Abstract

This study investigates the significant factor influencing widespread non-compliance with COVID-19 preventive measures in Seoul, Korea, through the analysis of spatial mobility data: the disparity between government communications and health policies, alongside the role of political orientation. The study reveals that political messages regarding quarantine success downplayed the severity of the virus, consequently hindering policy compliance during the major waves of COVID-19 in 2020–2021. Individuals with high institutional trust align their mobility behavior with the government’s messaging, increasing social activities. Additional channels come from the area’s occupation and industry characteristics, particularly in sectors with limited remote work availability.

Funding source: Yonsei Signature Research Cluster Program

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2021-22-0011

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hyunjin Kwon, Myungkyu Shim, Heather Royer, Xiu Lim, Valerie Ramey, and the seminar participants at Yonsei University, Sogang University, Ewha Womans University, Korea Labor Institute, 2022 Korea Empirical Applied Microeconomics Conference, and the 2023 Korea Economic Association Conference for their helpful comments. This project would not have been possible without the financial support from Yonsei Signature Research Cluster Program (grant number 2021–22–0011). There are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication that could have influenced its outcome.

Effect on reduction in public transit mobility (binary approval ratings specification).

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Second wave (Aug. 2020 – Sept. 2020) | Third wave (Nov. 2020 – Jan. 2021) | Fourth wave (Jul. 2021 – Aug. 2021) | |

| Panel A: Presidential election results (May 2017) | |||

| High approval rating × Post | 1.562*** (0.429) | 1.244*** (0.401) | 0.774*** (0.258) |

| High approval rating dummy | −0.304 (0.564) | −0.180 (0.555) | 0.105 (0.707) |

| Post | −23.95*** (0.446) | −27.33*** (0.342) | −15.32*** (0.340) |

| Mean of dep. variable | −30.53 | −36.91 | −30.53 |

| Observations | 6,784 | 6,784 | 6,784 |

| R-squared | 0.831 | 0.886 | 0.484 |

| Panel B: Legislative election results (April 2020) | |||

| High approval rating × Post | 1.310*** (0.433) | 1.149*** (0.400) | 0.906*** (0.257) |

| High approval rating dummy | 0.675 (0.497) | 0.994** (0.504) | 0.273 (0.635) |

| Post | −23.80*** (0.451) | −27.25*** (0.344) | −15.36*** (0.341) |

| Mean of dep. variable | −30.50 | −36.87 | −30.48 |

| Observations | 6,768 | 6,768 | 6,768 |

| R-squared | 0.834 | 0.889 | 0.486 |

-

Notes: Appendix Table 1 shows the estimation results using an alternative specification with a binary treatment variable D is , deviating from the continuous difference-in-differences setting. The treatment variable is a binary indicator separating wards into high-approval and low-approval groups based on the median percentage of votes received by the president and the ruling party. The dependent variable is the public transit mobility reduction rate for each corresponding period. The variable Post is the post-reference period dummy distinguishing the periods before and after the enforcement of mobility restriction measures. Panels A and B report the results estimated using two separate election outcomes. Each row represents the waves of COVID-19 outbreaks during 2020–2021. Standard errors are clustered at the ward level and reported in parentheses. The level of regional fixed effect is determined by 25 districts. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, and * p < 0.1.

