Abstract

Millimeter-wave (mmWave) and orbital angular momentum (OAM) multiplexing are two key technologies for modern wireless communications, where significant efforts have been devoted to combining these two technologies for extremely high channel capacities. Recently, programmable metasurfaces have been extensively studied for stimulating dynamic multi-mode OAM beams, owing to their ability of subtle dynamic modulation over electromagnetic waves in a digital manner. However, programmable metasurfaces for mmWave OAM stimulation are rarely mentioned, due to the requirement of extremely high processing precision for mmWave applications. In this paper, a programmable metasurface is presented to stimulate dynamic multi-mode mmWave vortex beams. The proposed metasurface is composed of electronically reconfigurable units, which is obtained through configuration integration of a PIN diode within each radiation patch for modulating the unit resonant property. Both low reflection losses and stabilized inverse phase states are obtained for the binary unit coding states within the operation band. Through modulating the real-time coding distribution on the metasurface by programmable bias circuit, the generation of mmWave OAM beams with mode numbers l = 0, l = +1, l = +2, and l = +3 are numerically designed and experimentally verified. Our study paves a new perspective for the cross amalgamation of both mmWave and multi-mode OAM technologies.

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of smart terminals and internet of things, large-bandwidth, and high-speed transmissions are highly demanded in modern wireless communications [1]. In the fifth-generation communication, the wideband characteristics of millimeter wave (mmWave) band have already been thoroughly studied and put into deployments, due to the rich spectrum resources [2, 3]. The next-generation wireless systems are constructed through mmWave hybrid technology to dramatically increase the data rates and augment the overall system capacity [4]. Later, mmWave technologies associated with massive MIMO and cellular communications are also introduced to expand the transmission scale and enhance service quality [5, 6]. In all these applications, smart antenna arrays with the ability of dynamic directional beamforming or beam scanning are indispensable, bringing enormous expenses based on the conventional phased array systems [7, 8]. On the other hand, vortex beams associated with orbital angular momentum (OAM) technology have also become a key promoter for the next-generation wireless communications, owing to its multimode orthogonal characteristic and potential improvement in channel capacity and spectrum efficiency [9]. OAM is known as one kind of angular momentum, which is associated with the vortex electromagnetic (EM) wavefront and a rotational phase profile of exp(iℓθ), where ℓ is the OAM topological charge and θ is the azimuth angle [10, 11]. Vortex beams with different OAM integral topological charges are orthogonal and independent with each other, and multiplex system for information transmission can thus be constructed over the same spectral channel, which brings a tremendous increase in spectrum efficiency and channel capacity [12, 13]. Owing to this unique orthogonal property, multiplex OAM has been widely studied and implemented in microwave domain [14, 15]. Later, broadband fixed-mode OAM beams are stimulated in mmWave domain through code metasurfaces [16, 17], but the OAM application for channel multiplexing has been strongly restricted, since the OAM mode cannot be modulated dynamically. Therefore, bright prospects could be apparently expected with a combination of both mmWave and dynamic multimode OAM multiplexing for better utilizing the EM spectrum [18, 19].

Many elegant design methods have been proposed for stimulating dynamic vortex beams, including reconfigurable antenna arrays [20], circular phased arrays [21], and programmable metasurfaces [22], [23], [24]. Particularly, programmable metasurfaces [25], [26], [27], [28] are artificially engineered reconfigurable planar structures with unprecedented capacity for the neat manipulation of EM waves. Compared with conventional phased array systems using digital or analog phase shifters, programmable metasurfaces show great advantages on reducing the complexity and cost for dynamic beam forming or scanning [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Recently, programmable metasurfaces have been thoroughly studied for stimulating dynamic vortex waves. 1 bit or 2 bit programmable reflective metasurfaces were constructed by integrating either PIN diodes or voltage-controlled varactor diodes to form the reconfigurable multi-mode OAM generators in C-band or X-band [34], [35], [36]. A programmable 3 bit reflective metasurface was introduced to manipulate the vortex phase front in both space and time and thus obtain the multifunctional vortex beams in X-band [37]. Later, dynamic C-band vortex beams with mode-reconfigurable and frequency-adjustable integration capabilities were produced through programmable reflective metasurface, each unit of which is composed of an octagonal ring slot and a varactor diode [38]. To avoid the feed blockage in reflective mode, a transmissive metasurface was introduced to stimulate dynamical multi-mode vortex beams and provide good spatial coverage for oblique EM incidences in X-band [39]. However, for all these designs, the programmable metasurfaces are operating at the low-frequency microwave domain, and programmable metasurfaces for stimulating mmWave OAM beams have not been presented to the best of our knowledge, due to the requirement of extremely high processing precision in mmWave applications, since metasurface in mmWave band is usually with a smaller dimension and thus more sensitive to the manufacturing process accuracy, when comparing with conventional microwave metasurfaces [40, 41].

In this paper, a reflective programmable metasurface is proposed to stimulate dynamic multi-mode mmWave vortex beams. The programmable metasurface consists of electronically adjustable units with two phase states (0/π), which are achieved by integrating a PIN diode in each radiation patch to modulate the unit resonant property. Through modulating the real-time coding distribution on the metasurface by a programmable bias circuit, dynamic multi-mode mmWave vortex beams can be generated. Moreover, in order to verify the proposed concept, a dynamic reflective programmable metasurface operating at 28–30 GHz with 20 × 20 units is designed and fabricated, which can generate four-mode adjustable vortex beams, including OAM modes l = 0, l = +1, l = +2, and l = +3. The generation of all these four OAM beams is verified by both simulations and experiments, which demonstrates the effectiveness of our design. The proposed mmWave OAM metasurface may become an eligible candidate for the hybrid communications of both mmWave and multi-mode OAM technologies in the future.

2 Theoretical design

The overall schematic diagram of the proposed mmWave metasurface system for stimulating multiple OAM beams is shown in Figure 1. A standard horn antenna is employed as the feed source and positioned in the central axis of the reflective metasurface, which emits the EM forward-traveling wave onto the metasurface. Each active metasurface unit serves as a 1 bit phase shifter for the modulation of the incoming EM wave, and mmWave vortex phase-fronts can thus be transformed in the reflected waves. Four types of vortex beams, including OAM modes l = 0, l = +1, l = +2, or l = +3, can be real-time stimulated by varying the code distributions on the metasurface, which could be dynamically modulated by biasing the PIN diodes of the units independently via a steering-logic board.

Schematic diagram of the programmable mmWave metasurface for dynamic OAM beam generation.

