Abstract

Objectives

Perinatal death reviews investigate the causes of perinatal mortality, identify potentially avoidable factors, and may help prevent further deaths. This study aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a standardised perinatal mortality review tool in Irish maternity units by engaging with healthcare professionals about their opinions on the existing system and implementing a standardised system.

Methods

This study involved semi-structured interviews with staff from three maternity units of various sizes in Ireland. Recruitment involved purposive and snowball sampling. Interviews took place from May to December 2022 and covered topics such as the existing perinatal mortality review process, staff experiences with reviews and proposed changes to the system. Thematic analysis was performed.

Results

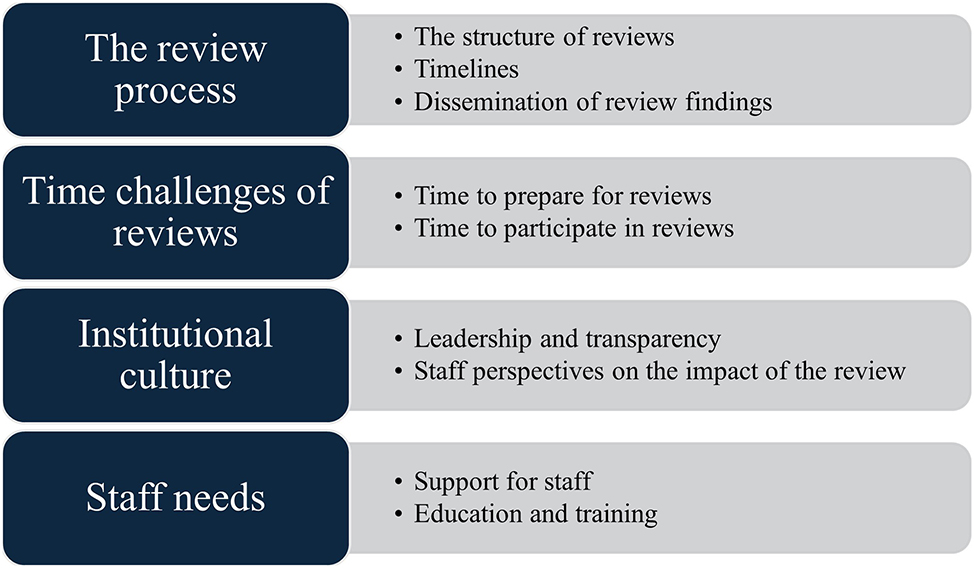

Participants (n=32) included medical and midwifery staff with varying levels of seniority and experience with perinatal mortality reviews. Four themes were identified: the review process, time challenges of reviews, institutional culture and staff needs. Our findings demonstrated that the review process was structured differently across units, with varying levels of staff involvement. Institution culture, leadership and transparency were highlighted as essential aspects of the review process. Reviews have an impact on staff wellbeing, emphasising the need for continued support.

Conclusions

Implementing a standardised perinatal mortality review system is viewed positively by staff, though addressing the highlighted barriers to change is important. A standardised perinatal mortality review tool and review process may help strengthen perinatal death reviews, provide more information and opportunity for involvement for bereaved parents and help reduce future perinatal deaths.

Introduction

The death of a baby before, during or soon after labour is one of the most devastating events that can happen to parents and their families [1]. Perinatal mortality is defined as stillbirths and neonatal deaths occurring within the first seven days of life. Globally, 1.9 million babies were stillborn in 2021, and 2.3 million babies died within the first 20 days of life in 2022 [2], 3]. Compared to under-five child mortality, the perinatal mortality rate (PMR) has been slower to decline [2], 4]. There has been a longstanding focus internationally on perinatal death audits, with particular emphasis in recent years on the reduction of preventable perinatal deaths [5]. One way of achieving this is conducting perinatal mortality reviews [6].

A perinatal mortality review programme can be defined as “the systematic, critical analysis of the quality of perinatal care, including the procedures used for diagnosis and treatment, the use of resources and the resultant outcome and quality of life for women and their babies” [7]. Although the words “audit” and “review” are used interchangeably throughout the literature on the topic, we use the term “audit” to describe perinatal mortality data collection, and “review” to describe a structured analysis conducted “using best practice methods, to determine what happened, how it happened, why it happened, and whether there are learning points for the service, wider organisation, or nationally” [8].

In Ireland, the PMR in 2022 was 5.31 per 1,000 births [9]. This rate has largely remained unchanged since 2012 [9]. Guidance on the management, investigation and reporting of serious reportable events (SREs), which are defined as “serious, largely preventable patient safety incidents that should not occur if the available preventative measures have been implemented by healthcare providers” has existed in Ireland since 2015 [10]. This guidance was updated with the publication of the Incident Management Framework (IMF) in 2020 [8]. Despite this, previous research demonstrates that the approach to review of perinatal deaths is not uniform across Irish maternity units [11]. Other countries have successfully implemented a standardised perinatal death review programme, with some incorporating a review tool to help standardise reviews nationally [12]. Introduction of a standardised perinatal death review programme in Ireland would involve restructuring the existing review process in maternity units.

A strong implementation strategy is paramount to the ongoing success, maintenance and longevity of any intervention in healthcare. The pre-implementation phase of an intervention is as important as the implementation phase itself, and identifying barriers and facilitators is a vital component to the development of a successful implementation strategy [13], 14]. Perinatal death reviews can have a significant impact on bereaved parents [15]. In an Irish context, a qualitative study with bereaved parents reported that some parents were unaware that a review of their baby’s death occurred [16]. Others felt that their feedback and questions were not considered appropriately by the hospital during their review [16]. The impact of reviews on the staff who are involved in providing care for women who have experienced a perinatal death is less well described.

The aim of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a standardised perinatal mortality review process and review tool in Irish maternity units by engaging with healthcare professionals working in the maternity services.