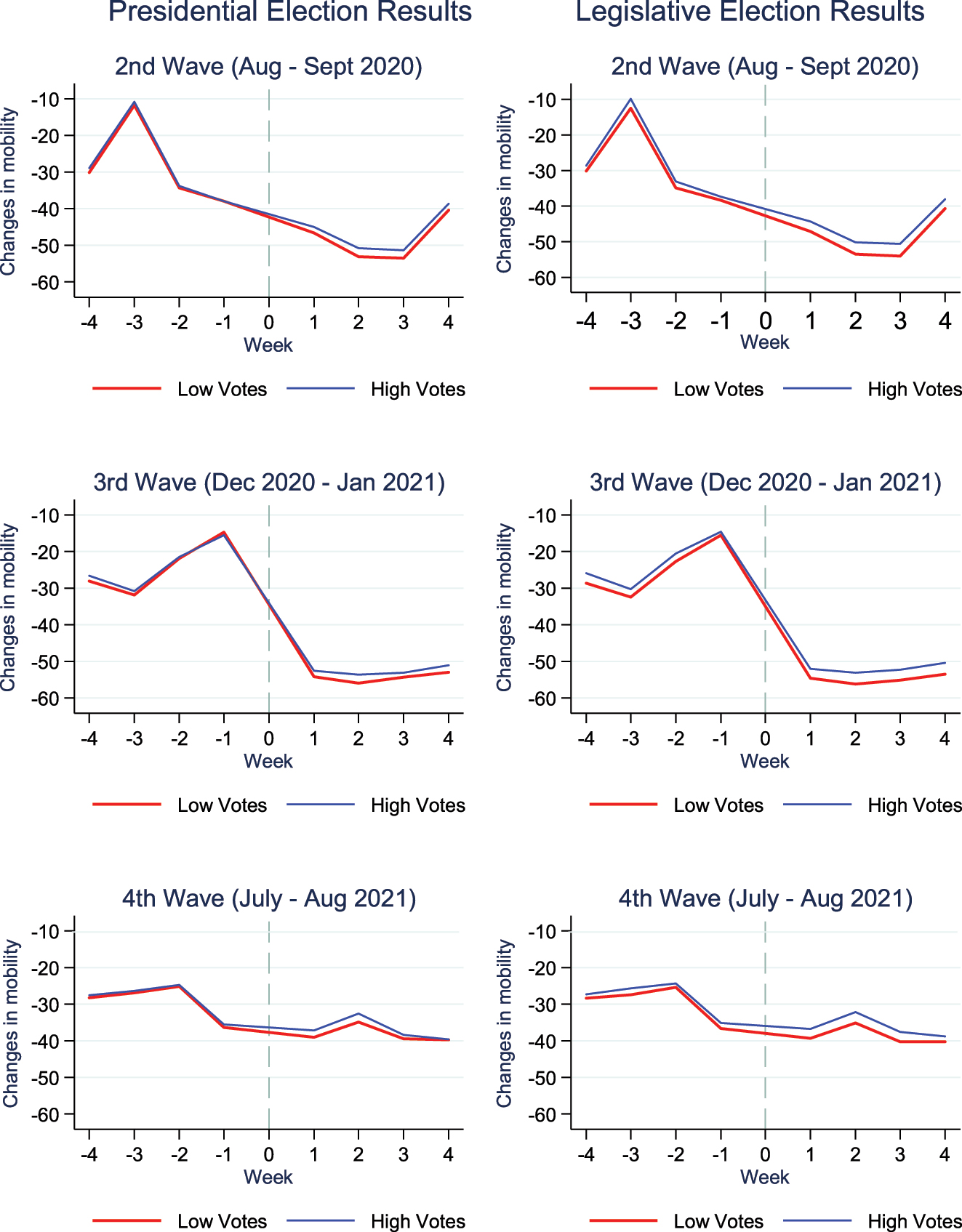

Public transit mobility reduction trend by votes received (only Sundays). Notes: Appendix Figure 1 presents mobility reduction rates for wards that have cast large votes on the president or the ruling congress party (blue line) and wards with fewer votes (bold red line). This figure reports the public transit mobility patterns of Sundays only, mitigating the concern that public transit usage on Saturdays may include commuting of workers. The green vertical line separates the treatment and reference periods. Both specifications using the presidential and legislative election results are presented. Among the four major waves of COVID-19, results for the second to fourth waves are provided. Note that the first wave is excluded from the analysis since the disease outbreak had a lesser effect on our region of interest.