3 Metasurface unit design

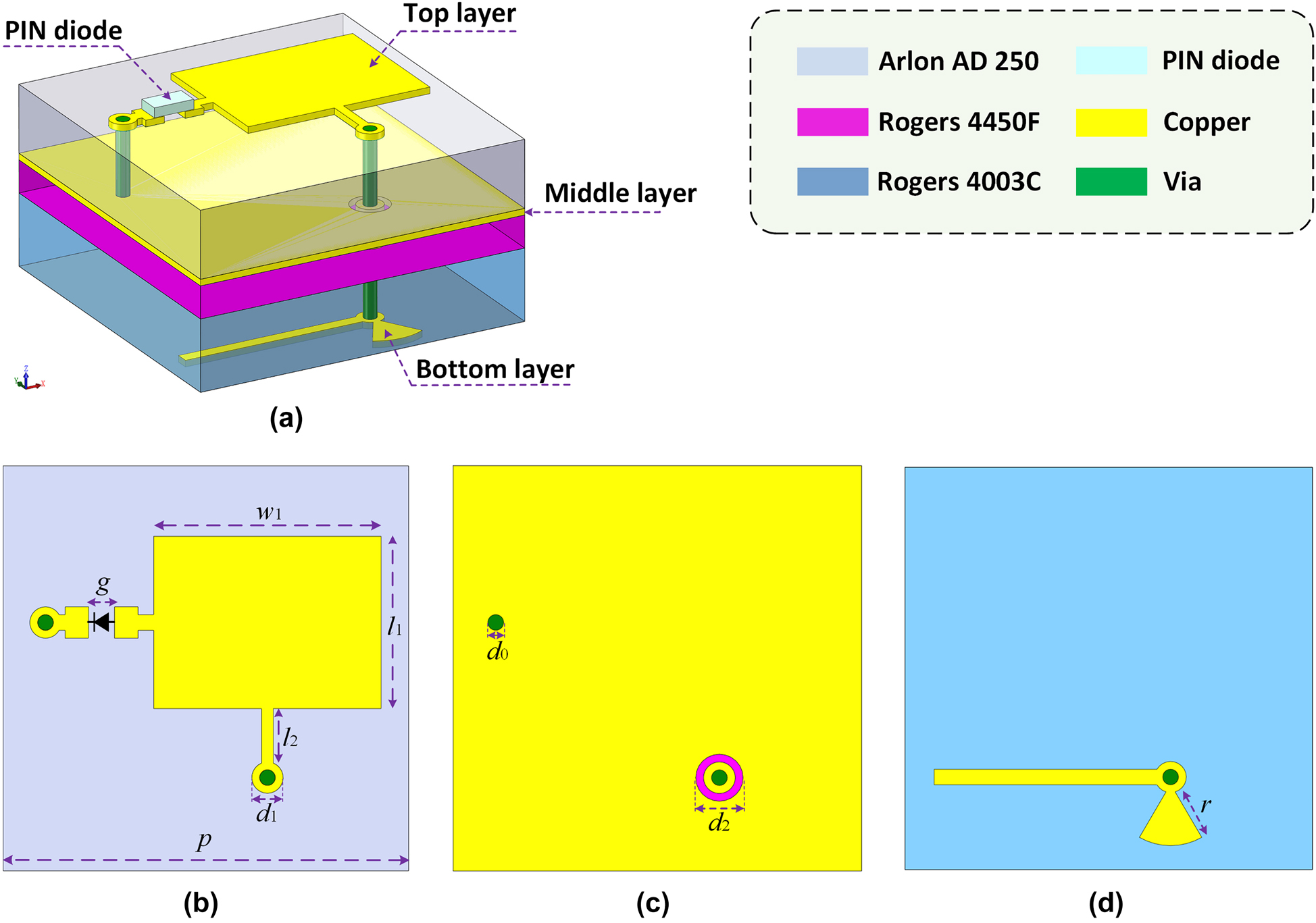

Figure 2 gives the topology of the presented programmable mmWave metasurface unit, which is further refined based on the classic architecture employing resonant tunable approach for 1 bit phase modulation, merely restricted in low-frequency microwave domain from S-band to Ku-band [27, 28, 36]. Since the mmWave metasurface is more sensitive to the manufacturing process accuracy, the concise design could be a good guarantee for the working performance even in case of an insufficient manufacturing accuracy. The unit consists of three copper layers and one PIN diode, which are supported by two substrate layers and one thin bonding film layer. The copper layers include, from top to bottom, a rectangular radiation patch, a metal ground plane, and a bias layer. The PIN diode is integrated at the end of the rectangular patch and connected with the ground plane by a shorting via in order to tune the patch’s resonance property through the bias layer, resulting in a phase difference of π in different modes for the reflected waves. In order to minimize the impact on the high frequency performance, the DC-bias line is set at the middle of the non-radiating patch edge. Besides, an open-ended radial stub is also integrated in the bias layer for isolating high frequency signals. The detailed geometrical parameters of the meta-unit are listed in the caption of Figure 2. The top substrate layer is Arlon AD250 (dielectric constant of 2.50, loss tangent of 0.0018, and thickness of 0.762 mm), the lower substrate layer is Rogers 4003C (dielectric constant of 3.55, loss tangent of 0.0027, and thickness of 0.508 mm), and the middle bonding film layer is Rogers 4450F (dielectric constant of 3.52, loss tangent of 0.004, and thickness of 0.203 mm).

Topology of the reconfigurable metasurface unit.

(a) 3D illustration. (b) Top radiating layer. (c) Middle ground layer. (d) Bottom bias layer. The unit is designed at the center frequency of 29 GHz with a periodicity of λ/2. Detailed parameters are as follows: p = 5.17, g = 0.33, w 1 = 2.9, l 1 = 2.2, l 2 = 0.7, d 0 = 0.2, d 1 = 0.4, d 2 = 0.5, and r = 0.68 (item: mm).

The PIN diode, MACOM MADP-000907-14020 [42], is adopted to acquire lower unit insertion losses within the designed mmWave frequency band, which is modeled by the equivalent lumped components in series or parallel for the two states. For positive biasing, the proposed reconfigurable unit is operating at the π-state along with a typical series resistor R π = 5.2 Ω and inductor L π = 30 pH adopted for the PIN diode; while for negative biasing, the proposed reconfigurable unit is operating at the 0-state along with a typical parallel capacitance C0 = 0.025 pF and inductor L0 = 30 pH employed for the PIN diode.

