Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

-

Sabine K. Maschke

Abstract

Objectives

Planning the mode of delivery of a full-term breech singleton remains a challenging task. The aim of this work is to compare the neonatal and maternal short-term outcomes after planned vaginal delivery and caesarean section and to evaluate the influence of an MRI pelvimetry on the short-term outcomes in order to provide appropriate advice to pregnant women with breech presentation.

Methods

This is a retrospective monocentric analysis of all deliveries with singleton pregnancies from breech presentation >36 + 0 weeks of gestation between 08/2021 and 09/2023. Short-term maternal and neonatal morbidity data were collected for intended vaginal deliveries and caesarean sections. Neonatal and maternal short-term outcomes of intended vaginal deliveries with and without MRI pelvimetry were compared.

Results

In the planned vaginal delivery group, APGAR scores and arterial umbilical cord pH were significantly lower than in the planned caesarean group. The rate of asphyxia was similar in both groups. Although not significant, the rate of NICU admission was higher in the vaginal birth group (6.7 % vs. 2.7 %; p=0.27), and infants born by caesarean remained in the NICU longer (1.3 % vs. 1.8 %; p=1.0). Neonates born to women who underwent MRI prior to attempted vaginal delivery had better short-term neonatal outcomes and shorter NICU stays compared with women who did not undergo MRI, after multivariate analysis for fetal birth weight, parity, and gestational age.

Conclusions

Vaginal breech delivery is associated with lower APGAR scores and umbilical arterial pH compared with caesarean section but does not result in increased neonatal asphyxia or NICU admission. Length of stay in the NICU is shorter when a newborn is admitted after vaginal delivery. MRI pelvimetry may improve the outcome of the newborn by further selection.

Introduction

Approximately 3–4 % of all singleton pregnancies present as breech at term [1]. For years, the mode of delivery of singleton breech newborns at term has been discussed controversial with regard to perinatal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Since the publication of the Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group, the debate on mode of delivery has been revived [2]. However, due to the methodological concerns of the study, the recommendation for primary caesarean section as the favored mode of delivery should not be followed as a general standard, although several national specialist societies have adopted the recommendations of the Term Breech Trial [3], [4], [5].

The current German guideline recommends that pregnant women with breech presentation should be informed that there is currently no preferred mode of delivery and that individual birth mode planning must take place [6]. After several years of recommending caesarean section as the mode of delivery, most other national guidelines do not recommend caesarean section and state that a vaginal delivery is a safe option [3], [6], [7], [8].

The rate of primary caesarean section has recently increased at the expense of attempted vaginal delivery [6]. The prevalence of short- and long-term complications such as hemorrhage, uterine rupture and abnormal placentation is increasing in parallel with the increasing rate of caesarean section [9], [10], [11]. Elective caesarean sections without a justified medical indication should therefore be restricted. To achieve this goal, obstetricians need evidence-based recommendations to guide the most appropriate mode of delivery for each individual patient.

A review of the current literature reveals that the outcomes of perinatal and neonatal morbidity and mortality are mainly dependent on strict collective selection, the qualifications of the obstetric team and the available medical infrastructure available [12], [13], [14], [15]. If these factors are considered, the risk of a worse outcome for mother and child can be reduced to the level of vaginal birth from cephalic presentation [16], [17], [18].

The aim, therefore, is to identify a group of women who do not fulfill certain risk factors and who would benefit from a spontaneous birth. In addition to classic diagnostic tools such as fetometry, Doppler and anamnesis, MRI pelvimetry could be a useful tool. This imaging technique measures maternal pelvimetry and fetal head circumference to further assess the likelihood of a successful vaginal delivery.

The aim of our work is to compare the neonatal and maternal short-term outcomes after planned caesarean section and planned vaginal birth and to evaluate the influence of an MRI of the maternal pelvis on the outcome to be able to provide appropriate advice to pregnant women with breech presentation. In addition, the disclosure of our results should help to improve the overall evidence base for selecting of the most promising mode of delivery based on individual risk stratification.

Materials and methods

Data collection and patient selection

A retrospective observational study was performed. Between 08/2021 and 09/2023 anamnestic and clinical parameters as well as neonatal and maternal short-term outcome parameters were collected from singleton pregnancies expecting breech newborns that were delivered at the Hanover Medical School, Germany.

