Abstract

Infrastructure for facilitating access to and reuse of research publications and data is well established nowadays. However, such is not the case for software. In spite of documentation and reusability of software being recognised as good scientific practice, and a growing demand for them, the infrastructure and services necessary for software are still in their infancy. This paper explores how quality assessment may be utilised for evaluating the infrastructure for software, and to ascertain the effort required to archive software and make it available for future use. The paper focuses specifically on digital humanities and related ESFRI projects.

Zusammenfassung

Für wissenschaftliche Publikationen und zunehmend auch für Forschungsdaten sind Dienste und Verfahren zur Sicherstellung des nachhaltigen Zugangs und der Nachnutzung bereits relativ etabliert. Anders sieht die Situation für digitale Forschungsinfrastrukturen, insbesondere für Softwarekomponenten und elektronische Werkzeuge aus. Hier steht einer wachsenden Nachfrage nach Dokumentation und Zugänglichkeit von wissenschaftlicher Seite sowie der generellen Anforderung nach Zugänglichkeit und Nachvollziehbarkeit im Sinne guter wissenschaftlicher Praxis bisher kein entsprechendes infrastrukturelles Angebot gegenüber. Beziehungsweise oftmals befinden sich Dienste in einem nicht dokumentierten Zustand, der eine Nachnutzung und Weiterentwicklung durch Dritte erschwert oder sogar unmöglich macht.

Bezogen auf die Digital Humanities diskutiert der vorliegende Aufsatz das Konzept des Quality Assessments (Qualitätsbeurteilung) als Instrument zur Evaluierung nachnutzbarer Softwarekomponenten.

1 Introduction

Digital transformation has considerably changed the way research data and electronic research publications are handled. This development is still unfolding and the related tasks create challenges not only for researchers but also for the providers of digital research infrastructure. In particular, a sustained provision of digital research data and publications with regard to reuse, persistent traceability, and the further development of use cases are the key challenges for infrastructure providers in the humanities and cultural sciences and all other disciplines as well.

Against this background, we see a growing importance of development tasks and processes necessary for the creation of digital research infrastructures and digital tools. Infrastructures and tools to be applied for the analysis of research data and publications pose challenges with regard to sustainable operation because they have to be planned, optimised and implemented. These new challenges concern not only individual developers but also infrastructure operators (e. g. data centres) and data providers (e. g. libraries) and are increasingly important in the implementation of software projects in research.[2] In particular, infrastructure operators and data providers not only have to provide access to services and data but they have to have knowledge about how the services and data are used by researchers, their areas of research, and how these might evolve over time.[3] There are already numerous analyses available on implementation and solution scenarios. For example, research data centres, publication repositories, digital journals or value-added services for individual infrastructure components, such as persistent identifiers or citation evaluation, serve scientists by letting them permanently access data and services and use them according to their specific research requirements. All of the abovementioned examples have in common that they are concerned more or less with results or at least intermediate results of research processes.

However, a further set of issues connected to the digital transformation in research has only recently come into the focus of infrastructure and service providers: researchers have started demanding sustained provision (or at least the provision for a clearly designated period of time) of digital tools and working environments. Concurrently, they also want to be informed about how these tools have been developed and their underlying algorithms to establish their provenance. Science is based on the twin concepts of validation and reproducibility, so scientists must know how their digital tools works and how the results have been achieved.

In addition to the obvious argument of the desired reuse of tools and procedures – an argument aimed at generating new research questions and results – the aspect of the traceability and transparency of research should also be mentioned here. With increasing entanglement of research data with research tools, the availability and accessibility of tools becomes more and more important for the traceability of research. Only with information about the initially used tools and procedures research results can be reproduced, a central requirement for good scientific practice.

However, in contrast to research results with a static character, the generally dynamic nature of research tools, such as software components, makes it more difficult to provide them sustainably. Tools and working environments that have been developed under specific technical requirements bear the risk of rapidly becoming outdated. Another complicating factor refers to the reputation associated with the development and operation of software components or research environments. The scientific reputation gained for tools is relatively lower than for research publications. The effort and time horizon for the development and provision of a research tool is generally different from the time horizon to process an individual research question. This makes it more difficult to determine the long-term availability of tools and services beyond individual research projects. This aspect can still be considered in a different dimension, which relates to the nature of the provision (cost/effort) and the use (benefit/yield). Since digital research infrastructures are principally accessible on a global scale – which is desirable from a scientific point of view – the relationship between providers, developers, and users is becoming more diffuse or needs a different regulation than local relations and resource commitments, e. g. on a research campus. Finally the agent aspect is to be mentioned. As a matter of fact, most research tools and infrastructures are developed and deployed by actors other than the end users for a variety of reasons. Usually two main groups can be distinguished in this regard: researchers and infrastructure operators, even if there are in practice, increasing overlaps between both groups.