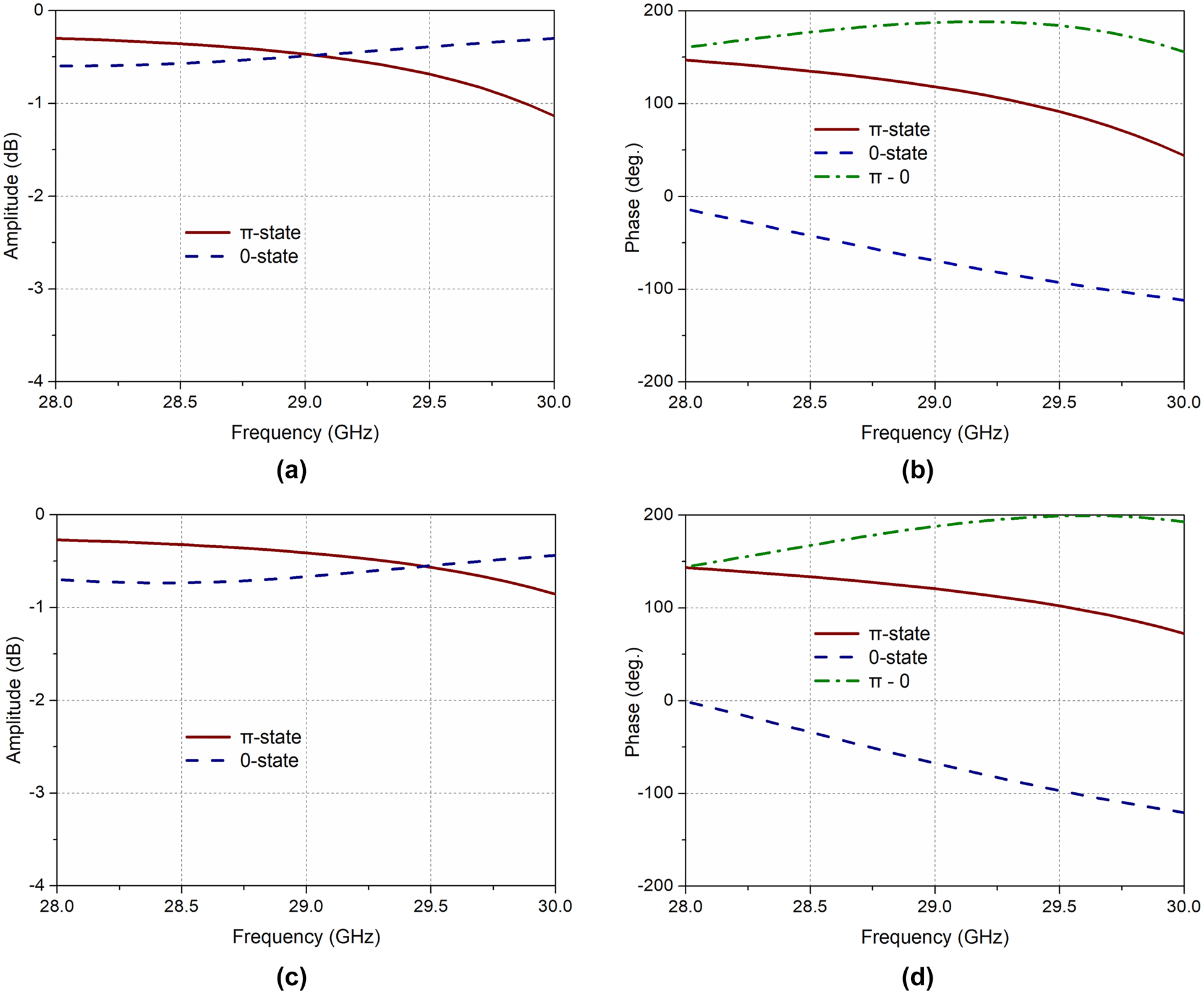

The numerical simulation of the proposed mmWave unit is carried out with the help of the commercial software package CST Microwave Studio by using unit cell boundary conditions along with the Floquet-port excitations [43]. The simulated reflection coefficients of the metasurface unit, in terms of both amplitude and phase, for the binary states are given in Figure 3. For a normal incidence EM wave, the unit reflection loss is less than 1.1 dB (0.6 dB) from 28 to 30 GHz when the reconfigurable unit is operating at the π-state (0-state), as seen in Figure 3(a). Moreover, Figure 3(b) shows the perfect binary phase modulation with a stable phase difference around 180° for the two states in the entire band from 28 GHz to 30 GHz. The proposed reconfigurable unit also shows excellent angular tolerance. As seen in Figure 3(c) and (d), for an oblique incidence wave with incidence angle θ = 30°, the reflection losses are less than 0.8 dB while keeping stable phase difference between the binary states, with very small deviation within the operation frequency band. In general, the proposed mmWave metasurface unit can achieve excellent 1 bit phase modulation with very low reflection loss, making it appropriate for the overall programmable metasurface design.

Simulated reflection coefficients of the unit.

(a) Amplitude and (b) phase for both π/0 states with normal incidence. (c) Amplitude and (d) phase for both π/0 states with incidence angle θ = 30°.

