Ultrafast photonics applications of emerging 2D-Xenes beyond graphene

-

Huanian Zhang

, Shuo Sun

, Xiaohui Li

, Hans Ågren

Abstract

Driven by new two-dimensional materials, great changes and progress have taken place in the field of ultrafast photonics in recent years. Among them, the emerging single element two-dimensional materials (Xenes) have also received much attention due to their special physical and photoelectric properties including tunable broadband nonlinear saturable absorption, ultrafast carrier recovery rate, and ultrashort recovery time. In this review, the preparation methods of Xenes and various integration strategies are detailedly introduced at first. Then, we summarize the outcomes achieved by Xenes-based (beyond graphene) fiber lasers and make classifications based on the characteristics of output pulses according to the materials characterization and nonlinear optical absorption properties. Finally, an outlook of the future opportunities and challenges of ultrafast photonics devices based on Xenes and other 2D materials are highlighted, and we hope this review will promote their extensive applications in ultrafast photonics technology.

1 Introduction

Since the first demonstration of laser in 1960, ultrashort pulse lasers attracted much attention and promoted the progress of the fields like modem iatrology, biology, chemistry, material processing, and military [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. Especially, inspired by the invention of Ti-sapphire mode-locked lasers, ultrafast lasers provide a steady and reliable optical source for numerous basic and foreword scientific research [6]. In recent decades, benefiting from the advantages of excellent beam quality, high conversion efficiency, compact structure, free alignment, excellent heat dissipation and environmental robustness, ultrafast fiber lasers have been fundamental tools in the fields of advanced materials processing, medical diagnosis and treatment, optical communication, laser radar, nonlinear microscopy and so on [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Mode-locked technique is the basic method to generate ultrashort picosecond (ps) or femtosecond (fs) pulses. Compared with actively mode-locked fiber lasers based on electro-optic modulator (EOM) or acousto-optic modulator (AOM), passively mode-locked fiber lasers get more attention due to the advantages of environmental stability, compact structure, easy integration, low cost, and high efficiency [13], [14], [15]. Saturable absorber (SA) devices are the kernel of passively mode-locked technique, which can be divided into artificial SAs and real SAs [16], [17], [18], [19], [20]. Artificial SAs can realize the nonlinear absorption related to the intensity of incident light based on birefringent properties, dependent rotation of an elliptical polarized light or nonlinear refractive index, such as Kerr lens (more often used in free-beam systems), nonlinear polarization rotation (NPR), and nonlinear amplifying loop mirror (NALM) [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. However, enslaved to poor environmental stability, low output power and difficult to self-start, NPR, and NALM without using polarization maintaining fiber have not gotten wide applications. And those NPR and NALM-based lasers with special cavity structure (such as Figures 8 and 9 cavity) and polarization maintaining fiber will inevitably increase the cost, volume and structural complexity. Semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors (SESAMs) are the typical representatives of real SAs and have been used in commercial mode-locked fiber lasers. Nonetheless, the complex fabrication and encapsulation process, cumbersome alignment and high cost greatly cut down the advantages of all-fiber format.

Nanotechnology and materials science are innovating constantly along with the development of laser technology; advances in nanoscale materials manufacturing technology exploit novel possibilities in the fabrication of new materials. In recent decade, low dimensional materials, as another type of real SAs with intense nonlinear saturable absorption effect, ultrafast carrier recovery time, and simpleness of preparation and integration to fiber systems, have opened up a new way for the design of photonic devices, such as 0-dimensional (0D) quantum dots (QDs), and 1D carbon nanotubes (CNT) a lot of researches have been reported [26–33]. In addition to these, although the researches of 2D layered materials have lasted for over 150 years, the enormous research interest really picked up was in 2004 that single-atom-thick graphene was first exfoliated from graphite by Novoselov et al. [34], [35], [36]. Since then, due to the abundant fascinating electrical, optical, and chemical characteristics like atomic layer thickness, high-carrier mobility, high optical absorption coefficient and strong light-material interaction, plenty of researches about photonic applications based on graphene and other 2D materials have been reported [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]. Among these 2D materials, graphene is the pioneer in applications of ultrafast photonics devices. However, the zero-bandgap structure limits its applications in situations required strong light–matter interaction [47]. Black phosphorus (BP) considered to be an ideal SA with high charge carrier mobility, tunable bandgap value of 0.3–2 eV and unique in-plane anisotropic structure [48]. The bandgaps of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) can cover the energy range from 0.86–2.5 eV, corresponding to the spectral range from visible to near-infrared [49], [50], [51]. Such as, the bandgaps of three well-known TMDs, which include MoS2, WS2, and SnS2, are 1.29, 1.35 and 2.24 eV for bulk structures, 1.9, 1.3 and 1.57 eV for monolayer [52], [53], [54]. However, the electronic and optical characteristics of TMDs highly depend on the number of layers, which limits the practical applications for photonic devices. Topological insulators (TIs) have a bandgap of 0.2–0.3 eV, can realize the output wavelength less than 4.2 μm [55, 56]. And the nonlinearity of TIs is better than graphene. But the slower relaxation time, complex preparation process and low damage threshold limit their development. Perovskites are novel materials for nonlinear optical research, but the existence of Pb element is harmful to our health. As a new member of 2D materials family, the nonlinear refractive index of transition-metal carbides and/or nitrides (MXenes) is about 10−4 cm2/W, which is larger than that of graphene of 10−5 cm2/W. But the preparation of MXenes is mainly by selective acid etching of the raw MAX phase, which is complex and high cost [57]. In addition to the 2D materials mentioned above, there are some emerging 2D materials attracting considerable attention due to their differentiation advantages, for example, ferromagnetic insulator (Cr2Si2Te6, Cr2Ge2Te6), yttrium oxide (Y2O3) [58], [59], [60], and even some saturable absorbers with special structures based on fiber [61].

In recent years, composed with single element, an emerging subclass of 2D materials called 2D mono-elemental graphene-like materials (Xenes) have attracted intense interest [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69]. Xenes refer to the mono-elemental 2D materials with atomic thickness, X stands for the possible group elements from IIIA to VIA, and “ene” is a Latin word that denotes nanosheets [70]. Profiting from their outstanding characteristics of tunable bandgap, ultrahigh surface-volume ratio, folded structure, and high carrier mobility, Xenes have raised great interest in various fields. Particularly, Xenes from group IV to VI like silicene, germanene, stanene, phosphorene, arsenene, antimonene, bismuthene, selenene, and tellurene have been proven to have some differences from the other 2D materials [71], [72], [73], [74]. Figure 1 illustrates the most stable atomic structures and of various main group Xenes materials and a timeline of experimental realization of several recent elemental 2D materials after the isolation of graphene. By changing the number of layers, the bandgap of Xenes can be designed flexibly which is beneficial to optical sensing [75], [76], [77]. In the field of biomedicine, the properties of excellent biodegradability and ultrahigh surface-volume ratio make Xenes a good choice [78], [79], [80], [81]. Benefit from the in-plane anisotropy resulted in the fold structure, Xenes open a new door for the neural networks [82, 83]. Besides, the high mechanical strength is meaningful for the improvement of battery safety, the fold structure and ultrahigh surface-volume ratio are of great significance to improve the battery capacity [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89]. Xenes have shown great potential and have huge application prospect in addressing challenges in the fields of energy, environment, and healthcare.

The most stable atomic structures of various main group mono-elemental 2D materials.

Compared to other 2D materials, Xenes exhibit outstanding nonlinear absorption properties, excellent photoelectric response, high nonlinear coefficient, and strong anisotropy [90], [91], [92], [93]. Tunable layer-dependent bandgaps determine the possibility of 2D Xenes can realize the broadband absorption from ultraviolet to near-infrared and even mid-infrared, and fill the gap between zero-bandgap graphene and other large-bandgap 2D materials [57]. Similar to graphene, 2D Xenes have high Fermi velocity, linear dispersion electronic characteristics, strong spin-obit coupling, and open bandgap at the Dirac point [79]. Besides, by adjusting the substrate interaction and interlayer twisting, the properties of photoelectricity can be turned flexibly [94]. Based on the above characteristics, Xenes may have the potential to realize some breakthroughs in the applications of optoelectronics and photonics that other 2D materials can not get.

Over the past few years, Xenes have been successfully demonstrated in designing ultrafast photonics devices. There have been many reviews of graphene as saturable absorber, such as, ultrafast lasers mode-locked by nanotubes and graphene [95], graphene-based saturable absorber for pulsed fiber laser generation [96], graphene saturable absorbers applications in fiber lasers [97], so our review does not summarize the works on graphene saturable absorbers. In this paper, we review the development of 2D Xenes based ultrafast applications. Catalog the preparation methods of Xenes and various integration strategies are detailedly introduced at first. Then, according to the materials characterization and nonlinear optical absorption properties we summarize the outcomes achieved by Xenes-based lasers and make classifications based on the characteristics of output pulses. At last, an outlook of the future opportunities and challenges of ultrafast photonic devices based on Xenes and other 2D materials are highlighted.