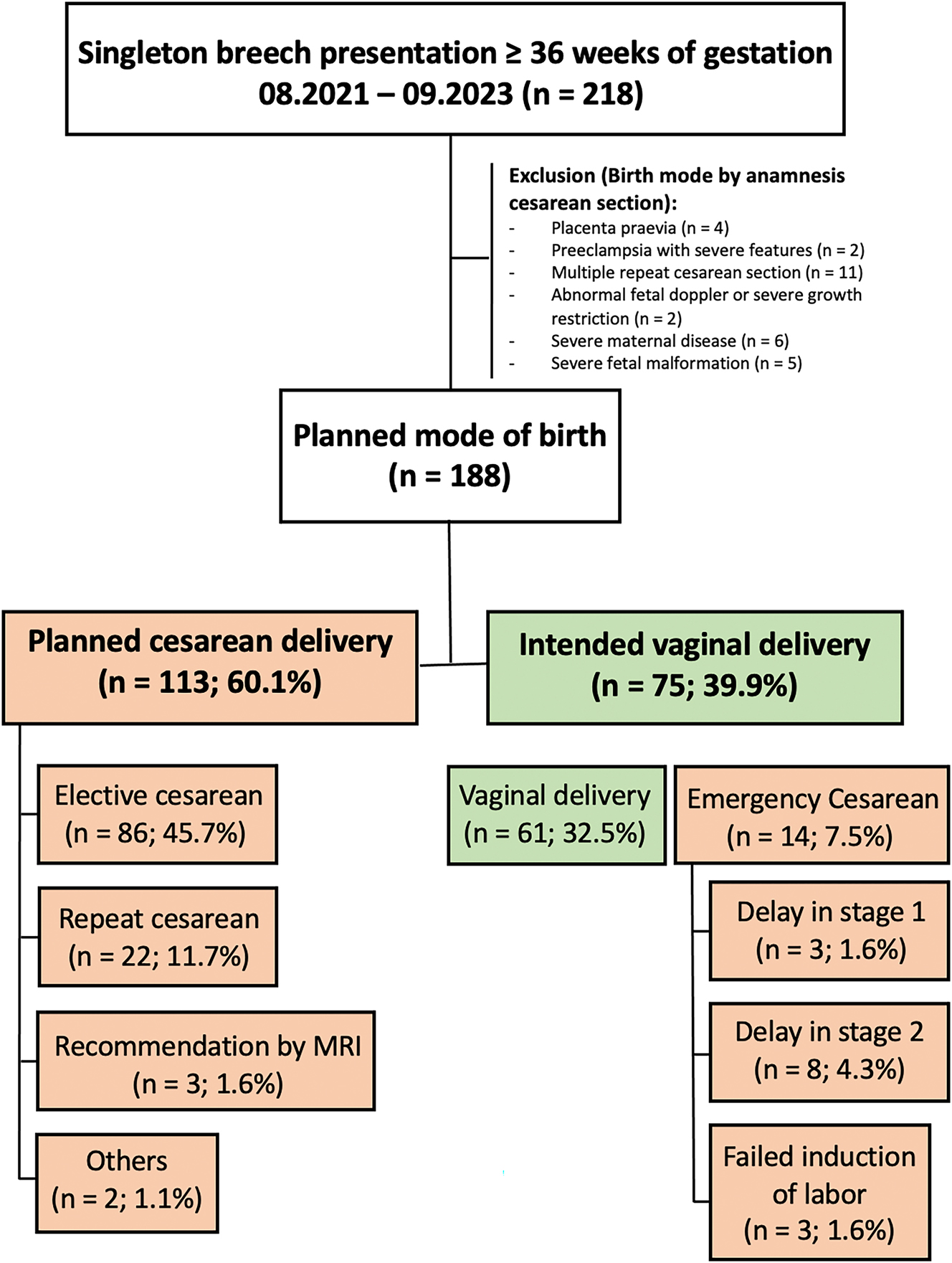

Data were extracted from hospitals patient management system after discharge. Data were accessed for research purposes in 10/2023. Healthy women with uncomplicated singleton breech pregnancies who were able to choose a mode of delivery after informed consent were included. Exclusion criteria were planned caesarean section on recommendation (placenta praevia, pre-eclampsia with severe features, multiple repeat caesarean section (more than one caesarean section in history), abnormal fetal Doppler or severe growth restriction, severe maternal illness, severe fetal malformation). A flow chart showing the study design and number of cases included is shown in Figure 1.

Flow chart representing study design and numbers of cases included in the study.

Patients were managed as usual. After examination and sonographic fetometry, the different options for mode of delivery were presented. The risks and complications of vaginal delivery and caesarean section were explained in detail. The possibility and success rate of an external version was also explained, based on current literature and the hospital’s experience. MRI pelvimetry was offered to all pregnant women who did not immediately opt for caesarean section after discussion of the options. It was performed from 36 + 0 weeks of gestation. The women were informed about MRI as a non-invasive cross-sectional imaging technique with no radiation exposure that does not compromise the safety of the fetus or the mother [19]. It was recommended for primiparous women, but was not essential for attempting a vaginal birth.

To assess the likelihood of vaginal delivery using MRI pelvimetry, the obstetric conjugate, intertubal distance and pubic angle were compared with those in the literature and our own clinical experience to date. It was pointed out that MRI pelvimetry can provide additional information, but only in conjunction with other criteria such as fetometry, fetomaternal Doppler and the pregnant woman’s medical history. After discussion of MRI pelvimetry, a vaginal trial of labour or caesarean section was planned.

MRI

All patients underwent MRI at 1.5T (Avanto, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). The American College of Radiology recommendations for safe and optimal performance of fetal MRI were followed [19]. Axial true fast imaging with steady-state free precession sequence with 3 mm slice thickness of the maternal pelvis, axial T1-weighted turbo spin echo sequence with 3 mm slice thickness of the maternal upper abdomen/fetal head, sagittal T2-weighted half-acquisition single-shot turbo spin echo with 5 mm slice thickness of the whole maternal abdomen and coronal T1-weighted turbo spin echo sequence with 3 mm slice thickness of the whole maternal abdomen were acquired. The entire MRI scan took approximately 15 min. All patients were attended by a radiologist and a radiographer before, during and after the examination.

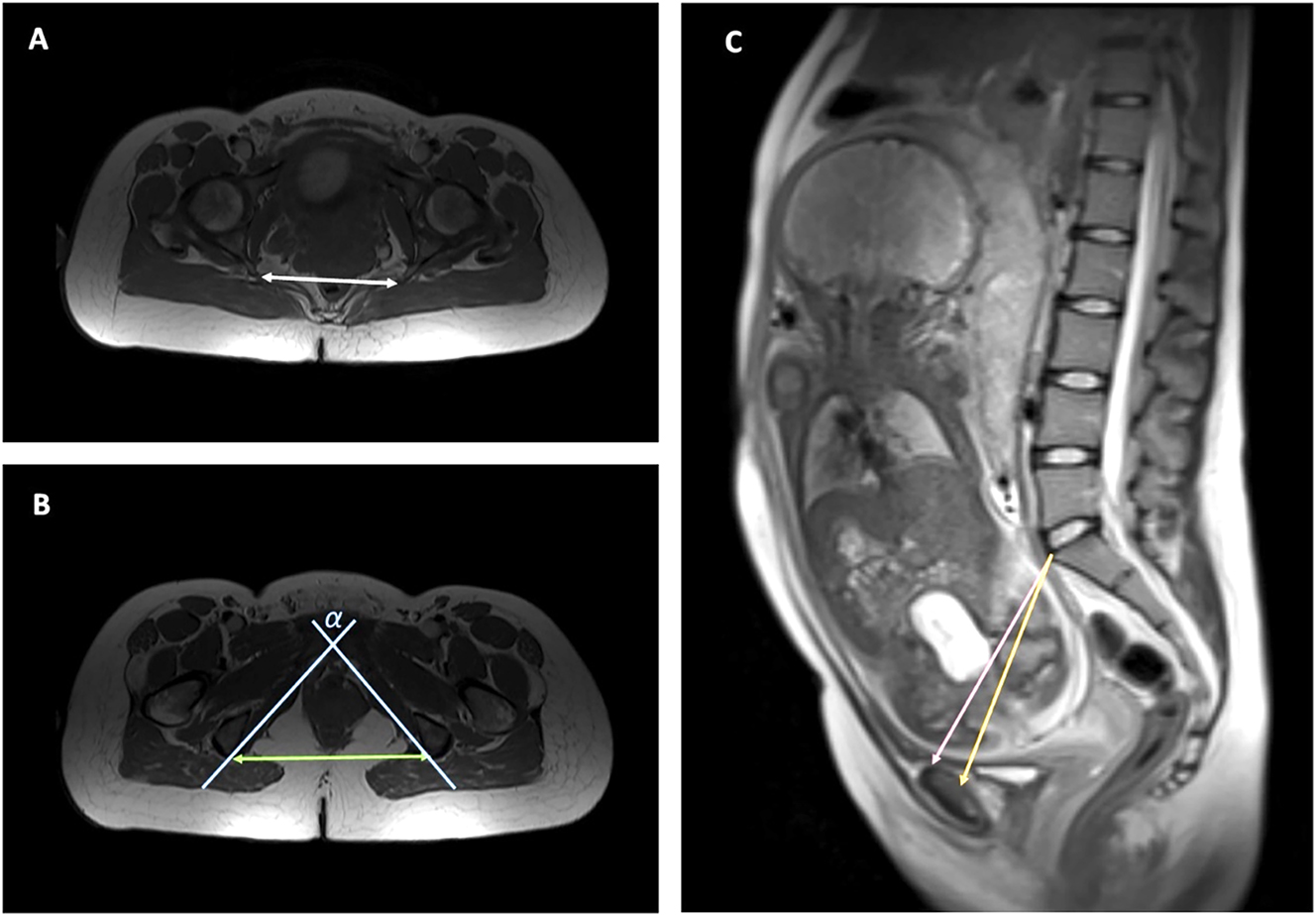

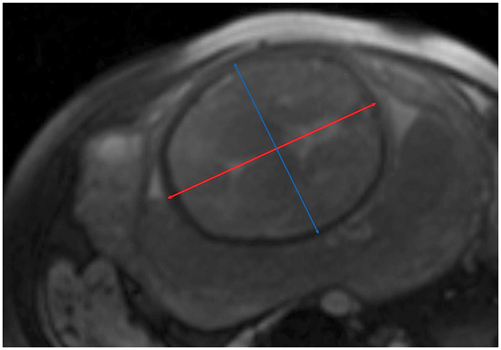

Intertubal distance, pubic angle, obstetric and true conjugate, and fetal biparietal and occipitofrontal diameters were measured by an experienced radiologist (8 years experience in urogenital imaging) (see Figures 2 and 3). The type of breech, e.g. complete, incomplete or Frank breech, was described as well as placental position and possible maternal pathologies. In addition, all studies were reviewed by a consultant paediatric radiologist.

Axial and sagittal measurements of the maternal pelvis. (A) Axial view of the maternal pelvis, measurement of interspinous distance (white double arrow), (B) axial view of the maternal pelvis, measurement of intertuberous distance (green double arrow) and pubic angle (α) (blue lines), (C) measurement of obstetrical (pink) and true conjugate (orange).

Fetometry of the head. Axial view of the fetal head, measurement of biparietal (blue double arrow) and occipitofrontal diameter (red double arrow) at the level of the thalami and cavum septi pellucidi.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism nine software (GraphPad Software Inc.) and IBM SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM SPSS Software). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to test the normal distribution of the epidemiological data. Unpaired t-test and Mann-Whitney test were used as appropriate. Group differences in rates determining neonatal or maternal outcome were tested in univariate contingency table-based statistics using Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. The influence of fetal birth weight, fetal head circumference at birth, gestational age at delivery and parity on outcome variables and the likelihood of spontaneous delivery in the group with and without MRI pelvimetry was tested using multivariate and univariate logistic regression analysis.

Ethics

This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Hannover Medical School and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (approval number: 10629_BO_K_2022). Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee due to the use of retrospective and de-identified data.

Results

During the 24 months studied, 218 patients presented with breech presentation. 30 patients were excluded on recommendation for planned caesarean section. 188 patients had the opportunity to choose a mode of delivery after informed consent. A total of 113 patients had a planned caesarean section (60.1 %), and 75 patients had a planned vaginal delivery (39.9 %) (Figure 1).

Two groups were created according to planned caesarean section (PCD) and intended vaginal delivery (IVD). Mean maternal age (PCD: 32.8 years, IVD: 31.7 years), body mass index (BMI) at the beginning of pregnancy (PCD: 24.7 kg/m2, IVD: 25.5 kg/m2) and fetal birth weight (PCD: 3370 g, IVD: 3265 g) were not significantly different between the groups. Gestational age at delivery was significantly different between planned caesarean section and planned vaginal delivery (PCD: 38.7, IVD: 39.1). There was no significant difference in maternal length of hospital stay (PCD: 3.8 days, IVD: 3.7 days), while mean blood loss was slightly but significantly higher in the planned caesarean group (PCD: 319 mL, IVD: 282 mL) (Table 1).

Vaginally deliveries and cesarean deliveries out of breech position ≥36 weeks of gestation. Neonatal and maternal short-term outcome.

|

Characteristics

|

Planned cesarean delivery | Intended vaginal delivery |

p-Value

|

|

(n=113)

|

(n=75)

|

||

| Maternal characteristics and outcome | |||

| Age, years (mean; st.dev.) | 32.8 ± 5.4 | 31.7 ± 4.2 | 0.13 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean; st.dev.) | 24.7 ± 5.0 | 25.5 ± 6.6 | 0.73 |

| Gestational age at delivery, years (mean; st.dev.) | 38.71 ± 0.9 | 39.14 ± 0.9 | 0.001 |

| Days until discharge (mean; st. dev.) | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 0.2 |

| Loss of blood, mL (mean; st.dev.) | 319 ± 60 | 282 ± 80 | 0.001 |

| Neonatal characteristics and outcome | |||

| Fetal weight, gram (mean; st.dev.) | 3,378 ± 457 | 3,265 ± 423 | 0.09 |

| APGAR 1′ (mean; st.dev.) | 8.97 ± 0.4 | 8.08 ± 1.8 | 0.001 |

| APGAR 5′ (mean; st.dev) | 9.89 ± 0.5 | 9.36 ± 1.2 | 0.001 |

| APGAR 5′<4, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (1.3 %) | 0.4 |

| APGAR 5′4<7, n (%) | 1 (0.9 %) | 1 (1.3 %) | 1.0 |

| APGAR 10′ (mean; st.dev.) | 9.97 ± 0.2 | 9.76 ± 0.6 | 0.001 |

| pH arterial cord blood (mean; st.dev.) | 7.29 ± 0.04 | 7.22 ± 0.09 | 0.001 |

| Perinatal asphyxia (pH arterial blood <7.0, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1.0 |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 3 (2.7 %) | 5 (6.7 %) | 0.27 |

| >4 days | 2 (1.8 %) | 1 (1.3 %) | 1.0 |

| Up to 4 days | 1 (0.9 %) | 4 (5.3 %) | 0.08 |

| Days until discharge (mean; st. dev.) | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 0.63 |

-

Bold values represent p-value <0.05 and therefore statistically significant difference.

The comparison of the neonatal outcome parameters between the planned caesarean delivery group and the intended vaginal delivery group revealed significantly lower values for neonates of intended vaginal delivery group regarding APGAR 1, 5 and 10 min and arterial cord blood pH (PCD: 7.29, IVD: 7.22). There were no cases of perinatal asphyxia with arterial cord blood pH below 7.0 in either group.

Although not statistically significant, the rate of NICU admission was higher in planned vaginal delivery group. The rate of NICU stay longer than four days was higher in the planned caesarean delivery group, but not significantly different. There was no difference in days to discharge (Table 1).

Comparing the characteristics of women with and without performed MRI and planned vaginal delivery, there was no difference in age, BMI or medical conditions. The duration of pregnancy was significantly longer in the MRI group (MRI: 39.44 weeks, no MRI: 38.39 weeks). There were significantly more primiparous women in the MRI group (MRI: 81.1 %, noMRI: 31.8 %; p=0.001), second (MRI: 18.9 %, noMRI: 50 %, p=0.01) and multiparous women (MRI: 0 %, noMRI: 18.2 %; p=0.006) were mainly found in the non-MRI group, whereas the type of breech presentation did not differ significantly between the two groups. The primary maternal delivery position was the dorsal position in both groups, MRI (62.3 %) and non-MRI group (72.7 %), whereas the upright position was less common in MRI (15.1 %) and non-MRI group (18.2 %). There were various reasons for caesarean section. The distribution of reasons for this mode of delivery was not significantly different between the groups (Table 2).

Vaginally intended deliveries out of breech position ≥36 weeks of gestation. Epidemiologics and maternal patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | MRI performed (n=53) | MRI not performed (n=22) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean; st.dev.) | 31.6 ± 4.1 | 32.1 ± 4.5 | 0.67 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean; st.dev.) | 23.3 ± 3.7 | 26.1 ± 7.8 | 0.17 |

| Gestational age at delivery, years (mean; st.dev.) | 39.44 ± 0.7 | 38.39 ± 1.0 | 0.001 |

| Internal preconditions, n (%) | 6 (11.3 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.44 |

| Parity, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 43 (81.1 %) | 7 (31.8 %) | 0.001 |

| 2 | 10 (18.9 %) | 11 (50 %) | 0.01 |

| >2 | 0 (0 %) | 4 (18.2 %) | 0.006 |

| Type of breech, n (%) | |||

| Frank | 43 (81.1 %) | 20 (90.9 %) | |

| Complete | 6 (11.3 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | |

| Incomplete | 4 (7.6 %) | 0 (0 %) | |

| Maternal birth position, n (%) | |||

| Dorsal position | 33 (62.3 %) | 16 (72.7 %) | 0.39 |

| Upright position | 8 (15.1 %) | 4 (18.2 %) | 0.39 |

| Reason for cesarean (n=14) n (% of cesarean) |

12 (22.6 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.21 |

| Delay in stage 1 | 2 (16.7 %) | 1 (50 %) | 0.28 |

| Delay in stage 2 | 7 (58.3 %) | 1 (50 %) | 0.39 |

| Failed induction of labor | 3 (25 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.32 |

| Abnormal fetal cardiography | 7 (58.3 %) | 2 (100 %) | 0.27 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 1 (8.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.37 |

-

Bold values represent p-value <0.05 and therefore statistically significant difference.

Table 3 shows the neonatal outcome of intended vaginal births out of breech presentation in pregnant women who received MR pelvimetry or not. The mean fetal weight was significantly higher in the group of women who received MR pelvimetry (MR: 3,353 g, no MR: 3,053 g; p=0.004). The APGAR scores at 1, 5 and 10 min were not significantly different. The same was found for arterial umbilical pH. Severe asphyxia was not observed in either group. Although not statistically significant, fewer infants in the MR pelvimetry group were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (MRI: 5.7 %, noMRI: 9.1 %; p=0.63). The neonates in the MRI group who were transferred to the NICU were discharged more quickly, but not significantly different. Overall, the length of stay was shorter for the children in the MRI group (MRI: 3.4 days, noMRI: 4.1 days; p=0.07). Fewer maneuvers were needed to deliver the newborns in the non-MRI group, except for the Bracht maneuver not significantly different.

Vaginally intended deliveries out of breech position ≥36 weeks of gestation. Neonatal outcome.

| Characteristics | MRI performed (n=53) | MRI not performed (n=22) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal weight, gram (mean; st.dev.) | 3,353 ± 376 | 3,053 ± 462 | 0.004 |

| APGAR 1′ (mean; st.dev.) | 8.19 ± 1.5 | 7.82 ± 2.4 | 0.9 |

| APGAR 5′ (mean; st.dev) | 9.45 ± 0.9 | 9.14 ± 1.7 | 0.9 |

| APGAR 5′<4, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.29 |

| APGAR 5′4<7, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.29 |

| APGAR 10′ (mean; st.dev.) | 9.83 ± 0.4 | 9.59 ± 0.9 | 0.36 |

| pH arterial cord blood (mean; st.dev.) | 7.21 ± 0.09 | 7.24 ± 0.08 | 0.19 |

| Perinatal asphyxia (pH arterial blood <7.0, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1.0 |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 3 (5.7 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.63 |

| >4 days | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.29 |

| Up to 4 days | 3 (5.7 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 1.0 |

| Days until discharge (mean; st. dev.) | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 2.8 | 0.07 |

| Birth trauma, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.29 |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1.0 |

| Maneuvers necessary, n (%) | |||

| Bracht | 17 (32.1 %) | 3 (13.6 %) | 0.04 |

| Veith Smellie | 3 (5.7 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.37 |

| Mueller | 6 (11.3 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.34 |

| Loveset | 10 (18.9 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.06 |

| Bickenbach | 2 (3.8 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.39 |

| Frank Nudge | 1 (1.9 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.3 |

-

Bold values represent p-value <0.05 and therefore statistically significant difference.

In terms of maternal outcomes, there was no significant difference in the incidence of birth injuries between the two groups. Major birth injuries were less frequent in the MRI group (MRI: 1.9 %, noMRI: 4.5 %, p=0.34), although significantly more episiotomies were performed (MRI: 34 %, noMRI: 9.1 %; p=0.01). Maternal hospital stay was not different in the two groups (Table 4).

Vaginally intended deliveries out of breech position ≥36 weeks of gestation. Maternal outcome.

| Characteristics | MRI performed (n=53) | MRI not performed (n=22) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of blood (mean; st.dev.) | 292 ± 81 | 261 ± 75 | 0.03 |

| Perineal injury, n (%) | |||

| 1st′ perineal tear | 5 (9.4 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.26 |

| 2nd′ perineal tear | 3 (5.7 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.37 |

| 3rd′ and 4th′ perineal tear | 1 (1.9 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.34 |

| Episiotomies | 18 (34 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.01 |

| PDA during birth, n (%) | 8 (15.1 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.003 |

| Days until discharge (mean; st. dev.) | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 4.1 ± 2.8 | 0.87 |

-

Bold values represent p-value <0.05 and therefore statistically significant difference.

A multivariate analysis of the cohort of intended vaginal deliveries (MRI and non-MRI performers) including fetal birth weight, parity and gestational age was performed to eliminate the effect of these confounders on maternal and neonatal outcome parameters. A statistically significant better outcome of 5 min APGAR less than 4 (MRI: 0 %, noMRI: 4.5 %; p=0.014) and less frequently NICU stay after admission (MRI: 0 %, noMRI: 4.5 %; p=0.01) was observed in the MRI group. After multivariate regression analysis, there was no significant difference in the maneuvers performed for neonatal development. The rate of episiotomies was still significantly higher in the MRI group, whereas the rate of stage 1 delay and the occurrence of a pathological CTG were significantly higher in the non-MRI group (Table 5).

Vaginally intended deliveries out of breech position ≥36 weeks of gestation. Neonatal outcome. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for fetal birth weight, parity and gestational age.

| Characteristics | MRI performed (n=53) | MRI not performed (n=22) | p-Value (multivariate logistic regression analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| APGAR 1′ (mean; st.dev.) | 8.19 ± 1.5 | 7.82 ± 2.4 | 0.81 |

| APGAR 5′ (mean; st.dev) | 9.45 ± 0.9 | 9.14 ± 1.7 | 0.83 |

| APGAR 5′<4, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.014 |

| APGAR 5′4<7, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.91 |

| APGAR 10′ (mean; st.dev.) | 9.83 ± 0.4 | 9.59 ± 0.9 | 0.25 |

| pH arterial cord blood (mean; st.dev.) | 7.21 ± 0.09 | 7.24 ± 0.08 | 0.56 |

| Perinatal asphyxia (pH arterial blood <7.0, n (%) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1.0 |

| NICU admission, n (%) | 3 (5.7 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.39 |

| >4 days | 0 (0 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.01 |

| Up to 4 days | 3 (5.7 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.55 |

| Maneuvers necessary, n (%) | |||

| Bracht | 17 (32.1 %) | 3 (13.6 %) | 0.08 |

| Veith Smellie | 3 (5.7 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.98 |

| Mueller | 6 (11.3 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.61 |

| Loveset | 10 (18.9 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.05 |

| Bickenbach | 2 (3.8 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.71 |

| Frank Nudge | 1 (1.9 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.81 |

| Maternal birth position, n (%) | |||

| Dorsal position | 33 (62.3 %) | 16 (72.7 %) | 0.46 |

| Upright position | 8 (15.1 %) | 4 (18.2 %) | 0.46 |

| Reason for cesarean (n=14) n (% of cesarean) |

12 (22.6 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.1 |

| Delay in stage 1 | 2 (16.7 %) | 1 (50 %) | 0.03 |

| Delay in stage 2 | 7 (58.3 %) | 1 (50 %) | 0.11 |

| Failed induction of labor | 3 (25 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.03 |

| Abnormal fetal cardiography | 7 (58.3 %) | 2 (100 %) | 0.01 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 1 (8.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0.07 |

| Loss of blood (mean; st.dev.) | 292 ± 81 | 261 ± 75 | 0.95 |

| Perineal injury, n (%) | |||

| 1st′ perineal tear | 5 (9.4 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 0.88 |

| 2nd′ perineal tear | 3 (5.7 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.77 |

| 3rd′ and 4th′ perineal tear | 1 (1.9 %) | 1 (4.5 %) | 1.0 |

| Episiotomies | 18 (34 %) | 2 (9.1 %) | 0.01 |

-

Bold values represent p-value <0.05 and therefore statistically significant difference.

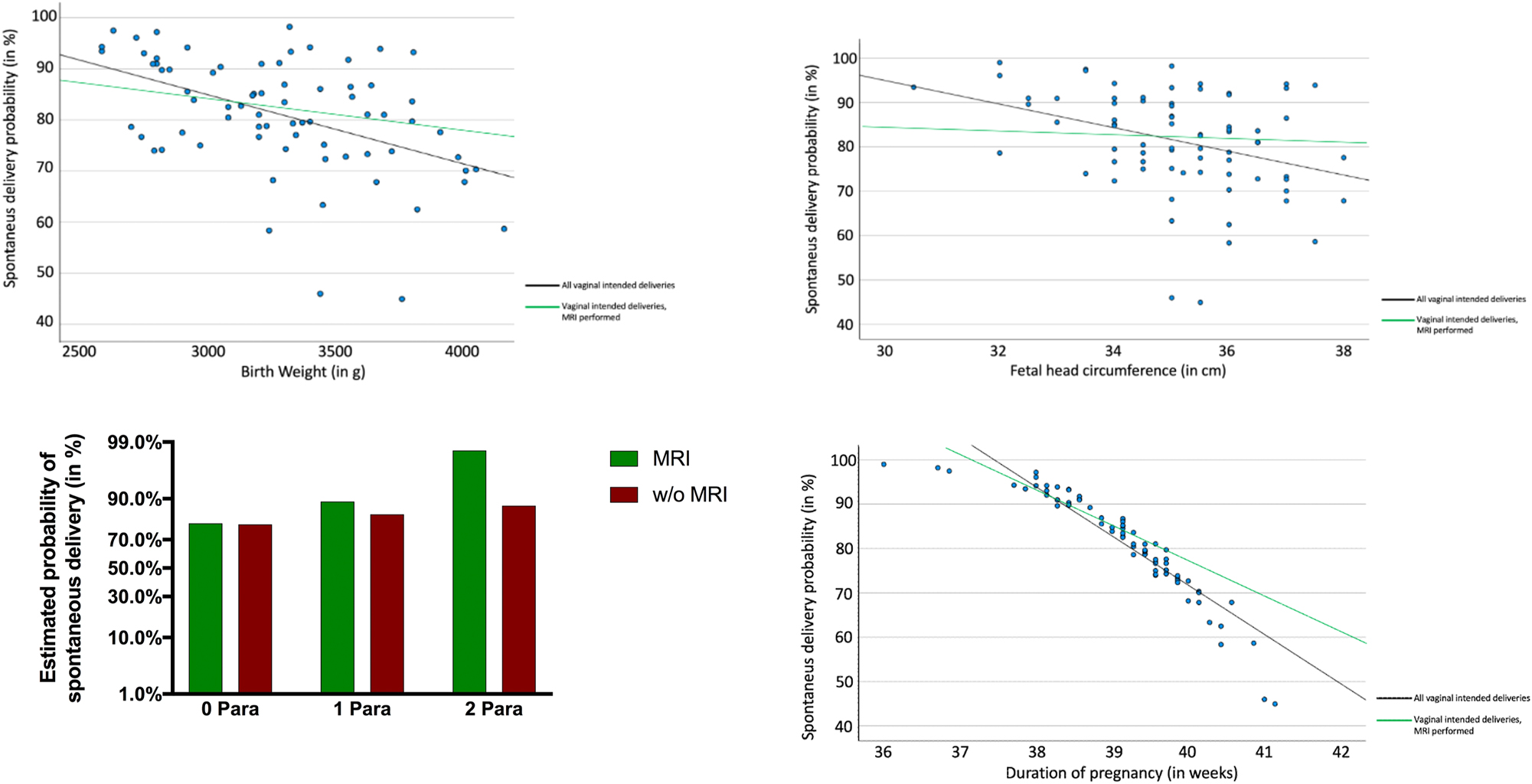

Logistic regression analysis was performed on all planned vaginal breech deliveries and vaginal births for birth weight, fetal head circumference, parity and gestational age to percentage of vaginally birth probability (Figure 4).

Logistic regression of birth weight, fetal head circumference, parity and duration of pregnancy to spontaneus delivery probability. All vaginal intended deliveries included. Y axis displays probability to delivery vaginally. X axis shows examined factors.

Discussion

The obstetric management and counselling of a pregnant woman with breech presentation at term remains a challenge. This is mainly due to the inconsistent recommendations in the literature and the different advice given in international guidelines. It is essential that the pregnant woman receives individual counselling. In addition to clinical and medical factors, the wishes and needs of the pregnant woman must be considered. The decision-making process should be patient-centred, individualised and consider the patient’s current circumstances, after discussing the benefits and risks of the available treatment options. The patient’s values and priorities play an important role [20]. In our collective of 188 pregnant women, 39.9 % attempted spontaneous delivery, while 60.1 % opted for primary caesarean section after shared decision making.

Of the pregnant women in the intended vaginal delivery group, 61 (81.3 %) gave birth spontaneously and 14 (18.7 %) required a caesarean section. The rate of aborted vaginal breech deliveries (14.1 %) was significantly lower in our study than in the term breech group (43.9 %) [2]. Possible reasons for this could be a better selection of a suitable group. In the breech trial, there was a large inter-institutional variation in the standard of care, inadequate methods of antepartum and intrapartum fetal assessment were used, and a large proportion of women were recruited during active labor.

In our study, most women delivered in the dorsal position. There was no significant difference in maternal position between the MRI and non-MRI groups (dorsal position: 62.3% and 72.7 %; p=0.39). Traditional maneuvers in the dorsal position were controlled by the obstetricians and practised regularly. When necessary, most obstetricians preferred to support the newborn’s development in the classic dorsal position, as they had more experience with it. This may explain the high rate of dorsal deliveries in our collective, although there is good evidence that vaginal breech delivery in the upright position is associated with a significantly reduced length of the second stage, caesarean section rate, and incidence of neonatal injury and manipulation to extract the neonate, compared with vaginal breech delivery in the dorsal position [21], [22], [23]. Louwen et al. described new cardinal movements of the descending breech and maneuvers to rectify problems [21]. Since vaginal breech deliveries have increased significantly in our clinic in recent years, it is possible that the obstetricians are in the process of learning the new maneuvers that were being developed for upright delivery. It can be assumed that the rate of spontaneous breech deliveries will shift in favour of the upright position in the future, as the necessary maneuvers become more familiar.

The planned vaginal birth group had significantly lower 1, 5 and 10 min APGAR scores and lower arterial umbilical cord pH compared with planned caesarean section. The rate of asphyxia was similar in both groups. The rate of NICU admission, although not significant, was slightly higher in the vaginal birth group (6.7 % vs. 2.7 %), and NICU length of stay was longer in the caesarean group (1.3 % vs. 1.8 %). A planned caesarean section does not reduce the risk of neonatal death or neurodevelopmental delay up to two years after birth compared to a planned vaginal breech birth [24]. The real advantage of caesarean section for the fetus appears to be the lower early perinatal morbidity, which, however, had no influence on late morbidity [17], 18]. The planned caesarean section can avoid a very rare intrapartum oxygen deficiency and birth trauma [25]. There is some evidence that children after caesarean section have an increased lifelong risk of obesity, respiratory infections, and asthma [26]. An increased risk of neurological diseases and diabetes mellitus type 1 is also discussed [26].

Caesarean section for breech birth is an equivalent alternative for the mother. The risk of maternal morbidity and mortality is similar to that of vaginal birth. This is what we observed in our study, and what is consistent with the results in the literature. However, the special aspects of pregnancy and childbirth after a caesarean section need to be explained [27], 28].

Psychological aspects should be considered in the decision-making process. Women who have a planned caesarean are more likely to feel that they have not played an active role in the birth process [29]. Whereas a successful vaginal birth, or attempt at one, leads to confidence in the power and capabilities of one’s own body, resulting in greater satisfaction with the overall birth experience [29]. This general observation should always be considered on a case-by-case basis and may represent a very different assessment criterion for the pregnant woman.

To avoid high rates of primary section in breech presentation, many publications refer to attempting an external cephalic version [30]. The low complication rate makes this method very promising and it should become part of the standard of care for breech presentation [1].

The newborns of pregnant women who had an MRI scan before attempting vaginal delivery had better neonatal outcomes, with better 1, 5 and 10 min APGAR scores and fewer and shorter stays in intensive care, compared to those who did not. After multivariate regression analysis for fetal birth weight, parity and gestational age, a statistically significant better outcome of 5-min APGAR less than four and shorter NICU stay after admission was observed in the MRI performer group. Stage 1 delay and the occurrence of a pathological CTG were significantly more frequent in the non-MRI group. MRI pelvimetry can be used to collect further clinical parameters and may provide more accurate information about the pregnant woman’s requirements for spontaneous delivery. Klemt et al. reviewed MRI-based pelvimetric measurements as predictors of successful vaginal breech delivery in a cohort of 633 nulliparous women. The size of the obstetric conjugate correlated with the rate of successful vaginal delivery. Successful vaginal breech presentation was not observed in women with an intertubal distance of less than 10.9 cm and a pubic angle of less than 70° [28].

If the obstetric conjugate was less than 11.5 cm, the intertuberous distance less than 10.9 cm, the interspinous distance less than 9.5 cm, or the pubic angle less than 70°, we recommended primary caesarean section to the pregnant woman, as successful spontaneous delivery has not been observed even below these limits in the literature or in our own clinic. If the values were above these limits, vaginal delivery was offered. It is conceivable that knowledge of favourable MRI pelvimetry may influence the obstetrician’s management of the birth process in such a way that a better short-term neonatal outcome can be achieved. However, it should be noted that the number of cases in our study is small and this observation needs to be investigated in further work.

The logistic regression analyses of all vaginally planned breech deliveries for birth weight, fetal head circumference, parity and gestational age on the percentage of probability of vaginal delivery showed that when MR pelvimetry was performed, poorer initial conditions were associated with a higher probability of successful spontaneous delivery.

There is good evidence that the likelihood of a caesarean section generally correlates positively with birth weight in planned vaginal births. This effect is well known in cephalic deliveries and is not surprising in a breech cohort [31]. The same effect is well described for increasing fetal head circumference [32] and gestational age [33], whereas increasing parity increased the change to deliver spontaneously [34]. The size of the obstetric conjugate and the intertuberous distance measured in MR pelvimetry correlates with rate of vaginal deliveries [35]. Lia et al. showed that the intertuberous distance and birthweight are associated with the duration of active second stage of labor in vaginal breech birth [36]. MRI pelvimetry gave the obstetrician more accurate information about the success of a vaginal delivery attempt. This allowed potentially negative preconditions, such as higher estimated fetal weight or fetal head circumference, to be offset by favourable maternal pelvic measurements. Knowledge of pelvic dimensions, even if difficult to measure, has an impact on the management of labour. MRI-based pelvimetry is a valuable tool in selecting appropriate candidates for attempted vaginal delivery in women expecting a breech newborn at term.

Our study has several limitations. The population studied here does not represent an average of the whole population. The women were mostly highly educated, native speakers and very compliant. They had all studied the mode of delivery intensively and had more antenatal care than the average population. In addition, the small sample size of our study should be considered. Therefore, further studies will be necessary to verify the outcome of our observation. Furthermore, the long-term outcomes for mother and newborn were not studied.

Next to careful case selection, vaginal birth of breech position places special demands on the structure of the hospital. In addition to an experienced obstetric team, a neonatal and anaesthetic team should be available at all times [6], 37].

Vaginal breech delivery is associated with lower APGAR scores and umbilical cord arterial pH compared with caesarean section but does not result in increased fetal asphyxia or neonatal intensive care unit admission. Length of stay in the NICU is shorter when a newborn is admitted after vaginal delivery. MRI of the mother’s pelvis may improve the outcome of the newborn by allowing more precise selection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for taking part in the study.

-

Research ethics: Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Hannover Medical School and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (approval number: 10629_BO_K_2022).

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

-

Author contributions: SB: writing and editing the manuscript, statistics, data collection, supervision; LS: data collection, writing and editing the manuscript, statistics; DR: writing the manuscript, supervision; CK: editing the manuscript, supervison; PH: writing and editing the manuscript; LB: writing and editing the manuscript, statistics, data collection, supervision. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Hofmeyr, GJ, Kulier, R, West, HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD000083. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Hannah, ME, Hannah, WJ, Hewson, SA, Hodnett, ED, Saigal, S, Willan, AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet 2000;356:1375–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02840-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. opinion, Ac. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. Am Coll Obstet Gynecol 2002;77:65–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(02)80001-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Impey, LWM, Murphy, DJ, Griffiths, M, Penna LK on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Breech Presentation. BJOG 2017;124:e151–77.Search in Google Scholar

5. Hofmeyr, J, Hannah, M. Five years to the Term Breech Trial: the rise and fall of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Caesarean Section. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry No.015/084, June 2020). Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2021;81:896–921.10.1055/a-1529-6141Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Geburt bei Beckenendlage. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S1-Level, AWMF Registriy No.015/051, February 2005). AWMF 2013Search in Google Scholar

8. Management of breech presentation: green-top guideline No. 20b. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2017;124:e151–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14465.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Deneux-Tharaux, C, Carmona, E, Bouvier-Colle, MH, Breart, G. Postpartum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:541–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000233154.62729.24.Search in Google Scholar

10. Schutte, JM, Steegers, EA, Santema, JG, Schuitemaker, NW, van Roosmalen, J. Maternal Mortality Committee of The Netherlands Society of O. Maternal deaths after elective cesarean section for breech presentation in The Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2007;86:240–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340601104054.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Cali, G, Timor-Tritsch, IE, Palacios-Jaraquemada, J, Monteaugudo, A, Buca, D, Forlani, F, et al.. Outcome of Cesarean scar pregnancy managed expectantly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol: Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:169–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.17568.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Fernandez-Carrasco, FJ, Cristobal-Canadas, D, Gomez-Salgado, J, Vazquez-Lara, JM, Rodriguez-Diaz, L, Parron-Carreno, T. Maternal and fetal risks of planned vaginal breech delivery vs planned caesarean section for term breech birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2022;12:04055. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.12.04055.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Gilbert, WM, Hicks, SM, Boe, NM, Danielsen, B. Vaginal versus cesarean delivery for breech presentation in California: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:911–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006250-200311000-00006.Search in Google Scholar

14. Albrechtsen, S, Rasmussen, S, Reigstad, H, Markestad, T, Irgens, LM, Dalaker, K. Evaluation of a protocol for selecting fetuses in breech presentation for vaginal delivery or cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:586–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70150-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Queenan, JT. Teaching infrequently used skills: vaginal breech delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:405–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000116248.49611.55.Search in Google Scholar

16. Alarab, M, Regan, C, O’Connell, MP, Keane, DP, O’Herlihy, C, Foley, ME. Singleton vaginal breech delivery at term: still a safe option. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103:407–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000113625.29073.4c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Goffinet, F, Carayol, M, Foidart, JM, Alexander, S, Uzan, S, Subtil, D, et al.. Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:1002–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.817.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Fonseca, A, Silva, R, Rato, I, Neves, AR, Peixoto, C, Ferraz, Z, et al.. Breech presentation: vaginal versus cesarean delivery, which intervention leads to the best outcomes? Acta Med Port 2017;30:479–84. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.7920.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Website ACoR. ACR-SPR practise parameter for the safe and optimal performance of fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). American College of Radiology; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

20. Spatz, ES, Krumholz, HM, Moulton, BW. Prime time for shared decision making. JAMA 2017;317:1309–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.0616.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Louwen, F, Daviss, BA, Johnson, KC, Reitter, A. Does breech delivery in an upright position instead of on the back improve outcomes and avoid cesareans? Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;136:151–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Gupta, JK, Hofmeyr, GJ, Shehmar, M. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD002006. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002006.pub3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Bogner, G, Strobl, M, Schausberger, C, Fischer, T, Reisenberger, K, Jacobs, VR. Breech delivery in the all fours position: a prospective observational comparative study with classic assistance. J Perinat Med 2015;43:707–13. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2014-0048.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Whyte, H, Hannah, ME, Saigal, S, Hannah, WJ, Hewson, S, Amankwah, K, et al.. Outcomes of children at 2 years after planned cesarean birth versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the International Randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:864–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Hofmeyr, GJ, Hannah, M, Lawrie, TA. Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD000166. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000166.pub2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Slabuszewska-Jozwiak, A, Szymanski, JK, Ciebiera, M, Sarecka-Hujar, B, Jakiel, G. Pediatrics consequences of caesarean section-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2020;17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Hannah, ME, Hannah, WJ, Hodnett, ED, Chalmers, B, Kung, R, Willan, A, et al.. Outcomes at 3 months after planned cesarean vs planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term: the international randomized Term Breech Trial. JAMA 2002;287:1822–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.14.1822.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Smith, GC, Pell, JP, Dobbie, R. Caesarean section and risk of unexplained stillbirth in subsequent pregnancy. Lancet 2003;362:1779–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14896-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Homer, CS, Watts, NP, Petrovska, K, Sjostedt, CM, Bisits, A. Women’s experiences of planning a vaginal breech birth in Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0521-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Kohls, F, Gebauer, F, Flentje, M, Brodowski, L, von Kaisenberg, CS, Jentschke, M. Current approach for external cephalic version in Germany. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2020;80:1041–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1127-8646.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Poma, PA. Correlation of birth weights with cesarean rates. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1999;65:117–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(98)00261-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Rizzo, G, Aiello, E, Bosi, C, D’Antonio, F, Arduini, D. Fetal head circumference and subpubic angle are independent risk factors for unplanned cesarean and operative delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017;96:1006–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13162.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Keulen, JK, Bruinsma, A, Kortekaas, JC, van Dillen, J, Bossuyt, PM, Oudijk, MA, et al.. Induction of labour at 41 weeks versus expectant management until 42 weeks (INDEX): multicentre, randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ 2019;364:l344. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Gibb, DM, Cardozo, LD, Studd, JW, Magos, AL, Cooper, DJ. Outcome of spontaneous labour in multigravidae. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1982;89:708–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb05095.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Klemt, AS, Schulze, S, Bruggmann, D, Louwen, F. MRI-based pelvimetric measurements as predictors for a successful vaginal breech delivery in the Frankfurt Breech at term cohort (FRABAT). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;232:10–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.09.033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Lia, M, Martin, M, Koltzsch, E, Stepan, H, Dathan-Stumpf, A. Mechanics of vaginal breech birth: factors influencing obstetric maneuver rate, duration of active second stage of labor, and neonatal outcome. Birth 2024;51:530–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12808.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Vaginale Geburt am Termin. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015-083, December 2020). AWMF 2021.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?