Can we train young EFL learners to ‘notice the gap’? Exploring the relationship between metalinguistic awareness, grammar learning and the use of metalinguistic explanations in a dictogloss task

Abstract

In this pilot study we investigated whether metalinguistic explanations (ME) could help young learners (YL) boost their metalinguistic awareness (MA) and, in turn, improve their accuracy at the time of using two grammatical features. Although previous research has established a positive correlation between MA, metalinguistic knowledge (MK) and better learning outcomes in a foreign language (FL), few interventional studies have been conducted in this regard. Using a pretest/post-test design, an intact classroom (N = 20) of L1 Spanish 10-year-old students of English as a FL (EFL) was divided into an experimental and a control group. First, both groups completed an individual pen-and-paper MA test. Then, they were paired up according to their proficiency level and asked to carry out a dictogloss task, in which they had to negotiate their final written output. Before the post-test phase, the experimental group was asked to engage with a learning sequence of ME concerning two problematic English grammatical features: third person –s and his/her. These explanations also included the definitions of metalinguistic terminology. Additionally, an individual three-step verbal protocol was carried out after the post-tests to triangulate collaborative data. The results showed a moderate effect of the treatment in MA scores. Likewise, ME had a large effect on the use of third person –s during the interaction, as well as a moderate effect on the accurate use of his/her. Also, the treatment group dyads produced significantly more episodes of noticing during the post-test task and at a higher resolution rate than during the pretest stage. These findings support the use of explicit learning devices such as ME with YL of EFL, as they seem to promote MA and increase their accuracy even in input-limited learning conditions.

1 Introduction

The attainment of one or more foreign languages (FLs) has been at the centre of most educational programmes throughout the last few decades, with policymakers setting the age of first exposure at increasingly younger ages (Wei 2022). In the case of Spain, Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL; Coyle 2007) programmes have become the norm across the country (Palacios-Hidalgo et al. 2022), with learners being introduced to a FL for the first time at ages as young as 3 (San Isidro and Huerga 2023). However, while it is known that children tend to rely on input-dependent implicit mechanisms for learning in naturalistic settings, as explicit learning demands a heavy cognitive load (DeKeyser 2003), research has so far failed to find an age advantage in instructed FL settings (e.g. Huang 2015; Larson-Hall 2008). In a classroom context, where meaningful input is often restricted in both quantity and quality, learners seem to face a very different set of challenges. These challenges are even more complex in the case of learners under 12, also known as young learners (YLs; Pinter 2012), who are not fully developmentally ready to make extensive use of explicit learning resources. Nevertheless, this does not mean that YLs cannot employ explicit learning mechanisms at all (Roehr-Brackin 2024); in fact, when it comes to grammar learning, focusing learners’ attention on forms (FonF; Long 1996) has extensively been proven effective to increase YLs’ accuracy in the FL (e.g. Calzada and García Mayo 2021; Roothooft et al. 2022). In this regard, explicit interventions appear to be a path worth exploring to find cost-effective approaches to maximising the benefits of the limited instruction time YLs get.

In the light of the above, metalinguistic awareness (MA), or the ability to treat language as an object of reflection rather than as a mere tool of use with an instrumental purpose (Bialystok 2001), is an individual variable that has been shown to positively correlate with successful learning of FL grammar in children as young as 8 (Roehr-Brackin and Tellier 2019). As a conscious feature, MA is related to explicit learning, declarative knowledge and literacy, and is closely tied to metalinguistic knowledge (MK), or knowledge about how language works (Gombert 1992; Roehr-Brackin 2018). As explained by Tellier, “it is reasonable to assume that an individual’s level of metalinguistic awareness would impact positively on explicit learning, and thus facilitate L2 learning” (Tellier 2013: 18). As it has been recently demonstrated, MA is susceptible to changes (Roehr-Brackin and Tellier 2019) and can increase after a deliberate pedagogical intervention (Kasprowicz et al. 2022). The development of MA, therefore, appears to be a worthwhile course of action to boost the effects of instruction not only in adult FL learning settings (D’Angelo and Sorace 2022), but also in pimary school classrooms.

In the following pilot study, we aim to report our findings after a short form-focused intervention designed with the goal of increasing YLs’ MA. This intervention consists of a series of age-appropriate metalinguistic explanations (ME), which are consciousness-raising direct annotations that explain how a given morphosyntactic feature works (Ellis 1997; Shintani and Ellis 2013). ME have been proven to raise awareness and lead to increases in accuracy in adults (Fotos 1994; Fotos and Ellis 1991; Shintani and Ellis 2013; Shintani et al. 2016) and adolescents (Bozorgian and Yazdani 2021) but have been only recently tested in children (Gorman and Ellis 2019; Kasprowicz et al. 2022). Our study aims to bridge this gap and contribute to generate evidence in regards to this understudied segment of the population, as well as to extend the findings of Kasprowicz et al. (2022) in regards to the relationship between MA and ME. Likewise, we aim to explore how gains in MA reflect on learners’ accuracy at the time of employing two previously explained target features (TF) during the interaction on a collaborative task.

2 Literature review

2.1 The role of consciousness in language learning

The differences between implicit and explicit learning mechanisms originate in the role that consciousness plays in the process as a whole. As defined by Ellis and Larsen-Freeman (2006), consciousness “is the publicity organ of the brain. It is a facility for accessing, disseminating, and exchanging information, and for exercising global coordination and control. This is the interface, the stuff of learning” (Ellis and Larsen-Freeman 2006: 571). While implicit knowledge is unconscious, procedural in nature and only accessible through automatic processing, explicit knowledge is fully conscious, declarative and accessible through controlled processing (Ellis 2009). In terms of processing costs, implicit learning does not demand as many attentional resources as explicit learning, which seems to take a heavy cognitive load, especially in terms of working memory capacity (WMC; DeKeyser 2003; Roehr-Brackin 2018). As these attentional resources gradually increase with age, teenagers and adults show better developmental readiness than younger learners and, in turn, should be better prepared to deal with the higher processing toll that explicit learning processes require. This is the reason why adults tend to fare better at explicit learning, while children seem to thrive in input-rich naturalistic settings. However, this does not mean that adults or children make exclusive use of only one of the two types of learning (Roehr-Brackin 2024). In this regard, as intentionality also lies at the very core of the distinction, implicit learning mechanisms seem to relate to comprehension and production processes, while explicit learning takes place at the time of purposefully negotiating meaning and establishing deliberate attempts to communicate in a successful manner (Ellis 2005). Nonetheless, these associations do not imply that these processes remain separate in any way; on the contrary, the nature of a potential interaction between implicit and explicit learning processes has remained a point of contention in research for a long time. A few decades ago, the non-interface position, related to Krashen’s Monitor model (Krashen 1982), stated that both types of knowledge pertained to separate domains and would not interact. However, the development of Skill Acquisition Theory (e.g. Anderson 1985; McLaughlin 1990) led to a change in the general consensus, in what was later described as the strong-interface position: controlled, intentional use of explicit knowledge can lead to automatic (i.e. unconscious) processing of information. Nevertheless, since the late 80’s increasing evidence started to point that explicit knowledge cannot be internalised without conscious awareness on behalf of the learner (Ellis 2002, 2009; Schmidt and Frota 1986; Swain 1985). This final compromise stance, or weak-interface position, is now the most widely accepted view, as well as the framework we have decided on for this study.

In this regard, the cognitive-interactionist (CI) framework and sociocultural theory (SCT) have made relevant contributions at the time of theoretically explaining how noticing processes influence explicit learning. For instance, Long’s Interaction Hypothesis (IH; 1996) poses that the environmental factors (e.g. another learner’s L2 production, feedback) that surround a learner of a given language are tied to the learner’s internal cognitive processes. Likewise, the concept of negotiation of meaning (NoM; Long 1983), formally defined as “the process whereby interactions are modified between or among conversational partners to help overcome communication breakdowns” (Oliver 1998: 373), also makes extensive use of noticing processes during the interaction. At the same time, from the SCT perspective, Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is another example of noticing-mediated internalisation of declarative knowledge. Defined as “the domain or skill where the learner is not yet capable of using the L2 autonomously as procedural knowledge but where, with the scaffolded assistance of the more proficient partner, level of performance can be raised” (Bitchener and Ferris 2012: 18–19), this concept is crucial to understand how scaffolding devices can help YLs pick up otherwise neglected grammatical forms.

