Abstract

This study investigates the linguistic errors and mistranslation of bottom-up public signs (BUPSs) in a tourist area in the southern region of Saudi Arabia, namely Abha. It specifically aims to identify the types of linguistic errors and inaccurate translations found in the static BUPSs. It also examines the underlying causes behind these errors and proposes remedial strategies that could minimize them. A conceptual framework was developed based on linguistic landscape and interlanguage analysis. A qualitative research design was utilized, which involved ethnographic walks at the research site and semi-structured interviews with translators and linguists. Thematic analysis was employed to achieve the research objectives. The findings showed morphological, syntactical, semantic, pragmatic, and contextual/discourse-related errors. Furthermore, transliteration and inaccurate translation were widely used. These errors were primarily traced back to several factors, including machine translation, the incompetence of sign producers, carelessness among the signs’ producers and business owners, and a lack of awareness of cultural differences. Effective and remedial strategies were proposed for stakeholders to minimize these distractors, including hiring qualified translators and professional linguists, minimizing overreliance on machine translation, activating official regulations for sign production, and reviewing the signs before circulation. Further research is recommended on ideological and linguistic choices in tourist areas. This study adds pragmatic and discourse-related errors to the list of errors displayed on public signs.

1 Introduction

With increased internationalization and mobility, bilingualism is becoming increasingly common on public signs. This significantly enhances the linguistic landscape (LL) of the public spheres worldwide. A well-designed LL plays a key role in boosting the tourism industry by promoting tourist opportunities and delivering clear messages to visitors. In line with its Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia has prioritized tourism, and the Aseer Region Development Strategy aims to transform Abha into a year-round global tourist hotspot by 2030. In support of this strategy, the current study investigates the visual distortions caused by erroneous signs, intending to reconstruct a true image of this tourist region on an international scale.

Signs are a crucial component of the LL in public spaces; they are ubiquitous and take various forms (Gorter, 2021). These signs should be error-free, visually appealing, and tailored to the target audience. They serve both locals and international tourists, reflecting a positive image of the area’s LL. Conversely, signs filled with errors can distort the LL and fail to meet visitors’ needs (Al-Athwary, 2014; Elahi et al., 2020; Gorter, 2021).

However, it has been observed that some bilingual signs in the public spaces of Abha, Saudi Arabia, are riddled with linguistic and translational errors. From an ethnographic perspective, the researchers noted several types of these errors during their visits to the area. In addition to other mistakes, this study uniquely focuses on pragmatic and discourse-related errors, which have been overlooked in previous research. Pragmatic and discourse-related errors can have serious consequences for communication and social interaction, potentially leading to misunderstandings, confusion, and frustration among the public. These issues not only disrupt the visual experience of visitors but also serve as a motivation for this study. Moreover, no effective solutions have been proposed to address these problems, making this issue worth exploring. This study focuses on the types of errors found on public signs, their causes, and potential solutions.

The present study, therefore, examines the linguistic errors and mistranslations found on static bottom-up public signs (BUPSs) in a tourist area in southern Saudi Arabia, specifically in Abha City. It also identifies the causes of these errors and proposes remedial strategies to minimize them. Accordingly, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

RQ 1: What are the types of linguistic and translational errors evident on the static BUPSs in the research area?

RQ 2: What are the causes of these linguistic and translational errors?

RQ 3: How can these linguistic and translational errors be minimized in the research area?

2 Literature Review

This section presents an overview of the field of LL and the conceptual framework that guides this research. Moreover, it reviews the previous research and highlights the existing gaps.

2.1 LL: An Overview

LL is a promising field that has recently emerged as an independent area of study. Many scholars who have made valuable contributions to LL agree that it focuses on analyzing both linguistic and non-linguistic aspects as they appear on public signs in the public spaces of any target area (Ben-Rafael et al., 2006; Cenoz & Gorter, 2006; Gorter & Cenoz, 2015; Gorter, 2006, 2021; Landry & Bourhis, 1997; Shohamy & Gorter, 2008). For example, Landry and Bourhis (1997) defined the LL as “the language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on governmental buildings that combine to form the LL of a given territory, region, or urban agglomeration” (p. 25). Similarly, Ben-Rafael et al. (2006) stated that LL includes “any sign or announcement located outside or inside a public institution or a private business in a given geographical location” (p. 14).

Landry and Bourhis (1997) categorized public signs into two types: government and private signs, which were later labeled as top-down and bottom-up signs, respectively (Ben-Rafael et al., 2006). This study focuses on private (bottom-up) signs, which include commercial signs, advertising signs, shop signs, or business signs produced by individuals and shop owners. Public signs serve both an informational and symbolic function (Landry & Bourhis, 1997). This study emphasizes the informational function, which pertains to the relevant information displayed on signs to meet public needs. Therefore, it focuses on the informational function of static BUPSs spread across the LL of Abha, analyzed from both linguistic and translational perspectives.

