Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?

-

Iris Dressler-Steinbach

, Miriam Kinzel

To the Editor,

Trisomy 18, also known as Edward’s syndrome, is the second most common aneuploidy following trisomy 21. There are three types of Edward’s syndrome: Complete, partial, and mosaic trisomy 18. In mosaic trisomy 18, both a complete trisomy 18 and a normal cell line exist. Thus, the phenotype can range from complete trisomy 18 phenotype with early mortality to normal phenotype [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. In cases with mosaic trisomy 18, a significant discrepancy between the levels of mosaicism for trisomy 18 in different tissues, i.e. high-level mosaic trisomy 18 in blood lymphocytes but low-level mosaic trisomy 18 in skin fibroblasts, has been described [2], [3], [4]. However, no reports about tissue-specific genetic analyses and genotype-phenotype correlation have been reported for trisomy 18 mosaicism.

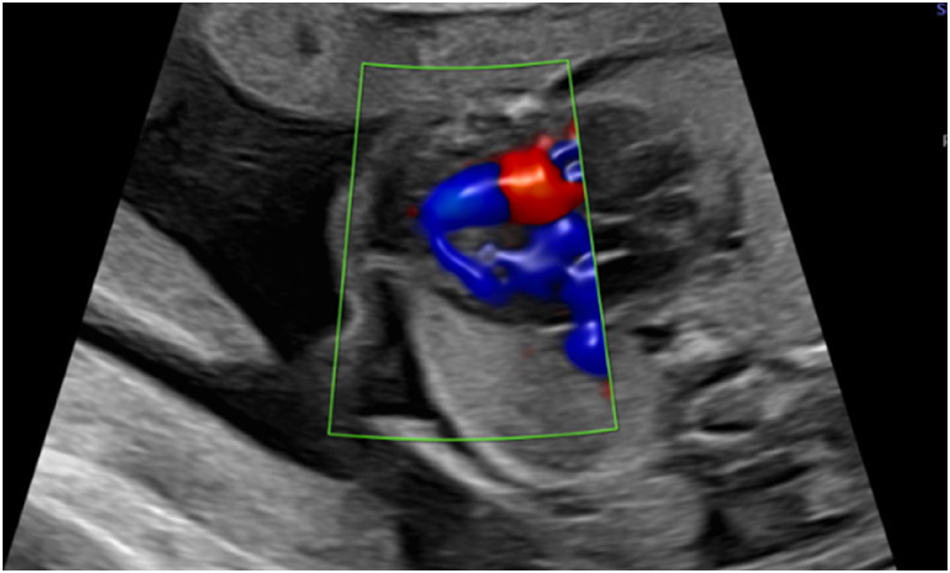

A 45-year-old woman presented for a first trimester scan with normal nuchal translucency (NT 1.77 mm) and normal sonoanatomy. The risk calculated for T18 was 1 in 4, based on low maternal serum ß-HCG and PAPP-A. NIPT was performed at mother’s request: the initial result was “the fetus is female, low risk for trisomy 18”. However, the second trimester ultrasound scan revealed a sex discrepancy. Invasive diagnostics were again recommended but declined. Repeat NIPT at 21 weeks showed a high risk of trisomy 18 and a male gonosomal constitution. In addition, a ventricular septal defect (VSD) (Figure 1), hypoplasia of the thymus and clenched fists (thumbs) were suspected at follow-up ultrasound. Amniocentesis finally confirmed a mosaic trisomy 18 with karyotype: mos47,XY,+18[22]/46,XY[18].

Apical ventricular septal defect in 26 weeks.

After counselling, the parents decided to continue the pregnancy and make full use of life-prolonging intensive care if needed.

Postnatal outcomes: A male infant was born by planned caesarean section at 39 1/7 weeks of gestation, with a birth weight of 2,540 g (1st percentile) and Apgar scores of 8/8/9. The umbilical artery pH was 7.24. On the first day of life, the infant required temporary respiratory support (nasal CPAP, max FiO2 0.4) due to wet lung disease. Postnatal echocardiography revealed a dysplastic aortic valve, an atrial septal defect (ASD) type II with atrial septal aneurysm, and a subaortic VSD extending into the inlet. The infant had no abnormalities other than the cardiac findings, which did not require immediate treatment. On day 5, the child could be discharged home.

At 4 months of age, the heart defect was corrected due to progressing heart failure on medication. Patch closure of the ASD and VSD and resection of the atrial septal aneurysm were performed. Samples for genetic analysis were taken during surgery. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Now 24 months old, the child’s neurocognitive development and motor function are normal, with no restriction of thumb movement or grasping. A plagiocephalus was corrected by helmet therapy. Since the heart surgery, the family reports that their son is in good health and attends a regular kindergarten.

Genetic analysis: Amniocytes and tissue samples from all three germ layers were analysed by conventional chromosome analysis and by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH). Mosaicism for a free trisomy 18 was detected in all analysed tissues. The results of the FISH analysis on interphase nuclei are presented in Table 1.

FISH results on interphase nuclei from various tissues in correlation to their origin/germ layer.

| Sample | Amniotic fluid | Heart tissue | Blood | Thymus | Skin | Buccal swap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of trisomy 18 cells | 28 % | 96 % | 10 % | 7 % | 5 % | 1 % |

| Origin | Ectodermal (skin) Endodermal (bladder) Extraembryonic amnion |

Mesodermal | Mesodermal | Endodermal | Ectodermal | Ectodermal (skin) Mesodermal (blood) |

The distribution of trisomy 18 cells varied considerably. While heart cells from the right ventricle showed 96 % trisomy 18 cells, the percentage in other tissues was much lower.

To the best of our knowledge, we document the first child with mosaic trisomy 18 with an organ/tissue-specific genetic analysis of genotype–phenotype correlation. Cytogenetic analyses diagnosed a high-level mosaic trisomy 18 of 96 % in heart muscle tissue, whereas in all other examined tissues a low-level mosaic between 1 and 10 % was detected.

The heart specific high-level mosaic perfectly matched with the phenotype of the child, who had no other than cardiac abnormalities, including a normal neurocognitive development up to 24 months of age. What are the potential implications of these findings for prenatal counselling in mosaic trisomy 18? Amniotic fluid contains fetal cells of ectodermal and endodermal origin, as well as cells derived from the extraembryonic amnion. Genetic analysis of amniotic fluid in mosaic trisomy 18 therefore cannot be organ specific. Accordingly, a classification of mosaicism in “low-grade” and “high grade” based on genetic analysis of amniotic fluid is of limited help in predicting the severity of specific pathology relevant to survival or quality-of-life or reducing morbidity [1]. Regarding craniofacial, skeletal, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary malformations prenatal high-resolution ultrasound examination has by far the greater potential to add significant information about the risk of postnatal malformation-associated morbidity and mortality.

Neither the level of mosaic trisomy 18 in amniotic fluid, nor the prenatal ultrasound can predict exactly the risk for postnatal neurocognitive impairment in long term survivors with mosaic trisomy 18. However, it is evident that the potential for neurological impairment is a key factor for parents when deciding whether to terminate a pregnancy [6]. Accordingly, this particular diagnostic gap remains a significant dilemma in the context of prenatal counselling. It seems reasonable to hypothesise that, in the case of mosaic trisomy 18, prenatal CNS (central nervous system)-specific genetic analysis has the potential to fill this diagnostic gap. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling during pregnancy is technically possible, but it is uncertain whether CSF or even a single brain tissue biopsy accurately represent the rest of the neural tissue.

A false negative NIPT with fetal sex discordance may be attributable to a number of potential causes [7]. The most plausible explanation for this case is that the initial NIPT analysis had an insufficient fetal fraction because a NIPT was performed without measuring the fetal fraction. In the present case, the analysis was likely limited to maternal cell-free DNA. A low fetal fraction is considered by some authors to be associated with trisomy 18 pregnancies [8], 9]. However, it is important to note that if the NIPT result had been correctly positive at 13 weeks, the couple would have subsequently terminated the pregnancy.

In conclusion, despite the important insights gained regarding the tissue-specific distribution of aneuploid cells in mosaic trisomy 18, there is currently no way to prenatally provide prognostically reliable information about the severity of morbidity, in particular of neurocognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the staff who advised and supported the couple and the neonate. These include, but are not limited to, our team for psychosocial counselling, obstetricians, midwifes and nurses, our neonatal palliative care team and the surgical team of the German Heart Centre of the Charité (DHZC). Finally, we would like to thank the family for allowing us to share their story.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians or wards of the individual included in this case report.

-

Author contributions: I.DS., M.S. and M.K. conceptualized the Case analysis. I.DS. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input of all co-authors. All co-authors read the final manuscript and made suggestions on its content. M.K., R.W., A.W2. and M.S. conducted the genetic analysis. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

1. Wallerstein, R, Yu, MT, Neu, RL, Benn, P, Lee Bowen, C, Crandall, B, et al.. Common trisomy mosaicism diagnosed in amniocytes involving chromosomes 13, 18, 20 and 21: karyotype-phenotype correlations. Prenat Diagn 2000;20:103–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(200002)20:2<103::aid-pd761>3.3.co;2-b.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(200002)20:2<103::AID-PD761>3.3.CO;2-BSearch in Google Scholar

2. Banka, S, Metcalfe, K, Clayton-Smith, J. Trisomy 18 mosaicism: report of two cases. World J Pediatr 2013;9:179–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-011-0280-x.Search in Google Scholar

3. Tucker, ME, Garringer, HJ, Weaver, DD. Phenotypic spectrum of mosaic trisomy 18: two new patients, a literature review, and counseling issues. Am J Med Genet A 2007;143A:505–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.31535.Search in Google Scholar

4. Fitas, AL, Paiva, M, Cordeiro, AI, Nunes, L, Cordeiro-Ferreira, G. Mosaic trisomy 18 in a five-month-old infant. Case Rep Pediatr 2013;2013:929861. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/929861.Search in Google Scholar

5. Bettio, D, Levi Setti, P, Bianchi, P, Grazioli, V. Trisomy 18 mosaicism in a woman with normal intelligence. Am J Med Genet A 2003;120A:303–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.20213.Search in Google Scholar

6. Lou, S, Carstensen, K, Petersen, OB, Nielsen, CP, Hvidman, L, Lanther, MR, et al.. Termination of pregnancy following a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: a qualitative study of the decision-making process of pregnant couples. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:1228–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13386.Search in Google Scholar

7. Smet, ME, Scott, FP, McLennan, AC. Discordant fetal sex on NIPT and ultrasound. Prenat Diagn 2020;40:1353–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5676.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sheehan, E, Bacon, V, Lascurain, S, Stone, J, Yatsenko, S, Aarabi, M, et al.. Prenatal and fetal diagnosis of trisomy 18 after low-risk cell-free fetal DNA screening: a report of four cases. Prenat Diagn 2023;43:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.6273.Search in Google Scholar

9. Becking, EC, Schuit, E, van Baar de Knegt, SME, Sistermans, EA, Henneman, L, Bekker, MN, et al.. Association between low fetal fraction in cell-free DNA screening and fetal chromosomal aberrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenat Diagn 2023;43:838–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.6366.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?