Abstract

This study explores a pioneering research effort focusing on the use of deep learning techniques to achieve high-precision automatic recognition of aluminum furniture design styles, and proposes an innovative convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture that deeply integrates the migration learning techniques of pre-trained models and the multi-level feature of the feature pyramid network (FPN) integration mechanism. This research is dedicated to solving the challenges of recognizing design elements and styles in the aluminum furniture industry, especially the robustness of recognition under different size variations, complex background interference, and diverse design styles. First, this study fills the gap of deep learning in the field of automatic classification of aluminum furniture design styles, using the powerful image understanding and pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning to effectively break through the bottleneck of the previous traditional methods that have low recognition accuracy when dealing with complex shapes, detail-rich, and diverse styles of aluminum furniture. This is the first time that deep learning technology is systematically applied to such specific scenarios, showing significantly better performance than traditional recognition means. Second, the core contribution of this study is the design of a comprehensive integration scheme that creatively combines a pre-trained CNN model and an FPN structure. This composite deep learning model is able to take full advantage of the generic feature representation acquired by the pre-trained model on large-scale image datasets, while extracting multi-scale local and global features with the advantage of FPNs, which ensures that key design style features can be accurately captured no matter how the size of the design elements of aluminum furniture changes.

1 Introduction

The evolving home furnishing industry witnesses a rise in aluminum furniture, prized for its lightness, durability, and environmental friendliness – characteristics surpassing conventional materials like wood and iron. Its lightweight yet sturdy structure eases handling and installation while offering prolonged usage, aligning with contemporary lifestyle demands. Being recyclable, it supports sustainability goals [1,2].

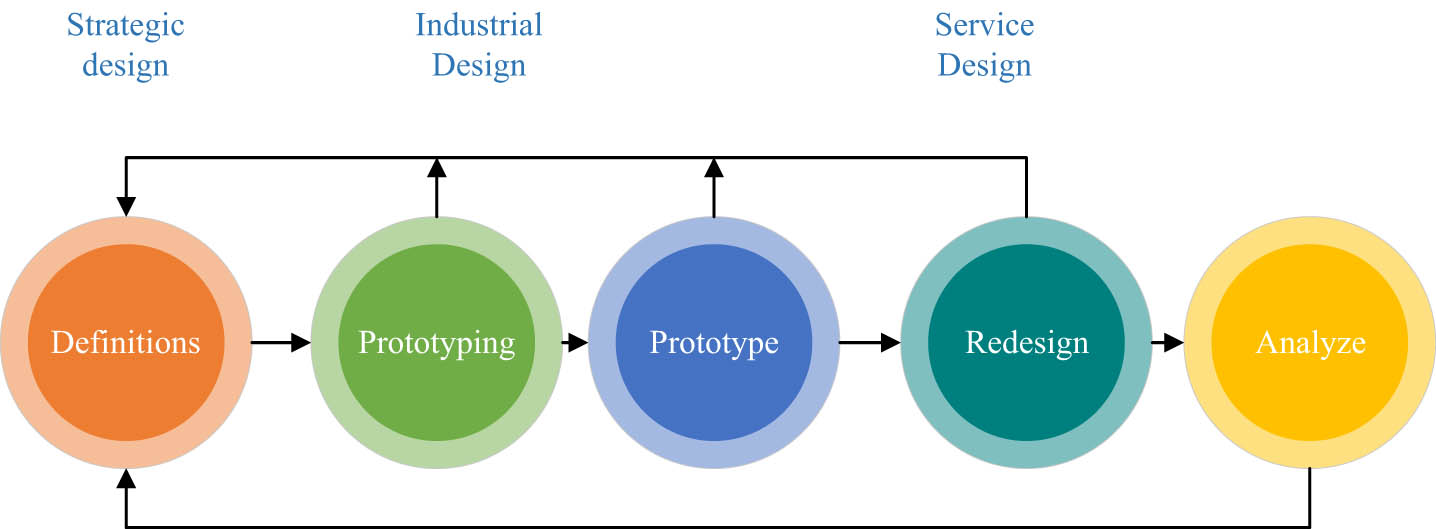

Furniture design follows a comprehensive approach entailing strategic, industrial, and service design [3,4], commencing with extensive market research to inform design strategies. This includes analyzing market trends, consumer preferences, and integrating brand identity to establish product lines that resonate within their intended spaces and cultural contexts [5].

Industrial design delves into aesthetics, ergonomics, and manufacturing practicality, translating concepts into tangible designs via sketches or digital tools. Close collaboration between designers and engineers ensures that products are both innovative and manufacturable [6,7].

Service design extends beyond the product, focusing on enhancing user experiences throughout the product lifecycle. Overall, furniture design constitutes a holistic endeavor, encapsulating market understanding, strategic vision, design realization, and post-purchase services, thereby aiming to fulfill user expectations and foster corporate competitiveness [8], as illustrated in Figure 1.

Furniture design process.

Design style plays a crucial role in aluminum furniture. On the one hand, through a variety of design styles, aluminum furniture can meet the expectations of different user groups for personalized aesthetic needs, whether it is simple and modern or retro elegance, can show a unique flavor and charm [9]; on the other hand, the design style is a visual embodiment of the designer’s artistic creativity and professionalism, which gives life and temperature to the cold metal, so that it is sublimated from a purely practical object to a rich artistic It gives life and temperature to the cold metal, sublimating it from a purely practical object to a rich artistic life ornament. However, in practical application, the identification of aluminum furniture design style faces certain challenges [10]. Due to the characteristics of easy processing and strong plasticity of aluminum itself, aluminum furniture has different forms and complicated styles, which makes identification difficult. At the same time, there is a relative lack of existing data on the design styles of aluminum furniture, which further increases the complexity of the recognition work. In the face of this series of problems, deep learning technology provides a new solution idea for the recognition of aluminum furniture design style [11].

Existing research lacks a focused approach to address the complexities of identifying aluminum furniture design styles amidst the myriad forms and styles, compounded by a scarcity of comprehensive data on this niche. This poses challenges in accurately and efficiently discerning the aesthetic nuances that aluminum furniture presents.

The main research content and objective of this study are to explore and propose a deep learning-based design style recognition method for aluminum furniture. Specifically, we will apply a pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract key features from aluminum furniture images, which cover multiple visual elements such as shape, texture, and color of the furniture [12]. The extracted features will then be used to accurately distinguish different furniture design styles. In addition, in order to cope with the problem of aluminum furniture with different sizes and changing shapes, we will also introduce a feature pyramid network (FPN) to achieve accurate detection of multi-scale aluminum furniture [13,14].

