Abstract

Non-Formal learning environments are crucial in science education, yet chemistry remains an underrepresented discipline. This scoping review examines non-formal chemistry learning literature from the past decade. A systematic search and triage process yielded 34 relevant studies. Quantitative analysis revealed that non-formal chemistry activities predominantly take the form of workshops, and tabletop experiments, valued for their hands-on engagement. Science shows, while less interactive, also feature prominently due to their broad appeal. Conversely, exhibits, fairs, TV and YouTube are less documented, likely reflecting resource constraints and implementation challenges. Evaluation practices varied, often emphasizing content knowledge rather than broader goals such as fostering interest or positive attitudes toward chemistry. Two key themes were constructed from our analysis of the literature. Firstly, underrepresented groups – such as individuals from low socio-economic backgrounds or with disabilities – face significant barriers to participation. Secondly, there is a cyclic relationship between affective-motivational factors, such as enjoyment, interest, attitude and motivation, and engagement with non-formal chemistry learning. This highlights the need for non-formal learning activities to effectively reach individuals with low initial interest, particularly from underrepresented demographics. This scoping review calls for more robust, inclusive, and comprehensive research to address existing gaps and maximize the impact of non-formal chemistry learning.

1 Introduction

1.1 Formal, informal and non-formal learning

Given the pervasive role of science in society, it is essential for the public to possess a foundational understanding to make informed decisions in their daily lives. 1 As such, fostering scientific literacy is of critical importance. 2 Despite this, numerous studies and policy reports highlight that science education, particularly in chemistry, physics, and technology-related subjects, is often met with low enthusiasm from students. 3 , 4 , 5 A common concern raised in this context is that many students perceive science education as lacking in both interest and relevance. 6 , 7

In recent decades, science education has increasingly moved beyond the confines of the traditional classroom, with a growing emphasis on non-formal and informal education. 8 , 9 Individuals can encounter and learn science in settings such as museums, after-school programs, libraries, and media platforms including television and YouTube. 10 These environments have been shown to be good at increasing public interest and enthusiasm for science. 11

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, in the USA, identified six goals that informal science (or non-formal) learning should include in relation to those participating: to experience excitement to learn; to use concepts related to science; to explore the world around them; to reflect; to participate with others; and, to develop an identity as a science learner. 12 They then established a framework for measing the effectiveness of informal (or non-formal) science learning, which contained five elements: set goals; identify and familiarise with the resources; design the activity and how it will be evaluated; deliver the activity; and assess, reflect and follow up. The framework is simple and flexible so that it can be used for a wide range of activities.

There have been calls to strengthen non-formal and informal science education sectors and enhance their integration with formal school-based education. 13 , 14 , 15 However, there is some confusion in the literature and amongst practitioners as to the difference between formal learning, informal learning and non-formal learning.

Coombs and Ahmed define formal education as being “the institutionalized, chronologically graded and hierarchically structured… system, spanning lower primary school and the upper reaches of the university”. 16 Rogers provides an expansion of this definition stating that formal learning has structured learning objectives and which may lead to a certification or qualification. 17 In comparison to other types of learning, formal learning has well established evaluation methods to provide feedback to the learners. 18

Non-formal education is defined by Coombs and Ahmed as “any organized, systematic, educational activity carried on outside the framework of the formal system to provide selected types of learning to particular subgroups in the population, adults as well as children”. 16 It is intentionally designed and organized around specific learning objectives. 19 , 20 While it occurs outwith compulsory education, 21 it can happen in a wide range of settings, including within school buildings. 20

Coombs and Ahmed define informal learning as “the lifelong process by which every person acquires and accumulates knowledge, skills, attitudes and insights from daily experiences and exposure to the environment”. 16 Informal learning is undertaken voluntarily 14 and is not formally structured or directed by external figures such as parents, teachers, or institutions. 22 , 23 It is estimated that 70–90 % of all learning is informal, with 95 % of our lifetime spent outside a traditional classroom. 24 , 25

Despite these definitions, the distinction between formal education and non-formal/informal education can be challenging. 14 Affeldt et al. suggest that whilst it might be tempting to label all learning experiences outwith a school campus to be informal or non-formal, these could still be part of a compulsory learning experience, and therefore formal learning. 26 Similarly, Garner et al. suggest that non-mandatory courses provided within school settings could be formal learning despite not being compulsory and not necessarily being structured by a specific curriculum, features that are aligned with non-formal or informal learning. 14

Perhaps even more challenging is the distinction between informal and non-formal learning. Coll et al. identify that although both terms have been well-defined they are often used interchangeably. 27 Further, Affeldt et al. argue that both terms are used indiscriminately for any learning experience taking place outside of school. 26 For example, the Wellcome Trust appear to define formal and informal learning as mutually exclusive, without specifically defining non-formal learning. 28 Indeed, their definition of informal learning as referring to “activities taking place outside the formal education system”, and also acknowledging the existence of informal science practitioners e.g. museums and universities, suggests that their definition of informal learning might be better aligned with Coomb’s and Ahmed’s non-formal learning.

Most recently, in their literature review, Johnson and Majewska also acknowledged the challenges of defining formal, informal and non-formal learning, in particular the challenge in deconvoluting the latter two terms. However, they go on to provide a comprehensive and clear set of characteristics that can be used to assist in defining these terms (Table 1). 29

Similarities and differences between formal, non-formal and informal learning. adapted from Johnson and Majewska. 29

| Formal learning | Non-formal learning | Informal learning |

|---|---|---|

| Learning is structured | Learning may be structured | Learning is not structured |

| Learning promoted by directed teaching behaviours | Learning is promoted by indirect teaching behaviours | |

| Learning recognised and intended by educator and learner | Learning recognised and intended by learner | Learning may not be recognised and intended by learner |

| Motivation is extrinsic to learner | Motivation is intrinsic by learner | |

| Learning takes place in educational institutions | Learning may take place in educational institutions | Learning takes place anywhere |

| Learning is mandated | Learning is voluntary | |

| Learning may be measured by qualifications | Learning not measured through qualifications | |

| Learning focuses on factual knowledge | Learning focuses on procedures and factual knowledge | |

| Learning has cognitive emphasis | Learning has cognitive, emotional, social and behavioural emphasis | |

| Curriculum is written down | Curriculum may be written down | Curriculum is not written down |

| Learning process focuses on developing specific knowledge and skills | Learning process focuses on the learner and their needs | |

| Learning follows formal curricula | Learning may complement formal curricula | |

| Learning may not be linked to socialisation | Learning is often linked to socialisation | |

For the remainder of this scoping review, we will use Johnson’s and Majewska’s 29 characteristics to distinguish between formal, non-formal and informal education.

1.2 Non-formal learning in chemistry

It is critical for society that the public have a basic understanding of chemistry, due to its importance in health, environmental sustainability and technological innovation. 30 Despite this, numerous scientists and educators have expressed concern about what they perceive as increasing ‘chemophobia’ – or at the very least, a prevailing negative perception of chemistry among the public. 31 , 32 , 33 However, the Royal Society of Chemistry reports that while people understood the positive contribution that chemistry has on society, they overall felt neutral towards the subject. 34 They suggested that this neutrality is indicative of people not feeling informed or confident in the subject. Brown et al. and Anderson et al. supported this, suggesting that society does not feel confident in their chemistry ability or may be uninformed with regards to common, everyday chemistry. 25 , 35 These challenges may stem from formal education, as highlighted by the 2018 National Science and Engineering Indicators, which reported that a significant number of students receive limited exposure to chemistry in school – and nearly one in four U.S. students do not take any chemistry courses during high school. 36

If formal chemistry education alone is not sufficient, then perhaps non-formal chemistry education can play a supporting role. However, despite the importance of non-formal learning, in 2011, the US National Research Council previously found that chemistry was not well-represented within informal learning environments. 37 This is aligned with an earlier report, in 1996, where the Association of Science and Technology Centres (ASTC) discovered that 28 % of science museums in North America reported no chemistry activities in their museums and less than a third of the science centres had no chemistry exhibits Somewhat more recent reviews also suggest that chemistry is less represented in non-formal education environments than other common science topics such as biology or physics. 37 , 38 , 39

The lack of chemistry representation in non-formal learning environments has been attributed to fears over safety and cost. 12 Silbermann et al. suggest that if a chemistry activity involves chemicals, they have to be frequently monitored and may raise potential safety issues. 38 Public perceptions also influence their engagement with non-formal Chemistry learning. For example, Zare et al. comments that people associate chemistry with words such as ‘risk’, ‘danger’ and ‘pollution’, which may lead them to be apprehensive to participate. 31

Although increasing public exposure to chemistry is important, exposure alone is insufficient. These non-formal learning experiences should be intentionally crafted to reflect and address existing public attitudes toward chemistry, as emphasized by both the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) and the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC). 12 , 34

1.3 Aim and research questions

This scoping review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of non-formal chemistry learning published in the last 10 years. In doing so, we aim to identify gaps in the research landscape that could be addressed in the future.

To accomplish this goal, the study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1.

To what extent are the individual science disciplines (biology, chemistry, physics) represented in recent non-formal learning literature?

RQ2.

What insight can be obtained from the non-formal chemistry learning literature in the last 10 years through a quantitative analysis of descriptive factors such as format of activity, location of activity, duration of activity etc.?

