Abstract

This paper summarizes the anti-corrosive and anti-erosive properties of water-ethylene glycol based commercial coolant dispersed with nanomaterials. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), silver nanoparticles (Ag) and nanosized alumina particles (Al2O3) are dispersed in 0.5% weight in automotive coolants and tested for anti-corrosive properties as per ASTM standards. Prior to dispersion, the nanomaterials are surface modified to get good stability in coolant solutions. The corrosion resistance is measured in terms of weight loss of materials that is commonly used in automotive systems. It is found that oxidized MWCNTs are suitable to automotive systems while silver and Al2O3 nanoparticles are found to be deleterious in nature.

1 Introduction

Diesel engines are the main prime movers of an industry. Advances in diesel engine technology are motivated by requirements for increased power, reduced emission, improved fuel economy and longer sustainability. Major developments have been made in heavy duty diesel engine technology with the application of lighter and softer metals and turbocharging to meet strict environmental regulations for emissions. Because of this, the coolant flow rates, turbulence, pressure drops and deaeration are also becoming more severe, requiring improved coolant configurations in addition to erosion-corrosion protection, cavitation protection and elastomer, seal and hose compatibility. Coolant pump air induction and cylinder head exhaust gas leakage into the coolant system could aggravate corrosion, thereby producing irreversible damage to the cylinder liner. Ethylene glycol-water based engine coolants leak into the cylinder more than pure water does and corrodes the surfaces.

The effects of corrosion in an engine cooling system will lead to the following: (1) oxidization of the metals of the engine system by uniform wastage or localized attack leading to corrosion and (2) insoluble corrosion products that block the radiator and reduce the heat transfer rates. In diesel engines, the protection of wet cylinder liners against cavitation corrosion or liner pitting is of utmost importance. Liner pitting occurs due to cavitation on the coolant side of the cylinder liner resulting in the erosion of metal. Cylinder liners vibrate because of the motion of the piston, causing the low pressure regions of the fluid to generate vapor bubbles that collapse on the surface of the liner. This impingement on the metal surface removes protective films and erodes the surface. Further, erosion-corrosion protection is vital because of the increased use of soft metals such as aluminum, copper and lead in engine and cooling system components. Erosion-corrosion is triggered by excessive flow conditions over an extended period of time, which generates shear forces sufficient to remove corrosion passivating films or naturally protective oxides.

In the early days of ethylene glycol based engine coolants, the use of simple inhibitor systems based on borates, phosphates, silicates and a soft metal inhibitor was sufficient to satisfy the needs of a cast iron engine and copper/brass radiator. Subsequently, the engine coolant trend became amine phosphate based to shield aluminum and alloy metals, making the use of borates and silicates outdated. The movement to non-amine coolant was due to Norway’s 1987 regulations on triethanolamine; thus, phosphate and organic acid salt based coolants, P-OAT, were developed. The use of aluminum and other light metals for engine and cooling part components has increased many folds because of their light weight. With this, the corrosion inhibition in localized form such as pitting and crevice corrosion has become crucial. The evaluation of heat transfer and high temperature corrosion properties of an engine coolant requires specific testing of aluminum samples compared with other metals. Several studies were made to develop a new class of engine coolants that prevent corrosion and thereby improve the overall performance of the cooling system (Ailor, 1980); Beal, 1984, 1993, 1999). These studies were conducted on formulated coolants by observing the changes in the weight of the metal coupons used in coolant systems under accelerated conditions to determine their anti-corrosive and anti-erosive properties.

It was estimated that the heat rejection of the coolant increases by 25%–35% (McGeehan, 2002) because of the introduction of turbocharging in heavy duty diesel engines, resulting in the increase in bulk coolant temperatures, and the radiator size cannot be increased in order to make up for the increased coolant heat rejection. These high bulk coolant temperatures lead to localized boiling, increased degradation of the coolant and reduced coolant life. Moreover, the auxiliary equipment, such as air conditioning units, automatic transmissions systems and oil coolers, also adds an extra thermal load on the cooling system particularly under heavy load and idle conditions. In addition, some heavy vehicles normally operate with numerous starts and stops, often resulting in the hot soaking of the coolant that rises the coolant temperature causing it to boil. Several approaches are employed by engine manufacturers to handle the increased heat loads on the coolant. These include raising the pressure limit on the radiator cap to increase the boiling point, using higher performance fans, increasing water pump size and speed for increased coolant flow rates and using larger and more efficient heat exchangers. Most of these methods would put further load on the engine, resulting in power drops.

One of the suggested approach by several researchers (Lee & Choi 1996, Lee et al. 1999; Choi et al., 2001; Eastman et al., 2001; Li & Xuan 2002; Assael et al., 2004, 2005; Liu et al., 2005; Das et al. 2006; Wang & Mujumdar, 2007, 2008) explains that the effective heat transfer in cooling systems can be improved with the dispersion of metallic nanomaterials (Cu, Al, Fe, Au and Ag), nonmetallic materials (Al2O3, CuO, Fe3O4, TiO2 and SiC) and single and multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). Furthermore, because of the emergence of better synthesizing techniques, the cost of premium nanomaterials is coming down from day to day. Dispersion of nanomaterials can be affordable in view of their best heat transfer properties. Most of the metallic nanoparticles possess a very high thermal conductivity, but stability in fluid and their reactivity are two factors that hinder their use in nanofluid applications. Nonmetallic nanoparticles as Al2O3 have a lower thermal conductivity than metallic nanoparticles, but they exhibit properties such as excellent stability and chemical inertness; however, the disadvantage is that they are more erosive in comparison with metallic particles and carbon nanotubes. It is extremely important to investigate the effect of nanomaterials in terms of mechanochemical damages such as corrosion and erosion before their commercial application.

Among the nanomaterials mentioned, the advantage of MWCNTs is that they can be oxidized with acids in order to attach functional groups to their wall structure, thereby obtaining good dispersion and stability. It has been proven (Yang et al., 2006, 2011; Zhang et al., 2006; Xue et al., 2008; Avilés et al. 2009; Yang et al., 2009) that oxidation does not change the morphology of MWCNTs, and the special properties of MWCNTs are retained. All components in the cooling system should not get corroded or eroded because of the passage of coolant in the system. Although several studies have been made on heat transfer enhancement using dispersion nanomaterials in coolants, there are only a few studies on the corrosive and erosive aspects of dispersion of nanomaterials in coolants with a quite good number of reliable reports on the mechanical, chemical and mechanochemical damage due to some nanofluids.

Alimorad et al. (2013) prepared water-MWCNT nanofluid and studied the corrosion rate of carbon steel. It was observed that functionalized MWCNTs prevent carbon steel corrosion to some extent in comparison with the distillated water. However, nonfunctionalized MWCNTs dispersed in water with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium dodecyl benzene sulphonate (SDBS) as surfactant increased the corrosion current. Baghalha & Kamal-Ahmadi (2011) investigated the corrosion behavior of brass using potentiodynamic polarization in water-carbon nanotube nanofluids using SDS as surfactant. It was found that SDS at a lower concentration of 0.005 m reduced the brass corrosion current density by 81% but enhanced corrosion at higher concentrations.

Celata et al. (2014) conducted experimental studies on the effects of the flow of water-based nanofluids dispersed in TiO2, Al2O3, ZrO2 and SiC over target materials aluminum, copper and stainless steel. It was found that the specific combination of nanofluid-target material, in some cases, led to severe damage of the tested target, thus highlighting the need for an adequate preliminary investigation of the possible interactions between the selected nanofluid and the apparatus materials before its adoption as a heat transfer fluid.

Rashidi et al. (2013a,b, 2014) studied the erosion-corrosion synergistic effects of Al2O3-sea water nanofluids to carbon steel and established that compared with the base fluid, the erosion rate of carbon steel in nanofluids is higher. They also reported the corrosion rate of carbon steel in nanosuspensions containing water and functionalized MWCNT. It was observed that the functionalized MWCNTs prevent the corrosion of carbon steel to some extent in comparison with base fluids.

Rashmi et al. (2014) extensively studied water and ethylene glycol based nanofluids with emphasis to corrosion effects. The effect of nonfunctionalized carbon nanotubes on the corrosion of three different metals, namely aluminum alloy, stainless steel and copper, was investigated. It was observed that irrespective of the fluid used, the highest rate of corrosion was observed in aluminum, followed by stainless steel and copper. The corrosion rate was also found to increase with the increase in temperature in all cases.

Routbort et al. (2010) and Singh et al. (2009) in their works investigated the damage caused by nanofluids to a car radiator. They studied the reduction in weight of radiators resulting from the flow of several nanofluids at different speeds and collision angles. It was observed that base fluids such as water, ethylene and trichloroethylene glycols caused no erosion to the surface of the radiator even at velocities as high as 9.6 m/s and at 30–90° impact angles during flow. Copper nanofluid at a velocity of 9.6 m/s and an impact angle of 90° produced a higher wear rate than the base fluid, causing severe erosion due to the oxidation of copper nanoparticles. With alumina (Al2O3) nanofluids, although wear was observed, it was lower than the copper nanofluid. No weight reduction due to erosion was observed with CuO-ethylene glycol and silicon carbide (SiC)-water nanofluid for all volume percentages, velocities and impact.

Srinivas et al. (2016) studied the effect of dispersion of oxidized MWCNTs in carboxylated water-based coolants. It was found that oxidized MWCNTs disperse better because of the presence of carboxylate groups on the surface and do not deteriorate the anti-corrosive properties.

From the above studies, it can be observed that the corrosion and erosion rates of nanofluids depend on the type of metal on which they are tested, the surface modification technique and the operating temperature. The tests carried out by the authors are more focused on the type of nanofluid used, and the metals used in their study are limited to aluminum, steel and copper. ASTM D3306 prescribes the specification for glycol-based engine coolants for automobile and light-duty services. The physical and chemical property requirements as well as allowable corrosion, erosion and erosive-corrosion requirements of engine coolants are clearly detailed. For any coolant to be suitable for automotive applications, it must pass the requirements recommended. The present article investigates the effect of coolants with dispersed nanomaterials on all the metals used in automotive cooling system, and a detailed study of corrosive and erosive characteristics is made. All the tests are done as per ASTM standards to meet SAE regulations for coolants.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Fully formulated hybrid coolant (HP Koolgard, manufactured by Hindustan Petroleum corporation Ltd, India), which is an ethylene glycol concentrate with a combination of carboxylates and tolyltriazole as additive, is used as the base coolant. Three types of nanomaterials, viz. a metal, a metal oxide purchased from M/s Sigma Aldrich India Pvt limited and MWCNTs purchased from M/s Cheaptubes Inc., USA, were selected as materials for dispersion in coolants. The composition of the coolant concentrate samples and the nanomaterials dispersed are listed in Table 1.

Composition of the base coolant concentrate and the nanomaterials dispersed.

| Serial No. | Composition | Weight percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ethylene glycol | 90%–95% |

| 2 | Carboxylates | 3%–5% |

| 3 | Tolyltriazole | 0.1%–0.3% |

| 4 | pH buffer | Remaining (to give a pH of 10–12) |

| 5 | Nanomaterials dispersed | 1. MWCNTs (length: 1–25 μm, dia: 20–40 nm) 2. Silver nanoparticles (dia: 50–75 nm) 3. Alumina nanoparticles (Al2O3) (dia: 30–50 nm) |

2.2 Surface modification of the nanomaterials

To improve the dispersion stability of the nanomaterials in coolants, the covalent and noncovalent techniques were employed. Ag and Al2O3 nanoparticles were dispersed in coolants by stabilizing them with the surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate. A two-step process was followed to oxidize MWCNTs to attach functional groups over the surface to make them water soluble. In the first step, pristine MWCNTs were refluxed in 6 m HCl for 6 h to remove metal particles and soot. In the second step, the MWCNTs were refluxed in 3:1 ratio 6 m H2SO4 and 6 m HNO3 mixture for 6 h. Any increase in the treatment time would lead to the destruction of the chemical structure of MWCNTs. After reflux, the MWCNTs were washed in water to neutral pH, filtered and dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 80°C to obtain oxidized and water-soluble MWCNTs.

2.3 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis

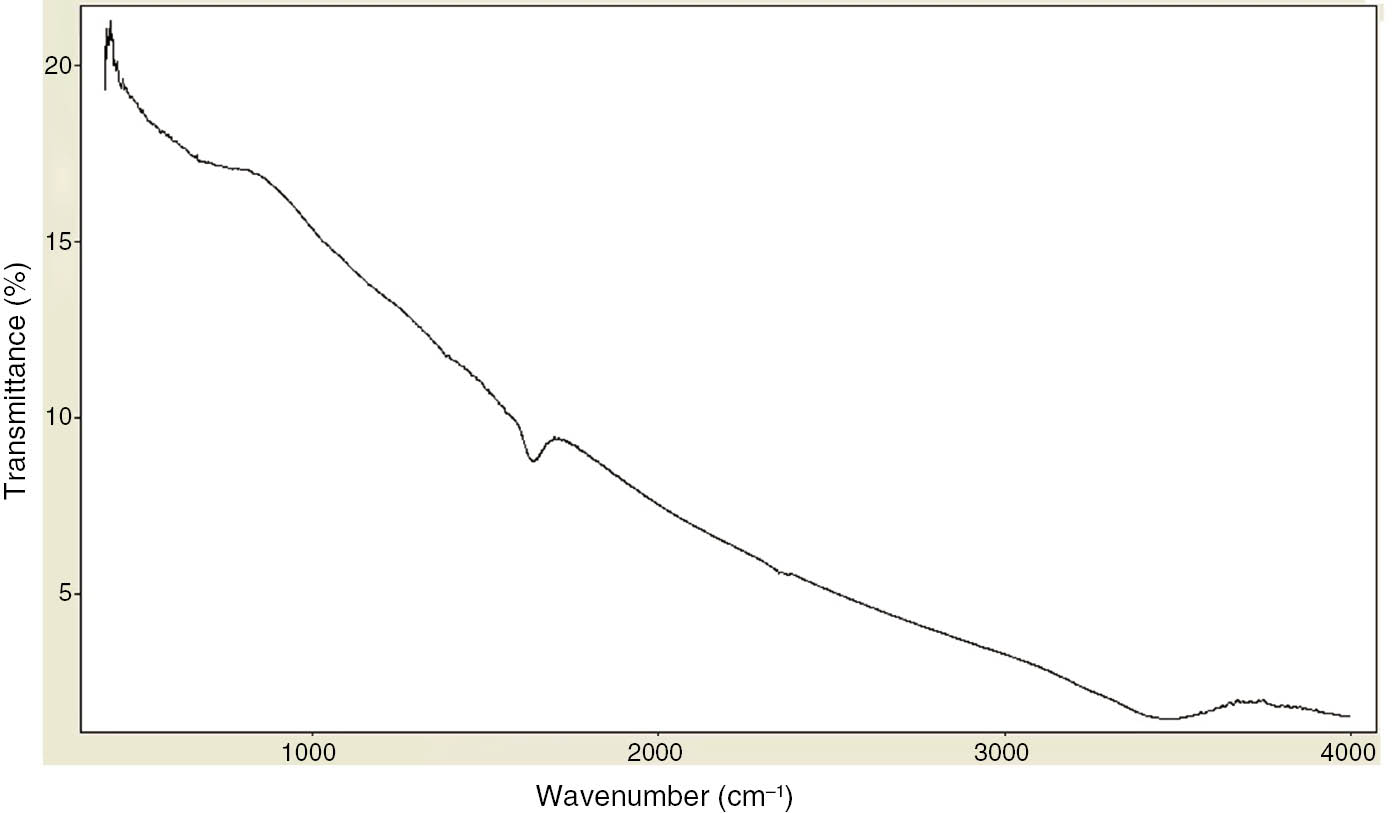

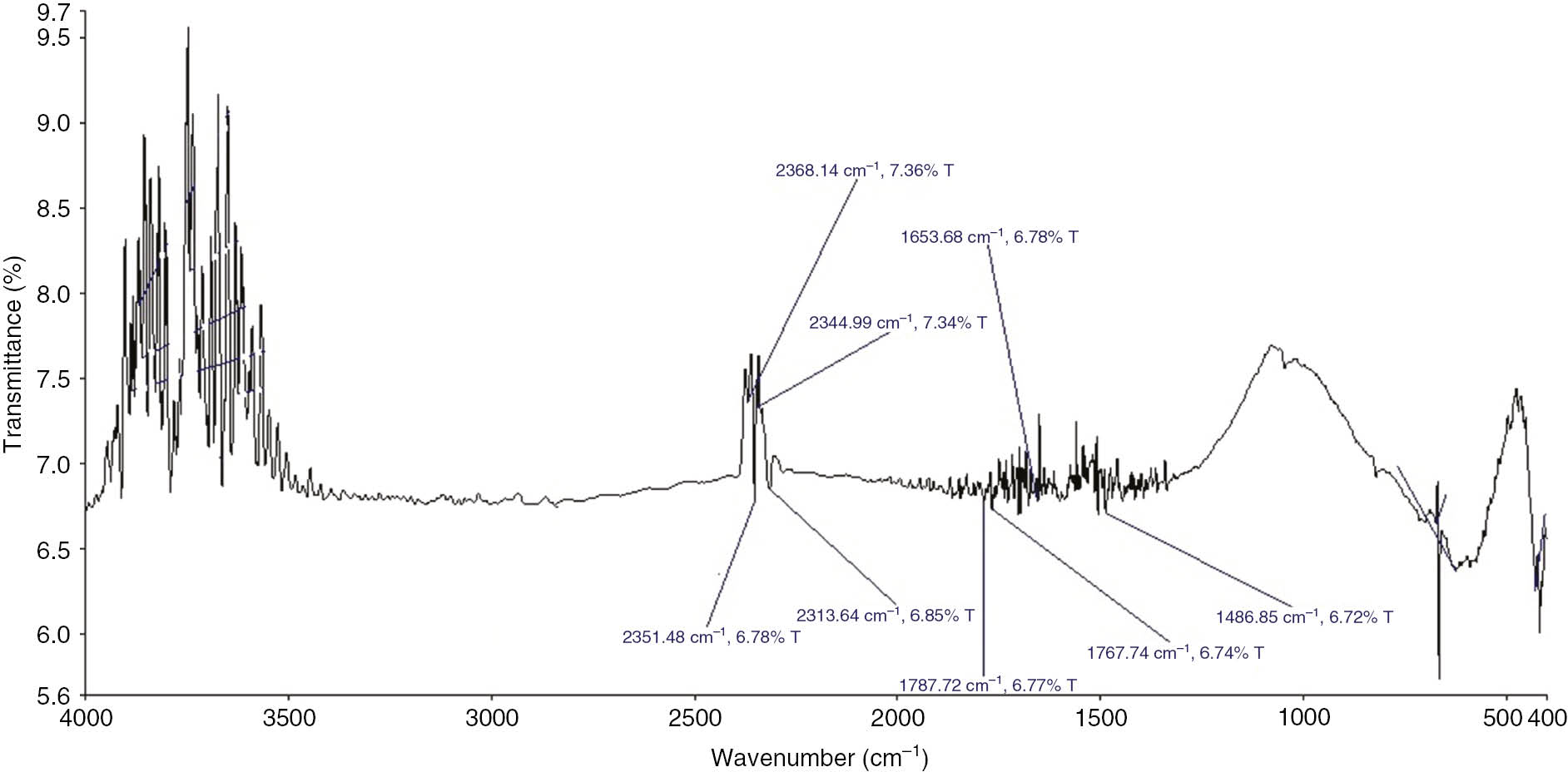

The surface modification done on MWCNTs can be characterized by analyzing the modified MWCNTs for the attached OH and COOH groups using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Figure 1 shows the spectrum of the pristine MWCNTs indicating no functional groups. Figure 2 shows the spectrum of the oxidized MWCNTs with characteristic peaks at 1110 and 1720 cm−1, which are C-O-C and carbonyl (C=O) stretching bands, respectively. The peak at 1406 cm−1 is associated with the hydroxyl group O-H. These carboxyl and carbonyl groups allow the MWCNTS to remain stable in polar fluids such as water and ethylene glycol for an extended period of time.

FTIR spectrum of pristine MWCNTs.

FTIR spectrum of oxidized MWCNTs.

2.4 Preparation of coolant samples and investigation of fluid stability

The conventional ethylene glycol based coolant (HP Koolgard) was mixed with distilled water in 30% and 50% concentrations. The pH of the solution was maintained in the range of 9–10. Although several studies were made using higher concentrations of nanomaterials, in the present study the nanofluids were prepared by dispersing the nanomaterials in 0.5% weight fraction. The surface-modified nanomaterials were dispersed into the liquid medium using a probe ultra sonicator.

The fluid stability of the colloid was measured in terms of zeta potential, which is the potential difference between the dispersion medium and the stationary layer of the fluid attached to the dispersed particle. A value of 25 mV (positive or negative) can be taken as the arbitrary value that separates low-charged surfaces from highly charged surfaces. The effect of carboxylate additives on the stability of the coolant is also tested by conducting a stability test on normal ethylene glycol-water mixtures dispersed with MWCNTs.

It was found that the carboxylate additives have profound influence on the stability of MWCNTs. The relative stability of ethylene glycol-water mixtures with dispersion of MWCNTs is compared in Table 2. It can be observed that the stability of the commercial coolant-water mixtures with dispersion of MWCNTs is greater because of the presence of functional groups compared with the dispersion with other nanoparticles. Dispersed silver and aluminum nanoparticles exhibited moderate stability.

Stability of the fluids using the zeta potential analysis.

| Sample | Zeta potential (mV) |

|

|---|---|---|

| First day | After 2 months | |

| Coolant-water (50:50)+0.5% MWCNTs | −61.8 | −56.4 |

| Coolant-water (30:70)+0.5% MWCNTs | −52.4 | 53.4 |

| Coolant-water (50:50)+0.5% silver nanoparticles | −27.5 | −21.9 |

| Coolant-water (30:70)+0.5% silver nanoparticles | 22.9 | 20.6 |

| Coolant-water (50:50)+0.5% alumina nanoparticles | −27.9 | −24 |

| Coolant-water (30:70)+0.5% alumina nanoparticles | −26.9 | −20.8 |

3 Corrosion tests

A number of engine manufacturers have introduced test requirements for the protection of different metals used in engines. The important test requirements for engines are the glassware corrosion test and the simulated service corrosion test. In the case of diesel engine liners, an additional requirement of cavitation corrosion (erosive corrosion) has been introduced by engine companies. All corrosion tests are done as per ASTM standards (ASTM D1384, ASTM G32 and ASTM D2570).

3.1 Glassware test as per ASTM D1384

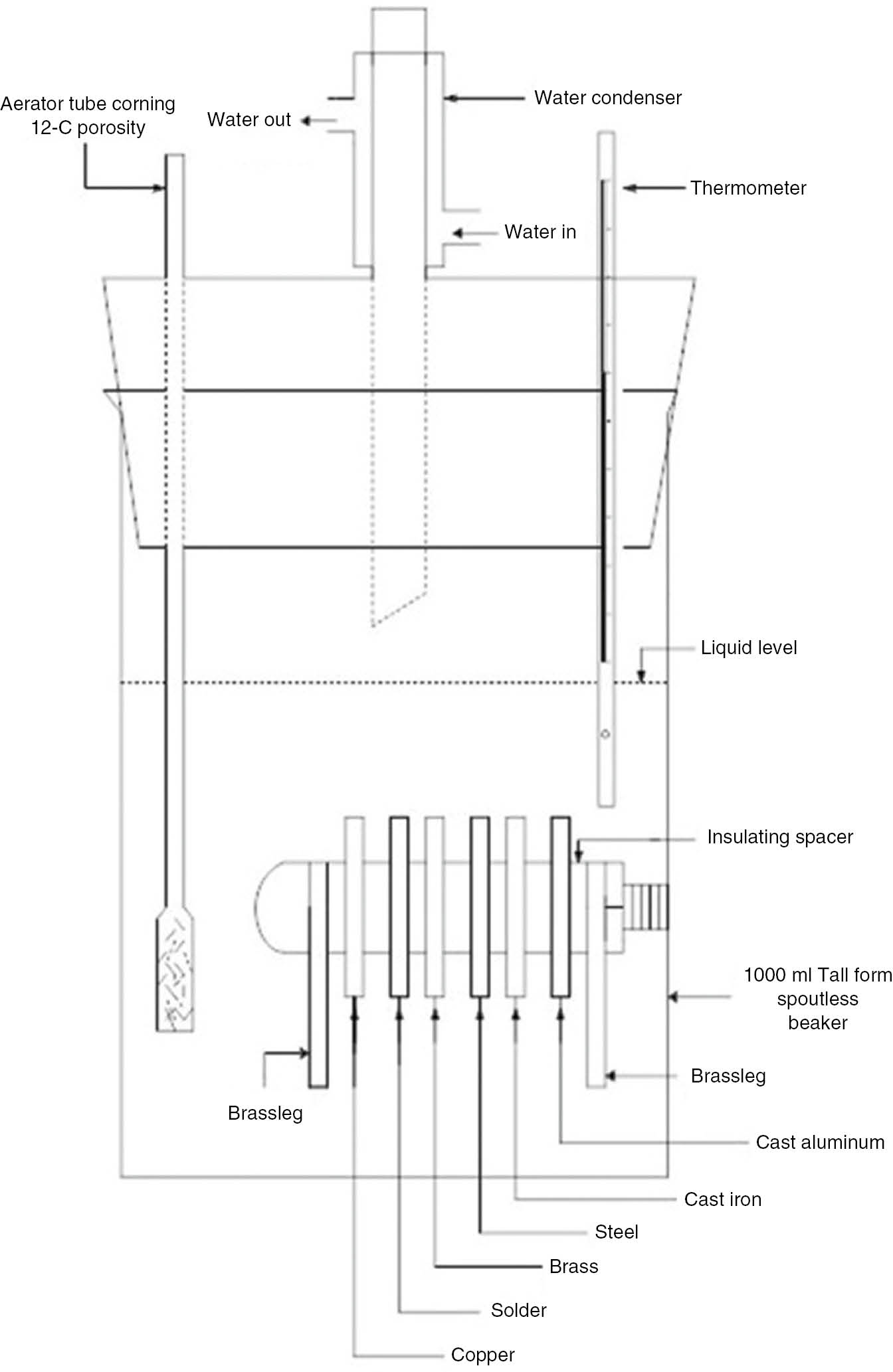

The glassware corrosion test is an accelerated corrosion test developed to assess the automotive coolant’s resistance to the corrosion of the coupons of metals typically present in engine cooling systems; that is, copper, solder, brass, cast iron, mild steel and aluminum are totally immersed in an engine coolant solution mixed with corrosive water under aerated conditions. Corrosive water consists of 100 ppm each of sulfate, chloride and bicarbonate ions mixed as sodium salts to accelerate corrosion. Corrosive water along with aeration accelerates oxidation simulating an automotive environment. The details are as given in Table 3. The corrosion inhibitive properties of the test solution are evaluated on the basis of the weight changes incurred by the coupons. The schematic of the test setup is shown in Figure 3.

Details of glassware testing.

| Amount of coolant sample | 750 ml |

| Duration of test | 14 days |

| Temperature of coolant | 88°C |

| Material of coupons | Copper (SAE CA110), solder (SAE 3A), brass (SAE CA260), mild steel (SAE 1020), cast iron (SAE G3500), aluminum (SAE 329) |

Glassware corrosion setup.

The coolant samples with a commercial coolant are diluted with DI water in 50:50 and 30:70 ratios and dispersed with nanomaterials. The commercial coolant exhibited good corrosion inhibition properties. The results of the glassware test are tabulated in Tables 4 and 5.

Glassware test results for coolant-water mixture (30:70).

| Coupons | Copper | Solder | Brass | Mild steel | Cast iron | Aluminum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (mg) | ||||||

| Allowable weight loss as per ASTM D3306/SAE specifications | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Base coolant | 1.667 | 1.667 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.667 |

| Base coolant+0.5% oxidized MWCNTs | 1.667 | 1.000 | 0.333 | 1.333 | 0.333 | 0.667 |

| Base coolant+0.5% Ag nanoparticles | 2.667 | 25.267 | 2.333 | 1.984 | 2.227 | 80.24 |

| Base coolant+0.5% Al2O3 nanoparticles | 3.667 | 18.233 | 4.66 | 2.22 | 1.33 | 1.267 |

Glassware test results for coolant-water mixture (50:50).

| Coupons | Copper | Solder | Brass | Mild steel | Cast iron | Aluminum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (mg) | ||||||

| Maximum allowable weight loss for automotive coolants as per ASTM D3306/SAE specifications (mg) | 10 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Base coolant | 1.000 | 0.667 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.333 | 0.667 |

| Base coolant+0.5% oxidized MWCNTs | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.667 | 1.667 | 0.667 | 0.667 |

| Base coolant+0.5% Ag nanoparticles | 2.233 | 26.24 | 2.103 | 1.833 | 1.946 | 1.16 |

| Base coolant+0.5% Al2O3 nanoparticles | 2.667 | 17.33 | 4.167 | 2.267 | 78.333 | 1.13 |

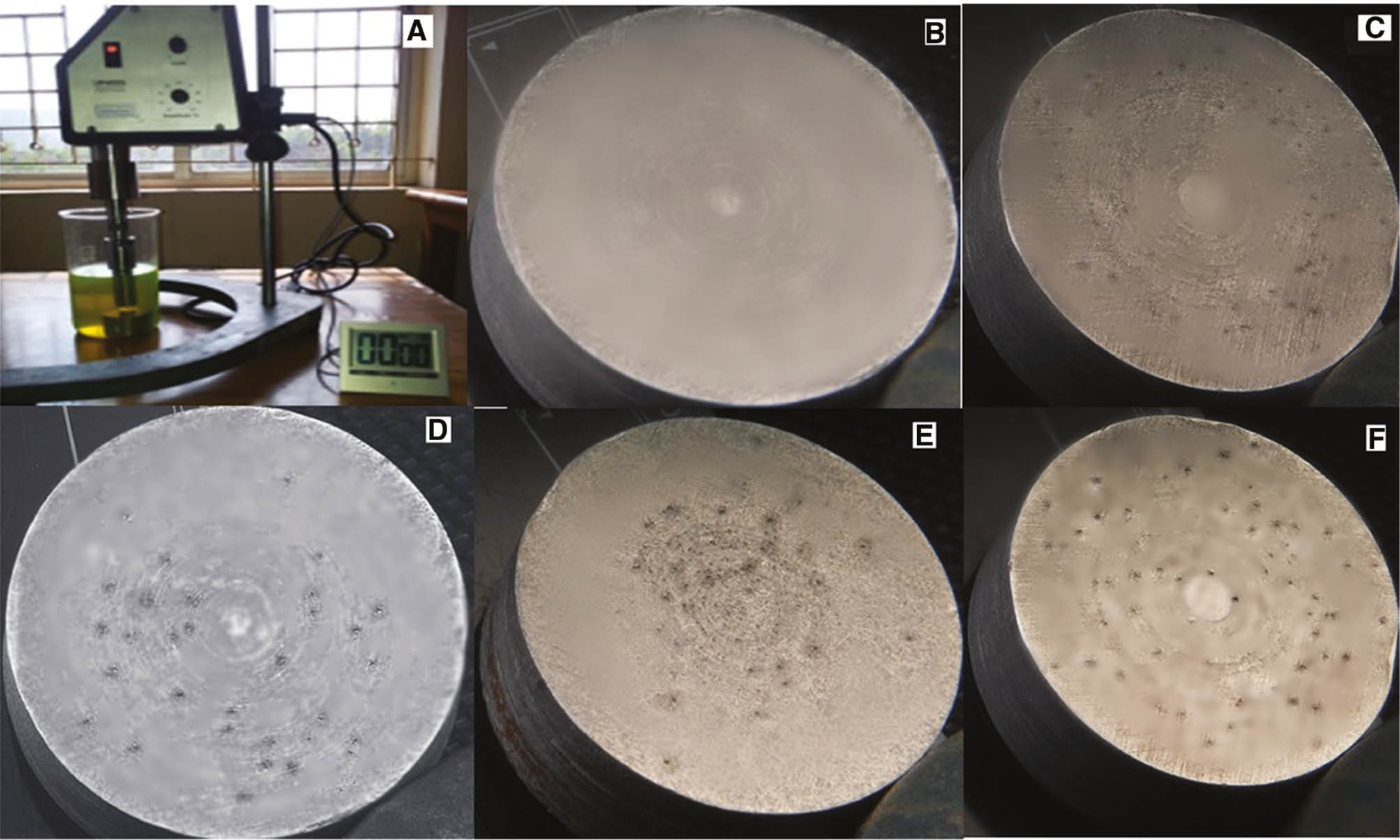

The oxidized MWCNTs and alumina nanoparticles when dispersed in the base coolant resisted corrosion of all six metals, and results are similar to the base coolant sample. The weight loss in all six metal coupons was found to be far below normal limits as suggested by the ASTM D3306 standard, indicating better corrosion inhibition with carboxylate additives. Silver nanoparticles dispersed in coolant severely corroded the aluminum coupon. The photographs of the test coupons before and after the test are shown in Figure 4.

Test coupons after the glassware corrosion test.

3.2 Cavitation corrosion test

Diesel cylinder liners vibrate because of the motion of the piston within the cylinder, causing the low pressure regions of the fluid on the coolant side to generate vapor bubbles that collapse on the surface of the liner. The formation and collapsing of the bubbles on the metal surface removes the protective films and erode the metal. This test method as per ASTM G32 is used to estimate the relative resistance of materials to cavitation erosion in terms of weight loss under conditions similar to the one encountered in wet liners.

The metal coupons to be tested were made of aluminum (SAE 329) and were weighed and immersed into a container containing the test coolant. A 20 kHz ultrasonic horn was placed over the coupon, and the longitudinal ultrasonic vibrations generated by an ultrasonic horn were transmitted into the liquid as ultrasonic waves consisting of alternate expansions and compressions. The pressure fluctuations pulled the liquid molecules apart creating micro-bubbles that implode violently on the surface of the coupon causing millions of shock waves, extremes in pressures and temperatures on the surface and triggering cavitation erosion similar to that of liner pitting. The condition and materials are listed in Table 6.

Details of the erosion testing.

| Amount of coolant sample | 250 ml |

| Duration of test | 10 Cycles of 1 h duration |

| Temperature of coolant | Room temperature |

| Material of coupon | Aluminum (SAE 329) |

| Frequency of the wave pulse | 20 kHz |

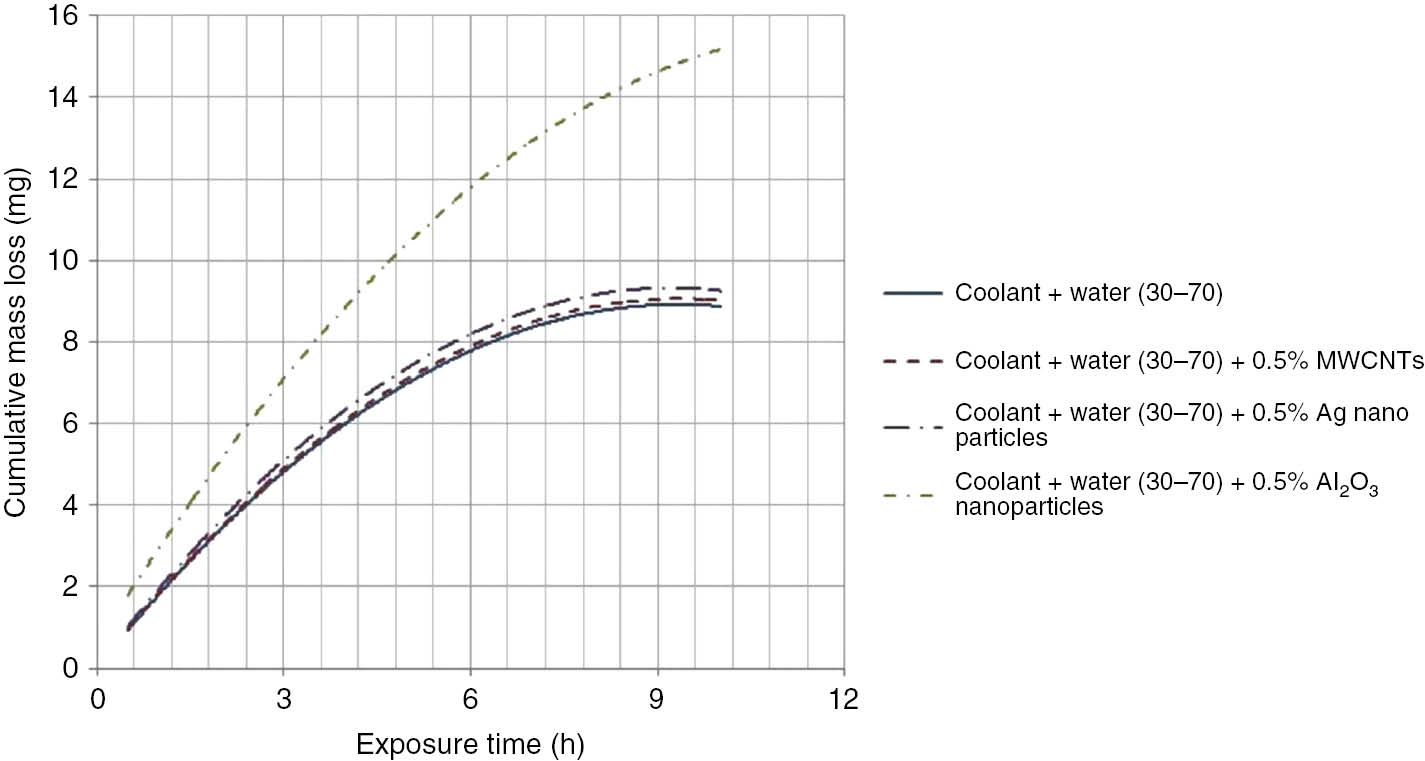

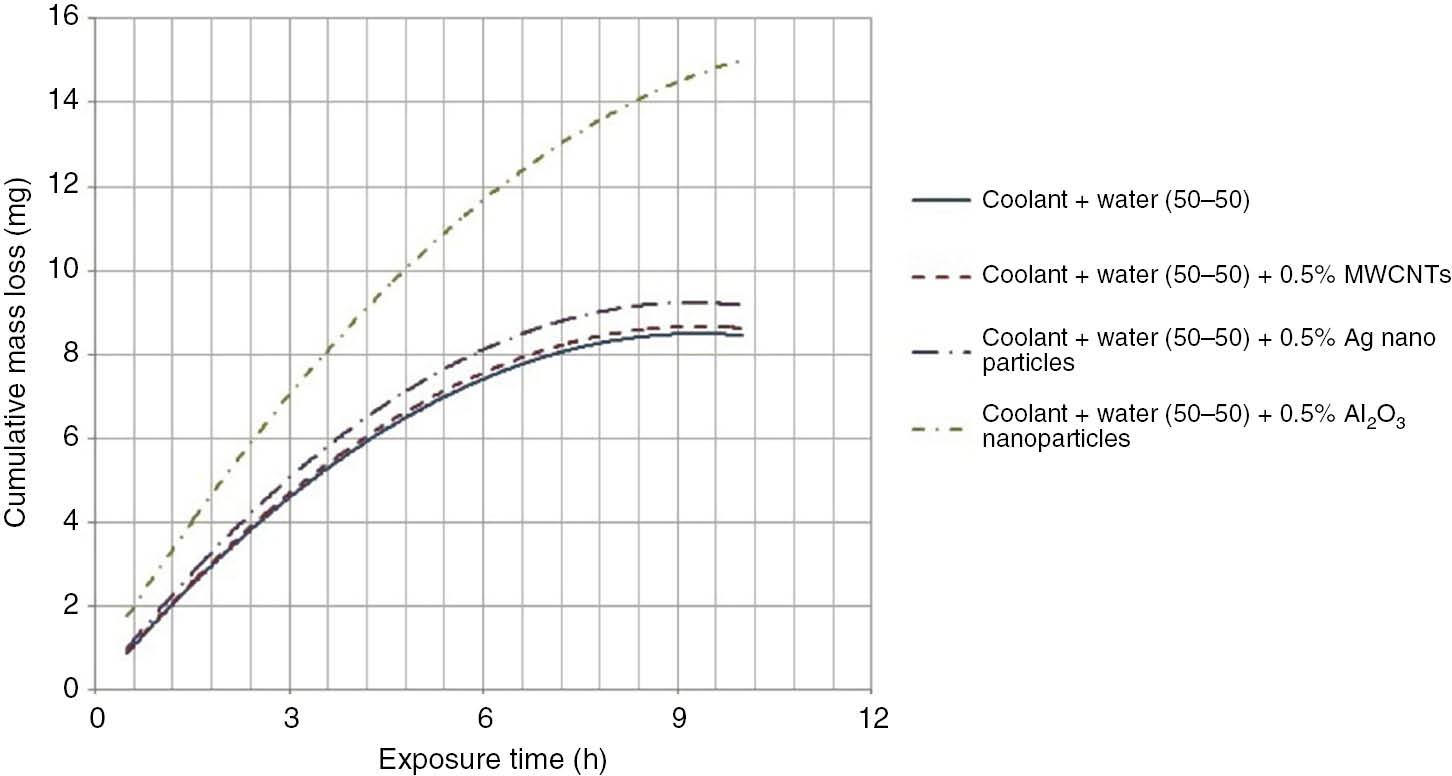

Initially, the aluminum coupon was subjected to cavitation for 1 h. After 1 h of test, the coupon was removed, cleaned with water and dried in a vacuum oven. After drying, the weight of the coupon was noted down. This test cycle was repeated 10 times to obtain a history of mass loss versus time. The samples with coolant-water mixture in 50:50 and 30:70 compositions along with the same dispersion with 0.5% nanomaterials were tested for cavitation corrosion. The cavitation test results are shown in Table 7. Graphs showing cumulative weight loss over 10 h period for different coolants are shown in Figures 5 and 6. From the graphs, the erosion trend is found, and the maximum erosion rate of the 10 h cycle is calculated. The results are tabulated in Table 7. The test setup and coupon samples before and after the test with test coolants are shown in Figure 7. The dispersion of oxidized MWCNTs and silver nanoparticles in coolants resulted in less cavitation erosion, which is similar in trend to that of base fluids. Coolant with alumina nanoparticles gave considerably higher cavitation erosion losses because of their abrasive nature.

Cavitation corrosion test results.

| Coolant sample | Maximum erosion rate of aluminum coupon (mg) |

|---|---|

| Coolant-water (30:70) | 7.26 |

| Coolant-water (30:70)+0.5% oxidized MWCNTs | 7.37 |

| Coolant-water (30:70)+0.5% Ag nanoparticles | 7.63 |

| Coolant-water (30:70)+0.5% Al2O3 nanoparticles | 11.41 |

| Coolant-water (50:50) | 6.91 |

| Coolant-water (50:50)+0.5% oxidized MWCNTs | 7.06 |

| Coolant-water (50:50)+0.5% Ag nanoparticles | 7.55 |

| Coolant-water (50:50)+0.5% Al2O3 nanoparticles | 11.3 |

Graph showing erosion of aluminum coupon with a coolant-water combination of 30:70.

Graph showing erosion of aluminum coupon with a coolant-water combination of 50:50.

Details of the cavitation corrosion test and the test coupons after the test with different fluids. (A) Cavitation corrosion test setup, (B) pristine aluminum coupon, (C) aluminum coupon after the test using the base coolant, (D) aluminum coupon after the test using the MWCNT-based nanofluid, (E) aluminum coupon after the test using the silver nanofluid and (F) aluminum coupon after the test using alumina nanofluid.

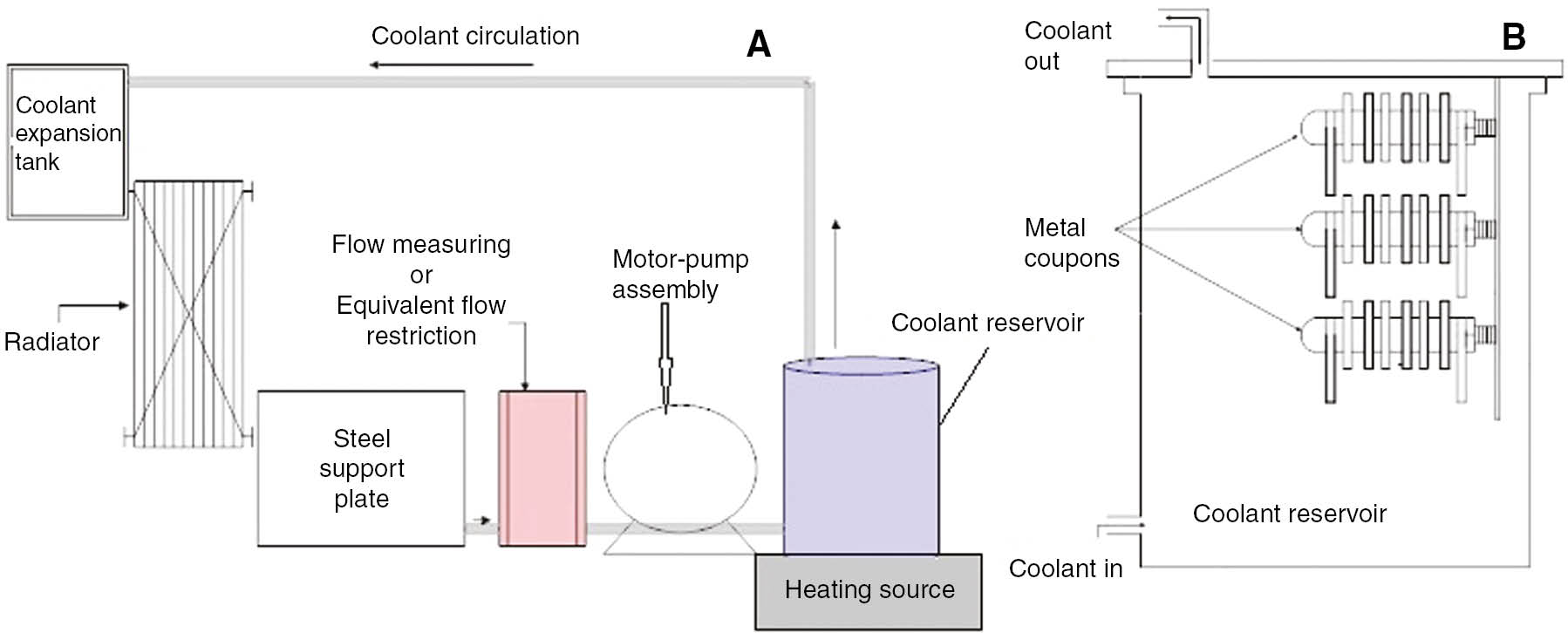

3.3 Simulated service corrosion test

This test as per ASTM D2570 evaluates the effect of a circulating engine coolant on metal test coupons and automotive cooling system components under controlled, essentially isothermal laboratory conditions. An engine coolant is circulated for 1064 h at 190°F (88°C) in a flow loop consisting of a metal coolant reservoir, an automotive coolant pump run by motor and an automotive radiator connected by rubber hoses as shown in Figure 8. Test coupons, components and conditions are specified in Table 8.

Simulated service corrosion setup: (A) coolant loop and (B) coolant reservoir with coupon bundles.

Details of the simulated service corrosion test.

| Amount of coolant sample | 5000 ml |

| Duration of test | 1064 h |

| Temperature of coolant | 88°C |

| Material of coupons | Copper (SAE CA110), solder (SAE 3A), brass (SAE CA260), mild steel (SAE 1020), cast iron (SAE G3500), aluminum (SAE 329) |

| Automotive components | Components used in four, six or eight-cylinder automobile engines in the 1.6–5.0 l range engines Coolant pump: Aluminum pump with matching front end and back covers to deliver flow rate in the range 70–100 LPM. Radiator: An aluminum radiator with coolant recovery tank and radiator pressure cap to withstand 80 to 100 kPa pressure Electric motor: drip proof 1.1 kW motor |

| Coolant reservoir | Material: SAE G3500 gray iron representing that of the engine cylinder block |

As the test is dynamic in nature involving flow of pressurized fluid, coolants with Al2O3 and Ag were prepared with pristine nanomaterials without surface modification. This is done to prevent the formation of foam due to the surfactant the affects the flow. In the case of the coolant with MWCNTs, the testing was carried out by dispersing oxidized MWCNTs.

The test coupons that are representative of the engine cooling system metals were mounted inside the coolant reservoir. As in the case of the glassware corrosion test, the test coolant was mixed with the corrosive water and aerated to accelerate the corrosion. The corrosive and erosive properties were simultaneously evaluated in terms of weight loss of the metal coupons and erosion of coolant pump. At the end of the test period, the corrosion-inhibiting properties of the coolant were determined by measuring the weight losses of the test coupons and by visual examination of the coolant pump impeller for deposits, pitting and corrosion. The test results are given in Table 9.

Results of simulated service corrosion test for coolant-water (30:70).

| Coupons | Copper | Solder | Brass | Mild steel | Cast iron | Aluminum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (mg) | ||||||

| Maximum allowable weight loss for automotive coolants as per ASTM D3306/SAE specifications (mg) | 20 | 40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Base coolant | 2.167 | 7.333 | 2.333 | 5.667 | 2.167 | 7.167 |

| Base coolant+0.5% oxidized MWCNTs | 2.333 | 8.333 | 3.167 | 6.167 | 2.333 | 7.667 |

| Base coolant+0.5% Ag nanoparticles | 6.000 | 78.33 | 8.000 | 52.97 | 93.26 | 1272.1 |

| Base coolant+0.5% Al2O3 nanoparticles | 7.333 | 85.24 | 9.133 | 31.246 | 35.333 | 88.34 |

The tests are carried out with coolant-water (30:70) based test coolants. As the test is dynamic in nature, alumina nanoparticles caused erosion on the metal coupons, resulting in weight loss slightly above the specified values. The coolant dispersed with silver nanoparticles caused severe corrosion of the solder, cast iron, mild steel and aluminum metal coupons resulting in massive weight loss far above the specified values as shown in Figure 9. Although base coolants gave slightly lower weight losses compared with the coolant dispersed with MWCNTs, the difference in weight loss is very much negligible. As in the case of the glassware test, the weight loss is very much below the allowable limit to qualify as an automotive coolant. From the results, it can be concluded that with the dispersion of oxidized MWCNTs, there is no deterioration in the anti-corrosive properties.

Metal coupons after the simulated service corrosion using the silver nanofluid.

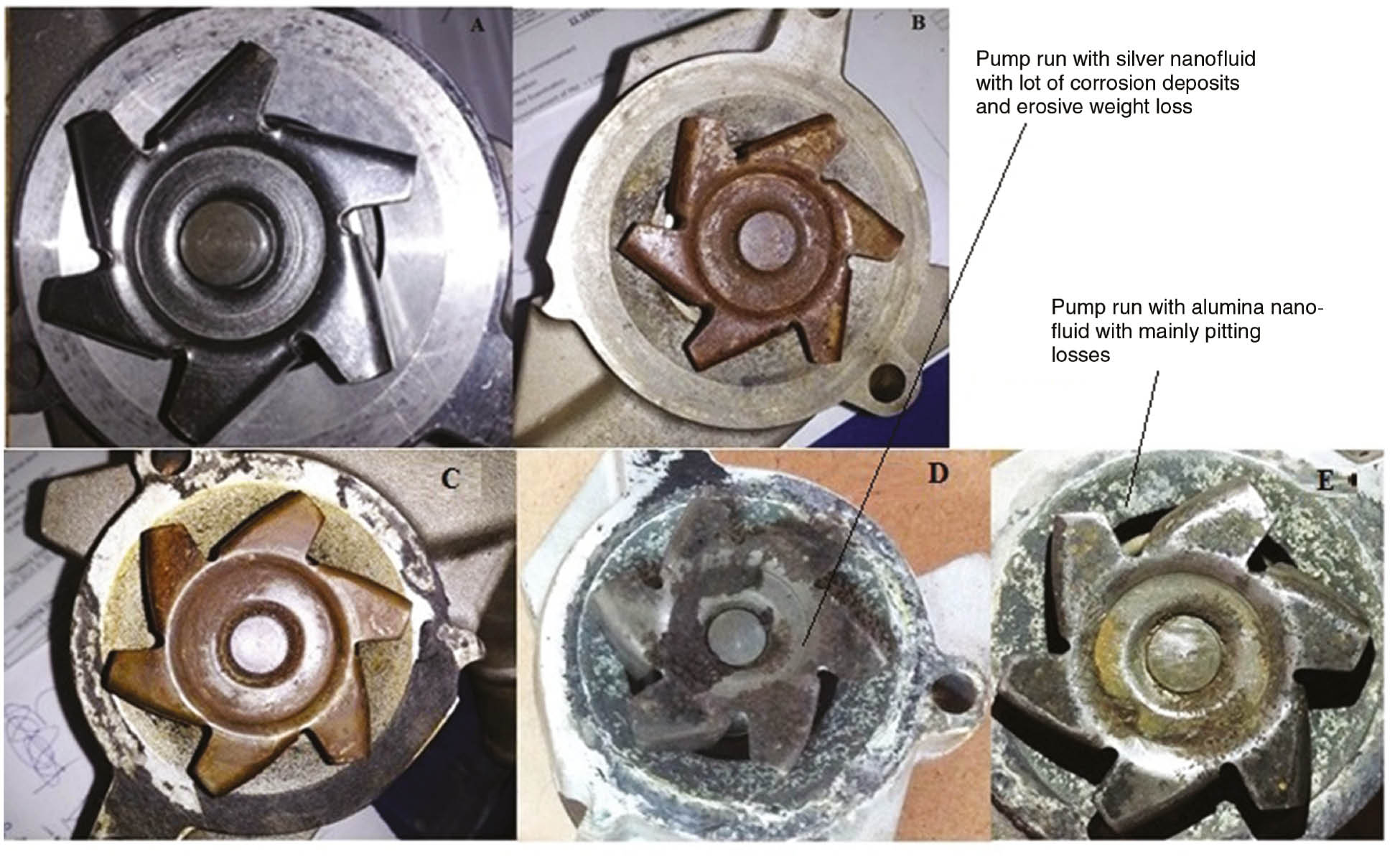

After termination of the test, the coolant pump is disassembled, and the interior surfaces of the impeller are inspected for erosion. Figure 10 shows the photographs of the pristine pump, the pump tested with base coolant and the pump tested with base coolant dispersed with nanomaterials. Figure 10A shows the impeller of the pristine pump that is made of aluminum prior to mounting on the test rig with perfectly smooth surface finish on the vanes. Figure 10B and C show the pump with base coolant and the pump run with coolant dispersed with MWCNTs, respectively. Figure 10D and E show the pumps run with silver and alumina nanofluids, respectively. The silver nanofluid exhibited the highest corrosion among all nanomaterials with alumina nanofluid, giving moderate erosive corrosion.

Photographs of the pump (A), the pristine aluminum pump, (B) the pump run with the base coolant, (C) the pump run with MWCNT-based coolant, (D) the pump run with silver nanofluid and (E) the pump run with alumina nanofluid.

From the studies, it can be concluded that although the nanomaterials possess heat transfer enhancement properties, care should be taken in selecting the nanoparticles in view that silver and alumina nanoparticles are corrosive and erosive in nature. However, from the studies, it can be observed that MWCNTs because of their inert nature did not affect the corrosive and erosive properties. The weight loss of the metal specimens in all the tests with nanofluids containing MWCNTs is more or less similar to that of the base coolant and is well within the prescribed range suggested by the ASTM D3306 standard, making it a good choice as additive to commercial coolants.

4 Conclusions

The following conclusions are arrived at from the studies made:

Oxidation of MWCNTs and surface modification of silver and alumina nanoparticles resulted in good and stable dispersion of nanofluids.

The zeta potential analysis shows that the fluid stability is intact even after 2 months.

The corrosion and erosion characteristics of the coolant dispersed with MWCNTs are within the acceptable range as specified in ASTM D3306. The coolant dispersed with silver nanoparticles failed in the corrosion test, whereas the coolant with aluminum nanoparticles did not pass in the erosion test.

The glassware corrosion test results indicate that the coolant with MWCNTs could resist corrosion on par with the base coolant. The silver nanofluid severely corroded the aluminum metal coupon with the alumina nanofluid displaying optimum performance.

In the cavitation corrosion test, the alumina nanofluid displayed severe pitting corrosion with higher mass erosion rates. The MWCNT and silver nanofluid based coolants demonstrated promising performance.

In the simulated service corrosion test, the coolant dispersed with MWCNTs displayed performance similar to that of the base coolant in resisting corrosion and erosion. The silver nanofluid rigorously corroded the metal coupons as well as the coolant pump. The coolant dispersed with alumina nanoparticles to some extent resisted corrosion of the metal coupons but, owing to their abrasive nature, pitted the pump causing erosion.

Among all the nanomaterials tested, the coolants dispersed with oxidized MWCNT displayed good anti-corrosive and anti-erosive properties, making them promising additives in automotive coolants.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support received from the Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd. for conducting the tests. The authors thank the Management of GITAM University for their constant support. The authors acknowledge the assistance from ARCI, Hyderabad in the characterization.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare to have no conflict of interests.

References

Ailor WH. Engine coolant testing: state of the art, ASTM D 15 Committee. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 1980.10.1520/STP705-EBSearch in Google Scholar

Alimorad R, Azadeh A, Roghayeh L, Homan J, Hossein R, Ali RR, Abbas J. An investigation of electrochemical behavior of nanofluids containing MWCNT on the corrosion rate of carbon steel. Mater Res Bull 2013; 18: 4438–4443.Search in Google Scholar

Assael MJ, Chen CF, Metaxa IN, Wakeham WA. Thermal conductivity of suspensions of carbon nanotubes in water. Int J Thermophys 2004; 25: 971–985.10.1023/B:IJOT.0000038494.22494.04Search in Google Scholar

Assael MJ, Metaxa IN, Arvanitidis J, Christofilos D, Lioutas C. Thermal conductivity enhancement in aqueous suspensions of carbon multiwalled and double-walled nanotubes in the presence of two different dispersants. Int J Thermophys 2005; 26: 647–664.10.1007/s10765-005-5569-3Search in Google Scholar

ASTM D1384-05. Standard test method for corrosion test for engine coolants in glassware. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

ASTM D2570-16. Standard test method for simulated service corrosion testing of engine coolants. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

ASTM D 3306-03. Standard specification for glycol base engine coolant for automobile and light-duty service. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

ASTM G32-16. Standard test method for cavitation erosion using vibratory apparatus. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

Avilés F, Rodríguez JV, Tah LM, Pat AM, Coronado RV. Evaluation of mild acid oxidation treatments for MWCNT functionalization. Carbon 2009; 47: 2970–2975.10.1016/j.carbon.2009.06.044Search in Google Scholar

Baghalha M, Kamal-Ahmadi M. Brass corrosion in sodium dodecyl sulphate solutions and carbon nanotube nanofluids: a modified Koutecky-Levich equation to model the agitation effect. Corros Sci 2011; 53: 4241–4247.10.1016/j.corsci.2011.08.035Search in Google Scholar

Beal RE. Engine coolant testing: state of the art. ASTM D special technical publication. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 1984.Search in Google Scholar

Beal RE. Engine coolant testing, vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 1993.10.1520/STP1192-EBSearch in Google Scholar

Beal RE. Engine coolant testing, vol 4. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM, 1999.Search in Google Scholar

Celata GP, Annibale FD, Mariani A, Sau S, Serra E, Bubbico R, Menale C, Poth H. Experimental results of nanofluids flow effects on metal surfaces. Chem Eng Res Des 2014; 92: 1616–1628.10.1016/j.cherd.2013.12.003Search in Google Scholar

Choi SU, Zhang ZG, Yu W, Lockwood FE, Grulke EA. Anomalous thermal conductivity enhancement in nano-tube suspensions. Appl Phys Lett 2001; 79: 2252–2254.10.1063/1.1408272Search in Google Scholar

Das SK, Choi SU, Patel HE. Heat transfer in nanofluids – a review. Heat Transfer Eng 2006; 27: 3–19.10.1080/01457630600904593Search in Google Scholar

Eastman JA, Choi SU, Li S, Yu W, Thompson LJ. Anomalously increased effective thermal conductivities of ethylene glycol-based nanofluids containing copper nanoparticles. Appl Phys Lett 2001; 78: 718–720.10.1063/1.1341218Search in Google Scholar

Lee S, Choi SU. Application of metallic nanoparticle suspensions in advanced cooling systems. Atlanta, USA: International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exhibition, 1996.10.1115/IMECE1996-0161Search in Google Scholar

Lee S, Choi SU, Li S, Eastman JA. Measuring thermal conductivity of fluids containing oxide nanoparticles. J Heat Transfer 1999; 121: 280–289.10.1115/1.2825978Search in Google Scholar

Li Q, Xuan MY. Convective heat transfer and flow characteristics of Cu-water nanofluids. Sci China Ser E 2002; 45: 408–416.10.1360/02ye9047Search in Google Scholar

Liu MS, Lin MCC, Huang IT, Wang CC. Enhancement of thermal conductivity with carbon nanotube for nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass 2005; 32: 1202–1210.10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2005.05.005Search in Google Scholar

McGeehan JA. API: CI-4: The first oil category for diesel engines using cooled exhaust gas recirculation. SAE paper 2002.10.4271/2002-01-1673Search in Google Scholar

Rashidi AM, Amrollahi A, Lotfi R, Javaheryzadeh H, Rahimi AR, Jorsaraei A. An investigation of electrochemical behavior of nanofluids containing MWCNT on the corrosion rate of carbon steel. Mater Res Bull 2013a; 48: 4438–4443.10.1016/j.materresbull.2013.07.042Search in Google Scholar

Rashidi AM, Packnezhad M, Mohamadi-Ochmoushi MR, Moshrefi-Torbati M. Comparison of erosion, corrosion and erosion-corrosion of carbon steel in fluid containing micro- and nanosize particles. Tribology 2013b; 7: 114–121.10.1179/1751584X13Y.0000000039Search in Google Scholar

Rashidi AM, Packnezhad M, Moshrefi-Torbati M, Walsh FC. Erosion-corrosion synergism in an alumina/sea water nanofluids. Microfluid Nanofluidics 2014; 17: 225–232.10.1007/s10404-013-1282-xSearch in Google Scholar

Rashmi W, Ismail AF, Khalid M, Anuar A, Yusaf T. Investigating corrosion effects and heat transfer enhancement in smaller size radiators using CNT-nanofluids. J Mater Sci 2014; 49: 4544–4551.10.1007/s10853-014-8154-ySearch in Google Scholar

Routbort J, Singh D, Timofeeva E, Yu W, Smith R. Erosion of radiator materials by nanofluids. Argonne National Laboratory, Vehicle Technologies – Annual Review 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Singh D, Routbort J, Sofu T, Smith R. Erosion of radiator materials by nanofluids. Vehicle Technologies – Annual Review 2009: 18–22.Search in Google Scholar

Srinivas V, Moorthy ChVKNSN, Dedeepya V, Manikanta PV, Satish V. Nanofluids with CNTs for automotive applications. Heat Mass Transfer 2016; 52: 701–712.10.1007/s00231-015-1588-1Search in Google Scholar

Wang XQ, Mujumdar AS. Heat transfer characteristics of nanofluids: a review. Int J Thermal Sci 2007; 46: 1–19.10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2006.06.010Search in Google Scholar

Wang XQ, Mujumdar AS. A review on nano fluids – part II: experiments and applications. Braz J Chem Eng 2008; 25: 631–648.10.1590/S0104-66322008000400002Search in Google Scholar

Xue CH, Zhou RJ, Shi MM, Gao Y, Wu G, Zhang XB. The preparation of highly water-soluble multi-walled carbon nanotubes by irreversible noncovalent functionalization with a pyrene-carrying polymer. Nanotechnology 2008; 19: 215604.10.1088/0957-4484/19/21/215604Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yang D, Zhang X, Wang C, Tang Y, Li J, Hu J. Preparation of water-soluble multi-walled carbon nanotubes by Ce(IV)-induced redox radical polymerization. Pro Nat Sci 2009; 19: 991–996.10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.10.010Search in Google Scholar

Yang L, Du K, Zhang XS, Cheng B. Preparation and stability of Al2O3 nano-particle suspension of ammonia-water solution. Appl Therm Eng 2011; 31: 3643–3647.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2010.11.031Search in Google Scholar

Zhang H, Li HX, Cheng HM. Water-soluble multiwalled carbon nanotubes functionalized with sulfonated polyaniline. J Phys Chem B 2006; 110: 9095–9099.10.1021/jp060193ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Review

- Supramolecular concepts and approaches in corrosion and biofouling prevention

- Mini review

- Sulfate-reducing bacteria-assisted cracking

- Original articles

- Corrosion characteristics of an automotive coolant formulation dispersed with nanomaterials

- Pitting corrosion and effect of Euphorbia echinus extract on the corrosion behavior of AISI 321 stainless steel in chlorinated acid

- Study on interference and protection of pipeline due to high-voltage direct current electrode

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Review

- Supramolecular concepts and approaches in corrosion and biofouling prevention

- Mini review

- Sulfate-reducing bacteria-assisted cracking

- Original articles

- Corrosion characteristics of an automotive coolant formulation dispersed with nanomaterials

- Pitting corrosion and effect of Euphorbia echinus extract on the corrosion behavior of AISI 321 stainless steel in chlorinated acid

- Study on interference and protection of pipeline due to high-voltage direct current electrode