Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

-

Murat Levent Dereli

, Mehmet Obut

, Sadullah Özkan

, Sadun Sucu

, Fahri Burçin Fıratlıgil

, Dilara Kurt

, Ahmet Kurt

, Kemal Sarsmaz

, Harun Egemen Tolunay

, Ali Turhan Çağlar

and Yaprak Engin Üstün

Abstract

Objectives

As previous studies on the use of a cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth (PTB) have produced conflicting results, we aimed to investigate the feasibility, acceptability and safety of a new technique for inserting a cervical pessary and compare it with the traditional technique in patients at high risk of PTB.

Methods

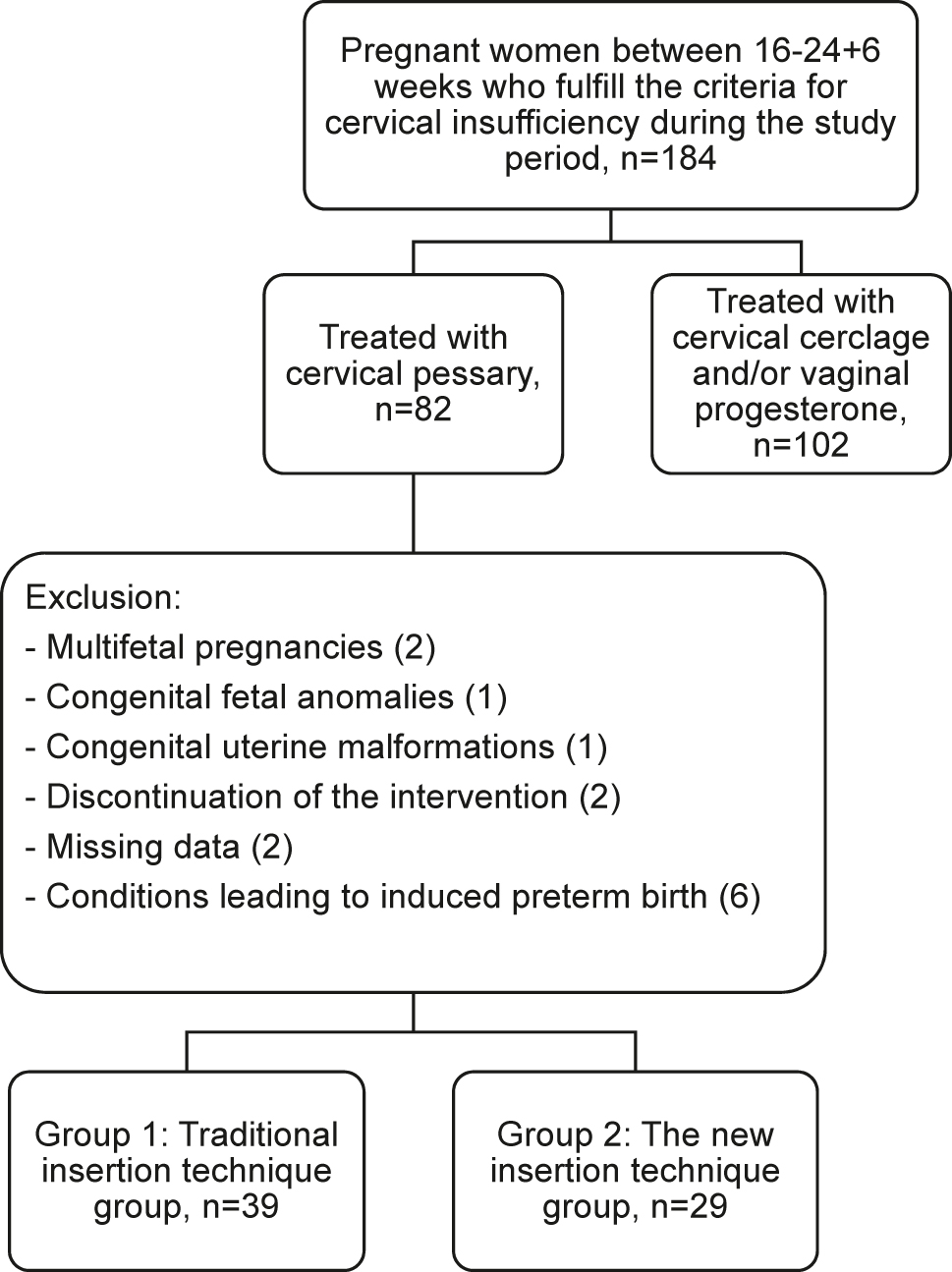

Women at high risk of PTB treated with a cervical pessary between January 2018 and January 2021 were retrospectively evaluated. After applying exclusion criteria, a total of 68 eligible patients were identified and retrospectively analyzed. The primary outcome was spontaneous PTB before 34 weeks’ gestation (WG).

Results

Of 68 participants, 39 were treated with the traditional method (group 1) and 29 with the new insertion technique (group 2). The rate of spontaneous PTB before 34 WG was significantly lower in group 2 (p=0.020). Birthweight, APGAR scores and satisfaction with the method were significantly higher, while PTB before 37 WG was significantly lower in group 2 (p=0.043, 0.010, 0.009, 0.042 and 0.014, respectively). There were no significant differences in the rates of perinatal death (12.8 vs. 3.4 % in groups 1 and 2, respectively; p=0.229). The concomitant use of vaginal progesterone was required more frequently in group 1. According to the binary regression analysis, the new insertion technique resulted in a 5.42 and 3.97-fold protection against PTB before 34 and 37 WG.

Conclusions

Our preliminary results show that our new technique of pessary insertion is more effective than the traditional method in preventing PTB due to cervical shortening.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB), one of the main causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality, is any live birth before 37 weeks of gestation (WG), which occurs in almost 10 % of all births and places a huge burden on national economies [1], [2], [3]. Cervical insufficiency or incompetence, on the other hand, is one of the most common causes of PTB, in which many etiological factors play a role. The diagnosis is usually based on the medical history, gynecological or sonographic examinations [4].

Cervical cerclage is a common surgical procedure to keep the cervix closed and prevent PTB [5]. Like all surgical procedures, cervical cerclage is an invasive procedure that requires anesthesia and is associated with potential complications such as premature rupture of membranes, cervical injury, bleeding, infection, pregnancy loss and even the formation of a vesicovaginal fistula [6]. Alternatively, vaginal progesterone has been also recommended for the prevention of PTB in singleton pregnancies [7], 8].

On the other hand, cervical pessaries are designed and approved for the prolongation of pregnancy in patients with a short cervix, as determined by gestational age-specific centiles of cervical length (CL), and/or an overstretched uterus, as in multiple pregnancies and polyhydramnios, as well as in patients with placenta previa to stabilize the cervix [9]. Furthermore, insertion of an Arabin cervical pessary to prevent PTB is a simple, effective and non-invasive alternative that does not require medication, surgery or anesthesia, with acceptable complications such as increased vaginal discharge, pelvic discomfort and expulsion of the pessary [10]. However, in the years since the introduction of the cervical pessary in the 1950s, studies on the effectiveness of the pessary in preventing PTB have produced conflicting results, with most showing that the pessary is as effective as other prevention methods [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]. However, the traditional technique of cervical pessary insertion, in which the pessary is inserted directly into the upper vagina, does not seem to be able to fulfill its task completely. On the other hand, although treatment with the pessary is apparently simple, there is a confidence and learning curve. In this context, there are some studies that emphasize the importance of the learning curve, proper application technique and appropriate management to achieve significant improvements in the prevention of PTB [16], [17], [18]. França et al. reported that a learning curve of at least 30 applications was necessary to prevent PTB effectively enough [17]. On this basis, we hypothesized that our new technique, in which the pessary can be placed more firmly around the cervix, could be more effective than the traditional method in preventing PTB in women with cervical insufficiency. Therefore, in this context, we aimed to investigate the feasibility, efficacy and safety of our new technique for cervical pessary placement by describing our new technique and comparing the results with the traditional method.

Subjects and methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective study of women with singleton pregnancies at high risk for PTB due to cervical insufficiency who were treated with a cervical pessary between January 1, 2018, and January 1, 2021, at a large tertiary research and teaching hospital. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on Human Experimentation. The Ethics Committee approved the conduct, protocol and procedures of the study (date:11.01.2022, number: 01/12). Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants. After approval, a retrospective review of the patients’ medical records was performed.

Definitions, characteristics of study population, patient selection and outcome measures

Gestational age was calculated from the first day of the last menstrual period and confirmed by sonographic measurement of the crown-rump length. If the calculated gestational age contained fractions of days, the gestational age was rounded up or down to the nearest whole week. Fetal biometry and anatomic assessment as well as measurement of CL were performed using the Voluson 730 Expert sonography system (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA).

The indications for insertion of a cervical pessary in singleton pregnancies without significant regular uterine contractions, onset of labor, rupture of membranes or infection were mainly based on the instructions for use (IFU) of the Arabin pessary and the centiles for transvaginal measurement of CL according to the centile charts recommended by Salomon et al. [19] and were as follows: 1. A CL between the 10th–25th centiles with a history of spontaneous PTB or 2. A CL between the 5th–10th centiles with no additional risks [9]. In the latter group of patients with a cervical dilatation ≤1 cm, the cervical pessary was favored, while cerclage was preferred in patients with a cervical dilatation >1 cm. The combined use of a cerclage with a cervical pessary was considered especially for patients with a CL <3rd centile and for patients with exposed and prolapsed membranes requiring emergency cerclage as previously reported by Wolnicki et al. [20]. In our clinic, a diagnostic amniocentesis is routinely performed to rule out an intraamniotic infection before a cerclage is performed alone or in combination with a cervical pessary in the presence of cervical dilatation. Further treatment depends on the results of the amniocentesis: (1) ≥14 mg/dL glucose and negative Gram stain: We perform the procedure(s). (2) <14 mg/dL glucose and positive Gram stain (high suspicion of intraamniotic infection): Contraindication for immediate performance of the procedure(s). Patients receive prophylactic antibiotic treatment with ampicillin 2 g/6 h, ceftriaxone 1 g/12 h (both intravenous) and clarithromycin 500 mg/12 h (oral) while waiting for culture reports. Subsequent management based on culture results. (3) Discrepant results between glucose and Gram stain: same steps are followed as for highly suspected intraamniotic infection.

All live singleton pregnancies between 16 and 28 WG that were treated with an Arabin cervical pessary during the study period due to a high risk of spontaneous PTB based on the above criteria were included in the study. In the first 1.5 years of the study, the pessary applications were performed according to the traditional method by an experienced perinatologist with 10 years of experience in the application of the Arabin pessary. Since the beginning of the remaining 1.5 years of the 3-year period of the study, when another exclusive perinatologist with the same experience in the application of the Arabin pessary started to work in our clinic, we have described this new method pioneered by this perinatologist and started to apply it to indicated patients. Pregnancies with multiples, fetal anomalies, ruptured membranes, painful regular uterine contractions; women with cervical dilatation of >1 cm, cerclage in the current pregnancy, congenital uterine malformations, vaginal infection and active vaginal bleeding were excluded. Conditions leading to induced PTB, including pre-eclampsia, placenta previa, placenta accreta spectrum disorders and fetal growth restriction; women with missing data and women who discontinued the intervention were also not included. After applying the exclusion criteria, the patients were divided into two groups according to the technique of pessary application: traditional insertion technique group (group 1) (n=39) and the new insertion technique group (group 2) (n=29). These groups were then compared. The primary outcome was delivery before 34 WG, while the secondary outcomes were delivery before 37 WG, birthweight and APGAR-1 and 5 scores [21].

The Arabin pessary (Dr. Arabin GmbH & Co. KG, Witten, Germany) is an elastic, dome-shaped cervical pessary made of silicone, which is available in various sizes for different cervical dimensions (lower diameter 65/70 mm, upper diameter 32/35 mm, height of the curvature 17/21/25/30 mm) [9]. In traditional insertion technique, the pessary is gently folded and inserted as high as possible at the level of the vaginal vault, with its curvature facing upwards so that the larger diameter is supported by the pelvic floor and the smaller diameter can surround the cervix while the woman is in the recumbent position. Satisfaction with the method is defined as general satisfaction and the positive consideration of offering the method to someone else. The need for concomitant vaginal progesterone therapy was at the discretion of the treating clinicians. Progesterone was administered vaginally at a dose of 200 mg daily before bedtime.

Steps of the procedure

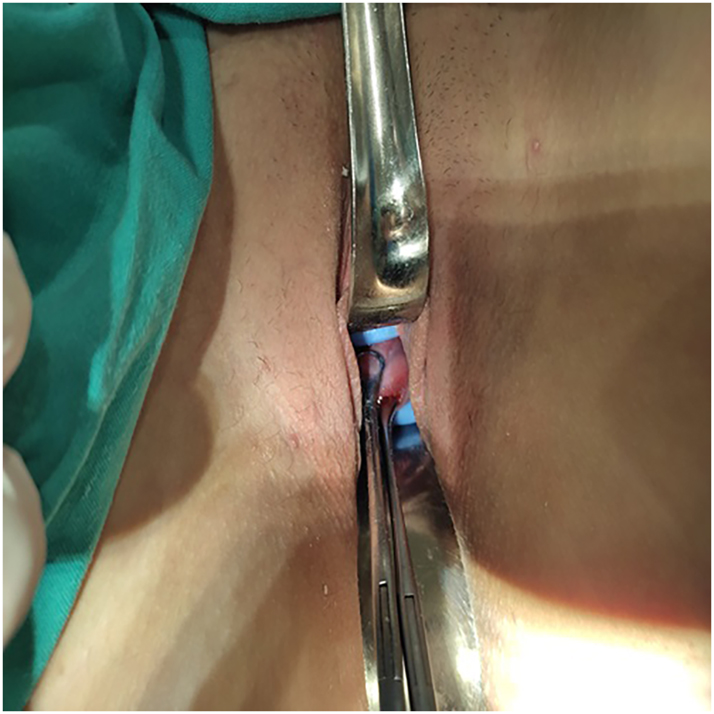

Once written consent for the procedure has been obtained, the woman is placed in the lithotomy position and the cervix is examined with a speculum to determine the optimal pessary size. A pair of ring forceps are passed through the central hole of the pessary, with the curvature of the pessary facing upwards (Figure 1). The vaginal entrance is opened and the cervix is exposed with the help of two vaginal retractors. The upper and lower cervical lips are carefully grasped with the ring forceps, which are already inserted through the center hole of the pessary. The pessary is pushed forward over the shafts of the ring forceps into the vagina and placed firmly around the cervix (Figure 2). Finally, the forceps are removed.

Two ring forceps are inserted through the pessary ring with the curvature of the pessary facing upwards.

The pessary is pushed forward over the shafts of the ring forceps into the vagina and placed firmly around the cervix.

After insertion of the pessary (for both techniques), the patient is observed for a few hours for uterine contractions, pain, vaginal bleeding or rupture of the membranes. After 48 h, a vaginal examination with transvaginal sonography is performed to check the position of the pessary, and follow-up examinations were then carried out every three weeks. The intervals between examinations, the need for hospitalization and/or additional treatment were determined individually and modified depending on the severity of the condition, e.g., in the case of an imminent PTB. The pessary should remain in place until the 37th WG, unless it has to be removed for another indication. Premature removal was performed in cases of persistent, tocolysis-resistant uterine contractions, active vaginal bleeding, severe discomfort or a desire to discontinue the procedure. In the case of a pessary that was stuck around the cervix due to cervical oedema or uterine contractions, the pessary was removed by cutting one side so as not to injure the patient. The patients were cared for by the same perinatologist for the entire duration of their pessary treatment.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyzes were performed with Jamovi, an open statistical software. Variables were analyzed using visual (histogram, probability plots) and analytical methods (Kolmogrov–Simirnov/Shapiro–Wilk test) to determine whether they were normally distributed or not. The Levene test was used to assess the homogeneity of variance. Descriptive analyzes were presented using means and standard deviations for normally distributed variables. The t-test for independent samples was used to compare these parameters between groups. For the non-normally distributed numerical data, descriptive analyzes were performed using medians and quartiles (Q1-Q3). Mann–Whitney U-tests were performed to compare these parameters between groups. Descriptive analyzes were performed for the categorical variables using frequencies and percentages. Relationships between categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (if the assumptions of the chi-square test did not apply due to low expected cell counts). For the multivariate analysis, the possible factors identified by univariate analyzes were further entered into a binary logistic regression analysis to identify additional independent predictors of delivery before 34 and 37 WG. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to assess model fit. A type I error level of 5 % was used to derive statistical significance. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered a statistically significant result.

Results

During the study period, 82 women were identified for data collection. However, 14 of these women were excluded. Finally, a total of 68 eligible participants, 39 of whom were treated with the traditional insertion technique (group 1) and 29 with new insertion technique (group 2), were included in the study (Figure 3).

Flow diagram of the study groups.

A comparison of baseline characteristics and clinical variables of the study population was summarized in Table 1. A further comparison of the clinical characteristics at the time of application as well as the perinatal and birth-related characteristics between the two groups is shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in mode of delivery (p=0.644). The median gestational age at pessary application was significantly higher in group 1 (p=0.019) and the median time between pessary application and delivery was significantly longer in group 2 (p<0.001). Besides, median gestational age at delivery, birthweight, APGAR-1 and -5 scores and women’s satisfaction with the method were higher (p=0.011, 0.043, 0.010, 0.009 and 0.042, respectively) while the median numbers of PTB before 34 and 37 WG were lower in group 2 (p=0.020 and 0.014, respectively). In addition, concomitant use of vaginal progesterone was significantly more frequent in group 1 (p=0.005). A total of six perinatal deaths due to extreme prematurity occurred in both groups [5 (12.8 %) vs. 1 (3.4 %) in groups 1 and 2, respectively; p=0.229]. Newborns with a birthweight >2,500 g accounted for 82.8 % of all births in group 2, while this rate was 41 % in group 1, representing a significant difference between the two groups (p=0.001). However, the rate of newborns with a birthweight between 1,500 and 2,500 g was significantly higher in group 1, while no significant difference was found for a birthweight <1,500 g (p=0.010 and 0.229, respectively) (Table 3).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Group 1 (n=39) | Group 2 (n=29) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 26 (24–33) | 30 (25–32) | 0.718 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27 (24.5–30) | 27 (26–28.5) | 0.866 |

| Gravidity, n | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–3) | 0.414 |

| Parity, n | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.814 |

| Nulliparity, n | 23 (59) | 15 (51.7) | 0.727 |

| Diagnostic criteria for cervical insufficiency | |||

| CL 5th–10th centiles, n | 31 (79.5) | 21 (72.4) | 0.696 |

| CL 10th–25th centiles and history of ≥2 s trimester losses and/or PTB <28 weeks, n | 8 (20.5) | 8 (28.6) | |

| Previous delivery mode | |||

| Vaginal delivery (+) | 14 (35.9) | 8 (27.6) | 0.354 |

| Cesarean delivery (+) | 2 (5.1) | 4 (13.8) | |

-

BMI, body-mass index; CL, cervical length; PTB, preterm birth. Data are expressed as median (1st quartile–3rd quartile) or number (percentage) where appropriate. A p-value of <0.05 indicates a significant difference. Statistically significant p-values are in bold.

Comparison of clinical characteristics at the time of application, perinatal and birth characteristics.

| Variable | Group 1 (n=39) | Group 2 (n=29) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at pessary application, weeks | 23 (20–25) | 20 (19–23) | 0.019 | |

| Pessary application-to-delivery interval, days | 88 (70–97) | 116 (101–125) | <0.001 | |

| Concomitant progesterone user, n | 37 (94.9) | 19 (65.5) | 0.005 | |

| Perinatal death, n | 5 (12.8) | 1 (3.4) | 0.229 | |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks | 36 (31–37) | 37 (36–37) | 0.011 | |

| Delivery before 34 weeks, n | 15 (38.5) | 3 (10.3) | 0.020 | |

| Delivery before 37 weeks, n | 25 (64.1) | 9 (31) | 0.014 | |

| Birthweight, grams | 2,424 (1,914–3,000) | 2,810 (2,548–3,020) | 0.043 | |

| <1,500 g, n | 5 (12.8) | 1 (3.4) | 0.229 | 0.002 |

| 1,500–2,500 g, n | 18 (46.2) | 4 (13.8) | 0.010 | |

| >2,500 g, n | 16 (41) | 24 (82.8) | 0.001 | |

| Mode of delivery, n | ||||

| Vaginal | 25 (26.1) | 21 (71.4) | 0.644 | |

| Cesarean | 14 (35.9) | 8 (27.6) | ||

| APGAR-1 scores | 8 (6–9) | 9 (9–9) | 0.010 | |

| APGAR-5 scores | 9 (8–10) | 10 (10–10) | 0.009 | |

| Satisfaction with the method | 22 (56.4) | 24 (82.8) | 0.042 | |

-

APGAR-1 and 5, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration scores at first and fifth minutes; BMI, body-mass index. Data are expressed as median (1st quartile–3rd quartile) or number (percentage) where appropriate. A p-value of <0.05 indicates a significant difference. Statistically significant p-values are in bold.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for preterm delivery before 34 and 37 weeks of gestation.

| Variable | Delivery before 34 WG | Delivery before 37 WG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | p-Value | OR (95 % CI) | p-Value | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.906–1.099) | 0.968 | 0.97 (0.883–1.049) | 0.386 |

| BMI | 0.91 (0.773–1.081) | 0.295 | 1.00 (0.871–1.144) | 0.981 |

| Multiparity | 1.02 (0.344–3.012) | 0.974 | 2.06 (0.779–5.461) | 0.145 |

| History of PTB <28 WG | 2.22 (0.744–6.639) | 0.153 | 1.63 (0.615–4.310) | 0.326 |

| History of ≥2 s trimester losses | 2.22 (0.744–6.623) | 0.153 | 2.70 (0.994–7.331) | 0.051 |

| CL between the 5th–10th centiles | 1.11 (0.305–4.003) | 0.879 | 11.20 (2.299–54.562) | 0.003 |

| Traditional method | 5.42 (1.393–21.064) | 0.015 | 3.97 (1.426–11.040) | 0.008 |

| Traditional methoda | 5.64 (1.387–22.939) | 0.016 | 9.42 (2.187–40.632) | 0.003 |

-

BMI, body-mass index; CI, confidence interval; CL, cervical length; OR, odds ratio; PTB, preterm birth; WG, weeks of gestation. A p-value of <0.05 indicates a significant difference. Statistically significant p-values are in bold. aAge, BMI, multiparity, a history of ≥2 s trimester losses, a history of PTB <28 WG and cervical shortening between the 5th and 10th centiles adjusted.

In the binary logistic regression analysis, the use of the traditional method was identified as an independent risk factor for delivery before 34 WG [odds ratio (OR) =5.42, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.393–21.064, p=0.015 and before 37 WG (OR=3.97, 95 % CI 1.426–11.040, p=0.008)]. The traditional method was also found to be an independent risk factor for delivery before 34 WG (OR=5.64, 95 % CI 1.387–22.939, p=0.016) and before 37 WG (OR=9.42, 95 % CI 2.187–40.632, p=0.003) when patients were adjusted for age, BMI, multiparity, a history of ≥2 s trimester losses, a history of PTB <28 WG and CL between the 5th–10th centiles. Using our new technique for inserting a cervical pessary resulted in 5.42- and 3.97-fold protection (and even 5.64 and 9.42-fold protection after the above adjustment) against PTB before 34 and 37 WG, respectively. CL between the 5th–10th centiles was another independent risk factor only for delivery before 37 WG (OR=11.20, 95 % CI 2.299–54.562, p=0.003), while age, BMI, multiparity, a history of ≥2 s trimester losses and/or PTB <28 WG were not independent risk factors for delivery before both 34 and 37 WG.

Discussion

The main results of our study were: (1) The rate of spontaneous PTB before 34 WG as the primary outcome was significantly lower in the new technique group. (2) Birthweight, APGAR-1 and -5 scores and women’s satisfaction with the method were significantly higher, while PTB before 37 WG was significantly lower in the new technique group. (3) Concomitant use of vaginal progesterone was required more frequently in the group using the traditional method. (4) Traditional method was identified as an independent factor for delivery before 34 and 37 WG.

In both halves of the study, the indications, treatment strategy and adherence to the current IFU of Arabin pessary were the same, and both periods involved qualified and audited implementers who had the same level of expertise in the use of cervical pessaries in patients at high risk of PTB. In the second half, all pessaries were inserted using either the new or the traditional method by the same perinatologist who had pioneered the new technique. Increasing experience may have contributed to the better results with the new method. However, this contribution affected the results of both methods equally, as the inventor who carried out both methods was the same in the second half. The contribution of increasing practical experience to better results is therefore undeniable, but the most important contribution was made by the new technique.

The use of the cervical pessary for the prevention of PTB has always been controversial, as some studies have shown a benefit [22], 23], while others have not [23], [24], [25], [26]. However, the conflicting results could be related to various factors, such as the use of different CL cut-offs for increased risk of PTB, the presence of obstetricians who were not adequately trained in the use of the pessary, and the different designs of the studies. As Kyvernitakis et al. emphasized in their integrity meta-analysis focusing on compliance with the European Medical Device Regulation, varying compliance with IFUs and a learning curve can influence the effectiveness of the pessary and thus the results [27]. This meta-analysis also reported that a significant number of pessary implementers are still not sufficiently aware of the importance of ensuring that medical devices are used in accordance with the IFU, so that serious legal consequences may be unavoidable [27].

In addition, a recent randomized controlled trial has shown that cerclage, cervical pessary and vaginal progesterone reduce PTB equally when used for the indication of a short cervix. This emphasizes that the effectiveness of the pessary is closely related to its use according to the indications stated in the IFU [28]. The results of this study can be used as a counseling tool for clinicians in the management of women with a short cervix. On the other hand, Seravalli et al. pointed out the importance of having a previous episode of threatened preterm labor in the current pregnancy, another condition that should be considered in patients in whom pessary treatment is planned due to cervical shortening [29]. They found that the use of pessaries in women with a short cervix after an episode of threatened preterm labor was less effective than in women with an asymptomatic cervical shortening.

The insertion of a cervical pessary is an affordable, safe and non-invasive method for the prevention of PTB that has been used for over two decades [30]. Although the mechanisms that counteract cervical insufficiency are not clearly known, the pessaries act as a lever that pushes back the cervical canal, which is already centralized by cervical insufficiency. Much of the pressure exerted on the cervical canal by the pregnancy itself is therefore directed towards the anterior lower uterine segment [30]. Another proposed mechanism is that the pessary ensures the integrity of the mucus plug and maintains the immunological barrier against ascending infections, thus contributing to the suppression of labor-inducing inflammation and associated processes [22], 31]. Once the pessary is inserted using our new technique, the above-mentioned mechanisms for preventing PTB can potentially become much more effective and better stabilization of the cervical canal length can be achieved through perfect positioning. Therefore, this technique can also be an alternative for physicians who are not confident with purely digital insertion.

It is an indisputable fact that in women with cervical insufficiency who have cervical changes, especially advanced cervical effacement and/or painless dilatation, the insertion of a cervical pessary using the traditional method can be difficult and is usually ineffective. However, in cases with cervical dilatation to a certain degree (e.g., less than 1–2 cm) without advanced effacement, correct placement may also be feasible using our new technique, in which the pessary is placed under the guidance of the forceps grasping the cervical lips.

Cervical pessary has an acceptable range of side effects. In a questionnaire study examining the impact of cervical pessary use during pregnancy on daily life, data such as perceived discomfort, side effects and pain during removal, and fulfillment of patients’ expectations of treatment were analyzed using numerical rating scales from 0 to 10, and most women reported an overall positive experience. The level of patient satisfaction was high and only one participant (0.6 %) had to be removed prematurely due to discomfort [32]. As vaginal discharge is the most frequently reported side effect, women should be informed before using the pessary. However, it should also be mentioned that this vaginal discharge does not always mean an infection, unless an infection is detected by vaginal culture [32].

In our study, despite the potential pain sensation during grasping of the cervical lips with ring forceps, patient satisfaction with the new method was higher than with the traditional method in which no additional instrumentation was required. This could be due to the fact that a significant proportion of births in the traditional technique group occurred at lower gestational ages than in the new technique group and therefore a negative experience related to the premature birth could also have influenced the reported experiences of some women. As pessary stabilization with our new technique is potentially much more effective than the traditional method, concomitant vaginal progesterone therapy was less preferred in group 2. It is also likely that the less frequent use of vaginal progesterone influenced the higher satisfaction with the method in group 2, as vaginal progesterone is an independent risk factor for vaginal discharge.

As far as we know, this is the first study to propose a new technique for inserting a cervical pessary as an alternative to the traditional method. Major strength of this study is that it was conducted in a large tertiary reference hospital that uses the same algorithms for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. However, our study has some limitations, mainly due to its retrospective nature, the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group. Although the results may not be representative of the entire population of interest due to the relatively small sample size, as previously mentioned, the present study describes a novel technique that has never been performed before. In addition, the significantly higher rates of concomitant progesterone use in the traditional method group may have underestimated the success of the new technique. On the other hand, the fact that the new technique was used at a time when clinicians, and in particular the perinatologist who introduced the new technique, were more experienced may have led to some bias in success rates. Moreover, the definition of satisfaction with the method was not specific enough, as it was defined with a general satisfaction and the positive consideration of offering the method to someone else. Satisfaction with the method should be evaluated with a Likert scale and defined more objectively. On the other hand, despite the retrospective nature of the study, there were no between-group imbalances in baseline variables, including maternal age, BMI, nulliparity, parity. Furthermore, as the cases in which PTB or termination of pregnancy was indicated and the women who discontinued the method were not included in the analysis, any associated bias in the results could also be excluded.

In conclusion, the preliminary results of our study suggest that our new technique of pessary placement may be more effective in preventing PTB, especially in women with a short or soft cervix, as it allows the pessary to be inserted higher than with digital procedure alone. Further prospective, randomized, controlled trials with larger sample sizes comparing our forceps-guided technique with the traditional method are needed to better demonstrate the efficacy and limitations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the women who participated in this study.

-

Research ethics: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The University of Health Sciences Turkey, Ankara Etlik Zübeyde Hanım Women's Health Training and Research Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Date: 11.01.2022; number: 01/12) granted approval of the study. The study was conducted at the Department of Perinatology, Etlik Lady Zübeyde Maternity and Women's Health Education and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. ML Dereli: Conceptualization (Lead), Project administration (Lead), Writing – original draft (Lead), Investigation (Equal). M Obut: Investigation (Equal), Methodology (Equal). S Özkan: Investigation (Equal). S Sucu: Investigation (Equal), Formal analysis (Lead), Methodology (Equal), Software (Equal). FB Fıratlıgil: Investigation (Equal). D Kurt: Investigation (Equal), Data curation (Equal). A Kurt: Investigation (Equal), Data curation (Equal). K Sarsmaz: Investigation (Equal), Software (Equal). HE Tolunay: Investigation (Equal). AT Çağlar: Resources (Lead), Supervision (Equal). Y Engin Üstün: Supervision (Equal).

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. Blencowe, H, Cousens, S, Oestergaard, MZ, Chou, D, Moller, AB, Narwal, R, et al.. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60820-4.Search in Google Scholar

2. Malka, ES, Solomon, T, Kassa, DH, Erega, BB, Tufa, DG. Time to death and predictors of mortality among early neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care unit of Addis Ababa public Hospitals, Ethiopia: institutional-based prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2024;19:e0302665. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302665.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Petrou, S, Yiu, HH, Kwon, J. Economic consequences of preterm birth: a systematic review of the recent literature (2009–2017). Arch Dis Child 2019;104:456–65. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-315778.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Roman, A, Suhag, A, Berghella, V. Overview of cervical insufficiency: diagnosis, etiologies, and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2016;59:237–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/grf.0000000000000184.Search in Google Scholar

5. McAuliffe, L, Issah, A, Diacci, R, Williams, KP, Aubin, AM, Phung, J, et al.. McDonald versus Shirodkar cerclage technique in the prevention of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2023;130:702–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17438.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Alani, S, Wang, J, Suarthana, E, Tulandi, T. Complications associated with cervical cerclage: a systematic review. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther 2023;12:4–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/gmit.gmit_61_22.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Peng, L, Gao, Y, Yuan, C, Kuang, H. Effects of vaginal progesterone and placebo on preterm birth and antenatal outcomes in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervix on ultrasound: a meta-analysis. Front Med 2024;11:1328014. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1328014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Maarof, C, Dauod, A, Dunham, R. Prevalence of preterm delivery among women who receive progesterone supplementation during pregnancy: cross-sectional observational study. Georgian Med News 2024;348:36–9.Search in Google Scholar

9. Dr. Arabin GmbH & Co KG. Instructions cerclage pessary (Type A unperforated, Type ASQ perforated). [Online]. Available from: https://dr-arabin.de/wp-content/uploads/Instructions_Cerclage_Pessaries.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwj2z6-Tm5aJAxXvVfEDHWWJD3EQFnoECCMQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0fu0DM1iaNU16iuhMqBTnn [Accessed 16 Sep 2024].Search in Google Scholar

10. Ivandic, J, Care, A, Goodfellow, L, Poljak, B, Sharp, A, Roberts, D, et al.. Cervical pessary for short cervix in high risk pregnant women: 5 years experience in a single centre. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;33:1370–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1519018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Jafarzade, A, Aghayeva, S, Mungan, T, Biri, A, Ekiz, OU. Arabin-pessary or McDonald cerclage in cervical shortening? Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2023;45:e764–9. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1776033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Antczak-Judycka, A, Sawicki, W, Spiewankiewicz, B, Cendrowski, K, Stelmachów, J. Comparison of cerclage and cerclage pessary in the treatment of pregnant women with incompetent cervix and threatened preterm delivery. Ginekol Pol 2003;74:1029–36.Search in Google Scholar

13. Hezelgrave, NL, Watson, HA, Ridout, A, Diab, F, Seed, PT, Chin-Smith, E, et al.. Rationale and design of SuPPoRT: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial to compare three treatments: cervical cerclage, cervical pessary and vaginal progesterone, for the prevention of preterm birth in women who develop a short cervix. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:358. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1148-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Wennerholm, UB, Bergman, L, Kuusela, P, Ljungström, E, Möller, AC, Hongslo Vala, C, et al.. Progesterone, cerclage, pessary, or acetylsalicylic acid for prevention of preterm birth in singleton and multifetal pregnancies – a systematic review and meta-analyses. Front Med 2023;10:1111315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1111315.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Goodell, M, Leechalad, L, Soti, V. Are cervical pessaries effective in preventing preterm birth? Cureus 2024;16:e51775. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51775.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Liem, SM, Schuit, E, van Pampus, MG, van Melick, M, Monfrance, M, Langenveld, J, et al.. Cervical pessaries to prevent preterm birth in women with a multiple pregnancy: a per-protocol analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:444–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12849.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. França, MS, Hatanaka, AR, Cruz, JJ, Andrade Júnior, VL, Kawanami Hamamoto, TE, Sarmento, SGP, et al.. Cervical pessary plus vaginal progesterone in a singleton pregnancy with a short cervix: an experience-based analysis of cervical pessary’s efficacy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:6670–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.1919076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Cannie, MM, Dobrescu, O, Gucciardo, L, Strizek, B, Ziane, S, Sakkas, E, et al.. Arabin cervical pessary in women at high risk of preterm birth: a magnetic resonance imaging observational follow-up study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;42:426–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12507.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Salomon, LJ, Diaz-Garcia, C, Bernard, JP, Ville, Y. Reference range for cervical length throughout pregnancy: non-parametric LMS-based model applied to a large sample. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;33:459–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.6332.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Wolnicki, BG, von Wedel, F, Mouzakiti, N, Al Naimi, A, Herzeg, A, Bahlmann, F, et al.. Combined treatment of McDonald cerclage and Arabin-pessary: a chance in the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;33:3249–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2019.1570123.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Apgar, V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg 1953;32:260–7. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-195301000-00041.Search in Google Scholar

22. Saccone, G, Maruotti, GM, Giudicepietro, A, Martinelli, P. Effect of cervical pessary on spontaneous preterm birth in women with singleton pregnancies and short cervical length: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:2317–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.18956.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Goya, M, Pratcorona, L, Merced, C, Rodó, C, Valle, L, Romero, A, et al.. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:1800–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60030-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Hui, SY, Chor, CM, Lau, TK, Lao, TT, Leung, TY. Cerclage pessary for preventing preterm birth in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix at 20 to 24 weeks: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Perinatol 2013;30:283–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1322550.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Hoffman, MK, Clifton, RG, Biggio, JR, Saade, GR, Ugwu, LG, Longo, M, et al.. Cervical pessary for prevention of preterm birth in individuals with a short cervix: the TOPS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2023;330:340–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.10812.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Pacagnella, RC, Silva, TV, Cecatti, JG, Passini, RJr., Fanton, TF, Borovac-Pinheiro, A, et al.. Pessary plus progesterone to prevent preterm birth in women with short cervixes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004634.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Kyvernitakis, I, Baschat, AA, Malan, M, Rath, W, Berger, R, Henrich, W, et al.. Cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth and poor neonatal outcome: an integrity meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials focusing on adherence to the European Medical Device Regulation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2024;165:607–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.15169.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Hezelgrave, NL, Suff, N, Seed, P, Robinson, V, Carter, J, Watson, H, et al.. Comparing cervical cerclage, pessary and vaginal progesterone for prevention of preterm birth in women with a short cervix (SuPPoRT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2024;21:e1004427. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004427.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Seravalli, V, Campana, D, Strambi, N, Vialetto, D, Di Tommaso, M. Effectiveness of cervical pessary in women with arrested preterm labor compared to those with asymptomatic cervical shortening. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:8141–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.1962844.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Arabin, B, Halbesma, JR, Vork, F, Hübener, M, van Eyck, J. Is treatment with vaginal pessaries an option in patients with a sonographically detected short cervix? J Perinat Med 2003;31:122–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm.2003.017.Search in Google Scholar

31. Becher, N, Adams Waldorf, K, Hein, M, Uldbjerg, N. The cervical mucus plug: structured review of the literature. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009;88:502–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340902852898.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Seravalli, V, Strambi, N, D’Arienzo, A, Magni, F, Bernardi, L, Morucchio, A, et al.. Patient’s experience with the Arabin cervical pessary during pregnancy: a questionnaire survey. PLoS One 2022;17:e0261830. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261830.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- AI and early diagnostics: mapping fetal facial expressions through development, evolution, and 4D ultrasound

- Investigation of cardiac remodeling and cardiac function on fetuses conceived via artificial reproductive technologies: a review

- Commentary

- A crisis in U.S. maternal healthcare: lessons from Europe for the U.S.

- Opinion Paper

- Selective termination: a life-saving procedure for complicated monochorionic gestations

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Exploring the safety and diagnostic utility of amniocentesis after 24 weeks of gestation: a retrospective analysis

- Maternal and neonatal short-term outcome after vaginal breech delivery >36 weeks of gestation with and without MRI-based pelvimetric measurements: a Hannover retrospective cohort study

- Antepartum multidisciplinary approach improves postpartum pain scores in patients with opioid use disorder

- Determinants of pregnancy outcomes in early-onset intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Copy number variation sequencing detection technology for identifying fetuses with abnormal soft indicators: a comprehensive study

- Benefits of yoga in pregnancy: a randomised controlled clinical trial

- Atraumatic forceps-guided insertion of the cervical pessary: a new technique to prevent preterm birth in women with asymptomatic cervical shortening

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Impact of screening for large-for-gestational-age fetuses on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a prospective observational study

- Impact of high maternal body mass index on fetal cerebral cortical and cerebellar volumes

- Adrenal gland size in fetuses with congenital heart disease

- Aberrant right subclavian artery: the importance of distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated cases in prenatal diagnosis and clinical management

- Short Communication

- Trends and variations in admissions for cannabis use disorder among pregnant women in United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Trisomy 18 mosaicism – are we able to predict postnatal outcome by analysing the tissue-specific distribution?