Abstract

Objectives

This study focuses on the effect of microstructural surface characteristics on metal-ceramic bond strength for SLM-fabricated titanium alloy. This research seeks to improve metal-ceramic adhesion in SLM-produced parts.

Methods

Inspired by the hydrophilic structure of Calathea zebrina, bioinspired microstructures were designed on titanium alloy surfaces. Samples were categorized into two groups: those with microstructured surfaces and those with smooth surfaces. Various microstructural parameters were implemented. Bending tests were conducted on all samples, which were subjected to the same porcelain-fused-to-metal sintering process. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) were employed to examine the bonding and separation surfaces of titanium alloy and porcelain.

Results

Metal-porcelain bonding strength is strongly influenced by the spacing and height of the bionic microstructure. Surfaces with the microstructure showed significantly higher bonding strength and distinctly different residue characteristics after peeling compared to surfaces without the microstructure.

Conclusions

Microstructured surfaces on titanium alloy substrates facilitate robust chemical and mechanical bonding between metal and porcelain, markedly enhancing the performance of SLM-produced metal-ceramic restorations.

Introduction

The materials for metal substrates in crowns are primarily categorized into cobalt-chromium alloys, pure titanium, nickel-chromium alloys, gold-platinum-palladium alloys, and noble metals such as gold alloys [1]. Nickel-chromium alloys may release harmful chemical ions to natural teeth and the oral cavity, leading to clinical issues such as gingival discoloration and black lines on the gums. Long-term use may pose carcinogenic risks. Although they are cost-effective, these alloys pose health hazards and are gradually being phased out in the restoration industry [2]. Titanium alloys are widely used in the field of oral restoration for fixed dentures, removable partial dentures, and upper structures supported by implants due to their high corrosion resistance, good biocompatibility, lightweight, and excellent mechanical properties [3], [4], [5]. Currently, cases of porcelain chipping and delamination caused by insufficient bonding strength between metal and porcelain account for about 60 % of all restoration failure cases [6]. The primary mode of failure is metal-ceramic bond failure, and improving this bond strength is crucial for producing high-quality components. Selective laser melting (SLM) is an additive manufacturing technique that uses a high-power laser to produce components with fine geometries and complex porous structures [7], [8], [9], [10]. Zhou Yanan et al. [11] found that alloys produced by the SLM method exhibit better metal-ceramic bonding strength when compared to those made using the CAST method. Li Haojie [12] compared TC4 titanium alloy samples produced by SLM, forging, and casting, demonstrating that SLM results in superior quality and performance, based on analyses of mechanical properties and microstructure. Mechanical interlocking accounts for about 22 % of the metal-ceramic bonding strength, primarily through increasing the surface area and wettability of the bonding interface, providing a theoretical basis for surface modification of the metal-ceramic bonding interface. Methods such as surface sandblasting and constructing microstructures on the surface can enhance mechanical interlocking, thereby increasing metal-ceramic bonding strength [13], [14], [15], [16]. After sandblasting treatment, the surface contact angle decreases, improving wettability, which is related to the metal-ceramic bonding strength, contact angle, and wettability [17]. The metal-ceramic bonding interface treated with Al2O3 sandblasting achieves a certain degree of roughness, and rough microstructures can create a secure mechanical locking structure with the porcelain layer [18]. Mao Wu et al. [19] proposed that rough surfaces enhance porcelain wettability. They also noted that rough pores create a mechanical interlock when filled and sintered with porcelain powder. Furthermore, they suggested that the increased surface area from rough surfaces promotes improved chemical bonding. The method of designing new materials based on the microstructure of biological surfaces has been widely applied in material science, biomedical engineering, mechanical engineering, and other fields. The construction of microstructures can be achieved through 3D printing [20], [21], [22]. Obaldia E D et al. [23] used 3D printing to mimic the wear-resistant rod-like microstructure found in the radula of the giant mollusk Cryptochiton stelleri, studying the fracture and damage tolerance of this biomimetic structure. Currently, there is limited research on the surface microstructure of titanium alloys produced by selective laser melting and their bonding strength with porcelain. This study takes the titanium alloy surface without microstructure formed by selective laser melting as a control group and investigates the improvement of metal-ceramic bonding strength using titanium surfaces with microstructures formed by selective laser melting. Through biomimetic structure design and preparation, this research aims to provide ideas and methods for solving practical problems.

Materials and methods

Materials

The experimental metal powder used is Ti6Al4V (TC4) powder produced by Xi’an Sailong Metal Materials Co., Ltd. The powder has a full, round, and uniform particle size distribution ranging from 19.32 to 52.18 μm, with an average particle size of 22.68 μm and a theoretical density of 4.43 g/cm3. According to the supplier, the powder’s composition (in wt %) was: Al 6.13, V 3.98, Fe 0.036, O 0.081, N 0.02, C 0.008, H 0.0014, balance Ti. The materials used include masking paste (SHOFU Halo MP PASTE OPAQUE) and dental porcelain powder (SHOFU VINTAGE Halo Dentin).

Structural design

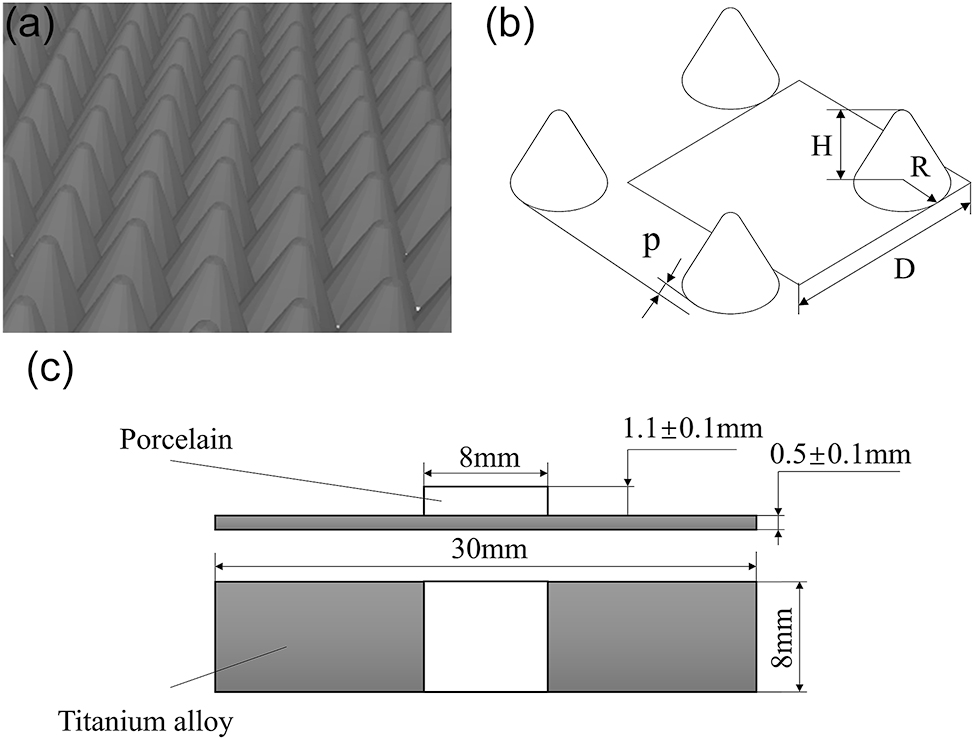

Through the simplified design of the surface structure of Calathea zebrina, the structure is made to closely approximate the microstructure of the Calathea zebrina surface within the realm of processability, as shown in the surface structure model and schematic diagram in Figure 1a and b. The wettability of the microstructure system tends to conform to the Wenzel model. Incorporating the design dimensions, the theoretical formula for the surface contact angle is:

Where θ e represents the intrinsic contact angle of the surface (°); D is the spacing of the microstructure (mm); R is the bottom radius of the microstructure (mm); and H is the height of the microstructure (mm).

Sample design. (a) Bionic model. (b) Microstructure size diagram. (c) Schematic diagram of the size of the substrate and porcelain.

Two types of samples were prepared: one with a smooth surface and the other with a microstructured surface. The specimens were designed according to the ISO standard ISO 9693:2019, with dimensions shown in Figure 1c. The porcelain area is centered within an 8 mm range, and microstructures are set within this area.

Preparation of samples

The experimental equipment used for sample preparation was the DiMetal-100 multi-material metal 3D printer from Guangzhou Leijia Additive Manufacturing. The optimized process parameters included a laser power of 160 W, a scanning spacing of 0.02 mm, a scanning speed of 500 mm/s, a layer thickness of 0.03 mm, and a spot diameter of 0.08 mm, with an oxygen content of less than 0.1 % during the manufacturing process. Both the control group (smooth surface samples) and the microstructured group samples were ultrasonically cleaned in anhydrous ethanol, acetone, and distilled water for 5 min each. After drying, the surfaces were sandblasted with 50 μm Al2O3 particles at a pressure of 5 bar, with the nozzle positioned 50 mm from the samples at an angle of approximately 45°, changing the sandblasting direction every 15 s. After sandblasting, the samples were ultrasonically cleaned in anhydrous ethanol and acetone for 5 min, followed by a 10-min rinse in deionized water before drying. Porcelain application followed the manufacturer’s protocol, with firing parameters as follows: Pre-oxidation (300 °C preheating, 1 s cooling, 50 °C/min heating to 500 °C for 50 s); Opaque Porcelain Layer 1 (500 °C preheating, 10 s cooling, 50 °C/min heating to 760 °C for 50 s); Opaque Porcelain Layer 2 (500 °C preheating, 10 s cooling, 50 °C/min heating to 750 °C for 50 s); Porcelain Body (500 °C preheating, 5 s cooling, 50 °C/min heating to 790 °C for 38 s), the porcelain operation is executed within a vacuum porcelain furnace. After the firing process, the porcelain layer undergoes a polishing procedure to achieve the desired standard geometric configuration.

The standard specimens of each group after porcelain-fused were placed in a universal mechanical testing machine for bending tests. The applied load showed that the cross-loading head was pressed at a constant speed of (1.5 ± 0.5) mm/min until the specimen was broken, and the fracture mutation was recorded. The distance between the support rods is 20 mm, and the diameter of the loading head is 2 mm. The three-point bending strength of the debonding crack initiation strength can be calculated using the following formula:

In the formula: τ b is the three-point bending strength (MPa); k is the coefficient [24]; Ffail is the measured fracture force. The coefficient k is determined by the thickness dM of the metal matrix and the Young’s modulus EM of the metal material. According to the Young’s modulus EM of the metal substrate, the appropriate curve is selected, and the corresponding k value in the curve is read according to the substrate thickness dM. The dM is the thickness of the metal substrate. According to the standard, the dM is 0.5 mm, the material is TC4, Young’s modulus EM is about 110 GPa, and the coefficient k is about 4.82.

Experimental design

A single-factor experiment was conducted, with R, D, H, and P as the variables. Samples with varied parameter combinations were fabricated using SLM. Results from the single-factor experiment (Table 1) indicated that the staggered distance had a negligible impact on the actual contact area. Consequently, the staggered distance was found to have no significant effect on the bonding strength of the metal-ceramic interface. To ensure optimal forming quality and microstructure morphology, the subsequent orthogonal experiment focused on a microstructure without any staggered displacement. A three-factor, three-level orthogonal experiment was designed, and the specific levels for each factor are presented in Table 1.

Orthogonal experiment scheme, and single factor experiment design and results.

| R, mm | D, mm | H, mm | P, mm | Contact angle/° | Bonding strength/MPa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53.2 | 21.3 ± 1.14 |

| 2 | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0 | 45.6 | 22.5 ± 0.89 |

| 3 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0 | 17.1 | 36.59 ± 1.22 |

| 4 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0 | 22.5 | 32.52 ± 1.01 |

| 5 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0 | 31.1 | 26.89 ± 0.96 |

| 6 | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0 | 27.3 | 33.22 ± 1.35 |

| 7 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0 | 23.5 | 34.89 ± 0.96 |

| 8 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.15 | 0 | 16.0 | 38.42 ± 1.05 |

| 9 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0 | 30.3 | 30.58 ± 1.23 |

| 10 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0 | 39.9 | 18.26 ± 0.98 |

| 11 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.15 | 0 | 19.0 | 38.42 ± 1.05 |

| 12 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0 | 11.7 | 44.98 ± 1.86 |

| 13 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0 | 20.7 | 31.59 ± 1.75 |

| 14 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.30 | 0 | 27.6 | 25.46 ± 1.05 |

| 15 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0 | 11.7 | 44.98 ± 1.86 |

| 16 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.1 | 12.1 | 43.15 ± 1.41 |

| 17 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.2 | 12.5 | 42.03 ± 1.28 |

| 18 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.3 | 13 | 41.92 ± 1.41 |

| 19 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.4 | 13.4 | 40.67 ± 1.69 |

| w1 | 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.17 | – | – | – |

| w2 | 0.17 | 0.80 | 0.23 | – | – | – |

| w3 | 0.17 | 0.90 | 0.20 | – | – | – |

| w4 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.23 | – | – | – |

| w5 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | – | – | – |

| w6 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.17 | – | – | – |

| w7 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.20 | – | – | – |

| w8 | 0.23 | 0.80 | 0.17 | – | – | – |

| w9 | 0.23 | 0.90 | 0.23 | – | – | – |

Surface characterization

The microstructures on the sample surfaces were observed using a VHX-600K super-depth microscope (KEYENCE, Japan), and the contact angle values of the surface structures were measured using a video optical contact angle meter (OC2, Germany). The morphology of the metal-ceramic separation surface and the metal-ceramic bonding surface was characterized by SEM and EDS.

Results and discussion

The effect of structure size on the bonding strength of metal-ceramic

This study investigated the influence of the microstructure’s bottom surface R, D, H, and P on the bonding strength of metal-ceramic interfaces. Three-point bending tests were conducted on microstructured surfaces featuring varying R, D, H, and P following a uniform porcelain-fusing process to ascertain the optimal outcomes.

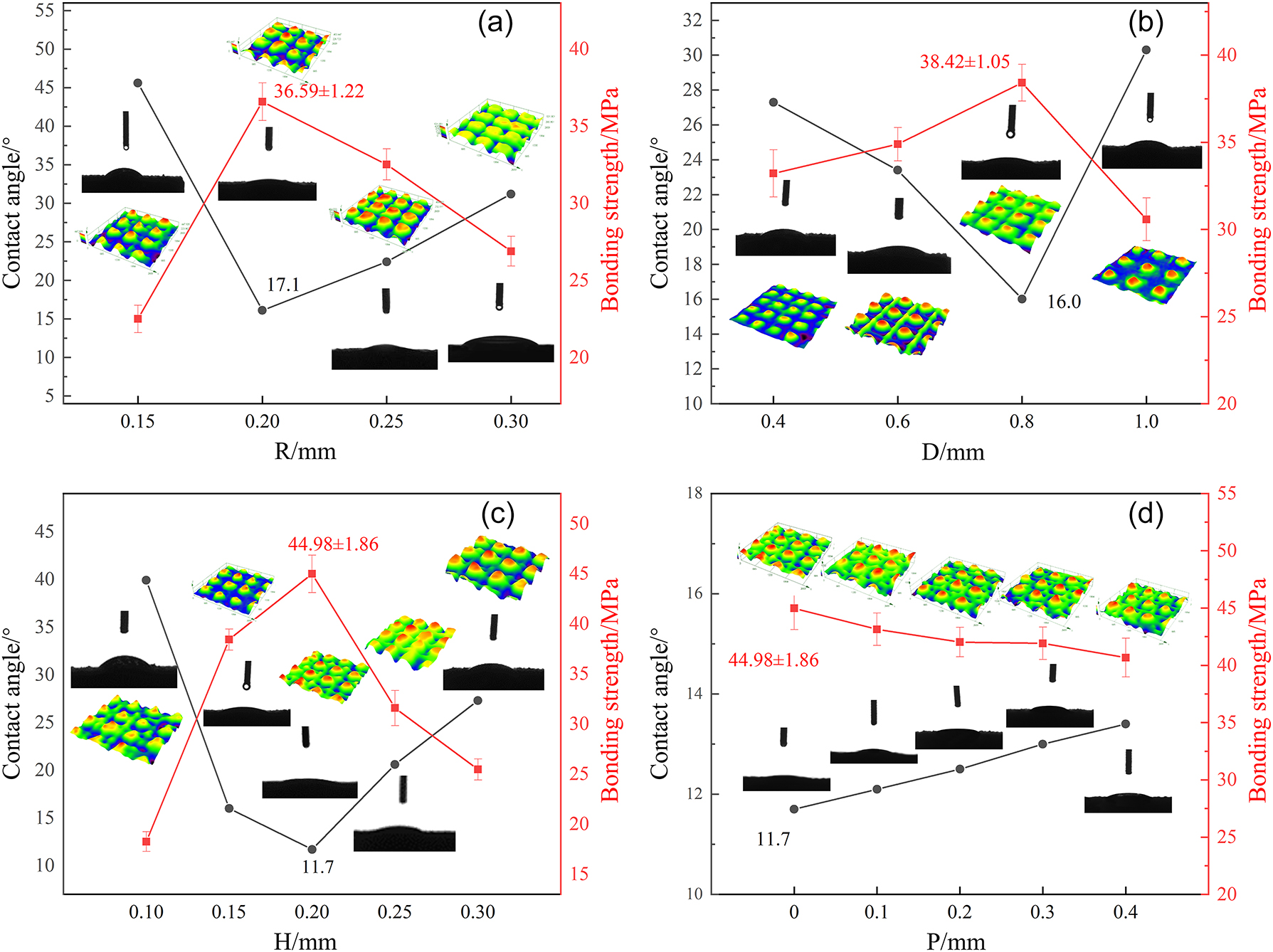

Examination of Figure 2 reveals that the surface of the sample after SLM processing exhibits a degree of roughness, indicative of good surface microstructure preparation quality. The density within each group appears uniform, and no significant defects such as cracks or bubbles are observed, which is beneficial for metal-ceramic bonding. Each group of samples demonstrates hydrophilicity, with a CA less than 90°. Generally, a smaller CA correlates with higher bonding strength. As depicted in Figure 2a, the CA initially decreases and then increases with the radius, corresponding to an initial increase and subsequent decrease in metal-ceramic bonding strength. A microstructure with a radius that is too small results in larger gaps between the microstructures, leading to slow droplet spread and ineffective wetting of the microstructure surface. Figure 2b shows that as the spacing increases, the contact angle and metal-ceramic bonding strength follow a pattern of initial decrease and subsequent increase. If the spacing is too small, the molten ceramic powder may not penetrate the narrow gaps, potentially leading to the formation of difficult-to-eliminate bubbles at the base. Conversely, if the spacing is too large, there is a significant reduction in the number of microstructures, which decreases the surface contact area and consequently increases the contact angle. Figure 2c illustrates that when the height of the microstructure is too small, the contact area between the molten porcelain powder and the substrate differs little from that of a smooth surface, with only a slight improvement in wettability. However, if the height of the microstructure is excessively high, the molten porcelain powder struggles to reach the bottom of the gap, leading to bubble formation and difficulty in discharge due to the accumulation of molten porcelain, which in turn reduces the contact area and wettability. Within the experimental range of staggered displacement, the variation in contact angle and metal-ceramic bonding strength is not markedly affected by changes in staggered displacement.

Contact angles and bonding strength curves of different structure sizes (a) R, (b) D, (c) H and (d) P.

The orthogonal experiment method was used to design the orthogonal experiment of three factors and three levels. According to the results of the single-factor experiment, the level variables of each factor were set. Table 2 records the contact angle of the orthogonal experiment and the results of the three-point bending test.

Orthogonal test contact angle and three-point bending test results.

| R/mm | D/mm | H/mm | Contact angle/° | Bonding strength/MPa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w1 | 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 32.50 | 28.01 ± 1.28 |

| w2 | 0.17 | 0.80 | 0.23 | 24.10 | 36.48 ± 1.86 |

| w3 | 0.17 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 20.60 | 38.59 ± 1.75 |

| w4 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.23 | 33.50 | 22.58 ± 0.96 |

| w5 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 11.70 | 44.98 ± 1.86 |

| w6 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.17 | 30.10 | 29.41 ± 0.88 |

| w7 | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 29.20 | 33.08 ± 1.06 |

| w8 | 0.23 | 0.80 | 0.17 | 25.30 | 36.23 ± 0.97 |

| w9 | 0.23 | 0.90 | 0.23 | 36.90 | 19.20 ± 0.76 |

| wo | 0.17 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 10.10 | 51.06 ± 1.22 |

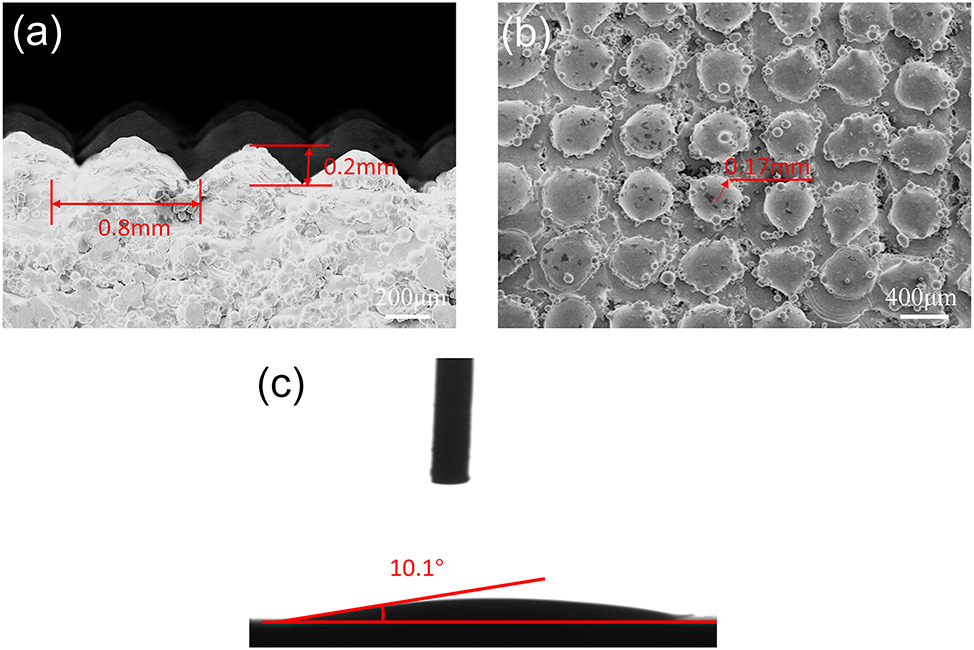

Table 3 presents the results of a multi-factor analysis of variance examining the influence of microstructure R,D and H on metal-ceramic interface bonding strength. The model’s coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.984, indicating that spacing and height significantly influence the bonding strength, with a significance level of 0.05 (p<0.05). The range analysis revealed that the impact of these factors on the bonding strength was in the order of H>D>R. Specifically, under the specific parametric conditions where the microstructural R is precisely 0.17 mm, the interstitial D is 0.80 mm, and the geometric H is 0.20 mm, in conjunction with the absence of any staggered displacement, the CA of the microstructure surface was determined to be 10.1°. Concurrently, the metal-ceramic bond strength achieved a maximum value of (51.06 ± 1.22) MPa. These optimal conditions not only enhanced the surface quality of the fabricated components but also yielded the highest metal-ceramic bond strength, as graphically depicted in Figure 3.

Results of multivariate analysis of variance.

| Quadratic sum | df | Mean square | F | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 9,251.875 | 1 | 9,251.875 | 2,203.486 | 0.000b |

| R | 35.688 | 2 | 17.844 | 4.250 | 0.190 |

| D | 233.273 | 2 | 116.637 | 27.779 | 0.035a |

| H | 248.849 | 2 | 124.425 | 29.634 | 0.033a |

| Residual error | 8.397 | 2 | 4.199 | – | – |

-

R2=0.984. ap<0.05. bp<0.01.

Surface SEM image and contact angle of optimal microstructure parameters.

Analysis of metal-porcelain separation surface

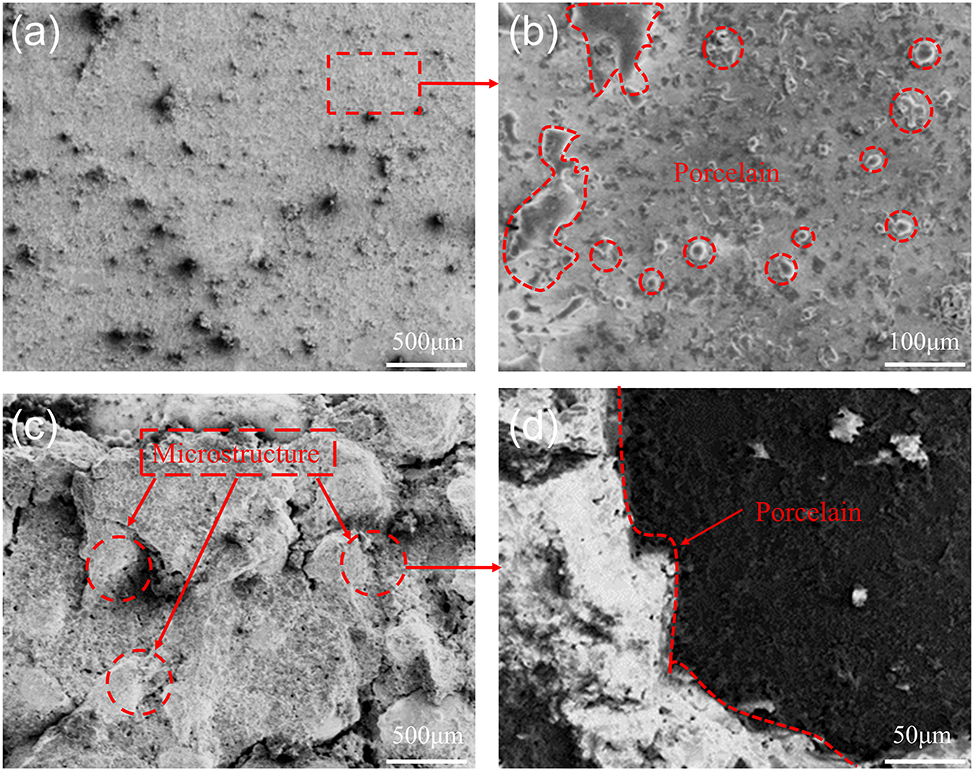

Figure 4a illustrates that the fracture surface of the microstructure-free group exhibited flake-like failure, with a substantial number of porcelain pieces completely detached, leaving minimal porcelain bonding residue. A substantial area of the titanium alloy matrix was exposed, indicating that the majority of the porcelain had peeled off. In contrast, Figure 4b shows that within the micro-pits created by sandblasting, there was a limited presence of porcelain residue, confined to spot-like adhesive areas, while the remainder displayed flake detachment. Figure 4c demonstrates that on the microstructured surface, a significant amount of porcelain is embedded within the microstructure gaps, resulting in a high proportion of porcelain residue. Owing to the microstructure’s unique wettability, numerous molten porcelain powder particles adhere to the gaps of each microstructure unit during the baking process. Facilitated by the enhanced wettability and an extended contact area, the porcelain layer can tightly adhere to the microstructure surface, forming mechanical interlocks and improving the mechanical bonding force at the bonding interface, thereby enhancing the metal-porcelain bonding strength. The microstructured substrate can markedly improve the metal-ceramic bonding strength, with the failure mode of the metal-ceramic interface primarily being adhesive failure.

SEM images of the failure surface of metal-ceramic. (a) Smooth surface. (b) Porcelain residue. (c) Optimal microstructure surface. (d) Local amplification at the microstructure.

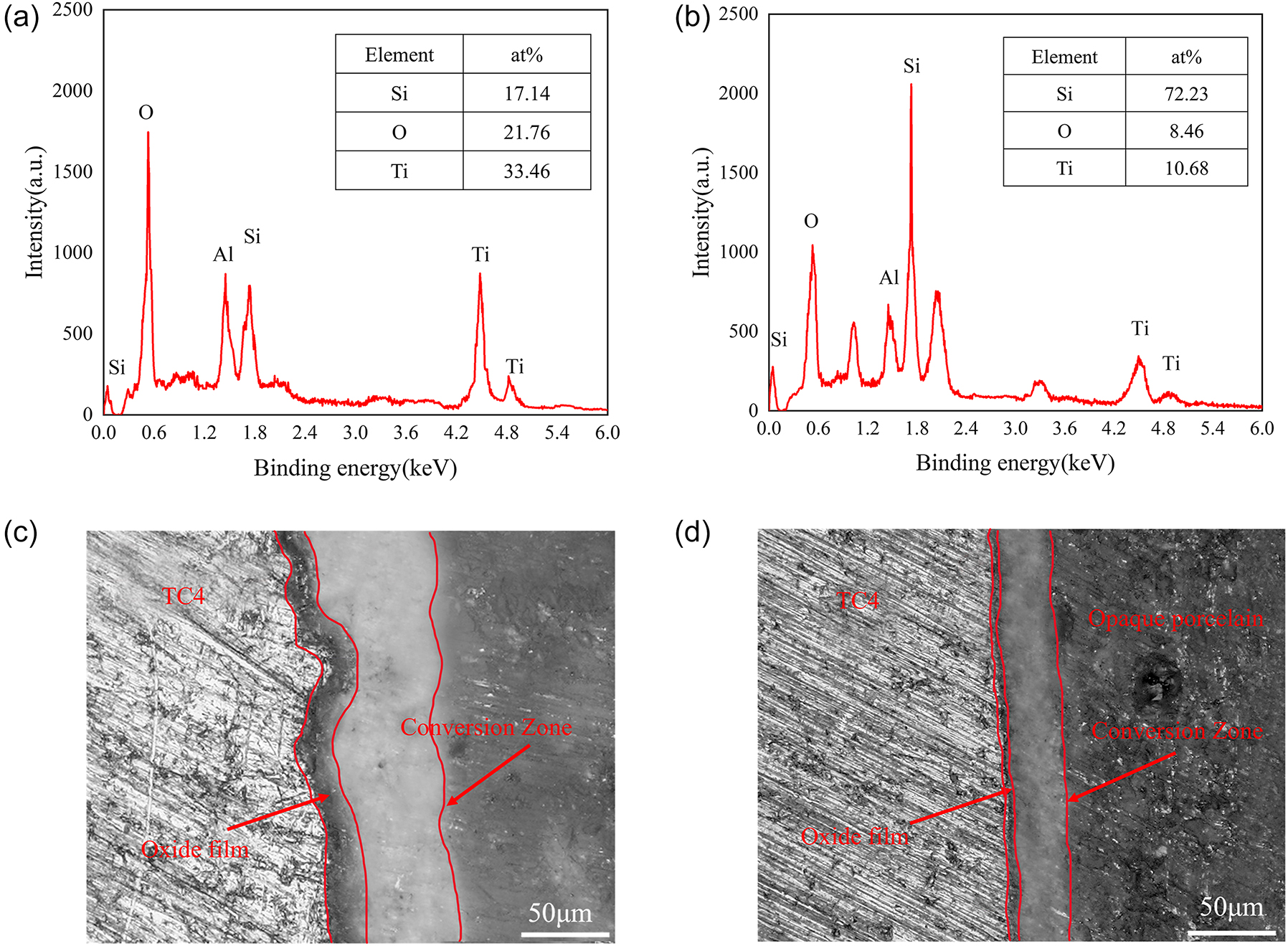

EDS analysis was performed on the fracture surface to ascertain the proportion of ceramic residue and the elemental distribution, as depicted in Figure 5a and b. The common failure modes in the three-point bending test of metal-ceramic structures are categorized into three types: (1) Cohesive failure: where porcelain cracks occur within the porcelain layer itself; (2) Adhesive failure: where the interface between the metal and porcelain layers is compromised; (3) Mixed-mode failure: involving a combination of the above two types of porcelain fractures [25], 26]. Analysis reveals that the low bonding strength between metal and porcelain on the microstructure-free surface leads to extensive flaking of the porcelain layer, with minimal detectable ceramic powder elements, suggesting that the fracture occurs in the relatively weaker oxide layer, with ceramic residue below 20 %. This indicates adhesive failure. In contrast, samples with microstructures exhibit mixed-mode failure. Optimization of the microstructure results in a significant increase in Si residue on the metal-ceramic fracture surface, reaching approximately 72.23 %, with the fracture occurring through both the oxide layer and the porcelain layer. This represents a 55 % increase compared to the non-microstructured surface, demonstrating a superior mechanical interlock and enhanced bonding strength between the metal and porcelain.

EDS scanning results of separation surface (a) sandblasting surface and (b) optimal microstructure surface. SEM images of metal-ceramic bonding section (c) no microstructure group and (d) optimal microstructure group.

Analysis of metal-ceramic bonding cross section

Examination of Figure 5c reveals that the average thickness of the oxide layer at the metal-ceramic interface on the microstructure-free surface is excessively thick, surpassing 5 μm. The presence of a dense and robustly adhered oxide layer on the metal surface is fundamental to enhancing the bonding strength between metal and ceramic. However, the presence of micropores at the interface and a multitude of unmelted ceramic powder particles during the sintering process can lead to an increased oxidation potential at the interface, causing a marked increase in oxide layer thickness. This unceasing oxidation of the substrate metal, due to the insufficient barrier properties of the oxide layer, results in a continuously growing oxide thickness that adversely affects the wettability of the metal-ceramic bonding interface. The oxide layer adhering to the metal surface is characterized by an intermittent and loosely packed morphology, which diminishes the chemical bonding efficacy at the interface. In contrast, Figure 5d demonstrates that the microstructured surface with optimal parameters exhibits excellent wettability, limiting the bonding interface’s exposure to excessive oxygen. Consequently, the oxide layer thickness at the metal-ceramic interface is comparatively slender, measuring 0.5–0.7 μm, with a uniform distribution. The oxide layer is intimately integrated between the metal and the ceramic layer. Partial melting of the metal surface allows for a tight interlocking with the underlying ceramic layer, creating a mechanical locking effect akin to that desired in bonding. The bonding interface is devoid of defects such as micropores, presenting a smooth and even surface topography.

Conclusions

The biomimetic microstructure on the surface of titanium alloy can increase the contact area between the substrate surface and the porcelain, enhance the bonding strength between the metal and the porcelain layer, and make the molten porcelain more closely bonded to the surface of titanium alloy.

The residual porcelain on the surface of titanium alloy with a microstructure was significantly increased compared to the surface without a microstructure. This failure mode was classified as mixed, closely resembling cohesive failure. The enhanced wettability and increased contact area allowed the sintered porcelain layer to closely adhere to the microstructure’s surfaces and gaps, creating a mechanical interlock. This interlock improves the metal-ceramic bonding strength.

During the porcelain-fusing process, the molten porcelain powder particles achieve complete wetting, facilitating effective chemical bonding. The oxide film at the metal-ceramic interface exhibits a uniform thickness, ranging from 0.5 to 0.7 μm. Concurrently, partial melting of the metal surface occurs, allowing it to interlock with the porcelain. This mechanical interlocking, in conjunction with the chemical bonding, enhances metal-ceramic bonding strength.

Funding source: Key Research and Development Projects of Shaanxi Province

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2022GY-226

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province, China (No. 2022GY-226).

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: All other authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province, China (No. 2022GY-226).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Gupta, T, Shetty, S, Shetty, N, Shetty, SD. A review on metallic dental materials and its fabrication techniques. Int J Mech Prod Eng Res Dev 2019;9:491–510.Search in Google Scholar

2. Yu, L, Su, J, Zou, D, Mariano, Z. The concentrations of IL-8 and IL-6 in gingival crevicular fluid during nickel–chromium alloy porcelain crown restoration. J Mater Sci-Mater M 2013;24:1717–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-013-4924-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Luo, XP, Wei, YX, Huang, HN, Hu, DD, Pang, EL. Pure titanium denture large-span frameworks additively manufactured with selective laser melting. Chin J Stomatol 2021;56:646–51. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20210405-00162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Totou, D, Naka, O, Mehta, SB, Banerji, S. Esthetic, mechanical, and biological outcomes of various implant abutments for single-tooth replacement in the anterior region: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2021;7:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-021-00370-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Parushev, I, Dikova, T, Katreva, I, Gagov, Y, Simeonov, S. Adhesion of dental ceramic materials to titanium and titanium alloys: a review. Oxf Open Mater Sci 2023;3:itad011. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfmat/itad011.Search in Google Scholar

6. Aboras, MM, Muchtar, A, Azhari, CH, Yahaya, N. Types of failures in porcelain-fused-to-metal dental restoration. In: Lacković, I, Vasic, D, editors. 6th European Conference of the International Federation for Medical and Biological Engineering: MBEC 2014. Dubrovnik, Croatia: Springer; 2014, paper no. 86:345–8 pp.10.1007/978-3-319-11128-5_86Search in Google Scholar

7. Murr, LE. Metallurgy principles applied to powder bed fusion 3D printing/additive manufacturing of personalized and optimized metal and alloy biomedical implants: an overview. J Mater Res Technol 2020;9:1087–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.12.015.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sefene, EM. State-of-the-art of selective laser melting process: a comprehensive review. J Manuf Syst 2022;63:250–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2022.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

9. Gao, B, Zhao, H, Peng, L, Sun, Z. A review of research progress in selective laser melting (SLM). Micromachines 2022;14:57. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi14010057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Dikova, T, Maximov, J, Gagov, Y. Experimental and FEM investigation of adhesion strength of dental ceramic to milled and SLM fabricated Ti6Al4V alloy. Eng Fract Mech 2023;291:109528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfracmech.2023.109528.Search in Google Scholar

11. Zhou, YN, Wei, W, Yan, JZ, Li, N, Xu, S, Zhang, B. Evaluation of metal-ceramic bond characteristics of Co-Cr-Mo alloys fabricated by selective laser melting. Adv Eng Sci 2018;50:220–5.Search in Google Scholar

12. Zhu, YZ, Li, HJ, Peng, H. Effect of different processing methods on microstructure and mechanical properties of TC4 Titanium alloy. J Cent China Norm Univ (Nat Sci) 2019;53.Search in Google Scholar

13. Wight, TA, Bauman, JC, Pelleu, JGB. Variables affecting the strength of the porcelain/nonprecious alloy bond. J Prosthet Dent 1977;38:148. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(77)90279-7.Search in Google Scholar

14. Troia, JMG, Henriques, GE, Mesquita, MF, Fragoso, WS. The effect of surface modifications on titanium to enable titanium-porcelain bonding. Dent Mater 2008;24:28–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2007.01.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Chaiyabutr, Y, Mcgowan, S, Phillips, KM, Kois, JC, Giordano, RA. The effect of hydrofluoric acid surface treatment and bond strength of a zirconia veneering ceramic. J Prosthet Dent 2008;100:194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3913(08)60178-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Dikova, T, Anchev, A, Dunchev, V, Dzhendov, D, Gagov, Y. Experimental investigation of adhesion strength of dental ceramic to Ti6Al4V alloy fabricated by milling and selective laser melting. Procedia Struct Integr 2022;42:1520–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostr.2022.12.193.Search in Google Scholar

17. Mukai, M, Fukui, H, Hasegawa, J. Relationship between sandblasting and composite resin-alloy bond strength by a silica coating. J Prosthet Dent 1995;74:151–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3913(05)80178-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Jin, L, Wang, ZY, Li, XK, Shen, LJ, Zhang, SH. A study of the interfacial area of auro-galvano-form ceramic crowns. J Pract Stomatol 2004;20:76–9.Search in Google Scholar

19. Wu, M, Chang, L, Zhang, L, He, X, Qu, X. Effects of roughness on the wettability of high temperature wetting system. Surf Coat Tech 2016;287:145–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.12.092.Search in Google Scholar

20. Li, Z, Sang, S, Jiang, S, Chen, L, Zhang, H. A self-detecting and self-cleaning biomimetic porous metal-based hydrogel for oil/water separation. Acs Appl Mater Inter 2022:14.10.1021/acsami.2c05327Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Lu, J, Zhuo, L, Materials, H. Additive manufacturing of titanium alloys via selective laser melting: fabrication, microstructure, post-processing, performance and prospect. Int J Refract Met 2023;111:106110.10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2023.106110Search in Google Scholar

22. Eskandari, H, Lashgari, H, Zangeneh, S, Kong, C, Ye, L, Eizadjou, M, et al.. Microstructural characterization and mechanical properties of SLM-printed Ti–6Al–4V alloy: effect of build orientation. J Mater Res 2022;37:2645–60. https://doi.org/10.1557/s43578-021-00468-z.Search in Google Scholar

23. Obaldia, ED, Jeong, C, Grunenfelder, LK, Kisailus, D, Zavattieri, P. Analysis of the mechanical response of biomimetic materials with highly oriented microstructures through 3D printing, mechanical testing and modeling. J Mech Behav Biomed 2015:70–85.10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.03.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Cai, Z, Watanabe, I, Mitchell, JC, Brantley, W, Okabe, T. X-ray diffraction characterization of dental gold alloy-ceramic interfaces. J Mater Sci-Mater M 2001;12:215–23. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008906930748.10.1023/A:1008906930748Search in Google Scholar

25. Akova, T, Ucar, Y, Tukay, A, Balkaya, MC, Brantley, WA. Comparison of the bond strength of laser-sintered and cast base metal dental alloys to porcelain. Dent Mater 2008;24:1400–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2008.03.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Walker, MP. Dental materials and their selection. J Prosthodont 2003;12:152. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1059-941x(03)00047-0.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- An exploratory study of pilot EEG features during the climb and descent phases of flight

- Gesture recognition from surface electromyography signals based on the SE-DenseNet network

- Empirical analysis on retinal segmentation using PSO-based thresholding in diabetic retinopathy grading

- Prediction of remaining surgery duration based on machine learning methods and laparoscopic annotation data

- Caries-segnet: multi-scale cascaded hybrid spatial channel attention encoder-decoder for semantic segmentation of dental caries

- An analysis of initial force and moment delivery of different aligner materials

- Influence of microstructure on metal-ceramic bonding in SLM-manufactured titanium alloy crowns and bridges

- Design and evaluation of powered lumbar exoskeleton based on human biomechanics

- Evaluation of mesoporous polyaniline for glucose sensor under different pH electrolyte conditions

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- An exploratory study of pilot EEG features during the climb and descent phases of flight

- Gesture recognition from surface electromyography signals based on the SE-DenseNet network

- Empirical analysis on retinal segmentation using PSO-based thresholding in diabetic retinopathy grading

- Prediction of remaining surgery duration based on machine learning methods and laparoscopic annotation data

- Caries-segnet: multi-scale cascaded hybrid spatial channel attention encoder-decoder for semantic segmentation of dental caries

- An analysis of initial force and moment delivery of different aligner materials

- Influence of microstructure on metal-ceramic bonding in SLM-manufactured titanium alloy crowns and bridges

- Design and evaluation of powered lumbar exoskeleton based on human biomechanics

- Evaluation of mesoporous polyaniline for glucose sensor under different pH electrolyte conditions