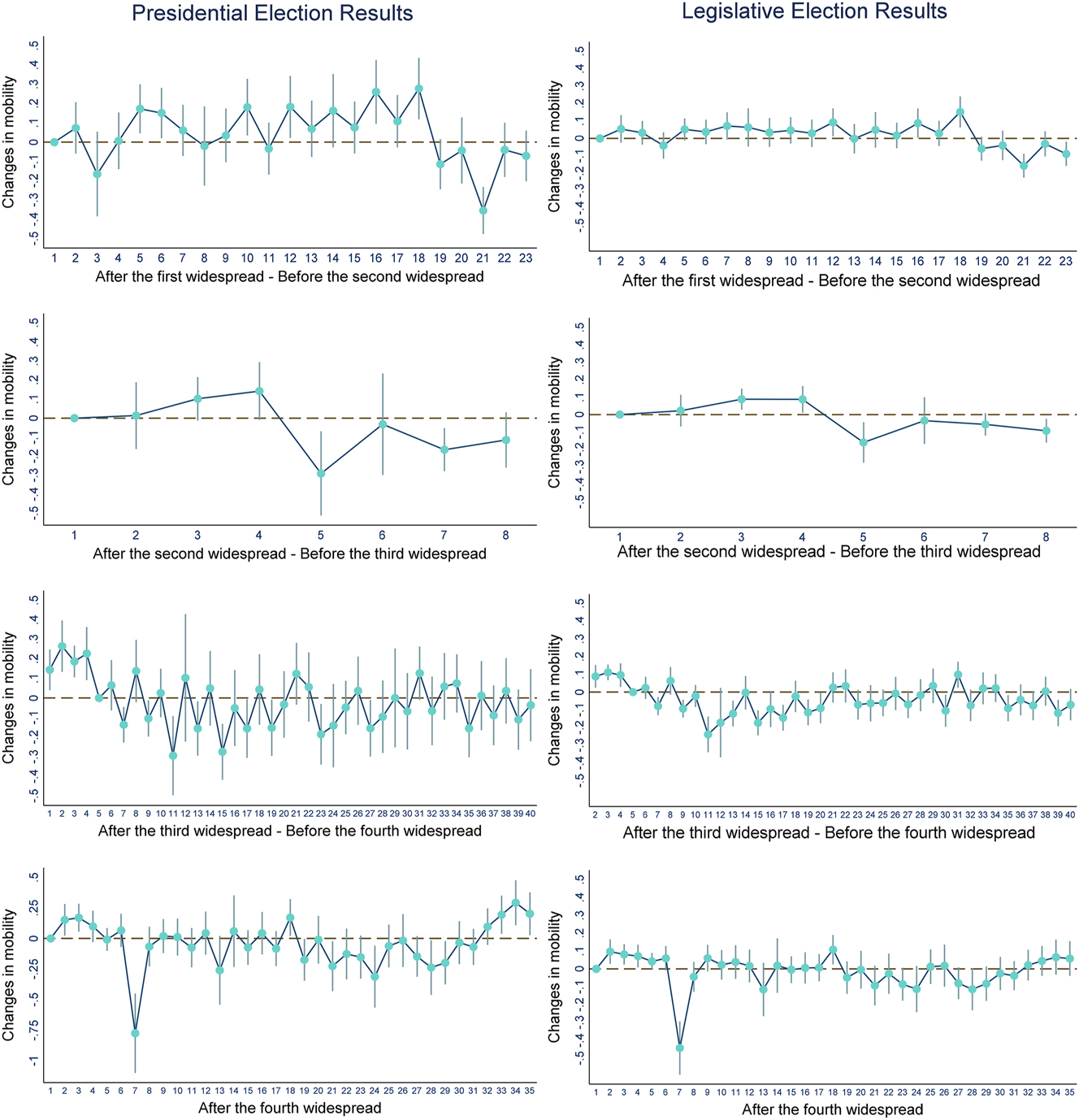

False specification test (all months and weeks excluding the main specification periods). Notes: Appendix Figure 2 displays the falsification test results. The figure plots coefficient estimates for every weekend day (Saturday and Sunday) that falls outside the main analysis window, capturing how mobility reduction rates vary by political orientation during periods unaffected by the policy shocks. We divide the timeline into four falsification periods situated before and after the three COVID-19 waves, where throughout these windows no official public messages were issued that might influence mobility. The left column presents results based on the presidential election, while the right column uses results from legislative elections as measures of political orientation. Vertical bars represent the 95 percent confidence intervals. Robust standard errors are clustered at the ward level. Regional fixed effects are determined by 25 districts.

References

Ajzenman, N., T. Cavalcanti, and D. Da Mata. 2023. “More than Words: Leaders’ Speech and Risky Behavior During a Pandemic.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 15 (3): 351–71. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20210284.Search in Google Scholar

Algan, Y., and P. Cahuc. 2014. “Trust, Growth, and Well-Being: New Evidence and Policy Implications.” In Handbook of Economic Growth, 2, 49–120. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-444-53538-2.00002-2Search in Google Scholar

Allcott, H., L. Boxell, J. Conway, M. Gentzkow, M. Thaler, and D. Yang. 2020. “Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Journal of Public Economics 191: 104254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254.Search in Google Scholar

Barbieri, P. N., and B. Bonini. 2021. “Political Orientation and Adherence to Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy.” Economia Politica 38 (2): 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-021-00224-w.Search in Google Scholar

Bargain, O., and U. Aminjonov. 2020. “Trust and Compliance to Public Health Policies in Times of COVID-19.” Journal of Public Economics 192: 104316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316.Search in Google Scholar

Barrios, J. M., and Y. Hochberg. 2020. Risk Perception Through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. (No. w27008). National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w27008Search in Google Scholar