2.2 The Conceptual Framework of the Study

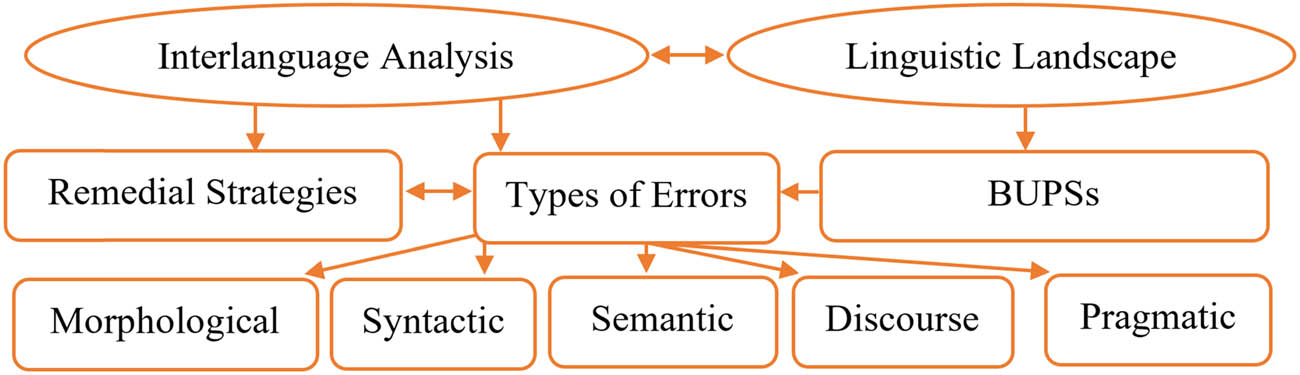

From a linguistic perspective, Guo (2012) emphasized that public signs should adhere to basic requirements such as “correct spelling, brief and concise language style, appropriate word choice, use of common words, and consideration of cultural differences” (p. 1215). From a translational perspective, Nord (2001) explained that “if the purpose of a translation is to achieve a particular function for the target addressee, anything that obstructs the achievement of this purpose is a translation error” (p. 74). Similarly, Reh (2004) classified public-sign translations in the LL into four categories: duplicating, fragmentary, overlapping, and complementary strategies. Therefore, Figure 1 represents the framework for this study, analyzing BUPSs in the target LL from both linguistic and translational perspectives.

Conceptual framework of the study. Source: Authors’ work.

Interlanguage analysis deals with types of errors in an LL tourist area. Although interlanguage approaches highlight morphological, syntactic, and semantic types of errors, this study contributes to interlanguage studies by extending types of errors into discourse and pragmatic levels. For example, semantics studies the literal meaning of words, phrases, and sentences independent of context. In contrast, pragmatics considers the contextual meaning and the appropriate selection of words. The study also employs a bottom-up approach to remedial strategies for such evident errors.

2.3 Previous Studies

Several studies have quantitatively examined translation and linguistic errors displayed on public signs in various parts of the world. Aristova (2016) explored English translations in the LL of Kazan, Russia, revealing a shift from bilingualism (Russian and Tatar) to trilingualism (Russian, Tatar, and English). The study also identified discrepancies in English translations, transliterations of Russian street names, a lack of translations for abbreviations, and deviations from proper word order. Azizul Hoque (2016) investigated errors in the English texts of signs in Bangladesh, concluding that these errors stemmed from sign owners’ carelessness, lack of knowledge, and unspecialized translators. Elahi et al. (2020) examined errors in the English translations of public signs in the Persian context, highlighting prevalent language errors, inaccurate translations, and other issues due to the translators’ unfamiliarity with the target culture. Al-Kharabsheh et al. (2008) analyzed translation errors in Jordanian shop signs, attributing them to linguistic and extra-linguistic factors. Lesmana (2021) explored humor caused by language errors in Arabic-English bilingual notices, where numerous spelling and vocabulary errors led to confusion and unintentional humor. Hojati (2013) studied linguistic errors in Farsi–English bilingual signs in Iran, finding that lexical and grammatical errors predominated.

Karolak (2020) examined the LL of Souk Naif, Dubai, uncovering that English had replaced various migrant languages on public signs. Bottom-up signs in the area included numerous spelling and translation mistakes. Al-Athwary (2014) investigated translation errors in shop signs in Sana’a, Yemen, finding lexical, spelling, and grammatical errors due to the translators’ lack of proficiency, carelessness, and sociocultural differences between English and Arabic.

Some studies have compared linguistic and translation errors between bottom-up and top-down signs. Mohebbi and Firoozkohi (2019) analyzed linguistic errors in the LL of Tehran, Iran, and found that spelling errors and mistranslations were more prevalent in bottom-up signs. Jamoussi and Roche (2017) compared linguistic discrepancies between Muscat and Dubai arterial road signs, revealing linguistic factors behind the differences.

In Saudi Arabia, a few studies have examined linguistic and translation errors in bottom-up signs. Alotaibi and Alamri (2022) explored the relative size, information, and quality of English-Arabic and Arabic-English transliterations and translations in shop signs in Riyadh and Jeddah. They identified several inconsistent and inaccurate transliterations and spelling errors. Alhaider (2018) contrasted using foreign and native languages in the LL of Souk Athulatha’a and Asir Mall in Abha. The study found that Souk Athulatha’a was dominated by Arabic unilingual signs, while Asir Mall exhibited a multilingual landscape, with widespread usage of Arabic transliterations of Western names.

Some studies have focused on the translation strategies used for public signs. For example, Algryani (2021) examined strategies employed to translate Omani non-official public signs and assessed their quality. Public signs utilized strategies such as transference, word-for-word translation, generalization, and omission, with several inaccuracies observed. Al-Athwary (2017) investigated multilingual texts on signboards in Yemen, finding that duplicating, fragmentary, overlapping, and complementary strategies were used, with duplicating and fragmentary strategies more common on top-down signs. Li (2013) confirmed that common translation errors included improper diction, word redundancy, spelling mistakes, literal translation, grammatical mistakes, and cultural misunderstandings. These errors stemmed from translators’ linguistic incompetence, insufficient knowledge of public signs, unawareness of cultural differences, and irresponsibility.

In summary, the reviewed studies indicate that a significant number of bi/multilingual public signs in various regions contain linguistic and translational errors. Lexical errors often involve inappropriate word choices in English translations. Grammatical errors were related to word order issues, such as placing adjectives after nouns in English translations. Orthographic errors included misspellings that could significantly alter meaning. Additionally, inaccurate translations, partial translations, and transliterations were commonly used. These errors were frequently attributed to translators’ unfamiliarity with the target culture, lack of sign reviews, first language (L1) influence, reliance on machine translation, linguistic incompetence, shop owners’ lack of awareness of the importance of error-free signs in attracting customers, and sociocultural differences between Arabic and English.

Previous studies have not explicitly examined pragmatic and discourse-related errors, which play a significant role in limiting the intended meaning conveyed by signs. Cultural errors can be more problematic than linguistic ones, yet they have often been overlooked in research. Furthermore, no qualitative studies have proposed strategies to minimize such errors. This study addresses this gap by qualitatively investigating errors in static BUPSs in a tourist area in southern Saudi Arabia. It also explores the underlying causes of these errors and suggests remedial strategies to reduce their occurrence.

3 Methodology

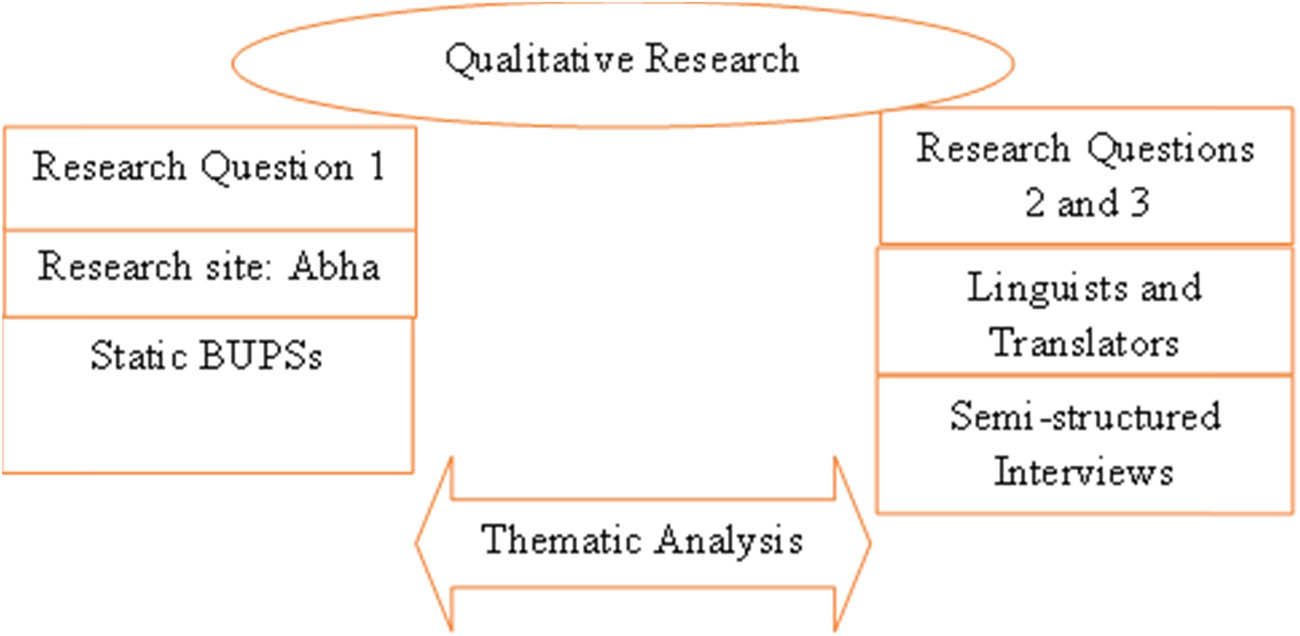

The present study employs a qualitative research design to address the research questions. While the first question identifies the types of errors made on the static bottom-up signs, the second and third questions investigate the causes of these errors and the strategies that would minimize these errors (Figure 2).

Qualitative research design for the public signs. Source: Authors’ work.

3.1 Context of Study

The research site of this study was the bilingual signs displayed in the LL of Abha in the Aseer region of Saudi Arabia. Abha was selected as a representative research site because it is a focal and tourist city of the Aseer region, densely populated with bi/multilingual signs. This city attracts a diverse population of expatriates with diverse backgrounds, who represent the English language as a lingua franca.

3.2 Procedures for Data Collection

Two instruments were used to collect data for this qualitative study: BUPSs and semi-structured interviews. In qualitative research, critical moments are those moments where a researcher finds something wrong (Byrne-Armstrong et al., 2001; Gaibisso, 2018). Accordingly, one of the researchers walked around the research area during working hours in January and February 2023 to collect data from the static BUPSs that contained evident linguistic errors and inaccurate translations. Forty-one critical moments were collected for qualitative analysis, using a smartphone camera. This number of signs best represents the available error-loaded signs at the research site. The critical moments were evident in the names of places, notices, and commercial shop signs. The selected public signs are limited to the BUPSs evident in Abha downtown, a public domain, which could best represent other sites in the Aseer region. Monolingual and error-free signs were not considered in this study.

Thirteen linguists and translators were interviewed to get deeper insights into the potential causes of these errors and explore effective strategies for minimizing them. All interviewees were experienced academics with master’s and PhD degrees in translation studies or the English language. They were employed in various education offices in the Aseer region. The interviewer scheduled in-person interviews with the interviewees at different locations in Abha city in February at different times. Before starting the interview, the interviewer explained the objectives of the study and obtained their consent to report the interview data anonymously. To ensure reliability and minimize subjectivity, the interviewer posed two guiding questions to the interviewees. These questions focused on identifying the causes of linguistic and translational errors observed in the BUP. Field notes were taken to document the outcomes of the interviews. Evident themes were coded and reported. Trustworthiness was also achieved through the authenticity of the interviewees, who were purposefully selected.

3.3 Procedures for Data Analysis

In this qualitative study, data collection and analysis were ongoing and overlapping processes. In line with the conceptual framework, the collected BUPSs were classified based on their morphological, syntactical, semantic, discourse, and pragmatic features. The unit of analysis was limited to the written text of bilingual public signs.

BUPSs were analyzed to address the first research objective, with the signs serving as examples of the identified errors. The collected data were analyzed multiple times, as some public signs contained various types of errors. These errors were reported under their relevant categories and referenced in different sections. The analyzed BUPSs were coded manually using an Excel sheet, where each sign was assigned a unique code. Each code followed the format (BUPS-X), where “BUPS” stands for Bottom-Up Public Sign and “X” represents the sign number. For example, BUPS-1 refers to sign number 1. These codes were used to organize and report the thematic findings, as well as to provide samples of each type of error in the analysis section.

Similarly, semi-structured interviews were designed to meet the second and third research objectives. To guide the in-depth investigation, two primary interview questions were used: In your opinion, what is/are the reason(s) behind errors evident in public signs? And How can such errors be avoided? Additional sub-questions were posed based on the interviewees’ responses. The interview data were manually transcribed and categorized into thematic groups using an Excel sheet. To ensure anonymity, each interview was assigned a code: (LI-X) for the Linguist Interviewee and (TI-X) for the Translator Interviewee, with “X” representing the interviewee number.

Thematic analysis is a valuable method for studying behaviors and practices in the LL and for exploring participants’ experiences or uncovering underlying meanings in texts (Maguire & Delahunt, 2017). By identifying patterns and themes, thematic analysis allows researchers to gain insight into complex topics that may not be immediately apparent (Naeem et al., 2023). Therefore, thematic analysis was used to analyze the interview data by categorizing and coding the data to identify recurring patterns and emerging themes.

4 Analysis and Findings

The qualitative analysis of the data is reported in alignment with the research objectives, focusing on identifying, categorizing, and analyzing linguistic and translational errors in the selected error-ridden BUPSs. Moreover, thematic analysis was used to analyze the interviews to identify linguists’ and translators’ opinions regarding the potential causes of these errors and effective strategies to alleviate them.

4.1 Types of Errors on the BUPSs

Data analysis revealed five types of errors: morphological, syntactical, semantic, pragmatic, and contextual/discourse errors. A significant morphological error involved the improper use of suffixes. In sample BUPS-1, the Arabic expression “مغاسلنا تُرحّب بكم” (Maghasilona torahebu bikom) on a laundry shop sign was incorrectly translated as “Laundry welcome you.” Morphologically, the singular noun “laundry” should be pluralized as “laundries” to match the plural Arabic word “مغاسلنا” (our laundries). Additionally, the subject-verb agreement is violated when “laundry” is used in the singular form. Moreover, the fragmentary translation strategy was employed, as the equivalent possessive pronoun “our” for the Arabic pronominal suffix “نا” (na) was omitted. Therefore, a more accurate translation would be “Our laundries welcome you.”

In BUPS-2, the first notice used the singular form of the Arabic word “مصعد” (masa’ad), while the second notice used the plural form “مصاعد” (masa’aid). This inconsistency in word usage should be corrected by consistently using either the singular or plural form throughout. Additionally, the first notice, “In case of Fire Please don’t use the elevator,” unnecessarily capitalized the words “Fire” and “Please.” In contrast, the second notice, “Please in case of fire (no as much as Allah) Do not use the lift,” began with “Please” and unnecessarily capitalized the auxiliary verb “Do.” These inconsistencies in capitalization should be corrected for a more professional and clearer message.

Data analysis also revealed inappropriate punctuation usage. In BUPS-3, the Arabic expression “التدخين داخل هذه المنشأة أو في حرمها يعرضك لدفع 200 ريال كغرامة مالية” (attadkheenu dakhil hatheehi almonsha’ah aw fi haramiha yoarridoka lidafa’ai 200 riyal ka gharamatin maliah) was incorrectly translated as “Smoking is not allowed on these premises fine of 200 SR will be applied.” First, the sentence “Smoking is not allowed on these premises” should have ended with a full stop or semicolon to separate it from the next part. Additionally, there was inconsistency in the use of singular and plural nouns between the Arabic and English versions. The Arabic singular phrase “هذه المنشأة” (this establishment) was incorrectly translated as the plural “these premises.” Moreover, the article “a” was missing before the countable noun “fine,” which should have been included for grammatical accuracy. A more appropriate translation would be: “Smoking is not allowed on this establishment; a fine of 200 SR will be applied.”

Syntactical errors, the second most common type, involved violations of sentence structure and word order. These errors included incorrect word order, ambiguous sentence structure, and misuse of parts of speech. Figure 3 shows that the public sign for a restaurant, “مطعم بسمي” (mata’am bismi), was incorrectly translated as “HOTEL BISMI” (BUPS-4). This translation violated proper English word order, as the adjective “Bismi” should precede the noun, not follow it. Therefore, the proposed translation should be “Bismi Restaurant.”

Sample of syntactic and semantic errors (BUPS-4). Source: Authors’ photo.

Similarly, Figure 4 illustrates another syntactical error. The Arabic expression “مُصلّى النِساء mussalla annisa’a” was translated as “Chapel Women”. In proper English word order, the word “women” should precede “chapel,” resulting in the corrected translation: “Women’s chapel.”

Sample of syntactic and contextual/discourse errors (BUPS-5). Source: Authors’ photo.

Semantic errors, the third type of error, resulted from inappropriate word choice. Figure 5 contained several semantic errors, alongside the previously mentioned morphological and syntactical errors. The Arabic excerpt “غسيل جميع أنواع المفروشات والسجاد” (ghaseel jameei anwa’a almafroshat wal sujjad) was translated as “Washing all kinds of upholstery and carpets.” The word “upholstery” refers to “the cloth used for covering a seat and/or the substance used for filling it.” Using it in this context as an equivalent for the Arabic word “مفروشات” (mafroshat), which refers to floor coverings, was semantically inappropriate.

Sample of morphological, syntactic, and semantic errors (BUPS-1). Source: Authors’ photo.

Additionally, Figure 5 demonstrates another semantic error. The excerpt “تعقيم وتعطير جميع أنواع الملابس والمفروشات بالبخار” (ta’akeem wa ta’ateer jameei anwa’a almalabis wal mafroshat bil bokhar) was translated inconsistently as “Sterilizing and perfuming all kinds of clothing and brushes with steam.” Specifically, there was no consistency in the translation of the Arabic word “مفروشات” (mafroshat). In one instance, it was inappropriately translated as “upholstery,” while in another, it was translated as “brushes,” which refers to items used for cleaning or painting – an entirely different meaning. Semantically, the word “السجاد” (alsujjad) is a hyponym of the superordinate word “المفروشات” (almafroshat). Therefore, using “upholstery” and “brushes” in this context was inappropriate. The proposed translations for the second and third services of the laundry should be “Washing all kinds of furnishings and carpets” and “Sterilizing and perfuming all kinds of clothing and furnishings with steam,” respectively.

Another example of inappropriate word choice is the translation of the Arabic phrase “ممنوع الدُّخول لغير المُطعَّمين” (mamnoa addokhol lighairi almotaemeen) as “No entry for non-restaurants” (Figure 6). This notice was confusing and misleading, particularly during the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond. The Arabic word “المُطعَّمين” (almotaemeen) specifically refers to people who have received the COVID-19 vaccination (vaccinated people), not “non-restaurants.”

Sample of semantic and pragmatic errors (BUPS-6). Source: Authors’ photo.

Figure 7 shows another semantic error. The Arabic expression “دورات مياه رجال” (dawraat miyah rijal) was translated as “Water courses for men” (BUPS-7). The literal translation of the word “دورات” as “courses” is semantically inappropriate in this context. A more accurate translation would be “WC for men” or “Men’s restroom.” The abbreviation WC is widely used with visual signs for men and women, and it is easily understood by the public.

Sample of semantic errors (BUPS-7). Source: Authors’ photo.

Another example of inappropriate word choice is found in Figure 3. The sign “مطعم بسمي” (mata’am bismi) was translated as “HOTEL BISMI” (BUPS-4). This translation is incorrect, as the English equivalent of the Arabic word “مطعم” (mata’am) is “restaurant,” not “hotel.” The substitution of words with different meanings could confuse tourists and passers-by. Therefore, the proposed translation should be “Bismi Restaurant.”

Figure 8 illustrates that the Arabic phrase “صالة العروض الاقتصادية” (saalat alorodh aliqtisadeyah) was translated as “Economic performances hall.” The term “performances” was inappropriately used in this context. The Arabic word “العروض” (alorodh) should be translated as “promotions” or “offers,” not “performances.” Therefore, a more appropriate translation would be “Economic Promotions/Offers Hall.”

Sample of semantic errors (BUPS-8). Source: Authors’ photo.

Pragmatic errors, the fourth type of error, were also observed in some BUPSs. In Figure 9, to avoid a threatening tone, the statement “Smoking is not allowed on these premises fine of 200 SR will be applied” could be restated as a request: “Thank you for not smoking here. Otherwise, a fine of 200 SR will be applied.” In such cases, with the support of the attached visual sign, the addressees are more likely to cooperate with stakeholders in the public interest.

Sample of orthographic, semantic, and pragmatic errors (BUPS-3). Source: Authors’ photo.

Similarly, Figure 10 uses all caps, bold font, and red color for “ALLOWED,” which can come across as threatening: “NO FOOD OR BEVERAGES ALLOWED BEYOND THIS POINT.” A more appropriate approach would be a request: “Thank you for not eating and drinking here.” Accompanied by the visual signs, this phrasing is likely to encourage positive reactions, as it aligns with the public interest.

Sample of semantic and pragmatic errors (BUPS-9). Source: Authors’ photo.

In addition to the semantic error in Figure 6, the translation “No entry for non-restaurants” was both unclear and somewhat aggressive. A more informative and appropriate translation would be “Covid-19 vaccination is mandatory” or “Only vaccinated people can enter.”

Context plays a crucial role in shaping meaning, as certain words are culturally bound. Choosing contextually and culturally appropriate words ensures effective communication. In addition to the syntactic error, Figure 4 contains a particularly inappropriate translation in one of the mosques in the research area. The Arabic expression “مُصلّى النِساء” (mussalla annisa’a) was incorrectly translated as “Chapel Women” (BUPS-5). Since language reflects culture, the word “chapel” was used out of context here, as it commonly refers to a small church or “a room within a larger building used for Christian worship.” It is evident that the sign producer did not consider the cultural and religious context of the sign. The correct translation in Islamic contexts would be “women’s prayer place.”

Another example of inappropriate word choice is found in a sign for Little Caesars Pizza (Figure 11). The bilingual sign, “عائلات وألعاب أطفال” (a’ailat wa ala’ab atfal), was translated as “Family and playground.” The word “playground” was inappropriate in this context, as it refers to an outdoor area, whereas the intended message was about family-friendly areas with games for children. In Saudi Arabia, there are designated places where families can eat and relax with their children. A more accurate translation would clarify this cultural distinction. Additionally, the transliteration strategy was used for “Little Caesars Pizza! Pizza!”, which works well in this context.

Sample of contextual errors (BUPS-10). Source: Authors’ photo.

Consistency in word usage is essential for effective communication. However, an erroneous BUPS was documented in one of the hotels in the research area (Figure 12). The sign lacked consistency in its word choice, using both “elevator” and “lifts,” which are American and British English terms, respectively.

Sample of orthographic, semantic, and discourse-related errors (BUPS-2). Source: Authors’ photo.

Moreover, from a translational perspective, the culturally bound Arabic expression “لا قدّر الله” (la kaddar Allah) was inappropriately translated as “not as much as Allah” (Figure 12). This expression is unnecessary in this context, and its translation does not convey the intended meaning. A more appropriate translation would be “Allah forbids.” Therefore, the correct translation of the two signs would be either “Please do not use the elevator in case of fire” or “In case of fire, please do not use the elevator.”

Another example of inaccurate translation appears in a bilingual sign hung in a hospital in the research area. The Arabic notice “ممنوع الأكل والشرب في هذا المكان” (mamnou alakl wa ashorb fi hada almakan) was translated as “No food or beverages allowed beyond this point” (BUPS-9). This translation could be misinterpreted to suggest that food and drinks are allowed within the area but prohibited beyond a certain point. A clearer translation, supported by a visual sign, would convey the intended message more effectively.

4.2 Causes of Errors on BUPSs

In line with the second research question, the semi-structured interviews were analyzed to gather expert opinions on the reasons behind these errors. The analysis reveals that identifying the causes of such errors is the first step toward minimizing them. Nearly all interviewees agreed that employees in advertising agencies, sign designers, and shop owners lacked sufficient experience and competency in English, which is essential for producing accurate translations. For example, LI-6 stated, “Most of the people who work in the advertising offices are unqualified to translate.” Similarly, LI-7 noted, “Shop owners rely on incompetent people in English, or they do not rely on translators at all. They may ask for translation from people whose English level is poor.”

In addition to linguistic incompetence, several interviewees highlighted reliance on machine translation as another factor contributing to the prevalence of translation errors on BUPSs. LI-6 explained that advertising agencies “rely on Google Translate, which may introduce linguistic errors, especially when the translators are non-native speakers of Arabic.” TI-4 further confirmed, “The biggest reason behind these errors is the use of machine translation in advertising offices.”

Two interviewees attributed the frequent linguistic and translation errors to the carelessness of shop owners and advertising offices. LI-5 suggested that “carelessness on the part of those who translate these signs” plays a role in the errors found on public signs. LI-6 added that, in some cases, “to get the translated signs ready for printing, shop owners might ask for help from unqualified people who are not part of the advertising office.”

Besides these reasons, two interviewees pointed out that the inherent differences between Arabic and English contribute to translation errors. For example, LI-1 traced the errors to “the vast differences between the Arabic and English languages, especially in sentence structure.”

Some interviewees also pointed to shortcomings in the sign production process itself. They suggested that responsible entities should review and approve signs before they are circulated. LI-9 remarked, “There are no specialists in the official authorities to review and approve the public signs before disseminating them to the public.”

Several other factors contributed to translation errors on BUPSs, including a lack of interest in and mastery of English, first-language interference, and the intentional use of errors for marketing purposes. One interviewee noted, “People’s lack of interest in the English content” exacerbates the problem. The same interviewee explained that “only people with a good command of English notice these errors.” TI-1 confirmed that, in some cases, stakeholders carelessly resort to transliteration strategies when they do not know the proper English equivalent. LI-3 observed that “The English language is used on public signs primarily to add an aesthetic touch and to fill empty spaces”. LI-6 also mentioned L1 interference as a reason for errors on public signs. Interestingly, LI-8 suggested that some errors “may be intentional for marketing reasons (to attract customers’ attention), or they may occur incidentally due to a lack of knowledge.”

4.3 Error-Minimization Remedial Strategies

Once the causes of translation errors were identified, the interviewees proposed several remedial strategies to minimize their occurrence on BUPSs. They suggested that hiring qualified translators or professional linguists is one strategy to minimize linguistic errors on the BUPSs. Eight (out of 13) interviewees strongly emphasized the importance of hiring qualified translators in government entities and advertising agencies to review and approve the translation content displayed on public signs before circulation. LI-6, for example, reported that “advertising offices should either employ qualified people in the translation aspect or seek help from the concerned entities in this regard, such as universities or institutes.” In line with this idea, LI-9 confirmed that “official authorities must not approve the bi/multilingual public signs unless they were exposed to accredited translation offices and bringing a document that proves that, especially since these signs have a direct effect on tourists who do not speak Arabic.” TI-2 reported that “the municipality is supposed to review the content of signs before approving it.” Furthermore, LI-5 stated that “bi/multilingual signs should be approved by accredited translation offices before disseminating them to the public.” Six (out of 13) interviewees mentioned that to avoid the errors spread on the public signs, specialists and employees in advertising agencies should master the English language and have a good level of English. For instance, LI-7 asserted that to avoid producing erroneous public signs, “people should rely on competent translators or at least people who are good in English and Arabic.”

In addition to hiring qualified translators or professional linguists, some interviewees suggested that implementing official regulations could help minimize translation errors on BUPSs. They emphasized that to avoid erroneous public signs, official regulations should be activated. For instance, LI-1 stated that “activating regulations can play a role in leading advertising agencies and shop owners to consult specialists when producing bilingual signs.”

While some interviewees acknowledged the potential benefits of machine translation when used by qualified translators, others cautioned against its misuse by unspecialized producers of public signs. They suggested using specialized translation tools such as dictionaries as a remedial strategy when translating public signs. Five interviewees referred to machine translation as a reason for erroneous signs. Unexpectedly, only one interviewee (TI-4) mentioned avoiding literal translation and machine translation as strategies for minimizing errors on public signs. Similarly, interviewee LI-3 preferred the “Arabic monolingual signs” to bi/multilingual signs.

In summary, the errors identified on BUPSs were primarily morphological, syntactical, semantic, pragmatic, and discourse-related. Furthermore, most of the utterances on the BUPSs under analysis were translated from Arabic into English since Arabic is the official language and English is a foreign language that is widely used in the target context. Additionally, transliteration strategy and mistranslation were found on some of the collected BUPSs. These errors were attributed to the lack of competency and experience among advertising agency employees, sign designers, and shop owners; over-reliance on machine translation; and shop owners’ and advertising offices’ low responsibility and carelessness about the importance of error-free signs for the success of their businesses and the development of the LL as a whole. The processes of producing these signs are another cause of linguistic errors. Hiring qualified translators or professional linguists in advertising agencies and government sectors, activating official regulations for sign production, and avoiding literal and machine translation were among the remedial strategies that could be applied to minimize such errors.