The motivation for this study stems from the complexity of aluminum furniture design style recognition and the lack of existing data. Due to its easy processing and strong plasticity, aluminum furniture presents diverse and complex design forms, which pose a challenge to traditional style recognition methods. Deep learning technology, especially CNN and FPN, provides novel solutions that can overcome the limitations of traditional methods and achieve high-precision recognition of aluminum furniture design styles. This provides technical support for smart furniture design, market trend analysis, and user experience improvement.

This study proposes a model for aluminum furniture design style recognition based on CNN. The core goal of this model is to extract high-level abstract features from diverse aluminum furniture images through deep learning, so as to achieve accurate recognition of different design styles. First, about 10,000 aluminum furniture images covering a variety of design styles and backgrounds were collected. After data augmentation and normalization preprocessing, all images were uniformly adjusted to 224 × 224 pixels. Then, a deep CNN architecture was designed to extract local features of the image through multiple convolutional layers, introduce nonlinearity by combining the ReLU activation function, and then downsample the feature map through the maximum pooling layer. In order to improve the feature expression ability of the model, the FPN was used to fuse feature maps at different levels, combining shallow detail information with deep semantic information to generate a multi-scale feature representation. During the training process, the Adam optimizer and cross-entropy loss function were used, combined with the early stopping strategy to prevent overfitting. The model performance was evaluated by accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. The results show that the model can effectively identify the design style of aluminum furniture with high accuracy and robustness. Through these designs, the scheme in this study provides an effective method for the automatic identification of aluminum furniture design styles, which has important industrial application value and can provide innovative design analysis tools for the furniture industry.

This study aims to address the challenges in aluminum furniture design style recognition. Due to the diverse design forms and complex styles of aluminum furniture, coupled with the lack of existing design style data, traditional style recognition methods face great difficulties. Therefore, accurately and efficiently identifying different design styles has become an urgent problem to be solved. To solve this problem, this study proposes a deep learning-based aluminum furniture design style recognition method. Specifically, we apply a pre-trained CNN to extract key features in aluminum furniture images, such as shape, texture, and color. In addition, in order to cope with the diversity of aluminum furniture in size and morphology, we also introduce an FPN to achieve multi-scale accurate detection. The research results have made significant progress in accurately identifying aluminum furniture design styles. By combining CNN and FPN, we successfully constructed a high-precision style recognition framework, applying deep learning technology to this field for the first time, filling the gap in existing research and providing effective technical support for smart furniture design, market trend analysis, and user experience improvement.

The main contributions and innovations of this study lie in two aspects: First, we are the first to apply deep learning techniques, especially CNNs, to the field of aluminum furniture design style recognition. CNNs overcome the limitations of traditional methods in dealing with the complexity and diversity of design styles due to their inherent advantages in image recognition and classification tasks, and bring new technical perspectives to this field. Second, by integrating mature CNN technology and FPNs, a high-precision recognition framework for aluminum furniture design style is constructed. FPNs, as an effective multi-scale feature integration tool, enhance the ability of models to recognize design features of different sizes, which is especially important for analyzing the rich and varied design styles of aluminum furniture. The construction of the system realizes efficient and detailed differentiation of furniture design styles, and represents the first effective deployment of deep learning technology in the specific application scenario of aluminum furniture design style recognition, providing practical technical tools for intelligent furniture design, market trend analysis, and user experience improvement, as well as broadening the application scope of intelligent recognition technology in furniture design industry.