Challenges in providing digital research infrastructures as outlined above are best dealt within an institutionalised, scientific, and long-term framework. Since 2002, the ESFRI (European Strategy Forum on Research)[4] exists as an institutional framework for the funding of infrastructure projects within the European Research Landscape. An advantage of ESFRI reaching beyond the funding itself is the fact that all subsidised projects correspond to a higher level funding policy strategy, thus enabling comparability, quality assurance, interoperability and cooperation.[5]

The question remains what a sustainable operation of research infrastructure and in particular software components (tools and services) means and how it can be implemented in practice. This much is certain: to meet future technical and functional requirements, we have to conduct maintenance, modernisation and adaptation (e. g. in form of updates, migration) on a permanent basis with the aim of preserving information quality and a range of functions.

Already the design and development of a software component has great impact on its long-term quality. In this sense, a significant part of the answer to the question of the sustainable provision of software components will be based upon quality assessment, and that means a careful evaluation and documentation of components taking into account different application scenarios. In our context, quality assessment means the evaluation of research infrastructures according to selected, comparable criteria. Research infrastructures can be digital working environments, software components or collections of research data. The term is thus taken relatively broadly here since the relevant aspect and common feature is the operation of such components in the sense of hosting – the perspective of the infrastructure operator. Conversely, the assessment of a given software tool or infrastructure is more important for those tools for which the operators of the infrastructure (e. g. archives, libraries and data centres) will or might have to take over maintenance responsibility in the future. This is often the case for tools developed by individual researchers during projects with finite lifetime and limited funding periods.

The challenges arising in operating and hosting a research infrastructure are quantified by means of quality assessment allowing us to compare different infrastructure components and make a decision about hosting. The meaning of quality assessment in the context of digital research infrastructures and how it can be operationalised will be discussed below.

In the following remarks the Humanities at Scale project (HaS)[6] is presented as an example of the implementation efforts regarding quality assessment and sustainable provision of digital research infrastructures in the humanities. HaS as a support activity of DARIAH-EU aims to improve the outreach and impact of DARIAH-EU as a humanities research infrastructure at various levels. The embedding of HaS in the DARIAH-EU context and the main tasks of the project are described in the following chapter.

2 Humanities at Scale as DARIAH-EU implementation context for quality assessment

The Digital Humanities (DH) as an expansive field of research generate an increasing amount of innovative tools and methods to enhance research. As contribution to a sustainable digital European infrastructure for long-term availability of digital research data and tools, the DARIAH-EU[7] infrastructure (Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities) has been founded to develop a strong cooperation and information exchange between research communities and institutions in the Arts and Humanities. Its ambition to extend the research community and to create a pan-European network of expertise was the motivation to initiate the Horizon 2020 project Humanities at Scale. DARIAH-EU has achieved the status of a European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC) and consists currently of 17 partner countries. DARIAH-EU and the national DARIAH initiatives, like DARIAH-DE in Germany,[8] branch out in activities reaching from participation in DH research projects over teaching and training activities to dissemination and communication measures.[9]

Against this background HaS intends to scale up – as the name indicates – already existing activities, infrastructures and research relations in the European Research Area (ERA) and is to be seen as an embedded and integral component of DARIAH-EU. The project is coordinated by the DARIAH ERIC and aims to evolve the DARIAH community of the Arts and Humanities, offer training and information material, set up a number of training workshops and develop core services within a sustainable and usable framework. Within this framework a range of research infrastructure components is established that will connect DH research tools, services and research data. A main challenge is to construct the technical infrastructure sustaining these functions. These technical systems consist of basic services such as cloud services, computing capacity or communication facilities e. g. wiki platforms or ether pads[10] – but also reach beyond this level and integrate more research specific services and tools – such as integrated authority files, like the GND,[11] or a geo browser such as the DARIAH GeoBrowser[12] for using and ingesting specialised research data.

To extend the number of members associated with DARIAH, HaS will integrate new regional and discipline-specific user communities. The project supports the growth of the community with ambassadors for Digital Humanities and alternative funding models as well as a dedicated pan-European training programme. Summer and winter schools in regions without a longstanding tradition in the Digital Humanities aim to enlarge the community which benefits from the direct exchange of researchers in the European Research Area. In addition, several fellowships will provide access to expertise and data collections in DH centres for outstanding researchers. This community, as a network of expertise, created and continues to create a number of important research tools and services. HaS is building a sustainable infrastructure to make these tools and services accessible and open for the Digital Humanities.

In the following section, the authors focus on the general topic of quality assessment of software development. While the software components are generally made public at the end of the funding period, e. g. via GitHub, this does not mean that they can be reused or integrated in other developments. Documentation is often insufficient, code is inadequately described, outdated programming languages may be used, user interfaces and their web implementations are not well documented, and the used data and metadata formats are also not described. These circumstances are a major obstacle for the reuse of tools and services (not only) in the Digital Humanities. A quality initiative with the aim of establishing a quality assessment for developments to gain better level software sustainability[13] is urgently required. How this could be realised and which criteria are needed is discussed on the following pages.

3 Sustainability of research infrastructure based on quality assessment

Software sustainability can be defined in a lot of different ways. People in a commercial context tend to the general definition of sustainability as “the capacity to endure”[14][15] and “preserve the function of a system over an extended period of time”.[16] Hence software sustainability is an umbrella term without a standard definition, for instance, by the International Organization for Standardization[17] (ISO). However, this topic poses an important challenge for software products that cover technical, cultural and political issues.[18][19] In particular, this is a principle that exists independently of the development environment as well as of the possibilities of use. Sustainable tools and support of software components concern commercial suppliers as well as development scenarios in science and research. The question we address here is, “What does software sustainability mean and how can it be measured?” While most efforts under the label of sustainability have focused so far on energy efficiency, we see a broader concept, including various aspects of sustainability including properties that cannot be quantified easily.[20][21] This chapter highlights the technical perspective on sustainability and will describe ways to measure the sustainability level of a software product. How these complexes are currently being implemented in industrial and business environments will be discussed and analysed below.

The ISO 24764 standard[22] definition[23] for software implies that tools and services can be understood as a software product. The well-known lifecycle in software engineering[24] covers the whole process of developing a software product starting with the analysis of requirements. Let us suppose that the product will fulfil the defined requirements and will satisfy the current needs of the intended target group, but will it also meet future requirements? How long will tools or services run without adaption, changes or replication? These and similar questions were part of a workshop organised by the Software Sustainability Institute[25] and have been addressed in its report[26] reflecting up-to-date discussions about software sustainability in research infrastructure. This report covers important recommendations. “Incentives must be determined to persuade stakeholders to invest resources into software sustainability [...].”[27] From a commercial point of view financial investments can be reduced (to a certain extent) through sustainability, despite the fact that ample resources are needed. This is especially important for proprietary products, as components can be used sustainably and development tasks can be carried out independently. An exchange of knowledge, which can lead to distributed development over a long period of time, is therefore very important. However this contrasts with temporary research projects that are only supported for a limited period of time. Thus, in research, the focus is on obtaining research results rather than on permanent operation of infrastructures.[28][29][30]

But why is software sustainability so important? A main goal of developing research tools and services is to improve research infrastructures. As funding for research is generally limited, adaptation and replication of tools and services are rare. Therefore software sustainability gains importance because it creates reliable, reproducible and reusable software. This leads to:

Trusted research: Reliability and reproducibility are key indicators for software products that generate trustful results.

Increased rate of discovery: Researcher can use adaptable and extendable software products as a base to develop new products. This would leave more time for research and would avoid replicating software products that already exist.

Increased return on investment: Reusing software products rather than replicating them has the potential to save a significant amount of resources. This amount could be reinvested into research.

Research data remains readable and usable: Sustainable software products allow continued access and use of research data. This aids reproducibility and extracts the greatest return from the investment made into collecting data.[31]

All in all, software sustainability is a key challenge for developing tools and services.[32][33] As there is no common standard measurement for it, the question remains how sustainability can be measured. A key aspect of sustainability is to identify good software.[34] An example: Adopting software requires a significant investment of resources with no guarantee for the achieved outcome to a defined amount of invested resources. “Researchers’ resources are limited, so they can be reluctant to adopt software simply because it is too risky. This risk would be considerably reduced if there was a way of identifying good software. This would improve adoption and reuse of software – which are both goals of sustainability.”[35] To measure the quality of a software product is a considerable part of quality assessment.

It is not trivial to define the quality of a software product, even more difficult to assess its quality. This paragraph covers explanations up to definitions to establish an understanding of quality assessment. Generally speaking, quality assessment is based on quantitative and qualitative characteristic measurements. This allows comparability between software products. In other words, “the quality of a software product is the degree to which it satisfies the stated and implied needs of its various stakeholders, and thus provides values.”[36]

Measuring the sustainability of software relies to a large amount on qualitative measures. Not all characteristics are quantifiable. However, qualitative measures are problematic, because they bear the risk that personal opinions affect the results. Nevertheless, there is a need for a model that classifies the quality of the software. One often referenced model is the ISO 25023 standard,[37] called system and software quality requirements and evaluation – Measurement of system and software product quality (SQuaRE). SQuaRE defines characteristics that categorise the software product to enable a measurement of software quality. These characteristics can be a basis to assess the quality and furthermore the sustainability of a tool or service. The goal of these characteristics, called properties, is to quantify the product quality by applying a measurement method. ISO itself say that these “quality characteristics will be of varying importance and priority to different stakeholders.”[38]

All nine main characteristics of this ISO standard are listed below and described briefly in the ISO standard:[39]

Functional suitability measures: This main characteristic assesses the degree to which the functionality covers all specifications. Software products functionality meet stated and implied needs under specific conditions.

Compatibility measures: The main goal of this measurement is to assess a software products’ possible information exchange with other products. Interoperability and exchangeability are key indicators.

Usability measures: Usability measures describe the degree to which a software product can be used by defined users to achieve defined goals. Properties, such as effectiveness and satisfaction, are described in a specified context of use.

Reliability measures: Characteristics in this chapter assess the software products’ performed functions. Specified functions under specific conditions for a specified time meet implemented functionality.

Security measures: This main characteristic describes how the software product protects information to unauthorised persons and components.

Maintainability measures: Maintainability measures describe the effectiveness and efficiency of maintaining a software product by intended groups. Modularity and reusability are key indicators.

Portability measures: These measures assess the degree of effectiveness and efficiency with a software product can be transferred from one environment to another. Adaptability and replicability play a crucial role.

All these characteristics may have sub-characteristics and each characteristic is quantified by a measurement function. An example:

The transaction processing capacity is a sub-characteristic of performance efficiencies measures and calculates how many transactions can be processed per unit time. The related measurement function of this example is trivial in contrast to other measurement functions: X = A/B (A = number of transactions completed during observation time, B = duration of observations).[40]

As a result, these models provide the quality of a software product in form of quantified properties. Therefore the quality of a tool or service becomes comparable and thus the sustainability of the tool can be described.

Software sustainability has a few additional important aspects. The users of a tool or service have different perspectives on sustainability than other stakeholders, especially developers and operators. At least, other characteristics are important to them.

For users, transparency is very important. Transparency includes open standards (e. g. for data formats), documentation (how to use this tool/service), further development, and very important: troubleshooting. Troubleshooting could be realised in form of a (technical) support, as a helpdesk or a very simple, but not less better one, solution: Public issue tracking (e. g. GitHub issues). These characteristics improve the acceptance of a tool/service and lead to higher sustainability. Thus, from a user perspective, quality assessment is a significant contribution to the efficient design of research tools and services and can help conserve valuable resources so they may be devoted to the actual research.

Research stakeholders[41] are certainly pursuing all these goals, but are interested in modularity, platform independencies and a decentralised architecture.[42] Entities and data sources should be operated in a decentralised way. This reduces dependencies and leads to higher sustainability. Additionally, highly consistent data quality and a minimum time effort for the compilation and preparation of data are important examples of sustainability characteristics. A topic that is becoming more and more important is economic operation and development. This includes conscious handling of resources, energy and resource efficiency.[43]

In the context of research, there is one important advantage for users and stakeholders: Knowledge sharing. OSI[44] licensed software products enable sharing of knowledge and thereby significantly contribute to software sustainability.

4 Quality Assessment of research infrastructures in practice

The problem of software sustainability has been identified by various research infrastructures such as CESSDA (Consortium of European Social Science Data Archives),[45] CLARIN (European Research Infrastructure for Language Resources and Technology),[46] and DARIAH (Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities).[47] The Dutch initiative CLARIAH-NL, a joint effort by CLARIN and DARIAH in the Netherlands, has started work on defining and establishing software quality guidelines which are published on GitHub[48] and open for expansion and contribution. The CESSDA infrastructure is currently working on defining a software maturity model, based on the Reuse Readiness Levels developed by NASA Earth Science Data Systems.[49] In DARIAH the discussions gained traction with the beginning of the H2020 funded project Humanities at Scale (HaS) in 2015 and will be pursued throughout the project as well as by the upcoming H2020 funded project DARIAH ERIC Sustainability Refined (DESIR) starting in early 2017.

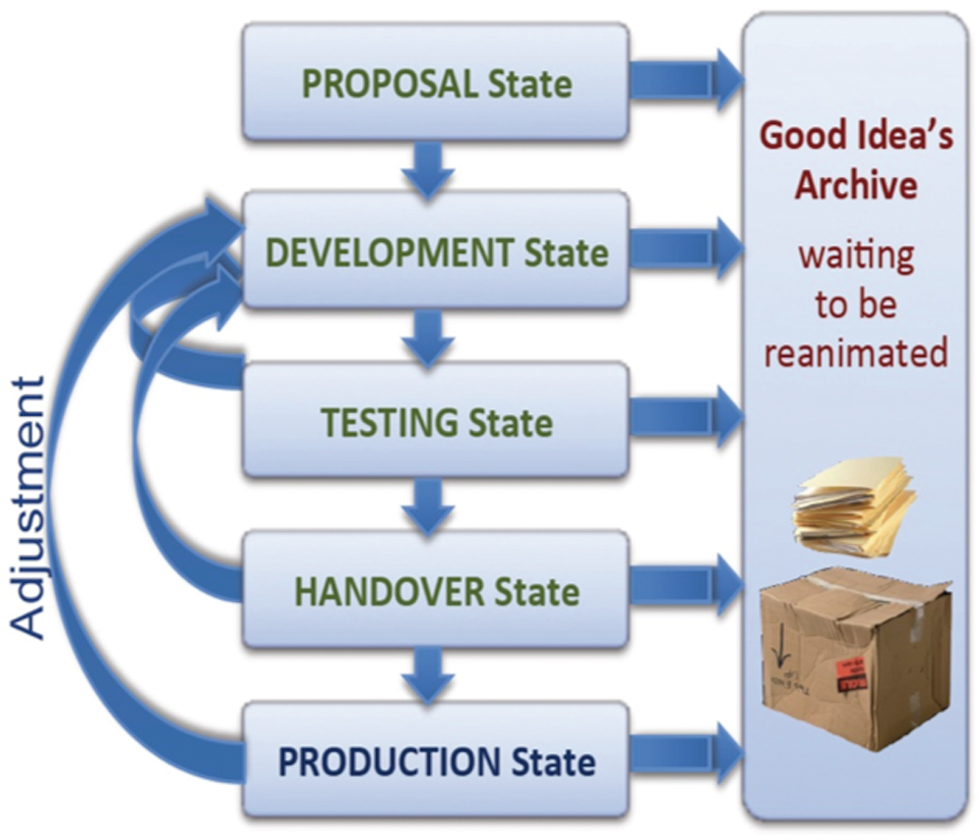

Within DARIAH, the work has been focussing on understanding the development process of software tools and services, as defined in the DARIAH-DE Service Life Cycle[50] (SLC). The SLC describes the different stages of software development from early inception through development and testing until it reaches a stable production state. In a similar manner, CLARIAH-NL differentiates between software that is experimental in nature versus user-ready and between supported and unsupported tools on the other hand.

