AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

-

Wiku Andonotopo

, Muhammad Adrianes Bachnas

, Julian Dewantiningrum

Abstract

The development of facial musculature and expressions in the human fetus represents a critical intersection of developmental biology, neurology, and evolutionary anthropology, offering insights into early neurological and social development. Fetal facial expressions, shaped by Cranial Nerve VII, reflect evolutionary adaptations for nonverbal communication and exhibit minimal asymmetry in universal expressions. Advancements in 4D ultrasound imaging and artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced innovative methods for analyzing these movements, revealing their potential as diagnostic tools for neurodevelopmental disorders like Bell’s Palsy and Ramsay Hunt Syndrome before birth. These technologies promise early interventions that could significantly improve neonatal outcomes. By integrating imaging, AI, and longitudinal studies, researchers propose a multidisciplinary approach to establish diagnostic criteria for fetal facial movements. However, translating these advancements into clinical practice requires addressing ethical and practical challenges, refining imaging and AI methodologies, and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. The review highlights the universality of fetal expressions while emphasizing the importance of distinguishing typical variability from pathological markers. In conclusion, these findings suggest transformative potential for maternal-fetal medicine, paving the way for proactive strategies to manage neurodevelopmental risks. Focused research is essential to fully harness these innovations and establish a new frontier in perinatal science.

Introduction

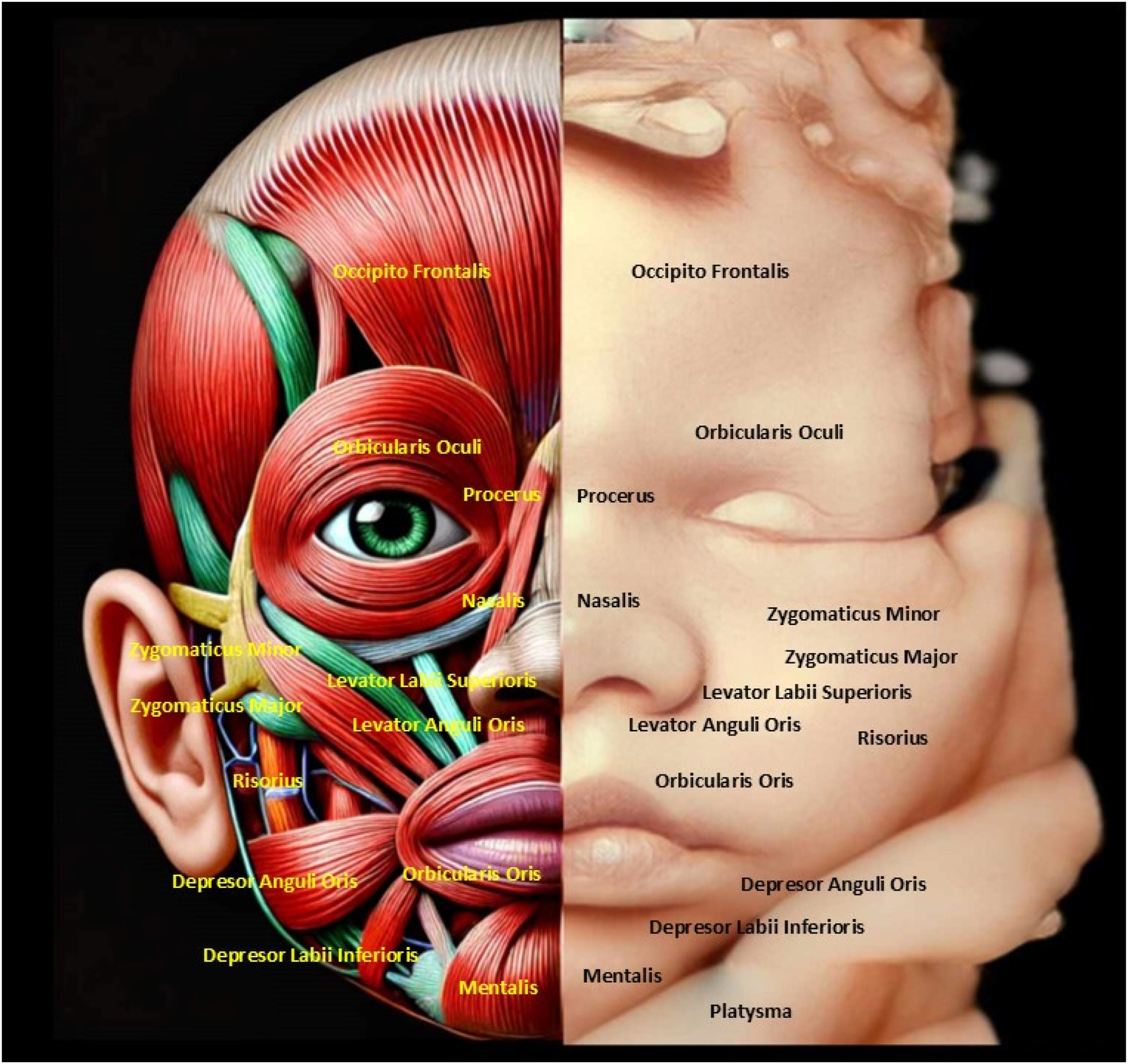

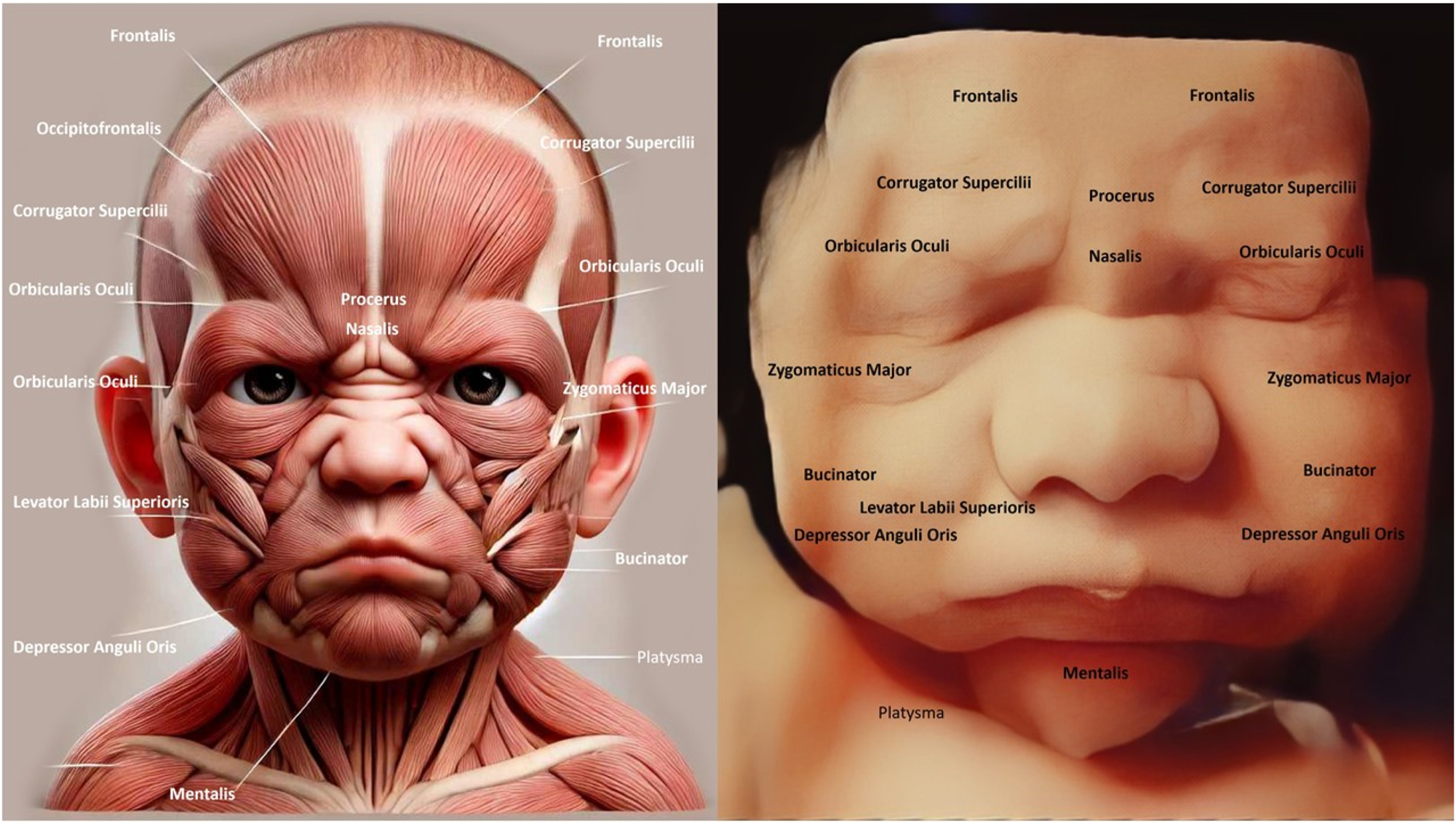

Advancements in prenatal imaging and artificial intelligence now allow for detailed analysis of fetal facial movements, emphasizing their diagnostic potential in identifying neurodevelopmental disorders (Figure 1) [1], [2], [3]. By integrating insights from anatomy, neurology, and technology, these tools hold transformative implications for maternal-fetal medicine. Understanding the development and function of facial expressions not only advances evolutionary biology but also paves the way for innovative approaches in prenatal care and surgical applications.

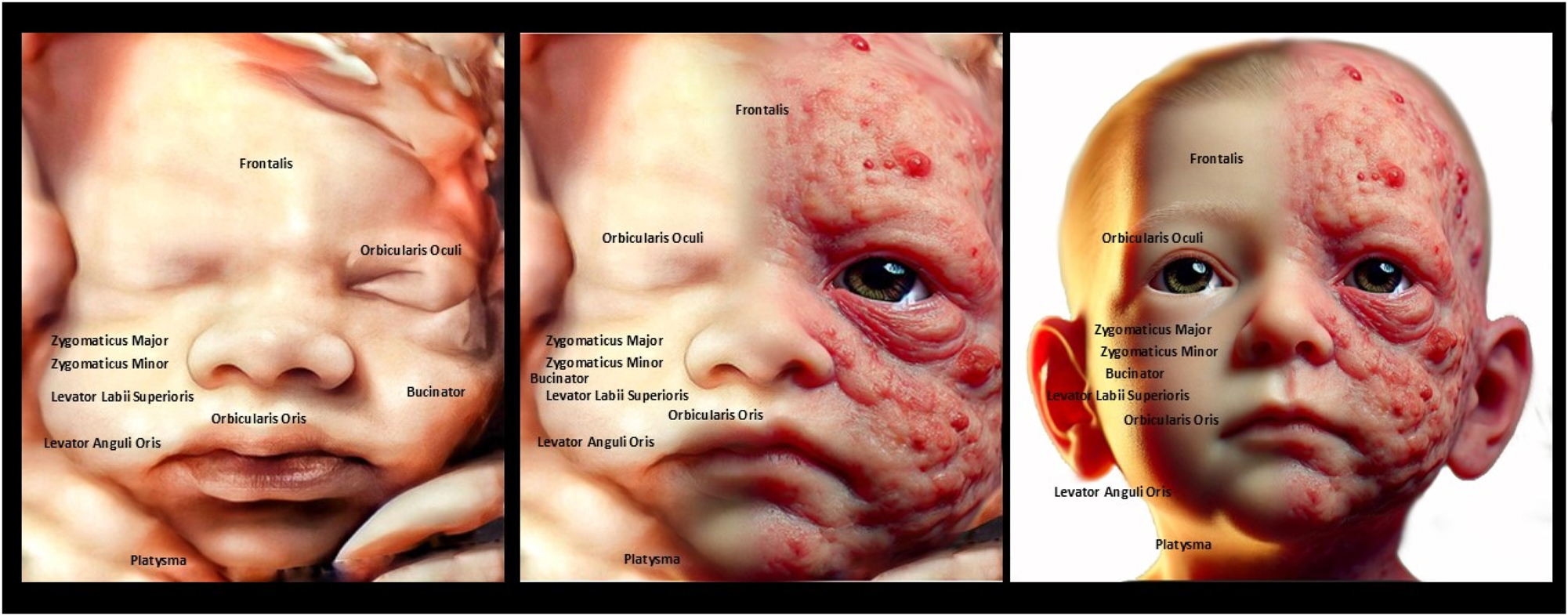

The image highlights the anatomical structure of fetal facial muscles alongside a 4D ultrasound, emphasizing symmetry and development. Understanding fetal facial anatomy and expressions is crucial for detecting congenital anomalies and assessing neurological health. This integration of imaging and anatomy enables early intervention and reassures parents about the fetus’s well-being.

Facial expressions, as a fundamental form of nonverbal communication, provide vital cues about emotions, intentions, and states of mind, reflecting their significance in human interaction. Early studies by Duchenne de Boulogne using electrical stimulation revealed the coordinated activity of facial muscles in creating expressions, though the precise function of individual muscles remains incompletely understood, posing challenges for reconstructive surgery. During fetal development, the emergence of facial expressions offers a unique perspective on neurological and social maturation, highlighting the interplay between cranial nerve development, particularly Cranial Nerve VII, and facial musculature [4].

Despite individual variability in facial muscle anatomy, universal expressions such as happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust are remarkably consistent. Research demonstrates that the muscles responsible for these expressions exhibit 100 % occurrence and minimal asymmetry, suggesting evolutionary selection for their critical communicative function. These findings underscore the adaptive significance of facial expressions while accommodating anatomical variation among individuals [5], 6].

Characterizing fetal facial muscular expressions

The study of fetal facial expressions has long been a subject of fascination for researchers in the field of developmental psychology, as it provides valuable insights into the complex neurological and physiological processes that underlie the development of human emotion and communication. Fetal facial expressions are particularly intriguing because they can be observed and analyzed even before birth, offering a unique window into the early stages of emotional and social development [4].

Facial expression analysis has been a topic of extensive research, with the development of various tools and techniques for detecting and recognizing facial muscle movements and their associated emotional states [7]. These methods, such as facial Action Unit intensity estimation and facial expression recognition, have been widely applied in fields ranging from human-computer interaction to mental health assessment [7], 8]. Specifically, the Facial Action Coding System developed by Ekman and Friesen has been a widely used framework for categorizing and analyzing facial expressions [4], 9].

However, the application of these techniques to the study of fetal facial expressions has been limited, as the unique challenges posed by the in utero environment and the inherent complexity of fetal facial movements require specialized approaches.

Mapping fetal facial muscle expressions

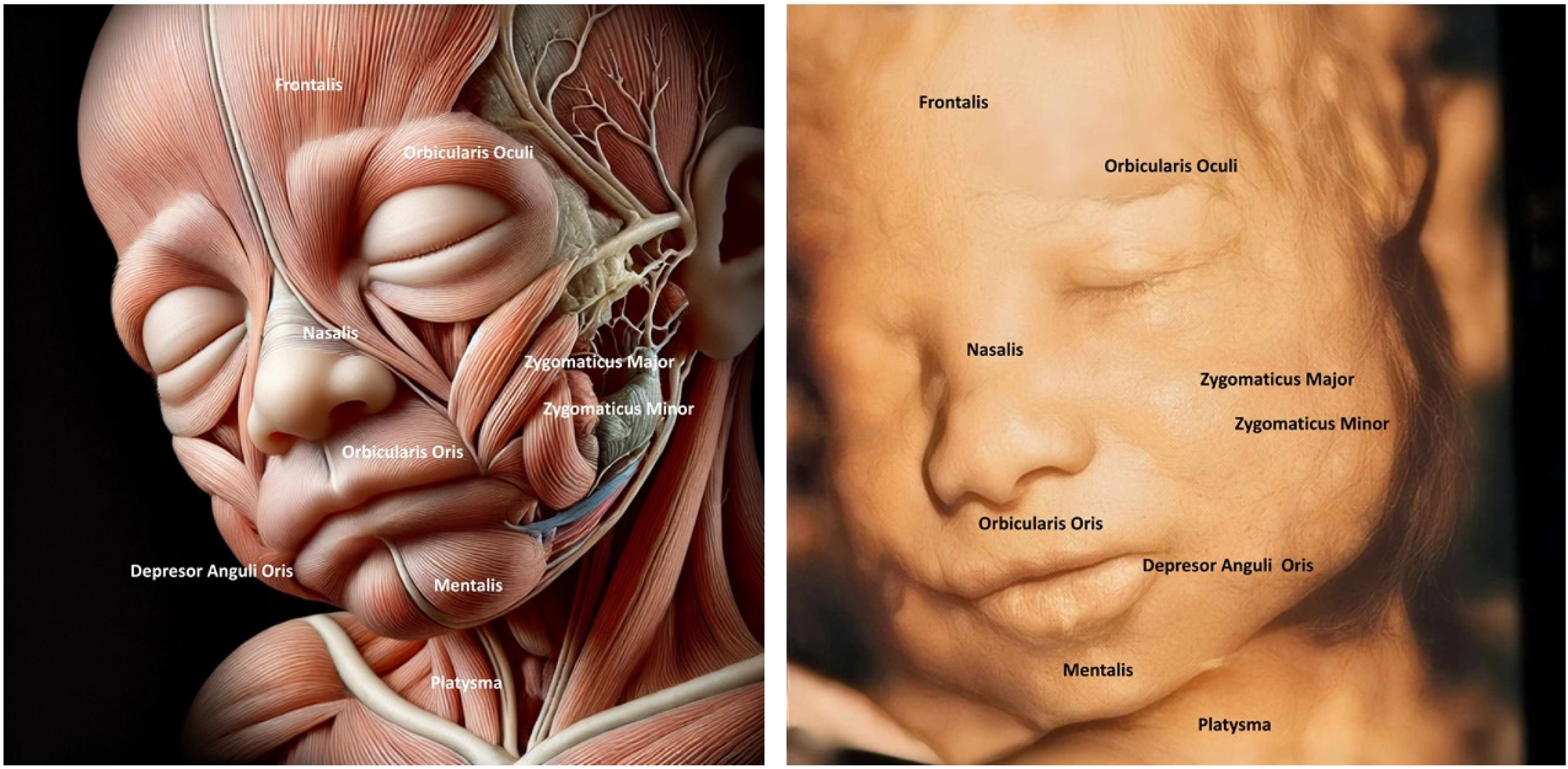

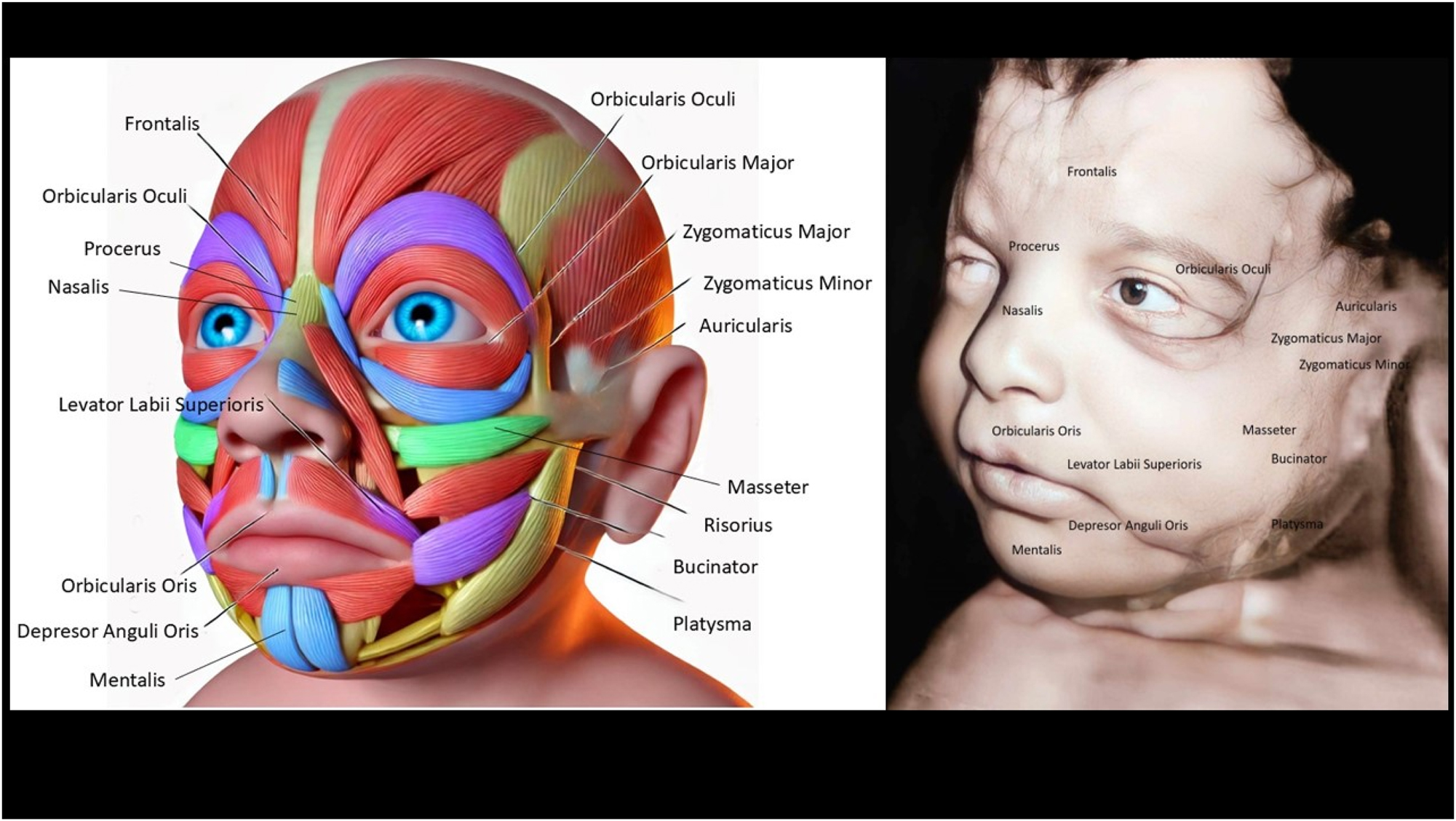

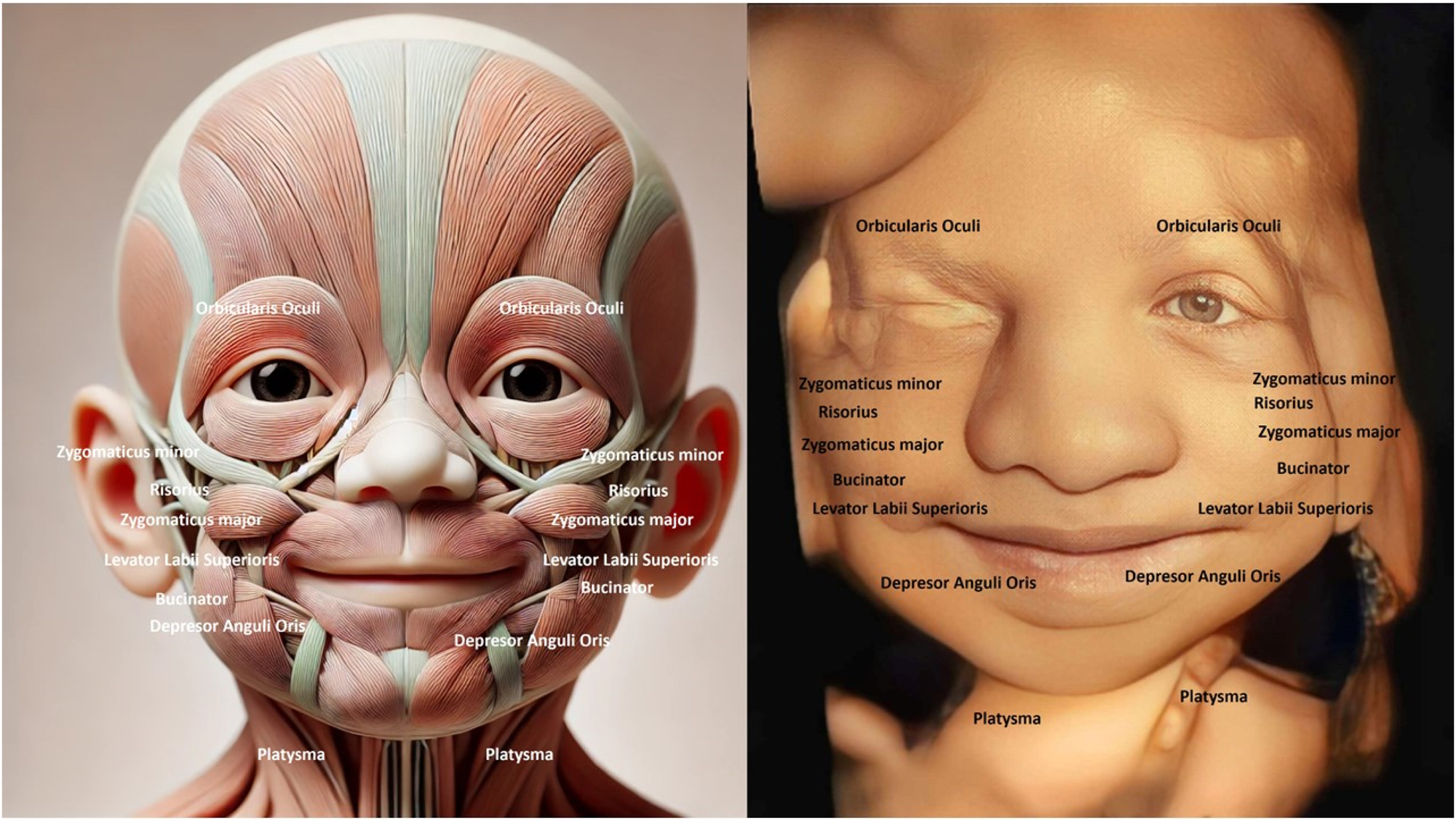

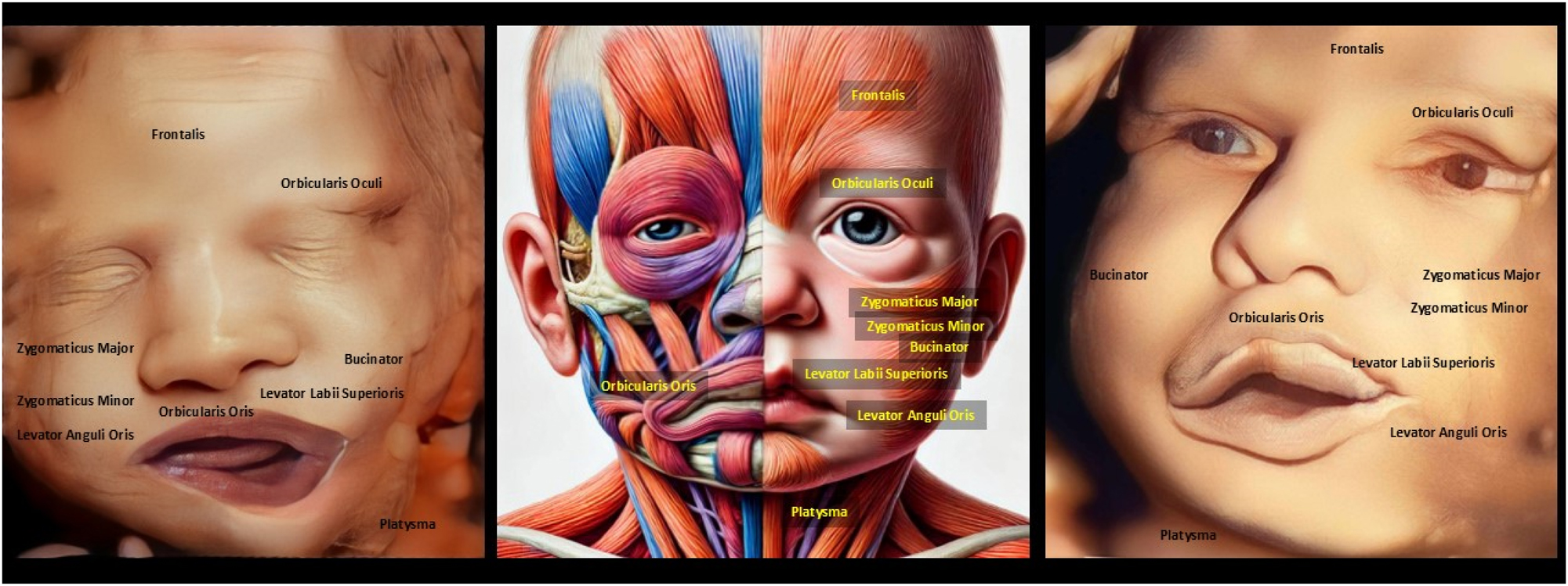

The study of fetal facial muscle expressions has long been a topic of fascination within the fields of developmental psychology and neonatal research (Figures 1–5). Duchenne de Boulogne’s laid the groundwork for our understanding of the complex coordination of facial muscles involved in emotional expression [4] Recent advances in medical imaging technology have allowed researchers to observe the development of these expressive capabilities in utero, providing valuable insights into the origins of human nonverbal communication [6].

The image compares fetal facial muscle anatomy (left) with a 4D ultrasound of a fetal face (right), highlighting muscles like Orbicularis Oculi and Zygomaticus Major. The fetal face shows a relaxed or neutral expression, indicating developing neuromuscular coordination. Understanding fetal facial anatomy and expressions is crucial for detecting anomalies like cleft lip or muscular underdevelopment, which could affect postnatal function.

The image contrasts the detailed anatomy of fetal facial muscles (left) with a 4D ultrasound of a fetal face (right), showing muscles like Orbicularis Oculi and Zygomaticus Major. The ultrasound reveals a neutral facial expression, reflecting developing muscle coordination and symmetry. Assessing the fetal face helps detect congenital issues like cleft lip or muscular defects and provides insights into neurological health. This enables early diagnosis, intervention, and reassures parents of healthy fetal development.

The image compares fetal facial muscle anatomy (left) with a 4D ultrasound of a fetal face (right), showing key muscles like Zygomaticus Major, Orbicularis Oculi, and Depressor Anguli Oris. The fetal face displays a slight smile-like expression, indicating early neuromuscular coordination. Observing the fetal face helps detect structural or functional abnormalities, such as cleft lip or muscle defects, which may impact postnatal development. This analysis also provides insights into neurological and muscular health, reflecting proper fetal development.

The image compares the fetal facial muscle anatomy (left) with a 4D ultrasound of a fetal face (right), showing structures like Orbicularis Oculi, Zygomaticus Major, and Corrugator Supercilii. The ultrasound reveals a frown-like expression, indicating early muscle activity and coordination. Examining the fetal face is crucial for detecting abnormalities like cleft lip or muscle defects that may affect postnatal function. It also reflects neurological health, as facial expressions demonstrate proper brain and nerve development.

One key question that has emerged is how the universality of certain facial expressions, such as happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust, can be reconciled with the known variability in facial musculature between individuals. This apparent paradox has been the subject of extensive investigation, with researchers exploring the hypothesis that the muscles essential for producing these “universal” expressions have been subject to strong evolutionary selection pressures [6].

As part of a broader effort to understand the evolutionary factors shaping human communication, societies, and cognitive processes, a comparative analysis of primate facial expression and its underlying musculature is crucial [5]. The findings of Ekman and Friesen’s landmark study on the universality of emotion-related facial expressions support the idea that these expressions are biologically innate and evolutionarily adaptive, rather than purely learned behaviours [10]. Further research has revealed that the facial muscles responsible for these universal expressions exhibit a high degree of consistency and minimal asymmetry, even in the presence of individual variation in overall facial musculature [6].

Taken together, these findings suggest that the human face has evolved to facilitate the production and interpretation of essential nonverbal communicative signals, as a means of navigating the social environment. By mapping the development of these facial expression muscles in the fetus, researchers can gain valuable insights into the origins and evolutionary significance of this crucial aspect of human communication.

Surveying fetal facial muscle displays

Prenatal development is a complex and intricate process, with numerous physiological and behavioral changes occurring within the womb. One particularly fascinating aspect of fetal development is the emergence and evolution of facial muscle movements, which can provide valuable insights into the overall maturation of the central nervous system [11].

Facial expressions in fetuses have been a subject of scientific inquiry for decades, with researchers utilizing various techniques to capture and analyze these subtle movements. One such approach involves the use of real-time video analysis, which can segment the image of the fetus and focus on specific areas of interest, such as the face [12]. This method has been explored in studies examining the feasibility of monitoring the condition of premature infants, as the status of the eyes and other facial features can serve as important markers for neonatal neurodevelopmental state [12].

Similarly, observations of various components, including motor, vocal, and facial activities of the newborn, have been shown to be valuable in understanding the progression of fetal development [13]. Analyzing the patterns of coordinated lower facial muscle function can also provide critical information about the development of facial reanimation and the potential for restoring facial animation in the context of reconstructive surgery [4].

General trends in fetal facial musculature

The intricate and dynamic nature of fetal facial musculature has long been a topic of fascination for researchers in the field of human development. Recent studies have shed light on the patterns of coordinated lower facial muscle function, which play a crucial role in the development of facial expression and reanimation [4]. Pioneering research in the 19th century established the foundational understanding of facial muscles and their role in emotional expressions [4]. Although the precise functions of individual muscles remain incompletely understood, the coordinated activity of multiple muscle groups is recognized as crucial for producing the diverse range of facial expressions [4].

The muscles of facial expression, often referred to as the “cosmetic muscles,” are responsible for the formation of wrinkles, lines, and folds that are indicative of the aging process [14]. Interventions targeting these muscles can have profound effects on the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the face, highlighting their importance in both aesthetic and functional aspects of facial anatomy.

An overview of the names and functions of facial muscles in the developing fetus

Facial muscles in the developing fetus begin forming early in gestation and are crucial for various functions post-birth, such as feeding and communication. These muscles originate from the mesoderm and undergo differentiation to form distinct structures (Table 1) (Figures 1–5). The main facial muscles include the orbicularis oris, responsible for lip movement, essential for sucking and later speech. The orbicularis oculi control the closing of the eyelids, which helps protect the eyes and manage facial expressions. The zygomatic muscles are involved in creating expressions, like smiling, and play a role in emotional signalling. The frontalis muscle, which raises the eyebrows, contributes to facial expressions of surprise or interest. The buccinator muscle assists in maintaining food in the mouth during feeding, a vital function for newborns. These muscles are innervated by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), which coordinates complex facial movements. As the fetus develops, these muscles prepare for actions like sucking, swallowing, and initial facial expressions. By the third trimester, the muscles have formed well enough to allow limited facial movements visible in ultrasound scans, indicating readiness for neonatal life [4], 6], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26].

Detailed overview of facial muscles involved in human expressions: origins, insertions, innervations, and functions.

| Muscle name | Primary function | Expression | Origin | Insertion | Innervation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontalis | Elevates eyebrows and wrinkles forehead | Surprise or curiosity | Galea aponeurotica | Skin of eyebrows | CN VII (facial) |

| Orbicularis oculi | Closes eyelids | Blinking, squinting, winking | Medial orbital margin | Skin around the orbit | CN VII (facial) |

| Zygomaticus major | Elevates and retracts corner of mouth | Smiling, laughter | Zygomatic bone | Corner of the mouth | CN VII (facial) |

| Zygomaticus minor | Elevates the upper lip | Smiling, happiness | Zygomatic bone | Upper lip | CN VII (facial) |

| Levator labii superioris | Elevates the upper lip | Sadness or disdain | Infraorbital margin | Upper lip | CN VII (facial) |

| Orbicularis oris | Compresses and protrudes lips | Puckering, kissing | Maxilla and mandible | Skin around lips | CN VII (facial) |

| Buccinator | Compresses cheeks | Blowing, sucking, anger | Alveolar processes of maxilla and mandible | Orbicularis oris | CN VII (facial) |

| Depressor anguli oris | Depresses corner of mouth | Frowning, sadness | Mandible | Corner of mouth | CN VII (facial) |

| Mentalis | Elevates and protrudes lower lip | Pouting, doubt | Mandible | Skin of chin | CN VII (facial) |

| Risorius | Draws corner of mouth laterally | Smiling, smirking | Fascia over masseter | Corner of mouth | CN VII (facial) |

| Platysma | Tenses neck skin, depresses mandible | Fear, tension | Fascia of chest | Mandible, lower face skin | CN VII (facial) |

| Corrugator supercilii | Draws eyebrows medially and downward | Anger, concentration | Frontal bone above nasal bone | Skin of eyebrows | CN VII (facial) |

| Procerus | Wrinkles skin of the nose | Disdain, anger | Nasal bone and cartilage | Skin between eyebrows | CN VII (facial) |

| Nasalis | Compresses or flares nostrils | Disgust, effort | Maxilla | Nasal cartilage | CN VII (facial) |

| Levator anguli oris | Elevates corner of mouth | Smiling, happiness | Maxilla below infraorbital foramen | Corner of mouth | CN VII (facial) |

| Depressor labii inferioris | Depresses lower lip | Sadness, doubt | Mandible | Lower lip | CN VII (facial) |

Forehead muscles

The muscles of the forehead play a crucial role in facial expression, allowing individuals to convey a wide range of emotions through subtle movements. The frontalis muscle, which originates from the anterolateral portion of the aponeurotic galea and inserts into the deep layer of the skin along the entire length of the forehead, is primarily responsible for elevating the eyebrows [27].

The frontalis muscle has no bony attachment and instead blends with the depressor muscles of the eyebrow at the orbital rim, allowing for coordinated movements between the opposing muscle groups. Additionally, the glabellar muscles, which act to depress the eyebrow, are separated into two opposing groups that work in tandem with the frontalis muscle to control the position and expression of the eyebrows [27].

Midface muscles

The muscles of the midface, including the orbicularis oculi and the zygomaticus major and minor, play a crucial role in creating a wide range of facial expressions. The orbicularis oculi, for instance, is responsible for the involuntary and spontaneous contraction of the muscles around the eyes, which is a key component of a genuine smile. The zygomaticus major and minor muscles, on the other hand, are responsible for pulling the corners of the mouth upward and outward, creating a characteristic “smile” expression [28].

Eyebrow muscles

The human eyebrow is a prominent feature of the face, serving not only aesthetic purposes but also playing a crucial role in various facial expressions and nonverbal communication. Understanding the underlying anatomy and function of the muscles responsible for eyebrow movement is essential for both medical and cosmetic applications.

The forehead and glabellar muscles can be divided into two opposing groups based on their actions: those that elevate the eyebrow and those that depress it. The frontalis muscle, which originates from the aponeurotic galea and inserts into the deep layer of the skin along the entire length of the forehead, is primarily responsible for elevating the eyebrow [27]. This muscle has no bony attachment, allowing it to blend with the depressor muscles of the eyebrow at the orbital rim, enabling precise control of eyebrow positioning [27]. In contrast, the depressor muscles, such as the corrugator supercilii and procerus, work to pull the eyebrow downward, creating a furrowed or angry expression [14].

Disruptions in the delicate balance between the opposing muscle groups can lead to various aesthetic and functional concerns, such as eyebrow asymmetry, excess skin laxity, or impaired visual field. Interventions targeting these muscles, such as Botox injections or surgical procedures, can profoundly affect the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the face, influencing the formation of wrinkles and the overall facial aging process [14].

Eyelid muscles

The human eyelid is a complex structure composed of several distinct muscles that work in harmony to facilitate various functions, including blinking, eye closure, and protection of the delicate ocular surface. Impairment or alteration of these muscles can have significant consequences, even in the context of vision [29].

The orbicularis oculi muscle is the primary muscle responsible for eyelid closure. It consists of two distinct portions: the palpebral portion, which controls blinking, and the orbital portion, which facilitates full eye closure. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle is responsible for elevating the upper eyelid, allowing for an adequate visual field [29], 30]. The interaction between these muscles, as well as the surrounding soft tissue structures, is crucial for maintaining proper eyelid function and positioning.

The anatomical relationship between the eyelid and the midface is also of importance. The lid-cheek junction corresponds to the transition from the palpebral to the orbital portions of the orbicularis oculi muscle, with the malar fat pad lying superficial to this region [31]. Disruption of this delicate balance can lead to undesirable aesthetic outcomes, such as lateral canthal distortion and chemosis, which may occur following certain surgical procedures. In addition to the primary eyelid muscles, the Mueller’s muscles, which are found within the eyelids, play a vital role in maintaining the appropriate visual field.

Nose muscles

Facial expressions are a fascinating aspect of human communication, and the intricate network of muscles that govern these expressions has been a topic of extensive research in the fields of neuroscience, psychology, and anthropology. One crucial component of this complex system is the set of muscles responsible for the movement and positioning of the nose.

The nose, often overlooked in the study of facial expressions, plays a vital role in conveying a wide range of emotions [32]. The muscles responsible for the nose’s movements are a key part of the overall facial musculature, and their coordinated action is essential for the production of universal facial expressions [4]. These muscles, such as the procerus, the levator palpebrae superioris, and the compressor naris, work together to create a multitude of subtle yet meaningful expressions [4].

Interestingly, research has shown that despite the vast individual variation in facial musculature, the specific muscles responsible for the production of universal facial expressions, such as happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust, are present in all individuals and exhibit minimal asymmetry [6]. This suggests that these muscles have been selected for their essential role in nonverbal communication, as the ability to convey these emotions is deemed crucial for navigating the social environment.

Cheek muscles

The human face is a complex and intricate structure, with a myriad of muscles working in harmony to facilitate a wide range of expressions and functions. Among these, the cheek muscles play a crucial role in shaping the appearance of the face and contributing to various nonverbal communication cues.

Facial esthetics are heavily influenced by the condition and tone of the cheek muscles [33]. The cheeks are typically the most visible region of the face, supported by teeth, ridges, and muscles, and thus play a significant role in facial aesthetics [33]. Concavities and hollowing of the cheeks can be caused by the loss of molars, total edentulism, age-related decrease in muscular tone, and weight loss, leading to a loss or reduction in cheek fullness and a slumped, emaciated appearance that can make the patient appear older. To address this, the use of a cheek plumper has been recommended for geriatric populations, even after restoring the vertical jaw relation, to provide additional support for the oral musculature [33].

The muscles of facial expression, including the cheek muscles, have been studied extensively, with the pioneering work of Duchenne de Boulogne using electrical stimulation and photography to systematically examine their function [4]. These muscles are often referred to as the “cosmetic muscles” due to their role in the formation of wrinkles and lines associated with the aging process. The individual action of facial muscles, however, is not fully understood, and the patterns of coordinated activity among groups of muscles that create facial expressions are still being mapped out, representing a significant limitation for reconstructive surgeons attempting to restore facial animation [4].

Lip muscles

The human lips are an intricate and essential component of the facial anatomy, playing a crucial role in various functions such as speech, facial expression, and the consumption of food and liquids. Understanding the muscles that govern the movement and shape of the lips is crucial for both medical and aesthetic purposes.

The lips are framed by a series of muscles that work in tandem to control their static and dynamic positions. The inferior limit of the lips in the central region is the mentolabial sulcus, and the philtrum and its pillars are considered part of the upper lip [34]. The surface of the lip is composed of four distinct zones: hairy skin, vermilion border, vermilion, and oral mucosa. The normal shape of the lips can vary with age and ethnicity, with the vermilion, the red part of the lips, playing a key role in the overall aesthetic appearance [35].

The intrinsic muscles of the tongue, such as the longitudinal, transverse, and vertical muscles, are responsible for changing the shape of the tongue, while the extrinsic muscles, such as the genioglossus, hyoglossus, and styloglossus, are responsible for moving the tongue in different directions [36]. The lips and tongue work in conjunction to perform various functions, including speech, taste perception, and the manipulation of food during the digestive process.

Chin muscles

The chin, a prominent feature of the human face, is not merely a bony protrusion but a complex structure comprising a network of intricate muscles that play a vital role in various facial expressions and functional activities. Understanding the anatomy and functions of these chin muscles is crucial for both aesthetic and medical applications, such as facial reconstruction, rehabilitation, and cosmetic procedures.

One of the primary muscles of the chin is the mentalis muscle, which originates from the mandibular symphysis and inserts into the skin of the chin. This muscle is responsible for elevating the lower lip, producing a pouting expression, and is also involved in tongue protrusion and swallowing [4].

Mandible muscles

The mandible is home to several muscles, including the masseter, temporalis, and medial and lateral pterygoid muscles, which collectively are known as the masticatory muscles (Herring et al. [37]). These muscles are responsible for the opening and closing of the jaw, as well as the lateral and protrusive movements that are essential for proper mastication.

The specific architecture and arrangement of these muscles have a significant impact on their functional capabilities. Muscles with a complex internal structure, partitioned by multiple aponeuroses, can precisely control the chewing movements of the mandible [38]. Additionally, the length of the muscle fibers determines the range of motion for the jaw, which is modified by the overall shape and size of the corresponding aponeurosis [38].

The forces generated by the masticatory muscles also have a profound effect on the surrounding skeletal structures. The contractions of these muscles can result in torsion, bending, and tension within the zygomatic bones, nasal bones, and cranial sutures, as the mandible acts as a third-class lever during mastication.

This complex interplay between the mandible, masticatory muscles, and facial skeleton is what gives rise to the diverse range of facial expressions that humans are capable of [38], 39]. By understanding the biomechanics and functional anatomy of the mandible and its associated musculature, researchers can gain valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying our ability to convey emotion and communicate through facial gestures [37], 38].

Platysma muscle

The platysma muscle, a sheet-like muscle located in the neck, plays a crucial role in facial expressions and the aging process. This muscle, which originates from the fascia of the upper chest and inserts into the skin of the lower face, is responsible for a variety of facial movements [14]. Understanding the anatomy and functions of the platysma muscle is essential for facial rejuvenation and reanimation procedures.

The platysma muscle is part of the group of muscles known as the “muscles of facial expression.” These muscles, which include the corrugator supercilii, orbicularis oculi, and zygomaticus major, are responsible for the dynamic lines and wrinkles that form on the face with age [14]. The coordinated action of these muscles is crucial for creating facial expressions, but their individual contributions to specific expressions are not fully understood [4].

Interventions targeting the platysma muscle can have profound effects on the lower third of the face. The deep-plane facelift technique, for example, utilizes dissection in the sub-SMAS/deep plane, which allows for direct lysis of the zygomatic cutaneous ligament, the major facial retaining ligament. This approach also enables the mobilization of facial fat, including the buccal fat, and can address issues such as pseudoherniation that contribute to jowling [40].

Moreover, the aging of the midfacial skeleton, including the descent of the cheek mass and deepening of the nasolabial fold, is an important factor in facial aging. Surgical techniques that reposition the malar fat pad and soft tissues overlying the angle of the mandible, such as the endobrow-midface lift, can help to address these changes and achieve a more youthful and balanced facial appearance [41].

Auricular muscles

The auricular muscles, also known as the extrinsic ear muscles, are a group of small muscles located around the external ear that play a crucial role in the voluntary movement and positioning of the auricle (the visible part of the ear). These muscles are innervated by various cranial nerves, including the facial nerve, and their functions are not limited to simply moving the ear, but also contribute to the overall hearing process [42].

The human ear is a complex anatomical structure, with the external ear consisting of the auricle and external auditory canal. The auricle, or pinna, is a flap of skin and cartilage that surrounds the opening of the external auditory canal and is responsible for collecting and directing sound waves into the ear. The auricular muscles are attached to the auricle and are responsible for the voluntary movement and positioning of the ear, which can help in the localization of sound and the enhancement of hearing in certain situations [43].

The auricular muscles can be divided into three main groups: the anterior, superior, and posterior auricular muscles. The anterior auricular muscle is responsible for pulling the auricle forward, while the superior auricular muscle pulls the auricle upward, and the posterior auricular muscle pulls the auricle backward [36]. These muscles are innervated by the facial nerve, which is responsible for the voluntary movement of the face and ears.

In addition to their role in the movement of the auricle, the auricular muscles also play a part in the overall hearing process. The auricular muscles can adjust the position of the auricle, which can help in the localization of sound and the enhancement of hearing in certain situations, such as when trying to hear a distant sound or a specific sound in a noisy environment.

Trochlear muscles

The trochlear muscles, also known as the superior oblique muscles, are a crucial component of the ocular system, responsible for the complex and precisely coordinated movements of the eyes. These muscles, which originate from the back of the eye socket and insert onto the upper, outer aspect of the eyeball, play a vital role in the control and function of fixational eye movements.

Fixational eye movements, though often overlooked, are essential for maintaining visual acuity and preventing visual fading [44]. These small, involuntary movements, including tremor, drift, and microsaccades, serve to counteract the natural tendency of the visual system to adapt to static stimuli, ensuring that the image on the retina is constantly refreshed. The precise control of these movements is facilitated by the coordinated action of the trochlear muscles, which work in conjunction with other extraocular muscles to stabilize the gaze and prevent image blur.

The importance of the trochlear muscles in ocular function is underscored by the debilitating consequences of their impairment or alteration. For instance, altered mechanoreception in the human trabecular meshwork cells, which are sensitive to mechanical stimuli, can lead to increased intraocular pressure and potentially contribute to the development of glaucoma. Furthermore, the mechanoreceptive Müller muscles in the eyelid, which are essential for the contraction of the levator muscles against the weight of the eyelid, are crucial for maintaining an adequate visual field [29].

Likewise, the impact of trochlear muscle dysfunction on strabismus, a condition characterized by an imbalance of the extraocular muscles resulting in deviation of the visual axes, highlights the importance of these muscles in binocular alignment and coordination.

Orbicularis oculi muscle

The orbicularis oculi muscle, a vital component of the human eye, is a complex and intricate structure that plays a crucial role in the functioning of the visual system. This muscle, situated around the eye, is responsible for the contraction and relaxation of the eyelids, enabling the critical process of blinking [30].

The muscle’s geometric heterogeneity and multiple functions suggest that it may be partitioned in a task-dependent manner, as evidenced by the varying timing and amplitude of electromyographic activity observed across different recording sites within the muscle [45]. This task-dependent partitioning may reflect an aspect of cortical organization, as some facial motoneurons in primates, including humans, are monosynaptically activated from area 4 of the motor cortex [45].

The orbicularis oculi muscle is situated within the orbital cavity, a bony structure that houses the eye and its associated structures. The muscle is composed of several distinct parts, each with its own function and contribution to the overall movement and protection of the eye. While the eyelids are often overlooked in ocular studies, they play a crucial role in ocular maintenance, particularly through the mechanism of blinking.

Corrugator supercilii muscle

The corrugator supercilii muscle, a small yet remarkably complex facial muscle, has been a focal point of scholarly inquiry within the fields of anatomy, physiology, and psychology. Recognized as a crucial component in the intricate coordination of facial expressions, this muscle has attracted significant attention from researchers aiming to elucidate its precise role in human communication and emotional expression. Historical advancements in the 19th century provided foundational insights into the involvement of the corrugator supercilii in producing frowning expressions [4].

Procerus muscle

The procerus muscle, a small but essential component of the facial musculature, plays a crucial role in the expression of human emotion and the facilitation of various facial movements. This muscle, which originates from the nasal bone and inserts into the skin of the glabella and lower forehead, is responsible for the characteristic furrowing of the brow, a common expression associated with displeasure, concentration, or effort [6].

The procerus muscle’s functional significance extends beyond its role in emotional expression. It is also a vital component in the coordination of lower facial movements, contributing to the overall fluidity and synchronicity of facial animation [4]. The procerus muscle’s coordinated action with other facial muscles, such as the corrugator supercilii and the frontalis, is essential for the proper execution of complex facial expressions [4].

Anatomical studies have revealed that the procerus muscle exhibits a high degree of variability in its presence and morphology among individuals. This variability, however, does not compromise the muscle’s ability to fulfil its essential function in the production of universal facial expressions, such as anger, fear, and disgust [6]. The universality of these expressions suggests that the facial muscles, including the procerus, have been subject to evolutionary selection pressures to ensure effective nonverbal communication.

Levator palpebrae superioris muscle

The levator palpebrae superioris muscle is a vital component of the human eye, responsible for the elevation of the upper eyelid, a crucial function that enables clear vision and proper eye protection. This muscle, situated within the orbit, operates in conjunction with the Mueller’s muscle to facilitate the opening and closing of the eyelid, a process that is essential for maintaining ocular health and visual acuity [29].

The complex interplay between the levator palpebrae superioris and other facial muscles, such as the orbicularis oris, has been the subject of extensive research, with studies demonstrating the interconnectedness of these structures and their roles in facial rejuvenation and expression [46]. Alterations in the function or structure of the levator palpebrae superioris can lead to a range of ocular conditions, including ptosis, a condition characterized by the drooping of the upper eyelid, which can significantly impair visual function [47].

Levator anguli oris muscle

The levator anguli oris muscle, also known as the caninus muscle, is a small yet essential facial muscle responsible for the elevation and retraction of the angle of the mouth. Located in the midface, this muscle plays a crucial role in various facial expressions, including smiling, pouting, and grimacing. Anatomically, the levator anguli oris muscle originates from the canine fossa, a depression on the maxilla just above the root of the canine tooth, and inserts into the angle of the mouth, blending with the orbicularis oris and zygomaticus major muscles.

The precise action of the levator anguli oris muscle is to pull the angle of the mouth upward and slightly backward, resulting in the elevation and retraction of the corner of the mouth. This movement is particularly important in the formation of a genuine smile, as the contraction of the levator anguli oris muscle, along with other perioral muscles, helps to elevate the corners of the mouth and expose the upper teeth [48], 49].

Zygomaticus major muscle

The zygomaticus major muscle, also known as the zygomatic major, is a crucial component of the human facial anatomy, playing a pivotal role in the expression of various emotional states. This muscle, located on the cheek, originates from the zygomatic bone and inserts into the angle of the mouth, contributing to the elevation and retraction of the corners of the lips during smiling and other positive facial expressions [4], 49].

The zygomaticus major muscle is innervated by the buccal branch of the facial nerve, which travels along the zygomatic arch and inserts into the underside of the muscle’s fibers [50]. This strategic positioning of the nerve allows for precise control and coordination of the muscle’s actions, enabling intricate and nuanced facial expressions [49].

The zygomaticus major muscle’s role in facial expression is well-documented. The smile, one of the most universally recognized and socially important facial expressions, is initiated by the flexing of the muscles surrounding the oral cavity, including the zygomaticus major. This muscle’s contribution to the smile is particularly significant, as it is responsible for the characteristic upward and outward movement of the corners of the mouth, creating the distinct expression of joy and happiness.

Beyond its role in smiling, the zygomaticus major muscle is also involved in other facial expressions, such as laughter, amusement, and even certain expressions of surprise or delight. The interplay between the various muscles of facial expression, including the zygomaticus major, is crucial for the formation of wrinkles and creases that are indicative of the aging process [14].

Zygomaticus minor muscle

The zygomaticus minor muscle, also known as the pars infraorbitalis, is a small but crucial component of the facial musculature that plays a vital role in various facial expressions and functions. Despite its diminutive size, this muscle has garnered significant attention from researchers and clinicians alike, as its intricate anatomy and coordinated actions with other facial muscles are crucial for maintaining facial symmetry and emotional expression.

The zygomaticus minor muscle originates from the zygomatic bone, just inferior to the lateral aspect of the orbital rim, and inserts into the skin of the cheek, inferior to the lateral aspect of the eye [50]. This muscle’s primary function is to elevate the corner of the mouth, contributing to the formation of a genuine smile [49]. However, its coordinated actions with other facial muscles, such as the orbicularis oculi, frontalis, and corrugator supercilii, are essential for a wide range of facial expressions, from expressing joy and happiness to conveying more complex emotional states [4], 49].

Depressor anguli oris muscle

The human body is an intricate and remarkable system, with each component serving a vital role in maintaining overall physiological balance and function. One such integral element is the depressor anguli oris muscle, a crucial component of the facial musculature.

The depressor anguli oris muscle, also known as the dDAO, is a small facial muscle located in the lower region of the face. It is responsible for pulling the corners of the mouth downward, a movement often associated with expressions of sadness or displeasure [4]. Understanding the anatomy and function of this muscle is crucial, as it plays a significant role in various facial expressions and orofacial functions, such as eating, speaking, and swallowing.

Interestingly, the depressor anguli oris muscle is not present in all individuals, and when present, it can exhibit significant asymmetry in its size and configuration [6]. Despite this variability, the dDAO and other muscles essential for producing universal facial expressions, such as happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust, have been selected for their communicative function, ensuring the ability to convey these emotional states across individuals [6].

Recent studies have shed light on the intricate anatomy and relationships of the dDAO. Specifically, researchers have identified the presence of medial fibers of the dDAO that pass deep to the depressor labii inferioris muscle, a finding that was previously overlooked. This anatomical arrangement highlights the complexity of the facial musculature and the importance of understanding the precise relationships between individual muscles for both clinical and reconstructive applications.

Mentalis muscle

The muscles of the face play a crucial role in the expression of emotions and nonverbal communication. Among these, the mentalis muscle, located in the chin, has a significant impact on the lower third of the face [3], 14]. Understanding the function and characteristics of the mentalis muscle is essential for understanding how facial expressions are produced and how they contribute to social interactions.

The mentalis muscle is responsible for pulling the lower lip upward and pushing the chin forward, creating a pouting or protruding expression. This muscle is one of the key players in the coordinated movements of the lower facial muscles that contribute to the formation of various facial expressions, such as the smile [4]. The mentalis muscle’s actions, in conjunction with other facial muscles, can also contribute to the development of wrinkles and creases associated with facial aging [14].

The patterns of coordination among the facial muscles, including the mentalis, have been a subject of extensive study. Researchers have sought to understand the specific ways in which groups of muscles work together to create the rich repertoire of facial expressions that are universally recognized and essential for social communication [6]. However, the individual actions of facial muscles, as well as their coordinated function, remain incompletely understood, representing a significant challenge for reconstructive surgeons aiming to restore facial animation.

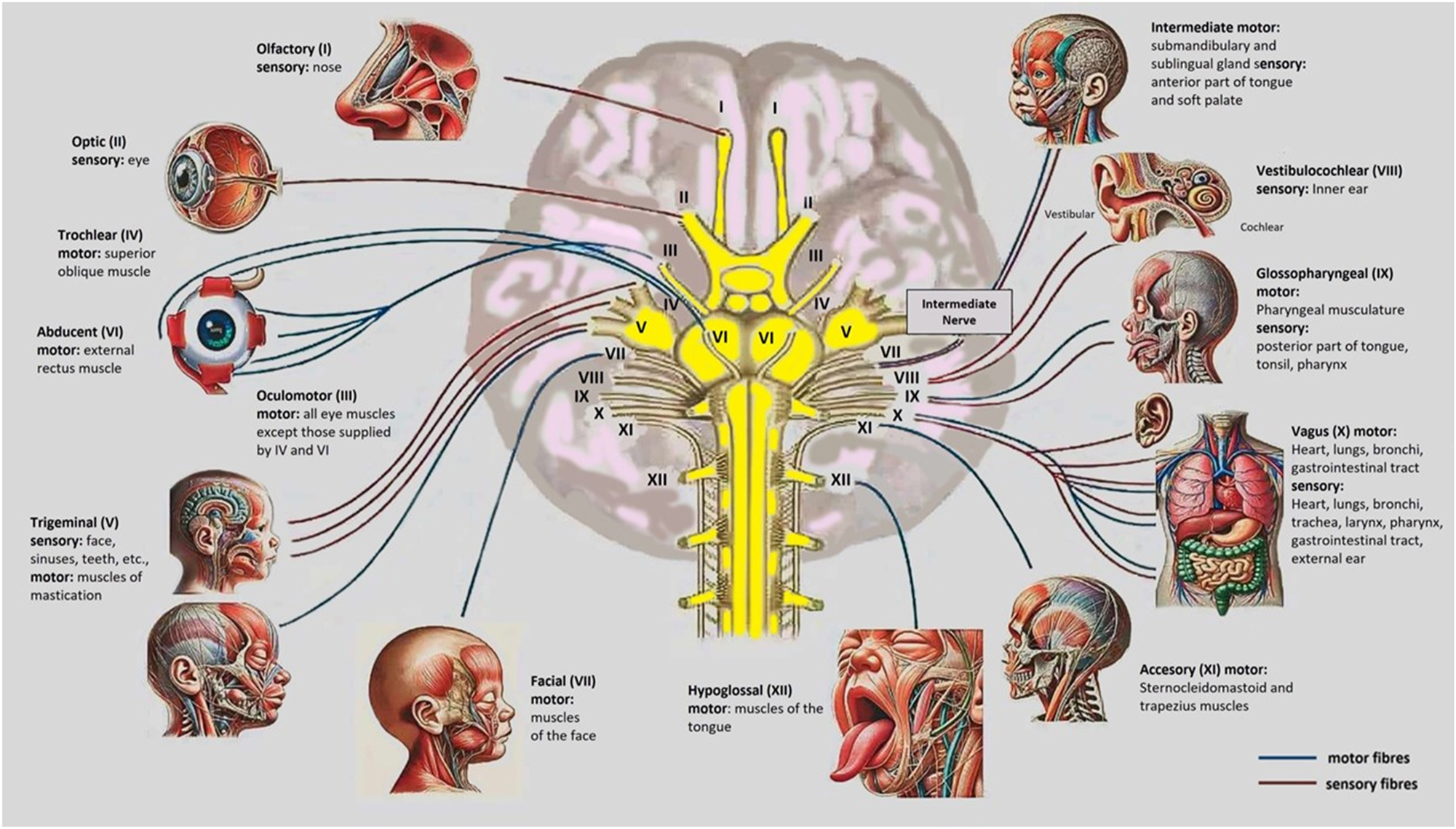

Unraveling the relationship between cranial nerve VII and fetal facial behaviors

Cranial nerve VII, also known as the facial nerve, plays a crucial role in the development and functionality of the human face, as it innervates the majority of the muscles responsible for facial expressions. The coordinated activation of these muscles allows for a wide range of facial movements and behaviours, which are particularly evident in the fetal stage of development (Figure 6).

The image illustrates the 12 cranial nerves in the baby’s brain, detailing their motor and sensory functions. It shows nerves like the Olfactory (I) for smell, Optic (II) for vision, and Facial (VII) for expressions and taste, along with others managing eye movement, hearing, balance, swallowing, and autonomic functions. This picture is valuable as an educational tool for understanding cranial nerve anatomy and its roles in development. It aids in diagnosing potential nerve dysfunctions affecting sensory or motor systems in infants. Additionally, it provides a clinical reference for monitoring neurological health and guiding early interventions if necessary.

The dorsal region of the facial nucleus, which is part of the facial nerve, supplies innervation to the muscles of the upper face, while the ventral region innervates the muscles of the lower face [51]. This arrangement results in the left hemisphere partially controlling the upper left and right sides of the face, and fully controlling the lower right side of the face. The sensory root of the facial nerve is also responsible for providing taste function to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, controlling lacrimation, and regulating the stapedial reflex, which is associated with the output of the sublingual and submandibular glands [52].

Disruptions in the normal embryological migratory pathway of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neural crest cells of the olfactory placode and basal forebrain can lead to Kallmann syndrome, a genetic condition characterized by hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and partial or total anosmia, resulting in abnormal sexual development [53]. The central role of the neural crest in this predictive relationship between the face and the brain has been the subject of extensive research, as the face can indeed be a reliable indicator of the underlying brain structure and function [51], 54], 55].

As the embryo develops, the face undergoes a series of closing and re-opening spaces, such as the separation of the nasal and oral cavities, the nostrils, and the eyelids. These developmental processes are closely linked to the migration and differentiation of the neural crest cells, which contribute to the formation of various craniofacial structures, including the bones, cartilage, and connective tissues [55].

The role of other specific cranial nerves and the autonomic nervous system in fetal facial expression development

Facial expressions are a fundamental aspect of human communication and emotion, and their development is a complex process that involves the interplay of various neural and muscular systems. While the role of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) in fetal facial expression development has been well-established, the contributions of other cranial nerves and the autonomic nervous system have received less attention [4], [56], [57], [58].

The facial nerve (Figure 6), or cranial nerve VII, is responsible for the movement of the muscles of facial expression, and its development is crucial for the emergence of fetal facial expressions. However, other cranial nerves, such as the oculomotor nerve (III), the trigeminal nerve (V), the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), the vagus nerve (X), and the accessory nerve (XI), as well as the autonomic nervous system, also play a significant role in the development of fetal facial expressions [56], [57], [58].

The oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III) controls the muscles around the eye, including the Levator Palpebrae Superioris, which lifts the upper eyelid. Although it is not directly involved in facial expression, its role in lifting the eyelid can influence the appearance of the eyes, especially in expressions of surprise or fear.

The trigeminal nerve, or cranial nerve V, is responsible for the sensation and movement of the muscles of mastication, including the muscles involved in sucking and swallowing [4]. This nerve may contribute to the development of fetal facial expressions by influencing the movements of the mouth and jaw. The glossopharyngeal nerve, or cranial nerve IX, is involved in the sensation of the posterior third of the tongue and the pharynx, and may contribute to the development of fetal facial expressions through its influence on the movements of the tongue and pharynx [56], [57], [58].

The vagus nerve, or cranial nerve X, is a crucial component of the autonomic nervous system and is responsible for the regulation of various physiological processes, including heart rate, breathing, and gastrointestinal function. The autonomic nervous system may also play a role in the development of fetal facial expressions by influencing the activity of the facial muscles and the expression of emotions [56], [57], [58].

The accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) innervates the muscles of the neck, including the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Tension or movement in these muscles can influence the appearance of the face, particularly in expressions of tension, fear, or when someone is holding back strong emotions [56], [57], [58].

The autonomic nervous system, which includes the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, also plays a role in facial expressions, particularly in deeper emotional responses. For example, a sympathetic response can cause the pupils to dilate when a person is afraid or lead to sweating on the forehead when anxious. These reactions can complement the facial expressions produced by the Facial Nerve. Current research on the role of other cranial nerves and the autonomic nervous system in fetal facial expression development is limited, and further investigation is needed to fully understand the mechanisms involved [4].

Damage to the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII)

Damage to the Facial Nerve is the most common cause of facial expression disorders or paralysis, with conditions such as Bell’s Palsy being a prime example (Figures 8–10). Such damage results in an inability to move the muscles of the face, affecting actions like smiling, frowning, and even the ability to close the eyes (Table 2). The Facial Nerve is the primary nerve responsible for controlling the muscles of facial expression [59], [60], [61], [62].

Effects of cranial nerve damage on fetal facial muscle expression and external appearance.

| Cranial nerve | Muscle(s) affected | Effects of damage | Related disorders | External appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facial nerve (CN VII) | Most facial expression muscles | Paralysis or weakness of facial muscles | Bell’s palsy, ramsay hunt | Drooping of one side of face, asymmetrical smile, inability to close the eye |

| Trigeminal nerve (CN V) | Muscles of mastication (indirect facial tone) | Difficulty chewing or clenching teeth | Trigeminal neuralgia | Sunken cheeks and jaw area due to muscle wasting |

| Oculomotor nerve (CN III) | Eyelid (levator palpebrae superioris) | Drooping upper eyelid (ptosis) | Ptosis | Drooped eyelid partially covering the eye |

| Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) | Stylopharyngeus (indirect facial effect) | Weak swallowing, pharyngeal asymmetry | Dysphagia | Difficulty swallowing, minor throat asymmetry |

| Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) | Tongue muscles (indirect lower face impact) | Deviation of tongue to affected side | Lingual nerve palsy | Uneven tongue position, lower lip asymmetry |

| Accessory nerve (CN XI) | Sternocleidomastoid, trapezius | Weak neck movements, shoulder drooping | Accessory nerve palsy | Drooped shoulders, subtle neck/facial posture effects |

| Optic nerve (CN II) | Vision-related muscles | Loss of coordination, double vision | Strabismus, diplopia | Misaligned or ‘crossed’ eyes affecting expressions |

| Trochlear nerve (CN IV) | Superior oblique | Impaired downward gaze | Trochlear nerve palsy | Slight eye misalignment noticeable in movement |

| Abducens nerve (CN VI) | Lateral rectus | Difficulty moving eye outward | Abducens nerve palsy | Eye turned inward (strabismus) |

Bell’s Palsy is the most common form of unilateral (one-sided) facial paralysis. Although the exact cause is not always clear, it is often linked to a viral infection that leads to inflammation of the nerve. Facial symptoms include weakness or paralysis on one side of the face, resulting in an inability to move the eyebrow, fully close the eye, or smile. The affected side of the face may appear to droop. Patients with Bell’s Palsy may lose the ability to express emotions, such as smiling, frowning, or appearing sad, on the affected side. Additional problems can include decreased tear and saliva production, difficulty speaking or eating, and, in some cases, pain behind the ear [59], [60], [61], [62].

Central Facial Paralysis, on the other hand, can occur due to damage to the motor cortex or the nerve tracts that transmit signals to the Facial Nerve. This type of damage is often caused by a stroke or brain trauma. Symptoms typically involve weakness in the muscles of the lower part of the face, while the muscles in the forehead and eyelids may continue to function well. This is because the nerve control for the forehead originates from both sides of the brain, so damage to one side does not fully impair these muscles. As a result, patients with central facial paralysis may have difficulty smiling or showing emotion in the lower part of the face, while the forehead remains able to wrinkle [59], [60], [61], [62].

Relevance to fetal diagnostics: anatomical insights and their diagnostic implications

Damage to various cranial nerves, such as the Trigeminal, Oculomotor, Glossopharyngeal, Vagus, and Accessory nerves, can indirectly influence facial expression or impair neck and facial functionality. Disorders involving these nerves can range from complete facial paralysis to subtle changes in muscle coordination, depending on the nerve affected (Table 2) (Figure 6). [63], [64], [65], [66]. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome, caused by herpes zoster virus, often leads to facial paralysis with additional symptoms like ear rashes and hearing loss, resembling but extending beyond Bell’s Palsy. Facial neuropathy, arising from trauma, infections, or autoimmune diseases, presents varied symptoms requiring tailored diagnostic approaches (Figure 9), [67], [68], [69].

Damage to the Oculomotor Nerve can impair eye movement and pupil contraction, leading to ptosis and altered expressions of fear or surprise. Trigeminal Nerve dysfunction, responsible for sensation rather than expression, causes intense pain or numbness, which can modify pain-related facial responses. Glossopharyngeal and Vagus nerve injuries can disrupt swallowing and speech, indirectly affecting facial expressions by altering mouth and throat muscle activity. Accessory Nerve damage affects neck and shoulder muscles, potentially influencing facial appearance through changes in posture and muscle tension.

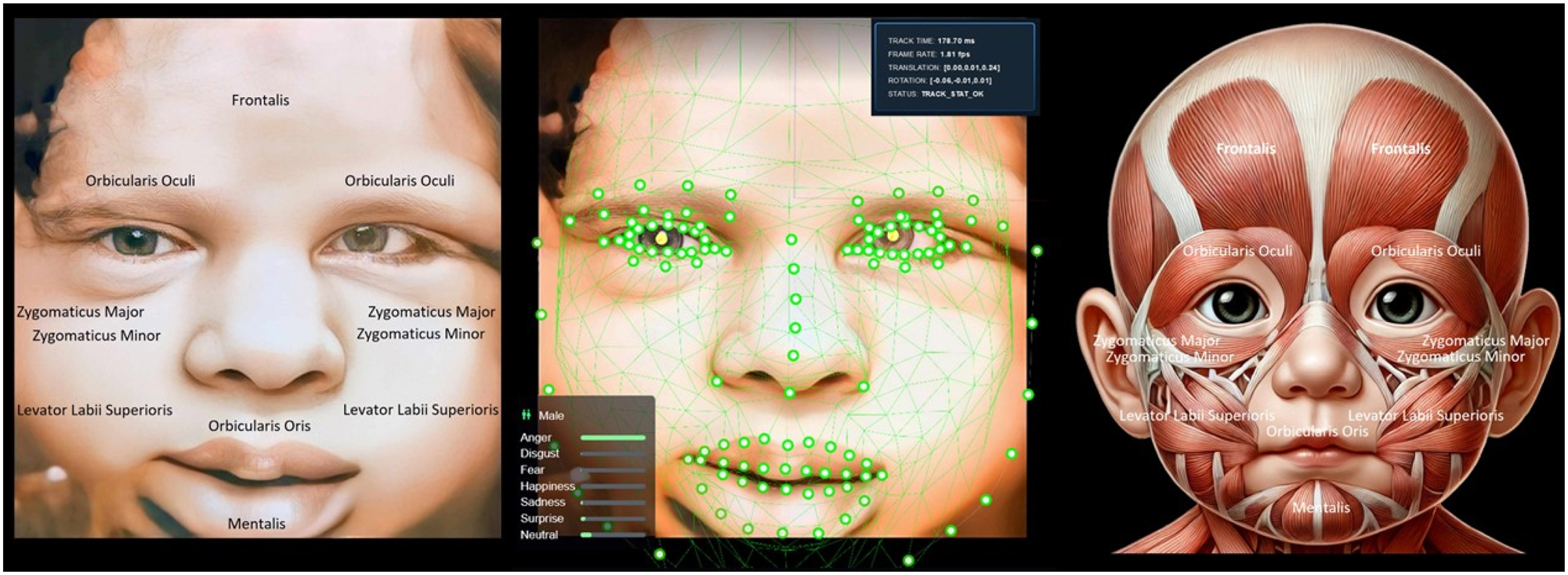

The autonomic nervous system, when impaired, impacts physiological facial responses such as sweating, pupil dilation, and skin coloration. Conditions like Horner’s Syndrome cause asymmetrical features, including ptosis and constricted pupils, which can diminish expressive clarity. 4D ultrasound technology has revolutionized fetal diagnostics by enabling real-time, detailed analysis of facial expressions like smiling, squinting, and frowning (Figures 2–5 and 7) [1], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [[70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76]. This non-invasive method allows clinicians to detect potential abnormalities in cranial nerves or the autonomic system, providing early indications of conditions like Bell’s Palsy or Ramsay Hunt Syndrome.

The image displays a 4D ultrasound view of a baby’s face (left), AI facial tracking analyzing expressions (middle), and fetal facial muscle anatomy (right). The expression shown appears neutral, driven by muscle activity in areas like the Zygomaticus Major and Orbicularis Oris, reflecting neuromuscular coordination rather than emotional realization. Understanding fetal facial conditions is vital for detecting abnormalities like cleft lip and assessing neurological and muscular development. AI facial tracking offers precise, automated evaluation of muscle and nerve functions, helping identify potential developmental issues early. While it does not confirm emotional realization, it reflects the functionality of facial muscles and nerves. This technology supports timely medical interventions and reassures parents about the fetus’s health and development.

The image compares a normal 4D ultrasound with mouth asymmetry (left), a depiction of facial muscle paralysis (middle), and another 4D ultrasound with similar mouth asymmetry (right). Muscle paralysis impacts expressions like smiling, frowning, or pouting due to dysfunction in key muscles such as Orbicularis Oris and Zygomaticus Major. Detecting facial asymmetry in the womb is essential for identifying potential neuromuscular conditions or congenital anomalies that could affect postnatal function. While 4D ultrasound provides detailed imaging of facial structures, it has limitations in diagnosing nerve-related conditions like Bell’s palsy, which may not manifest fully during fetal development. The observed asymmetry could indicate real muscle or nerve issues, but it might also result from temporary factors like fetal movement or positioning. This underscores the need for postnatal assessments to confirm the cause of asymmetry. Overall, 4D ultrasound is a valuable screening tool but requires complementary diagnostics for a comprehensive evaluation of potential abnormalities.

The image compares a normal 4D ultrasound of a baby’s symmetrical face (left), an AI-generated depiction of facial asymmetry from muscle paralysis resembling ramsay hunt syndrome (middle), and an enhanced version of the condition (right). Muscle paralysis affects key expressions like smiling, frowning, and eye closure, involving dysfunction in muscles such as Orbicularis Oris and Zygomaticus Major. Detecting facial asymmetry in the womb is vital for identifying neuromuscular issues that may affect postnatal development. While 4D ultrasound provides detailed structural imaging, it cannot directly diagnose neurological conditions like Ramsay Hunt Syndrome, which involve viral infections. Asymmetry in fetal ultrasounds may result from temporary factors like positioning rather than pathology. Integrating AI with imaging improves diagnostic precision but requires postnatal evaluations for confirmation.

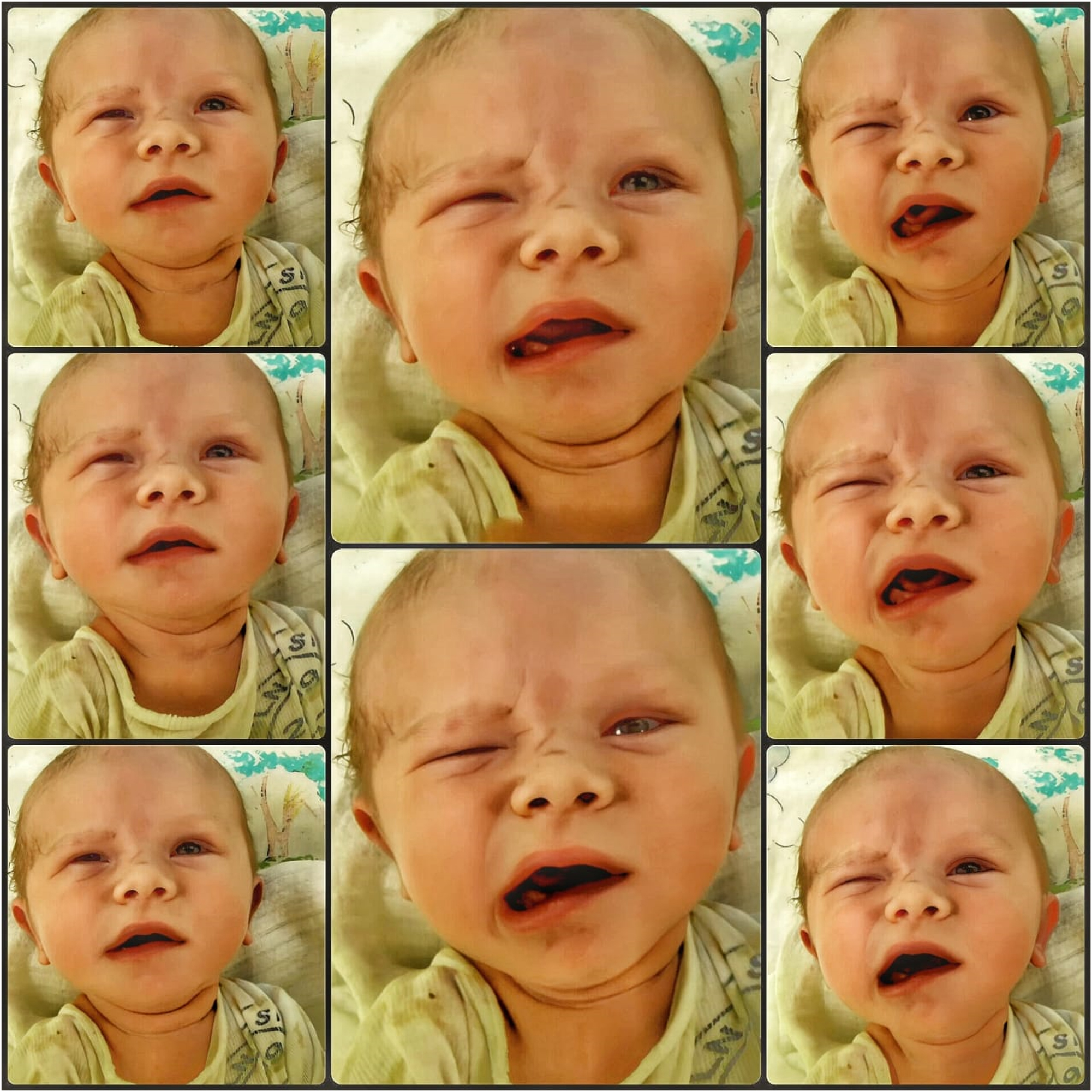

The image depicts a 7-day-old baby with asymmetrical mouth movements during crying, caused by trauma during vaginal delivery. The paralysis affects facial expressions like symmetrical crying and smiling, involving muscles like Orbicularis Oris and Zygomaticus Major. Detecting facial asymmetry in the womb can help anticipate potential delivery-related trauma or neuromuscular issues. 4D ultrasound provides detailed imaging but has limitations in predicting functional issues like muscle paralysis, as these often develop dynamically post-birth. The asymmetry seen here likely results from birth trauma or nerve compression, not congenital Bell’s palsy. However, rare cases of fetal asymmetry on ultrasound could indicate congenital nerve issues requiring postnatal evaluation. Combining prenatal imaging with follow-up assessments is crucial to distinguish between temporary trauma and lasting neuromuscular disorders.

Abnormalities in muscles like the orbicularis oculi, zygomaticus major, or mentalis often reflect developmental or neural issues, with asymmetrical movements serving as a key diagnostic marker. Bell’s Palsy, linked to viral infections or inflammation, may manifest in utero as unilateral facial asymmetry, offering valuable early diagnostic clues. Ramsay Hunt Syndrome, presenting with facial paralysis and ear anomalies, is better identified when facial movement analysis is combined with prenatal viral screenings. AI has enhanced diagnostic precision by automating the detection of subtle movement patterns, uncovering irregularities missed by human observation (Figures 8–10) [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69]. When paired with prenatal MRI, 4D ultrasound provides a comprehensive approach to understanding cranial nerve development and associated disorders [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [[70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76]. These technologies improve diagnostic accuracy, enabling earlier interventions and better neonatal outcomes. Observing fetal expressions also aids parental counseling, helping families anticipate potential risks and plan for postnatal care. The universality of facial expressions highlights their evolutionary importance while emphasizing their diagnostic relevance in fetal health.

Longitudinal studies linking fetal expression patterns to postnatal outcomes are crucial to validating these diagnostic methods and refining their clinical applications. Ethical considerations, such as ensuring equitable access and informed parental decisions, must accompany these technological advancements. Together, these innovations represent a paradigm shift in prenatal care, transforming how developmental and neurological disorders are detected and managed. By leveraging 4D ultrasound, AI, and prenatal MRI, clinicians can advance fetal diagnostics, improving neonatal care and opening new frontiers in understanding human development.

Critical appraisal of technology: current limitations of 4D ultrasound and AI

The integration of 4D ultrasound and artificial intelligence (AI) into fetal diagnostics has significantly advanced the field, but notable challenges remain. Consistent image quality is difficult to achieve, as factors like fetal position, maternal obesity, and amniotic fluid levels can obscure facial features. Temporal resolution, essential for capturing rapid fetal movements, is sometimes insufficient to accurately record subtle expressions. Operator dependency further introduces variability, reducing reproducibility across clinical settings. AI, while promising, suffers from a lack of standardized, high-quality datasets necessary for effective algorithm training. The absence of uniform imaging protocols and demographic diversity in datasets introduces biases that limit AI’s applicability across populations.

AI models often function as “black boxes,” providing results without clear explanations, which can erode clinician trust. The normal variability of fetal facial expressions complicates the interpretation of movement patterns, making it challenging to distinguish typical development from potential abnormalities (Figure 7) [1], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [[70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76]. Without established diagnostic benchmarks, both 4D ultrasound and AI algorithms risk inconsistency in identifying pathological conditions. Ethical concerns arise from early diagnoses, as incomplete information may lead parents to make difficult decisions prematurely. Despite these limitations, advances in 4D ultrasound enable detailed analysis of fetal behaviors like yawning and smiling, offering valuable insights into neurological development.

Early detection of neurological disorders, such as those affecting cranial or autonomic nerves, could improve outcomes through timely intervention. However, differentiating abnormal patterns from normal variation requires the development of clear diagnostic parameters. Environmental and genetic factors further complicate diagnosis, as conditions like Bell’s Palsy or Ramsay Hunt Syndrome have multifactorial origins. While fetal facial expressions cannot directly confirm viral infections or neuroinflammation, they can provide early clues for further investigation. Ensuring diagnostic validity will require extensive longitudinal studies to link observed in utero abnormalities to specific neurological disorders after birth.

Reliable diagnostic methods also depend on rigorous, multicenter validation studies to confirm the reproducibility and accuracy of these tools. Improved AI algorithms must be trained on diverse datasets to mitigate biases and enhance diagnostic precision. Standardized imaging protocols are essential to ensure uniformity in data collection and interpretation across clinical environments. Addressing these challenges will be critical to integrating 4D ultrasound and AI into routine prenatal care. These technologies, with further refinement, hold the potential to revolutionize fetal diagnostics and improve neonatal outcomes. By fostering collaborative research and developing ethical frameworks, clinicians can harness these tools to redefine maternal-fetal medicine. Through ongoing advancements, 4D ultrasound and AI offer the possibility of opening new frontiers in understanding human development [1], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [[70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76].

Advancing AI methodologies in fetal diagnostics

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with 4D ultrasound imaging has opened new horizons in the field of maternal-fetal medicine. AI enhances our ability to analyze fetal facial expressions, offering a non-invasive window into neurological and developmental health [1], 2], 15]. This section addresses the editor’s questions by exploring the neural networks and algorithms underpinning this innovation, their current limitations, and the potential for future advancements. By delving into these aspects, we aim to clarify how AI methodologies contribute to the diagnostic process and their implications for clinical practice.

Types of neural networks and algorithms in use

AI technologies rely on sophisticated neural networks tailored to process high-dimensional data from 4D ultrasound imaging [1], 2], 8]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel in identifying spatial features, such as facial structures and asymmetries, within fetal images [7], 8]. Meanwhile, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) models analyze temporal sequences, enabling the study of dynamic movements like blinking or smiling [2], 9], 19]. These algorithms can also work in synergy, combining spatial and temporal insights for comprehensive evaluations [15], 17]. By employing such advanced tools, clinicians can detect subtle deviations in fetal expressions that may indicate neurological or developmental abnormalities [2], 18], 21].

Current limitations in AI technologies

Despite their promise, AI applications in fetal diagnostics face several challenges. One significant limitation is the quality and diversity of available datasets [1], 8], 9]. Many training datasets lack the representation necessary to ensure generalizable models, introducing biases that can affect diagnostic accuracy [2], 18]. Temporal resolution is another issue, as capturing rapid fetal movements with current 4D ultrasound technology remains difficult [14], 19], 24]. Additionally, the opaque nature of many AI algorithms, often described as “black boxes,” creates barriers to trust and adoption in clinical settings [2], 3], 8]. The variability in imaging protocols across institutions further complicates efforts to standardize AI-based diagnostics [1], 16], 26].

Future opportunities and directions

Addressing these challenges will require focused research and innovation. Explainable AI (XAI) offers a potential solution, providing clear insights into the reasoning behind diagnostic outputs and fostering greater clinician trust [7], 9]. Advances in federated learning could mitigate data-related biases by training algorithms on diverse datasets while safeguarding patient privacy [2], 19]. Furthermore, developing standardized imaging protocols would enhance reproducibility and ensure consistent performance across clinical environments [18], 24], 26]. Ethical considerations must also be central to these efforts, ensuring equitable access to AI-driven technologies and protecting patient data [3], 7], 26].

Clinical implications and transformative potential

When optimized, AI methodologies hold immense potential to revolutionize fetal diagnostics. The ability to detect subtle abnormalities in utero could lead to earlier interventions for neurodevelopmental disorders, improving neonatal outcomes [15], 18], 20]. These innovations also empower clinicians with tools to counsel parents effectively, preparing families for potential challenges [2], 17], 21]. As technology evolves, the integration of AI with imaging modalities such as prenatal MRI promises an even more detailed understanding of fetal development, bridging technological advancements with compassionate, patient-centered care [1], 14], 25].

Future research opportunities in longitudinal studies and ethical considerations

Tracking thousands of fetuses from pregnancy to birth offers unprecedented opportunities to validate links between abnormal in utero facial expressions and neurological disorders (Figures 8–10). [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69]. Longitudinal studies, supported by advanced tools like prenatal MRI and AI-driven analysis, refine diagnostic methods by identifying subtle fetal anomalies with high precision. However, integrating these technologies into clinical practice presents challenges that must be addressed to ensure their effective and ethical use. A major concern in prenatal diagnostics is managing false positives, which can cause parental anxiety, unnecessary interventions, and increased healthcare costs. Conversely, false negatives risk missing critical diagnoses, delaying interventions, and leaving parents unprepared for potential postnatal challenges.

AI-driven analysis in 4D ultrasound offers transformative potential but is often criticized for its lack of transparency, which can erode trust among clinicians and parents. Developing interpretable AI algorithms is essential to foster confidence and ensure reliability in diagnostic outcomes (Figure 7). Privacy concerns further complicate the integration of AI, as the collection and storage of sensitive medical imaging data raise risks of breaches and unauthorized access. Implementing robust cybersecurity measures, such as encryption and secure data-sharing protocols, is critical to protect patient information, alongside clear and informed consent processes [1].

Equitable access to these technologies remains a significant issue, as disparities in healthcare resources risk widening gaps in maternal-fetal care. To ensure fairness, policies must promote access in underserved regions and provide comprehensive training for clinicians to maximize the accuracy and consistency of diagnostic results. Ethical counseling should accompany AI-driven prenatal diagnoses, helping parents make informed decisions without undue emotional distress. Multidisciplinary collaboration between clinicians, ethicists, and technologists is crucial to refine diagnostic benchmarks and mitigate biases in AI systems.

Standardized criteria are necessary to distinguish normal fetal behavioral variability from pathological markers, reducing misdiagnosis risks. Longitudinal studies linking prenatal observations to postnatal outcomes can validate diagnostic methods and improve early intervention strategies. Ethical oversight frameworks should guide the deployment of these technologies, balancing innovation with patient autonomy and equity. By addressing these challenges, prenatal diagnostics can revolutionize maternal-fetal medicine, enhancing early intervention and improving neonatal outcomes. With robust ethical and technical safeguards, these advancements promise to redefine standards of care and build trust in cutting-edge medical tools (Figure 11).

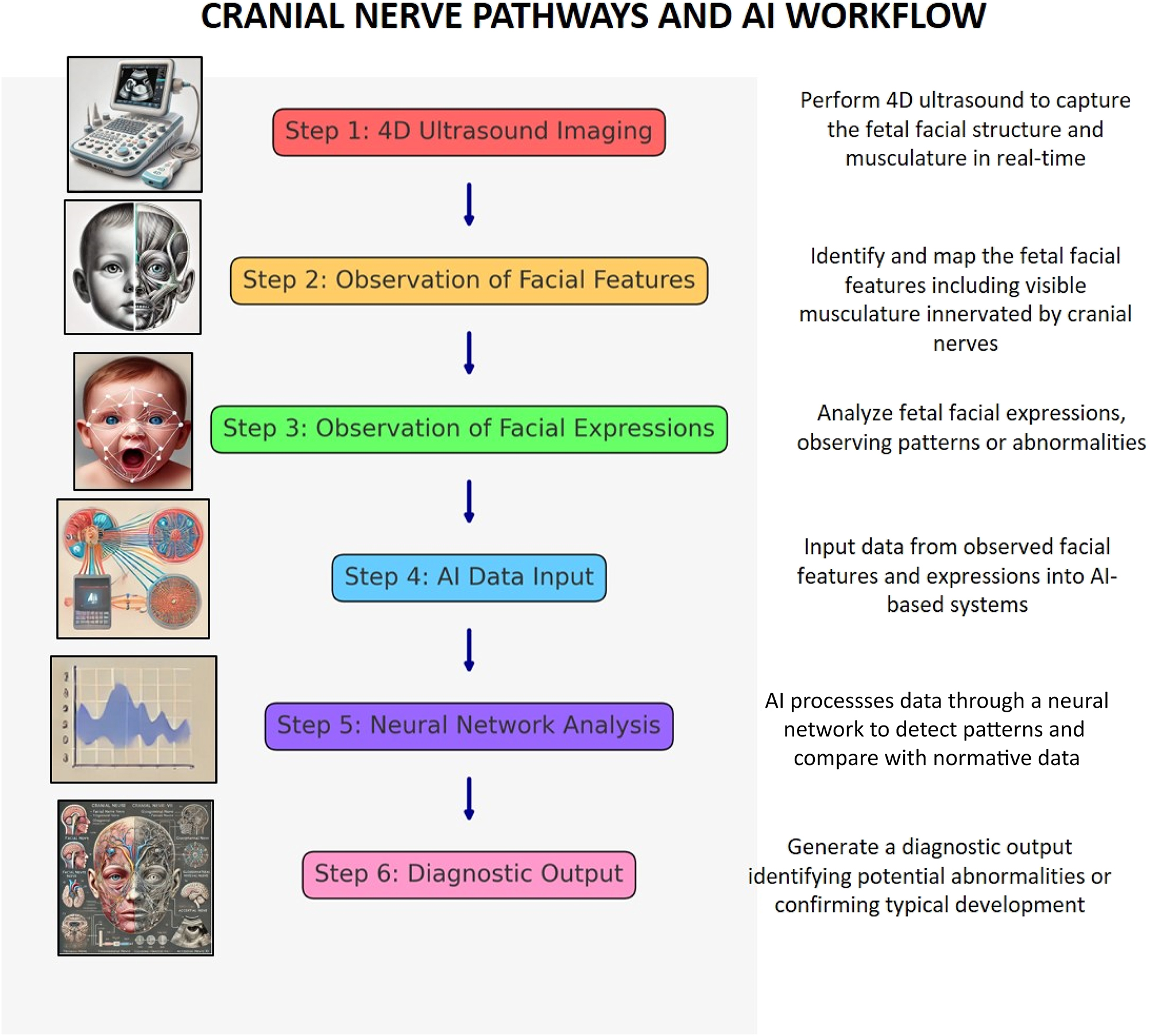

This flowchart illustrates the process of diagnosing abnormalities in fetal facial development using AI-assisted analysis. It begins with capturing 4D ultrasound images of the fetus, followed by observing and mapping facial features and expressions for patterns. The data is input into an AI system, which processes it using neural network analysis to detect deviations or confirm normal development. The process concludes with a diagnostic output identifying potential abnormalities or affirming typical facial musculature and expression development.

Conclusions

The study of fetal facial expressions through 4D ultrasound highlights its potential in diagnosing neurodevelopmental disorders, with longitudinal studies needed to link prenatal observations to postnatal outcomes. Multidisciplinary collaboration is critical to address challenges like false positives, ethical considerations, and equitable access to advanced diagnostics. Integrating AI with imaging modalities like prenatal MRI offers a more comprehensive assessment of fetal structural and functional development, improving diagnostic accuracy. However, AI systems must overcome issues of transparency, data bias, and interpretability to gain trust from clinicians and patients. Future research should focus on standardizing diagnostic benchmarks and developing diverse, high-quality datasets to enhance algorithm reliability and applicability. Ethical frameworks are essential to safeguard privacy, autonomy, and fairness, addressing concerns about the use and security of sensitive medical data. Longitudinal studies tracking outcomes over time will validate these innovations and ensure their clinical relevance. Combining AI, 4D ultrasound, and MRI marks a paradigm shift in prenatal care, enabling earlier and more accurate interventions. These advancements must balance innovation with ethical and equitable practices to avoid exacerbating healthcare disparities. Ultimately, this integrated approach will redefine maternal-fetal medicine, bridging technology with compassionate, patient-centered care.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the Indonesian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (POGI) and the Indonesian Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (HKFM) for encouraging and supporting the work of this review article.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Bachnas, MA, Andonotopo, W, Dewantiningrum, J, Pramono, MBA, Stanojevic, M, Kurjak, A. The utilization of artificial intelligence in enhancing 3D/4D ultrasound analysis of fetal facial profiles. J Perinat Med 2024;52:899–913. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2024-0347.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Medjedovic, E, Stanojevic, M, Jonuzovic-Prosic, S, Ribic, E, Begic, Z, Cerovac, A, et al.. Artificial intelligence as a new answer to old challenges in maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics. Technol Health Care 2024;32:1273–87. https://doi.org/10.3233/thc-231482.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Jaliaawala, MS, Khan, RA. Can autism be catered with artificial intelligence-assisted intervention technology? A comprehensive survey. Artif Intell Rev 2019;53:1039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-019-09686-8.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Cacaou, C, McGrouther, DA, Greenfield, BE, Hunt, N. Patterns of coordinated lower facial muscle function and their importance in facial reanimation. Br J Plast Surg 1996;49:274. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0007-1226(96)90155-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Burrows, AM. The facial expression musculature in primates and its evolutionary significance. BioEssays 2008;30:212. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.20719.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Waller, BM, Cray, JJ, Burrows, AM. Selection for universal facial emotion. Emotion 2008;8:435. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.435.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Chang, D, Yin, Y, Li, Z, Trần, M, Soleymani, MR. LibreFace: an open-source toolkit for deep facial expression analysis. WACV 2024;10:8190. https://doi.org/10.1109/wacv57701.2024.00802.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Jameel, R, Singhal, A, Bansal, A. A comprehensive study on facial expressions recognition techniques. In: Proceedings of the 6th international conference on cloud system and big data engineering (confluence). IEEE; 2016:524–28 pp. https://doi.org/10.1109/confluence.2016.7508167Suche in Google Scholar

9. Liong, S, See, J, Wong, K, Phan, RC-W. Less is more: micro-expression recognition from video using apex frame. Signal Process Image Commun 2017;62:82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.image.2017.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Costa-Abreu, MD, Bezerra, GS. FAMOS: a framework for investigating the use of face features to identify spontaneous emotions. Pattern Anal Appl 2017;22:683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10044-017-0675-y.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Stiles, J, Jernigan, TL. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol Rev 2010;20:327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Shirvaikar, MV, Paydarfar, D, Indic, P. Real-time video analysis to monitor neonatal medical condition. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng 2017;10223:102230. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2262905.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Cabon, S, Porée, F, Cuffel, G, Rosec, O, Geslin, F, Pladys, P, et al.. Voxyvi: a system for long-term audio and video acquisitions in neonatal intensive care units. Early Hum Dev 2021;153:105303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105303.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Vigliante, CE. Anatomy and functions of the muscles of facial expression. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2005;17:1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coms.2004.09.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Kurjak, A, Stanojevic, M, Andonotopo, W, Salihagic-Kadic, A, Carrera, JM, Azumendi, G. Behavioral pattern continuity from prenatal to postnatal life: a study by four-dimensional (4D) ultrasonography. J Perinat Med 2004;32:346–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2004.065.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Stanojevic, M, Perlman, J, Andonotopo, W, Kurjak, A. From fetal to neonatal behavioral status. Ultrasound Rev Obstet Gynecol 2004;4:59–71. https://doi.org/10.3109/14722240410001713939.Suche in Google Scholar