2.2 Metalinguistic awareness and metalinguistic explanations

MA can be thought of as the activity of thinking of language as an object of reflection rather than as a mere tool of use (Bialystok 2001). The notion of MA is closely related to explicit knowledge and, more precisely, to metalinguistic knowledge, or knowledge about how language works (Gombert 1992). Likewise, MA is also tied to the notion of metalinguistic ability, understood as the ability to use metalinguistic knowledge (Bialystok 2001; Birdsong 1989). As discussed in several works by Roehr-Brackin (e.g. 2018, 2024), these constructs capture different nuances about the same underlying concept and are interchangeably used in practice. MA could be defined, then, as the conscious attention a learner allocates to their explicit knowledge about language, rather than the capacity to use language. As stated above, several studies have demonstrated that higher levels of MA in YL are positively correlated with better learning outcomes in a FL (Roehr-Brackin and Tellier 2019; Tellier 2013) and have demonstrated that MA can be raised by means of an explicit intervention (Kasprowicz et al. 2022). In this regard, ME could be a potentially effective tool for raising MA in learners, as they explicitly supply learners with metalinguistic knowledge. ME can be defined as brief, explicit annotations that explain how a given language feature works. They can be considered a form of direct written corrective feedback (WCF) that learners can engage with and may serve to assist them at the time of dealing with problematic features (e.g. those that involve a higher degree of saliency). Nevertheless, only a couple of studies have targeted the development of MA through explicit instruction, and the existing evidence seems to be conflicting: while Serrano (2011) failed to significantly increase metalinguistic knowledge by means of rule-based instruction in 11-year-olds, Kasprowicz et al. (2022) succeeded at the time of developing MA in YLs after the participants engaged with ME.

2.3 Task-based language teaching and collaborative writing with young EFL learners

In the transition to more communicative approaches to language teaching, Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) can be considered an alternative that has succeeded at the time of putting forward a content-based approach with a focus on form in YLs (Ellis 2020). A particular emphasis should be placed on collaborative tasks due to their effectiveness at the time of promoting FL learning (as supported by the IH) and the opportunities for production they generate. In this regard, collaborative writing tasks represent a powerful combination of multimodal production and reception practice. The writing-to-learn and specifically the writing-to-learn-the-language (WLL) perspectives (Manchón 2011) put forward the notion that, as demonstrated by an extensive body of research (Lázaro-Ibarrola 2023), writing practice promotes FL learning in YLs. Moreover, writing tasks do not only develop writing skills in YLs but can also offer valuable opportunities for oral interaction and hypothesis testing. A prime example is that of dictogloss (Wajnryb 1990), a text reconstruction task which in its collaborative form combines both oral and written input and output. As both negotiation of meaning and a pressing need to be understood are present during the execution of this task, it is, therefore, expected to tap the explicit knowledge that ME are aiming to increase. As a focused intervention (Storch 2016), this task has already been proven effective at the time of drawing attentional resources to form in a communicative context in adults (Alegría de la Colina and García Mayo 2007), secondary school learners (Basterrechea and García Mayo 2013; Basterrechea and Leeser 2019), and, most recently, primary school children (Calzada and García Mayo 2020a, 2020b, 2021). For these reasons, we chose the dictogloss task as an ecologically valid method for generating form-focused interaction in the classroom.

3 The study

The present study is based on a simple syllogistic working assumption. Explicit metalinguistic explanations (ME) should improve learners’ metalinguistic knowledge, increased metalinguistic knowledge should lead to increased metalinguistic awareness, and increased metalinguistic awareness should lead to higher accuracy. Following this reasoning, we aim to find an answer to the research questions (RQ) below:

RQ1.

Can metalinguistic explanations boost metalinguistic awareness? Specifically, can metalinguistic explanations help L1 Spanish English as a foreign language (EFL) young learners improve their scores at a metalinguistic awareness test?

RQ2.

Can metalinguistic explanations improve learners’ performance in regards to two grammatical features? Specifically, can metalinguistic explanations about third person –s and his/her help L1 Spanish EFL young learners improve their accuracy scores at the time of using them in the interaction during a dictogloss task?

RQ3.

Can metalinguistic explanations boost noticing at the time of performing a dictogloss task? Specifically, can metalinguistic explanations promote the correct resolution of form-focused language-related episodes (LREs) in L1 Spanish EFL learners?

4 Participants, materials and methods

4.1 Participants

Our participants were from an intact Primary Year 5 classroom at a state school in Zaragoza, Aragón Autonomous Community, Spain. The school is located at the intersection between a working-class and a middle-class neighbourhood: the socioeconomic backgrounds of the different participants were, thus, very diverse. This school takes part in a French CLIL programme. It should be noted, though, that English is still considered the main foreign language at the school, which implies that, as per the regional curriculum (Gobierno de Aragón 2016, 2022), primary students engage in 150 min of EFL instruction per week. This translates to a cumulative exposure of approximately 400 h of EFL instruction at the beginning of Year 5. The school favours a Project-Based Learning (PBL) approach at EFL during the whole Primary Education stage.

The initial sample of the study consisted of 20 pupils that had already turned or were about to turn 10 years old at the beginning of the school year. However, data sets pertaining to four pupils had to be discarded due to either insufficient literacy skills to comply with the tasks or refusal to engage in oral interaction. The final sample, then, comprised data from 16 students that were paired up in eight dyads during the main task. These eight dyads were equally split into a control group (CG, N = 8) and a treatment group (TG, N = 8).

A background 10 min questionnaire was distributed in order to control for language practices outside of the classroom. The questionnaire included eight questions about matters such as the languages the students and their primary caretakers spoke, the age they were when they first received formal EFL instruction, their degree of self-perceived proficiency at English, French, Spanish and other languages, and whether they received additional instruction outside of the curricular context. Even though six children referred to using languages other than Spanish, English or French at home, independent samples T-tests revealed no significant differences in performance at either the metalinguistic awareness test or the proficiency test between monolingual L1 Spanish children and children who had knowledge of additional languages. Likewise, the Cambridge Flyers test (2018), corresponding to a Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) A2 level (Council of Europe 2001), was used as a measure of proficiency. We paired up students with similarly proficient counterparts, as we sought to foster collaboration and interaction in the FL during the completion of the task (Storch and Aldosari 2013; Vraciu and Pladevall-Ballester 2022).

4.2 Design, procedure and instruments

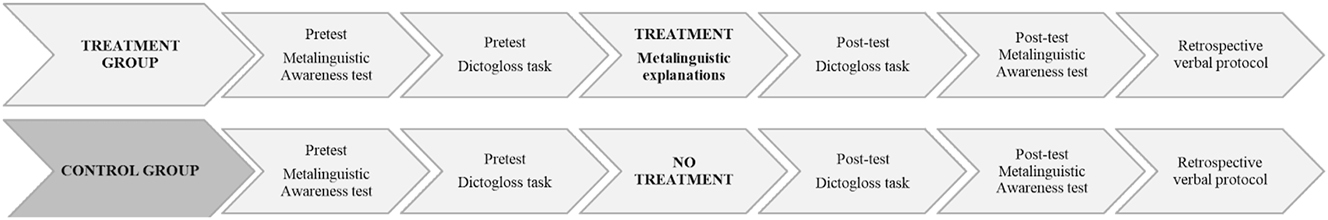

Our experiment followed a one-shot pretest/post-test design. After the background and proficiency tests were completed, the data collection process began with the administration of an MA test (Tellier 2013). Then, the dyads completed the pretest dictogloss task over the course of two weeks. Every data collection session aimed to gather data from both TG and CG dyads, so that distance to the MA test was as even as possible across dyads. After all the dyads had finished the pretest stage, the post-test dictogloss task was administered, immediately preceded by the ME treatment in the case of the TG. No filler task was delivered to the CG in order not to prime students or interfere with additional variables that will be taken into account in future studies. The students in the TG received the intervention in dyads in a separate room following the protocol described in 4.2.3 below. During this time, the rest of their peers remained in class so as to minimise the impact of the study on their regular classroom activities. After the (immediate) post-test dictogloss tasks had been completed over the course of another two weeks, the same MA test that was previously used in the pretest stage was distributed to the classroom. Finally, an individual verbal protocol was administered to each child so that pair data could be triangulated. Figure 1 illustrates the procedure, whose specifics will be discussed below.

Design.