RQ3.

What are the major themes across the literature in the last 10 years regarding non-formal chemistry learning and what future areas of research are important as a consequence?

2 Methods

2.1 Scoping review vs. systematic review

Review articles can be systematic or scoping. A systematic review is best implemented when a particular question is being researched. These reviews usually confirm current practice, investigate conflicting results, and inform further research or decision making. 40

On the other hand, scoping reviews are used to gain a wide coverage of a topic in which it is unclear what specific questions can be investigated due to lack of critically reviewed research. 41 They are useful for identification of knowledge gaps, clarifying key concepts in the field and identification of research methods being conducted. 40 A scoping review can then be used as a precursor to systematic report where more precise questions can be addressed after completion of the scope.

Non-formal chemistry learning is not a well-researched area, for example, we could not identify a systematic review published in the literature. Therefore, for the reasons outlined above, we sought to carry out a scoping review.

Arksey and O’Malley outline five stages of a scoping review: identifying the research questions; identifying relevant studies; selecting studies; charting the data; and, collecting, summarising and reporting the results. These stages have been implemented herein. 41

2.2 Literature search strategy

The search was conducted covering a 10-year period from May 2013 to April 2023 using the Web of Science platform, which indexes a wide range of diverse relevant journals. Web of Science includes journals such as (but not limited to) Journal of Chemical Education, Chemistry Education Research and Practice, Journal of Research in Science Education and Journal of Science Communication which align with our topic of interest and research questions.

Noting the confusion in the literature between the terms non-formal and informal, we have used both in our search terms. We have also expanded the search parameters to include other commonly associated terms. The term “science cent*” was used to take into consideration the American and British spelling of centre/center. The terms science museum and science centre are also used interchangeably but both facilities have a similar purpose – to engage the public in science – so both establishments were included.

The search terms used were:

[Topic = (“non-formal learning” OR “non-formal education” OR “non-formal science” OR “non-formal STEM” OR “informal learning” OR “informal education” OR “informal science” OR “informal STEM” OR “STEM outreach” OR “science outreach” OR “science museum” OR “science cent*” OR “out of school”)].

The total number of papers retrieved within this search was 13,124 before further refinement.

RQ1 of this scoping review was to identify and compare the published literature of non-formal learning activities relating to all three sciences – biology, chemistry, and physics. Therefore, the specific science was added to the search terms individually. Asterisks were used initially to expand the search field. For example, using the search term “bio*” ensured that papers including the words “biology” and “biological” were included. As an example, the final search term for biology-focused literature was: [Topic = (“non-formal learning” OR “non-formal education” OR “non-formal science” OR “non-formal STEM” OR “informal learning” OR “informal education” OR “informal science” OR “informal STEM” OR “STEM outreach” OR “science outreach” OR “science museum” OR “science cent*” OR “out of school”) AND “bio*”].

The same was carried out for the search term phys* to include “physics” and “physical science”, and the search term chem* to ensure inclusion of words such as “chemistry” and “chemical”.

Abstracts were inspected, and full articles scanned, to ensure the content was relevant.

2.3 Chemistry-focused literature triage protocol

For the chemistry-focused search a total of 355 results were found and manually triaged using exclusion and inclusion criteria (Table 2, Figure 1) to determine which papers were included in the detailed review. 42

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature search.

| Inclusion Criteria (IC) | |

|---|---|

| IC-1 | Aligns with Johnson and Majewska’s definition of non-formal learning (Table 1) |

| IC-2 | Contextualised as a STEM activity with at least one topic with a chemistry focus. |

| Exclusion Criteria (EC) | |

| EC-1 | The study is written in another language other than English |

| EC-2 | The study is not fully available |

| EC-3 | The study is a meeting abstract |

| EC-4 | The study is another secondary source such as a literature review |

Flowchart showing literature triage process.

It should be emphasised that many publications referred to informal learning, where we suggest the term non-formal learning would have been more appropriate, as defined by Johnson and Majewska (Table 1). In these circumstances the publication falls within the scope of Inclusion Criterion 1.

Following the triage using abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 79 papers remained. However, after reading full articles, 7 further papers were later excluded as they were not relevant as they were found to be related to formal learning. Papers were also excluded if after further reading they did not contain any chemistry related topics. This happened on occasion when papers were titled as “STEM outreach” but only contained another aspect of STEM, e.g. engineering, technology, or mathematics. A further 5 papers were excluded as they were not written in English and another 26 papers were excluded due to being inaccessible to the authors.

After this process, a total of 34 papers were included in the final review. These papers were interrogated for various quantifiable features such as, year of publication, country of publication, target age of participants, location of activity, format of activity, evaluation of effectiveness of activity.

2.4 Strategy for construction of significant themes

Qualitative analysis to identify significant themes was conducted on the final set of 34 papers to provide further context to the quantitative analysis. Each paper was read in full by MJD’A to establish the main arguments or conclusions, which were tabulated. A subset of papers was also read independently by FJS to provide a degree of reliability and to confirm the individual arguments. MJD’A and FJS then identified the most frequently encountered ideas, and those which were similar or related were grouped into themes. All authors then sought to contextualise and understand these themes through iterative discussion leading to the narratives presented herein.

3 Limitations

In this scoping review, we have examined current practices in non-formal chemistry learning by reviewing recent literature, with an emphasis on research studies that present or evaluate specific non-formal chemistry learning activities. However, many non-formal chemistry learning activities operate without any formal dissemination and would not have been captured in this review. Therefore, our description of the frequencies of the various categories of non-formal chemistry learning relates only to the published literature, and any extension beyond this scope should be done with caution.

Additionally, our search was limited to English-language, peer-reviewed literature indexed in major academic databases. This approach may have resulted in the under-representation of research conducted in non-Western contexts or published in local journals, grey literature, or non-English languages. As such, valuable insights from diverse educational and cultural settings – where informal or non-formal chemistry learning may take different forms – may not be reflected in our findings. 43

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the biases, perspectives, and theoretical frameworks of the authors of the 34 papers included in this review may have influenced the themes and interpretations that we have constructed. Our own perspectives as researchers may also have shaped the analysis and conclusions we present.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Comparison of published literature across individual science disciplines

We were first interested in a comparison in the volume of literature across the three different science disciplines, chemistry, biology and physics (Table 3).

Asterisk-based search term results.

| Search term | No. of results returned | % Of publications |

|---|---|---|

| Bio* | 1,527 | 46 |

| Chem* | 355 | 11 |

| Phys* | 1,436 | 43 |

Using the asterisked search terms for each science, chemistry was found to be the most under-represented science, with 355 publications, or 11 % of the total publications of all three sciences (Table 3).

However, we did notice that the asterisk method (Table 2) may have artificially inflated the results for the “phys*” search string as it also returned papers including the words “physical” and “physiology” which were unrelated to the discipline of physics. Therefore, we also completed the search using only the full names of all three sciences – ‘biology’, ‘chemistry’ and ‘physics’ (Table 4).

Full science name search term results.

| Search term | No. of results returned | % Of publications |

|---|---|---|

| Biology | 260 | 38 |

| Chemistry | 151 | 22 |

| Physics | 278 | 40 |

Chemistry was still the most under-represented science using this search methodology. The search results for biology and physics returned almost equal numbers of papers, 260 for biology and 278 for physics. However, chemistry only returned 151 papers, or 22 % of the total of all three sciences.

Across both search methods, chemistry was the most under-represented science in the non-formal learning literature from 2013 to 2023. This finding is aligned with an observation that Zare made in 1996, who stated that chemistry was the most under-represented science discipline in science museums, a common non-formal learning environment. Clearly, the problem persists to recent times.

Having found that chemistry was the most under-represented science within the non-formal learning literature, we proceeded to analyse the chemistry-specific literature in more depth.

4.2 Quantitative analysis of non-formal Chemistry learning

The collection of 34 non-formal chemistry learning papers was analysed by publication date, country of publication, location of activity, type of activity, participant group targeted by activity, duration of activity, and effectiveness of activity (Table S1). A reflection on each of these categories is presented in the following subsections.

Additionally, the papers were categorised as either activities or non-activities (Table S1). 32 papers focused on a specific non-formal chemistry activity, which involved researchers either creating, implementing and/or evaluating their chosen activity. However, there were two papers which were not focused on activities. Aslan et al. discussed academics’ perception of non-formal learning environments within STEM. 44 Urvalkova et al. discussed the impact of citizen science, in which people engage with chemistry on a voluntary basis. 45 These two non-activities were only investigated by publication date and country of publication within the following subsections, as the remaining categories are only appropriate for activities. However, these non-activity papers were still included to construct the themes across the non-formal chemistry learning literature.