DARIAH-DE Service Life Cycle States[51]

Some of the key problems identified are the high staff turnover within research groups and initiatives combined with a focus on working tools and services over documentation and standard compliance. While this approach, encouraged by e. g. the Agile manifesto,[52] enables swift development and produces viable products which in turn attract users, it sets a focus on business oriented goals. The focus on user and customer acquisition however cannot be the primary focus of research infrastructures, which must include sustainability and maintainability among their core objectives.

To align work with these objectives, the works cited above emphasise a range of clear instructions and foundations ranging from explicit instructions on documentation to code conventions and general best practices.

When addressing sustainability of software components, the underlying infrastructure itself can easily be overlooked. Recent changes in software industry standards, as outlined in the DevOps Handbook[53] have shifted towards including the infrastructure itself as part of the ongoing development efforts. Through the wide adoption of configurations management such as Puppet,[54] Chef[55] and Ansible[56] and containerised packaging formats such as Docker,[57] classical IT operations have shifted closer to development while conversely sharing responsibilities with them. This approach to intensify communication and collaboration of development and operations, named DevOps, employs a number of automation measures and techniques for example infrastructure as code. The latter refers to an approach where the state of the infrastructure is defined through software code that can be used and edited following established software development standards including revision control, code review and (automated) testing. Together with the software code, this entirely defines the state of the system processing and transforming the research data, thus providing a provenance model for the application.

Following this approach, infrastructure maintenance can be addressed the same way as software maintenance. Thus, the problem to be addressed is how to reduce and approach technical debt[58] present in academic and research software and infrastructures.

5 Quality assessment and the determination of archiving software components

A frequently cited paradigm of the Blue Ribbon Task Force[59] states: “When making the case for preservation, make the case for use”,[60] indicating that the technical or formal assessment of research data – and in our context of research software components – is only one part of the answer to the question of sustainability and archival value. Another part of the answer resides in the assessment of the "market opportunities" of the software components or research data in 5, 10 or 15 years: Which research software components and research data have the prospect of future reuse and how shall the research data centre or infrastructure operator decide on the efforts of sustaining? Here, the crux lies in the difficult task of estimating the usage potential in order to justify the cost of sustaining and curating the research data. The instruments used by companies reaching from market research and applying of business experience can, with certain adaptations, also open up a path for research infrastructure, which is described in more detail in the following.

While in the previous chapters a software development-oriented view of quality assessment was presented, the methodology and considerations below come out of a research point of view. In this perspective, quality assessment is not viewed primarily from an infrastructure provider’s perspective, thinking mainly in terms of costs, but from a scientific or use perspective. Whereas the infrastructure provider attempts to make reliable predictions about the deployment and maintenance effort of components, the second approach attempts to assess their usefulness and future use. Obviously, in the case of technical assessment, the identification and measurement of most criteria are straightforward because they rely on quantifiable criteria. In contrast, the assessment of scientific “usefulness” is much more difficult, since it is more qualitative or hard to define on a comparable basis.

The cost of hosting a software component can be judged in a relatively comparable way for an infrastructure provider, since the provider can deduct from its experience with established technologies and standards in terms of quantitatively defined development and maintenance expenditure. This may be as simple as forecasting maintenance expenditure in the form of working hours and licensing costs resulting in a cost calculation. For instance the intended state of the software components can be defined as full accessibility and usability for the intended purposes in 5, 10 or 15 years.

In contrast the assessment of the sustainable provision from a scientific perspective is different. The technical questions discussed above are not of interest but whether the software component will still correspond to the methodical state-of-the-art and whether it will be used and be useful in 5, 10 or 15 years from a research point of view. Unless we talk about basic services and tools, the question is very difficult to answer. It is beyond question that basic services such as cloud storage, collaborative editing of files or database architecture standards will play a role in future research processes and will also be at least capable to be migrated among service providers or hosting institutions. In the case of services and tools developed in the context of specific research questions, the assessment of any future use is difficult or quite impossible.

It seems obvious to approach the assessment of research infrastructures or research projects in a quantitative way by applying a catalogue of comparable criteria. The use of such instruments for research evaluation or to determine the distribution of third-party funding is widespread. Within the framework of the European Commission’s FP7 funding programme, ERINA+[61] (Socio-Economic Impact Assessment for e-Infrastructures Research Projects) developed a catalogue and evaluation tools from 2010 to 2013 to measure the “success” of promoted infrastructure projects.

In contrast to ERINA+ the project “Success Criteria for Virtual Research Environments”[62] funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) in 2013/2014 concentrated on a narrowly defined group of research infrastructures, the virtual research environments (VRE) and gave more weight to the qualitative assessment of usefulness or success. Both projects came to the unsurprising insight that a purely quantitative and comparative assessment of research infrastructures is a difficult undertaking. Additionally, the thesis was confirmed that the assessment of the user community must be given the greatest possible significance in order to approach an assessment of “scientific usefulness”.

Facilitating comparability is of great importance in this process. If it were possible to gather the benefits and user satisfaction of tools and methods along coherent categories, thus enabling comparability ex ante, it would be at least a basis for deciding whether tools could be considered for a sustainable deployment. Tools and methods whose assessment fall below a defined threshold, for example which are perceived as uncomfortable in use or which cannot solve certain tasks satisfactorily, could be left aside from the outset. Entirely subjective and therefore case-specific assessments on the usefulness of certain tools do not help. Instead, categorisation and consistency of criteria are important.

As has been made clear, purely technical assessment as in the above sections would also not help substantially in this context. A technical assessment would evaluate a scientifically “successful” tool as well as an “unsuccessful” tool on the same scales and in this way also take over tools that are no longer used or hardly used at all but are on a technical level easily to maintain.

An advantage of a user-based assessment in addition to the affinity to the research community would be an ongoing evaluation. For instance, a freely accessible web platform with a consistent use would grow over time and develop according to the principle of user-generated content. Of course, this is certainly not possible without substantial editorial support from the infrastructure operators. Looking at the users’ motivation to generate such content, a similar question arises as with the scientific reputation of infrastructure mentioned earlier. The user-based assessment of infrastructure components, tools and services has to generate incentives for researchers to share their experiences and evaluations. Within HaS this nexus is subject to discussion. This also reflects the philosophy of the “architecture of participation”[63] within DARIAH-EU, expressing the involvement of researchers in the design of research infrastructures. An obvious option would be to enhance the user-generated content in such a way that it qualifies as publication, maybe similar to a book review, which is already an established practice in most disciplines. But the concluded character of such a user review stands in conflict with the above mentioned desired dynamic state of the content. The infrastructure therefore has to solve this problem in order to be able to offer updatable reviews. As a conclusion: not just researchers but also infrastructure operators would benefit from a review platform for scientific tools and methods.

6 Conclusion

In summary, what role can quality assessment play in the sustainable provision of digital research infrastructures? As has been described, there are many ongoing initiatives in the commercial sector as well as in research, which are increasingly addressing this issue, and relevant ISO standards exist as well. In addition to quality aspects in the original development process, the usability of developed software components plays an important role. Especially in the case of DH projects, software components are not only important as the tools and procedures to achieve research results, but they themselves qualify as research results, whether it is possible to visualise and represent subjects of the humanities and cultural sciences, or whether the traceability of the results of the analysis and their validity must be verifiable. We are at a point that is comparable to the digitisation efforts at the beginning of the 21st century. After years of exploration, the DFG has developed practice recommendations[64] that are used both as support and as a guideline for digitisation projects. This has ensured that quality standards are introduced in the area of digitisation, with the aim of enabling re-usability, interoperability, synergy and efficiency. Now it is time to promote similar processes for research software development and components.

This is a central task, which can be tackled, in particular, by ESFRI projects within the European Research Landscape. Software developments must be internationally usable and reusable, and at the same time open to further developments. In this way, the ESFRI projects contribute to the sustainable operation and long-term use of software as transmission means. For this, however, it is necessary that recommendations and criteria for quality assessment are prepared, published and established as requirements and accepted by the researchers. A particularly important and inhibiting factor in this context is that software development is usually only understood as a means and purpose to achieve research results.

Resources for software development may be applicable with research funders, but it is not possible to exactly estimate which resources are necessary to achieve a sufficient level of quality assessment. Here, the European ESFRI projects can articulate sustainable criteria and requirements in order to provide national sponsors and the communities with the appropriate instruments. Sustainability and reusability can be generated in this way, but at the same time require the necessary additional resources. Compared to electronic publications and their persistent storage, the effort and expenditure for the sustainable provision of software components and digital research data is higher. Which resources are needed will certainly not be answered by the mere generation of criteria catalogues and requirements. Rather, best-practice projects are necessary to combine the existing efforts by CESSDA and CLARIN and the syntheses started in DARIAH within the scope of HaS to eventually be adopted and implemented within the wider research community and across all disciplines and infrastructures. It is apparent that concrete future efforts will be necessary to implement quality assessment requirements for research infrastructure projects and software components used in digital humanities projects.

In addition, ensuring sustainability of research tools and data is not just a technical question. It also depends on the fact that the work necessary to provide software in a sustainable manner will be recognised as scientific achievement and credited accordingly in the future. In addition to scientific publications and lectures, documentation and work for quality assessment must be recognised as a scholarly/scientific benefit. These are tasks which can only be jointly implemented by scientists, developers, librarians, and computer scientists.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Claudia Engelhardt and Puneet Kishor for substantial support in the process of finalising the article.

References

Blanke, Tobias; Fritze, Christiane (2012): DARIAH-EU als europäische Forschungsinfrastruktur. In: Neuroth, Heike; Lossau, Norbert; Rapp, Andrea: Evolution der Informationsinfrastruktur – Kooperation zwischen Bibliothek und Wissenschaft. Available at http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl/?webdoc-39006.Suche in Google Scholar

Blue Ribbon Task Force (2010): Blue Ribbon Task Force on Sustainable Digital Preservation and Access: Sustainable Economics for a Digital Planet: Ensuring Long-Term Access to Digital Information. Available at http://brtf.sdsc.edu/biblio/BRTF_Final_Report.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Blümm, Mirjam; Neuroth, Heike; Schmunk, Stefan (2016): DARIAH-DE – Architecture of Participation. In: BIBLIOTHEK – Forschung und Praxis, 40 (2), 165–71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/bfp-2016-0026.10.1515/bfp-2016-0026Suche in Google Scholar

Blümm, Mirjam; Schmunk, Stefan (2016): Digital Research Infrastructures: DARIAH. In: 3D Research Challenges in Cultural Heritage II – How to Manage Data and Knowledge Related to Interpretative Digital 3D Reconstructions of Cultural Heritage, ed. by Sander Münster, Mieke Pfarr-Harfst, Piotr Kuroczynski and Marinos Ioannides, 62–76. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47647-6.10.1007/978-3-319-47647-6_4Suche in Google Scholar

Brundtland, Gro-Harlem (1987): Our Common Future (Brundtland Report). United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. Available at http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Buddenbohm, Stefan; Enke, Harry; Hofmann, Mathias; Klar, Jochen; Neuroth, Heike; Schwiegelshohn, Uwe (2015): Success Criteria for the Development and Sustainable Operation of Virtual Research Environments. In: D-Lib Magazine, 21 (9/10). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1045/september2015-buddenbohm.10.1045/september2015-buddenbohmSuche in Google Scholar

DFG (Hrsg.) (2016): DFG-Praxisempfehlung “Digitalisierung”. Stand 12/2016. Available at http://www.dfg.de/formulare/12_151/12_151_de.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Doorn, Peter; Aerts, Patrick; Lusher, Scott (2016): Research Software at the Heart of Discovery, DANS & NLeSC. Available at https://www.esciencecenter.nl/pdf/Software_Sustainability_DANS_NLeSC_2016.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Gietz, Peter; Hütter, Heiko (2016): Der Aufbau einer nachhaltigen technischen Infrastruktur für die Geisteswissenschaften: Die DARIAH-DE eHumanities Infrastructure Service Unit (DeISU). In: BIBLIOTHEK – Forschung und Praxis, 40 (2), 244–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/bfp-2016-0029.10.1515/bfp-2016-0029Suche in Google Scholar

Hettrick, Simon (2016): The Software Sustainability Institute: Research Software Sustainability – Report on a Knowledge Exchange Workshop. Available at http://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6332/1/Research_Software_Sustainability_Report_on_KE_Workshop_Feb_2016_FINAL.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Hilty, Lorenz; Arnfalk, Peter; Erdmann, Lorenz; Goodman, James; Lehmann, Martin; Wäger, Patrick (2006): The Relevance of Information and Communication Technologies for Environmental Sustainability: A Prospective Simulation Study. In: Environmental Modelling & Software, 21 (11), 1618–29, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2006.05.007.10.1016/j.envsoft.2006.05.007Suche in Google Scholar

ISO/IEC 24764:2010-04 (2010): Information Technology – Generic Cabling Systems for Data Centres. International Organization for Standardization. Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=43520.Suche in Google Scholar

ISO/IEC 25012:2008-12 (2008): Software Engineering – Software Product Quality Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE) – Data Quality Model. International Organization for Standardization. Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=35736. Suche in Google Scholar

ISO/IEC 25023:2016-06 (2016): Systems and Software Engineering – Systems and Software Quality Requirements and Evaluation (SQuaRE) – Measurement of System and Software Product Quality. International Organization for Standardization. Available at http://www.iso.org/iso/home/store/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=35747.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim, Gene; Humble, Jez; Debois, Patrick; Willis, John (2016): The DevOps Handbook: How To Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, & Security in Technology Organizations. IT Revolution Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Kocak, Sedef Akınlı; Alptekin, Gülfem Işıklar; Bener, Ayşe Başar (2014): Evaluation of Software Product Quality Attributes and Environmental Attributes Using ANP Decision Framework. In: Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Requirement Engineering for Sustainability.Suche in Google Scholar

Lago, Patricia; Gu, Qing; Bozzelli, Paolo (2013): A Systematic Literature Review of Green Software Metrics. Technical Report. Available at http://www.sis.uta.fi/~pt/TIEA5_Thesis_Course/Session_10_2013_02_18/SLR_GreenMetrics.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Lago, Patricia; Koçak, Sedef; Crnkovic, Ivica; Penzenstadler, Birgit (2015): Framing Sustainability as a Property of Software Quality. In: Communications of the ACM, 58 (10), 70–78.10.1145/2714560Suche in Google Scholar

Mittler, Elmar (2012): Die Zeit war reif. In: Neuroth, Heike; Lossau, Norbert; Rapp, Andrea: Evolution der Informationsinfrastruktur – Kooperation zwischen Bibliothek und Wissenschaft. DOI: http://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl/?webdoc-39006. Suche in Google Scholar

Razavian, Maryam; Procaccianti, Guiseppe; Tamburri, Damian Andrew (2014): Four-dimensional sustainable e-services. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Informatics for Environmental Protection, Oldenburg, Germany, Sept. 10–12, 221–28.Suche in Google Scholar

Taylor, James (2004): Managing Information Technology Projects – Applying Project Management Strategies to Software, Hardware and Integration Initiatives. Suche in Google Scholar

Zakaria, Zuria Haryani; Hamdan, Abdul Razak; Yahaya, Jamaiah; Deraman, Aziz (2016): Sustainability and Quality – Icing on the Cake. In: Lecture Notes on Software Engineering, 4 (3).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titelseiten

- Inhaltsfahne

- Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

- Das frauen- und geschlechterspezifische Gedächtnis einer Universalbibliothek

- AKON – Ansichtskarten Online

- Die Katalogisierung der Bücher der ehemaligen Fideikommissbibliothek des Hauses Habsburg-Lothringen an der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek

- Maria Theresia sagt: Danke!

- Graz

- Die Steiermärkische Landesbibliothek im neuen Joanneumsviertel

- Buch- und Literaturmuseen

- Labor, Speicher, Bühne: Das Literaturmuseum der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek

- Die Sammlung für Plansprachen und das Esperantomuseum der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek – Geschichte, Bestand und Projekte

- Das ist kein Papier

- Zeichen – Bücher – Netze: Das Deutsche Buch- und Schriftmuseum der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

- Weitere Beiträge

- Wohin geht die Reise? – Bibliothekspolitik am Anfang des 21. Jahrhunderts

- Die Tradition des Textes und die Herausforderung der Daten

- Quality Assessment for the Sustainable Provision of Software Components and Digital Research Infrastructures for the Arts and Humanities

- The World Digital Library

- Bibliotheks- und Informationseinrichtungen als Partner für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung

- Use of Private Sector Dynamism in Japanese Public Library: Ebina City Central Library

- Schulbibliotheken in der bibliothekarischen Literatur kontra Schulbibliotheken in der Praxis

- Rezensionen

- Frauke Schade (Hrsg.): Praxishandbuch digitale Bibliotheksdienstleistungen: Strategie und Technik der Markenkommunikation. Herausgabe unter Mitarbeit von Johannes Neuer, Redaktion Klaus Stelberg. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur, 2016. XVII, 435 Seiten, Illustrationen. ISBN 978-3-11-034648-0

- Cornelia Briel: Die Bücherlager der Reichstauschstelle. Mit einem Vorwort von Georg Ruppelt. Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann, 2016. (Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie; Sonderband 117). 360 S., 38 s/w. Abb., fest geb. ISBN 978-3-465-04249-5, ISSN 0514-6364. € 94,–

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titelseiten

- Inhaltsfahne

- Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

- Das frauen- und geschlechterspezifische Gedächtnis einer Universalbibliothek

- AKON – Ansichtskarten Online

- Die Katalogisierung der Bücher der ehemaligen Fideikommissbibliothek des Hauses Habsburg-Lothringen an der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek

- Maria Theresia sagt: Danke!

- Graz

- Die Steiermärkische Landesbibliothek im neuen Joanneumsviertel

- Buch- und Literaturmuseen

- Labor, Speicher, Bühne: Das Literaturmuseum der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek

- Die Sammlung für Plansprachen und das Esperantomuseum der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek – Geschichte, Bestand und Projekte

- Das ist kein Papier

- Zeichen – Bücher – Netze: Das Deutsche Buch- und Schriftmuseum der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

- Weitere Beiträge

- Wohin geht die Reise? – Bibliothekspolitik am Anfang des 21. Jahrhunderts

- Die Tradition des Textes und die Herausforderung der Daten

- Quality Assessment for the Sustainable Provision of Software Components and Digital Research Infrastructures for the Arts and Humanities

- The World Digital Library

- Bibliotheks- und Informationseinrichtungen als Partner für eine nachhaltige Entwicklung

- Use of Private Sector Dynamism in Japanese Public Library: Ebina City Central Library

- Schulbibliotheken in der bibliothekarischen Literatur kontra Schulbibliotheken in der Praxis

- Rezensionen

- Frauke Schade (Hrsg.): Praxishandbuch digitale Bibliotheksdienstleistungen: Strategie und Technik der Markenkommunikation. Herausgabe unter Mitarbeit von Johannes Neuer, Redaktion Klaus Stelberg. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur, 2016. XVII, 435 Seiten, Illustrationen. ISBN 978-3-11-034648-0

- Cornelia Briel: Die Bücherlager der Reichstauschstelle. Mit einem Vorwort von Georg Ruppelt. Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann, 2016. (Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie; Sonderband 117). 360 S., 38 s/w. Abb., fest geb. ISBN 978-3-465-04249-5, ISSN 0514-6364. € 94,–