4 OAM metasurface design

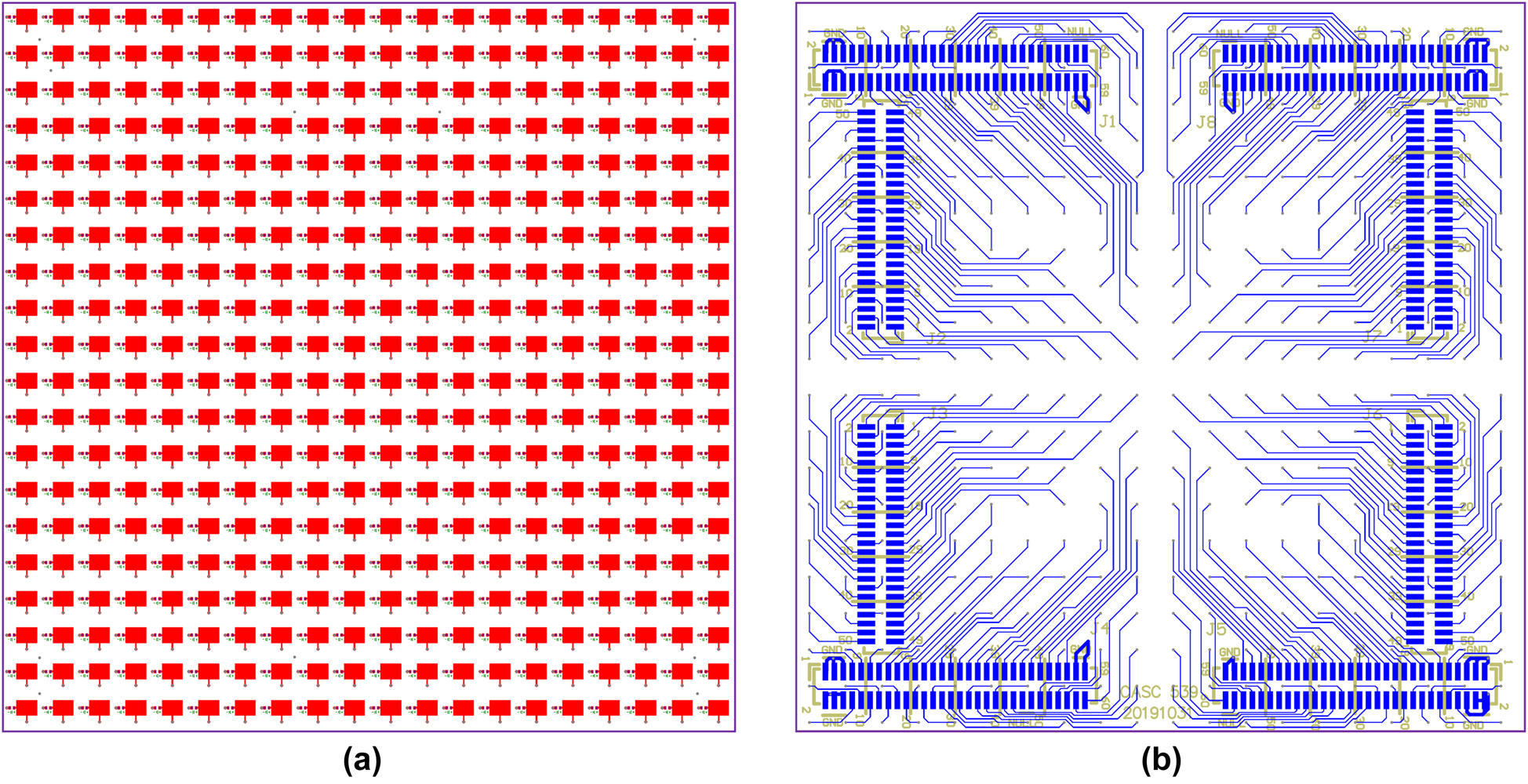

Based on the proposed reconfigurable unit, a programmable mmWave metasurface is designed and fabricated with 20 × 20 units, and the overall aperture is 103.4 mm × 103.4 mm. A standard waveguide horn (WR-28) is positioned in the central axis of the metasurface and utilized as the focal source for the metasurface aperture illumination, and the radiation gain of 11.8 dB along with the 3 dB beamwidth of 48° are obtained for the feed horn at 29 GHz. Since each unit of the metasurface is integrated with a PIN diode, a total of 400 PIN diodes are employed to provide the individual phase modulation through the bottom bias layer network.

The 3D topology diagram of the metasurface is shown in Figure 1. The top reflective metasurface patches along with the bottom bias layer network of the proposed metasurface are also provided in Figure 4. In order to simplify the bottom bias layer design layout and minimize the bias line interference, the bias layer network is divided into four symmetric parts, as shown in Figure 4(b).

Overall configuration of the proposed metasurface with 20 × 20 units.

(a) Top layer with the reflective patches. (b) Bottom layer with bias layer network layout.

As mentioned earlier, vortex beams have a rotational phase profile associated with azimuth angle, that is

where l is the designed OAM mode number, λ is the free-space wavelength at the designed frequency, and F is the focal length of the feed phase center. Moreover, since only binary phase states are available for the reconfigurable unit, the compensation phases should be furtherly quantized into two coding states according to

In the conventional reflective metasurface designs, the feed location for the focal source should be elaborately designed, since the aperture efficiency is directly influenced by the focal length, which lies mainly on two factors, including the spillover efficiency and the illumination efficiency. The spillover efficiency attributes to the radiated power which is intercepted by the metasurface aperture relative to the total radiated power from the feeder, while the illumination efficiency is related to the asymmetrical distribution of the EM field caused by the field amplitude tapering across the metasurface [45]. When the feeder horn is set near the metasurface plane, an increscent spillover efficiency along with a decreased illumination efficiency would be produced. Correspondingly, the reduced spillover efficiency along with the increased illumination efficiency would be obtained for larger feed focal length. To make a tradeoff between the spillover efficiency and the illumination efficiency for a higher metasurface aperture efficiency, the feed horn antenna is placed with a focal length of F = 12λ = 62.04 mm, corresponding to an edge taper of approximate −10 dB.

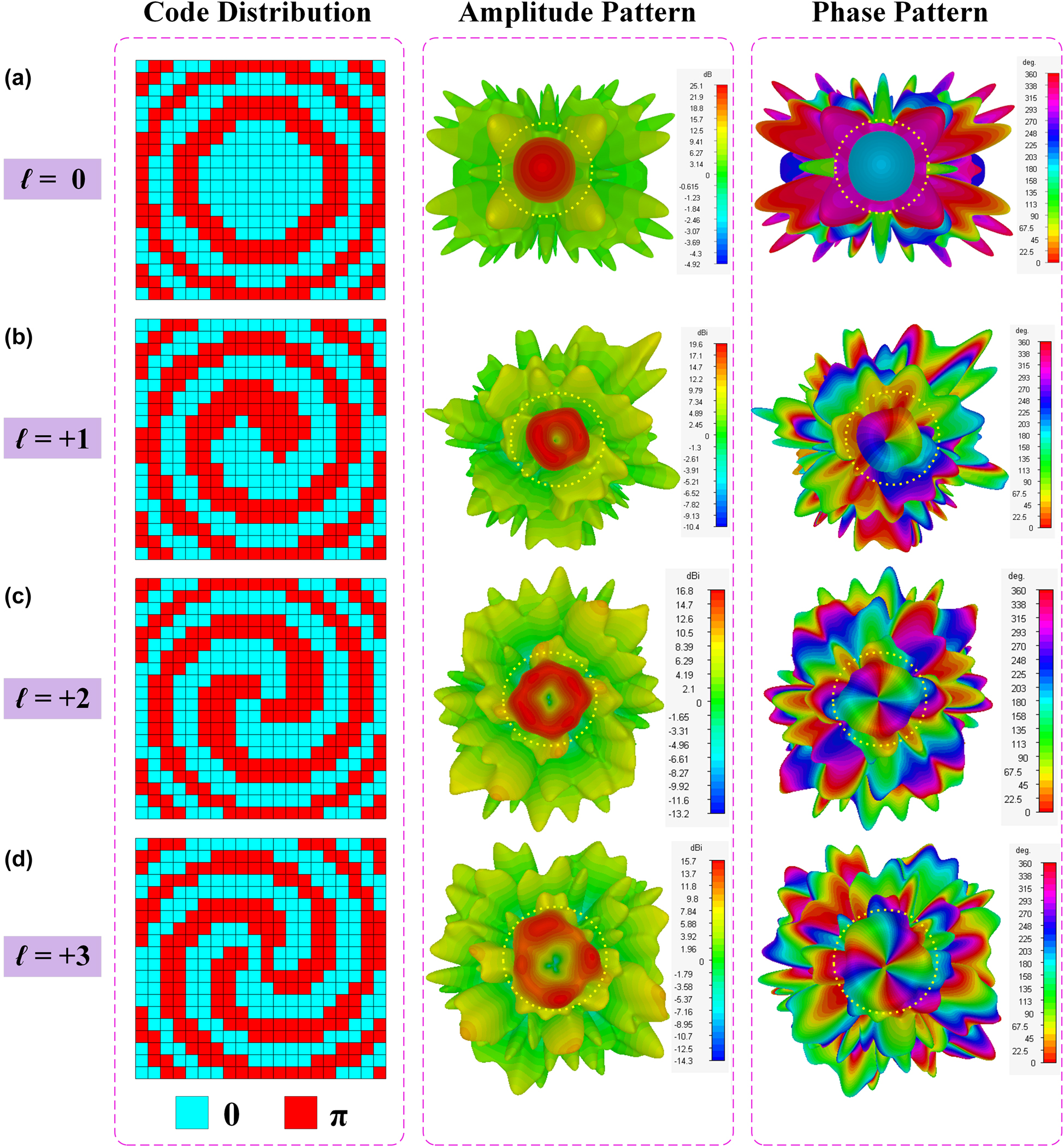

To make a primary verification for the proposed mmWave programmable metasurface, the generations of four converged vortex beams, including OAM modes l = 0, l = +1, l = +2, and l = +3, are numerically studied, as shown in Figure 5. The optimal quantized code distributions for the four modes are presented in the first column of Figure 5, which are performed according to Eq. (2) and clearly exhibit the vortex configurations for all nonzero OAM modes. The simulated far-field radiation amplitude patterns for the four OAM beams are provided in the second column of Figure 5, where conical-shaped patterns of high-intensity radiation are clearly presented for nonzero OAM modes, while a high-gain directional pencil beam is stimulated for the 0th mode. The simulated far-field phase patterns for the four modes are revealed in the third column of Figure 5. The typical vortex-shaped phase fronts along with on-axis phase singularities are clearly demonstrated for nonzero OAM modes. It is worth noting that, the radiation characters of the three negative-mode OAM beams, including modes l = −3, l = −2, and l = −1, could also be derived, whose phase profiles are directly opposite to those OAM beams with positive mode numbers, based on the conventional mirror image principle.

Code distributions and simulated radiation patterns for different OAM modes.

(a) OAM mode l = 0. (b) OAM mode l = +1. (c) OAM mode l = +2. (d) OAM mode l = +3.

5 Experimental verification

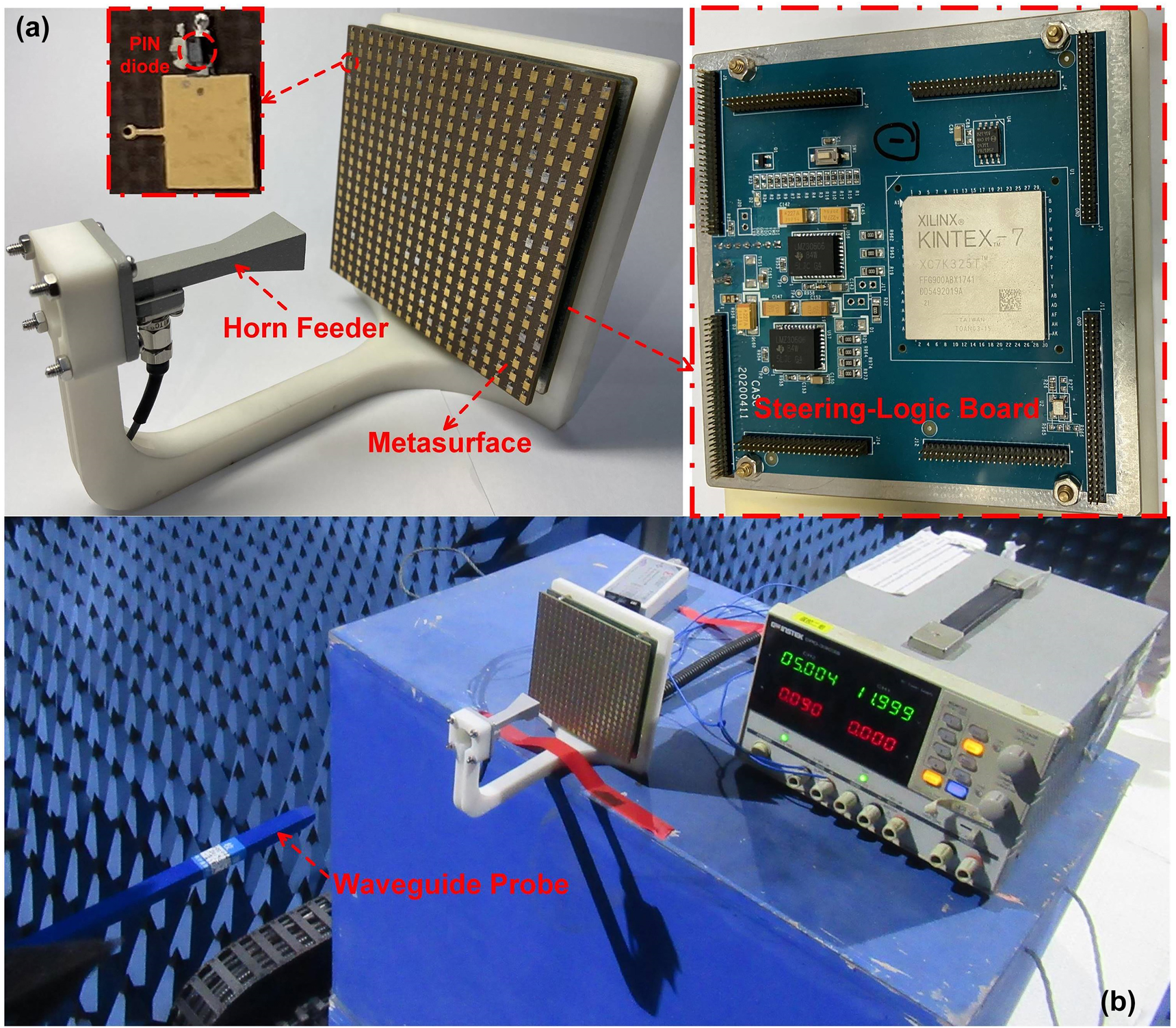

To further inspect and validate the actual functions of the proposed programmable metasurface for stimulating dynamical multi-mode mmWave OAM beams, the metasurface prototype with 20 × 20 units was manufactured. A pyramid horn feeder is introduced to illuminate the overall metasurface aperture, and a steering-logic board is integrated at the back of the metasurface. The metasurface along with horn feeder as well as the steering-logic board are all mounted onto a designed polyethylene bracket, as shown in Figure 6. The metasurface is connected and fixed with the steering-logic board through eight pairs of 1.27 mm SMT header connectors. In order to enhance the practicability of the proposed metasurface, the steering-logic board is carefully constructed with the same dimensions of the metasurface through miniaturized designs, thus a compact size can be obtained with the excellent expansibility for the larger metasurface array.

Fabricated prototype of the mmWave programmable metasurface.

(a) Metasurface along with the horn feeder as well as the steering-logic board. (b) Experimental setup with a waveguide probe in near field chamber.

In order to obtain the dynamic OAM operation, the state of each PIN diode is modulated with the steering-logic board through the bias layer network. The whole steering-logic board is powered by an external voltage-stabilized source with a 5 V voltage input supply. The FPGA, Xilinx Kintex-7, is adopted as the host processing system in order to regulate the control signal in parallel for all 400 PIN diodes of the metasurface within the assigned clock signals, according to the optimal quantized code distributions. For the π-state, a designed bias current 10 mA along with a positive DC-biasing voltage +1.3 V are supplied for the PIN diode through the steering-logic board; for the 0-state, a negative DC-biasing voltage with neglectable current are provided. Since typically half of the 400 PIN diodes are operating at the π-state during the dynamic OAM modulation, the average power consumption of the steering-logic board can thus be estimated to be only 2.6 W.

The measurements of the proposed mmWave programmable metasurface are carried out by using a 3D platform in the near-field anechoic chamber as shown in Figure 6(b), and the performances of the generated OAM beams are calibrated accurately by employing an open-ended waveguide probe to acquire the near-field data in both amplitude and phase. In the measurement, the open-ended waveguide probe is placed behind the horn feeder with a distance of 270 mm away from the programmable metasurface, and both the open-ended probe and the horn feeder are connected to the two ports of the PNA network analyzer (Keysight N5222A). The near-field scanning plane is comprised of an overall range of 202.5 mm × 202.5 mm, and discretized into 45 × 45 sampling regions, with a scanning resolution less than half wavelength of 4.5 mm in both x and y directions. In order to verify the practical applicability of the proposed metasurface, the measured far-field radiation full-hemisphere amplitude and phase patterns are further calculated from the planar near-field measurements by using the Fourier transform integral [46].

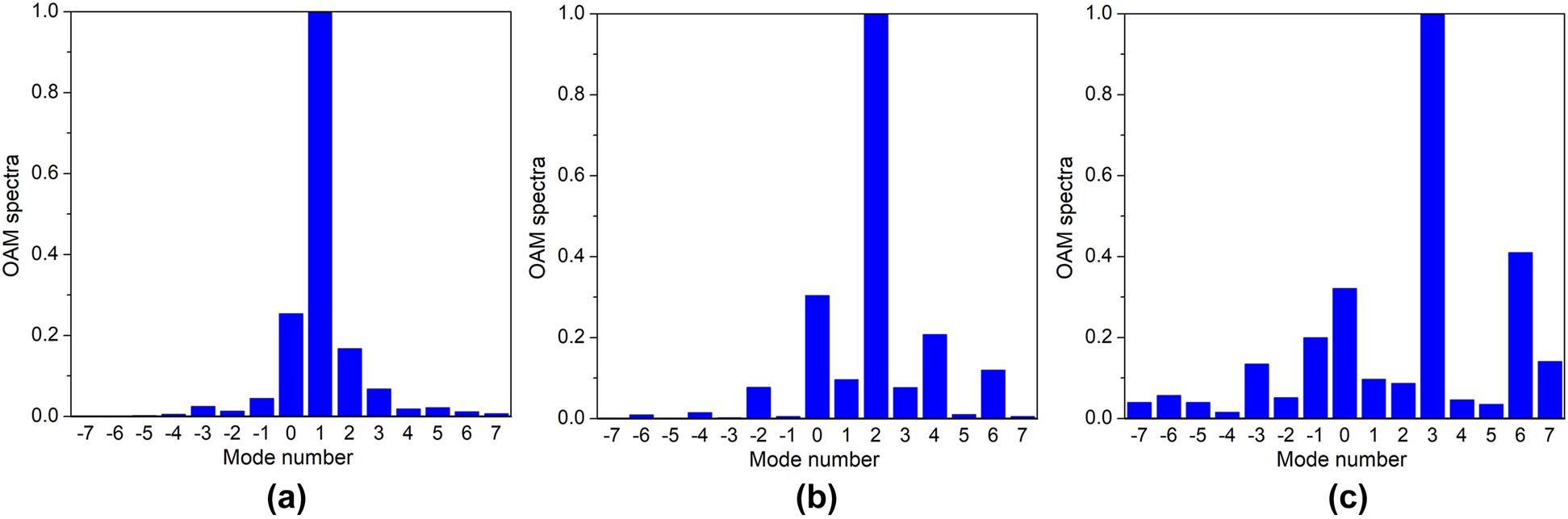

Figure 7 presents the measured far-field amplitude and phase distributions for the four modes l = 0, l = +1, l = +2, and l = +3. As observed, a measured gain over 24.2 dB is stimulated for the zero-mode pencil beam, and the aperture efficiency is in excess of 20.9%. The characteristic vortex phase fronts as well as the on-axis phase singularities are exhibited for the nonzero OAM modes, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed programmable metasurface for dynamic mmWave OAM beam conversion, and the spatial area of the non-radiation region for the vortex beam is also growing as the OAM mode number increases. There is some aliasing shown in the far-field measured results when comparing with the simulated ones, which is primarily due to the blockage of the reflective waves caused by the polyethylene bracket. Such a problem is more severe for the mmWaves with shorter wavelengths. Another minor factor may attribute to the limited binary phase resolutions of the proposed 1 bit reconfigurable unit of the metasurface, where continuous phase variations are typically required. The total efficiency can be reduced, since the quantization loss for 1 bit metasurface is approximately 3 dB when comparing with that of continuous phase variations [47]. Nevertheless, our previous work of transmissive programmable metasurface [39] has verified that, despite a slight effect of the mode purity, the feasibility and validity of generating multi-mode OAM beams are undoubted even in a 1 bit programmable metasurface. To furtherly evaluate the OAM mode purity, the OAM mode spectra of the generated OAM beams have been calculated, and the Fourier relationship is employed according to the following equation [48],

Far-field experimental results of the fabricated metasurface for different OAM modes. Amplitude: (a) l = 0, (b) l = +1, (c) l = +2, (d) l = +3. Phase: (e) l = 0, (f) l = +1, (g) l = +2, (h) l = +3.

The OAM mode spectra are revealed as shown in Figure 8, and the desired OAM modes are in a relatively dominant position when comparing with the parasitic ones for all three OAM modes.

OAM spectra for different modes: (a) l = +1, (b) l = +2, (c) l = +3.

6 Conclusions

In summary, a reflective programmable metasurface constructed from reconfigurable units with 1 bit phase modulation has been presented for stimulating multi-mode mmWave vortex beams dynamically. Through configuration integration of a PIN diode within the radiation patch for modulating the unit resonance property, both low reflection losses and stabilized inverse phase states were obtained for the binary unit coding states within the operation mmWave band. Based on the proposed reconfigurable units, a dynamic programmable metasurface operating at 28–30 GHz with 20 × 20 units was designed and fabricated. The generation of four-mode vortex beams, including OAM modes l = 0, l = +1, l = +2, and l = +3, is dynamically stimulated via the steering-logic board, which demonstrates the effectiveness of our proposed design. The proposed mmWave OAM metasurface could be useful for the hybrid communications of both mmWave and multi-mode OAM technologies in the future.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the submitted manuscript.

-

Research funding: Sponsored by Shanghai Sailing Program (20YF1447000), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62071291 and 51777168).

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] D. Dardari and V. Tralli, “High-speed indoor wireless communications at 60 GHz with coded OFDM,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 47, pp. 1709–1721, 1999, https://doi.org/10.1109/26.803506.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] J. A. Zhang, X. Huang, V. Dyadyuk, and Y. J. Guo, “Massive hybrid antenna array for millimeter-wave cellular communications,” IEEE Wireless Commun., vol. 22, pp. 79–87, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/mwc.2015.7054722.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] B. Ai, A. F. Molisch, M. Rupp, and Z.-D. Zhong, “5G key technologies for smart railways,” Proc. IEEE, vol. 108, pp. 856–893, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/jproc.2020.2988595.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] L. Yan, X. Fang, X. Wang, and B. Ai, “AI-enabled sub-6 GHz and mm-wave hybrid communications: considerations for use with future HSR wireless systems,” IEEE Veh. Technol. Mag., vol. 15, pp. 59–67, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/mvt.2020.2969528.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Y. Zhang, J. Deng, M. Li, D. Sun, and L. Guo, “A MIMO dielectric resonator antenna with improved isolation for 5G mm-Wave applications,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 18, pp. 747–751, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2019.2901961.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] A. Desai, C. D. Bui, J. Patel, T. Upadhyaya, G. Byun, and T. K. Nguyen, “Compact wideband four element optically transparent MIMO Antenna for mm-wave 5G applications,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 194206–194217, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.3033314.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] N. Ojaroudiparchin, M. Shen, S. Zhang, and G. F. Pedersen, “A switchable 3D-coverage-phased array antenna package for 5G mobile terminals,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 15, pp. 1747–1750, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2016.2532607.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] H. Afzal, R. Abedi, R. Kananizadeh, P. Heydari, and O. Momeni, “An mm-Wave scalable PLL-coupled array for phased-array applications in 65 nm CMOS,” IEEE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 69, pp. 1439–1452, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmtt.2020.3039517.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] A. A. Amin and S. Y. Shin, “Capacity analysis of cooperative NOMA-OAM-MIMO based full-duplex relaying for 6G,” IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett., vol. 10, pp. 1395–1399, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/lwc.2021.3068654.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] L. Allen, M. W. Beijersbergen, R. J. C. Spreeuw, and J. P. Woerdman, “Optical angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre–Gauss laser modes,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 45, pp. 8185–8189, 1992, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.45.8185.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] X. Bai, X. Liang, J. Li, et al.., “Experimental array for generating dual circularly-polarized dual-mode OAM radio beams,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, p. 40099, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40099.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] M. V. Berry, “Optical vortices evolving from helicoidal integer and fractional phase steps,” J. Opt. Pure Appl. Opt., vol. 6, pp. 259–268, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1088/1464-4258/6/2/018.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] J. Wang, J. Yang, I. M. Fazal, et al.., “Terabit free-space data transmission employing orbital angular momentum multiplexing,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 6, pp. 488–496, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2012.138.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] X. Chen, W. Xue, H. Shi, J. Yi, and W. E. I. Sha, “Orbital angular momentum multiplexing in highly reverberant environments,” IEEE Microw. Wireless Compon. Lett., vol. 30, pp. 112–115, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/lmwc.2019.2952975.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] X. Bai, X. Liang, J. Li, et al.., “Rotman lens-based circular array for generating five-mode OAM radio beams,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, p. 27815, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27815.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] F. Bi, Z. Ba, and X. Wang, “Metasurface-based broadband orbital angular momentum generator in millimeter wave region,” Opt. Express, vol. 26, pp. 25693–25705, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.025693.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Y. Wang, Y. Ge, Z. Chen, et al.., “Broadband high-efficiency ultrathin metasurfaces with simultaneous independent control of transmission and reflection amplitudes and phases,” IEEE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 70, pp. 254–263, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmtt.2021.3119376.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] T. Hu, Y. Wang, X. Liao, and J. Zhang, “OAM-based beam selection for indoor millimeter wave MU-MIMO systems,” IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 25, pp. 1702–1706, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/lcomm.2021.3049457.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] W. Cheng, H. Zhang, L. Liang, H. Jing, and Z. Li, “Orbital-angular-momentum embedded massive MIMO: achieving multiplicative spectrum-efficiency for mmWave communications,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 2732–2745, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2017.2785125.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] J. Wu, Z. Zhang, X. Ren, Z. Huang, and X. Wu, “A broadband electronically mode-reconfigurable orbital angular momentum metasurface antenna,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 18, pp. 1482–1486, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2019.2920695.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] K. Liu, H. Liu, Y. Qin, et al.., “Generation of OAM beams using phased array in the microwave band,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 64, pp. 3850–3857, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2016.2589960.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Y. Shuang, H. Zhao, W. Ji, T. J. Cui, and L. Li, “Programmable high-order OAM-carrying beams for direct-modulation wireless communications,” IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst., vol. 10, pp. 29–37, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/jetcas.2020.2973391.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] S. Liu, H. X. Xu, H. C. Zhang, and T. J. Cui, “Tunable ultrathin mantle cloak via varactor-diode-loaded metasurface,” Opt. Express, vol. 22, pp. 13403–13417, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.22.013403.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] K. Chen, N. Zhang, G. Ding, J. Zhao, T. Jiang, and Y. Feng, “Active anisotropic coding metasurface with independent real-time reconfigurability for dual polarized waves,” Adv. Mater. Technol., vol. 5, p. 1900930, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201900930.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] J. Han, L. Li, S. Tian, G. Liu, H. Liu, and Y. Shi, “Millimeter-wave imaging using 1 bit programmable metasurface: simulation model, design, and experiment,” IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Circuits Syst., vol. 10, pp. 52–61, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/jetcas.2020.2973466.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] H. Xu, T. Cai, Y. Zhuang, Q. Peng, G. Wang, and J. Liang, “Dual-mode transmissive metasurface and its applications in multibeam transmitarray,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 65, pp. 1797–1806, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2017.2673814.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] H. Yang, F. Yang, S. Xu, et al.., “A 1 bit 10 × 10 reconfigurable reflectarray antenna: design, optimization, and experiment,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 64, pp. 2246–2254, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2016.2550178.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Z. Wang, H. Zhang, H. Zhao, T. J. Cui, and L. Li, “Intelligent electromagnetic metasurface camera: system design and experimental results,” Nanophotonics, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0665.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Y. Yuan, K. Zhang, B. Ratni, et al.., “Independent phase modulation for quadruplex polarization channels enabled by chirality-assisted geometric-phase metasurfaces,” Nat. Commun., vol. 11, p. 4186, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17773-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] L. Zhang, X. Q. Chen, R. W. Shao, et al.., “Breaking reciprocity with space-time-coding digital metasurfaces,” Adv. Mater., vol. 31, p. 1904069, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201904069.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] L. Li, T. J. Cui, W. Ji, et al.., “Electromagnetic reprogrammable coding-metasurface holograms,” Nat. Commun., vol. 8, p. 197, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00164-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] X. Guo, Y. Ding, Y. Duan, and X. Ni, “Nonreciprocal metasurface with space-time phase modulation,” Light: Sci. Appl., vol. 8, p. 123, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-019-0225-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] H. Rajabalipanah, A. Abdolali, S. Iqbal, L. Zhang, and T. J. Cui, “Analog signal processing through space-time digital metasurfaces,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, pp. 1753–1764, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0006.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] J. Han, L. Li, H. Yi, and Y. Shi, “1 bit digital orbital angular momentum vortex beam generator based on a coding reflective metasurface,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 8, pp. 3470–34788, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.8.003470.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] J. Han, L. Li, H. Yi, and W. Xue, “Versatile orbital angular momentum vortex beam generator based on reconfigurable reflective metasurface,” Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., vol. 57, p. 120303, 2018, https://doi.org/10.7567/jjap.57.120303.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Z. Wang, X. Pan, F. Yang, S. Xu, and M. Li, “Real-time mode switching and beam scanning of high-gain OAM waves using a 1 bit reconfigurable reflectarray antenna,” Electronics, vol. 9, p. 2181, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9122181.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] B. Liu, Y. He, S. W. Wong, and Y. Li, “Multifunctional vortex beam generation by a dynamic reflective metasurface,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 9, p. 2001689, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202001689.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] K. Guo, Q. Zheng, Z. Yin, and Z. Guo, “Generation of mode-reconfigurable and frequency-adjustable OAM beams using dynamic reflective metasurface,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 75523–75529, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.2988914.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] X. Bai, F. Kong, Y. Sun, et al.., “High-efficiency transmissive programmable metasurface for multimode OAM generation,” Adv. Opt. Mater., vol. 8, p. 2000570, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202000570.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] I. Piekarz, J. Sorocki, M. T. Craton, K. Wincza, S. Gruszczynski, and J. Papapolymerou, “Application of aerosol jet 3D printing with conductive and nonconductive inks for manufacturing mmWave circuits,” IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol., vol. 9, pp. 586–595, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/tcpmt.2018.2889698.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] A. Dewantari, J. Kim, I. Scherbatko, and M. H. Ka, “A sidelobe level reduction method for mm-Wave substrate integrated waveguide slot array antenna,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 18, pp. 1557–1561, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2019.2922307.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] MACOM, MACOM MADP-000907-14020 solderable AlGaAs flip chip PIN diodes [Online]. Available at: https://www.macom.com/products/product-detail/MADP-000907-14020P [accessed: May, 2018].Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Computer Simulation Technology, CST Microwave Studio 2016 [Online]. Available at: https://www.cst.com.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] B. Fang, Z. Wang, S. Gao, S. Zhu, and T. Li, “Manipulating guided wave radiation with integrated geometric metasurface,” Nanophotonics, 2021, Art no. 000010151520210466, https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0466.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] P. Nayeri, F. Yang, and A. Z. Elsherbeni, “System design and aperture efficiency analysis,” in Reflectarray Antennas (Theory, Designs, and Applications), Pondicherry, India, John Wiley & Sons, 2018.10.1002/9781118846728.ch3Suche in Google Scholar

[46] R. J. Pogorzelski, “Full hemisphere aperture-antenna far-field patterns from planar near-field measurements,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 67, pp. 1170–1179, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2018.2880030.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] H. Yang, F. Yang, S. Xu, et al.., “A study of phase quantization effects for reconfigurable reflectarray antennas,” IEEE Antenn. Wireless Propag. Lett., vol. 16, pp. 302–305, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/lawp.2016.2574118.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] S. Jiang, C. Chen, H. Zhang, and W. Chen, “Achromatic electromagnetic metasurface for generating a vortex wave with orbital angular momentum (OAM),” Opt. Express, vol. 26, pp. 6466–6477, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.006466.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2022 Xudong Bai et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Gaptronics: multilevel photonics applications spanning zero-nanometer limits

- Ultrafast photonics applications of emerging 2D-Xenes beyond graphene

- Research Articles

- Nonlocal effects in temporal metamaterials

- Pattern-tunable synthetic gauge fields in topological photonic graphene

- Generalized temporal transfer matrix method: a systematic approach to solving electromagnetic wave scattering in temporally stratified structures

- Femtosecond imaging of spatial deformation of surface plasmon polariton wave packet during resonant interaction with nanocavity

- Probing the long-lived photo-generated charge carriers in transition metal dichalcogenides by time-resolved microwave photoconductivity

- Second-order topological phases in C 4v -symmetric photonic crystals beyond the two-dimensional Su-Schrieffer–Heeger model

- Full-visible-spectrum perovskite quantum dots by anion exchange resin assisted synthesis

- Multidimensional engineered metasurface for ultrafast terahertz switching at frequency-agile channels

- High efficiency and large optical anisotropy in the high-order nonlinear processes of 2D perovskite nanosheets

- Dynamic millimeter-wave OAM beam generation through programmable metasurface

- Intelligent metasurface with frequency recognition for adaptive manipulation of electromagnetic wave

- Singularities splitting phenomenon for the superposition of hybrid orders structured lights and the corresponding interference discrimination method

- Inverse-designed waveguide-based biosensor for high-sensitivity, single-frequency detection of biomolecules

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Gaptronics: multilevel photonics applications spanning zero-nanometer limits

- Ultrafast photonics applications of emerging 2D-Xenes beyond graphene

- Research Articles

- Nonlocal effects in temporal metamaterials

- Pattern-tunable synthetic gauge fields in topological photonic graphene

- Generalized temporal transfer matrix method: a systematic approach to solving electromagnetic wave scattering in temporally stratified structures

- Femtosecond imaging of spatial deformation of surface plasmon polariton wave packet during resonant interaction with nanocavity

- Probing the long-lived photo-generated charge carriers in transition metal dichalcogenides by time-resolved microwave photoconductivity

- Second-order topological phases in C 4v -symmetric photonic crystals beyond the two-dimensional Su-Schrieffer–Heeger model

- Full-visible-spectrum perovskite quantum dots by anion exchange resin assisted synthesis

- Multidimensional engineered metasurface for ultrafast terahertz switching at frequency-agile channels

- High efficiency and large optical anisotropy in the high-order nonlinear processes of 2D perovskite nanosheets

- Dynamic millimeter-wave OAM beam generation through programmable metasurface

- Intelligent metasurface with frequency recognition for adaptive manipulation of electromagnetic wave

- Singularities splitting phenomenon for the superposition of hybrid orders structured lights and the corresponding interference discrimination method

- Inverse-designed waveguide-based biosensor for high-sensitivity, single-frequency detection of biomolecules