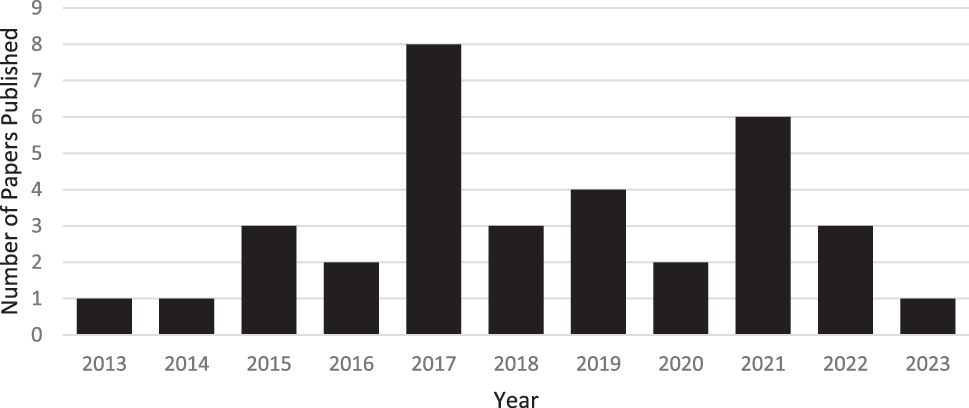

4.2.1 Publication date

The highest number of papers was published in 2017, with a second spike in 2021 (Figure 2). Upon reviewing these particular papers, there are no obvious commonalities that would explain these spikes. There is no consistent increase or decrease over time, and given the small number of publications each year, the fluctuations are likely within expected variation, and thus do not reveal any distinct patterns.

Publications by year.

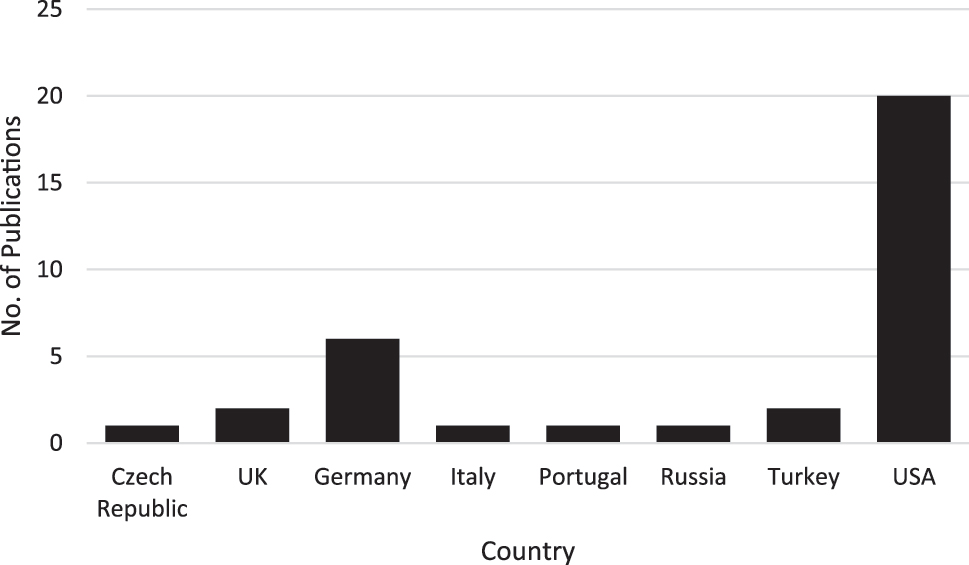

4.2.2 Country of publication

Most papers related to non-formal chemistry learning are from the USA (Figure 3). This is likely, in part, due to the larger population of the USA and the EC-1 exclusion criterion of non-English language papers. There is a slightly larger number of papers from Germany about non-formal chemistry learning, which may indicate an increased interest about the topic in this country. However, these data do not account for relative population between each country.

Publications by country.

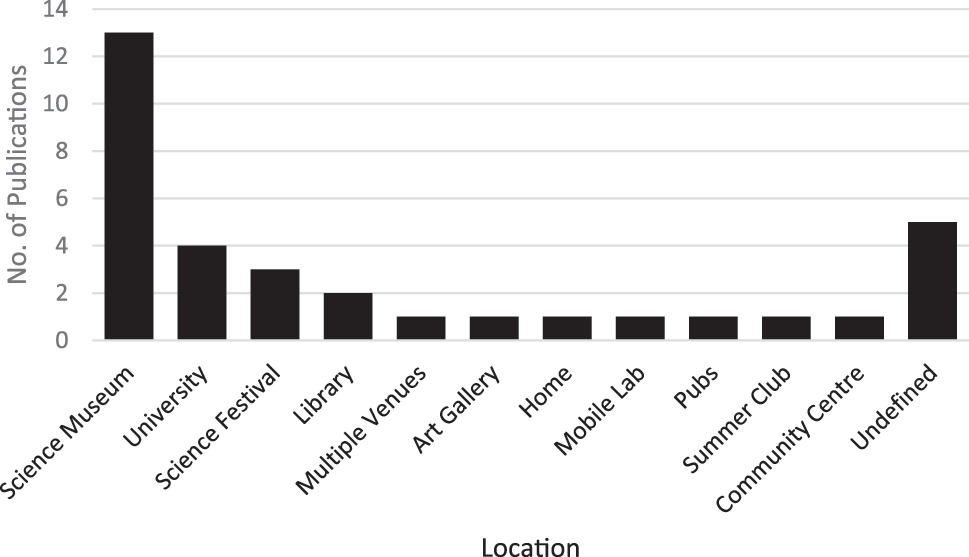

4.2.3 Location of activity

Most of the studies of non-formal chemistry learning involved activities that occurred in science museums (Figure 4). A primary goal of science museums is to explain science and technology to non-experts through active experimentation. Learning in a museum environment is enhanced by the fact that they offer a pleasant and enjoyable environment or experience. 46 This might explain why science museums are the most recognized venues for non-formal science learning. 47

Non-formal learning activity locations.

Considering the overlap of this location category with the targeted audience group (Section 3.2.4), we see that the large number of science museum activities is aligned with the large number of activities targeted at the general public (Figure 5). Indeed, 42 % of activities at science museums were aimed at the general public, which is aligned with the large numbers of visitors to science museums each year. 48

Age of participants targeted by non-formal learning activities.

While science museums are generally attended by the general public, many teachers may also take their classes there to support their curriculum. Indeed, 50 % of science museum activities were targeted at school aged children (both primary and secondary). Consequently, many science museums have education departments who ensure their exhibits are aligned with school curricula.

Interestingly, there are several unexpected locations in which non-formal chemistry learning activities are targeted, such as art galleries, libraries and pubs where participants may attend without the initial goal of engaging with chemistry. 47 , 49 , 50 The art gallery held an exhibition of “A History of Water” to stimulate interest of the chemical changes; the libraries held a family play session featuring understanding the world around them; and the pub location was where students would engage the general public with scientific demonstrations. These experiences were opportunistic, potentially engaging with participants that would have not otherwise sought out non-formal chemistry learning. Given the well-established public apprehension of Chemistry, many may avoid attending an non-formal chemistry learning activity. 51 For example, Hobbs et al. describe a textile crafting course held at a crafting studio in a socio-economically deprived area where they tried to reduce the apprehension of engaging with chemistry activities. 52 Therefore, holding non-formal learning activities in unexpected locations could be a method to ensure that it is not only members of public with pre-existing interest in chemistry.

One noticeable absence of activities within the literature is in evaluating entertainment-based non-formal learning such as TV shows or the use of online media, such as YouTube. For the latter, this may be due issues around perceived quality or educational value available within YouTube. 53 Additionally, there may be challenges associated with quantifying this non-formal learning format due to the quantity of content. For example, the classic chemistry activity of creating slime had over 1.2 million slime recipe videos published by 2017. 54

In summary, science museums play a key role for a location for non-formal chemistry activities. Their alignment with the education curriculum makes them a valuable resource for school groups to assess their learning away from the traditional classroom environment. Beyond museums, non-formal chemistry activities also take place in unconventional locations including art galleries and pubs, reaching individual who may not typically seek out chemistry learning experiences. However, there is a gap in the research into formats including television and online media, likely due to the difficulty of evaluation these diverse and abundant resources have on education.

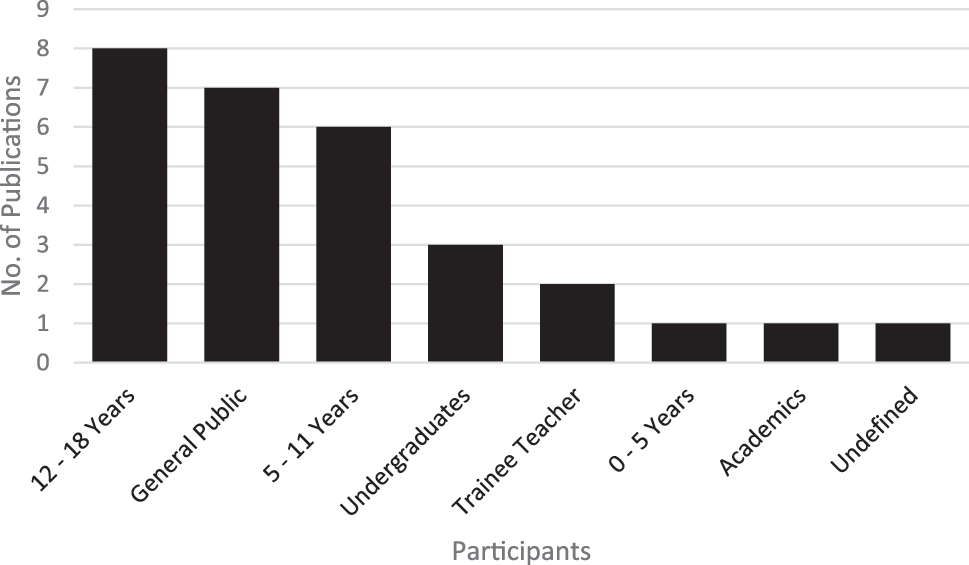

4.2.4 Participant groups targeted by activities

A participant is defined as a person who took part in an non-formal learning activity, rather than one organising or administering it, whom we shall refer to as the organisers.

The general public is commonly defined as those with a non-scientific background. 55 For the purpose of this scoping review, our definition for an activity to be targeted at the general public is one where any individual engages in non-formal learning for leisure purposes. The category of academics in this scoping review is defined as professional individuals teaching or researching at a higher education institution. 44 Trainee teachers are individuals who are undergoing formal education and practical training to gain the status of qualified teacher. 56

However, if an activity was targeted at a specific age range or group of individuals, then it would fall within an appropriately defined category, such as 12–18 years or undergraduates.

Most non-formal chemistry learning activities were targeted at school-aged participants, aged from 5–11 and 12–18 years old or the general public (Figure 5). As explained in Section 3.2.3, this is well-aligned with science museums being the most frequently targeted location.

Non-formal chemistry learning involving school-aged participants generally involved experiments with scientific equipment, science shows or combining science with craft activities. 52 , 57 There are several likely reasons for the greater number of activities targeted at school-aged participants. 51 A major driver is using non-formal chemistry learning as a means to explore the wider applications of chemistry and career options. 51 This is often done through connecting non-formal learning and formal learning in school. 49 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 60 For example, Hooper-Greenhill found that 86 % of teachers regularly visit cultural institutions to supplement the curriculum and to motivate their students. 46 However, most teachers can only justify a non-formal learning activity if it aligns with their curriculum. 46 , 56

In particular, participants aged 12–18 may be at points in their education journey that benefit from extra-curricular input. For example, the pressures of exams or important career choice decisions may negatively affect their attitudes towards chemistry, subjects, or school in general, through feelings of frustration or boredom. 61 Consequently, curriculum-adjacent activities, through non-formal chemistry learning, can be used to deliver positive experiences, maintaining motivation and interest, and improving self-concept. 52 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 However, it may be that the particular non-formal chemistry learning activity needs to be chosen with care. For example, many activities create these positive experiences through exciting demonstrations involving impressive visuals or explosions. 65 This may be useful for gaining participants’ initial attention, and generating short-term interest, but may not lead to long-term influence. 52 , 61 , 63

The non-formal chemistry learning activities targeted at participants aged 5–12 focused less on careers and the wider societal impacts of chemistry, but rather on more familiar contexts, such as food science or using everyday materials. 66 , 67 Furthermore, for this age group, non-formal learning activities often focus on developing scientific inquiry skills, albeit in different ways. Morais encourages participants to draw explanations, whereas DeKorver et al., Macbeth et al., Zhillin and DeWilde et al. encourage verbal explanations. 57 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 Ahn et al. develop scientific inquiry through discussion using a social media platform. 70 Although there appears to be a preference for verbal explanations, Ahn et al. and DeKorver et al. suggest that there are other ways to develop scientific inquiry for those who have low or no language ability such as taking photos, diagrams, or drawing of their experiences and what interests them in the moment. 68 , 70

Only one paper targets non-formal chemistry learning activities at children from 0–5 years of age. 50 This activity encourages the participants to explore the world around them using play and observation of the behaviour of everyday substances e.g. how oil and water interact. Children of this age will not recognise the activity as chemistry, however the context still enables them to explore and play which are key factors in their cognitive development. Indeed, the interaction between the children and adults during play is thought to be particularly important. 50 The lack of literature on non-formal chemistry learning targeted at 0–5 years of age is likely a result of the challenge in developing chemistry-related activities for this age group, given their lack of understanding of the concept of ‘chemistry’. As parents, or other appropriate adults, are also likely to be involved in the activities targeted at 0–5 year olds, their lack of confidence in chemistry may further hinder engagement in non-formal chemistry learning. 34 Indeed, Ball suggests parents are the first educators of their children but require support to be confident in this role to support learning. 71 It may be more effective to target more non-formal chemistry learning towards parents as they will have the most influence on what and how their young children learn.

There are many non-formal chemistry learning activities that focused on the general public as participants, including activities like public lectures, exhibits or experiments using common household items. Sometimes, the context of popular culture was used to attract people to the non-formal chemistry learning activity, for example connecting science with aspects of current popular movies. 72 Common goals of the activities were the reduction of ‘chemophobia’ and developing society’s awareness of how chemistry impacts their everyday life. 35 It is understandable that there were many activities targeting the general public as the misunderstanding of scientific information could affect peoples’ lives through ill-informed decisions. 25 However, we would argue that individuals of the general public who attend non-formal chemistry learning activities may already have a high interest in science, and therefore these activities may not be reaching the most appropriate audiences.

There were only three papers that targeted undergraduate students, all of which integrated non-formal learning as part of their formal undergraduate education. The low frequency of literature targeted at this group is likely due to this demographic already possessing a strong interest in chemistry, thus already meeting one of the main goals of non-formal learning. Another demographic with low representation were trainee teachers, and again, this group will likely already possess a high science interest. Whilst trainee teachers are represented in the participant categorisation, fully qualified teachers are not. This may be due to the time demand placed on teachers to deliver an already dense curriculum.

In summary, most non-formal chemistry learning activities are targeted towards school-aged participants and the general public. This may partly be due to ease of access to these demographic groups and, certainly for the school-aged participants, for specific educational or career-orientated goals. There may be some doubt around whether the general public who attend such activities already maintain a high interest in science, and therefore whether these activities have an appropriate reach. Other demographic groups are less represented in the literature on non-formal chemistry learning likely because they are either challenging to access (teachers, 0–5 year olds) or already possess a high science interest (trainee teachers, undergraduates). We suggest that non-formal chemistry learning targeted at 0–5 year olds could perhaps be better facilitated through targeting parents. We also note an absence of papers that consider other traditionally under-represented groups, such as those who do not have English as their first language, those with disabilities, or those from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

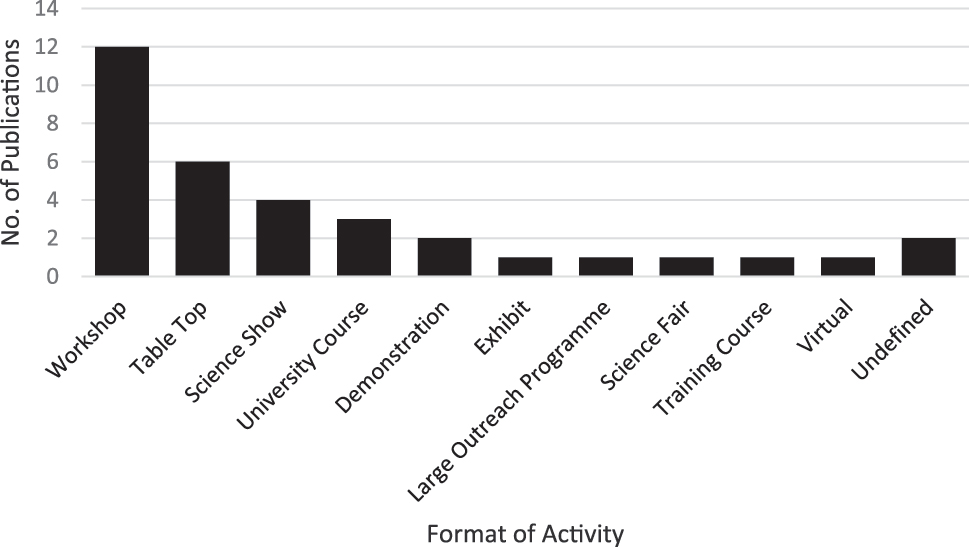

4.2.5 Format of activity

Many different formats of activity were represented across the papers, ranging from one-off, small-scale, portable activities, such as table-top activities, to long-term, permanent structures, such as exhibits. The formats represented also include courses for training and universities (Table 5).

Definition of activity format.

| Format of activity | Definition |

|---|---|

| Demonstration | The science communicator showing a small group an experiment. |

| Exhibit | A permanent self-standing structure that can be self-led by the participant, often found in museums or science centres. |

| Large outreach programme | A multi-year programme from an organisation or research group. |

| Science fair | Multiple people delivering different activities at one time. |

| Science show | A performance with a theme to an audience. |

| Table-top | A one-off activity which takes a few minutes to complete. |

| Training course | A course which is teaching a specific skill for professionals. |

| University course | A course where students partake in a non-formal learning activity which is aligned with their course. |

| Virtual | Occurs fully online. |

| Workshop | Multiple hands-on activities with a theme. |

The most popular format of activity is a workshop, which consists of several different activities which are all aligned to the same overarching theme (Figure 6). This theme aids the establishment of a coherent narrative for the participants. Themes which are included in the literature include food science, climate change and health. 59 , 64 , 66 , 73 , 74 These themes all contextualise chemistry within the participants everyday lives, thus establishing relevance.

Format of non-formal chemistry learning activities. For definitions of each format, see Table 4.

Workshops usually involve low risk experiments that participants can complete themselves with minimal support. For example, Anderson et al. designed 15 low-risk experiments on the theme of food science, including testing for water quality, chromatography and making dyes. Their analysis revealed that that a hands-on experience was a significant influence on participant interest, as was the excitement of using new scientific tools and observing new phenomenon. 25

Tabletop activities have some similarities to workshops including having a hands-on approach for participants, but they differ as they only consist of only a single activity. They can be especially useful for engagement at events such as science fairs, where the residency time of participants at a particular activity is often low, and there is limited available space. 35 , 47 These tabletop activities are beneficial in providing an introduction of a specific chemistry topic to the participant. 25 , 50 , 75 They are usually simplistic due to safety concerns, but can increase participant confidence due to their simplicity. 25 , 75 Examples of such tabletop activities including a Lego activity by Kultzmann et al. which involved building a Lego periodic table and an activity of Brown et al. involving participants ‘writing without ink’ using light sensitive polymers. 75 , 76

Science shows are the third most studied non-formal chemistry learning activity identified within this scoping review. 65 , 68 , 69 Participants generally found shows to be enjoyable, whilst also developing their understanding of chemistry. However, whilst science shows are typically exciting, they often lack the beneficial hands-on engagement that many other non-formal chemistry learning activities offer. This interactive element is beneficial for learning as hands-on learning activities are useful in creating meaningful learning. 77 The passive nature of science shows, where audiences must sit and listen for a set period, may explain why fewer studies focus on them compared to more interactive activities like tabletop experiments.

Non-formal chemistry learning has been incorporated into undergraduate courses, such as one physical chemistry module incorporating a visit to an art exhibition to consider the chemistry of water. 49 , 58 However, many students had low motivation to learn associated content, even if they enjoyed the activities, as there was not a formal exam. 58

An exhibit has only been the focus of non-formal chemistry learning once in this scoping review. 35 In this case, it involved helping the general public to make connections between familiar smells and the name of the chemical that gives rise to the smell, such as ethanoic acid (vinegar) or isoamylacetate (banana). 35 The low frequency of papers reported in the literature relating to exhibits is surprising. Exhibits have been described as the ‘heart’ of the experience in museums or science centres. 78 Exhibits often involve significant planning and maintenance, and are operational for long periods of time, the associated costs, with some exhibit development costing £14,000 for a simple touch screen model. 79 It is also noted that some museums and science centres are not able to create and choose their choice of exhibits due to not having staff with the necessary expertise. 78 This may contribute to a low incidence of such non-formal chemistry learning activities, and the concomitant low representation in this scoping review.

In summary, the most described formats for non-formal chemistry learning activities in the literature are workshops and tabletop activities. This may be partly due to the benefit of the hands-on approach these activities afford to participant motivation or excitement. Science shows are also well-represented in the literature, and this again may be due to the engaging nature of these activities despite not being hands-on. The less popular formats such as exhibits and science fairs may be due to these formats taking more time and resources to plan and execute.

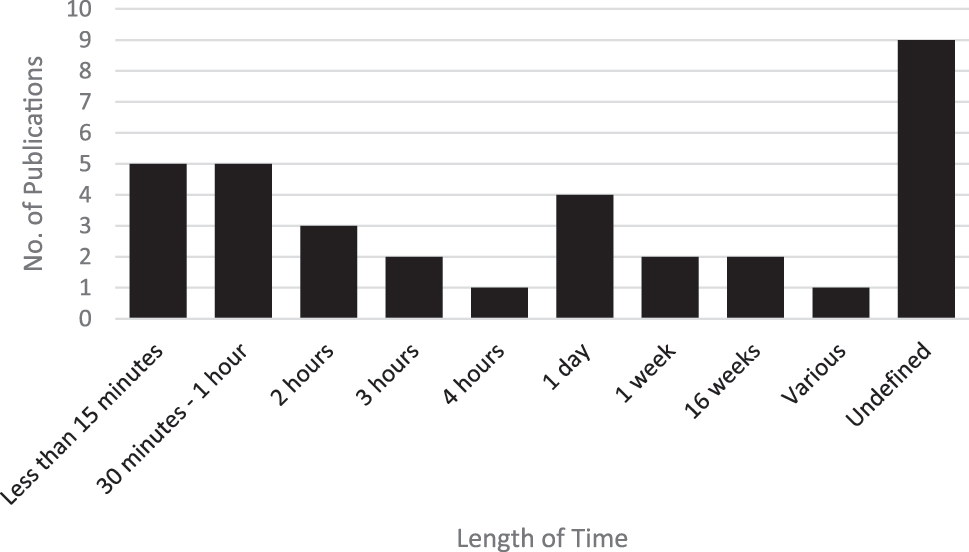

4.2.6 Duration of activity

The duration of activity was determined by the total time from the start of the first event and the conclusion of the last event, including any periods between that were not related to the activity. For example, the duration of the semester activity was an hour lecture weekly over a full semester. Short periods of time for activities including less than 15 min or under an hour are the most frequent time for activities reported in literature, aside from those which did not state a duration (Figure 7).

Duration of non-formal chemistry learning activities.

There could be a variety of reasons that most papers do not state the duration of the activities they describe. Some papers present activities that allow for variation, thus being challenging to quantify, such as Boyd’s green polymer synthesis activity which has six different methods, and can be adapted for different age groups. 54 Or, Yang et al.’s pandemic-era virtual learning activities, where participants could progress at their own rate, even reengaging with the same material. 74 Other papers evaluated large programmes of outreach covering many cohorts and many years, but did not provide sufficient detail at the level of individual activity to quantify duration, such as Kollmann et al.’s ‘Collaboration for Chemistry’. 51

The duration of an activity is highly related to its format. The high frequency of the under 15 min duration is mostly associated with table-top activities. The similarly frequent less than 1 h duration is mostly associated with table-top activities and workshops. Workshops also dominate all durations between 2 h and one day. The tendency for shorter duration activities, could be due to a variety of factors. For example, there may be limited time for an interaction with participants, such as when individuals are free-roaming in science museums or where there is a stall or stand set-up. Additionally, these activities are voluntary, and often rely on participants giving up their free time. Activities that require greater durations, are mostly planned activities or semi-mandatory e.g. trips associated with education purposes. These longer durations require careful planning to maintain participants involvement and engagement. Research indicates longer activities can lead to an increase in cognitive load, which may lead to diminished engagement. 80 Therefore, a strong interest is critical as when participants are genuinely interested, they are more likely to participate for a longer period of time. 81 To enhance engagement and achieve successful outcomes over a longer duration, a sense of relevance, interest and enjoyment must be fostered.

In summary, non-formal chemistry learning activities can come in a range of durations, depending on the format, environment and aim of the activity. However, many papers do not comment on the duration of an activity likely due to challenges associated with its measuring. Activities with shorter durations, mainly table-top activities and workshops, predominate, and this could be due to ease of implementation and not being burdensome of participants free-time. We observe that across the literature there is limited information on how the duration of an activity affects its success, however success is defined. Therefore, given the various logistical and resource challenges around many non-formal chemistry learning activities of long duration, perhaps more research is required to understand if they are worthwhile. The opposite argument could be made if the effectiveness of short duration activities is limited. Indeed, one could speculate that the purpose of activities of different durations could be different, with those of short duration sparking initial, but perhaps short-lived, interest, and those of longer duration embedding sustained changes in interest, motivation and career aspirations.

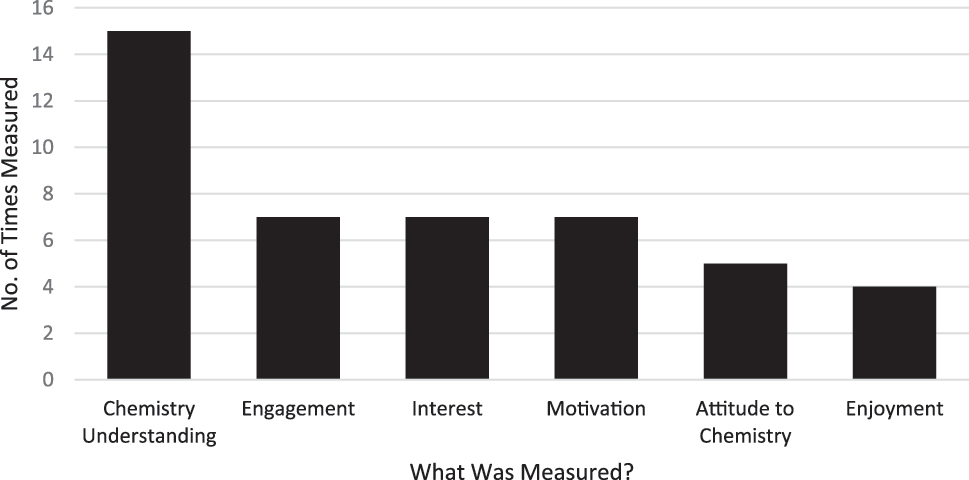

4.2.7 Measuring effectiveness

In this scoping review, we define effectiveness as the success of an activity in achieving the desired result intended by the non-formal chemistry learning organiser.

Only 25 out of 34 papers in this scoping review measured effectiveness, therefore these 9 papers are not represented in the below analysis.

We identified several attributes that were measured to gauge effectiveness: engagement, attitude to Chemistry, interest, Chemistry understanding, motivation and enjoyment. Each of these attributes are well-researched behavioral psychology constructs with complex meanings, however we provide a simple definition of each sufficient for this review (Table 6, Figure 8).

Definition of attributes used to evaluate effectiveness.

| Attribute | Definition |

|---|---|

| Engagement | A qualitative level of interaction with content, activities, and people. 82 |

| Attitude to chemistry | A tendency to view a particular subject with favour or disfavour. 83 |

| Interest | Participants are captivated by an activity and want to explore further. 84 |

| Chemistry understanding | Participants come to know something from the activity. 85 |

| Motivation | The energy or drive participants have to do something. 86 |

| Enjoyment | Participants express positive experiences to an activity. 87 |

Attributes used to measure effectiveness of non-formal chemistry learning activities. N = 45 rather than 25 as several papers used multiple attributes to measure their effectiveness.

Chemistry understanding was the most evaluated attribute to measure the effectiveness of an activity (Figure 8). This suggests that the main goal of most activity organisers is to improve their participants’ understanding of a chemistry concepts. This is somewhat unexpected given the widespread emphasis on fostering interest and enjoyment as primary goals of non-formal learning activities. 51

Previous literature has established that creating learning intentions to facilitate chemistry understanding is difficult to establish for non-formal learning activities in comparison to formal classroom environments. 69 Non-formal learning, by contrast, encourages participants to explore topics of their own choosing, raising the question of how structured chemistry understanding aligns with the more flexible nature of such activities.

Engagement, enjoyment, interest, attitude and motivation are closely related constructs that were all similarly frequently evaluated. For example, a participant with a strong interest in the subject is likely to be more motivated to engage, which, in turn, enhances their enjoyment of the experience and attitude towards the subject. 52 Indeed, there is scope for these interactions to be cyclic, where an increase in enjoyment and attitude lead to further increases in interest. We discuss this further in Section 4.2. It is worth highlighting that the complex interactions between these constructs were not always considered within the papers, where often one construct was selected to be evaluated without consideration of the others. This inconsistent and incomplete assessment of the effects on the outcomes of the non-formal learning chemistry activities may suggest that the purpose of the activities is not always clear or well-considered.

It is important to establish clear definitions and differences between what is meant by the term duration compared to engagement. The attribute of engagement within this scoping review includes demographic data that can be useful to measure in research as it allows for gaps in certain groups of people for participation to be identified. This will then allow for identification of underrepresent demographic groups to allow for activities to be create to increase their engagement. 74

Engagement can be defined as actively participating in an activity either physically, mentally, or socially. 70 Engagement can manifest in different ways. Some participants may engage by asking questions about what they are experiencing, 70 reflecting on their experiences quietly, 49 or physically doing with the activity itself. 35 It is important to differentiate between duration of an activity, previously discussed in Section 3.2.6, and engagement. Whilst the duration of an activity may provide some measure of actual engagement, it is likely that engagement is over estimated particularly in longer activities, such as science fairs – in particular the reverse science fair conducted by Mernoff et al. 88 This is an important aspect to consider as only meaningful engagement with an activity is likely to result in a desired change in the other attributes that are used to measure effectiveness, which is discussed further in Section 4.2. 73

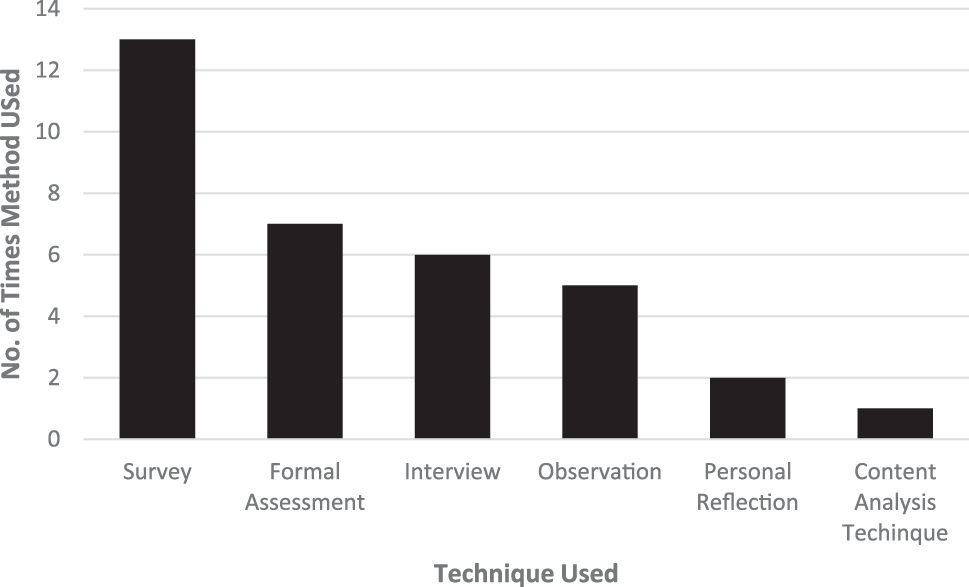

A variety of data collection methods are used to measure the effectiveness of non-formal chemistry learning activities (Table 7, Figure 9).

Definitions of evaluation method types.

| Type of Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Survey | Questions in which participants answered anonymously about their experience. |

| Observation | Researchers watching and recording the actions of the participants. |

| Interview | A structured discussion with pre-set questions with the participants. |

| Personal Reflection | Researchers evaluating their activity with a focus on strengths and areas of improvement |

| Formal Assessment | A set test with correct answers which contribute to a formal grade. |

| Content Analysis Technique | Analysis of children’s drawings. |

Method type used to evaluate effectiveness of non-formal chemistry learning activities.

Surveys are the most popular method of evaluation possibly because they are often quick and easy to administer to many participants at once. Most surveys use a Likert scale or several unrelated or semi-related Likert-items. 50 , 52 , 69 These allow for simple quantification of data but may not provide a deep understanding of the underlying reasoning. Interviews, which are third most frequent in our scoping review, can be used gain this deep understanding following a survey, or they can be a stand-alone measurement.

Formal assessment is when there is set questions which are used to test for learning after completion of the activity. Formal assessment was also frequently encountered, most commonly with measuring chemistry understanding but also was used to incorporate the measure of student’s motivation and interest in engaging with the non-formal learning activities. This seems to occur in cases of collaboration between non-formal institutions and formal institutions aligned to specific learning outcomes. 49 For example, Heider et al. used formal assessments of a multiple choice concept assessment and a written reflective report about their experience in the non-formal learning environment, to go towards a participant’s final grade in their schoolwork. 49 This incentive may encourage students to invest considerable effort into the activity. However, it is worth noting that non-formal learning environments may be apprehensive to implement formal assessments, as this may conflict with the principles of non-formal learning. 69

Other, more diverse, measurement tools were also used, albeit less frequently. Standard evaluation methods, such as those mentioned above, may be challenging for particularly young participants due to their excitement or limited communication skills. Content analysis of drawings can be an effective evaluation tools in this scenario. 67 , 68 For example, Morais analysed children’s drawings after they had participated in a scientific experiment. 67 Some methods of evaluation do not directly involve the participants themselves, such as observations or personal reflections.

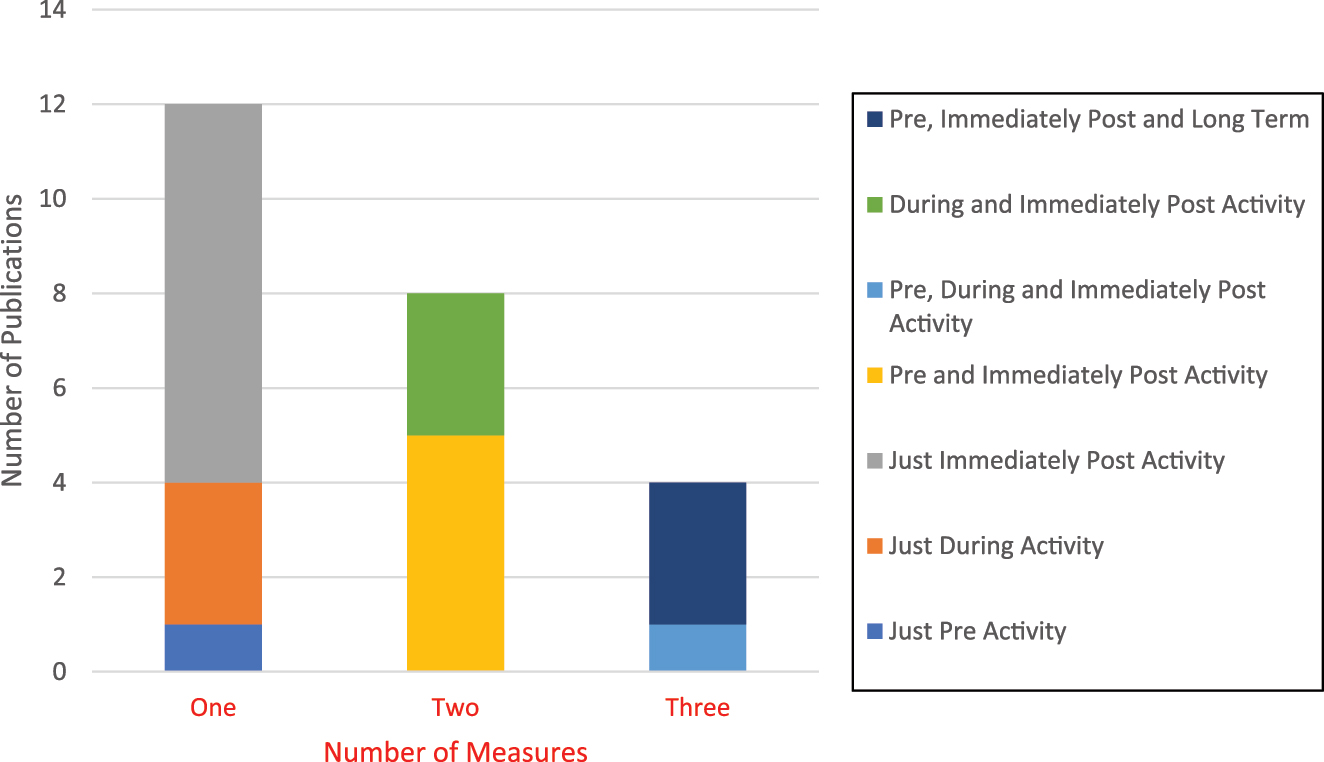

Evaluation of the non-formal chemistry learning activities were conducted a various different time points relative to the activity (Figure 10).

Frequency and time point of evaluation methods used to measure the effectiveness of non-formal chemistry learning activities.

At a high level, our analysis shows that most non-formal learning activities are measured for effectiveness at a single time point, followed by two then three time points. This is perhaps unsurprising given the additional effort required for multiple measurements.

The most common single time point to evaluate the effectiveness of the activity was immediately after its completion. This is likely a mixture of convenience and that the experience can be reflected on with greater accuracy and reliability. 68 During activity evaluation is less frequent, possibly due to not wanting to disturb participants and thus reduce engagement. 35 Consequently, most during activity evaluation takes the form of observations. 35 , 65 , 70 There was once instance of a single time point pre-activity measurement, which the researchers were interested in the what motivated participants (parents and children) to engage an non-formal learning activity. Although useful to investigate the factor of motivation to ensure the chosen demographics are willing to engage, this paper does not evaluate the activity itself. 89

Single time point measurements of effectiveness, even post activity may not give reliable data due to participant bias, or the Hawthorne effect. 90 A pre- and post-measurement design should be more reliable, and pleasingly, these were the second most frequent measurement schedule. However, it is important to be wary that a pre-evaluation may be off putting for some participants. For example, the questionnaire used by Schluter et al. took 7 min to complete before the activity was even described to the participants. 89

Several studies were more robust in their measurement schedule and included a long-term measurement in addition to pre- and post-activity. Long-term evaluation is useful to gauge sustained changes in the participants rather than only short-term effects. 91 However, these are logistically challenging as participants may not visit the non-formal learning environment again or personal details would need to be stored to maintain contact.

In summary, most activities described within this scoping review had their effectiveness measured in some way, with the exception of the nine papers that only described the activity itself. However, this does not necessarily mean that most non-formal chemistry learning activities undergo evaluation, as this review only considered those that were published in the academic literature, and which likely necessitated evaluation as a criterion for publishing. The specific attributes that were measured were diverse, and we therefore suggest that either the specific purpose of non-formal chemistry learning is not well-understood or non-formal chemistry learning has multiple goals. Interestingly, the most frequent attribute to be measured was chemistry understanding, which we suggest is not well-aligned with the six established goals of non-formal chemistry learning, as defined by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, in the USA. Many different measurement tools were used, adapted to the particular activity, environment or participants, but with surveys being most frequent. The measurement schedule was similarly diverse, and we note that many, if not most, activities measured their effectiveness at only a single time point giving rise to less than robust data. Pre- and post-measurements or pre-, post- and long-term measurements were observed but these were not the most frequent. However, we suggest that these more robust measurement schedules are more logistically challenging to implement.

5 Significant themes

We next sought to perform a qualitative synthesis of important commonalities across the set of papers that may not have been otherwise captured by the preceding quantitative analysis. This was achieved by extracting the main concepts of the papers and establishing them as themes. Through these themes, we aimed to gain insight into areas of particular significance within the topic of non-formal chemistry education or identify opportunities for further consideration and research.

These findings are presented as two overarching themes, described in the following subsections. However, we acknowledge that they are not mutually exclusive, and some ideas are inter-related. Briefly, the themes were as follows: inclusivity of Non-formal chemistry learning: activities, and their associated environments, should be tailored to their target participants, while being flexible, and the interaction between affective-motivational factors and engagement is cyclic, presenting a challenge for non-formal chemistry learning activities.

5.1 Inclusivity of non-formal chemistry learning: activities, and their associated environments, should be tailored to their target participants, while being flexible

A learning environment can significantly impact a learner’s experience, both positively and negatively. Hobbs et al. states that if learners have never experienced a specific non-formal learning environment previously, they may feel initially unsure and be hesitant to participate. 52 In the chemistry learning activities designed by Hobbs et al., they ensure that a familiar environment is created by hosting their activities, for families and teenagers, in community venues such as libraries. 50 , 52 In addition to the more common learning environments, such as science museums, more unusual environments may offer this familiarity, such as pubs and art galleries, depending on an individual’s experiences. 47 , 49

Also considering the specific environment, Aslan et al. asked academics to identify the non-formal learning environments for which they would typically create non-formal learning activities. Academics identified environments such as natural parks, industrial organisations and planetariums. However, they emphasised that many learners feel instantly more comfortable when they are learning in an environment they have experienced before and is more common to their community. This allows them to then focus on the activity. 44 The most popular environments for academics to plan non-formal learning activities in this paper was natural parks which includes zoos and botanical gardens, but also centres specifically for science learning, such as science centres. However, it is the academics who found these learning environments most popular, with no evidence from this study that they were popular with the participants. Nonetheless, we recognise that it is important for the learning environment to be considered from both the participants’ and the organisers’ perspectives.

While the specific learning environment is likely to be fixed, the activity can offer a degree of choice to increase inclusivity, one of the fundamental core aims of non-formal learning. 70 By providing choice throughout an non-formal learning activity, it can allow participants to access learning at their required level. Indeed, this may be necessary when targeting the general public, which includes an audience from young children to adults. Exhibits can be a useful format to allow for a wide range of ages to engage with the same non-formal learning activity but in different ways. For example, Brown et al. created an exhibit which focused on connecting common smells to the name of the compound responsible for the smell. 35 This exhibit offered choice as participants could: smell different compounds and guess what they were; building the specific molecular structures; complete a puzzle to connect the compounds to the smell; or just read the scientific information.

However, some researchers only want to target specific age groups. For example, Zhilin et al. focused on participants between the ages of 8–10, specifically to promote interest in chemistry and to develop observational skills. 57 Therefore, these goals and age group were central to the design of this activity, ensuring the activities were hands on, using real glassware, and with interesting visible outcomes to make the experience emotionally positive for the participants. Although the activity was very specific in design, it was evaluated in real-time, providing flexible support to ensure success for all participants. Hobbs also targeted a specific age group – under 5s and their parents – to engage with non-formal science learning. 50 This workshop took common science phenomenon such as density and insoluble mixtures and developed these into safe and hands on activities suitable for very young participants. However, their activities were also suitable and enjoyed by the older siblings of the target participants, which the organisers adapted to. Both of these examples strongly support the idea that non-formal chemistry learning activities that are flexible can be beneficial.

Arising from Hobbs et al.’s study was the specific idea of ensuring inclusivity of scientific literacy. 50 Scientific literacy is the ability to use, understand and explain words relating to science. 92 The scientific language used in activities should be accessible to the participants i.e. free of jargon, or using only jargon appropriate to the participants. However, minimising jargon will maximise inclusivity. 47 Scientific literacy can also affect evaluation of the activity. Morais et al. overcomes this issue by evaluating their activity through the analysis of pictures drawn by participants. This not only overcomes the barrier of underdeveloped scientific literacy but, according to Britsch, also promotes scientific literacy by allowing children to reflect and express scientific concepts in a different way. 93 Interestingly, while scientific literacy was considered across the papers, we did not observe any direct consideration of participants for whom English is not their first language. Therefore, we suggest that optimising both the general and scientific literacy associated with activities should be considered to maximise inclusivity.

We draw attention to a lack of consideration of participants from low socioeconomic backgrounds within the design of activities. Such individuals may be excluded from non-formal learning activities due to financial pressures or lower science capital. 52 Low science capital can drive lower motivation, interest and engagement with science activities, and is therefore a particular barrier – this general phenomenon will be considered further in theme 2. Regarding financial pressures, if possible, activities should be free for participants. 66 However, this means a heavy reliance on grants and sponsors, which are limited and thus potentially generating inequity of access. 49 , 94 However, whilst many non-formal chemistry learning activities will be free, there are ‘hidden’ costs, such as travel to and from the activity that are more challenging barriers to overcome. 66 We suggest that it would be useful to hold these activities in local venues such as libraries or community centres to allow for ease of access, in line with the previous reasons around familiarity.

We also note a lack of consideration for participants with additional support needs who are a heterogenous group of individuals with many and varied barriers to inclusion. This is surprising given that non-formal learning environments offer flexibility in the selection of the activity and on the pace of learning which are characteristics that would be beneficial for these participants to increase their success in learning. 95 , 96

In summary, it is important for inclusivity that thought and effort is put into the design of non-formal chemistry learning activities to minimise the barriers that participants may face to engage. This includes the environment that the activity is held in, and also the activity itself. We note that most papers did have a particular target audience in mind, and many designed their activity specifically for this audience. However, many audiences are under-represented and therefore consideration of the barriers they face has not been adequately addressed in the literature. We suggest that good practices include considerations of familiar and accessible locations, costs and literacy levels. A flexible approach within the design of the activity, giving participants choice, and also ad-hoc flexibility, such as during the activity, can be beneficial to the success of the non-formal chemistry learning activity.

5.2 The interaction between affective-motivational factors and engagement is cyclic, presenting a challenge for non-formal chemistry learning activities

In Section 3.2.7 we identified that a large proportion of researchers measured the effectiveness of their non-formal chemistry learning activities through considering participants’ increases in engagement, enjoyment, interest, attitude and motivation. Consequently, these concepts are likely to be important, and we must explore from where this importance arises.

Enjoyment, interest, attitude and motivation are all complex constructs, which are beyond the scope of this review to consider in depth. However, they can be thought of as interconnected affective-motivational factors that all contribute to higher levels of engagement in learning about a relevant topic, in this case non-formal chemistry learning. 97 Indeed, due to the voluntary aspect of non-formal learning, it is particularly important to take these affective-motivational factors into consideration when planning and executing non-formal chemistry activities to ensure engagement. 47 , 51 , 81 , 98 , 99

Burks et al. acknowledge the role of affective-motivational factors through aligning their collection of scientific talks to topics from popular culture e.g. connecting Harry Potter with chemical reactions or Marvel with radioactivity. 72 Burks et al.’s goal was to appeal to a broader audience who may not have already had a strong intrinsic motivation to engage in STEM non-formal learning, but to rely on their other interests to boost engagement.

Similarly, many non-formal chemistry learning activities use the practical side of Chemistry to as means of invoking various affective-motivational factors. 47 , 54 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 89 For example, Wickware’s experimental processes connected to making an ice cream sundae, or Brown’s activity which allows people to write without ink and instead use a photochemical polymer. 75 However, Budke et al. have stated that while exciting explosions are often used to promote engagement through these affective-motivational factors, learning beyond this initial experience can be difficult when individuals come to realise that Chemistry is not only about explosions. 61 Therefore, while initial interest may lead to transient engagement in an non-formal learning activity, sustained interest is the more favourable goal, which could be hampered by a poorly designed non-formal chemistry learning activity.

Brown et al. acknowledge a similar experience in their exhibit connecting organic chemistry with known smells. 35 In an effort to represent a variety of smell producing molecules, they included some with unpleasant smells, such as butyric acid (vomit). Participants avoided these smells altogether and sometimes left the exhibit early after encountering them. Therefore, negative affective-motivational factors can deter participants, reducing their engagement.

Interestingly, we suggest that there is a challenging cyclic nature between affective-motivational factors and engagement. While positive affective-motivational factors increase engagement with an non-formal chemistry learning activity, the goal of the engagement is to increase the same affective-motivational factors towards chemistry. Indeed, many organisers implicitly recognise this since they co-opt affective-motivational factors of alternative interests, in pop culture or similar, to boost the initial engagement with chemistry. 64 , 72 , 76 This prompts us to ask if non-formal chemistry learning activities are mainly attended by those who are already interested in chemistry, and thus if they are truly meeting their purpose of inspiring, increase interest and engagement. 12 What happens if individuals do not have sufficient levels of affective-motivational factors to engage in the first place?

The cyclic nature of the affective-motivational factors and engagement could have negative consequences for certain demographics. In the first theme, in Section 4.1 we identified that those from low socio-economic backgrounds may be excluded from non-formal chemistry learning for a variety of reasons, including low science capital. Such individuals may be less able to relate chemistry to their everyday lives, 49 or they have fewer prior experiences with Chemistry through their social networks through which to foster an interest. 100 This barrier could be reduced by focusing on activities with broad appeals such as crafts or pop culture, as some organisers do. 52 Another demographic that could be affected by the cyclic nature of relationship between affective-motivational factors and engagement are the under 5s and their parents. Hobbs et al. found that most families who attended their non-formal chemistry learning activity already had a high level of interest in science, particularly the desire to expose their children to science. Indeed, many families were repeat attendees on multiple workshop days. 50

In summary, there appears to be cyclic relationship between various affective-motivational factors, such as interest, enjoyment, attitude and motivation, and engagement in non-formal chemistry learning activities. These factors increase engagement, and engagement increases these factors. We question what happens if individuals do not have sufficiently high levels of these affective-motivational factors in the first place, suggesting that many non-formal chemistry learning activities may be attended only by those who are already very interested in chemistry. Indeed, several non-formal chemistry learning activities co-opt affective-motivational factors of alternative interests to boost their initial engagement. This may suggest that many activities are not aligned with the accepted purpose of non-formal learning, to inspire, increase interest and engagement across a broad range of participants. Indeed, the prior need for sufficient levels of these affective-motivational factors may specifically exclude certain demographic groups, such as those from low socio-economic backgrounds. While the research suggests that considering how the different demographic groups will be differently affected by the cyclic nature of the relationship between affective-motivational factors and engagement, we note that there is a lack of consideration around how different formats of non-formal chemistry learning activities interact with this cycle, and for different demographic groups. For example, are workshops more beneficial for young children, while exhibits more beneficial for adults?

6 Conclusions

This scoping review highlights the multifaceted landscape of non-formal chemistry learning, emphasizing its potential to complement formal education and broaden public engagement with science. Notably, our analysis found that chemistry is the most under-represented discipline in the non-formal learning literature compared to biology and physics (RQ1). However, this disparity may reflect publication trends rather than actual non-formal learning practices, suggesting a need for more dedicated research and documentation in non-formal chemistry education. Moreover, the assumption that there ought to be equivalence in representation could also be questioned. None-the-less, as Chemists, we suggest that this under-representation is an interesting finding.

Our quantitative analysis of the literature from the last 10 years revealed various trends (RQ2). Non-formal chemistry activities span diverse formats, including workshops, tabletop experiments, and science shows. These formats dominate the literature, likely due to their hands-on, engaging nature, which fosters participant excitement and motivation. Science shows, despite being less interactive, also receive substantial coverage, suggesting their broad appeal and capacity to captivate audiences. Conversely, exhibits and science fairs are less frequently documented, possibly due to their higher resource demands and complexity in execution. However, while museums are recognized as key venues aligning with formal curricula, unconventional locations such as art galleries and pubs show promise in reaching audiences who may not actively seek science engagement. There is also a gap in the research into other alternative formats such as television and online media, likely due to the difficulty in evaluating the educational impact of these diverse and abundant resources. Interestingly, since conducting the main body of work for this scoping review, the first large-scale census of how YouTube has been used for chemistry education has been published, indicating a growing interest in understanding how such platforms contribute to non-formal chemistry learning. 73

The review also reveals significant variations in the duration of non-formal chemistry learning activities, likely driven by the particular activity format. Shorter activities, such as workshops, predominate due to their ease of implementation and lower time commitments for participants. However, the impact of activity duration on educational outcomes remains underexplored. Short-duration activities might spark immediate interest, while longer ones could foster sustained engagement and deeper learning. This suggests a need for future research to assess the differential impacts of activity duration, particularly in relation to participant demographics and learning objectives. Understanding these dynamics could inform the design of more effective and inclusive programs.

Evaluation practices within non-formal chemistry learning also show significant variability. While many activities undergo some form of assessment, robust methodologies such as pre- and post-evaluations are less common due to logistical challenges. The frequent emphasis on measuring chemistry understanding may not fully align with broader non-formal learning goals, such as inspiring interest or fostering positive attitudes toward science. This suggests a need for more comprehensive evaluation frameworks that reflect the diverse objectives of non-formal learning.

Inclusivity remains a central theme across the literature (RQ3). Most non-formal chemistry activities target school-aged participants and the general public, likely due to their accessibility and alignment with educational goals. However, this focus raises concerns about equity and reach. Underrepresented groups – such as young children, individuals with disabilities, non-native English speakers, and those from low socio-economic backgrounds – face significant barriers to participation. Effective design strategies include selecting familiar and accessible locations, minimizing costs, and ensuring content is appropriate for various literacy levels. Flexible, adaptive approaches during activity planning and execution can further enhance inclusivity and impact.

Another theme of significance is the cyclic relationship between affective-motivational factors – such as interest, enjoyment, and engagement – and participation in non-formal chemistry activities (RQ3). These factors reinforce each other, yet they may also create barriers for individuals who lack initial interest or confidence in science. This raises questions about whether current non-formal learning practices effectively reach those with low initial motivation, particularly individuals from traditionally under-represented backgrounds. Future research should explore how different activity formats and designs can break this cycle and foster engagement across diverse demographics.