2 Fabrication and characterization of 2D materials

2.1 Fabrication techniques

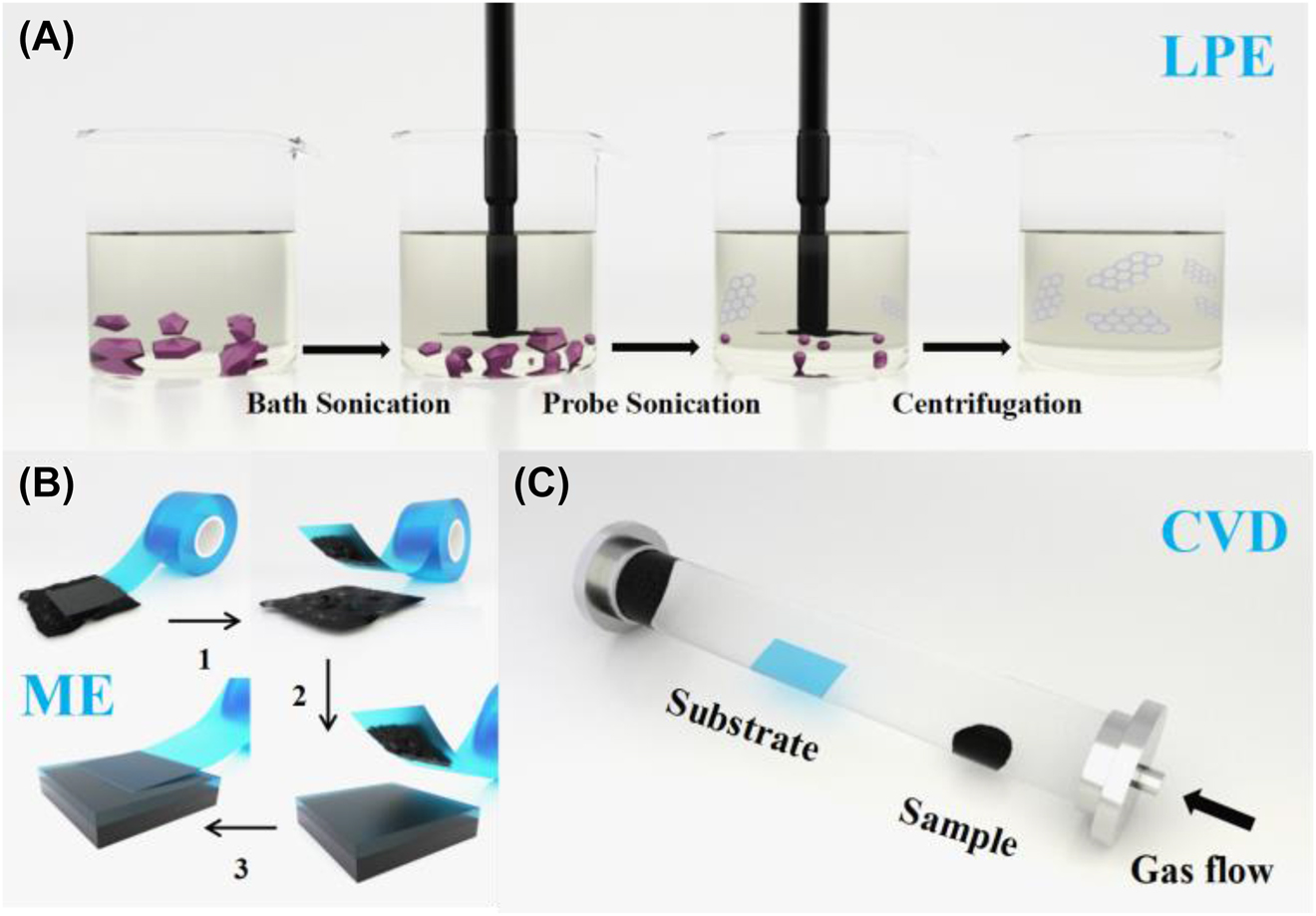

Few-layer nanomaterials fabrication methods broadly include two directions: bottom-up of molecular precursors and top-down of bulk layered materials. Bottom–up growth methods refer to the film of molecules arranged in a single or several layers, such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and pulsed laser deposition (PLD). Top–down exfoliation methods (including mechanical cleavage and solution processing techniques) depend on the weak van der Waals interaction of layered nanomaterials, which makes it easy to strip nanosheets from large bulk layered materials. Figure 2 shows three mainly fabrication techniques of 2D materials.

Schematic of fabrication techniques of 2D materials.

(A) LPE method. (B) Mechanical exfoliation (ME) method. (C) CVD method.

CVD is a method of 2D nanomaterials growth by injecting precursor gas into the chamber with the heated substrate and making a chemical reaction on the heated substrate surface, a thin film is deposited from the steam in the end. The properties of the prepared material are affected by substrate material, substrate temperature, pressure, and gas flow. The characteristics of CVD technology are products of uniform thickness and low porosity even on substrates of complex shapes, and a wide variety of deposited materials. In addition, the use of distillation technology contributes to the purity of nanomaterials deposition very high. Micromechanical exfoliation method by using mechanical force to two-dimensional nanomaterial to stripped layered 2D material from bulk layered materials. For example, graphene was separated from graphite by the adhesive force of tape. Electrochemical exfoliation is a way of using electrical current as a driving force to carry foreign molecules or ions into a bulk layered material in the electrochemical cell, which will increase the interlayer distance and make 2D materials easier to strip. Liquid-phase exfoliation (LPE) method has been a general technology for preparing layered nanosheets from 2D materials, including graphene, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), ferromagnetic insulators (FIs), transition metal oxides (TMOs), 2D mono-elemental graphene-like (Xenes). LPE refers to suspending layered crystals in a “solvent” and impacting the crystals with ultrasonic energy to break them into 2D layered materials. The general process of preparing 2D material nanosheets by LPE method involves following several steps: first, dispersion of the 2D material power in a liquid medium, then, the suspensions are employed sonication to assist the dispersal of nanosheets, last, centrifugation to remove the precipitation to get stable suspensions. The LPE method is an effective method for the preparation of large scale, highly concentrated atomically thin 2D nanosheets with the advantages of high quality and easy preparation. Saturable absorbers fabricated by ME, LPE, CVD, pulsed laser deposition (PLD), and magnetron sputtering deposition (MSD) are more convenient, easier and lower cost. ME and LPE belong to the top-down methods, they are the simplest methods to get nanosheets. Because of that polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA) have low melting point, SAs fabricated by LPE with PVA or PMMA are usually stable under different environment and high thermal. However, the number of layers obtained by these two methods is random and uncontrollable. In contrast, the layer number of nanosheets prepared by the bottom-up methods (CVD, PLD, MSD) is controllable, especially the CVD method. Besides, the MSD method has been widely used in the fabrication of SA based on tapered fiber and D-shaped fiber. Finally, we note that there are other few layer 2D materials fabrication techniques were adopted to produce SA devices, such as sonochemical exfoliation, physical vapor deposition, and gas phase growth.

2.2 Characterization of Xenes materials

In the experiment, characterization methods, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), Raman, X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), and atomic force microscopy (AFM), were usually employed to test the surface and physical properties of 2D materials to better understand its nonlinear optical absorption properties.

The SEM is adopted for testing the surface morphology of the 2D materials. The layered structure can be seen if the materials are successfully fabricated. The thickness of nanomaterials can be calculated by AFM, we can estimate the number of layers further. The EDS spectra can provide the atomic ratio of materials. Raman and XRD spectra are used to detect the element composition and crystal structure. Additionally, to test the structure characteristics, TEM and HR-TEM are employed. For example, Figure 3 illustrates the characterization methods for tellurene. Obvious layered structure can be seen according to Figure 3A and B, Raman and XRD spectra also corresponds very well. Lattice fringes of tellurene are existed by HR-TEM image. All results indicate that pure tellurene nanosheets with a well layered-structure and high-crystallinity are prepared successfully.

![Figure 3:

Characterization methods for tellurene.

(A and B) SEM image, inset: EDS spectra. (C) Raman spectra. (D and E) AFM image. (F) XRD spectra. (G) TEM image. (H and I) HR-TEM image. Reproduced with permission [98].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_003.jpg)

Characterization methods for tellurene.

(A and B) SEM image, inset: EDS spectra. (C) Raman spectra. (D and E) AFM image. (F) XRD spectra. (G) TEM image. (H and I) HR-TEM image. Reproduced with permission [98].

3 Nonlinear optical properties of 2D materials

In generally, the optical response of materials can be expressed by the refractive index as

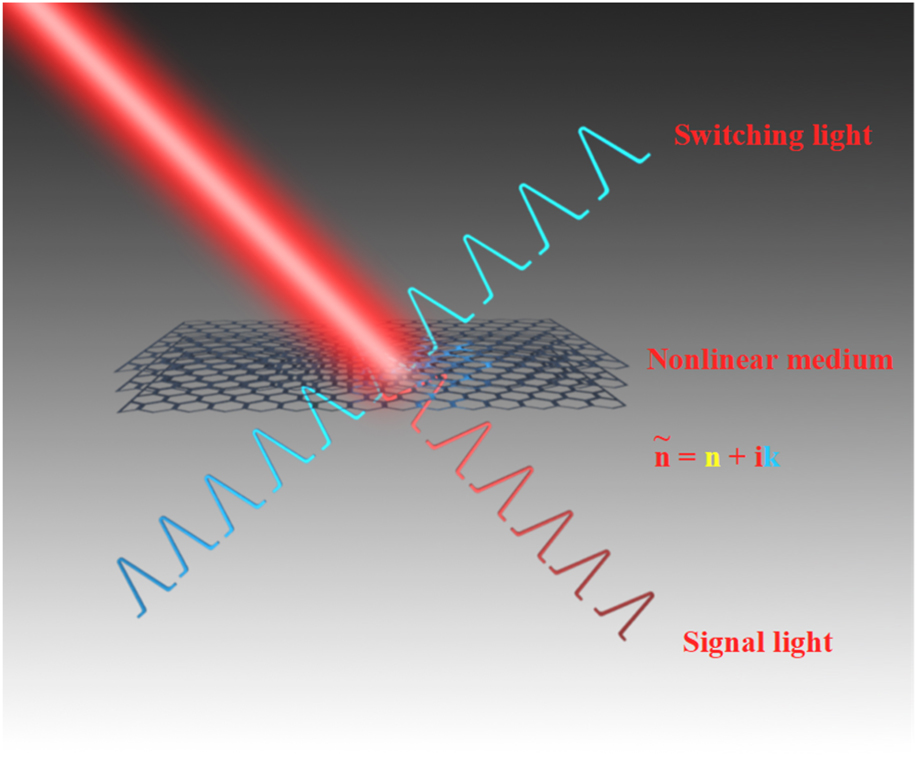

Schematic diagram of all-optical modulation. Switching light beam control and modulate the signal light. The light–light interaction is achieved by nonlinear medium, and the kernel of the all-optical modulation is to control or modulate the real or imaginary parts of the refractive index of the nonlinear medium.

3.1 Optical Kerr effect

The optical Kerr effect is a third-order nonlinear phenomenon, which is manifested in the change of instantaneous refractive index of nonlinear medium caused by the incident light, which increases with the increase of incident light intensity. It can be expressed as:

Where

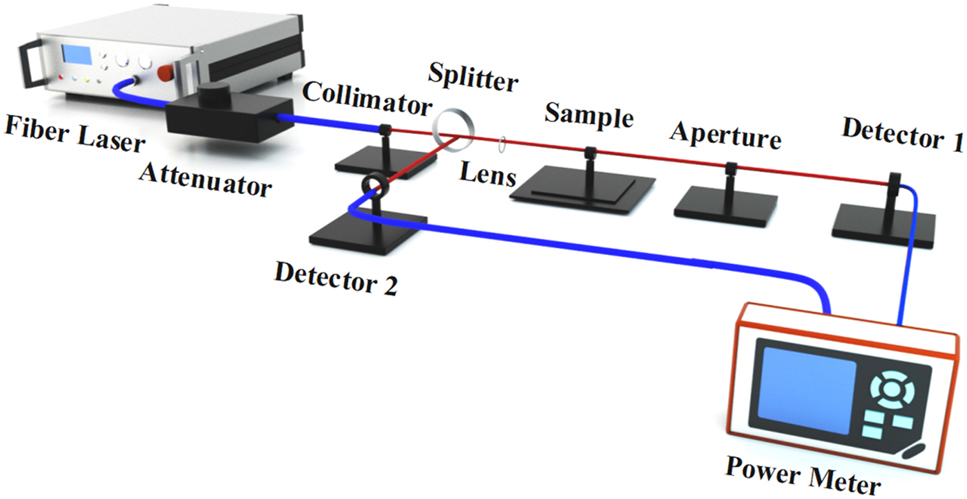

Typical Z-scan measurement by using ultrashort pulses is an important means to detect the nonlinear absorption characteristics of 2D mono-elemental graphene-like (Xenes) materials. The thin medium with negative nonlinear coefficient can be regarded as a thin lens with variable focal length when a Gaussian beam is incident, and the focus of the lens is taken as the origin of the Z-axis. When the nonlinear medium moves from – Z to the origin, the initial light intensity is low, and the light refraction caused by nonlinearity can be ignored. Therefore, the transmittance T measured at aperture A remains relatively unchanged, which the linear transmittance is unchanged of the system. When the sample is scanned near the origin, the light refraction effect caused by nonlinearity significantly strengthened due to the increase of light intensity. At this time, the sample is equivalent to a negative lens to collimate the beam, narrowing the beam at aperture A, resulting in an increase in the measured transmittance. Therefore, at the side of Z < 0 close to Z = 0, the T–z curve shows a peak. When the nonlinear medium moves past the origin 0, the self defocusing effect of the sample will widen the beam at aperture A and reduce the transmittance. Similarly, the self defocusing effect is most obvious near z = 0, resulting in a valley in the T–z curve; At the origin, the far-field transmittance is the same as the linear value. From the above analysis, the Z-scan curve can be qualitatively obtained, which is in the shape of peak before valley.