Materials and methods

Setting

Maternity care in Ireland is provided in 19 maternity units or hospitals. These units are coordinated into six hospital groups, with each group having a lead unit that provides tertiary level clinical care and clinical governance to the smaller units within the group. Most women receive their maternity care through a publicly-provided system of combined care between the maternity hospital and their general practitioner.

Perinatal death reviews are not standardised in Ireland. The IMF advises that perinatal deaths should be reported within 24 h of their occurrence and a decision made regarding whether a review of the event is appropriate within 72 h of the death [8]. This review is often led by a Serious Incident Management Team (SIMT), a multidisciplinary team which is the structure suggested by the IMF [8]. Many units have a SIMT set up onsite, however some smaller units refer cases to a hospital group-level SIMT. Of note, participants frequently used the acronym “SIMT” to refer to a review throughout this study. As a result, both terms were used interchangeably by the participants and researchers during the study.

Reflexivity

The primary researcher in this study EOC, is a white woman and a trainee in obstetrics and gynaecology. She had previously worked directly with some of the participants in this study. Her lived experience with working in the field of obstetrics and gynaecology as well as direct experience with caring for women and families who experienced the death of their baby informed her positioning for this study.

Participants

Participants were recruited from three maternity units, representing a mixture of small, medium, and large-sized units. Each was in a different geographical region and associated with a different hospital group. Participants identified with knowledge or experience with perinatal deaths or perinatal death reviews were recruited purposefully for this study (purposive sampling). These participants were asked to assist in identifying other potential participants for the study (snowball sampling). Potential participants were invited to participate by email or direct contact via the study authors and their professional networks. The inclusion criteria included healthcare professionals working in the maternity services, who were required to be fluent in English and had to be over the age of 18. Participants were asked for written, informed consent by one of the study researchers (EOC) prior to the interview. Ethical approval was granted for this study by three separate research Ethics Committees associated with each unit (ECM 4[a] 05.04.2022, C.A. 2827, 056/2022).

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out in person at a place and time suitable for participants. A topic guide was used at the interviews, containing questions about the existing perinatal death review process in the unit and proposed changes to the review process, including the introduction of a perinatal death review tool. A pilot interview was done under direct supervision for training purposes. Detailed reflective notes were taken throughout the interview process and discussed in a team setting before and after the interviews were conducted. The interviews lasted between 21 and 72 min, were recorded using a Dictaphone and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were anonymised and imported into Nvivo14 for analysis.

Data analysis

Transcripts were analysed according to the reflexive thematic analysis framework developed by Braun and Clarke [17]. Data analysis was led by EOC. Data familiarisation occurred primarily through listening back over interviews, taking reflective notes and transcribing verbatim. Transcripts were then read through for further familiarisation and to ensure accuracy. Initial codes for the analysis were developed by EOC. Two additional researchers (AH and SL) read and coded between three and 10 transcripts each, which were then analysed together by the team to ensure consistency across code development. Two researchers spent time developing initial themes, which stemmed from the coding process. At each stage of the analysis, team discussion facilitated theme development and refinement until consensus was reached regarding themes and subthemes.

Results

In total, 32 interviews were conducted across three maternity units between May to December 2022. We included data from all 32 interviews in our analysis. Participants represented a variety of staff members from the maternity services, including consultants in obstetrics and gynaecology (n=6), consultants in neonatology (n=2), doctors-in-training in obstetrics and gynaecology (n=3), doctors-in-training in neonatology (n=1), directors of midwifery (n=2), assistant directors of midwifery (n=2), staff midwives (n=2), midwifery or neonatal nurse managers (n=9), risk or quality and patient safety [QPS] officers (n=3), patient liaison officer (n=1) and pastoral care (n=1). Quotes presented from the interviews are demarcated by the level of seniority of that participant, with one being junior, two mid-management level and three senior level. To preserve the anonymity of the maternity units, units will be referred to by number (1, 2 and 3).

We generated four themes with nine associated subthemes (Figure 1). The themes are representative of the review process, the effects of institutional culture on the review process and the impact of the process on staff.

Themes and subthemes.

Theme: The review process

During each interview, the structure of the review process was discussed. The authors’ understanding of how the system worked in each unit was developed based on these discussions. Some participants had more insight into the system’s structure than others; these participants were often in more senior roles. The subthemes that follow describe the functional aspect of the review system in the three units.

Subtheme: The structure of reviews

The review process was structured differently in each unit. In unit 1, perinatal deaths were initially discussed at a SIMT meeting, which was usually convened within hours to days of the death. The SIMT meeting was attended by the same staff members. Following this meeting, the team decided whether a case required an internal or external review and delegated specific staff members to conduct the review (Table 1, Quote 1). One participant reported that finding reviewers for internal reviews was dependent on staff agreeing to participate (“there would be a number of consultants who would be part of the investigating team, some would be more obliging than others to be sitting on those ah, investigations” Interview 15, level 3, see also Supplementary Material, Quote 1). Sometimes it was deemed necessary to interview involved staff members as well as the bereaved parents as part of the review, though this varied depending on the circumstances of the perinatal death (“it’s not immediately obvious that in the beginning of doing a review how much you need to dig in and say for example what we’d like to do is interview the parents first because what they say might be completely different to what’s documented in the notes and so you know therefore that you need to do a lot more digging around”, Interview 15, level 3).

Theme “The review process”.

| Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Structure of reviews |

|

| Timelines |

|

| Dissemination of findings |

|

-

aA labour ward huddle is defined as “a short, focussed briefing which brings together representatives from across key staff groups to identify potential problems or safety issues, such as challenges to the safe flow of patients across a department or hospital” (Shanmugalingam et al., 2019).

