Abstract

Classification is a core task in pattern recognition, with broad applications in image processing, speech recognition, and medical diagnostics. Traditional neural networks often suffer from difficulties in parameter optimization and local optima, while the performance of approximate logical dendritic neuron models depends heavily on proper parameter configuration. To address these issues, this paper proposes a Feature-Guided Adaptive Differential Evolution algorithm, which incorporates feature-guided mechanisms, adaptive parameter control, and multi-strategy mutation to enhance the standard differential evolution framework. The algorithm is applied to optimize the dendritic neuron model’s parameters, providing a more effective and robust solution for intelligent classification in complex data environments. This approach contributes to the development of reliable optimization strategies in intelligent systems and has promising application potential.

1 Introduction

Against the backdrop of rapid development in artificial intelligence and data science, classification problems, as the core task in pattern recognition, are widely applied in areas such as image processing, speech recognition, and medical diagnosis. It plays a key role in object detection, facial recognition, speech-to-text, and disease screening, and is also applied in financial risk control and industrial detection [1,2]. Neural networks, with their powerful nonlinear modeling capabilities, have shown significant advantages in solving complex pattern recognition problems and have become one of the mainstream methods for classification tasks. However, traditional neural networks still face many challenges in practical applications, such as complex parameter optimization processes, susceptibility to local optima, and sensitivity to initial values, which severely limit their generalization ability and robustness. To overcome these limitations, the Approximate Logical Dendritic Neuron Model (ALDNN) has attracted increasing attention in recent years. Inspired by the functional characteristics of dendritic structures in biological neural systems, this model introduces local logical operations, exhibiting stronger adaptability in complex feature representation and information integration [3]. Although ALDNN has achieved promising results in classification tasks, its performance largely depends on the precise configuration of various parameters, such as weights and thresholds. Common parameter optimization methods, such as gradient descent and random search, often find it difficult to find the global optimal solution in high-dimensional nonlinear spaces, and tend to converge slowly or stagnate when dealing with multimodal and constrained problems [4]. In recent years, Differential Evolution (DE) algorithms have been widely applied to neural network parameter optimization due to their high search efficiency, simple parameter settings, and suitability for non-convex optimization problems [5,6]. Nevertheless, standard DE algorithms still have limitations in handling high-dimensional complex tasks, such as the lack of dynamic perception of the population evolution state, leading to the loss of population diversity and premature convergence. Moreover, most existing improvements to DE lack adaptive strategy selection mechanisms based on problem-specific features, making it difficult to effectively balance global exploration and local exploitation. These issues constitute the main research gap addressed in this study.

Given this, this study proposes a Feature-Guided Adaptive Differential Evolution (FG-ADE) algorithm based on feature guidance. This algorithm improves the traditional DE algorithm by dynamically guiding the evolution process of the population, using population feature information to select appropriate mutation strategies and parameter adjustment mechanisms. The aim of this study is to use FG-ADE to optimize the parameters of ALDNM, improve its accuracy and generalization ability in classification tasks, and meet the demand for efficient classification of complex data in practical scenarios.

2 Related works

The neuron model, as a key technology for simulating the information processing mechanism of biological neurons, has significant importance in fields such as pattern recognition, feature extraction, and intelligent decision-making. It provides strong support for solving complex data classification and feature analysis problems through nonlinear information integration and flexible computing capabilities. Therefore, many scholars have deeply researched neural models. Ji et al. put forward a competitive decomposition Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) to address the performance limitations of traditional MOEAs in Dendritic Neural Model (DNM) architecture search problems. By decomposing the problem and sharing overlapping regions to propagate selection pressure, the architecture search performance of DNM and its hardware implementation were optimized. It also improved the classification performance of DNM, making it more competitive among many machine learning methods [7]. Georgescu et al. proposed a novel artificial neuron model and activation function for the classification problem of linearly inseparable data. It improved classification performance by enabling individual neurons to learn nonlinear decision boundaries and further replacing the standard neuron model with pyramid neurons and top dendritic activations [8]. Zhang and Yan proposed using an improved selection operator DE algorithm to train the model to address the limited classification performance of ALDNM due to the training effectiveness of the learning algorithm. The improved algorithm could solve the problem of easy evolutionary stagnation, thereby achieving optimization of model training performance [9]. Kölemen proposed to use the DNM Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to predict the seasonal export volume of hazelnut in Türkiye, and used the training algorithm based on the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm for training. This model has achieved optimized prediction for the problem, and its performance has certain advantages compared to other ANNs used in the literature [10].

The DE algorithm is an efficient optimization method with global search capability and algorithm simplicity. It is an important tool for solving nonlinear optimization problems, widely used in parameter optimization and complex system solving, providing important support for the improvement of intelligent algorithm performance. Therefore, research on improving the DE algorithm has become a hot topic. Zhang et al. proposed an algorithm combining chaotic fruit fly swarm and DE to address the potential issues of poor convergence performance or Susceptibility to Local Optima (STLO) when dealing with intricate optimization issues. This algorithm introduced chaos initialization and DE, improving the balance between global search and reinforcement search, thereby optimizing the convergence velocity and precision of the fruit fly swarm algorithm [11]. Chakraborty et al. proposed improvements in parameter adaptation, setting, and mutation strategies for the application and optimization needs of the DE algorithm in different problems. Meanwhile, they explored its hybrid and multi-objective variants to optimize the performance of the DE algorithm in academic and industrial problem-solving [12]. Ibrahim and Tawhid proposed an efficient strategy combining the artificial algae algorithm and DE for the job shop scheduling problem, introducing the DE operator to update the movement mode of the algae population and enhance the reinforcement ability of the artificial algae algorithm. It also increased randomness through DE cross operation, thereby optimizing the scheduling solution effect [13]. Thakare et al. proposed using probabilistic PSO sequence DE for optimal feature selection in the classification of EEG data from epilepsy patients, optimizing the performance of the classifier. With the assistance of this algorithm, the accuracy of the support vector machine reached 98.34% [14]. Tiwari et al. proposed an improved Genetic Algorithm (GA) that combines the PSO strategy to address the problems of low population diversity, insufficient exploration ability, and susceptibility to local optima in nonlinear and non-convex engineering optimization problems of GAs. This method effectively enhanced the global search ability and local development efficiency of the algorithm by introducing new mutation mechanisms, crossover rates, and selection strategies, thereby achieving excellent performance in multiple complex nonlinear scheduling and engineering optimization tasks [15]. Zhao et al. proposed a multi-objective discrete DE algorithm for the energy consumption optimization problem in the scheduling of distributed blocking flow workshops under the background of intelligent manufacturing. Through collaborative initialization, a discrete mutation crossover operator, and local search strategy based on operational knowledge, the algorithm’s ability to solve in the discrete scheduling space was enhanced while optimizing total energy consumption and completion time [16].

In summary, existing research has made some progress in optimizing the structure of neural models and improving the performance of DE algorithms, but the parameter optimization of neural models still faces problems of insufficient efficiency and STLO. The dynamic adjustment and feature utilization ability of the DE algorithm in high-dimensional complex problems still need improvement. Therefore, this study proposes an ALDNM based on FG-ADE. The innovation lies in the introduction of the FG-ADE algorithm, combined with dynamic parameter adjustment and a multi-strategy mutation mechanism, to achieve efficient optimization of neural model parameters and improve the performance and optimization efficiency of classification tasks.

3 Methods and materials

This section provides a detailed explanation of the FG-ADE algorithm and its application in ALDNM. Firstly, the core idea of the FG-ADE algorithm is introduced, including a feature guidance mechanism, adaptive parameter adjustment, and multi-strategy mutation. Subsequently, it is explained how to use the FG-ADE to optimize the weights and threshold parameters of the neural model, to improve the accuracy and efficiency in classification tasks.

