’s resistance to biological corrosion (Sun et al. 2021; Wu et al. 2021). Copper exhibits a significant inhibitory effect on microorganism attachment. Consequently, incorporating copper elements into steel confers sterilizing capabilities upon the material (Liu et al. 2018; Lou et al. 2016). A recent study explored the microbial corrosion of marine structural steels (09CrCuSb low alloy steel (LAS) and Q235 carbon steel (CS)) in D. vulgaris medium and P. aeruginosa medium based on seawater was investigated. The 09CrCuSb low-alloy steel (LAS) demonstrated superior corrosion resistance and antimicrobial efficacy compared to Q235 carbon steel (CS). The enhanced performance of 09CrCuSb low-alloy steel (LAS) can be attributed to its higher content of alloying elements (Cr, Ni, Cu, Al, and Sb), which impedes surface biofilm formation and significantly inhibits the growth of adherent cells. Moreover, the reduced number of adherent cells leads to a lower rate of extracellular electron transfer, thereby reducing corrosion incidence (Lu et al. 2023). This study validates the feasibility of enhancing steel’s antimicrobial and corrosion-resistant properties through the addition of alloying elements. Xue and colleagues (Xue et al. 2023) investigated the impact of heat treatment on the corrosion resistance and antimicrobial properties of 0Cr15Ni5Cu3Mo stainless steel. The findings revealed that Cu-containing stainless steel precipitates Cu-rich phases within the matrix following heat treatment. Simultaneously, it has been demonstrated that precipitation of the Cu-rich phase induces a contact potential difference with the steel substrate. This results in lower surface potential of the Cu-rich phase, initiating electron loss and anodic activity, while the higher potential of the steel substrate serves as the cathode (Rahimi et al. 2018). When bacteria encounter this microzone of potential difference, the cathode’s consumption of H+ ions impede bacterial electron transfer and disrupts metabolism, thereby achieving antibacterial effects (Feng et al. 2022). It is noteworthy that this process specifically targets established bacteria, underscoring the importance of sufficient contact between copper-containing stainless steels and bacteria for their antimicrobial efficacy.

7 Prospect

MIC is a multifaceted process driven by complex interactions among various factors. Addressing this challenge necessitates a multidisciplinary approach that integrates biology, materials science, process and electrochemistry, corrosion engineering, and integrity management. Only through the synergistic collaboration of these disciplines can the fundamental mechanisms of MIC be elucidated, leading to the development of rational, effective, and sustainable solutions. Following the successful 2023 High-end Forum on the Construction of the Ocean Destiny Community, China’s marine construction endeavors have seen gradual enhancements. The ocean, brimming with energy and abundant resources, is slated for further sustainable development and utilization. Within the fiercely competitive international marine landscape, marine corrosion mitigation has risen to prominence as a safeguard for marine engineering projects. Microbial corrosion and biofouling, focal points in the realm of marine corrosion research, present significant safety challenges to offshore steel infrastructure and essential facilities such as docks and ports. The pivotal catalyst for MIC lies in the attachment and colonization of biofilms. Therefore, effective strategies to inhibit biofilm formation assume paramount importance in averting extensive microorganism adhesion and effectively mitigating MIC. Presently, substantial progress has been made in the study of biofilm formation and its developmental processes. However, there remains a relative dearth of research concerning the factors that influence biofilm formation and development. Looking ahead, we can initiate investigations from the perspective of these factors, elucidate the laws and mechanisms governing biofilm development, and spearhead the development of novel technologies in this domain.

Traditional methods for inhibiting biofilm formation have often been plagued by issues of environmental pollution and limitations in their effectiveness over time. Fortunately, recent advances in anti-biofilm technology have introduced innovative approaches aimed at reducing biofilm adhesion, curtailing biofilm development, and exhibiting antibacterial and bacteriostatic properties. These emerging technologies are characterized by their environmentally friendly nature and high efficiency. The challenge now facing anti-biofilm technology is the harmonious integration of these cutting-edge techniques and products. Striking a balance between synthetic and natural approaches is paramount in the quest to develop comprehensive solutions for biofilm inhibition.