In unit 2, all perinatal deaths were referred initially to the QPS team before a decision was made with the senior management team to progress the case to a SIMT for review. The timing of the SIMT meeting following the perinatal death varied from days to months. The SIMT meeting was scheduled every two weeks, though sometimes it did not happen if various team members were on leave (Table 1, Quote 2). The meeting was attended by the same staff members each time who were part of the hospital’s risk management team. The meeting was attended by consultants in obstetrics and gynaecology and neonatology on a rotating basis. Some participants from this unit reported being asked to attend a SIMT meeting at short notice (“I’d have been invited to be part of SIMT meeting, um usually fairly short notice I would say. Um, and requesting presence on a specific day of the week at a specific time, which I have found difficult to accept because it could be clashing with a clinic that I’m running”, Interview 2, level 3).

In unit 3, perinatal deaths were discussed at a risk meeting locally. This meeting occurred on the same day and time each week and was attended by the same staff members. This was considered an open meeting with other staff welcome to attend if they wished. However, it seemed that junior staff members rarely attended (Table 1, Quote 3). Each perinatal death was also discussed at a hospital group-level SIMT meeting. Occasionally the SIMT would determine that an external review was required; the need for this referral was assessed on a case-by-case basis (Table 1, Quote 4).

Subtheme: Timelines

The timeframe for conducting a review varied between units. In unit 1, participants mentioned a timeframe of 125 days to conduct and complete a review, which is in keeping with IMF guidance. Every participant who mentioned this timeframe almost immediately acknowledged how difficult it was to adhere to it (Table 1, Quote 5). These participants spoke about the difficulty in getting the required team members together to review a case, something that is often impacted by staff leave or clinical commitments.

In the other two units, participants discussed the length of time it takes to complete a review from start to finish but they did not mention having to adhere to a specific timeframe. They shared the frustration of the often-protracted review process for staff and the parents who are at the centre of the process (Table 1, Quote 6 and Supplementary Material, Quote 2).

In unit 2, several participants mentioned the frustration associated with the Coronial process. At the request of the Coroner, some perinatal deaths are referred for a Coronial post-mortem examination. Participants reported that waiting for the release of the post-mortem report as well as the conclusion of the Coronial inquiry contributed significantly to the delays with reviews (Table 1, Quote 7 and Supplementary Material, Quote 3).

Subtheme: Dissemination of review findings

All three units described that during the usual review process, the perinatal death was discussed in a multidisciplinary environment and often recommendations were made for changes to or improvements in care. A report was compiled of the review detailing the findings and recommendations. Participants in senior positions or who had direct involvement with reviews had more knowledge about the dissemination of review findings than junior participants.

The dissemination of findings, recommendations and associated reports from reviews varied, with no defined structure in any unit. Participants discussed the methods that they were aware of to provide feedback to staff in each unit regarding the findings of a review. Many participants, but particularly junior participants, were uncertain about where or how the findings or report from a review were disseminated. In units 2 and 3, the dissemination process seemed to be largely informal and communicated by word of mouth between senior and junior staff members (Table 1, Quote 8 and Supplementary Material, Quote 4).

In contrast, the dissemination process in unit 1 appeared to have more structure but participants recognised that it was an imperfect system (Table 1, Quote 9 and Supplementary Material, Quote 5). Some participants expressed their frustration with the lack of structure for dissemination. Many participants felt that dissemination of review findings to staff was inadequate (Table 1, Quote 10). This was viewed by participants as the responsibility of the staff who are directly involved in the review process (“we need somebody who’s going to institute or implement recommendations that come from SIMTs and say look, we should be doing this differently or you know, in a very constructive way”, Interview 2, level 3). Participants thought that the unstructured manner of communicating the findings from a review was contributing to missed opportunities for sharing the learning that can be obtained from reviewing perinatal deaths (Table 1, Quote 11 and Supplementary Material, Quote 6).

Theme: Time challenges of reviews

Preparing for and participating in reviews and writing reports following a review represented a significant workload for staff. There are many elements to postpartum care following the death of a baby, including clinical care for the mother, bereavement care for the family, arranging clinical tests and funeral arrangements for the baby. Communicating with parents about the review of their care as well as seeing to these other needs requires time.

Subtheme: Time to prepare for reviews

The time constraints that the review process places on staff involved in conducting reviews was mentioned repeatedly. Participants discussed the time required to prepare for participating in a review, time that is often taken out of an over-subscribed clinical schedule, which may affect other clinical commitments, detracting from the care they provide to other women (“It can be difficult if you’re leaving one aspect of your job to participate [in a review] and I think it probably should be more structured from a time perspective, or you should have protected time to review the cases that are going to be discussed”, Interview 2, level 3).

Participants mentioned the difficulty of preparing for a review with little or no notice prior to the meeting being scheduled. In unit 2, the scheduling of review meetings was described as unpredictable. Participants in this unit reported that the meetings did occur regularly, but the day and time they were scheduled differed each time and staff were usually given very little notice to prepare for these. This often led to participants having to reschedule or drop other commitments to prepare for and attend a review meeting (Table 2, Quote 1).

Theme: “Time challenges of reviews”.

| Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Time to prepare for reviews |

|

| Time to participate in reviews |

|

Subtheme: Time to participate in reviews

Participants mentioned that they did not have enough time assigned to participate in the review and complete the related reports and further documentation stemming from it. In some cases, participants mentioned that a review might prompt a report to be written on a particular topic or time might be required to provide written answers to questions from parents. These commitments require the participants’ time to complete them, and apart from participants who were members of the risk management team in their units, no other participant had designated time in their normal clinical schedule to complete tasks after the reviews (Table 2, Quotes 2 and 3).

Theme: Institutional culture

The underlying culture of a unit significantly influenced the review process. Both direct and subtle references were made by participants about the culture in their unit. This was evident in the way participants discussed the review process. Some spoke very positively about reviews (“I think it’s to develop that whole culture that it’s about support and learning as opposed to the blame”, Interview 20, level 2), while others had more negative opinions (“I do think in my experience of working with reviews and around quality and risk, people are very suspicious of what’s going to be done with the information [from reviews]. I mean I certainly would’ve done a lot of work in trying to build up trust with people and explain that this is about all of us learning together, it’s not about pointing the finger at anybody”, Interview 8, level 3). “Blame culture” was a concept mentioned by several participants.

Two participants were concerned that there would be consequences for speaking poorly about the review process and those involved in it. These participants were reluctant to elaborate any further on this topic after it was mentioned (Table 3, Quote 1). Participants mentioned the distress associated with being involved in a perinatal death and subsequently being involved in a review for the death. The opinions of participants about the review system seemed connected to their perception of the underlying workplace culture in their unit (Table 3, Quote 2 and Supplementary Material, Quote 7).

Theme: “Institutional culture”.

| Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Leadership and transparency |

|

| Staff perspectives on the impact of the review |

|

Subtheme: Leadership and transparency

Participants in senior roles knew more about reviews and how they are structured, whereas participants in junior roles did not have the same knowledge or awareness of the review process. Some participants described a superficial knowledge of reviews while others were not aware that a review process existed in their unit (Table 3, Quote 3). Many aspects of the review process were viewed as being influenced by the clinical leadership in the unit. Some participants perceived a positive leadership culture resulting in a robust review process (“In this hospital we would really have a good, open, transparent culture where the intention is to look and find if there is something that we need to improve on”, Interview 16, level 2). This was particularly evident in unit 1.

In the other two units, participants discussed the interdependent nature of leadership and culture within a unit on the review process (Table 3, Quote 4), and the effect this had on them and their colleagues (“I think maybe it’s the culture of leadership within the hospital that’s not really emphasizing that [reviews] are really important and that we can learn from them. And in fact the only time I feel that actually we all know about it is if there’s a national body coming in”, Interview 5, level 3).

In unit 2, the review process was described by some participants as being secretive or opaque, with participants using phrases such as “cloak of secrecy” or “mystic forum” to describe what happens in the meetings when reviews occur (Table 3, Quote 5). Most participants spoke about the importance of being open and transparent with all staff members about reviews in their unit and said that this transparency should be promoted by senior management.

Subtheme: Staff perspectives on the impact of the review

Some participants spoke about the effects that perinatal deaths and reviews had on their colleagues’ ability to be at work. Some described staff absences secondary to dealing with SREs (Table 3, Quote 6 and Supplementary Material, Quote 8), and other participants discussed the long-term impact of SREs on staff. Some participants said that a bad outcome had prompted their colleagues to leave the maternity services altogether (“People are doing their job, but it’s devastating for them as professionals and of course it’s much more devastating for the families, however I have seen colleagues down through the years, it has changed their careers and they have given up really good careers”, Interview 8, level 3).

One participant in a senior role described their struggle at times with how to approach junior staff members to discuss their involvement in an adverse incident and provide feedback to them after a review (Table 3, Quote 7). The emotional distress that can be associated with reviews was mentioned by many participants, but this was often contrasted with the perceived value of the review process. Participants spoke about a sense of duty towards the women and babies they look after and wanted to find answers for parents about why their baby died. They spoke about the importance of the learning that comes from reviewing adverse outcomes, and how this learning is beneficial for their own practice and education as well as that of their colleagues (Supplementary Material, Quote 9). The need to apply this learning to prevent future perinatal deaths was emphasized (Table 3, Quote 8).

Theme: Staff needs

Participants highlighted different needs that they felt were important to staff who have any exposure to perinatal deaths. This included providing support for staff members in the form of peer-to-peer support and general support from senior management. Participants emphasised the need for education and training about the structure of the review process, why reviews are required and how to speak with parents about reviews.

Subtheme: Support for staff

Support for staff after a perinatal death occurs and during the review that follows was mentioned by many participants. Some mentioned feeling quite unsupported, while others felt that they were very well supported in the aftermath of a perinatal death (Table 4, Quote 1 and Supplementary Material, Quote 10). Several participants mentioned the importance of a “debrief”, which is a concept of “guided meetings, during which members discuss, interpret and learn from recent clinical events” [18]. Participants who mentioned a debrief appeared to value it as a useful practice for staff to talk through what happened during an SRE and discuss their feelings about the incident (Table 4, Quote 2).

Theme: “Staff needs”.

| Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Support for staff |

|

| Education and training |

|

Two participants mentioned more formal support systems for staff such as the Employee Assistance Programme (EAP), which is a free counselling service available to all HSE employees in Ireland, and Schwartz Rounds, although Schwartz rounds were not in use in any unit where this study was conducted [19]. Interestingly, one of these participants thought that their colleagues viewed the EAP with suspicion and were reluctant to use it in case they got in trouble (“Employee Assistance Programme, yeah, it’s run through occupational health. People are very um, some people are kind of suspicious because they’re saying they’re afraid that, you know, if you go to occupational health and occupational health or EAP will report back to their manager, they don’t. It’s a confidential service…”, Interview 8, level 3).

Subtheme: Education and training

Many participants mentioned the need for education and training about reviews. This was discussed in three different contexts. Firstly, in relation to the need for increased awareness, education, and training for staff members in all maternity units about the review process itself, why reviews are required and how they are conducted (“I think definitely better education for all of us about how the review process works so that when our time does come that we’re involved in the review process that we’re not just learning about it then”, Interview 1, level 1 and see also Table 4, Quote 3 and Supplementary Material, Quote 11). Secondly, several participants expressed frustration regarding the lack of training about how to discuss the structure and function of reviews with parents (Table 4, Quote 4). Thirdly, the learning that can be taken from reviewing perinatal deaths, and the importance of applying this learning to help prevent future deaths was emphasised. Participants viewed this as a critical component of a review to improve their own learning (Table 4, Quote 5, Supplementary Material, Quote 12) and to answer questions and provide closure for parents (Table 4, Quote 6).

Discussion

This study examined the practice for perinatal death reviews in 2022 in three Irish maternity units and identified facilitators and barriers to changing the perinatal death review system to one that is standardised. Our findings highlight important aspects of perinatal death reviews, including how staff perceive reviews and how institutional culture impacts the review system.

