Abstract

Background

Modern agriculture recognizes soil biota as major contributors for availabilities of nitrogen and phosphorus to plants. Centralizing focus on exopolymer production of these living entities is need of time to emphasize their impact on soil structural restoration and heavy metal intoxication.

Material and methods

Mung bean rhizosphere collected from 25 locations was serially diluted and poured onto MY agar plates that were incubated for 120 h at 25°C to isolate bacteria having watery mucoidal appearance. Liquid broths of secluded cultures were then tested for optical scattering and were treated with ethanol to precipitate Exopolysaccharides (EPS) for their physicochemical characterization.

Results

Anion-exchange and high-performance size exclusion chromatographic analysis indicated two main monosaccharides, Mannose (52%) and Glucose (29%) fractions of EPS. EPS have substantial (0.2%) protein contents, capacity related to emulsify several hydrophobic substances. 0.5% EPS solution had low viscosity with pseudoplastic behaviour, least suspended particles producing less turbid solutions.

Conclusion

Six strains (M2, M3, M11, M16, M19, and M22) secreted noticeably greater amounts of exopolymers than other strains. Organic nature and pseudoplasticity of these exopolymers helps in soil structural restoration, sulfates and phosphates helps in heavy metals detoxication.

Özet

Amaç

Modern tarım, bitkilere azot ve fosfor yararlanımı açısından temel katkıyı toprak biyotasının yaptığını kabul etmektedir. Bu çalışmada toprak biyotasını oluşturan tüm canlı organizmaların, toprak yapısal restorasyonu ve ağır metal zehirlenmesi üzerindeki etkilerini vurgulamak için, bu organizmalar tarafından üretilen ekzopolimerlere odaklanılmaktadır.

Gereç ve Yöntem

25 farklı bölgeden toplanan maş fasülyesi rizosferleri seyreltilerek, sulu mukoidal görünümlü bakteri izolasyonu için 25oC’de 120 saat süreyle inkübe edilen MY agar besiyerine ekildi. Sıvı besi yeri, optik saçılma için test edildi, fizikokimyasal karakterizasyonunu belirlemek amacıyla ekzopolisakkaritlerin çöktürülmesi için etanol ile muamele edildi.

Bulgular

İyon değişim kromatografisi ve yüksek performans boyut-dışlama kromatografisi ile yapılan analizler sonucunda EPS fraksiyonlarının %52 oranında mannoz ve %29 oranında glukoz olmak üzere iki temel monosakkariti içerdiği belirlendi. Önemli miktarda (%0.2) protein içeriğine sahip olan EPS’nin bu özelliği çeşitli hidrofobik maddeleri emülsifiye edebilme kapasitesi ile ilişkilendirildi. 0.5% EPS solüsyonunun, psödoplastik davranışla düşük viskoziteye sahip olduğu belirlendi.

Sonuç

M2, M3, M11, M16, M19 ve M22 olarak adlandırılan altı suşun, diğer suşlardan belirgin şekilde daha fazla miktarda ekzopolimer salgıladığı belirlenmiştir. Bu ekzopolimerlerin organik doğasının ve psödoplastisitesinin, toprağın yapısal restorasyonu ile ağır metal detoksikasyonunda katkısı olan sülfat ve fosfatlar üzerinde yardımcı etkileri olduğu gözlemlenmiştir.

Introduction

Many microorganisms like fungi, microalgae, archaea and bacteria produce saccharide polymers as structural components, as well as extracellular excretions that are slimy in appearance, loosely attached to the cell membrane as lipopolysaccharides, covalently bonded with cell wall as capsular polysaccharides or totally excreted to the environment as exopolysaccharides [1, 2]. Exopolysaccharides (EPS) are the macromolecules of organic nature generated by identical building micromolecules arranged in repeated manner [3]. Many rhizobial species have surface EPS essential for nodulation [4]. These extracellularly produced biopolymers have diverse biological functions such as protecting cell from desiccation and toxicity of antibacterials, acting as virulence factors in symbiosis and pathogenesis [5] and generated researcher’s attention towards their diversified applications in agriculture as nutrient capturing agents [6], bioflocculants [7], biosorbents, heavy metal removal [8], solute delivery and bioactive agents [9]. Bacterial EPS are generally recognized safe having innovative physiochemical i.e. viscosifying, stabilizing [3], gelling, emulsifying [10], antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics [11] that make them appropriate for usage in agricultural, food and other industries. These are advantageous over plant secretions due to their reproducible physiochemical characteristics, novel functionality with least cost and easy supply [12]. Recently discovered and developed bacterial EPS i.e. xanthan, gellan, alginates, cellulose, hyaluronic acid and succinoglycan have improved rheological and chemical characteristics [13, 14]. Bacterial EPS are more conveniently degraded than synthetic polymers, hence constitute least environmental pollution hazard [15]. EPS are quantitatively as well as qualitatively dependent upon microbial culture and media composition [16]. EPS composition, branching, molecular size and synthesis rate depend upon media composition [17]. High Ca:N ratio favors EPS production [18]. Carbohydrate in media affects EPS yield, viscosity and molecular weight heterogeneity, but had no influence on chemical structure [15].

Keeping in view the above figures it is evident that these bacteria do not cause harm to human or plant health, which also affirms the importance of exploitation of microbial application in agricultural field operations. Therefore, in this study EPS from bacterial isolates were collected to characterize their chemistry and rheology.

Materials and methods

Mung bean rhizosphere samples were collected from 25 different locations (Named M1 to M25) and suspension of 1 g soil was made in sterile water and diluted serially up to 10−6 to isolate bacteria by plating on MY (Yeast extract 10 g, Maltose 20 g, KH2PO4 2 g and agar 20 g) medium [19]. Plates were incubated for 120 h at 25°C and (M1, M2, M3, M5, M9, M11, M14, M15, M16, M19, M21, M22 and M24) plates having shiny watery and mucoid appearance showed exopolysaccharide secreting potential of microbes. These visually observed bacterial strains were further multiplied to obtain their pure cultures. The purified strain (M22) with highest mucoid appearance was then cultivated in EPS-producing broth medium (18.4 g L-1 yeast extract) along with different oligosaccharides (sucrose, maltose and lactose) as bacterial nourishment applied at different concentrations (0, 1, 2, 5, 7 and 10%) then incubated at series of temperatures (12, 22, 32 and 42°C) with orbital shaking (0, 100, 200 and 300 rpm) at neutral pH to find optimized EPS secretion conditions [20]. Bacterial growth in broth culture was determined by measuring optical density at 600 nm after every 24 h’ interval. The optimized EPS-producing medium and conditions will be utilized for all the other strains.

EPS were isolated and purified using the method described before [21] with slight modifications. Bacterial cells were spun at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The cell-free supernatant was collected and kept at 4°C overnight by adding three times 95% pure cold ethanol to precipitate EPS. The precipitated EPS were then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and dissolved in DI water (50% w/v). The solution was then treated with Chloroform: n-butanol: Na2CO3 (4:1:1) to remove lipids. It was then dialyzed using dialysis bag at 4°C for 2 days replacing DI water after every 8 h interval and then was lyophilized.

Colorimetric analysis of total carbohydrates [22], proteins [23] and acetyl residues [24] in EPS were purified and analyzed using UV detection at 210 nm on anion-exchange chromatography (AEC) having 1.5 m×20 cm, quaternary methyl ammonium column to determine its net negative charge (Shimadzu LC-10A, Japan). The column was eluted with 0.05 M NH4HCO3 followed by 0.5–2 M NaCl in the same buffer at a flow rate of 2 mL min−1. Ten milliliter fractions were separately collected to determine molecular mass and sugar composition of EPS.

Myo-inositol was used as internal standard for the analysis of monosaccharides. 0.1 mg equivalents of purified EPS carbohydrates were methanolysed using 0.9 M methanolic HCl for 12 h at 80°C giving methyl glycosides mixture as an end product that was dried at room temperature. Five microliter of pyridine, 5 μL of acetic anhydride and 50 μL of dried methanol was added to N-acetylate the mixture [25]. The N-acetylated mixture was treated with 15 μL trimethylsilyl imidazole for an hour resulting into N-acetylated trimethylsilylated glycosides. Prepared samples were dried under nitrogen and dissolved in 0.5 mL hexane. The sample was then analyzed on Gas Chromatogram GC (Shimadzu GC-8A) using 30 m×0.32 mm PTE 5 fused silica capillary column injecting 1 μL. Oven was initially adjusted at 80°C for 2 min then to 235°C @ 20°C per min.

Viscosity of the 0.5% (w/v) EPS-water solution was measured by using controlled stress Bohlin CSR10 Rheometer (Dallas, TX, USA). Turbidity of the solution is a degree of total suspended solids and was measured by LaMotte 2020we Nephelometer (Chestertown, MD, USA) total suspended solids (TSS) was measured by filtering and weighing the suspended particles.