For Z-scan measurement, as shown in Figure 5, at first, the two-dimensional materials were placed on the z-direction translation table, the light of the ultrashort pulse light source is divided into two parts. One path uses the low optical power measured by the slow detector as reference. Another path consists of high optical power part for materials characterization. Then, the light beam in the measurement part is focused on the 2D materials through the lens. The transmitted light passes through the two-dimensional materials and collected by the second detector. By comparing the readings of the two detectors, the strength dependent transmission characteristic of two-dimensional materials can be obtained. The Z-scan curve can be fitted with the following formula:

according to the Z-scan theory [99]. In which, Z is the position of the sample relative to the focus, Z 0 is the diffraction length of the beam, α 0 L is the modulation depth, T(z) is the normalized transmittance at Z, I 0 is the peak onaxis intensity at the focus, and Is the saturable intensity. However, the nonlinear absorption coefficient, which is significant to the description of nonlinear effects, is unknown only according to Eq. (2). So, another equation is needed to obtain the nonlinear absorption coefficient as following [100]:

where β and α 0 represent the nonlinear and linear absorption coefficient, respectively, and L eff is the effective length which can be expressed by the following formula [101]:

Schematic of Z-scan experimental setup.

The nonlinear optical properties of 2D Xenes materials measured by the Z-scan technology are summarized in Table 1. In 2018, Zhang et al. used Z-scan to explore the nonlinear absorption characteristics of silicene for the first time [103]. Under 532 nm excitation, silicon has low saturation intensity and large two-photon absorption coefficient. Experimental results show that silicon has potential application prospects in ultrafast lasers and optical limiting devices. The measurement of nonlinear optical properties is of great significance for the optical applications of 2D materials.

Summarization of nonlinear optical properties of 2D Xenes.

| 2D materials | Laser parameters | T(%) | I s (GW/cm2) | Imχ (3) (esu) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimonene | 1064 nm, 10 Hz, 40 ps | 18.4 | 1.3 | – | [102] |

| Silicene | 532 nm, 10 Hz, 30 ps | – | 6.9 | 3.7 × 10−5 | [103] |

| Bismuthene | 2 μm, 5 kHz, 70 ns | 15.4 | 183.9 kW/cm2 | – | [104] |

| Tellurene | 515 nm, 1 kHz, 350 fs | 3.2 | 11.2 | 2.383 × 10−22 | [105] |

| Tellurene | 1550 nm | 27 | 78.14 | – | [106] |

| BP | 800 nm, fs | 36 | 3.3 | – | [107] |

| BP | 1.5 μm, 20 kHz, 190 fs | 12.4 | 2.16 μJ/cm2 | – | [108] |

-

T: modulation depth; I s : saturation intensity; Imχ (3): third-order nonlinear susceptibility.

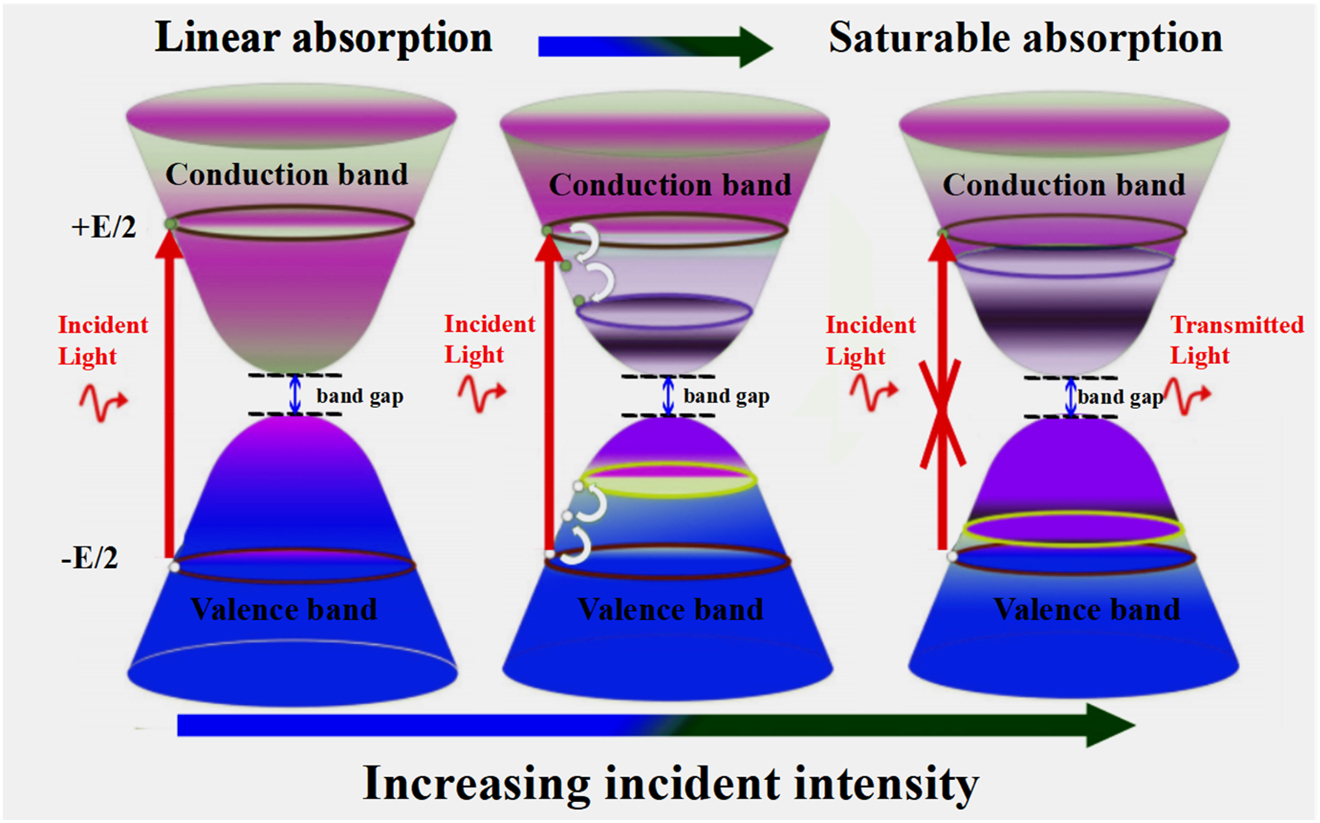

3.2 Saturable absorption properties

Dual arm detection system can measure the nonlinear absorption characteristics of the SA-based D-type fiber, tapered fiber, and SA in optical fiber devices. As shown in Figure 6A, the ultrashort pulse is divided into two paths through the output coupler with a coupling ratio of 50:50. One path reaches the power meter by connecting an optical fiber containing the SA. The other path is directly connected to the power meter. The obtained data are fitted by the following formula:

Where,

![Figure 6:

Nonlinear optical characterization: (A) Schematic of dual arm detection system. (B) Power-dependent nonlinear optical property of tellurenebased SA. (Inset) Corresponding experimental setup for testing nonlinear optical property. Reproduced with permission [98].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_006.jpg)

Nonlinear optical characterization: (A) Schematic of dual arm detection system. (B) Power-dependent nonlinear optical property of tellurenebased SA. (Inset) Corresponding experimental setup for testing nonlinear optical property. Reproduced with permission [98].

The saturable absorption property is the core mechanism of 2D materials used as ultrafast photonics devices in mode-locked or Q-switched lasers. Similar to other 2D materials, the process of saturable absorption of mono-elemental graphene-like (Xenes) can also be interpreted by the Pauli blocking principle, which is shown in Figure 7. Under normal conditions, most electrons are in the valence band, this balance will not be broken until the light is incident on the SA. Linear absorption will occur firstly if the intensity of incident light is low. When the incident light has larger energy than the bandgap value of the SA, electrons in the valence band will be excited into the conduction band by absorbing the energy of photons (the energy of one photon is

The process of linear absorption and saturable absorption of Xene due to Pauli blocking effect: (left) interband transition of the electron due to light excitation; (middle) hot carriers lend to thermal balance; (right) blocking of absorption for light.

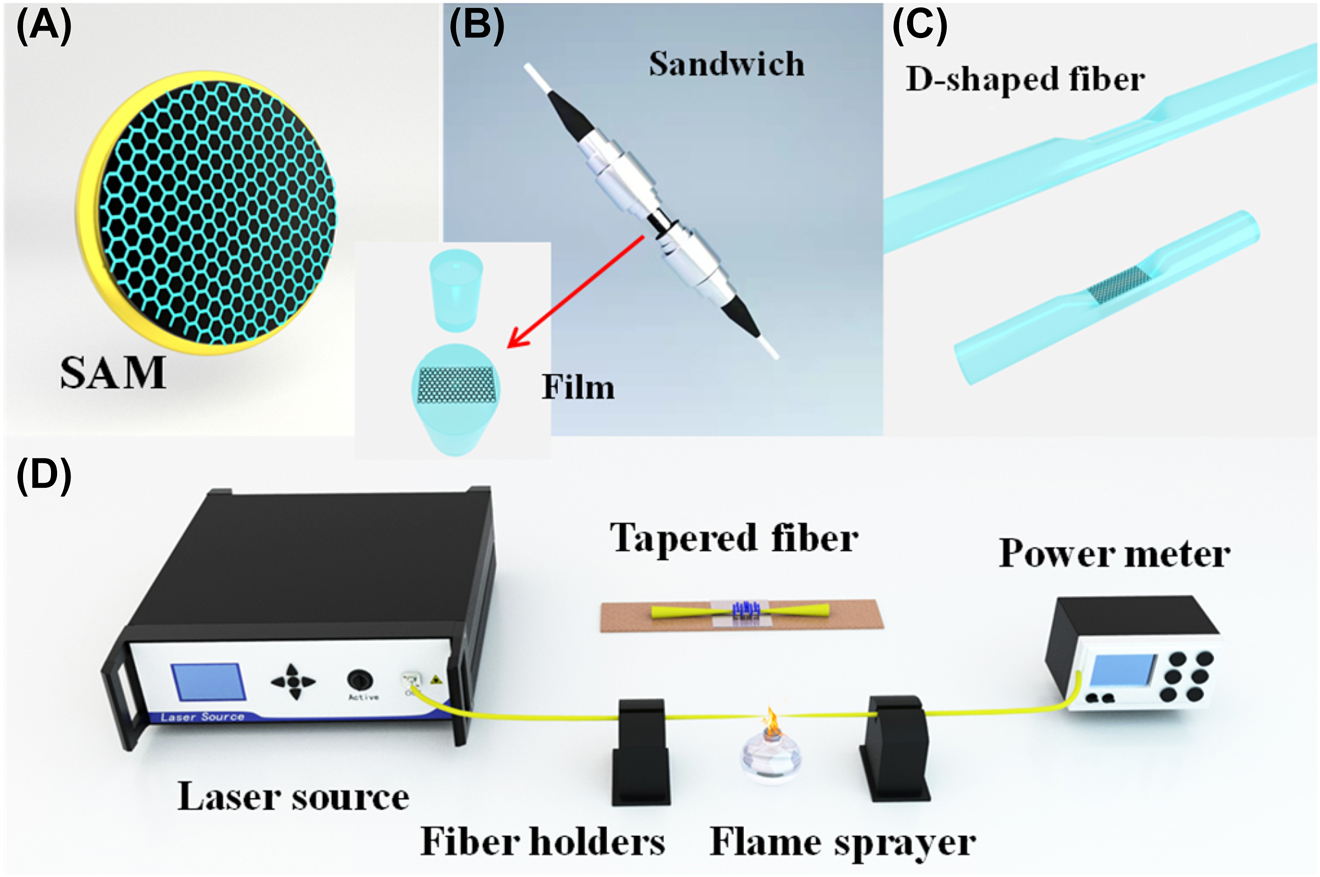

4 SA incorporation methods

The methods for preparing SA based on 2D materials mainly include SA mirror (SAM), deposited on the fiber endface, tapered fiber, D-shaped fiber, and polymer materials composite films. As show in Figure 8A, SAM is prepared by thin film of 2D material and transferring the film onto a mirror substrate. Such as semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors (SESAMs), single wall carbon nanotube SAM (SWCNT-SAM), graphene SAM. Semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors (SESAMs) are the typical representatives of real SAs and have been used in commercial mode-locked fiber lasers. Nonetheless, the complex fabrication and encapsulation process, cumbersome alignment and high cost greatly cut down the advantages of all-fiber format. 2D materials polymer materials composite thin film SA attached to the end face of the fiber connector shown in Figure 8B. Thin-film SA like 2D materials-PVA films are easy to transfer, but they can’t withstand high-power or long-time beam lighting. By depositing 2D-materials nanosheets on D-shaped or tapered fiber can improve this problem, and the intrinsic nonlinear effects can produce more abundant and interesting optical phenomena. It is more attractive that D-type optical fiber is used to prepare SA. D-type optical fiber has a larger fiber diameter and higher robustness due to it generally made by placing arc-shaped blocks on single-mode fiber and polishing it. D-type optical fiber with 2D materials deposited on its surface is shown in Figure 8C. D-shaped fiber SA is based on the evanescent field between the 2D materials and optical field, it has longer nonlinear optical interaction length and higher damage threshold than the 2D materials-film SA. Tapered fiber SA is also based on the evanescent field between the 2D materials and optical field. Figure 8D shows experimental setup of preparing the tapered fiber, tapered fiber is fabricated by standard single-mode fiber are stretched in a molten state heated by a flame. The diameter and length of the fiber are gradually reduced to a suitable range as the conical fiber is stretched. Both ends of the tapered fiber are coupled to a semiconductor laser and a power meter to measure the loss of the prepared tapered fiber. The inset of Figure 8D presents the SA by the tapered fiber deposited with 2D material. More abundant and interesting optical phenomena can be obtained due to the long nonlinear optical interaction length and higher damage threshold. But D-shaped or tapered fiber based SA will increase the difficulty of the preparation process and increase the cost. Another SA preparation method is that 2D material deposited on the fiber end face by laser radiant thermal deposition. The nonlinear response of the tapered fiber SA and D-type fiber SA is realized through the nonlinear interaction between the evanescent field on the fiber surface and the 2D material deposited in the tapered region. The nonlinear effect is depend on the interaction length and damage threshold between laser and layered materials deposited on the surface of tapered region, which is of great significance to the design of better ultrafast photonic devices. Compared with SESAMs, the other incorporation methods have their own different advantages and disadvantages. The application of SA material on special optical fibers has become a research hotspot.

Integration schemes to form nanomaterial-based photonic devices.

5 Demonstration of ultrafast lasers based on Xenes beyond graphene

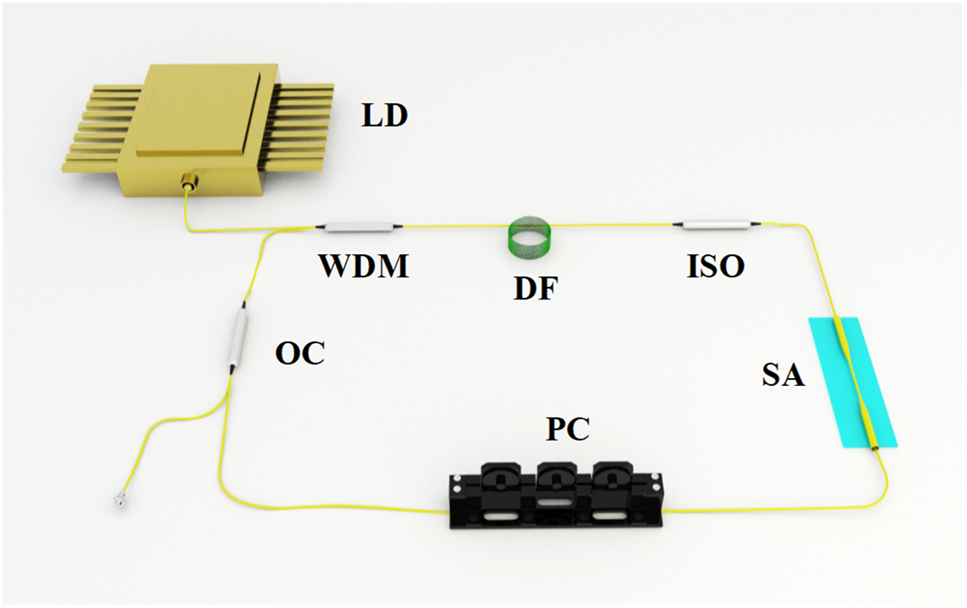

Figure 9 shows the typical ultrafast ring cavity fiber laser system based 2D Xenes as SA. A piece of gain fiber (GF) is pumped by the pump source which is a fiber-pigtailed laser diode (LD), the GF mainly include Yb-doped, Er-doped, Ho-doped and Tm-doped fibers. The operating wavelength of the laser can be changed from near-infrared band to mid-infrared band by selecting appropriate pump source and matching different GF. Besides, the polarization state and transmission direction of the laser in cavity are controlled by a polarization controller (PC) and a polarization-independent isolator (PI-ISO), respectively. Through an optical coupler with a certain output coupling ratio, the information of the output pulse can measured by a digital oscilloscope combined with a high-speed photodetector, an optical spectrum analyzer, a radio frequency (RF) spectrum analyzer, an optical power meter, and auto-correlator instrument, respectively. Up to now, various lasers have been developed by using the 2D Xenes materials as SAs. Then, we will briefly review these lasers as follows.

Typical ultrafast fiber laser system using 2D Xenes as SA.

5.1 Q-switched operation

Q-switched lasers have been widely applied in optical sensing, optical frequency metrology, laser marking, optical communications, and scientific research due to the advantages of robustness, high pulse energy, and excellent beam quality. The pulse energy of Q-switched laser can reach to μJ or mJ level with low repetition rate and narrow pulse width, which are generally kHz and ns level, respectively. In recent years, 2D Xenes nanomaterials beyond graphene based SAs have been widely used in passively Q-switched laser. As shown in Table 2, the performance of Q-switched lasers based on 2D Xenes materials is classified and summarized. Among them, the maximum pulse energy of 15.95 μJ and minimum pulse width of 48.33 ns were demonstrated [114, 125], respectively. As an example, Hu et al. achieved the stable Q-switched operation based on antimonene SA [111], the pulse repetition rate varies from 25.3 to 76.7 kHz when the pump power increased from 41 to 345 mW, the shortest pulse duration is 1.58 µs with pulse energy of 37.9 nJ, as shown in Figure 10. The Q-switched operating wavelength of 2D Xenes-based lasers cover from visible to mid-infrared. For example, Hai et al. demonstrated that topological semimetal antimonene possesses an ultrabroadband optical switch characteristic covering from 2 μm to beyond 10 μm, based on antimonene, passively Q-switched pulsed lasers at 2 and 3.5 μm wavelengths were realized [109]. In 2019, Zhang et al. designed a passively Q-switched Nd:LuAG laser with fluorinated antimonene, centered at 1064 nm with a pulse width of 326.7 ns and a repetition rate of 733.1 kHz demonstrating its potential application as SA [116]. In 1.3 μm, a passively Q-switched bulk laser with the maximum average output power of 125 mW and the shortest pulse width of 510 ns was demonstrated by Su et al. [119]. Recently, Han et al. Proved the visible nonlinear optical properties of tellurium and application as SA, they realized the passively Q-switched Pr: YLF laser over the spectrum of orange (605 nm), red (639 nm), deep red (721 nm) with tellurium film as SA [105]. In 2021, Hassan report on tellurium nanorods as SA induced four-wave-mixing to construct an all-fiber multi-wavelength passively Q-switched erbium-doped-fiber laser, simple and green chemical process were used to prepare 1D tellurium nanorods SA, experimental results show that the SA device simultaneously generates seven wavelengths within 1592.4–1599.6 nm waveband with mode spacing of 1.2 nm. There have been many reports on BP-based Q-switched lasers [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153], [154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], and representative fiber lasers are given in Table 2. These manifest 2D Xenes applicability as a versatile 2D broadband SA candidate.

Performance summary of Q-switched lasers based on 2D Xenes SAs.

| 2D materials | Fabrication method | Incorporation method | Modulation depth (%) | λ (nm) | Duration (µs) | RF (kHz) | Energy (µJ) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimonene | LPE | SAM | 18 | 2016 | 2–3.5 | – | 8.89 | [109] |

| 8 | 3466.6 | 3.9–3.7 | – | 0.22 | ||||

| Antimonene | LPE | SAM | 19.1 | 2865 | 1.74–4 | 59.52–156.2 | 0.72 | [110] |

| Antimonene | LPE | Film | 13.06 | 1559.63 | 1.58–9.23 | 25.3–76.7 | 37.9 nJ | [111] |

| Antimonene | Vapor deposition | D-shaped fiber | 7.1 | 1561.9 | 983 ns | 23.26 | – | [112] |

| 7.1 | 2789.5 | 824 ns | 201.5 | – | ||||

| Antimonene | LPE | Tapered fiber | – | 1557 | 1.31 | 20–50 | – | [113] |

| Antimonene | LPE | Quartz substrate | 3.5 | 946 | 208.8 ns | 268.3 | 0.31 | [114] |

| – | 1064 | 129 ns | 569.1 | 0.23 | ||||

| – | 1342 | 48.33 ns | 28.65 | 1.36 | ||||

| Antimonene | LPE | Film | 11.63 | 1558 | 1.42–5.1 | 25.6–124.1 | 54 nJ | [115] |

| Antimonene | LPE and synchronous fluorination | – | – | 1064 | 0.33–0.89 | 388.8–733.1 | – | [116] |

| Antimonene | PVD | Film | 22 | 1947 | 4.9–11.6 | 14.5–23.5 | 0.12 | [117] |

| Bismuthene (QDs) | LPE | Quartz substrate | 18.1 | 1060 | 0.15 | 424 | 0.26 | [118] |

| 5.1 | 1030 | 0.15 | 457 | 0.26 | ||||

| Bismuthene(QDs) | LPE | Quartz substrate | – | 2 µm | 0.44 | 94 | 4.5 | [116] |

| Bismuthene(QDs) | LPE | Sapphire substrate | 8.7 | 1341 | 0.51 | 63–135 | 0.91 | [119] |

| Silicene | LPE | Film | 20.1 | 1567.1 | 2.32–5.47 | 11.1–58.7 | – | [120] |

| Silicene | LPE | Quartz substrate | 18.9 | 946.6 | 0.2–0.4 | 166.6–294.5 | 0.55 | [103] |

| 17 | 1064.3 | 0.1–0.25 | 319.8–587 | 0.22 | ||||

| – | 1341.8 | 0.11–0.30 | 238.5–570 | 0.14 | ||||

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | 3.2 | 605 | 0.17 | 208 | 0.24 | [105] |

| – | 639 | 0.16 | 331 | 0.19 | ||||

| – | 721 | 0.12 | 214 | 0.25 | ||||

| Tellurene | Green chemical method | – | 4 | 1595 | 2.85 | 44 | 50 nJ | [121] |

| Tellurene | LPE | Sapphire substrate | 6.3 | 1064 | 0.1 | 535.8 | 0.26 | [122] |

| – | 1.3 µm | 0.18 | 257.1 | 0.44 | ||||

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | 12 | 1341.6 | 0.95 | 117 | 2.25 | [123] |

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | 0.97 | 1563.7 | 5.196–8.915 | 15.92–47.61 | – | [124] |

| Tellurene-BP | LPE | – | 13.6 | 1064.3 | 0.44 | 71 | 4.3 | [125] |

| 12.6 | 1954.4 | 0.45 | 65 | 15.95 | ||||

| 10.3 | 2790 | 0.26 | 90 | 13.89 | ||||

| BP | – | D-shaped fiber | – | 1550 | 9.35 | 4.43–18 | 28.3 nJ | [126] |

| BP | LPE | SAM | 15 | 2.8 µm | 1.18 | 39–63 | 7.7 | [127] |

| BP | ME | Film | 1.94 | – | 3.4 | 26–76 | – | [128] |

| BP | LPE | Optical deposition | 24 | 1912 | 0.73 | 69.4–113.3 | 0.63 | [129] |

| BP | LPE | Film | 14.3 | 1561.21–1564.16 | 2.98–25.10 | 10.348–30.098 | 0.28 | [130] |

| BP | LPE | Film | – | 635.4 | 0.38 | 108.8–409.8 | – | [131] |

| BP | LPE | Film | – | 1550 | 1.73–4.44 | 16.72–30.71 | 47.6 nJ | [132] |

| BP | LPE | Tapered fiber | 50.94 | 1563.1 | 91 ns–890.7 ns | 15.76–295.98 | 16.5–21.1 nJ | [133] |

| BP | ME | Film | 7 | 1550 | 7.04–20.75 | 9.1–44.33 | 0.13 | [134] |

| BP | ME | Fiber endface | 7 | 1069.4 | 12.2 | 26.1 | 0.33 | [135] |

-

λ: central wavelength; RF: repetition frequency; ME: mechanical exfoliation; LPE: liquid-phase exfoliation; PVD: physical vapor deposition; SAM: saturable absorber mirror.

![Figure 10:

Material characterization:

(A) TEM image. (B) HR-TEM image. Q-switching characteristics of an EDFL based on antimonene SA: (C) Pulse trains at different pump powers. (D) The optical spectrum. (E) output power and pulse energy versus the pump power. (F) Pulse duration and pulse repetition rate versus the pump power. Reproduced with permission [111].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_010.jpg)

Material characterization:

(A) TEM image. (B) HR-TEM image. Q-switching characteristics of an EDFL based on antimonene SA: (C) Pulse trains at different pump powers. (D) The optical spectrum. (E) output power and pulse energy versus the pump power. (F) Pulse duration and pulse repetition rate versus the pump power. Reproduced with permission [111].

5.2 Mode-locked operation

Different from Q-switched lasers, mode-locked lasers can realize the pulse duration in sub-ps level, in recent years, passively mode-locked lasers based on 2D Xenes attracted increasing interest in applications of advanced materials processing, medical diagnosis and treatment, military systems, and optical communication due to their giant superiority stemming from the merits of possessing higher peak power and shorter pulse duration.

Passively mode-locked operation based on 2D Xenes materials have been adopted to realize pulsed operation due to their more compact in geometry and simpler in setup [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169], [170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180], [181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191], [192], [193], [194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202], [203], [204], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212]. Passively mode-locked lasers as an effective tool to investigate soliton dynamics and the related nonlinear phenomenon have received intense attention in recent years. SAs were mainly used to achieve traditional soliton operations with ps or fs level pulse width and relatively low pulse energy limited by the soliton area theorem [98]. The pulse energy of the traditional soliton fiber laser is generally limited by optical wave breaking (the energy of pulses is limited to 0.1 nJ) [215, 216]. Generally, attaching the SA onto the facet of fiber connector is the main way to get ultrafast optical modulator, but it is easy to be damaged by the high energy density of ultrafast pulse. Fortunately, utilize evanescent field interaction between fiber and material provided an approach for solving this issue [218]. For instance, Guo et al. demonstrated a sub-200 fs soliton mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser (EDFL) using a microfiber-based bismuthene SA for the first time, as is illustrated in Figure 11, stable soliton pulses centered at 1561 nm with the shortest pulse duration of about 193 fs were obtained [166]. In 2017, Song et al. discovered the nonlinear optical properties of few-layer antimonene for the first time, through liquid-phase exfoliation and fabricate it as antimonene decorated microfiber with tapered fiber by using evanescent field optical deposition, mode-locked pulses centered at 1.55 µm had been obtained with a pulse width of ∼550 fs, obvious Kelly sideband was observed.

![Figure 11:

Material characterization:

(A) AFM image. (B) TEM image. (C) The nonlinear saturable absorption curve of the microfiber-based bismuthene device (Inset: its corresponding red light image). Mode-locked characteristics of an EDFL based on bismuthene SA: (D) output optical spectrum. (E) Its corresponding oscilloscope trace (inset: the autocorrelation trace). (F) The output power versus the pump power of the soliton pulse. Reproduced with permission [166].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_011.jpg)

Material characterization:

(A) AFM image. (B) TEM image. (C) The nonlinear saturable absorption curve of the microfiber-based bismuthene device (Inset: its corresponding red light image). Mode-locked characteristics of an EDFL based on bismuthene SA: (D) output optical spectrum. (E) Its corresponding oscilloscope trace (inset: the autocorrelation trace). (F) The output power versus the pump power of the soliton pulse. Reproduced with permission [166].

High energy optical pulse has attracted extensive attention because of its wide application in optical sensing, optical frequency measurement and data query. Among them, dissipative soliton (DSs) in passive mode-locked lasers have been widely developed in recent years, because they increase the pulse energy of lasers by several orders of magnitude compared with the traditional soliton pulse. It is found that in the normal dispersion state, the laser generates DSs is a balance of the self-phase modulation (SPM) cavity dispersion, Kerr nonlinearity, spectral filtering effect, and cavity loss [217]. Its dynamics is controlled by cubic-quintic GLE. So far, DSs has demonstrated the use of various schemes in lasers. A part of typical characteristics of dissipative soliton are shown in Figure 12. In 2020, based on tellurene as SA, Zhang et al. achieved large-energy mode-locked operations in an all fiber EDFL, both DSs and noise-like pulses were obtained, for dissipative soliton operation, the maximum average output power, pulse width, and largest pulse energy are 23.61 mW, 5.87 ps, and 1.94 nJ, respectively [98], the obtained results provide an enhanced understanding of dynamics of the dissipative soliton and noise-like pulses. Interestingly, thanks to the narrow bandgap of bismuthene and tapered fiber structure, a special kind of noise-like multipulses have been obtained in Yb-doped fiber laser by Feng et al. [165], the saturation intensity and modulation depth of bismuthene SA are about 2.4 MW/cm2 and 1%, respectively.

![Figure 12:

DS characteristics.

(A) Typical spectrum of the DSs with center wavelength of 1034.4 nm. (B) The spectral evolution versus the pump power. (C) The time delay evolution versus the pump power. (D) Autocorrelation trace. Reproduced with permission [164]. Output characteristics of tellurene-based SA mode-locked operation. (E) Emission optical spectrum. (F) Autocorrelation traces. Reproduced with permission [98].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_012.jpg)

DS characteristics.

(A) Typical spectrum of the DSs with center wavelength of 1034.4 nm. (B) The spectral evolution versus the pump power. (C) The time delay evolution versus the pump power. (D) Autocorrelation trace. Reproduced with permission [164]. Output characteristics of tellurene-based SA mode-locked operation. (E) Emission optical spectrum. (F) Autocorrelation traces. Reproduced with permission [98].

High-damage threshold SA provides the assistance for harmonic mode-locked laser since multiple pulses rearrange themselves in a regular position and the pulse repetition rate is the multiple of the fundamental repetition rate at the high pump regime. In 2017, Pawliszewska et al. reported a mode-locked in Ho-doped all-fiber laser based on BP SA at the central wavelength of 2094 nm [202], 10th harmonic (290 MHz) was obtained, and this is the first demonstration of mode-locked operation in a Ho-doped fiber laser with the a BP SA. In mid-infrared band, Liu et al. succeed in developing a chemically synthesized tellurium nanocrystals (Chem-Te) thin film by liquid phase peeling technique, and demonstrate this material is an effective SA for realization of stable mode-locking in an all-fiber structured Tm-doped laser cavity in 2020, the second-order and third-order harmonic mode-locked pulses train of this fiber laser were also observed, this is the first report on the novel Chem-Te material saturable absorption property realization in 2 μm-band fiber laser system [178]. Xu et al. demonstrated a dual-wavelength harmonic mode-locked EDFL based on a bismuthene SA with large magnitude of third-order nonlinear susceptibility and high carrier motility recently [213], 1st to 20th harmonic mode-locked pulses were obtained when the pump power increased from 43.2 to 201.5 mW, and a 52nd harmonic dual-wavelength pulse (corresponding to the repetition of 208 MHz) was also been obtained when the pump power was larger than 408 mW. The harmonic mode-locking lasers based on 2D Xenes materials have been developed as an important technique to increase the pulse repetition rate [104, 178, 202, 213].

Multiwavelength ultrafast fiber lasers have attracted considerable attention for many applications such as in laser radar systems, optical sensors, biomedical research, and high-bit-rate wavelength-division-multiplexing (WDM) optical communication. In recent years, multiwavelength mode-locked operation are also realized based on 2D Xenes [108, 126, 154, 190, 199, 214]. Figure 13 shows the characteristics of dual-wavelength vector solitons in an EDFL based on BP SA achieved by Yun [190], the dual-wavelength centered at ∼1533 and ∼1558 nm with the bandwidths of ∼3.7 and ∼6.9 nm simultaneously, this work reveals the possibility of few-layered BP as broadband SAs in vector soliton pulses generation. In 2019, Wang et al. reported a switchable and tunable multi-wavelength emissions in pulsed Yb-doped fiber lasers with BP SA and polarization-maintaining fiber Bragg gratings at 1063.8 and1064.1 nm [214]. In addition, a three synchronous wavelengths mode-locked EDFL at 1557.2, 1557.7, and 1558.2 nm based on BP SA was realized by Zhao et al. [108], this is the first report about the application of BP as an SA for building a multiwavelength synchronous mode-locked fiber laser.

![Figure 13:

Mode-locked characteristics of an EDFL based on BP SA:

(A) Optical spectrum. (B) Autocorrelation traces. (C and F) Polarization-resolved oscilloscope traces of dual-wavelength conventional solitons. (D) RF spectrum. (E) RF spectrum with a span of 100 Hz. Reproduced with permission [190].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_013.jpg)

Mode-locked characteristics of an EDFL based on BP SA:

(A) Optical spectrum. (B) Autocorrelation traces. (C and F) Polarization-resolved oscilloscope traces of dual-wavelength conventional solitons. (D) RF spectrum. (E) RF spectrum with a span of 100 Hz. Reproduced with permission [190].

In the laser mode-locked process of 2D Xenes materials, bound soliton pulses are also observed [104, 173, 180]. For example, Liu et al. obtained the soliton molecule with a repetition rate of 10.36 MHz in an EDFL based on BP QDs SA, which was fabricated by using tapered fiber, both traditional soliton and noise-like pulse were also investigated in this work [180]. In 2019, Wang et al. reported on fs soliton molecules generation in EDFL based bismuthene SA, as presented in Figure 14, dual-pulses, octonary-pulses and fourteen-pulses soliton molecules with tightly and loosely temporal separation can be achieved due to the outstanding nonlinear effect and semimetal of the bismuthene, the separations of bound pulses have small variations [104]. It was founded that different spectral modulations were caused by the different widths and peak intensities of the constructed solitons within the bound state.

![Figure 14:

Material characterization:

(A) HR-TEM image. (B) Nonlinear transmittance. Soliton molecules mode-locked characteristics. (C) The spectrum with fourteen soliton molecule. (D) Autocorrelation trace. (E) Optical spectrum. (F) Autocorrelation trace of the bound-state. Reproduced with permission [104].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_014.jpg)

Material characterization:

(A) HR-TEM image. (B) Nonlinear transmittance. Soliton molecules mode-locked characteristics. (C) The spectrum with fourteen soliton molecule. (D) Autocorrelation trace. (E) Optical spectrum. (F) Autocorrelation trace of the bound-state. Reproduced with permission [104].

Notably, dark solitons were also observed in the mode-locked EDFL based on 2D Xenes materials. The mechanism of generating dark solitons in a fiber laser with a net anomalous dispersion can be explained by domain-wall theory, in which two leasing beams originated from two Eigen operation states of fiber laser are coupled incoherently with each other. For example, Liu et al. demonstrated the dark solitons with a repetition rate of 14.68 MHz in an EDFL based on a BP SA, as depicted in Figure 15, BP SA were deposited on side-polished fiber by optically-driven deposition method [210], this obtained results provided an important understanding of dynamics of the dark soliton.

![Figure 15:

Material characterization:

(A) Experimental setup for optically-driven deposition of BP on side-polished fiber (EDFA:erbium-doped fiber amplifier) and the schematic structure of the BP-based nonlinear device and the crystal structure of BP-layer with top view. (B) The Raman spectrum of BP. (C) Dark solitons mode-locked operation. (D) Optical spectrum. Reproduced with permission [210].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_015.jpg)

Material characterization:

(A) Experimental setup for optically-driven deposition of BP on side-polished fiber (EDFA:erbium-doped fiber amplifier) and the schematic structure of the BP-based nonlinear device and the crystal structure of BP-layer with top view. (B) The Raman spectrum of BP. (C) Dark solitons mode-locked operation. (D) Optical spectrum. Reproduced with permission [210].

It is found that compared with Kerr lens mode-locked technology, 2D materials based SAs has more advantages such as self-starting and alignment-free. For ease of application, 2D materials are usually coated on high reflectivity mirrors and then used as cavity mirrors. Notably, a mode-locked Nd:GdVO4 bulk laser operating at 1.34 μm was realized by using BP SAM by Sun et al. in 2017 [197], the pulse duration was 9.24 ps which is the shortest among the mode-locked 1.34 μm neodymium lasers ever obtained with other 2D materials SA.

Table 3 only counts the sub-ps level mode-locked lasers based BP as SA, there are many other meaningful works were listed in Ref [200], [201], [202], [203], [204], [205], [206], [207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212]. These findings deepen the understanding of nonlinear dynamics of soliton operation, and further demonstrate that the 2D Xenes based SA may operate as a high-performance photonic device for exploring nonlinear optical phenomena.

Performance summary of mode-locked fiber lasers based on 2D Xenes SAs.

| 2D materials | Fabrication method | Incorporation method | Modulation depth (%) | λ (nm) | RF (MHz) | SNR (dB) | Duration (fs) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimonene | Vapor deposition | D-shaped fiber | 7.1 | 1562.64 | – | 64.7 | 753 | [112] |

| Antimonene | LPE | Fiber endface | 9 | 1564 | 2.16 | – | 1.73 ns | [102] |

| Antimonene | LPE | Tapered fiber | 3.96 | 1557.68 | 10.27 | 50 | 552 | [113] |

| Antimonene | PVD | Film | – | 1914 | 8.65 | 77 | 64 ps | [117] |

| Antimonene | PVD | Film | 23 | 1559 | 0.99 | 70 | 3530 | [163] |

| Bismuthene | SCE | Tapered fiber | 2.2 | 1034.4 | 21.74 | 45 | 30.25 ps | [164] |

| Bismuthene | – | Tapered fiber | 1 | 1035.8 | 21.74 | 29.6 | 54.19 ps | [165] |

| Bismuthene | SCE | Tapered fiber | 5.6 | 1561 | 18.85 | – | 193 | [166] |

| Bismuthene | SCE | Tapered fiber | 2.5 | 1531 | 4 | 56.54 | 1300 | [167] |

| Bismuthene | SCE | Tapered fiber | 2.5 | 1555.7 | 4 | 30 | 1300 | [168] |

| Bismuthene | SCE | Tapered fiber | 2.03 | 1559.18 | 8.83 | 55 | 652 | [169] |

| Bismuthene | SCE | Tapered fiber | – | 1557.5 | 22.74 | 25 | 621.5 | [104] |

| Bismuthene | LPE | SAM | – | 2030 | 16.7 | – | 1 ns | [171] |

| Se-BP | LPE | – | 18.7 | 1579.4 | 12 | 63 | 686 | [172] |

| Selenene | LPE | Tapered fiber | 2.13 | 1555.67 | 13.68 | 65 | 3100 | [173] |

| Silicene | LPE | Tapered fiber | 20 | 1531.48 | 3.35 | 43 | 937 | [174] |

| Tellurene | Anaerobic bacteria | Film | – | – | 18.8 | – | 1810 | [175] |

| Tellurene | Green chemical | – | 4 | 1566.7 | 1.87 | 40 | 3560 | [176] |

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | 27 | 1556.57 | 15.45 | 53 | 829 | [106] |

| 10.5 | 1060.16 | 4.45 | 64 | 465.6 ps | ||||

| Tellurene | LPE | Tapered fiber | 35.64 | 1558.8 | 3.327 | 37.95 | 1030 | [177] |

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | 13.71 | 1971 | 11.17 | 54 | 890 | [178] |

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | – | 1565.58 | 5.0378 | 42.3 | 21.45 ps | [124] |

| Tellurene | LPE | Film | 5.06 | 1573.97 | 12.17 | 55 | 5870 | [98] |

| – | 1063.97 | 12.17 | 55 | 105.82 | ||||

| Se-Te | LPE | Tapered fiber | 3.436 | 1555 | 18.5 | 60 | 889 | [179] |

| – | 10,664 | 18.4 | 57 | 11.7 ps | ||||

| BP | LPE | Tapered fiber | 9 | 1562.8 | 10.36 | 550 | 291 | [180] |

| BP | ME | Fiber endface | – | 1560.5 | 28.2 | 65 | 272 | [181] |

| BP | LPE | Tapered fiber | 9 | 1532–1570 | 4.96 | 50 | 940 | [182] |

| BP | – | – | – | 1564.6 | 3.47 | – | 690 | [183] |

| BP | LPE | Tapered fiber | 8.1 | 1561.7 | 5.47 | 67 | 882 | [184] |

| BP | ME | Fiber endface | – | 1558.7 | 14.7 | 56 | 786 | [185] |

| BP | LPE | – | – | 1562 | 12.5 | 60 | 635 | [186] |

| BP | LPE | Tapered fiber | 10.1 | 1549–1575 | 60.5 | 68 | 280 | [187] |

| BP | ME | Fiber endface | 4.1 | 1910 | 36.8 | 70 | 739 | [188] |

| BP | LPE | – | 7.75 | 1560 | 15.2 | 65 | 580 | [189] |

| BP | LPE | Fiber endface | 0.35 | 1558 | 28.8 | 60 | 700 | [190] |

| BP | – | Fiber endface | 12.57 | 1567.2 | – | 60 | 538 | [191] |

| BP | ME | Fiber endface | 8.1 | 1550 | – | – | 720 | [192] |

| BP (QDs) | LPE | Film | 4.9 | 1568.5 | 15.16 | 64 | 787 | [193] |

| BP | LPE | Film | 20.1 | 1859 | 20.95 | 60 | 139 | [194] |

-

SCE: sonochemical exfoliation.

Furthermore, besides the single scheme, hybrid mode-locked was also demonstrated. Solid state lasers are usually composed of free-space cavity. They are formed by mirrors using doped glass or crystal host materials as solid-state gain media and most commonly applied in science research, military and medical. Figure 16 displays typical schematic diagram of a partial spatial structure lasers. Table 4 summarizes the performance of mode-locked non-all fiber lasers based on BP SAs. Gao et al. reported a passively Q-switched mode-locked (QML) dual-wavelength Nd:YSAG lasers works at 1058.97 and 1061.49 nm based on BP SA, as shown in Figure 16G, the QML operation was realized by designing a Z-type resonator cavity, the duration of mode-locked pulse inside the Q-switched envelop was estimated to be 235 ps with 96.5 MHz repetition rate [199]. In 2016, based on Er:ZBLAN fiber, Qin et al. demonstrated a mode-locked laser with BP SA at the wavelength of 2.8 μm for the first time, Figure 16K presents that the pulse duration was 42 ps [196]. In 3.5 μm spectral region, Qin et al. proposed a mid-infrared Er:ZBLAN fiber laser based BP as SA, the schematic diagram of experiment is shown in Figure 16D, based on BP SAM, both Q-switched and mode-locked operation were realized, these results show that BP has a great potential as mid-infrared SA beyond 3 μm wavelength, which is lacking currently in this wavelength region [150]. In 2020, Yan et al. demonstrated passively Q-switched all-solid-state lasers operating at 1.0, 2.0, and 2.8 μm by using tellurene/BP heterojunctions, their nonlinear optical absorption properties at 1.0, 2.0, and 2.8 μm have been studied by an open-aperture Z-scan method [125]. The experiment results indicate that 2D Xenes especially 2D Xenes based heterojunctions have great potential in the fields of ultrafast applications and other optoelectronic and photonic devices.