4.2.1 Metalinguistic awareness test

The test that has been used as a measure of MA in our study, which was created by Tellier (2013), encompasses a series of tasks that “treat metalinguistic awareness as a set of general cognitive skills applicable to both L1 and L2 learning” (Tellier 2013: 19). Even though the THAM-2 battery (Núñez Delgado and Pinto 2015) has been fruitfully employed in the Spanish context by several researchers (e.g. Lasagabaster Herrarte 1998), we decided against its use due to two practical concerns. First, due to strict time constraints having to do with the school’s tight schedule, a test that could be reliably administered in less than 60 min was needed for our context. Likewise, given its heavy reliance on the Spanish language across all of its tasks, we deemed it less suitable to use for such a diverse classroom, as the pupils’ level of communicative competence in Spanish could not be accurately determined before the administration of the MA test. Tellier’s test, which has successfully demonstrated robust validity and reliability in previous research (Roehr-Brackin and Tellier 2019; Tellier 2013), makes use of a wide range of natural and artificial languages, thus reducing the reliance on Spanish to produce accurate measurements of MA. This is also the case of Haugen, Carlsen and Möller-Omrani’s test (2024), which also includes illustrations for ease of understanding; however, it was not available to us at the time, leaving us with Tellier’s test as the safest choice for our context. The original English version, which can be found on the IRIS database (Marsden et al. 2016), was translated into Spanish by a member of the research group. The Spanish version of the instrument offers adequate levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.846). The pen-and-paper test is approximately 50 min long and encompasses 11 small language manipulation tasks distributed in two parts: in the first one, students need to rely on previous knowledge of natural languages, while during the second part the learners are asked to manipulate an artificial language. No previous training was delivered to the students beforehand. The test was explained and delivered by the researcher with the help of the student’s tutor. The children were allowed to ask questions about the instructions of the different tasks, but assistance was only provided if it was actually needed to understand what the task required the students to do.

4.2.2 Dictogloss task

In this particular study, the target features the learners were prompted to focus on were the third person singular marker morpheme -s and possessives his and her, since both forms have been proven to be problematic to acquire for L1 Spanish EFL learners. The reasons behind this phenomenon are tied to different causes. For example, third person -s, as explained by Basterrechea and Leeser (2019: 102), following Goldshneider and DeKeyser’s (2005) framework, “might be a morpheme difficult to acquire, because it is not a perceptually salient morpheme, it is not morphophonologically regular, and it is a redundant morphosyntactic form”. Likewise, the case of his/her is especially pervasive to native speakers of Romance languages, as negative crosslinguistic transfer may occur: in English the use of possessive determiners depends on the nature gender of the possessor whereas in Spanish possessive determiners agree with the gender and the number of the possessed entity (see Imaz Agirre and García Mayo 2013).

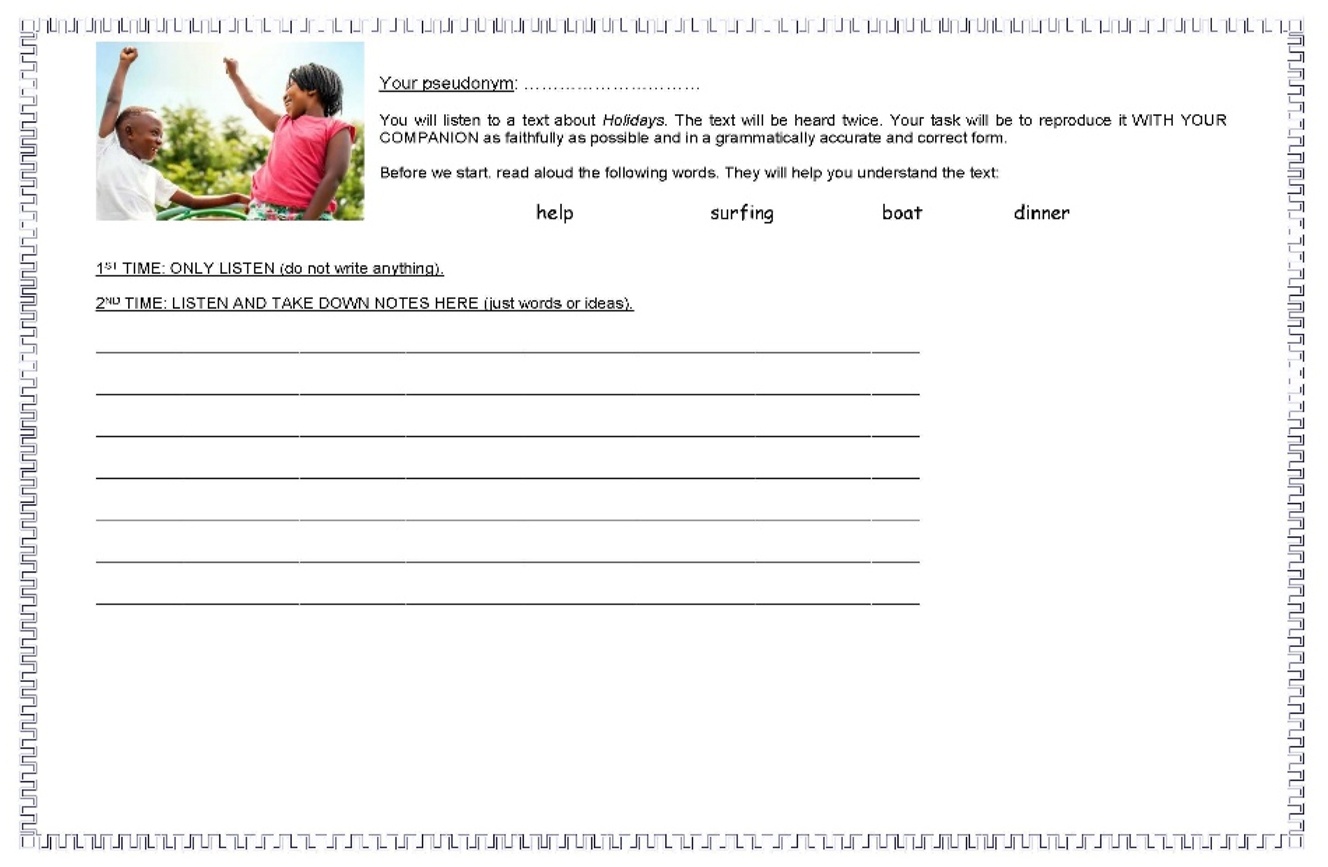

In this experiment, two short texts that focused on the aforementioned target features (TF) were used. They were developed by members of the research project and were previously used in analogous studies with a slightly older population. The texts were descriptive in nature and versed about topics that were familiar to the students, such as family celebrations (pretest) and holidays (post-test). Each text included eight instances of every TF (his, N = 4; her, N = 4; -s, N = 8) and was of exactly the same length (107 words). The oral input was recorded by the same speaker in .mp3 archives of even durations, namely, 55 and 54 s for the pretest and the post-test, and was simultaneously delivered to both students in every dyad using a computer and headphones so that ambient noise levels could be controlled. In addition to this, the students were handed out a paper sheet (Appendix 1) which served three purposes: it provided input redundancy, could be used as a note-taking tool and acted as the text reconstruction instrument.

The dictogloss task was entirely carried out in English and began when the participants listened to the recording for the first time after being advised to focus on understanding the input. Afterwards, they were told to listen to the text once again, but this second time around they were encouraged to take notes as they pleased. Finally, the learners were instructed to reconstruct the text in a grammatically accurate way using their notes and their own memory. Only one of the two students in every dyad was instructed to write the final negotiated reconstruction of the text. The interactions that led to the final written output were recorded in audio and video and transcribed using CHILDES (MacWhinney 2000). This procedure was executed in a separate room outside of the main classroom so as to ensure optimal levels of intelligibility and minimise the risk of distractions or disruptions.

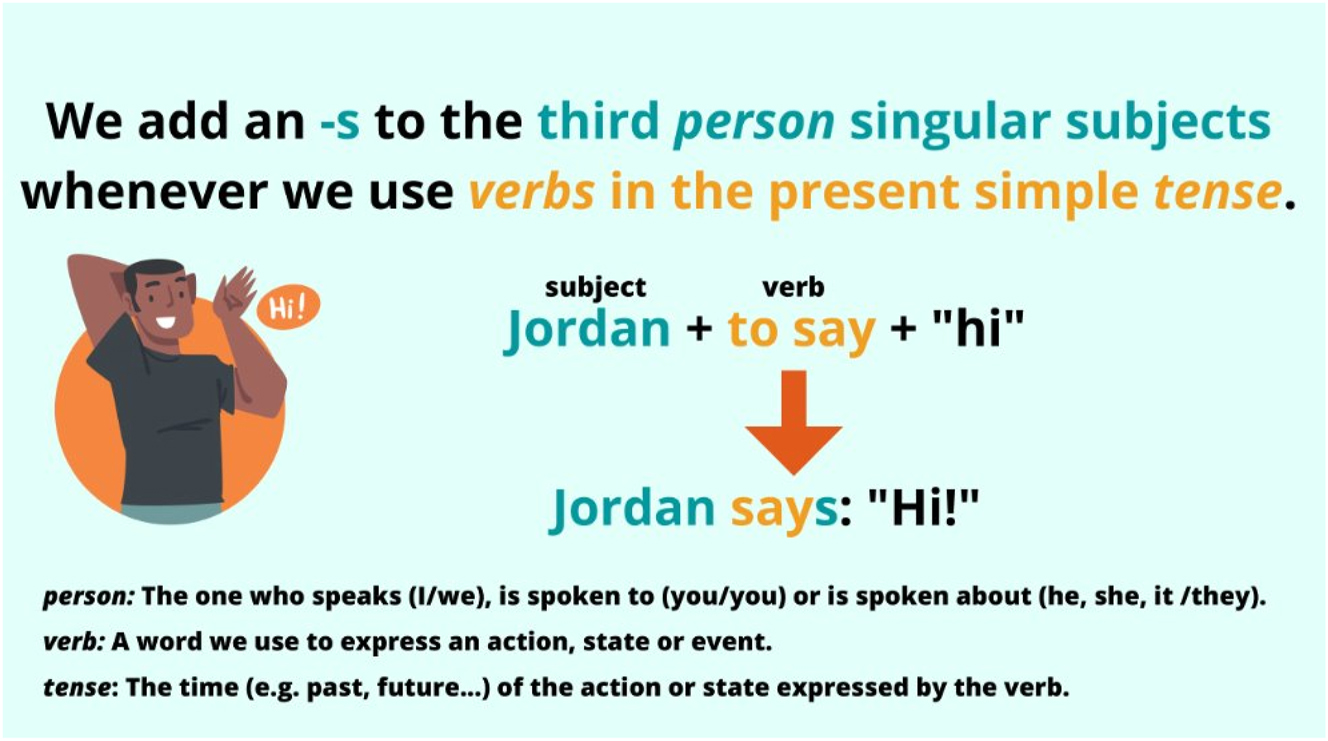

4.2.3 Metalinguistic explanations

In the present study, the researchers aimed for the ME to not only explain the mechanism behind the accurate use of the two selected TF, but also include basic metalinguistic terminology. Definitions from the Oxford English Dictionary (2022) for terms like subject, object, verb or possessive, among others, were adapted for age appropriateness and included in the slides. The ME were delivered to the experimental dyads by one of the researchers as a guided, interactive presentation of approximately 10 min per TF, which amounted to a total of 20 min of intervention time. The learners were given handouts for input redundancy and as an attempt to increase task engagement. These were collected at the end of the intervention to prevent possible exchanges of information between the participants during the length of the experiment.

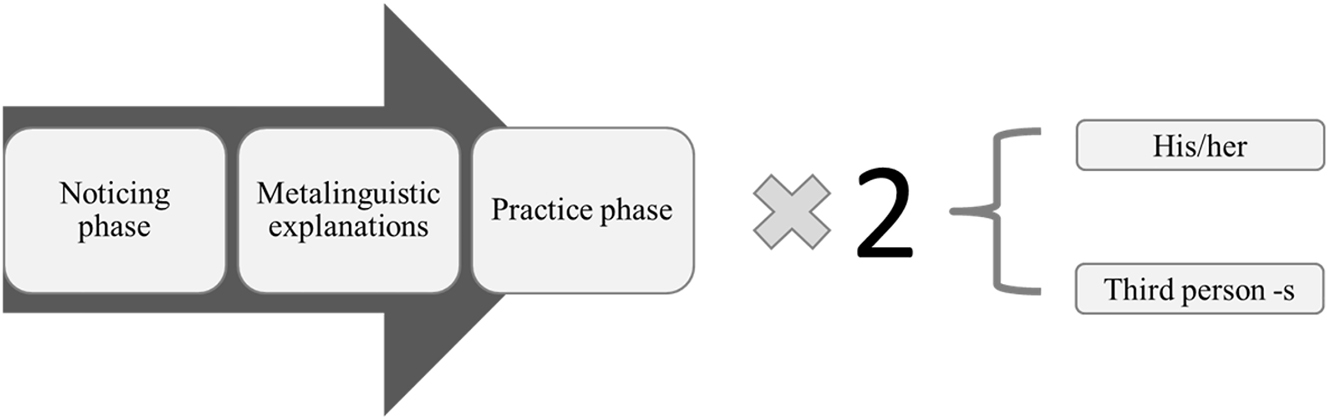

The intervention was designed following a three-step approach for every TF. First, in the form of a challenge, the participants were asked to read four example sentences that included inaccurate uses of the TFs they had to discover. At this stage, their grammaticality judgements needed to be informally explained. Second, they were shown and explained the ME (Appendix 2). For this purpose, both a computer and the aforementioned paper handout were used. The participants were allowed to ask questions during this stage so as to keep task engagement levels high. Finally, an interactive cloze test was delivered, as practice does seem to be a key factor for retention at the time of using ME (Shintani and Ellis 2013). Figure 2 illustrates the procedure.

ME three-step procedure.

4.2.4 Verbal protocol

An individual, retrospective verbal protocol was designed to ensure that every learner’s performance during the dyadic task could match their individual scores at the MA test. Since verbal protocols can constitute a thought-shaping intervention (Butler 2022; Swain 2006), they were conducted after the final MA post-test. Carried out as a short 5 min interview in Spanish, the verbal protocol encompassed three stages: a stimulated recall phase, a translation phase and a rule-elicitation phase. First, during the stimulated recall stage, the learner was shown a piece of a video in which they or their counterpart used the target feature; afterwards, they were asked an open-ended question so as to elicit the reasoning behind their correct or incorrect form choice. Whenever possible, self-repairs were used at this stage, as they were considered to constitute appropriate examples of noticing and learning behaviour. During the second stage, the students were given two short sentences in Spanish that they had to translate, each containing one of the target features. Finally, the students had to recollect the rule behind the correct use of each of the target features.

4.3 Data analysis

For the MA test, raw scores at the task were calculated and annotated on an Excel spreadsheet. Each individual test was graded according to the guidelines of the author of the test (Tellier 2013), which are available on the IRIS database (Marsden et al. 2016). As for the dictogloss task, only those events related to noticing of the TF were included in the analysis. The data consisted of 16 10 min video/audio tapes (8 tapes per phase) that were transcribed on a Word document and codified using CHILDES (MacWhinney 2000). Individual accuracy percentages during the interaction were calculated by dividing the total correct instances of use of the TF by the sum of the correct uses, incorrect uses and the clearly avoided uses in obligatory contexts of the same TF (based on Pica 1983):

Table 1 illustrates how these uses occurred during the interaction.

Codification of target feature use during the interaction.

| Correct use | Incorrect use | Avoidance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target feature -s | *ACA: Tom plays football. | *YAZ: María take pictures. | *LJM: [Tom] drawing pictures. |

| Target feature his/her | *MTA: Víctor likes his family. | *IAM: Víctor and her fathers. | *FJP: The father the Victor has a dinner in the boat. |

We operationalised the noticing events related to form during the interaction as LREs. As explained by Swain and Lapkin (1998), LREs are “any part of a dialogue in which students talk about the language they are producing, question their language use, or other – or self-correct”. For the purposes of this study, only those events related to noticing of forms were included in the analysis (Form-focused LREs, F-LREs). Likewise, even though LREs are collaborative in nature, we aimed to individualise the learners’ utterances as much as the data allowed for. To accomplish this task, both the initiator and the closer of the LRE were identified. The initiator is, then, the pupil who first notices a feature, while the closer is the learner who puts an end to the episode. An LRE could end by means of reaching a solution (correct or incorrect), by being addressed, or simply by being ignored. As seen below in F-LRE 2, both initiator and closer are sometimes the same person. In this study, we awarded a point to a student whenever they managed to solve an F-LRE correctly.

| *AAA: Victor speak French very well and … | *YAZ: with her friends? (initiator) |

| *MHE: S? [with -s?] (initiator) | *ACA: with his friends. |

| *AAA: S. [= ! nodding in agreement] | *YAZ: uhm. |

| (solver, correct) | *ACA: her no, eh? (solver, correct) |

| *YAZ: yes, yes. | |

| Example 1. F-LRE 1. Correctly solved TF -s | Example 2. F-LRE 2. Correctly solved TF his/her |

Lastly, we implemented a point system at the time of analysing the data from the verbal protocol, which came from 16 5 min audio/video tapes, one belonging to each participant. For the translation phase, one point was awarded for partially correct answers, while fully correct answers were given two points. The same scores were applied at the time of the rule elicitation phase. However, an extra point was scored every time the participant correctly used a metalinguistic term, with a maximum of three points per participant. Incorrect answers did not score any points at any of the three stages.