Results

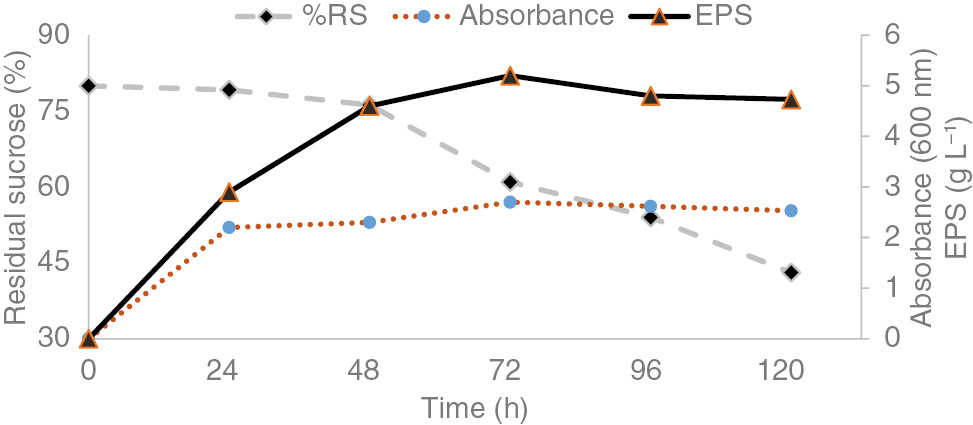

Figure 1 shows fermentation profile of EPS-producing plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) strain (M22) isolated from mung bean root surface and grown in MY complex medium containing 2% w/v sucrose initial concentration, 5 days incubation at 32°C with 220 rpm orbital shaking. Maximum growth (OD600=2.7) was observed after 72 h under these conditions. Sucrose catabolism accumulated (5.2 g L−1) EPS after 72 h. The kinetics revealed that EPS were mainly excreted during exponential growth with a slight contribution during the early stationary phase and degraded during the late stationary phase.

Profile of growth and EPS production by rhizobacterial strain in MY complex medium regarding sucrose consumption.

The effects of several cultural parameters i.e. incubation time (0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h), temperature (12, 22, 32 and 42°C), shaking speed (0, 100, 200 and 300 rpm) and oligosaccharides (sucrose, maltose and lactose) concentration (0, 1, 2, 5, 7 and 10%) as nourishment were tested to search out ideal conditions for strain’s EPS synthesis. Bacterial biomass and EPS production were counted maximum with 2% sucrose than higher concentrations, even 7–10% inhibited bacterial growth and EPS secretion. EPS were also detected in absence of carbon source. PGPR strain utilized every carbon source for growth-producing EPS but the efficiency of sucrose was highest. EPS contents were also calculated maximum at 32°C with 200 rpm orbital shaking, while 12, 22 and 42°C temperatures and static, 100 and 300 rpm shaking significantly inhibited bacterial growth with lesser EPS yields (Table 1).

Exopolysaccharide production of PGPR strain at different growth conditions.

| Incubation time (hours)a | Incubation temperature (°C)b | |||||||||||

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | 120 | 0 | 12 | 22 | 32 | 42 | ||

| EPS (g L−1) | 0 | 2.9 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.73 | 0.03 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 0.08 | |

| Shaking speed (rpm)c | Maltose | |||||||||||

| 0 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 10 | ||

| EPS (g L−1) | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.64 | 1.89 | 3.14 | 1.32 | 0.12 | 0 | |

| Sucrose | Lactose | |||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 10 | |

| EPS (g L−1) | 0.7 | 2.16 | 3.98 | 1.14 | 0 | 0 | 0.59 | 1.13 | 1.86 | 1.88 | 0.23 | 0 |

aLab environment, MY complex medium and hand shaking after 6 h. bMY complex medium, hand shaking and sample collection after 72 h. c72 h incubation and 32°C temperature.

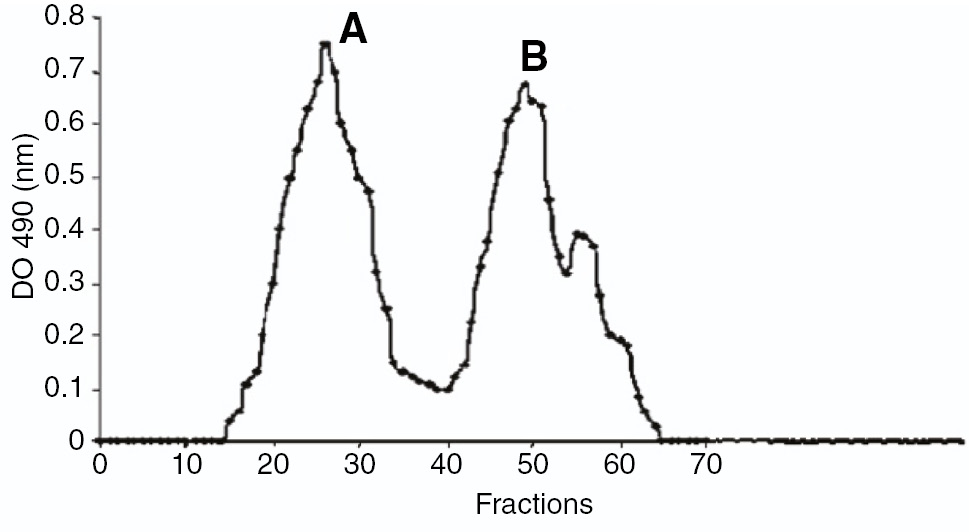

Chemical composition

EPS excreted by PGPR strain was heteropolysaccharide that was mainly composed of carbohydrates (40% w/w), also containing other organics i.e. acetyl residues (0.8–2% w/w), proteins (1–2% w/w) and more than 50% inorganic fraction. The polymer was strongly adsorbed onto anion exchange QMA Sep-Pak cartridge referring its strong anionic nature and to assess charge distribution polymer was loaded on anion exchange column and eluted using linear ionic strength gradient (Figure 2). Two chromatographic peaks as output attested the presence of at least two species (glucose 29% and mannose 52% w/w) and very small quantity of rhamnose (0.5% w/w).

Anion exchange chromatogram of the EPS synthesized by Rhizobacterial strain.

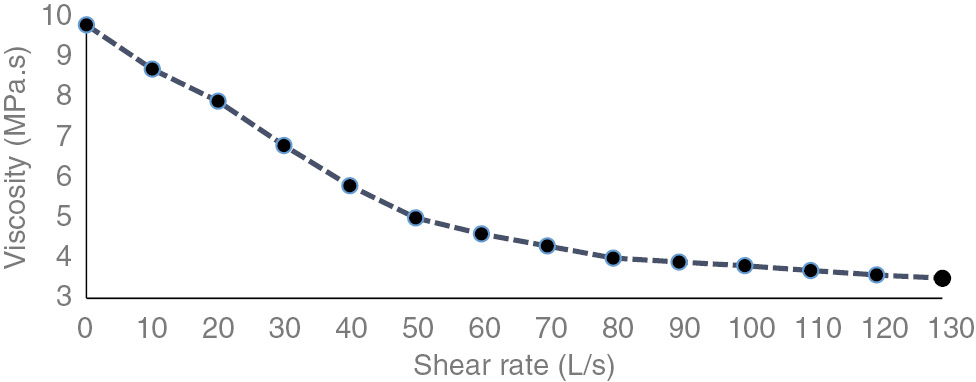

Rheological behaviour of EPS

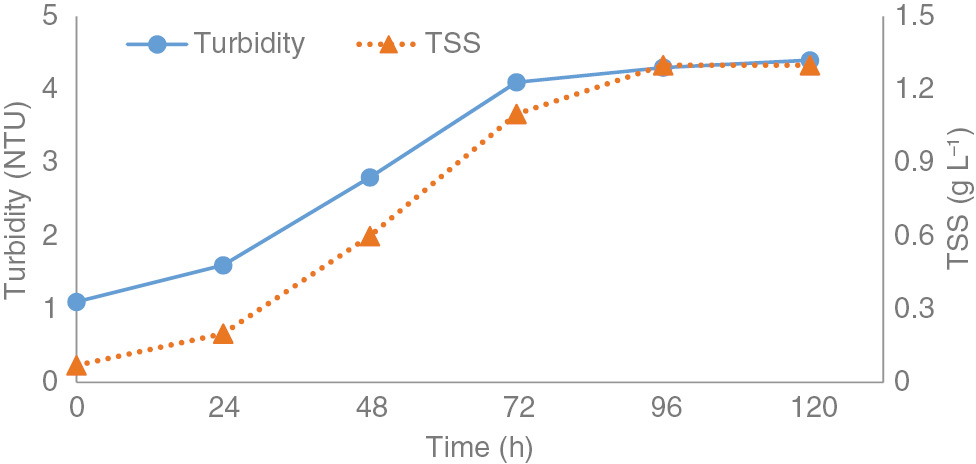

Viscosity of EPS aqueous solutions over a range of shear rates was measured to assess the rheological characteristics of EPS. The concomitant decreasing trend of viscosity with shear rate shows pseudoplastic character of EPS solutions (Figure 3). EPS did not form viscous solutions. Particle suspension produces turbid solutions. Stationary to exponential growth the suspended solids in solution increase that resulted in more turbid solution while in decline phase there is stagnant suspension (Figure 4).

Viscosity of 0.5% w/v solutions of EPS synthesized by Rhizobacterial strain.

Turbidity and total suspended solids in 0.5% w/v solutions of EPS synthesized by Rhizobacterial strain.

Exopolysaccharide production of different rhizobacterial strains

Rhizobacterial strains selected on the basis of optical densities and mucoid shiny appearances were then incubated at 32°C for 72 h. Exopolymer secretions of these bacterial strains have been presented in (Table 2).

Characteristics of exopolysaccharides produced by different PGPR strains.

| Strains | EPS | EPS chemical composition (g L−1) | Monosaccharides (g L−1) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (g L−1) | Carbohydrates | Proteins | Acetyl residues | Sulfates | Glucose | Mannose | Rhamnose | Galactose | Arabinose | Xylose | Fucose | |

| M1 | 2.868 | 1.093 | 0.17 | 0.81 | 1.106 | 0.310 | 0.402 | 0.163 | 0.188 | ND | ND | ND |

| M2 | 5.274 | 3.458 | 0.09 | 0.183 | 11.3 | 1.468 | 1.578 | 0.130 | 0.184 | ND | 0.03 | ND |

| M3 | 4.76 | 2.783 | 0.127 | 0.497 | 6.5 | 1.293 | 1.20 | 0.083 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.05 | ND |

| M5 | 3.871 | 1.771 | 0.243 | 1.421 | 0.7 | 0.518 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.01 | ND | ND |

| M9 | 4.092 | 0.747 | 0.231 | 1.226 | 2.325 | 0.21 | 0.304 | 0.11 | 0.09 | ND | ND | ND |

| M11 | 6.424 | 4.119 | 0.109 | 1.449 | 4.32 | 1.983 | 1.756 | 0.156 | ND | ND | 0.209 | 0.04 |

| M14 | 1.289 | 0.263 | 0.35 | 1.323 | 6.169 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.08 | ND | 0.01 | 0.04 | ND |

| M15 | 1.006 | 0.335 | 0.01 | 0.9 | 5.33 | 0.11 | 0.108 | ND | ND | ND | 0.02 | 0.023 |

| M16 | 4.49 | 2.309 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 2.171 | 0.878 | 0.9 | 0.36 | ND | 0.114 | ND | ND |

| M19 | 5.534 | 3.571 | 0.022 | 2.051 | 3.120 | 1.108 | 1.81 | 0.164 | ND | 0.03 | ND | ND |

| M21 | 1.867 | 1.031 | 0.391 | 0.252 | 4.624 | 0.287 | 0.37 | 0.302 | 0.07 | ND | ND | ND |

| M22 | 6.831 | 4.512 | 0.199 | 1.101 | 8.597 | 1.87 | 2.01 | 0.206 | 0.03 | ND | 0.20 | ND |

| M24 | 2.525 | 0.702 | 0.11 | 1.839 | 11.501 | 0.11 | 0.257 | 0.19 | ND | ND | ND | 0.152 |

ND, not detected.

Exopolymers amounted 6.83 (g L−1) were found in the secretions of M22 that was 0.4, 1.3 and 1.54 g more than M11, M19 and M2 but was noticeably greater than all of the other strains. These EPSs majorly constituted of saccharide units as 4.51 g of carbohydrates were observed out of 6.83 g released by M22 followed by 4.12, 3.57 and 3.46 g in M19 and M3, respectively. Quantification of monosaccharide fractions (Glucose, Mannose, Rhamnose, Galactose, Arabinose, Xylose and Fucose) is presented in Table 2 that elaborates sizable quantities of glucose, mannose and rhamnose while traced or non-detectable contents of galactose, arabinose, xylose and fucose.

Polyamines were fractionated 0.39 g L−1 in M21 secretions in continuity with M14 (0.35 g L−1) and were markedly higher in contents than all other stains. Residues of acetyls were found highest 2.05 g L−1 in M19 that were strikingly similar to M24 (1.85 g L−1) but were pointedly greater in amounts than other strain secretions. Inorganic fraction i.e. sulfate was found 11.5 and 11.3 g L−1 in the secretions of M24 and M2 that were suggestively greater in contents than all other strains.

Discussion

We have studied EPS synthesis by PGPR species. Our results indicated a close association of growth with EPS production, since their excretion was mainly during exponential growth, although a slight continuation during stationary phase. EPS clings to cell surface during growth phase but released to medium during the stationary phase that is evident from our results. Culture medium possesses maximum EPS contents after 72 h of incubation during exponential growth that got declined during static growth, probably because of enzymatic degradation. These results do not comply with previous workers presenting different nutritional requirements of bacteria for EPS release [26, 27]. Nevertheless, conditions leading to maximized growth and EPS yield were (2% w/v sucrose as a carbon source, 32°C temperature and 200 rpm orbital shaking speed).

EPS chemical composition is not being affected by cultural conditions but production declines with unfavorable conditions. Studies of the effect of growth conditions on polymer’s monomer composition revealed that EPS sugar composition is also dependent upon carbon source [28], kinetic and physicochemical parameters [29]. These studies also reflected no influence of growth conditions on relative proportion of sugars in EPS. Degest et al. [30] also found no variation in sugar composition of EPS produced by Lactobacillus sakei using various carbon sources. Arias et al. [31] stated variation in monosaccharide ratios secreted by Halomonas maura with changing fermentation conditions without changing types of sugars in EPS.