![Figure 16:

Typical schematic diagram of partial spatial structure lasers: (A) Schematic diagram of actively Q-switched fiber laser by the antimonene AOM setup. Reproduced with permission [219]. (B and C) Experimental setup of pulsed fluoride fiber lasers based using BP SA. Reproduced with permission [149]. (D) Schematic of the BP mode-locked Er:ZBLAN fiber lasers. (E) Mode-locked pulse spectrum. (F) Mode-locked pulse train. Reproduced with permission [150]. (G) Experimental setup for QML Nd:YSAG laser. (H) Optical spectrum. (I) The QML pulse trains. Reproduced with permission [199]. (J) Schematic of the mode-locked Er:ZBLAN fiber laser based BP SA. (K) Autocorrelation trace. (L) Optical spectrum. Reproduced with permission [196].](/document/doi/10.1515/nanoph-2022-0045/asset/graphic/j_nanoph-2022-0045_fig_016.jpg)

Typical schematic diagram of partial spatial structure lasers: (A) Schematic diagram of actively Q-switched fiber laser by the antimonene AOM setup. Reproduced with permission [219]. (B and C) Experimental setup of pulsed fluoride fiber lasers based using BP SA. Reproduced with permission [149]. (D) Schematic of the BP mode-locked Er:ZBLAN fiber lasers. (E) Mode-locked pulse spectrum. (F) Mode-locked pulse train. Reproduced with permission [150]. (G) Experimental setup for QML Nd:YSAG laser. (H) Optical spectrum. (I) The QML pulse trains. Reproduced with permission [199]. (J) Schematic of the mode-locked Er:ZBLAN fiber laser based BP SA. (K) Autocorrelation trace. (L) Optical spectrum. Reproduced with permission [196].

Performance summary of mode-locked non-all fiber lasers based on BP SAs.

| 2D materials | Fabrication method | Incorporation method | Gain medium | Modulation depth (%) | λ (nm) | RF (MHz) | Duration (ps) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | LPE | SAM | Nd:YVO4 | 7.5 | 1064.1 | 140 | 6.1 | [195] |

| BP | ME | SAM | Er: ZBLAN | 19 | 2783 | 24.27 | 1.414 | [196] |

| BP | LPE | SAM | Nd:GdVO4 | 16 | 1340.7 | 58.14 | 9.24 | [197] |

| BP | ME | Fiber endface | Zr-Er fiber | 8 | 1602 | 1 | 3.46 | [198] |

| BP | LPE | Film | Ho/Pr fluoride fiber | 41.2 | 2886.7 | 13.987 | 8.6 | [199] |

| BP | LPE | SAM | Er-ZBALAN fiber | 7.7 | 3489 | 28.91 | – | [200] |

| BP | LPE | Film | Nd:YSAG | 11.98 | 1058.97 | 96.5 | 235 | [201] |

6 Conclusions

In this review, we have discussed the ultrafast applications of Xenes beyond graphene. The preparation methods of Xenes and various integration strategies are detailedly introduced at first. Then, according to the materials characterization and nonlinear optical absorption properties we summarize the outcomes achieved by Xenes-based fiber lasers and make classifications based on the characteristics of output pulses. Different from graphene, 2D Xenes materials have outstanding characteristics of tunable bandgap, ultrahigh surface-volume ratio caused by folded structure which have raised widespread concerns in various fields. However, the investigation of 2D Xenes materials SA-based lasers is still in its infancy, as the unique properties of 2D materials can provide fascinating new opportunities and challenges to design the properties through different manufacturing processes because the reliability of these ultrafast optical switches based on 2D nanomaterials are required to be proven to the same extent as existing saturable absorber technology such as SESAM.

Rising enthusiasm in probing varied world of 2D materials constantly promote us to look for novel physical and technological breakthroughs. We believe that 2D Xenes materials could play an important role in future optoelectronic and photonic technologies, particularly as a kind of wideband SA for ultrafast lasers. It is expected that the research in 2D Xenes materials-based all-optical modulation will continue at a fast pace and further exploit practical applications including not only SAs, but also photodetectors, optical modulators, and light-emitting devices.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 11904213

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 61971271, 11904213, 11747149), the Taishan Scholars Project of Shandong Province (Tsqn20161023), Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (ZR2018QF006), the Primary Research and Development Plan of Shandong Province (No. 2019QYTPY020), the Crosswise Project (2021370102131997), and supported by “Opening Foundation of Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Laser Technology and Application”.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] U. Keller, “Recent developments in compact ultrafast lasers,” Nature, vol. 424, pp. 831–838, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01938.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] F. W. Wise, A. Chong, and W. H. Renninger, “High-energy femtosecond fiber lasers based on pulse propagation at normal dispersion,” Laser Photon. Rev., vol. 2, pp. 58–73, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.200710041.Search in Google Scholar

[3] M. E. Fermann and I. Hartl, “Ultrafast fiber laser technology,” IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron., vol. 15, pp. 191–206, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/jstqe.2008.2010246.Search in Google Scholar

[4] R. J. Narayan, “Laser processing of diamond like carbon thin films for medical prostheses,” Int. Mater. Rev., vol. 51, pp. 127–143, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1179/174328406x79432.Search in Google Scholar

[5] P. A. Doble, R. G. de Vega, D. P. Bishop, D. J. Hare, and D. Clases, “Laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry imaging in biology,” Chem. Rev., vol. 121, pp. 11769–11822, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01219.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] D. E. Spence, P. N. Kean, and W. Sibbett, “60-fsec pulse generation from a self-mode-locked Ti:sapphire laser,” Opt. Lett., vol. 16, pp. 42–44, 1991, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.16.000042.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] C. Xu and F. W. Wise, “Recent advances in fiber lasers for nonlinear microscopy,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 875–882, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.284.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] R. R. Gattass and E. Mazur, “Femtosecond laser micromachining in transparent materials,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 2, pp. 219–225, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2008.47.Search in Google Scholar

[9] S. Y. Chou, C. Keimel, and J. Gu, “Ultrafast and direct imprint of nanostructures in silicon,” Nature, vol. 417, pp. 835–837, 2002, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00792.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] J. A. Conchello and J. W. Lichtman, “Optical sectioning microscopy,” Nat. Methods, vol. 2, pp. 920–931, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth815.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] M. E. Fermann and I. Hartl, “Ultrafast fibre lasers,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 868–874, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.280.Search in Google Scholar

[12] C. Jauregui, J. Limpert, and A. Tünnermann, “High-power fibre lasers,” Nat. Photonics, vol. 7, pp. 861–867, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.273.Search in Google Scholar

[13] M. E. Fermann, “Ultrafast lasers: technology and applications,” J. Microsc., vol. 211, p. 101, 2003.10.1046/j.1365-2818.2003.01184.xSearch in Google Scholar

[14] G. P. Agrawa and H. A. Haus, “Applications of nonlinear fiber optics,” Phys. Today, pp. 55–58, 2002.10.1063/1.1496383Search in Google Scholar

[15] M. Brunel, O. Emile, M. Vallet, et al.., “Experimental and theoretical study of monomode vectorial lasers passively Q switched by a Cr4+:yttrium aluminum garnet absorber,” Phys. Rev. A, vol. 60, p. 4052, 1999, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.60.4052.Search in Google Scholar

[16] R. I. Woodward and E. J. R. Kelleher, “2D saturable absorbers for fibre lasers,” Appl. Sci., vol. 5, pp. 1440–1456, 2015, https://doi.org/10.3390/app5041440.Search in Google Scholar

[17] T. Brabec, C. Spielmann, P. F. Curley, et al.., “Kerr lens mode locking,” Opt. Lett., vol. 17, pp. 1292–1294, 1992, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.17.001292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] T. Hasan, Z. Sun, F. Wang, et al.., “Nanotube-polymer composites for ultrafast photonics,” Adv. Mater., vol. 21, pp. 3874–3899, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200901122.Search in Google Scholar

[19] A. F. J. Runge, C. Aguergaray, R. Provo, et al.., “All-normal dispersion fiber lasers mode-locked with a nonlinear amplifying loop mirror,” Opt. Fiber Technol., vol. 20, pp. 657–665, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2014.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

[20] D. Y. Tang and L. M. Zhao, “Generation of 47-fs pulses directly from an erbium-doped fiber laser,” Opt. Lett., vol. 32, pp. 41–43, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.32.000041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] K. Krzempek, G. Sobon, P. Kaczmarek, and K. M. Abramski, “A sub-100 fs stretched-pulse 205MHz repetition rate passively mode-locked Er-doped all-fiber laser,” Laser Phys. Lett., vol. 10, p. 105103, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1088/1612-2011/10/10/105103.Search in Google Scholar

[22] L. Yun and D. D. Han, “Evolution of dual-wavelength fiber laser from continuous wave to soliton pulses,” Opt. Commun., vol. 285, pp. 5406–5409, 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2012.07.114.Search in Google Scholar

[23] N. J. Doran and D. Wood, “Nonlinear-optical loop mirror,” Opt. Lett., vol. 13, pp. 56–58, 1988, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.13.000056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] F. Ilday, F. Wise, and T. Sosnowski, “High-energy femtosecond stretched-pulse fiber laser with a nonlinear optical loop mirror,” Opt. Lett., vol. 27, pp. 1531–1533, 2002, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.27.001531.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] X. X. Shang, L. G. Guo, J. J. Gao, et al.., “170 mW-level mode-locked Er-doped fber laser oscillator based on nonlinear polarization rotation,” Appl. Phys. B, vol. 125, pp. 1–7, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-019-7301-1.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Y. K. Kwon, S. Berber, and D. Tománek, “Thermal contraction of carbon fullerenes and nanotubes,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 92, p. 015901, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.015901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] L. K. Shrestha, Q. Ji, T. Mori, et al., “Fullerene nanoarchitectonics: From zero to higher dimensions,” Chem. Asian J., vol. 8, pp. 1662–1679, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201300247.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] H. T. Li, X. D. He, Z. H. Kang, et al.., “Water‐soluble fluorescent carbon quantum dots and photocatalyst design,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., vol. 49, pp. 4430–4434, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200906154.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] A. Jorio, R. Saito, J. Hafner, et al.., “Structural (n,m) determination of isolated single-wall carbon nanotubes by resonant Raman scattering,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 86, pp. 1118–1121, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.86.1118.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] J. S. Lauret, C. Voisin, G. Cassabois, et al.., “Ultrafast carrier dynamics in single-wall carbon nanotubes,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 90, p. 057404, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.057404.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] M. Zhang, E. J. R. Kelleher, S. V. Popov, et al.., “Ultrafast fibre laser sources: examples of recent developments,” Opt. Fiber Technol., vol. 20, pp. 666–677, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2014.07.005.Search in Google Scholar

[32] F. Wang, A. G. Rozhin, V. Scardaci, et al., “Wideband-tuneable, nanotube mode-locked, fibre laser,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 3, p. 738, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2008.312.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] M. Zhang, E. J. R. Kelleher, A. S. Pozharov, et al.., “Passive synchronization of all-fiber lasers through a common saturable absorber,” Opt. Lett., vol. 36, pp. 3984–3986, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.36.003984.Search in Google Scholar

[34] K. S. Novoselov, A. K. Geim, S. V. Morozov, et al.., “Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films,” Science, vol. 306, pp. 666–669, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102896.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] B. C. Brodie, “XIII. On the atomic weight of graphite,” Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond., vol. 149, pp. 249–259, 1859.10.1098/rstl.1859.0013Search in Google Scholar

[36] P. R. Wallace, “The band theory of graphite,” Phys. Rev., vol. 71, p. 622, 1947, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrev.71.622.Search in Google Scholar

[37] X. X. Shang, L. G. Guo, H. N. Zhang, et al.., “Titanium disulfide based saturable absorber for generating passively mode-locked and Q-switched ultra-fast fiber lasers,” Nanomaterials, vol. 10, p. 1922, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10101922.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] N. Ming, S. N. Tao, W. Q. Yang, et al.., “Mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser based on PbS/CdS core/shell quantum dots as saturable absorber,” Opt. Express, vol. 26, pp. 9017–9026, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.26.009017.Search in Google Scholar

[39] K. D. Niu, R. Y. Sun, Q. Y. Chen, et al.., “Passively mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser based on SnS2 nanosheets as a saturable absorber,” Photon. Res., vol. 6, pp. 72–76, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1364/prj.6.000072.Search in Google Scholar

[40] N. N. Xu, H. F. Wang, H. N. Zhang, et al.., “Palladium diselenide as a direct absorption saturable absorber for ultrafast mode-locked operations: from all anomalous dispersion to all normal dispersion,” Nanophotonics, vol. 9, pp. 4295–4306, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0267.Search in Google Scholar

[41] H. N. Zhang, P. F. Ma, M. X. Zhu, et al.., “Palladium selenide as a broadband saturable absorber for ultra-fast photonics,” Nanophotonics, vol. 9, pp. 2557–2567, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0116.Search in Google Scholar

[42] H. N. Zhang and J. Liu, “Gold nanobipyramids as saturable absorbers for passively Q-switched laser generation in the 1.1 μm region,” Opt. Lett., vol. 41, pp. 1150–1152, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.41.001150.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] K. D. Niu, Q. Y. Chen, R. Y. Sun, et al.., “Passively Q-switched erbiumdoped fiber laser based on SnS2 saturable absorber,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 7, pp. 3934–3943, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.7.003934.Search in Google Scholar

[44] L. G. Guo, X. X. Shang, R. Zhao, et al.., “Nonlinear optical properties of ferromagnetic insulator Cr2Ge2Te6 and its application for demonstrating pulsed fiber laser,” Appl. Phys. Express, vol. 12, p. 082006, 2019, https://doi.org/10.7567/1882-0786/ab2dcc.Search in Google Scholar

[45] P. F. Ma, W. Lin, H. N. Zhang, et al.., “Nonlinear absorption properties of Cr2Ge2Te6 and its application as an ultra-fast optical modulator,” Nanomaterials, vol. 9, p. 789, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9050789.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] S. G. Fu, J. N. Li, S. S. Zhang, et al.., “Large-energy mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser based on indium selenide as a modulator,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 9, pp. 2662–2671, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.9.002662.Search in Google Scholar

[47] R. R. Nair, P. Blake, A. N. Grigorenko, et al.., “Fine structure constant defines visual transparency of graphene,” Science, vol. 320, p. 1308, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1156965.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] J. S. Qiao, X. H. Kong, Z. X. Hu, et al.., “High-mobility transport anisotropy and linear dichroism in few-layer black phosphorus,” Nat. Commun., vol. 5, pp. 1–7, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5475.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] M. Nath, A. Govindaraj, and C. N. R. Rao, “Simple synthesis of MoS2 and WS2 nanotubes,” Adv. Mater., vol. 13, pp. 283–286, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-4095(200102)13:4<283::aid-adma283>3.0.co;2-h.10.1002/1521-4095(200102)13:4<283::AID-ADMA283>3.0.CO;2-HSearch in Google Scholar

[50] T. S. Li and G. Galli, “Electronic properties of MoS2 nanoparticles,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 111, pp. 16192–16196, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp075424v.Search in Google Scholar

[51] A. Splendiani, L. Sun, Y. B. Zhang, et al.., “Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2,” Nano Lett., vol. 10, pp. 1271–1275, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1021/nl903868w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] D. Mao, Y. D. Wang, C. J. Ma, et al.., “WS2 mode-locked ultrafast fiber laser,” Sci. Rep., vol. 5, pp. 1–7, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07965.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] D. Mao, S. L. Zhang, Y. D. Wang, et al.., “WS2 saturable absorber for dissipative soliton mode locking at 1.06 and 1.55 µm,” Opt. Express, vol. 23, pp. 27509–27519, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.23.027509.Search in Google Scholar

[54] X. X. Shang, N. N. Xu, H. N. Zhang, et al.., “Nonlinear photoresponse of high damage threshold titanium disulfide nanocrystals for Q-switched pulse generation,” Opt Laser. Technol., vol. 151, p. 107988, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2022.107988.Search in Google Scholar

[55] M. L. Liu, H. B. Wu, X. M. Liu, et al., “Optical properties and applications of SnS2 SAs with different thickness,” Opto-Electron. Adv., vol. 4, pp. 200029–10, 2021. https://doi.org/10.29026/oea.2021.200029.Search in Google Scholar

[56] H. J. Zhang, C. X. Liu, X. L. Qi, et al.., “Topological insulators in Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 and Sb2Te3 with a single Dirac cone on the surface,” Nat. Phys., vol. 5, pp. 438–442, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1270.Search in Google Scholar

[57] J. E. Moore, “The birth of topological insulators,” Nature, vol. 464, pp. 194–198, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08916.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] N. N. Xu, S. Sun, X. X. Shang, et al.., “Harmonic and fundamental-frequency mode-locked operations in an Er-doped fiber laser using a Cr2Si2Te6-based saturable absorber,” Opt. Mater. Express, vol. 12, pp. 166–173, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.446815.Search in Google Scholar

[59] R. Y. Sun, L. G. Guo, X. X. Shang, et al.., “Efficient saturable absorber based on ferromagnetic insulator Cr2Ge2Te6 in Er-doped mode-locked fiber laser,” Nanomaterials, vol. 12, p. 751, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12050751.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[60] W. J. Liu, T. Shi, M. L. Liu, et al.., “Nonlinear optical property and application of yttrium oxide in erbium-doped fiber lasers,” Opt. Express, vol. 29, pp. 29402–29411, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.433932.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Y. G. Wang, S. Hou, Y. Yu, et al.., “Photonic device combined optical microfiber coupler with saturable-absorption materials and its application in mode-locked fiber laser,” Opt. Express, vol. 29, pp. 20526–20534, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.426654.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] A. Molle, J. Goldberger, M. Houssa, et al.., “Buckled two-dimensional Xene sheets,” Nat. Mater., vol. 16, pp. 163–169, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4802.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] J. P. Ji, X. F. Song, J. Z. Liu, et al.., “Two-dimensional antimonene single crystals grown by van der Waals epitaxy,” Nat. Commun., vol. 7, pp. 1–9, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13352.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] F. Yang, A. O. Elnabawy, R. Schimmenti, et al.., “Bismuthene for highly efficient carbon dioxide electroreduction reaction,” Nat. Commun., vol. 11, pp. 1–8, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14914-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[65] Y. M. Wang, W. Feng, M. Q. Chang, et al.., “Engineering 2D multifunctional ultrathin bismuthene for multiple photonic nanomedicine,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 31, p. 2005093, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202005093.Search in Google Scholar

[66] J. Zhou, J. C. Chen, M. X. Chen, et al.., “Few‐layer bismuthene with anisotropic expansion for high‐areal‐capacity sodium‐ion batteries,” Adv. Mater., vol. 31, p. 1807874, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201807874.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[67] J. Gou, L. J. Kong, X. Y. He, et al.., “The effect of moiré superstructures on topological edge states in twisted bismuthene homojunctions,” Sci. Adv., vol. 6, p. eaba2773, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba2773.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[68] T. C. Niu, W. H. Zhou, D. C. Zhou, et al.., “Modulating epitaxial atomic structure of antimonene through interface design,” Adv. Mater., vol. 31, p. 1902606, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201902606.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] E. Martínez‐Periñán, M. P. Down, C. Gibaja, et al.., “Antimonene: a novel 2D nanomaterial for supercapacitor applications,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 8, p. 1702606, 2018.10.1002/aenm.201702606Search in Google Scholar

[70] K. Khan, A. K. Tareen, M. Aslam, et al.., “Synthesis, properties and novel electrocatalytic applications of the 2D-borophene Xenes,” Prog. Solid State Chem., vol. 59, p. 100283, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progsolidstchem.2020.100283.Search in Google Scholar

[71] T. Nagao, J. T. Sadowski, M. Saito, et al.., “Nanofilm allotrope and phase transformation of ultrathin Bi film on Si (111)-7× 7,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 93, p. 105501, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.93.105501.Search in Google Scholar

[72] S. Choi, T. Kwon, A. Coskun, et al.., “Highly elastic binders integrating polyrotaxanes for silicon microparticle anodes in lithium ion batteries,” Science, vol. 357, pp. 279–283, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal4373.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Y. C. Zhang, Y. You, S. Xin, et al.., “Rice husk-derived hierarchical silicon/nitrogen-doped carbon/carbon nanotube spheres as low-cost and high-capacity anodes for lithium-ion batteries,” Nano Energy, vol. 25, pp. 120–127, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.04.043.Search in Google Scholar

[74] J. Ryu, D. K. Hong, S. Choi, et al.., “Synthesis of ultrathin Si nanosheets from natural clays for lithium-ion battery anodes,” ACS Nano, vol. 10, pp. 2843–2851, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b07977.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] K. Khan, A. K. Tareen, L. Wang, et al.., “Sensing applications of atomically thin group IV carbon siblings Xenes: progress, challenges, and prospects,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 31, p. 2005957, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202005957.Search in Google Scholar

[76] R. Vargas-Bernal, “Electrical properties of two-dimensional materials used in gas sensors,” Sensors, vol. 19, p. 1295, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19061295.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[77] J. T. Robinson, F. K. Perkins, E. S. Snow, et al.., “Reduced graphene oxide molecular sensors,” Nano Lett., vol. 8, pp. 3137–3140, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1021/nl8013007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[78] J. Ouyang, C. Feng, X. Y. Ji, et al.., “2D monoelemental germanene quantum dots: synthesis as robust photothermal agents for photonic cancer nanomedicine,” Angew. Chem., vol. 131, pp. 13539–13544, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201908377.Search in Google Scholar

[79] W. Tao, N. Kong, X. Y. Ji, et al.., “Emerging two-dimensional monoelemental materials (Xenes) for biomedical applications,” Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 48, pp. 2891–2912, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cs00823j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] A. J. Mannix, Z. Zhang, N. P. Guisinger, et al.., “Borophene as a prototype for synthetic 2D materials development,” Nat. Nanotechnol., vol. 13, pp. 444–450, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0157-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed