Abstract

Objectives

Nonenzymatic biosensor-based-conductive polymers like polyaniline are highly electrochemically stable, cheap, and easy to synthesize biosensors, which is the main objective of research as well as testing applied in different pH conditions to get optimum sensitivity.

Methods

A nonenzymatic glucose biosensor based on polyaniline was electrochemically deposited on a glassy carbon electrode; the cyclic voltammetry under range applied voltage −0.2 to 1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl was employed to synthesize the biosensor electrode.

Results

The polyaniline biosensor electrode properties were characterized, and the morphology surface photographic confirmed mesoporous architecture with many accessible pores, while chemical bonding analysis confirmed the synthesis of polyaniline. The initial investigation examined the pH levels of phosphate-buffered saline, including 5, 5.5, 6, and 6.5. The cyclic voltammetry measurement revealed that the pH=5.5 provides excellent sensitivity toward glucose detection. The sensitivity of pH=5.5 is 68.7 μA mM−1 cm−2, and the low detection limit is 1 µM.

Conclusions

The findings above indicate that the biosensor could be an excellent candidate for application in electrochemical glucose sensing under pH=5.5 conditions of phosphate-buffered saline.

Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic disease that occurs when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or is less effective. Diabetes is a condition where the level of glucose in the blood is too high, which can be hazardous to health and lead to death [1], 2]. Daily monitoring of the glucose level is so important for diabetes. Various techniques were used to measure the glucose level in the blood, including enzymatic and nonenzymatic techniques [3]. The enzymatic technique is one of the old techniques, cost, and non-long-term stability used glucose oxidase (GOx), which electrochemically converts glucose into gluconic acid and H2O2 [4]. The nonenzymatic technique was released by the direct electrochemical oxidation of glucose without glucose oxidase, which is an inexpensive and long-term stable technique to measure glucose [5], [6], [7]. The nonenzymatic technique usually uses electrode-based noble metals or metal oxide because of its excellent sensitivity toward glucose detection. However, noble metals (bimetallic or alloy) are expensive to use in daily monitoring, while nanomaterials-based metal oxide requires expensive equipment to prepare biosensor electrodes [7], [8], [9]. Recently, conductive polymers like polyaniline, polypyrrole, and polythiophene were used to fabricate electrochemical biosensors due to their high sensitivity and selectivity [10], [11], [12], [13].

Polyaniline (PANI) was intensively studied because of its unique electrical, electro-optical, and electrochemical properties, such as electrochemical synthesis and long-term stability, as well as flexibility.

Different parameters can influence the sensitivity of biosensors like nanostructure and nanocomposite. Nanostructured materials were synthesized with different shapes, such as nanoparticles, nanofibers, nanotubes, and mesoporous [14], [15], [16]. Herein, a surface area can influence biosensor detection. The large surface area was achieved by mesoporous nanostructure; consequently, high active sites were generated on the biosensor surface [17], [18], [19]. Moreover, the active sites on the biosensor surface are highly dependent on pH electrolytes [20]. The glucose oxidation can only occur via the chemisorption of glucose, producing gluconic- δ-lactone, which is further oxidized into gluconic acid via various reaction pathways depending on the pH. Based on the previous reports, most biosensors of glucose detection were studied under alkaline conditions. However, different pH values were rarely studied for biosensor-based polyaniline electrodes [21], 22]. Nevertheless, almost all glucose biosensors were applied in vitro only due to the use of alkaline electrolytes. However, wearable biosensor needs pH=7.4 for human blood which is still under challenge.

The polyaniline with chemical stability under a wide range of pH values allows charge transfer at the interface surface between biomaterials and polyaniline electrodes. There are two processes to understand the mechanism of polyaniline biosensors. In the first process, glucose should be adsorption on polyaniline. Secondly, for the charge transfer to oxidize glucose, electrocatalysis needs high active sites, which are normally provided by a porous surface.

Based on the above considerations, polyaniline can offer selectivity adsorption toward glucose biomaterial and a good electrocatalyst for directly oxidizing glucose. This study has been adopted to optimize the maximum sensitivity of polyaniline biosensors by controlling the pH of phosphate-buffered saline electrolytes. The biosensor glucose was constructed from the mesoporous architecture of polyaniline film on the glassy carbon electrode. The polyaniline film was characterized by different techniques to study crystallinity, chemical bonding and morphology. The biosensor was investigated under pH values 5, 5.5, 6, and 6.5. The excellent sensitivity of pH value was 5.5, and are good as anti-interface materials such as Uric acid, Ascorbic acid, and dopamine acid.

Chemicals and methods

Chemicals

Aniline (C6H7N, Mol. wt. 93.13) was used as a raw monomer, and sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was utilized in electrochemical synthesis. The phosphate buffer saline solutions of Monobasic sodium phosphate (NaH2PO4) and Dibasic sodium phosphate (Na2HPO4) were applied in different weight percentages to adjust the pH level of the prepared electrolyte. Glucose powder was employed to evaluate biosensor performance. Uric acid (UA), Ascorbic acid (AA), and dopamine acid (DA) were used as anti-interface materials. All the chemical materials were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used in this research study without any purification. Fluorine-doped tin oxide substrates (FTO), which are transparent conductive material on glass, were purchased from MTI corporation.

Preparation of biosensor electrode

The biosensor electrode was electrochemically prepared from a solution containing sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 1 M) and distilled water in a volumetric ratio (20:100 mL), and then (2 mL) of Aniline was slowly dropped into the previous solution [23]. Three electrode systems were used in these experiments. The glassy carbon electrode (GC) 0.2 cm diameter and 0.31 cm2 area was used as a working electrode. GC electrode was polished on the micro cloth pad with alumina powder (Al2O3, 300 nm), rinsed with distilled water, and then dried before use. A platinum wire electrode (Pt) was employed as a counter electrode. A silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode was utilized as a reference electrode (RE). Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) was performed at the potential range (−0.2 to 1.2 mV) repeated 5 times and a scan rate of 50 mV/s. A black-greenish thin film was gradually grown on the GC electrode. In the same method above, it has prepared a polyaniline thin film on FTO glass for absorption spectra and crystalline test.

Preparation of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) electrolyte

Phosphate buffered saline electrolyte (PBS, 0.1 M) with different pH values were prepared from NaH2PO4 (1 M) and Na2HPO4 (1 M) solution. The based Na2HPO4 solution was dropped to the acidic solution of NaH2PO4 to control the desired pH level of 5, 5.5, 6, and 6.5 via pH meter.

Preparation of glucose solution

The glucose solution was prepared in two groups, the first group was prepared by adding low concentration (0–5) µM of glucose powder to PBS electrolyte. The second group was prepared by adding (0–5) mM of glucose powder to PBS electrolyte.

Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD, Shimadzu, 6000) was used to determine the phase and composition of the polyaniline film. Electron Microscopy (SEM, Tescan, Vega II) was used to examine the morphologies and microstructures of the polyaniline film. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, Shimadzu, IRAffinity-1S) was used to obtain the spectra of polyaniline film using wavelengths ranging from (400–2,000 cm−1).

Biosensor test

The sensitivity is the most important parameter to evaluate the biosensor. Any change in biomaterial concentration, such as glucose, uric acid, and ascorbic acid in liquid, corresponds change in electrical response.

DY2300 (Digi-Ivy, Inc) Potentiostat/Galvanostat was used for electro electropolymerization of polyaniline as a thin film on the GC electrode by CV. The same procedure and three electrodes system were used as mentioned in the section on the preparation of biosensor electrodes. The potential range between (−0.2 to 0.6 V) and five cyclical numbers at scan rates 50 mV/s were applied for different concentrations of glucose solution with 0–10 µM, 0–5 mM. In addition, the CV was carried out with various scan rates of 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 mV/s. The biosensor measurements were carried out for four different pH electrolytes, and then repeated test was repeated 3 times for each glucose concentration of 0–5 mM.

Results and discussion

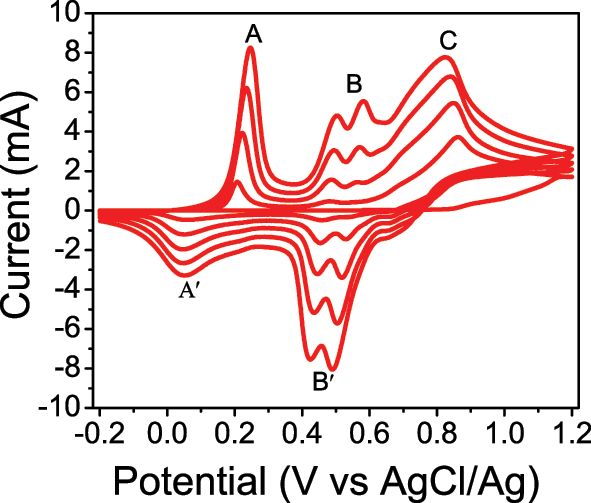

Polyaniline (PANI) was deposited on the GC electrode surface by a potentiodynamic method. The sweep voltage was −0.2 to 1.2 V vs. AgCl/Ag, and the scan rate voltage was 50 mV/s. The CV finding of PANI shows three distinct anodic current peaks (oxidation reaction) and two cathodic current peaks (reduction reaction), as illustrated in Figure 1. The first oxidation/reduction peak A/A′ between (0.2–0.3 V) represents the transformation from the reduced leucoemeraldine state to the partly oxidized emeraldine state. The second oxidation/reduction peak B/B′ has occurred between 0.4 and 0.6 V. This change is attributed to the transition from the reduced leucoemeraldine state to the fully oxidized pernigraniline state. The last oxidation peak (C) was observed at the potential range of 0.8 and 1 V with non-reversible cycles, indicating oxidation of an aniline monomer, which initiates the electropolymerization process. The same results were shown in previous studies [24], [25], [26].

Cyclic voltammogram of glassy carbon electrode in (H2SO4, 1 M) and distilled water in volume ratio (20:100 mL), and scan rate: = 50 mV s−1.

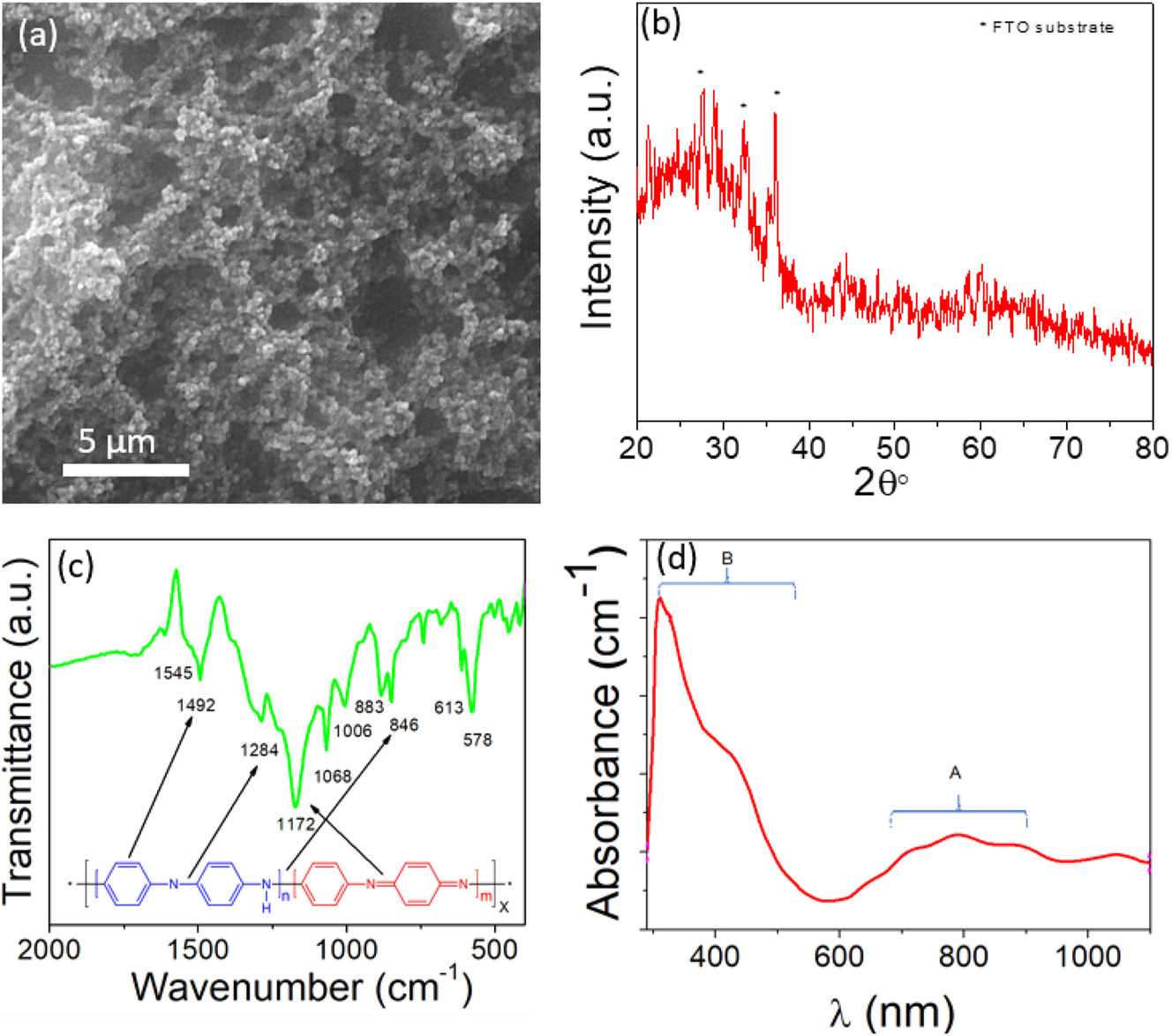

The biosensor’s sensitivity is highly dependent on its morphology, which can be obtained by using SEM. Figure 2a shows the SEM image of the polyaniline after being deposited on the GC electrode. The morphology of polyaniline film shows a homogeneity surface and a porous nanoarchitecture.

The synthesized polyaniline was characterized by using different techniques, (a) Morphology of polyaniline film grown on glassy carbon electrode by electrochemical technique. (b) XRD spectra. (c) FTIR spectra. (d) Absorbance spectra of polyaniline.

Nanoarchitectures take significant advantage, providing more surface area, and consequently, more active site reacts with biomaterials in solution. Therefore, it is expected that the porous nanoarchitecture has excellent performance sensitivity toward biomaterials [27], 28].

Figure 2b illustrates the XRD analysis of polyaniline film over an angular diffraction ranging between 10 and 80°. The polyaniline film was initially electropolymerized on the FTO substrate to obtain a large surface area for the XRD instrument. The electropolymerization of polyaniline revealed semi-crystallinity, which is related to the distinct nature of polyaniline. The prepared polyaniline film was confirmed by XRD, which shows the semi-crystallinity of polyaniline around 2θ=20–30°, which agreed with the previous studies [29], 30]. The other peaks are related to the FTO substrate. However, further identification is required to investigate product quality.

The FTIR was used to acquire the spectra of polyaniline film, as shown in Figure 2c. The main distinct peaks were obtained at wavenumber 1,545 and 1,492 cm−1, which are related to the stretching vibration of the C=C bond in quinoid and benzenoid rings, respectively. The peaks at 1,284 and 1,172 cm−1 are attributed to the C–N and C=N bond stretching of the secondary aromatic amine. Furthermore, the peaks at wavenumber 883 and 846 cm−1 are related to the out-of-plane deformation of C–H in the 1,4-disubstituted benzene ring. The other peaks are related to the C–C and C–H bond modes of the aromatic ring [31], 32].

In addition, the UV–vis spectroscopy was examined to identify the absorbance spectra of polyaniline. Figure 2d depicts the absorbance spectra exhibited by two separate broadening peaks, A and B. The A peak at 700–900 nm indicates excitation absorption of the quinoid rings, whereas the B peak at 300–500 nm is assigned to the π-π* transition of the benzenoid rings. The shoulder peak observed at 434 nm is ascribed to the polaron formation. This result is in agreement with previous studies [33], 34].

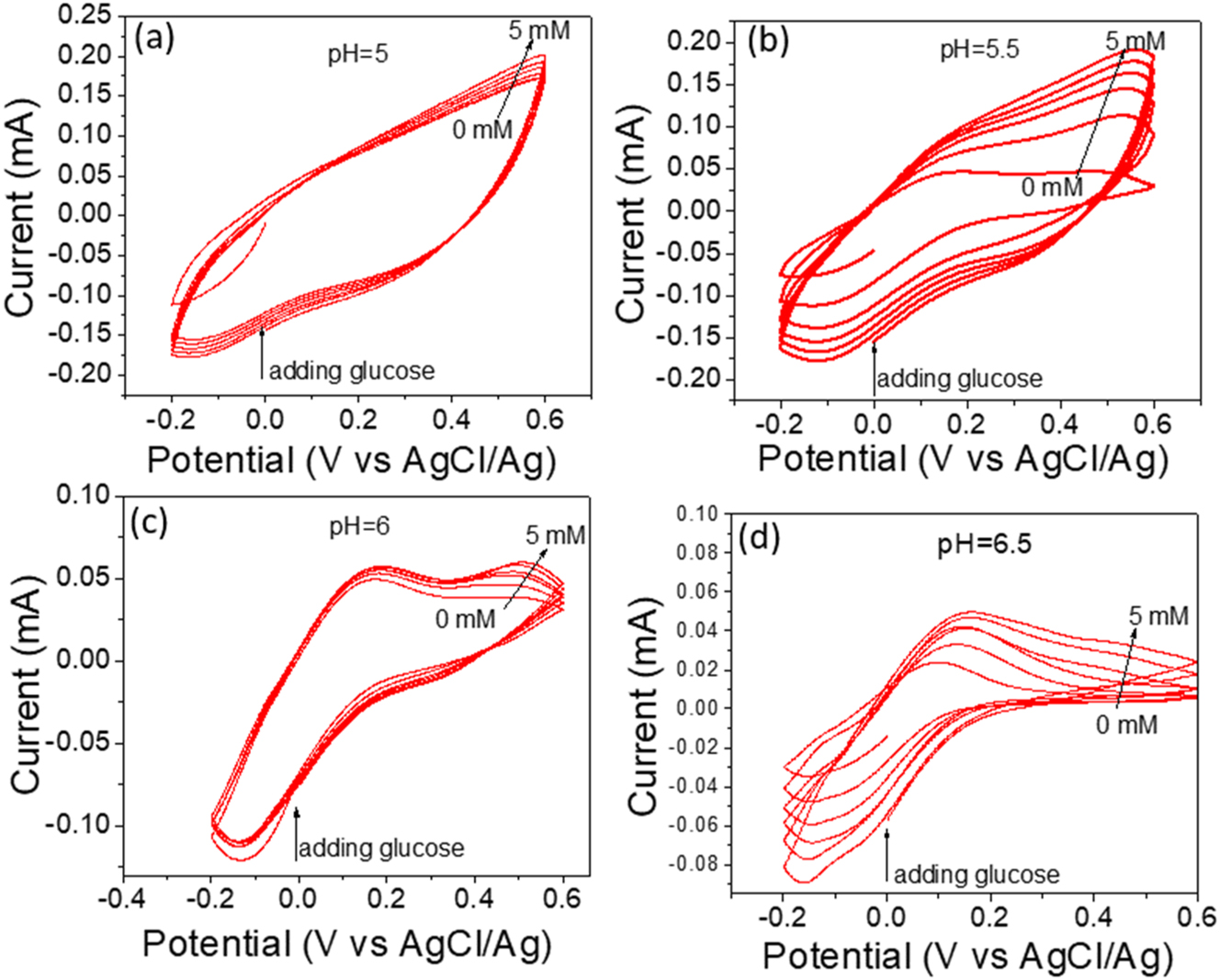

The most essential electrochemical technique for measuring current as a function of applied potential is CV. Depending on the accuracy of an applied potential, the redox of chemical substances in the electrolyte can react with the electrode. Therefore, it is detectable through the oxidation or reduction of biomarkers at a specific applied potential. The purpose of this study is to increase the sensitivity of PANI biosensors by regulating the pH of PBS electrolytes. Figure 3 depicts the CV of a PANI biosensor in PBS electrolyte with 0–5 mM glucose concentration and pH values of 5, 5.5, 6, and 6.5. Figure 3a shows the CV of PANI at pH=5 since the current increased gradually when the glucose concentration increased from 0–5 mM. The oxidation reaction of glucose converted to gluconic acid at 0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl, while the reduction reaction peak is −0.15 V vs. Ag/AgCl. The oxidation and reduction reaction displayed a reversible CV at pH=5.5, which is preferred in electrochemical biosensors to avoid interface biomaterials that appear at the oxidation potential of 0.1–0.6 V, such as ascorbic acid at 0.18 V [35] and uric acid at 0.35 V [36] against Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode. The reduction peak offers additional data to characterize glucose on two sides: oxidation and reduction peaks [37].

CV of glucose detection under different pH values, (a) 5, (b) 5.5, (c) 6, and (d) 6.5. The electrolyte solution is phosphate buffered saline (0.1 M). The scan rate was 50 mV/s.

The fully symmetric cathodic and anodic currents increased when the pH was adjusted to 5.5, as shown in Figure 3b. This increase can be attributed to the activation of a functional group located on the surface of the polyaniline. The oxidation peak of glucose at pH=6 is more prominently displayed in Figure 3c compared to the peak observed at pH=5.5 in Figure 3b. Meanwhile, the level of sensitivity diminished. Furthermore, Figure 3d shows the CV of PANI at pH=6.5, which displayed a low oxidation reaction. All of the above results are related to the electrocatalytic activity of functional groups on polyaniline surfaces that are activated at different pH levels.

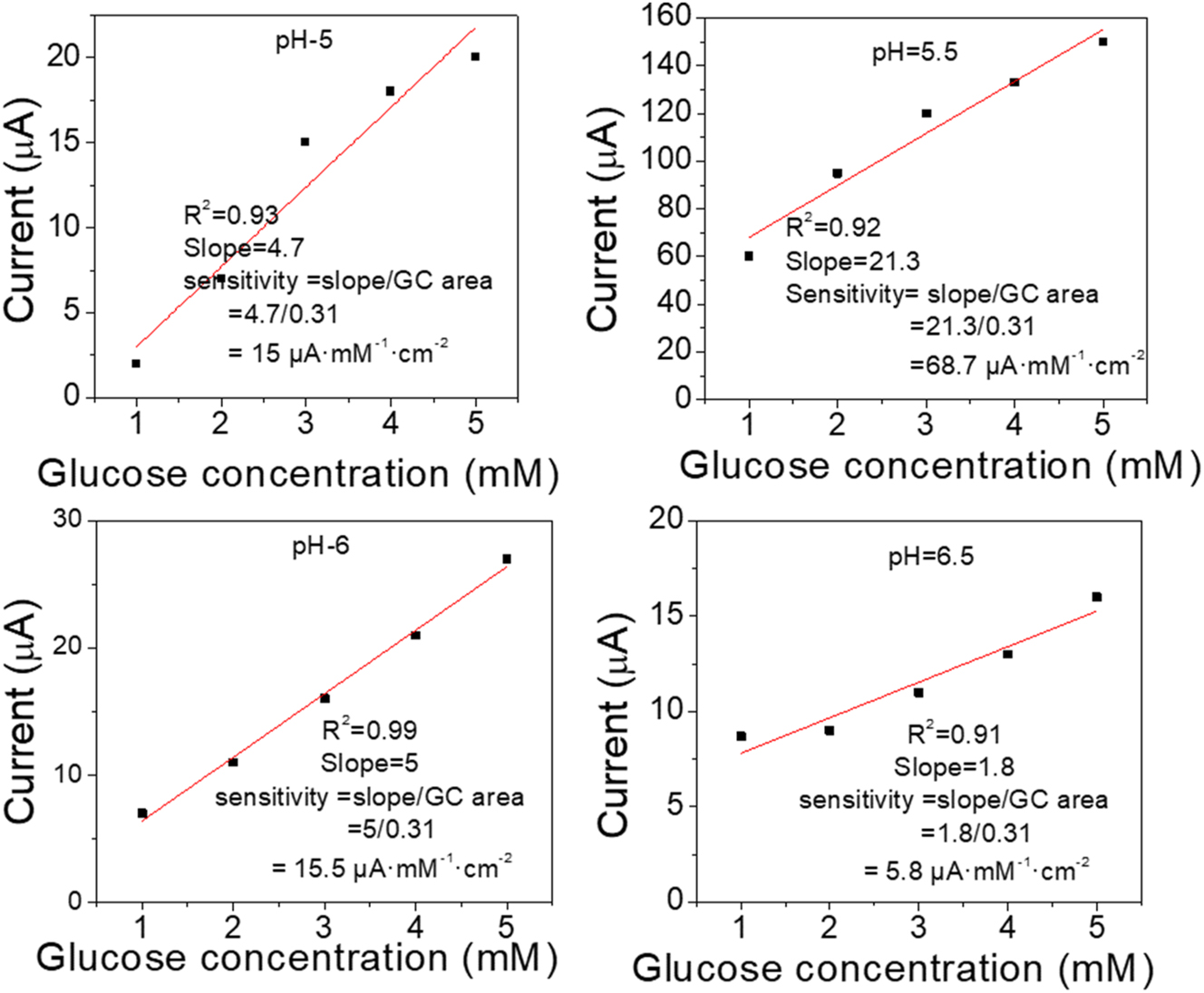

The linearity of CV was clarified in Figure 4, which represents the relation between glucose concentration and current. From the slopes, the maximum sensitivity obtained at pH=5.5 is 68.7 μA mM−1 cm−2, while the sensitivities at pH 5, 6, and 6.5 are 15, 15.5, and 5.8 μA mM−1 cm−2, respectively. Thus, the sensitivity of the biosensor depends on the pH value, which can activate the functional groups on the polyaniline’s surface.

The linearity of CV vs. concentration of glucose under different pH values, (a) 5, (b) 5.5, (c) 6, (d) 6.5, the electrolyte solution is phosphate buffered saline (0.1 M), the applied potential is 0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

Different surface nanostructures, such as nanowires, nanorods, nanotubes, and nanoporous, are essential surface modifiers [38] for polyaniline porous nanoarchitecture as shown in Figure 2a, which can increase its characteristics by making the high interfacial area between PANI and its environment. Therefore, it facilitates electron transfer between the reduction center of glucose and the polyaniline surface. Thus, a surface modifier investigation was conducted. GC electrode was investigated before and after the deposit of polyaniline, as the same procedure before, under pH=5.5; the scan rate was 50 mV/s, and glucose concentration was 5 mM. It was observed, as shown in Figure S1, that there was a large difference in sensitivity. GC electrode with deposit polyaniline shows higher sensitivity compared with GC electrode only, indicating deposited polyaniline on GC produced an excellent surface modifier.

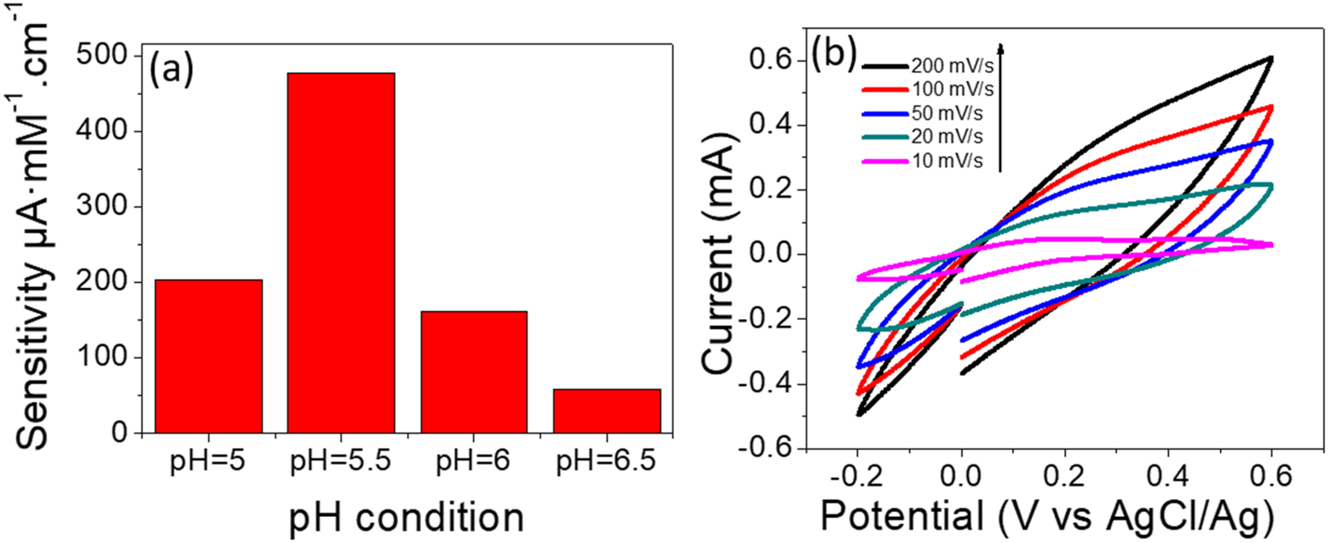

Figure 5a, reveals the relation between the sensitivity of biosensors and the pH of PBS electrolyte. The optimum sensitivity was obtained at pH=5.5 compared with other pH electrolytes. Further parameters, such as scan rate were carried out under different scan rates. Figure 5b shows the potential vs. the current at pH=5.5 with various scan rates of 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 mV/s. The sensitivity exhibited a linear proportionality with increasing the scan rate and reversible CV, indicating the glucose diffusion on the polyaniline surface and resulting in a higher current. These results obey the diffusion-controlled process.

The sensistivity of polyaniline biosensor, (a) the bar chart shows relation between the sensitivity of sensor vs. pH electrolyte. (b) CV curves of glucose detection at different scan rates under pH = 5.5 and PBS (0.1 M).

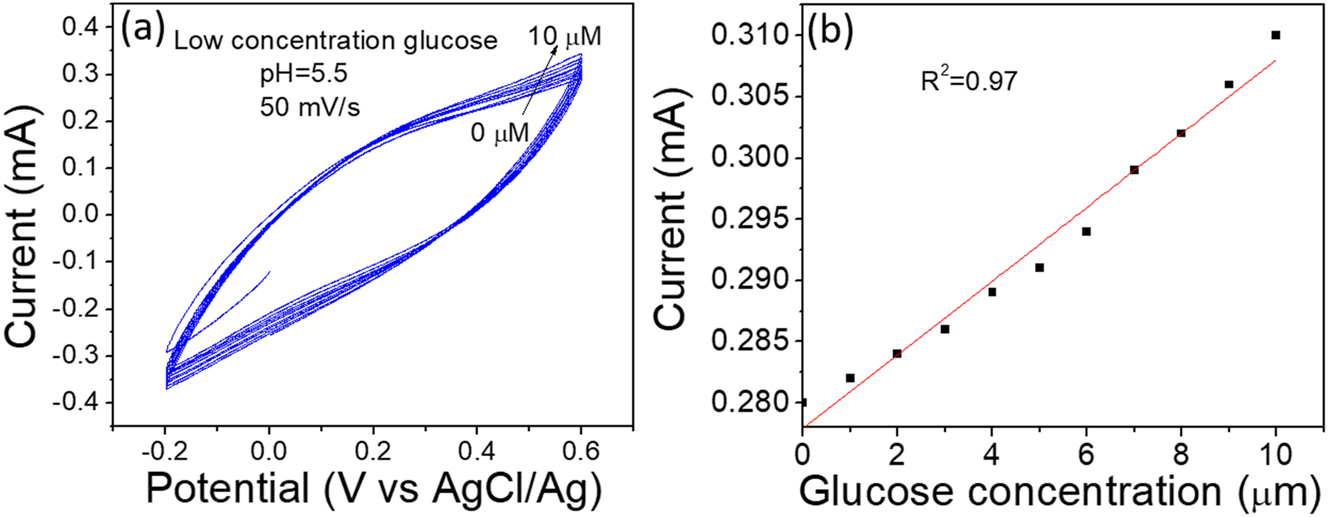

The low concentration of glucose (0–10 µM), the limit of detection was carried out. Figure 6a and b shows the current increased linearity with increasing glucose concentration, indicating stable and reliable detection for biological species. In comparison with previous studies, some details have been listed in Table 1. This work shows a reasonable sensitivity of 68.7 μA mM−1 cm−2, compared with composite materials under pH=5.5 acidic medium while the linearity is 1–5 mM and LOD is 1 µM. In the present study, the biosensor was prepared from polyaniline by electrochemical method. As a result, low cost, easy synthesis, and mechanical flexibility can be applied as biosensors for glucose levels in the blood. However, the pH of human blood is 7.4; therefore, it needs to test the human blood under electrolytes with pH=7.4. Thus, the test should be conducted outside the human body.

The low concentration sensitivity of glucose, (a) CV of glucose detection with low concentration (0-10µM). (b) glucose concentration vs. current.

Comparison of the present study with previous studies on nonenzymatic glucose biosensors.

| Electrode materials | Technique | Electrolyte | Linear range | Detection limit | Sensitivity µA mM−1 cm−2 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiNPs/PAni | AMP | 0.1 M NaOH | 0.02–1 mM | 1 µM | 278.8 | [39] |

| PAni/Cd | AMP | 0.1 M NaOH | 0.0005–0.01 M | 0.5 mM | 5.23 | [40] |

| Cu–PAni | AMP | 0.1 M NaOH | 0.02–10 mM | 9.36 µM | 61.6 | [41] |

| PAni(COOH)-PEI-Fc/Cu-MCNB | DPV | 0.01 M PBS | 0.50–14 mM | 0.16 mM | 14.3 | [42] |

| GO/Fe3O4/PAni | CV | PBS | 0.05 µM–5 mM | 0.01 µM | – | [43] |

| PAni | CV | 0.1PBS (pH=5.5) | 1–5 mM | 1 µM | 68.7 | Present study |

The results of the present study show reasonable performance, even in the absence of any additional substances in our sample. Initially, the glucose detection mechanism involves the adsorption of glucose molecules onto a polyaniline surface, which serves as an electrocatalyst. The chemisorption model is assumed to be an important factor in adsorbing the molecules. Secondly, the glucose molecules will undergo an oxidation reaction, leading to their direct conversion into gluconic acid. Thirdly, the pH condition of the PBS electrolyte is a vital parameter to activate the surface.

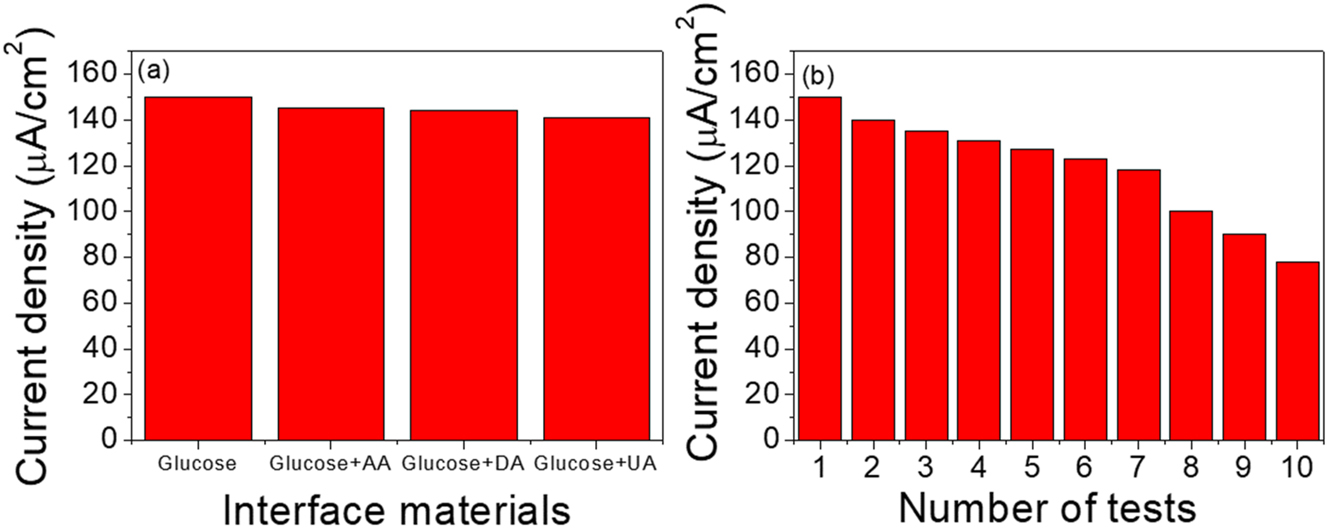

The interfacing of chemical substances with glucose is important to show selectivity in the detection of glucose mixed with other biomaterials. Different biomaterials were used like AA, UA, and DA, by adding 1 mM to PBS containing 1 mM glucose. No apparent interfaces with other biomaterials are shown in Figure 7a. This result led to the conclusion that our biosensor is selective. Furthermore, the stability of the PANI electrode was evaluated at repetitions 10. Experimental results showed a 50 % reduction in stability after 10 tests, as depicted in Figure 7b. The low stability due to low adhesive mesoporous polyaniline on the glassy carbon electrode causes easy corrosion.

The bar chart of Interference and stability of polyaniline biosensor, (a) Interference test, (b) stability electrode of the polyaniline film grown on glassy carbon electrode under pH = 5.5, and PBS (0.1 M).

Conclusions

Daily diagnosis of diabetes is so expensive by using enzymatic agents. A great effort was carried out to synthesize cheap biosensors with excellent performance to detect glucose. A nonenzymatic technique was used to fabricate polyaniline biosensors. Polyaniline was directly deposited on the GC electrode by electropolymerization, and different techniques were used to characterize the biosensor. The glucose sensor performance was significantly affected by the pH condition. The excellent pH condition was obtained with pH=5.5 with the higher sensitivity of 68.7 μA mM−1 cm−2, while the limit of detection (LOD) shows low concentration detection of 1 µM. However, it is impossible to directly test the blood in the human body due to the need change of pH blood. Therefore, it prefers to test glucose in vitro. Moreover, there is no influence on biosensor sensitivity after adding different biomaterials such as UA, AA, and DA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials Research Center and University of Technology (UOT) Iraq, Baghdad, for supporting the experimental part of this research.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes: executive summary. World Health Organization; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

2. Wang, H-C, Lee, A-R. Recent developments in blood glucose sensors. J Food Drug Anal 2015;23:191–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfda.2014.12.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Bobrowski, T, Schuhmann, W. Long-term implantable glucose biosensors. Curr Opin Electrochem 2018;10:112–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coelec.2018.05.004.Search in Google Scholar

4. Lee, J, Ji, J, Hyun, K, Lee, H, Kwon, Y. Flexible, disposable, and portable self-powered glucose biosensors visible to the naked eye. Sensor Actuator B Chem 2022;372:132647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2022.132647.Search in Google Scholar

5. Chavez-Urbiola, IR, Reséndiz-Jaramillo, AY, Willars-Rodriguez, FJ, Martinez-Saucedo, G, Arriaga, LG, Alcantar-Peña, J, et al.. ‘Glucose biosensor based on a flexible Au/ZnO film to enhance the glucose oxidase catalytic response. J Electroanal Chem 2022;926:116941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2022.116941.Search in Google Scholar

6. Escalona-Villalpando, RA, Sandoval-García, A, Roberto Espinosa, LJ, Miranda-Silva, MG, Arriaga, LG, Minteer, SD, et al.. A self-powered glucose biosensor device based on microfluidics using human blood. J Power Sources 2021;515:230631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230631.Search in Google Scholar

7. Nie, H, Yao, Z, Zhou, X, Yang, Z, Huang, S. Nonenzymatic electrochemical detection of glucose using well-distributed nickel nanoparticles on straight multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Biosens Bioelectron 2011;30:28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2011.08.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Hu, Y, He, F, Ben, A, Chen, C. Synthesis of hollow Pt–Ni–graphene nanostructures for nonenzymatic glucose detection. J Electroanal Chem 2014;726:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2014.05.012.Search in Google Scholar

9. Nantaphol, S, Watanabe, T, Nomura, N, Siangproh, W, Chailapakul, O, Einaga, Y. ‘Bimetallic Pt–Au nanocatalysts electrochemically deposited on boron-doped diamond electrodes for nonenzymatic glucose detection. Biosens Bioelectron 2017;98:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2017.06.034.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Feng, X, Cheng, H, Pan, Y, Zheng, H. Development of glucose biosensors based on nanostructured graphene-conducting polyaniline composite. Biosens Bioelectron 2015;70:411–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2015.03.046.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Gmucová, K. Fundamental aspects of organic conductive polymers as electrodes. Curr Opin Electrochem 2022;36:101117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coelec.2022.101117.Search in Google Scholar

12. Kim, D-M, Cho, SJ, Cho, C-H, Kim, KB, Kim, M-Y, Shim, Y-B. Disposable all-solid-state pH and glucose sensors based on conductive polymer covered hierarchical AuZn oxide. Biosens Bioelectron 2016;79:165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2015.12.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Kuznetsova, LS, Arlyapov, VA, Kamanina, OA, Lantsova, EA, Tarasov, SE, Reshetilov, AN. Development of nanocomposite materials based on conductive polymers for using in glucose biosensor. Polymers 2022;14:1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14081543.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Lai, J, Yi, Y, Zhu, P, Shen, J, Wu, K, Zhang, L, et al.. Polyaniline-based glucose biosensor: a review. J Electroanal Chem 2016;782:138–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.10.033.Search in Google Scholar

15. Osuna, V, Vega-Rios, A, Zaragoza-Contreras, EA, Estrada-Moreno, IA, Dominguez, RB. Progress of polyaniline glucose sensors for diabetes mellitus management utilizing enzymatic and nonenzymatic detection. Biosensors 2022;12:137. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios12030137.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Zhai, D, Liu, B, Yi, S, Pan, L, Wang, Y, Li, W, et al.. Highly sensitive glucose sensor based on Pt nanoparticle/polyaniline hydrogel heterostructures. ACS Nano 2013;7:3540–6. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn400482d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Jia, H, Shang, N, Feng, Y, Ye, H, Zhao, J, Wang, H, et al.. Facile preparation of Ni nanoparticle embedded on mesoporous carbon nanorods for nonenzymatic glucose detection. J Colloid Interface Sci 2021;583:310–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2020.09.051.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Kajisa, T, Hosoyamada, S. Mesoporous silica-based metal oxide electrode for a nonenzymatic glucose sensor at a physiological pH. Langmuir 2021;37:13559–66. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.1c01740.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Walcarius, A. Mesoporous materials-based electrochemical sensors. Electroanalysis 2015;27:1303–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/elan.201400628.Search in Google Scholar

20. Huang, W, Ge, L, Chen, Y, Lai, X, Peng, J, Tu, J, et al.. Ni(OH)2/NiO nanosheet with opulent active sites for high-performance glucose biosensor. Sensor Actuator B Chem 2017;248:169–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2017.03.151.Search in Google Scholar

21. Luo, X-L, Xu, J-J, Du, Y, Chen, H-Y. A glucose biosensor based on chitosan–glucose oxidase–gold nanoparticles biocomposite formed by one-step electrodeposition. Anal Biochem 2004;334:284–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2004.07.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Wang, B, Bin, L, Deng, Q, Dong, S. Amperometric glucose biosensor based on Sol−Gel Organic−Inorganic hybrid material. Anal Chem 1998;70:3170–4. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac980160h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Lakhdari, D, Guittoum, A, Benbrahim, N, Belgherbi, O, Berkani, M, Vasseghian, Y, et al.. A novel nonenzymatic glucose sensor based on NiFe(NPs)–polyaniline hybrid materials. Food Chem Toxicol 2021;151:112099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2021.112099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Aynaou, A, Youbi, B, Lghazi, Y, Himi, MA, Bahar, J, El Haimer, C, et al.. Nucleation, growth and electrochemical performances of polyaniline electrodeposited on ITO substrate. J Electrochem Soc 2022;169:082509. https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ac862a.Search in Google Scholar

25. Korent, A, Soderžnik, KŽ, Šturm, S, Rožman, KŽ. A correlative study of polyaniline electro-polymerization and its electrochromic behavior. J Electrochem Soc 2020;167:106504. https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ab9929.Search in Google Scholar

26. Thongkhao, P, Phonklam, K, Phairatana, T. The performance of polyaniline electro-polymerization at various acidic electrolytes on gold electrodes for electrochemical biosensor application. ECS Trans 2022;107:9285. https://doi.org/10.1149/10701.9285ecst.Search in Google Scholar

27. Ahmed, J, Rashed, MA, Faisal, M, Harraz, FA, Jalalah, M, Alsareii, SA. Novel SWCNTs-mesoporous silicon nanocomposite as efficient nonenzymatic glucose biosensor. Appl Surf Sci 2021;552:149477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149477.Search in Google Scholar

28. Yang, X, Qiu, P, Yang, J, Fan, Y, Wang, L, Jiang, W, et al.. Mesoporous materials–based electrochemical biosensors from enzymatic to nonenzymatic. Small 2021;17:1904022. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201904022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Mostafaei, A, Zolriasatein, A. Synthesis and characterization of conducting polyaniline nanocomposites containing ZnO nanorods. Prog Nat Sci: Mater Int 2012;22:273–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2012.07.002.Search in Google Scholar

30. Zhang, Y, Liu, J, Zhang, Y, Liu, J, Duan, Y. Facile synthesis of hierarchical nanocomposites of aligned polyaniline nanorods on reduced graphene oxide nanosheets for microwave absorbing materials. RSC Adv 2017;7:54031–8. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ra08794b.Search in Google Scholar

31. Pang, S, Chen, W, Yang, Z, Liu, Z, Fan, X, Fang, D. Facile synthesis of polyaniline nanotubes with square capillary using urea as template. Polymers 2017;9:510. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9100510.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Yonehara, T, Komaba, K, Goto, H. Synthesis of polyaniline in seawater. Polymer 2020;12:375. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12020375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Goswami, S, Nandy, S, Calmeiro, TR, Igreja, R, Martins, R, Fortunato, E. Stress induced mechano-electrical writing-reading of polymer film powered by contact electrification mechanism. Sci Rep 2016;6:19514. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19514.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Wu, J, Yin, L. Platinum nanoparticle modified polyaniline-functionalized boron nitride nanotubes for amperometric glucose enzyme biosensor. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2011;3:4354–62. https://doi.org/10.1021/am201008n.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Varatharajan, P, Maruthupandi, M, Kumar Ponnusamy, V, Vasimalai, N. Purpald-functionalized biosensor for simultaneous electrochemical detection of ascorbic acid, uric acid, L-cysteine and lipoic acid. Biosens Bioelectron X 2024;17:100458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosx.2024.100458.Search in Google Scholar

36. Yulianti, ES, Rahman, SF, Rizkinia, M, Ahmad, Z. Low-cost electrochemical biosensor based on a multi-walled carbon nanotube-doped molecularly imprinted polymer for uric acid detection. Arab J Chem 2024;17:105692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105692.Search in Google Scholar

37. Fatoni, A, Widanarto, W, Anggraeni, MD, Dwiasi, DW. Glucose biosensor based on activated carbon – NiFe2O4 nanoparticles composite modified carbon paste electrode. Results Chem 2022;4:100433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100433.Search in Google Scholar

38. Keteklahijani, YZ, Sharif, F, Roberts, EPL, Sundararaj, U. Enhanced sensitivity of dopamine biosensors: an electrochemical approach based on nanocomposite electrodes comprising polyaniline, nitrogen-doped graphene, and DNA-functionalized carbon nanotubes. J Electrochem Soc 2019;166:B1415. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0361915jes.Search in Google Scholar

39. Lakhdari, D, Guittoum, A, Benbrahim, N, Belgherbi, O, Berkani, M, Seid, L, et al.. Elaboration and characterization of Ni (NPs)-PANI hybrid material by electrodeposition for nonenzymatic glucose sensing. J Electron Mater 2021;50:5250–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-021-09031-2.Search in Google Scholar

40. Bano, S, Ganie, AS, Sultana, S, Khan, MZ, Sabir, S. The nonenzymatic electrochemical detection of glucose and ammonia using ternary biopolymer based-nanocomposites. New J Chem 2021;45:8008–21. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1nj00474c.Search in Google Scholar

41. Prathap, MUA, Pandiyan, T, Srivastava, R. Cu nanoparticles supported mesoporous polyaniline and its applications towards nonenzymatic sensing of glucose and electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol. J Polym Res 2013;20:83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-013-0083-y.Search in Google Scholar

42. Gopalan, AI, Muthuchamy, N, Komathi, S, Lee, KP. A novel multicomponent redox polymer nanobead based high performance nonenzymatic glucose sensor. Biosens Bioelectron 2016;84:53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2015.10.079.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Batool, R, Akhtar, MA, Hayat, A, Han, D, Niu, L, Ahmad, MA, et al.. A nanocomposite prepared from magnetite nanoparticles, polyaniline and carboxy-modified graphene oxide for nonenzymatic sensing of glucose. Microchim Acta 2019;186:267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00604-019-3364-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/bmt-2024-0141).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- An exploratory study of pilot EEG features during the climb and descent phases of flight

- Gesture recognition from surface electromyography signals based on the SE-DenseNet network

- Empirical analysis on retinal segmentation using PSO-based thresholding in diabetic retinopathy grading

- Prediction of remaining surgery duration based on machine learning methods and laparoscopic annotation data

- Caries-segnet: multi-scale cascaded hybrid spatial channel attention encoder-decoder for semantic segmentation of dental caries

- An analysis of initial force and moment delivery of different aligner materials

- Influence of microstructure on metal-ceramic bonding in SLM-manufactured titanium alloy crowns and bridges

- Design and evaluation of powered lumbar exoskeleton based on human biomechanics

- Evaluation of mesoporous polyaniline for glucose sensor under different pH electrolyte conditions

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- An exploratory study of pilot EEG features during the climb and descent phases of flight

- Gesture recognition from surface electromyography signals based on the SE-DenseNet network

- Empirical analysis on retinal segmentation using PSO-based thresholding in diabetic retinopathy grading

- Prediction of remaining surgery duration based on machine learning methods and laparoscopic annotation data

- Caries-segnet: multi-scale cascaded hybrid spatial channel attention encoder-decoder for semantic segmentation of dental caries

- An analysis of initial force and moment delivery of different aligner materials

- Influence of microstructure on metal-ceramic bonding in SLM-manufactured titanium alloy crowns and bridges

- Design and evaluation of powered lumbar exoskeleton based on human biomechanics

- Evaluation of mesoporous polyaniline for glucose sensor under different pH electrolyte conditions