Barrios, J. M., E. Benmelech, Y. V. Hochberg, P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales. 2021. “Civic Capital and Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Public Economics 193: 104310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104310.Search in Google Scholar

Bartscher, A. K., S. Seitz, S. Siegloch, M. Slotwinski, and N. Wehrhöfer. 2021. “Social Capital and the Spread of COVID-19: Insights from European Countries.” Journal of Health Economics 80: 102531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102531.Search in Google Scholar

Bavel, J. J. V., K. Baicker, P. S. Boggio, V. Capraro, A. Cichocka, M. Cikara, M. J. Crockett, et al.. 2020. “Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic Response.” Nature Human Behaviour 4 (5): 460–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z.Search in Google Scholar

Bodas, M., and K. Peleg. 2020. “Self-Isolation Compliance in the COVID-19 Era Influenced by Compensation: Findings from a Recent Survey in Israel: Public Attitudes Toward the COVID-19 Outbreak and Self-Isolation: A Cross Sectional Study of the Adult Population of Israel.” Health Affairs 39 (6): 936–41. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00382.Search in Google Scholar

Bonell, C., S. Michie, S. Reicher, R. West, L. Bear, L. Yardley, V. Curtis, R. Amlôt, and G. J. Rubin. 2020. “Harnessing Behavioural Science in Public Health Campaigns to Maintain ‘Social Distancing’ in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Key Principles.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 74 (8): 617–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214290.Search in Google Scholar

Briscese, G., N. Lacetera, M. Macis, and M. Tonin. 2020. Compliance with COVID-19 Social-Distancing Measures in Italy: The Role of Expectations and Duration, 27. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research.10.2139/ssrn.3567556Search in Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. COVID Data Tracker. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker.Search in Google Scholar

Chiou, L., and C. Tucker. 2020. Social Distancing, Internet Access and Inequality. (No. w26982). National Bureau of Economic Research.10.3386/w26982Search in Google Scholar

Corbu, N., E. Negrea-Busuioc, G. Udrea, and L. Radu. 2021. “Romanians’ Willingness to Comply with Restrictive Measures During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from an Online Survey.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 49 (4): 369–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2021.1912378.Search in Google Scholar

Coven, J., and A. Gupta. 2020. Disparities in Mobility Responses to COVID-19. 150, New York, NY: New York University.Search in Google Scholar

Dirks, K. T., and D. L. Ferrin. 2001. “The Role of Trust in Organizational Settings.” Organization Science 12 (4): 450–67. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640.Search in Google Scholar

Durante, R., L. Guiso, and G. Gulino. 2021. “Asocial Capital: Civic Culture and Social Distancing During COVID-19.” Journal of Public Economics 194: 104342, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104342.Search in Google Scholar

Galasso, V., V. Pons, P. Profeta, M. Becher, S. Brouard, and M. Foucault. 2020. “Gender Differences in COVID-19 Attitudes and Behavior: Panel Evidence from Eight Countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (44): 27285–91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2012520117.Search in Google Scholar

Garrett, L. 2020. “COVID-19: The Medium is the Message.” The Lancet 395 (10228): 942–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30600-0.Search in Google Scholar

Gollwitzer, A., C. Martel, W. J. Brady, P. Pärnamets, I. G. Freedman, E. D. Knowles, and J. J. Van Bavel. 2020. “Partisan Differences in Physical Distancing Are Linked to Health Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nature Human Behaviour 4 (11): 1186–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00977-7.Search in Google Scholar

Grimalda, G., F. Murtin, D. Pipke, L. Putterman, and M. Sutter. 2023. “The Politicized Pandemic: Ideological Polarization and the Behavioral Response to COVID-19.” European Economic Review 156: 104472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2023.104472.Search in Google Scholar

Grossman, G., S. Kim, J. M. Rexer, and H. Thirumurthy. 2020. “Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors’ Recommendations for COVID-19 Prevention in the United States.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (39): 24144–53. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007835117.Search in Google Scholar

Job Korea. 2018. Survey on Weekend Work Status. https://www.jobkorea.co.kr/futurelab.Search in Google Scholar

Jung, K. H., J. Y. Lee, and J. W. Yun. 2021. “A Study of COVID-19 Pandemic and Disaster Relief Fund –The Case of Emergency Disaster Relief Fund in Korea.” Crisonomy 17 (3): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.14251/crisisonomy.2021.17.3.1.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, E. A. 2020. “Social Distancing and Public Health Guidelines at Workplaces in Korea: Responses to Coronavirus Disease-19.” Safety and Health at Work 11 (3): 275–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2020.07.006.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, S., K. Koh, and W. Lyou. 2023. “Spend as You Were Told: Evidence from Labeled COVID-19 Stimulus Payments in South Korea.” Journal of Public Economics 221: 104867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104867.Search in Google Scholar

Knack, S., and P. Keefer. 1997. “Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (4): 1251–88. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300555475.Search in Google Scholar

Korea.net. 2020a. Presidential Speeches (Feb 10, 2020): Opening Remarks by President Moon Jae-In at Meeting with His Senior Secretaries [Speech transcript].Search in Google Scholar

Korea.net. 2020b. Presidential Speeches (Mar 20, 2020): Opening Remarks by President Moon Jae-In at 3rd Emergency Economic Council Meeting [Speech transcript].Search in Google Scholar

Korea.net. 2020c. Presidential Speeches (Jul 14, 2020): Keynote Address by President Moon Jae-In at Presentation of Korean New Deal Initiative [Speech transcript].Search in Google Scholar

Korea.net. 2020d. Presidential Speeches (Nov 02, 2020): Opening Remarks by President Moon Jae-In at Meeting with His Senior Secretaries [Speech transcript].Search in Google Scholar

Korea.net. 2021a. Presidential Speeches (May 10, 2021): Special Address by President Moon Jae-In to Mark Four Years in Office [Speech transcript].Search in Google Scholar

Korea.net. 2021b. Presidential Speeches (Jun 07, 2021): Remarks by President Moon Jae-In at 3rd Special Meeting to Check Epidemic Prevention and Control Against COVID-19 [Speech transcript].Search in Google Scholar

Lau, D. T., and P. Sosa. 2022. “Disparate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Equity Data Gaps.” American Journal of Public Health 112 (10): 1404–6. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2022.307052.Search in Google Scholar

Lau, J. T., J. H. Kim, H. Tsui, and S. Griffiths. 2007. “Perceptions Related to Human Avian Influenza and Their Associations with Anticipated Psychological and Behavioral Responses at the Onset of Outbreak in the Hong Kong Chinese General Population.” American Journal of Infection Control 35 (1): 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2006.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, M., and M. You. 2021. “Effects of COVID-19 Emergency Alert Text Messages on Practicing Preventive Behaviors: Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey in South Korea.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 23 (2): e24165. https://doi.org/10.2196/24165.Search in Google Scholar

Marien, S., and M. Hooghe. 2011. “Does Political Trust Matter? An Empirical Investigation into the Relation Between Political Trust and Support for Law Compliance.” European Journal of Political Research 50 (2): 267–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x.Search in Google Scholar

Marist. 2020. March 13th and 14th Survey of American Adults. http://maristpoll.marist.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NPR_PBS-NewsHour_Marist-Poll_USA-NOS-and-Tables_2003151338.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Martinescu, E., T. D. D. Cruz, T. W. Etienne, and A. Krouwel. 2023. “How Political Orientation, Economic Precarity, and Participant Demographics Impact Compliance with COVID-19 Prevention Measures in a Dutch Representative Sample.” Acta Politica 58 (2): 337. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00246-7.Search in Google Scholar

Office for National Statistics. 2021. Deaths Registered Weekly in England and Wales, Provisional. https://www.ons.gov.uk/.Search in Google Scholar

Palm, R., T. Bolsen, and J. T. Kingsland. 2021. “The Effect of Frames on COVID-19 Vaccine Resistance.” Frontiers in Political Science 3: 661257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.661257.Search in Google Scholar

Park, S., S. Lee, and J. Cho. 2021. “Uneven Use of Remote Work to Prevent the Spread of COVID-19 in South Korea’s Stratified Labor Market.” Frontiers in Public Health 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.726885.Search in Google Scholar

Piacenza, J. 2020. Tracking Public Opinion on the Coronavirus. New York City, Chicago: Morning Consult.Search in Google Scholar

Quinn, S. C., J. Parmer, V. S. Freimuth, K. M. Hilyard, D. Musa, and K. H. Kim. 2013. “Exploring Communication, Trust in Government, and Vaccination Intention Later in the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic: Results of a National Survey.” Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science 11 (2): 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2012.0048.Search in Google Scholar

Republic of Korea Employment and Labor Statistics. 2020. Job Statistics Data [Data set]. http://laborstat.moel.go.kr/.Search in Google Scholar

Republic of Korea National Election Commission. 2020. Republic of Korea Election Statistics Data [Data set]. https://www.nec.go.kr/site/eng/main.do.Search in Google Scholar

Saad, L. 2020. Americans Step Up Their Social Distancing Even Further. Washington, D.C., USA: Gallup.Search in Google Scholar

Seong, H., H. J. Hyun, J. G. Yun, J. Y. Noh, H. J. Cheong, W. J. Kim, and J. Y. Song. 2021. “Comparison of the Second and Third Waves of the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea: Importance of Early Public Health Intervention.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 104: 742–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.004.Search in Google Scholar

Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2022. Public Transit Usage Status [Data set]. https://news.seoul.go.kr/traffic/archives/31616.Search in Google Scholar

Seoul Open Data Service. 2021. Seoul City Demographic Information Data [Data set]. https://data.seoul.go.kr/.Search in Google Scholar

Seoul Open Data Service. 2022. Seoul City Bus Boarding Data [Data set]. https://data.seoul.go.kr/.Search in Google Scholar