3.1 Feature-guided adaptive DE algorithm

ALDNM can effectively cope with feature extraction and complex pattern classification tasks by simulating the logical operations and nonlinear information integration functions of neuronal dendrites. However, its performance is highly dependent on parameter settings and optimization [17]. Due to its strong global search capability, adaptability to nonlinear optimization problems, and simple algorithm, DE can effectively optimize the parameters of ALDNM [18]. However, traditional DE algorithms often face limitations, including Slow Convergence Speed (SCS), STLO, and insufficient population diversity in high-dimensional complex problems [19]. Therefore, this study first proposes an improved DE algorithm, namely FG-ADE, to enhance parameter optimization efficiency and classification performance. FG-ADE has made three major improvements based on the traditional DE algorithm, as shown in Figure 1.

Three improvements of FG-ADE algorithm.

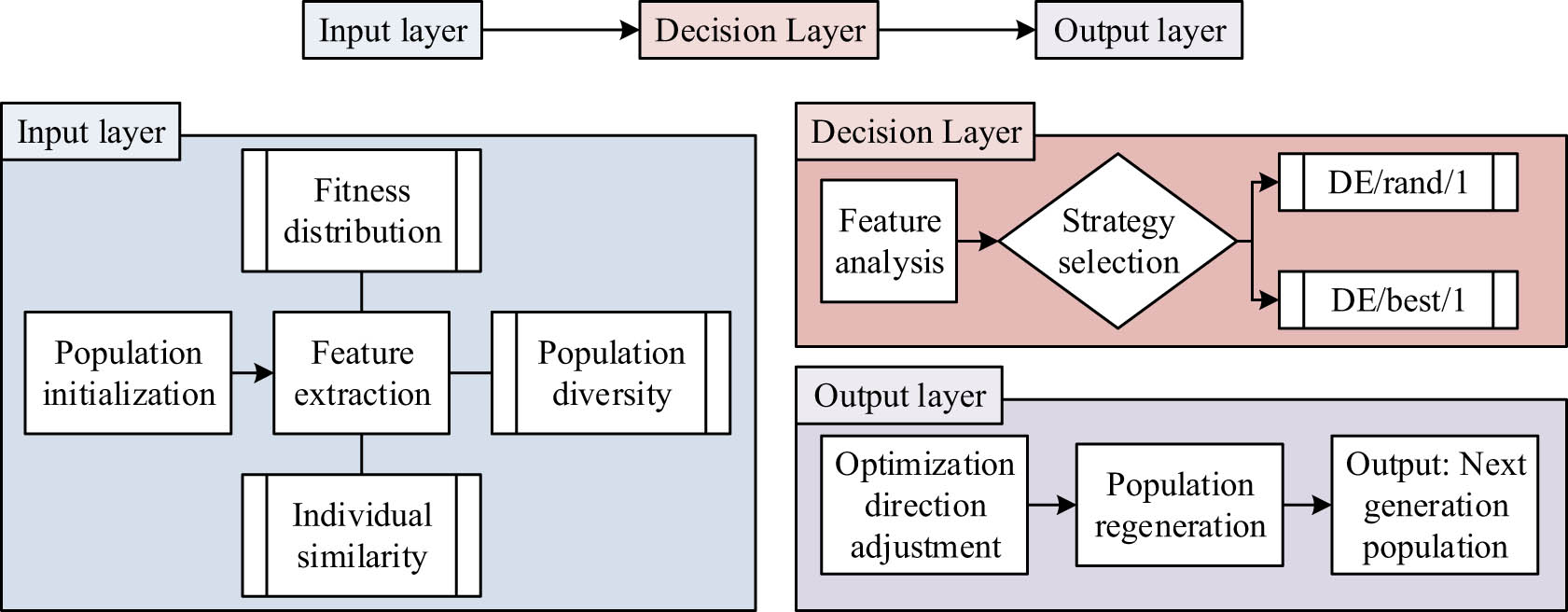

In Figure 1, the three core improvements are feature guidance mechanism, adaptive parameter adjustment, and multi-strategy collaborative mutation. Among them, the feature guidance mechanism dynamically adjusts the optimization direction to improve algorithm efficiency by extracting the fitness distribution and diversity information of the population. Adaptive parameter adjustment adjusts the values of control parameters according to different requirements during the search phase, achieving a balance between global exploration and local development. Multi-strategy collaborative mutation combines multiple mutation strategies to enhance the search ability of the population and accelerate the convergence process. The feature guidance mechanism is the first core improvement of FG-ADE. In this mechanism, population characteristic information is crucial. By analyzing population characteristic information, the current search status can be reflected, which can determine the next optimization direction. The core content is displayed in Figure 2.

The core content of the feature steering mechanism.

In Figure 2, the core of the feature guidance mechanism mainly includes the extraction of population feature information, feature analysis, and dynamic strategy selection. Its essence is to dynamically adjust the optimization direction and mutation strategy by analyzing the fitness distribution, diversity information, and individual similarity of the population. Assuming the current population is