The bacterial EPS described until now are majorly composed of a single fraction having molecular weights between 2×104 and 2×107 [31, 32], although Idiomarina spp. contain two fractions. Both fractions in EPS are within the range previously described bacterial EPSs. Low molecular weight of smaller fraction, (1.5×104), explains low viscosity of aqueous preparations because EPS molecular mass distribution greatly influences solution’s rheology.

Inorganics like sulfate and phosphates in EPS are of special importance imparting specific biomedical properties to most EPS [33]. For example, in the native state EPS produced by Alteromons infernus are inert, their potent biomedical capability resulting from over-sulphation.

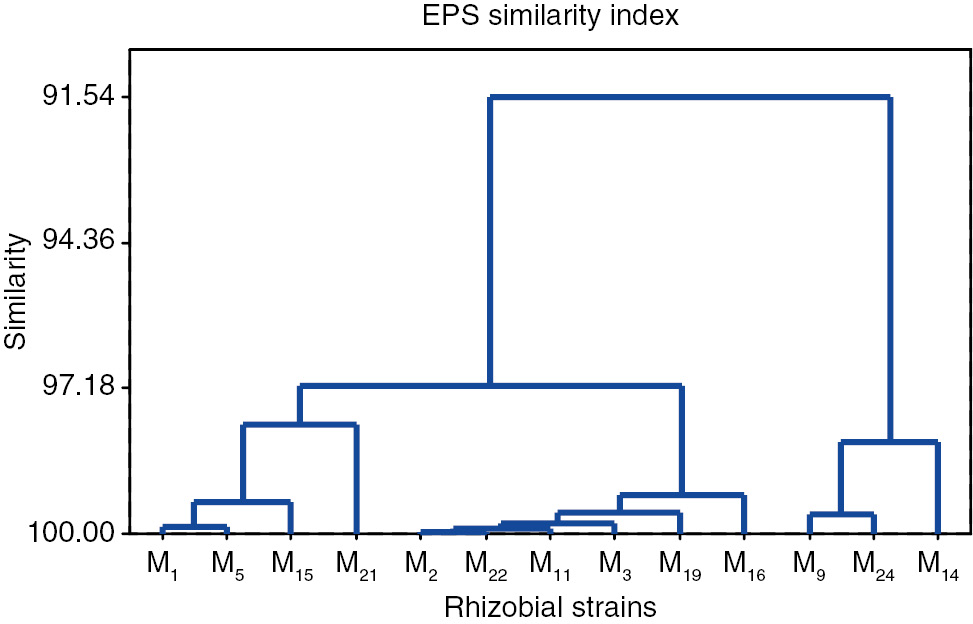

All rheo-chemical parameters were analyzed together using multivariate technique (Cluster analysis). Six (M2, M3, M11, M16, M19, and M22) rhizobacterial strains have been indicated in dendrogram showing maximum EPS yielding potential (Figure 5).

Similarity index of PGPR strains on the basis of EPS production and composition.

Solute movement within the soil is one of the major factors responsible for plant growth, that is dependent upon solution’s viscosity. More viscous solutions have lesser movement, hence reducing their approach to plant root. EPS solutions having least viscosity allows more solute transport and will ultimately result in better growth. Suspended particles result in clogging of soil micropores, due to that reason soil water retention capacity and root penetration capacity got reduced.

Conclusion

Six strains (M2, M3, M11, M16, M19, and M22) secreted noticeably greater amounts of exopolymers than other strains. Organic nature and pseudoplasticity of these exopolymers helps in soil structural restoration, sulfates and phosphates helps in heavy metals detoxication.

References

1. Kanmani P, Kumar RS, Yuvaraj N, Paari KA, Pattukumar V, Arul V. Production and purification of a novel exoploysaccharide from lactic acid bacterium Streptococcus phocae PI80 and its functional characteristics activity in-vitro. Bioresour Technol 2011;102:4827–33.10.1016/j.biortech.2010.12.118Suche in Google Scholar

2. Castellane TC, Lemos MV, Lemos EG. Evaluation of the biotechnological potential of Rhizobium tropici strains for exopolysaccharide production. Carbohydr Polym 2014;111:191–7.10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.04.066Suche in Google Scholar

3. Sutherland IW. Microbial polysaccharides from gram-negative. Int Dairy J Barking 2011;11:663–74.10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00112-1Suche in Google Scholar

4. Downie JA. The roles of extracellular proteins, polysaccharides, and signals in the interactions of rhizobia with legume roots. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2010;34:150–70.10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00205.xSuche in Google Scholar

5. Whiteld C, Valvano MA. Biosynthesis and expression of cell surface polysaccharides in Gram-negative bacteria. Adv Micro Physiol 1993;35:135–246.10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60099-5Suche in Google Scholar

6. Czaczyk K, Myszka K. Biosynthesis of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and its role in microbial biofilm formation. Polish J Environ Studies 2007;16:799–806.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Patil SV, Bathe GA, Patil AV, Patil RH, Salunkea BK. Production of bioflocculant exopolysaccharide by Bacillus subtilis. Adv Biotech 2009;8:14–7.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Bender J, Eaton SR, Ekanemesang UM, Phillip P. Characterization of metal-binding bioflocculants produced by cyanobacterial component of mixed microbial mats. Appl Environ Microbial 1994;60:2311–5.10.1128/aem.60.7.2311-2315.1994Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Wang Y, Li C, Liu P, Ahmed Z, Xiao P, Bai X. Physical characterization of exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus plantarum KF5 isolated from Tibet Kefir. Carbohydr Polym 2010;82:895–903.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.06.013Suche in Google Scholar

10. Huang KH, Chen BY, Shen FT, Young CC. Optimization of exopolysaccharide production and diesel oil emulsifying properties in root-nodulating bacteria. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2012;28:1367–73.10.1007/s11274-011-0936-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Diao Y, Xin Y, Zhou Y, Li N, Pan X, Qi S, et al. Extracellular polysaccharide from Bacillus sp. strain LBP32 prevents LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages by inhibiting NF-kB and MAPKs activation and ROS production. Int Immunopharmacol 2014;18:12–9.10.1016/j.intimp.2013.10.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Freitas F, Alves VD, Reis MA. Advances in bacterial exopolysaccharides: from production to biotechnological applications. Trends Biotechnol 2011;29:388–98.10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.03.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Han Y, Liu E, Liu L, Zhang B, Wang Y, Gui M, et al. Rheological, emulsifying and thermostability properties of two exopolysaccharides produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LPL061. Carbohydr Polym 2015;115:230–7.10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.08.044Suche in Google Scholar

14. Zhou F, Wu Z, Chen C, Han J, Ai L, Guo B. Exopolysaccharides produced by Rhizobium radiobacter S10 in whey and their rheological properties. Food Hydrocoll 2014;36:362–8.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.08.016Suche in Google Scholar

15. Patel AK, Michaud P, Singhania RR, Soccol CR, Pandey A. Polysaccharides from probiotics: new developments as food additives. Food Tech Biotech 2010;48:451–63.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Kim Y, Kim JU, Oh S, Kim YJ, Kim M, Kim SH. Technical optimization of culture conditions for the production of exopolysaccharide (EPS) by Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 9595. Food Sci Biotech 2008;17:587–93.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Wu CY, Liang ZC, Lu CP, Wu SH. Effect of carbon and nitrogen sources on the production and carbohydrate composition of exopolysaccharide by submerged culture of Pleurotus citrinopileatus. J Food and Drug Anal 2008;16:61–7.10.38212/2224-6614.2364Suche in Google Scholar

18. Borgio JF, Bency BJ, Ramesh S, Amuthan M. Exopolysaccharide production by Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2063, Pseudomonas aeruginosa NCIM 2862 and Streptococcus mutans MTCC 1943 using batch culture in different media. African J Biotech 2009;9:5454–7.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Moraine RA, Rogovin P. Kinetics of polysaccharide B-1459 fermentation. Biotech Bioeng 1966;8:511–24.10.1002/bit.260080405Suche in Google Scholar

20. Li Y, Zhang C, Fan Y, Liu L, Li P, Han Y. Optimization of fermentation conditions for exopolysaccharide production by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens LPL061. Food Sci 2013;34:185–9 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

21. Xu R, Shen Q, Ding X, Gao W, Li P. Chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of an exopolysaccharide fraction isolated from Bifidobacterium animalis RH. Eur Food Res Technol 2011;232:231–40.10.1007/s00217-010-1382-8Suche in Google Scholar

22. Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem 1956;28:350–6.10.1021/ac60111a017Suche in Google Scholar

23. Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–54.10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3Suche in Google Scholar

24. McComb EA, McCready RM. Determination of acetyl in pectin and in acetylated carbohydrate polymers. Anal Chem 1957;29:819–21.10.1021/ac60125a025Suche in Google Scholar

25. Chaplin MF. A rapid and sensitive method for the analysis of carbohydrate components in glycoproteins using gas-liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem 1982;123:336–41.10.1016/0003-2697(82)90455-9Suche in Google Scholar

26. Cheirslip B, Shimizu H, Shioya S. Modelling and optimization of environmental conditions for kefiran production by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2001;57:639–43.10.1007/s00253-001-0846-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Gorret AU, Maubois N, Engasser JL, Ghoul JM. Study of the effects of temperature pH and yeast extract on growth and exopolysaccharide production by Propionibacterium acidipropionici on milk microfiltrate using a response surface methodology. J Appl Microbiol 2001;90:788–96.10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01310.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Kojic M, Vujcic M, Banina A, Cocconcelli P, Cerning J, Topisirivic L. Analysis of exopolysaccharide production by Lactobacillus casei CG11 isolated from cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol 1992;58:4086–8.10.1128/aem.58.12.4086-4088.1992Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Grobben GJ, Sikkema J, Smith MR, de Bont JA. Production of extracellular polysaccharides by Lactobacillus delbrueckii NCFB 2772 grown in a chemically defined medium. J Appl Bacteriol 1995;79:103–7.10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03130.xSuche in Google Scholar

30. Degeest B, Janssens B, De Vuyst L. Exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis by Lactobacillus sakei 0–1: production kinetics enzyme activities and EPS yields. J Appl Microbiol 2001;91:470–7.10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01404.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Arias S, del Moral A, Ferrer MR, Tallón R, Quesada E, Bejar V. Mauran an exopolysaccharide produced by the halophilic bacterium Halomonas maura with a novel composition and interesting properties for biotechnology. Extremophiles 2003;7:319–26.10.1007/s00792-003-0325-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Mata JA, Béjar V, Bressollier P, Tallon R, Urdaci MC, Quesada E. Characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by three moderately halophilic bacteria belonging to the family Alteromonadaceae. J Appl Microbiol 2008;105:521–8.10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03789.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Wu XZ, Chen D. Effects of sulfated polysaccharides on tumour biology. West Indian Med J 2006;55:270–3.10.1590/S0043-31442006000400009Suche in Google Scholar

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Effects of calcium hydroxide and N-acetylcysteine on MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in LPS-stimulated macrophage cell lines

- Synthesis of fused 1,4-dihydropyridines as potential calcium channel blockers

- Optimization of fermentation conditions for efficient ethanol production by Mucor hiemalis

- Covalent immobilization of an alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis

- Major biological activities and protein profiles of skin secretions of Lissotriton vulgaris and Triturus ivanbureschi

- Optimized production, purification and molecular characterization of fungal laccase through Alternaria alternata

- Adsorption of methyl violet from aqueous solution using brown algae Padina sanctae-crucis

- Protective effect of dexpanthenol (vitamin B5) in a rat model of LPS-induced endotoxic shock

- Purification and biochemical characterization of a β-cyanoalanine synthase expressed in germinating seeds of Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench

- Molecular cloning and in silico characterization of two alpha-like neurotoxins and one metalloproteinase from the maxilllipeds of the centipede Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans

- Improvement of delta-endotoxin production from local Bacillus thuringiensis Se13 using Taguchi’s orthogonal array methodology

- Enhancing vitamin B12 content in co-fermented soy-milk via a Lotka Volterra model

- Species and number of bacterium may alternate IL-1β levels in the odontogenic cyst fluid

- Rheo-chemical characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria

- Benzo(a)pyrene degradation pathway in Bacillus subtilis BMT4i (MTCC 9447)

- Indices

- Reviewers 2018

- Yazar Dizini/Author Index

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Effects of calcium hydroxide and N-acetylcysteine on MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 in LPS-stimulated macrophage cell lines

- Synthesis of fused 1,4-dihydropyridines as potential calcium channel blockers

- Optimization of fermentation conditions for efficient ethanol production by Mucor hiemalis

- Covalent immobilization of an alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis

- Major biological activities and protein profiles of skin secretions of Lissotriton vulgaris and Triturus ivanbureschi

- Optimized production, purification and molecular characterization of fungal laccase through Alternaria alternata

- Adsorption of methyl violet from aqueous solution using brown algae Padina sanctae-crucis

- Protective effect of dexpanthenol (vitamin B5) in a rat model of LPS-induced endotoxic shock

- Purification and biochemical characterization of a β-cyanoalanine synthase expressed in germinating seeds of Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench

- Molecular cloning and in silico characterization of two alpha-like neurotoxins and one metalloproteinase from the maxilllipeds of the centipede Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans

- Improvement of delta-endotoxin production from local Bacillus thuringiensis Se13 using Taguchi’s orthogonal array methodology

- Enhancing vitamin B12 content in co-fermented soy-milk via a Lotka Volterra model

- Species and number of bacterium may alternate IL-1β levels in the odontogenic cyst fluid

- Rheo-chemical characterization of exopolysaccharides produced by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria

- Benzo(a)pyrene degradation pathway in Bacillus subtilis BMT4i (MTCC 9447)

- Indices

- Reviewers 2018

- Yazar Dizini/Author Index