5 Results

As we only measured two data points in time, a paired-samples t-test sufficed to conduct a significance analysis. Likewise, given the small sample size, Hedges’g (Hedges and Olkin 1985) was the preferred calculation of effect size. However, upon visualisation of the data on R (R Core Team 2024) using the ggplot() function in the qqplot2 package (Wickham 2016), it was evident that assumptions of normality were not met for the data pertaining to RQ2 and RQ3. It was then decided to use a paired-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test as an alternative paired measures significance test. All the significance tests and calculations were carried out using the programming language R (R Core Team 2024) on the RStudio (RStudio Team 2023) software. For the Wilcoxon signed rank test, the built-in wilcox.test() function was used. Hedge’s g was calculated by hand using the formula and the incorporated calculation functions.

The first research question (RQ1) we posed asked whether ME could help L1 Spanish young EFL learners improve their scores at a MA test. As shown in Table 2, no significant differences were found between pretest and post-test mean scores for the CG (M = 48.50, SD = 10.350, p = 0.600, p > 0.05). However, there is a significant difference between pretest and post-test mean scores for the treatment group (M = 63.88, SD = 9.463, p = 0.005, p < 0.01). As Hedges’ g behaves similarly to Cohen’s d, adjusted effect sizes for SLA can be used as a reference (small, d = 0.40; medium, d = 0.70; large, d = 1; Plonsky and Oswald 2014). The effect size is, therefore, moderate.

Results for the MA test.

| d | Mean | SD | p-Value (α = 0.05) | Hedges’ g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 0.875 [95 % CI, −2.901 to 4.651] | 48.500 | 10.350 | 0.600 | 0.090 |

| TG | 16.125 [95 % CI, 6.432 to 25.817] | 63.880 | 9.463 | 0.005 | 0.809 |

The second research question (RQ2) asked whether ME concerning the two TF could help L1 Spanish young EFL learners improve their accuracy scores at the time of using them in the interaction during a dictogloss task. As for the use of the third person –s marker, the CG showed no improvements between the pre- and the post-test, as shown in Table 3. The TG, in turn, experienced a significant increase in the accurate use of the TF, which would support the usefulness of the ME at the time of scaffolding the participants’ learning process in regards to this TF. Following the aforementioned framework of reference by Plonsky and Oswald (2014), the effect size is large. The negative sign indicates that the post-test values, which were computed in the formula as Group B, are larger than those from the pretest, which were coded as Group A. As Table 4 illustrates, a similar pattern was observed in regards to the determiner possessives his and her: while the CG did not exhibit any significantly different behaviours in terms of accuracy, the TG did show a significant increase in their accuracy at the time of producing his and her during the interaction, which would again support the validity of the ME. However, the observed effect size seems to be smaller in regards to this feature (Hedge’s g = 1.19). Hedges’s g yielded medium (-s) and small (his/her) effect sizes for the control group, respectively. This is attributable to the fact that, for each of the features, accuracy scores moderately or slightly decreased from the pre-test to the post-test stage.

Results for accuracy in regards to third person –s use.

| Mean (post-test, %) | SD | p-value (α = 0.05) | Hedge’s g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 0 | 0 | 0.1814 | 0.855 |

| TG | 71.43 | 23.51205 | 0.02344 | 1.71 |

Results for accuracy in regards to his/her possessive use.

| Mean (post-test, %) | SD | p-value (α = 0.05) | Hedge’s g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | 27.62 | 36.943 | 0.2807 | 0.321 |

| TG | 55.75 | 23.51205 | 0.03603 | 1.19 |

Finally, the last research question (RQ3) asked whether ME could promote the correct resolution of F-LREs. While the TG dyads seemed to produce more F-LREs, as detailed in Table 5, Table 6 shows that there is not a clear pattern overlap between the amount of individual correct resolutions of F-LREs and scores at the retrospective verbal protocol. As for the control group, only the higher proficiency dyad managed to correctly solve any F-LREs. Save for this pair, none of the learners in the control group scored any points at the retrospective verbal protocol.

Correctly solved F-LREs by group.

| Treatment | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test |

| 5 | 13 | 3 | 2 |

Correctly solved F-LRES (CS) by child and individual scores at the verbal protocol.

| Treatment | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student ID | CS, post-test | VP score | CS, post-test | VP score |

| Pair 1 A | 3 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| Pair 1 B | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| Pair 2 A | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Pair 2 B | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Pair 3 A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pair 3 B | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Pair 4 A | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Pair 4 B | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

6 Discussion

As for RQ1, there seems to be a significant effect of the treatment, a fact that would contribute to the validity of the ME used during the intervention. This result is coherent with the findings reported by Kasprowicz et al. (2022), who could find significant evidence of increased MA in 9–11 year-old learners of German as a FL following an explicit intervention. It should be noted, though, that the improvement across proficiency levels seems to be dissimilar. For this reason, more data is needed in order to determine the extent to which students at different proficiency bands can benefit from this treatment. Also, while the effect size of the ME in regards to the scores at the MA test seems to be moderate, these results should be interpreted with caution and always within this particular context. In this regard, and even after adjusting our interpretation framework to the specificities of the field, it is worth mentioning that effect size calculations can lose some of their reliability under certain conditions such as low statistical power (Plonsky and Oswald 2014). Likewise, it should be disclosed that, as confirmed by both their English and Literacy teachers, the participants in this study had never received any kind of explicit metalinguistic instruction before in any of the three languages they used in the classroom. This is further confirmed by the fact that, while the regional curriculum does support fostering the development of intuitions about the different mechanisms of language in the class, no formal approaches to morphosyntax are supposed to be carried out before Year 6 (Gobierno de Aragón 2016, 2022). For this reason, we speculate that the inclusion of definitions and general explanations about metalinguistic terminology in the ME was a part that largely accounted for the size of the effect. In this regard, it would be worth conducting this intervention with students age 11 and older to see if the effect sizes remain the same. In the same vein, the fact that the PBL approach, which heavily relied on unfocused activities, was followed at this school makes it all the more likely that the students benefitted from the intervention to a larger extent than those who follow a more traditional approach to EFL learning. Moreover, the intensity of the one-on-one treatment and the proximity in time to the post-test could also distort the actual extent of the effect; a delayed post-test should be carried out in future experiments in order to account for time effects. In any case, even in the light of all of the aforementioned cautions in relation to the measurement of the effect size, there seems to be a clear effect of the ME on the learners’ MA, which consolidates our initial working assumption. This is further confirmed by the results of the verbal protocol.

The same precautions in regards to effect sizes would apply to RQ2. Again, a significant effect of treatment was found, which would support the validity of the ME used in this study. In this case, our results partly contradict those of Serrano (2011): in her study, even though the differences between the groups were not significant under any conditions, the rule-based instruction group did show small gains that approached significance. Our results do not reflect the findings of Gorman and Ellis (2019) either, as they were not able to find significant effects for their ME-based intervention. The authors of the study discuss that there is a possibility that younger students are not able to make use of their metalinguistic knowledge at the time of simultaneously dealing with a writing task. However, it should be noted as well that, as acknowledged by the authors themselves, Gorman and Ellis chose the Present Perfect Tense as their TF, which arguably poses a greater deal of difficulty for younger learners than our TFs of choice. In any case, it is, once again, advisable to attend to the context in which our results were observed at the time of interpreting the scope of our findings. As stated by the participants’ English teacher, the pupils had never purposefully worked on any of the two TF before: while they had been used in the classroom, no form-focused instruction had ever been delivered in this regard. For this reason, there was a reasonable expectation to observe moderate-to-large effect sizes in this regard. Respecting the TG, the presence of two outliers should be noted as well: while one pupil exhibited a very passive communication pattern and did not produce any TF at all, another participant showed an abnormally high level of proficiency for her age and level of instruction. Upon review of the background test, it was found that the latter participant received 3 h of one-on-one EFL tutoring per week. In the light of this phenomenon, it would be advisable to control for this variable in future studies. As for the CG, a surprising pattern emerged, in which the participants did not only use the TF inaccurately but hardly produced them at all during the post-test phase. After an exhaustive examination of the transcripts, it was evident to us that the post-test results seem to be heavily influenced by the design of the materials for the dictogloss task. For additional context, it should be disclosed that the post-test text versed about two siblings who went on a holiday. Apparently, the CG did not notice the third person singular target features and, thus, treated the siblings as a joint entity: they tended to use the third person plural they to describe the setting. Once again, the extremely few target items they used during the interaction, if any, were non-targetlike, but we cannot ascertain for sure whether this would have been the case had they chosen the third person singular form. Likewise, the design of both pre-test and post-test texts also allowed for TF avoidance in regards to –s, as we noticed that many learners used the present continuous form instead of the present simple at some point. We hypothesise that two reasons might be behind this pattern. One of them is the reasonable expectation of using the present continuous tense at the time of describing something that is happening in front of us, especially when commonly used pedagogical approaches teach children to do so. Likewise, we speculate that the present continuous tense seemed to be easier to use for these participants, given that they were likely used to employing it often and most of them seemed to have mastered the accurate use of to be (Lázaro-Ibarrola and García Mayo 2006). For this reason, it is advisable that future dictogloss experiments make a careful, global assessment of the materials in regards to the TF they seek to focus on, as it may be crucial for negotiation of meaning and output production processes.

In regards to RQ3, a qualitative assessment of the data shows that the TG did produce more correctly solved F-LREs during the post-test phase, a fact that would again add validity to the metalinguistic explanations as a treatment. However, considering the reduced sample size, these results are tentative and should be interpreted as such. The CG dyads did produce F-LREs, but none of them was resolved correctly. As explained above, the stark contrast in the results between both groups could be attributable to the fact that most of these pupils had never received any kind of form-focused instruction on the two TF before, as well as the intensity of the treatment and the proximity in time to the post-test. The verbal protocol could not adequately explain the differences between individuals at the time of assessing the number of correct contributions they had made during the collaborative interaction. This seems to be the case, for instance, of learner B in the Pair 2 of the CG, who scored 8 points at the VP but did not solve any F-LREs during the post-test dictogloss. As discussed by Roehr (2006) in a study that assessed adult learners’ MA with verbal reports, even though metalinguistic knowledge often co-occurs with accurate linguistic production, “increasing levels of complexity of use of metalinguistic knowledge do not appear to be necessarily associated with greater consistency of performance” (Roehr 2006: 194). This also leads us to consider that some learners might need more opportunities to produce output; in this regard, some adjustments to the task could be made in order to accommodate students’ needs as much as the experimental setting allows to. Researchers should carefully consider how time constraints, interaction patterns, interaction profiles, and affective factors such as anxiety, shyness, and willingness to communicate are going interfere with the participants’ performance at the time of the interaction.

7 Conclusions and pedagogical implications

In this article we intended to explore the effect of a ME-based intervention on an under-researched population, as well as to collect some evidence on the relationship between ME, MA and grammatical accuracy in regards to two knowingly problematic TF. While our main aim for this experiment was to test and refine the experimental procedures we intend to use in a further large-scale study on the topic, we consider that some valuable exploratory findings can be derived from these results. We intend to contribute to the area of research by offering these preliminary conclusions and extending certain methodological recommendations so as to help other researchers improve similar experimental designs in the future.

In the light of the results we have observed after this intervention, it is apparent to us that MA is a trainable ability that seems to increase with an active and engaging exposure to ME. Likewise, the use of targeted ME in the classroom appears to be associated with a positive effect in terms of accuracy at the time of using two TF during an oral interaction task, as well as promotes the correct resolution of F-LREs in regards to the two features the intervention targets. The observed results also imply that metalinguistic terminology cannot only be successfully taught to younger EFL learners if done in an age-appropriate manner, but its use is also likely tied to an increase in YL learners’ MA as reflected by scores on a dedicated test. Overall, our results confirm our working assumption that ME can have a positive impact on YL’s metalinguistic knowledge, MA, and accuracy on the TF associated to the ME intervention. In this regard, we consider that our findings support a weak-interface stance, as the students immediately showed positive results after a short intervention that promoted reflection on language (i.e. directed attention to forms). As internalisation of explicit knowledge is supposed to take place with extended practice over time, we do not believe that our results can solely be attributed to a mere automatisation of declarative knowledge, but rather consider that form-focused instruction helped the students notice the gaps in their knowledge.

ME seem, then, to constitute a suitable form of direct, explicit written corrective feedback for YL. ME-based approaches to form-focused instruction seem to be a powerful tool to foster explicit learning and boost accuracy in YLs, especially in the case of those who are exposed to a target feature for the first time. Therefore, ME could constitute a valuable resource in the case of meaning-oriented EFL classrooms, and particularly so in heavily content-centred PBL-based approaches to teaching, where learners’ accuracy might be hindered at times if form-focused instruction is not deemed a priority. In sum, ME appear to be a cost-effective, intensive and focused instrument to direct the learner’s attentional resources to the TFs of choice.

8 Limitations

The present pilot study contains major limitations that should be taken into account at the time of interpreting our observed results. First, even though the extent of the effect seems to be large, the size of the sample involved inevitably leads to low statistical power. Thus, as a novel instrument, the ME need to be used in larger contexts so that their validity and reliability can be accurately assessed. Likewise, the unique characteristics of the sample, the school setting and the instructional approach also pose a challenge at the time of generalising the results. For this reason, we aim for the experiment to be replicated in different schools and contexts. An open dialogue between researchers and practitioners is encouraged so that both parties are made aware of the actual gap between the curriculum and the classroom practices followed at the experimental setting. Secondly, even though the task was assumed to be suitable for Year 5 students, lower proficiency students at this stage often relied on their L1, produced very limited written output and verbalised having difficulties at the time of accurately completing the task. Thus, it should be taken into account that CLIL students of languages other than English are likely to have a lower level of proficiency compared to their English CLIL counterparts in the same year. Also, the dictogloss tasks needed to be timed due to schedule constraints. Likewise, no delayed post-tests were carried out, nor were additional rounds of treatment. The effects of time and repetition should be assessed in further experiments. In the same vein, any texts conceived for this sort of dictogloss task should aim to use the present simple tense in straightforward terms, using temporal markers such as frequency adverbs in order to better elicit the TF. Also, the texts should aim to use clear third-person singular target items and better differentiate them from fillers. Lastly, it is known that affective factors such as anxiety and willingness to communicate can have a sizable impact on learners’ performance at a collaborative task. In the same vein, both metalinguistic explanations and the dictogloss task are very demanding tasks in terms of working memory capacity, another factor that could have had an effect on the learners’ performance at the task and is worth exploring in the future.

Funding source: Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación

Award Identifier / Grant number: PID2020-113630-GB-I00

Acknowledgments

We can only express our gratitude to Sara, Vanesa, María and the staff at the school where the data were collected, who kindly shared their time with us and made us feel a part of their community. Of course, this article would never have been possible without the time and effort the students at 5.º A poured into our experiment. Likewise, we would like to thank Karen Roehr-Brackin for her helpful insight in regard to verbal protocols.

-

Research ethics: The project was approved and supervised by the Ethical Committee at the University of the Basque Country. Parental informed consent was given prior to the collection of the data.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This experiment was made possible by grant PRE2021-097645 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, as a part of the project Balancing interaction and L2 grammar learning by children in an EFL context (INGREFL, PID2020-113630-GB-I00).

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author (paloma.delgado@ehu.eus).

Appendix 1: Dictogloss student sheet

Appendix 2: Metalinguistic explanations (sample slide)

References

Alegría de la Colina, Ana & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2007. Attention to form across collaborative tasks by low-proficiency learners in an EFL setting. In María Pilar García Mayo (ed.), Investigating tasks in formal language learning, 91–116. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.27939675.10Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, John Robert. 1985. Cognitive psychology and its implications, 2nd edn. New York: Freeman.Search in Google Scholar

Basterrechea, María & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2013. Language-related episodes during collaborative tasks: A comparison of CLIL and EFL learners. In Kim McDonough & Alison Mackey (eds.), Second language interaction in diverse educational contexts, 25–43. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/lllt.34.05ch2Search in Google Scholar

Basterrechea, María & Michael J. Leeser. 2019. Language-related episodes and learner proficiency during collaborative dialogue in CLIL. Language Awareness 28(2). 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2019.1606229.Search in Google Scholar

Bialystok, Ellen. 2001. Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511605963Search in Google Scholar

Birdsong, David. 1989. Metalinguistic performance and interlinguistic competence. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-74124-1Search in Google Scholar

Bitchener, John & Dana Ferris. 2012. Written corrective feedback in second language acquisition and writing. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203832400Search in Google Scholar

Bozorgian, Hossein & Ali Yazdani. 2021. Direct written corrective feedback with metalinguistic explanation: Investigating language analytic ability. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 9(1). 65–85. https://doi.org/10.30466/ijltr.2021.120976.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, Yuko Goto. 2022. Verbal reports as a window for understanding mental processes among young learners. In Yuko Goto Butler & Becky Huang (eds.), Research methods for understanding child second language development, 49–63. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780367815783-5Search in Google Scholar

Calzada, Asier & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2020a. Child EFL grammar learning through a collaborative writing task. In Wataru Suzuki & Naomi Storch (eds.), Languaging in language learning and teaching. A collection of empirical studies, 19–40. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/lllt.55.01calSearch in Google Scholar

Calzada, Asier & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2020b. Child EFL learners’ attitudes towards a collaborative writing task: An exploratory study. Language Teaching for Young Learners 2(1). 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.19008.cal.Search in Google Scholar

Calzada, Asier & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2021. Effects of proficiency and collaborative work on child EFL individual dictogloss writing. Language Teaching for Young Learners 3(2). 246–274. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.20003.cal.Search in Google Scholar

Cambridge Assessment English. 2018. Young learners sample papers 2018. Flyers A2. Cambridge: Cambridge Assessment English. https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/Images/young-learners-sample-papers-2018-vol1.pdf (accessed 5 June 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Council of Europe. 2001. Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97 (accessed 5 June 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Coyle, Do. 2007. Content and language integrated learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10(5). 543–562. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb459.0.Search in Google Scholar

D’Angelo, Francesca & Antonella Sorace. 2022. The additive effect of metalinguistic awareness in third or additional language acquisition. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(10). 3551–3567. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2022.2064710.Search in Google Scholar

DeKeyser, Robert M. 2003. Implicit and explicit learning. In Catherine Doughty & Michael H. Long (eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition, 313–348. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470756492.ch11Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Rod. 1997. SLA research and language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2002. Reflections on frequency effects in language processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 24(2). 297–340. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263102002140.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2005. At the interface: Dynamic interaction of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 27(2). 305–352. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226310505014X.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Rod. 2009. Measuring implicit and explicit knowledge on a second language. In Rod Ellis, Shawn Loewen, Catherine Elder, Rosemary Erlam, Jennifer Philp & Hayo Reinders (eds.), Implicit and explicit knowledge in second language learning, testing and teaching, 31–64. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.27195491.7Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Rod. 2020. Task-based language teaching for beginner-level young learners. Language Teaching for Young Learners 2(1). 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.19005.ell.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. & Diane Larsen-Freeman. 2006. Salience, cognition, language complexity, and complex adaptive systems. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 38(2). 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226311600005X.Search in Google Scholar

Fotos, Sandra. 1994. Integrating grammar instruction and communicative language use through grammar consciousness-raising tasks. TESOL Quarterly 28(2). 323–351. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587436.Search in Google Scholar

Fotos, Sandra & Rod Ellis. 1991. Communicating about grammar: A task-based approach. TESOL Quarterly 25(4). 605–628. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587079.Search in Google Scholar

Gobierno de Aragón. 2016. Resolución de 12 de abril de 2016, del Director General de Planificación y Formación Profesional. [Resolution of 12 April, 2016, by the General Director of Planning and Vocational Training]. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.Search in Google Scholar

Gobierno de Aragón. 2022. Orden ECD/1112/2022, de 18 de julio [Order ECD/1112/2022, of 18 July]. Boletín Oficial de Aragón [Official Bulletin of Aragon] 145. 25614-26207. Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón.Search in Google Scholar

Goldshneider, Jennifer M. & Robert DeKeyser. 2005. Explaining the ‘natural order of L2 morpheme acquisition’ in English: A meta-analysis of multiple determinants. Language Learning 55(1 Suppl). 27–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0023-8333.2005.00295.x.Search in Google Scholar

Gombert, Jean Emile. 1992. Metalinguistic development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gorman, Mary & Rod Ellis. 2019. The relative effects of metalinguistic explanation and direct written corrective feedback on children’s grammatical accuracy in new writing. Language Teaching for Young Learners 1(1). 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.00005.gor.Search in Google Scholar

Haugen, Kaja, Cecile Hamnes Carlsen & Christine Möller-Omrani. 2024. Developing an MLA-test for young learners: Insights from measurement theory and language testing. Language Awareness. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2024.2385762.Search in Google Scholar

Hedges, Larry V. & Ingram Olkin. 1985. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Becky. 2015. A synthesis of empirical research on the linguistic outcomes of early foreign language instruction. International Journal of Multilingualism 13. 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2015.1066792.Search in Google Scholar

Imaz Agirre, Ainara & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2013. Gender agreement in L3 English by Basque/Spanish bilinguals. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3(4). 415–447. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.3.4.02ima.Search in Google Scholar

Kasprowicz, Rowena, Karen Roehr-Brackin & Gee Macrory. 2022. Metalinguistic awareness in early foreign language learning. In Kevin McManus & Monika Schmid (eds.), How special are early birds? Foreign language teaching and learning, 93–118. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen D. 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.Search in Google Scholar

Larson-Hall, Jennifer. 2008. Weighing the benefits of studying a foreign language at a younger starting age in a minimal input situation. Second Language Research 24. 35–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658307082981.Search in Google Scholar

Lasagabaster Herrarte, David. 1998. Metalinguistic awareness and the learning of English as an L3. Atlantis 20(2). 69–79.Search in Google Scholar

Lázaro-Ibarrola, Amparo. 2023. Child L2 writers: A room of their own. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tilar.32Search in Google Scholar

Lázaro Ibarrola, Amparo & María del Pilar García Mayo. 2006. Is forma euskara-gaztelera haur elebidunen ingelesezko tarteko hizkuntzan [Is in the English interlanguage of Basque-Spanish bilingual children]. In Jasone Cenoz & David Lasagabaster (eds.), Hizkuntzak ikasten eta erabiltzen [Learning and using languages], 221–242. Leioa: Universidad del País Vasco.Search in Google Scholar

Long, Michael H. 1983. Native speaker/non-native speaker conversation and the negotiation of comprehensible input. Applied Linguistics 4(2). 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/4.2.126.Search in Google Scholar

Long, Michael H. 1996. The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In William C. Ritchie & Tej K. Bhatia (eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition, 144–150. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.10.1016/B978-012589042-7/50015-3Search in Google Scholar

MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES project: The database, vol. 2. London: Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

Manchón, Rosa María. 2011. Learning-to-write and writing-to-learn in an additional language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/lllt.31Search in Google Scholar

Marsden, Emma, Alison Mackey & Luke Plonsky. 2016. The IRIS repository: Advancing research practice and methodology. In Alison Mackey & Emma Marsden (eds.), Advancing methodology and practice: The IRIS repository of instruments for research into second languages, 1–21. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

McLaughlin, Barry. 1990. “Conscious” versus “unconscious” learning. TESOL Quarterly 24(4). 617–634. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587111.Search in Google Scholar

Núñez Delgado, María Pilar & Maria Antonetta Pinto. 2015. THAM-2. Test de habilidades metalingüísticas n.º 2 (9–12 años). Roma: Sapienza Università Editrice.Search in Google Scholar

Oliver, Rhonda. 1998. Negotiation of meaning in child interactions. The Modern Language Journal 82(3). 372–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01215.x.Search in Google Scholar

Oxford University Press. 2022. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Palacios-Hidalgo, Francisco Javier, María Elena Gómez-Parra & Cristina A. Huertas-Abril. 2022. Spanish bilingual and language education: A historical view of language policies from EFL to CLIL. Policy Futures in Education 20(8). 877–892. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103211065610.Search in Google Scholar

Pica, Teresa. 1983. Methods of morpheme quantification: Their effect on the interpretation of second language data. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 6(1). 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100000309.10.1017/S0272263100000309Search in Google Scholar

Pinter, Annamaria. 2012. Teaching young learners. In Anne Burns & Jack C. Richards (eds.), The Cambridge guide to pedagogy and practice in second language teaching, 103–111. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009024778.014Search in Google Scholar

Plonsky, Luke & Frederick L. Oswald. 2014. How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning 64(4). 878–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12079.Search in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2024. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.Search in Google Scholar

Roehr, Karen. 2006. Metalinguistic knowledge in L2 task performance: A verbal protocol analysis. Language Awareness 15(3). 180–198. https://doi.org/10.2167/la403.0.Search in Google Scholar

Roehr-Brackin, Karen. 2018. Metalinguistic awareness and second language acquisition. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315661001Search in Google Scholar

Roehr-Brackin, Karen. 2024. Measuring children’s metalinguistic awareness. Language Teaching. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444824000016.Search in Google Scholar

Roehr-Brackin, Karen & Angela Tellier. 2019. The role of language-analytic ability in children’s instructed second language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41(5). 1111–1131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263119000214.Search in Google Scholar

Roothooft, Hanne, Amparo Lázaro-Ibarrola & Bram Bulté. 2022. Task repetition and corrective feedback via models and direct corrections among young EFL writers: Draft quality and task motivation. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221082041.Search in Google Scholar

RStudio Team. 2023. RStudio: Integrated development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio. http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed 5 June 2024).Search in Google Scholar

San Isidro, Xabier & Ángel Huerga. 2023. Paving the way for CLIL in pre-primary education: The case of Madrid. In Ana Otto & Beatriz Cortina-Pérez (eds.), Handbook of CLIL in pre-primary education, 117–132. Berlin: Springer.10.1007/978-3-031-04768-8_8Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, Richard & Sylvia Frota. 1986. Developing basic conversational ability in a second language: A case study of an adult learner of Portuguese. In Richard Day (ed.), Talking to learn: Conversation in second language acquisition, 237–326. New York: Newbury House.Search in Google Scholar

Serrano, Raquel. 2011. From metalinguistic instruction to metalinguistic knowledge, and from metalinguistic knowledge to performance in error correction and oral production tasks. Language Awareness 20(1). 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2010.529911.Search in Google Scholar

Shintani, Natsuko, Scott Aubrey & Mark Donnellan. 2016. The effects of pre-task and post-task metalinguistic explanations on accuracy in second language writing. TESOL Quarterly 50(4). 945–954. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.323.Search in Google Scholar

Shintani, Natsuko & Rod Ellis. 2013. The comparative effect of direct written corrective feedback and metalinguistic explanation on learners’ explicit and implicit knowledge of the English indefinite article. Journal of Second Language Writing 22(3). 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2013.03.011.Search in Google Scholar

Storch, Neomy. 2016. Collaborative writing. In Rosa María Manchón & Paul Kei Matsuda (eds.), Handbook of second and foreign language writing, 387–406. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9781614511335-021Search in Google Scholar

Storch, Neomy & Ali Aldosari. 2013. Pairing learners in pair work activity. Language Teaching Research 17(1). 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168812457530.Search in Google Scholar

Swain, Merrill. 1985. Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In Susan M. Gass & Carolyn G. Madden (eds.), Input in second language acquisition, 165–179. New York: Newbury House.Search in Google Scholar

Swain, Merrill. 2006. What does it mean for research to use speaking as a data collection tool? In Micheline Chalhoub-Deville, Carol A. Chapelle & Patricia Duff (eds.), Inference and generalizability in applied linguistics: Multiple perspectives, 97–113. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Swain, Merrill & Sharon Lapkin. 1998. Interaction and second language learning: Two adolescent French immersion students working together. The Modern Language Journal 82(3). 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb01209.x.Search in Google Scholar

Tellier, Angela. 2013. Developing a measure of metalinguistic awareness for children aged 8–11. In Karen Roehr & Adela Gánem-Gutiérrez (eds.), The metalinguistic dimension in instructed second language learning, 15–43. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Vraciu, Alexandra & Elisabet Pladevall-Ballester. 2022. L1 use in peer interaction: Exploring time and proficiency pairing effects in primary school EFL. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25(4). 1433–1450. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1767029.Search in Google Scholar

Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wajnryb, Ruth. 1990. Grammar dictation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wei, Li. 2022. Preface. In Kevin McManus & Monika S. Schmid (eds.), How special are early birds? Foreign language teaching and learning, iii–iv. Berlin: Language Science Press.Search in Google Scholar

Wickham, Hadley. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Young L2 learners in diverse instructional contexts

- Research Articles

- Impact of post-task explicit instruction on the interaction among child EFL learners in online task-based reading lessons

- Can we train young EFL learners to ‘notice the gap’? Exploring the relationship between metalinguistic awareness, grammar learning and the use of metalinguistic explanations in a dictogloss task

- Exploring self-regulated learning behaviours of young second language learners during group work

- Developmental trajectories of discourse features by age and learning environment

- Implementing an oral task in an EFL classroom with low proficient learners: a micro-evaluation

- Exploring teacher-student interaction in task and non-task sequences

- Children learning Mongolian as an additional language through the implementation of a task-based approach

- “Black children are gifted at learning languages – that’s why I could do TBLT”: inclusive Blackness as a pathway for TBLT innovation

- Regular Articles

- Defining competencies for training non-native Korean speaking teachers: a Q methodology approach

- A cross-modal analysis of lexical sophistication: EFL and ESL learners in written and spoken production

- Using sentence processing speed and automaticity to predict L2 performance in the productive and receptive tasks

- Distance-invoked difficulty as a trigger for errors in Chinese and Japanese EFL learners’ English writings

- Exploring Chinese university English writing teachers’ emotions in providing feedback on student writing

- General auditory processing, Mandarin L1 prosodic and phonological awareness, and English L2 word learning

- Why is L2 pragmatics still a neglected area in EFL teaching? Uncovered stories from Vietnamese EFL teachers

- Validation of metacognitive knowledge in vocabulary learning and its predictive effects on incidental vocabulary learning from reading

- Anxiety and enjoyment in oral presentations: a mixed-method study into Chinese EFL learners’ oral presentation performance

- The influence of language contact and ethnic identification on Chinese as a second language learners’ oral proficiency

- An idiodynamic study of the interconnectedness between cognitive and affective components underlying L2 willingness to communicate

- “I usually just rely on my intuition and go from there.” pedagogical rules and metalinguistic awareness of pre-service EFL teachers

- Development and validation of Questionnaire for Self-regulated Learning Writing Strategies (QSRLWS) for EFL learners

- Language transfer in tense acquisition: new evidence from English learning Chinese adolescents

- A systematic review of English-as-a-foreign-language vocabulary learning activities for primary school students

- Using automated indices of cohesion to explore the growth of cohesive features in L2 writing

- The impact of text-audio synchronized enhancement on collocation learning from reading-while-listening: an extended replication of Jung and Lee (2023)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Young L2 learners in diverse instructional contexts

- Research Articles

- Impact of post-task explicit instruction on the interaction among child EFL learners in online task-based reading lessons

- Can we train young EFL learners to ‘notice the gap’? Exploring the relationship between metalinguistic awareness, grammar learning and the use of metalinguistic explanations in a dictogloss task

- Exploring self-regulated learning behaviours of young second language learners during group work

- Developmental trajectories of discourse features by age and learning environment

- Implementing an oral task in an EFL classroom with low proficient learners: a micro-evaluation

- Exploring teacher-student interaction in task and non-task sequences

- Children learning Mongolian as an additional language through the implementation of a task-based approach

- “Black children are gifted at learning languages – that’s why I could do TBLT”: inclusive Blackness as a pathway for TBLT innovation

- Regular Articles

- Defining competencies for training non-native Korean speaking teachers: a Q methodology approach

- A cross-modal analysis of lexical sophistication: EFL and ESL learners in written and spoken production

- Using sentence processing speed and automaticity to predict L2 performance in the productive and receptive tasks

- Distance-invoked difficulty as a trigger for errors in Chinese and Japanese EFL learners’ English writings

- Exploring Chinese university English writing teachers’ emotions in providing feedback on student writing

- General auditory processing, Mandarin L1 prosodic and phonological awareness, and English L2 word learning

- Why is L2 pragmatics still a neglected area in EFL teaching? Uncovered stories from Vietnamese EFL teachers

- Validation of metacognitive knowledge in vocabulary learning and its predictive effects on incidental vocabulary learning from reading

- Anxiety and enjoyment in oral presentations: a mixed-method study into Chinese EFL learners’ oral presentation performance

- The influence of language contact and ethnic identification on Chinese as a second language learners’ oral proficiency

- An idiodynamic study of the interconnectedness between cognitive and affective components underlying L2 willingness to communicate

- “I usually just rely on my intuition and go from there.” pedagogical rules and metalinguistic awareness of pre-service EFL teachers

- Development and validation of Questionnaire for Self-regulated Learning Writing Strategies (QSRLWS) for EFL learners

- Language transfer in tense acquisition: new evidence from English learning Chinese adolescents

- A systematic review of English-as-a-foreign-language vocabulary learning activities for primary school students

- Using automated indices of cohesion to explore the growth of cohesive features in L2 writing

- The impact of text-audio synchronized enhancement on collocation learning from reading-while-listening: an extended replication of Jung and Lee (2023)