In equation (1),

In equation (2),

In equation (3),

In equation (4),

In equation (5),

In equation (6),

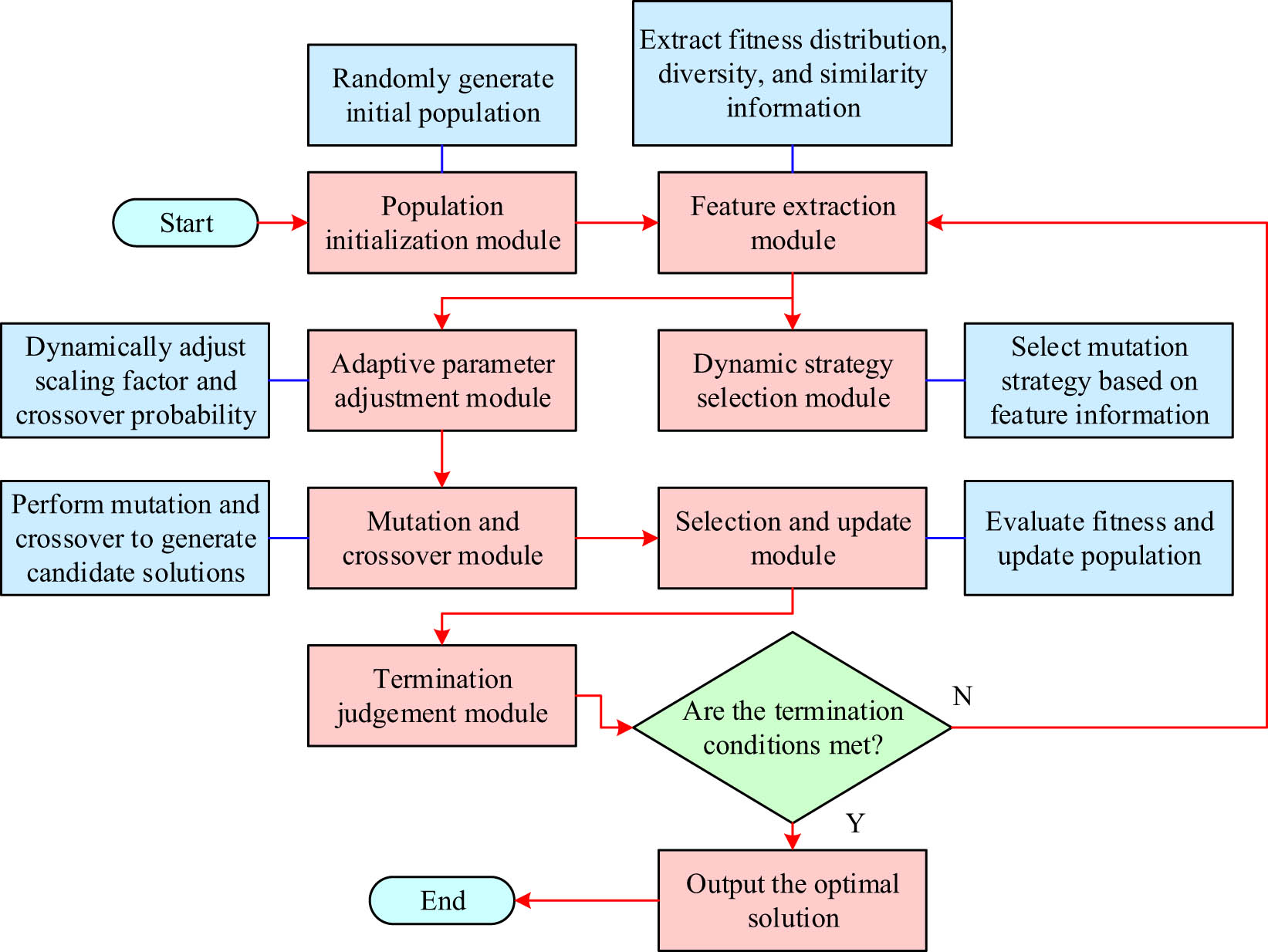

The multi-strategy collaborative mutation introduced in FG-ADE in this study is achieved by dynamically combining DE/rand/1 and DE/best/1 strategies. In the initial stage of optimization, DE/rand/1 is utilized to enhance global search capability, and in the later stage, DE/best/1 is gradually shifted to accelerate convergence. At the same time, by dynamically adjusting the selection probability based on the historical success frequency of statistical strategies, multiple mutation strategies work together to improve the optimization efficiency and adaptability of the algorithm. Combining the three major improvement designs, the final flow of the FG-ADE is exhibited in Figure 3.

Flow diagram of FG-ADE algorithm.

In Figure 3, FG-ADE first generates an initial population through random initialization and extracts features such as fitness distribution and diversity information of the population. Subsequently, based on the feature-guided mechanism, the optimal mutation strategy is dynamically selected. Combined with the adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism, the scaling factor and crossover probability are flexibly set to balance global exploration and local development capabilities. Furthermore, multiple strategy collaborative mutation operations are utilized to generate new solutions, and individual selection and updating are completed through fitness evaluation. Finally, the optimal solution is output based on the optimization termination condition. The entire process can effectively improve the optimization efficiency of the algorithm through the synergistic effect of three major improvements.

3.2 ALDNM based on FG-ADE

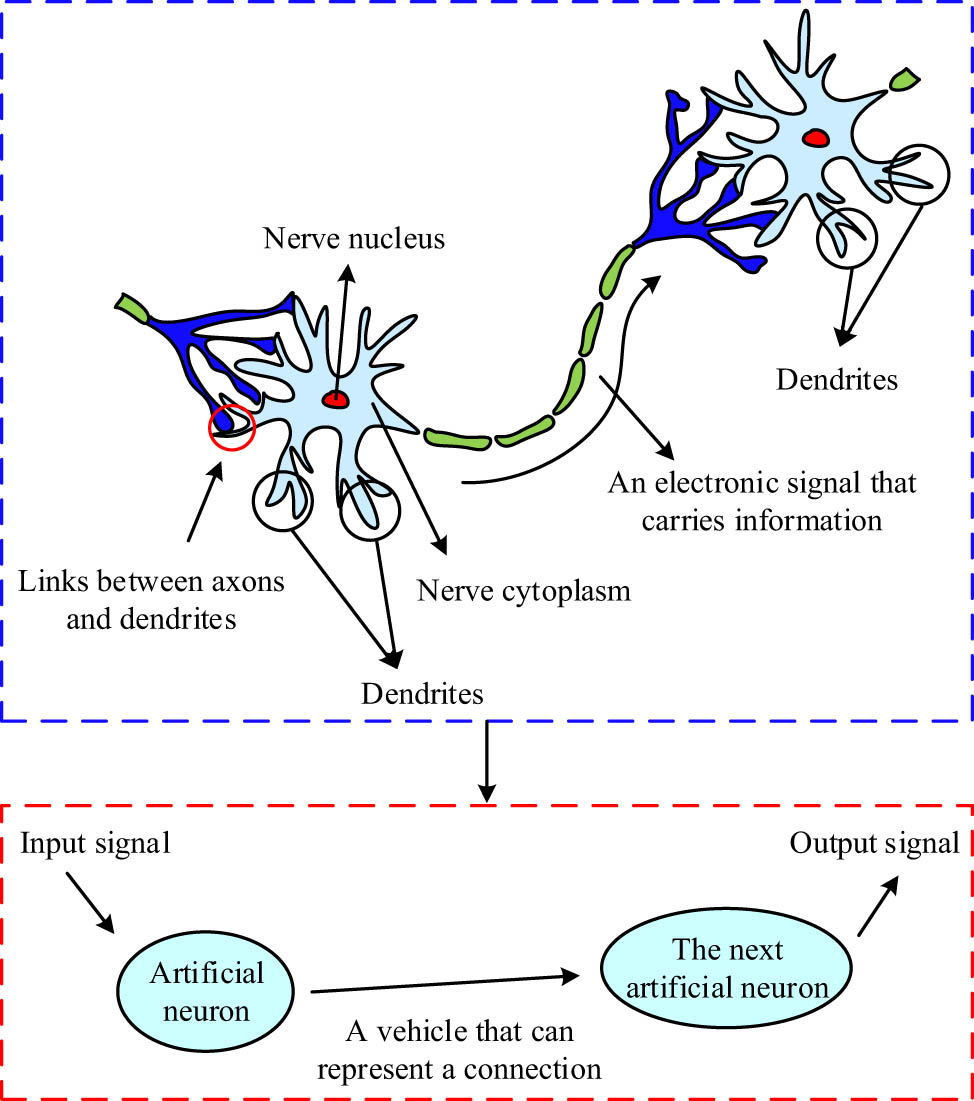

The proposed FG-ADE algorithm solves the problems of SCS, STLO, and insufficient population diversity in traditional DE algorithms for high-dimensional complex problems by introducing a feature guidance mechanism, adaptive parameter adjustment, and multi-strategy collaborative mutation. Therefore, to improve the classification performance of ALDNM and address the shortcomings of low parameter optimization efficiency and STLO, this study applies FG-ADE to ALDNM. To achieve effective application of FG-ADE, it is necessary to first have a deep understanding of the working principle of ALDNM. The working principle of ALDNM is inspired by the dendritic structure of biological neurons, as shown in Figure 4.

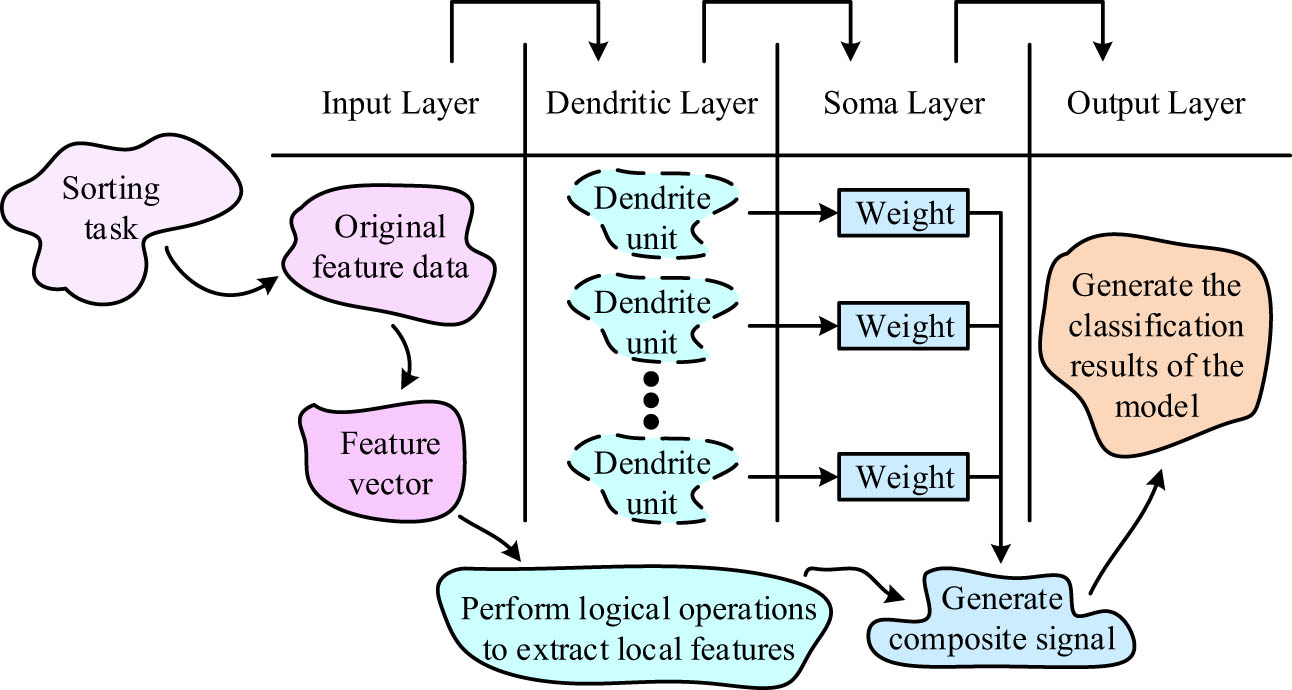

Working principle of the ALDNM.

In Figure 4, the working principle of biological neurons includes signal reception, integration, and transmission. The input signal enters the neuron through dendrites. Dendrites, as the main information receivers, screen and integrate signals from other neurons, and then transmit the processed signals to the cell body [20]. As the core processing unit of information, the cell body weighs and integrates the signals transmitted by dendrites, and transmits the output to the next neuron in the form of electronic signals through axons. Inspired by this, ALDNM not only simulates the working mechanism of biological neurons but also further combines specific mathematical logic operations and optimization processes to enhance classification and feature extraction capabilities. The specific structure of its model is shown in Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the ALDNM.

In Figure 5, ALDNM mainly consists of an input layer, dendritic layer, cytoplasmic layer, and output layer. The functions of each part highly correspond to the signal reception, integration, and transmission processes of biological neurons. In the input layer, the raw feature data are mapped into feature vectors, which are then subjected to logical operations and local feature extraction in the dendritic layer. After weighted integration by the cellular layer, the comprehensive signal is transmitted to the output layer, and the final classification result is generated through the activation function. Assuming the input feature vector is

In equation (7),

In equation (8),

In equation (9),

In equation (10),

In equation (11),

In equation (12),

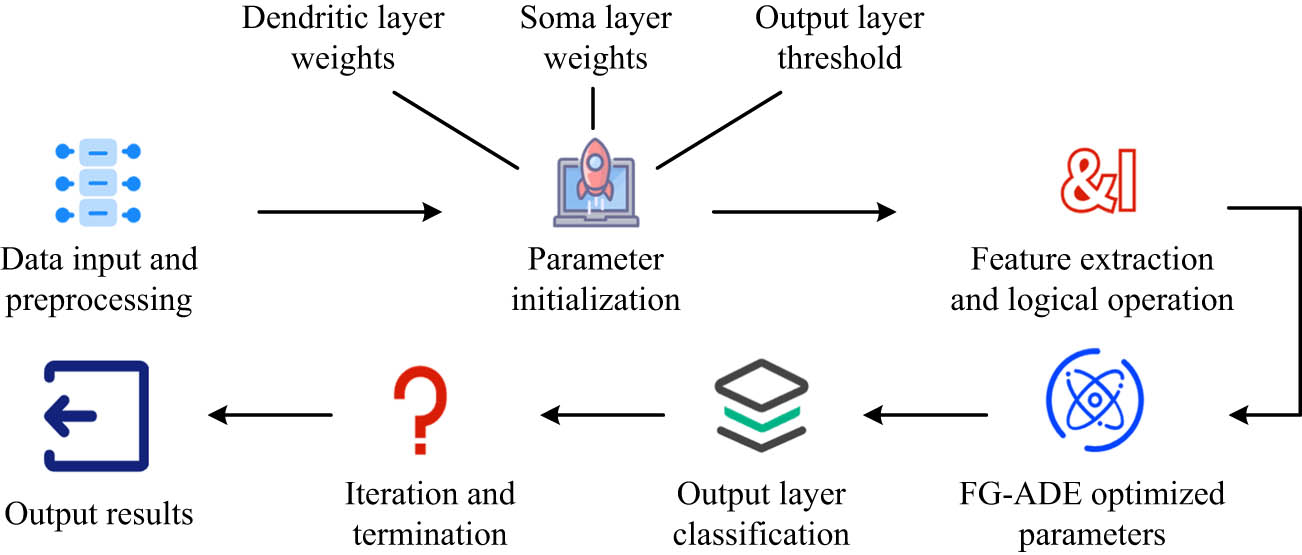

The flow of FG-ADE-based ALDNM used for classification.

In Figure 6, when performing classification tasks based on FG-ADE-optimized ALDNM, the input feature data are first mapped into feature vectors and passed to the dendritic layer to extract local features through logical operations. Subsequently, it weighs and integrates the outputs of dendritic units at the cellular level to generate a comprehensive signal. To improve model performance, FG-ADE adjusts dendritic layer weights, cell body layer weights, and output layer thresholds through feature-guided mechanisms and dynamic optimization strategies, balancing global search and local development capabilities to optimize classification performance. Finally, the model generates classification results through the output layer activation function and evaluates its performance based on test data to ensure excellent performance in complex classification tasks.

4 Results

This section validates FG-ADE and ALDNM based on FG-ADE, verifying their effectiveness and superiority from different perspectives through comparisons, ablation experiments, etc., thereby providing data support.

4.1 Performance verification and analysis of FG-ADE algorithm

The environmental experiments are listed in Table 1.

Software and hardware environment of the experiment

| Category | Configuration item | Specific configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | Processor (CPU) | Intel Core i7-12700K |

| Memory (RAM) | 16GB DDR4 | |

| Storage | 1TB NVMe SSD | |

| Graphics processor (GPU) | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 | |

| Software | Operating system (OS) | Ubuntu 20.04 LTS |

| Programming language | Python 3.8 | |

| Core libraries | NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch, DEAP | |

| Data visualization tools | Matplotlib, Seaborn | |

| Optimization algorithm tools | DEAP (Differential Evolution Algorithm Python) |

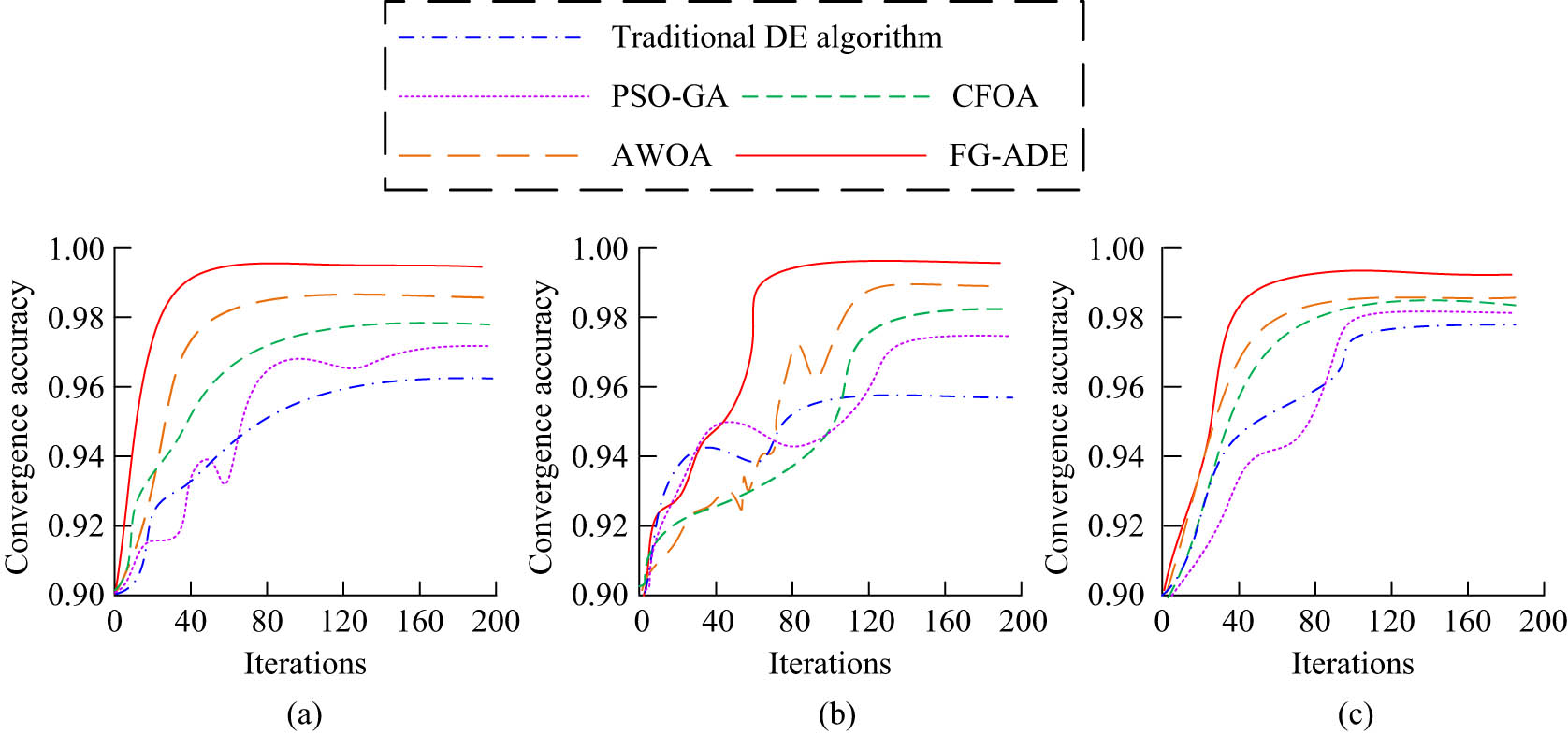

This study first conducts experiments on FG-ADE. In Table 1, the population size is set to 50, the maximum number of iterations is 100, and the initial values of the scaling factor and crossover probability are 0.5 and 0.7, which are dynamically adjusted during the optimization process. The mutation strategy initially adopts random mutation, and gradually shifts to the mutation strategy based on the optima in the later stage. To verify the optimization performance of FG-ADE, four baseline algorithms are selected for comparison: the traditional DE algorithm, the PSO-GA, the Chaotic Fruit Fly Optimization Algorithm (CFOA), and the Adaptive Whale Optimization Algorithm (AWOA). All algorithms are executed on the same hardware and software platform to ensure the fairness and reproducibility of the comparative experiments. The key parameter settings of the baseline algorithms are as follows: The traditional DE algorithm adopts the DE/rand/1/bin strategy, with the scaling factor set to 0.5 and the crossover probability set to 0.7, which are consistent with the initial settings in FG-ADE. In PSO-GA, the particle swarm component uses 30 particles, with an inertia weight of 0.7, and both the personal and social learning factors are set to 1.5. In the GA component, the crossover rate and mutation rate are set to 0.8 and 0.1, respectively. CFOA uses an initial population size of 30, a maximum flight distance of 10, and a step size factor of 0.5, with chaotic behavior introduced via a Logistic map. AWOA employs a linearly decreasing convergence factor from 2 to 0, and incorporates a spiral position update mechanism along with a jump search strategy, with a population size of 30 as well. The typical high-dimensional optimization test functions, namely Rastrigin, Rosenbrock, and Ackley functions, are selected as the test benchmarks for the experiment, as shown in Figure 7.

Performance comparison experiment results of FG-ADE. (a) Rastrigin. (b) Rosenbrock. (c) Ackley.

In Figure 7(a), on the Rastrigin function, the convergence speed of FG-ADE is significantly better than other algorithms, approaching the global optimal solution after about 40 iterations and maintaining stability, with a convergence accuracy of 0.994. In Figure 7(b), FG-ADE exhibits superior local development capability on the Rosenbrock function, with higher convergence accuracy than other algorithms, and reaches the optimal value of 0.997 after about 50 iterations. In Figure 7(c), on the Ackley function, FG-ADE has strong optimization ability in multi-modal complex problems, and its convergence speed and accuracy are also better than the compared algorithms. Therefore, FG-ADE performs better in high-dimensional nonlinear optimization problems. Furthermore, this study conducted ablation experiments on the FG-ADE algorithm, as shown in Table 2.

Ablation experimental results

| Algorithm version | Error | Average fitness value | Final population diversity | Time consumption (s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | I1 | I2 | I3 | ||||

| √ | × | √ | √ | 0.025 | 0.897 | 0.594 | 2.9 |

| √ | √ | × | √ | 0.018 | 0.992 | 0.714 | 3.1 |

| √ | √ | √ | × | 0.012 | 0.994 | 0.628 | 3.2 |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.001 | 0.997 | 0.856 | 3.5 |

In Table 2, I1, I2, and I3 represent three improved designs: feature guidance mechanism, adaptive parameter adjustment, and multi-strategy collaborative mutation. As shown in Table 2, the complete FG-ADE model achieves the best performance in all evaluation metrics, with the lowest error of 0.001, the highest average fitness of 0.997, and the greatest population diversity of 0.856. Removing any single improvement will result in performance degradation, indicating that these three mechanisms have complementary and synergistic effects. It is worth noting that removing the feature-guided mechanism (I1) results in the largest decrease in population diversity, reaching 0.594, and the fitness value also significantly decreases. This is due to the lack of adaptive feedback on population status, which causes the mutation strategy to become less directed and increases the risk of premature convergence. Without the adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism (I2), the average fitness decreases to 0.992, as fixed parameters fail to accommodate the dynamic nature of the search process, especially in later stages. Eliminating the multi-strategy mutation mechanism (I3) reduces the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima, leading to lower diversity and less robust solutions. Due to the additional computation of population analysis and dynamic strategy selection required for each iteration, the complete FG-ADE has a slightly higher time cost of 3.5 s, but the performance improvement proves that the increase in computational overhead is reasonable. These findings highlight the crucial role of all three components in enhancing global search capacity, maintaining diversity, and improving convergence quality, particularly in high-dimensional optimization tasks.

4.2 Validation and analysis of ALDNM

For ALDNM based on FG-ADE, this study chooses the UCI Wine Dataset and MNIST Dataset as data sources. The former has a smaller data scale, containing 178 samples and 13 continuous features, which can be used to verify the performance and stability of the model in multi-class classification tasks. The latter has a larger data scale, containing 70,000 samples and 784 high-dimensional features, which is suitable for testing the classification ability of the model on complex high-dimensional features and large-scale data. To ensure the consistency and reproducibility of the experiments, all datasets are preprocessed prior to use. Specifically, missing values are handled using mean imputation, and all features are normalized using Min-Max scaling to the range [0, 1] to eliminate the impact of differing feature scales on model training.

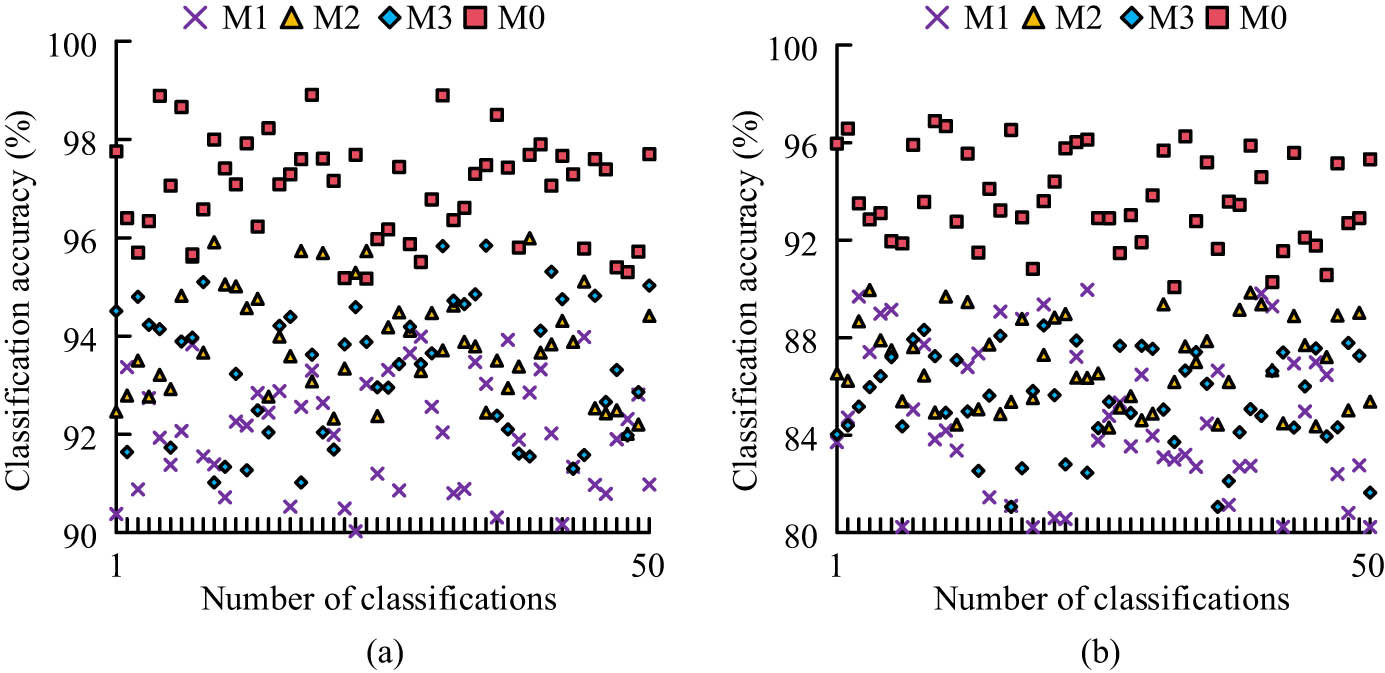

The traditional DE-optimized ALDNM (M1), PSO-GA-optimized ALDNM (M2), and gradient descent-optimized ALDNM (M3) are used as comparison methods, while the research model is M0. Firstly, the model performance in classification tasks is validated, as exhibited in Figure 8.

Comparison of model performance in classification tasks. (a) UCI Wine Dataset. (b) MNIST Dataset.

In Figure 8(a), in the UCI Wine Dataset, the classification accuracy of M1 fluctuates between 90 and 94% in 50 classification tasks, M2 fluctuates between 92 and 96%, M3 fluctuates between 91 and 96%, and M0 fluctuates between 95 and 99%. In a few classification tasks, M0 has lower classification accuracy than M2 or M3, but overall accuracy is higher. In Figure 8(b), in the MNIST Dataset, due to the large amount of data and high feature dimensions, the classification accuracy of all four models has decreased, but M0 still remains between 91 and 97%, showing the best performance. This study thoroughly analyzes the classification performance under different dimensions, as shown in Figure 9.

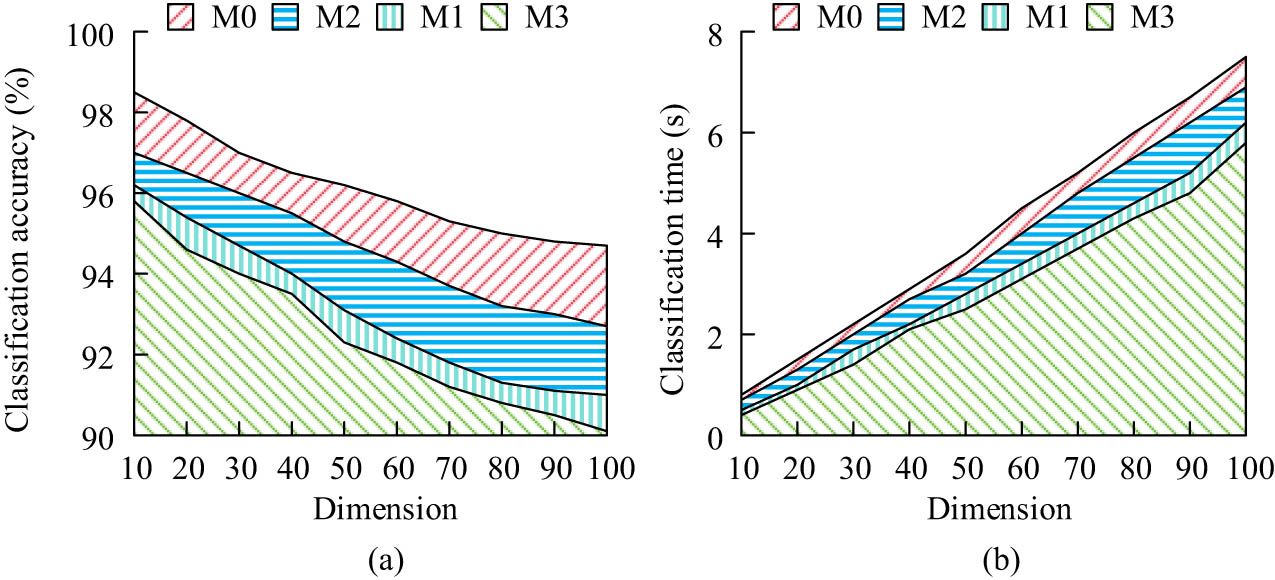

Classification performance in different dimensions: (a) Classification accuracy and (b) classification time.

In Figure 9(a), as the data dimension increases, the classification accuracy of all models decreases. However, M0 has the highest classification accuracy in all dimensions, reaching 98.5% when the dimension is 10 and maintaining 94.7% when the dimension reaches 100 dimensions. The accuracy of M1, M2, and M3 has decreased significantly, and their overall performance is far inferior to M0. In Figure 9(b), as the dimension increases, the time consumption of all models shows a gradually increasing trend. Compared to other models, M0 has a higher time consumption, but it remains within an acceptable range. At 100 dimensions, the completion time of the entire classification task for M0–M3 is 7.5, 6.2, 6.9, and 5.8 s, respectively. Overall, FG-ADE exhibits a good balance between accuracy and time consumption, and can still maintain strong classification performance in high-dimensional complex data. This study validates the robustness of the model in class imbalance problems by using the Credit Card Fraud Dataset from the UCI database and a Synthetic imbalance dataset as experimental data. The class imbalance problem is tested using three data processing methods: raw data, Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE), and undersampling. The results are shown in Figure 10.

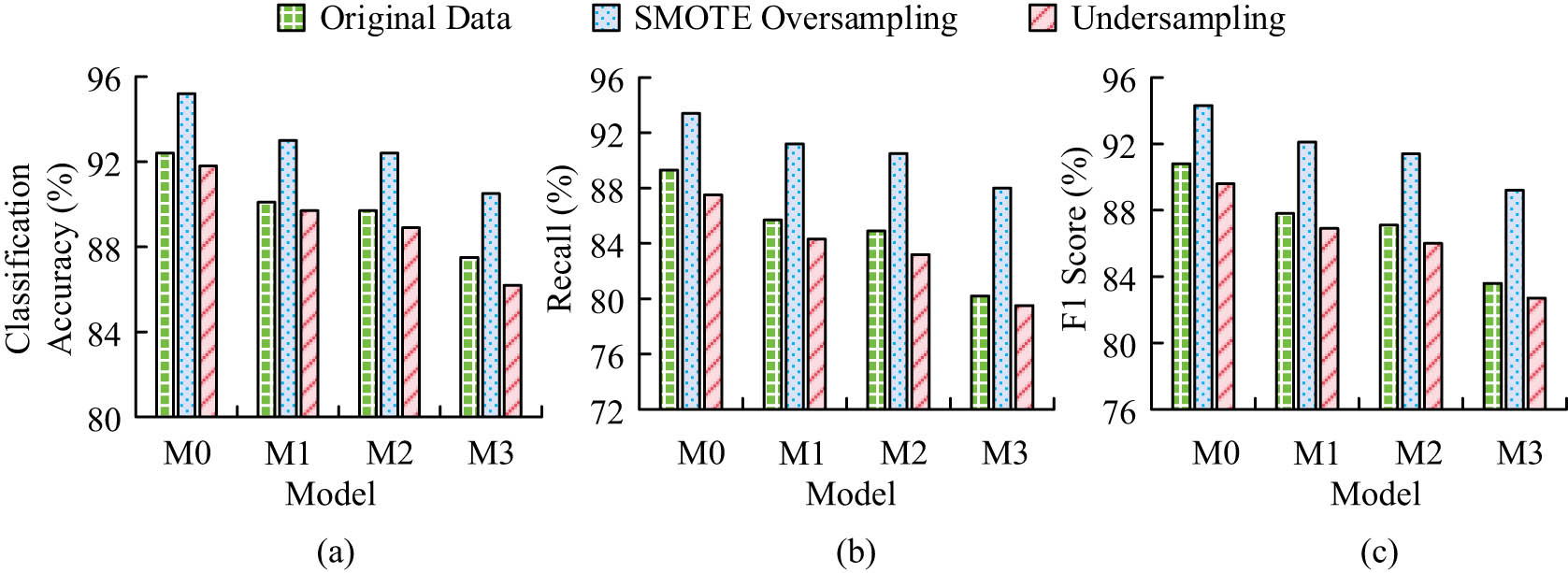

Robustness comparison in class imbalance problem: (a) Classification accuracy, (b) comparison of recall, and (c) comparison of F1.

In Figure 10(a), among the three data processing methods, M0 has the highest classification accuracy, reaching 95.2% under SMOTE, which is higher than M1’s 93.0, M2’s 92.4, and M3’s 90.5%. In Figure 10(b), M0 performs outstandingly in terms of recall rate, with 89.3, 93.4, and 87.5% under raw data, SMOTE, and undersampling, which are higher than the comparison model, indicating that M0 has a stronger recognition ability for minority categories. In Figure 10(c), the F1 score of M0 is the highest among the three data processing methods, at 90.8, 94.3, and 89.6%, further demonstrating its superior comprehensive performance in imbalanced data. Therefore, the results validate the robustness and optimization effectiveness of the FG-ADE algorithm in class imbalance problems. To further evaluate the practical feasibility of the FG-ADE model, a comparative analysis of computational efficiency and resource consumption is conducted under varying feature dimensions. All models are executed on the same hardware platform. For each model, the average runtime for completing a full classification task is recorded, along with CPU utilization and peak memory usage. The results for the 100-dimensional case are shown in Table 3.

Comparison of computational resource usage across models

| Model | Avg. runtime (s) | Avg. CPU utilization (%) | Peak memory usage (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | 6.8 | 82.4 | 496 |

| M1 | 5.9 | 79.1 | 463 |

| M2 | 6.3 | 80.7 | 478 |

| M3 | 5.4 | 77.5 | 458 |

As shown in Table 3, the FG-ADE model has an average runtime of 6.8 s on the 100-dimensional dataset. In comparison, the traditional DE algorithm requires 5.9 s, the PSO-GA model takes 6.3 s, and the Gradient Descent model finishes in 5.4 s. Regarding CPU utilization, FG-ADE reaches 82.4%, while the traditional DE, PSO-GA, and Gradient Descent models reach 79.1, 80.7, and 77.5%, respectively. In terms of peak memory usage, FG-ADE consumes 496 megabytes, compared to 463 megabytes for traditional DE, 475 megabytes for PSO-GA, and 458 megabytes for Gradient Descent. Overall, although FG-ADE incurs slightly higher computational costs, the increase remains moderate and within acceptable limits. Given its significantly better classification accuracy and robustness in high-dimensional scenarios, the additional computational investment is justified, demonstrating strong applicability and scalability in practical tasks.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This study proposed an FG-ADE algorithm to address SCS, STLO, insufficient population diversity, and low efficiency of ALDNM parameter optimization in traditional DE algorithms for high-dimensional complex problems. This algorithm dynamically adjusted the optimization direction through a feature-guided mechanism, combined with an adaptive parameter adjustment mechanism to flexibly set the scaling factor and crossover probability. It introduced multi-strategy mutation operations to balance global exploration and local development capabilities, and was ultimately applied to parameter optimization of ALDNM. In the experiment, FG-ADE performed outstandingly in high-dimensional optimization problems, achieving convergence accuracies of 0.994, 0.997, and 0.996 on Rastrigin, Rosenbrock, and Ackley functions, outperforming the comparison algorithms. In the classification task, FG-ADE achieved a classification accuracy of 95–99% on the UCI Wine Dataset and 91–97% on the MNIST Dataset. In addition, in the class imbalance problem, the F1 score of the model reached 94.3% under SMOTE conditions, demonstrating strong robustness. Research has shown that FG-ADE has achieved satisfactory classification accuracy, robustness, and generalization ability on various real-world and synthetic datasets, and maintains stable optimization performance under high-dimensional conditions. The proposed improvement strategy provides a new perspective for the application of evolutionary algorithms in neural network structure optimization, with theoretical and practical value.

Nevertheless, the manuscript still has certain limitations. The overall computational cost of the algorithm is relatively high, and its performance is sensitive to specific hyperparameter configurations and data distributions. In addition, although SMOTE oversampling effectively improves the recognition of minority classes in imbalanced classification tasks, it may introduce redundant samples and increase the risk of model overfitting in high-dimensional or small sample scenarios. Future research may focus on the following directions: first, a fine-grained performance analysis mechanism can be introduced to clarify the contribution of each module to the overall computational efficiency; Second, lighter feature guidance and mutation strategies can be developed to improve execution efficiency in large-scale data scenarios; Third, boundary enhancement or noise filtering mechanisms can be combined to improve the generalization of oversampling strategies; Fourth, the FG-ADE framework can be extended to other architectures such as convolutional neural networks and graph neural networks to further validate its generalization and adaptability, and expand its applicability in complex fields such as image recognition and sequence modeling.

-

Funding information: The author states no funding is involved.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] S. Li, D. W. McLaughlin, and D. Zhou, “Mathematical modeling and analysis of spatial neuron dynamics: Dendritic integration and beyond,” Commun. Pure Appl. Math., vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 114–162, 2023.10.1002/cpa.22020Suche in Google Scholar

[2] X. Luo, X. Wen, Y. Li, and Q. Li, “Pruning method for dendritic neuron model based on dendrite layer significance constraints,” CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 308–318, 2023.10.1049/cit2.12234Suche in Google Scholar

[3] A. Yilmaz and U. Yolcu, “A robust training of dendritic neuron model neural network for time series prediction,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 35, no. 14, pp. 10387–10406, 2023.10.1007/s00521-023-08240-6Suche in Google Scholar

[4] S. Ji and J. Karlovšek, “Optimized differential evolution algorithm for solving DEM material calibration problem,” Eng. Comput., vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 2001–2016, 2023.10.1007/s00366-021-01564-8Suche in Google Scholar

[5] M. K. Kar, S. Kumar, A. K. Singh, and S. Panigrahi, “Reactive power management by using a modified differential evolution algorithm,” Opt. Control. Appl. Methods, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 967–986, 2023.10.1002/oca.2815Suche in Google Scholar

[6] C. Hebbi and H. Mamatha, “Comprehensive dataset building and recognition of isolated handwritten Kannada characters using machine learning models,” Artif. Intell. Appl., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 179–190, 2023.10.47852/bonviewAIA3202624Suche in Google Scholar

[7] J. Ji, J. Zhao, Q. Lin, and K. C. Tan, “Competitive decomposition-based multiobjective architecture search for the dendritic neural model,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 53, no. 11, pp. 6829–6842, 2022.10.1109/TCYB.2022.3165374Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] M. I. Georgescu, R. T. Ionescu, N. C. Ristea, and N. Sebe, “Nonlinear neurons with human-like apical dendrite activations,” Appl. Intell., vol. 53, no. 21, pp. 25984–26007, 2023.10.1007/s10489-023-04921-wSuche in Google Scholar

[9] N. Zhang and Y. Yan, “Approximate logical dendritic neuron model based on selection operator improved differential evolution algorithm,” Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci., vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 113–122, 2023.10.25236/AJCIS.2023.060516Suche in Google Scholar

[10] E. Kölemen, “Forecasting of Turkey’s Hazelnut export amounts according to seasons with dendritic neuron model artificial neural network,” Turk. J. Forecast., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1–7, 2024.10.34110/forecasting.1468420Suche in Google Scholar

[11] H. Zhang, T. Liu, X. Ye, A. A. Heidari, G. Liang, H. Chen, et al., “Differential evolution-assisted salp swarm algorithm with chaotic structure for real-world problems,” Eng. Comp., vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 1735–1769, 2023.10.1007/s00366-021-01545-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] S. Chakraborty, A. K. Saha, A. E. Ezugwu, J. O. Agushaka, R. A. Zitar, and L. Abualigah, “Differential evolution and its applications in image processing problems: A comprehensive review,” Arch. Comput. Methods Eng., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 985–1040, 2023.10.1007/s11831-022-09825-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] A. M. Ibrahim and M. A. Tawhid, “An improved artificial algae algorithm integrated with differential evolution for job-shop scheduling problem,” J. Intell. Manuf., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 1763–1778, 2023.10.1007/s10845-021-01888-8Suche in Google Scholar

[14] A. Thakare, A. M. Anter, and A. Abraham, “Seizure disorders recognition model from EEG signals using new probabilistic particle swarm optimizer and sequential differential evolution,” Multidimens. Syst. Signal. Process., vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 397–421, 2023.10.1007/s11045-023-00870-2Suche in Google Scholar

[15] P. Tiwari, V. N. Mishra, and R. P. Parouha, “Developments and design of differential evolution algorithm for non-linear/non-convex engineering optimization,” Arch. Comput. Methods Eng., vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 2227–2263, 2024.10.1007/s11831-023-10036-9Suche in Google Scholar

[16] F. Zhao, H. Zhang, L. Wang, T. Xu, N. Zhu, and J. Jonrinaldi, “A multi-objective discrete differential evolution algorithm for energy-efficient distributed blocking flow shop scheduling problem,” Int. J. Prod. Res., vol. 62, no. 12, pp. 4226–4244, 2024.10.1080/00207543.2023.2254858Suche in Google Scholar

[17] X. Lu and S. Xu, “Performance optimization of vertical axis wind turbine based on Taguchi method, improved differential evolution algorithm and Kriging model,” Energy Sources Part. A: Recov. Util. Environ. Eff., vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 2792–2810, 2024.10.1080/15567036.2024.2308655Suche in Google Scholar

[18] A. Dey, S. Bhattacharyya, S. Dey, J. Platos, and V. Snasel, “A quantum inspired differential evolution algorithm for automatic clustering of real life datasets,” Multimed. Tools Appl., vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 8469–8498, 2024.10.1007/s11042-023-15704-3Suche in Google Scholar

[19] T. Li, Y. Meng, and L. Tang, “Scheduling of continuous annealing with a multi-objective differential evolution algorithm based on deep reinforcement learning,” IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng., vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 1767–1780, 2023.10.1109/TASE.2023.3244331Suche in Google Scholar

[20] J. Niu, Z. Liu, Q. Pan, Y. Yang, and Y. Li, “Conditional self-attention generative adversarial network with differential evolution algorithm for imbalanced data classification,” Chin. J. Aeronaut., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 303–315, 2023.10.1016/j.cja.2022.09.014Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Air fare sentiment via Backtranslation-CNN-BiLSTM and BERTopic

- Visual analysis of urban design and planning based on virtual reality technology

- Creative design of digital media art based on computer visual aids

- Deep learning-based novel aluminum furniture design style recognition and key technology research

- Research on pattern recognition of tourism consumer behavior based on fuzzy clustering analysis

- Driving business growth through digital transformation: Harnessing human–robot interaction in evolving supply chain management

- Applications of virtual reality technology on a 3D model based on a fuzzy mathematical model in an urban garden art and design setting

- Approximate logic dendritic neuron model classification based on improved DE algorithm

- Special Issue: Human Behavior and User Interfaces

- Study on the influence of biomechanical factors on emotional resonance of participants in red cultural experience activities

- Special Issue: State of the Art Human Action Recognition Systems

- Research on dance action recognition and health promotion technology based on embedded systems

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Air fare sentiment via Backtranslation-CNN-BiLSTM and BERTopic

- Visual analysis of urban design and planning based on virtual reality technology

- Creative design of digital media art based on computer visual aids

- Deep learning-based novel aluminum furniture design style recognition and key technology research

- Research on pattern recognition of tourism consumer behavior based on fuzzy clustering analysis

- Driving business growth through digital transformation: Harnessing human–robot interaction in evolving supply chain management

- Applications of virtual reality technology on a 3D model based on a fuzzy mathematical model in an urban garden art and design setting

- Approximate logic dendritic neuron model classification based on improved DE algorithm

- Special Issue: Human Behavior and User Interfaces

- Study on the influence of biomechanical factors on emotional resonance of participants in red cultural experience activities

- Special Issue: State of the Art Human Action Recognition Systems

- Research on dance action recognition and health promotion technology based on embedded systems