Schizophrenia phenomenology comprises a bifactorial general severity and a single-group factor, which are differently associated with neurotoxic immune and immune-regulatory pathways

-

Michael Maes

, Aristo Vojdani

Abstract

In schizophrenia, a single latent trait underlies psychosis, hostility, excitation, mannerism, negative (PHEMN) symptoms, formal thought disorders (FTD) and psychomotor retardation (PMR). Schizophrenia is accompanied by a breakdown of gut and blood-brain-barrier (BBB) pathways, increased tryptophan catabolite (TRYCAT) levels, bacterial translocation, and lowered natural IgM and paraoxonase (PON)1 activity.

The aim of this study was to examine the factor structure of schizophrenia symptom domains and the biomarker correlates of these factors.

We recruited 80 patients with schizophrenia and 40 healthy subjects and assessed the IgA/IgM responses to paracellular/transcellular (PARA/TRANS) ratios, IgA responses to TRYCATs, natural IgM to malondialdehyde and Gram-negative bacteria, and PON1 enzymatic activity.

Direct Hierarchical Exploratory Factor Analysis showed a bifactorial oblique model with a) a general factor which loaded highly on all symptom domains, named overall severity of schizophrenia (“OSOS”); and b) a single-group factor (SGF) loading on negative symptoms and PMR. We found that 40% of the variance in OSOS score was explained by IgA/IgM to PARA/TRANS ratio, male sex and education while 36.9% of the variance in SGF score was explained by IgA to PARA/TRANS, IgM to Gram-negative bacteria, female sex (positively associated) and IgM to MDA, and PON1 activity (negatively associated).

Schizophrenia phenomenology comprises two biologically-validated dimensions, namely a general OSOS dimension and a single-group negative symptom dimension, which are associated with a breakdown of gut/BBB barriers, increased bacterial translocation and lowered protection against oxidation, inflammation and bacterial infections through lowered PON1 and natural IgM.

Introduction

Classically, it is considered that schizophrenia consists of various symptoms domains including positive symptoms (such as hallucination, delusions, hostility, excitation, and disorganized thinking), negative symptoms (such as flattening of affect, alogia, avolition, and anhedonia), and neurocognitive deficits (such as impairments in episodic and semantic memory as well as in executive functions) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Based on the presence of positive and negative symptoms, the phenomenology of schizophrenia is considered to be bi-dimensional with two subtypes namely, type I and II schizophrenia whereby type I is characterized by positive symptoms and type II by negative symptoms coupled with more profound neurocognitive deficits [4, 5, 6]. Deficit schizophrenia is classically defined by the presence of negative symptoms during the inter-episodic, more stable and acute phases of illness [6]. In fact, the bidimensional model of schizophrenia was already formulated in the 19th century by Eugene Bleuler who coined the term schizophrenia and considered two symptom clusters, a first accompanied by negative symptoms such as social withdrawal and loosening of associations and a second cluster with accessory symptoms comprising positive symptoms [7, 8]. Anno 2019, the NINH and NHS still classify patients with schizophrenia based on positive and negative symptoms [9, 10].

Recently, we established that, in stable phase schizophrenia, positive and negative symptoms cannot be considered to be two different dimensions because one single latent trait (latent vector) underlies both symptom domains and other key symptoms of schizophrenia, including formal thought disorders (disorders in concrete and abstract thought processes, including loosed associations, fluid thinking, illogical and disorganized thinking) and psychomotor retardation (including slow movements and motor responses and aberrations in gross and fine motor performance) [11, 12]. Moreover, we established that positive and negative symptom domains are not viable concepts as these constructs lack discriminatory power in partial least squares analysis and that positive symptoms should be dissected in more relevant symptom domains, namely psychosis (hallucinations, delusions), hostility, excitation and mannerism [11, 12]. Furthermore, in deficit schizophrenia and the combined group of controls and deficit schizophrenia, this latent vector underpinning negative symptoms, PHEM symptoms, FTD and PMR showed a very adequate internal consistency reliability, predictive relevance, and concurrent, and convergent validity while Confirmatory Tedrad Analysis showed that the latent vector fitted a reflective model [12]. As such, the score of this reflective latent construct is a reliable and replicable index of overall severity of schizophrenia (OSOS), which modulates the various symptom manifestations of OSOS [12]. Nevertheless, these findings await confirmation in other populations while no research has examined whether this latent trait also exists in subjects with deficit and non-deficit schizophrenia combined.

Already in the 1990s, it was conceptualized that schizophrenia is a neuro-immune disorder, characterized by a mild chronic inflammatory state, T cell activation and T helper (Th)-1 activation [13]. However, recently it became evident that schizophrenia is accompanied by activated M1 macrophage, T helper (Th)-1, Th-2, Th-17, and T regulatory (T cell) activation indicating activation of the immune-inflammatory response system (IRS) as well as the compensatory immune-regulatory system (CIRS) [14].

Some of these neuro-immune pathways are more pronounced in deficit than in non-deficit schizophrenia and predict a large part of the variance in PHEM and negative symptoms, FTD and PMR [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20], including increased IgA responses to noxious tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs), including picolinic acid (PA), xanthurenic acid (XA) and 3-OH-kynurenine (3OHK) [16]. Another pathway contributing to those symptom domains is breakdown of the paracellular tight and adherens junctions as measured with increased IgM/IgA responses to zonulin, occludin and E-cadherin versus the transcellular pathway cytoskeletal proteins as measured with IgM/IgA responses to talin, actin, vinculin and epithelial intermediate filament [17, 18]. Zonulin may increase gut permeability by loosening the tight junctions (TJ) barrier which, composed of occludin and claudin, join the gut epithelial cells together [19]. E-cadherin is a key component of the gut adherens junctions which further increase the stability of the epithelial gut barrier. Moreover, also the IgA responses to claudin-5, a key component of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) tight junctions, was increased especially in deficit schizophrenia, suggesting that not only the TJs of the gut barrier but also those of the BBB are damaged [17]. This is important as deficit schizophrenia is also accompanied by increased translocation of gut commensal Gram-negative bacteria as measured with IgA/IgM responses to LPS of Hafnia alvei, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Morganella morganii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Pseudomonas putida [20]. Deficit schizophrenia, but not non-deficit schizophrenia, is accompanied by lowered IgM responses to oxidative specific epitopes (OSEs) including malondialdehyde (MDA) indicating that this condition is characterized by lowered natural IgM antibodies, which are a key component of innate immunity [18]. These IgM antibodies are produced by innate-like B1 and marginal zone B cells and have immune-regulatory, housekeeping, and anti-oxidant properties thereby protecting against an overzealous IRS and bacterial infections [21, 22, 23, 24]. Finally, deficit schizophrenia is also accompanied by lowered activity levels of paraoxonase 1 (PON1) [Matsumoto et al., in preparation], a detoxifying and antioxidant enzyme that is strongly associated with high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) [25]. Interestingly, lowered natural IgM and PON1 activity are highly significantly associated with negative symptoms, but not with psychosis, hostility or mannerism [18], Matsumoto et al., in preparation). Such results may be difficult to reconcile with the existence of a single OSOS index which causes all manifestations. Moreover, no research has examined whether this OSOS index is mediated by neuro-immune biomarkers which to a large extent are associated with PHEM and negative symptoms.

Hence, this study was conducted to examine whether a) the key symptom domains of stable-phase schizophrenia belong to one single trait, namely an OSOS index, or whether multiple or bifactorial models better fit the data; and b) those factors are mediated by neuro- immune pathways including IgA/IgM responses to PARA/ TRANS pathways, IgA responses to PA, XA and 3HK, increased bacterial translocation, natural IgM to MDA, and PON1 activity.

Subjects and Methods

Participants

The present study recruited 80 patients with schizophrenia and 40 healthy controls who were recruited from the same catchment area, namely Bangkok, Thailand. Patients attended the Department of Psychiatry, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, while healthy controls were recruited by word of mouth among staff members or their family members or friends. Only patients with DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia were recruited when they were in a stabilized phase of the illness for at least one year. The diagnosis of deficit schizophrenia was made using the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS) [6] and schizophrenia patients not fulfilling these criteria were classified as non-deficit schizophrenia.

Exclusion criteria for patients were a) other axis-1 DSM-IV-TR disorders than schizophrenia, such as schizoaffective disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders and psycho-organic disorders; and b) participants who had psychotic episodes the year prior to the study. Exclusion criteria for controls were: a) a positive family history of psychosis, and b) a lifetime or current diagnosis of axis I DSM-IV-TR disorders. Exclusion criteria for controls and schizophrenia patients were: a) immune and auto-immune disease including psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and diabetes mellitus (type 1); b) neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disease including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease; c) a lifetime history of treatment with immunomodulatory drugs including glucocorticoids, methotrexate, and immunosuppressants; and d) current use of therapeutic dosages of antioxidants or ω3-polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Ethical approval: The study was conducted according to International and Thai ethics and privacy laws. Approval for the study (298/57) was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, which is in compliance with the International Guidelines for Human Research protection as required by the Declaration of Helsinki, The Belmont Report, CIOMS Guideline and International Conference on Harmonization on Good Clinical Practice.

Informed consent: Controls and patients, as well as the guardians of patients or parents or close family members gave written informed consent prior to participation in our study.

Clinical assessments

Using a semi-structured interview, a senior psychiatrist specialized in schizophrenia completed sociodemographic and clinical data including the drug state of the patients. On the same day, the same psychiatrists used the DSM-IV-TR criteria and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) in a validated Thai translation [26] to make the diagnosis of schizophrenia. The same psychiatrist also used the SDS criteria [6] to make the diagnosis of primary deficit schizophrenia. On the same day, the same psychiatrist assessed rating scales to score the severity of negative symptoms, namely the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) [27], and the negative subscale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANNS) [28]. PHEM symptoms, FTD and PMR were computed as z unit-weighted composite scores as explained previously [17, 19] and towards this end we also measured the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [29] and the Hamilton Depression (HAM-D) Rating Scale score [30]. The diagnosis of nicotine dependence was made using DSM-IV-TR criteria and body mass index (BMI) was assessed as body weight (kg) / length (m2).

Assays

Fasting blood was sampled at 8.00 a.m. in all participants for the assay of IgA/IgM directed to paracellular and transcellular pathway molecules, IgM to MDA, PON1 activity, IgA responses to PA, XA and 3HK, and IgM to Gram-negative bacteria. Zonulin, claudin-5, occludin, E-cadherin, actin, talin, vinculin, epithelial intermediate filament (keratin) were purchased from Bio-Synthesis Inc (Lewisville, TX USA), Abcam (Cambridge, MA USA), and Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO USA). IgA/IgA levels directed to those selected molecules were assayed using ELISA as previously described [17,19]. ELISA indices were computed using the following formula: antibody ELISA index = OD of tested Specimen minus OD of blank / OD of Calibrator minus OD of blank. Consequently, we computed the IgA to PARA/TRANS ratio as z(sum of z values of occludin + claudin-5 + E-cadherin) – z(sum of z values of talin + actin + vinculin + epithelial intermediate filament) and IgM to PARA/TRANS as z(sum of z values of occludin + zonulin) – z(sum of z values of talin + actin + vinculin). IgM to conjugated MDA was assayed as explained previously [18] using indirect ELISA tests [31, 32, 33]. IgA responses to conjugated PA, XA, and 3HK were performed using ELISA assay [34, 35]. PON1 (CMPAase) activity was assayed by measuring the activity against 4-(chloromethyl) phenylacetate (CMPA, Sigma, USA). CMPAase activity is affected by the PON1 Q192R polymorphism with the Q allozyme presenting low efficacy to metabolize CMPA (or paraoxon) and lowered CMPAase activity in schizophrenia reflects in part increased QQ genotype in deficit schizophrenia as well as lowered CMPAase activity independent from the genotype [36, 37]. IgM responses to Hafnia alvei, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Morganella morganii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Pseudomonas putida were assayed as described previously [20, 38]. We computed a z unit-weighted composite score reflecting overall LPS load in the serum, that is z(sum of z scores of all IgA responses to the 5 Gram-negative bacteria).

Statistics

We employed one-way analysis of variance to check differences in continuous variables between diagnostic and analysis of contingency tables (χ2 tests) to check associations between sets of nominal variables. Associations between two sets of scale variables were assessed using partial correlation coefficients with adjustment for relevant extraneous variables. Multivariate GLM analysis followed by tests for between-subject effects is used to assess the effects of diagnostic categories on a set of biomarkers while adjusting for relevant background variables. Multiple tests were always checked for false discovery rate (FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure [39]. In order to assess the associations between symptom factor scores and biomarkers we conducted multiple regression analysis using an automatic stepwise method with a p-to-entry of 0.05 and p-to-remove of 0.06 while evaluating the change in R2. All analyses were checked for multicollinearity using tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to explore the factor structure of the 8 symptom domains in patients with schizophrenia and in the combined group of patients and controls. We tested different models, namely EFA models either one or two-factor models, Schmid-Leiman orthogonalization and a pure Exploratory Bifactor Model with Promin rotation [40, 41]. FACTOR, windows version 10.5.03 was used to extract factors with the robust unweighted least squares (RULS) method with bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstraps (500 samples). We used the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity to assess sample and matrix’ factorization adequacy. The number of factors was determined using the Hull test and Parallel Analysis (Optimal Implementation). UNICO (unidimensional congruence), ECV (explained common variance) and MIREAL (mean of item residual absolute loadings) were employed to estimate closeness to unidimensionality whereby UNICO >0.95, ECV >0.85 and MIREAL<0.300 suggest unidimensionality. Goodness-of-fit levels were assessed using root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Schwarz’s Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI). The distribution of residuals was assessed using weighted root mean square of residuals (RMSR) with Kelley’s criterion (the expected RMSR for an acceptable model) and weighted root mean square residual (WRMR). The quality of the factor scores was estimated using the factor determinacy index (FDI) (>0.80 indicating adequate quality). The H index was used to assess stability across studies and construct replicability with values ≥0.80 indicating good replicability.

If EFA suggested that a unidimensional structure may underly the eight key domains further analyses were planned using Partial Least Squares (SmartPLS) path analysis conduced using PLS with structural equation modeling algorithms [42, 43]. PLS was used to examine a) associations between the latent vector (LV) extracted from the 8 symptom domains (in a reflective model) and the biomarkers, and b) the reliability and convergent validity of the main LV. Also, using a hierarchical component (reflective – reflective) model coupled with the repeated indicator approach [44], we examined the contribution of two symptom dimensions (PHEM plus FTS and negative symptoms plus PMR) to the LV extracted from the 8 key symptoms.

The biomarkers were entered as single indicator input variables while the LV extracted from the 8 symptom indicators was the output variable. Complete and consistent PLS path analysis was performed when the inner and outer model constructs complied with specific quality criteria, namely all indicators of the outer model should have factor loadings > 0.6 at p < 0.01; the model standardized root mean residual (SRMR) < 0.08; adequate discriminant validity as indicated by the Fornell-Larcker criterion and a Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio <0.9; and adequate construct and convergent validity as indicated by average variance extracted (AVE) > 0.500; Cronbach alpha > 0.750; rho_A >0.800 and composite reliability > 0.800. Using consistent PLS bootstrapping with 5000 bootstrap samples we then computed path coefficients with exact p-values (inner model) and t-values for the factor scores in the outer model. Blindfolding was employed to access the predictive validity using Q2 statistic of construct cross-validated redundancy or communality with Q2 > 0 indicating predictive relevance. Confirmatory Tedrad Analysis (CTA) was conducted to ascertain that our reflective model was not misspecified.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

Table 1 displays the demographic and clinical data of the schizophrenia patients and healthy controls participating in this study. This table shows that there are no differences in age, marital status, BMI and nicotine dependence between the two classes. There were significantly more males in the schizophrenia group as well as unemployed people. Years of education was somewhat lower in schizophrenia patients as compared with controls. The scores on all rating scales and the composite scores were significantly increased in schizophrenia as compared with healthy controls. After FDR p-correction for multiple testing, we could not find any associations between age and the 8 symptoms domains. The latter, however, were significantly and inversely associated with years of education (all p<0.01 after FDR p correction). Mann-Whitney U tests showed significantly higher scores on all 8 symptom domains (except PMR) in men as compared with women (all at p<0.01 after FDR p-correction). Mann-Whitney U tests did not show any significant differences in the 8 symptom domain scores between smokers and non-smokers.

Demographic and clinical data in normal controls and schizophrenia patients

| Variables | Controls | Schizophrenia | F/Ψ/X2 | df | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.4 (12.8) | 41.1 (11.02) | 2.73 | 1/118 | 0.101 |

| Sex (M/F) | 10/30 | 43/37 | 8.94 | 1 | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (4.3) | 24.5 (5.1) | 0.23 | 1/113 | 0.630 |

| Education (years) | 14.3 (4.9) | 12.3 (4.2) | 5.18 | 1/118 | 0.025 |

| Employment (N/Y) | 4/36 | 46/34 | 24.75 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Nicotine dependence (N/Y) | 38/2 | 75/5 | 0.025 | - | 0.783 |

| SANS total score | 0.5 (1.8) | 35.1 (23.8) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| PANSS negative subscale score | 7.0 (0.0) | 19.3 (10.4) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| Psychosis (z score) | -0.820 (0.003) | 0.415 (0.996) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| Hostility (z score) | -0.595 (0.001) | 0.301 (1.113) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| Excitation (z score) | -0.809 (0.009) | 0.404 (1.004) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| Mannerism (z score) | -1.144 (0.003) | 0.579 (1.623) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| FTD (z score) | -0.761 (0.007) | 0.385 (1.032) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| PMR (z score) | -0.771 (0.143) | 0.390 (1.021) | MWU | - | <0.001 |

| IgA PARA/TRANS (z score) | -0.851 0.208 | 0.008 0.177 | 23.10 | 1/106 | <0.001 |

| IgM PARA/TRANS (z score) | -0.544 0.226 | 0.209 0.193 | 18.42 | 1/106 | <0.001 |

| IgM MDA (z score) | 0.066 0.201 | -0.162 0.201 | 1.26 | 1/106 | 0.264 |

| Sum noxious TRYCATs (z score) | -1.325 0.617 | 0.362 0.525 | 10.13 | 1/106 | 0.002 |

| PON1 activity (U/mL) | 43.87 (2.01) | 37.08 (1.36) | 7.67 | 1/106 | 0.007 |

| IgM Gram-negative bacteria (z score) | -0.033 (0.161) | 0.017 (0.110) | 0.06 | 1/106 | 0.801 |

All results are shown as mean (SD)

A,B,C: pairwise comparisons among group means

MWU: Results of Mann-Whitney U test; BMI: body mass index

SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; PANSS: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; FTD: formal thought disorders;

PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation). IgA/IgM PARS/TRANS: IgA to paracellular / transcellular ratio; MDA: malondialdehyde; TRYCATs: tryptophan catabolites including picolinic acid + xanthurenic acid + 3-OH-kynurenine)

Table 1 shows also the measurements of the 6 biomarkers used in this study, namely the model-generated estimated marginal means (in z scores) after multivariate GLM analysis with age, sex, TUD and BMI as covariates. We found a significant association between schizophrenia and the 6 biomarkers (F=7.62, df=6/101, p<0.001; effect size=0.312) with increased IgA (effect size=0.179) and IgM (effect size=0.148) PARA/TRANS rations, IgA to sum noxious TRYCATs (effect size=0.087), CMPAase (effect size=0.067), but no significant differences in IgM responses to MDA and Gram-negative bacteria between patients and controls. These differences remained significant after p-correction. There were no significant effects of TUD (F=0.78, df=6/101, p=0.590), but a significant inverse effect of age on IgM to Gram-negative bacteria (12.27, df=1/106, p=0.001). Parameter estimates showed a significant effect of BMI on the IgA PARA/ TRANS ratio (t=-3.21, p=0.002; effect size=0.089). We also examined the effects of the drug state on the 6 biomarkers, but could not find effects of the use of risperidone (n=33), haloperidol (n=8), perphenazine (n=20), clozapine (n=9), antidepressants (n=25), mood stabilizers (n=12) and anxiolytics/hypnotics (n=26).

Correlations between the two negative symptom clusters and the other symptom domains

Table 2 displays the partial correlations between both total SANS and PANSS negative subscale scores and PHEM, FTD and PMR (after adjusting for age, sex, and education). In both the total study group and the schizophrenia group we found significant partial correlations between negative symptoms domains and all other symptom dimensions. There were also no effects of the drug state of the patients on those partial correlations.

Partial Correlation coefficients between negative symptoms as measured with the SANS (Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms) and the negative subscale of the PANSS (the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale) and other key symptoms of schizophrenia (SCZ)

| In controls and SCZ combined | In SCZ only | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domains | SANS | PANSSnegative | SANS | PANSSnegative |

| Psychosis | 0.714 | 0.761 | 0.570 | 0.661 |

| Hostility | 0.518 | 0.475 | 0.403 | 0.358* |

| Excitation | 0.812 | 0.852 | 0.723 | 0.791 |

| Mannerism | 0.617 | 0.581 | 0.474 | 0.445 |

| FTD | 0.563 | 0.591 | 0.373* | 0.443 |

| PMR | 0.827 | 0.862 | 0.749 | 0.814 |

The correlation coefficients were adjusted for age, sex, education.

All significant at p<0.0001; except *: significant at p<0.005

FTD: formal thought disorders; PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

Table 3 displays the results of exploratory factor analysis which was carried out in the total study sample and examined the factorability of the eight symptom clusters. Both the KMO value and Bartlett’s test (χ2=1173.4, df=28, p<0.00001) show that the sampling adequacy and

Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) performed on the eight key symptom dimensions of schizophrenia

| HC+SCZ | SCZ | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | BCa Factor loadings and 95% CI | |

| SANS | 0.896 (0.837-0.935) | 0.831 (0.726-0.894) |

| PANNSneg | 0.906 (0.841-0.943) | 0.865 (0.761-0.918) |

| Psychosis | 0.946 (0.912-0.973) | 0.907 (0.850-0.950) |

| Hostility | 0.709 (0.577-0.808) | 0.625 (0.439-0.735) |

| Excitation | 0.960 (0.926-0.977) | 0.945 (0.891-0.974) |

| Mannerism | 0.783 (0.681-0.862) | 0.677 (0.486-0.784) |

| FTD | 0.764 (0.664-0.830) | 0.642 (0.424-0.752) |

| PMR | 0.789 (0.710-0.854) | 0.694 (0.567-0.798) |

| Parameter values (500 bootstrap 95% CI) | ||

| % variance | 75.179 | 65.425 |

| Keiser-Meier-Olkin (KMO) test | 0.88909 (0.876-0.915) | 0.85185 (0.827-0.884) |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 151.668 (111.874-226.352) | 155.920 (109.010-227.448) |

| Comparative Fit index (CFI) | 0.968 (0.916-0.992) | 0.920 (0.802-0.981) |

| Root mean Square Error (RMSEA) | 0.152 (0.0801-0.2335) | 0.204 (1.094-0.2948) |

| Root Mean square of residuals Kelley’s criterion | 0.0799 (0.051-0.115) 0.0917 | 0.1148 (0.071-0.161) 0.1125 |

| Weighted Root Mean Square Residual | 0.2298 (0.141-0.339) | 0.2853 (0.171-0.427) |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.990 (0.978-0.996) | 0.975 (0.945-0.992) |

| Adjusted GFI (AGFI) | 0.987 (0.969-0.995) | 0.965 (0.923-0.988) |

| Unidimensional Congruence (UNICO) | 0.987 (0.973-0.996) | 0.968 (0.929-0.991) |

| Explained Common Variance (ECV) | 0.895 (0.851-0.936) | 0.838 (0.776-0.899) |

| Mean of Item Residual Absolute Loadings (MIREAL) | 0.268 (0.207-0.330) | 0.322 (0.245-0.387) |

| Generalized H index | 0.981 | 0.964 |

| Factor Determinacy index | 0.986 | 0.977 |

We performed two EFAs one on controls and patients combined (HC+SCZ) and a second in schizophrenia (SCZ) patients only Significant loadings (>0.6) are shown in bold; CI: confidence intervals

SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; PANSS: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; FTD: formal thought disorders;

PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation).

factorability of the correlation matrix are good. We found that one eigenvalue was greater than 1.0 (6.02063) and that the first factor explained 75.179% of the variance in the data set. The results of Parallel Analysis and the Hull test show that one factor fits the data set. Table 3 shows the UNICO, ECV and MIREAL values indicating that the data should be regarded as essentially unidimensional. All loadings of the eight symptom domains were > 0.707. The CFI, RMSR values and model fit indices (GFI and AGFI) showed that the model has an adequate fit while the Generalized H index and FDI values indicate adequate performance across studies (construct replicability) as well as the quality of the estimates of the factor scores estimates. Nevertheless, the RMSEA values indicated that the model was only moderately acceptable. All in all, this unidimensional vector indicates positive manifold with high loadings indicating that a general factor reflects the 8 manifestations and as such this factor is quite similar to the “overall severity of schizophrenia” (OSOS) factor described by Almulla et al. (2019). Nevertheless, this model may not explain all the covariation between the items.

Table 3 also shows the results of exploratory factor analysis performed in schizophrenia subjects. The KMO test and Bartlett’s test (χ2=594.4, df=28, p<0.00001) indicated that the factorability of the correlation matrix is adequate. Parallel Analysis and the Hull test indicated that one factor may be sufficient. The values of UNICO suggest that the data set should be considered to be unidimensional, whereas ECV and MIREAL values showed that the same data set is probably not unidimensional. The goodness of fit indices and the generalized H index and Factor Determinacy index were adequate, but the RMSR and RMSEA values did not perform well. As such, these models may not be the most adequate and, therefore, we have examined the single-group bifactor model with Pure EFA as well as a two-factor solution.

Table 4 shows the best models fitting the 8 symptom domains in the total study group and schizophrenia patients as well, namely a bidimensional oblique model with a general factor (GF) named overall severity of schizophrenia (OSOS GF) and a single-group factor (SGF), which loaded highly on both negative symptom domains and PMR. The construct replicability H index of both

Results of Pure Exploratory Bifactor analysis, bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap with 95% confidence intervals

| BCa Factor loadings and 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | All subjects combined (HC+SCZ) | SCZ only | ||

| Factors | Single-Group Factor | General Factor | Single-Group Factor | General Factor |

| SANS | 0.500 (0.364 / 0.618) | 0.782 (0.720 / 0.855) | 0.645 (0.346 / 1.010) | 0.693 (0.520 / 0.888) |

| PANNSneg | 0.591 (0.493 / 0.715) | 0.774 (0.734 / 0.822) | 0.681 (0.389/ 0.964) | 0.696 (0.595 / 0.813) |

| Psychosis | 0.096 (-0.017 / 0.179) | 0.964 (0.931 / 0.994) | -0.043 (-0.257 / 0.135) | 0.999 (0.990 / 1.023) |

| Hostility | -0.137 (-0.269/ 0.084) | 0.807 (0.711 / 0.874) | -0.011 (-0.167 / 0.439) | 0.719 (0.458 / 0.898) |

| Excitation | 0.311 (0.234 / 0.397) | 0.897 (0.855 / 0.937) | 0.174 (-0.141 / 0.330) | 0.974 (0.854 / 1.060) |

| Mannerism | -0.049 (-0.172 / 0.111) | 0.850 (0.763 / 0.903) | 0.056 (-0.037 / 0.316) | 0.743 (0.474 / 0.897) |

| FTD | 0.076 (-0.107 / 0.277) | 0.777 (0.660 / 0.855) | -0.224 (-0.875 / -0.051) | 0.717 (0.522 / 0.879) |

| PMR | 0.647 (0.552 / 0.750) | 0.642 (0.558 / 0.682) | 0.737 (0.586 / 1.045) | 0.487 (0.115 / 0.633) |

| Parameter values (500 bootstrap 95% CI) | ||||

| Variance | 1.150 | 5.337 | 1.508 | 4.731 |

| Bayesian Information Crite- rion (BIC) | 134.44 (115.822-162.751) | 116.426 (106.536-139.196) | ||

| Comparative Fit index (CFI) | 0.996 (0.977-1.006) | 1.00 (0.940-1.090) | ||

| Root mean Square Error (RMSEA) | 0.065 (0.0050-0.1500) | 0.001 (0.00-0.1518) | ||

| Root Mean square of resi- duals Kelley’s criterion | 0.0246 (0.014-0.035) 0.0917 | 0.0443 (0.001-0.084) 0.1125 | ||

| Weighted Root Mean Square Residual | 0.0610 (0.034-0.101) | 0.0243 (0.00-0.042) | ||

| ORION marginal reliability | 0.847 | 0.958 | 0.950 | 0.999 |

| Expected % of true differen- ces (EPTD) | 90.3% | 95.9% | 95.3% | 100% |

| Factor Determinacy index | 0.920 | 0.979 | 0.975 | 0.999 |

| Generalized H index | 0.858 (0.671-0.914) | 0.966 (0.946-0.995) | 0.950 (0.812-1.0) | 0.999 (0.953-1.062) |

We performed two bifactorial EFAs one on controls and patients combined (HC+SCZ) and a second in schizophrenia (SCZ) patients only Loadings (>0.6) are shown in bold; CI: confidence intervals

SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; PANSS: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; FTD: formal thought disorders;

PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation).

the first (SGF) and second (OSOS GF) order factors were adequate. The effectiveness of both factors as evaluated using the Factor Determinacy index, ORION marginal reliability and Expected percentage of true differences were all adequate. Moreover, RMRS and RMSEA values showed that the model fit of both models was more than acceptable. We have also examined whether a two-factor model could fit the data, but the model fit data were again less adequate, for example, the RMSEA for the combined group analysis was 0.116. All in all, a bifactorial solution fits the data well while the general factor is well defined by all domains and the SGF is defined by negative symptoms and PMR.

Associations between the clinical dimensions and biomarkers

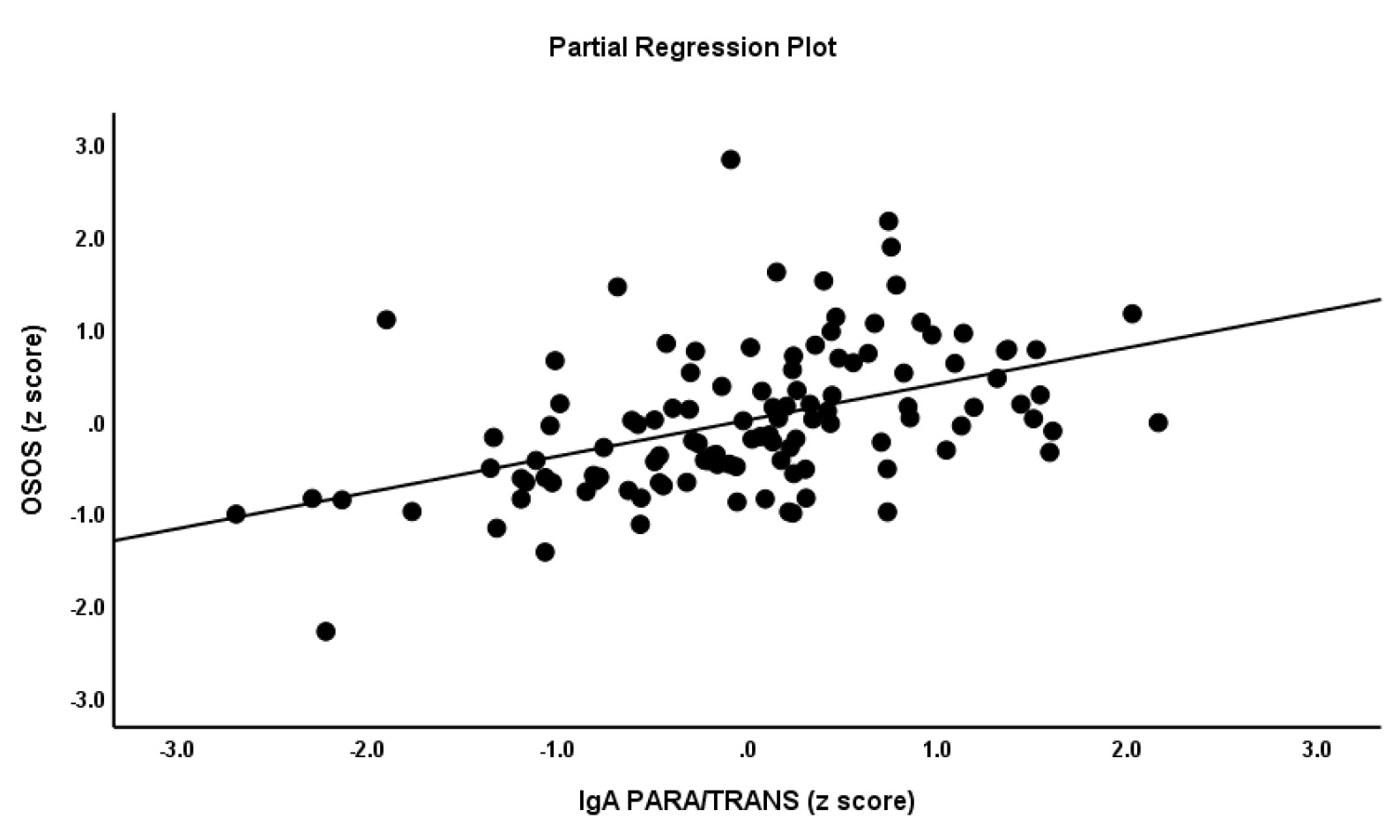

In order to further explore the associations between OSOS, OSOS GF and SGF and the biomarkers included here we have conducted multiple regression analyses with the factor scores as dependent variables and the 6 biomarkers, age, sex, BMI and TUD as explanatory variables (automatic step-up). The first regression in Table 5 shows that 51.3% of the variance in OSOS was explained by the regression on IgA/IgM PARA/TRANS, sum noxious TRYCATs (all positively), male sex and education (inversely). Figure 1 shows the partial regression plot of OSOS index on IgA to PARA/TRANS. The second multiple regression analysis conducted in all subjects showed that 40.4% of the variance in OSOS GF was explained by the regression on IgA/IgM PARA/TRANS (positively), male sex and education (negatively). The third multiple regression again preformed in all subjects shows that 36.9% of the variance in the SGF was explained by the regression on IgA PARA/TRANS and IgM to Gram-negative bacteria (all positively), IgM to MDA and PON1 (CMPAase) activity (negatively) and female sex. Regression #4 shows that 29.2% of the variance in the bifactorial OSOS GF was explained by the regression on IgA/IgM to PARA/TRANS and education. Regression #5 shows that 38.6% of the variance in SGF in schizophrenia was explained by IgA to PARA/TRANS and IgM to Gram-negative bacteria (positively), and PON1 (CMPAase) activity and IgM to MDA (inversely).

Partial regression plot of the general factor (GF) OSOS (overall severity of schizophrenia) on IgA to paracellular / transcellular ratio.

Results of multiple regression analyses with the (bifactorial) general factor (GF) OSOS (overall severity of schizophrenia) and the single group factor (SGF) as dependent variables and the biomarkers as explanatory variables.

| Dependent variables | Explanatory variables | β | t | p | F model | df | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1. GF OSOS in all subjects | Model | 23.67 | 5/111 | <0.001 | 0.513 | |||

| IgA PARA/TRANS | 0.397 | 5.60 | <0.001 | |||||

| IgM PARA/TRANS | 0.283 | 3.92 | <0.001 | |||||

| Male sex | 0.188 | 2.81 | 0.006 | |||||

| Education | -0.188 | -2.74 | 0.007 | |||||

| Sum noxious TRYCATs | 0.156 | 2.31 | 0.023 | |||||

| #2. Bifactorial GF OSOS in all subjects | Model IgM PARA/TRANS | 0.266 | 3.35 | 0.001 | 18.98 | 4/112 | <0.001 | 0.404 |

| IgA PARA/TRANS | 0.327 | 4.25 | <0.001 | |||||

| Male sex | 0.245 | 3.34 | 0.001 | |||||

| Education | -0.201 | -2.66 | 0.009 | |||||

| #3. Bifactorial SGF in all subjects | Model IgA PARA/TRANS | 0.285 | 3.47 | 0.001 | 12.97 | 5/111 | <0.001 | 0.369 |

| CMPAase | -0.263 | -3.42 | 0.001 | |||||

| IgM MDA | -0.381 | -4.08 | <0.001 | |||||

| IgM Gram-negative B | 0.201 | 2.27 | 0.025 | |||||

| Female sex | 0.166 | 2.10 | 0.038 | |||||

| #4. Bifactorial GF OSOS in SCZ only | Model IgM PARA/TRANS | 0.232 | 2.23 | 0.029 | 10.32 | 3/75 | <0.001 | 0.292 |

| Education | -0.298 | -3.03 | 0.003 | |||||

| IgA PARA/TRANS | 0.289 | 2.81 | 0.006 | |||||

| #5. SGF in SCZ only | Model | 11.65 | 4/74 | <0.001 | 0.386 | |||

| IgA PARA/TRANS | 0.287 | 2.91 | 0.005 | |||||

| CMPAase | -0.263 | -2.84 | 0.006 | |||||

| IgM MDA | -0.408 | -3.53 | 0.001 | |||||

| Sum Gram-negative B | 0.267 | 2.45 | 0.017 |

IgA/IgM: IgA to paracellular / transcellular ratio; MDA: malondialdehyde; CMPAase: paraoxonase 1 activity; TRYCATs: tryptophan catabolites including picolinic acid + xanthurenic acid + 3-OH-kynurenine)

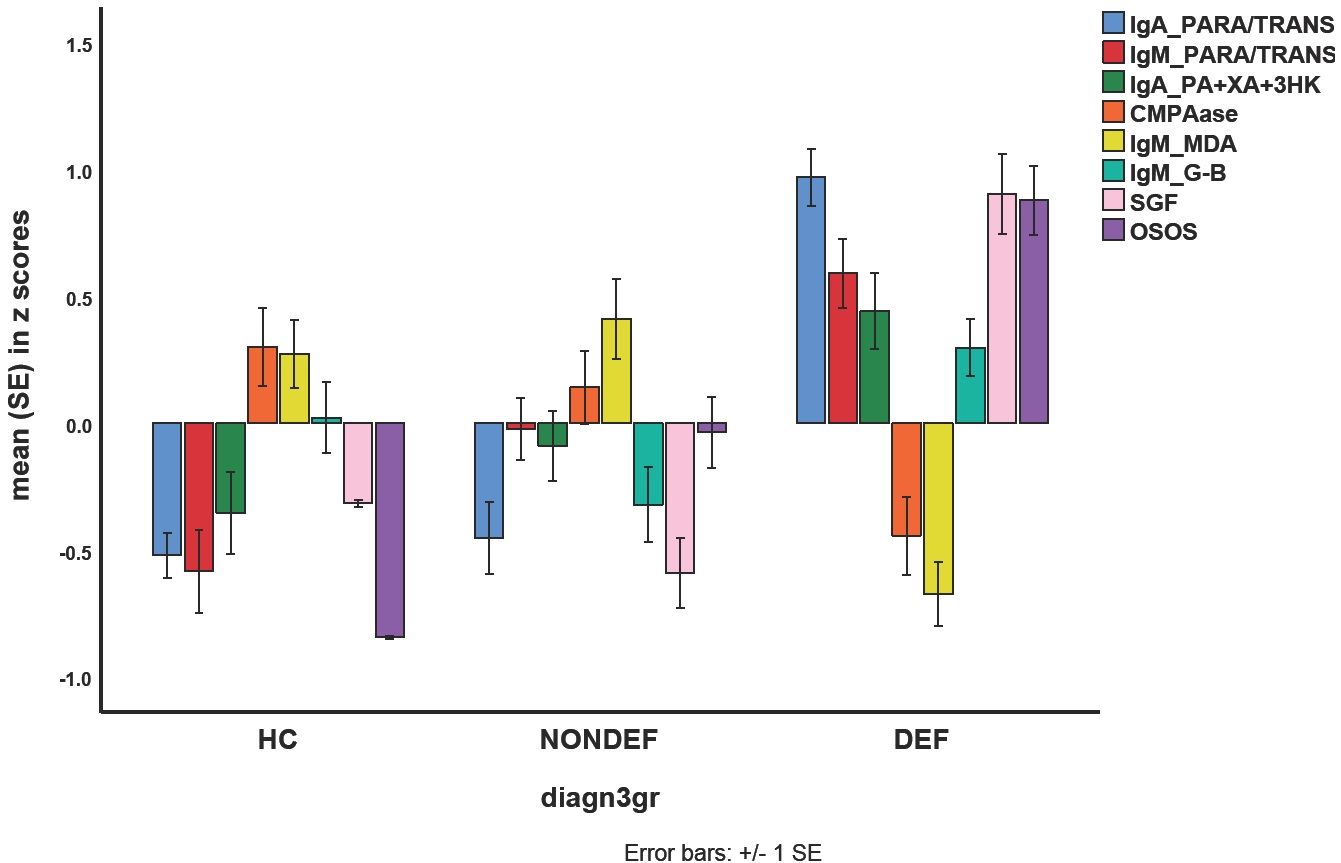

Figure 2 shows that the mean (SE) values of the biomarkers, OSOS and SGF (all in z scores) were significantly different between controls and schizophrenia patients with and without deficit (F=21.91, df=16/194, p<0.001; effect size=0.644), after considering the effects of age, sex, BMI, TUD and education in a multivariate GLM analysis. Tests for between-subject effects showed that OSOS GF and IgM to PARA/TRANS were significantly different between the three study groups and increased from controls to non-deficit to deficit schizophrenia. SGF, IgA to PARA/TRANS, IgA to TRYCATs, IgM to MDA and PON1 (CMPAase) were significantly different between deficit schizophrenia and controls and non-deficit schizophrenia, while IgM to Gram-negative bacteria was higher in deficit as compared with non-deficit schizophrenia.

Mean (SE) values of all biomarkers, the OSOS (overall severity of schizophrenia) general factor (GF) score, and the single-group factor score. IgA/IgM PARA/TRANS: IgA/IgM directed to paracellular / transcellular proteins; IgA PA+XA+3HK: IgA directed to the sum of three neurotoxic tryptophan catabolites, namely picolinic acid, xanthurenic acid, and 3-OH-kynurenine; CMPAase: paraoxonase (PON)1 (CMPAase) activity; IgM MDA: IgM directed to malondialdehyde; IgM G-B: IgM directed to Gram-negative bacteria; HC: healthy controls; NONDEF: non-deficit schizophrenia; DEF: deficit schizophrenia

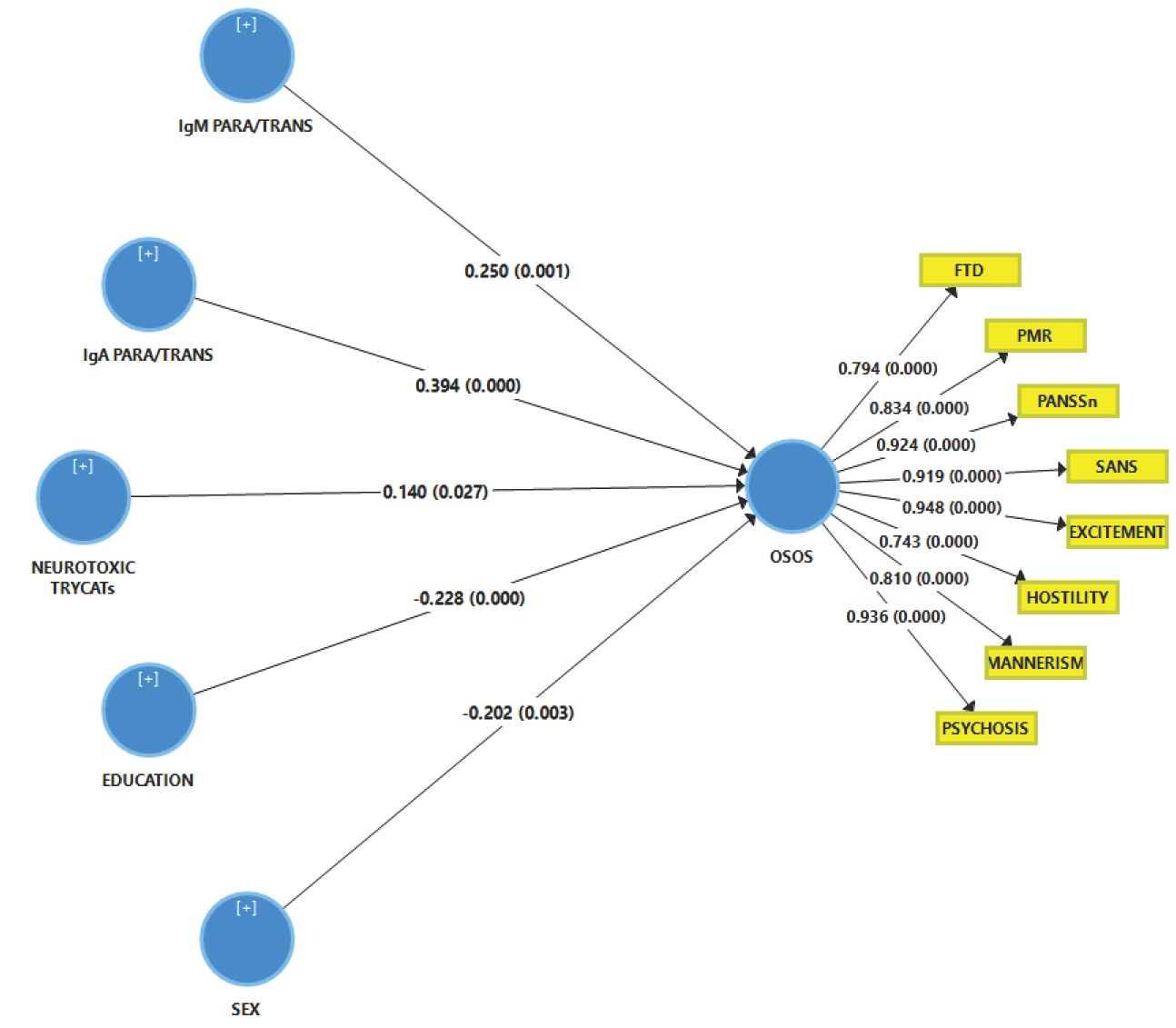

Results of PLS analysis

Figure 3 shows the outcome of a first PLS analysis conducted in the total study group with a latent vector (LV) extracted from the eight symptom domains as an output variable and the biomarkers, age, sex and education as input variables. The model quality data were adequate with SRMR=0.025 and excellent reliability data as shown in Table 6. All symptoms domains loaded highly on this LV (all loadings > 0.707 and all at p<0.0001). The construct cross-validated redundancy for OSOS LV was adequate (0.345) while the results of confirmatory Tetrad Analysis showed that the OSOS fitted a reflective model. We found that 50.3% of the variance in the LV extracted from the 8 symptom indicators was explained by IgA and IgM PARA/TRANS ratios and the sum of noxious TRYCATs (all positively), and education (negatively) and sex.

Results of Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis. This analysis is performed in the total study group with a latent vector extracted from the eight symptom domains as an output variable (named: overall severity of schizophrenia or OSOS) and the biomarkers, sex and education as input variables. SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; PANSS: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; FTD: formal thought disorders; PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation). IgA/IgM PARA/TRANS: IgA/IgM directed to paracellular / transcellular proteins; Neurotoxic TRYCATs (tryptophan catabolites): IgA PA+XA+3HK computed as IgA directed to the sum of the z scores of picolinic acid, xanthurenic acid and 3-OH-kynurenine. Shown are the path coefficients for the inner model and factor loadings for the outer model obtained by 5000 bootstrap samples.

Results of Partial Least Squares analysis

| Reliability data | ALL PARTICIPANTS | SCZ only |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (5000 bootstraps) (SD) | ||

| SANS | 0.919 (0.015) | 0.889 (0.018) |

| PANNSneg | 0.924 (0.015) | 0.918 (0.015) |

| Psychosis | 0.936 (0.015) | 0.870 (0.041) |

| Hostility | 0.743 (0.053) | 0.621 (0.087) |

| Excitation | 0.948 (0.010) | 0.919 (0.019) |

| Mannerism | 0.810 (0.046) | 0.678 (0.080) |

| FTD | 0.794 (0.040) | 0.641 (0.081) |

| PMR | 0.834 (0.029) | 0.795 (0.040) |

| Reliability data | ALL PARTICIPANTS | SCZ only |

| Model SRMR | 0.035 | 0.060 |

| Rho_A | 0.963 (0.006) | 0.958 (0.011) |

| Composite reliability | 0.960 (0.006) | 0.935 (0.013) |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.952 ((0.007) | 0.920 (0.014) |

| Average variance extracted | 0.752 (0.028) | 0.649 (0.044) |

We performed two PLS analyses: one in all subjects combined and a second in schizophrenia (SCZ) patients only

SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; PANSS: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; FTD: formal thought disorders; PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation). Significant Loadings (>0.6) are shown in bold

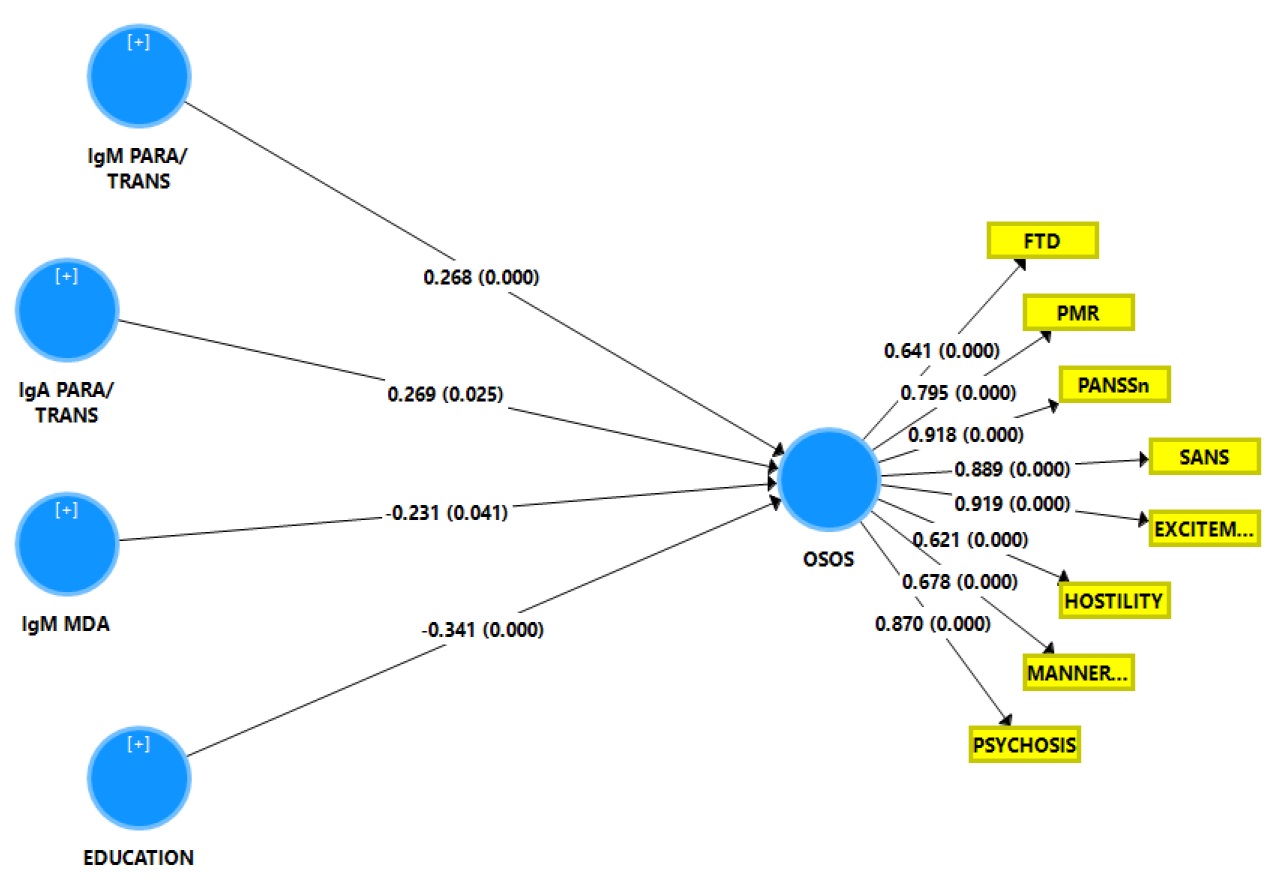

Figure 4 shows the results of a second PLS analysis with the same output and input variables as shown in the previous paragraph but now performed in the restricted group of schizophrenia patients. The quality data of the model showed an adequate SRMR while also the reliability data were very good. All symptom domains loaded significantly on this LV (all loadings > 0.6 and all p<0.0001). Blindfolding showed that the construct cross-validated redundancy of the OSOS LV was adequate (0.246) while Confirmatory Tetrad Analysis showed that the LV extracted from the 8 symptoms domains fitted a reflective model. PLS pathway analysis showed that 48.2% of the variance in the OSOS LV was explained by the regression on IgA and IgM PARA/TRANS ratios (both positively), IgM to MDA and education (both negatively).

Results of Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis. This analysis is performed in the schizophrenia study group with a latent vector extracted from the eight symptom domains as an output variable (named: overall severity of schizophrenia or OSOS) and the biomarkers, and education as input variables. SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; PANSS: the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; FTD: formal thought disorders; PMR: psychomotor retardation (see table 1 for computation). IgA/IgM PARA/TRANS: IgA/IgM directed to paracellular / transcellular proteins; IgM MDA: IgM values directed to malondialdehyde. Shown are the path coefficients for the inner model and factor loadings for the outer model obtained by 5000 bootstrap samples.

Discussion

The first major finding of this study is that the 8 key domains of schizophrenia phenomenology (SANS and PANSS negative, PHEM symptoms, FTD and PMR) are most appropriately modeled using a bi-dimensional oblique solution with a general factor (GF) that reflects overall severity of illness (OSOS GF) and a single-group factor (SGF) reflecting negative symptoms and PMR. The current findings that a general factor (OSOS or OSOS GF) reflect the data is in agreement with a previous study performed on Iraq patients reporting that a single latent trait, which is essentially unidimensional, underpins the key domains of schizophrenia [12]. Importantly, when we performed the same bifactorial analysis on the restricted study group of schizophrenia patients a similar bifactorial exploratory solution with OSOS GF and SGF was found. Also, the Iraq study [12] reported that in the restricted study group of patients with deficit schizophrenia a similar general OSOS could be detected. These results show that the same OSOS factor exists in Thai and Iraq study groups and in restricted study samples as well. It should be stressed that restricted sample variability attenuates the actual relationships between the variables as well as the factor generalizability and that those correlation coefficients computed in such restricted samples should be corrected for range restriction [12, 45, 46]. As such, future research should validate the OSOS construct in unrestricted study samples (controls and patients including deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia) in other continents.

Nevertheless, a new finding of this study is that negative symptom domains (namely SANS and PANSS negative) and PMR grouped together and shared enough common variance to shape an SGF. A frequent finding in psychological sciences is the situation where items are essentially unidimensional while a smaller group of items share common variance [41]. One example is Rotter’s Locus of Control Scale, which was conceptualized as a unidimensional scale, but showed very discrepant factor analysis results ranging from solutions with 2-9 factors versus a unidimensional solution [41]. Nevertheless, using the Pure Bifactorial EFA method, which we also used in the current study, the developers of this method observed that a single-group bifactorial model was the most appropriate solution, which comprised a general factor running through all locus of control items and an SGF reflecting previously identified items, that is a political factor [41]. In fact, the current study revealed a similar solution indicating that schizophrenia phenomenology consists of an OSOS GF and a subgroup of items that previously was conceptualized as a separate dimension, namely the negative symptom items.

Nevertheless, a significant difference between the current study and that of Almulla et al. [12] is that the latter established a unidimensional solution and could not retrieve the SGF. This difference may be explained by differences in schizophrenia phenomenology between Thai and Iraq patient samples and most importantly by differences in clinical symptoms and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Thus, here we included patients with non-deficit and deficit schizophrenia, whereas Almulla et al. [12] included only patients with deficit schizophrenia who were, in addition, more severely ill. Moreover, in the current study, we excluded subjects with signs of major depression, whereas Almulla et al. [12] included those with secondary (but not primary) depression.

The second major finding of this study is that the single latent trait that we extracted from the eight key domains showed good composite reliability and internal consistency reliability, that the model converged to an adequate result and that it shows adequate construct replicability. As such, this latent trait shows adequate psychometric properties indicating that this general factor represents a replicable and reliable score of OSOS. As in the Iraq study [12], we found, using Tetrad Analysis, that the latent trait OSOS was reflectively measured and, therefore, should be regarded as the cause of its eight manifestations (SANS and PANSS negative, PHEM symptoms, FTD and PMR), which are to a large extent mediated by OSOS.

Our findings that the phenomenology of schizophrenia is most appropriately modeled by a bifactorial model contrasts the current theory that a two-dimensional concept consisting of positive and negative symptoms is most appropriate [4, 47]. The NINH and NHS still maintain that the symptoms of schizophrenia fall into three domains namely positive and negative symptoms and cognitive deficits [9, 10]. It is suggested that positive symptoms may be related to aberrations in the dopamine systems in the mesolimbic circuits while dopaminergic aberrations in the mesocortical circuits may be associated with negative symptoms [48]. Nevertheless, previous studies also concluded that based on speech disorders the dichotomy between positive and negative symptoms may not be that clear [49]. Nevertheless, the concept “positive symptoms” has in our opinion no validity as it cannot be discriminated from the negative symptom domain and because it should be dissected into its relevant domains including psychosis, hostility ad excitation [12]. The current findings also help to interpret our previous results that deficit schizophrenia is a qualitatively distinct nosological entity modelled by negative and PHEM symptoms (qualitative theory) whereas the severity of these symptom domains (OSOS) increases along a continuum from non-deficit to deficit schizophrenia (quantitative theory) indicating simultaneous qualitative and quantitative differences between both diagnostic groups [50, 51]. Thus, the current results show that as OSOS increases along a continuum from “normal” to non-deficit and then to deficit schizophrenia the SGF items (negative symptoms and PMR) appear in subjects with deficit schizophrenia and become more prominent to group together and coupled with increasing severity of PHEM symptoms and FTD shape a distinct nosological entity [50, 51].

The third major finding of this study is that both the OSOS and SGF were validated by different biomarkers whereby OSOS was strongly associated with IgA/IgM responses to PARA/TRANS ratio and increased IgA responses to PA, XA, and 3HK, whereas the SGF was additionally associated with lowered natural IgM to MDA and PON1 activity as well as increased IgM responses to Gram-negative bacteria. As explained previously, the appearance of IgA/IgM antibodies to zonulin or paracellular proteins, which are key components of tight and adherens junctions, indicates a breakdown of the paracellular pathway in the gut and BBB barriers [17, 19, 52]. Previously, there were some reports that the gut may play a role in schizophrenia as indicated by, for example, altered patterns of bacterial translocation of Gram-negative bacteria [53, 54], although we showed that the breakdown of the gut-barrier is confined to deficit schizophrenia [17,19]. Moreover, alterations in Toxoplasma gondii and Candida albicans could be involved [53,54]. Increased IgA responses to PA, XA, and 3HK suggest increased production of those TRYCATs, which all three together may cause excitotoxic and neurotoxic effects thereby playing a role in the neuroprogressive pathophysiology of schizophrenia [16]. Moreover, it is possible that IgA responses to those TRYCATs may exert adverse effects in their own right. Previously, it was ascertained that immune activation in schizophrenia is associated with activation of the TRYCAT pathway whereby kynurenic acid (KA) is increased in the brain resulting in adverse effects on, for example, neurocognive functions [55]. Nevertheless, our results show that activation of the TRYCAT pathway occurs in deficit schizophrenia and is accompanied by increased levels of neurotoxic TRYCATs suh as PA, XA, and 3HK, whereas increased KA levels do not appear to be involved [16].

Natural IgM is a key factor of the innate immune system and has strong antioxidant and immune-regulatory effects and functions as a first-line defense against Gram-negative bacteria [24, 56, 57]. By inference, lowered natural IgM may be accompanied by a greater inflammatory potential and greater impact of gut commensal Gram-negative bacteria once they are translocated from the gut lumen through loosened gut barriers [20]. PON1 is an enzyme with strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [25] and lowered levels in schizophrenia are accompanied by increased immune responses [58, 59]. Moreover, PON1 has quorum quenching properties thereby attenuating quorum sensing of Gram-negative bacteria (including P. aeruginosa) through the enzymatic impact on N-acyl homoserine lactones [60, 61]. As such, PON1 may be considered to be part of the innate immune system protecting against Gram-negative bacteria and, therefore, lowered levels of PON1 activity may be accompanied by aggravated immune responses and increased translocation of Gram-negative bacteria.

All in all, increased products of activated M1, Th-1, Th-2 and Th-17 cells may impact OSOS through neurotoxic effects exerted by increased levels of cytokines/chemokines such as CCL-11, CCL-2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-13 [14], and neurotoxic TRYCATs such as PA, XA and 3HK [16]. Moreover, lowered innate immune protection against Gram-negative bacteria and inflammatory processes through lowered natural IgM [18] and PON1 activity [25, 60, 61] together with upregulated gut paracellular pathways [17, 19] may explain the greater impact of gut commensal bacteria on the SGF. Furthermore, as explained previously, increased production of some neurotoxic products in schizophrenia (including CCL-11 and neurotoxic TRYCATs) may be associated with damage to the tight junctions of the BBB [17] thereby allowing the entrance of greater amounts of neurotoxic substances into the brain [17]. The findings that positive as well and negative symptoms have an immune substrate contrast the current theories that disorders in dopaminergic and other neurotransmitters are the main determinants of these symptoms [62, 63]. Our results that all 8 symptoms assessed here belong to one latent dimension that may be predicted by immune biomarkers also contrast with previous theories that negative symptoms are secondary to positive symptoms, poor social support, depression, use of antipsychotics, or lack of environmental stimuli [64].

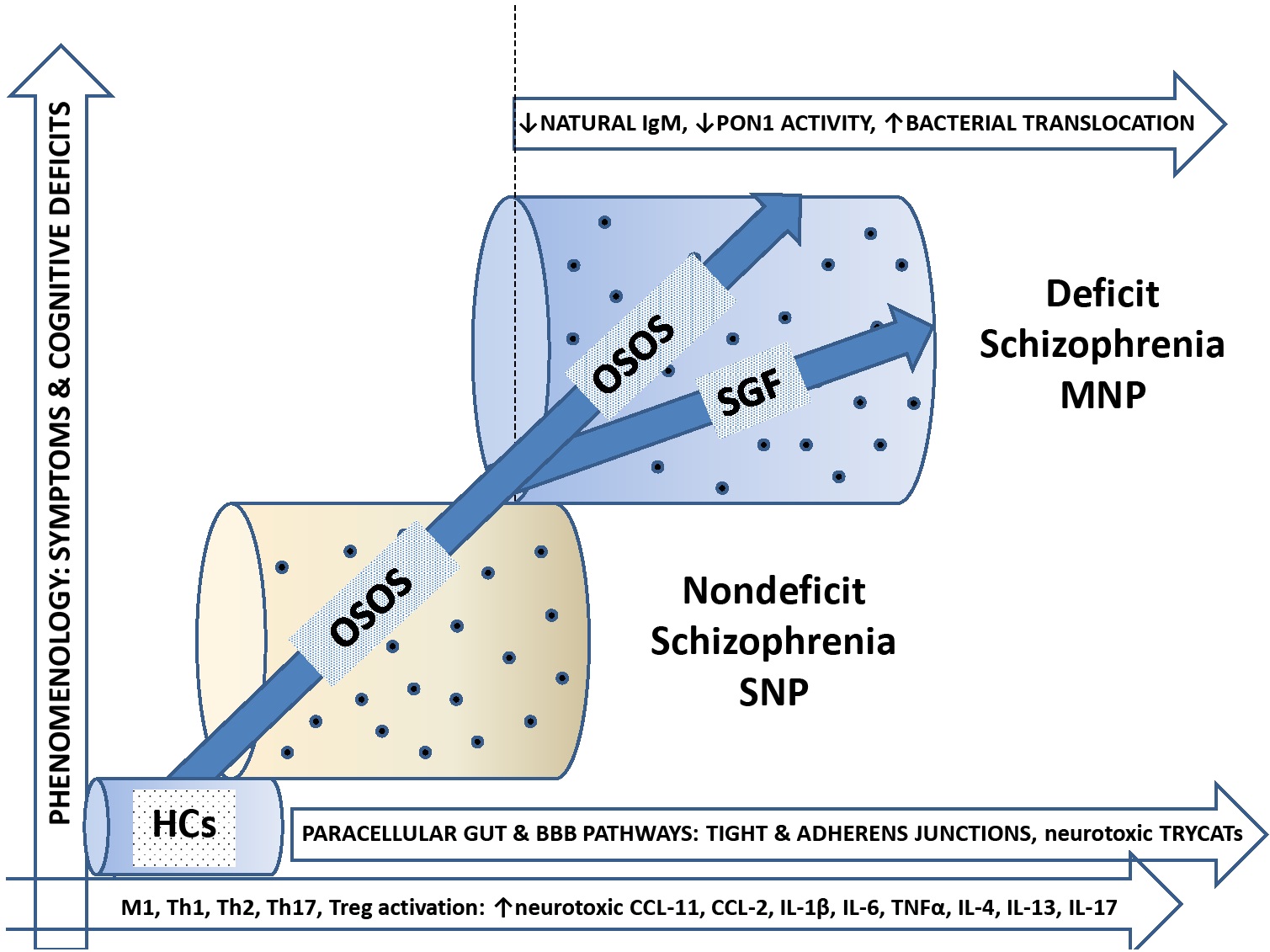

In conclusion, schizophrenia phenomenology comprises two biologically-validated dimensions, namely a general dimension, which reflects OSOS, and an SGF, which reflects negative symptoms and PMR. The general OSOS dimension is associated with a breakdown of the gut and BBB paracellular tight and adherens junctions and increased levels of noxious TRYCATs while the SGF is associated with deficits in innate immunity as indicated by lowered natural IgM and PON1 activity coupled with an increased impact of Gram-negative bacteria. Figure 5 shows an integration of the findings of the present study with our previous results that deficit schizophrenia (or MNP) is a qualitatively distinct nosological entity than non-deficit schizophrenia (or SNP). Thus, the current study shows that OSOS increases along a continuum from normals à non-deficit schizophrenia à deficit schizophrenia in association with indicants of increased neurotoxic potential (noxious TRYCATs and M1, Th-1, Th-2, and Th-17 cytokines) and damage to the tight/adherens junctions of the gut/BBB barriers. As OSOS increases along a continuum, the SGF items (negative symptoms and PMR) appear and become more prominent, and coupled with increasing severity of FTD and PHEM symptoms shape a distinct nosological entity, namely deficit schizophrenia. Lowered levels of natural IgM and PON1 activity may predispose towards SGF symptoms and, therefore, deficit schizophrenia by increasing the neurotoxic impact of immune products and Gram-negative bacteria. As such, OSOS increases along a continuum (continuum theory), whereas deficits in innate immunity (lower natural IgM and PON1 activity) and the associated SGF shape deficit schizophrenia as a qualitatively distinct entity.

The bifactorial factor model, deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia. OSOS: General factor overall severity of schizophrenia; SGF: single-group factor; BBB: blood brain barrier; TRYCATs: tryptophan catabolites; M1 macrophage; Th: T helper; IL: interleukin; MNP: major neuro-cognitive psychosis; SNP: simple neuro-cognitive psychosis; HC: healthy controls

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Asahi Glass Foundation, Chulalongkorn University Centenary Academic Development Project and Ratchadapiseksompotch Funds, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, grant numbers RA60/042 (to BK) and RA61/050 (to MM).

Conflict of interest: Michael Maes is the member of Biomolecular Concept’s Editorial Advisory Board.

Author’s contributions: All the contributing authors have participated in the manuscript. BK and MM designed the study. BK recruited patients and completed diagnostic interviews and rating scale measurements. MM carried out the statistical analyses. All authors (BK, MM, SS, AV, MG, EGM, DSB, APM, LOS) contributed to interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

1 Marneros A, Deister A, Rohde A. Affective, schizoaffective and schizophrenic psychoses. A comparative long-term study. Monogr Gesamtgeb Psychiatry Psychiatry Ser. 1991;65:1-454.Suche in Google Scholar

2 Mellor CS. Methodological Problems in Identifying and Measuring First-Rank Symptoms of Schizophrenia. In: Marneros A., Andreasen N.C., Tsuang M.T. (eds) Negative Versus Positive Schizophrenia. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 1991.10.1007/978-3-642-76841-5_5Suche in Google Scholar

3 Burton N. Living with Schizophrenia, (2ndEdn) Oxford :Acheron Press, p3; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

4 Crow TJ. The Two-Syndrome Concept: Origins and Current Status. Origins 1985;11:471–88.10.1093/schbul/11.3.471Suche in Google Scholar

5 Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A confirmatory factor analysis of competing models. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152(10):1450-7.10.1176/ajp.152.10.1450Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6 Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, Alphs LD, Carpenter WT Jr. The Schedule for the Deficit syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989,30:119-23.10.1016/0165-1781(89)90153-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7 Bleuler, E Dementia Praecox, or the Group of Schizophrenias. (1911) Translated by J. Zinkin. New York: International Universities Press; 1950.Suche in Google Scholar

8 Jablensky A. The diagnostic concept of schizophrenia: its history, evolution, and future prospects. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:271–87.10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/ajablenskySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

9 NHS. 2019. As assessed June 14, 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/schizophrenia/symptoms/Suche in Google Scholar

10 NIHM. Schizophrenia. As assessed June 14, 2019. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtmlSuche in Google Scholar

11 Maes M, Sirivichayakul S, Kanchanatawan B, Carvalho AF. In Schizophrenia, Psychomotor Retardation is Associated with Executive and Memory Impairments, Negative and Psychotic Symptoms, Neurotoxic Immune Products and Lower Natural IgM to Malondialdehyde. Preprints 2019, 2019010108 (doi: 10.20944/preprints201901.0108.v1).10.20944/preprints201901.0108.v1Suche in Google Scholar

12 Almulla A, Al-Hakeim H, Maes M. Schizophrenia Phenomenology Revisited: Positive and Negative Symptoms are Strongly Related Reflective Manifestations of an Underlying Single Trait Indicating Overall Severity of Schizophrenia. Preprints 2019, 2019070147 (doi: 10.20944/preprints201907.0147.v1).10.20944/preprints201907.0147.v1Suche in Google Scholar

13 Smith RS, Maes M. The macrophage-T-lymphocyte theory of schizophrenia: additional evidence. Med Hypotheses. 1995;45(2):135-41.10.1016/0306-9877(95)90062-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Roomruangwong C, Noto C, Kanchanatawan B, Anderson G, Kubera M, Carvalho AF, Maes M. The Role of Aberrations in the Immune-inflammatory Reflex System (IRS) and the Compensatory Immune-regulatory Reflex System (CIRS) in Different Phenotypes of Schizophrenia: The IRS-CIRS Theory of Schizophrenia. Preprints 2018, 2018090289, doi: 10.20944/preprints201809.0289.v1.10.20944/preprints201809.0289.v1Suche in Google Scholar

15 Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Ruxrungtham K, Carvalho AF, Geffard M, Anderson G, et al. Deficit Schizophrenia Is Characterized by Defects in IgM-Mediated Responses to Tryptophan Catabolites (TRYCATs): a Paradigm Shift Towards Defects in Natural Self-Regulatory Immune Responses Coupled with Mucosa-Derived TRYCAT Pathway Activation. Mol Neurobiol 2018;55(3):2214-26.10.1007/s12035-017-0465-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

16 Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Ruxrungtham K, Carvalho AF, Geffard M, Ormstad H, et al. Deficit, but Not Nondeficit, Schizophrenia Is Characterized by Mucosa-Associated Activation of the Tryptophan Catabolite (TRYCAT) Pathway with Highly Specific Increases in IgA Responses Directed to Picolinic, Xanthurenic, and Quinolinic Acid. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(2):1524-36.10.1007/s12035-017-0417-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17 Maes M, Sirivichayakul S, Kanchanatawan B, Vodjani A. Breakdown of the paracellular tight and adherens junctions in the gut and blood brain barrier and damage to the vascular barrier in patients with deficit schizophrenia. Neurotox Res. 2019;doi: 10.1007/s12640-019-00054-6.10.1007/s12640-019-00054-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18 Maes M, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Carvalho AF. In Schizophrenia, Deficits in Natural IgM Isotype Antibodies Including those Directed to Malondialdehyde and Azelaic Acid Strongly Predict Negative Symptoms, Neurocognitive Impairments, and the Deficit Syndrome. Mol Neurobiol. 2018; Nov 27. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1437-6.10.1007/s12035-018-1437-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19 Maes M, Sirivichayakul S, Kanchanatawan B, Vodjani A. Upregulation of the Intestinal Paracellular Pathway with Breakdown of Tight and Adherens Junctions in Deficit Schizophrenia. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;Apr 10. doi: 10.1007/ s12035-019-1578-2. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30972627.10.1007/s12035-019-1578-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20 Maes M, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Carvalho AF. In Schizophrenia, Increased Plasma IgM/IgA Responses to Gut Commensal Bacteria Are Associated with Negative Symptoms, Neurocognitive Impairments, and the Deficit Phenotype. Neurotox Res. 2019;35(3):684-698.10.1007/s12640-018-9987-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

21 Thiagarajan D, Frostegård AG, Singh S, Rahman M, Liu A, Vikström M, et al. Human IgM Antibodies to Malondialdehyde Conjugated With Albumin Are Negatively Associated With Cardiovascular Disease Among 60-Year-Olds. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;20;5(12).10.1161/JAHA.116.004415Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22 McMahon M, Skaggs B. Autoimmunity: Do IgM antibodies protect against atherosclerosis in SLE? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(8):442-4.10.1038/nrrheum.2016.108Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Aziz M, Holodick NE, Rothstein TL, Wang P. The role of B-1 cells in inflammation. Immunol Res. 2015;63:153-66.10.1007/s12026-015-8708-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24 Weismann D, Binder CJ. The innate immune response to products of phospholipid peroxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818(10):2465-75.10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.01.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25 Moreira EG, Boll KM, Correia DG, Soares JF, Rigobello C, Maes M. Why Should Psychiatrists and Neuroscientists Worry about Paraoxonase 1? Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018; Dec 27. doi: 10.217 4/1570159X17666181227164947. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30592255.10.2174/1570159X17666181227164947Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26 Kittirathanapaiboon P, Khamwongpin M. The Validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) Thai Version. J Mental Health of Thailand. 2005;13(3):125-35.Suche in Google Scholar

27 Andreasen NC. The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Brit J Psychiatry suppl. 1989;7:49-58.10.1192/S0007125000291496Suche in Google Scholar

28 Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:26176.10.1093/schbul/13.2.261Suche in Google Scholar

29 Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psycholog Rep. 1962;10:799-812.10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799Suche in Google Scholar

30 Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31 Amara A, Constans J, Chaugier C, Sebban A, Dubourg L, Peuchant E, et al. Autoantibodies to malondialdehyde-modified epitope in connective tissue diseases and vasculitides. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101(2):233-8.10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb08344.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Faiderbe S, Chagnaud JL, Geffard M. Anti-phosphoinositide auto-antibodies in sera of cancer patients: isotypic and immunochemical characterization. Cancer Lett 1992;66(1):35-41.10.1016/0304-3835(92)90277-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33 Geffard M, Bodet D, Martinet Y, Dabadie MP. Detection of the specific IgM and IgA circulating in sera of multiple sclerosis patients: interest and perspectives. Immuno-Analyse & Biology Specification. 2002;17:302-310.Suche in Google Scholar

34 Duleu S, Mangas A, Sevin F, Veyret B, Bessede A, Geffard M. Circulating Antibodies to IDO/THO Pathway Metabolites in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;15;2010. pii: 501541.10.4061/2010/501541Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35 Roomruangwong C, Kanchanatawan B, Sirivichayakul S, Anderson G, Carvalho AF, Duleu S, et al. IgA / IgM responses to Gram-negative bacteria are not associated with prenatal depression, but with physio-somatic symptoms and activation of the tryptophan catabolite pathway at the end of term and postnatal anxiety. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2017;April 7. [Epub ahead of print].10.2174/1871527316666170407145533Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36 Furlong CE, Holland N, Richter R, Bradman A, Ho A, Eskenazi A. PON1 Status of Farmworker Mothers and Children as a Predictor of Organophosphate Sensitivity. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 2006;16(3):183–90.10.1097/01.fpc.0000189796.21770.d3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37 Richter RJ, Furlong C. Determination of Paraoxonase (PON1) Status Requires More than Genotyping. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:745–53.10.1097/00008571-199912000-00009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38 Geffard M, Bodet D, Martinet Y, Dabadie M-P. Intérêt de l’évaluation d’IgM et d’IgA spécifiques circulant dans le serum de malades atteints de sclérose en plaques (SEP). Immuno-analyse Biol Spécialisée. 2002;17:302–310. doi: 10.1016/ S0923-2532(02)01214-010.1016/S0923-2532(02)01214-0Suche in Google Scholar

39 Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Statistics Soc Series b (Methodological) 1995;57:289-300.10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.xSuche in Google Scholar

40 Ferrando PJ, Lorenzo-Seva U. Program FACTOR at 10: Origins, development and future directions. Psicothema. 2017;29:236– 240.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41 Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. A General Approach for Fitting Pure Exploratory Bifactor Models. Multivariate Behav Res. 2019;54(1):15-30.10.1080/00273171.2018.1484339Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42 Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker J-M. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.smartpls.comSuche in Google Scholar

43 Cepeda-Carrion G, Cegarra-Navarro J-G, Cillo V. Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. J Knowledge Management. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-05-2018-032210.1108/JKM-05-2018-0322Suche in Google Scholar

44 Garson GD. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models. Statistical Associates Publishing: Blue Book Series, School of Public & International Affairs, North Carolina State University; 2016. Ebook. http://www.statisticalassociates.com/pls-sem_p.pdf As assessed June 5, 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

45 Wiberg M, Sundstrom A. A comparison of two approaches to correction of restriction of range in correlation analysis. Practic Assessm Res Evaluat. 2009;14(5):1-9.Suche in Google Scholar

46 Lakes KD. Restricted sample variance reduces generalizability. Psychol Assess. 2013;25(2):643-50.10.1037/a0030912Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47 Roy MA, DeVriendt X. Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a current overview. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39(7):407-14.10.1177/070674379403900704Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48 Carlson, NR. Physiology of Behavior (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson. 2013. ISBN 978-0205239399.Suche in Google Scholar

49 Allen HA. Do positive symptom and negative symptom subtypes of schizophrenia show qualitative differences in language production? Psychol Med. 1983;13(4):787-97.10.1017/S0033291700051497Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50 Kanchanatawan B, Sriswasdi S, Thika S, Sirivichayakul S, Carvalho AF, Geffard M, et al. Deficit schizophrenia is a discrete diagnostic category defined by neuro-immune and neurocognitive features: results of supervised machine learning. Metab Brain Dis. 2018;33(4):1053-67.10.1007/s11011-018-0208-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

51 Kanchanatawan B, Sriswasdi S, Thika S, Stoyanov D, Sirivichayakul S, Carvalho AF, et al. Towards a new classification of stable phase schizophrenia into major and simple neuro-cognitive psychosis: Results of unsupervised machine learning analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:879-91.10.1111/jep.12945Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52 Vojdani A, Vojdani E. Food-associated autoimmunities: when food turns your immune system against you. First Edition, Autoimmunity, A&G Wilshire, LLC; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

53 Severance EG, Prandovszky E, Castiglione J, Yolken RH. Gastroenterology issues in schizophrenia: why the gut matters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(5):27.10.1007/s11920-015-0574-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54 Severance EG, Yolken RH. From Infection to the Microbiome: An Evolving Role of Microbes in Schizophrenia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1007/7854_2018_84.10.1007/7854_2018_84Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55 Müller N, Myint AM, Schwarz MJ. Kynurenine pathway in schizophrenia: pathophysiological and therapeutic aspects. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(2):130-6.10.2174/138161211795049552Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

56 Binder CJ. Naturally occurring IgM antibodies to oxidation-specific epitopes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;750:2-13.10.1007/978-1-4614-3461-0_1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

57 Díaz-Zaragoza M, Hernández-Ávila R, Viedma-Rodríguez R, Arenas-Aranda D, Ostoa-Saloma P. Natural and adaptive IgM antibodies in the recognition of tumor-associated antigens of breast cancer (Review). Oncol Rep 2015;34:1106-1114.10.3892/or.2015.4095Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

58 Brinholi FF, Noto C, Maes M, Bonifácio KL, Brietzke E, Ota VK, et al. Lowered paraoxonase 1 (PON1) activity is associated with increased cytokine levels in drug naïve first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2015;166(1-3):225-30.10.1016/j.schres.2015.06.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

59 Noto C, Ota VK, Gadelha A, Noto MN, Barbosa DS, Bonifácio KL, et al. Oxidative stress in drug naïve first episode psychosis and antioxidant effects of risperidone. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:210-6.10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

60 Bar-Rogovsky H, Hugenmatter A, Tawfik DS. The evolutionary origins of detoxifying enzymes: the mammalian serum paraoxonases (PONs) relate to bacterial homoserine lactonases. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(33):23914-27.10.1074/jbc.M112.427922Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

61 Camps J, Pujol I, Ballester F, Joven J, Simó JM. Paraoxonases as potential antibiofilm agents: their relationship with quorum-sensing signals in Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(4):1325-31.10.1128/AAC.01502-10Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62 Morrison PD, Murray RM. The antipsychotic landscape: dopamine and beyond. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2018;8(4):127-35.10.1177/2045125317752915Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

63 Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III—the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):549-62.10.1093/schbul/sbp006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64 Mitra S, Mahintamani T, Kavoor AR, Nizamie SH. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25(2):135-44.10.4103/ipj.ipj_30_15Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2019 Michael Maes et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- ATP Synthase: Structure, Function and Inhibition

- Insulin Promotes Wound Healing by Inactivating NFkβP50/P65 and Activating Protein and Lipid Biosynthesis and alternating Pro/Anti-inflammatory Cytokines Dynamics

- Mini review

- The disordered boundary of the cell: emerging properties of membrane-bound intrinsically disordered proteins

- Research Article

- Expression of OX40 Gene and its Serum Levels in Neuromyelitis Optica Patients

- Advances in Molecular biomarker for early diagnosis of Osteoarthritis

- Identification of BRCA1/2 p.Ser1613Gly, p.Pro871Leu, p.Lys1183Arg, p.Glu1038Gly, p.Ser1140Gly, p.Ala2466Val, p.His2440Arg variants in women under 45 years old with breast nodules suspected of having breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- Endometriosis Pathoetiology and Pathophysiology: Roles of Vitamin A, Estrogen, Immunity, Adipocytes, Gut Microbiome and Melatonergic Pathway on Mitochondria Regulation

- Integral membrane protein expression of human CD25 on the cell surface of HEK293 cell line: the available cellular model of CD25 positive to facilitate in vitro developing assays

- Review Article

- Role of Nanomedicine in Redox Mediated Healing at Molecular Level

- Research Article

- Glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) and T1 (GSTT1) variants and breast cancer risk in Burkina Faso

- Incidence of viruses infecting pepper in Thailand

- Mechanochemistry of von Willebrand factor

- Schizophrenia phenomenology comprises a bifactorial general severity and a single-group factor, which are differently associated with neurotoxic immune and immune-regulatory pathways

- Role of Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) genes in stages of HIV-1 infection among patients from Burkina Faso

- The effect of rs9930506 FTO gene polymorphism on obesity risk: a meta-analysis

- Special Issue: Recent Advances in Basic and Clinical Medicine

- Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic activities of Nannochloropsis oculata microalgae in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

- Comparison of the effect of vitamin D on osteoporosis and osteoporotic patients with healthy individuals referred to the Bone Density Measurement Center

- Zinc enhances the expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference through dopaminergic and serotonergic systems

- Pre-operative laparoscopic staging of gastric cancer in patients who are candidates for neo-adjuvant chemotherapy: A Cross Sectional Study

- Neurotoxic Effects of Stanozolol on Male Rats‘ Hippocampi: Does Stanozolol cause apoptosis?

- Only serum pepsinogen I and pepsinogen I/II ratio are specific and sensitive biomarkers for screening of gastric cancer

- Evaluation of Quality of Life in Terms of Sinonasal Symptoms in Children with Cystic Fibrosis

- The Effect of Fine needle aspiration on Detecting Malignancy in Thyroid Nodule

- Diagnosis of Primary Hydatid Cyst of Thyroid Gland: A Case Report

- Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of lung adhesion before surgery

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- ATP Synthase: Structure, Function and Inhibition

- Insulin Promotes Wound Healing by Inactivating NFkβP50/P65 and Activating Protein and Lipid Biosynthesis and alternating Pro/Anti-inflammatory Cytokines Dynamics

- Mini review

- The disordered boundary of the cell: emerging properties of membrane-bound intrinsically disordered proteins

- Research Article

- Expression of OX40 Gene and its Serum Levels in Neuromyelitis Optica Patients

- Advances in Molecular biomarker for early diagnosis of Osteoarthritis

- Identification of BRCA1/2 p.Ser1613Gly, p.Pro871Leu, p.Lys1183Arg, p.Glu1038Gly, p.Ser1140Gly, p.Ala2466Val, p.His2440Arg variants in women under 45 years old with breast nodules suspected of having breast cancer in Burkina Faso

- Endometriosis Pathoetiology and Pathophysiology: Roles of Vitamin A, Estrogen, Immunity, Adipocytes, Gut Microbiome and Melatonergic Pathway on Mitochondria Regulation

- Integral membrane protein expression of human CD25 on the cell surface of HEK293 cell line: the available cellular model of CD25 positive to facilitate in vitro developing assays

- Review Article

- Role of Nanomedicine in Redox Mediated Healing at Molecular Level

- Research Article

- Glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) and T1 (GSTT1) variants and breast cancer risk in Burkina Faso

- Incidence of viruses infecting pepper in Thailand

- Mechanochemistry of von Willebrand factor

- Schizophrenia phenomenology comprises a bifactorial general severity and a single-group factor, which are differently associated with neurotoxic immune and immune-regulatory pathways

- Role of Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) genes in stages of HIV-1 infection among patients from Burkina Faso

- The effect of rs9930506 FTO gene polymorphism on obesity risk: a meta-analysis

- Special Issue: Recent Advances in Basic and Clinical Medicine

- Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic activities of Nannochloropsis oculata microalgae in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

- Comparison of the effect of vitamin D on osteoporosis and osteoporotic patients with healthy individuals referred to the Bone Density Measurement Center

- Zinc enhances the expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference through dopaminergic and serotonergic systems

- Pre-operative laparoscopic staging of gastric cancer in patients who are candidates for neo-adjuvant chemotherapy: A Cross Sectional Study

- Neurotoxic Effects of Stanozolol on Male Rats‘ Hippocampi: Does Stanozolol cause apoptosis?

- Only serum pepsinogen I and pepsinogen I/II ratio are specific and sensitive biomarkers for screening of gastric cancer

- Evaluation of Quality of Life in Terms of Sinonasal Symptoms in Children with Cystic Fibrosis

- The Effect of Fine needle aspiration on Detecting Malignancy in Thyroid Nodule

- Diagnosis of Primary Hydatid Cyst of Thyroid Gland: A Case Report

- Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of lung adhesion before surgery