Simultaneously, the advent of novel technologies inevitably poses challenges to conventional methods. Ensuring that these new technologies can be efficiently scaled up for mass production while systematically phasing out outdated, polluting, and inefficient traditional techniques is our primary focus at present. This progressive shift involves the gradual substitution of traditional technologies with state-of-the-art alternatives and the replacement of traditional materials with innovative ones. Through these measures, anti-biofilm technology is steadily advancing toward a path characterized by environmental sustainability, heightened efficiency, and eco-friendliness.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, J.Z.; methodology, Z.Z.Y.; software, J.D. and B.H.; validation, Z.Z.Y., J.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Z.Y.; organic metabolites analysis, Z.Z.Y. and J.Z.; investigation, Z.Z.Y.; resources, J.D. and J.Z.; writing – original draft preparation, Z.Z.Y. and J.Z.; writing – review and editing, F.Y.W., K.M.; visualization, Z.Z.Y.; supervision, J.D. and J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

Abdoli, L., Suo, X., and Li, H. (2016). Distinctive colonization of Bacillus sp. bacteria and the influence of the bacterial biofilm on electrochemical behaviors of aluminum coatings. Colloids. Surf. B 145: 688–694, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.05.075.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Abdolahi, A., Hamzah, E., Ibrahim, Z., and Hashim, S. (2014). Microbially influenced corrosion of steels by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Corros. Rev. 32: 129–141, https://doi.org/10.1515/corrrev-2013-0047.Suche in Google Scholar

AlAbbas, F.M., Williamson, C., Bhola, S.M., Spear, J.R., Olson, D.L., Mishra, B., and Kakpovbia, A.E. (2013). Influence of sulfate reducing bacterial biofilm on corrosion behavior of low-alloy, high-strength steel (API-5L X80). Int. Biodeterior. Biodegr. 78: 34–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.10.014.Suche in Google Scholar

Alayande, A.B., Aung, M.M., and Kim, I.S. (2018). Correlation between quorum sensing signal molecules and pseudomonas aeruginosa’s biofilm development and virulency. Curr. Microbiol. 75: 787–793, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-018-1449-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Allison, D.G. and Gilbert, P. (1995). Modification by surface association of antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial populations. J. Ind. l Microbiol. 15: 311–317, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01569985.Suche in Google Scholar

Antunes, J., Leão, P., and Vasconcelos, V. (2019). Marine biofilms: diversity of communities and of chemical cues. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 11: 287–305, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12694.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Anutrakunchai, C., Bolscher, J.G.M., Krom, B.P., Kanthawong, S., and Taweechaisupapong, S. (2018). Impact of nutritional stress on drug susceptibility and biofilm structures of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia thailandensis grown in static and microfluidic systems. Plos. One. 13: e0194946, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194946.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Anwar, H., Strap, J.L., and Costerton, J.W. (1992). Establishment of aging biofilms possible mechanism of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrob. Agents. Ch. 36: 1347–1351, https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.36.7.1347.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Armstrong, E., Rogerson, A., and Leftley, J. (2000). Utilisation of seaweed carbon by three surface-associated heterotrophic protists, Stereomyxa ramosa, Nitzschia alba and Labyrinthula sp. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 21: 49–57, https://doi.org/10.3354/ame021049.Suche in Google Scholar

Barnard, A.M.L., Bowden, S.D., Burr, T., Coulthurst, S.J., Monson, R.E., and Salmond, G.P.C. (2007). Quorum sensing, virulence and secondary metabolite production in plant soft-rotting bacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 362: 1165–1183, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bassler, B.L. (1999). How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2: 582–587, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00025-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Bassler, B.L., Wright, M., and Silverman, M.R. (1994). Multiple signalling systems controlling expression of luminescence in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes encoding a second sensory pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 13: 273–286, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00422.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Beech, I., Sztyler, M., Gaylarde, C., Smith, W., and Sunner, J. (2014) Biofilms and biocorrosion. In: Beech, I. (Ed.), Understanding biocorrosion. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 33–56.10.1533/9781782421252.1.33Suche in Google Scholar

Beech, I.B. and Sunner, J. (2004). Biocorrosion: towards understanding interactions between biofilms and metals. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15: 181–186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2004.05.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Belkaid, S., Ladjouzi, M.A., and Hamdani, S. (2011). Effect of biofilm on naval steel corrosion in natural seawater. J. Solid State Electrochem. 15: 525–537, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-010-1118-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhadury, P. and Wright, P.C. (2004). Exploitation of marine algae: biogenic compounds for potential antifouling applications. Planta 219: 561–578, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-004-1307-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Busalmen, J.P., Vázquez, M., and De Sánchez, S.R. (2002). New evidences on the catalase mechanism of microbial corrosion. Electrochim. Acta 47: 1857–1865, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4686(01)00899-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Catubig, R.A., Michalczyk, A., Neil, W.C., McAdam, G., Forsyth, J., Ghorbani, M., Yunis, R., Ackland, M.L., Forsyth, M., and Somer, A.E. (2022). Inhibitor mixture for reducing bacteria growth and corrosion on marine steel. Aust. J. Chem. 75: 619–630, https://doi.org/10.1071/ch21266.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, S., Jing, X., Tang, J., Fang, Y., and Zhou, S. (2017). Quorum sensing signals enhance the electrochemical activity and energy recovery of mixed-culture electroactive biofilms. Biosens. Bioelectron. 97: 369–376, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2017.06.024.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Choi, O., Clevenger, T.E., Deng, B., Surampalli, R.Y., Ross, Jr., L., and Hu, Z. (2009). Role of sulfide and ligand strength in controlling nanosilver toxicity. Water Res. 43: 1879–1886, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2009.01.029.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Croft, M.T., Lawrence, A.D., Raux-Deery, E., Warren, M.J., and Smith, A.G. (2005). Algae acquire vitamin B12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438: 90–93, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04056.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Dannenberg, S., Kroder, M., Dilling, W., and Cypionka, H. (1992). Oxidation of H2, organic compounds and inorganic sulfur compounds coupled to reduction of O2 or nitrate by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 158: 93–99, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00245211.Suche in Google Scholar

Davey, M.E., O’toole, G.A. (2000). Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbio. Mol. Bio. Rev. 64: 847–867, https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.64.4.847-867.2000.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Doiron, K., Beaulieu, L., St-Louis, R., and Lemarchand, K. (2018). Reduction of bacterial biofilm formation using marine natural antimicrobial peptides. Colloids Surf. B 167: 524–530, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.04.051.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Dong, Y., Jiang, B., Xu, D., Jiang, C., Li, Q., and Gu, T. (2018). Severe microbiologically influenced corrosion of S32654 super austenitic stainless steel by acid producing bacterium Acidithiobacillus caldus SM-1. Bioelectrochemistry 123: 34–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2018.04.014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Dong, Z.H., Liu, T., and Liu, H.F. (2011). Influence of EPS isolated from thermophilic sulphate-reducing bacteria on carbon steel corrosion. Biofouling 27: 487–495, https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2011.584369.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Eckert, R.B. (2015). Emphasis on biofilms can improve mitigation of microbiologically influenced corrosion in oil and gas industry. Corros. Eng. Sci. Techn. 50: 163–168, https://doi.org/10.1179/1743278214y.0000000248.Suche in Google Scholar

Enning, D. and Garrelfs, J. (2014). Corrosion of iron by sulfate-reducing bacteria: new views of an old problem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80: 1226–1236, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02848-13.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Feng, J., Tong, S.Y., Thian, E.S., Yang, C., Yang, K., Gong, N., Misra, K.P., and Misra, R.D.K. (2022). Nanostructuring of biomaterials and reducing implant related infections via incorporation of silver and copper as antimicrobial elements: an overview. Mater. Technol. 37: 867–879, https://doi.org/10.1080/10667857.2022.2080347.Suche in Google Scholar

Ferrer, M., Méndez-García, C., Bargiela, R., Chow, J., Alonso, S., García-Moyano, A., Bjerga, G.E.K., Steen, I.H., Schwabe, T., Blom, C., et al.. (2019). Decoding the ocean’s microbiological secrets for marine enzyme biodiscovery. Fems Microbiol. Lett. 366: 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fny285.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Fida, T.T., Chen, C., Okpala, G., and Voordouw, G. (2016) Implications of limited thermophilicity of nitrite reduction for control of sulfide production in oil reservoirs. In: Löffler, F.E. (Ed.), Appl Environ Microb. American Society For Microbiology, Washington, pp. 4190–4199.10.1128/AEM.00599-16Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Fitridge, I., Dempster, T., Guenther, J., and De Nys, R. (2012). The impact and control of biofouling in marine aquaculture: a review. Biofouling 28: 649–669, https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2012.700478.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Flemming, H.-C. and Wingender, J. (2010). The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8: 623–633, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2415.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Ghosal, J. and Lavanya, M. (2023). Inhibition of microbial corrosion by green inhibitors: an Overview. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 124: 684–703.Suche in Google Scholar

Gieg, L.M., Jack, T.R., and Foght, J.M. (2011). Biological souring and mitigation in oil reservoirs. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 92: 263–282, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3542-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Gu, T. (2014). Theoretical modeling of the possibility of acid producing bacteria causing fast pitting biocorrosion. J. Microb. 6: 68–74, https://doi.org/10.4172/1948-5948.1000124.Suche in Google Scholar

Gu, T., Jia, R., Unsal, T., and Xu, D. (2019). Toward a better understanding of microbiologically influenced corrosion caused by sulfate reducing bacteria. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35: 631–636, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2018.10.026.Suche in Google Scholar

Gu, T., Rastegar, S.O., Mousavi, S.M., Li, M., and Zhou, M. (2018). Advances in bioleaching for recovery of metals and bioremediation of fuel ash and sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol 261: 428–440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.04.033.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hall-Stoodley, L., Costerton, J.W., and Stoodley, P. (2004). Bacterial biofilms: from the Natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2: 95–108, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro821.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hawkins, M.L., Schott, S.S., Grigoryan, B., Rufin, M.A., Ngo, B.K.D., Vanderwal, L., Stafslien, S.J., and Grunlan, M.A. (2017). Anti-protein and anti-bacterial behavior of amphiphilic silicones. Polym. Chem. 8: 5239–5251, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7py00944e.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

He, M., Gao, K., Zhou, L., Jiao, Z., Wu, M., Cao, J., You, X., Cai, Z., Su, Y., and Jiang, Z. (2016). Zwitterionic materials for antifouling membrane surface construction. Acta Biomater. 40: 142–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.03.038.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Hou, B., Li, X., Ma, X., Du, C., Zhang, D., Zheng, M., Xu, W., Lu, D., and Ma, F. (2017). The cost of corrosion in China. Npj. Mat. Degrad. 1: 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-017-0005-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Hou, S., Pu, Y.A., Chen, S.G., Lv, G.J., Wang, W., and Li, W.(2024). Mitigation effects of ammonium on microbiologically influenced corrosion of 90/10 copper-nickel alloy caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2024.105762.Suche in Google Scholar

Hwang, G.B., Page, K., Patir, A., Nair, S.P., Allan, E., and Parkin, I.P. (2018). The anti-biofouling properties of superhydrophobic surfaces are short-lived. ACS Nano 12: 6050–6058, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.8b02293.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Iverson, W. (1987). Microbial corrosion of metals. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 32: 1–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70077-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Jia, B., Mei, Y., Cheng, L., Zhou, J., and Zhang, L. (2012). Preparation of copper nanoparticles coated cellulose films with antibacterial properties through one-step reduction. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 4: 2897–2902, https://doi.org/10.1021/am3007609.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Jia, R., Unsal, T., Xu, D., Lekbach, Y., and Gu, T. (2019). Microbiologically influenced corrosion and current mitigation strategies: a state of the art review. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 137: 42–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.11.007.Suche in Google Scholar

Jin, Y., Zhou, E., Ueki, T., Zhang, D., Fan, Y., Xu, D., Wang, F., and Lovley, D.R. (2023). Accelerated microbial corrosion by magnetite and electrically conductive pili through direct Fe0-to-Microbe electron transfer. Angew 135: e202309005, https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202309005.Suche in Google Scholar

Kolodkin-Gal, I., Romero, D., Cao, S., Clardy, J., Kolter, R., and Losick, R. (2010). d -Amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Sci. 328: 627–629, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188628.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kryachko, Y. and Hemmingsen, S.M. (2017). The role of localized acidity generation in microbially influenced corrosion. Curr. Microbiol. 74: 870–876, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-017-1254-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Kumar, S., Roy, D.N., and Dey, V. (2021). A comprehensive review on techniques to create the anti-microbial surface of biomaterials to intervene in biofouling. Colloid. Interfac. Sci. 43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colcom.2021.100464.Suche in Google Scholar

Lahme, S., Mand, J., Longwell, J., Smith, R., and Enning, D. (2021). Severe corrosion of carbon steel in oil field produced water can be linked to methanogenic archaea containing a special type of [NiFe] hydrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microb. 87: e01819–e01820, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01819-20.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lekbach, Y., Liu, T., Li, Y ., Moradi, M., Dou, W., Xu, D., Smith, J.A., and Lovley, D.R. (2021). Microbial corrosion of metals: the corrosion microbiome. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 78: 317–390, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ampbs.2021.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lewandowski, Z. (Ed.) (2000). Proceedings of the CORROSION 2000, March 26–31, MIC and Biofilm Heterogeneity. NACE International, Florida.10.5006/C2000-00400Suche in Google Scholar

Li, J. and Zhao, X. (2020). Effects of quorum sensing on the biofilm formation and viable but non-culturable state. Food Res. Int. 137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109742.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Li, P., Zhao, Y, Liu, Y., Zhao, Y, Xu, D., Yang, C., Zhang, T., Gu, T., and Yang, K. (2017). Effect of Cu addition to 2205 buplex stainless steel on the resistance against pitting corrosion by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 33: 723–727, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2016.11.020.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Q.-C., Wang, B., Zeng, Y.-H., Cai, Z.-H., and Zhou, J. (2022). The microbial mechanisms of a novel photosensitive material (treated rape pollen) in anti-biofilm process under marine environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23: 3837, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23073837.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Li, Y. and Ning, C. (2019). Latest research progress of marine microbiological corrosion and bio-fouling, and new approaches of marine anti-corrosion and anti-fouling. Bioact. Mater. 4: 189–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2019.04.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Li, Y., Wan, M., Du, J., Lin, L., Cai, W., and Wang, L. (2020). Microbial enhanced corrosion of hydraulic concrete structures under hydrodynamic conditions: microbial community composition and functional prediction. Constr. Build. Mater. 248, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118609.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Y., Xu, D., Chen, C., Li, X., Jia, R., Zhang, D., Sand, W., Wang, F., and Gu, T. (2018). Anaerobic microbiologically influenced corrosion mechanisms interpreted using bioenergetics and bioelectrochemistry: a review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 34: 1713–1718, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2018.02.023.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Y.-H. and Tian, X. (2012). Quorum sensing and bacterial social interactions in biofilms. Sensors 12: 2519–2538, https://doi.org/10.3390/s120302519.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Li, Z. and Guo, Z. (2019). Bioinspired surfaces with wettability for antifouling application. Nanoscale 11: 22636–22663, https://doi.org/10.1039/c9nr05870b.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lin, Y., Zhang, H., Zou, Y., Lu, K., Li, L., Wu, Y., Cheng, J., Zhang, Y., Chen, H., and Yu, Q. (2023). Superhydrophobic photothermal coatings based on candle soot for prevention of biofilm formation. J. Mater. Sci. Tech-Lond. 132: 18–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2022.06.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Lou, Y., Chang, W., Cui, T., Wang, J., Qian, H., Ma, L., Hao, X., and Zhang, D. (2021). Microbiologically influenced corrosion inhibition mechanisms in corrosion protection: a review. Bioelectrochemistry 141, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2021.107883.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lou, Y., Lin, L., Xu, D., Zhao, S., Yang, C., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., Gu, T., and Yang, K. (2016). Antibacterial ability of a novel Cu-bearing 2205 duplex stainless steel against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm in artificial seawater. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 110: 199–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.03.026.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, J., Jia, R., Zhou, E., Zhao, Y., Dou, W., Xu, D., Yang, K., and Gu, T. (2018). Antimicrobial Cu-bearing 2205 duplex stainless steel against MIC by nitrate reducing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Int. Biodeter. biodegr. 132: 132–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Lu, S., He, Y., Xu, R., Wang, N., Chen, S., Dou, W., Cheng, X., and Liu, G. (2023). Inhibition of microbial extracellular electron transfer corrosion of marine structural steel with multiple alloy elements. Bioelectrochemistry 151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2023.108377.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Lv, M. and Du, M. (2018). A review: microbiologically influenced corrosion and the effect of cathodic polarization on typical bacteria. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio. 17: 431–446, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-018-9473-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Lv, M., Du, M., Li, X., Yue, Y.Y., and Chen, X.C. (2019). Mechanism of microbiologically influenced corrosion of X65 steel in seawater containing sulfate-reducing bacteria and iron-oxidizing bacteria. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 8: 4066–4078, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.07.016.Suche in Google Scholar

Lv, M., Yue, Y.Y., Li, Z.X., and Du, M. (2021). Effect of cathodic polarization on corrosion behavior of X65 steel in seawater containing Iron-oxidizing Bacteria. Int. J. Electrochem. SC 16: 150968, https://doi.org/10.20964/2021.01.42.Suche in Google Scholar

Lv, M., Du, M., and Li, Z.X. (2022). Investigation of mixed species biofilm on corrosion of X65 steel in seawater environment. Bioelectrochemistry 143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2021.107951.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Ma, F., Li, J., Zeng, Z., and Gao, Y. (2019). Tribocorrosion behavior in artificial seawater and anti-microbiologically influenced corrosion properties of TiSiN-Cu coating on F690 steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35: 448–459, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2018.09.038.Suche in Google Scholar

Maan, A.M.C., Hofman, A.H., Vos, W.M., and Kamperman, M. (2020). Recent developments and practical feasibility of polymer‐based antifouling coatings. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30: 2000936, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202000936.Suche in Google Scholar

McNamara, C.J., Bearce Lee, K., Russell, M.A., Murphy, L.E., and Mitchell, R. (2009). Analysis of bacterial community composition in concretions formed on the USS Arizona, Pearl Harbor, HI. J. Cult. Herit. 10: 232–236, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2008.07.010.Suche in Google Scholar

Mehta, H., Kaur, G., Chaudhary, G.R., and Prabhakar, N. (2021). Assessment of bio-corrosion inhibition ability of Hafnium based cationic metallosurfactant on iron surface. Corros. Sci. 179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.109101.Suche in Google Scholar

Miyashiro, T. and Ruby, E.G. (2012). Shedding light on bioluminescence regulation in Vibrio fischeri: shedding light on bioluminescence regulation in Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbio. 84: 795–806, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08065.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ng, W.-L. and Bassler, B.L. (2009). Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43: 197–222, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Okada, M., Sato, I., Cho, S.J., Iwata, H., Nishio, T., Dubnau, D., and Sakagami, Y. (2005). Structure of the bacillus subtilis quorum-sensing peptide pheromone ComX. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1: 23–24, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio709.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Olajire, A.A. (2017). Corrosion inhibition of offshore oil and gas production facilities using organic compound inhibitors – a review. J. Mol. Liq. 248: 775–808, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2017.10.097.Suche in Google Scholar

Parsek, M.R. and Greenberg, E.P. (2005). Sociomicrobiology: the connections between quorum sensing and biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 13: 27–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Peres, R.S., Armelin, E., Moreno-Martínez, J.A., Alemán, C., and Ferreira, C.A. (2015). Transport and antifouling properties of papain-based antifouling coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 341: 75–85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.03.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Pinel, I., Biškauskaitė, R., Pal’ová, E., Vrouwenvelder, H., and Van Loosdrecht, M. (2021). Assessment of the impact of temperature on biofilm composition with a laboratory heat exchanger module. Microorganisms 9: 1185, https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061185.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pu, Y., Dou, W., Gu, T., Tang, S., Han, X., and Chen, S. (2020). Microbiologically influenced corrosion of Cu by nitrate reducing marine bacterium pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 47: 10–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.02.008.Suche in Google Scholar

Qian, P.-Y., Xu, Y., and Fusetani, N. (2009). Natural products as antifouling compounds: recent progress and future perspectives. Biofouling 26: 223–234, https://doi.org/10.1080/08927010903470815.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Qin, L., Hafezi, M., Yang, H., Dong, G., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Constructing a dual-function surface by microcasting and nanospraying for efficient drag reduction and potential antifouling capabilities. Micromachines-Basel. 10: 490, https://doi.org/10.3390/mi10070490.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rahimi, E., Rafsanjani-Abbasi, A., Imani, A., Hosseinpour, S., and Davoodi, A. (2018). Correlation of surface Volta potential with galvanic corrosion initiation sites in solid-state welded Ti-Cu bimetal using AFM-SKPFM. Corros. Sci. 140: 30–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.06.026.Suche in Google Scholar

Rao, T.S., Sairam, T.N., Viswanathan, B., and Nair, K.V.K. (2000). Carbon steel corrosion by iron oxidising and sulphate reducing bacteria in a freshwater cooling system. Corros. Sci. 42: 1417–1431, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-938x(99)00141-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Ray, R., Lee, J., and Little, B. (Eds.), (2010). Proceedings of the CORROSION 2010, March 14-18, 2010: iron-oxidizing bacteria: a review of corrosion mechanisms in fresh water and marine environments. NACE, San Antonio.10.5006/C2010-10218Suche in Google Scholar

Ray, R., Lee, J., and Little, B. (2009). Factors contributing to corrosion of steel pilings in duluth-superior harbor. Corros 65: 707–717, https://doi.org/10.5006/1.3319097.Suche in Google Scholar

Rijavec, T., Zrimec, J., Spanning, R., and Lapanje, A. (2019). Natural microbial communities can be manipulated by artificially constructed biofilms. Adv. Sci. 6: 1901408, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201901408.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rohwerder, T., Gehrke, T., Kinzler, K., and Sand, W. (2003). Bioleaching review part A: progress in bioleaching: fundamentals and mechanisms of bacterial metal sulfide oxidation. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 63: 239–248, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-003-1448-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Rutherford, S.T. and Bassler, B.L. (2012). Bacterial quorum sensing: its role in virulence and possibilities for its control. Csh. Perspect. Med. 2: 705–709, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a012427.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Salgar-Chaparro, S.J., Lepkova, K., Pojtanabuntoeng, T., Darwin, A., and Machuca, L.L. (2020). Nutrient level determines biofilm characteristics and subsequent impact on microbial corrosion and biocide effectiveness. Appl. Environ. Microb. 86: 028855–e2919, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02885-19.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sand, W. (2003). Microbial life in geothermal waters. Geothermics 32: 655–667, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0375-6505(03)00058-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Sun, M., Du, C., Liu, C., Wu, Y., and Li, X. (2021). Fundamental understanding on the effect of Cr on corrosion resistance of weathering steel in simulated tropical marine atmosphere. Corros. Sci. 186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109427.Suche in Google Scholar

Scarascia, G., Lehmann, R., Machuca, L.L., Morris, C., Cheng, K.Y., Kaksonen, A., and Hong, P.-Y. (2019). Effect of quorum sensing on the ability of Desulfovibrio vulgaris to form biofilms and to biocorrode carbon steel in saline conditions. Appl. Environ. Microb. 86: 016644–19, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01664-19.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sherar, B.W.A., Power, I.M., Keech, P.G., Mitlin, S., Southam, G., and Shoesmith, D.W. (2011). Characterizing the effect of carbon steel exposure in sulfide containing solutions to microbially induced corrosion. Corros. Sci. 53: 955–960, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2010.11.027.Suche in Google Scholar

Vivier, B., Claquin, P., Lelong, C., Lesage, Q., Peccate, M., Hamel, B., Georges, M., Bourguiba, A., Sebaibi, N., Boutouil, M., et al.. (2021). Influence of infrastructure material composition and microtopography on marine biofilm growth and photobiology. Biofouling 37: 740–756, https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2021.1959918.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

Vroom, J.M., De Grauw, K.J., Gerritsen, H.C., Bradshaw, D.J., Marsh, P.D., Watson, G.K., Birmingham, J.J., and Allison, C. (1999). Depth penetration and detection of pH gradients in biofilms by two-photon excitation microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microb. 65: 3502–3511, https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.65.8.3502-3511.1999.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wan, H., Song, D., Zhang, D., Du, C., Xu, D., Liu, Z., Ding, D., and Li, X. (2018). Corrosion effect of Bacillus cereus on X80 pipeline steel in a Beijing soil environment. Bioelectrochemistry 121: 18–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2017.12.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed