Abstract

AI is characterized by the features of a general purpose technology and thus has the potential to spur innovation and productivity across sectors. While large digital U.S. companies are dominant players in the development of AI models, Europe is lagging behind. The European Union has agreed on the AI Act in order to allow for innovation, in particular for SMEs, and to prevent harm to society. However, regulation may have ambiguous effects on the state of the digital economy in Europe and of AI in particular. We point out these potential effects and suggest measures to speed up AI development and usage in Europe. We thereby build on recommendations of the Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation (EFI) as well as the Scientific Advisory Board of the German Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action.

1 Europe Is Lagging Behind in AI

General purpose technologies are characterized by a highly dynamic development, have the potential to be used in all economic sectors and to spur innovation and productivity growth (Bresnahan and Trajtenberg 1995). These characteristics apply to digital technologies in general as well as to Artificial Intelligence (AI) (e.g. Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson 2019). In particular generative AI being able to create text, video and programming code on the basis of foundation models (i.e. large language or multi-modal models) imply a great potential for innovation (e.g. EFI 2024).

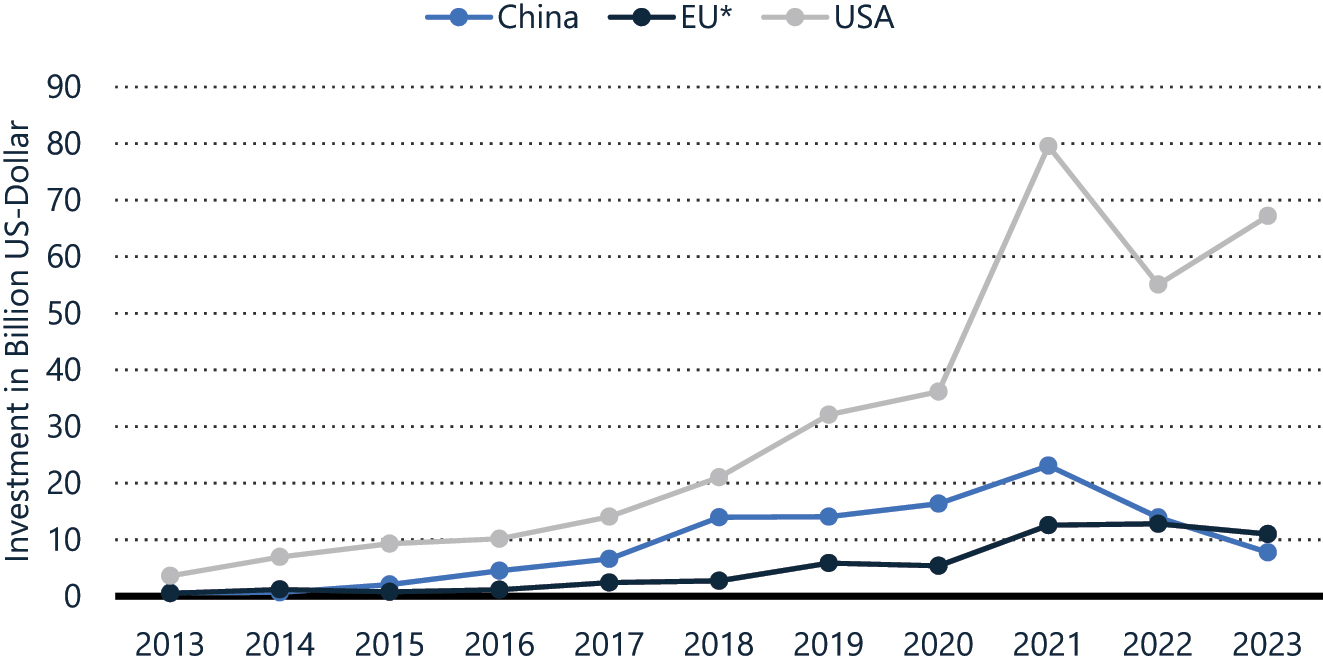

Large US companies such as Microsoft and Google have held dominant positions in the digital platform economy. With their huge computing capacities and the data sets they have collected, they are in a favorable position for developing and applying AI models. Europe, however, is lagging behind. In 2023, private investment in the field of AI amounted to around 11 billion US Dollar in the European Union (including the United Kingdom) and 67 billion US Dollar in the US[1] (see Figure 1). In the field of generative AI, Europe’s (EU-27) share of transnational patent applications was 15 percent in 2020, the share of the US was 33 percent. More than 50 percent of the large language models and multimodal models published in 2022 came from the US (EFI 2024).

Private investment in AI according to regions, 2013 to 2023. Source: Stanford University, NetBase Quid; Statista 2024.

Their computing capacity and data repositories put US companies in an advantageous position for cooperating with AI start-ups. For example, Microsoft cooperates with OpenAI, the start-up that developed ChatGPT, and, more recently, began a cooperation with the French start-up Mistral AI,[2] the leading AI company in Europe. Since working with Microsoft, Open AI stopped providing its model ChatGPT open source. While this kind of cooperation might boost the further development (via infrastructure and investment capacity) and diffusion (via the large user base of US companies) of generative AI, it comes with the risk of market concentration and with European firms falling even further behind. Moreover, there is the risk that AI models and applications will not comply with European values in terms of data protection, privacy and non-discrimination (European Commission 2021). Can European regulation address these risks while supporting catching-up with respect to the development and usage of AI in Europe?

2 European Regulation with Ambiguous Effects

Broadly, European regulation can be sorted into two categories: First, regulation fostering competition. This category refers to measures supporting competition in digital markets, most prominently the Digital Markets Act (DMA), which came into force in 2023. Second, regulation preventing harm. This category refers to interventions with the aim to prevent harmful applications of digital technologies. Examples are the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) from 2016 and, most recently, the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) from 2024 addressing the development and application of AI in Europe. However, both sets of measures may yield ambiguous effects on the state of the digital economy in Europe and of AI in particular.

2.1 Fostering Competition

During the last wave of digitalization the market has concentrated faster than expected on a few dominant players such as Alphabet including YouTube, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook/Meta including Instagram and Twitter, implying a declining momentum. It turned out that the existing abuse control was not sufficient to prevent this trend towards larger concentration. One reason for this was that in the digital sector it takes far too long for competition authorities to implement measures which improve competition in a significant manner, with investigations and lawsuits lasting up to a decade and sometimes even more. As a consequence, at the European level, the DMA was established creating new instruments, such as the ban on self-preferencing. In Germany, the new section 19a of the Act of Restraints of Competition was amended providing more power to the competition authorities for supervision and intervention.

With AI, similar developments can be observed. There are a number of start-ups entering the market with innovative models. However, the dominant US players have advantages with respect to their computing capacities, their data, and their financial resources. Their co-operations with start-ups can be considered as quasi-mergers which might restrict market dynamics further. Similar to search engines or e-commerce platforms, data-driven network effects also play an important role in the context of AI supporting market concentration. Thus, a crucial factor for developing and applying AI is data and access to data. Regulation should ensure that the data from the large digital firms is better available to competitors, in case this data is used as entry barriers.

The DMA aims to achieve interconnectivity and data portability which might limit the market dominance of market players. However, the DMA has only recently come into force. There is still a lack of experience. But there are a few promising signs relating to the ban of self-referencing. For example, according to the DMA, Amazon was designated a gatekeeper by the EU Commission in September 2023 and was thus obliged to limit self-preferencing. As a consequence, the rank differential for Amazon’s own products fell from a 30 position advantage to a 20 position advantage, while other major brands’ rank positions were unaffected (Waldfogel 2024).

2.2 Preventing Harm

For the development and application of AI, the European Union pursues a human-centric approach (EU Commission 2021). The AI Act adopted by the European Union in spring 2024[3] follows this approach and aims for the uptake of trustworthy and safe AI. It addresses fundamental rights such as non-discrimination, protection of privacy, data and democracy. Therefore, the AI Act comprises two types of regulatory approaches. Non-generative (‘normal’) AI applications are classified according to their risk potential. By contrast, general-purpose AI models (GPAI) such as large generative language models are not regulated according to their applications but as a technology as a whole. They have to fulfill transparency requirements including the provision of technical documentation, compliance with EU copyright law and detailed summaries of training data. With this approach, harm to individuals and specific societal groups e.g. in the form of undesired discrimination or false information should be prevented. In order to mitigate negative effects on innovation, the AI Act provides exemptions for research and for the open source development of AI models.

The AI act was recently installed and requires time to work up to its full potential. Obeying the new rules comes with fixed cost for the firms. The case of the GDPR for instance has shown that even six years after its implementation, more than 50 per cent of manufacturing as well as services firms in Germany still complain about the high effort to comply with the GDPR (Erdsiek 2024). Since it is relatively easier for the large firms to comply, there is the risk that the AI act will push out small and medium sized firms and be a barrier for the entry of start-ups. The implementation of the AI Act therefore needs to take due care to avoid this from happening.

3 Measures to Speed up AI Development and Usage in Europe

If Europe does not react fast now, it will lose connections to the leading countries in artificial intelligence. Europe and its member states need to implement the AI Act in a way that fosters innovation and allows small and medium companies, which are the pillars of the European economy, to being better able to use these new technologies. However, it is just as important that Europe strengthens its digital single market.

3.1 Better Regulation

The AI Regulation is intended to ensure legal certainty and thereby promote innovation. At the national level, governments should push for the development of practical guidelines for companies helping them to comply with the rules of the AI Act. Moreover, applying the AI Act should be consistent with the application of further regulatory frameworks at the European and the national level such as the Data Act, the Data Governance Act and the GDPR. Concentrating responsibility with one authority would reduce the burden for firms significantly.

The AI Act allows for regulatory sandboxes, which enable the testing of innovative technologies even if these are not fully compliant with the existing legal and regulatory framework. This testing is very important since it not only enables innovation and learning about how innovative products can be improved, but it also allows learning how regulation should be improved. E.g. in Germany, the government has been working on a legal framework for regulatory sandboxes[4] for several years now. This framework should be passed as quickly as possible and the government should appoint the responsible authorities and provide them with adequate resources.

Open Source might play an important role for developing large language models but also for domain-specific models and their applications. Given the dominant role played by US firms today with their proprietary models and applications, open source might be one of the few channels for European firms to compete. Therefore, state governments in Europe should push for a generous interpretation of the exceptions for open source defined in the AI Act.

Due to the dynamic technological development of AI, the possibility to flexibly adapt the regulatory framework over time is indispensable. For a proper evaluation of the AI Act, as it is planned to be conducted, it should be clearly identified right from the beginning of the implementation phase which data will be needed and how this data can be collected, for example to track the development of European providers’ market share for AI solutions.

3.2 Towards a More Dynamic Digital Single Market

The European single market is very attractive for large digital U.S. companies. Therefore, the European Union can persuade these companies to play by European rules. This provides a great leverage, and instruments like the DMA have the potential to make the European digital market more competitive and dynamic. However, focusing solely on regulation would be too short-sighted. The European Commission, and the national governments in particular, should support the development and diffusion of AI applications by providing the necessary infrastructure.

For supporting the development and application of AI, availability and access to data is crucial, in particular for small and medium-sized companies. Europe has still a competitive advantage in fields like industry 4.0. But also specific areas like health and public administration, have huge potential for applying AI. Care should be taken that in the case of these specialized applications, European companies ensure that their data does not flow solely to the dominant firms. The implementation of the GDPR differs across EU countries. A more innovation-friendly practice across states could contribute to a digital single market. By providing own administrative data, the governments can support the development of AI-based solutions.

Improving the infrastructure also implies further investment in fast broadband internet and in computing capacity. Moreover, financial support for start-ups and the digitalisation of the administration are areas where many countries in Europe have been lagging behind for a long time. In order to utilise the economic potential of a dynamic technology such as AI, dynamic action is required.

References

Bresnahan, T. F., and M. Trajtenberg. 1995. “General Purpose Technologies: Engines of Growth?” Journal of Econometrics 65 (1): 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01598-t.Suche in Google Scholar

Brynjolfsson, E., D. Rock, and C. Syverson. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence and the Modern Productivity Paradox: A Clash of Expectations and Statistics.” In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda. National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report, edited by A. Agrawal, J. Gans, A. Goldfarb, A. (Hrsg). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226613475.003.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Erdsiek, D. 2024. DSGVO: Kritische Sicht der Unternehmen ändert sich im Zeitverlauf kaum; ZEW Industry Report Information Economy (German), 1st quarter 2024. https://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/brepikt/202401BrepIKT.pdf (download July 03, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Commission of Experts for Research and Innovation. 2024. Annual Report on Research, Innovation and Technological Performance of Germany, Berlin, https://www.efi.de/fileadmin/Assets/Gutachten/2024/EFI_Report_2024.pdf (download July 03, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2021. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Fostering a European Approach to Artificial Intelligence. Brussels: European Commission.Suche in Google Scholar

European Parliament. 2024. Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence and Amending Regulations. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0138-FNL-COR01_EN.pdf (download June 25, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat beim Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz. 2024. Brief an den Bundesminister zum AI Act, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/Wissenschaftlicher-Beirat/brief-wiss-beirat-ai-act.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6 (download June 25, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial: Productivity Growth in the Age of AI

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- Inflation and Fiscal Policy: Is There a Threshold Effect in the Fiscal Reaction Function?

- Whither the Walking Dead? The Consequences of Artificial Intelligence for Zombie Firms

- The Energy Transition and Its Macroeconomic Effects

- The Potential and Distributional Effects of CBAM Revenues as a New EU Own Resource

- Will Geopolitics Accelerate China’s Drive Towards De-Dollarization?

- The Political Economy of Academic Freedom

- Policy Forum: Productivity Growth in the Age of AI

- Macroeconomic Productivity Effects of Artificial Intelligence

- New Technologies: End of Work or Structural Change?

- The AI Revolution: A New Paradigm of Economic Order

- The Interplay of Humans, Technology, and Organizations in Realizing AI’s Productivity Promise

- How Can Artificial Intelligence Transform Asset Management?

- Is the EU’s AI Act Merely a Distraction from Europe’s Productivity Problem?

- AI in Europe – Is Regulation the Answer to Being a Laggard?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial: Productivity Growth in the Age of AI

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- Inflation and Fiscal Policy: Is There a Threshold Effect in the Fiscal Reaction Function?

- Whither the Walking Dead? The Consequences of Artificial Intelligence for Zombie Firms

- The Energy Transition and Its Macroeconomic Effects

- The Potential and Distributional Effects of CBAM Revenues as a New EU Own Resource

- Will Geopolitics Accelerate China’s Drive Towards De-Dollarization?

- The Political Economy of Academic Freedom

- Policy Forum: Productivity Growth in the Age of AI

- Macroeconomic Productivity Effects of Artificial Intelligence

- New Technologies: End of Work or Structural Change?

- The AI Revolution: A New Paradigm of Economic Order

- The Interplay of Humans, Technology, and Organizations in Realizing AI’s Productivity Promise

- How Can Artificial Intelligence Transform Asset Management?

- Is the EU’s AI Act Merely a Distraction from Europe’s Productivity Problem?

- AI in Europe – Is Regulation the Answer to Being a Laggard?