Computer-aided drug design of capuramycin analogues as anti-tuberculosis antibiotics by 3D-QSAR and molecular docking

-

Yuanyuan Jin

, Steven G. Van Lanen

Abstract

Capuramycin and a few semisynthetic derivatives have shown potential as anti-tuberculosis antibiotics.To understand their mechanism of action and structureactivity relationships a 3D-QSAR and molecular docking studies were performed. A set of 52 capuramycin derivatives for the training set and 13 for the validation set was used. A highly predictive MFA model was obtained with crossvalidated q2 of 0.398, and non-cross validated partial least-squares (PLS) analysis showed a conventional r2 of 0.976 and r2pred of 0.839. The model has an excellent predictive ability. Combining the 3D-QSAR and molecular docking studies, a number of new capuramycin analogs with predicted improved activities were designed. Biological activity tests of one analog showed useful antibiotic activity against Mycobacterium smegmatis MC2 155 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Computer-aided molecular docking and 3D-QSAR can improve the design of new capuramycin antimycobacterial antibiotics.

1 Introduction

The dramatic increase in multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria is now a global threat to human health [1,2]. Development of novel, compounds with a new mechanism to fight MDR strains is required. Peptidoglycan is a unique feature in bacteria cell walls, without an equivalent in eukaryotes [3]. Enzymes involved in its biosynthesis are ubiquitous and essential to bacterial growth, In particular, translocase I (MraY) [4], which catalyzes the first membrane step of peptidoglycan biosynthesis [5,6], has been little exploited due to its transmembrane location [7], and it is not the target of any antibiotics in clinical use. The crystal structure of MraY from Aquifex aeolicus (MraYAA) was recently solved at 3.3Å by Chung and colleagues [8], and several inhibitors of this enzyme are known. These make the discovery of new potent inhibitors possible.

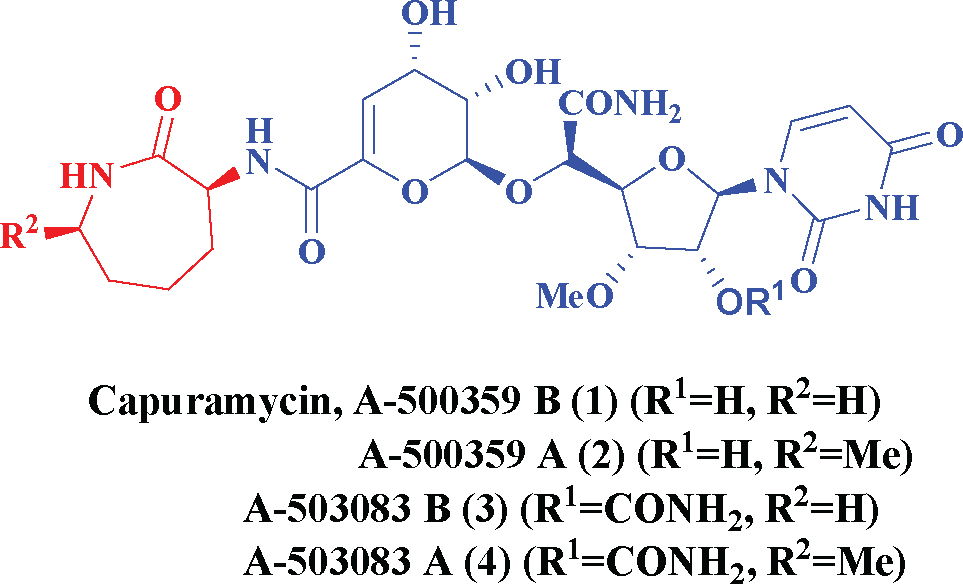

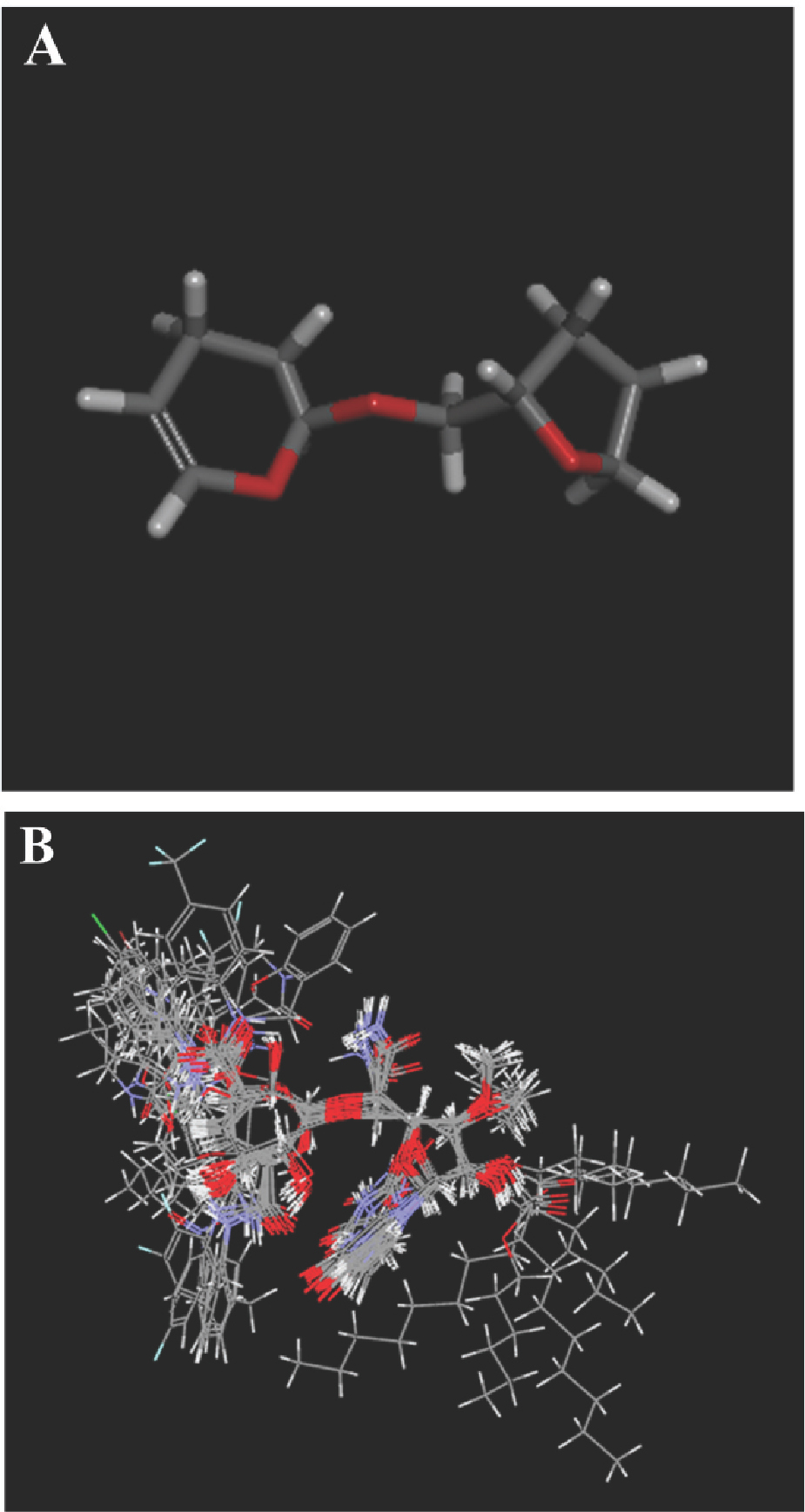

Capuramycin, originally isolated from the culture broth of Streptomyces griseus 446-S3, and its methylated derivative, A-500359A (Figure 1) were found while screening for new antibiotics with translocase-I inhibitory activity. These capuramycin-related compounds include a series of congeners termed A-500359s and the 2-O- carbamoylated variants A-503083s. Capuramycin and A-500359A inhibit translocase I with IC50 values of 10 ng/mL (18nM) and 10 ng/mL (17 nM), respectively [9]. The MIC values for capuramycin and A-500359A against Mycobacterium smegmatis SANK75075 are 12.5 and 6.25 mg/mL, respectively. A series of acylated derivatives of capuramycin and analogues having a variety of substituents in place of the azepan-2-one moiety were synthesized and their antimycobacterial activities tested by Sankyo Co., Ltd. [10,11]. Although narrow in spectrum, bioactivity studies have revealed their potential utility as anti-tuberculosis antibiotics.

Capuramycin and its congeners.

Computer-aided drug design has been extensively applied in the area of modern drug discovery [12,13]. QSAR analysis generates models correlating biological activity and the physicochemical properties of a series of molecules. A validated 3D-QSAR model not only helps understanding the structure-activity relationships, but also provides insight into lead molecules for further development [14].

Our goal was to perform a 3D-QSAR [15] study to explore the relationship between the structure of capuramycin analogues and their MraY inhibitory activity. The contour maps derived from the models provide an insight into the steric and electrostatic requirements for ligand binding. By molecular docking analyses [16] we sought active site structural features and details of protein–inhibitor interactions to design new potential inhibitors.

2 Experimental Procedure

2.1 Preparation of Receptor Structures and Databases

All work was performed using Discovery Studio 3.5 software (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA) on a Dell Precision TM T5500 computer.

The crystal structure of MraY (PDB ID 4J72) was downloaded from the RCSB Brookhaven Protein Data Bank [17,18].

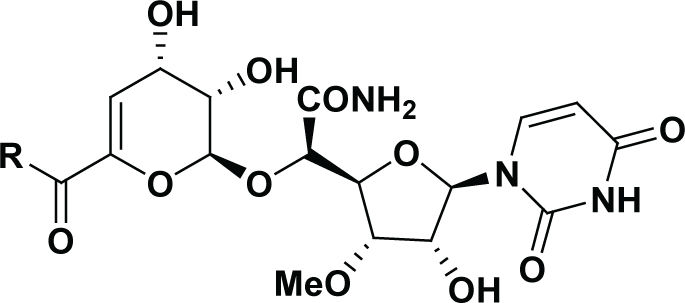

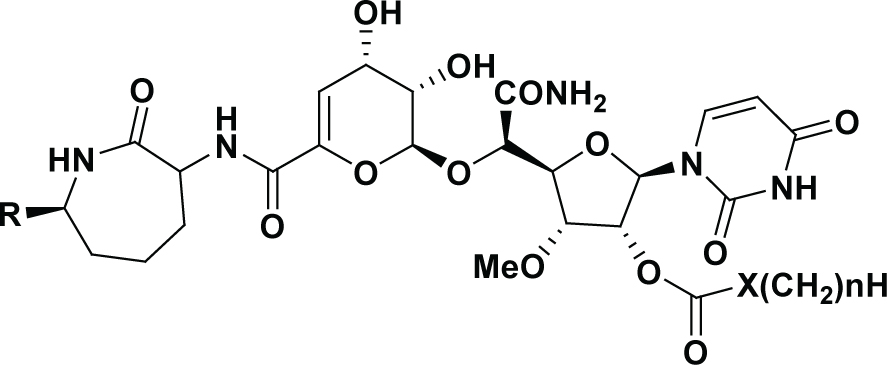

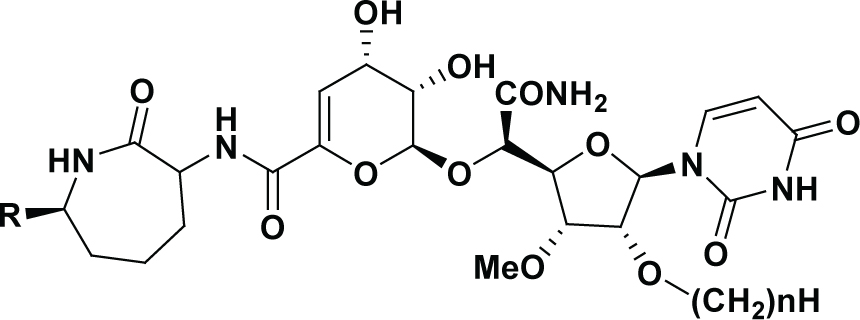

A total of 65 capuramycin derivatives were used. Their structures and inhibitory activities (measured under similar conditions) are shown in Table 1 [10,11]. The IC50 values were converted to pIC50 (-log IC50) values and used as dependent variables for 3D-QSAR analysis. The dataset was divided into a training set of 52 compounds (80% of the original data) to derive the models, and a test set of the remaining 13 compounds (20%) to determine the external predictivity of the resulting models, using the Generate Training and Test Data module.

Experimental and 3D-QSAR predicted MraY inhibition activities of capuramycin derivatives.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | IC50 (nM) | pIC50 | DS pIC50 | Residual | -CDOCKER_ INTERACTION_ ENERGY |

| Capuramycin | 18 | -1.255 | -1.492 | 0.237 | 88.45 | |

| A-500359A | 17 | -1.230 | -1.373 | 0.143 | 79.02 | |

| 3 | Me(CH2)3NH– | 545 | -2.736 | -2.570 | -0.166 | 82.38 |

| 4 | Me(CH2)5NH– | 55 | -1.740 | -1.752 | 0.012 | 73.76 |

| 5 | Cyclohexyl-NH– | 56 | -1.748 | -1.830 | 0.082 | 76.48 |

| 6 | Cycloheptyl-NH– | 49 | -1.690 | -1.650 | -0.040 | 81.22 |

| 7 | EtO(CH2)3NH– | 257 | -2.410 | -2.402 | -0.008 | 80.69 |

| 8 | MeS(CH2)3NH– | 128 | -2.107 | -2.081 | -0.026 | 77.02 |

| 9 | H2N(CH2)2NH– | 1198 | -3.078 | -2.993 | -0.085 | 82.05 |

| 10 | Me(CH2)9NH– | 435 | -2.638 | -2.560 | -0.078 | 80.83 |

| 11 | Ph(CH2)2NH– | 37 | -1.568 | -1.502 | -0.066 | 78.87 |

| 12 | 4-Me–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 59 | -1.771 | -1.905 | 0.134 | 77.90 |

| [*]13 | 4-MeO–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 68 | -1.833 | 1.881 | 0.048 | 81.73 |

| 14 | 3-MeO–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 32 | -1.505 | -1.624 | 0.119 | 79.22 |

| 15 | 3,4-(MeO)2–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 40 | -1.602 | -1.491 | -0.111 | 83.39 |

| [*]16 | 4-F–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 38 | -1.580 | -1.777 | 0.197 | 78.57 |

| 17 | 2-Cl–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 47 | -1.672 | -1.881 | 0.209 | 86.69 |

| [*]18 | 3-Cl–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 34 | -1.531 | -1.751 | 0.220 | 70.64 |

| 19 | 2,4-Cl2–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 30 | -1.477 | -1.487 | 0.010 | 84.91 |

| [*]20 | 4-HO–Ph(CH2)2NH– | 104 | -2.017 | -1.708 | -0.309 | 77.93 |

| 21 | PhCH2NH– | 219 | -2.340 | -2.502 | 0.162 | 75.05 |

| [*]22 | 2-Me–PhCH2NH– | 890 | -2.949 | -1.952 | -0.997 | 79.24 |

| 23 | 4-Me–PhCH2NH– | 2135 | -3.329 | -3.254 | -0.075 | 79.67 |

| 24 | 4-F–PhCH2NH– | 353 | -2.548 | -2.538 | -0.010 | 85.26 |

| 25 | 2-MeO–PhCH2NH– | 484 | -2.685 | -2.788 | 0.103 | 82.13 |

| 26 | 4-MeO–PhCH2NH– | 1211 | -3.083 | -3.114 | 0.031 | 83.60 |

| 27 | PhNH– | 12 | -1.079 | -1.107 | 0.028 | 81.54 |

| 28 | 3-Me–PhNH– | 14 | -1.146 | -1.086 | -0.060 | 84.17 |

| 29 | 4-Me–PhNH– | 24 | -1.380 | -1.464 | 0.084 | 78.39 |

| 30 | 2,4-Me2–PhNH– | 107 | -2.029 | -1.909 | -0.120 | 78.10 |

| 31 | 2-Et–PhNH– | 96 | -1.982 | -2.032 | 0.050 | 87.09 |

| 32 | 4-Et–PhNH– | 36 | -1.556 | -1.354 | -0.202 | 78.15 |

| 33 | 4-(Me(CH2)5)–PhNH– | 259 | -2.413 | -2.280 | -0.133 | 82.86 |

| [*]34 | 4-CF3–PhNH– | 50 | -1.699 | -1.823 | 0.124 | 80.29 |

| [*]35 | 2-MeO–PhNH– | 55 | -1.740 | -1.912 | 0.172 | 83.84 |

| 36 | 2-EtO–PhNH– | 64 | -1.806 | -1.915 | 0.109 | 86.01 |

| [*]37 | 3-F–PhNH– | 18 | -1.255 | -1.610 | 0.355 | 73.15 |

| [*]38 | 4-F–PhNH– | 67 | -1.826 | -1.583 | -0.243 | 72.47 |

| 39 | 2,3-F2–PhNH– | 23 | -1.362 | -1.073 | -0.289 | 76.71 |

| [*]40 | 2,4-F2–PhNH– | 26 | -1.415 | -1.663 | 0.248 | 81.59 |

| 41 | 3,4-F2–PhNH– | 16 | -1.204 | -1.160 | -0.044 | 80.15 |

| 42 | 4-Cl–PhNH– | 32 | -1.505 | -1.601 | 0.096 | 78.52 |

| 43 | 4-Br–PhNH– | 33 | -1.519 | -1.502 | -0.017 | 88.96 |

| 44 | 2-NO2–PhNH– | 69 | -1.839 | -1.563 | -0.276 | 83.68 |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound R | X | n | IC50 (nM) | pIC50 | DS pIC50 | Residual | -CDOCKER_ INTERACTION_ ENERGY | |

| 45 | H | CH2 | 5 | 59 | -1.771 | -1.726 | -0.045 | 75.35 |

| 46 | H | CH2 | 7 | 254 | -2.405 | -2.312 | -0.093 | 88.70 |

| 47 | H | CH2 | 8 | 415 | -2.618 | -2.404 | -0.214 | 92.29 |

| 48 | Me | CH2 | 3 | 36 | -1.556 | -1.316 | -0.240 | 82.10 |

| 49 | Me | CH2 | 4 | 63 | -1.799 | -1.774 | -0.025 | 90.11 |

| 50 | Me | CH2 | 5 | 65 | -1.813 | -2.053 | 0.240 | 86.15 |

| 51 | Me | CH2 | 6 | 268 | -2.428 | -2.673 | 0.245 | 87.19 |

| 52 | Me | CH2 | 7 | 235 | -2.371 | -2.421 | 0.050 | 87.40 |

| 53 | Me | CH2 | 8 | 746 | -2.873 | -2.614 | -0.259 | 82.00 |

| [*]54 | Me | CH2 | 10 | 2876 | -3.459 | -2.460 | -0.999 | 57.23 |

| 55 | Me | CH2 | 12 | 5675 | -3.754 | -3.371 | -0.383 | 57.41 |

| [*]56 | Me | CH2 | 13 | 2974 | -3.473 | -2.340 | -1.133 | 61.71 |

| 57 | Me | CH2 | 14 | 524 | -2.719 | -2.698 | -0.021 | 89.19 |

| 58 | Me | O | 6 | 183 | -2.262 | -2.463 | 0.201 | 91.69 |

| 59 | Me | O | 7 | 276 | -2.441 | -2.642 | 0.201 | 86.13 |

| 60 | Me | O | 8 | 677 | -2.831 | -2.757 | -0.074 | 84.43 |

| [*]61 | Me | O | 9 | 1859 | -3.269 | -2.634 | -0.635 | 95.46 |

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | n | IC50 (nM) | pIC50 | DS pIC50 | Residual | -CDOCKER_ INTERACTION, ENERGY |

| 62 | Me | 5 | 77 | -1.886 | -2.012 | 0.126 | 73.68 |

| 63 | Me | 6 | 60 | -1.778 | -2.403 | 0.625 | 76.64 |

| 64 | Me | 8 | 216 | -2.334 | -2.470 | 0.136 | 81.75 |

| 65 | Me | 10 | 885 | -2.947 | -2.677 | -0.270 | 87.06 |

2.2 3D-QSAR models

A quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) is one of the most important chemometric applications, giving information useful for the design of new compounds acting on a target [12]. A proper alignment of the structures is critical for obtaining a valid 3D-QSAR [19,20]. An automatic alignment based on the common structure was performed by Align to Selected Structure. The most active compound (27) with the minimum IC50 was used as the alignment template. Figure 2A shows the common alignment scaffold while Figure 2B shows the alignment conformations of all training set molecules.

(A) Common scaffold used for alignment. (B) Structural alignment of the training set derivatives.

Regression models built from whole-molecular steric and electrostatic fields can be useful for predicting activity and for visualizing favorable and unfavorable interactions. The 3D-QSAR module came from MFA (molecular field analysis) in Cerius 2. MFA computes the steric and electrostatic interactions of a series of molecules using probes in a regularly spaced grid [21]. The PLS regression performed generalizes and combines features from principal component analysis (PCA) and multiple regression. The PLS “leave-one-out” method [22] was used for cross validation to obtain the q2 value and the optimum number of components to be used in the final QSAR models. The cross-validated q2 indicates the predictive power of the analysis [23]; q2 > 0.3 indicates the probability of chance correlation is less than 5% [24]. The non-cross-validated PLS analysis of these compounds was repeated with the optimum number of components as determined by the cross-validated analysis [25].

2.3 Molecular Docking

Computational docking is useful to probe the interaction of a receptor with its ligand and reveal their binding mechanism; it is a module where two or more molecules recognize each other by geometry and energy matching. It can offer insight into the protein–inhibitor interactions and the active site structural features [26,27,28,29,30]. Molecular docking computations were carried out using the CDOCKER [31,32,33,35] program employing the CHARMm [36] force field using the consistent force field ligand partial charge method to validate the ideas on design of these inhibitors. For ligand preparation, duplicate structures were removed and options for ionization change, tautomer generation, isomer generation, Lipinski filter and 3D generator were set true. For enzyme preparation, the whole enzyme was selected, waters removed and hydrogen atoms were added. The pH of the protein was set in the range 6.5-8.5. The enzyme was defined as a total receptor; its binding site defined by selecting the amino acids Asp117, Asp118, Asp265 and His324 (mutational studies showed these residues are important for catalysis) to generate a 15 Å radius sphere by the operation of Define and Edit Binding Site. Docking of compounds into MraY with CDOCKER was done using the default parameters. Energy was minimized until an energy gradient of 0.01 was reached. The configuration with the highest -CDOCKER_INTERACTION_ENERGY was chosen to analyze the binding features.

Ethical approval

The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 3D-QSAR analysis

3.1.1 MFA statistical analysis

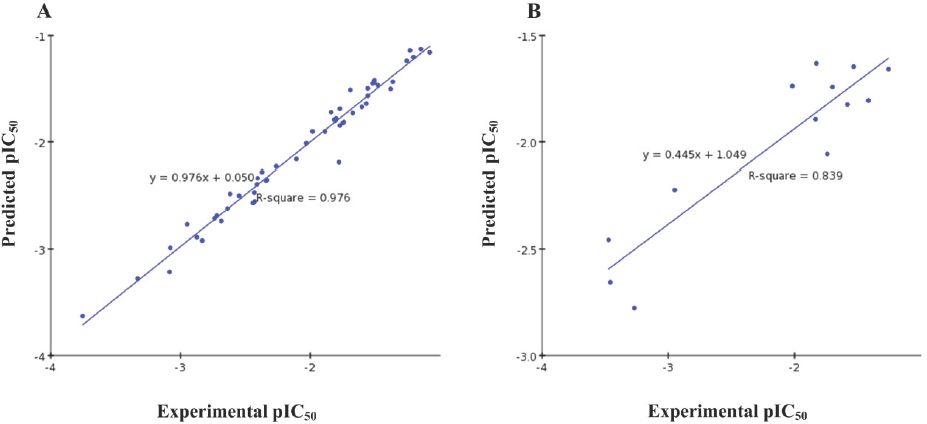

The MFA model was constructed using 52 capuramycin derivatives as the training set. This model was used to predict activities of the test set of 13 compounds. The models were generated with 3 optimal components giving a cross-validated q2 of 0.398, signifying good predictive ability. The calculated activities, predicted activities and residuals in the training and test sets are listed in Table 1. The predicted pIC50 values are within statistically tolerable error of the experimental data. The non-cross validated r2 (0.976) suggested good model linearity. The predictive correlation coefficient r2pred was 0.839; comparisons of the predicted and experimental values are in Figure 3.

Predicted versus experimental pIC50 values; (A) training set; (B) test set.

The resulting 3D-QSAR model is statistically significant and reliable, and was used to design novel capuramycin derivatives with improved MraY inhibitory activity.

3.1.2 MFA contour plots

Contour maps provide information on factors affecting compound activity. This is particularly important when designing a new drug by changing the structural features contributing to the interaction between the ligand and the active site. Therefore, it is essential routine in designing and evaluating novel inhibitors.

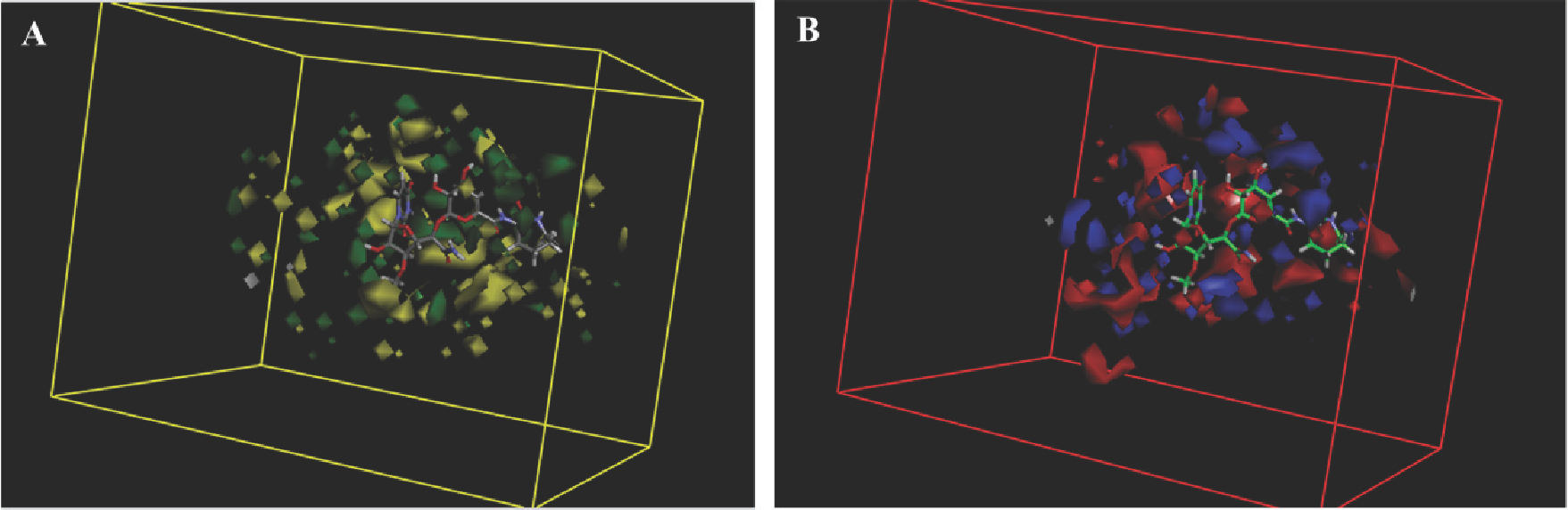

The analysis contour plots are shown in Figure 4. In the steric contour map, green regions indicate areas where steric bulk is predicted to enhance the inhibition activity, and yellow indicates regions where bulk is predicted to decrease it. In the electrostatic contour map, blue regions denote areas where electropositive groups are predicted to improve inhibition affinity, while red regions represent areas where electronegative groups are predicted to improve it. Capuramycin was embedded into the maps to illustrate its relationships to the inhibitors’ steric and electrostatic properties.

MFA contour maps for steric (A) and electrostatic (B) effects with capuramycin as the reference molecule.

In Figure 4A, yellow regions located near the capuramycin azepan-2-one group indicate that large substituents around this position might decrease the activity. This is supported by the observation that compounds 3 and 10 with large alkyl groups there displayed low activities. The other major yellow contour was found around the nucleoside 2’-OH, implying that large substituents in this position can decrease activity. This may be why acyl/alkoxycarbonyl derivatives 45-65 around the 2’- position showed less potency than compounds without substituents there. A major green contour surrounding the sugar hydroxyl suggests that bulky substituents there could improve the inhibitory potency.

In Figure 4B, the zepan-2-one moiety of capuramycin is embedded in a large red region and the other two red contours were observed around this position, indicating that negatively charged substituents there favored activity.

In support, compound 27 with a phenyl substituent there possessed the highest potency. Interestingly, though compounds 11-21 having phenethyl-type substituents and compounds 22-27 having benzyl-type substituents were all substituted by electronegative groups, they were less potent than phenyl analogues. This may be due to the substituents’ steric conformation. In addition, some blue contours favoring positively charged substitution was observed around the nucleoside 2’-OH, suggesting that an electropositive substituent at this position was favored. However, inhibitory activity was related to the size of alkyl chain as well. As the alkyl chain became longer activity decreased, as shown by compounds 49-57.

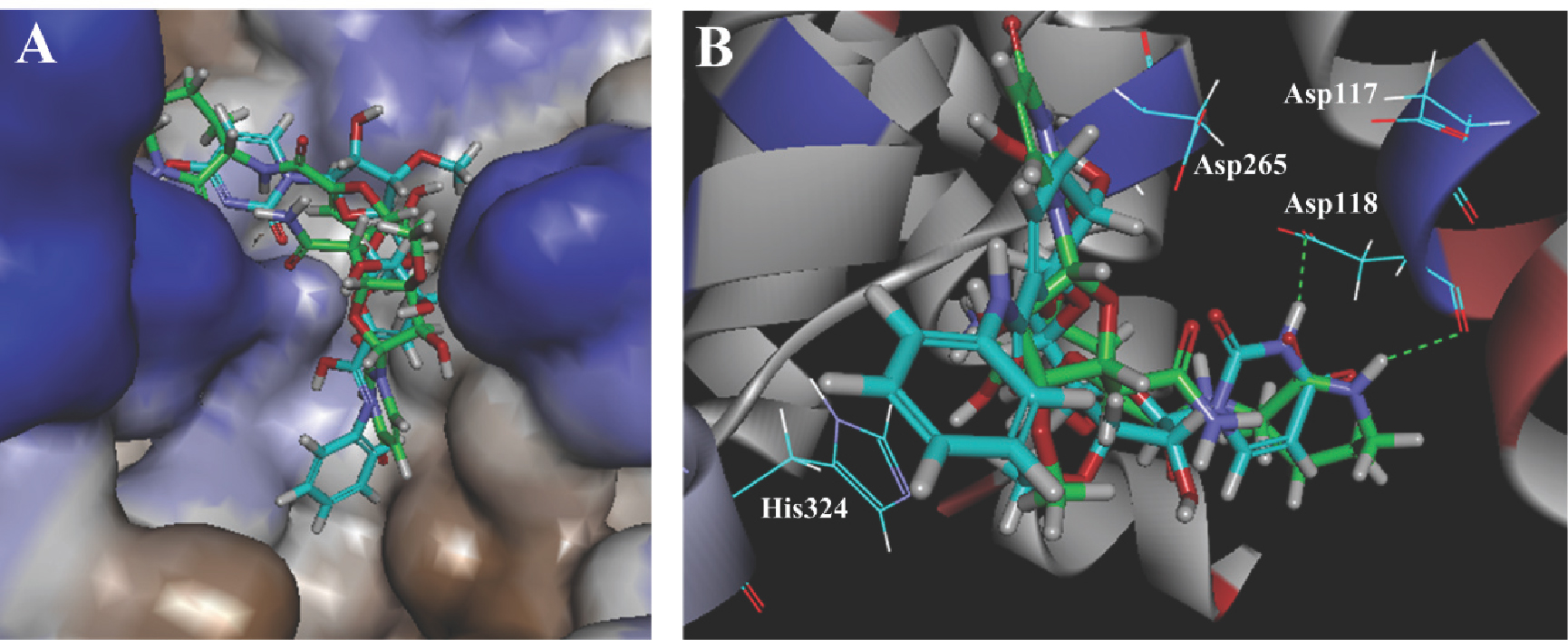

3.2 Docking analysis

The CDOCKER docking algorithm uses the CHARMm family of force fields and offers the advantages of full ligand flexibility (including bonds, angles, and dihedrals) and reasonable computation times [37]. Twenty binding configurations per ligand were obtained, and the configuration with the highest CDOCKER_INTERACTION_ ENERGY was taken as the ligand–receptor interaction, which was then compared manually. The most active compound 27 and capuramycin bound in similar conformations. The end of each entered the deep and narrow catalytic pocket (Figure 5A). This is consistent with the 3D-QSAR finding that a bulky group was disfavored there. In Figure 5B we see that each can form hydrogen bonds with Asp118, which is the key residue for catalysis.

Docking of capuramycin (green) and compound 27 (cyan) with MraY. (A) The protein is represented as a hydrophobicity surface complexed with capuramycin and compound 27. Brown and blue shades represent hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions respectively. (B) Docking of capuramycin and compound 27 with the active site. The H-bonds between MraY and the two compounds are shown as green dashed lines.

They have the high CDOCKER_INTERACTION_ENERGY of 81.54 and 88.45 kcal/mol respectively, which explains their greater affinities (IC50 = 12nM, 18nM) than the other derivatives.

Although compound 61 with medium potency has the highest -CDOCKER_INTERACTION_ENERGY, there is no precise correlation between this parameter and IC50, because experimental IC50 values depend on a number of events in addition to target inhibition.

3.3 Design of new molecules based on 3D-QSAR

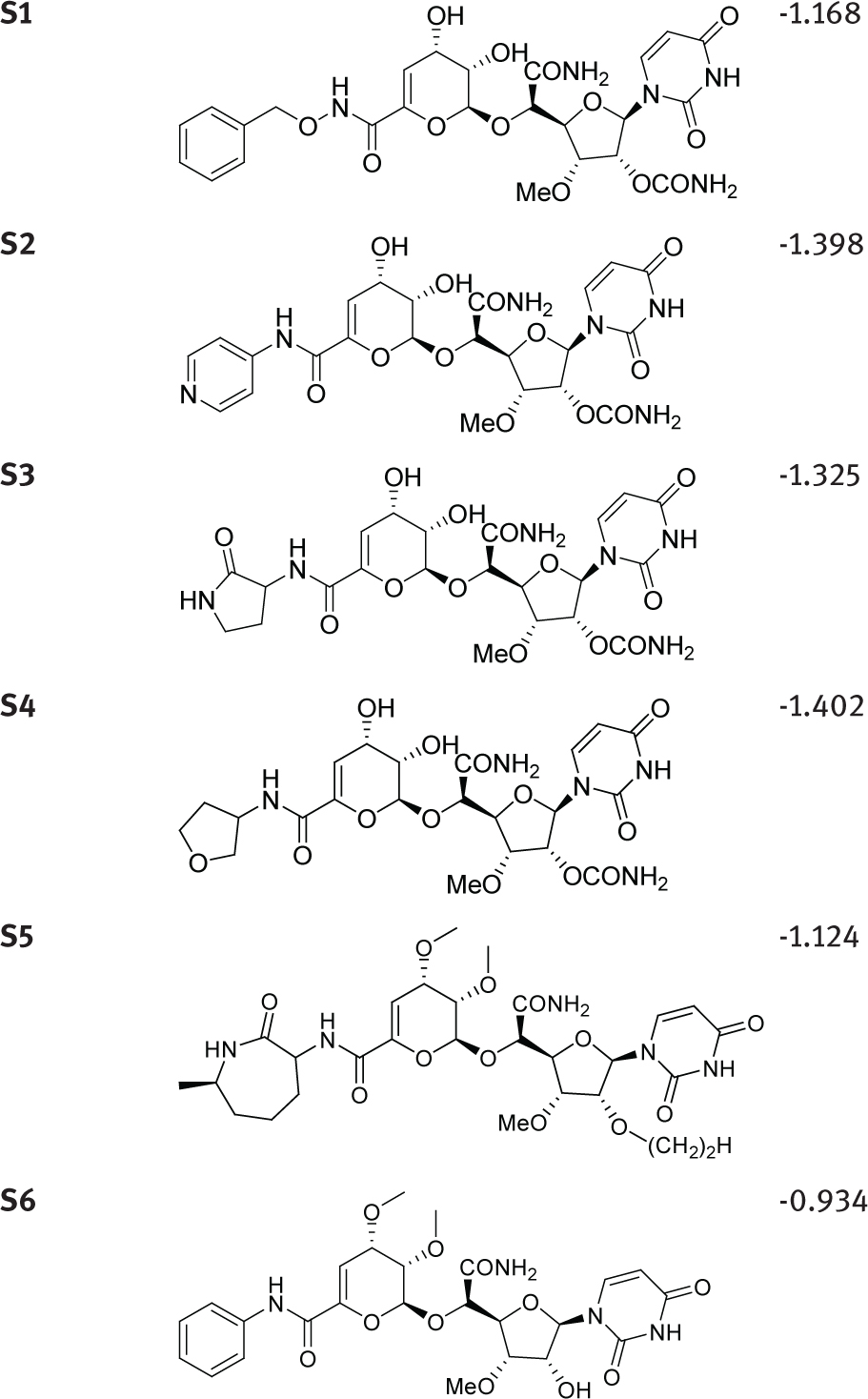

Based on the contour maps, the models were used to propose new capuramycin derivatives by substituent modification around the azepan-2-one (Table 2). Some modifications were also tried at the nucleoside 2’-OH and the sugar hydroxyl. These resulted in new capuramycin analogs with predicted improved activities. The activity may be further enhanced through modification.

New molecules designed based on the MFA contour.

| Compound | Structure | Predicted activity (pIC50) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

3.4 Synthesis of S1

All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received unless otherwise indicated. Reaction courses were monitored by LC-MS. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were taken on a Bruker spectrometer using TMS internal standard and D2O solvent. Mass spectra were measured on an Agilent 1100 series.

Procedure for the preparation of S1: (2R,3R,4R,5S)-5- ((S)-2-amino-1-(((2S,3S,4S)-6-((benzyloxy)carbamoyl)- 3,4-dihydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2- oxoethyl)-2-(2,4-dioxo-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-1(2H)- yl)-4- methoxytetrahydrofuran-3-yl carbamate

To a solution of A-503083F (52.5mg, 0.1mmol) in DMF (10ml), DIPEA (39mg, 0.3mmol), EDCI (28.75mg, 0.15mmol) and HOBT (13.5mg, 0.1mmol) were added. After stirring for 30min, o-benzylhydroxylamine (61.5mg, 0.5mmol) was added and the mixture stirred at room temperature overnight, after which the reaction mixture was poured into water (100ml), and extracted with EA (3 × 20ml). The aqueous phase was freeze-dried to obtain the crude reaction mixture. Further purification was performed by HPLC using a C-18 reverse-phase semi-preparative column, affording S1 as a white solid (15mg, 26%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 7.63 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.45-7.38 (m, 5H), 5.89 (dd, J = 2.5, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 5.86-5.81 (m, 2H), 5.28 (d, J=3.2 Hz, 1H), 5.18 (dd, J=5.3, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.89 (s, 2H), 4.60 (d, J=2.7 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (dd, J=4.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (dd, J=6.1, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 4.14-4.10 (m, 1H), 3.91 (t, J=5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.27 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O with methanol as standard) δ 172.5, 156.9, 150.9, 141.5, 140.4, 134.3, 129.6, 129.5, 129.1, 128.5, 109.9, 102.1, 98.8, 88.6, 81.6, 78.3, 77.5, 75.1, 73.3, 64.5, 61.5, 58.2. HRMS (ESI): C25H29N5O13+H+, Calc: 608.1835, Found: 608.1840.

3.5 Antimycobacterial activity

S1 was evaluated for in vitro activity against M. smegmatis MC2 155 and M. tuberculosis H37Rv according to the published method [39]. It had a significantly better MIC (7.7μM) than the parent 3 (60μM) against M. smegmatis MC2 155. It had relatively good anti-TB activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (15 μM), comparable to 2 (14 μM).

4 Conclusions

The 3D-QSAR models presented here are powerful enough to suggest improvement in capuramycin derivatives. By combining 3D-QSAR and molecular docking studies, capuramycin derivatives as MraY inhibitors can be summarized as follows: (1) a bulky and electropositive substitute at the azepan-2-one moiety disfavors activity; (2) small and electropositive substituents at the nucleoside 2’-OH improves bioactivity; (3) bulky substituents at the sugar hydroxyl may improve MraY inhibition. This information was used to design new capuramycin analogs with predicted activities higher than those used to derive the models. The synthetic compound S1 had relatively good anti-TB activity against both M. smegmatis MC2 155 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Thus, combined 3D-QSAR and docking studies can be used as a guideline to design and predict new and more potent capuramycin analogs for tuberculosis therapy.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 81321004 and 81761128016); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2016-12M-3-012 and 2016-12M-3-022); Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7164279); and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (IMBF201509).

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Levy S. B., Marshall B., Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses, NAT MED, 2004, 10, S122-129.10.1038/nm1145Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Alekshun M.N., Levy S. B., Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance, Cell, 2007, 128, 1037-1050.10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] van Heijenoort J., Recent advances in the formation of the bacterial peptidoglycan monomer unit. NAT PROD REP, 2001, 18, 503-519.10.1039/a804532aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Bugg T. D., Lloyd A.J., Roper D.I., Phospho-MurNAc- pentapeptide translocase (MraY) as a target for antibacterial agents and antibacterial proteins, Infectious disorders drug targets, 2006, 6, 85-106.10.2174/187152606784112128Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Bouhss A., Trunkfield A.E., Bugg T.D., Mengin-Lecreulx D., The biosynthesis of peptidoglycan lipid-linked intermediates, FEMS MICROBIOL REV, 2008, 32, 208-233.10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00089.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Bouhss A., Crouvoisier M., Blanot D., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Purification and characterization of the bacterial MraY translocase catalyzing the first membrane step of peptidoglycan biosynthesis, J BIOL CHEM, 2004, 279, 29974-29980.10.1074/jbc.M314165200Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Bouhss A., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Le Beller D., Van Heijenoort J., Topological analysis of the MraY protein catalysing the first membrane step of peptidoglycan synthesis, MOL MICROBIOL, 1999, 34, 576-585.10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01623.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Chung B.C., Zhao J., Gillespie R.A., Kwon D.Y., Guan Z., Hong J., et al., Crystal structure of MraY, an essential membrane enzyme for bacterial cell wall synthesis. Science, 2013, 341, 1012-1016.10.1126/science.1236501Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Muramatsu Y., Muramatsu A., Ohnuki T., Ishii M.M., Kizuka M., Enokita R., et al., Studies on novel bacterial translocase I inhibitors, A-500359s. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and structure elucidation of A-500359 A, C, D and G. J ANTIBIOT, 2003, 56, 243-252.10.1038/ja.2006.81Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Hotoda H., Daigo M., Furukawa M., Murayama K., Hasegawa C.A., Kaneko M., et al., Synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of capuramycin analogues. Part 2: acylated derivatives of capuramycin-related compounds, BIOORG MED CHEM LETT, 2003, 13, 2833-2836.10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00597-3Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Hotoda H., Furukawa M., Daigo M., Murayama K., Kaneko M., Muramatsu Y., et al., Synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of capuramycin analogues. Part 1: substitution of the azepan- 2-one moiety of capuramycin, BIOORG MED CHEM LETT, 2003, 13, 2829-2832.10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00596-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Roy K., Paul S., Docking and 3D QSAR studies of protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibitor 3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d][1,2,3] triazin-4-one derivatives, J MOL MODEL, 2010, 16, 137-153.10.1007/s00894-009-0528-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Yang G.F., Huang X., Development of quantitative structure- activity relationships and its application in rational drug design, CURR PHARM DESIGN, 2006,12, 4601-4611.10.2174/138161206779010431Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Thareja S., Aggarwal S., Bhardwaj T.R., Kumar M., Self-organizing molecular field analysis of 2,4-thiazolidinediones: A 3D-QSAR model for the development of human PTP1B inhibitors, EUR J MED CHEM, 2010, 45, 2537-2546.10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.02.042Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Wang F., Yang W., Shi Y., Le G., 3D-QSAR, molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies of a series of RORgammat inhibitors, J BIOMOL STRUCT DYN, 2014, 1-12.10.1080/07391102.2014.980321Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Wang J.F., Chou K.C., Insights from modeling the 3D structure of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamse and its binding interactions with antibiotic drugs, PLOS ONE, 2011, 6, e18414.10.1371/journal.pone.0018414Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Berman H.M., Battistuz T., Bhat T.N., Bluhm W.F., Bourne P.E., Burkhardt K., et al., The Protein Data Bank, ACTA CRYSTALLOGR D,2002, 58, 899-907.10.1107/S0907444902003451Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Westbrook J., Feng Z., Jain S., Bhat T.N., Thanki N., Ravichandran V., et al., The Protein Data Bank: unifying the archive, NUCLEIC ACIDS RES, 2002, 30, 245-248.10.1093/nar/30.1.245Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Ajala A.O., Okoro C.O., CoMFA and CoMSIA studies on fluorinated hexahydropyrimidine derivatives, BIOORG MED CHEM LETT, 2011, 21, 7392-7398.10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Aparoy P., Suresh G.K., Kumar Reddy K., Reddanna P., CoMFA and CoMSIA studies on 5-hydroxyindole-3-carboxylate derivatives as 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors: generation of homology model and docking studies, BIOORG MED CHEM LETT, 2011, 21, 456-462.10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.119Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Hirashima A., Morimoto M., Kuwano E., Eto M., Three-dimensional molecular-field analyses of octopaminergic agonists for the cockroach neuronal octopamine receptor, BIOORGAN MED CHEM, 2003, 11, 3753-3760.10.1016/S0968-0896(03)00313-4Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Fan Y., Shi L.M., Kohn K.W., Pommier Y., Weinstein J.N., Quantitative structure-antitumor activity relationships of camptothecin analogues: cluster analysis and genetic algorithm-based studies, J MED CHEM, 2001, 44, 3254-3263.10.1021/jm0005151Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Jackson P.L., Scott K.R., Southerland W.M., Fang Y.Y., Enaminones 8: CoMFA and CoMSIA studies on some anticonvulsant enaminones, BIOORGAN MED CHEM, 2009, 17, 133-140.10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Yi P., Fang X., Qiu M., 3D-QSAR studies of Checkpoint Kinase Weel inhibitors based on molecular docking, CoMFA and CoMSIA, EUR J MED CHEM, 2008, 43, 925-938.10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.06.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Srivastava V., Gupta S.P., Siddiqi M.I., Mishra B.N., 3D-QSAR studies on quinazoline antifolate thymidylate synthase inhibitors by CoMFA and CoMSIA models, EUR J MED CHEM, 2010, 45, 1560-1571.10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.12.065Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Chou K.C., Wei D.Q., Zhong W.Z., Binding mechanism of coronavirus main proteinase with ligands and its implication to drug design against SARS, BIOCHEM BIOPH RES CO, 2003, 308, 148-151.10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01342-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Du Q., Wang S., Wei D., Sirois S., Chou K.C., Molecular modeling and chemical modification for finding peptide inhibitor against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus main proteinase, ANAL BIOCHEM, 2005, 337, 262-270.10.1016/j.ab.2004.10.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Wang S.Q., Du Q.S., Huang R.B., Zhang D.W., Chou K.C., Insights from investigating the interaction of oseltamivir (Tamiflu) with neuraminidase of the 2009 H1N1 swine flu virus, BIOCHEM BIOPH RES CO,2009, 386, 432-436.10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Cai L., Wang Y., Wang J.F., Chou K.C., Identification of proteins interacting with human SP110 during the process of viral infections, MED CHEM, 2011, 7, 121-126.10.2174/157340611794859343Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Liao Q.H., Gao Q.Z., Wei J., Chou K.C., Docking and molecular dynamics study on the inhibitory activity of novel inhibitors on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), MED CHEM, 2011, 7, 24-31.10.2174/157340611794072698Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Wu G., Robertson D.H., Brooks C.L., 3rd, and Vieth, M., Detailed analysis of grid-based molecular docking: A case study of CDOCKER-A CHARMm-based MD docking algorithm, J COMPUT CHEM, 2003, 24, 1549-1562.10.1002/jcc.10306Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] McEneny-King A., Edginton A.N., Rao P.P., Investigating the binding interactions of the anti-Alzheimer’s drug donepezil with CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein, BIOORG MED CHEM LETT, 2015, 25, 297-301.10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.046Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Abuo-Rahma Gel D., Abdel-Aziz M., Farag N.A., Kaoud T.S., Novel 1-[4-(Aminosulfonyl)phenyl]-1H-1,2,4-triazole derivatives with remarkable selective COX-2 inhibition: design, synthesis, molecular docking, anti-inflammatory and ulcerogenicity studies, EUR J MED CHEM, 2014, 83, 398-408.10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.06.049Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Jug G., Anderluh M., Tomasic T., Comparative evaluation of several docking tools for docking small molecule ligands to DC-SIGN, J MOL MODEL, 2015, 21, 164.10.1007/s00894-015-2713-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Xiao J., Zhang S., Luo M., Zou Y., Zhang Y., Lai Y., Effective virtual screening strategy focusing on the identification of novel Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors, J Mol Graph Model, 2015, 60, 142-154.10.1016/j.jmgm.2015.05.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Rarey M., Kramer B., Lengauer T., Klebe G., A fast flexible docking method using an incremental construction algorithm, J MOL BIOL, 1996, 261, 470-489.10.1006/jmbi.1996.0477Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Shoichet B.K., Kuntz I. D., Protein docking and complementarity, J MOL BIOL, 1991, 221, 327-346.10.1016/0022-2836(91)80222-GSuche in Google Scholar

[38] Funabashi M., Yang Z., Nonaka K., Hosobuchi M., Fujita Y., Shibata T., et al., An ATP-independent strategy for amide bond formation in antibiotic biosynthesis, NAT CHEM BIOL, 2010, 6, 581-586.10.1038/nchembio.393Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Liu X., Jin Y., Cai W., Green K.D., Goswami A., Garneau-Tsodikova S., et al., A biocatalytic approach to capuramycin analogues by exploiting a substrate permissive N-transacylase CapW, ORG BIOMOL CHEM, 2016,14, 3956-3962.10.1039/C6OB00381HSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2017 Yuanyuan Jin et al.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Rare Coumarins Induce Apoptosis, G1 Cell Block and Reduce RNA Content in HL60 Cells

- Regular Articles

- Evaluation of the photocatalytic ability of a sol-gel-derived MgO-ZrO2 oxide material

- Regular Articles

- Extraction Methods for the Isolation of Isoflavonoids from Plant Material

- Regular Articles

- Micro and nanocomposites of polybutadienebased polyurethane liners with mineral fillers and nanoclay: thermal and mechanical properties

- Regular Articles

- Effect of pH on Structural, Magnetic and FMR Properties of Hydrothermally Prepared Nano Ni Ferrite

- Regular Articles

- Statistical approach to study of lithium magnesium metaborate glasses

- Regular Articles

- The effectiveness of biodrying waste treatment in full scale reactor

- Regular Articles

- Chemical comparison of the underground parts of Valeriana officinalis and Valeriana turkestanica from Poland and Kazakhstan

- Regular Articles

- Phytochemical Characterization and Biological Evaluation of the Aqueous and Supercritical Fluid Extracts from Salvia sclareoides Brot

- Regular Articles

- Recent Microextraction Techniques for Determination and Chemical Speciation of Selenium

- Regular Articles

- Compost leachate treatment using polyaluminium chloride and nanofiltration

- Regular Articles

- Facile and Effective Synthesis of Praseodymium Tungstate Nanoparticles through an Optimized Procedure and Investigation of Photocatalytic Activity

- Regular Articles

- Computational Study on Non-linear Optical and Absorption Properties of Benzothiazole based Dyes: Tunable Electron-Withdrawing Strength and Reverse Polarity

- Regular Articles

- Comparative sorption studies of chromate by nano-and-micro sized Fe2O3 particles

- Regular Articles

- Recycling Monoethylene Glycol (MEG) from the Recirculating Waste of an Ethylene Oxide Unit

- Regular Articles

- Antimicrobial activity and thiosulfinates profile of a formulation based on Allium cepa L. extract

- Regular Articles

- The effect of catalyst precursors and conditions of preparing Pt and Pd-Pt catalysts on their activity in the oxidation of hexane

- Regular Articles

- Platinum and vanadate Bioactive Complexes of Glycoside Naringin and Phenolates

- Regular Articles

- Antimicrobial sesquiterpenoids from Laurencia obtusa Lamouroux

- Regular Articles

- Comprehensive spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, 1H and 13C NMR) identification and computational studies on 1-acetyl-1H-indole-2,3-dione

- Regular Articles

- A combined experimental and theoretical study on vibrational and electronic properties of (5-methoxy-1H-indol-1-yl)(5-methoxy-1H-indol-2-yl)methanone

- Regular Articles

- Erratum to: Analysis of oligonucleotides by liquid chromatography with alkylamide stationary phase

- Regular Articles

- Non-isothermal Crystallization, Thermal Stability, and Mechanical Performance of Poly(L-lactic acid)/Barium Phenylphosphonate Systems

- Regular Articles

- Vortex assisted-supramolecular solvent based microextraction coupled with spectrophotometric determination of triclosan in environmental water samples

- Regular Articles

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O,O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

- Regular Articles

- Evaluation of temporary seasonal variation of heavy metals and their potential ecological risk in Nzhelele River, South Africa

- Regular Articles

- Synthesis, characterization, second and third order non-linear optical properties and luminescence properties of 1,10-phenanthroline-2,9-di(carboxaldehyde phenylhydrazone) and its transition metal complexes

- Regular Articles

- Spectrodensitometric simultaneous determination of esomeprazole and domperidone in human plasma

- Regular Articles

- Computer-aided drug design of capuramycin analogues as anti-tuberculosis antibiotics by 3D-QSAR and molecular docking

- Regular Articles

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal degradation and urease inhibitory studies of the new hydrazide based Schiff base ligand 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-{[(E)-(2-hydroxyphenyl)methylidene]amino}-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one

- Regular Articles

- Quaternary salts derived from 3-substituted quinuclidine as potential antioxidative and antimicrobial agents

- Regular Articles

- Bio-concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along eastern coast of the Red Sea

- Regular Articles

- Quantitative Investigation of Roasting-magnetic Separation for Hematite Oolitic-ores: Mechanisms and Industrial Application

- Regular Articles

- Photobleaching characteristics of α-(8-quinolinoxy) zinc phthalocyanine, a new type of amphipathic complex

- Regular Articles

- Methane dry reforming over Ni catalysts supported on Ce–Zr oxides prepared by a route involving supercritical fluids

- Regular Articles

- Thermodynamic Compatibility, Crystallizability, Thermal, Mechanical Properties and Oil Resistance Characteristics of Nanostructure Poly (ethylene-co-methyl acrylate)/Poly(acrylonitrile-co-butadiene) Blends

- Regular Articles

- The crystal structure of compositionally homogeneous mixed ceria-zirconia oxides by high resolution X-ray and neutron diffraction methods

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Properties of the filtrate from treatment of pig manure by filtration method

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Monitoring content of cadmium, calcium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium and manganese in tea leaves by electrothermal and flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Topical Issue on Catalysis

- Application of screen-printed carbon electrode modified with lead in stripping analysis of Cd(II)

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Burdock (Arctium lappa) Leaf Extracts Increase the In Vitro Antimicrobial Efficacy of Common Antibiotics on Gram-positive and Gram-negative Bacteria

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- A survey of bacterial, fungal and plant metabolites against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae), the vector of yellow and dengue fevers and Zika virus

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- ‘Capiture’ plants with interesting biological activities: a case to go

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Volatile terpenoids as potential drug leads in Alzheimer’s disease

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Essential Oils as Immunomodulators: Some Examples

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Phenolic profiling and therapeutic potential of local flora of Azad Kashmir; In vitro enzyme inhibition and antioxidant

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Chemical profile, antioxidant activity and cytotoxic effect of extract from leaves of Erythrochiton brasiliensis Nees & Mart. from different regions of Europe

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Rare Coumarins Induce Apoptosis, G1 Cell Block and Reduce RNA Content in HL60 Cells

- Regular Articles

- Evaluation of the photocatalytic ability of a sol-gel-derived MgO-ZrO2 oxide material

- Regular Articles

- Extraction Methods for the Isolation of Isoflavonoids from Plant Material

- Regular Articles

- Micro and nanocomposites of polybutadienebased polyurethane liners with mineral fillers and nanoclay: thermal and mechanical properties

- Regular Articles

- Effect of pH on Structural, Magnetic and FMR Properties of Hydrothermally Prepared Nano Ni Ferrite

- Regular Articles

- Statistical approach to study of lithium magnesium metaborate glasses

- Regular Articles

- The effectiveness of biodrying waste treatment in full scale reactor

- Regular Articles

- Chemical comparison of the underground parts of Valeriana officinalis and Valeriana turkestanica from Poland and Kazakhstan

- Regular Articles

- Phytochemical Characterization and Biological Evaluation of the Aqueous and Supercritical Fluid Extracts from Salvia sclareoides Brot

- Regular Articles

- Recent Microextraction Techniques for Determination and Chemical Speciation of Selenium

- Regular Articles

- Compost leachate treatment using polyaluminium chloride and nanofiltration

- Regular Articles

- Facile and Effective Synthesis of Praseodymium Tungstate Nanoparticles through an Optimized Procedure and Investigation of Photocatalytic Activity

- Regular Articles

- Computational Study on Non-linear Optical and Absorption Properties of Benzothiazole based Dyes: Tunable Electron-Withdrawing Strength and Reverse Polarity

- Regular Articles

- Comparative sorption studies of chromate by nano-and-micro sized Fe2O3 particles

- Regular Articles

- Recycling Monoethylene Glycol (MEG) from the Recirculating Waste of an Ethylene Oxide Unit

- Regular Articles

- Antimicrobial activity and thiosulfinates profile of a formulation based on Allium cepa L. extract

- Regular Articles

- The effect of catalyst precursors and conditions of preparing Pt and Pd-Pt catalysts on their activity in the oxidation of hexane

- Regular Articles

- Platinum and vanadate Bioactive Complexes of Glycoside Naringin and Phenolates

- Regular Articles

- Antimicrobial sesquiterpenoids from Laurencia obtusa Lamouroux

- Regular Articles

- Comprehensive spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, 1H and 13C NMR) identification and computational studies on 1-acetyl-1H-indole-2,3-dione

- Regular Articles

- A combined experimental and theoretical study on vibrational and electronic properties of (5-methoxy-1H-indol-1-yl)(5-methoxy-1H-indol-2-yl)methanone

- Regular Articles

- Erratum to: Analysis of oligonucleotides by liquid chromatography with alkylamide stationary phase

- Regular Articles

- Non-isothermal Crystallization, Thermal Stability, and Mechanical Performance of Poly(L-lactic acid)/Barium Phenylphosphonate Systems

- Regular Articles

- Vortex assisted-supramolecular solvent based microextraction coupled with spectrophotometric determination of triclosan in environmental water samples

- Regular Articles

- Investigation on Two Compounds of O,O’-dithiophosphate Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors for Q235 Steel in Hydrochloric Acid Solution

- Regular Articles

- Evaluation of temporary seasonal variation of heavy metals and their potential ecological risk in Nzhelele River, South Africa

- Regular Articles

- Synthesis, characterization, second and third order non-linear optical properties and luminescence properties of 1,10-phenanthroline-2,9-di(carboxaldehyde phenylhydrazone) and its transition metal complexes

- Regular Articles

- Spectrodensitometric simultaneous determination of esomeprazole and domperidone in human plasma

- Regular Articles

- Computer-aided drug design of capuramycin analogues as anti-tuberculosis antibiotics by 3D-QSAR and molecular docking

- Regular Articles

- Synthesis, characterization, thermal degradation and urease inhibitory studies of the new hydrazide based Schiff base ligand 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-{[(E)-(2-hydroxyphenyl)methylidene]amino}-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one

- Regular Articles

- Quaternary salts derived from 3-substituted quinuclidine as potential antioxidative and antimicrobial agents

- Regular Articles

- Bio-concentration of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the grey Mangrove (Avicennia marina) along eastern coast of the Red Sea

- Regular Articles

- Quantitative Investigation of Roasting-magnetic Separation for Hematite Oolitic-ores: Mechanisms and Industrial Application

- Regular Articles

- Photobleaching characteristics of α-(8-quinolinoxy) zinc phthalocyanine, a new type of amphipathic complex

- Regular Articles

- Methane dry reforming over Ni catalysts supported on Ce–Zr oxides prepared by a route involving supercritical fluids

- Regular Articles

- Thermodynamic Compatibility, Crystallizability, Thermal, Mechanical Properties and Oil Resistance Characteristics of Nanostructure Poly (ethylene-co-methyl acrylate)/Poly(acrylonitrile-co-butadiene) Blends

- Regular Articles

- The crystal structure of compositionally homogeneous mixed ceria-zirconia oxides by high resolution X-ray and neutron diffraction methods

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Properties of the filtrate from treatment of pig manure by filtration method

- Topical Issue on Agriculture

- Monitoring content of cadmium, calcium, copper, iron, lead, magnesium and manganese in tea leaves by electrothermal and flame atomizer atomic absorption spectrometry

- Topical Issue on Catalysis

- Application of screen-printed carbon electrode modified with lead in stripping analysis of Cd(II)

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Burdock (Arctium lappa) Leaf Extracts Increase the In Vitro Antimicrobial Efficacy of Common Antibiotics on Gram-positive and Gram-negative Bacteria

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- A survey of bacterial, fungal and plant metabolites against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae), the vector of yellow and dengue fevers and Zika virus

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- ‘Capiture’ plants with interesting biological activities: a case to go

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Volatile terpenoids as potential drug leads in Alzheimer’s disease

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Essential Oils as Immunomodulators: Some Examples

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Phenolic profiling and therapeutic potential of local flora of Azad Kashmir; In vitro enzyme inhibition and antioxidant

- Topical Issue on Research for Natural Bioactive Products

- Chemical profile, antioxidant activity and cytotoxic effect of extract from leaves of Erythrochiton brasiliensis Nees & Mart. from different regions of Europe