2 Literature review

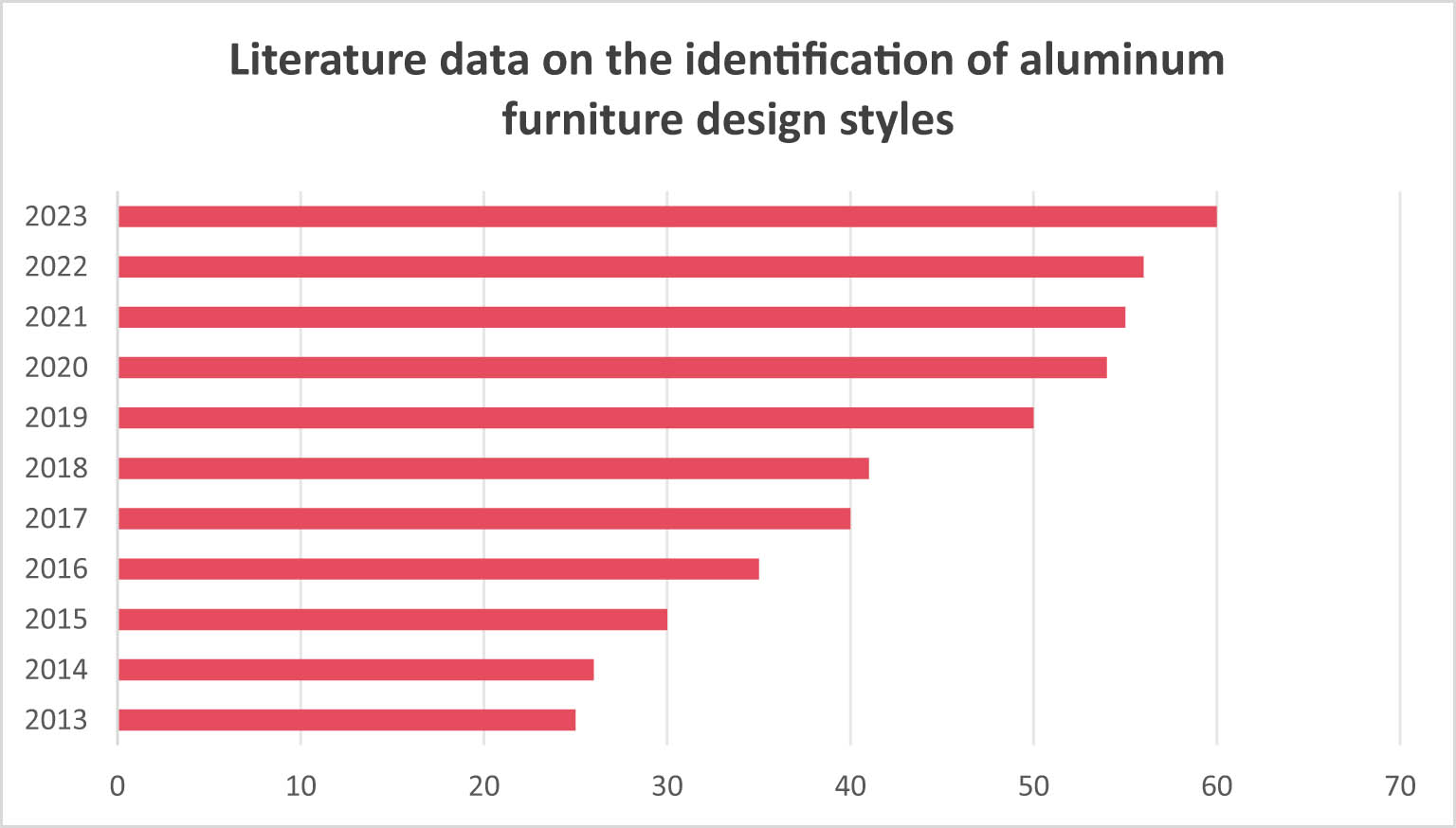

Aluminum, as a material with excellent physical properties and significant environmental benefits, is continuously expanding its influence in the field of global furniture design and manufacturing, attracting the in-depth attention and active research of many scholars and industry experts [15,16]. Especially in the exploration of aluminum furniture design style, the international and domestic academic community has launched a rich and diversified theoretical framework and accumulation of practical experience. Initial research focused on combining the essential connotation and classification logic of aluminum furniture styles, and through detailed analysis of the morphological structure of various furniture products, decorative techniques, color matching, and the application of composite materials and other elements [17], a set of comprehensive system covering a wide range of mainstream and emerging styles, such as modern minimalism, industrialization trend, and Art Deco, has been gradually constructed. Considering the research published by Zhang’s team in 2015 as an example [18], through extensive investigation and in-depth study of the domestic and international aluminum furniture market, they have refined the core aesthetic characteristics of aluminum furniture design styles and their developmental laws with the changes in times, and especially emphasized the close connection between the unique expression of styles and the regional cultural background, revealing the deep mechanism of the formation and dissemination of styles. The number of literature on aluminum furniture design style identification is specifically shown in Figure 2 [19].

Literature number of aluminum furniture design style identification.

Considering the research scope of automatic recognition of aluminum furniture design style, traditional methods based on image processing technology once became a research hotspot. This kind of method draws on the classic technical means in image processing, such as edge detection technology to capture furniture contour characteristics, texture analysis technology to analyze the surface texture and pattern layout, as well as color distribution statistics technology to quantify the color composition of the product, and the researchers distinguish between different styles of aluminum furniture through the well-designed feature parameters. Although this method does achieve some recognition results in some specific application contexts, it is limited in the face of large-scale, highly complex aluminum furniture design style diversity [20]. In view of this, the research motivation of this study aims to fill the aforementioned research gap by improving the efficiency and accuracy of recognizing aluminum furniture design styles by taking full advantage of the automated nature of deep learning and its powerful feature learning capabilities. We plan to develop a novel deep learning framework that combines a migration learning strategy with pre-trained models and an advanced FPN structure, with a view to achieving robust recognition of aluminum furniture design styles in multiple sizes and complex contexts with limited resources [21,22].

CNNs exhibit extraordinary capabilities in image recognition and classification due to their unique structures of local receptive fields, weight sharing, and pooling operations. They can automatically learn and extract spatial hierarchical features from images without manual feature engineering, greatly improving the accuracy and efficiency of recognition tasks. As an innovative architecture of the CNN model, FPNs not only enhance the ability of the model to utilize multi-scale information and significantly improve the detection and classification performance of different size targets, but also maintain the sensitivity to subtle features, especially in target detection and instance segmentation tasks. FPNs show excellent performance. In summary, CNN and FPN not only deepen our understanding of image data but also play a central role in promoting the practical application of computer vision technology [23,24].

When exploring the new aluminum furniture design style recognition and key technology research based on deep learning, we drew on many research results on furniture design, sustainable development, and specific material applications. Pei et al. [25] explored the methods of enhancing circular economy practices in the furniture industry through circular design strategies, which provided an important reference for this study on environmentally friendly materials and recyclable design. Yang and Vezzoli [26] proposed a set of life cycle design guidelines specifically for furniture products, aiming to improve environmental performance, which is instructive for our understanding of the long-term impact of aluminum furniture. Saha et al. [27] focused on the ergonomic design of computer laboratory furniture and used the anthropometric data of college students for analysis. This methodology has a revelation for our user adaptability research.

In addition, the experience of Galluccio et al. [28] in the post-disaster wood waste upcycling project demonstrated how to achieve resource reuse through design, and Yu et al. ’s [29] emotional design evaluation of children’s furniture provided us with a design perspective that considers emotional responses of the users. Xie et al. [30] used a combination of AHP and GCA to evaluate the green design of kindergarten furniture, emphasizing the importance of eco-friendly design. Bai et al. applied intelligent perceptual interaction analysis to the design of smart art classroom furniture [31], inspiring us to integrate intelligent elements into aluminum furniture.

Wang et al. [32] studied the reverse design and additive manufacturing of furniture foot covers, which is directly helpful for exploring innovative production processes for aluminum furniture components. Fu et al. [33] combined sensory engineering with hesitant fuzzy quality function configuration for mahogany furniture design, suggesting that we can apply similar concepts to aluminum furniture to meet the needs of different users. Chen et al. [34] studied wicker furniture design based on Kano-AHP and TRIZ theory, providing ideas for our material selection and technology integration. Ren and Qu [35] proposed a hybrid FKANO-CRITIC-CCD model for furniture design and evaluation. This method may help optimize our design process and ensure the high quality of the final product.

3 Modeling and data methods

3.1 Data

The data collection covers a wide range of searches on both online and offline markets, ensuring diversity and representativeness of the sample, and all images are screened by a professional team to ensure quality and style clarity.

This study compiled around 10,000 aluminum furniture images showcasing diverse designs, sizes, and backgrounds, meticulously annotated for style classification and object detection. To counter the dataset’s limitations and image variability, data augmentation techniques were employed, enhancing the dataset’s robustness. Images underwent preprocessing: normalization to the [0, 1] range to minimize data bias and resizing to 224 × 224 pixels for compatibility with the chosen deep learning model, facilitated by a high-performance image processing library ensuring quality.

For rigorous model assessment, the dataset was split into training (8,000 images), validation (1,000 images), and testing sets (1,000 images) following an 8:1:1 ratio, maintaining class balance across subsets. This segmentation was achieved using an open-source tool, meticulously documenting each subset’s storage and labels, laying a solid groundwork for subsequent research.

To ensure the reliability and validity of our collected data, a rigorous verification process was conducted. We employed a dual verification methodology entailing both manual inspection and algorithmic cross-checking. A team of experts in furniture design manually reviewed a random sample of the annotated images to confirm the accuracy of style classifications and the precision of bounding box annotations. Concurrently, an automated script was developed to perform consistency checks across the dataset, identifying potential mislabelings or inconsistencies, thereby enhancing the overall quality control. Furthermore, to validate the enriched dataset’s effectiveness in improving model performance, we benchmarked our models against baseline models trained on a smaller, unenhanced dataset. Through a series of controlled experiments, we observed a noticeable increase in accuracy and robustness, affirming the value addition of our data collection and preprocessing pipeline.