5 Discussion

In line with the research questions, this section synthesizes the findings and compares them with previous research, focusing on the types of errors, their causes, and potential strategies for mitigation.

Five types of errors were identified on the BUPSs at the research site: morphological, syntactical, semantic, pragmatic, and discourse-related errors. Within morphological errors, there were orthographic errors, including spelling mistakes, and affix errors, primarily involving suffixes. Syntactic errors included incorrect word order, such as placing adjectives after nouns, structural ambiguity, and the substitution of parts of speech, particularly replacing adjectives with nouns. Semantically, many BUPSs exhibited inappropriate word choices. At the discourse level, several signs distorted the intended meaning for the audience. Pragmatically, some BUPSs used contextually and culturally inappropriate words. In general, these findings align with previous research on linguistic errors in various contexts (Al-Athwary, 2014; Aristova, 2016; Elahi et al., 2020; Hojati, 2013; Karolak, 2020; Lesmana, 2021; Li, 2013; Mohebbi & Firoozkohi, 2019).

The results revealed four key causes of linguistic errors on BUPSs: (a) lack of competency and experience among advertising agencies, sign designers, and shop owners; (b) over-reliance on machine translation; (c) carelessness of shop owners and advertising offices; and (d) shortcomings in the sign production process. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Al-Athwary, 2014; Algryani, 2021; Azizul Hoque, 2016; Karolak, 2020; Lesmana, 2021; Li, 2013; Mohebbi & Firoozkohi, 2019). Interestingly, the results also highlighted first-language interference as a contributor to translational errors, confirming findings from previous studies (Al-Athwary, 2014; Algryani, 2021; Mohebbi & Firoozkohi, 2019). Additionally, failure to account for cultural differences was another major cause of linguistic errors and mistranslations (Elahi et al., 2020; Li, 2013).

To minimize these errors, several practical remedial strategies can be applied. These include hiring qualified translators and professional linguists in advertising agencies and avoiding literal and machine translations. Moreover, the findings emphasize the role of official entities in enforcing regulations for sign production before their public dissemination. This is consistent with Gorter’s (2021) assertion that “authorities usually take responsibility for decisions on language policies, and they often attempt to regulate which languages can be used in the public space. Legislation of signage aims to control the language (or languages) seen in public” (p. 20). Similarly, Alfaifi (2015) pointed out that the Saudi Ministry of Commerce is responsible for overseeing and approving which languages can be used to name stores and companies.

The private sector must also play a proactive role in reviewing public signs before their circulation, as this will enhance the LL of tourist areas. Businesses must comply with the Ministry of Commerce’s regulations on BUPS production, which safeguard tourist areas from linguistic errors. With advances in technology, the approval process for sign production is now electronic, ensuring that no sign is approved unless it meets the stipulated conditions. Implementing these measures could significantly reduce linguistic errors and mistranslations in public signs.

This qualitative study contributes meaningfully to LL research by analyzing linguistic errors and inaccurate translations found on static BUPSs. It sheds light on the pragmatic and discourse-related errors discovered and underscores the importance of delivering contextually and culturally appropriate messages to meet the objectives of sign designers and stakeholders, thus improving the LL of the research area. Additionally, the study addresses the phenomenon by identifying error types, investigating their causes, and proposing remedial strategies to mitigate these errors. Specifically, activating official regulations and implementing early review and approval processes for signs were identified as effective strategies, which were not explored in previous research.

6 Conclusions and Implications

This qualitative study analyzed the errors displayed on static BUPSs from both linguistic and translational perspectives. It also identified the primary causes of these errors and proposed remedial strategies to reduce their occurrence. The study involved collecting erroneous signs from Abha city in the southern region of Saudi Arabia and conducting semi-structured interviews with thirteen linguists and translators to achieve its objectives. The analysis revealed morphological, syntactical, semantic, discourse, and pragmatic errors. These linguistic and translational issues were attributed to several factors, including using machine translation, the incompetence of sign producers, carelessness among sign producers and business owners, and a lack of awareness of cultural differences. Minimizing these errors is a joint responsibility among all stakeholders. Qualified translators and professional linguists in advertising agencies and government offices should be employed, while literal and machine translation should be avoided. Additionally, official regulations for sign production should be enforced. In other words, BUPSs in tourist areas must be reviewed and approved by the relevant authorities before being circulated.

The researchers hope that these initiatives will reduce the number of errors on signs and raise awareness among the public and relevant entities about the importance of error-free signs for the development of the LL in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. This qualitative study was limited to an analysis of static BUPSs in Abha from a linguistic and translational perspective, so the findings may not be generalizable to other areas. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the LL in the target area, a larger-scale study focusing on pragmatics can be conducted in tourist regions. Follow-up studies are also recommended to assess whether the LL in the target area has improved over time.

To achieve error-free signs and improve the LL in the research area, the current study offers the following implications: First, machine translation and other artificial intelligence tools should be used as complementary resources by experts such as linguists and translators, who can account for different contexts and cultural differences. Second, official authorities, such as labor offices and municipalities, should encourage advertising agencies and offices to employ or consult translation experts to review and approve bilingual signs before they are disseminated to the public, particularly in tourist areas.

-

Funding information: The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program.

-

Author contributions: Bakr Al-Sofi–theoretical framework, data collection, data analysis, and editing; Abduljalil Hazaea–conceptualization, literature review, methodology, discussion, and editing; Abdullah Alfaifi–original draft preparation, data collection, data analysis, writing, and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Al-Athwary, A. A. H. (2014). Translating shop signs into English in Sana’a’s streets: A linguistic analysis. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(12), 140–156. https://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_12_October_2014/17.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Athwary, A. A. H. (2017). English and Arabic inscriptions in the linguistic landscape of Yemen: A multilingual writing approach. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 6(4), 149–162. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.4p.149.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Kharabsheh, A., Al-Azzam, B., & Obeidat, M. M. (2008). Lost in translation: Shop signs in Jordan. Meta, 53(3), 717–727. doi: 10.7202/019255ar.Suche in Google Scholar

Alfaifi, A. (2015). Linguistic landscape: The use of English in Khamis Mushait Saudi Arabia. (M.A. thesis). State University of New York.Suche in Google Scholar

Algryani, A. (2021). On the translation of linguistic landscape: Strategies and quality assessment. Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 24(2), 5–21. doi: 10.5782/2223-2621.2021.24.2.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Alhaider, S. (2018). Linguistic landscape: A contrastive study between Souk Althulatha’a and Asir Mall in Abha city, Saudi Arabia. (Ph.D. dissertation). University of Florida.Suche in Google Scholar

Alotaibi, W. J., & Alamri, O. (2022). Linguistic landscape of bilingual shop signs in Saudi Arabia. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 13(1), 426–449. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol13no1.28.Suche in Google Scholar

Aristova, N. (2016). English translations in the urban linguistic landscape as a marker of an emerging global city: The case of Kazan, Russia. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 231, 216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.09.094.Suche in Google Scholar

Azizul Hoque, M. (2016). Patterns of errors and mistakes in the English writings of commercial signs in Bangladesh: A case study. Journal of Global Business and Social Entrepreneurship (GBSE), 2(5), 25–34.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Rafael, E., Shohamy, E., Hasan Amara, M., & Trumper-Hecht, N. (2006). Linguistic landscape as symbolic construction of the public space: The case of Israel. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3(1), 7–30. doi: 10.1080/14790710608668383.Suche in Google Scholar

Byrne-Armstrong, H., Higgs, J., & Horsfall, D. (2001). Critical moments in qualitative research. Butterworth-Heinemann Medical.Suche in Google Scholar

Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2006). Linguistic landscape and minority languages, International Journal of Multilingualism, 3(1), 67–80. doi: 10.1080/14790710608668386.Suche in Google Scholar

Elahi, N., Esfahani, A., & Yazdanmehr, A. (2020). Error analysis of English translation of Persian public signs in the light of Liaoʼs model (2010). International Journal of English Language and Translation Studies, 8(3), 45–55.Suche in Google Scholar

Gaibisso, L. A. C. (2018). A critical systemic functional linguistics approach to science education: Emergent bilingual learners as agentive meaning-makers. (PhD dissertation). University of Georgia.Suche in Google Scholar

Gorter, D. (2006). Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism. International Journal of Multilingualism, 3(1), 1–6. doi: 10.1080/14790710608668382.Suche in Google Scholar

Gorter, D. (2021). Multilingual inequality in public spaces: Towards an inclusive model of linguistic landscapes. In R. Blackwood & D. A. Dunlevy (Eds.), Multilingualism in public spaces empowering and transforming communities (pp. 13–31). Bloomsbury Academic. doi: 10.5040/9781350186620.ch-001.Suche in Google Scholar

Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2015). The linguistic landscapes inside multilingual schools. In B. Spolsky, B. Tannenbaum, & O. Inbar (Eds.), Challenges for language education and policy: Making space for people (pp. 151–169). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Guo, M. (2012). Analysis on the English-translation errors of public signs. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(6), 1214–1219. doi: 10.4304/tpls.2.6.1214-1219.Suche in Google Scholar

Hojati, A. (2013). A study of errors in bilingual road, street and shop signs in Iran. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(1), 607–611. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n1p607.Suche in Google Scholar

Jamoussi, R., & Roche, T. (2017). Road sign romanization in Oman: The linguistic landscape close-up. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 40(1), 40–70. doi: 10.1075/aral.40.1.04jam.Suche in Google Scholar

Karolak, M. (2020). Linguistic landscape in a city of migrants: A study of Souk Naif area in Dubai. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19(4), 605–629. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2020.1781132.Suche in Google Scholar

Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality: An empirical study. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49. doi: 10.1177/0261927X970161002.Suche in Google Scholar

Lesmana, M. (2021). Humor and language errors in Arabic-English informative discourse. International Journal of Society, Culture and Language, 9(1), 58–68.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, G. (2013). A study of pragmatic equivalence in C-E translation of public signs: A case study of Xi’an, China. Canadian Social Science, 9(1), 20–27. doi: 10.3968/j.css.1923669720130901.1084.Suche in Google Scholar

Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 7(3), 3351–3364. http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335.Suche in Google Scholar

Mohebbi, A., & Firoozkohi A. H. (2019). A typological investigation of errors in the use of English in the bilingual and multilingual linguistic landscape of Tehran. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(1), 24–40. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2019.1582657.Suche in Google Scholar

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231205789. doi: 10.1177/16094069231205789.Suche in Google Scholar

Nord, C. (2001). Translating as a purposeful activity. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Reh, M. (2004). Multilingual writing: A reader-oriented typology – with examples from Lira Municipality (Uganda). International Journal of the Psychology of Language, 170, 1–41. doi: 10.1515/ijsl.2004.2004.170.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Shohamy, E., & Gorter, D. (Eds.). (2008). Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203930960.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Intervening “City Horses”: Soft Performative Gestures of Protest in Public Space

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

- Bodies and Things: Technology and Violence as a Vehicle for Posthumanist Ontologies in Julia Ducournau’s Titane

- Narrating the Ruins: Eco-Orientalism, Environmental Violence, and Postcolonial Ecologies in Arab Anglophone Fiction