Abstract

Nowadays, core/shell structures due to very high thermal and electrical conductivity are taken into account in the manufacture of many industrial sensors and catalysis. Ni–Al core/shell structures are known as one of the most practical materials due to their high chemical stabilities at elevated temperatures. Since the evaluation of the mechanical properties of the industrial core/shell catalysts is crucial, identification of the mechanism responsible for their plastic deformation has been a challenging issue. Accordingly, in this study, the mechanical properties and plastic deformation process of Ni–Al core/shell structures were investigated using the molecular dynamics method. The results showed that due to the high-stress concentration in the Ni/Al interface, the crystalline defects including dislocations and stacking faults nucleate from this region. It was also observed that with increasing temperature, yield strength and elastic modulus of the samples decrease. On the other hand, increasing the temperature promotes the heat-activated mechanisms, which reduces the density of dislocations and stacking faults in the material. Consequently, the obstacles in the slip path of the dislocations as well as dislocation locks are reduced, weakening the mechanical properties of the samples.

1 Introduction

In light of high thermal and electrical conductivity, strength–weight ratio, Young’s modulus, and thermal stability, core–shell nanostructures have been of great interest in aerospace industries and stable chemical and medical catalysts in recent years [1]. To construct such nanostructures, a core is situated in a certain position, with the shell being deposited on the core [1]. The core–shell interface in such nanostructures is crucial, as with nanocomposites, since its strength strongly affects the properties of the nanostructure [2,3,4,5,6]. Research has recently shown that molecular dynamics (MD) is an efficient method to identify the nature of the interface and its effects on the properties of nanowires, composites, and core–shell structures. It also allows for effectively monitoring crystalline defects in microstructures at an atomic scale [7,8]. As important defects in crystalline structures, dislocations, stacking faults, and twins are the major explanations for plastic deformation within metals under mechanical loading [9,10]. Several factors, for example, strain rate, sample geometry, loading type, and temperature, are involved in crystalline defects [11,12]. However, the nature of the interface is a crucial determinant of mechanical behavior in core–shell nanostructures. Ke and Mastorakos [13] and Abdulkareem-Alsultan et al. [14] studied semi-coherent and coherent Cu/Ni and Au/Ni core–shell nanostructures. It was found that misfit dislocations in structures with a semi-coherent interface were the major cause of dislocation emission in the shell structure. However, the semi-coherent interface could be an obstacle to the transmission of dislocations from the shell into the core. A review of the literature indicates that core–shell structures are not limited to metals. Shang et al. [15] and Alsultan et al. [16] studied an Al2O3 ceramic shell for an Al core. Despite the incoherent core–shell interface, it was found that the O atoms of the ceramic shell and their bonding to the Al atoms of the core created a diffusional interface that enhanced the ductility of the Al2O3/Al core–shell structure. It should be noted that diffusion is very sensitive to temperature and time. Lee et al. [17] and Lim et al. [18] investigated Cu/Ag core–shell nanoparticles and observed that the diffusion of atoms in the core–shell interface was substantially dependent on the core and shell melting points. Samsonov et al. [19] discussed this phenomenon in detail. They found that the interface of a core–shell structure was destabilized for synthetic reasons at low temperatures, while interface instability at high temperatures arose from thermodynamic factors.

The shell structure can be not only crystalline structures (metals) but also non-crystalline structures (ceramics), as Pourboghrat et al. [20] and Feng et al. [21] reported for an Si–Au core–shell structure. They showed that an Si shell with an amorphous structure could enhance the yield strength of the system above that of the Au nanowire. However, the self-healing of the core–shell structure declined under cyclic loads. This was attributed to the change in the crystalline defects of the core from twins into perfect dislocations.

Apart from the influence of the shell microstructure on the mechanical properties of a shell–core structure, researchers [22,23,24,25] reported that the shell thickness would strongly affect the mechanical properties. They implemented tensile tests on Cu/Ag core–shell nanostructures of different core and shell thicknesses. It was observed that no certain thickness could be applied to improve all the mechanical properties, and the optimal yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and elasticity modulus would occur at different thicknesses. Ozdemir Kart et al. [26] and Cherukara et al. [27] evaluated Al–Cu core–shell structures and observed that dislocation tangling in the core–shell interface was the main parameter enhancing mechanical properties.

In addition to the formation of crystalline defects, the density of crystalline defects is also very important during the stages of plastic deformation. For example, the stacking fault region can be removed or expanded. Also, dislocations can slip and facilitate the plastic deformation acceleration [28,29,30,31,32,33]. As mentioned, the plastic deformation of core–shell structures is significantly dependent on the interface area [34,35,36]. Also, the presence of impurities or voids can affect thermal conductivity, mechanical properties, and other physical or mechanical properties of core–shell structures [37,38].

According to previous studies [39,40,41,42,43,44,45], magnetic properties, structural stability at high temperatures, and mechanical properties of core–shell structures are strongly dependent on the crystal defects in the microstructures of these materials. Therefore, the identification of crystal defects and the modification of the microstructure can determine the mentioned properties. Some of the crystal defects can be removed during the production process, and some can be removed after production by processes such as annealing.

Since Ni has high thermal resistance, Ni–Al core–shell nanostructures are considered to be heat-resistant nanostructures. Researchers [26,46,47] recently studied the effects of heat on the stability of Ni–Al core–shell structures with different core and shell thicknesses by LAMMPS software. They analyzed the crystalline structure and diffusion layer of the annealed core–shell microstructure at different temperatures. However, a review of the literature indicates that temperature has rarely been examined as a parameter with substantial effects on the mechanical properties and deformation mechanisms of such structures. The present work subjected Ni–Al core–shell samples to the uniaxial tensile test at 300 K using MD. Then, the samples were subjected to tests at the same strain rate and different temperatures to evaluate the role of the temperature in the deformation mechanism. The remainder of the study is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the MD simulations and sample development; Section 3 provides and discusses the results at different temperatures; and Section 4 concludes the study.

2 MD setup

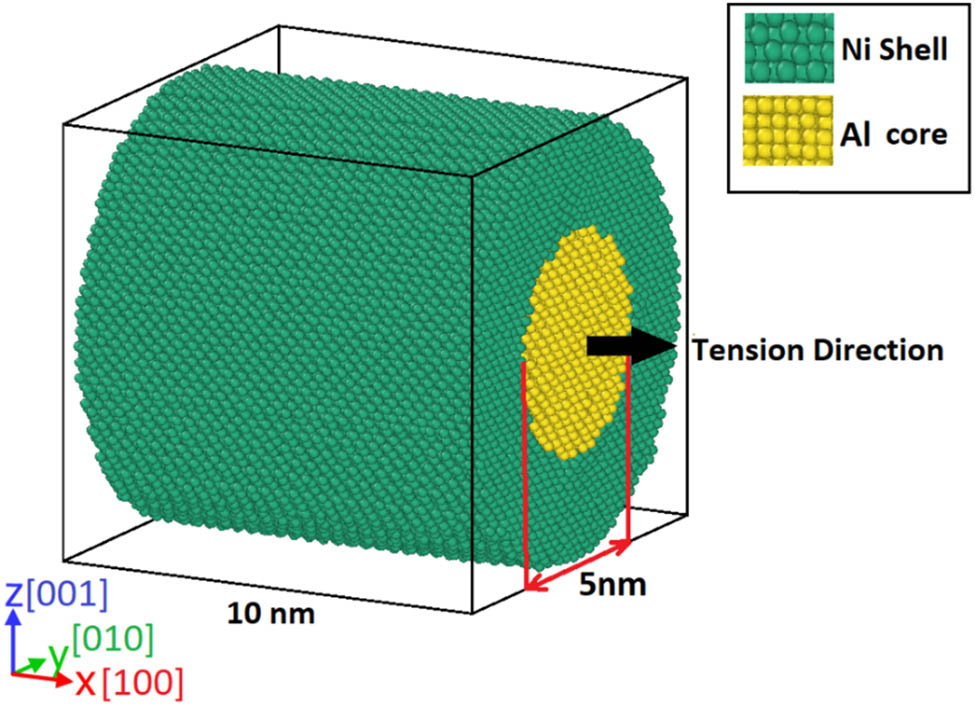

As previous studies investigated the effects of the core and shell thicknesses, this study assumed the same core and shell thickness. The core–shell nanowire samples consisted of a cylindrical Al core with a diameter of 5 nm and a length of 10 surrounded by an Ni shell with a thickness of 5 nm and a length of 10 nm was assumed, as shown in Figure 1. The samples and tensile test simulations were implemented using the LAMMPS code [46]. The interactions of Al–Al, Ni–Ni, and Ni–Al particles in the force and energy fields were simulated using an EAM potential function [23]. This function has been demonstrated to be very efficient in the mechanical evaluation of Al–Ni systems through the identification and examination of dislocations and defect areas in the layout [21,27]. This study calculated initial velocities using the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution at the given temperatures. Furthermore, the velocity Verlet algorithm was employed to integrate the motion equations [24,47].

Ni–Al core–shell nanowire construction step. Taken from OVITO software.

It was required to relax the samples before the tensile test. The samples were relaxed using the NPT ensemble at ambient temperature for 100 ps using a time step of 1 fs.

As seen in Figure 2, the values of the total energy of the system tend to the steady-state trend showing our method works successfully during the equilibration stage. Another parameter, which can help us to make sure about simulation protocols, is monitoring temperature fluctuations. As shown in Figure 3, temperature was successfully kept constant at 300 K during relaxation before applying uniaxial tensile test.

Total energy fluctuations during relaxation stage.

Temperature fluctuation during relaxation stage.

Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions. Once they had been relaxed, the samples in accordance with the literature were stretched at a constant engineering strain of 5 × 108 s−1 in the x-direction [4,25]. The pressure was controlled to be zero in the y- and z-directions to implement uniaxial tensile testing.

The dislocations were identified via the dislocation extraction algorithm (DXA) developed by Stukowski [5]. To measure the stress concentration in the crystalline defects and Ni–Al interface, von Mises stress analysis was used. The common neighbor analysis (CNA) was adopted to differentiate the structures. The images were obtained and analyzed using OVITO [5].

As mentioned, the CNA was used to characterize the local structural environment of atoms within the crystal structures. The structural types are encoded as integer values, which are 1 for face-centered cubic (FCC); 2 for hexagonal close-packed (HCP); 3 for body-centric cubic; 4 for icosahedral structures; and 5 for free surfaces, sample edges, and other unknown structures. In this technique, a threshold distance criterion is used to determine whether a pair of atoms is bonded or not. The input cutoff radius for any crystal lattice can be chosen using the following equations [30,31]:

In these equations,

Centro-symmetry parameter (CSP) was defined for the specified atom

where N is the number of nearest neighbors of atom

3 Results and discussion

In this section, we aim to study the mechanical behavior of Ni–Al core–shell structures. This step is followed by a quantitative and qualitative analysis of samples to evaluate microstructural changes during the mechanical tests. Subsequently, CNA and DXA analysis tools were utilized to explore the main sintering mechanisms governing the process.

3.1 Mechanical properties of Ni–Al core–shell nanowires

To investigate the mechanical properties, the Ni–Al core–shell sample was subjected to a uniaxial tensile test at 300 K, as shown in Figure 4. According to Figure 4, the length of sample increases as strain increased, with the sample showing ductile deformation behavior. Figure 5 plots the tensile stress–strain curve of the sample. As can be seen, the elastic region was almost linear, and the stress declined after the yielding of the sample. In the plastic region, the stress was independent of the strain. The CNA results are shown for different points in the elastic and plastic regions. The core and shell systems had a completely FCC structure below the yield stress. This structure is shown by green atoms. At the strain of 0.05, a step appeared in the elastic region; the first defect in the layout of atoms occurred, with FCC changing into HCP. These areas are represented by red atoms. As the strain increased to the plastic level, more defect areas appeared in the sample. Defects are very common in FCC metals due to the low stacking fault energy (SFE) [6,28]. The sample underwent completely ductile deformation – no brittle fracture was detected. The plastic deformation process is discussed in detail below. Table 1 provides the yield stress and elasticity modulus of the sample. It is worth mentioning that the linear slope of the stress–strain curve was assumed to represent the elasticity modulus.

Illustration of uniaxial tension steps of Ni–Al core–shell nanowire at different strains: (a) ε = 0, (b) ε = 0.02, (c) ε = 0.05, (d) ε = 0.08, (e) ε = 0.2, and (f) ε = 0.3.

Evaluation of crystalline structural changes before and after yielding point.

Yield strength and elastic modulus of the sample obtained in the present work

| Sample | Yield strength (GPa) | Elastic modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Ni–Al core–shell | 3.57 | 67 |

3.2 Plastic deformation of Ni–Al core–shell nanowires and underlying mechanisms

Research has shown that the plastic deformation of single-crystal FCC structures arises from active slip systems based on edge and screw dislocations. To further evaluate this phenomenon, Figure 6 shows different plastic deformation stages of the sample. As can be seen, edge dislocations occurred in the Ni–Al interface before plastic deformation (Figure 6a). As the stress rose above the plastic limit, defects appeared between the dislocations within Al, as shown in Figure 6b. At larger strains, edge and screw dislocations were emitted into Ni, as shown in Figure 6c and d. Figure 6e–h illustrates the process from another angle. Tian et al. [29] argued that SFE was lower in Al than in Ni. Therefore, defects were expected to form in Al and be emitted into Ni. As a result, the plastic deformation of Ni–Al nanowires can be concluded to stem from dislocation slips. As such, dislocations nucleated in the Ni–Al interface. Research has shown that dislocation would nucleate from free surfaces, grain boundaries, and impurities [30,31,32]. This is mainly explained by the stress concentration in these areas and reduced SFE [33]. To further evaluate the cause of dislocations in the Ni–Al interface, the stress distribution of the interface was analyzed. According to Figure 7a, the atoms in the interface had larger stresses than the atoms in the core and those at larger distances from the interface. Based on Figure 7b, the interface is a potential candidate for the appearance of dislocations and crystalline defects. Earlier works reported that dislocations had a lower energy barrier in areas with stress concentration, which facilitated dislocation emission [16,34,35]. The stress concentration in the interface arises from a lattice mismatch. For a lattice constant of 3.499 in Ni and 4.056 in Al, the lattice mismatch is obtained to be 15%, which is very large. Hence, the interface is assumed to be semi-coherent, and a high density of dislocations is expected to appear in the interface [37,38]. This is illustrated in Figure 7b. Once the deformation mechanism of the Ni–Al core–shell nanostructure had been evaluated at ambient temperature, the effects of the temperature on dislocations and defect areas as important determinants of plastic deformation in the nanostructure were explored.

DXA analysis results presenting the dislocation density and stacking fault areas in Ni–Al core–shell nanowire at the different strains. (a) ε = 0, (b) ε = 0.08, (c) ε = 0.15, (d) ε = 0.25, and (e–h) the other views at the same strains.

The interfacial region of Ni/Al nanowire sample. (a) Stress concentration shown by von Mises stress distribution map and (b) perfect dislocations detected by DXA analysis.

Figure 8a and b depicts the crystalline structure of the samples at 300 and 600 K, respectively. The green atoms represent FCC areas, while the red ones stand for HCP in the stacking fault structure. Figure 8c and d compares the dislocation distributions at 300 and 600 K, respectively. As can be seen, an increase in the temperature reduced dislocation forest areas. As the temperature rose, many dislocations having the opposite sign eliminated each other, diminishing dislocation entanglement. The red circles represent the entangled dislocations. As can be seen, dislocation recovery was facilitated at a higher temperature, increasing the mobility of the remaining dislocations, and reducing the mechanical properties.

CSP analysis and comparison of crystalline defects at the temperatures of 300 and 600 K: (a and b) the stacking fault areas and (c and d) dislocation entanglements.

4 Conclusion

This study evaluated the mechanical properties and plastic deformation mechanism of Ni/Al core–shell structures using MD. It was observed that the crystalline structure remained perfect in the elastic deformation, whereas stacking faults and dislocations nucleated from the Ni–Al interface above the yield point. Therefore, the interface became a source of dislocation emission due to stress concentration. The crystalline defect density increased as the stress increased. The dislocations were entangled as they increased in number, leading to dislocation entanglement areas that would impede the movement of dislocations and enhance mechanical properties. A rise in the temperature from 300 to 600 K decreased dislocation entanglement areas due to the activation of dislocation recovery mechanisms, diminishing the mechanical properties at higher temperatures. For the next step, the aim will be to study the effects of pre-existing crystalline defects on the mechanical properties of such core–shell structures. For this purpose, importing voids and inclusions inside the shell region, several defect concentrations will be systematically analyzed.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Southern Technical University (https://www.stu.edu.iq), Basra, Iraq, for supporting the present research.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Vaidya S, Ganguli AK. Microemulsion methods for synthesis of nanostructured materials. In: Andrews DL, Lipson RH, Nann T, editors. Comprehensive Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2nd ed. Cambridge (MA): Academic Press; 2019. p. 1–12.10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.11321-9Search in Google Scholar

[2] Aytac Z, Uyar T. Applications of core-shell nanofibers: Drug and biomolecules release and gene therapy. In: Focarete ML, Tampieri A, editors. Core-Shell Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Theranostics. Woodhead Publishing; 2018. p. 375–404.10.1016/B978-0-08-102198-9.00013-2Search in Google Scholar

[3] Hayes R, Ahmed A, Edge T, Zhang H. Core–shell particles: Preparation, fundamentals and applications in high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1357:36–52.10.1016/j.chroma.2014.05.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Wen Y-H, Zhu Z-Z, Zhu R-Z. Molecular dynamics study of the mechanical behavior of nickel nanowire: Strain rate effects. Comput Mater Sci. 2008;41:553–60.10.1016/j.commatsci.2007.05.012Search in Google Scholar

[5] Stukowski A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Model Simul Mater Sci Eng. 2009;18:015012.10.1088/0965-0393/18/1/015012Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ghoniem NM, Cui Y. Dislocation dynamics simulations of defects in irradiated materials. In: Konings RJM, Stoller RE, editors. Comprehensive Nuclear Materials. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2020. p. 689–716.10.1016/B978-0-12-803581-8.11657-1Search in Google Scholar

[7] Katakareddi G, Yedla N. Creep behavior of core (Metal)–Shell (Metallic Glass) Structure: A molecular dynamics simulation study. Trans Indian Natl Acad Eng. 2022;7:405–10.10.1007/s41403-021-00272-5Search in Google Scholar

[8] Yi Q, Xu J, Liu Y, Zhai D, Zhou K, Pan D. Molecular dynamics study on core-shell structure stability of aluminum encapsulated by nano-carbon materials. Chem Phys Lett. 2017;669:192–5.10.1016/j.cplett.2016.12.013Search in Google Scholar

[9] Alavi A, Mirabbaszadeh K, Nayebi P, Zaminpayma E. Molecular dynamics simulation of mechanical properties of Ni–Al nanowires. Comput Mater Sci. 2010;50:10–4.10.1016/j.commatsci.2010.06.037Search in Google Scholar

[10] Wu H. Molecular dynamics study on mechanics of metal nanowire. Mech Res Commun. 2006;33:9–16.10.1016/j.mechrescom.2005.05.012Search in Google Scholar

[11] Singh G, Waas AM, Sundararaghavan V. Understanding defect structures in nanoscale metal additive manufacturing via molecular dynamics. Comput Mater Sci. 2021;200:110807.10.1016/j.commatsci.2021.110807Search in Google Scholar

[12] Alsultan AG, Asikin-Mijan N, Obeas LK, Islam A, Mansir N, Teo SH, et al. Selective deoxygenation of sludge palm oil into diesel range fuel over Mn-Mo supported on activated carbon catalyst. Catalysts. 2022;12:566.10.3390/catal12050566Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ke H, Mastorakos I. Deformation behavior of core–shell nanowire structures with coherent and semi-coherent interfaces. J Mater Res. 2019;34:1093–102.10.1557/jmr.2018.491Search in Google Scholar

[14] Abdulkareem-Alsultan G, Asikin-Mijan N, Obeas LK, Yunus R, Razali SZ, Islam A, et al. In-situ operando and ex-situ study on light hydrocarbon-like-diesel and catalyst deactivation kinetic and mechanism study during deoxygenation of sludge oil. Chem Eng J. 2022;429:132206.10.1016/j.cej.2021.132206Search in Google Scholar

[15] Shang F, Cao Z, Sun W, Pang W, Fu J, Qiao B. The research state of Al2O3 ceramic toughening. In Proceedings of the 2015 4th International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Environmental Engineering; 2015 Dec 20–21; Shenzen, China. Springer Nature, 2015. p. 692–5.10.2991/icseee-15.2016.119Search in Google Scholar

[16] Alsultan AG, Asikin-Mijan N, Ibrahim Z, Yunus R, Razali SZ, Mansir N, et al. A short review on catalyst, feedstock, modernised process, current state and challenges on biodiesel production. Catalysts. 2021;11:1261.10.3390/catal11111261Search in Google Scholar

[17] Lee C, Kim NR, Koo J, Lee YJ, Lee HM. Cu-Ag core–shell nanoparticles with enhanced oxidation stability for printed electronics. Nanotechnology. 2015;26:455601.10.1088/0957-4484/26/45/455601Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Lim ST, Sethupathi S, Alsultan AG, Munusamy Y. Hydrogen production via activated waste aluminum cans and its potential for methanation. Energy Fuels. 2021;35:16212–21.10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c02277Search in Google Scholar

[19] Samsonov V, Talyzin I, Kartoshkin AY, Vasilyev S. Surface segregation in binary Cu–Ni and Au–Co nanoalloys and the core–shell structure stability/instability: thermodynamic and atomistic simulations. Appl Nanosci. 2019;9:119–33.10.1007/s13204-018-0895-5Search in Google Scholar

[20] Pourboghrat F, Park T, Kim H, Mohammed B, Esmaeilpour R, Hector LG. An integrated computational materials engineering approach for constitutive modelling of 3rd generation advanced high strength steels. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2018;1063:012010.10.1088/1742-6596/1063/1/012010Search in Google Scholar

[21] Feng J, Liu R, Guo B, Gao F, Zhou Q, Yang R, et al. Shock consolidation of Ni/Al nanoparticles: A molecular dynamics simulation. J Mater Eng Perform. 2022;31:3716–22.10.1007/s11665-021-06468-8Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sarkar J, Bhattacharyya M, Kumar R, Mandal N, Mallik M. Synthesis and characterizations of Cu–Ag core–shell nanoparticles. Adv Sci Lett. 2016;22:193–6.10.1166/asl.2016.6804Search in Google Scholar

[23] Mishin Y. Atomistic modeling of the γ and γ′-phases of the Ni–Al system. Acta Mater. 2004;52:1451–67.10.1016/j.actamat.2003.11.026Search in Google Scholar

[24] Asikin-Mijan N, Mohd Sidek H, AlSultan AG, Azman NA, Adzahar NA, Ong HC. Single-atom catalysts: A review of synthesis strategies and their potential for biofuel production. Catalysts. 2021;11:1470.10.3390/catal11121470Search in Google Scholar

[25] Liu L, Deng Q, Su M, An M, Wang R. Strain rate and temperature effects on tensile behavior of Ti/Al multilayered nanowire: A molecular dynamics study. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019;135:106272.10.1016/j.spmi.2019.106272Search in Google Scholar

[26] Ozdemir Kart S, Kart H, Cagin T. Atomic-scale insights into structural and thermodynamic stability of spherical Al@ Ni and Ni@ Al core–shell nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res. 2020;22:1–19.10.1007/s11051-020-04862-2Search in Google Scholar

[27] Cherukara MJ, Weihs TP, Strachan A. Molecular dynamics simulations of the reaction mechanism in Ni/Al reactive intermetallics. Acta Mater. 2015;96:1–9.10.1016/j.actamat.2015.06.008Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kamil FH, Salmiaton A, Shahruzzaman RMHR, Omar R, Alsultsan AG. Characterization and application of aluminum dross as catalyst in pyrolysis of waste cooking oil. Bull Chem React Eng Catal. 2017;12:81–8.10.9767/bcrec.12.1.557.81-88Search in Google Scholar

[29] Tian S, Zhu X, Wu J, Yu H, Shu D, Qian B. Influence of temperature on stacking fault energy and creep mechanism of a single crystal nickel-based superalloy. J Mater Sci Technol. 2016;32:790–8.10.1016/j.jmst.2016.01.020Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chen LY, He M-R, Shin J, Richter G, Gianola DS. Measuring surface dislocation nucleation in defect-scarce nanostructures. Nat Mater. 2015;14:707–13.10.1038/nmat4288Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Gouldstone A, Van Vliet KJ, Suresh S. Simulation of defect nucleation in a crystal. Nature. 2001;411:656–6.10.1038/35079687Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Panda AK, Divakar R, Singh A, Thirumurugesan R, Parameswaran P. Molecular dynamics studies on formation of stacking fault tetrahedra in FCC metals. Comput Mater Sci. 2021;186:110017.10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110017Search in Google Scholar

[33] Lenihan C, Corcoran D, Nakahara S. Molecular dynamic simulation of a metal crystal under stress. AIP Conf Proc. 2007;945(1):11.10.1063/1.2815772Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yang Z, Li M, Li Y, Yang Y, Zhao J. Molecular dynamics simulation on torsion deformation of copper aluminum core–shell nanowires. J Nanopart Res. 2021;23:1–10.10.1007/s11051-021-05344-9Search in Google Scholar

[35] Teo SH, Ng CH, Islam A, Abdulkareem-Alsultan G, Joseph CG, Janaun J, et al. Sustainable toxic dyes removal with advanced materials for clean water production: A comprehensive review. J Clean Prod. 2021;130039.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.130039Search in Google Scholar

[36] Alsultan AG, Asikin Mijan N, Mansir N, Razali SZ, Yunus R, Taufiq-Yap YH. Combustion and emission performance of CO/NOx/SOx for green diesel blends in a swirl burner. ACS Omega. 2020;6:408–15.10.1021/acsomega.0c04800Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Islam A, Roy S, Khan MA, Mondal P, Teo SH, Taufiq-Yap YH, et al. Improving valuable metal ions capturing from spent Li-ion batteries with novel materials and approaches. J Mol Liq. 2021;338:116703.10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116703Search in Google Scholar

[38] Amigo N, Gutiérrez G, Ignat M. Atomistic simulation of single crystal copper nanowires under tensile stress: Influence of silver impurities in the emission of dislocations. Comput Mater Sci. 2014;87:76–82.10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.02.014Search in Google Scholar

[39] Yu F, Hang C, Zhao M, Chen H. An interconnection method based on Sn-coated Ni core-shell powder preforms for high-temperature applications. J Alloy Compd. 2019;776:791–7.10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.10.267Search in Google Scholar

[40] Liu W, Zhong W, Du Y. Magnetic nanoparticles with core/shell structures. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2008;8:2781–92.10.1166/jnn.2008.18307Search in Google Scholar

[41] Wang Y, Wang F, Qi Z, Wang Y, Yu W. Thermal behavior of Bi-Ni core-shell nanoparticles with different Ni shell thicknesses: A molecular dynamics study. Comput Mater Sci. 2022;211:111557.10.1016/j.commatsci.2022.111557Search in Google Scholar

[42] Tsuji M, Yamaguchi D, Matsunaga M, Ikedo K. Epitaxial growth of Au@ Ni core− shell nanocrystals prepared using a two-step reduction method. Cryst Growth Des. 2011;11:1995–2005.10.1021/cg200199bSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Wang Q, Wang X, Liu J, Yang Y. Cu–Ni core–shell nanoparticles: Structure, stability, electronic, and magnetic properties: a spin-polarized density functional study. J Nanopart Res. 2017;19:1–12.10.1007/s11051-016-3731-4Search in Google Scholar

[44] Wei S, Wang Q, Zhu J, Sun L, Lin H, Guo Z. Multifunctional composite core–shell nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2011;3:4474–502.10.1039/c1nr11000dSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Wang M, Lu Y, Zhang G, Cui H, Xu D, Wei N, et al. A novel high-entropy alloy composite coating with core-shell structures prepared by plasma cladding. Vacuum. 2021;184:109905.10.1016/j.vacuum.2020.109905Search in Google Scholar

[46] Plimpton S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J Computational Phys. 1995;117:1–19.10.2172/10176421Search in Google Scholar

[47] Allen MP, Tildesley DJ. Computer Simulation of Liquids. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2017.10.1093/oso/9780198803195.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation of differential shrinkage stresses in a revolution shell structure due to the evolving parameters of concrete

- Multiphysics analysis for fluid–structure interaction of blood biological flow inside three-dimensional artery

- MD-based study on the deformation process of engineered Ni–Al core–shell nanowires: Toward an understanding underlying deformation mechanisms

- Experimental measurement and numerical predictions of thickness variation and transverse stresses in a concrete ring

- Studying the effect of embedded length strength of concrete and diameter of anchor on shear performance between old and new concrete

- Evaluation of static responses for layered composite arches

- Nonlocal state-space strain gradient wave propagation of magneto thermo piezoelectric functionally graded nanobeam

- Numerical study of the FRP-concrete bond behavior under thermal variations

- Parametric study of retrofitted reinforced concrete columns with steel cages and predicting load distribution and compressive stress in columns using machine learning algorithms

- Application of soft computing in estimating primary crack spacing of reinforced concrete structures

- Identification of crack location in metallic biomaterial cantilever beam subjected to moving load base on central difference approximation

- Numerical investigations of two vibrating cylinders in uniform flow using overset mesh

- Performance analysis on the structure of the bracket mounting for hybrid converter kit: Finite-element approach

- A new finite-element procedure for vibration analysis of FGP sandwich plates resting on Kerr foundation

- Strength analysis of marine biaxial warp-knitted glass fabrics as composite laminations for ship material

- Analysis of a thick cylindrical FGM pressure vessel with variable parameters using thermoelasticity

- Structural function analysis of shear walls in sustainable assembled buildings under finite element model

- In-plane nonlinear postbuckling and buckling analysis of Lee’s frame using absolute nodal coordinate formulation

- Optimization of structural parameters and numerical simulation of stress field of composite crucible based on the indirect coupling method

- Numerical study on crushing damage and energy absorption of multi-cell glass fibre-reinforced composite panel: Application to the crash absorber design of tsunami lifeboat

- Stripped and layered fabrication of minimal surface tectonics using parametric algorithms

- A methodological approach for detecting multiple faults in wind turbine blades based on vibration signals and machine learning

- Influence of the selection of different construction materials on the stress–strain state of the track

- A coupled hygro-elastic 3D model for steady-state analysis of functionally graded plates and shells

- Comparative study of shell element formulations as NLFE parameters to forecast structural crashworthiness

- A size-dependent 3D solution of functionally graded shallow nanoshells

- Special Issue: The 2nd Thematic Symposium - Integrity of Mechanical Structure and Material - Part I

- Correlation between lamina directions and the mechanical characteristics of laminated bamboo composite for ship structure

- Reliability-based assessment of ship hull girder ultimate strength

- Finite element method on topology optimization applied to laminate composite of fuselage structure

- Dynamic response of high-speed craft bottom panels subjected to slamming loadings

- Effect of pitting corrosion position to the strength of ship bottom plate in grounding incident

- Antiballistic material, testing, and procedures of curved-layered objects: A systematic review and current milestone

- Thin-walled cylindrical shells in engineering designs and critical infrastructures: A systematic review based on the loading response

- Laminar Rayleigh–Benard convection in a closed square field with meshless radial basis function method

- Determination of cryogenic temperature loads for finite-element model of LNG bunkering ship under LNG release accident

- Roundness and slenderness effects on the dynamic characteristics of spar-type floating offshore wind turbine

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation of differential shrinkage stresses in a revolution shell structure due to the evolving parameters of concrete

- Multiphysics analysis for fluid–structure interaction of blood biological flow inside three-dimensional artery

- MD-based study on the deformation process of engineered Ni–Al core–shell nanowires: Toward an understanding underlying deformation mechanisms

- Experimental measurement and numerical predictions of thickness variation and transverse stresses in a concrete ring

- Studying the effect of embedded length strength of concrete and diameter of anchor on shear performance between old and new concrete

- Evaluation of static responses for layered composite arches

- Nonlocal state-space strain gradient wave propagation of magneto thermo piezoelectric functionally graded nanobeam

- Numerical study of the FRP-concrete bond behavior under thermal variations

- Parametric study of retrofitted reinforced concrete columns with steel cages and predicting load distribution and compressive stress in columns using machine learning algorithms

- Application of soft computing in estimating primary crack spacing of reinforced concrete structures

- Identification of crack location in metallic biomaterial cantilever beam subjected to moving load base on central difference approximation

- Numerical investigations of two vibrating cylinders in uniform flow using overset mesh

- Performance analysis on the structure of the bracket mounting for hybrid converter kit: Finite-element approach

- A new finite-element procedure for vibration analysis of FGP sandwich plates resting on Kerr foundation

- Strength analysis of marine biaxial warp-knitted glass fabrics as composite laminations for ship material

- Analysis of a thick cylindrical FGM pressure vessel with variable parameters using thermoelasticity

- Structural function analysis of shear walls in sustainable assembled buildings under finite element model

- In-plane nonlinear postbuckling and buckling analysis of Lee’s frame using absolute nodal coordinate formulation

- Optimization of structural parameters and numerical simulation of stress field of composite crucible based on the indirect coupling method

- Numerical study on crushing damage and energy absorption of multi-cell glass fibre-reinforced composite panel: Application to the crash absorber design of tsunami lifeboat

- Stripped and layered fabrication of minimal surface tectonics using parametric algorithms

- A methodological approach for detecting multiple faults in wind turbine blades based on vibration signals and machine learning

- Influence of the selection of different construction materials on the stress–strain state of the track

- A coupled hygro-elastic 3D model for steady-state analysis of functionally graded plates and shells

- Comparative study of shell element formulations as NLFE parameters to forecast structural crashworthiness

- A size-dependent 3D solution of functionally graded shallow nanoshells

- Special Issue: The 2nd Thematic Symposium - Integrity of Mechanical Structure and Material - Part I

- Correlation between lamina directions and the mechanical characteristics of laminated bamboo composite for ship structure

- Reliability-based assessment of ship hull girder ultimate strength

- Finite element method on topology optimization applied to laminate composite of fuselage structure

- Dynamic response of high-speed craft bottom panels subjected to slamming loadings

- Effect of pitting corrosion position to the strength of ship bottom plate in grounding incident

- Antiballistic material, testing, and procedures of curved-layered objects: A systematic review and current milestone

- Thin-walled cylindrical shells in engineering designs and critical infrastructures: A systematic review based on the loading response

- Laminar Rayleigh–Benard convection in a closed square field with meshless radial basis function method

- Determination of cryogenic temperature loads for finite-element model of LNG bunkering ship under LNG release accident

- Roundness and slenderness effects on the dynamic characteristics of spar-type floating offshore wind turbine