Abstract

Cyclic corrosion, consisting of carburization in Ar+4% CH4+3% H2 for 1 h and oxidation in air for 1 h, of Ni-base in a wrought alloy, Hastelloy-X, was investigated at 1000°C to understand the significant metal loss occurring in fuel injection nozzles of gas turbine combustor operated using natural gas. The mass gain of cyclic corrosion was relatively low up to about eight cycles of corrosion by formation of a Cr2O3 scale in each oxidation stage, but it increased rapidly due to formation of a Fe- and Ni-rich oxide scale as the number of corrosion cycles increases. The Cr content in the subsurface region rapidly decreased under the cyclic corrosion condition compared with a continuous single oxidation or carburization, which resulted in the formation of non-protective Fe- and Ni-rich oxide scale in a small number of corrosion cycles. The formation of a Cr3C2 scale from the protective Cr2O3 scale in the carburization stage was detrimental for the oxidation resistance of Hastelloy-X and was considered to have a similar effect to spallation of a Cr2O3 scale; therefore, it accelerated Cr consumption from the alloy subsurface region.

1 Introduction

The Ni-based wrought alloy Hastelloy-X has good high-temperature oxidation and corrosion resistance and is widely used as a high-temperature material for gas-turbine components such as liner of gas-turbine combustors and various hot sections of chemical plants. The high-temperature oxidation and/or corrosion resistance of this alloy are provided by the formation of a protective Cr2O3 scale (Rhee & Spencer, 1970; Angerman, 1972; England & Virkar, 1999), and the ability of Cr2O3 scale formation is achieved by alloy Cr content of about 22 wt%. A Cr2O3 scale is widely used to protect commercial heat-resistant alloys from high-temperature oxidation and corrosion environments, because Cr2O3 is one of the stable protective oxides up to relatively high temperature of about 1000°C in oxidizing atmospheres. However, the thermodynamic stability of Cr2O3 is inferior to that of Al2O3. Therefore, the protectiveness of the Cr2O3 scale is limited at higher temperatures in reducing atmospheres such as boilers and combustors of a gas turbine under fuel-rich combustion conditions. Moreover, materials used for combustors of industrial gas turbines are frequently exposed in high-carbon-activity atmospheres, because the fuel used in gas turbines is mostly carbonaceous gases such as methane and/or propane. Under the atmospheres containing sufficient carbon activity, Hastelloy-X alloy was known to be carburized and/or damaged by metal dusting (Muraoka et al., 1975; Hirano et al., 1981; Chin & Johanson, 1982; Wahl & Schmaderer, 1982; Lai, 1991).

In our previous study, we investigated the carburization behavior of Hastelloy-X in Ar-10% CH4 atmosphere at 1000°C to understand the mechanism of significant metal loss that occurs to a fuel injection nozzle installed in the gas turbine operated by natural gas after relatively shorter service time (Matsukawa et al., 2011). Although Hastelloy-X was carburized very quickly in this condition, thickness reduction of alloy substrate by carburization was not observed. Therefore, we concluded that significant metal loss could occur due to oxidation, which was accelerated by prior carburization, i.e. carburization reduces the oxidation resistance of Hastelloy-X. Changes in the atmosphere composition between carburization and oxidation in the actual operating environment during service were expected to be a main factor causing severe metal loss.

Cyclic oxidation was reported to be detrimental for the oxidation resistance of Hastelloy-X alloy. The Cr2O3 scale spalled off during cyclic exposure (Barrett & Lowell, 1975). However, the corrosion behavior of Hastelloy-X alloy under the carburization-oxidation cycle has not been evaluated so far. In this study, we investigate the corrosion behavior of Hastelloy-X at 1000°C under carburization-oxidation temperature cycling conditions.

2 Materials and methods

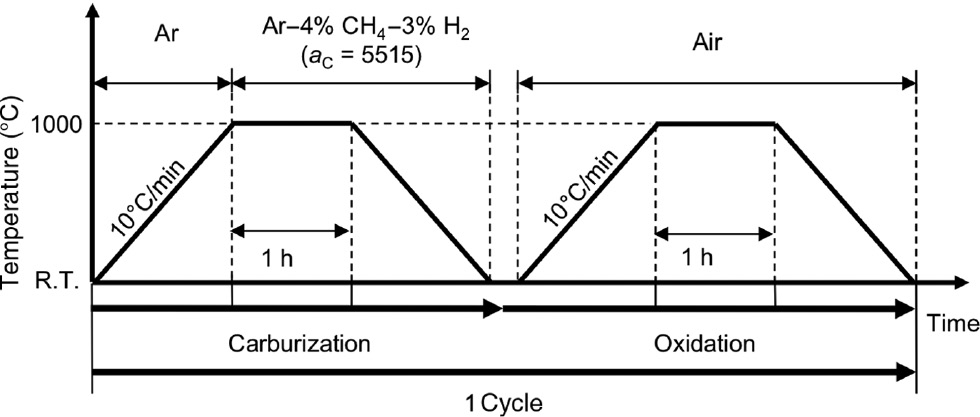

Corrosion samples with 20×10×1.2 mm3 (length, width, thickness) were cut from a wrought Hastelloy-X sheet. The surface of the sample was finished with 1200-grit SiC paper, followed by ultrasonic cleaning in acetone before the cyclic carburization-oxidation test. The composition of the Hastelloy-X alloy is shown in Table 1. The cyclic carburization-oxidation test consisted of Ar+4% CH4+3% H2 (ac=5515 at 1000°C) for 1 h and air for 1 h, as shown in Figure 1. In this study, we defined these carburization and oxidation cycles as one full cycle of corrosion. Carburization and oxidation exposures were carried out in the carburization equipment, which is illustrated in Figure 2, and a conventional box-type furnace, respectively.

Nominal composition of Hastelloy-X (in wt%).

| Ni | Cr | Fe | Mo | Co | W | C | Mn | B | Si | Nb | Al | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bal. | 22 | 18 | 9 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | <1 | <0.008 | <1 | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.15 |

Definition of one cycle of corrosion in the present study.

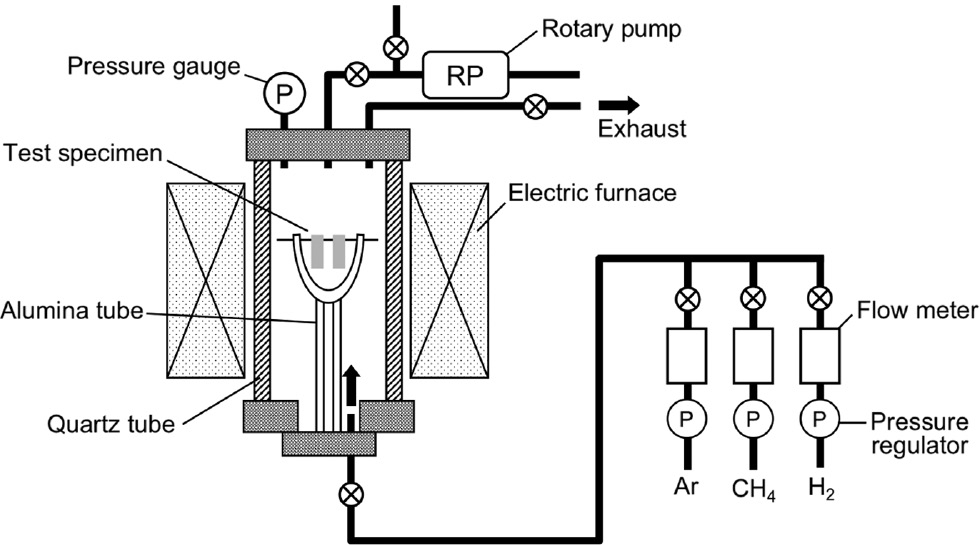

Schematic illustration of the equipment used for carburization (Matsukawa et al., 2011).

In the carburization stage, the test specimen was set in the carburization furnace hot zone with an alumina crucible, which was placed on top of an alumina stage. In this setup, the Ar or reaction gases were supplied from the bottom of the quartz reaction tube. The reaction tube was flushed with Ar gas several times before the carburization stage. Then, the sample was heated at a rate of 10°C/min until 1000°C, with flowing Ar gas stream, at a flow rate of 200 cm3/min. When the furnace temperature reached 1000°C, the gas supply was changed to an Ar+4% CH4+3% H2 mixture with a flow rate of 150 cm3/min. After the carburization step, the specimen was furnace cooled in the carburization gas stream with a flow rate of 50 cm3/min. In the oxidation stage, the sample was placed in a box-type furnace and heated at the same heating rate of 10°C/min until 1000°C in laboratory air. After oxidation for 1 h, the sample was furnace cooled to room temperature.

The surfaces and cross-sectional microstructures of the specimens were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical microscopy (OM). Murakami’s reagent, which contains 1.78 mol KOH and 0.304 mol K3[Fe(CN)6] per liter, was used for selective carbide etching of the cross sections. An electron probe micro-analyzer (EPMA) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were used to determine the distribution of the elements and identify the structures of the reaction products.

3 Results

3.1 Corrosion kinetics

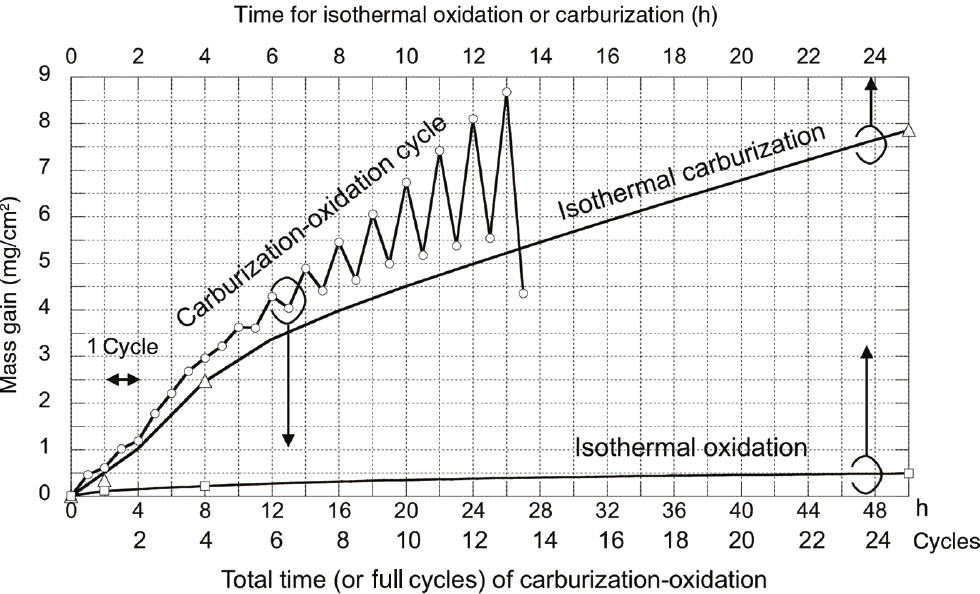

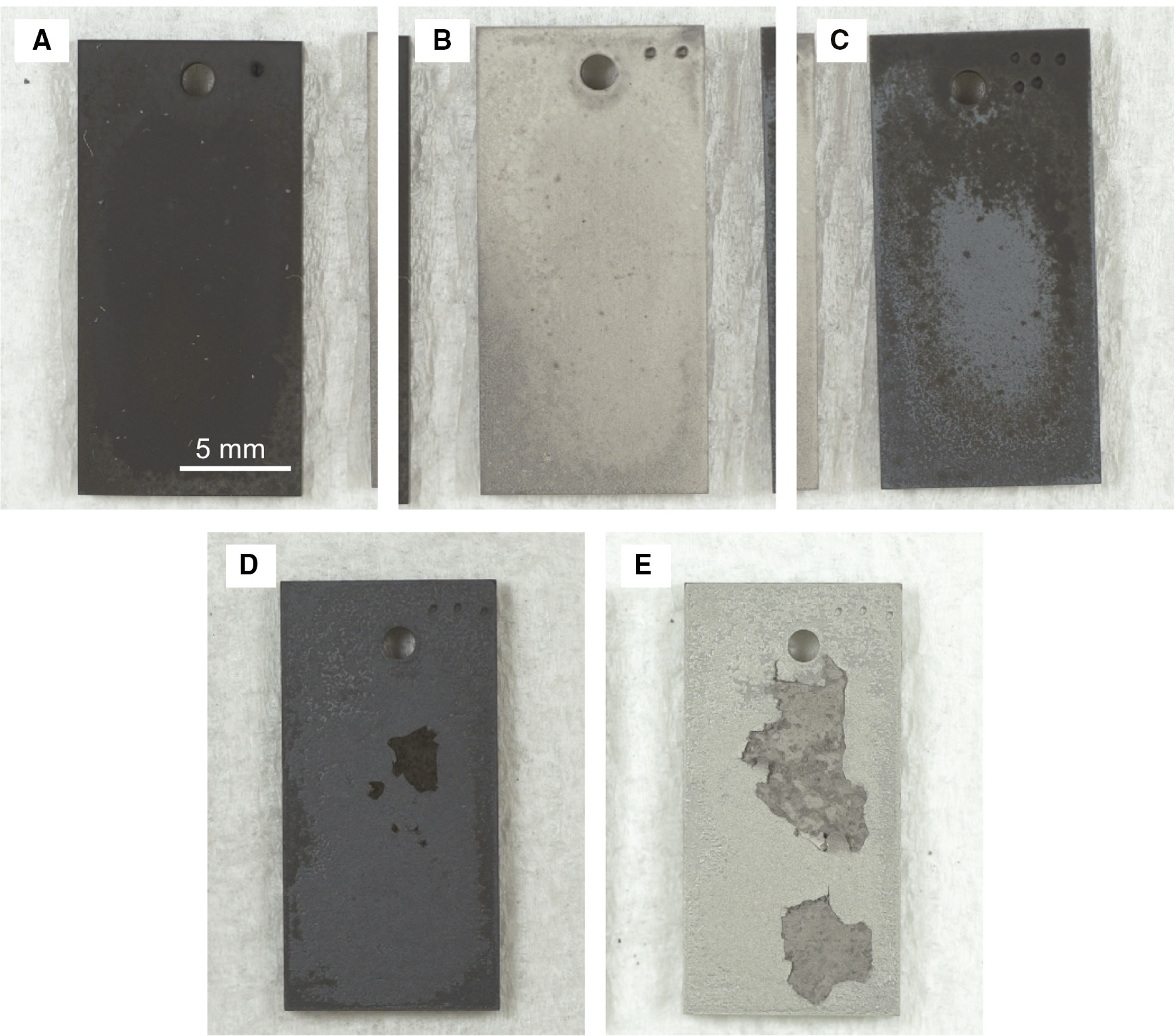

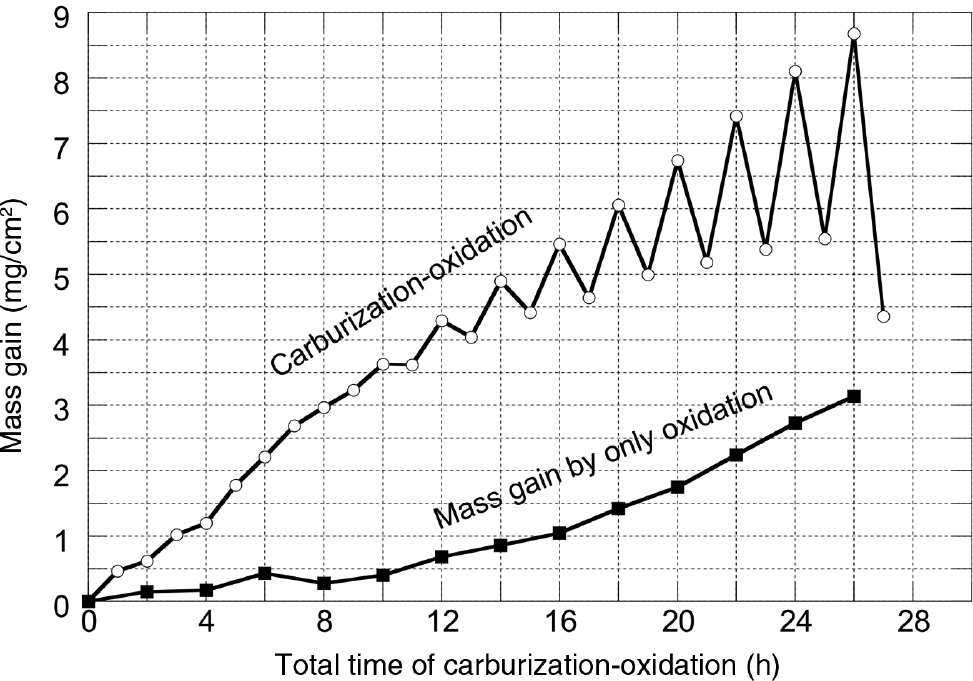

Figure 3 shows the corrosion kinetics of Hastelloy-X during the cyclic corrosion test. In Figure 3, the kinetics of continuous oxidation in air and carburization in Ar+4% CH4+3% H2 are also plotted for comparison. During initial corrosion, up to four cycles (total 8 h of carburization- oxidation), the mass gain in carburization stage was higher than that in oxidation stage. However, in the longer corrosion cycles, mass loss was observed by carburization and significant mass gain occurred in oxidation stage. The amount of both the mass loss and mass gain in the carburization and oxidation stages increased significantly at longer exposure times. Finally, large area of spallation of the corrosion product was found to occur at 13 cycles of corrosion, as shown in Figure 4. The mass gain after oxidation stage under the cyclic corrosion test was much higher than that of isothermal oxidation; however, the mass gain after the carburization stage in each cycle of corrosion was similar to that of a continuous carburization. This corrosion kinetics suggested that carburization accelerated the rate of oxidation.

Mass gain per unit area of the specimen during the carburization-oxidation cyclic test at 1000°C. Isothermal oxidation and carburization are shown for comparison. In this plot, the time for isothermal exposure is expressed as a half of the total time of the carburization-oxidation cycles to compare the mass gains during the time corresponding only to oxidation or carburization in the carburization-oxidation test.

Surface appearance of samples after different time (cycles) of the carburization-oxidation cycle test at 1000°C. (A) 6 (3 cycles), (B) 7 (3.5 cycles), (C) 8 (4 cycles), (D) 26 (13 cycles) and (E) 27 (13.5 cycles) h.

3.2 Surface and cross-sectional microstructure

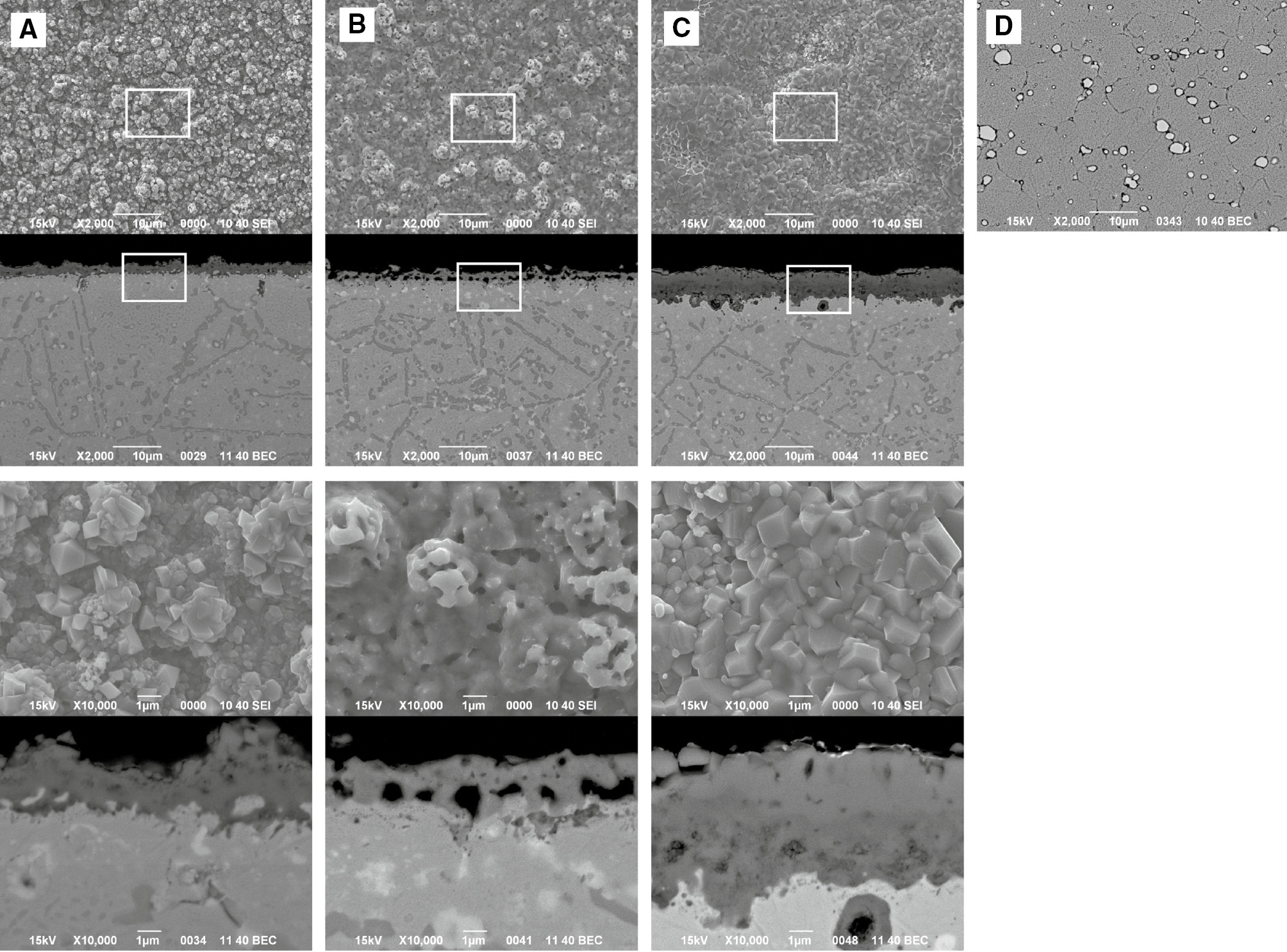

Figures 5 and 6 show the surface morphologies and cross sections and EPMA profiles of the samples after 3, 3.5 and 4 cycles of corrosion. These cycles correspond to the cycles that the corrosion behavior switched from protective to less protective manner, i.e. the mass gain in carburization stage changed to mass loss and the mass gain in the oxidation stage rapidly increased. There are mainly two different types of carbides that precipitated in the substrate: dark and bright. Among those carbides, bright-contrast precipitates have already precipitated in the as-received Hastelloy-X substrate, as shown in Figure 5D, and those are M6C (M is rich in Mo) carbide (Zhao et al., 2000). Dark contrast carbides were formed by carburization and mainly precipitated along the grain boundaries. Fine-sized carbides were also confirmed to form in grain interior. As shown in Figure 5A, the internal carburization zone developed in the substrate after three full cycles of carburization-oxidation, and those internal precipitates remained even after oxidation for 1 h. A continuous Cr2O3 scale was also observed to form on the surface (Figures 5A and 6A). Below a Cr2O3 scale, about 3 μm of internal carbide-free zone was formed.

Surface morphologies and cross sections of samples after different time (cycles) of the carburization-oxidation cycle test at 1000°C. (A) 6 (3 cycles), (B) 7 (3.5 cycles), (C) 8 (4 cycles) h and (D) as-received substrate (etched).

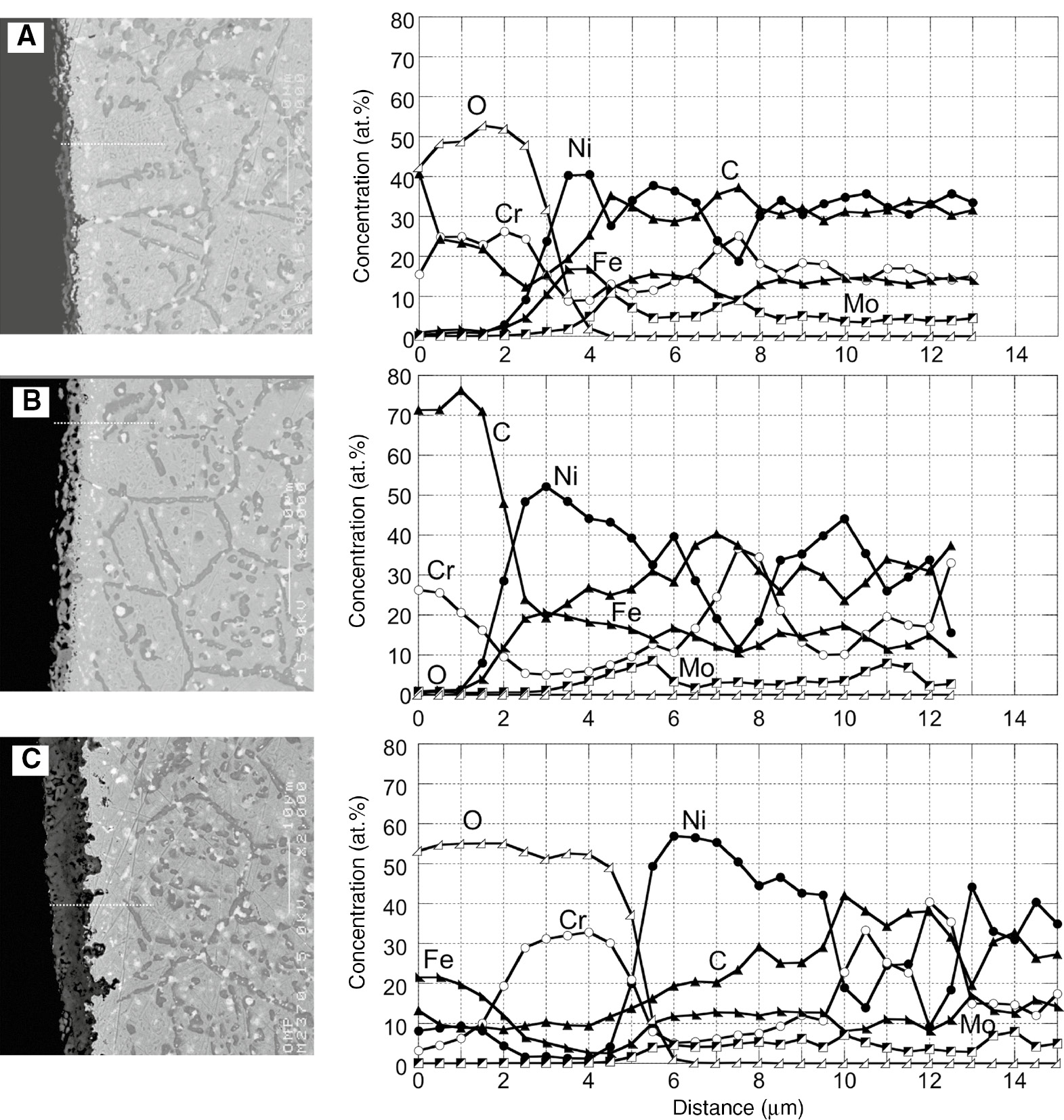

Cross sections of samples and concentration profiles of each element along the lines indicated in the cross sections after different time (cycles) of carburization-oxidation cycle test at 1000°C. (A) 6 (3 cycles), (B) 7 (3.5 cycles) and (C) 8 (4 cycles) h.

After 3.5 cycles of corrosion (after a carburization stage), a carbide scale that contains many voids and cavities was formed. The thickness of the carbide scale was thinner than that of the Cr2O3 scale (Figure 5B). X-ray diffraction and EPMA analysis revealed that this carbide scale was Cr3C2, indicating that the Cr2O3 scale, which was formed after three cycles, was converted to Cr3C2 during the carburization stage. After four cycles of corrosion, the oxide scale became much thicker and was duplex with the outer Fe- and Ni-rich and inner Cr-rich oxide layers, as shown in Figures 5C and 6C. The number of fine carbide precipitates in the grain interior of the substrate decreased and the size of precipitates tended to be larger. However, no apparent changes in the size and volume of the internal carbides formed along the grain boundaries were observed.

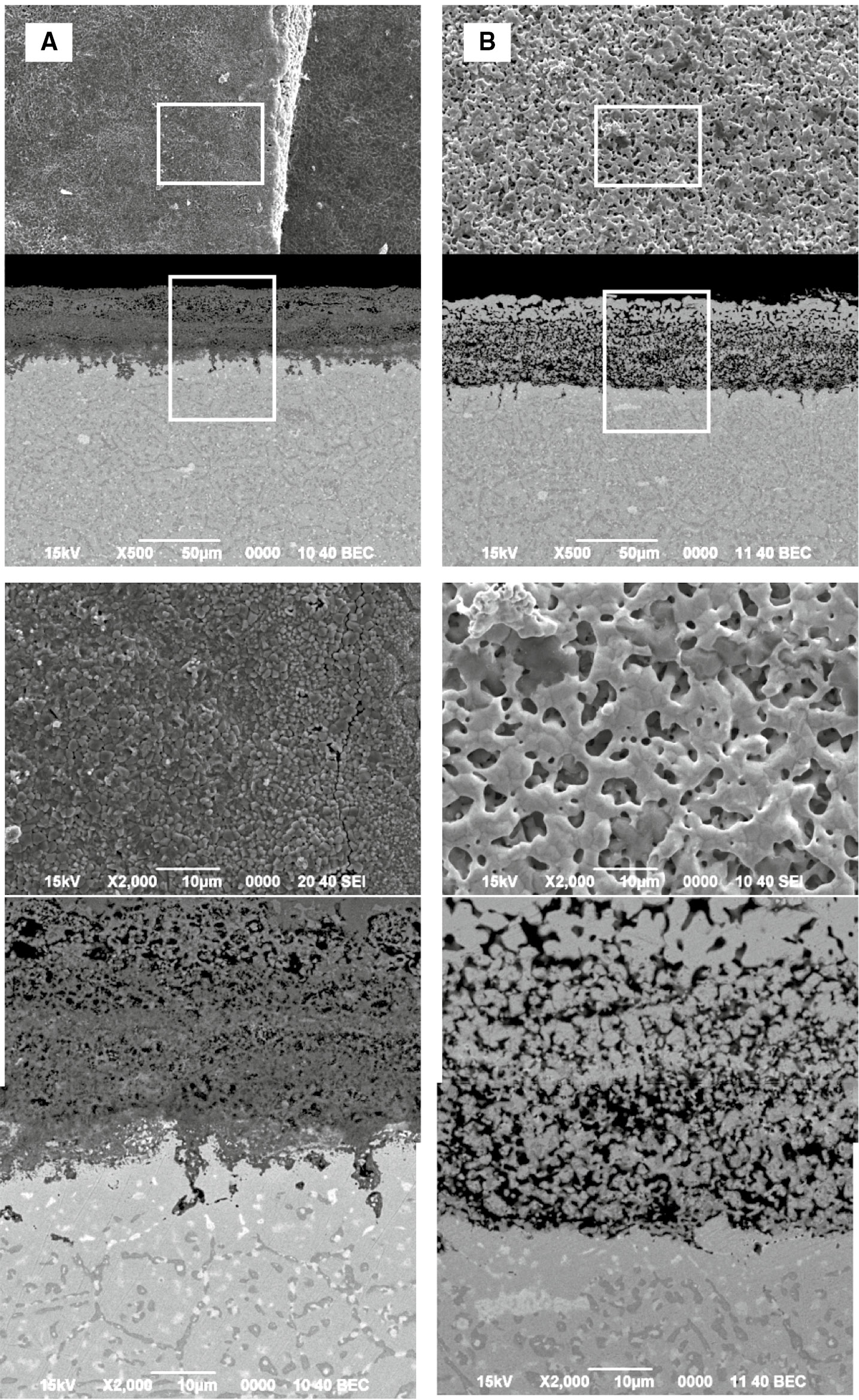

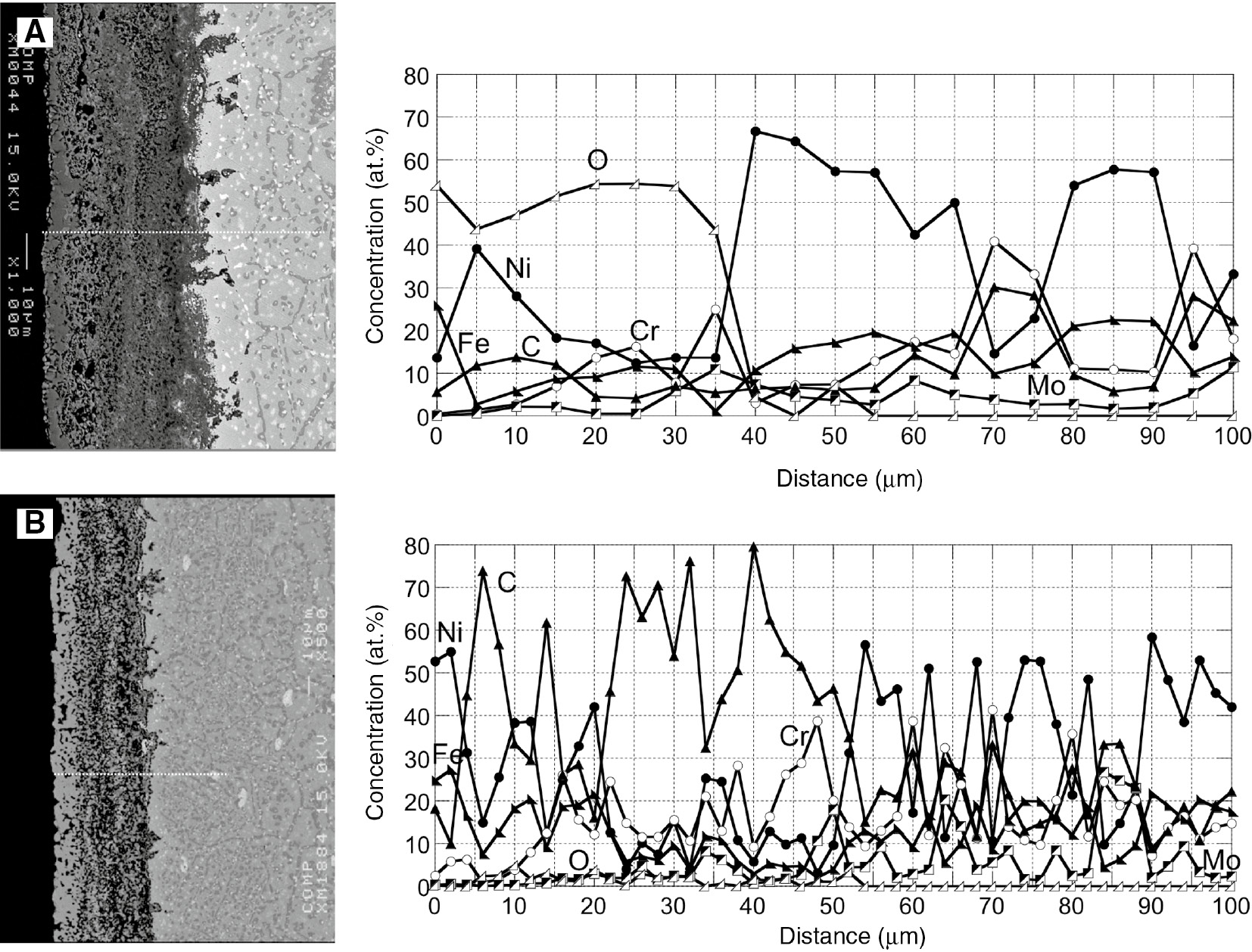

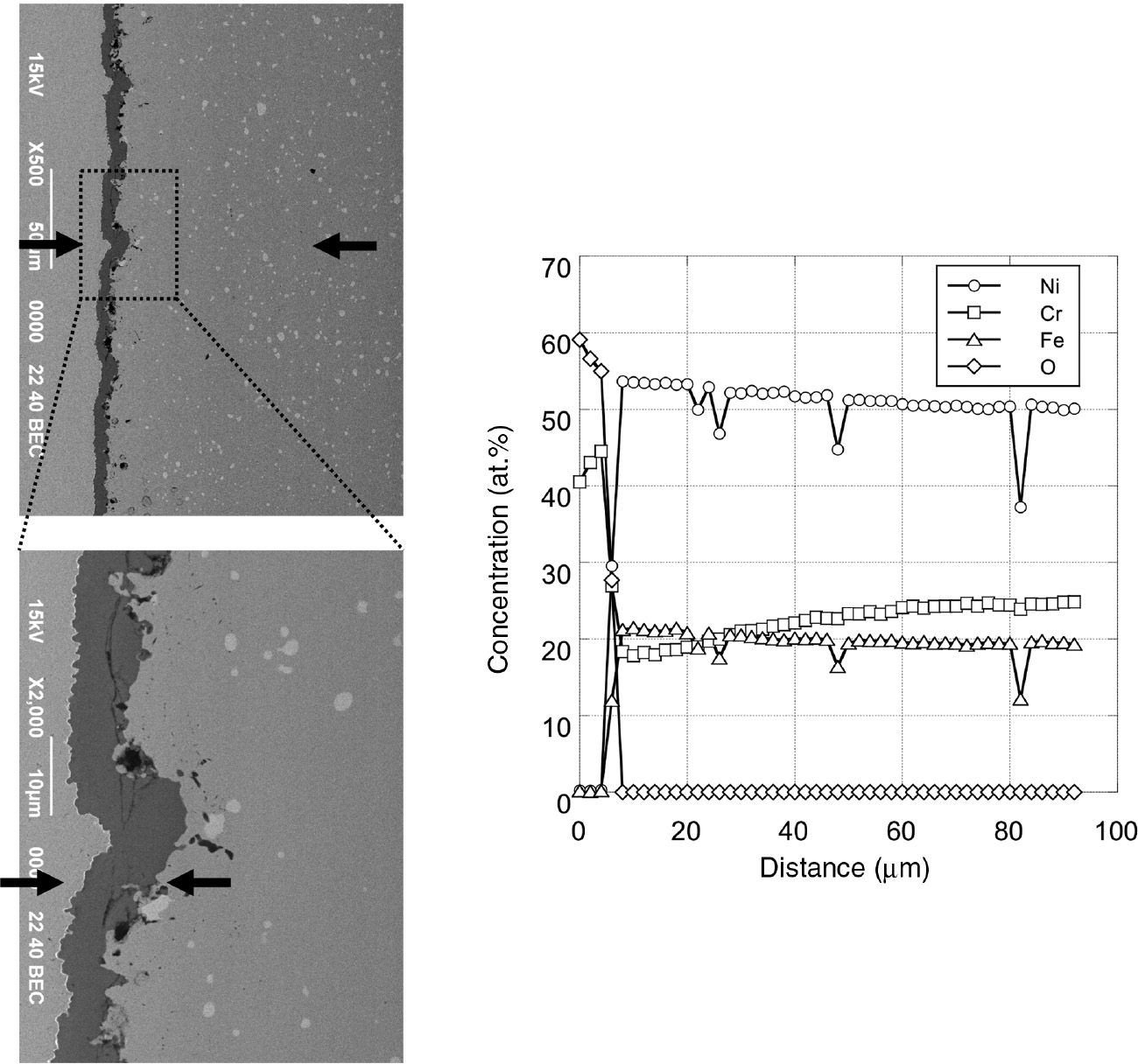

Figures 7 and 8 show the surface morphologies and cross sections and EPMA profiles of the samples after 13 and 13.5 cycles (total 26 and 27 h) of corrosion. The oxide scale grew significantly thicker, ~50 μm, and it was very porous. EPMA analysis indicated that the outer part of the oxide scale was rich in Ni and Fe, and the inner part was rich in Cr after 13 cycles of corrosion. After the carburization stage, 13.5 cycles of corrosion, both the outer and inner layers were still very porous and the outer Ni and Fe-rich oxide scale reduced to a metallic Fe-Ni phase and the inner Cr-rich oxide changed to a Cr-carbide.

Surface morphologies and cross sections of samples after different time (cycles) of carburization-oxidation cycle test at 1000°C. (A) 26 (13 cycles) and (B) 27 (13.5 cycles) h.

Cross sections and concentration profiles of each element along the lines indicated in the cross sections after different time (cycles) of carburization-oxdation cycle test at 1000°C. (A) 26 h (13 cycles) and (B) 27 h (13.5 cycles).

4 Discussion

4.1 Effect of carburization on oxidation of Hastelloy-X

Gan (1983) reported the effect of carburization on the oxidation of Hastelloy-X at 1000°C. He used specimens that were carburized in He-1% CH4 at 1000°C for 72 h. The pre-carburized specimen with an internal M23C6-type precipitate zone with a depth of about 800 μm was oxidized in air. Although the Cr-depleted zone developed due to internal carburization, pre-carburization has little effect on the oxidation and Gan concluded that Cr was released from M23C6-type carbide to provide protection. In the present study, however, Hastelloy-X was rapidly oxidized under the cyclic carburization-oxidation condition. Although no apparent effect of oxidation on the carburization of alloy was observed, carburization strongly affected the oxidation behavior of Hastelloy-X.

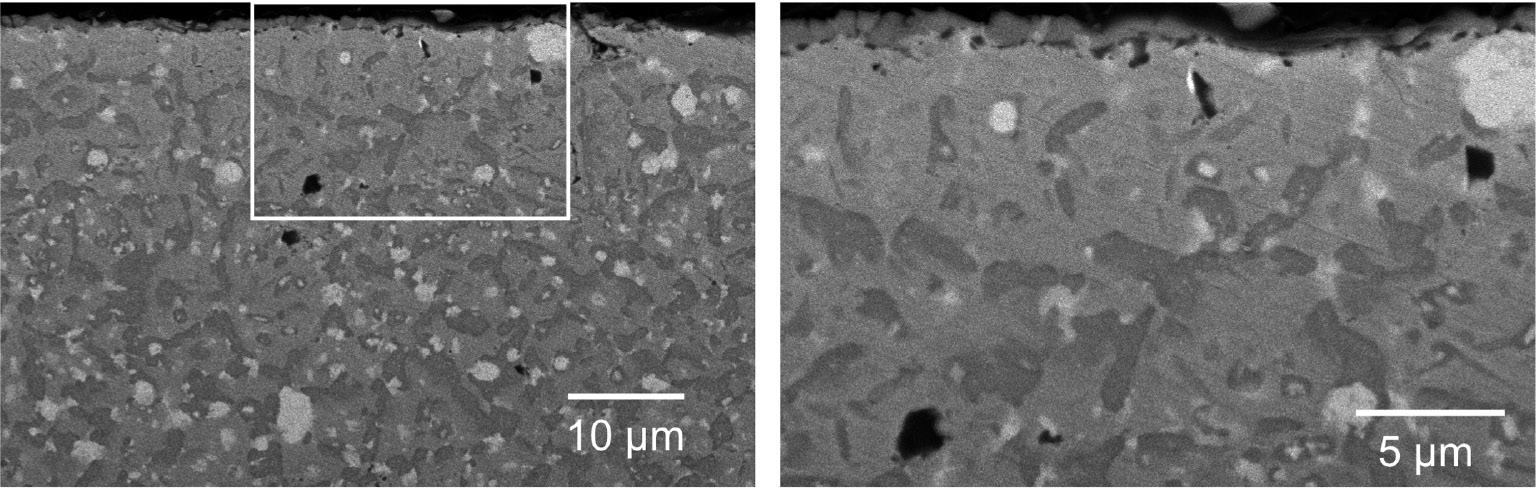

Because the mass gain after the carburization stage in the cyclic condition was similar to that of the continuous carburization, as shown in Figure 3, and microstructures of the alloy after 3.5 cycle of corrosion (total 4 h of carburization) and 4 h of continuous singly carburization (Matsukawa et al., 2011) are similar (Figures 9 and 5B), the mass gain after the carburization stage is mainly caused by carbon incorporation into the alloy substrate as solute and in the form of internal carbides. Apparently, the external Cr2O3 scale did not act as a protective oxide scale during carburization. Therefore, the effect of oxide scale formation on the mass gain by carburization can be neglected. Thus, the mass gain by the oxidation in the cyclic corrosion condition can be calculated by the following equation.

Cross section of Hastelloy-X after 4 h of continuous carburization at 1000°C (Matsukawa et al., 2011).

where ΔWtotal is the total mass gain measured after each oxidation and carburization stage. ΔWoxidation and ΔWcarburizaition are the mass gain of the alloy by oxidation and carburization under the cyclic condition, respectively. Figure 10 shows ΔWoxidation as a function of corrosion time in a cyclic condition. During the initial corrosion, up to 8 h, ΔWoxidation is similar to the oxidation mass gain when Hastelloy-X was oxidized continuously; however, it rapidly increased with further corrosion and became much greater than that of the oxidation mass gain of Hastelloy-X. As shown in Figure 3, Hastelloy-X showed very good high temperature oxidation resistance in air at 1000°C; therefore, the rapid increase in the oxidation-related mass gain by oxidation in cyclic carburization-oxidation condition was apparently caused by periodic carburization.

Calculated mass gain of Hastelloy-X by oxidation in the carburization-oxidation cycles at 1000°C.

During the carburization, carbon penetrated into the alloy substrate and formed carbide precipitates by consuming Cr in the substrate. Different from the result obtained by Gan, a sufficient Cr supply from the Cr carbide precipitates was not observed in this study. Therefore, the Cr level in the internal carburization zone decreased and finally reached a critical value necessary for the material to form a protective Cr2O3 scale, and Fe and Ni should start to oxidized. Moreover, the Cr3C2 scale formed after carburization also did not act as a source for a protective Cr2O3 scale in the oxidation stage.

4.2 Effect of the Cr3C2 scale and internal carbides on the oxidation behavior of Hastelloy-X

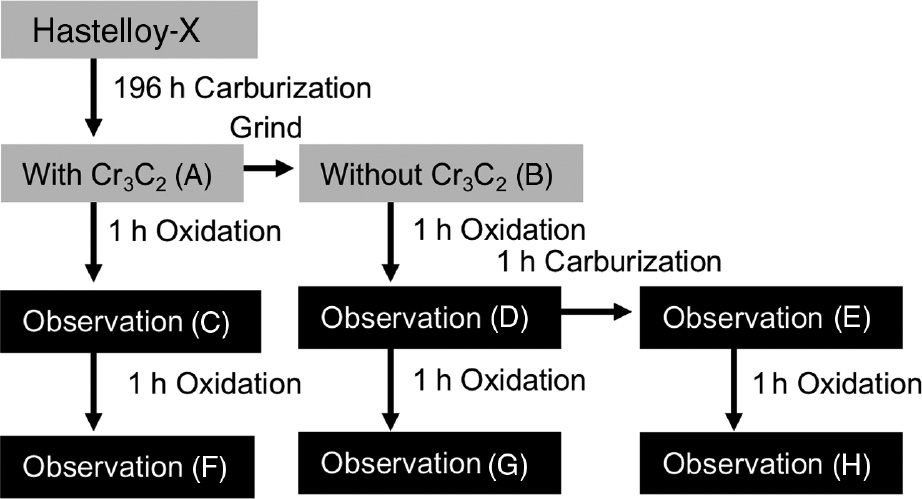

To clarify the effect of Cr3C2 scale and internal carbides formed during the carburization stage on oxidation behavior, an additional experiment was conducted. The detailed experimental condition is illustrated in Figure 11. In this experiment, a Hastelloy-X coupon was initially carburized in Ar+4% CH4+3% H2 for 196 h. After the carburization for 196 h, the continuous Cr3C2 scale developed on the surface and the internal carbide zone consisted of mainly Cr3C2 penetrating almost into the center of the sample, as shown in Figure 12A. A large void formation in the subsurface region below the Cr3C2 scale was also confirmed. After the carburization, the Cr3C2 scale and subsurface region containing large voids formed on one of the carburized coupons was removed by 1200-grit SiC paper. Then, the alloy coupons with different surface conditions, one with the Cr3C2 scale and the other without carbide scale, were oxidized at 1000°C in air for two cycles of oxidation for 1 h. The sample whose surface scale was removed was also carburized again for 1 h after 1 h of oxidation cycle, followed by an additional oxidation cycle for 1 h in air.

Flowchart of the experiment to investigate the effect of Cr3C2 scale on oxidation at 1000°C.

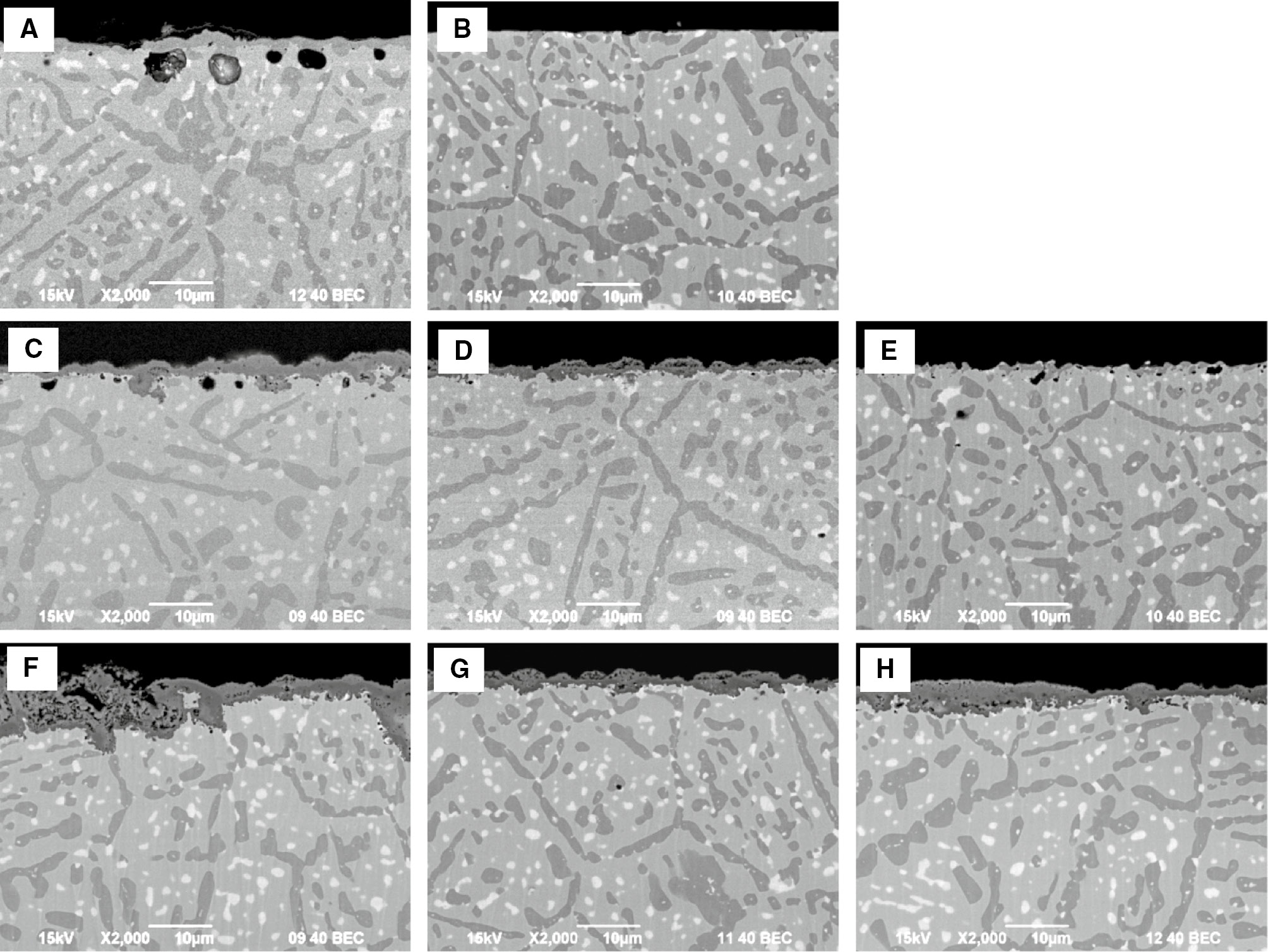

Cross sections of surface products of samples after each test indicated in Figure 11. (A) Carburization for 196 h, (B) after removal surface carbide scale on sample (A), (C) oxidation of sample (A) for 1 h, (D) oxidation of sample (B) for 1 h, (E) carburization of sample (D) for 1 h, (F) oxidation of sample (A) for 2 h, (G) oxidation of sample (B) for 2 h and (H) oxidation of sample (E) for 1 h.

Figure 12 shows the cross sections after each oxidation and/or carburization cycle of the experiment descried in Figure 11. The oxide scale formed on the sample with the Cr3C2 scale after 1 h of oxidation was thicker than that formed on the sample without the carbide scale (Figure 12C, D). The oxide scale formed on the sample without surface Cr3C2 was still thinner after 2 h of oxidation cycles compared with the oxide scale formed on the sample with Cr3C2 scale, which became significantly thicker after total 2 h of oxidation cycles (Figure 12F, G). This detrimental effect of the Cr3C2 scale on oxidation was also confirmed by a thick oxide scale formation on the sample which was carburized between the 1-h oxidation cycles (Figure 12E, H). The thickness of the oxide scale formed on the sample with carburization in between the oxidation cycles was similar to that of the oxide scale formed on the sample with the Cr3C2 scale after 1 h of oxidation. These results clearly indicate that formation of a Cr3C2 scale is more detrimental for the alloy resistance than formation of internal carbides.

4.3 Transition from protective to non-protective oxidation behavior of Hastelloy-X

The mass gain of Hastelloy-X by oxidation under cyclic corrosion was low with a protective Cr2O3 scale formation until four cycles of corrosion (Figure 5), but it rapidly increased during further corrosion cycles with a porous Fe-, Ni- and Cr-rich oxide scale formation (Figure 7). As shown in Figure 6, the Cr content in the subsurface region decreased to about 10 and 5 at% after only three and four carburization-oxidation cycles, respectively. These Cr contents in the subsurface region are much lower than the Cr content, ~18%, in the subsurface region below the protective Cr2O3 scale formed after 100 h of isothermal oxidation in the air, as shown in Figure 13. Such a large difference in Cr contents suggests that the cyclic carburization-oxidation condition accelerated the consumption of Cr, thereby promoting the development of a Cr-depleted zone. The critical Cr content for an external Cr2O3 scale formation on binary Ni-Cr at 1000°C was reported to be about 18% (Giggins & Pettit, 1969). Hastelloy-X contained various alloying elements such as Fe, Mo, Si, and so on. Among those elements, Si is known as a beneficial element for the oxidation resistance of Ni-based alloys (Douglass & Armijo, 1970; Li & Gleeson, 2006); therefore, the critical Cr content to form the Cr2O3 scale on Hastelloy-X could be lower than that of binary Ni-Cr alloy; however, 10 or 5 at% Cr is too low to establish an external Cr2O3 scale. Therefore, Fe- and Ni-rich oxide scales were developed on the alloy after only shorter corrosion cycles.

Cross sections and concentration profiles of each element after 100 h of isothermal oxidation in air at 1000°C.

As mentioned above, the formation of internal Cr-carbides is one of the reasons of Cr depletion in the substrate. Cr content in the subsurface region can be calculated by the ratio of the volume fraction of the internal carbide,

As shown in Figure 5B, the Cr3C2 scale formed by the carburization of the dense Cr2O3 scale shown in Figure 5C was porous and contained large voids near the scale/alloy interface. The formation of those large voids would be caused by volume reduction, 61.7%, and/or formation of gas species such as CO2, CO and H2O accompanied by carburization of a Cr2O3 scale. This porous Cr3C2 scale was oxidized again and formed a porous non-protective Cr2O3 scale in the oxidation stage. If the Cr content in the substrate is sufficiently high, a dense protective Cr2O3 scale can be formed below the “non-protective Cr2O3 scale”. This “protective Cr2O3” scale is then changed again to a “non-protective” scale when the sample was carburized and oxidized again in the next corrosion cycle. Repeating this procedure should result in higher Cr consumption, i.e. the carburization stage can be regarded as a spallation of a protective Cr2O3 scale. Periodic “reformation and spallation” of a Cr2O3 scale caused a rapid decrease in Cr content in the subsurface region. Once the Cr content decreased below the critical Cr content, then less protective thick Fe and/or Ni oxide scales formed in the oxidation stage. Those oxide scales were easily reduced to a very porous metallic phase during the carburization stage and oxidized rapidly in the oxidation stage, causing higher mass gain and loss during the corrosion cycles.

Based on the results obtained in this study, it is concluded that the significant metal loss that occurred to a fuel injection nozzle of an industrial gas turbine could be caused by periodic oxidation and carburization during the operation. The actual combusting environment in which nozzles were exposed during the service was considered to be very critical for Hastelloy-X. A protective coating, which forms a protective Al2O3 scale, is necessary to protect the alloy substrate or Al2O3 scale forming heat-resistant alloys should be used to extend the lifetime of this component. We are investigating the corrosion behavior of Al2O3-forming alloys in the oxidation-carburization cyclic condition. The results will be published elsewhere.

5 Conclusions

Cyclic oxidation-carburization of Hastelloy-X alloy at 1000°C in air and Ar+4% CH4+3% H2 gas was conducted. The results may be summarized as follows.

During the early stage of exposure, up to four cycles, Hastelloy-X formed a dense protective Cr2O3 scale in the oxidation stage. This Cr2O3 scale was reduced in the next carburization stage to form a porous Cr3C2 scale. Internal Cr-carbide precipitates were also developed mainly along the grain boundaries of the alloy substrate. This internal Cr-carbide formation resulted in a decrease in Cr content in the alloy substrate.

In the oxidation stage, the Cr3C2 scale oxidized to porous Cr2O3 scale. When the alloy contained sufficient Cr content, a protective Cr2O3 scale still formed below the porous Cr2O3. However, when Cr level decreased down to the critical level to form an external Cr2O3 scale, Fe and/or Ni started to oxidize.

Cr3C2 scale formation in the carburization stage accelerated the consumption of Cr and promoted Fe and/or Ni oxide formation. Cr3C2 scale formation was considered to have a similar effect on Cr consumption from the alloy as the spallation of a protective Cr2O3 scale. Periodic formation of Cr3C2 and Cr2O3 scales greatly decreases the oxidation resistance of Hastelloy-X.

References

Angerman CL. Long-term oxidation of superalloys. Oxid Met 1972; 5: 149–167.10.1007/BF00610842Search in Google Scholar

Barrett CA, Lowell CE. Comparison of isothermal and cyclic oxidation behavior of twenty-five commercial sheet alloys at 1150°C. Oxid Met 1975; 9: 307–355.10.1007/BF00613534Search in Google Scholar

Chin J, Johanson WR. Compatibility of aluminide-coated Hastelloy X and Inconel 617 in a simulated gas-cooled reactor environment. Thin Solid Films 1982; 95: 85–97.10.1016/0040-6090(82)90585-5Search in Google Scholar

Douglass DL, Armijo JS. The effect of silicon and manganese on the oxidation mechanism of Ni-20Cr. Oxid Met 1970; 2: 207–231.10.1007/BF00603657Search in Google Scholar

England DM, Virkar AV. Oxidation kinetics of some nickel-based superalloy foils and electronic resistance of the oxide scale formed in air part I. J Electrochem Soc 1999; 146: 3196–3202.10.1149/1.1392454Search in Google Scholar

Gan D. Oxidation of carburized Hastelloy X. Metall Trans A 1983; 14A: 1518–1521.10.1007/BF02664839Search in Google Scholar

Giggins CS, Pettit FS. Oxidation of Ni-Cr alloys between 800° and 1200°C. Trans Met Soc AIME 1969; 245: 2495–2507.10.1007/BF02811822Search in Google Scholar

Hirano T, Araki H, Yohida H. Carburization and decarburization of superalloys in the simulated HTGR helium. J Nucl Mater 1981; 97: 272–280.10.1016/0022-3115(81)90475-XSearch in Google Scholar

Lai GY. High-temperature corrosion: issues in alloy selection. JOM 1991; 43: 54–60.10.1007/BF03222722Search in Google Scholar

Li B, Gleeson B. Effects of silicon on the oxidation behavior of Ni-base chromia-forming alloys. Oxid Met 2006; 65: 101–122.10.1007/s11085-006-9003-4Search in Google Scholar

Matsukawa C, Hayashi S, Yakuwa H, Kishikawa T, Narita T, Ukai S. High-temperature carburization behavior of Hastelloy-X in CH4 gas. Corros Sci 2011; 53: 3131–3138.10.1016/j.corsci.2011.05.056Search in Google Scholar

Muraoka S, Itami H, Nomura S. Carburization of Hastelloy alloy X. J Nucl Mater 1975; 58: 18–24.10.1016/0022-3115(75)90161-0Search in Google Scholar

Rhee SK, Spencer AR. Oxidation of commercial high-temperature alloys. Metall Trans 1970; 1: 2021–2022.10.1007/BF02642810Search in Google Scholar

Wahl G, Schmaderer F. The use of silicon-enriched layers as a protection against carburization in high temperature gas-cooled reactors. Thin Solid Films 1982; 94: 257–268.10.1016/0040-6090(82)90302-9Search in Google Scholar

Zhao J-C, Larsen M, Ravikumar V. Phase precipitation and time-temperature-transformation diagram of Hastelloy X. Mater Sci Eng 2000; A293: 112–119.10.1016/S0921-5093(00)01049-2Search in Google Scholar

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Editorial

- Special issue on Recent advances in corrosion science: celebrating the 90th birthday of Professor Norio Sato

- Reviews

- Some microelectrochemical methods for the investigation of passivity and corrosion

- Inhibition effect of underpotential deposition of metallic cations on aqueous corrosion of metals

- Role of anodic oxide films in the corrosion of aluminum and its alloys

- Development of novel surface treatments for corrosion protection of aluminum: self-repairing coatings

- Mini review

- High-temperature corrosion resistance of SiO2-forming materials

- Original articles

- Cyclic carburization-oxidation behavior of Hastelloy-X at 1000°C

- Growth of passive oxide films on iron and titanium under non-stationary state

- Influence of metal cations on inhibitor performance of gluconates in the corrosion of mild steel in fresh water

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Editorial

- Special issue on Recent advances in corrosion science: celebrating the 90th birthday of Professor Norio Sato

- Reviews

- Some microelectrochemical methods for the investigation of passivity and corrosion

- Inhibition effect of underpotential deposition of metallic cations on aqueous corrosion of metals

- Role of anodic oxide films in the corrosion of aluminum and its alloys

- Development of novel surface treatments for corrosion protection of aluminum: self-repairing coatings

- Mini review

- High-temperature corrosion resistance of SiO2-forming materials

- Original articles

- Cyclic carburization-oxidation behavior of Hastelloy-X at 1000°C

- Growth of passive oxide films on iron and titanium under non-stationary state

- Influence of metal cations on inhibitor performance of gluconates in the corrosion of mild steel in fresh water