Statistics Korea. 2020. Report on the Transportation Survey [Data set]. https://kostat.go.kr/.Search in Google Scholar

Statistics Korea. 2021. Korean National Balance Sheets for 2021, https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20110040000&bid=11756&act=view&list_no=419400.Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, M., B. Raphael, M. Barr, K. Agho, G. Stevens, and L. Jorm. 2009. “Public Health Measures During an Anticipated Influenza Pandemic: Factors Influencing Willingness to Comply.” Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2: 9. https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.s4810.Search in Google Scholar

Van der Weerd, W., D. R. Timmermans, D. J. Beaujean, J. Oudhoff, and J. E. Van Steenbergen. 2011. “Monitoring the Level of Government Trust, Risk Perception and Intention of the General Public to Adopt Protective Measures During the Influenza A (H1N1) Pandemic in the Netherlands.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-575.Search in Google Scholar

Vaughan, E., and T. Tinker. 2009. “Effective Health Risk Communication About Pandemic Influenza for Vulnerable Populations.” American Journal of Public Health 99 (S2): S324–32. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.162537.Search in Google Scholar

Yang, S., J. Jang, S. Y. Park, S. H. Ahn, S. S. Kim, S. B. Park, and N. Y. Kim. 2022. “COVID-19 Outbreak Report from January 20, 2020 to January 19, 2022 in the Republic of Korea.” Public Health Weekly Report 15 (7): 414–26.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Fair Choices During COVID-19: Firms’ Altruism and Inequality Aversion in Managing a Large Short-Time Work Scheme

- Inequality in Health Status During the COVID-19 in the UK: Does the Impact of the Second Lockdown Policy Matter?

- The Political Timing of Tax Policy: Evidence from U.S. States

- Is it a Matter of Skills? High School Choices and the Gender Gap in STEM

- Patent Licensing and Litigation

- Class Size, Student Disruption, and Academic Achievement

- Political Orientation and Policy Compliance: Evidence from COVID-19 Mobility Patterns in Korea

- Social Efficiency of Free Entry in a Vertically Related Industry with Cost and Technology Asymmetry

- Carbon Tax with Individuals’ Heterogeneous Environmental Concerns

- Equitable Redistribution and Inefficiency under Credit Rationing

- Letters

- Psychological Well-Being of Only Children: Evidence from the One-Child Policy

- Peer Effects in Child Work Decisions: Evidence from PROGRESA Cash Transfer Program

- Right Time to Focus? Time of Day and Cognitive Performance

- Employee Dissatisfaction and Intentions to Quit: New Evidence and Policy Recommendations

- On the Stability of Common Ownership Arrangements

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Fair Choices During COVID-19: Firms’ Altruism and Inequality Aversion in Managing a Large Short-Time Work Scheme

- Inequality in Health Status During the COVID-19 in the UK: Does the Impact of the Second Lockdown Policy Matter?

- The Political Timing of Tax Policy: Evidence from U.S. States

- Is it a Matter of Skills? High School Choices and the Gender Gap in STEM

- Patent Licensing and Litigation

- Class Size, Student Disruption, and Academic Achievement

- Political Orientation and Policy Compliance: Evidence from COVID-19 Mobility Patterns in Korea

- Social Efficiency of Free Entry in a Vertically Related Industry with Cost and Technology Asymmetry

- Carbon Tax with Individuals’ Heterogeneous Environmental Concerns

- Equitable Redistribution and Inefficiency under Credit Rationing

- Letters

- Psychological Well-Being of Only Children: Evidence from the One-Child Policy

- Peer Effects in Child Work Decisions: Evidence from PROGRESA Cash Transfer Program

- Right Time to Focus? Time of Day and Cognitive Performance

- Employee Dissatisfaction and Intentions to Quit: New Evidence and Policy Recommendations

- On the Stability of Common Ownership Arrangements