Abstract

Nonlocality is a fundamental concept in photonics. For instance, nonlocal wave-matter interactions in spatially modulated metamaterials enable novel effects, such as giant electromagnetic chirality, artificial magnetism, and negative refraction. Here, we investigate the effects induced by spatial nonlocality in temporal metamaterials, i.e., media with a dielectric permittivity rapidly modulated in time. Via a rigorous multiscale approach, we introduce a general and compact formalism for the nonlocal effective medium theory of temporally periodic metamaterials. In particular, we study two scenarios: (i) a periodic temporal modulation, and (ii) a temporal boundary where the permittivity is abruptly changed in time and subject to periodic modulation. We show that these configurations can give rise to peculiar nonlocal effects, and we highlight the similarities and differences with respect to the spatial-metamaterial counterparts. Interestingly, by tailoring the effective boundary wave-matter interactions, we also identify an intriguing configuration for which a temporal metamaterial can perform the first-order derivative of an incident wavepacket. Our theoretical results, backed by full-wave numerical simulations, introduce key physical ingredients that may pave the way for novel applications. By fully exploiting the time-reversal symmetry breaking, nonlocal temporal metamaterials promise a great potential for efficient, tunable optical computing devices.

1 Introduction

Spatial dispersion [1, 2] implies that the electromagnetic (EM) constitutive relationships are nonlocal, i.e., the electric and/or magnetic inductions at a given point also depend on the fields applied in a spatial neighborhood (and, because of causality, at previous time instants). From a mathematical viewpoint, this can be modeled in terms of spatial derivatives in the constitutive relationships or, equivalently, via wavevector-dependent constitutive parameters in the reciprocal domain. Such behavior is typically negligible in most natural materials; nevertheless, it can become a dominant effect in artificial materials, such as metamaterials and photonic crystals, characterized by spatially periodic (or almost periodic) arrangements of basic constituents [3–6]. Although in some cases nonlocality is viewed as a detrimental effect to suppress or mitigate [7], its proper harnessing can be very beneficial in a variety of application scenarios, including artificial magnetism [8], chirality [6], ultrafast nonlinear optics [9], advanced dispersion engineering [10, 11], and wave-based analog computing [12].

Currently, in metamaterials engineering, there is a surge of interest in exploiting the temporal dimension as well, motivated by the increasing availability of fast, reconfigurable “meta-atoms” whose response can be dynamically modulated in time [13–16]. This has led to revisiting with renewed attention some old studies on wave interactions with time-varying media or structures [17–19], and to the demonstration of a variety of intriguing effects and applications, ranging from nonreciprocity to broadband light manipulation (see, e.g., [20–38] for a sparse sampling).

Interestingly, by exploiting the space-time duality, the concept of effective medium theory (EMT) has been translated from conventional spatial multilayers to temporal “multisteps” featuring a time-varying permittivity [30], and higher-order homogenization schemes have also been put forward to study nonlocal effects [31].

In this paper, we revisit these concepts via first-principle calculations based on a multiscale approach [6]. We show that nonlocality in temporal metamaterials can induce an effective diamagnetic response, in analogy with the nonlocal effects observed in conventional spatial metamaterials of infinite extent. Moreover, in analogy with the boundary-type nonlocal effects observed in truncated spatial metamaterials, we also consider a temporal scenario where the permittivity of an unbounded nondispersive medium is abruptly changed in time and subject to a temporally periodic modulation. Remarkably, we show that this temporal boundary can give rise to peculiar nonlocal effects which, in suitably tailored parameter regimes, can be harnessed to perform elementary analog-computing operations, such as computing the first-order derivative of an incident wavepacket. Finally, for validation, we also carry out full-wave numerical simulations, which are in good agreement with our theoretical derivations. Our results indicate that nonlocality in temporal metamaterials may play a key role in engineering novel effects in nanophotonics and optical computing.

2 Results

2.1 Nonlocal effective medium theory

Let us consider an isotropic, generally inhomogeneous, time-modulated medium, whose EM response is described by a relative dielectric permittivity periodically modulated in time, ɛ(r, t) = ɛ(r, t + τ). In our study, we assume that the operating frequencies are much lower than any material resonance frequencies, so that temporal dispersion effects can be approximately neglected [17, 39]. From Maxwell’s equations, the field dynamics can be described by the vector wave equation for the electric induction D, namely

where

with

where we have separated the fast and slow contributions, and we have assumed that the reciprocal of the relative permittivity admits the Fourier series expansion

with

along with the constitutive relationships

which are evidently nonlocal because of the presence of field derivatives. By considering the limit η → 0, it is apparent that the term proportional to η 2 in the first of Eq. (3) vanishes, and the temporal metamaterial behaves as a dielectric medium with an effective relative permittivity ɛ eff, thereby recovering the results in previous studies [30, 31]. In the simplest case of spatial homogeneity (i.e., spatially unbounded, time-varying media [30]), the first of Eq. (6) becomes

where K = 2π/(cτ) and

Next, we consider a monochromatic plane wave propagating in a temporal metamaterial, i.e.,

where

plays the role of an effective relative magnetic permeability. Note that artificial magnetism in time-modulated dielectric media has been predicted in a recent study [31], suggesting that a temporal metamaterial can behave as a resonant magneto-dielectric medium. Our results above confirm the previous findings, and establish tighter bounds on the attainable magnetic response. Specifically, for a temporally periodic metamaterial based on positive-permittivity modulation [ɛ(t) = ɛ(t + τ) > 0], it is apparent from Eq. (9) (recalling that γ ≥ 0) that only nonlocal diamagnetism with 0 < μ eff(k) < 1 can be attained, whereas resonant, paramagnetic, and μ-negative responses are forbidden.

We highlight that, as in conventional spatially modulated metamaterials, optical magnetism stems from spatial dispersion. As previously mentioned, in spatial metamaterials, nonlocality can strongly affect the EM response, and it can produce undesirable effects [7]. Conversely, in an isotropic temporal metamaterial, the spatial dispersion up to the second order (i.e., up to η 2) is fully equivalent to optical magnetism described by the effective relative magnetic permeability μ eff(k) in Eq. (9) (see the Methods Section 4.1 for further details).

For some quantitative assessments, we assume that the relative permittivity profile is given by

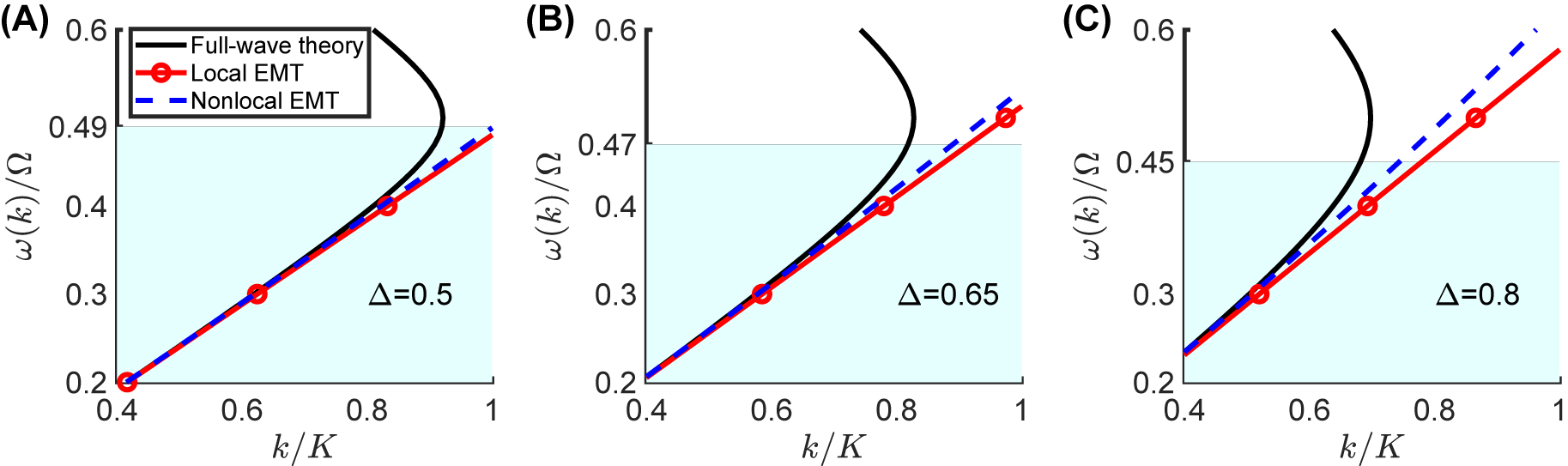

with Δ parameterizing the modulation depth, and ϕ being an arbitrary phase. To validate and calibrate the predictions of our proposed nonlocal EMT model, we compare them with the results from a rigorous full-wave theory (see the Methods Section 4.1 for further details), as well as with the conventional (local) EMT [16]. Figure 1 compares these three predictions for the dispersion relationship ω(k), for

Comparison between the predictions from the full-wave theory and both local an nonlocal EMT models for a temporal metamaterial with relative permittivity as in Eq. (10), with

(A)–(C) Normalized angular frequency ω/Ω as function of the normalized wavenumber k/K, for Δ = 0.5, 0.65, and 0.8, respectively.The light-blue shaded area indicates the region where the nonlocal EMT works well (≲10% error with respect to full-wave theory).

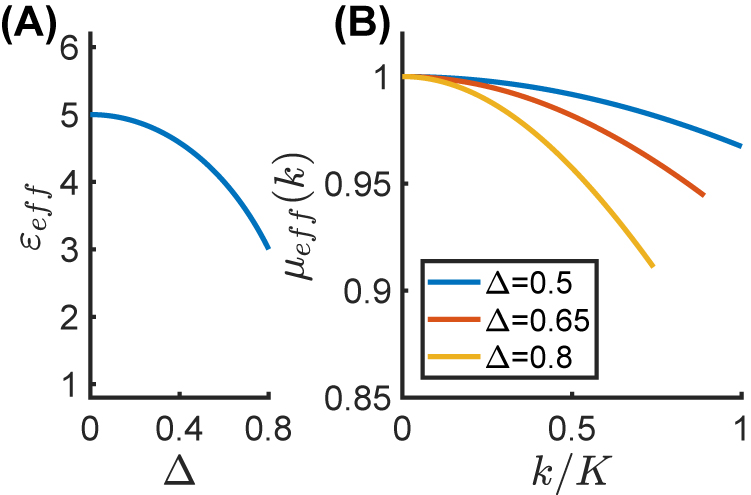

Figure 2(A) shows the effective relative permittivity ɛ eff as a function of Δ, whereas Figure 2(B) shows the effective relative permeability μ eff(k) as a function of k/K, for different values of Δ; these effective parameters are only shown within the region where the nonlocal EMT is in good agreement with the full-wave theory (corresponding to the light-blue shaded area in Figure 1). We observe that, in the case of a deep temporal modulation (e.g., Δ = 0.8), the metamaterial exhibits a significant diamagnetic response (e.g., μ eff ≃ 0.91 for k/K = 0.73).

Effective parameters for the temporal metamaterial considered in Figure 1.

(A) Effective relative permittivity ϵ eff as a function of Δ; (B) effective relative permeability μ eff(k) as a function of k/K, for different values of the modulation depth Δ. Note that μ eff(k) is only shown within the region where the nonlocal EMT holds (≲10% error with respect to full-wave theory).

2.2 Nonlocal temporal boundary

In analogy with the spatial scenario, the results derived in Section 2.1 play the role of the “bulk” response of an infinite-extent metamaterial. Since a series of recent studies on spatially truncated multilayered dielectric metamaterials (see, e.g., [40–42]) have indicated the possible onset of intriguing “boundary” effects in critical parameter regimes, it appears suggestive to explore similar effects in our temporal scenario here. To this aim, we derive the conditions at the boundary of a nonlocal temporal metamaterial. More precisely, we consider a spatially homogeneous, unbounded, temporal metamaterial exhibiting a temporal boundary at a given time instant t = t 0, at which the relative permittivity abruptly changes from a constant value ɛ 1 to a time-varying periodic function ɛ(t), viz.,

Obviously, since the medium response to modulation cannot be infinitely fast, the assumption of abrupt temporal transitions is highly idealized, and a finite rise/fall time should be considered. However, for fall/rise times much shorter than the period of the incident wave, our approach remains valid. Within this framework, it is also worth pointing out that, in our numerical simulations (see the Methods Section 4.3), we actually assume smooth transitions with sufficiently short rise/fall times in order to favor convergence. As for the canonical temporal boundary [43], where the dielectric permittivity exhibits a temporal transition between two constant values, the microscopic electric induction D and magnetic induction B remain continuous across the boundary. Here, we consider plane waves, D = 2 Re[d(k, t)eik⋅r

] and B = 2 Re[b(k, t)eik⋅r

], experiencing the temporal boundary described by Eq. (11). By enforcing the standard boundary conditions [43], and taking into account the second of Eq. (3) and the microscopic Maxwell’s curl equation

where

From Eq. (12), it is evident that, in the limit k/K → 0, the inductions d and b are continuous, and our approach reproduces the known results for the canonical temporal boundary [43]. Generally, the homogenization process can hide the asymmetry of the system. In the spatial domain, the EM chirality is washed out in the conventional homogenized response of a composite metamaterial [6, 42]. Here, the system exhibits a time-reversal symmetry breaking due to the permittivity modulation in time and, while this effect is lost in the effective “bulk” response, it is restored in the boundary conditions expressed by Eq. (12). This is somehow analogous to what is observed in spatial multilayered metamaterials, which exhibit chiral boundary effects attributable to the parity symmetry breaking [42]. The abrupt switching of the permittivity breaks the time-reversal symmetry. On the other hand, by comparison with the conventional boundary conditions (i.e., continuity of d and b at the temporal boundary), we highlight that, in Eq. (12), the term proportional to β 0 breaks explicitly the time-reversal symmetry. The nonlocality preserves the time-reversal asymmetry of the “microscopic” permittivity modulation, and this peculiar wave-matter interaction endows us with novel degrees of freedom for manipulating the wave propagation.

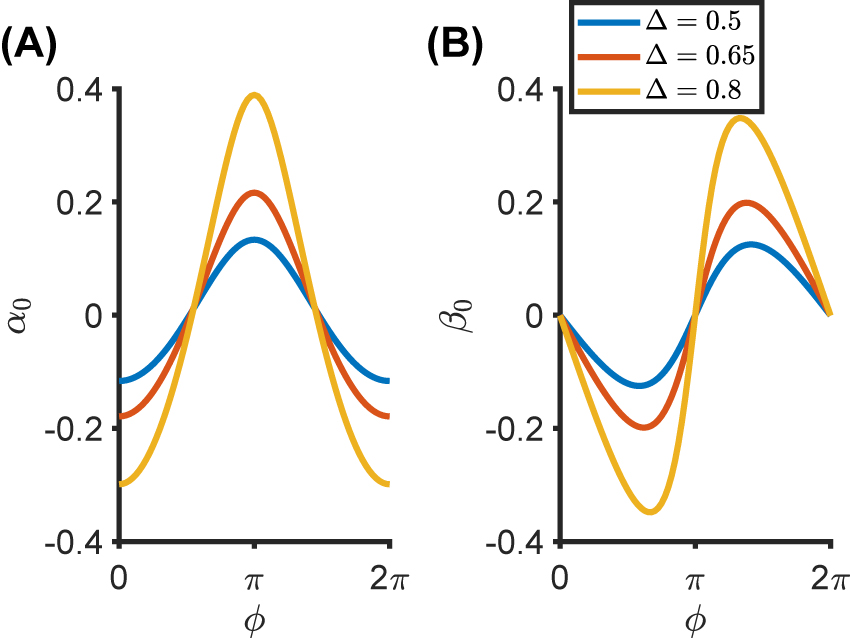

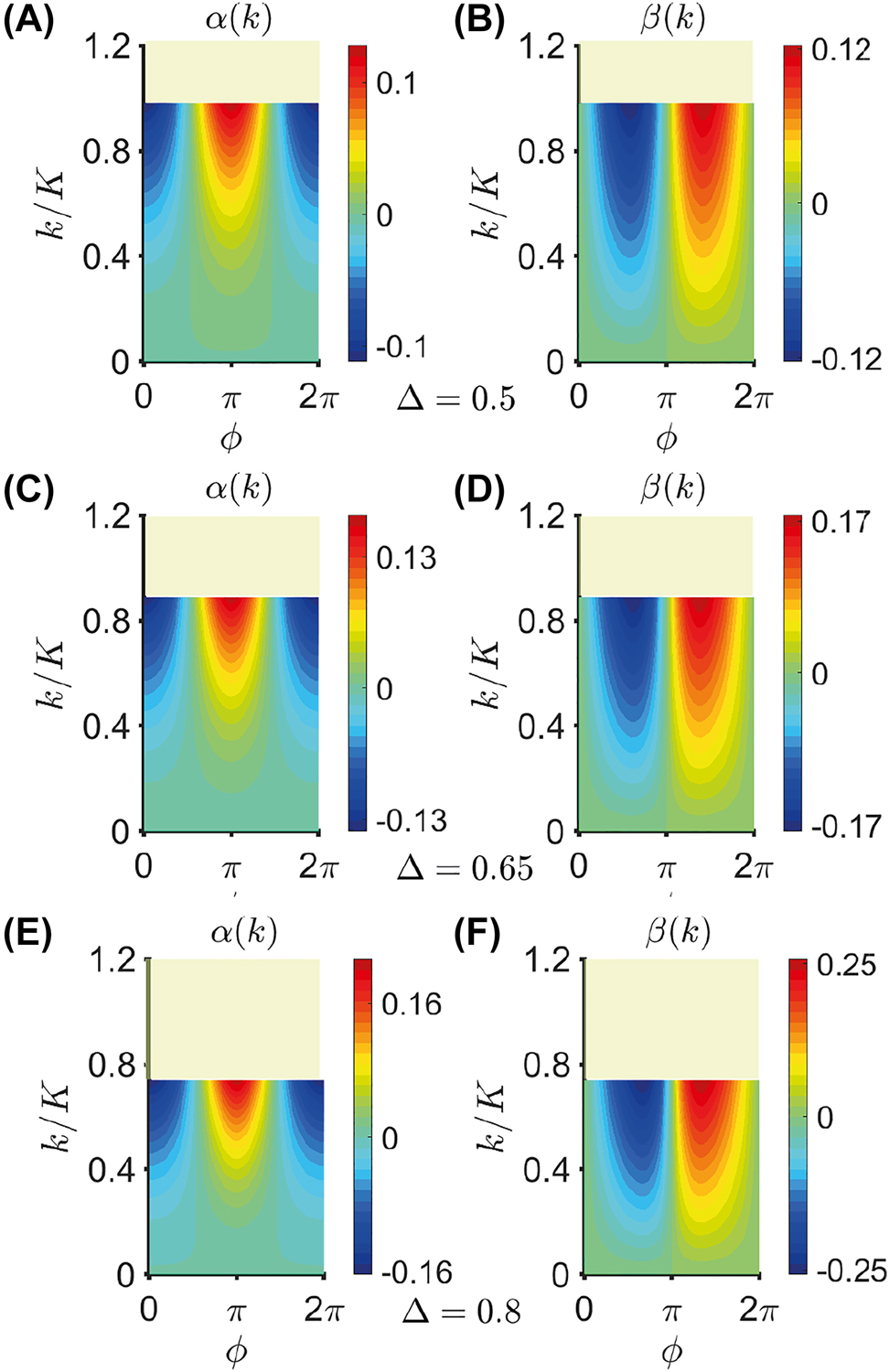

As an example, we consider once again the temporal metamaterial described by Eq. (10), with

as a function of k/K and ϕ, for Δ = 0.5 [panels (A) and (B)], Δ = 0.65 [panels (C) and (D)], and Δ = 0.8 [panels (E) and (F)]; as in previous examples, the parameters are only shown within the region where the nonlocal EMT holds (i.e., the deviation is less than 10% with respect to full-wave theory). Recalling the results in Figure 1, the larger the modulation depth Δ, the smaller the wavenumber region where the nonlocal EMT is in agreement with the full-wave theory. The results in Figure 4 indicate that the impact of nonlocality at the temporal boundary increases for deeper modulations. In particular, for Δ = 0.8, α(k) and β(k) reach the values 0.21 and 0.26, respectively, for k/K ≃ 0.74.

Nonlocal temporal boundary. (A) and (B) Nonlocal effective boundary parameters α

0 and β

0, respectively, as a function of the modulation phase ϕ. Here, t

0 = 0, and a metamaterial with the permittivity profile in Eq. (10) is considered with

Nonlocal contributions in Eq. (14) as a function of k/K and ϕ, for Δ = 0.5 ((A) and (B)), Δ = 0.65 ((C) and (D)), and Δ = 0.8 ((E) and (F)). Here, t

0 = 0 and a temporal metamaterial with the permittivity profile in Eq. (10) is considered, with

2.3 Reflection and transmission at a nonlocal temporal boundary

Let us consider a plane wave propagating in a spatially homogeneous unbounded medium with a relative permittivity as described by Eq. (11). Without loss of generality, we assume propagation along the positive z direction, and an x-polarized electric induction, i.e.

for t < t 0, and by Eq. (7) for t > t 0. As a consequence, by neglecting the fast components, the electric induction d(k, t) is merely given by

where

where

From Eq. (18), by taking into account Eqs. (15) and (7), and maintaining terms up to the first order in k/K, we obtain the corresponding expressions for the electric field

where the k-dependent terms account for the (weak) dispersion. By neglecting these nonlocal terms, we recover the well-known analytical expressions derived in previous studies on conventional (local) temporal boundaries [43].

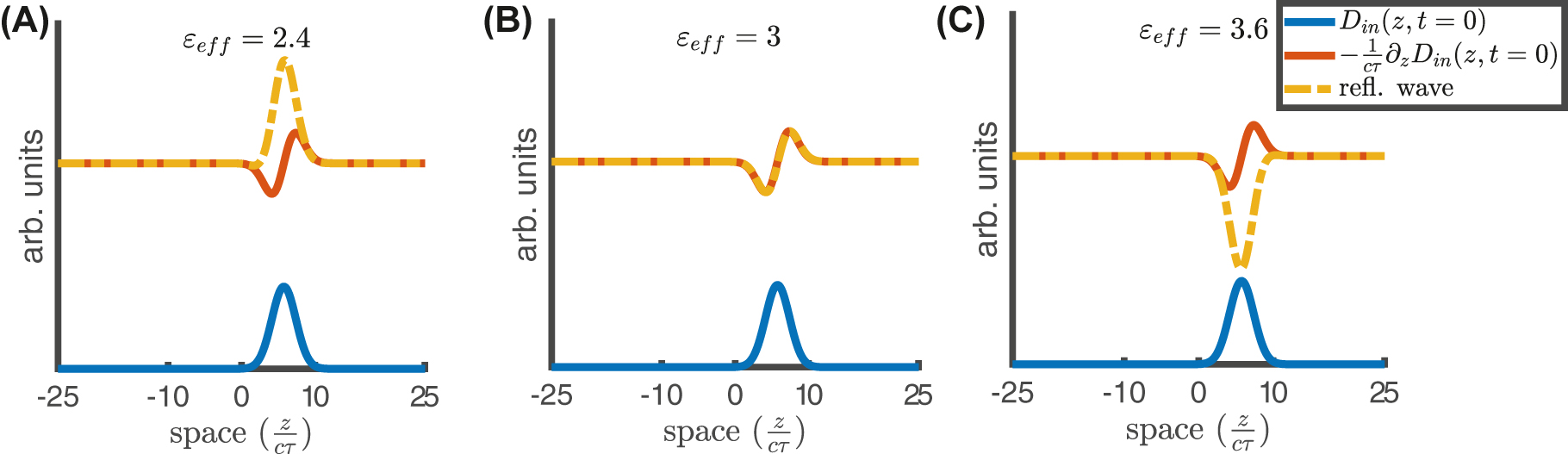

2.4 Harnessing the temporal-boundary nonlocality

As for the spatial case [10], it is insightful to explore to what extent nonlocality in temporal metamaterials can be harnessed to attain some elementary pulse-shaping or analog-computing functionalities. By inspecting Eqs. (18) and (19), it is apparent that, in the weak-dispersion regime, backward and forward fields at a nonlocal temporal boundary are dominated by a linear combination of a local (constant) term and a nonlocal correction that is proportional to k, and hence corresponds to a first derivative. Remarkably, in the temporal reflection coefficients r d(k) and r e(k), this nonlocal correction can be made dominant by enforcing the impedance-matching condition ɛ eff = ɛ 1, so that the local terms vanish. Thus, the backward waveform is proportional to the first derivative of the incident one.

Via Fourier transform, a generic wavepacket can be synthesized as the superposition of the time-harmonic modes in Eq. (16), i.e.,

with

Spatial profiles of reflected (backward) pulses D

r

(z, t

1) (t

1 ≃ 20τ) in the configuration described by Eqs. (11) and (10), with ɛ

1 = 3, t

0 = 10τ, ϕ = 3π/2, Δ = 0.8, and

As in Figure 5, but space-time maps of the electric induction D and the corresponding forward (D t ) and backward (D r ) components for ɛ eff = 2.4 ((A)–(C)), ɛ eff = 3 ((D)–(F)), and ɛ eff = 3.6 ((G)–(I)).

Finally, we validate these predictions from the nonlocal EMT model against full-wave numerical simulations (see the Methods Section 4.3 for details). Here, we consider the same EM configuration analyzed above with

Figure 7 shows the results on three cases where ϕ = 3π/2 ((A)–(C)), ϕ = 0.67π ((D)–(F)), and ϕ = π ((G)–(I)). Specifically, we compare the electric induction and electric field distributions predicted by the conventional (local), nonlocal EMT, and full-wave simulations for both cases. Panels (B), (E), and (H) show the backward pulse profiles D r/D 0 at z = −30cτ for the configurations in panels (A), (D) and (G), respectively. At the impedance matching condition, the local EMT predicts zero temporal reflection, and it does not properly describe the backward wave dynamics. For ϕ = 3π/2 and ϕ = 0.67π, our proposed nonlocal EMT is in very good agreement with the full-wave simulations. For ϕ = π, the local and nonlocal EMT predict zero temporal reflection, whereas full-wave simulations yield a very small backward reflection signal (about an order of magnitude weaker than the previous cases). In this latter case, the parameter β 0 ruling the nonlocal effect vanishes, and the temporal reflection is negligible [see Figure 3 along with the second of Eq. (18)]. Also shown in panels (C), (F) and (I) are the corresponding profiles of the normalized electric fields ɛ 0 E r/D 0. In panels (C), (F) and (I), we observe that the full-wave predictions exhibit fast modulations due to the temporal modulation of the permittivity, whereas the nonlocal EMT prediction obtained from Eq. (19) is only representative of the slow component. Clearly, Eq. (19) describe the temporal transmission and reflection coefficients of the average component of the electric field, and all fast scales are not considered.

![Figure 7:

Comparison between the backward wavepacket profiles predicted by full-wave simulations, local and non-local EMTs. The considered temporal dielectric profiles ensuring the impedance-matching conditions [i.e., the configuration described by Eqs. (11) and (10), with ɛ

1 = 3, t

0 = 10τ, Δ = 0.8, and

ε

̄

=

5

$\bar{\varepsilon }=5$

] is plotted with ϕ = 3π/2 (panel (A)), ϕ = 0.67π (panel (D)), and ϕ = π (panel (G)). Panels (B), (E), and (H) show the corresponding normalized electric inductions D

r/D

0 for the backward pulses. Panels (C), (F), and (I) show the corresponding normalized electric fields ɛ

0

E

r/D

0. All temporal profiles are evaluated at z = −30cτ.](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0605/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2021-0605_fig_007.jpg)

Comparison between the backward wavepacket profiles predicted by full-wave simulations, local and non-local EMTs. The considered temporal dielectric profiles ensuring the impedance-matching conditions [i.e., the configuration described by Eqs. (11) and (10), with ɛ

1 = 3, t

0 = 10τ, Δ = 0.8, and

Overall, the above results confirm the validity of the nonlocal EMT predictions to harness the temporal-boundary nonlocality. In the configurations with ϕ = 3π/2 and ϕ = 0.67π, the nonlocal contributions, appearing in Eqs. (18) and (19), are significant (β 0 = 0.31, −0.35 for ϕ = 3π/2, 0.67π, respectively), so that these results also confirm the possibility to attain the spatial first derivative of the incident wavepacket. Remarkably, by tailoring the modulation phase ϕ, the amplitude and the symmetry of the backward pulse can be suitably tuned. Comparing the field profiles in panels ((B) and (C)) with those in panels ((C) and (F)), it is evident that the pulse reverses its temporal symmetry profile by switching ϕ from 3π/2 to 0.67π. Quite interestingly, for ϕ = 0.67π, the relative-permittivity function ɛ b (t) is continuous, thereby indicating that the predicted nonlocal effects do not depend critically on abrupt temporal changes.

In principle, by exploiting more complex modulation schemes with additional degrees of freedom (e.g., temporal dielectric structures with multiple harmonics), it could be possible to tailor the parameters so as to perform higher-derivative orders (and their linear combinations).

3 Conclusions

In summary, via a rigorous multiscale approach, we have developed a nonlocal EMT for temporal metamaterials characterized by permittivity profiles rapidly modulated in time. In analogy with the spatial case, we have elucidated the nonlocal effects, occurring in specific parameter regimes, manifested as an effective diamagnetic response and the possibility to perform basic signal-processing (e.g., first derivative), respectively. In good agreement with full-wave numerical simulations, these results bring about new perspectives and degrees of freedom in the design of temporal metamaterials for tunable nanophotonics and optical computing.

Current and future studies are aimed at exploring more general spatio-temporal modulation schemes, such as multifrequency and traveling-wave [24, 37]. Also crucial from the application viewpoint is the exploration of possible implementations, based on technological platforms that have been demonstrated at microwave [45], terahertz [46], and optical [47] frequencies. Finally, of great interest is a study of the possible effects of topological properties, as in photonic time crystals [48, 49], which may enable novel advanced functionalities.

4 Methods

4.1 Nonlocal magnetism

Recalling that the effective Maxwell’s equations are invariant with respect to the Serdyukov–Fedorov transformation [50]

where

4.2 Rigorous dispersion relationship in time-periodic varying media

Following the rigorous approach in [51], we focus on the wave equation describing the electric field dynamics in a time-periodic varying medium. The propagation of a plane wave

where ɛ(t) = ɛ(t + τ). Since the permittivity is periodic in time, this equation admits Bloch-type modes

where

4.3 Full-wave simulations

We consider an arbitrary wavepacket propagating in a spatially homogeneous unbounded, time-varying metamaterial, with the temporal boundary described by Eq. (11). The wavepacket electric induction can be synthesized via Fourier transform as

Then, for each value of the wavenumber k, we define the auxiliary functions

where

with initial conditions

where d

in(k, 0) is the plane wave spectrum of the incident electric induction field at t = 0. Next, we solve numerically Eq. (27) by means of the NDSolve routine available in Mathematica™ [52]. This routine provides the numerical solution of generic systems of ordinary differential equations, via a broad arsenal of methods (including Runge–Kutta, predictor-corrector, implicit backward differentiation) that can be tailored adaptively to the specific scenario of interest and, in principle, it can automatically handle discontinuities in the equations [52]. In our implementation, we utilize default settings and parameters. Moreover, in order to favor numerical convergence, we implement the abrupt permittivity changes via an analytical, smooth unit-step function

Once a numerical solution is available for Eq. (27), the electric induction is synthesized via Eq. (25) (where d = D

0

u

1), whereas the corresponding electric field can be readily obtained via division by

Funding source: University of l'Aquila

Funding source: The University of Sannio via the FRA 2020 program

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: C.R. acknowledges partial support by the University of l'Aquila. G.C. and V.G. acknowledge partial support by the University of Sannio via the FRA 2020 program.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] L. D. Landau, J. S. Bell, J. Kearsley, L. P. Pitaevskii, E. M. Lifshitz, and J. B. Sykes, Electrodynamics of Continuous Media, Vol. 8 of Course of Theoretical Physics, Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1984.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] V. M. Agranovich and V. Ginzburg, Crystal Optics with Spatial Dispersion, and Excitons, Vol. 42 of Springer Series in Solid-State Sciences, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] J. Elser, V. A. Podolskiy, I. Salakhutdinov, and I. Avrutsky, “Nonlocal effects in effective-medium response of nanolayered metamaterials,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 90, no. 19, p. 191109, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2737935.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] M. G. Silveirinha, “Time domain homogenization of metamaterials,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 83, no. 16, p. 165104, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.83.165104.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] A. V. Chebykin, A. A. Orlov, C. R. Simovski, Y. S. Kivshar, and P. A. Belov, “Nonlocal effective parameters of multilayered metal-dielectric metamaterials,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 86, no. 11, p. 115420, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.86.115420.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] A. Ciattoni and C. Rizza, “Nonlocal homogenization theory in metamaterials: effective electromagnetic spatial dispersion and artificial chirality,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 91, no. 18, p. 184207, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.91.184207.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] A. Demetriadou and J. B. Pendry, “Taming spatial dispersion in wire metamaterial,” J. Phys. Condens. Matter, vol. 20, no. 29, p. 295222, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/20/29/295222.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] A. Alù, “First-principles homogenization theory for periodic metamaterials,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 84, no. 7, p. 075153, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.84.075153.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] G. A. Wurtz, R. Pollard, W. Hendren, et al.., “Designed ultrafast optical nonlinearity in a plasmonic nanorod metamaterial enhanced by nonlocality,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 6, pp. 107–111, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2010.278.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] G. Castaldi, V. Galdi, A. Alù, and N. Engheta, “Nonlocal transformation optics,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 108, no. 6, p. 063902, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.063902.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] M. Moccia, G. Castaldi, V. Galdi, A. Alù, and N. Engheta, “Dispersion engineering via nonlocal transformation optics,” Optica, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 179–188, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.3.000179.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] A. Silva, F. Monticone, G. Castaldi, V. Galdi, A. A. Alù, and N. Engheta, “Performing mathematical operations with metamaterials,” Science, vol. 343, no. 6167, pp. 160–163, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1242818.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] A. M. Shaltout, K. G. Lagoudakis, J. van de Groep, et al.., “Spatiotemporal light control with frequency-gradient metasurfaces,” Science, vol. 365, no. 6451, pp. 374–377, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2357.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] C. Caloz and Z. Deck-Léger, “Spacetime metamaterials-part I: general concepts,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 1569–1582, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2019.2944225.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] C. Caloz and Z. Deck-Léger, “Spacetime metamaterials-part II: theory and applications,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 1583–1598, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2019.2944216.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] N. Engheta, “Metamaterials with high degrees of freedom: space, time, and more,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 639–642, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110710687-051.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] F. R. Morgenthaler, “Velocity modulation of electromagnetic waves,” IRE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 167–172, 1958. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmtt.1958.1124533.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] A. A. Oliner and A. Hessel, “Wave propagation in a medium with a progressive sinusoidal disturbance,” IRE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 337–343, 1961. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmtt.1961.1125340.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] R. Fante, “Transmission of electromagnetic waves into time-varying media,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 417–424, 1971. https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.1971.1139931.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Y. Hadad, D. L. Sounas, and A. Alù, “Space-time gradient metasurfaces,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 92, no. 10, p. 100304, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.92.100304.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] A. Shaltout, A. V. Kildishev, and V. M. Shalaev, “Time-varying metasurfaces and Lorentz non-reciprocity,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 2459–2467, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.5.002459.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] V. Bacot, M. Labousse, A. Eddi, M. Fink, and E. Fort, “Time reversal and holography with spacetime transformations,” Nat. Phys., vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 972–977, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3810.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] A. Shlivinski and Y. Hadad, “Beyond the Bode-Fano bound: wideband impedance matching for short pulses using temporal switching of transmission-line parameters,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 121, no. 20, p. 204301, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.121.204301.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] P. A. Huidobro, E. Galiffi, S. Guenneau, R. V. Craster, and J. B. Pendry, “Fresnel drag in space-time-modulated metamaterials,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 116, no. 50, pp. 24943–24948, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915027116.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] E. Galiffi, P. A. Huidobro, and J. B. Pendry, “Broadband nonreciprocal amplification in luminal metamaterials,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 123, no. 20, p. 206101, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.123.206101.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] H. Li, A. Mekawy, and A. Alù, “Beyond Chu’s limit with Floquet impedance matching,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 123, no. 16, p. 164102, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.123.164102.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] D. Ramaccia, D. L. Sounas, A. Alù, A. Toscano, and F. Bilotti, “Phase-induced frequency conversion and Doppler effect with time-modulated metasurfaces,” IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag., vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 1607–1617, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/tap.2019.2952469.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] E. Galiffi, Y.-T. Wang, Z. Lim, J. B. Pendry, A. Alù, and P. A. Huidobro, “Wood anomalies and surface-wave excitation with a time grating,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 125, no. 12, p. 127403, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.125.127403.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] H. Barati Sedeh, M. M. Salary, and H. Mosallaei, “Time-varying optical vortices enabled by time-modulated metasurfaces,” Nanophotonics, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 2957–2976, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0202.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] V. Pacheco-Peña and N. Engheta, “Effective medium concept in temporal metamaterials,” Nanophotonics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 379–391, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2019-0305.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] D. Torrent, “Strong spatial dispersion in time-modulated dielectric media,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 102, no. 21, p. 3214202, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.102.214202.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] V. Pacheco-Peña and N. Engheta, “Temporal aiming,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 9, p. 129, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-00360-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] V. Pacheco-Peña and N. Engheta, “Antireflection temporal coatings,” Optica, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 323–331, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.381175.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] H. Li and A. Alù, “Temporal switching to extend the bandwidth of thin absorbers,” Optica, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 24–29, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.408399.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] D. Ramaccia, A. Alù, A. Toscano, and F. Bilotti, “Temporal multilayer structures for designing higher-order transfer functions using time-varying metamaterials,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 118, no. 10, p. 101901, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0042567.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] G. Castaldi, V. Pacheco-Peña, M. Moccia, N. Engheta, and V. Galdi, “Exploiting space-time duality in the synthesis of impedance transformers via temporal metamaterials,” Nanophotonics, vol. 10, no. 14, pp. 3687–3699, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2021-0231.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] P. A. Huidobro, M. G. Silveirinha, E. Galiffi, and J. B. Pendry, “Homogenization theory of space-time metamaterials,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 014044, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.16.014044.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] R. Sabri, M. M. Salary, and H. Mosallaei, “Broadband continuous beam-steering with time-modulated metasurfaces in the near-infrared spectral regime,” APL Photonics, vol. 6, p. 086109, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0051815.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] D. M. Solís and N. Engheta, “Functional analysis of the polarization response in linear time-varying media: a generalization of the Kramers–Kronig relations,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 103, no. 14, p. 144303, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.103.144303.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] H. Herzig Sheinfux, I. Kaminer, Y. Plotnik, G. Bartal, and M. Segev, “Subwavelength multilayer dielectrics: ultrasensitive transmission and breakdown of effective-medium theory,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 113, no. 24, p. 243901, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.113.243901.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] G. Castaldi, A. Alù, and V. Galdi, “Boundary effects of weak nonlocality in multilayered dielectric metamaterials,” Phys. Rev. Appl., vol. 10, no. 3, p. 034060, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevapplied.10.034060.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] M. A. Gorlach and M. Lapine, “Boundary conditions for the effective-medium description of subwavelength multilayered structures,” Phys. Rev. B, vol. 101, no. 7, p. 075127, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.101.075127.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Y. Xiao, D. N. Maywar, and G. P. Agrawal, “Reflection and transmission of electromagnetic waves at a temporal boundary,” Opt. Lett., vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 574–577, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.39.000574.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] J. C. G. Henriques, T. G. Rappoport, Y. V. Bludov, M. I. Vasilevskiy, and N. M. R. Peres, “Topological photonic Tamm states and the Su–Schrieffer–Heeger model,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 101, p. 043811, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.101.043811.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] A. Kord, M. Tymchenko, D. L. Sounas, H. Krishnaswamy, and A. Alù, “CMOS integrated magnetless circulators based on spatiotemporal modulation angular-momentum biasing,” IEEE Trans. Microw. Theor. Tech., vol. 67, no. 7, pp. 2649–2662, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmtt.2019.2915074.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] N. Kamaraju, A. Rubano, L. Jian, et al.., “Subcycle control of terahertz waveform polarization using all-optically induced transient metamaterials,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 3, p. e155, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1038/lsa.2014.36.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] S. F. Preble, Q. Xu, and M. Lipson, “Changing the colour of light in a silicon resonator,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 293–296, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2007.72.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] E. Lustig, Y. Sharabi, and M. Segev, “Topological aspects of photonic time crystals,” Optica, vol. 5, no. 11, pp. 1390–1395, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.5.001390.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] J. Ma and Z.-G. Wang, “Band structure and topological phase transition of photonic time crystals,” Opt. Express, vol. 27, no. 9, pp. 12914–12922, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.012914.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] A. N. Serdyukov, I. V. Semchenko, S. A. Tretyakov, and A. Sihvola, Electromagnetics of Bi-anisotropic Materials: Theory and Applications, Amsterdam, Gordon & Breach, 2001.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] J. R. Zurita-Sanchez, P. Halevi, and J. C. Cervantes-Gonzalez, “Reflection and transmission of a wave incident on a slab with a time-periodic dielectric function ϵ(t),” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 79, no. 5, p. 053821, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.79.053821.Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Wolfram Research, Inc., Mathematica, Version 12.3.1, Champaign, IL, 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Carlo Rizza et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Gaptronics: multilevel photonics applications spanning zero-nanometer limits

- Ultrafast photonics applications of emerging 2D-Xenes beyond graphene

- Research Articles

- Nonlocal effects in temporal metamaterials

- Pattern-tunable synthetic gauge fields in topological photonic graphene

- Generalized temporal transfer matrix method: a systematic approach to solving electromagnetic wave scattering in temporally stratified structures

- Femtosecond imaging of spatial deformation of surface plasmon polariton wave packet during resonant interaction with nanocavity

- Probing the long-lived photo-generated charge carriers in transition metal dichalcogenides by time-resolved microwave photoconductivity

- Second-order topological phases in C 4v -symmetric photonic crystals beyond the two-dimensional Su-Schrieffer–Heeger model

- Full-visible-spectrum perovskite quantum dots by anion exchange resin assisted synthesis

- Multidimensional engineered metasurface for ultrafast terahertz switching at frequency-agile channels

- High efficiency and large optical anisotropy in the high-order nonlinear processes of 2D perovskite nanosheets

- Dynamic millimeter-wave OAM beam generation through programmable metasurface

- Intelligent metasurface with frequency recognition for adaptive manipulation of electromagnetic wave

- Singularities splitting phenomenon for the superposition of hybrid orders structured lights and the corresponding interference discrimination method

- Inverse-designed waveguide-based biosensor for high-sensitivity, single-frequency detection of biomolecules

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Gaptronics: multilevel photonics applications spanning zero-nanometer limits

- Ultrafast photonics applications of emerging 2D-Xenes beyond graphene

- Research Articles

- Nonlocal effects in temporal metamaterials

- Pattern-tunable synthetic gauge fields in topological photonic graphene

- Generalized temporal transfer matrix method: a systematic approach to solving electromagnetic wave scattering in temporally stratified structures

- Femtosecond imaging of spatial deformation of surface plasmon polariton wave packet during resonant interaction with nanocavity

- Probing the long-lived photo-generated charge carriers in transition metal dichalcogenides by time-resolved microwave photoconductivity

- Second-order topological phases in C 4v -symmetric photonic crystals beyond the two-dimensional Su-Schrieffer–Heeger model

- Full-visible-spectrum perovskite quantum dots by anion exchange resin assisted synthesis

- Multidimensional engineered metasurface for ultrafast terahertz switching at frequency-agile channels

- High efficiency and large optical anisotropy in the high-order nonlinear processes of 2D perovskite nanosheets

- Dynamic millimeter-wave OAM beam generation through programmable metasurface

- Intelligent metasurface with frequency recognition for adaptive manipulation of electromagnetic wave

- Singularities splitting phenomenon for the superposition of hybrid orders structured lights and the corresponding interference discrimination method

- Inverse-designed waveguide-based biosensor for high-sensitivity, single-frequency detection of biomolecules