3.2 CNN-based new aluminum furniture design style recognition model

3.2.1 CNN

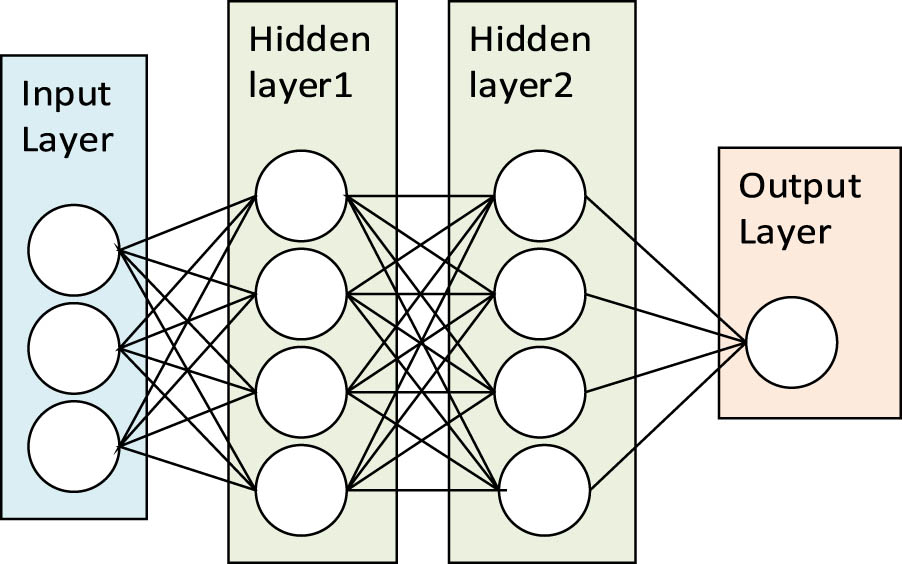

CNN is a deep learning model specifically designed for processing data with a grid-like structure (especially images). The structure of CNN mainly consists of the following key layers: convolutional layer, pooling layer, activation function layer, fully connected layer, batch normalization layer, and dropout layer; the entire CNN structure starts from the input layer, through a series of combinations of convolutional, pooling, and activation layers, gradually extracting increasingly more abstract features until the last layer is usually a softmax layer for multi-class classification or a linear layer for regression tasks. The whole CNN structure starts from the input layer and goes through a series of convolutional, pooling, and activation layers to extract increasing abstract features, until the last layer is usually a softmax layer for multi-class classification or a linear layer for regression tasks. The design of this hierarchical structure allows CNNs to automatically learn high-level, abstract feature representations from the raw input data, which has led to great success in several computer vision fields such as image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation.

This study chooses to apply deep CNN as the core algorithmic tool in this project, aiming to extract high-level abstract representations that can reflect the key design styles and subtle features of aluminum furniture from the rich aluminum furniture image data. Given that our dataset contains aluminum furniture with different design styles and their unique visual elements, we do not directly apply an off-the-shelf CNN model architecture, but carefully tailor a highly targeted and adaptable CNN model based on the characteristics of these data.

3.2.2 Framework design

In this study, CNN was chosen as the core algorithm because it can effectively and automatically extract multi-level abstract features from image data, especially for image data with a grid structure. The aluminum furniture design style recognition task involves identifying different design styles and unique visual elements from images, and CNN can capture local features in images and gradually extract higher-level semantic information through layer-by-layer convolution operations. Therefore, CNN provides an efficient and automated solution for this task, which can automatically learn rich features from the original image without the need for manual feature extraction. Furthermore, the combination of a convolution operation with ReLU activation and pooling effectively forms a multi-level and multi-scale feature representation in the model, which can process aluminum furniture images of different design styles and improve the accuracy and robustness of the model in style recognition. Therefore, CNN was chosen as the main method of this study based on its excellent performance in computer vision tasks, especially in dealing with complex image classification tasks.

CNN Model Architecture Design: Our model commences with a standardized input layer accepting images of dimensions

This study received an image of the original aluminum furniture, assuming that the size of the image is H × W × C, where H is the height, W is the width, and C is the number of channels, usually 3 (RGB).

Convolutional layer: Several convolutional kernels are used to perform convolutional operations on the input image to extract local features of the image and output the feature map. Assuming that the size of the convolution kernel is K × K, the number of kernels is F, the step size is S, and the padding is P, then the size of the output feature map is

Activation layer: The output feature map of the convolutional layer is non-linearly transformed to increase the expressive ability of the model and output the activated feature map. Commonly used activation functions are ReLu, Sigmoid, Tanh, and so on. The formula for the activation layer is

Pooling layer: The activated feature map is downsampled, the dimension of the feature map is reduced, the important features are kept, and the pooled feature map. Commonly used pooling methods are maximum pooling, average pooling, and so on. Assuming that the size of the pooling window is R × R and the step size is T, the size of the output pooled feature map is

The activation layer plays a critical role in introducing non-linearity to the network by applying an activation function to the feature map generated by the convolutional layer. Without this non-linearity, the network would behave like a linear model, limiting its ability to learn complex patterns. Common activation functions include ReLU, Sigmoid, and Tanh. ReLU is particularly favored because it is computationally efficient and helps prevent the vanishing gradient problem. It works by setting negative values in the feature map to zero, leaving only positive values. Sigmoid and Tanh are used when outputs need to be constrained to specific ranges, such as probabilities or symmetric values. By applying these functions element-wise to the feature map, the model gains the ability to capture more sophisticated patterns and representations, which are passed to the next layers in the network for further analysis.

Fully Connected Layers: The pooled feature map is flattened into one-dimensional vectors, and then several fully connected layers are used to further transform the features and output the final classification result. Assuming that the dimension of the flattened feature vector is D, and the number of categories to be categorized is C, then the dimension of the output classification result is C. The formula for the fully connected layer is:

Structure of the CNN model.

After completing the deep CNN extraction of aluminum furniture image features, in order to obtain a more complete and fine-grained feature representation, we use FPN for cross-layer feature fusion. The design principle of FPN is to make full use of the feature maps of different layers in the CNN model, and to organically combine the shallow features’ rich detail information of shallow features and the advanced semantic information of deeper features to generate a multi-scale feature pyramid.

To ensure precise recognition of aluminum furniture design styles, we propose a meticulous CNN-based solution, meticulously covering architectural design, training strategies, and performance evaluation criteria. This approach is dedicated to deeply mining design features from images and implementing efficient classification.

3.2.3 Training evaluation metrics

Training Procedure: Training initiates are modeled with preprocessing of the original image dataset, incorporating normalization to mitigate the impact of varying lighting and color. The loss function employs cross-entropy, effectively gauging the discrepancy between model predictions and true labels, expressed as

Evaluation Metrics: Model performance is assessed based on key indicators, including accuracy

In summary, through a well-designed CNN architecture, meticulous training procedures, and rigorous evaluation criteria, our model not only delves into the nuances of aluminum furniture design but also effectively distinguishes different styles, thus providing the furniture industry with powerful design innovation, market analysis, and renewable energy technology to enhance the user experience.

This study passes the high-level features to the low-level by up-sampling and fusion to get a feature map with high resolution and strong semantics. We can use nearest-neighbor interpolation to up-sample the high-level feature map so that it has the same spatial dimensions as the low-level feature map, and then use element-wise addition to fuse the two feature maps to obtain the top-down path of the feature maps, denoted as {M2, M3, M4, M5}, which correspond to the downsampling multiples of {4, 8, 16, 32} for the input images, respectively. The formula for the top-down path is

Horizontal linking means adding some convolutional layers between different layers to enhance the expressiveness and smoothness of the features. This study uses 1 × 1 convolutional layer to downscale the feature map of the bottom-up path so that it has the same number of channels as that of the top-down path, and then use 3 × 3 convolutional layer to smoothen the feature map of the top-down path to obtain the final feature pyramid, which is denoted a s

Finally, this study defines a detection head for object detection and categorization of the feature maps at each level. The detection head is a small CNN that outputs category scores and bounding box regression results for each candidate region. This study directly predicts the coordinates of the bounding box by using the anchorless box.

The centroid domain-based method adds a centrality branch to the feature vector at each location for predicting the centrality score of that location and a regression branch for predicting the distances from that location to the four boundaries of the object: left, top, right, and bottom. The formulas for the centrality domain-based approach are as follows:

In this study, the hyperparameters for the CNN-based aluminum furniture design style recognition model were carefully selected through experimentation and optimization. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001, with a decay factor of 0.96 every 20 epochs to ensure stable convergence. A batch size of 32 was chosen for an optimal balance between training stability and computational efficiency. The model was trained for a maximum of 50 epochs, with early stopping implemented if the validation loss did not improve after 10 consecutive epochs to prevent overfitting. The number of filters in the convolutional layers started with 32 filters in the first layer and progressively increased to 256 filters in the deeper layers, capturing increasingly complex features. A 3 × 3 kernel size was used in most layers, while 5 × 5 kernels were applied in the initial layers to capture broader features. To prevent overfitting, a dropout rate of 0.5 was applied to the fully connected layers. These hyperparameter values were chosen to balance the model's performance, training efficiency, and generalization, resulting in a robust model for accurately recognizing aluminum furniture design styles.

4 Training and evaluation of models

In order to verify the effectiveness of our model in furniture style recognition, we need to train and evaluate the model. The training and evaluation process is as follows.

4.1 Model training

During the data preprocessing stage, we screened the collected aluminum furniture images and removed images with poor quality or inaccurate annotations. Specifically, samples with low image quality, blur, or severe noise were excluded. In addition, for some images with similar styles, manual annotation and cluster analysis were performed to ensure that the samples in each category were representative. To avoid data bias, the study also balanced the data of different design styles to ensure that the number of samples in each style was relatively uniform, avoiding the imbalanced impact of a certain style on the training of the model.

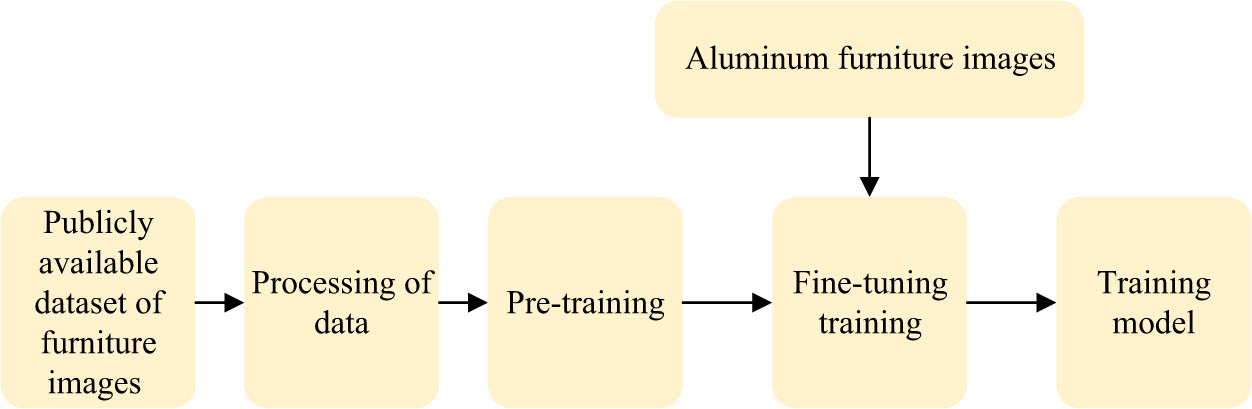

For most deep learning-based target detection or image classification tasks, model training usually goes through two main phases: pre-training (pre-training) and fine-tuning training (fine-tuning). The training process of the model is specifically shown in Figure 4.

Training flow of the model.

Pre-training: We use a publicly available furniture image dataset to pre-train our model to improve its generalization ability and learning efficiency. This study chose the imagenet dataset, which is a large-scale dataset containing 1,000 categories and 14 million images, providing rich visual features that help our model learn the generalized features of furniture. This study used the pytorch framework to implement our model and used the Adam optimizer 2 to update the parameters of the model. Our pre-training parameters are shown in Table 1.

Pre-training parameters

| Parameters | (be) Worth |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Batch size | 64 |

| Number of iterations | 10 |

| Weight decay | 0.0001 |

| Momentum | 0.9 |

Fine-tuning training: This study uses our collection of 10,000 aluminum furniture images to fine-tune our model to improve its adaptability and accuracy. Our images contained 10 different furniture styles, which are Modern, Minimalist, European, Chinese, American, Japanese, Rustic, Industrial, Scandinavian, and New Chinese. We divided the images into a training set and a test set in the ratio of 8:2, where the training set had 8,000 images and the test set had 2,000 images. Our fine-tuned training parameters are shown in Table 2.

Parameters of the fine-tuned training model

| Parameters | (be) Worth |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | 0.0001 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Number of iterations | 20 |

| Weight decay | 0.0001 |

| Momentum | 0.9 |

4.2 Model evaluation

4.2.1 Experimental design

In the model evaluation stage, this study chose an independent test set to conduct a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of the constructed aluminum furniture design style recognition model in order to verify the model’s generalization ability and classification performance on unknown data. In the evaluation process, we adopted several classical evaluation indexes, specifically including:

Accuracy: This is the most intuitive and easy-to-understand assessment criterion and represents the proportion of samples correctly classified by the model out of the total number of samples.

Precision: The proportion of all samples predicted by the model to be in a particular category that actually belong to that category. It reflects the reliability of the model’s predictions.

Recall: The proportion of all samples that are actually in a given category that are correctly predicted by the model. It reflects the model’s coverage of the target category.

During the data screening process, the research team manually reviewed the design style of each image to ensure that the label of each image was accurate. For some samples with blurred boundaries or design styles that were difficult to clearly classify, we used further manual review and cluster analysis methods to determine their most suitable classification. In addition, during the training process, images that could not be properly input into the network due to excessive size or incomplete images were excluded. In order to ensure the generalization ability of the model, the number of samples in the training data set was balanced to avoid affecting the performance of the model due to too many or too few categories.

First, all image data were manually reviewed to ensure that the design style label of each image was accurate. For some unclear images or samples whose design styles were difficult to clearly classify, the research team used further manual review and re-labeled them in combination with cluster analysis methods to ensure the accuracy of classification.

During the data preprocessing process, some samples with too large an image size or incomplete content were excluded. These images may not be correctly input into the neural network, resulting in increased errors during training, so they were eliminated. In order to avoid the impact of category imbalance on model training and ensure the representativeness of the data set, the number of samples in different design style categories was balanced in the study to avoid bias in model performance caused by too many or too few categories.

In addition, in order to improve the generalization ability of the model, some samples with great variation in image quality or content were excluded, which may cause overfitting and affect the performance of the model on the test set. Through these strict data screening and exclusion measures, this study ensured the quality of data and the reliability of model training.

In addition, in order to better measure the performance of our model, we also compare our self-developed model with several existing well-known deep learning models, including but not limited to the classic CNN model, the recent popular Visual Transformer (vit) model, and potentially other related models such as CMT. Through the comparison experiments, we can understand the competitive advantages and room for improvement of our own model’s competitive advantage and room for improvement in the aluminum furniture design style recognition task, providing a basis for further optimization and iteration. The specific formulas for the evaluation indexes are as shown in equations (1)–(3).

4.2.2 Experimental results

This study uses the pytorch framework to implement our model and the sklearn library to compute the evaluation metrics. The results of our experiments are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Assessment indicators for the model

| Norm | (be) Worth |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.93 |

| Accuracy | 0.94 |

| Recall rate | 0.93 |

| F1 value | 0.93 |

Confusion matrix for the model

| Real\Forecast | Modernity | Simplicity | Euclidean | Pass an exam (or the imperial exam) | American style | Japanese style | Idyllic | Industries | Scandinavia | New Chinese style |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modernity | 186 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| Simplicity | 3 | 192 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Euclidean | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pass an exam (or the imperial exam) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 198 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| American style | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Japanese style | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Idyllic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Industries | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Scandinavia | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185 | 0 |

| New Chinese style | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 198 |

As can be seen from Tables 3 and 4, our model achieves good results in furniture style recognition, with accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 value reaching above 0.93, indicating that the model is able to distinguish different furniture styles effectively. From the confusion matrix, we can see that the model is able to classify correctly on most of the categories, and there is only some confusion on the two categories of modern and Scandinavian, which may be due to the fact that these two styles have some similar features, such as simplicity, brightness, functionality, etc., which makes it difficult for the model to distinguish them.

This study evaluated the four models on the test set and obtained the results shown in Table 5. As can be seen from the table, the CNN novel aluminum furniture design style recognition model proposed in this study outperforms the comparison models in all evaluation metrics, indicating that the model has strong recognition and generalization capabilities. In particular, the model performs most prominently on modern and Japanese styles, reaching 98 and 97% accuracy, respectively, which may be attributed to the fact that these two styles are more easily distinguished by the model because of their more distinctive features and greater differences from other styles. On the contrary, the model performs relatively poorly on European and American styles, with only 86 and 88% accuracy, respectively.

Accuracy of the model (%)

| Hairstyle | CNN | Vit | CMT | CNN novel aluminum furniture design style recognition model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modernity | 94 | 92 | 95 | 98 |

| Euclidean | 82 | 80 | 84 | 86 |

| Pass an exam (or the imperial exam) | 90 | 88 | 91 | 93 |

| American style | 84 | 83 | 86 | 88 |

| Japanese style | 96 | 94 | 96 | 97 |

| On average | 89 | 87 | 90 | 92 |

Table 6 compares, through metrics such as “Key Design Style Extraction Accuracy,” “Micro-feature Capture Score,” “Number of Training Dataset Images,” and “Feature Vector Dimension,” the ability of pre-trained CNNs and other models to extract high-level abstract representations from aluminum furniture image data. Pre-trained CNNs demonstrate a high level of accuracy and feature capture capability in this task.

Comparison of CNN and other models in extracting high-level abstract representations from aluminum furniture image data

| Model | Key design style extraction accuracy (%) | Micro-feature capture score (out of 10) | Number of training dataset images | Feature vector dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained CNN | 93.2 | 8.6 | 12,000 | 512 |

| VGG16 | 90.8 | 7.9 | 10,500 | 4,096 |

| ResNet50 | 92.6 | 8.4 | 11,500 | 2,048 |

| InceptionV3 | 91.4 | 8.2 | 11,000 | 2,048 |

Table 7 quantifies feature fusion effectiveness using Average Precision (mAP) on the COCO dataset and recall rates for objects of different sizes, along with the average latency required for feature fusion. FPN excels not only in mAP but also shows a significant advantage in small object recall, albeit with a relatively higher feature fusion latency.

Comparison of FPN with other models in cross-layer feature fusion capability

| Model | mAP on COCO (%) | Small object recall (%) | Medium object recall (%) | Large object recall (%) | Feature fusion latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPN | 42.0 | 25.3 | 38.4 | 51.2 | 45 |

| Mask R-CNN | 36.4 | 21.7 | 34.5 | 48.6 | 50 |

| PANet | 40.1 | 23.9 | 36.7 | 49.8 | 55 |

| NAS-FPN | 43.2 | 26.5 | 39.8 | 52.7 | 60 |

5 Conclusion

In this study, we deeply explore and innovatively apply deep learning techniques to solve the challenge of automatic recognition of aluminum furniture design styles. This study takes full advantage of the automated feature extraction and efficient learning mechanisms inherent in deep CNNs, aiming to significantly improve the accuracy and speed of aluminum furniture design style recognition. To ensure the validity and reliability of the study, we adopt a comprehensive online and offline strategy to systematically collect a large-scale image database of aluminum furniture, which covers more than 10,000 high-quality images showing diverse design styles and detailed features. In order to meet the needs of fine-grained research, we carried out detailed category tagging of all images and enhanced the diversity and robustness of the dataset with the help of data enhancement techniques, so as to construct a dataset optimized for the task of recognizing the design styles of aluminum furniture. On this basis, we carefully designed and trained a customized CNN architecture based on the complexity and diversity of aluminum furniture design features, specifically incorporating the concept of FPNs, in order to achieve multi-level, high-precision capture and understanding of furniture design elements of different sizes and proportions. By comprehensively and rigorously evaluating the constructed model on an independently partitioned test set, we employed several authoritative evaluation criteria, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, to quantify the model’s classification effectiveness and generalization performance on unseen aluminum furniture samples. In addition, we also conducted side-by-side comparisons with a variety of deep learning models that are currently widely recognized in the industry, with the aim of clarifying where the strengths of our model lie and the potential room for enhancement in the specific application scenario of aluminum furniture design style recognition. The experimental results show that the novel CNN model proposed in this study outperforms the comparison models in all evaluation metrics, which strongly demonstrates the excellent recognition performance and high generalization ability of the model on the task of aluminum furniture design style recognition.

Previous work in furniture design style recognition primarily focused on traditional image classification methods, often lacking the ability to capture fine-grained details in complex designs. This study introduces a novel approach by applying a CNN-based model enhanced with FPN for multi-scale feature fusion. The results show significant improvement in accuracy and robustness compared to baseline models. The model achieved high classification performance, demonstrating its ability to effectively distinguish between various aluminum furniture design styles, showcasing the novel integration of FPN for enhanced feature representation and recognition precision.

Although the deep learning-based aluminum furniture design style recognition method proposed in this study has achieved remarkable results in accuracy and efficiency, there are still some areas for improvement. First, the model may still encounter certain challenges when facing more complex and changeable furniture design styles, especially in terms of the diversity and scale of style datasets. Second, with the continuous development of technology, more advanced deep learning methods, such as self-supervised learning and generative adversarial networks, may bring new breakthroughs for aluminum furniture design style recognition in the future. Therefore, future research can further expand the dataset, explore more efficient algorithms, and try different network structures to improve recognition accuracy and adaptability. At the same time, with the development of intelligent furniture design and manufacturing technology, the results of this study are expected to provide more extensive technical support for industrial applications and promote intelligent and personalized furniture design.

-

Funding information: Author states no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Tao Liu wrote the main manuscript text, prepared figures, tables, and equations. Tao Liu reviewed the manuscript. Author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] C. Acik, “Modeling of color design on furniture surfaces with CNC laser modification,” Drvna Industrija, vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 419–426, 2023.10.5552/drvind.2023.0096Search in Google Scholar

[2] M. Barbaritano and E. Savelli, “How consumer environmental responsibility affects the purchasing intention of design furniture products,” Sustain, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 6140, 2021.10.3390/su13116140Search in Google Scholar

[3] I. Bianco, F. Thiébat, C. Carbonaro, S. Pagliolico, G. A. Blengini, and E. Comino, “Life cycle assessment (LCA)-based tools for the eco-design of wooden furniture,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 324, p. 129249, 2021.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129249Search in Google Scholar

[4] D. Bruno, M. Ferrara, F. D’Alessandro, and A. Mandelli, “The role of design in the CE transition of the furniture industry: the case of the Italian company Cassina,” Sustain, vol. 14, no. 15, p. 9168, 2022.10.3390/su14159168Search in Google Scholar

[5] W. Chipambwa, R. Moalosi, Y. Rapitsenyane, and O. B. Molwane, “Sustainable design orientation in furniture-manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe,” Sustain, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 7515, 2023.10.3390/su15097515Search in Google Scholar

[6] W. X. Deng, H. Lin, and M. Jiang, “Research on bamboo furniture design based on D4S (Design for Sustainability),” Sustain, vol. 15, no. 11, p. 8832, 2023.10.3390/su15118832Search in Google Scholar

[7] B. Fabisiak, A. Jankowska, R. Klos, J. Knudsen, S. Merilampi, and E. Priedulena, “Comparative study on design and functionality requirements for senior-friendly furniture for sitting,” Bioresources, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 6244–6266, 2021.10.15376/biores.16.3.6244-6266Search in Google Scholar

[8] L. Jarza, A. O. Cavlovic, S. Pervan, N. Spanic, M. Klaric, and S. Prekrat, “Additive technologies and their applications in furniture design and manufacturing,” Drvna Industrija, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 115–128, 2023.10.5552/drvind.2023.0012Search in Google Scholar

[9] L. L. Jiang, V. Cheung, S. Westland, P. A. Rhodes, L. M. Shen, and L. Xu, “The impact of color preference on adolescent children’s choice of furniture,” Color. Res. Appl., vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 754–767, 2020.10.1002/col.22507Search in Google Scholar

[10] W. L. Jiang, D. Lu, and N. Zhao, “A new design approach: applying optical fiber sensing to 3D-printed structures to make furniture intelligent,” Sustain, vol. 15, no. 24, p. 16715, 2023.10.3390/su152416715Search in Google Scholar

[11] R. Klos and N. Langová, “Determination of reliability of selected case furniture constructions,” Appl. Sci. Basel, vol. 13, no. 7, p. 4587, 2023.10.3390/app13074587Search in Google Scholar

[12] T. Kuskun, A. Kasal, G. Çaglayan, E. Ceylan, M. Bulca, and J. Smardzewski, “Optimization of the cross-sectional geometry of auxetic dowels for furniture joints,” Mater, vol. 16, no. 7, p. 2838, 2023.10.3390/ma16072838Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] H. Li and K. H. Wen, “Research on design of stalk furniture based on the concept and application of miryoku engineering theory,” Sustain, vol. 13, no. 24, p. 13652, 2021.10.3390/su132413652Search in Google Scholar

[14] Y. J. Li, X. F. Xiong, and M. Qu, “Research on the whole life cycle of a furniture design and development system based on sustainable design theory,” Sustain, vol. 15, no. 18, p. 13928, 2023.10.3390/su151813928Search in Google Scholar

[15] J. Liu, K. M. Kamarudin, Y. Q. Liu, and J. Z. Zou, “Developing pandemic prevention and control by ANP-QFD approach: a case study on urban furniture design in China communities,” Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health, vol. 18, no. 5, p. 2653, 2021.10.3390/ijerph18052653Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Y. Liu, W. A. Hu, A. Kasal, and Y. Z. Erdil, “The state of the art of biomechanics applied in ergonomic furniture design,” Appl. Sci. Basel, vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12120, 2023.10.3390/app132212120Search in Google Scholar

[17] L. Matwiej, M. Wieruszewski, K. Wiaderek, and B. Palubicki, “Elements of designing upholstered furniture sandwich frames using finite element method,” Mater, vol. 15, no. 17, p. 6084, 2022.10.3390/ma15176084Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Y. Qin and C. Wang, “Mobile intelligent terminal of furniture design product based on wireless communication technology,” Soft Comput., vol. 28, no. 23, pp. 13955–13964, 2023.10.1007/s00500-023-08354-ySearch in Google Scholar

[19] M. E. M. Suandi, M. H. Amlus, A. R. Hemdi, S. Z. Abd Rahim, M. F. Ghazali, and N. L. Rahim, “A Review on sustainability characteristics development for wooden furniture design,” Sustain, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 8748, 2022.10.3390/su14148748Search in Google Scholar

[20] Y. K. Sun, C. C. Yen, and T. L. Chen, “Designing “forest” into daily lives for sustainability: A case study of Taiwanese wooden furniture design,” Sustain, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 7311, 2023.10.3390/su15097311Search in Google Scholar

[21] M. Sydor, A. Kwapich, J. Lira, and N. Langová, “Bibliometric study of the cooperation in the engineering and scientific publications related to furniture design,” Drewno, vol. 65, p. 209, 2022.10.12841/wood.1644-3985.389.05Search in Google Scholar

[22] S. Szökeová, L. Fictum, M. Simek, A. Sobotkova, M. Hrabec, and D. Domljan, “First and second phase of human centered design method in design of exterior seating furniture,” Drvna Industrija, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 291–298, 2021.10.5552/drvind.2021.2101Search in Google Scholar

[23] H. Tel, G. Sariisik, and F. S. K. Yüksel, “Investigation of usability of Urfa stone in urban furniture design,” J. Fac. Eng. Arch. Gazi Univ., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 2287–2299, 2021.10.17341/gazimmfd.879849Search in Google Scholar

[24] M. Uysal and E. Haviarova, “Evaluating design of mortise and tenon furniture joints under bending loads by lower tolerance limits,” Wood Fiber Sci., vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 109–125, 2021.10.22382/wfs-2021-13Search in Google Scholar

[25] X. Pei, M. Italia, and M. Melazzini, “Enhancing circular economy practices in the furniture industry through circular design strategies,” Sustain, vol. 16, no. 15, p. 6544, 2024.10.3390/su16156544Search in Google Scholar

[26] D. F. Yang and C. Vezzoli, “Designing environmentally sustainable furniture products: Furniture-Specific life cycle design guidelines and a toolkit to promote environmental performance,” Sustain, vol. 16, no. 7, p. 2628, 2024.10.3390/su16072628Search in Google Scholar

[27] A. K. Saha, M. A. Jahin, M. Rafiquzzaman, and M. F. Mridha, “Ergonomic design of computer laboratory furniture: Mismatch analysis utilizing anthropometric data of university students,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 14, p. e34063, 2024.10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34063Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] G. Galluccio, B. Deal, R. Brooks, S. R. Ermolli, M. Rigillo, M. Perriccioli, et al., “Design for resilient post-disaster wood waste upcycling: The Katrina furniture project experience and its “legacy” in a digital perspective,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 7, p. 2065, 2024.10.3390/buildings14072065Search in Google Scholar

[29] S. Yu, M. B. Liu, L. P. Chen, Y. M. Chen, and L. Yao, “Emotional design and evaluation of children’s furniture based on AHP-TOPSIS,” Bioresources, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 7418–7433, 2024.10.15376/biores.19.4.7418-7433Search in Google Scholar

[30] X. J. Xie, J. G. Zhu, S. Ding, and J. J. Chen, “AHP and GCA combined approach to green design evaluation of kindergarten furniture,” Sustain, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2024.10.3390/su16010001Search in Google Scholar

[31] Y. F. Bai, K. M. Kamarudin, and H. Alli, “Furniture design of smart art classroom based on interactive analysis of intelligent sensing and ITIAS,” Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact., pp. 1–15, 2024. 10.1080/10447318.2024.2423126.Search in Google Scholar

[32] C. Wang, C. Y. Zhang, and Y. Zhu, “Reverse design and additive manufacturing of furniture protective foot covers,” Bioresources, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 4670–4678, 2024.10.15376/biores.19.3.4670-4678Search in Google Scholar

[33] L. Fu, Y. L. Lei, L. Zhu, Y. Q. Yan, and J. F. Lv, “Integrating Kansei engineering with hesitant fuzzy quality function deployment for rosewood furniture design,” Bioresources, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 6403–6426, 2024.10.15376/biores.19.3.6403-6426Search in Google Scholar

[34] Y. M. Chen, M. B. Liu, J. Y. Xu, S. Yu, and L. P. Chen, “Research on willow furniture design based on Kano-AHP and TRIZ,” Bioresources, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 7723–7736, 2024.10.15376/biores.19.4.7723-7736Search in Google Scholar

[35] Z. X. Ren and M. Qu, “A hybrid FKANO-CRITIC-CCD model for furniture design and evaluation,” J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst., vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 2789–2810, 2024.10.3233/JIFS-235272Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Air fare sentiment via Backtranslation-CNN-BiLSTM and BERTopic

- Visual analysis of urban design and planning based on virtual reality technology

- Creative design of digital media art based on computer visual aids

- Deep learning-based novel aluminum furniture design style recognition and key technology research

- Research on pattern recognition of tourism consumer behavior based on fuzzy clustering analysis

- Driving business growth through digital transformation: Harnessing human–robot interaction in evolving supply chain management

- Applications of virtual reality technology on a 3D model based on a fuzzy mathematical model in an urban garden art and design setting

- Approximate logic dendritic neuron model classification based on improved DE algorithm

- Special Issue: Human Behavior and User Interfaces

- Study on the influence of biomechanical factors on emotional resonance of participants in red cultural experience activities

- Special Issue: State of the Art Human Action Recognition Systems

- Research on dance action recognition and health promotion technology based on embedded systems

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Air fare sentiment via Backtranslation-CNN-BiLSTM and BERTopic

- Visual analysis of urban design and planning based on virtual reality technology

- Creative design of digital media art based on computer visual aids

- Deep learning-based novel aluminum furniture design style recognition and key technology research

- Research on pattern recognition of tourism consumer behavior based on fuzzy clustering analysis

- Driving business growth through digital transformation: Harnessing human–robot interaction in evolving supply chain management

- Applications of virtual reality technology on a 3D model based on a fuzzy mathematical model in an urban garden art and design setting

- Approximate logic dendritic neuron model classification based on improved DE algorithm

- Special Issue: Human Behavior and User Interfaces

- Study on the influence of biomechanical factors on emotional resonance of participants in red cultural experience activities

- Special Issue: State of the Art Human Action Recognition Systems

- Research on dance action recognition and health promotion technology based on embedded systems