The IMF provides guidance on reporting and reviewing a variety of SREs, including perinatal deaths [8]. However, the IMF is not specific for perinatal deaths, and this may be one reason for the observed inconsistency across the units in this study. As highlighted in our findings, each unit has been left to adapt and interpret the IMF according to their needs and understanding. This suggests that lack of standardisation involves every Irish maternity unit, resulting in a disparate review process for parents depending on what unit they attend for their care. The inconsistency in reviews may also contribute to missed learning opportunities from perinatal deaths.

The lack of standardisation in death reviews has been highlighted as problematic in other countries [12], 20]. A report on the investigation of deaths among people with mental health illness or disability in the NHS found there was no framework to conduct such reviews, resulting in missed opportunities to maximise the learning from a potentially preventable death, to improve care and prevent future deaths [21].

Lack of structure represents a significant barrier towards standardising perinatal mortality reviews. Guidance is available for implementing perinatal mortality reviews from the WHO and some countries have successfully implemented standardised review programmes at national or local levels [6], 12]. The perinatal mortality review tool (PMRT) programme in England uses a standardised tool to review perinatal deaths [22]. Data is collated across the NHS and an annual report of review findings is published, allowing for shared learning and recommendations on ways to reduce perinatal deaths [22]. The PMRT programme was introduced concurrently with several other initiatives to reduce perinatal deaths in the UK, and these combined efforts resulted in a 20 % reduction in extended perinatal mortality in the UK between 2013 and 2020 [23], [24], [25].

Time constraints were mentioned frequently by study participants. Protected time to participate in reviews was rarely available, which caused difficulties for staff members with busy clinical schedules. Review at institutional level should incorporate protected time for staff members [6]. As suggested by study participants, having a regularly scheduled review meeting would allow staff members to incorporate the meeting into their clinical schedules. Another solution might be to have a set rota for participation from senior or management-level staff in the review process. Allowing protected time places a greater emphasis on the importance of perinatal death reviews and may reduce some of the pressure for the staff involved.

Another challenge was the timeframe to complete a review. Only one unit mentioned a specific timeframe of 125 days (suggested by the IMF) and these participants highlighted the unrealistic nature of this timeframe [8]. These delays were compounded further when a perinatal death was referred for Coronial investigation. The legislation regarding which cases must be discussed with the Coroner changed with the Coroner’s (Amendment) Act in 2019 [26]. Many perinatal deaths are now directed by the Coroner to have a coronial post-mortem examination, causing further delays as many hospital review teams wait for the release of the coronial post-mortem report and the conclusion of the coronial inquiry before concluding their review. In some cases, the coronial process has become so protracted the benefit it provides to the families and hospitals involved remains unclear and there have been calls to reform the entire coronial system [27].

Dissemination of review findings and feedback to staff occurred formally and informally in this study and, in some cases, participants did not receive any feedback from reviews. Similarly, a previous study from an English maternity unit reported that most participants did not receive feedback from reviews they were involved in, which contributed to a lack of trust in the local risk management process [28]. Providing feedback using multiple methods improves uptake and implementation by staff [8], 29]. Care needs to be taken to prevent defensive reactions to negative feedback and ensure this is provided in a constructive manner [30]. A framework for providing feedback to individual staff members as well as generalised feedback to the unit may be a helpful facilitator for implementing changes following a review.

It was evident from our study that an institution’s culture has a far-reaching impact on the review process. There were noticeable differences in participants’ opinions of reviews in each unit. This may be explained by the differences in leadership styles and attitudes towards reviews. Participants in one unit felt reviews were exclusionary and secretive and they worried about the negative effects that reviews might have on themselves or their colleagues. Indeed, some participants were reluctant to voice any negative opinions in relation to reviews, fearing that it may get them into trouble with other colleagues. In stark contrast, participants in another unit felt reviews were well conducted, and there was a sense of pride from these participants when speaking about reviews in their unit.

“Blame culture” is closely linked to institutional culture and this topic was mentioned by participants in all units, indicating that blame culture is still pervasive at least in these units and possibly other Irish maternity units. This finding is particularly concerning, as a culture of blame can have serious consequences on the implementation and ongoing success of the review system and can foster fears of punishment or litigation [31], [32], [33]. There have been efforts within the Irish healthcare system to develop a “just culture” instead, defined as a “values based supportive model of shared accountability” [8]. Importantly, individuals are held accountable for their own decisions but not for system-level failings over which they have no control [34]. Developing a blame-free culture in this setting is essential for deeper understanding of SREs and associated system failures [35]. Balancing between a blame-free culture and accountability is dependent in many ways on the leadership in a unit, as evidenced in our findings. Educating leadership about just culture practices is key to ensuring a just culture and blame-free environment for the staff working in that setting. Other key features of strong leadership that contribute to learning and improvement within a unit include a strategic leadership that engages with staff, and demonstrates visible support, recognition and listening [36].

Bereaved parents are central to the review process; however, reviews also focus quite extensively on the staff who were involved in providing care to the family. When caring for parents whose baby has died, staff have reported feelings of sadness, shock, emotional distress, self-blame and guilt [37], 38]. Similar feelings were also reflected in these interviews. It was evident from our analysis that being involved in reviews can be associated with significant mental distress for staff, and this phenomenon is less widely reported in the literature.

Participants emphasised the need for adequate staff support after a perinatal death and the subsequent review that follows. Many staff utilised informal arrangements, such as turning to their colleagues for support in the aftermath of an adverse event, as previously reported in other studies [39], 40]. The HSE offers support for staff in the form of the EAP, which was mentioned by staff in all units. One senior level participant in our study felt that staff in their unit viewed this programme with suspicion and mistrust. As one of the only formal supports available for staff in these units, this is problematic, as staff may not feel comfortable accessing the programme in the aftermath of an SRE.

Participants viewed support for staff as an important facilitator for reviews and multiple support methods should be available [40]. This includes mentoring, peer-to-peer support, group-based peer support such as the concept of debriefing or Schwartz rounds, or counselling [19], 41]. Previous studies have demonstrated a lack of support specifically for staff dealing with the complexities of perinatal death [37], 38]. Staff members working in the maternity services would benefit from clear, structured support that includes resources for coping with perinatal death and subsequent reviews, like existing supports available in the UK [42]. A supportive work environment may help with staff wellbeing, resilience and retention [43], 44].

Lack of transparency about reviews was reported as a significant barrier. Some participants knew nothing about reviews, even though their professional practice may be subject to a review at some point during their career. A hospital review forms a considerable part of a family’s bereavement care journey, yet some participants expressed uncertainty about how to discuss reviews with parents. Participants felt improved education and training about reviews was a facilitator for implementing standardised reviews. Targeted education programmes have significantly improved participants’ confidence and knowledge in other areas of bereavement care [45], 46]. Based on the discussions with participants, specific training for reviews should include information about how reviews work, what a review means for parents and for staff, and how to counsel parents about reviews. Leadership training should be considered for senior staff members to encourage open dialogue and transparency about incident reporting and reviews. While participants’ perceptions about reviews were clearly influenced by the underlying culture within their unit, they strongly emphasised the importance and value of perinatal death reviews. They were overwhelmingly in favour of standardising reviews to improve learning from perinatal deaths and ensure a more equitable and transparent system for parents.

This study provided important insights into the way perinatal death reviews are conducted in an Irish context. Reviews are not being conducted in a standardised manner within or between units, paving the way for unstructured and ambiguous reviews. This is creating missed opportunities for learning from potentially preventable perinatal deaths at local and national levels. Having protected time to participate in reviews, regular dissemination of review findings, and a transparent review process are important considerations for standardisation. Units should ensure that staff are educated about reviews. Adequate support systems should be in place to help staff after adverse events and during reviews. Underpinning all of this is an institution’s culture and leadership approach. Both are highly impactful on how incident reporting and reviews are conducted and perceived by staff. The suggested changes to the review system based on the findings from this study are outlined in Table 5. It is essential that these barriers and facilitators are addressed to ensure successful implementation of a standardised review system.

Suggested changes to the review system based on the findings from this study.

| Suggested change | Further detail |

|---|---|

| Standardised review system | A standardised review tool for use at national level in every maternity unit in Ireland to review perinatal deaths, in a structured and equal manner. |

| Protected time for staff to participate in reviews | Having protected time for reviewers, especially for those who regularly participate in reviews, is important to facilitate timely and thorough reviews. Time should be allocated for review preparation and review participation. |

| Regular training for senior leadership (clinical and non-clinical) on creating a blame-free, just culture | Workplace culture is typically fostered by senior leadership in a unit. Creating a blame-free environment where staff are comfortable reporting adverse incidents and participating in reviews is important for the review process. Within this setting, a just culture advocates for individual responsibility without accountability for system-level failures. |

| Formalised feedback pathways to individual staff members (where applicable) and the wider unit following the conclusion of a review | Providing feedback to staff was highlighted as a facilitator to the review process and promotes transparency about reviews. Feedback may prompt discussion about system-level changes required to improve the maternity services. |

| Support for staff | Support pathways for staff following a perinatal death should include peer-to-peer support, group-based support and individual support such as counselling. |

| Staff training on the review system | Providing regular education, training and awareness to maternity staff about the review system, why reviews are required and what a review entails. |

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind exploring the views of staff about perinatal death reviews in Ireland. Participants were representative of the various staff members, including different managerial levels, working in the maternity services. We intentionally interviewed participants from three different sized units around the country to make our findings as generalisable as possible.

A limitation is the self-selection of participants in this study, which may have influenced the views and experiences reported in the interviews. Although the units in this study represented three different regions and hospital structures, other maternity units around the country are likely to be structured slightly differently, which poses an additional limitation. Most of the participants in this study were in more senior roles and had worked in their unit for longer than more junior-level colleagues. Finally, this study took place during the third year of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a particularly challenging period for healthcare staff, and memories of the difficult working conditions may have been to the fore of participants’ minds, possibly affecting the interviews.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated a perinatal mortality review system that is not standardised or transparent. The underlying institutional culture significantly influences the way reviews are conducted and perceived by staff members in each unit. Support for staff who are involved in reviews is extremely important, as reviews may be associated with emotional distress and trauma for staff.

Standardising reviews by using, for example, a review tool for perinatal deaths may help create more structured, transparent reviews. This may lead to a more equitable experience for parents, who should be at the centre of reviews, as well as for staff working in the maternity services, ensuring implementation of best-practice and high-quality care nationwide. Ultimately, standardising the review system may lead to improved learning from perinatal deaths and may help to decrease the rate of perinatal deaths in Ireland.

Funding source: Feileacain, the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Association of Ireland

Award Identifier / Grant number: There is no grant number associated with this fund

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to all study collaborators who kindly helped with participant recruitment in each unit where this study took place. We would also like to thank the study participants who gave their valuable time and opinions to participate in this study.

-

Research ethics: Ethical approval was sought and granted from the three separate research Ethics Committees associated with each unit where this study was conducted. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study. The Ethics Committee approval codes are listed below: ECM 4 (a) 05.04.2022, C.A. 2827, 056/2022.

-

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Emily O’Connor’s PhD studentship is philanthropically funded by Féileacáin, the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Association of Ireland. Féileacáin did not have any part in the conception, design, planning or conduct of this project.

-

Data availability: The transcripts from this study have not been published in order to preserve the anonymity of the study participants.

References

1. WHO. Making every baby count audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. [Internet]; 2016. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/249523/9789241511223-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

2. UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Levels & trends in child mortality: report 2022. [Internet]; 2022. https://childmortality.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/UN-IGME-Child-Mortality-Report-2022.pdf [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

3. World Health Organization. Newborn mortality. [Internet]; 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality [Accessed 4 Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

4. de Bernis, L, Kinney, MV, Stones, W, ten Hoope-Bender, P, Vivio, D, Leisher, SH, et al.. Stillbirths: ending preventable deaths by 2030. Lancet 2016;387:703–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00954-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Flenady, V, Wojcieszek, AM, Middleton, P, Ellwood, D, Erwich, JJ, Coory, M, et al.. Stillbirths: recall to action in high-income countries. Lancet 2016;387:691–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01020-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. WHO. Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response: materials to support implementation. [Internet]; 2021. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/348487/9789240036666-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

7. Dunn, P, McIlwaine, G. Perinatal audit: a report produced for the European Association of Perinatal Medicine. New York, New York: Parthenon; 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

8. HSE. Incident management framework. [Internet]; 2020. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/nqpsd/qps-incident-management/incident-management/hse-2020-incident-management-framework-guidance.pdf [Accessed 10 Jul 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

9. San Lazaro Campillo, I, Manning, E, Corcoran, P, Keane, J, McKernan, J, Greene, R. Perinatal mortality national clinical audit in Ireland annual report 2022. [Internet]. Cork; 2024. https://www.ucc.ie/en/media/training-2024/trainingacademia190/PerinatalMortalityFormReport2022-3526AW.pdf [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

10. HSE. Serious reportable events implementation guidance document. [Internet]. Dublin; 2015. Available from https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/nqpsd/qps-incident-management/incident-management/sre-guidance-january-2015-v1-.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Helps, A, Leitao, S, O’Donoghue, K, Greene, R. Perinatal death notification and local reviews in the 19 Irish maternity units. Ir Med J 2019;34:52.Suche in Google Scholar

12. O’Connor, E, Leitao, S, Fogarty, AP, Greene, R, O’Donoghue, K. A systematic review of standardised tools used in perinatal death review programmes. Women Birth 2024;37:88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2023.09.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Damschroder, LJ, Reardon, CM, Widerquist, MAO, Lowery, J. The updated consolidated framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement Sci 2022;17:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Belizán, M, Bergh, AM, Cilliers, C, Pattinson, RC, Voce, A. Stages of change: a qualitative study on the implementation of a perinatal audit programme in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:243. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-243.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Bakhbakhi, D, Siassakos, D, Burden, C, Jones, F, Yoward, F, Redshaw, M, et al.. Learning from deaths: Parents’ Active Role and ENgagement in The review of their Stillbirth/perinatal death (the PARENTS 1 study). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1509-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Helps, Ä, O’Donoghue, K, O’Connell, O, Leitao, S. Bereaved parents involvement in maternity hospital perinatal death review processes: ‘nobody even thought to ask us anything’. Health Expect 2023;26:183–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13645.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Braun, V, Clarke, V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide, 1st ed. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2021.10.53841/bpsqmip.2022.1.33.46Suche in Google Scholar

18. Kolbe, M, Schmutz, S, Seelandt, JC, Eppich, WJ, Schmutz, JB. Team debriefings in healthcare: aligning intention and impact. BMJ 2021;374:n2042. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2042.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. The Point of Care Foundation. About Schwartz rounds. [Internet]. https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/our-programmes/staff-experience/about-schwartz-rounds/ [Accessed 9 Jul 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

20. Helps, A, Leitao, S, Greene, R, O’Donoghue, K. Perinatal mortality audits and reviews: past, present and the way forward. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;250:24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.054.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Care Quality Commission. Learning, candour and accountability a review of the way NHS trusts review and investigate the deaths of patients in England. [Internet]; 2016. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20161213-learning-candour-accountability-full-report.pdf [Accessed 7 Aug 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

22. Krusche, A, Smith, P, Bevan, C, Burden, C, Drain, R, Draper, ES, et al.. Learning from standardised reviews when babies die. National perinatal review tool: sixth annual report. [Internet]; 2024. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/pmrt/reports/report-2024/PMRT%20Report%202024%20-%20Main%20Report.pdf [Accessed 17 Dec 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

23. RCOG. Each baby counts: 2020 final progress report [Internet]. London: 2021 https://www.rcog.org.uk/media/a4eg2xnm/ebc-2020-final-progress-report.pdf [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

24. O’Connor, D. Saving babies’ lives a care bundle for reducing stillbirth. [Internet]; 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/saving-babies-lives-car-bundl.pdf [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

25. Draper, E, Gallimore, I, Smith, L, Matthews, R, Fenton, A, Kurinczuk, J, et al.. MBRRACE-UK perinatal mortality surveillance report. [Internet]; 2022. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/mbrrace-uk/reports/perinatal-surveillance-report-2020/MBRRACE-UK_Perinatal_Surveillance_Report_2020.pdf [Accessed 7 Aug 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

26. Government of Ireland. Coroner’s (Amendment) Act. [Internet]. Ireland; 2019. https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2019/act/29/enacted/en/pdf [Accessed 29 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

27. Scraton, P, McNaull, G. Death investigation, Coroners’ inquests and the rights of the bereaved. [Internet]. Dublin; 2021. Available from: https://www.iccl.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ICCL-Death-Investigations-Coroners-Inquests-the-Rights-of-the-Bereaved.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Olagundoye, V, Quinlan, M, Burrow, R. Stress, anxiety, and erosion of trust: maternity staff experiences with incident management. AJOG Glob Rep 2022;2:100084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xagr.2022.100084.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Brehaut, J, Colquhoun, H, Eva, K, Carroll, K, Sales, A, Michie, S, et al.. Practice feedback interventions: 15 suggestions for optimizing effectiveness. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:435–41. https://doi.org/10.7326/m15-2248.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Wenzel, L, Jabbal, J. User feedback in maternity services. [Internet]. London; 2016. https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/5c0fd320f8/user_feedback_maternity_oct_2016.pdf [Accessed 30 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

31. Lewis, G. The cultural environment behind successful maternal death and morbidity reviews. BJOG 2014;121:24–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12801.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. British Medical Association. Caring, supportive, collaborative doctors’ vision for change in the NHS summary report. [Internet]; 2019. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/3908/bma-csc-future-vision-nhs-report-sept-19.pdf [Accessed 6 Aug 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

33. Kinney, MV, Walugembe, DR, Wanduru, P, Waiswa, P, George, A. Maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review of implementation factors. Health Policy Plan 2021;36:955–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Hughes, S. The development of a just culture in the HSE [Internet]. Elsevier B.V.; 2022. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/nqpsd/qps-incident-management/just-culture-overview.pdf [Accessed 30 Jan 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

35. Kinney, MV, Day, LT, Palestra, F, Biswas, A, Jackson, D, Roos, N, et al.. Overcoming blame culture: key strategies to catalyse maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response. BJOG 2022;129:839–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16989.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. de Kok, K, van der Scheer, W, Ketelaars, C, Leistikow, I. Organizational attributes that contribute to the learning & improvement capabilities of healthcare organizations: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023;23:585. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09562-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Nuzum, D, Meaney, S, O’Donoghue, K. The impact of stillbirth on consultant obstetrician gynaecologists: a qualitative study. BJOG 2014;121:1020–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12695.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. McNamara, K, Meaney, S, O’Donoghue, K. Intrapartum fetal death and doctors: a qualitative exploration. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:890–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13354.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Horne, IMT, Veggeland, F, Bååthe, F, Isaksson, RK. Why do doctors seek peer support? A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e048732. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048732.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Wilkie, T, Tajirian, T, Stergiopoulos, V. Advancing physician wellness, engagement and excellence in a mental health setting: a Canadian perspective. Health Promot Int 2022;37:daab061. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab061.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Brazeau, CMLR, Trockel, MT, Swensen, SJ, Shanafelt, TD. Designing and building a portfolio of individual support resources for physicians. Acad Med 2023;98:1113–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000005276.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Jacobson, B. Maternity services resources hub. [Internet]; 2024. brownejacobson.com/maternity-services [Accessed 17 Sep 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

43. Mahat, S, Lehmusto, H, Rafferty, AM, Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K, Mikkonen, S, Härkänen, M. Impact of second victim distress on healthcare professionals’ intent to leave, absenteeism and resilience: a mediation model of organizational support. J Adv Nurs 2024;00:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.16291.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Christoffersen, L, Teigen, J, Rønningstad, C. Following-up midwives after adverse incidents: how front-line management practices help second victims. Midwifery 2020;85:102669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102669.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Leitao, S, Helps, A, Cotter, R, O’Donoghue, K. Development and evaluation of TEARDROP – a perinatal bereavement care training programme for healthcare professionals. Midwifery 2021;98:102978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2021.102978.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Gardiner, PA, Kent, AL, Rodriguez, V, Wojcieszek, AM, Ellwood, D, Gordon, A, et al.. Evaluation of an international educational programme for health care professionals on best practice in the management of a perinatal death: IMproving Perinatal mortality Review and Outcomes via Education (IMPROVE). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:376. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1173-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2024-0601).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Vasa previa guidelines and their supporting evidence

- Fetal origins of adult disease: transforming prenatal care by integrating Barker’s Hypothesis with AI-driven 4D ultrasound

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Postpartum remote blood pressure monitoring and risk of hypertensive-related readmission: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Proposal of a novel index in assessing perinatal mortality in prenatal diagnosis of Sacrococcygeal teratoma

- Maternity staff views on implementing a national perinatal mortality review tool: understanding barriers and facilitators

- Prenatal care for twin pregnancies: analysis of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality

- Hematological indicators and their impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnancies with thalassemia traits

- The reference ranges for fetal ductus venosus flow velocities and calculated waveform indices and their predictive values for right heart diseases

- Risk factors and outcomes of uterine rupture before onset of labor vs. during labor: a multicenter study

- Feasibility and reproducibility of speckle tracking echocardiography in routine assessment of the fetal heart in a low-risk population

- Enhancing external cephalic version success: insights from an Israeli tertiary center

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Comparative sonographic measurement of the fetal thymus size in singleton and twin pregnancies

- Transversal cardiac diameter is increased in fetuses with dextro-transposition of the great arteries older than 28th weeks of gestation

- Short Communications

- Severe maternal morbidity in twin pregnancies: the impact of body mass index and gestational weight gain

- Trends in gestational age and short-term neonatal outcomes in the United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Mechanisms of hypoxaemia in late pulmonary hypertension associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- Vasa previa guidelines and their supporting evidence

- Fetal origins of adult disease: transforming prenatal care by integrating Barker’s Hypothesis with AI-driven 4D ultrasound

- Original Articles – Obstetrics

- Postpartum remote blood pressure monitoring and risk of hypertensive-related readmission: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Proposal of a novel index in assessing perinatal mortality in prenatal diagnosis of Sacrococcygeal teratoma

- Maternity staff views on implementing a national perinatal mortality review tool: understanding barriers and facilitators

- Prenatal care for twin pregnancies: analysis of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality

- Hematological indicators and their impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnancies with thalassemia traits

- The reference ranges for fetal ductus venosus flow velocities and calculated waveform indices and their predictive values for right heart diseases

- Risk factors and outcomes of uterine rupture before onset of labor vs. during labor: a multicenter study

- Feasibility and reproducibility of speckle tracking echocardiography in routine assessment of the fetal heart in a low-risk population

- Enhancing external cephalic version success: insights from an Israeli tertiary center

- Original Articles – Fetus

- Comparative sonographic measurement of the fetal thymus size in singleton and twin pregnancies

- Transversal cardiac diameter is increased in fetuses with dextro-transposition of the great arteries older than 28th weeks of gestation

- Short Communications

- Severe maternal morbidity in twin pregnancies: the impact of body mass index and gestational weight gain

- Trends in gestational age and short-term neonatal outcomes in the United States

- Letter to the Editor

- Mechanisms of hypoxaemia in late pulmonary hypertension associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia