Abstract

Iron corrosion in acidic environments poses a significant challenge in various industries. This study explores the relationship between theoretical parameters and experimental data for organic corrosion inhibitors applied to iron surfaces in 1 M HCl solution at 25 °C. The review analyzes studies employing various techniques, primarily Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), to assess inhibitor efficiency (IE%). Key theoretical parameters like E binding (interaction strength) and ΔN (electron transfer) are investigated for their ability to predict IE%. The findings reveal a strong correlation between experimental IE% and E binding, suggesting the potential of E binding as a reliable predictor of inhibitor performance before experimentation. While ΔN demonstrates promise in evaluating inhibitor effectiveness, further validation is necessary. Furthermore, the review emphasizes the possibility of using a single standardized method like EIS for inhibitor efficiency evaluation due to consistent results observed across studies with standardized conditions. Additionally, the influence of factors like molecular structure, surface interactions, and temperature on inhibitor effectiveness is highlighted. Higher inhibitor concentrations and lower temperatures generally resulted in improved corrosion inhibition. This review underscores the importance of a combined theoretical and experimental approach for the development of efficient and optimized corrosion inhibitors for iron in acidic environments.

1 Introduction

Corrosion is a common problem for industrial metals and directly impacts their cost and safety. Extensive literature surveys reveal that research on corrosion inhibition for materials containing iron is common. Iron-based materials are widely used for their durability, affordability, and extensive application in various industries. Nevertheless, they frequently face corrosion issues because of iron’s inherent reactivity. This is particularly prevalent in chemical and petrochemical industries where direct contact with strong acidic solutions shortens their service life and poses risks of serious accidents (Choi et al. 2005; Finšgar and Jackson 2014; Kermani and Morshed 2003; Li et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2017; Negm et al. 2012; Sá Brito et al. 2012; Selvakumar et al. 2013).

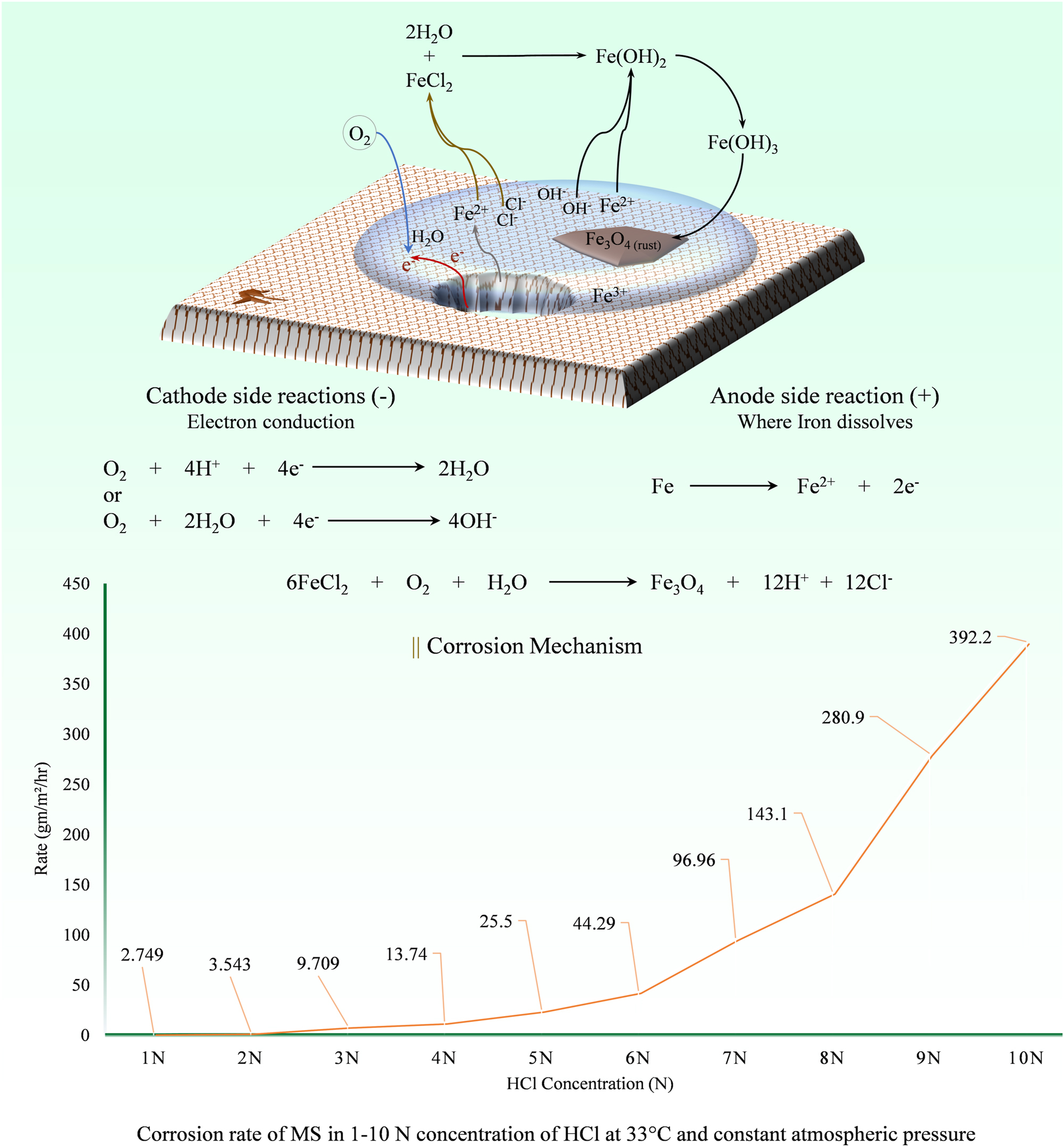

The media commonly employed for studying the corrosion inhibition ability of corrosion inhibitors, as found in various literature, is primarily 1.0 M HCl solution. This preference is due to the high solubility of most metal chlorides in water, treating corroded iron with HCl solution is effective because the acid reacts with and dissolves a wide variety of corrosion products, including oxides, hydroxides, and carbonates, thus cleaning the surface of the iron. HCl solution is utilized as an acid detergent in chemical cleaning processes, with a standardized concentration of 1.0 M HCl. Notably, in Mild Steel (MS)/HCl solution systems, the dissolution rate of iron oxide with HCl is over three times faster than with H2SO4 and significantly surpasses rates with HNO3, HClO4, citric acid, formic acid, and acetic acid (Kuzin et al. 2013; Lozano et al. 2014). Hence, the well-recognized use of efficient, safe, and low-cost HCl as an acid detergent. Indeed, it is crucial to acknowledge that the corrosion rate of steel in HCl is directly proportional to the concentration of HCl and temperature (Figure 1) (Mathur and Vasudevan 1982). This highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate corrosion inhibitor during the pickling process (Al-Moubaraki et al. 2020; Deng and Li 2012; Srivastava 2015).

Mechanism of iron corrosion in HCl solution and the graph of corrosion rate of MS in 1–10 N concentration of HCl at 33 °C and constant atmospheric pressure (Mathur and Vasudevan 1982).

The selection of corrosion inhibitors is contingent upon the specific metal substrate and the prevailing environmental conditions, including solvent nature, temperature, and solution pH. Simultaneously, factors such as economy, efficacy, and environmental impact play a crucial role in the decision-making process (Crossland et al. 2011; De Reus and Simon Thomas 2002; García et al. 2010). Currently, identifying inhibitors that are both inexpensive and easy to synthesize, highly efficient, and nontoxic poses a challenge (Askari et al. 2021). The literature categorizes corrosion inhibitors into two main groups: organic compounds and their inorganic counterparts. Organic compounds, as corrosion inhibitors, may partially fulfill the aforementioned requirements when compared to certain inorganic counterparts like phosphate and nitrate (Abdallah et al. 2006; Serdaroğlu and Kaya 2021). Furthermore, the inhibition mechanisms of organic compounds differ, as they can interact physically, chemically, or both with metal surfaces, thereby restricting cathodic, anodic, or both reaction rates by obstructing active sites. The literature explains this distinction, wherein physical interaction involves the adsorption of inhibitor molecules on a metal surface through van der Waals or Coulombic forces. Chemical interaction, on the other hand, entails elements like sulfur (S), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), oxygen (O), and various conjugated groups (functional groups, heteroatoms, benzenoid and unsaturated multiple bonds, etc.) within organic inhibitors serving as adsorption centers. These centers link the inhibitor (donating electrons) to the metal surface (accepting electrons). Both the surface adsorption of molecules and the bonding between them contribute to corrosion inhibition. In contrast, for inorganic salts, corrosion inhibition primarily occurs by passivating the metal surface to form a protective oxide film against the corrosive environment (Kadhim et al. 2021; Dariva and Galio 2014; Ma et al. 2021; Oguzie et al. 2011).

Organic compounds as corrosion inhibitors found their origins in the petroleum industry during the 1950s and have since gained widespread use (Wu et al. 2013). Ongoing research explores a wide array of organic compounds as potential corrosion inhibitors. These include natural and synthetic varieties such as aliphatic and aromatic compounds, pharmaceutical molecules, ionic liquids, surfactants, plant extracts, polymers, and hybrid formulations with inorganic salts or polymeric nanoparticles (Chauhan et al. 2021; Chidiebere et al. 2012; Hooshmand Zaferani et al. 2013). Alternatively, various experimental techniques and theoretical analysis methods have been employed to enhance the validity of findings related to inhibition efficiency (IE%), inhibition mechanisms, and the molecular structure of inhibitors. Experimental methods, such as weight loss (WL), potentiodynamic polarization (PDP), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and hydrogen evaluation (HE), are utilized to investigate inhibition efficiency. Theoretical analysis methods, including adsorption isotherms, thermodynamic parameters, quantum mechanical calculations, molecular dynamics (MDs), and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, along with their corresponding models and parameters, are employed to probe the inhibition mechanism. Additionally, physico-chemical structures are investigated using characterization techniques such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), UV–visible spectroscopy (UV), X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRD), mass spectrometry, energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and more (Jamil et al. 2018; Obot et al. 2015; Oguzie et al. 2011; Samuel et al. 2023).

Numerous reviews cover diverse aspects of corrosion, including inhibitors, mechanisms, environmental conditions, surfaces, and methodologies (Borchers and Pieler 2010; Chen et al. 2022; Desai et al. 2023; Kadhim et al. 2021; Obot et al. 2015; Samuel et al. 2023; Umoren and Solomon 2017; Verma et al. 2018a; Winkler 2017).

This review provides a comprehensive comparison between experimental and computational data, examining the effectiveness of various organic compounds as corrosion inhibitors in acidic mediums, particularly on iron-containing materials.

2 Corrosion and inhibition mechanism

2.1 Corrosion mechanism

Corrosion is a complex process influenced by factors like temperature, pressure, and electrolyte aggressiveness. Metals react with the environment, transforming into more stable corrosion products. The corrosion rate depends on the change in standard Gibbs free energy (ΔGᴼ), where a more negative ΔGᴼ leads to a higher corrosion rate. Corrosion products, such as rusts and scales, act as physical barriers, affecting the corrosion rate (Mazères et al. 2016; Verma et al. 2017, 2018a,c; Yu et al. 2015). The Pilling–Bedworth ratio (Md/nmD), determined by the metal and corrosion product properties, influences whether the physical barrier is inhibitive or noninhibitive. If Md/nmD < 1, the corrosion product volume is smaller than the metal, resulting in a nonprotective film. Conversely, if Md/nmD > 1, the corrosion product volume exceeds the metal, creating an inhibitive and compact protective film (Cao et al. 2016; Douglass 1969; Goyal et al. 2018).

Corrosion, a localized electrochemical process involving the release of electrons due to metal dissolution, results in gradual degradation and eventual structural failure. In the context of Steel/HCl solution systems, comprehending the corrosion mechanism is imperative before engaging in the assessment of corrosion inhibition methodologies. The corrosion of iron entails anodic reactions, as encapsulated by the chemical reaction in Equation (1), further delineated in Equations (2)–(7) (Dasgupta 2013; Evans 1967; Pletnev 2020). Iron dissolution in acidic solutions entails the release of positive Fe ions and the generation of free electrons traversing through the metal. Adsorbed intermediates, namely [FeOH]ads and [FeClOH]ads, play a pivotal role in the rate-determining step, as delineated by mechanisms (ii) and (iii). Notably, the reliance of iron dissolution on H+ ions vis-a-vis Cl− ions in HCl solutions is underscored, with the corrosion rate exhibiting pH dependency at elevated Cl− ion activity. In acidic environments, the anode accumulates excess electrons, which are neutralized at the cathodic site through the reduction of H+ ions, yielding H2 gas Equations (8)–(10) (Figure 1) (Finšgar and Jackson 2014; Selvakumar et al. 2013). Corrosion rate assessments for MS subjected to varied HCl concentrations reveal an accelerated dissolution trend, exhibiting correlation with HCl concentration (Figure 1) (Mathur and Vasudevan 1982).

(ii) Aqueous solutions (oxidative dissolution):

(iii) Aqueous solutions containing Cl− ions (oxidative dissolution):

2.2 Inhibition mechanism

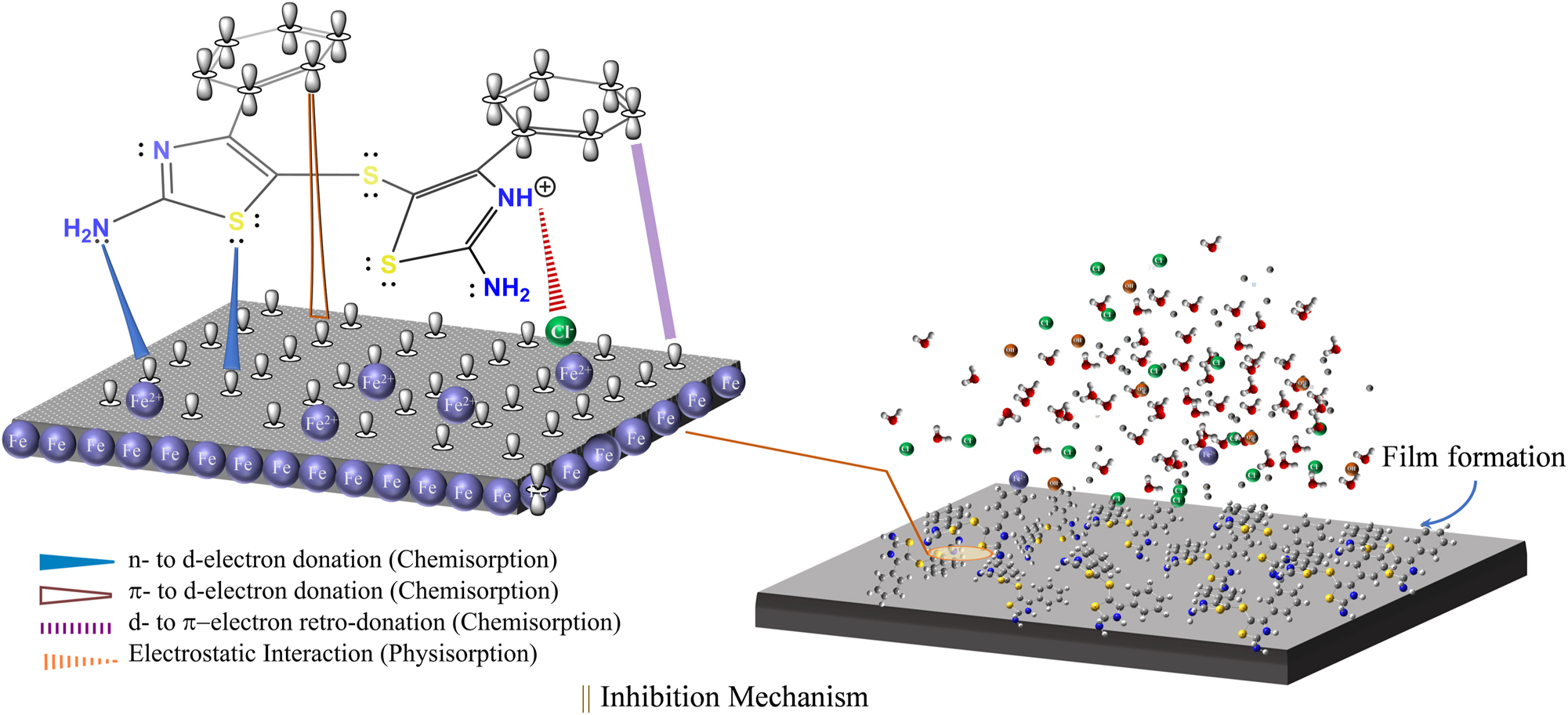

The adsorption mechanism of corrosion inhibition involves organic compounds adsorbing onto the metal/solution interface, forming a protective layer that blocks active sites (Figure 2) (Verma et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2023b). The overall efficiency of corrosion inhibitors is influenced by inhibitor characteristics (molecular structure, charge, polarity, concentration, and stability), environmental factors (corrosive medium, temperature, pH, and hydrodynamics), and metal surface properties (metal type, surface condition, and surface potential) (Afshari et al. 2023; Assad and Kumar 2021; Dehghani et al. 2023; Harvey et al. 2018; Verma and Quraishi 2022; Wasim et al. 2018). Organic inhibitors with heteroatoms (S, N, P, and O) are effective in harsh environments and follow isotherms like Langmuir, Temkin, Freundlich, and Frumkin. The adsorption is akin to a quasi-substitution reaction between water and inhibitor molecules at the corroding interface, significantly reducing the corrosion rate in acidic solutions by forming a protective layer on the metal surface (Sato 2011; Selvakumar et al. 2013).

Inhibition mechanism of organic molecules on iron surface in HCl solution through chemisorption and physisorption (Verma et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2023b).

In acidic solution, the introduction of organic compounds can give rise to the formation of a thin protective layer on the metal surface. This phenomenon leads to a noteworthy reduction in the corrosion rate, attributed to a substitution reaction occurring between inhibitor molecules and water molecules at the metal/solution interface. This reaction can be mathematically expressed as shown in Equation (11) (Bensouda et al. 2019).

In the proposed model, Org(sol) and Org(ads) represent inhibitor molecules in solution and on the metal surface, while H2O(sol) and H2O(ads) represent denote water molecules. The size ratio parameter, x, signifies the number of water molecules displaced by one inhibitor molecule, influenced by the inhibitor’s geometry. Planar geometry enhances surface coverage for better corrosion inhibition. The inhibitors lead to the formation of adsorbed intermediates, mitigating Fe anodic dissolution, Equations (12)–(18) (Mathur and Vasudevan 1982; Oakes and West 2013):

In the dissolution of Fe in an acid solution, the reduction of

The corrosion inhibition mechanisms involve physisorption, driven by excessive Fe oxidation in HCl solution, leading to positive charges on the steel surface. Fe+2 attracts Cl− ions, forming inner and outer Helmholtz planes (IHP and OHP). Simultaneously, chemisorption occurs as continued oxidation of surface iron atoms generates electrons, facilitating the reversion of adsorbed cationic inhibitor (Inh-H+) molecules to their neutral form. Heteroatoms with lone pairs contribute to chemisorption, establishing stronger chemical interactions compared to the physical interactions observed in physisorption, Equations (19) and (20) (Bhardwaj et al. 2021; Zhao et al. 2023a).

The electron transfer accumulates electrons in iron d-orbitals, inducing a reverse transfer to the unoccupied antibonding orbitals of inhibitor molecules through retro-donation, driven by interelectronic repulsion. The synergistic reinforcement enhances both processes (Zhu et al. 2017). In an acidic medium, Verma et al. and Zhao et al. demonstrated the interaction of inhibitors with the iron surface via both physisorption and chemisorption mechanisms, as depicted in Figure 2 (Verma et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2023b).

3 Research methods and characterization techniques

3.1 Classification of corrosion inhibitors

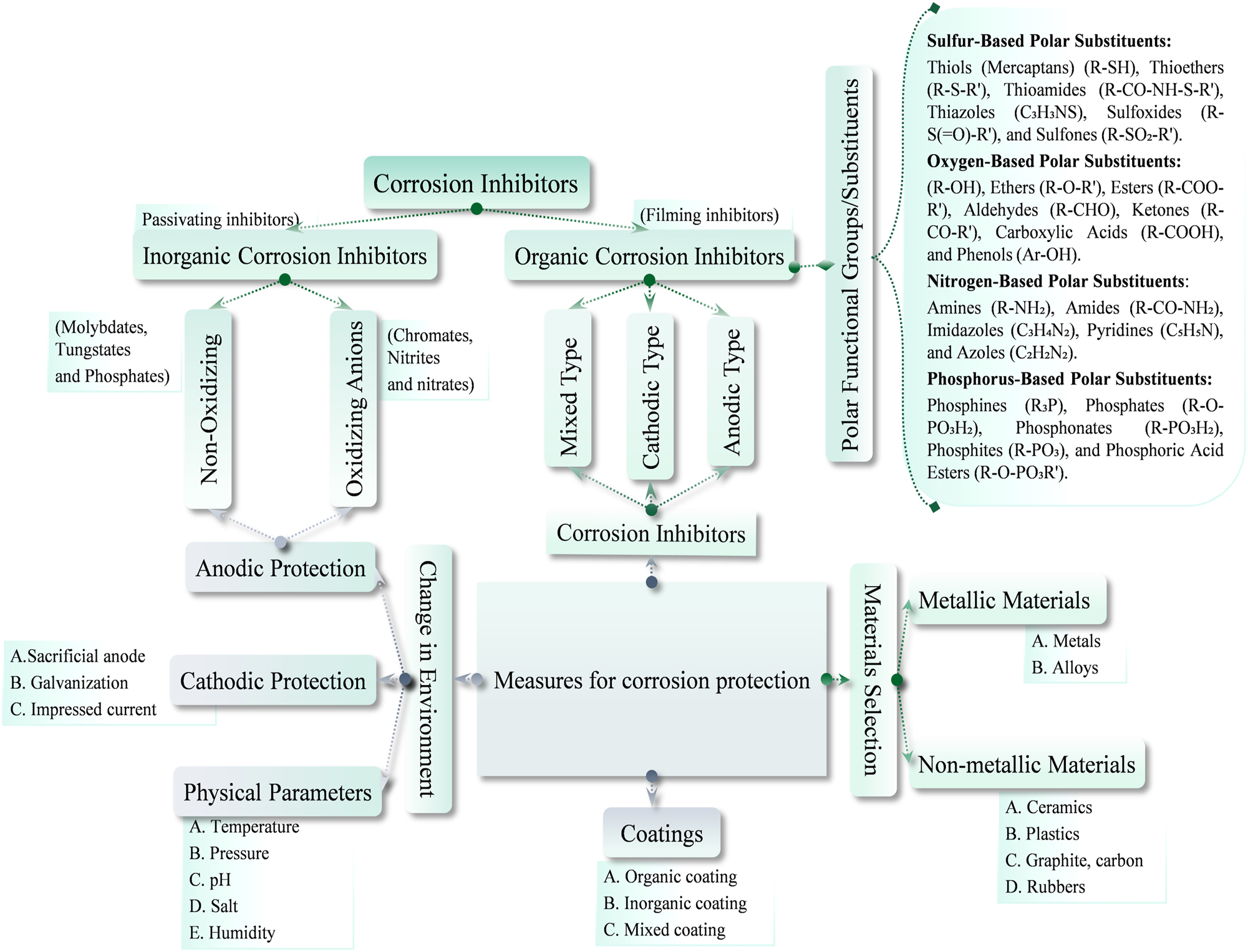

Corrosion inhibitors, categorized by composition, mechanism, and application, encompass organic and inorganic types with anodic, cathodic, or mixed action. From water systems to oil pipelines, these inhibitors vary, with green options and metal-specific choices. Advanced categories include natural and synthetic inhibitors, offering a nuanced approach to corrosion prevention. Selection depends on understanding the corrosion attack, metal, and environment for tailored protection in diverse applications (Abd-El-Nabey et al. 2020; Al-Amiery et al. 2023; Kadhim et al. 2021; Sherif 2014; Verma et al. 2024b). As shown in Figure 3, which classifies corrosion inhibitors and protection methods, various approaches to mitigating corrosion are depicted (Verma et al. 2023).

Classification of corrosion inhibitors and different corrosion protection methods (Verma et al. 2023).

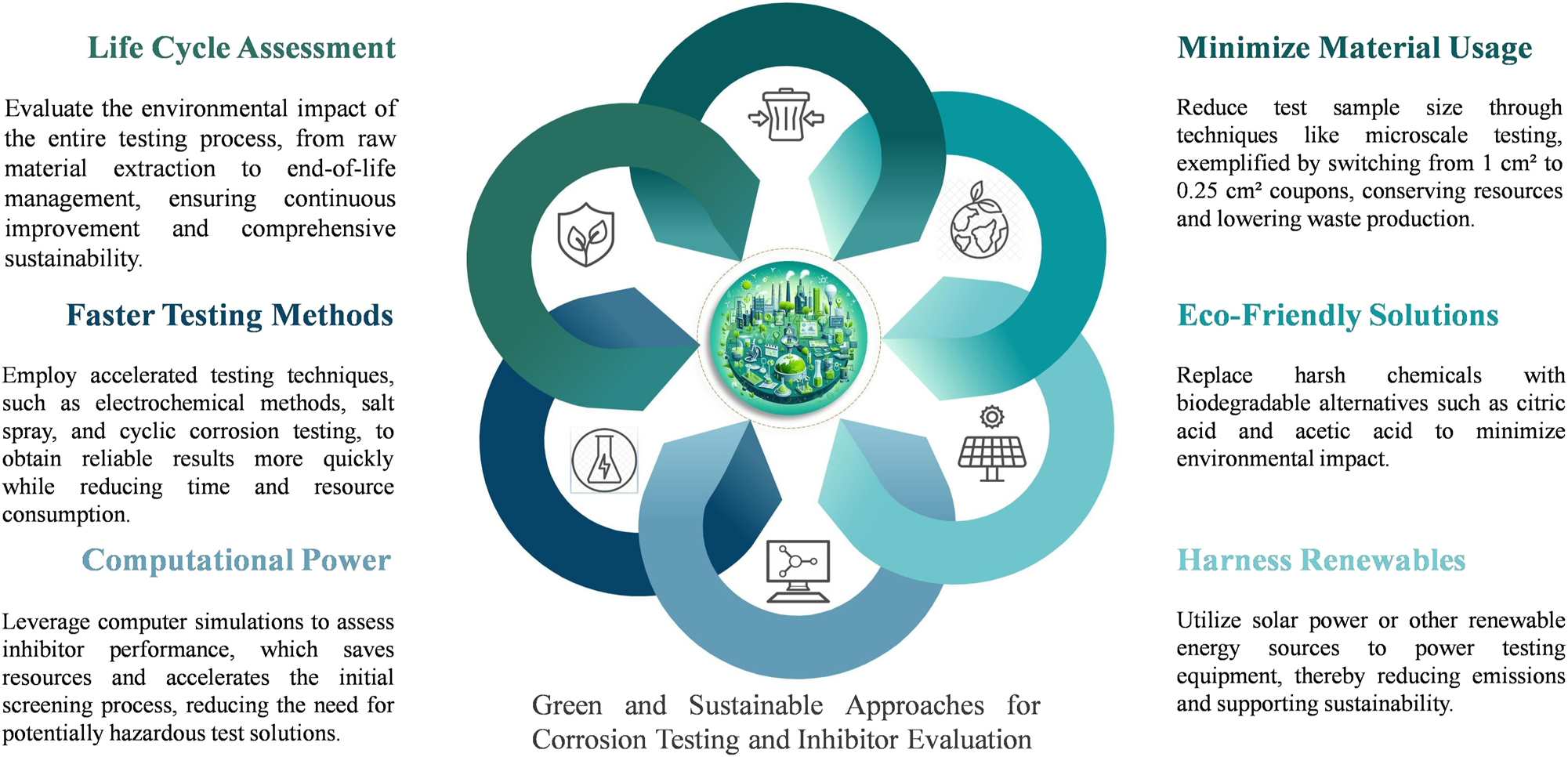

Green principles can be implemented in both corrosion testing and inhibitor evaluation. Figure 4 illustrates some of these approaches. Sustainable testing methods involve using environmentally friendly electrolytes with lower toxicity or readily biodegradable components. Instead of strong acids, consider using milder, environmentally friendly alternatives like citric acid or acetic acid. For instance, citric acid can replace hydrochloric acid in some corrosion tests, thereby reducing environmental and health hazards (Verma et al. 2020). Additionally, minimizing test sample size can significantly lower waste production and material usage. For example, switching from 1 cm2 to 0.25 cm2 coupons can reduce metal consumption by up to 75 %, and millimeter-sized coupons can decrease usage by up to 90 %. In Beake et al.’s research, micro-impact testing techniques, such as micro-computed tomography (µCT), were used to analyze materials with smaller samples. This approach not only enhances efficiency but also aligns with sustainability goals by conserving resources and minimizing costs (Beake et al. 2020). Furthermore, evaluating Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) principles for corrosion inhibitors should include their environmental impact from production to disposal, focusing on raw material extraction, manufacturing processes, usage efficiency, and end-of-life management (Curran 2013). This ensures a comprehensive assessment of their sustainability. Accelerated corrosion tests, such as electrochemical techniques, salt spray, and cyclic corrosion testing, offer rapid results, while slower methods like natural exposure and immersion tests can take months or years (Trzepieciński 2020; Verma et al. 2024b).

Green and sustainable approaches for corrosion testing and inhibitor evaluation.

Using solar power for corrosion testing reduces emissions and supports sustainability. For instance, a lab utilizing solar energy to run corrosion inhibitor tests can significantly minimize its environmental impact (Khan and Arsalan 2016). Green methods for inhibitor evaluation go beyond traditional lab techniques. As this review demonstrates in the experimental and theoretical comparison section, computational predictions using computer simulations to assess inhibitor performance can significantly reduce resource consumption and eliminate the need for potentially hazardous test solutions. This allows for rapid screening of promising green inhibitor candidates before full-scale lab testing (Rafael Martinez et al. 2014; Saha et al. 2023; Sathiyapriya et al. 2021). By combining these green approaches with traditional techniques, researchers can achieve reliable results while minimizing environmental impact and fostering the development of effective and sustainable corrosion control solutions.

3.2 Evaluation methods and experimental parameters

To precisely compare corrosion inhibition efficiency, researchers utilize various evaluation methods across three categories: chemical, electrochemical, and surface analyses. Chemical methods, such as weight loss (WL) and hydrogen evolution (HE), measure corrosion rates based on mass loss and hydrogen gas volume, respectively. Electrochemical techniques, including Open Circuit Potential (OCP), Linear Polarization Resistance (LPR), EIS, PDP, and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), provide insights into corrosion potential, polarization resistance, and electrochemical behavior (Jessima et al. 2020). Surface analyses, using tools like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) (Daoudi et al. 2024), AFM, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) (Verma et al. 2024a), examine surface morphology, elemental composition, and chemical makeup (Ratnani et al. 2024). Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of corrosion processes and inhibitor effectiveness (Chen et al. 2022; Cinitha et al. 2014; Ren et al. 2023; Tan 2011; Xie and Holze 2018; Xu et al. 2020). Detailed information about these methods, including their derived data, advantages, and shortcomings, is collected in Table 1.

Summary of common experimental methods, information derived, advantages, and shortcomings for corrosion inhibition evaluation.

| Experimental class | Measurement technique | Information derived | Advantages | Shortcomings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | WL | Corrosion rate (mass loss) | Simple and direct measurement, cost-effective, versatile | Limited to immersion conditions, time-consuming, does not provide mechanistic insights | Malaret (2022); Usman and Okoro (2015) |

| HE | Corrosion rate (hydrogen gas volume) | Sensitive to corrosion rate, can reveal instantaneous corrosion behavior, suitable for quick assessment | Requires specific experimental setup, may introduce errors during hydrogen collection | Laurent et al. (2017); Song et al. (2016) | |

| Electrochemical | OCP | Corrosion potential | Noninvasive, overall corrosion behavior | Limited to static conditions | Choudhary et al. (2016); Xie and Holze (2018) |

| LPR | Corrosion rate, polarization resistance | Quantitative analysis, nondestructive, rapid assessment | Limited to polarized conditions, requires calibration | Antunes (2023) | |

| EIS | Corrosion rate, polarization resistance, coating integrity | Comprehensive, provides insights into interfaces | Complex data interpretation | Srinivasan and Punathil Meethal (2022) | |

| PDP | Corrosion potential, corrosion rate, polarization resistance | Rapid screening of corrosion behavior, easy measurement, nondestructive | Limited to polarized conditions, limited information about corrosion mechanisms, complex data interpretation | Vaszilcsin et al. (2023) | |

| CV | Electrochemical behavior | Study of redox processes | Complex data interpretation | Elgrishi et al. (2017) | |

| Surface | SEM | Surface morphology, corrosion products | High resolution imaging | Sample preparation required | Raja et al. (2021) |

| EDX | Elemental composition of corrosion products | Elemental analysis | Surface sensitivity | Ech-Chihbi et al. (2020); Rehioui et al. (2024) | |

| AFM | Surface topography, roughness | Nanoscale resolution | Limited imaging area | Dwivedi et al. (2017); Yasakau (2020) | |

| XPS | Chemical composition of surface | Chemical analysis | Surface sensitivity | Baer (1985); Dwivedi et al. (2017) | |

| Optical microscopy | Surface morphology, corrosion features | Low cost, high throughput | Limited resolution | Niu et al. (2009); Song and Xie (2018) |

3.2.1 WL measurements

WL method directly measures the general corrosion rate by assessing the weight loss of a metal sample after exposure to a corrosive environment. While accurate, WL method can be time consuming for rapid inhibitor performance assessment, making it more suitable for evaluating general corrosion rather than localized corrosion. Combining it with electrochemical methods can help address these limitations (Shamnamol et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2020). Equations are often employed in WL process (21)–(23):

where C WL : corrosion rate (WL method), K: constant for the metal, W: mass loss, A: exposed surface area, t: immersion time, ρ: density of the metal, C WL(inh): corrosion rate with inhibitor, IE(%): inhibition efficiency (percentage), and θ: surface coverage degree.

3.2.2 PDP technique

PDP reveals how inhibitors slow corrosion by analyzing shifts in current and potential. Its extracted parameters, like E corr and i corr, not only calculate inhibition efficiency Equations (24) and (25) but also unveil inhibitor type: mixed near blank E corr, anodic/cathodic with larger shifts. PDP’s strength lies in assessing both general and localized corrosion, offering deeper insights than WL methods (Esmailzadeh et al. 2018).

where R p: polarization resistance with inhibitor and R p(inh): polarization resistance without inhibitor.

3.2.3 EIS measurements

EIS is a powerful tool that decodes the intricate language of corrosion inhibition. By analyzing the electrical dialog between metal and solution, it unveils the effectiveness of inhibitors, acting as protective shields against corrosion. Parameters like resistance and capacitance in EIS measurements offer insights into the inhibitor’s thickness, strength, and surface coverage. This information translates directly into inhibition efficiency, with a higher measured resistance indicating a robust protective shield. EIS provides a microscopic perspective on corrosion dynamics, delivering essential intelligence for selecting optimal corrosion inhibitors Equation (26) (Feliu 2020; Mansfeld 1995).

where R t(inh): total resistance with inhibitor and R t : total resistance without inhibitor.

3.2.4 EFM technique

EFM is a nondestructive corrosion measurement technique providing direct values for EFM parameters, including i corr/EFM corrosion current density, Ba Bc Tafel slopes, CF2, and CF3 causality factors. Notably, EFM does this without requiring prior knowledge of Tafel constants. Inhibition efficiency is easily calculated using Equation (27) (Obot and Onyeachu 2018; Sharma et al. 2023):

where i corr/EFM: corrosion current densities without inhibitors and i corr/EFM(inh): corrosion current densities with inhibitors.

3.2.5 Adsorption isotherms and thermodynamic parameters

In the study of corrosion inhibitor studies, adsorption isotherms and thermodynamic parameters play a pivotal role. Researchers leverage adsorption thermodynamics, utilizing models like Langmuir, Temkin, and Redlich–Peterson, to calculate key parameters such as the adsorption equilibrium constant (K ads), adsorption free energy (ΔG ads), enthalpy (ΔH ads), and entropy (ΔS ads). These models provide insights into the metal–inhibitor interaction, distinguishing between physisorption and chemisorption. In the analysis of corrosion inhibitors, thermodynamic parameters like ΔG ads, ΔH ads, and ΔS ads offer crucial information about the spontaneity and nature of the adsorption process. The activation energy (E a ) is calculated using the Arrhenius equation, aiding in understanding inhibitor–metal complex formation. The transition state equation helps determine corrosion rates by considering changes in entropy and enthalpy during the corrosion process (Batool et al. 2018; Ghosal and Gupta 2017; Sharma and Kumar 2021).

4 Theoretical calculations

Theoretical calculations play a crucial role in corrosion inhibition research by providing insights at the atomic and molecular scales. Experimental methods offer average properties, but computational techniques, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT)-based quantum mechanics (QM) calculations and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM), MD, and MC simulations, enable the exploration of inhibitor molecules’ corrosion inhibition mechanisms (Dong et al. 2021; Mamad et al. 2023b; Mamand et al. 2024; Obot et al. 2015). Moreover, integrating Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) models enhances understanding and development of corrosion inhibitors by linking molecular structure to inhibition efficiency, streamlining discovery, and advancing eco-friendly solutions (Khaled et al. 2016; Quadri et al. 2021).

4.1 DFT calculations

DFT serves as an indispensable tool in the study of corrosion inhibition, providing profound insights into the molecular properties and mechanisms at play. The theory’s application in this domain is predicated on the evaluation of both global and local reactivity descriptors, which are pivotal in elucidating the behavior of inhibitors. The Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMO) Theory posits that the reactivity of a molecule can be understood through its (ΨHOMO, ΨLUMO, and energy gap (∆Egap)), between these orbitals is indicative of the molecule’s chemical stability; a smaller gap suggests higher reactivity and vice versa. The E HOMO is directly related to the molecule’s ionization potential (I), reflecting its propensity to donate electrons. Conversely, the E LUMO correlates with the electron affinity (A), denoting the ease with which the molecule accepts electrons (Mecibah et al. 2021; Meften et al. 2018). Electronegativity (χ) is a measure of an atom’s ability to attract shared electrons, while chemical potential (μ) represents the energy change associated with the addition of an electron to a system. Both parameters are integral in assessing the inhibitor’s electron-donating or accepting tendencies. Hardness (η) measures resistance to deformation of the electron cloud, whereas softness (S) indicates the ease of deformation. Soft molecules, which have high polarizability, are generally more reactive and can form stronger interactions with the metal surface. The electrophilicity index (ω) quantifies the tendency of a molecule to accept electrons, with a higher ω value suggesting a greater likelihood of the molecule acting as an electrophile (Abbaz et al. 2019; Akbas et al. 2023b; Hsissou et al. 2020).

The dipole moment (D) is a vector quantity that measures the polarity of a molecule. A higher dipole moment implies a greater asymmetry in the electron distribution, which can enhance the inhibitor’s interaction with the metal surface, thereby improving its efficiency. Atomic Fukui indices (f+, f−) are localized descriptors derived from the change in electron density, indicating the propensity of specific atoms within a molecule to donate (f−) or accept (f+) electrons. They are critical for pinpointing the functional groups involved in adsorption and the formation of a protective film on the metal surface (Hsissou et al. 2020; Seddik et al. 2024).

Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps the electrostatic potential generated by the electron cloud and nuclei of a molecule, offering a visual representation of the charge distribution and predicting the sites of electrophilic and nucleophilic attacks. Electron-donating capacity (ΔN) quantifies the electron-donating ability of an inhibitor, crucial for the formation of a protective film on the metal surface, as it facilitates electron transfer from the inhibitor to the metal. Back-donation, quantified by ΔE backdonation, influences inhibitor efficiency by facilitating electron donation from the inhibitor’s LUMO to the metal’s d-orbitals. This stabilizes the metal–inhibitor complex, enhancing protective film formation, Equations (28)–(35) represent the mathematical expressions for calculating above parameters (Bendjeddoua et al. 2016; Fleming 2010; Mamad et al. 2023a; Parr 1983; Parr et al. 1978, 1999; Pearson 1989).

Also, according Mulliken’s definition of electronegativity.

If two chemical species A and B connected, electrons should move from lower electronegativity substance (i.e., inhibitor) to the higher electronegativity substance (i.e., metal surface unless the two chemicals potentially reach equilibrium), ΔN fraction is measure the electron transferred from low (x) to high (x) on formation of AB (Ahmed et al. 2023; Fleming 2010; Pearson 1989), Equations (36) and (37).

where x m is the electronegativity of electron accepting system (i.e., x Fe = absolute electronegativity of Iron), x inh denote to absolute electronegativity of chemical inhibitor, and η m and η inh represent the global hardness of electron accepting chemical species and the inhibitor molecule, respectively (Akbas et al. 2023a; Tomic et al. 2010). To calculate the value of ∆N, some observable values have been used such as x Fe = 7.0 eV and η Fe = 0 by considering that for a metallic bulk (I = A) (Dewar and Thiel 1977; Sastri and Perumareddi 1997).

4.2 MD and MC simulations

MD and MC simulations are vital for comprehending corrosion inhibitor adsorption at metal–electrolyte interfaces. MD tracks molecular evolution, emphasizing (E bin) for stability. The energy of binding is calculated by Equation (38):

MC simulations, using ab initio force fields, offer a faster alternative, considering van der Waals interactions and temperature. MD employs force fields like Universal and COMPASSII, optimizing potential energy for stable adsorption. Aqueous phase considerations assess metal–water, inhibitor–metal, and inhibitor–water interactions. RDF analysis distinguishes chemisorption and physisorption based on peak positions. Prominent peaks at 1–3.5 Å indicate chemisorption, while peaks beyond 3.5 Å suggest physisorption. The interaction strength is gauged by the difference between the inhibitor and Fe2+ ion (Haris et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2023; Verma et al. 2018a; Zheng et al. 2019).

4.3 ANN and QSAR analysis

QSAR models use statistical methods such as regression analysis to predict the efficacy of nonsynthesized compounds as anticorrosion agents. Molecular descriptors representing structural and chemical properties are utilized in equations to correlate these characteristics with inhibition performance. Linear and nonlinear equations, such as the Lukovits–Kálmán–Pálinkás (LKP) model and Langmuir adsorption isotherm-based Equations (39) and (40), are employed (Lukovits et al. 1998, 1997). These models are evaluated using parameters like R 2 to assess predictive accuracy. For example, Kabanda et al. investigated quinoxaline compounds’ inhibitive properties against copper corrosion using both linear and nonlinear QSAR Equations (41) and (42) (Kabanda and Ebenso 2012), achieving strong correlations between chemical reactivity variables and inhibition efficiencies (R 2 values of 0.991 and 0.998).

Furthermore, ANN models, like the radial basis function neural network (RBFNN) and others, predict corrosion behaviors by learning from data on molecular descriptors and inhibition efficiencies. For example, Komijani et al. achieved a high accuracy with an RBFNN in simulating electrochemical impedance plots (Komijani et al. 2016), while Khaled and Al-Mobarak used ANN to predict inhibition efficiencies of thiophene derivatives, showing strong correlations with molecular descriptors (Khaled and Abdel-Shafi 2014; Khaled and Al-Mobarak 2012).

In QSAR modeling, IEcal(%) is the theoretical inhibition efficiency. Constants A and B are obtained from regression analysis. x i represents a quantum chemical descriptor (e.g., (E HOMO, η, ΔE, etc.) characteristic of the molecule i; C i is the inhibitor concentration.

Linear model:

with R 2 = 0.991, SSE = 4.179 and RMSE = 2.044.

Nonlinear model:

with R 2 = 0.998, SSE = 0.766 and RMSE = 0.875.

5 Experimental and theoretical comparison

In this review, we assess the experimental EI% derived from diverse methods applied to iron-containing materials. A comparative analysis is conducted, taking into account computational data, including (ΔN) and (E bin). The literature is referenced to gather information under closely controlled conditions for a thorough examination, the data summarized in Table 2.

Experimental and theoretical data.

| Abbr. | Molecular structure | Experimental | Theoretical | References | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface | Medium HCl (M) | Inh. conc. (mM) | Method | Max. IE (%) | E LUMO (eV) | E HOMO (eV) | ΔN | E bin Fe (110):Inh (Kcal/mol) | |||

| 2A | 2-Indolecarboxaldehyde semicarbazone | CS | 1.0 | 10.0 | EIS | 86 | −0.277 | −8.265 | 0.342 | Goulart et al. (2013) | |

| 1A | 4-Ethoxybenzaldehyde thiosemicarbazone | CS | 1.0 | 10.0 | EIS | 93 | −0.419 | −8.400 | 0.325 | Goulart et al. (2013) | |

| 1B | 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde thiosemicarbazone | CS | 1.0 | 10.0 | EIS | 90 | −0.471 | −8.441 | 0.319 | Goulart et al. (2013) | |

| 1C | 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde thiosemicarbazone | CS | 1.0 | 10.0 | EIS | 93 | −0.505 | −8.452 | 0.317 | Goulart et al. (2013) | |

| 1D | 2-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone | CS | 1.0 | 10.0 | EIS | 86 | −0.625 | −8.525 | 0.307 | Goulart et al. (2013) | |

| 2B | 2-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde semi carbazone | CS | 1.0 | 10.0 | EIS | 76 | −0.408 | −9.208 | 0.249 | Goulart et al. (2013) | |

| 2-PCT | 2-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone | MS | 1.0 | 1.5 | EIS | 89.7 | −2.560 | −4.660 | 1.614 | 83.52 | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 4-PCT | 4-Pyridinecarboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone | MS | 1.0 | 1.5 | EIS | 85.5 | −2.780 | −4.810 | 1.579 | 83.39 | Xu et al. (2014) |

| Tr1 | Hexahydro-1,3,5-triphenyl-s-triazine | MS | 1.0 | 8.5 | EIS | 94.09 | −0.487 | −5.392 | 0.828 | 5.11 | Obot et al. (2016); Sudhish and Quraishi (2012) |

| Tr2 | Hexahydro-1,3,5-p-tolyl-s-triazine | MS | 1.0 | 8.5 | EIS | 94.28 | −0.385 | −5.182 | 0.879 | 5.11 | Obot et al. (2016); Sudhish and Quraishi (2012) |

| Tr3 | Hexahydro-1,3,5-p-methoxyphenyl-s-triazine | MS | 1.0 | 8.5 | EIS | 95.51 | −0.443 | −5.033 | 0.929 | 5.42 | Obot et al. (2016); Sudhish and Quraishi (2012) |

| Tr4 | Hexahydro-1,3,5-p-aminophenyl-striazine | MS | 1.0 | 8.5 | EIS | 96.14 | −0.300 | −4.698 | 1.024 | 5.85 | Obot et al. (2016); Sudhish and Quraishi (2012) |

| Tr5 | Hexahydro-1,3,5-p-nitrophenyl-s-triazine | MS | 1.0 | 8.5 | EIS | 86.56 | −0.348 | −5.892 | 0.700 | 4.66 | Obot et al. (2016); Sudhish and Quraishi (2012) |

| BMTC | 4-(4-Bromophenyl)-N-(4-methoxybenzylidene)thiazole-2-carbohydrazide | MS | 0.5 | 1.1 | EIS | 86.68 | −2.208 | −6.045 | 0.749 | 196.20 | Kumar and Mohana (2014); Obot et al. (2016) |

| BDTC | 4-(4-Bromophenyl)-N-(2,4-dimethoxybenzylidene)thiazole-2-carbohydrazide | MS | 0.5 | 1.1 | EIS | 90.63 | −2.103 | −5.796 | 0.826 | 220.19 | Kumar and Mohana (2014); Obot et al. (2016) |

| BHTC | 4-(4-Bromophenyl)-N-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)thiazole-2-carbohydrazide | MS | 0.5 | 1.1 | EIS | 84.81 | −2.221 | −6.378 | 0.650 | 184.89 | Kumar and Mohana (2014), Obot et al. (2016) |

| PMHQ | 5-Propoxymethyl-8-hydroxyquinoline | CS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 97.2 | −1.444 | −5.541 | 0.856 | 549.90 | El Faydy et al. (2018) |

| MMHQ | 5-Methoxymethyl-8-hydroxyquinoline | CS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 94 | −1.477 | −5.587 | 0.844 | 472.49 | El Faydy et al. (2018) |

| HMHQ | 5-Hydroxymethyl-8-hydroxyquinoline | CS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 90.8 | −1.549 | −5.666 | 0.824 | 439.54 | El Faydy et al. (2018) |

| S1 | 5-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(piperidin-1-yl) pent-2-en-1-one | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | PDP | 97.5 | −0.670 | −5.267 | 0.877 | 122.65 | Belghiti et al. (2018); El-Hajjaji et al. (2018) |

| S2 | 5-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-(piperidin-1-yl) penta-2,4-dien-1-one | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | PDP | 98.9 | −1.268 | −5.270 | 0.932 | 140.17 | Belghiti et al. (2018); El-Hajjaji et al. (2018) |

| S3 | 5-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl) penta-2,4-dienoic acid | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | PDP | 90.4 | −2.122 | −5.714 | 0.858 | 107.20 | Belghiti et al. (2018); El-Hajjaji et al. (2018) |

| [Chl][Cl] | 2-Hydroxyethyl-trimethylammonium chloride | MS | 1.0 | 2.0 | WL | 92.04 | 2.106 | 0.257 | 4.424 | 2.52 | Verma et al. (2018b) |

| [Chl][l] | 2-Hydroxyethyl-trimethyl-ammonium iodide | MS | 1.0 | 2.0 | WL | 96.02 | 2.390 | 0.718 | 5.117 | 2.55 | Verma et al. (2018b) |

| [Chl][Ac] | 2-Hydroxyethyl-trimethyl-ammonium acetate | MS | 1.0 | 2.0 | WL | 96.59 | 1.028 | −0.604 | 4.420 | 2.92 | Verma et al. (2018b) |

| DPPN | 6-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-4-phenyl-2-(phenylamino)nicotinonitrile | MS | 1.0 | 2.0 | EIS | 95.81 | −1.970 | −5.836 | 0.801 | 210.74 | Verma et al. (2018d) |

| DHPN | 6-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-((4-hydroxyphenyl)amino)-4-phenylnicotinonitrile | MS | 1.0 | 2.0 | EIS | 96.24 | −1.970 | −5.813 | 0.809 | 221.40 | Verma et al. (2018d) |

| DMPN | 6-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-((4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-4-phenylnicotinonitrile | MS | 1.0 | 2.0 | EIS | 96.63 | −1.890 | −5.789 | 0.811 | 230.49 | Verma et al. (2018d) |

| Bz | N-(2-((Z)-2-(Benzylideneamino)ethylamino)ethyl)-3,4,5-trihydroxybenzamide | MS | 0.5 | 7.0 | EIS | 85.42 | −1.609 | −4.774 | 1.203 | 120.72 | El Basiony et al. (2019) |

| VA | N-(2-((Z)-2-(3-Methoxy-4-hydroxybenzylideneamino)ethylamino)ethyl)-3,4,5 trihydroxybenzamide | MS | 0.5 | 7.0 | EIS | 88.52 | −1.719 | −4.692 | 1.276 | 142.71 | El Basiony et al. (2019) |

| ER1 | 2,2′-(((Sulfonylbis(4,1-phenylene)) bis (oxy))bis(methylene))bis(oxirane) | CS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 97.6 | −1.379 | −6.573 | 0.582 | 6.04 | Dagdag et al. (2019) |

| ER2 | 2,2′-Bis(oxiran-2-ylmethoxy)-1,1′-biphenyl | CS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 95.6 | −0.722 | −5.867 | 0.720 | 4.66 | Dagdag et al. (2019) |

| BMQ | 5-((Benzyloxy)methyl)quinolin-8-ol | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 94.2 | −3.108 | −6.523 | 0.640 | 4,023 | Galai et al. (2020) |

| DEMQ | 5-((2-(Diethylamino)ethoxy)methyl)quinolin-8-ol | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 93.7 | −3.193 | −7.030 | 0.492 | 4,018 | Galai et al. (2020) |

| C1 | Benzoic acid | MS | 0.5 | 10.0 | EIS | 72.1 | 71.36 | Alahiane et al. (2020) | |||

| C2 | Para-hydroxybenzoic acid | MS | 0.5 | 10.0 | EIS | 84.2 | 75.99 | Alahiane et al. (2020) | |||

| C3 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | MS | 0.5 | 10.0 | EIS | 87.6 | 79.42 | Alahiane et al. (2020) | |||

| CTDP | 2-(5-(4-Cyanophenyl)-2,4,6,8-tetraoxo1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9 – octahydropyrido [2,3-d:6,5-d’]dipyrimidin-10 (5 H)-yl)-3-(1H-imidazol-4-yl) propanoic acid | MS | 15 % | 2.0 | EIS | 92.9 | −1.630 | −6.410 | 0.623 | 231.78 | Saraswat et al. (2020) |

| OPDB | 4-(2,4,6,8-Tetraoxo-2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9-octahydro-1H-pyrano[2,3-d:6,5-d’]dipyrimidin-5-yl)benzonitrile | MS | 15 % | 2.0 | EIS | 89.1 | −1.720 | −6.680 | 0.565 | 205.11 | Saraswat et al. (2020) |

| P1 | Phenylalanine | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 86.8 | −0.461 | −6.940 | 0.509 | 105.1 | Oubaaqa et al. (2021) |

| P2 | Aspartic acid | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 88.7 | −0.314 | −7.060 | 0.491 | 130.5 | Oubaaqa et al. (2021) |

| l-alanine | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | PDP | 40.29 | 0.494 | −9.011 | 0.288 | 449 | Adamma et al. (2010); Ashassi-Sorkhabi et al. (2004); Mamad et al. (2023a) | |

| Glycine | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | PDP | −4.47 | 0.472 | −8.939 | 0.294 | 92.62 | Adamma et al. (2010); Ashassi-Sorkhabi et al. (2004); Mamad et al. (2023a) | |

| Leucine | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | PDP | 70.67 | 0.488 | −9.179 | 0.275 | Adamma et al. (2010); Ashassi-Sorkhabi et al. (2004); Mamad et al. (2023a) | ||

| Aspirin | MS | 1.0 | 8.0 | EIS | 79.2 | −2.060 | −7.330 | 0.437 | 119 | Ikeuba et al. (2022) | |

| TODB | 4-((4-Hydroxy-3-((4-oxo-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)phenyl) diazinyl) benzenesulfonic acid | MS | 1.0 | 0.75 | EIS | 93.90 | −3.576 | −6.704 | 0.595 | 3,648 | Bedair et al. (2023) |

| DODB | 4-((3-((4,4-Dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohexylidene) methyl)-4-hydroxyphenyl)diazinyl) benzenesulfonic acid | MS | 1.0 | 0.75 | EIS | 92.05 | 3.381 | −6.855 | 0.514 | 3,025 | Bedair et al. (2023) |

| NAP | Naproxen | CS | 1.0 | 8.0 | WL | 94.96 | −1.760 | −5.872 | 0.774 | 1,444 | Shams et al. (2023) |

| BPUA | 1,1-((Methylazanediyl)bis(propane-3,1-diyl))bis(3-(p-tolyl)urea) | CS | 1.0 | 1.5 | EIS | 95.1 | 0.715 | −7.293 | 0.463 | Shkoor et al. (2023) | |

| CMBTAP | 4-Chloro-2-(4-methyl-benzothiazol-2-ylazo)-phenol | CS | 1.0 | 0.1 | EIS | 50.6 | −3.042 | −5.083 | 1.44 | 212.72 | Rasul et al. (2023) |

| CBAMP | 2-(6-Chloro-benzothiazol-2-ylazo)-4-methyl-phenol | CS | 1.0 | 0.1 | EIS | 47.13 | −2.973 | −5.367 | 1.18 | 113.76 | Rasul et al. (2023) |

| CBAN | 1-(6-Chloro-benzothiazol-2-ylazo)-naphthalen-2-ol | CS | 1.0 | 0.1 | EIS | 41.6 | −3.368 | −5.776 | 1.01 | 90.20 | Rasul et al. (2023) |

| TZ1 | (Z)-3-(1-(2-(4-Amino-5-mercapto-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)hydrazono)ethyl)-2H-chromen-2-one | CS | 1.0 | 0.1 | EIS | 85.8 | −2.610 | −4.630 | 1.673 | 194.09 | Belal et al. (2023) |

| TZ2 | 5-(2-(9H-Fuoren-9-ylidene)hydrazineyl)-4-amino-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol | CS | 1.0 | 0.1 | EIS | 72.4 | −2.420 | −4.650 | 1.554 | 187.14 | Belal et al. (2023) |

| TTA | 6-Chloro-2-methoxy-9-(4-(((tetrahydrofuran-3-il)oxy)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-il)acridine | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 85.3 | 11.30 | Machado Fernandes et al. (2024) | |||

| ATM | (1-(6-Chloro-2-methoxyacridin-9-il)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-il)methanol | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 89.4 | 58.34 | Machado Fernandes et al. (2024) | |||

| ATA | (1-(6-Chloro-2-methoxyacridin-9-il)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-il)methyl acetate | MS | 1.0 | 1.0 | EIS | 94.1 | 63.88 | Machado Fernandes et al. (2024) | |||

| DMAPAAP | 2-Dimethylaminopropionamidoanti-pyrine | MS | 1.0 | 0.5 | WL | 91.8 | 0.760 | −7.556 | 0.433 | Abbass et al. (2024) | |

Goulart et al. investigated corrosion inhibition properties of synthesized thiosemicarbazones and semicarbazones (1A, 1B, 1C, 1D, 2A, and 2B) on CS in 1 M HCl, finding increased efficiency with higher concentrations. Thiosemicarbazones showed superior performance over semicarbazones, highlighting the impact of substituting the carbonyl group with the thiocarbonyl group. Adsorption behavior, analyzed using the Langmuir model, indicated strong interactions with the CS surface. The study employed PDP, EIS, and molecular modeling, offering insights for corrosion control applications. While correlations exist between %IE and theoretical parameters such as E LUMO, E HOMO, and ΔN, the relationship is not always linear. Generally, compounds with lower E LUMO or higher E HOMO values exhibit higher %IE, suggesting better electron donation or acceptance. Similarly, higher ΔN values correlate with stronger charge transfer and higher %IE. The order of molecules for each parameter is as follows (Table 2): for Max. IE (%): 1C ≈ 1A > 1B > 1D ≈ 2A > 2B, E LUMO (eV): 1D < 1C < 1B < 1A < 2B < 2A, E HOMO (eV): 2A < 1A < 1B < 1C < 1D < 2B; for ΔN: 2A > 1A > 1B > 1C > 1D > 2B (Goulart et al. 2013).

Xu et al. identified 2-PCT and 4-PCT as potent Schiff’s base compounds inhibiting MS corrosion in 1 M HCl, with increasing efficiency observed at higher concentrations. Both compounds act as mixed-type inhibitors, effectively hindering both anodic metal dissolution and cathodic hydrogen evolution, with their adsorption behavior governed by the Langmuir isotherm. Through a combination of electrochemical measurements (EIS) and theoretical calculations, the study consistently establishes 2-PCT’s superiority over 4-PCT in terms of inhibition (Table 2). This superiority is further emphasized by the higher E bin value of 83.52 kcal/mol for 2-PCT compared to 83.39 kcal/mol for 4-PCT. Additionally, 2-PCT exhibits a higher IE% of 89.7 % compared to 85.5 % for 4-PCT. Furthermore, the calculated ΔN is notably larger for 2-PCT at 1.614 compared to 1.579 for 4-PCT (Xu et al. 2014).

Shukla et al. provided experimental data, while Obot et al. conducted theoretical investigations using DFT calculations and MC simulations, focusing on the corrosion inhibition properties of triazine derivatives (Tr1 to Tr5) on steel surfaces. Theoretical evaluations demonstrated a correlation between calculated parameters and experimental inhibition efficiencies, ranking Tr4 > Tr3 > Tr2 > Tr1 > Tr5 in inhibition capabilities for Max. IE (%), ΔN, and E bin. Theoretical results aligned well with experimental outcomes, showcasing Tr4 as the standout inhibitor with the highest values for Max. IE (96.14 %), ΔN (1.024), and E bin Fe (110):Inh (5.85 kcal/mol). These findings underscore Tr4’s exceptional corrosion inhibition capabilities, positioning it as a promising candidate for corrosion control strategies (Obot et al. 2016; Sudhish and Quraishi 2012).

Obot et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition properties of Schiff bases (BMTC, BDTC, and BHTC) using DFT and MC simulations in acidic conditions. The study established a fair correlation between electronic parameters and experimentally determined inhibition efficiencies, ranking BDTC > BMTC > BHTC in corrosion inhibition. The B3LYP method with a 6-31 ++ G basis set aligned well with experimental data. Adsorption energies indicated a spontaneous process, and MC simulations revealed a parallel adsorption orientation on the iron surface in the order BDTC > BMTC > BHTC (Table 2), offering insights for designing effective Schiff base corrosion inhibitors (Kumar and Mohana 2014; Obot et al. 2016).

Faydy et al. synthesized three new organic compounds based on 8-hydroxyquinoline and evaluated their corrosion inhibition properties on CS in 1 M HCl solution. The synthesized compounds, namely PMHQ, MMHQ, and HMHQ, exhibited mixed-type corrosion inhibition with PMHQ showing the highest protection efficiency of 94 % at an optimum concentration of 10−3 M. Electrochemical and WL measurements, along with theoretical calculations using DFT and MC simulations, supported the inhibitory actions of these compounds. The order of effectiveness based on Max. IE (%), E bin, and ΔN is PMHQ > MMHQ > HMHQ (Table 2). Adsorption studies indicated Langmuir adsorption isotherm behavior, and surface analyses confirmed the formation of a protective film on the CS surface. The inhibitory efficiency increased with the length of the alkyl substituent at the 5-position of 8-hydroxyquinoline (El Faydy et al. 2018).

Belghiti et al. employed DFT methods to investigate the interaction between three piperine derivatives (S1, S2, and S3) and iron. Their study revealed preferred complexes with Fe atoms in a mono-dentate binding mode and calculated interaction energies that correlated with observed trends in corrosion inhibition efficiency. Quantum chemical and MD simulations provided insights into the active sites and stable configurations on Fe surfaces. Additionally, MC simulations were consistent with experimental data, indicating the order of effectiveness based on maximum IE%, E bin, and ΔN is S2 > S1 > S3 (Table 2) (Belghiti et al. 2018; El-Hajjaji et al. 2018).

Verma et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition properties of choline-based ionic liquids ([Chl][Cl], [Chl][I], and [Chl][Ac]) on MS in 1 M HCl. Experimental results showed increased inhibition efficiencies with higher concentrations, and [Chl][Ac] exhibited the highest efficiency (96.59 %) at 17.91 E−4 M. Electrochemical analyses supported their role as interfacial and mixed-type corrosion inhibitors; Nyquist plots and the equivalent circuit for EIS data on the left side of Figure 5 provide insights into corrosion resistance and the effectiveness of inhibitors. Adsorption studies, SEM-EDX, and AFM confirmed adsorption on the metallic surface; the AFM images on the right in Figure 5 show the surface morphology. DFT and MC simulations revealed donor–acceptor interactions, and the computational and experimental results partly aligned, with IE% and E bin following the order: [Chl][Cl] < [Chl][I] < [Chl][Ac]. Conversely, ΔN values followed the order: [Chl][Ac] < [Chl][Cl] < [Chl][I], as indicated in (Table 2). The ionic liquids proved to be effective and environmentally friendly corrosion inhibitors for MS in acidic conditions (Verma et al. 2018b).

![Figure 5:

(Right side) Nyquist plots (a–c) for mild steel in 1 M HCl with and without [Chl][Cl], [Chl][I], and [Chl][Ac], and the equivalent circuit (d) used for EIS data analysis. (Left side) AFM images of mild steel in 1 M HCl: (a) without inhibitors, (b) with [Chl][Cl], (c) with [Chl][I], and (d) with [Chl][Ac] (Verma et al. 2018b).](/document/doi/10.1515/corrrev-2024-0039/asset/graphic/j_corrrev-2024-0039_fig_005.jpg)

(Right side) Nyquist plots (a–c) for mild steel in 1 M HCl with and without [Chl][Cl], [Chl][I], and [Chl][Ac], and the equivalent circuit (d) used for EIS data analysis. (Left side) AFM images of mild steel in 1 M HCl: (a) without inhibitors, (b) with [Chl][Cl], (c) with [Chl][I], and (d) with [Chl][Ac] (Verma et al. 2018b).

Verma et al. explored the inhibitive effects of three N-substituted 2-aminopyridine derivatives (DPPN, DHPN, and DMPN) on MS corrosion in 1 M HCl. Experimental and theoretical analyses showed increased protection efficiencies with higher concentrations. The inhibitors acted as mixed-type with predominant cathodic inhibition, forming protective films on the surface. The order of IE% was DMPN > DHPN > DPPN. Theoretical studies, specifically E bin and ΔN values, followed the same order as the experimental IE%, as shown in (Table 2) (Verma et al. 2018d).

El Basiony et al. synthesized Schiff bases, VA and Bz, from substituted gallic acid, testing their corrosion inhibition on MS in 0.5 M HCl at 298 K. Findings revealed significant reduction in MS dissolution through Langmuir adsorption. Tafel and EIS tests showed mixed-type inhibition, improving with higher Schiff base concentrations. Peak inhibition efficiency of 90 % occurred at 250 ppm. MC simulations and SEM/EDX confirmed adsorption and film formation. VA outperformed Bz, with corrosion inhibition efficiencies of 85.42 % and 88.52 %, respectively, at optimum concentrations, with consistent E bin and ΔN values (Table 2) (El Basiony et al. 2019).

Dagdag et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition properties of two epoxy resins, ER1 and ER2, on CS in 1 M HCl using experimental and computational methods. The study found that the inhibition efficiency of ERs increased with concentration, reaching high values of 98.1 % for ER1 and 95.6 % for ER2 at E−3 M. Adsorption of ERs on the CS surface followed the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, and SEM analysis showed the formation of protective films. The experimental findings were corroborated by computational analyses, incorporating DFT and MC simulations, which offered understanding into the adsorption characteristics and arrangement of ER1 and ER2 on the metal surface. The outcomes were somewhat consistent, with ER1 exhibiting higher IE% and E bin compared to ER2. Conversely, the trend for ΔN values was reversed, with ER1 having lower values than ER2, as illustrated in Table 2 (Dagdag et al. 2019).

Galai et al. developed a method to synthesize 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives with high yields. They studied the corrosion inhibition properties of BMQ and DEMQ on MS in 1 M HCl solution using various electrochemical techniques and surface analysis methods. Both compounds displayed strong resistance, with BMQ achieving an impressive 94 % inhibition efficiency at a concentration of 10−3 M. Acting as mixed-type inhibitors, they adhered to the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, forming a protective layer on the steel surface. Theoretical findings corroborated experimental results, highlighting BMQ’s superior effectiveness over DEMQ based on maximum IE%, E bin, and ΔN values, as seen in Table 2 (Galai et al. 2020).

Alahiane et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition efficiency of benzoic acid (C1, C2, and C3) on AISI 316 stainless steel in 0.5 M HCl at 291 K. Experimental methods, including WL, OCP, PDP, EIS, and SEM, were employed. The results consistently showed that C3 had the highest inhibition efficiency, increasing with higher concentrations, and followed the Villamil adsorption isotherm. Theoretical calculations using DFT and MC simulations supported the experimental findings, ranking inhibition capabilities as C3 > C2 > C1 (Alahiane et al. 2020).

Saraswat et al. synthesized two eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors, CTDP and OPDB, effective at low concentrations for MS in 15 % HCl solution. Both inhibitors showed significant efficiency, even at 10 ppm, with increased effectiveness at higher concentrations and decreased efficiency at higher temperatures. They acted as mixed-type inhibitors, following the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. SEM and AFM studies confirmed protective films on the MS surface. Theoretical calculations using DFT and MC simulations closely matched experimental results, indicating CTDP’s greater efficacy over OPDB. This correlation was evident across all parameters, which were found to be directly proportional, as demonstrated by maximum IE%, E bin, and ΔN values, as depicted in Table 2 (Saraswat et al. 2020).

Oubaaqa et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition properties of P1 and P2 on MS in 1 M HCl solution between 298 and 398 K. They used techniques like EIS, PDP, DFT, MCS, and MDS, alongside UV–vis spectrometry and SEM. Both compounds showed increased inhibition efficiency with concentration, reaching 87 % for P1 and 89 % for P2. Their adsorption mechanism followed the Langmuir isotherm, and they acted as mixed inhibitors. UV–visible analysis indicated decreased ferric ion dissolution, and SEM images confirmed effective adsorption on the MS surface. Computational analyses revealed insights into the metal–inhibitor interaction. Overall, both compounds were effective inhibitors, with P2 showing higher efficiency than P1. P2 exhibited higher IE% and E bin, while the trend for ΔN values was approximately equal, as shown in Table 2 (Oubaaqa et al. 2021).

Ashassi et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition properties of alanine, glycine, and leucine amino acids on steel in different concentrations of HCl solutions at 25 °C using PDP. Their study found that the inhibitors exhibited inhibition efficiencies ranging from 28 % to 91 %, with leucine showing the highest effectiveness, followed by alanine and then glycine. Increasing inhibitor concentration reduced corrosion rates and increased corrosion resistance. Additionally, Adamma and Mamad conducted a theoretical study using DFT methods to predict the reactivity of these amino acids toward electrophilic and nucleophilic attacks with iron. The results suggested that leucine had the highest E bin value, followed by alanine and then glycine (Adamma et al. 2010; Ashassi-Sorkhabi et al. 2004; Mamad et al. 2023a).

Ikeuba et al. discovered that aspirin efficiently inhibits MS corrosion in acid solution, with increased effectiveness at higher concentrations, peaking at 800 mg/L and 333 K. Aspirin’s inhibition involves physical adsorption, raising corrosion activation energy. Kinetics shows first-order reaction at lower temperatures and second-order at higher temperatures. Thermodynamically, the process is endothermic and spontaneous with aspirin. DFT and quantum chemical calculations confirm strong interaction with the steel surface. Aspirin is proposed as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor (Ikeuba et al. 2022).

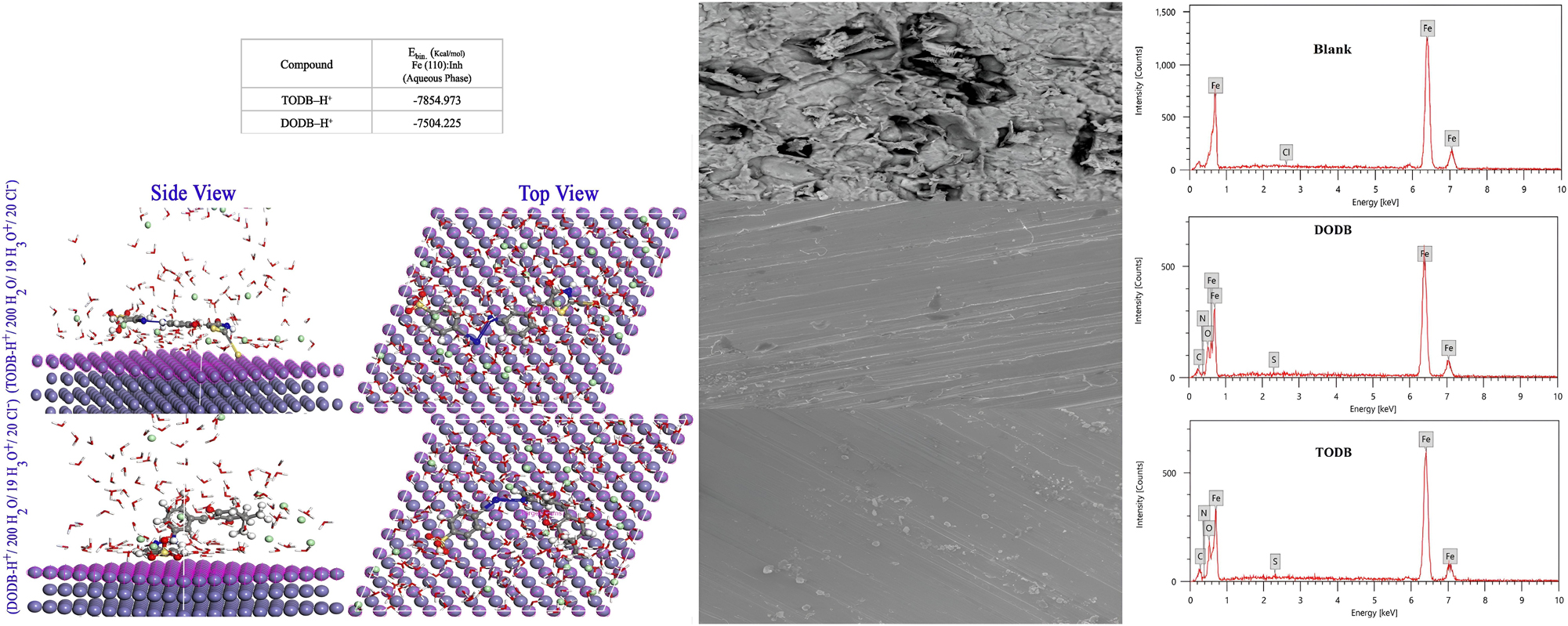

Mahmoud et al. synthesized and characterized two azo derivatives, TODB and DODB, using FTIR, 1H NMR, and mass spectrometry. These compounds were tested as corrosion inhibitors for MS in 1 M HCl through gravimetric methods, PDP, EIS, EFM, and inductive coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy at 30 °C. The Tafel and EIS data showed that TODB and DODB act as mixed-type inhibitors, with the highest IE% of 93.9 % and 92.5 % at 7.5 E−4 M concentration, respectively. Adsorption followed the Langmuir isotherm, and increasing both temperature and inhibitor concentration improved inhibition efficiency. UV–vis, SEM, and EDX analyses confirmed the formation of a protective film on the MS surface, as shown by the magnified SEM images on the right side of Figure 6. Quantum chemical parameters and ICPE measurements corroborate these findings. The left side of Figure 6 visualizes through Monte Carlo simulations how TODB and DODB molecules adsorb on the MS surface, preventing corrosion. The order of effectiveness based on maximum IE%, E bin, and ΔN is TODB > DODB, as shown in Table 2 (Bedair et al. 2023).

SEM images and EDX spectra of the MS surface after 24-h immersion in 1.0 M HCl at 25 °C, showing the effects of synthesized inhibitors TODB and DODB. Additionally, Monte Carlo simulations illustrate the most favorable adsorption modes (Bedair et al. 2023).

Shams et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition effectiveness of NAP (C14H14O3) on carbon steel (CS) in an HCl solution, employing practical and theoretical analyses. The study revealed that increasing the inhibitor concentration enhances its efficiency, reaching a peak of 94.96 % under specific conditions. NAP presence noticeably reduces the weight loss rate, indicating a significant slowdown in the corrosion process. Adsorption of NAP on CS follows the Langmuir isotherm, and observational studies confirm the formation of a protective layer. Theoretical analyses, including MESP contour plots, demonstrate NAP’s electron-donating ability and identify reactive sites for electrophilic and nucleophilic attacks. The adsorption energies of corrosion inhibitors surpass those of water molecules, emphasizing NAP’s robust adsorption on the CS surface (Shams et al. 2023).

Shkoor et al. investigated a novel bis-phenylurea-based aliphatic amine derivative (BPUA) as a green inhibitor for the corrosion of CS in 1 M HCl. The synthesized BPUA demonstrated excellent inhibitory behavior, achieving a corrosion protection efficiency of 95.1 % and significantly increasing charge transfer resistance. The inhibitor reduced the corrosion rate by approximately 19 times across various concentrations. Adsorption isotherm analysis indicated a spontaneous corrosion inhibitory action of BPUA, following Langmuir isotherm. Eco-toxicity assessment and cytotoxicity studies on human epithelial cells MCF-10A supported the environmental-friendliness of BPUA, showing negligible harmful impacts and preserving cell viability. DFT-based quantum chemical calculations aligned with experimental findings, confirming the adsorption of BPUA on CS surface via a flat orientation (Shkoor et al. 2023).

Youssif et al. synthesized three benzothiazole azo dyes (CMBTAP, CBAN, and CBAMP) as corrosion inhibitors for CS in 1 M HCl. The dyes showed increased inhibition efficiency with higher concentrations but reduced effectiveness at elevated temperatures. Synergistic effects with potassium iodide (KI) further enhanced inhibition performance. Acting as mixed-type inhibitors, the dyes formed inhibition films on the CS surface. According to Table 2, there is a linear relationship between experimental and theoretical parameters. The inhibition efficiencies of the dyes, in terms of maximum IE%, E bin, and electron ΔN, are in the order CMBTAP > CBAMP > CBAN. The high inhibition efficiency of CMBTAP is attributed to the large number of adsorption sites on its molecules (Rasul et al. 2023).

Belal et al. introduced two novel derivatives, TZ1 and TZ2, as effective corrosion inhibitors for CS in 1 M HCl, achieving efficiencies of 93.7 % and 84.5 % at 45 °C with optimal concentrations of 9 E−5 M, respectively. According to Table 2, a linear relationship was observed between experimental and theoretical parameters, including IE%, E bin, and ΔN, with TZ1 being more effective than TZ2. Langmuir isotherm analysis indicated spontaneous adsorption, with a mix of physical and chemical adsorption favoring chemisorption at higher temperatures. PDP and EIS data confirmed mixed-type inhibition. Surface analysis using AFM and XPS showed inhibitor linkage to the CS surface, while UV–visible spectroscopy indicated complex formation with ferrous ions. Antibacterial activity and theoretical simulations supported these findings, establishing TZ1 and TZ2 as potent corrosion inhibitors for industrial applications (Belal et al. 2023).

Machado et al. synthesized and evaluated three 1,2,3-triazolyl-acridine derivatives (TTA, ATM, and ATA) as highly effective corrosion inhibitors for MS in acidic media. Gravimetric experiments showed efficiencies up to 94 % at 1 mM and room temperature, improving at higher temperatures. Identified as mixed-type inhibitors, they formed protective films on the metal surface. DFT simulations highlighted covalent bonding with iron atoms, and MD simulations demonstrated prevention of acid corrosion in HCl solution. Based on the findings in Table 2, the trend for IE%, E bin, and ΔN is ATA > ATM > TTA (Machado Fernandes et al. 2024).

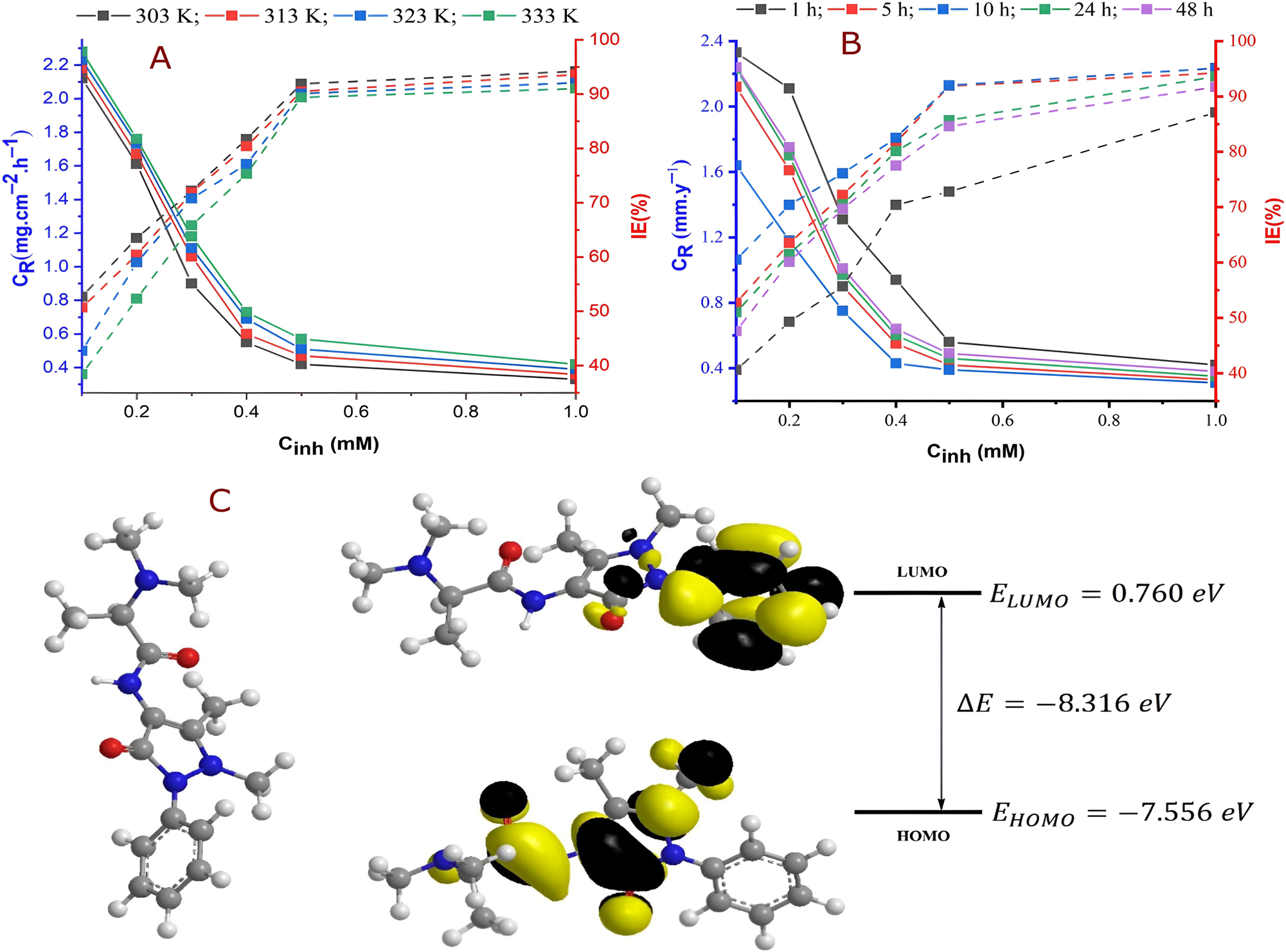

Abbass et al. investigated the corrosion inhibition potential of DMAPAAP on MS in HCl solution through combined experimental and theoretical methods. They found that DMAPAAP effectively inhibited MS corrosion. The corrosion rate increased with rising inhibitor concentration, exposure time, and temperature. Remarkably, the highest inhibition efficiency of 91.9 % was attained with a 5 mM concentration of DMAPAAP after 5 h of exposure at 333 K, as shown in Figure 7a and b. DFT calculations supported experimental results (Figure 7c), revealing chemisorption and physisorption of DMAPAAP on the metal surface, in accordance with the Langmuir adsorption isotherm (Abbass et al. 2024).

Corrosion inhibition performance and molecular insights of DMAPAAP in HCl solutions. (a) Corrosion rate and inhibition efficiency of DMAPAAP in 1 M HCl at 303–333 K over 5 hours. (b) Corrosion and inhibition effectiveness in uninhibited vs. inhibited HCl solutions at 303 K after 5 hours. (c) Optimized structure and molecular orbitals of DMAPAAP (Abbass et al. 2024).

Overall: Table 2 presents data from various studies evaluating the efficiency of organic molecules as corrosion inhibitors on iron surfaces. The inhibitors are tested under nearly standardized conditions, primarily in 1 M HCl solution at 25 °C, using EIS and occasionally other methods like PDP and WL. The IE% varies widely among the inhibitors, with the highest efficiencies including S2 (98.9 %), S1 (97.5 %), and ER1 (97.6 %), generally correlating higher inhibitor concentrations with higher IE%. The E binding parameter is crucial for predicting the interaction strength between the inhibitor and the iron surface, with PMHQ (549.90 kcal/mol) and MMHQ (472.49 kcal/mol) exhibiting significantly high E binding values, indicating strong adsorption. The ΔN parameter reflects the ability of an inhibitor to donate electrons to the metal surface, with higher ΔN values usually correlating with better inhibition efficiency, as seen with S2 (0.932) and S1 (0.877). Molecules with higher E HOMO and lower E LUMO tend to have better inhibition properties, such as Tr3 and Tr4. Many inhibitors follow the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, indicating monolayer adsorption on the metal surface, while the mixed nature of physical and chemical adsorption is noted, with chemisorption becoming more significant at higher temperatures. However, some studies highlight an increase in efficiency at elevated temperatures, possibly due to the favoring of chemisorption, which may not be as effective at lower temperatures, exemplified by inhibitors like TODB, ATA, and TZ1. Examining the corrosion inhibitors listed in the table reveals that many inhibitors demonstrate high efficiency, with inhibition percentages ranging from the mid-80s to mid-90s. Thiosemicarbazone derivatives, hydroxyquinoline, and triazine derivatives consistently exhibit notable inhibition effectiveness, while certain benzothiazole derivatives display moderate to high inhibition efficiency. Variations in performance are influenced by the surface and medium, as different functional groups on inhibitor molecules lead to variations in effectiveness, and compounds with similar chemical structures may exhibit varying efficiencies, highlighting the complexity of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) in corrosion inhibition. The SAR is exemplified by compounds such as 1B (IE%: 90), 1C (IE%: 93), PMHQ (IE%: 97.2), DMPN (IE%: 96.63), and [Chl][Cl] (IE%: 92.04), which possess electron-rich aromatic rings or heterocyclic groups, along with hydroxyl, amino, or methoxy functional groups, often featuring multiple aromatic rings or conjugated systems, enhancing their inhibition efficiencies by facilitating electron donation, promoting adsorption onto metal surfaces, and forming stable complexes with metal ions.

The data consistently demonstrate a direct correlation between experimental IE% and theoretical parameters such as E binding and ΔN, underscoring the potential of using computational methods to predict the efficiency of corrosion inhibitors before experimental validation. However, variations in computational methods and software necessitate careful intra-article comparisons to enhance accuracy, with the integration of experimental and theoretical approaches providing a robust framework for evaluating and understanding the performance of corrosion inhibitors.

6 Conclusions

The review primarily explores the relationship between theoretical parameters, particularly E binding and electron transfer (ΔN), and experimental inhibition efficiency (IE%) in corrosion inhibition studies. The review gathers studies evaluating organic molecules as corrosion inhibitors on iron surfaces under nearly standardized conditions, primarily in 1 M HCl solutions at 25 °C with a 1 mM inhibitor concentration. This standardization enables comparability across studies. EIS has been chosen as the common experimental method to determine IE% among the studies, while theoretical parameters like E binding and ΔN are emphasized. However, due to disparities in computational methods and software across studies, comparing results presents challenges. Therefore, the review emphasizes intra-article comparisons to enhance accuracy.

The inhibition efficiency percentage (IE%) values from methods such as WL, PDP, and EIS consistently show direct proportionality. This suggests the possibility of employing a single suitable method for assessing inhibitor efficiency, streamlining research, and reducing time and costs associated with corrosion inhibition testing.

All research demonstrates a direct correlation between experimental IE% and computational E binding, suggesting E binding’s ability to accurately predict inhibitor efficiency before experimental procedures. However, discrepancies between IE% and computational ΔN suggest that while ΔN is crucial for evaluating inhibitor effectiveness by assessing electron-transfer capability, it should not be solely relied on.

The variability in IE% across different inhibitors underscores the influence of factors like molecular structure, surface interactions, and experimental conditions on corrosion inhibition effectiveness.

The results from various experimental techniques consistently showed that inhibitor efficiency increased with higher inhibitor concentrations and lower temperatures. Langmuir isotherm analysis often revealed spontaneous adsorption with a mix of physical and chemical adsorption. However, some studies indicated an increase in efficiency at elevated temperatures, possibly due to the favoring of chemisorption at higher temperatures.

7 Future prospects and significance

The integration of theoretical calculations with experimental studies is revolutionizing corrosion inhibition research by providing detailed atomic and molecular insights. Future prospects include enhanced predictive models through AI, improved accuracy of computational methods, and the development of eco-friendly inhibitors. Computational techniques will help design nontoxic, biodegradable inhibitors and tailor solutions for specific materials and environments. Smart coatings and real-time monitoring will enhance protection measures, while interdisciplinary collaboration will foster innovation. These advancements will make corrosion inhibition more efficient, cost-effective, sustainable, and reliable, with significant implications for various industries. The future lies in the synergistic use of theoretical and experimental approaches, promising more effective and customized corrosion protection solutions.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to the Chemistry Department of Koya University for their assistance in this project.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors take full responsibility for the content of this manuscript and have approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: No funding was received for this study.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Abbass, M.K., Raheef, K.M., Aziz, I.A., Hanoon, M.M., Mustafa, A.M., Al-Azzawi, W.K., Al-Amiery, A.A., and Kadhum, A.A.H. (2024). Evaluation of 2-dimethylaminopropionamidoantipyrine as a corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in HCl solution: a combined experimental and theoretical study. Prog. Color Colorants Coat. 17: 1–10, https://doi.org/10.30509/pccc.2023.167134.1216.Search in Google Scholar

Abbaz, T., Bendjeddou, A., and Villemin, D. (2019). Theoretical analysis and molecular orbital studies of sulfonamides products with N-alkylation and O-alkylation. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 6: 91–101, https://doi.org/10.22161/ijaers.6.2.12.Search in Google Scholar

Abd-El-Nabey, B., Abd-El-khalek, D., El-Housseiny, S., and Mohamed, M. (2020). Plant extracts as corrosion and scale inhibitors: a review. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 9: 1287–1328.Search in Google Scholar

Abdallah, M., El-Etre, A.Y., Soliman, M.G., and Mabrouk, E.M. (2006). Some organic and inorganic compounds as inhibitors for carbon steel corrosion in 3.5 percent NaCl solution. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 53: 118–123, https://doi.org/10.1108/00035590610650820.Search in Google Scholar

Adamma, E.P., Nnabuk, E.O., Omoniy, I., and Israel, K. (2010). Quantum chemical studies on reactivity of glycine, leucine and aniline towards nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks with iron. 2010 International Conference on Biosciences.10.1109/BioSciencesWorld.2010.33Search in Google Scholar

Afshari, F., Ghomi, E.R., Dinari, M., and Ramakrishna, S. (2023). Recent advances on the corrosion inhibition behavior of Schiff base compounds on mild steel in acidic media. ChemistrySelect 8, https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202203231.Search in Google Scholar

Ahmed, L., Bulut, N., Kaygili, O., and Rebaz, O. (2023). Quantum chemical study of some basic organic compounds as the corrosion inhibitors. J. Phys. Chem. Funct. Mater. 6: 34–42, https://doi.org/10.54565/jphcfum.1263803.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Moubaraki, A.H., Ganash, A.A., and Al-Malwi, S.D. (2020). Investigation of the corrosion behavior of mild steel/H2SO4 systems. Moroc. J. Chem. 8: 264–279.Search in Google Scholar

Akbas, E., Othman, K.A., Çelikezen, F.Ç., Aydogan Ejder, N., Turkez, H., Yapca, O.E., and Mardinoglu, A. (2023a). Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel benzylidene thiazolo pyrimidin-3(5-H)-one derivatives. Polycyclic Aromat. Compd. 44: 3061–3078, https://doi.org/10.1080/10406638.2023.2228961.Search in Google Scholar

Akbas, E., Othman, K.A., Çelikezen, F.Ç., Aydogan Ejder, N., Turkez, H., Yapca, O.E., and Mardinoglu, A. (2023b). Synthesis, characterization, theoretical studies and in vitro embriyotoxic, genotoxic and anticancer effects of novel phenyl(1,4,6-triphenyl-2-thioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl)methanone. Polycyclic Aromat. Compd.: 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/10406638.2023.2276243.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Amiery, A.A., Yousif, E., Isahak, W.N.R.W., and Al-Azzawi, W.K. (2023). A review of inorganic corrosion inhibitors: types, mechanisms, and applications. Tribology Ind. 44: 313.10.24874/ti.1456.03.23.06Search in Google Scholar

Alahiane, M., Oukhrib, R., Albrimi, Y.A., Oualid, H.A., Bourzi, H., Akbour, R.A., Assabbane, A., Nahle, A., and Hamdani, M. (2020). Experimental and theoretical investigations of benzoic acid derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for AISI 316 stainless steel in hydrochloric acid medium: DFT and Monte Carlo simulations on the Fe (110) surface. RSC Adv. 10: 41137–41153, https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra06742c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Antunes, R.A. (2023). Advances in corrosion and protection of materials. Metals 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/met13061059.Search in Google Scholar

Ashassi-Sorkhabi, H., Majidi, M.R., and Seyyedi, K. (2004). Investigation of inhibition effect of some amino acids against steel corrosion in HCl solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 225: 176–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2003.10.007.Search in Google Scholar

Askari, M., Aliofkhazraei, M., Jafari, R., Hamghalam, P., and Hajizadeh, A. (2021). Downhole corrosion inhibitors for oil and gas production – a review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100128.Search in Google Scholar

Assad, H. and Kumar, A. (2021). Understanding functional group effect on corrosion inhibition efficiency of selected organic compounds. J. Mol. Liq. 344, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117755.Search in Google Scholar

Baer, D. (1985). Solving corrosion problems with surface analysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 20: 382–396, https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-5963(85)90163-1.Search in Google Scholar

Batool, F., Akbar, J., Iqbal, S., Noreen, S., and Bukhari, S.N.A. (2018). Study of isothermal, kinetic, and thermodynamic parameters for adsorption of cadmium: an overview of linear and nonlinear approach and error analysis. Bioinorgan. Chem. Appl. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3463724.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Beake, B.D., Liskiewicz, T.W., Bird, A., and Shi, X. (2020). Micro-scale impact testing – a new approach to studying fatigue resistance in hard carbon coatings. Tribol. Int. 149: 105732, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2019.04.016.Search in Google Scholar

Bedair, M.A., Elaryian, H.M., Gad, E.S., Alshareef, M., Bedair, A.H., Aboushahba, R.M., and Foud, A.E.A.S. (2023). Insights into the adsorption and corrosion inhibition properties of newly synthesized diazinyl derivatives for mild steel in hydrochloric acid: synthesis, electrochemical, SRB biological resistivity and quantum chemical calculations. RSC Adv. 13: 478–498, https://doi.org/10.1039%2Fd2ra06574f.10.1039/D2RA06574FSearch in Google Scholar

Belal, K., El-Askalany, A.H., Ghaith, E.A., and Fathi Salem Molouk, A. (2023). Novel synthesized triazole derivatives as effective corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in 1M HCl solution: experimental and computational studies. Sci. Rep. 13: 22180, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49468-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Belghiti, M.E., Echihi, S., Mahsoune, A., Karzazi, Y., Aboulmouhajir, A., Dafali, A., and Bahadur, I. (2018). Piperine derivatives as green corrosion inhibitors on iron surface; DFT, Monte Carlo dynamics study and complexation modes. J. Mol. Liq. 261: 62–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2018.03.127.Search in Google Scholar

Bendjeddoua, A., Abbaza, T., Gouasmiab, A., and Villeminc, D. (2016). Quantum chemical studies on molecular structure and reactivity descriptors of some p-nitrophenyl tetrathiafulvalenes by density functional theory (DFT). Acta Chim. Pharm. Indica 6: 32–44.Search in Google Scholar

Bensouda, Z., El Assiri, E.H., Sfaira, M., Ebn Touhami, M., Farah, A., and Hammouti, B. (2019). Extraction, characterization and anticorrosion potential of an essential oil from orange zest as eco-friendly inhibitor for mild steel in acidic solution. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 5, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40735-019-0276-y.Search in Google Scholar

Bhardwaj, N., Sharma, P., and Kumar, V. (2021). Phytochemicals as steel corrosion inhibitor: an insight into mechanism. Corros. Rev. 39: 27–41, https://doi.org/10.1515/corrrev-2020-0046.Search in Google Scholar

Borchers, A. and Pieler, T. (2010). Programming pluripotent precursor cells derived from Xenopus embryos to generate specific tissues and organs. Genes 1: 413–426, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes1030413.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cao, F., Song, G.-L., and Atrens, A. (2016). Corrosion and passivation of magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci. 111: 835–845, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2016.05.041.Search in Google Scholar

Chauhan, D.S., Verma, C., and Quraishi, M.A. (2021). Molecular structural aspects of organic corrosion inhibitors: experimental and computational insights. J. Mol. Struct. 1227, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129374.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, L., Lu, D., and Zhang, Y. (2022). Organic compounds as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in HCl solution: a comprehensive review. Materials 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15062023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central